Abstract

Meat-processing wastewater (MPWW) is rich in nutrients and organic matter. This study assessed its potential as feedstock for microalgal biomass production while enabling wastewater treatment. In batch assays, the microalgae-based consortium grew in raw MPWW, and its synergy with the native wastewater microbial community enhanced the chemical oxygen demand (COD) removal rate. If suspended solids were pre-removed from wastewater, COD removing rates improved from 828.5 ± 60.5 to 1097.5 ± 22.2 mg L−1 d−1. In a raceway system operated in fed-batch mode with sieved and sedimented MPWW, COD removal was consistently achieved across feeding cycles, despite the variability in wastewater composition, reaching rates of up to 806.3 ± 0.0 mg L−1 d−1. Total nitrogen also decreased in most cycles. Microalgal biomass, estimated from total photosynthetic pigment’s concentration, increased from 0.4 to 17.9 µg mL−1. The microalgae-based consortium became more diverse over time, harboring at the end, additional eukaryotic taxa such as protozoan grazers and fungi (e.g., Heterolobosea class and Trichosporonaceae and Dipodascaceae families), although their roles in removal processes remain unknown. This study highlights the potential use of real MPWW as feedstock for microalgal-based biomass production with concomitant carbon/nutrient load reduction, aligning its implementation with circular economy percepts.

1. Introduction

The meat industry is known to be the one, among all the food industries, with the highest environmental footprint. This is mainly due to greenhouse gas emissions, production of high loads of solid wastes and wastewater, and the use of scarce resources, such as land, water, and energy [1]. Meat and its derivative products are present in the daily meals of much of the world’s population, and both their production and consumption tend to rise [2]. Therefore, it is imperative to find ways to manage and control the environmental consequences promoted by this increase, helping the sector to achieve both environmental sustainability and economic viability.

Meat processing wastewater (MPWW) is typically characterized by high contents of suspended solids and organic compounds, mainly due to the presence of proteins, blood, stomach contents, and fat, among other materials. When compared to domestic wastewater, MPWW often exhibits higher chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSSs), and phosphorous and nitrogen contents, which constitute a threat to its treatment [3]. The discharge of untreated MPWW contributes to the deterioration of surface water quality, severely impacting aquatic ecosystems. Therefore, proper treatment of MPWW is essential, and if wastewater remediation can be coupled with a valorization strategy, it may enhance the sustainability of the meat-processing sector. In fact, valorization of food processing wastewater into value-added products has gained increasing scientific interest [4], but valorization processes applied to MPWW remain scarce.

The use of microalgae for the treatment of wastewater of different origins, ranging from municipal, agricultural (dairy, fish processing) to industrial (textile, tannery), has been reported [5]. Microalgae-based processes are a greener and more sustainable alternative for wastewater treatment, as they not only remove pollutants efficiently but also convert them into valuable biomass, thereby creating opportunities for resource recovery and added economic return. In fact, the microalgae biomass produced during the treatment can then be harvested and valorized into high value-added products, such as biofertilizers, biogas, animals feed, biofuels, among others [6]. The treatment of wastewater from various sectors of meat production and processing using microalgae biomass has been widely studied, as this wastewater contains the essential nutrients required for microalgae growth (carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorous, mainly) [7,8,9]. In addition, the use of MPWW as feedstock for microalgae biomass production avoids the need for large quantities of freshwater and external nutrient additions, which often make large-scale microalgae biomass production unsustainable [6]. Several studies, at laboratory-scale, have previously reported strategies for the utilization and valorization of MPWW as feedstock for microalgae cultivation. Latiffi et al. (2016) used Botryococcus sp. microalgae to treat MPWW, achieving removal efficiencies of over 94% for COD, total nitrogen (TN), and phosphate (PO43−) [8]. The ability of Scenedesmus sp. for phycoremediation of MPWW allowed for considerable biomass production [7]. In addition, the production of biodiesel, biogas, biohydrogen, and bioethanol from microalgae biomass has been extensively studied, suggesting an affordable and efficient production alternative to the currently used methodologies [9,10,11,12,13,14]. Nevertheless, most of these studies use MPWW that has undergone pre-treatment steps, such as sterilization or solid–liquid separation. The implementation of certain pre-treatment steps may not be feasible at a larger scale and may imply additional operational costs, reducing the economic viability of microalgae production systems. Additionally, such pre-treatment steps may disrupt or eliminate the wastewater microbial community, which can otherwise be beneficial for microalgae activity through the establishment of symbiotic relationships [15], as mixed microbial consortia are known to provide robustness and functional resilience when treating complex streams [16].

In this context, the aim of this work is to evaluate the feasibility of producing microalgae biomass, using real MPWW as feedstock whilst treating the effluent, which is an approach that integrates biomass production with sustainable wastewater remediation. Unlike many studies that rely on synthetic media, this research uses real MPWW, maintaining its native microbial community and its intrinsic variability. Initially, batch experiments were conducted, as a prior step, to evaluate the influence of the native microbial community and the suspended solids in real MPWW on the growth of microalgae and on its carbon and nutrient removal capacity. Subsequently, the long-term performance of microalgae was assessed in a laboratory-scale raceway pond operated under fed-batch mode, mimicking realistic wastewater treatment scenario. This combined strategy allows not only the evaluation of biomass productivity and treatment efficiency, but also provides new insights into system resilience under the day-to-day variations in real MPWW composition. Overall, this work addresses practical challenges often overlooked in laboratory studies and represents an essential step toward scaling up and implementation of such systems in real-world applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microalgae Consortium Stock Culture

The microalgae mixed consortium used as inoculum is derived from a consortium assembled with cultivable microalgae species originally isolated from a filtering system in a freshwater aquaculture facility [17]. The consortium was maintained over time in exponential growth in liquid growth medium (Supplementary Materials) by replacing, periodically, half of the culture by fresh medium, in sterile conditions. The flasks used for cultivation were covered on the top with gauze and cotton, allowing for gas exchange, and were maintained under constant illumination (16.2 W; 6500 K; 1700 lm; 220–240 V) and agitation (110 rpm), at a temperature of ca. 21 °C. Before using the microalgae consortium in the present work, the consortium was plated in BG-11 agar plates and the different microalgae colonies grown were isolated using the streak-plate procedure based on their size, morphology, and pigmentation. Cells were collected from agar plates for DNA extraction using Chelex-100 (6% w/v) extraction buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, MA, USA, sourced by Portugal) [18]. To identify each isolate, an amplification of the 18S ribosomal DNA region was performed using two universal eukaryotic primers, namely EUF: 5′-GTCAGAGGTGAAATTCTTGGATTTA-3′ as the forward primer and EUR: 5′-AGGGCACGACGTAATCAACG-3′ as the reverse primer, according to Couto et al. (2022) [17]. Purification of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products was performed using the GRS PCR and Gel Band Purification Kit (GRiSP, Porto, Portugal) and amplicons were sequenced at GATC Biotech (Konstanz, Germany). The obtained genomic sequences were manually trimmed using the BioEdit software (version 7.0.5) to remove the indistinct regions of the sequences in their distal (5’ and 3’) ends. Online identity searches were performed against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) database using the nucleotide NCBI Web Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, version 2.16.0) interface to determine the phylogenetic affiliation of each isolate. The phylogenetic analysis of each isolate was performed with the MEGA7 software (version 7.0). For that, the highest-scoring BLAST matches for 18S rDNA sequences corresponding to each isolated microalgae strain were retrieved from NCBI database. The dataset was aligned using ClustalW under default parameters, and poorly aligned regions at both ends were trimmed, resulting in a final alignment matrix of 667 positions per sequence. The most suitable evolutionary model was selected based on the Bayesian information criterion. A phylogenetic tree was then constructed using the neighbor-joining approach [19] and evolutionary distances were calculated according to Jukes–Cantor method [20]. The robustness of the tree was estimated by bootstrap analysis based on 1000 replications [21].

2.2. Wastewater Sampling and Characterization

The raw MPWW was provided by a meat processing factory in northern Portugal (facility name withheld for confidentiality) and consisted of a mixture of liquid streams from the product cooling process (50%) and from the washing of cooking drums (50%). MPWW was collected during nine sampling campaigns. For the initial characterization of the MPWW, samples were collected on seven different days over two consecutive weeks (sampling campaigns 1 to 7, Table 1). For the experimental assays, MPWW samples were obtained during two subsequent campaigns (sampling campaigns 8 and 9). In each campaign, approximately 5 L of MPWW were collected and samples were transported to the laboratory and processed within 8 h after collection. Wastewater’s physico-chemical parameters such as pH, conductivity, salinity, chloride ion (Cl−), phosphate–phosphorus (PO43−-P), total-nitrogen (TN), ammonium (NH4+-N), nitrate (NO3−-N), nitrite (NO2−-N), COD, and TSS were analyzed (Section 2.4.1). Microbiological quality, in terms of cultivable organisms, was assessed through total viable bacterial counts, without differentiating or classifying the colonies obtained (Section 2.4.2).

Table 1.

Physico-chemical characterization of the raw MPWW collected over time in the industrial setting. Sampling campaigns 1–7 were performed in different days over a period of two weeks. Sampling campaigns 8 and 9 were performed later and used in the batch experiments.

2.3. Phycoremediation Experiments

For inoculum preparation, microalgae consortia liquid culture was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min, washed with saline solution (NaCl 0.85% w/v), and centrifuged again at 3000 rpm for 10 min [22]. Pellets were resuspended in MPWW to obtain an initial cell concentration of 1 × 106 cells mL−1.

2.3.1. Batch Assays with Microalgae

To assess the capacity of the microalgae-based consortium to grow and simultaneously remove carbon and nutrients in the presence of the wastewater native microbial community, a batch experiment was designed with the following test conditions, in duplicates (n = 2): raw MPWW in the absence of the microalgae consortium and raw MPWW in the presence of the microalgae consortium. The total fraction of the MPWW used in this experiment (sampling campaign 8) was characterized as described in Section 2.2.

