Abstract

In recent years, industrial symbiosis (IS) has gained attention as a strategy to enhance circularity and to reduce the environmental impacts of solid waste management through resource reuse and recovery. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is increasingly used to evaluate the environmental performance of such inter-industry collaborations. Given the growing diversity of IS practices and LCA models, this updated review serves as a methodological reference, mapping existing approaches and identifying gaps to guide future research on the systematic assessment of circular strategies. Moreover, it investigates the environmental performance of IS approaches in the field, based on the LCA results of the analyzed case studies. We analyzed 48 peer-reviewed studies to examine how LCA has been applied to model and assess the environmental impacts and benefits of IS in the context of waste management. The literature revealed wide methodological variability, including differences in system boundaries, functional units, and impact categories, affecting comparability and consistency. Case studies confirm that IS can contribute to reducing environmental burdens, particularly with regard to climate change and resource depletion, though challenges remain in modelling the complex inter-organizational exchanges and accessing reliable data. Socio-economic aspects are increasingly considered but remain underrepresented. Future research should focus on methodological improvements, such as greater standardization and the better integration of indirect effects, to strengthen LCA in decision-making and to explore a wider range of scenarios reflecting different stakeholders, analytical perspectives, and the evolution of symbiotic systems over time.

1. Introduction

Industrial symbiosis (IS) is described as the process by which traditionally separate industries engage in collective strategies, through the physical exchange of materials, energy, water, and by-products [1]. IS definition was later expanded to include the sharing of infrastructure, services, knowledge and expertise [2,3], and broader spatial scales [4]. Key IS objectives are to gain competitive advantages through the reduction in energy and resources consumption, and the minimisation of waste through their valorisation; a residue or by-product for one company can serve as a valuable input for another [3,5,6]. A study conducted by Neves et al. [2] reported manufacturing to be the most represented sector in IS case studies, with the types of waste mostly exchanged being organic, plastic, wood, metallic and non-metallic (e.g., demolition waste), ash, sludge, and paper [2]. Among environmental aspects, the reduction in CO2 and in resource consumption were the most considered in IS real case studies [2]. IS is therefore a relevant component within circular economy strategies, and its implementation is generally expected to generate environmental, economic, and social benefits; the evaluation of these benefits has driven the development of methodologies to study IS systems [7,8].

A widely applied methodology for evaluating environmental impacts is the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). LCA is an internationally standardized method used to quantify the environmental impacts of products, services, or systems throughout their entire life cycle, based on the international standards ISO 14040 and 14044 (2006) [9,10,11,12].

LCA is the most commonly reported methodology for studying the environmental impact of IS [3,13,14,15,16]. Mattila et al. [6] recognized the appropriateness of using LCA in giving direct flow analysis a cradle-to-grave perspective, permitting a more precise assessment of environmental impact and a comparison of baseline scenarios. In a following study, Mattila et al. [17] explored the methodological issues encountered when applying LCA to IS studies, identifying its potential in addressing research questions related to the analysis, improvement, expansion of symbiotic systems, design of eco-industrial parks and environmental impacts in a circular economy [17]. Limitations in the use of LCA were identified in the assessment of the influence of IS application, at full scale, on the economic market structure. Martin et al. [18] acknowledged the lack of standardized methods for LCA application with regard to the quantification of environmental impacts for IS. Authors proposed a method to support the quantification of the impacts of an IS network compared to reference scenarios and suggested an approach for allocating credits among entities [18].

LCA is often used in combination with other methodologies in the study of IS systems, such as mass flow analysis (MFA), input–output models, life cycle costing (LCC), discrete event simulations, or system dynamics [3,13,15]. Felicio et al. [9] indicated LCA and MFA as the most used methodologies to measure the magnitude of impacts and flows, respectively, in eco-parks, despite their limits in assisting the decision-making process, since they cannot measure the trends in, and impacts of, the decisions. Aissani et al. [19] conducted a critical review (2008–2018) on the use of LCA in IS studies, focusing on how authors dealt methodologically with the quantification of environmental impacts. A key issue that emerged was the variability of reference scenarios, which some authors addressed through sensitivity analyses or multiple scenario analyses. Authors suggested developing a standardized procedure for the definition of at least two reference scenarios (best- and worst-case), integrating territorial aspects and stakeholders’ input.

Neves et al. [2] discussed drivers and barriers for waste reuse through IS practices in real contexts. Main drivers were the diversity of industries, their geographical proximity, and the facilitation. LCA was the most used method when studying environmental performance, while LCC was the most used for assessing economic aspects; job creation and MFA were commonly applied to study social benefits, and the quantitative potential for industrial symbiosis, respectively. Results evidenced the considerable potential of IS in substituting resources with waste, and in diversifying waste streams and the type of waste involved.

The use of LCA and LCC methodologies was investigated by Kerdalp et al. (2020) [14] over the period 2010–2019. Results identified the process-based LCA as the most applied methodology, while LCC was conducted to assess, e.g., the profitability or economic feasibility of IS implementation. The review identified the need for a single method to put together different perspectives. The need to incorporate cost analysis more systematically into IS studies, and to develop a more structured assessment framework, also emerged from a study by Wardstrom et al. [20]. In a following study, Kerdlap et al. [9] proposed a methodology for the multi-level modelling and analysis of the environmental impacts of waste-to-resource exchanges, based on the LCA approach, tested on an IS network in the food waste valorization sector in Singapore. A review of the methodologies used in IS studies (2015–2020) [20] recognized LCA as the second most used method (after interviews), applied alone or in combination with other methods. LCA was mostly used to study CO2 emissions reduction, chemical pollution, and freshwater use. The most studied outcomes were the environmental, social, and economic benefits. Material, by-products, and waste were the most studied synergy category, followed by distance by the energy synergies category.

Nevertheless, LCA application within IS studies remains relatively limited. For instance, Aissani et al. [19] documented 26 publications addressing LCA in the context of IS across the Web of Science and Scopus databases up to 2018, while Kerdlap et al. [13] identified only 42 case studies of environmental impact assessments of IS (including LCA) in the period 2010–2019. In contrast, Neves et al. [21] reported the whole body of literature on IS, with 584 scientific papers published by 2019. Taken together, these figures suggest that the number of IS publications adopting an LCA approach reaches only 7.2% of the overall body of the IS literature. Therefore, while the LCA, as a well-recognized tool for the environmental assessment of IS initiatives, appears not only logical but increasingly necessary, its potential has so far been only partially exploited and should be further examined. Additionally, studies in the literature address industrial symbiosis across different domains, including the exchange of waste or other materials, energy, processes, and services, which are often studied in combination. However, the benefits and outcomes of IS networks are not easily comparable across these domains. Therefore, this review focuses specifically on solid waste exchanges, which represent key elements of circularity and play a critical role in environmental performance.

The study aims to address the following research question: how has LCA been applied to IS systems involving solid waste, and what do the LCA results reveal about their environmental performance? Thus, the paper systematically reviews the application of LCA in IS systems to (i) investigate the state-of-the-art in the field, prevailing approaches, limitations, and historical trends, (ii) assess methods and techniques in LCA applications, identifying challenges, advancements, gaps, and future research, and (iii) evaluate environmental performance and the benefits of IS systems.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review of published peer-reviewed articles including case studies of applying LCA to assess IS scenarios in solid waste management, with a quantitative analysis of environmental impacts. Both empirical and hypothetical/prospective cases were considered, provided they offered a detailed methodological description and clearly reported results. The review focused on studies in which LCA was the principal analytical method, while other methods were included only if they complemented the LCA analysis.

The selected papers were then reviewed, and critically cross-analyzed to identify common patterns and insights. Additionally, the characteristics of each case study, including whether it was empirical, hypothetical, or prospective, were systematically classified, providing a clear overview of the types of research included and ensuring methodological rigour and transparency.