To investigate the influence of suspended solids in MPWW on microalgae growth and nutrient removal ability, a second batch assay was performed with the following test conditions, in triplicates (n = 3): raw MPWW supplemented with the microalgae consortium and sieved; sedimented MPWW supplemented with microalgae consortium. For the preparation of sieved and sedimented MPWW, part of the raw MPWW was passed three consecutive times through a 1 mm2 mesh sieve to remove large particles. Subsequently, the sieved wastewater was left to settle by gravity for 4 h under static conditions, allowing heavier suspended solids to settle. The clarified wastewater was then collected and further used. This approach is consistent with wastewater pre-treatment practices commonly reported for high-solids wastewaters [23]. The total fraction of the MPWW used in this experiment (sampling campaign 9) was characterized as described in Section 2.2.

To assemble both batch experiments, the microalgae cell pellets were resuspended in 250 mL of wastewater (which varied according to the test condition). All flasks were incubated at 21 °C, under continuous agitation at 110 rpm and light supply for 24 h, in a specialized microalgae chamber (16.2 W; 6500 K; 1700 lm; 220–240 V). Samples were taken periodically for evaluation of microalgae photosynthetic pigment content and nutrient consumption.

2.3.2. Raceway Operation Under Fed-Batch Mode

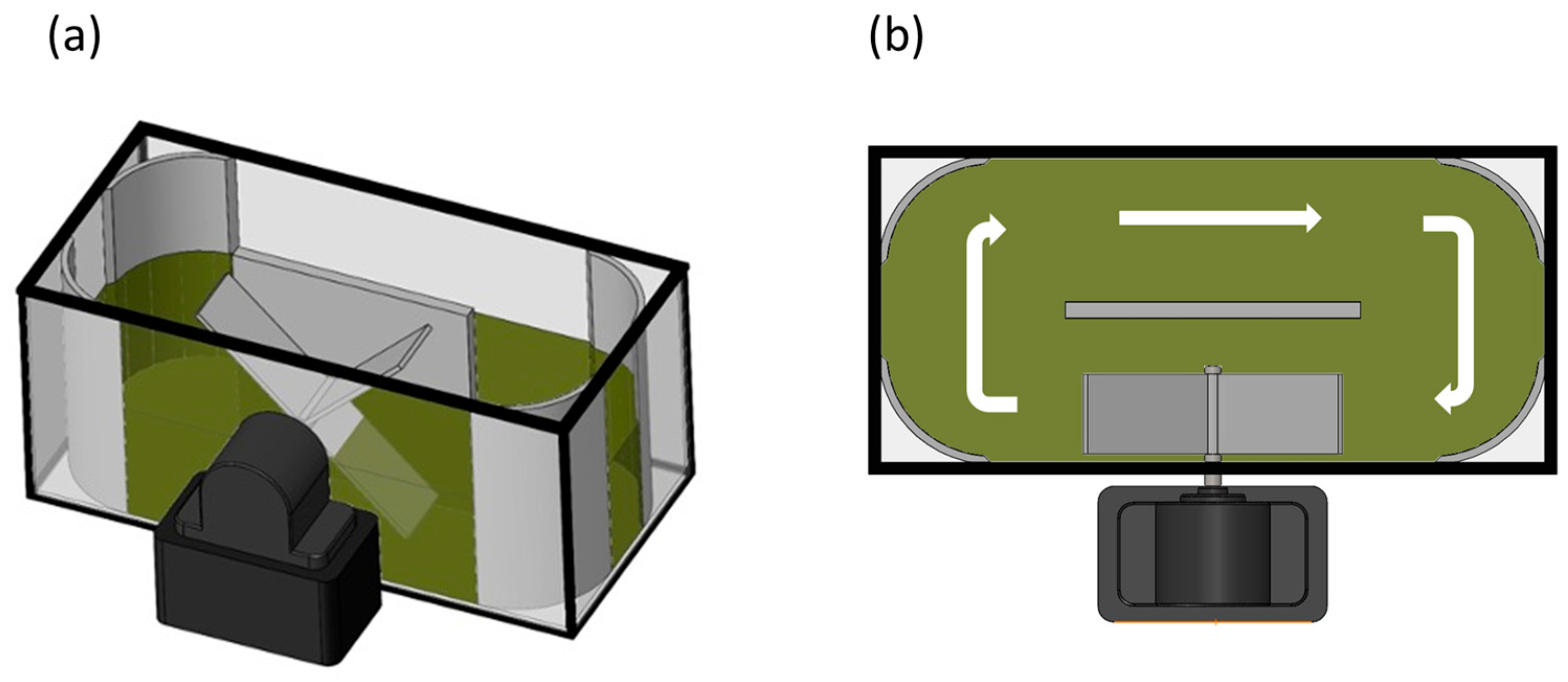

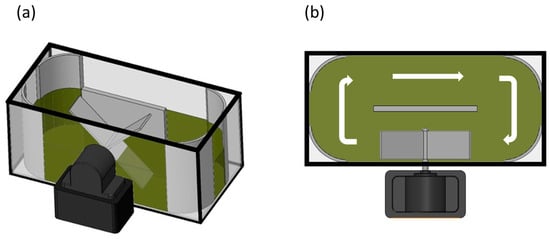

The capability of microalgae to proliferate in real MPWW, while treating it, was assessed in a lab-prototype raceway (Figure 1). The raceway consisted of a closed-loop oval channel prototype made of glass with an internal divider to ensure unidirectional flow. The raceway has a surface area of 0.849 m2, a liquid depth of 0.019 m, and a working volume of 5 L. Mixing was provided by a five-blade paddle wheel, operating at 35 rpm. The raceway was operated indoors under continuous, controlled artificial lighting. Illumination was provided by LED strips mounted on a support structure positioned at ca. 23 cm above the culture surface, delivering a uniform light intensity of 400 lux. The system was operated at room temperature. The raceway was inoculated with the microalgae-based consortium at an initial concentration of 106 cells mL−1. Over a two-month period, the raceway was operated under fed-batch mode. The wastewater was added once at the beginning of each fed-batch cycle. At the end of each cycle, fresh MPWW (about 40% of the working volume) was added to bring the raceway back to its working volume. A total of seven fed-batch cycles were carried out, with MPWW additions on days 0, 8, 15, 34, 41, 48, and 55, hereinafter referred to as cycles I to VII. Hydraulic retention time was 20 days for cycle I, 17.5 days for cycle II, 47.5 days for cycle III, and 17.5 for cycles IV to VII. MPWW samples were collected on different days at the industrial facility. The wastewater was grounded and frozen at −20 °C within 24 h of collection. Short-term storage at −20 °C (up to 52 days) is reported as a suitable procedure that does not substantially alter the physico-chemical or microbiological properties of wastewater [24]. After thawed, the MPWW was sieved and sedimented to restore homogeneity. Before addition to the raceway, each batch of wastewater was characterized (Table 2). At the beginning and end of each fed-batch cycle, sampling was performed in duplicates (n = 2) to evaluate nutrients and biomass content in the raceway.

Figure 1.

Scheme illustrating the prototype raceway system used in the experiment: (a) axonometric view, and (b) top view of the raceway system. White arrows represent the flow direction.

Table 2.

The composition of MPWW in each raceway fed-batch cycle. Prior to use, the wastewater was grinded, sieved, and sedimented.

2.4. Analytical and Microbiological Procedures

2.4.1. Physico-Chemical Characterization of the Wastewater

The determination of the TN, PO43−-P, NH4+-N, NO3−-N, NO2−-N contents was performed using Spectroquant® photometric test kits (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For thes determinations, the collected samples prior to analysis were centrifuged (8000 rpm for 10 min) and then filtered using 0.45 µm pore size nylon syringe membrane filters (Chromafil® PET filters, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) to remove biomass. The determination of the pH and conductivity/salinity were performed with a CRISON conductivity electrode (CRISON, Barcelona, Spain) and a WTW TetraCon 325 electrode (Xylem Analytics, Weilheim, Germany), respectively. TSS and COD were determined according to standard methods [25].

COD and TN removal rates were calculated according to the following equation for each cycle and normalized per day:

COD, TN, and TSS organic loading rates and biomass productivity were calculated according to the following equations for each cycle and normalized per day:

2.4.2. Microbiological Characterization of the Wastewater

To determine the total numbers of cultivable native bacteria in MPWW, the standard plate count method was used. For that, serial dilutions of the MPWW were made in saline solution (NaCl 0.85% w/v, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA), up to 10−8, in triplicate. A volume of 100 μL of each dilution was spread onto nutrient agar plates. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 25 °C after which colonies forming units (CFUs) were counted.

2.4.3. Analysis of Microalgal Biomass Through Photosynthetic Pigment Quantification

Due to the nature of the wastewater, characterized by the presence of suspended fat and meat particles, the most conventional methods to estimate biomass, including dry weight, cell counts, and optical density, were not reliable. Assuming that the photosynthetic pigments (chlorophylls a and b, and carotenoids) were originated exclusively from microalgae, as no other organisms or materials present in the wastewater would contribute to these pigments, microalgae biomass content was estimated through photosynthetic pigment quantification. Photosynthetic pigments namely chlorophyll a, b and total carotenoids were extracted from the microalgal biomass using pure methanol as organic solvent. The procedure was adapted from Henriques et al. (2007) [26] and Miazek and Ledakowicz (2013) [27]. About 0.5 mL of the microalgae culture were collected and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, at 4 °C. Supernatant was discharged and the pellet was washed twice with deionized water and centrifuged again. Pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of methanol with strong vortex-mixing for 15 s and left overnight, at room temperature and protected from light. The solution was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min, at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, and its absorbance was determined using a spectrophotometer, at the following wavelengths: 665 nm, 652 nm, and 470 nm. The concentration of chlorophyll a, b and total carotenoids were estimated as described in Sumanta et al. (2014) [28].