2.1. Selection of Case Studies

As the first step, we conducted a search in the Scopus and Web of Science databases, applying the following inclusion criteria: (i) journal articles published in English; (ii) papers indexed up to June 2025; and (iii) papers containing in their title, keywords, or abstract the following combinations of keywords:

Search Protocol 1:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (INDUSTRIAL SYMBIOSIS) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (life cycle assessment lca)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “re”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”))

Search Protocol 2:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (“INDUSTRIAL SYMBIOSIS”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“LIFE CYCLE ASSESSMENT”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “AR”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “RE”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “ENGLISH”))

Search Protocol 3:

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (“INDUSTRIAL SYMBIOSIS”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (LCA)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “AR”) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “RE”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “ENGLISH”))

Web of Science (WoS) Protocol:

(TI = (“industrial symbiosis”) OR AB = (“industrial symbiosis”) OR AK = (“industrial symbiosis”)) AND (TI = (“life cycle assessment”) OR AB = (“life cycle assessment”) OR AK = (“life cycle assessment”) OR TI = (LCA) OR AB = (LCA) OR AK = (LCA)) and Article or Review Article (Document Types) and English (Languages)

The resulting papers were screened for duplicates. The abstracts of the remaining papers were then analyzed to verify the application of the LCA methodology in assessing industrial symbiosis case studies.

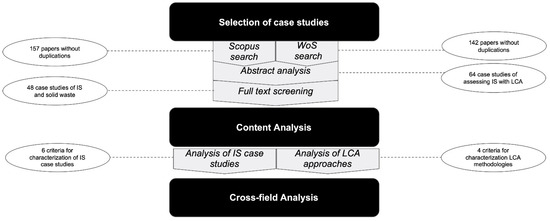

Finally, we screened the full text of the selected papers to verify their relevance to solid waste management case studies. Specifically, we included papers in which one or more solid materials indicated as waste were involved in industrial symbiosis exchanges. Consequently, exchanges involving liquid waste or gaseous waste, or energy or heat deriving from waste, were not considered. Moreover, we relied on the authors’ explicit designation of a material as a waste, since the classification of a solid material as waste depends on its characteristics as well as on local and national regulatory frameworks, which may vary across countries. Figure 1 summarizes the methodological approach of the paper which is structured in three steps: the selection of case studies, content analysis, and cross-field analysis.

Figure 1.

Flow chart describing the literature review methodological approach.

2.2. Content Analysis

Content analysis was performed using a checklist of criteria for assessing the IS case studies and LCA approaches.

The criteria for analyzing the IS case studies were defined through a review of previous studies and frameworks commonly adopted in the IS literature [1,2,3]. These sources helped identify recurrent dimensions, such as type of exchanges, actors involved, scale of the network, and exchanged resources. The final set of criteria was refined to ensure comparability across cases and relevance to the research objectives, and is as follows:

- Geographical scope;

- Background of IS cases;

- Scale of IS;

- Sectors involved (industrial diversity);

- Type of symbiotic exchanges;

- Type of solid materials exchanged.

The LCA approaches were analyzed according to the following criteria, and grouped according to the four phases of the LCA framework, according to ISO 14040:

- Goal and Scope: focus, functional unit, definition of system boundaries, LCA approaches, and use of other sustainability assessment methods;

- Life Cycle Inventory Analysis: LC inventory;

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment: impact assessment methods and categories, assessment of multiple scenarios;

- Interpretation: quality of output data (results details and classification of levels), sensitivity analysis, uncertainty analysis, interpretation of results, and recommendations.

The detailed description of each above-mentioned criterium is reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Data were organized and analyzed with Microsoft Excel, version 2510 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

2.3. Cross-Field Analysis

Following the content analysis, a cross-field analysis was conducted to evaluate and compare the results across the defined criteria. This process enabled the identification of patterns, trends, and inconsistencies within the dataset. By synthesizing the findings, the final results and conclusions were drawn about the overall sample, providing a comprehensive understanding of the subject under review.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Characteristics of the Selected Literature Corpus

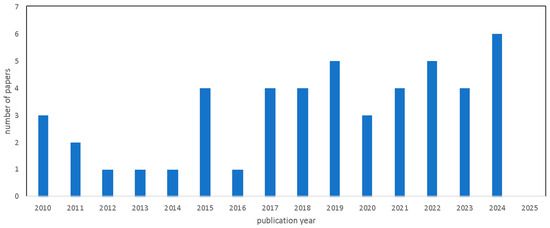

The first step of the search for studies using keywords resulted in 157 papers without duplicates. Abstract assessments reduced this to 64 papers. The full-text screening resulted in the identification of 48 papers. The list of selected papers, describing LCA use within IS exchanges involving solid waste, is provided in Table 1. The selected papers were published between 2010 and 2024 (Figure 2), with the maximum number identified in 2024 (six papers). Publications were found in 25 journals; those with >three selected papers are as follows: Journal of Cleaner Production (11), International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment (4), Journal of Industrial Ecology (4), and Resources, Conservation and Recycling (4).

Table 1.

List of the selected papers for the literature review (n. = number; Ref. = reference).

Figure 2.

Temporal distribution of the 48 papers selected for the review in Scopus.

3.2. Characterization of IS Cases

3.2.1. Geographical Scope

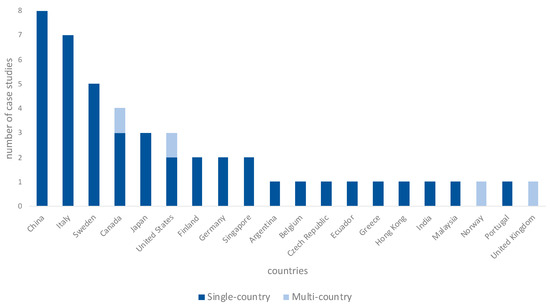

Half of the case studies were located in Europe, 33% in Asia, and 13% in North America. Seven papers did not focus on areas located in a single country but rather examined broader contexts, three studies addressed general conditions in the EU [47,55,57], and two studies analyzed multi-country cases in Europe [59] and North America [44], respectively (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Geographical distribution of analyzed case studies (Note: the chart does not cover three case studies considering general condition in the EU).

3.2.2. Background of IS Cases

Among the analyzed papers, 23 papers (46%) examined existing IS case studies and 25 (54%) addressed hypothetical or prospective IS scenarios. Both categories constituted substantial portions of the literature, underscoring the attention devoted to both implemented and anticipated IS initiatives. Until 2015, the number of papers examining existing IS case studies exceeded those examining hypothetical or prospective IS scenarios, reflecting a primary focus on documenting already implemented initiatives. From 2016 onward, this pattern reversed, with studies on future IS cases consistently outnumbering those on existing cases, indicating a growing research interest in prospective IS development and the exploration of its potential benefits over longer time horizons.

3.2.3. Scale of IS

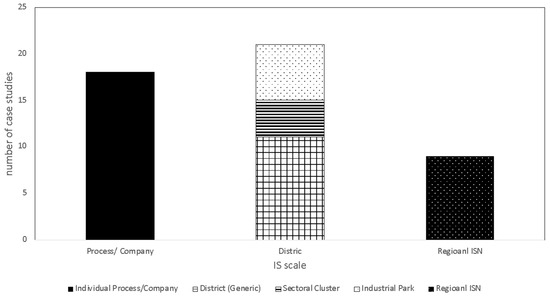

The scale of IS refers to the hierarchical position of a case study within the broader concept of the industrial ecosystem. IS initiatives may range from measures undertaken by a single company or for a single process, to the establishment of clusters or parks of co-located industries [67], to, ultimately, the development of larger networks operating at regional or national levels [68]. The scale can be formally defined, for example, in the case of clusters established and managed by dedicated governance bodies, or it can be defined by the authors of the study when selecting the system boundaries or objective. In this study, the scale criterion could assume the following attributes: company, district, and regional industrial symbiosis networks (ISN) (for further detail see Section S1—Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4 illustrates the number of case studies formally defined for each scale of IS: processes/company (18 papers), district (21 papers), and regional ISNs (9 papers).

Figure 4.

Number of papers categorized accordingly to the scale of the case studies described.

At the process/company scale, most papers focused on a specific real-world case to identify potential critical points to apply IS solutions to (e.g., [53]), while others examined a hypothetical case, intended to investigate concerns common to a specific sector and/or to a given area (e.g., [63]).

At the district level, case studies encompassed a variety of industrial districts. These included historically well-recognized industrial clusters in Italy [10], which were typically mono-sectoral agglomerations of small and medium enterprises (SMEs), as well as eco-industrial parks in China [66], eco-towns in Japan [39], and industrial ecosystems in Finland [58]. Some studies explored the interaction between industrial districts and municipal solid waste management systems, forming examples of urban industrial symbiosis (UIS) [34].

At the regional scale, nine case studies investigated broader IS interactions, addressing issues such as the critical distance between exchanges that remains environmentally beneficial [47]. This scale typically involves the assessment of the capacity of an entire region to recover waste as an alternative input for industrial processes. Such studies often target decision-makers and public authorities rather than individual companies, and they usually involve a wider range of stakeholders (e.g., [30,56]). One study examined the interactions with urban solid waste management systems [27].

When case studies are examined according to system boundaries assigned by the authors, the distribution across the three attributes varies. According to this classification, 23 papers fall in the company/process scale category, 18 in the district one, and 7 under the regional scale (Figure S1—Supplementary Materials). In some papers, authors focused on a single company within a district or regional network (e.g., [10]), meaning that the company/process category is larger, if assessed according to a boundary-based classification.

3.2.4. Sectors Involved (Industrial Diversity)

Industrial diversity is recognized as a contextual factor that facilitates the implementation of industrial symbiosis (IS) [67,69], while also contributing to its stability and potential scalability. Out of 48 total cases, 6 were mono-sectoral. Mono-sectoral IS can encompass different situations; for example, exchanges among multiple actors operating in the same sector (e.g., plastic valorization of various waste fractions [25]), or cases in which a single entity applies LCA to assess its own potential for improvement through IS participation [26,53] can be considered mono-sectoral. A total of 21 studies involved exchanges among companies belonging to two or three sectors, while 17 cases involved that among companies belonging to five to ten sectors, reflecting higher levels of diversity (see Figure S2 in the Supplementary Materials for a detailed analysis).

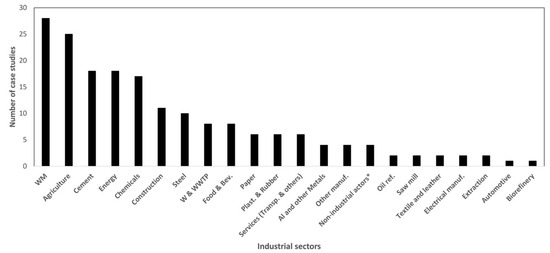

Figure 5 illustrates the frequency of sectoral involvement across all case studies. In total, 22 different sectors were identified, with waste management, agriculture, cement, energy, chemicals, construction, and the steel industry being the most frequently represented. Notably, 28 out of 48 case studies included at least one waste management company as part of the IS exchanges. In some studies, non-industrial actors were involved, such as residential areas that benefited from the heat produced as a result of IS interactions.

Figure 5.

Diversity of IS partners in the analyzed case studies. Non-industrial actors, indicated with an asterisk (*), correspond to residential areas involved in IS scenarios, despite not engaging in industrial activity.

3.2.5. Type of Symbiotic Exchanges

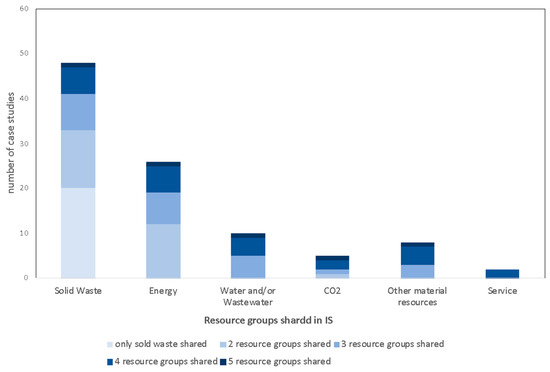

Figure 6 illustrates the types of resources exchanged in the analyzed IS cases, highlighting the frequency of different resource groups shared either individually or simultaneously. While 20 out of 48 cases focused exclusively on solid waste exchanges, the others involved multiple exchanges ranging from two to five different types of flows (e.g., [66]). Other exchanges included energy (e.g., [34,55]), water (e.g., [49,56]), CO2 emissions (e.g., [23]), liquid materials (e.g., [10]), and even non-material or service-based exchanges (e.g., [14,51]). Among the non-solid resources, energy exchanges were the most common, including waste heat recovery and the use of alternative fuels derived from liquid or solid waste. By contrast, service-based exchanges were rare, with a few cases reported. These included shared transportation services for people and goods, aimed at reducing both emissions and transportation costs for IS partners.

Figure 6.

Exchanged resources in analyzed IS case studies.

3.2.6. Type of Solid Material Exchanged

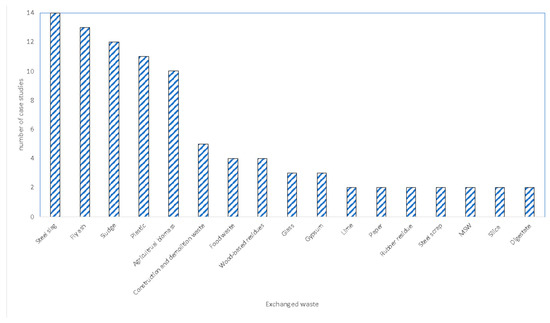

Figure 7 presents the most frequently exchanged solid material flows. Biomass and organic waste [36,43], fly ash [62], sludge [35], and steel slag [63] emerged as the most common solid resources valorised through IS practices.

Figure 7.

Exchanged solid waste flows in analyzed IS case studies.

The number of distinct solid waste flows exchanged ranged from one to eight per case study (see Figure S3 in the Supplementary Materials for a detailed analysis). Out of the 48 cases, 24 involved exchanges of a single type of solid waste, 14 involved two or three, and 10 involved four to eight.

3.3. Characterization of LCA Methodologies

This section reports the results of the assessment of methodological aspects of LCA application in IS.

3.3.1. Goal and Scope

Focus

The reviewed LCA studies on industrial symbiosis encompass a range of scopes, namely product-based, waste-based, network-based, and service-based (see Figure S4 in the Supplementary Materials for a detailed analysis). In 31% of the papers, LCA is used to evaluate the impacts of entire systems that include multiple production processes (network-based group) (e.g., [14,43]). A total of 37% of the case studies focused on a single product system, typically assessing products manufactured with alternative inputs in comparison to conventional product-based options (e.g., [37,63]). A total of 15% of the studies adopted a waste-based approach, concentrating on the treatment and recovery of waste streams in new production pathways, thereby avoiding their disposal, primarily in landfills [e.g., 42]. One single paper adopted a service-based approach, focusing on the study of a waste-derived product used as a service for its entire lifetime [46]. This case can represent an interesting example for future LCA applications given the importance of the “product as service” concept in the circular economy discourse [70]. In 15% of the case studies, the scope of the study was not clearly defined.

The scale of the IS case study (see Section 3.2.3) influences the focus of the LCA. At the company or process level, most case studies address the valorization of specific solid waste streams within a single process or company. In nearly half of these cases (8 out of 18), the valorized waste originated from a waste management company. In the remaining cases, firms valorized their own waste internally, using outputs from one department or process as inputs to another (e.g., [5]). At the district level, the system boundaries expand to include multiple entities that benefit from geographical proximity. In 16 of these cases, waste management actors played an active role not only as providers of logistics services but also as partners in innovative recycling initiatives extending beyond traditional industrial boundaries (e.g., [33]). At the regional level, in five case studies, waste management actors served as network initiators, connecting local IS networks with broader waste collection systems (e.g., [27,38,44]).

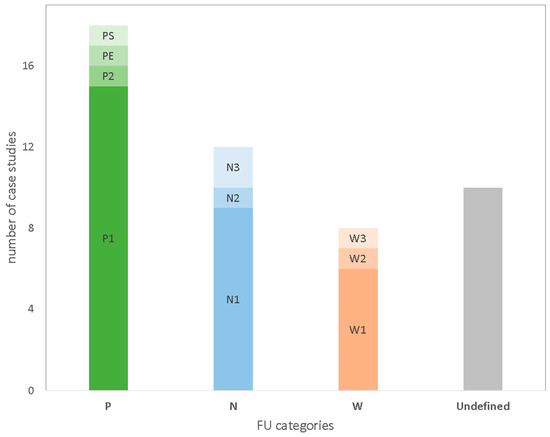

Functional Unit (FU)

The reviewed papers followed three main approaches depending on their scope (product-based, network-based, or waste-based). In product-based focused studies, the FU was commonly defined as the mass unit of the final product at the factory gate (P1 in Figure 8) (e.g., [29]). In one case, it was defined as the mass of a specific component within the reference product, rather than the product itself (P2 in Figure 8) [59]; in another study, FU was the energy unit of the supplied steam (PE in Figure 8) [46]. Finally, in one case, the FU was defined by the lifetime service provided by a product containing recycled material (PS in Figure 8) [31].