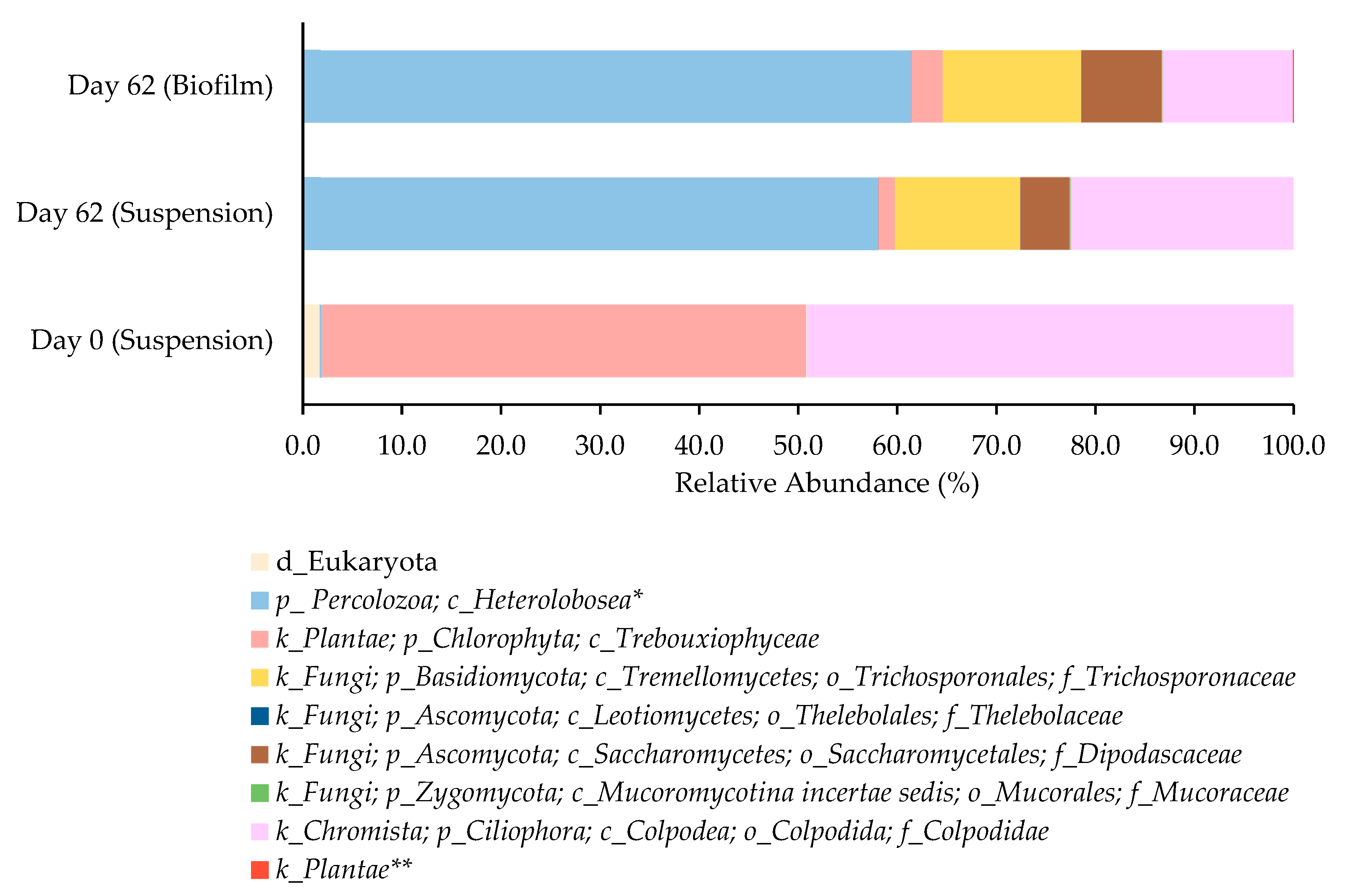

2.4.4. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) of the Raceway Eukaryotic Biomass Community

Biomass samples from the stock microalgae culture and from the raceway suspension as well as from the biofilm developed inside the raceway at day 62 were collected for community analysis. Community profiling was performed using 18S rRNA sequencing to specifically target eukaryotic taxa. As the study aimed to assess whether MPWW could be valorised through microalgal biomass production, this approach enabled us to track shifts in the microalgal and other eukaryotes organisms within the system over the process. Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Power Soil kit (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands). The 18S rRNA gene from the three samples was sequenced with the Illumina MiSeq platform (STAB Vida, Caparica, Portugal) using the following group of primers, V8F (5’-ATAACAGGTCTGTGATGCCCT-3′) and 1510R (5′-CCTTCYGCAGGTTCACCTAC 3′) [29], and applying 2 × 300 bp paired-end read libraries. The raw paired-end reads were demultiplexed, assembled, and analyzed using QIIME2 (v2022.2) to identify OTUs (operational taxonomic units). DADA2 plugin was used for denoising, chimera removal, and trimming [30]. Taxonomy was assigned using a classifier trained by the scikit-learn classifier with the SILVA (release 138 QIIME) database (clustering threshold of 99% similarity). For classification purposes, only OTUs containing at least 10 sequence reads were considered as significant. The biomass samples’ raw sequenced data was deposited in the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) database, with BioProject accession number PRJNA1136449 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA1136449, publicly available since 17 July 2024). The Shannon diversity index was calculated for each sample using the vegan package (version 2.7.2) in R (version 4.5.2) within RStudio (version 2025.09.2 + 418).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wastewater Characterization

Over two weeks, wastewater samples were collected on different days of the week from the meat processing facility to assess their physical and chemical properties which are summarized in Table 1.

The wastewater showed considerable variability in its physico-chemical composition over time, with no consistent trend for each day of the week. The MPWW variability was also evident by the differences in its reddish color intensity, probably due to the presence of blood and suspended pieces of meat or fat (Figure S1). The variations in the aspect and chemical composition of the collected wastewater may have occurred mainly due to different daily production patterns. The composition of the MPWW showed higher variations in the PO43−-P, NH4+-N, TN, and COD contents over time. The range of values obtained for total COD (518–17,807 mg O2 L−1) and TSS (0.6–11.3 g L−1) are higher than the ones described in the literature for the same type of wastewater: 1684–4000 mg O2 L−1 for COD and 0.5–2.0 g L−1 for TSS [8,31,32,33]. On the other hand, the concentrations of PO43− -P (8.8–355 mg L−1) are like the ones described in previous studies, whereas the TN (22–1787 mg L−1) are lower than the ones reported in the literature [8,31,32,33]. The high concentrations of chlorine ions (up to 1540 mg L−1) in the MPWW can be due to the sodium chloride added during the process to meat products for conservation and flavor enhancement purposes [34]. The PO43−-P content of the MPWW can be considered high when compared to other agro-food wastewaters, like the ones from the dairy industry. Phosphate is a preservative that is commonly applied to meat products, thus probably leading to elevated concentrations of this compound in meat processing effluents [35]. The COD content was the main differentiating feature between the total and soluble fractions of the collected wastewater. With the centrifugation and filtration of the raw wastewater, part of the organic content in the solid form was removed, lowering the COD content of the latter. The bacterial community present in MPWW from sampling campaign 1 was also evaluated, showing a CFU count of 1.05 × 107 CFU mL−1. There was a wide variation in the nutrient content of wastewater produced over time, but the wastewater was found to contain adequate quantities of total nitrogen and phosphorus to support microalgal growth [36].

3.2. Microalgae Growth in Raw MPWW

The cultivable microalgae strains that predominate within the consortium belong to two different genera of the phylum Chlorophyta and class Trebouxiophyceae, namely Micractinium sp. and Chlorella sp. (Figure S2), commonly used in phycoremediation processes of wastewater. Lu et al. (2015) reported the use of Chlorella sp. for nutrient removal and microalgal biomass production in individual and mixed samples of MPWW collected in distinct parts of the process [37]. Chlorella sp. and Micractinium sp. have also been used for nutrient removal from the primary effluent wastewater and high-strength wastewater consisting of a mixture of anaerobic digestion centrate and primary wastewater [38].