Figure 8.

Categories of the FUs defined in the analyzed case studies (P: product-based; N: network-based; and W: waste-based. For the definition of sub-categories please refer to the main paragraph).

In network-based focused papers, the FU was defined with respect to the overall system, an approach also recommended by Martin et al. [18] and Mattila et al. [17]. Most frequently (nine papers), the FU was defined as the total output of the system, i.e., the network’s multi-product production (N1 in Figure 8) (e.g., [58]). In one study, the FU was represented by the total energy generation of the network (N2 in Figure 8) [48]; in two case studies, the FU was defined as the network’s annual production of main reference products (N3 in Figure 8) [25,49].

In eight waste-based focused papers, the FU was defined as the mass unit of treated reference waste flows (W1 in Figure 8) in six cases (e.g., [36]); in one paper as the mass unit of recovered material from the reference waste (W2 in Figure 8) [42]; and in another paper as the total annual waste generated by the system under study (W3 in Figure 8) [22].

Finally, in ten of the reviewed papers, the FU was not explicitly defined.

The differences in functional units are related to the scale of the IS exchanges discussed in Section 3.2.3 (see Figure S5, Supplementary Materials). At the company level, FUs were predominantly product-based, with 14 out of 18 cases employing either P1 or P2. At the district level, two distinct trends were identified. In mono-sectoral clusters, the FUs applied were similar to those at the company level, with P1 used in two out of four cases. Conversely, in generic districts and industrial parks, ten out of seventeen studies adopted network-based FUs (N1, N2, and N3). In addition, FUs based on exchanged energy and services (Pe and PS) appeared exclusively at the district level, indicating the greater potential for capturing the benefits of energy and service valorization among co-located companies—an opportunity that is less feasible at the single-company scale or in long-distance exchanges at the regional level. Finally, at the regional level, a higher degree of inconsistency in FU definitions was observed: half of the analyzed case studies (four out of nine) did not clearly define an FU, while the remaining ones mainly used waste-based (W1) or network-based (N1 and N3) FUs. This suggests that regional studies tend to focus on evaluating the effects of IS initiatives on regional waste management performance.

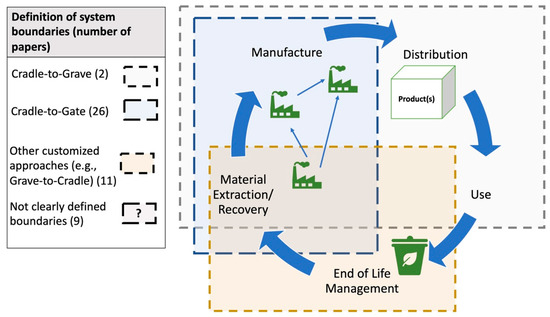

Definition of System Boundaries

Out of the 48 analyzed case studies, 26 followed a Cradle-to-Gate approach, encompassing raw material extraction and production while excluding the use and end-of-life phases (Figure 9). Of these, 16 studies adopted a standard Cradle-to-Gate perspective, while 9 included specific refinements, such as lab-scale considerations and the inclusion of produced waste management or transport; these specifications are generally considered consistent with the Cradle-to-Gate principle (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

System boundaries defined in the analyzed IS case studies.

Eleven studies defined customized or unconventional system boundaries, ranging from “recovered material to co-combustion” [46] to “upstream, onsite, downstream” approaches [33], reflecting different interpretations of system scope.

Two studies explicitly adopted a Cradle-to-Grave approach [47,66].

Finally, 9 studies did not clearly define their system boundaries, providing ambiguous descriptions or relying only on figures illustrating material flows.

The reference to ISO 14040/14044 standards for LCA, relevant to boundary selection, was inconsistent: 25 studies referenced ISO standards, while 23 did not, including 7 of the 9 cases with unclear boundaries, suggesting a link between the absence of ISO citations and the lack of clear system boundary definition.

Regarding allocation methods, 15 studies explicitly applied system expansion, 7 of which also reported allocation approaches, mostly using a 50/50 split, which can still be interpreted as consistent with system expansion, while 2 applied economic allocation. Among the studies not using system expansion, 11 explicitly stated allocation methods, including economic [26], mass-based [57], hybrid [53], or first-use allocations [31], whereas the remaining studies did not specify a method.

These results indicate that, despite the prevalence of Cradle-to-Gate applications, a considerable variability remains in boundary definitions and allocation practices, highlighting the need for standardized reporting to enhance comparability and robustness in LCA studies of IS.

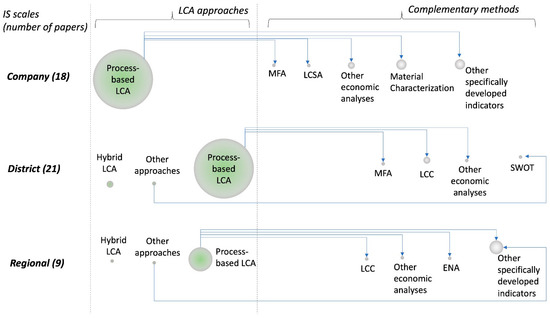

LCA Approaches and Use of Other Assessment Methods

Regarding the methods used for the environmental assessment, 43 papers applied the conventional process-based LCA approach. Three case studies combined process-based LCA with Environmentally Extended Input–Output Analysis, thereby adopting a hybrid LCA approach [33,34,62]. Furthermore, in two cases, LCI data were used as the input for innovative assessment methods aimed at evaluating the potential for resource recovery from waste and the reduction in emissions and disposal. These approaches were employed mainly as tools to support decision-making in macro-level studies and to inform broader groups of stakeholders, rather than to conduct a standard LCA [30,56]. Beyond LCA, two case studies also applied MFA (e.g., [63]) and one case study applied Ecological Network Analysis (ENA) [27] as complementary environmental assessment methods.

In addition to environmental assessments, 19 studies conducted additional assessments about social and/or economic aspects, using the following methods: Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), integrating environmental, economic, and social dimensions (one study, [57]); LCC (three studies, e.g., [38,43]); other economic analyses (six studies, e.g., [61]); SWOT analysis (one study [56]); and seven studies used specifically developed indicators.

Moreover, three case studies incorporated results from material characterization and laboratory analyses of alternative resources recovered from waste and products manufactured from these recovered components [41,60,63]. Figure 10 summarizes how the complementary methods are related to various LCA approaches in each IS scales (Section 3.2.3).

Figure 10.

Relations among IS scales, LCA approaches, and complementary methods used in the analyzed case studies.

3.3.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

Life Cycle Inventory

A total of 39 case studies clearly mentioned using an LCI standard approach; of these, 32 collected both primary and secondary data relevant to their LCA, while 7 used secondary data only.

Primary data were collected from laboratory experiments or from industrial facilities. Data collection methods included onsite measurements, structured questionnaires, flow mapping, site visits, interviews with companies and stakeholders, and, in some cases, aggregated averages across samples of companies.

Among secondary data sources, the literature was mentioned in 30 cases; commercial data inventories (e.g., Ecoinvent) were consulted in 34 case studies, especially for background processes. Finally, 22 papers included either the full dataset or aggregated data of their inventories as Supplementary Materials.

3.3.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment

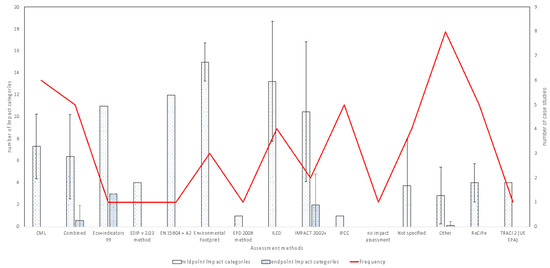

Impact Assessment Methods and Impact Categories

The reviewed studies show a considerable degree of heterogeneity in the impact assessment methods applied. Figure 11 shows the frequency of impact assessment methods applied with the average number of midpoint and endpoint categories used by each of the methods in the analyzed IS case studies. Among the most frequently used methods, CML was applied in six cases, while ReCiPe- and IPCC-based approaches were used in five cases each. Hybrid or combined approaches were reported in five studies. Other methods included the International Life Cycle Data system method (and the Environmental Footprint method). Less frequently adopted approaches comprised the IMPACT 2002+, Eco-indicator 99, EDIP v2.03, EN 15,804 + A2, Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) 2008 method, and TRACI 2 (US EPA) methods.