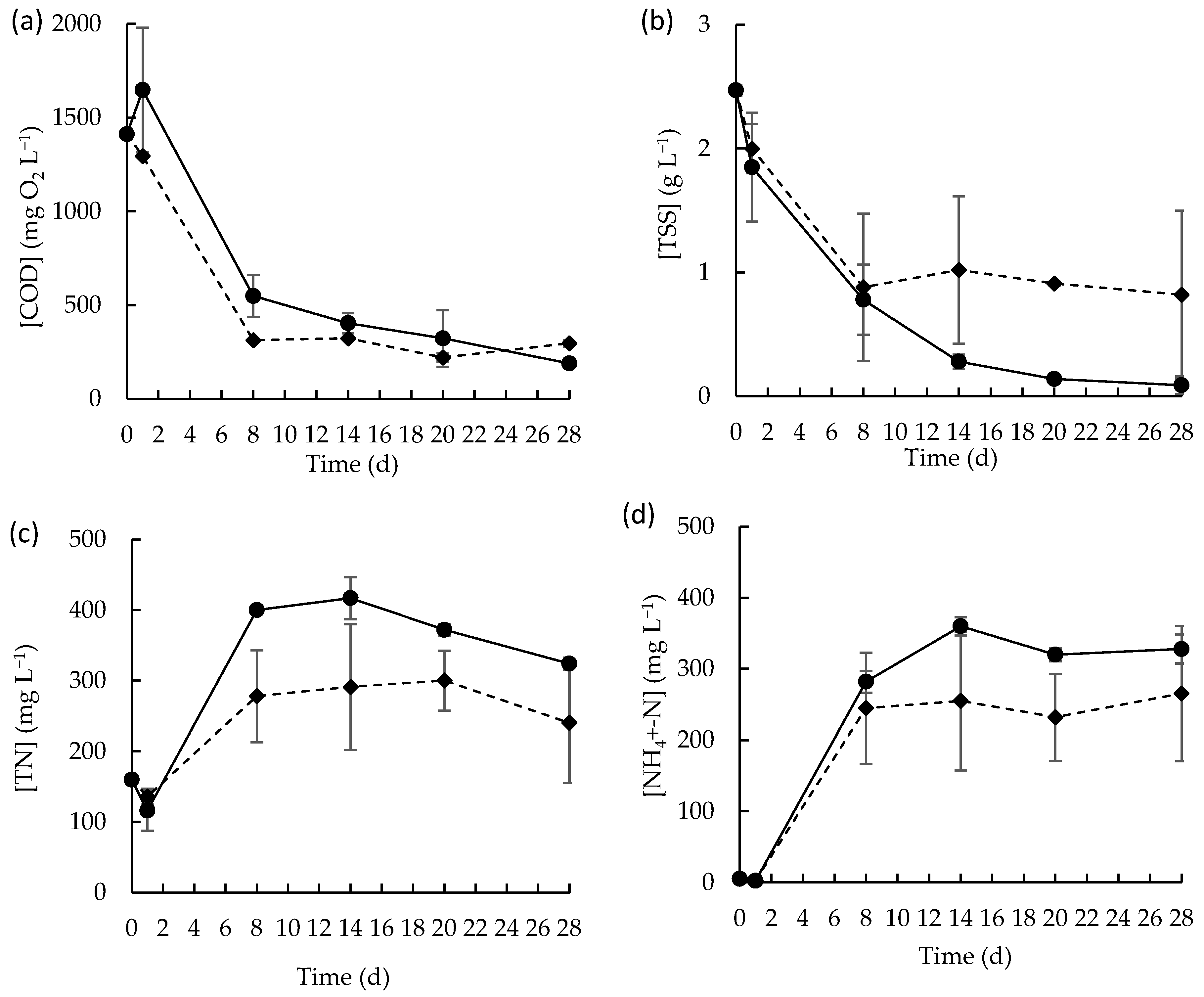

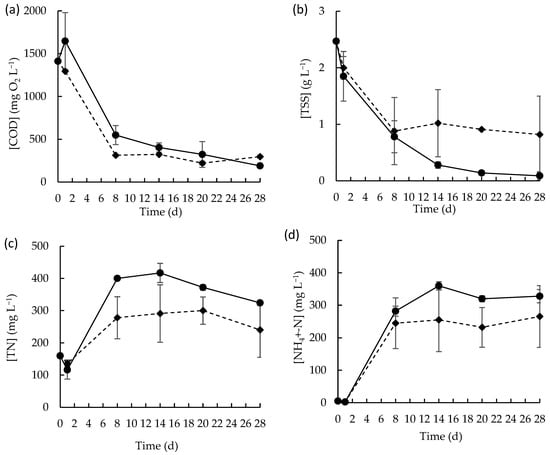

Referring to the microalgae consortium capacity to thrive in the presence of the native microbial community within MPWW, the carbon and nutrient removal profiles over time were followed (Figure 2). The COD removal from the soluble fraction occurred either in the presence or in the absence of the microalgae consortium (Figure 2a). In fact, acting alone, the native microbial community of the MPWW was able to remove carbon at a removal rate of 107.8 ± 13.9 mg L−1 d−1 during the first eight days of the batch assay. However, in the presence of microalgae consortium, the COD removal occurs at a slightly higher rate (ca. 137.3 ± 0.0 mg L−1 d−1, during the first eight days of the batch assay), showing that the microalgae consortium was able to compete with the well-established native community within the wastewater for removing carbon. This shows that the microalgae consortium can thrive in the presence of the native wastewater microbiota and maintain its metabolic capacity, which seemed to be beneficial for a more pronounced decrease in COD, in line with what is reported in the literature [39,40]. The capability of microalgae to reduce the COD concentration in various types of wastewaters, with high efficacy, was already described in several studies. Latiffi et al. (2021) reported that Scenedesmus sp. was able to remove about 99% of COD from pre-sterilized MPWW with a maximum COD initial concentration of 3638 mg L−1 [7]. Hu et al. (2019) also reported that a microalgae consortium composed by Chlorella protothecoides, Scenedesmus obliquus, and Chlorella vulgaris achieved high COD removal capacity (ca. 91%), using wastewater with an initial COD concentration of 6450 mg L−1 [41]. In the present study, after 8 days, the COD removal rates decreased considerably when compared to the initial period of incubation, with or without the presence of the microalgae consortium (0.8 ± 0.8 mg L−1 d−1 and 17.9 ± 1.1, respectively). During the first 8 days, approximately 61% and 78% of the soluble COD content in the initial MPWW was consumed by the native community and by the native community in combination with the microalgae consortium, respectively. From day 8 onwards, the soluble COD content remained stable without major changes (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Concentration profile of (a) soluble COD, (b) TSS, (c) TN, and (d) NH4+-N in raw MPWW in the presence (◆) or in the absence (●) of the microalgae consortium for 28 days. Data points represent the mean of duplicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

The MPWW is often characterized by a high content of solid fraction composed by organic materials, including proteins, fats, and other nitrogen-rich compounds. Over time, this solid fraction was decomposed, as corroborated by the evolution of TSS in both batch conditions (Figure 2b), with TSS content decreasing over the first days of experiment and then stabilizing. The resulting soluble organic material in the medium probably suffered microbial decomposition which led to the release of nitrogenous compounds, primarily in the form of ammonia, whose concentration sharply increased over the first 8 days of cultivation (Figure 2d). This increase in ammonia concentration contributed to the overall increase in TN content in wastewater over the same period (Figure 2c). Ammonifying bacteria, which are common in protein-rich wastewaters such as MPWW, probably contributed to this process by decomposing nitrogenous organic compounds (e.g., proteins) and releasing ammonia [42]. The lower concentrations of TN and ammonium observed in the batch assays conducted in the presence of the microalgae-based consortium suggest that it contributed effectively to nitrogenous form’s removal processes. Additionally, the concentrations of nitrite- and nitrate-nitrogen at the beginning of the batch experiment were very low, around 1.2 and 9.0 mg L−1, respectively, and over time they decreased to residual levels (Figure S3), indicating the absence of substantial nitrification. Also, the pH values (Figure S3) showed an increasing tendency towards alkalinity in both conditions, with values of approximately 9.1 ± 0.0 mg L−1 and 9.01 ± 0.1 mg L−1 in the absence and presence of the microalgae consortium probably due to the ammonification [43].

Microalgae biomass growth was also evaluated through photosynthetic pigment quantification, namely chlorophyll a, b and carotenoids. In terms of total pigments, a maximum of 5.7 ± 0.5 µg mL−1 was obtained on day 20 (reflecting a pigment productivity of about 2.5 × 10−4 ± 3.0 × 10−5 g L−1 d−1), slightly decreasing thereafter.

When dealing with real wastewater that contains a solid fraction, the matrix heterogeneity can affect the replicability and consistency of batch assays. The non-uniform distribution of solids in the wastewater often leads to inconsistency in the sample composition as it is difficult to ensure that each replicate contains similar concentrations of solids, which can ultimately affect the biological assay.