Figure 11.

Frequency of impact assessment methods with the number of midpoint and endpoint categories applied in the analyzed IS case studies. Bar height represents the average number of impact categories assessed by each method and the error bars show the standard deviation from the calculated averages.

In most studies, the analysis focused exclusively on midpoint impact categories, while only three cases extended the assessment to endpoint categories. For each method, not all possible midpoint categories were consistently assessed or reported in the published studies. In Figure 7, the error bars show the standard deviation from the average number of categories assessed under each method.

In 25 case studies, only one to four midpoint categories were considered. Among these, the most frequently included categories were as follows: climate change, acidification, eutrophication, and energy demand/resource use.

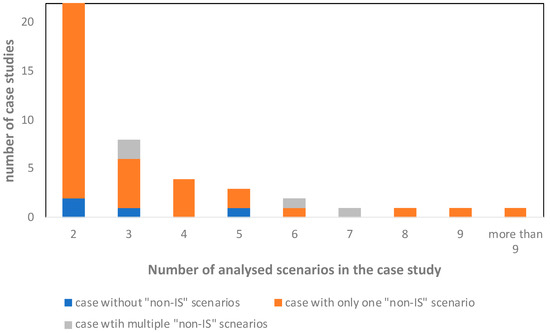

Assessment of Multiple Scenarios

Scenarios were used to compare IS options against one or more counterfactual systems. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the scenario analyses used in LCA studies for the evaluation of IS cases, based on three aspects: purposes, numbers, and reference (baseline) systems.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the scenarios used in LCAs of IS case studies.

Almost every study constructed some form of reference scenario, which serves as the baseline against which IS strategies were assessed. However, the definition of this reference system varies considerably. In some cases, it was anchored to current conventional practices, such as landfilling or incineration [36,57], while in others it was a hypothetical non-IS system, where no exchanges existed between firms to test the net benefits of symbiosis [25,35,61]. A further group used standalone or traditional production systems (e.g., cement, concrete, or product-specific chains) as the benchmark [22,58].

Beyond the baseline, studies also differed in the number and type of scenarios used (Figure 12). The simplest designs compared two scenarios, the IS and the reference one, e.g., [25,60], in a structure that provided clarity but little room for exploring variation or uncertainty. Other studies developed extensive scenario sets, up to >five (e.g., [41] with eight scenarios; [34] with six scenarios; [51] with nine scenarios; [63] with thirty-five combinations of technologies). These richer frameworks often capture different degrees of IS intensity [34,65] or explore alternative technological or managerial pathways [55,63].

Figure 12.

Number of analyzed scenarios divided by the number of “non-IS” scenarios in the case studies.

With regard to the purpose of scenario differentiation, in most cases, the comparison is structural, contrasting an IS network with a non-IS system. In other cases, the design of scenarios introduces incremental improvements, distinguishing among current IS practices and more ambitious or optimized configurations, e.g., [49,51]. A different approach is that of methodological variation, where scenarios test alternative allocation rules (e.g., [14], with mass vs. economic allocation), displacement assumptions [26], or transport distances [47]. In two studies, the comparison was centred on product substitution, where a circular or symbiotic product is assessed against its conventional counterpart [52,59]. A smaller set of studies explicitly embedded sensitivity analyses into their scenario framework [28,62], extending the robustness of the conclusions. These did not only ask “what if” symbiosis is applied, but also “what if assumptions about system boundaries or methodological choices change.”

In summary, scenario construction in IS research serves multiple roles: it can provide a simple counterfactual test of benefits, a framework for exploring alternative futures, or a sensitivity instrument to probe methodological robustness. While the baseline vs. IS dichotomy is the dominant pattern, the range of practices showed that scenario analysis is not standardized but rather adapted flexibly to the context, scale, and purpose of each study. A total of 31 papers indicate the use of a software tool in the LCA (i.e., SimaPro, GaBi, OpenLCA, etc.).

3.3.4. Interpretation

Results Details and Classification of Levels

A recurrent concern in previous reviews of LCA studies on IS was the need to report not only the overall results, but also to assess its contribution to impacts at the following different levels: entities (partner companies) [14], life cycle stages, processes, or flows, as is generally common in the documentation of LCA for studies at the company/process scale (not necessarily having IS). Without such disaggregated reporting, the identification of hotspots and the provision of actionable insights for decision-makers remain insufficient.

Among the case studies analyzed in this review, in 15, no sub-level results were presented, while in the remaining 33, contributions were reported at one or two scales. Among these, most studies presented results at a single scale: according to entities, life cycle stages, production process compartments, flows, and flows limited to exchanged ones. Additionally, eight of these studies also reported the contribution of avoided processes. Studies providing results across two scales of sub-levels included sectors, entities, life cycle stages, process compartments, and flows; in two of these, the impacts of avoided processes were also presented.

The transparency of data presentation was equally uneven. The majority of studies reported results in one or two tables, typically at an aggregated level with subdivisions, such as life cycle stages or flows, primarily to support a comparison between IS and non-IS scenarios. About one third of studies did not provide any numerical data tables, presenting impact assessment results only in graphical form. Only six studies provided comprehensive reporting through multiple tables covering different levels, sub-levels, and scenarios [26,49,51,55,57,61]. These findings highlight a substantial gap in the quality and granularity of reporting, suggesting that future LCA studies on IS should place greater emphasis on sub-level analysis and transparent numerical data presentation to maximize their interpretability and usefulness for stakeholders.

Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

Sensitivity and uncertainty analyses are critical, as recommended by ISO standard 14044/2006, for ensuring the validity of LCAs, particularly in complex systems such as IS, where outcomes may be influenced by diverse material flows and context-dependent conditions [71]. A total of 38% of assessed studies addressed sensitivity by testing the impact of various factors on the final results.

Sensitivity analysis most frequently examined the changes in input flows (e.g., electricity mix), transport distances, production process configurations, output contexts such as market-related factors, and the variations in LCA methodological assumptions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main categories sensitivity assessment of the LCA results for the IS case studies.

No analyses of uncertainty issues were performed for most of the case studies. In four papers, uncertainty was addressed partially, within the sensitivity analysis. Finally, four papers applied Monte Carlo analysis for uncertainty analysis, as a suggested method in many conventional LCA guidelines [31,44,45,55].

Interpretation of IS Results and Recommendations

The examined LCA case studies illustrated the potential of IS to reduce environmental impacts, while highlighting context-specific trade-offs and methodological sensitivities.

Quantitative assessments across the reviewed cases reveal substantial variability in the environmental contributions of IS initiatives. Some cases report large relative improvements, such as reductions in CO2 emissions of 45% per tonne of cement through the use of industrial by-products [23], reductions in water depletion by 46% within network-level IS scenarios [14], and impact reductions of up to 96% in alternative agricultural symbiosis scenarios compared to Business As Usual (BAU) [24].

The results show that IS, under certain conditions, can be an effective strategy in decarbonization and energy transition pathways. For instance, the reuse of automotive scrap in building envelopes avoided millions of kilograms of CO2-equivalent emissions [22], while steelmaking symbioses demonstrate large potential benefits if the slags and energy by-products could be reused in other processes [37,53]. Also, bioeconomy-based networks frequently outperformed fossil-based systems, mitigating environmental impacts by 25–130% [40]. Another example, from China, showed that the comprehensive utilization of red mud and other exchanged materials collectively saved millions of tonnes of CO2 and substantial primary energy [64]. It was demonstrated that even in mature IS networks, such as Kawasaki Eco-town, further improvements in greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction and resource conservation are possible, highlighting the potential for continuous optimization [39].

Other studies indicate moderate but meaningful gains, such as carbon emission efficiency improvements of 13–15% in multi-industry networks [25,33], or reductions in GHGs, energy, and eutrophication in the range of 10–50%, depending on the symbiotic pathway [45,65]. Conversely, some initiatives yield modest or marginal contributions, where overall reductions were below 5% at the network level [43], or where environmental gains were largely offset by upstream impacts such as energy-intensive recycling or transportation [28,31,58]. The scale of IS exchanges (see Section 3.2.3) may influence the environmental benefits achieved. It was observed that most case studies reporting relatively smaller environmental contributions from IS (five out of eight) were conducted at the district level. This suggests that assessments focused primarily on individual entities may need to be complemented by analyses addressing system-level allocations and categorical assumptions to better capture the overall environmental performance.