3.3. Microalgae Growth in Sieved and Sedimented Wastewater

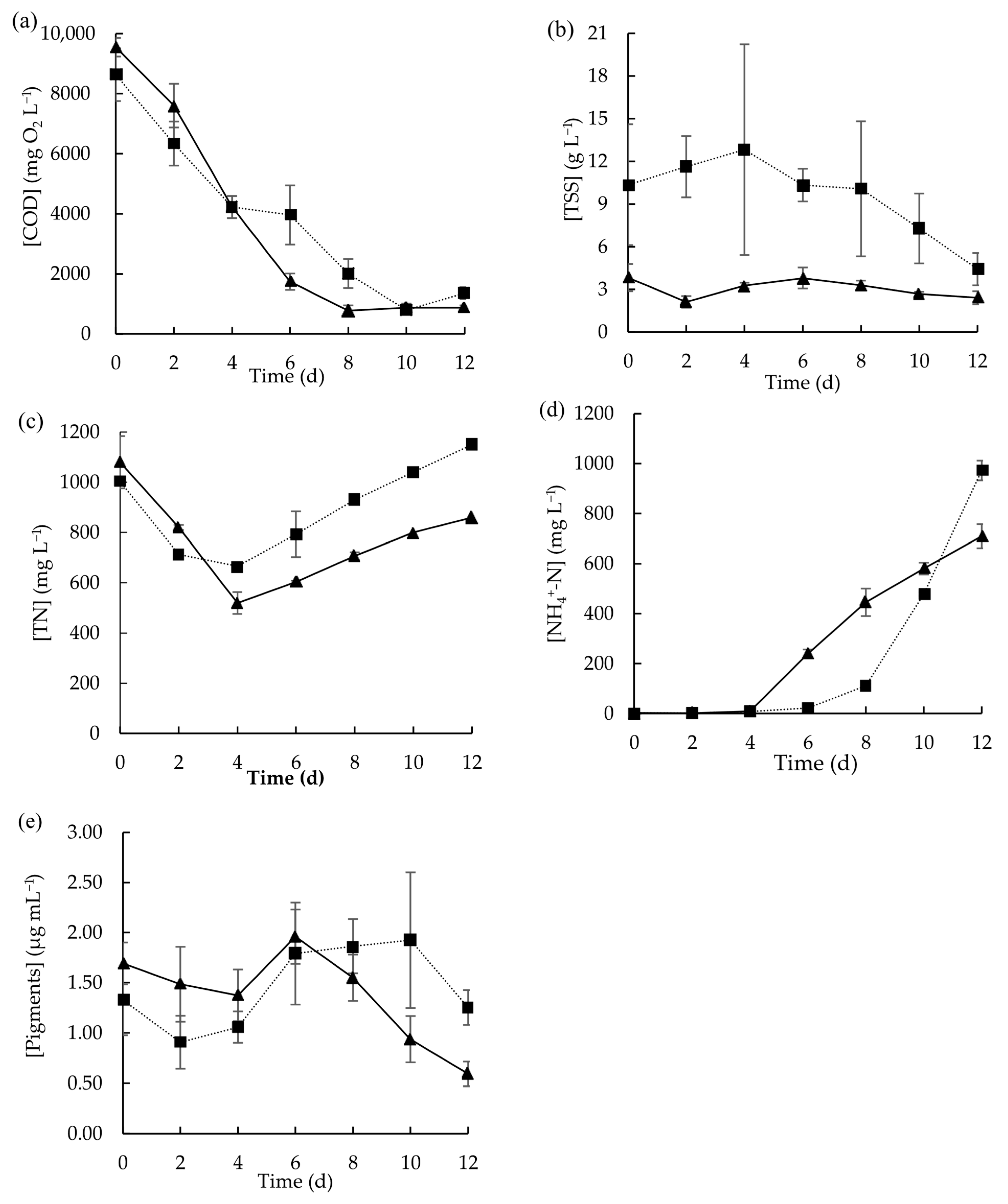

To understand how the growth of microalgae and its ability to remove nutrients are affected by the presence of suspended solids in wastewater that can cause matrix heterogeneity, a batch experiment was conducted by inoculating the microalgae consortium in raw MPWW and in sieved and sedimented MPWW (Figure 3). Suspended solid removal and sedimentation may slightly alter the composition and distribution of solids in the wastewater, which in turn can affect the organic matter content. The presence of solids did not affect microalgae capacity in removing carbon as the concentration of soluble COD decreased from the beginning in both test conditions (Figure 3a). Nevertheless, during the first 8 days, the COD removal rate achieved using sieved and sedimented MPWW was 1097.5 ± 22.2 mg L−1 day−1, which was higher than that using raw wastewater (828.5 ± 60.5 mg L−1 d−1), representing an approximated increase of 32.5%. The pre-treatment applied to the raw wastewater reduced the initial TSS content of the wastewater substantially (Figure 3b). Although the solid fraction was removed in one of the tested conditions, the initial soluble COD concentrations were not substantially different as the solids were not considered for the measurements. The lower COD consumption rate obtained using raw MPWW could be due to the solids’ gradual dissolution which gradually increased the carbon available in the medium. In fact, over time, a reduction in TSS concentration was concomitantly observed in the condition that uses raw wastewater (Figure 3b). In addition, perhaps the solids in wastewater can adsorb the compounds available in the medium, thus decreasing their bioavailability.

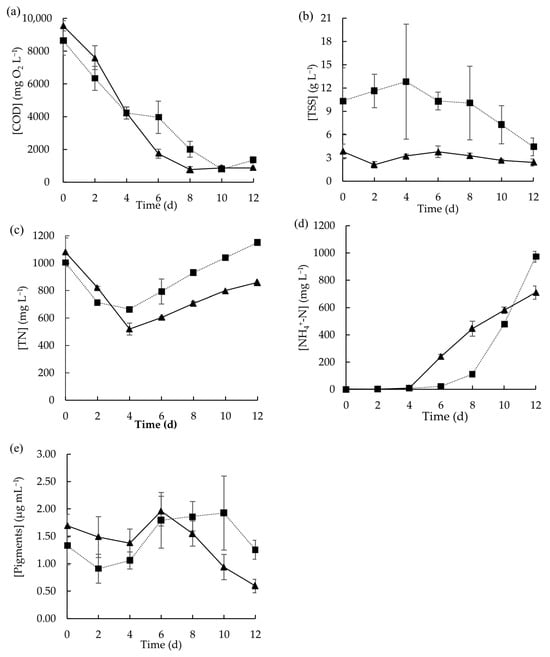

Figure 3.

Concentration profiles of (a) COD, (b) TSS, (c) TN, (d) NH4+-N, and (e) total pigments obtained during the growth of microalgae in raw MPWW (■) and in sieved and sedimented MPWW (▲) over 12 days. Data points represent the mean of triplicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

For TN concentration, either using raw or sieved and sedimented MPWW, it initially decreased but then started to increase after day 4 (Figure 3c). Until day 4, although a decrease in TN concentrations occurred in both tested conditions, in the same period, no increase in the ammonium content was observed, which led to the hypothesis that this nitrogen form was assimilated by microalgae. From day 4 onwards, the TN content increased, probably due to the breakdown of proteins and further ammonium liberation due to ammonification, with this increase being more pronounced in the raw MPWW due to its higher initial TSS concentration [42]. Subsequently, ammonium concentrations rose in both tested conditions. Nevertheless, with sieved and sedimented MPWW, this increase began on day 6, whereas with raw MPWW, this pattern started to occur later on day 8. In both cases, the data suggest that microalgae ceased consuming ammonium after these points. This could be due to the high pH achieved (8.9 ± 0.1 mg L−1 in raw MPWW and 9.2 ± 0.1 mg L−1 in sieved and sedimented MPWW) (Figure S4), as it can affect the equilibrium between ammonium and free ammonia that shifts towards the latter. Free ammonia is known to cause the inhibition of photosynthesis, thus hampering some physiological processes of the microalgae including the uptake of ammonium [44]. In fact, in the present study, inhibition of the ammonium uptake occurred simultaneously with the total pigment content decay (Figure 3e).

Nitrite concentrations in both types of wastewaters were low (3.4 ± 0.0 mg L−1) at the beginning and tended to decrease. From day 4 onwards, only a residual concentration was detected in the medium of both test conditions (Figure S4). Nitrate concentrations, which were slightly higher at the beginning (7.4 ± 0.3 mg L−1 in raw MPWW and 7.3 ± 0.5 mg L−1 in sieved and sedimented MPWW), followed a similar trend to nitrite (Figure S4).

Regarding biomass growth, similar pigment concentrations were achieved but that happened in different days: in sieved and sedimented MPWW, by day-6 (1.96 ± 0.27 µg mL−1); and in raw MPWW, by day-10 (1.92 ± 0.68 µg mL−1). By removing the suspended solids, microorganisms can more easily take advantage of the nutrients and carbon dissolved in wastewater, without having to manage being trapped and aggregated to meat and/or fat fragments that can hinder the uptake of these compounds. Therefore, this strategy could have benefitted biomass growth and, therefore, pigment production, representing the beneficial effect of removing solids in terms of microalgal growth acceleration. Previously, Wang et al. (2022) also reported that the use of unsterilized cattle farm wastewater previously filtered was more favorable for microalgae cultivation than using the raw version of that wastewater; the filtering process allowed the decrease in turbidity and TSS content of the wastewater, further improving the adaptability of microalgae to the feedstock [45]. Either using sieved and sedimented or raw MPWW, after maximum pigment concentration was achieved, pigment content started to decrease.

3.4. Microalgae Cultivation in a Raceway Under Fed-Batch Mode

3.4.1. Wastewater Treatment Performance and Biomass Productivity

The microalgae growth and removal performance were evaluated for 62 days in a raceway system, in fed-batch mode, under varying wastewater compositions. In each fed-batch cycle, a new batch of grinded wastewater that was subsequently sieved and sedimented was added (Table 2). This later step was conducted to ensure the feeding with a more homogenous feedstock medium, where carbon and nutrients can be more readily available for consumption. The freeze–thaw cycle of each wastewater feeding batch promoted the crystallization of solids. According to Gao (2011), the small and dissolved particles tend to form aggregates in this frozen status, resulting in larger pieces, altering the size and distribution of the solid particles and the composition of the soluble fraction (e.g., soluble COD, that exhibits an increase) [46]. As such, the wastewater was sieved and sedimented to remove these solids from the feedstock.

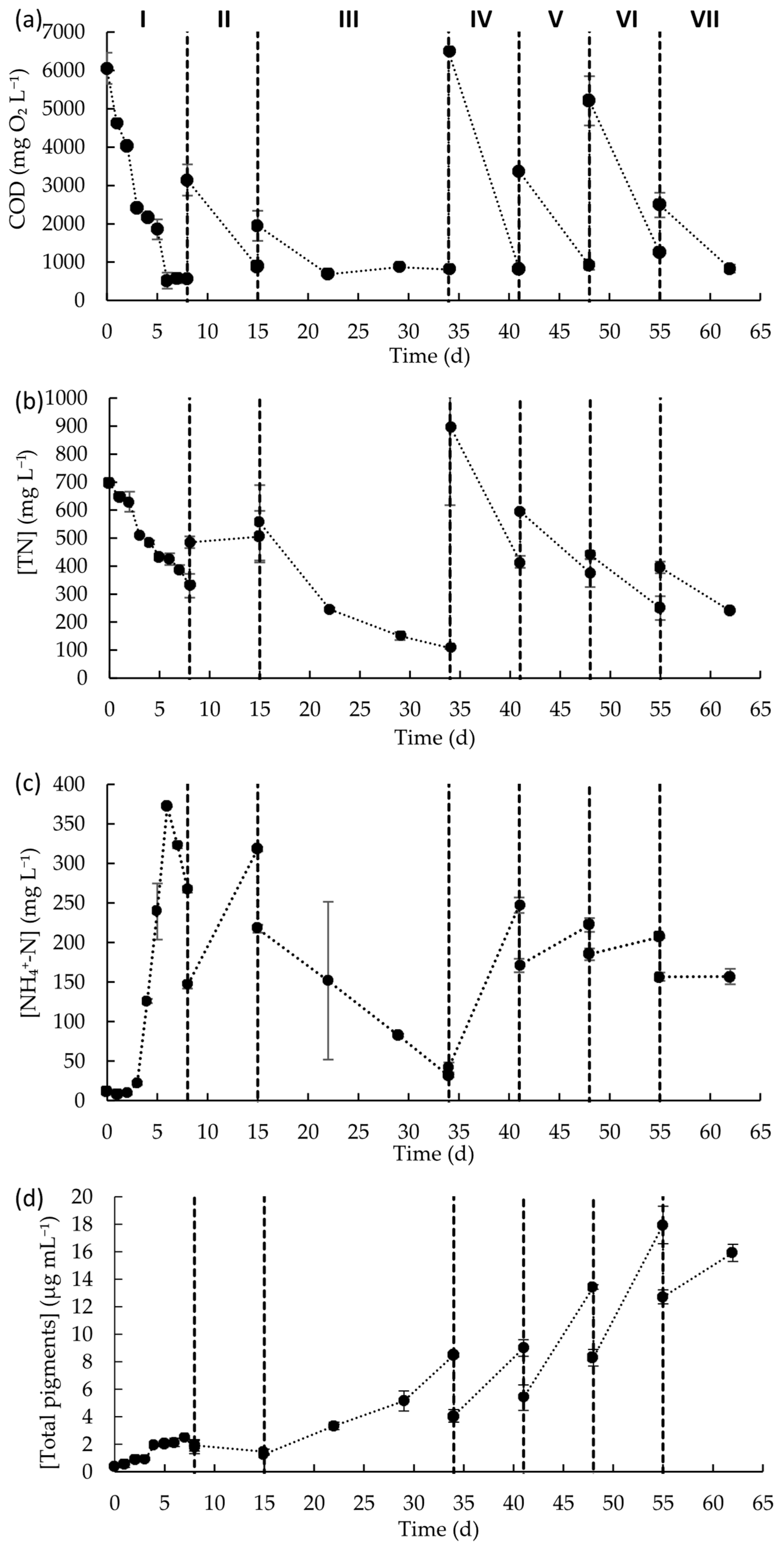

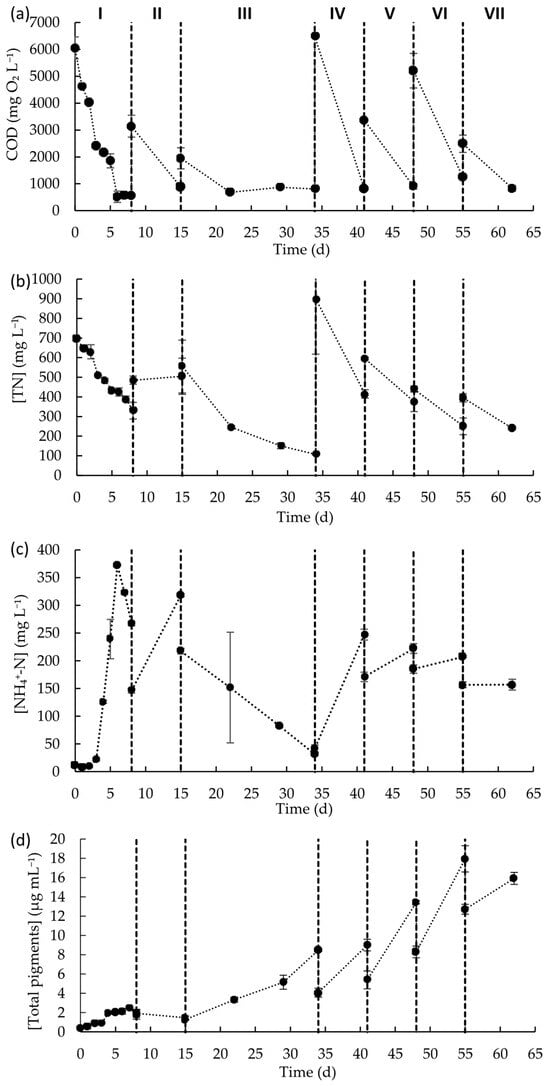

Carbon and nutrients’ concentration profiles were monitored throughout the experimental period (Figure 4). The COD concentration decreased in each fed-batch cycle, independently of the initial COD concentration in the initial wastewater, with removal rates within the range of 181.3 to 806.3 mg L−1 d−1 (Table 3). These rates reflect the capability of microalgae to grow in wastewater with high and variable concentrations of COD and to maintain the removal capacity over time. This is particularly important for process scalability, as real-world wastewater compositions fluctuate daily and require resilient treatment systems. Interesting, although in each fed-batch cycle there was a notorious reduction in COD levels, the content of COD in the culture medium at the end of the fed-batch cycle was, on average, 868 ± 199 mg L−1. Even in fed-batch cycle III, that lasted for 19 days, after 7 days of cultivation, it seems that the microalgal culture was no longer able to consume the available carbon.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of (a) COD, (b) TN, (c) NH4+-N, and (d) total photosynthetic pigments during the seven fed-batch cycles of the raceway operation. Data points represent the mean of duplicates and error bars represent the standard deviation.

Table 3.

COD, TN and TSS loading rates, COD and TN removal rate, COD removal efficiency, and microalgae biomass productivity (based on photosynthetic pigments concentration) for each raceway fed-batch cycle.

TN concentrations decreased in almost each fed-batch cycle (except in fed-batch cycle II). Considering the TN content and the low content of ammonium, nitrate, and nitrite ions in wastewater at the beginning of each fed-batch cycle, most of the organic nitrogen in wastewater was in the form of proteins. In most of the cycles, there was a reduction in the TN content, but the content of ammonium ions increased, indicative ammonium liberation to the medium due to the breakdown of proteins occurring. Nevertheless, it is important to notice that, considering the nitrogen mass balance, the overall reduction in the TN content was higher than the content of ammonium, nitrate, and nitrite ions that remained in the medium, meaning that these nitrogen forms, especially ammonium, were consumed by the microalgal-based biomass. Only in fed-batch cycle III, which lasted 19 days, was a decrease in the TN concentration observed along with a reduction in ammonium concentration. Ammonium content decreased by ca. 86%, indicating that all ammonium ions that resulted from nitrogenous organic compound decomposition were consumed by the microalgae-based consortium. For the remaining fed-batch cycles, it seems that the ammonium released was consumed just up to a certain level, then the microalgal- based biomass was no longer able to consume it, leading to its accumulation in the culture medium. In fed-batch cycle II, the absence of TN removal may be associated with inhibition by free ammonia (NH3). The increase in NH4+ concentration, together with the rise in pH (from 7.3 to 8.7), likely shifted the NH4+/NH3 equilibrium toward inhibitory free ammonia, which can diffuse into cells and impair metabolism, thereby reducing nitrogen uptake and microalgal growth. It is important to note that tolerance to ammonium and free ammonia is taxon-specific, with different algal groups exhibiting distinct sensitivity levels [47]. Moreover, Rossi et al. [44] reported that mixed microalgae–bacteria consortia generally exhibit greater tolerance to free ammonia than monocultures, suggesting that mixed-culture conditions may select more robust and resilient strains.

In what concerns the COD and TN concentrations, at the end of each fed-batch cycle, is that the minimum levels obtained for each parameter did not reach the legal discharge limits established in Europe, which are 125 mg L−1 for COD and 10–15 mg L−1 for TN [48]. In this way, further treatment of the resulting effluent should be performed. Nevertheless, this operation mode can be useful for producing microalgal biomass from a waste and as a first step of MPWW treatment. Importantly, the very wide ranges observed for COD, TN, and TSS throughout raceway operation highlight the challenges associated with real wastewater, whose composition fluctuates daily, a factor that is particularly relevant when considering process scalability.

Total pigment concentration mostly increased over time (Table 3) with biomass productivity in each feeding cycle ranging from 1.8 × 10−4 to 1.4 × 10−3 g L−1 d−1. This reflects the constant growth of microalgae biomass along the different cycles of raceway operation and a gradual adaptation to wastewater characteristics. It can be inferred that the addition of a new batch of wastewater, independently of its initial physico-chemical composition, provides carbon and nutrients that can be used by the microalgae biomass for growth. On day 55, a maximum pigment concentration of 1.8 × 10−2 g L−1 was achieved, representing a 45-fold increase in microalgae biomass when compared to the initial biomass content. Kim et al. (2014) reported a maximum chlorophyll concentration of approximately 5.5 × 10−3 g L−1 when feeding a microalgae consortium with real municipal wastewater in a high-rate raceway pond operated under a semicontinuous feeding mode [49]. In the present study, superior productivity was achieved and real MPWW seems to be a good alternative for the cultivation of microalgae biomass, thus allowing for the valorization of this waste stream. However, it should be noted that biomass characterization in this work was limited to pigment content as a proxy for microalgal growth. Direct quantification of biomass, such as TSS, cell counts, or biochemical composition analyses (e.g., lipid and protein content), was not performed. Although the manuscript discusses biomass valorization and circular economy aspects, these remain to be validated through detailed compositional analysis and techno-economic assessment. Nevertheless, it is well known that the production of microalgal biomass as a by-product can offer opportunities for recovery through its conversion into other value-added compounds. Several approaches for the valorization of microalgae biomass as a by-product from wastewater treatments are under discussion, such as bioenergy production through anaerobic digestion, hydrothermal processes, lipid extraction, applications in agriculture as biostimulants or soil amendments, and extraction of bioactive compounds, such as carotenoids [50]. Some studies have already reported strategies for the valorization of the biomass produced from an MPWW treatment context. Castro et al. (2021) reported the hydrothermal carbonization of microalgae biomass cultivated in high-rate algal ponds during treatment of meat processing industry wastewater for energy obtention, with a yield of 16.99−17.47 MJ kg−1 [51]. In a study exploring biomass valorization for biodiesel production, researchers cultivated microalgae using a mixture containing up to 90% of abattoir water discharge supplemented with synthetic media, reporting that higher proportions of abattoir wastewater resulted in increased levels of saturated fatty acids in the microalgal biomass. Moreover, the biodiesel produced complied with the American and European fuel quality standards [52]. Silva et al. (2023) [53] reported a soil application for microalgae biomass produced during MPWW treatment. The dry biomass, in a 2% dose, led to higher basal soil respiration, soil enzymatic activity (β-glucosidase, acid phosphatase, arylsusslfatase), microbial biomass carbon, and plant growth [53].

3.4.2. Eukaryotic Community Composition

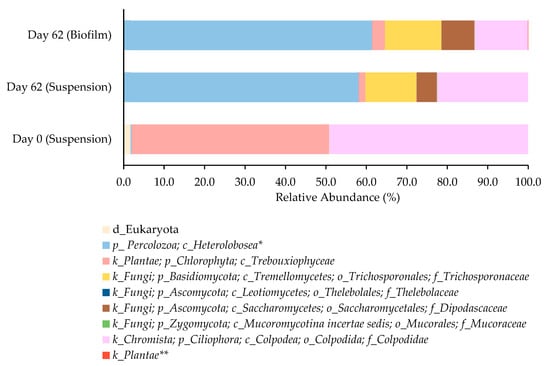

The evolution of the Eukaryotic community of the microalgae-based consortium over the raceway operation followed (Figure 5). A total of seven eukaryotic taxa that could be assigned at least at the class level was identified.

Figure 5.

Relative abundance of the identified taxonomic groups within the suspended biomass established in the raceway (day 0 and day 62) and in the biofilm formed (day 62). All the taxonomic groups belong to the domain Eukaryota and the lowest taxonomic rank identified is presented. * class belonging to the Tetramitia clade; ** sub kingdom Chloroplastida.