Importantly, many cases highlighted that the magnitude of the contribution is highly dependent on specific conditions; the electricity mix, the transport distances, choice of allocation method, scale of implementation, and local resource availability can all increase or decrease the realized benefits [42,47,54]. For example, in one of the cases [28], it was highlighted that recovered co-products, such as glass, plastics, and metals, contribute more to environmental gains than simple landfill avoidance, which may be negated by longer transport distances.

Other cases reported reductions in climate change impacts, water depletion, and energy use, while also highlighting factors that may influence the results, such as methodological choices or system conditions, both positively and negatively [5,10,14,23,32,38,43,48]; for example, it was shown that network-level results were robust across mass versus economic allocation [14], yet entity-level impacts were sensitive to these choices. Similarly, regarding the methodological assumptions, it was observed that partial allocation makes by-product exchanges more equitable and attractive, whereas full allocation may disincentive cooperation [25]. Consequential LCA approaches revealed the sensitivity of results to regional market dynamics and supply–demand interactions [44]. Expanding system boundaries often uncovered additional synergies or previously overlooked impacts, as highlighted in built environment analyses [60]. Electricity mix assumptions were another major determinant, as shown in PV module case studies in Greece versus in Germany [42].

These observations reinforce that while IS can generate significant sustainability improvements, the effectiveness of each initiative must be evaluated with regard to its particular operational and regional context to ensure meaningful environmental contributions.

At the same time, it is also important to consider sector-specific conditions that affect the environmental performance of companies in each sector. In agriculture- and food-related symbioses, the performance is often shaped by regional supply chains and the functional equivalence of products. For example, Ansanelli et al. [24] demonstrated that replacing synthetic fertilizers with coffee compost significantly reduced environmental impacts and disposal costs, but resource use and electricity consumption accounted for the major environmental burdens. Viana et al. [54] showed that oat residue valorisation produced environmental benefits, yet these were strongly dependent on local electricity mixes and assumptions about avoided products. Strazza et al. [59] found that while aquaculture feed derived from food waste outperforms conventional feed, the supply chain bottlenecks influencing the benefits vary across multiple impact categories, and results also differ depending on the geographical context. In other words, the same exchanges can be beneficial or detrimental, depending on local conditions and reference systems.

While this review focused on the treatment of solid waste, it was observed that the theme of energy symbioses, in combination with material exchange, whether through fuel substitution, waste heat recovery, or renewable integration, represented a central topic dealt with in case studies, both as an opportunity and as a threat affecting the successfulness of IS activities. For example, the co-combustion of municipal sludge with coal reduced global warming potential but increased acidification and toxicity, in one case [46], while steam sharing between cogeneration plants and refineries yielded substantial environmental savings, contributing 25% of the industrial GHG reduction targets in the respective region, in another case [35]. These examples underscore the importance of assessing multiple impact categories simultaneously, as a single-metric focus may overlook critical trade-offs.

The construction sector also illustrates the potential of IS. Industrial by-products such as fly ash, slags, pulp residues, and glass powder have been successfully valorised in concrete, bricks, and pavements [31,57,62]. Net environmental benefits were often substantial, yet sensitive to transportation distances and regional material availability. For example, in one of the case studies [31], the environmental advantage of using glass powder as a supplementary cementitious material could be reversed if the base material transport distances were high. Conversely, long-distance exchanges could still be justified environmentally if heavy-duty transport efficiency and material substitution benefits were sufficient [47].

Socio-economic dimensions further reinforce the value of IS. Several cases reported cost savings alongside environmental gains [24,38,45], while others emphasized job creation, skills development, and regional identity [50]. Urban-scale analyses confirmed that IS can relieve pressure on public infrastructure, such as landfills and water systems [30], and contribute substantially to regional GHG targets [35]. However, it should be noted that the gains of IS in environmental and social aspects do not always progress in parallel. For example, in one of the case studies [27], the value of structural network metrics was highlighted, showing that regional IS networks may have only minor effects on environmental indicators but can significantly influence other aspects of sustainability and regional planning decisions.

Persistent limitations and research gaps remain in environmental impact assessments of IS. Market acceptance of non-traditional materials, such as incinerator fly ash bricks, affects whether environmentally optimal solutions are implementable [62]. Toxicity assessments are still challenging within conventional LCA and often require site-specific data [53]. These constraints underline the need for holistic, multi-dimensional approaches combining environmental, economic, and social indicators, with attention paid to local context and governance structures.

Overall, the analyzed case studies confirm that IS can deliver significant reductions in GHG emissions, resource use, and waste generation, while generating economic and social co-benefits. Nevertheless, the benefits are context-specific, dependent on electricity mix, transport distances, allocation methods, and market conditions. Trade-offs in secondary impact categories remind us that IS should be approached systemically, rather than focusing narrowly on carbon or single metrics. Future research should pursue dynamic, consequential, and multi-scalar LCA approaches, paired with policy frameworks that facilitate fair benefit distribution, encourage local material uptake, and integrate circular economy principles. When implemented carefully, IS emerges as a robust pathway for sustainable industrial transformation.

3.4. Limitation of the Study

The limitation faced in this study is that the academic literature is only part of LCA documentation. LCA has become central to many certification and reporting practices in industry, particularly through the use of EPDs [72,73]. While these are typically product-focused and may fall outside the traditional scope of IS, they contain valuable environmental data that could inform IS evaluations. Future studies should explore methods to extract IS-relevant insights from EPD databases, using tailored search protocols and analytical frameworks. Data for this review were collected from two databases, Scopus and Web of Science, and only English-language documents were considered.

3.5. Future Directions

The future direction for this study will entail the development of a comprehensive framework for scenario analysis. Earlier works generally suggested that analyses of IS should focus on comparing IS and non-IS scenarios. However, the reviewed studies indicate that practical requirements and the diversity of stakeholders extend beyond such a binary perspective. Taken together, the body of work shows both commonalities and divergences. The common thread is still the baseline vs. IS comparison, which remains the methodological core of scenario analysis in IS research. Yet, the way this is operationalized differs; some studies adopt minimalist binary contrasts, while others construct complex scenario landscapes to reflect technological diversity, future pathways, or methodological uncertainties. The choice appears to depend on the maturity of the IS system under study (existing networks vs. hypothetical designs), the complexity of the industrial processes involved, and the analytical ambition of the research.

Since 2016, the number of studies exploring hypothetical or prospective IS cases, i.e., initiatives in contexts where IS has not yet been implemented, has increased. This trend may reflect an emerging research direction that deserves further investigation, both for IS studies, in general, and for LCA-focused analyses. Moreover, the distinction between existing and prospective IS cases already introduces different challenges; in the first challenge, the main issue is whether it is meaningful to contrast actual flows with a hypothetical non-IS situation, while in the second, the difficulty lies in defining the expected level of implementation, market interactions, and other uncertainties. Our analysis of more recent case studies shows that this dichotomy is no longer sufficient. Increasingly, studies assess existing IS systems against improved, optimized, or scaled-up configurations, capturing the potential for enhancement even where symbiosis is already implemented. Future LCA applications in this field will, therefore, need to move beyond the simple IS versus non-IS comparison, exploring a wider range of scenarios that reflect different stakeholders, analytical perspectives, and the evolution of current IS systems over time.

4. Conclusions

This review provides a quantitative mapping of LCA case studies in the field of IS, classifying environmental performance against key methodological and IS characteristics. This mapping highlights existing gaps and provides a methodological reference to enhance consistency and comparability in future IS assessments. This study contributes to the literature on the LCA of IS approaches involving solid waste treatment, by reviewing 48 case studies, published between 2010 and 2024. The analysis considered both IS characteristics, and LCA methodologies and results. While this dual perspective has been rarely adopted in previous LCA reviews, our findings show that the benefits expected from IS are influenced not only by methodological assumptions but also by the implementation context.