The raceway was inoculated with a microalgae-based consortium mainly composed by the green alga of the Trebouxiophyceae class (phylum Chlorophyta), with a relative abundance of 48.9%, and ciliated organisms of the family Colpodidae (phylum Ciliophora), with a relative abundance of 49.2% (Figure 5). In the inoculum, members of the class Heterolobosea (phylum Percolozoa) were also detected, although at an extremely low relative abundance (ca. 0.2%). The presence of protozoan ciliates in microalgae-based cultures is very common. Ciliate presence is often related to the high capacity of systems in removing suspended solids and pathogens present in wastewater, improving water quality [54] and, depending on the species of ciliates present, they can consume both bacteria and microalgae. The ones of the class Colpodea are primarily bacterivorous. Given their bacterivorous nature, Colpodea ciliates generally have a beneficial or neutral impact on microalgae cultures which can explain the high relative abundance of such eukaryotic taxon in the inoculum. In fact, an effective biological method for controlling bacterial contaminants without degrading the microalgal biomass is the addition of Colpoda sp. [55].

After 62 days of raceway operation, the microbiome of the microalgae-based consortium shifted and by the end of the operation, it harbored a higher diversity of eukaryotic taxa (Shannon index of 0.91 and 1.22 on Day 0 and Day 62, respectively), but it was dominated by non-microalgal eukaryote taxa. There was a substantial decrease in the relative abundance of the phylum Chlorophyta, which achieved a relative abundance of 1.7%. It is important to notice that this does not imply a reduction in microalgal biomass and in fact, increased pigment concentrations were observed over raceway operation, indicating that microalgae remained metabolically active and likely increased in absolute biomass, despite their lower relative abundance in the microbiome profile. A similar trend, although less pronounced, was observed for the phylum Ciliophora, with a decrease in relative abundance up to 22.5% in relation to the inoculum. By the end of raceway, the community became richer in organisms, including protozoan grazers and fungi-like members of the class Heterolobosea (phylum Percolozoa), and of the family Trichosporonaceae (phylum Basidiomycota) and family Dipodascaceae (phylum Ascomycota), respectively. In fact, members of the class Heterolobosea were predominant either in the microbiome of the suspension and biomass. Zhang et al., 2023, reported that in an outdoor open raceway pond, 3 to 4 days after inoculation, the culture color changed from light brown to light yellow, with microscopic inspection revealing the presence of an algivorous amoeba [56]. In that case, the presence of the amoeba upon a certain concentration (approximately 1.0 × 104 cells mL−1) had a devastating impact on microalgae growth, with the microalgae biomass dry weight falling significantly. In addition, authors stated that, generally, the predatory amoeba contamination occurred from late spring to late autumn (highest temperature, 38 °C; lowest temperature, 12 °C). In another study, the heterolobosean amoeba was identified as the most frequently occurring and destructive predator in Phaeodactylum tricornutum microalgae cultures in raceway ponds [57]. Authors reported that the addition of NH4HCO3 at 400 mg L−1 can be used as an effective control measure to inhibit amoeba proliferation with little impact on microalgal growth. Although both studies stated that contamination with members of the class Heterolobosea can cause the rapid crash of the microalgae culture, in the present study, a continuous growth of the microalgae-based consortium occurred as revealed by the increase in total pigment content, and no color change in the culture was observed in the timeframe of the raceway operation. This suggests that a well-structured eukaryotic community was established, in which eukaryotic diversity may support system stability. Open cultivation systems are more prone to contamination and the use of non-sterile wastewater brings even more complexity for the raceway operation. In such an environment, numerous microbial interactions with fungi, yeast, or bacteria can occur and if some of those interactions are beneficial, like those that promoted pollutant consumption, others can harm microalgae. In the present study, over raceway operation, it seems that a mixed microbial culture consisting of microalgae and yeast was developed. In fact, members of the families Trichosporonaceae and Dipodascaceae were identified in the raceway biomass with a relative abundance of 12.6 and 5.0%, respectively. Although the presence of microorganisms belonging to the Fungi kingdom can be perceived as possible contamination, recently, there are several reports that stated that mixed microbial cultures, in which microalgae grow in symbiosis with fungi or yeast, are beneficial for the treatment of wastewater [58]. In those systems, the interactions between the different microorganisms allowed the upgrading of the biological removing processes. The use of non-sterile feedstocks like wastewater, although representing an excellent opportunity for valorization, is challenging. Thus, the presence of microorganisms with different metabolic capabilities can be a way to overcome the difficulty in removing some more complex compounds from wastewater, leveraging the strengths of each organism to enhance overall pollutant removal. Nevertheless, in the present study, this hypothesis remains provisional and highlights the necessity for further functional confirmation.

4. Conclusions

MPWW is a suitable feedstock for microalgae-based valorization strategies, in spite of its inherent compositional variability. The native bacterial community present in raw MPWW contributed to the remediation process, but the presence of the microalgae-based consortium boosted the COD removal rates by 29.2 mg L−1 d−1. Additionally, the microalgae biomass was able to thrive and proliferate in the presence of the native microbial community of wastewater. Either using raw or sieved and sedimented MPWW, carbon and TN removal occurred but higher rates were achieved by using sieved and sedimented wastewater, as carbon and nutrients are more readily available for microorganism metabolization. In fact, pigment production would have achieved the maximum production earlier if sieved and sedimented wastewater was used.

In a raceway system under fed-batch, pigment production progressively increased over time. In each fed-batch, carbon and TN consumption occurred independently of the physico-chemical composition of the wastewater used as feedstock. The microbiome of the microalgae-based consortium used as inoculum, over operation, shifted to a more diverse community. Beyond microalgae taxa, other eukaryotic taxa (yeast and fungi) became part of the biomass microbiome; however, while their presence may indicate potential ecological interactions, their specific functional contribution to remediation processes cannot be inferred.

MPWW can serve as a suitable feedstock for microalgae cultivation, enhancing biomass production potential from an industrial waste. Microalgae can assimilate nitrogen and organic compounds from MPWW, converting the pollutants into biomass, estimated indirectly via pigment concentration as a proxy. However, as this was exploratory work, it presents inherent limitations: replication was restricted, community analysis focused only on eukaryotic taxa (18S rRNA), and biomass characterization relied on pigment concentration. While these approaches are appropriate for a proof-of-concept study, future research should address these aspects to strengthen process feasibility and valorization potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cleantechnol8010020/s1, Figure S1: Visual appearance of wastewater following collection at the meat processing facility on different sampling days; Figure S2: Neighbour-joining phylogenetic tree based on 18S rRNA gene sequences; Figure S3: Concentration profiles of nitrite-nitrogen and nitrate-nitrogen and pH in raw MPWW in the presence or in the absence of the microalgae consortium for 28 days; Figure S4: Concentration profiles of nitrite-nitrogen and nitrate-nitrogen and pH obtained during the growth of microalgae in raw MPWW and in sieved and sedimented MPWW over 12 days.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.O., P.M.L.C. and C.L.A.; methodology, A.S.S.S., A.S.O. and C.L.A.; validation, A.S.O., P.M.L.C. and C.L.A.; formal analysis, A.S.S.S., A.S.O. and C.L.A.; investigation, A.S.S.S. and A.S.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.S.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S.O., P.M.L.C. and C.L.A.; visualization, A.S.S.S. and C.L.A.; funding acquisition, P.M.L.C., supervision, A.S.O. and C.L.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Funds from FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through project MobFood—Mobilizing scientific and technological knowledge in response to the challenges of the agri-food market (POCI-01-0247-FEDER-024524/SI-47-2016-10).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the CBQF scientific collaboration under the FCT project UID/50016/2025. Catarina Amorim thanks FCT for the Assistant Researcher contract (2023.15056.TENURE.048) through the FCT-TENURE Program funded by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MPWW | Meat Processing Wastewater |

| COD | Chemical Oxygen Demand |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| TSS | Total Suspended Solids |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| PO43−-P | Phosphate |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium |

| NO3−-N | Nitrate |

| NO2−-N | Nitrite |

| CFUs | Colonies forming units |

| PCR | Polymerase chain reaction |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

References

- Bustillo-Lecompte, C.F.; Mehrvar, M. Slaughterhouse wastewater characteristics, treatment, and management in the meat processing industry: A review on trends and advances. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 161, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Tomasevic, I. Environmental impacts of the meat chain–Current status and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 54, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, C.J.; Wang, Z. Treatment of meat wastes. In Handbook of Industrial and Hazardous Wastes Treatment; CRC Press: London, UK, 2004; pp. 685–718. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C.F.; Amorim, C.L.; Duque, A.F.; Reis, M.A.; Castro, P.M. Valorization of wastewater from food industry: Moving to a circular bioeconomy. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2022, 21, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plöhn, M.; Spain, O.; Sirin, S.; Silva, M.; Escudero-Oñate, C.; Ferrando-Climent, L.; Allahverdiyeva, Y.; Funk, C. Wastewater treatment by microalgae. Physiol. Plant. 2021, 173, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Ngo, H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.; Nguyen, D.; Kumar, S. Microalgae biomass from swine wastewater and its conversion to bioenergy. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 275, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latiffi, N.A.A.; Mohamed, R.M.S.R.; Al-Gheethi, A.; Tajuddin, R. Harvesting of Scenedesmus sp. after phycoremediation of meat processing wastewater; optimization of flocculation and chemical analysis of biomass. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2021, 96, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latiffi, N.A.A.; Mohamed, R.; Shanmugan, V.A.; Pahazri, N.F.; Kassim, A.; Matias-Peralta, H.; Tajuddin, R. Removal of nutrients from meat food processing industry wastewater by using microalgae Botryococcus sp. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2016, 11, 9863–9867. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, D.; Riaño, B.; Coca, M.; Solana, M.; Bertucco, A.; García-González, M. Microalgae cultivation in high rate algal ponds using slaughterhouse wastewater for biofuel applications. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 285, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Z.; Shu, Q.; Takala, J.; Hiltunen, E.; Feng, P.; Yuan, Z. Nutrient removal and biodiesel production by integration of freshwater algae cultivation with piggery wastewater treatment. Water Res. 2013, 47, 4294–4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saïdane-Bchir, F.; El Falleh, A.; Ghabbarou, E.; Hamdi, M., 3rd. generation bioethanol production from microalgae isolated from slaughterhouse wastewater. Waste Biomass Valorization 2016, 7, 1041–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, B.K.; Hamawand, I.; Harris, P.; Baillie, C.; Yusaf, T. A case study for biogas generation from covered anaerobic ponds treating abattoir wastewater: Investigation of pond performance and potential biogas production. Appl. Energy 2014, 114, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-M.; Chen, T.-Y.; Lin, T.-H.; Kao, C.-Y.; Lai, J.-T.; Chang, J.-S.; Lin, C.-S. Cultivation of Chlorella sp. GD using piggery wastewater for biomass and lipid production. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 194, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.; Marques, P.; Ribeiro, B.; Assemany, P.; de Mendonça, H.V.; Barata, A.; Oliveira, A.C.; Reis, A.; Pinheiro, H.M.; Gouveia, L. Combining biotechnology with circular bioeconomy: From poultry, swine, cattle, brewery, dairy and urban wastewaters to biohydrogen. Environ. Res. 2018, 164, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rayen, F.; Behnam, T.; Dominique, P. Optimization of a raceway pond system for wastewater treatment: A review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2019, 39, 422–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Le-Clech, P.; Henderson, R.K. Characterisation of microalgae-based monocultures and mixed cultures for biomass production and wastewater treatment. Algal Res. 2020, 49, 101963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, A.T.; Cardador, M.; Santorio, S.; Arregui, L.; Sicuro, B.; Mosquera-Corral, A.; Castro, P.M.; Amorim, C.L. Cultivable microalgae diversity from a freshwater aquaculture filtering system and its potential for polishing aquaculture-derived water streams. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 132, 1543–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Rosenberg, J.N.; Faruq, J.; Betenbaugh, M.J.; Xia, J. An improved colony PCR procedure for genetic screening of Chlorella and related microalgae. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 33, 1615–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitou, N.; Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jukes, T.H.; Cantor, C.R. Evolution of protein molecules. Mamm. Protein Metab. 1969, 3, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposo, M.F.d.J.; Oliveira, S.E.; Castro, P.M.; Bandarra, N.M.; Morais, R.M. On the utilization of microalgae for brewery effluent treatment and possible applications of the produced biomass. J. Inst. Brew. 2010, 116, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchobanoglous, G.; Stensel, H.D.; Tsuchihashi, R.; Burton, F.L.; Abu-Orf, M.; Bowden, G.; Pfrang, W.; Metcalf & Eddy. Wastewater Engineering: Treatment and Resource Recovery; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, G.; Dighe, S.N.; Perry, W.B.; Stenhouse, E.H.; Jones, D.L.; Kille, P.; Weightman, A.J. Wastewater sample storage for physicochemical and microbiological analysis. J. Virol. Methods 2025, 332, 115063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. APHA: Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; United Book Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.; Silva, A.; Rocha, J. Extraction and quantification of pigments from a marine microalga: A simple and reproducible method. Commun. Curr. Res. Educ. Top. Trends Appl. Microbiol. Formatex 2007, 2, 586–593. [Google Scholar]

- Miazek, K.; Ledakowicz, S. Chlorophyll extraction from leaves, needles and microalgae: A kinetic approach. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2013, 6, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Sumanta, N.; Haque, C.I.; Nishika, J.; Suprakash, R. Spectrophotometric analysis of chlorophylls and carotenoids from commonly grown fern species by using various extracting solvents. Res. J. Chem. Sci. 2014, 2231, 606X. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, A.S.; Alves, M.; Leitao, F.; Tacao, M.; Henriques, I.; Castro, P.M.; Amorim, C.L. Bioremediation of coastal aquaculture effluents spiked with florfenicol using microalgae-based granular sludge—A promising solution for recirculating aquaculture systems. Water Res. 2023, 233, 119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-Y.; Haynes, R. Origin, nature, and treatment of effluents from dairy and meat processing factories and the effects of their irrigation on the quality of agricultural soils. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 41, 1531–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristian, O. Characteristics of the untreated wastewater produced by food industry. Analele Univ. Din Oradea Fasc. Prot. Mediu. 2010, 15, 709–714. [Google Scholar]

- Abyar, H.; Younesi, H.; Bahramifar, N.; Zinatizadeh, A.A. Biological CNP removal from meat-processing wastewater in an innovative high rate up-flow A2O bioreactor. Chemosphere 2018, 213, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.C.S.; Martins, T.D.D.; Batista, E.S.; Santos, E.P.; Silva, F.A.P.; Araújo, Í.B.S.; Nascimento, M.C.O. Physicochemical and microbiological parameters of dried salted pork meat with different sodium chloride levels. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 33, 382–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Glorieux, S.; Goemaere, O.; Steen, L.; Fraeye, I. Phosphate reduction in emulsified meat products: Impact of phosphate type and dosage on quality characteristics. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 55, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stošić, M.; Čučak, D.; Kovačević, S.; Perović, M.; Radonić, J.; Sekulić, M.T.; Miloradov, M.V.; Radnović, D. Meat industry wastewater: Microbiological quality and antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli and Salmonella sp. isolates, case study in Vojvodina, Serbia. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 73, 2509–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Min, M.; Ma, X.; Chandra, C.; Doan, Y.T.; Ma, Y.; Zheng, H.; Cheng, S.; Griffith, R. Growing Chlorella sp. on meat processing wastewater for nutrient removal and biomass production. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 198, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Kuo-Dahab, W.C.; Dolan, S.; Park, C. Kinetics of nutrient removal and expression of extracellular polymeric substances of the microalgae, Chlorella sp. and Micractinium sp., in wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 154, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foladori, P.; Petrini, S.; Nessenzia, M.; Andreottola, G. Enhanced nitrogen removal and energy saving in a microalgal–bacterial consortium treating real municipal wastewater. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 78, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pires, J.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.; Martins, F.; Simões, M. Wastewater treatment to enhance the economic viability of microalgae culture. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 5096–5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Meneses, Y.E.; Stratton, J.; Wang, B. Acclimation of consortium of micro-algae help removal of organic pollutants from meat processing wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 214, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, J.S.; Madsen, E.L. Microbial Ecological Processes: Aerobic/Anaerobic. In Encyclopedia of Ecology; Jørgensen, S.E., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, MS, USA, 2008; pp. 2348–2357. [Google Scholar]

- Kundu, P.; Debsarkar, A.; Mukherjee, S. Treatment of slaughter house wastewater in a sequencing batch reactor: Performance evaluation and biodegradation kinetics. BioMed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 134872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Díez-Montero, R.; Rueda, E.; Cascino, F.C.; Parati, K.; García, J.; Ficara, E. Free ammonia inhibition in microalgae and cyanobacteria grown in wastewaters: Photo-respirometric evaluation and modelling. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 305, 123046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhou, Z.; Hao, S.; Wang, L. Microalgae cultivation using unsterilized cattle farm wastewater filtered through corn stover. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 352, 127081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. Freezing as a combined wastewater sludge pretreatment and conditioning method. Desalination 2011, 268, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collos, Y.; Harrison, P.J. Acclimation and toxicity of high ammonium concentrations to unicellular algae. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 80, 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, A.; Basheer, F.; Sengar, A.; Khan, S.U.; Farooqi, I.H. Biological wastewater treatment (anaerobic-aerobic) technologies for safe discharge of treated slaughterhouse and meat processing wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 686, 681–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, B.-H.; Kang, Z.; Ramanan, R.; Choi, J.-E.; Cho, D.-H.; Oh, H.-M.; Kim, H.-S. Nutrient removal and biofuel production in high rate algal pond using real municipal wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 24, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calijuri, M.L.; Do Couto, E.A.; Assemany, P.P.; Ribeiro, V.J.; Lorentz, J.F.; Castro, J.D.; Assis, L.R.; Oliveira, A.P.S.; Pereira, A.S.A.P.; Marangon, B.B.; et al. Microalgae-Based Wastewater Treatment and Biomass Valorization: Insights, Challenges, and Opportunities from 15 Years of Research. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 49273–49299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira Castro, J.; Assemany, P.P.; de Oliveira Carneiro, A.C.; Ferreira, J.; de Jesus Júnior, M.M.; de Ávila Rodrigues, F.; Calijuri, M.L. Hydrothermal carbonization of microalgae biomass produced in agro-industrial effluent: Products, characterization and applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 768, 144480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.; Mysnyk, Y.; Mahmoud-Aly, M.; Mostafa, E.; Almutairi, A.W.; Abbas, D.G.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Hanelt, D.; Abomohra, A. Valorization of abattoir water discharge through phycoremediation for enhanced biomass and biodiesel production. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 191, 107448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.A.; Castro, J.S.d.; Ribeiro, V.J.; Ribeiro Júnior, J.I.; Tavares, G.P.; Calijuri, M.L. Microalgae biomass as a renewable biostimulant: Meat processing industry effluent treatment, soil health improvement, and plant growth. Environ. Technol. 2023, 44, 1334–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, M.; Yosri, M.; Fawzy, M.E.; Moghazy, R.M.; Elfeky, E.M.; Marouf, M.A.; El-Khateeb, M.A. Microeukaryotic communities diversity with a special emphasis on protozoa taxa in an integrated wastewater treatment system. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, D.-H.; Heo, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, H.-S. Novel biological method for controlling bacterial contaminants using the ciliate Colpoda sp. HSP-001 in open pond algal cultivation. Biomass Bioenergy 2019, 127, 105258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; He, Q.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M.; Hu, Q.; Gong, Y. A new algivorous heterolobosean amoeba, Euplaesiobystra perlucida sp. nov. (Tetramitia, Discoba), isolated from pilot-scale cultures of Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e00817-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhang, H.; Ma, M.; He, Y.; Jia, J.; Hu, Q.; Gong, Y. Critical assessment of protozoa contamination and control measures in mass culture of the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 359, 127460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, L.E.; Velasquez-Orta, S.B.; Romero-Frasca, E.; Leary, P.; Noguez, I.Y.; Ledesma, M.T.O. Non-sterile heterotrophic cultivation of native wastewater yeast and microalgae for integrated municipal wastewater treatment and bioethanol production. Biochem. Eng. J. 2019, 151, 107319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.