In terms of IS characteristics, the case studies revealed a diversity of scales, ranging from individual industries (18 cases) to districts (21 cases) and regional networks (9 cases), highlighting the broad spectrum of interests in implementing IS and assessing its performance. Several industrial sectors were involved, with 31 cases including one to four sectors and 21 cases involving more than four sectors, with waste management, agriculture, cement, energy, and chemicals being the most represented. A total of 28 cases also included exchanges of other resources, such as energy, water, or CO2, alongside solid waste. Regarding the types of solid waste exchanged, 24 cases involved a single type, 14 involved two or three types, and 10 cases involved between four and eight types. Fly ash, slags, sludge, plastic waste, and agricultural biomass were represented far more frequently than other waste flows in the exchanges.

With respect to LCA methodologies, 20% of the studies lacked a clear and systematic approach, disregarding ISO 14040 standards and their methodological requirements, and often neglecting sensitivity and uncertainty analysis.

The reviewed LCA studies revealed a substantial variation in scope, with three main approaches identified: network-based (31%), product-based (37%), and waste-based (15%). The LCA approach and the definition of functional units largely depended on the scale of IS exchanges, though some variation existed within each scale. Company-level studies mainly adopted product-based FUs, district-level studies favoured network-based ones, and regional studies often used waste-based or undefined FUs, indicating higher inconsistency. Most papers employed a conventional process-based LCA, while some integrated complementary methods, such as LCC, MFA, or LCSA, to account for mass flow, economic, or social aspects.

As for the impact assessment methods, the reviewed studies showed considerable heterogeneity. Multiple scenario analysis, applied in 39 case studies, emerged as the most adopted component of LCAs of IS, though challenges remain in defining appropriate reference scenarios. While non-IS conditions were commonly used as baselines, the dynamic nature of IS also suggests the need to compare current IS practices with improved IS scenarios.

Overall, the studies confirmed the environmental benefits of IS over non-IS conditions across several impact categories. However, 25 out of 48 studies assessed fewer than four midpoint categories, namely climate change, acidification, eutrophication, and energy demand/resource use. Furthermore, output data were often insufficiently detailed to attribute impacts to specific entities, stages, or flows, limiting the robustness of result interpretation. While most studies confirmed that IS can effectively improve the environmental performance of companies, several limitations emerged. At the district level, 5 out of 21 studies reported only marginal or limited environmental benefits when assessed at the system level. Moreover, in many cases, alternative allocation choices or methodological assumptions further reduced the observed improvements. These findings highlight the need for more systematic applications of sensitivity and uncertainty analyses, which were rarely conducted in the reviewed studies.

This review highlights critical gaps in scenario development and sensitivity analyses, underscoring the need for more rigorous and context-sensitive approaches. Future research should avoid broad generalizations of prospective solutions and explicitly account for the diversity of LCA applications by considering the three IS perspectives (product-, network-, and waste-based). Furthermore, a path to explore would be the possibility of integrating results from industrial product-oriented assessments, conducted by companies and usually not published in the literature, within research results, to better support the identification and evaluation of IS strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cleantechnol7040100/s1. S1: Description of content analysis criteria. S2: Figures. Figure S1: Scales of the IS presented in the case studies based on system boundaries. Waste management WM(+): Cases in which at least one waste management company was involved in the exchange of solid waste materials as a provider or as a receiver. WM(-): Cases in which no waste management company was involved in the exchange of solid waste materials as a provider or as a receiver. Figure S2: Distribution of IS case studies based on the number of industries involved in each case study. Figure S3: Distribution of IS case studies based on number of waste flow types exchanged in each case study. Figure S4: Scopes of analyzed LCA case studies. Figure S5: Functional units (FU) in the analyzed case studies divided by the scales of IS exchanges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.V. and M.D.; methodology, R.V.; validation, M.D.; formal analysis, R.V.; investigation, R.V. and M.D.; data curation, R.V.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and R.V.; writing—review and editing, M.D.; visualization, R.V. and M.D.; supervision, G.B.; project administration, G.B.; funding acquisition: G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in Italy—Circular and Sustainable) Extended Partnership and received funding from Next-GenerationEU (Italian PNRR—M4 C2, Invest 1.3—D.D. 1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004 CUP D73C22001250001).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BAU | Business As Usual |

| ENA | Ecological Network Analysis |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| EU | European Union |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| IS | Industrial Symbiosis |

| ISN | Industrial Symbiosis Network |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCC | Life Cycle Cost |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| LCSA | Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment |

| MFA | Mass Flow Analysis |

| SME | Small–Medium Enterprises |

| UIS | Urban Industrial Symbiosis |

References

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial Symbiosis: Literature and Taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Godina, R.; Azevedo, S.G.; Pimentel, C.; Matias, J.C.O. The Potential of Industrial Symbiosis: Case Analysis and Main Drivers and Barriers to Its Implementation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demartini, M.; Tonelli, F.; Govindan, K. An Investigation into Modelling Approaches for Industrial Symbiosis: A Literature Review and Research Agenda. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2022, 3, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Davis, C.; Dijkema, G.P. Understanding the Evolution of Industrial Symbiosis Research: A Bibliometric and Network Analysis (1997–2012). J. Ind. Ecol. 2013, 18, 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Cellura, M.; Brano, V.L.; Mistretta, M. Life Cycle Assessment-Driven Selection of Industrial Ecology Strategies. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2010, 6, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, T.J.; Pakarinen, S.; Sokka, L. Quantifying the Total Environmental Impacts of an Industrial Symbiosis: A Comparison of Process-, Hybrid-, and Input–Output-Based Life Cycle Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4309–4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Chen, B.; Su, M.; Liu, G. A Review of Industrial Symbiosis Research: Theory and Methodology. Front. Earth Sci. 2015, 9, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.F.; Islam, K.; Islam, K.N. Industrial Symbiosis: A Review on Uncovering Approaches, Opportunities, Barriers and Policies. J. Civ. Eng. Environ. Sci. 2016, 2, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felicio, M.; Amaral, D.; Esposto, K.; Durany, X.G. Industrial Symbiosis Indicators to Manage Eco-Industrial Parks as Dynamic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 118, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daddi, T.; Nucci, B.; Iraldo, F. Using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to Measure the Environmental Benefits of Industrial Symbiosis in an Industrial Cluster of SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 147, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. International Organisation for Standardisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Kerdlap, P.; Low, J.S.C.; Ramakrishna, S. Life Cycle Environmental and Economic Assessment of Industrial Symbiosis Networks: A Review of the Past Decade of Models and Computational Methods through a Multi-Level Analysis Lens. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1660–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdlap, P.; Low, J.S.C.; Tan, D.Z.L.; Yeo, Z.; Ramakrishna, S. M3-IS-LCA: A Methodology for Multi-Level Life Cycle Environmental Performance Evaluation of Industrial Symbiosis Networks. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 161, 104963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Platform on LCA|EPLCA. 2025. Available online: https://eplca.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Yeo, Z.; Masi, D.; Low, J.S.C.; Ng, Y.T.; Tan, P.S.; Barnes, S. Tools for promoting industrial symbiosis: A systematic review. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1087–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, T.; Lehtoranta, S.; Sokka, L.; Melanen, M.; Nissinen, A. Methodological Aspects of Applying Life Cycle Assessment to Industrial Symbioses. J. Ind. Ecol. 2012, 16, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Svensson, N.; Eklund, M. Who gets the benefits? An approach for assessing the environmental performance of industrial symbiosis. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aissani, L.; Lacassagne, A.; Bahers, J.B.; Léonard de Féon, S. Life Cycle Assessment of Industrial Symbiosis: A Critical Review of Relevant Reference Scenarios. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 972–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadström, C.; Johansson, M.; Wallen, M. A Framework for Studying Outcomes in Industrial Symbiosis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, A.; Godina, R.; Azevedo, S.G.; Matias, J.C.O. A comprehensive review of industrial symbiosis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.K.; Kio, P.N.; Alvarado, J.; Wang, Y. Symbiotic Circularity in Buildings: An Alternative Path for Valorizing Sheet Metal Waste Stream as Metal Building Facades. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020, 11, 7127–7145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammenberg, J.; Baas, L.; Eklund, M.; Feiz, R.; Helgstrand, A.; Marshall, R. Improving the CO2 Performance of Cement, Part III: The Relevance of Industrial Symbiosis and How to Measure Its Impact. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansanelli, G.; Fiorentino, G.; Chifari, R.; Meisterl, K.; Leccisi, E.; Zucaro, A. Sustainability Assessment of Coffee Silverskin Waste Management in the Metropolitan City of Naples (Italy): A Life Cycle Perspective. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastias, F.A.; Rodríguez, P.D.; Arena, A.P.; Peiró, L.T. Measuring the Symbiotic Performance of Single Entities within Networks Using an LCA Approach. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcentales-Bastidas, D.; Silva, C.; Ramirez, A.D. The Environmental Profile of Ethanol Derived from Sugarcane in Ecuador: A Life Cycle Assessment Including the Effect of Cogeneration of Electricity in a Sugar Industrial Complex. Energies 2022, 15, 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, E.; Tanguy, A.; Glaus, M. Closing the Loop: Structural, Environmental and Regional Assessments of Industrial Symbiosis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 50, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blengini, G.A.; Busto, M.; Fantoni, M.; Fino, D. Eco-Efficient Waste Glass Recycling: Integrated Waste Management and Green Product Development through LCA. Waste Manag. 2012, 32, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capucha, F.; Henriques, J.; Ferrão, P.; Iten, M.; Margarido, F. Analysing Industrial Symbiosis Implementation in European Cement Industry: An Applied Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.; Gordon, M.; Hirsch, P.; Ramaswami, A. Industrial Symbiosis Potential and Urban Infrastructure Capacity in Mysuru, India. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 075003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, J.; Simon, B.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Amor, B. Is open-loop recycling the lowest preference in a circular economy? Answering through LCA of glass powder in concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 185, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maria, A.; Salman, M.; Dubois, M.; Van Acker, K. Life cycle assessment to evaluate the environmental performance of new construction material from stainless steel slag. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2018, 23, 2091–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Ohnishi, S.; Fujita, T.; Geng, Y.; Fujii, M.; Dong, L. Achieving carbon emission reduction through industrial & urban symbiosis: A case of Kawasaki. Energy 2014, 64, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Liang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Hu, M. Highlighting regional eco-industrial development: Life cycle benefits of an urban industrial symbiosis and implications in China. Ecol. Model. 2017, 361, 164–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Chertow, M.R. Life cycle energy and environmental benefits of a US industrial symbiosis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 1524–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Tsuyoshi, F.; Chen, X. Evaluation of innovative municipal solid waste management through urban symbiosis: A case study of Kawasaki. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobetti, A.; Cornacchia, G.; Tomasoni, G.; Dey, K.; Ramorino, G. Steel slag as a low-impact filler in rubber compounds for environmental sustainability. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2024, 39, 1830–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, H.; Välisuo, P.; Niemi, S. Modelling sustainable industrial symbiosis. Energies 2021, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, S.; Fujita, T.; Geng, Y.; Nagasawa, E. Realizing CO2 emission reduction through industrial symbiosis: A cement production case study for Kawasaki. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, J.; O’Keeffe, S.; Bezama, A.; Thrän, D. Revealing the Environmental Advantages of Industrial Symbiosis in Wood-Based Bioeconomy Networks: An Assessment From a Life Cycle Perspective. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Xuan, D.; Ng, S.T.; Amor, B. Designing sustainable partition wall blocks using secondary materials: A life cycle assessment approach. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilias, A.V.; Meletios, R.G.; Yiannis, K.A.; Nikolaos, B. Integration & assessment of recycling into c-Si photovoltaic module’s life cycle. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2018, 11, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerdlap, P.; Low, J.S.C.; Tan, D.Z.L.; Yeo, Z.; Ramakrishna, S. UM3-LCE3-ISN: A methodology for multi-level life cycle environmental and economic evaluation of industrial symbiosis networks. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1409–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-M.; Habert, G.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Amor, B. Assessing robustness of consequential LCA: Insights from a multiregional economic model tailored to the cement industrial symbiosis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2024, 28, 1392–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Feng, Z.; Wu, J.; Liang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, L. Cement kiln geared up to dispose industrial hazardous wastes of megacity under industrial symbiosis. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, P.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B.; Bian, H.; Qian, G. Life cycle assessment of an industrial symbiosis based on energy recovery from dried sludge and used oil. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 1700–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkowski, A. The spatial limits of environmental benefit of industrial symbiosis—Life cycle assessment study. J. Sustain. Dev. Energy Water Environ. Syst. 2019, 7, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Quantifying the environmental performance of an industrial symbiosis network of biofuel producers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 102, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Evaluating the environmental performance of producing soil and surfaces through industrial symbiosis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 626–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Harris, S. Prospecting the sustainability implications of an emerging industrial symbiosis network. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 138, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.; Weidner, T.; Gullström, C. Estimating the Potential of Building Integration and Regional Synergies to Improve the Environmental Performance of Urban Vertical Farming. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 849304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulu, A.; Vitvarová, M.; Kočí, V. Quantifying the industry-wide symbiotic potential: LCA of construction and energy waste management in the Czech Republic. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzulli, P.A.; Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Arcese, G.; Di Capua, R. Life cycle assessment of steel produced in an Italian integrated steel mill. Sustainability 2016, 8, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, L.R.; Dessureault, P.-L.; Marty, C.; Boucher, J.-F.; Paré, M.C. Life Cycle Assessment of Oat Flake Production with Two End-of-Life Options for Agro-Industrial Residue Management. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, M.; Castellani, V.; Orlandi, M.; Collina, E. Use of Lignin side-streams from biorefineries as fuel or co-product? Life cycle analysis of bio-ethanol and pulp production processes. BioResources 2019, 14, 4832–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharib, S.; Halog, A. Enhancing value chains by applying industrial symbiosis concept to the Rubber City in Kedah, Malaysia. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, F.; Rios-Davila, F.-J.; Paiva, H.; Morais, M.; Ferreira, V.M. Sustainability Evaluation of a Paper and Pulp Industrial Waste Incorporation in Bituminous Pavements. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokka, L.; Lehtoranta, S.; Nissinen, A.; Melanen, M. Analyzing the Environmental Benefits of Industrial Symbiosis: Life Cycle Assessment Applied to a Finnish Forest Industry Complex. J. Ind. Ecol. 2011, 15, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strazza, C.; Magrassi, F.; Gallo, M.; Del Borghi, A. Life Cycle Assessment from food to food: A case study of circular economy from cruise ships to aquaculture. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 2, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, P.; Napolitano, R.; Colella, F.; Menna, C.; Asprone, D. Cement-matrix composites using CFRP waste: A circular economy perspective using industrial symbiosis. Materials 2021, 14, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Gao, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, R. Life cycle assessment of reduction of environmental impacts via industrial symbiosis in an energy-intensive industrial park in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 241, 118358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, R.; Yue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, G. Toward a Sustainable Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly-Ash Utilization Network: Integrating Hybrid Life Cycle Assessment with Multiobjective Optimization. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 7635–7647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, R.; Wang, S.; Gao, G.; Liu, D.; Long, W.; Zhang, R. Evaluation of symbiotic technology-based energy conservation and emission reduction benefits in iron and steel industry: Case study of Henan, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 338, 130616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Han, F.; Cui, Z. Assessment of life cycle environmental benefits of an industrial symbiosis cluster in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 5511–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Bi, X.; Clift, R. Synthesis and assessment of a biogas-centred agricultural eco-industrial park in British Columbia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, S.; Li, J.; Shao, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S. Life cycle assessment of industrial symbiosis in Songmudao chemical industrial park, Dalian, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 158, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidzadeh, R.; Bertanza, G. Industrial symbiosis and eco-industrial parks. In Environmental Sustainability and Industries: Technologies for Solid Waste, Wastewater, and Air Treatment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 405–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahidzadeh, R.; Bertanza, G.; Sbaffoni, S.; Vaccari, M. Regional industrial symbiosis: A review based on social network analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domini, M.; Vahidzadeh, R.; Vaccari, M.; Sbaffoni, S.; De Marco, E.; Beltrani, T.; Bertanza, G. Regional industrial symbiosis networks for waste minimisation: A case study from Italy. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carissimi, M.C.; Hameed, H.B.; Creazza, A. Circular economy: The future nexus for sustainable and resilient supply chains? Sustain. Future 2024, 8, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, A.; Sporchia, F.; Niccolucci, V.; Pulselli, F.M.; Bastianoni, S. Rethinking environmental benefit allocation in industrial symbiosis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 992, 179932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsen, F.; Hansen, K.S.H.; Ghose, A.; Pizzol, M. Same product, different score: How methodological differences affect EPD results. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]