Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

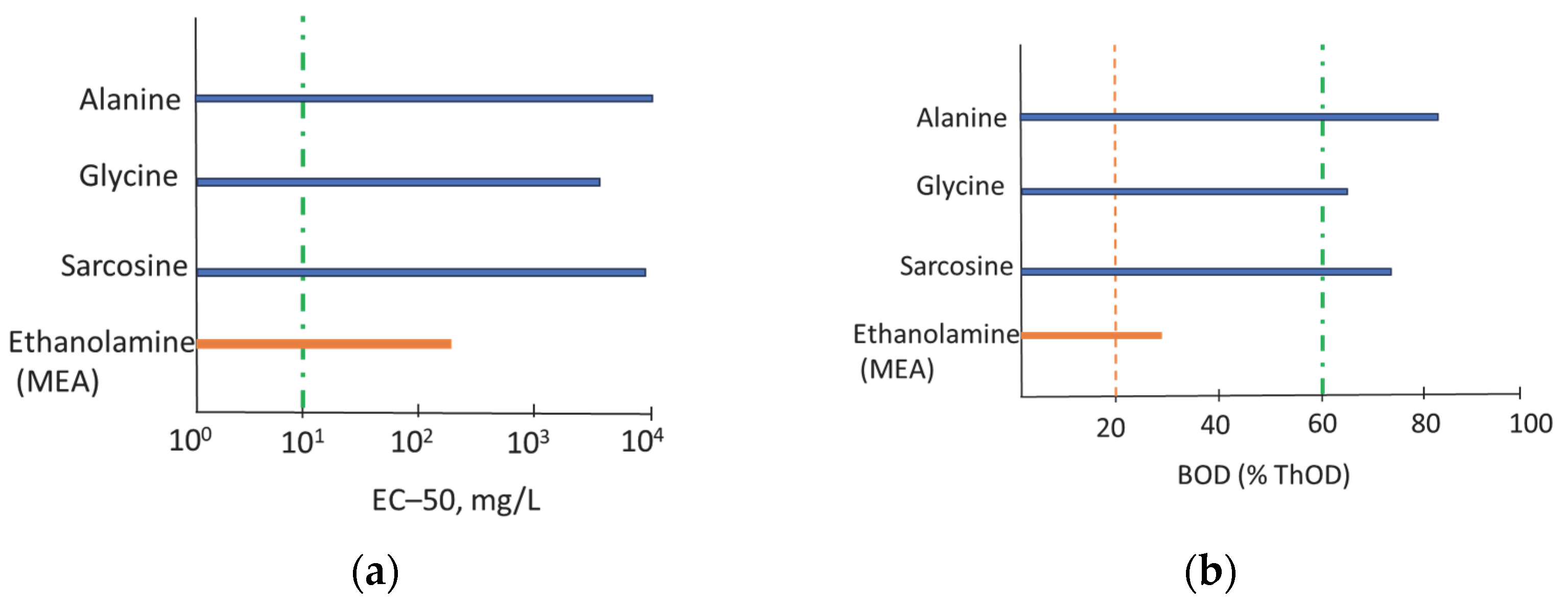

2.1. Green Absorbent Characterization

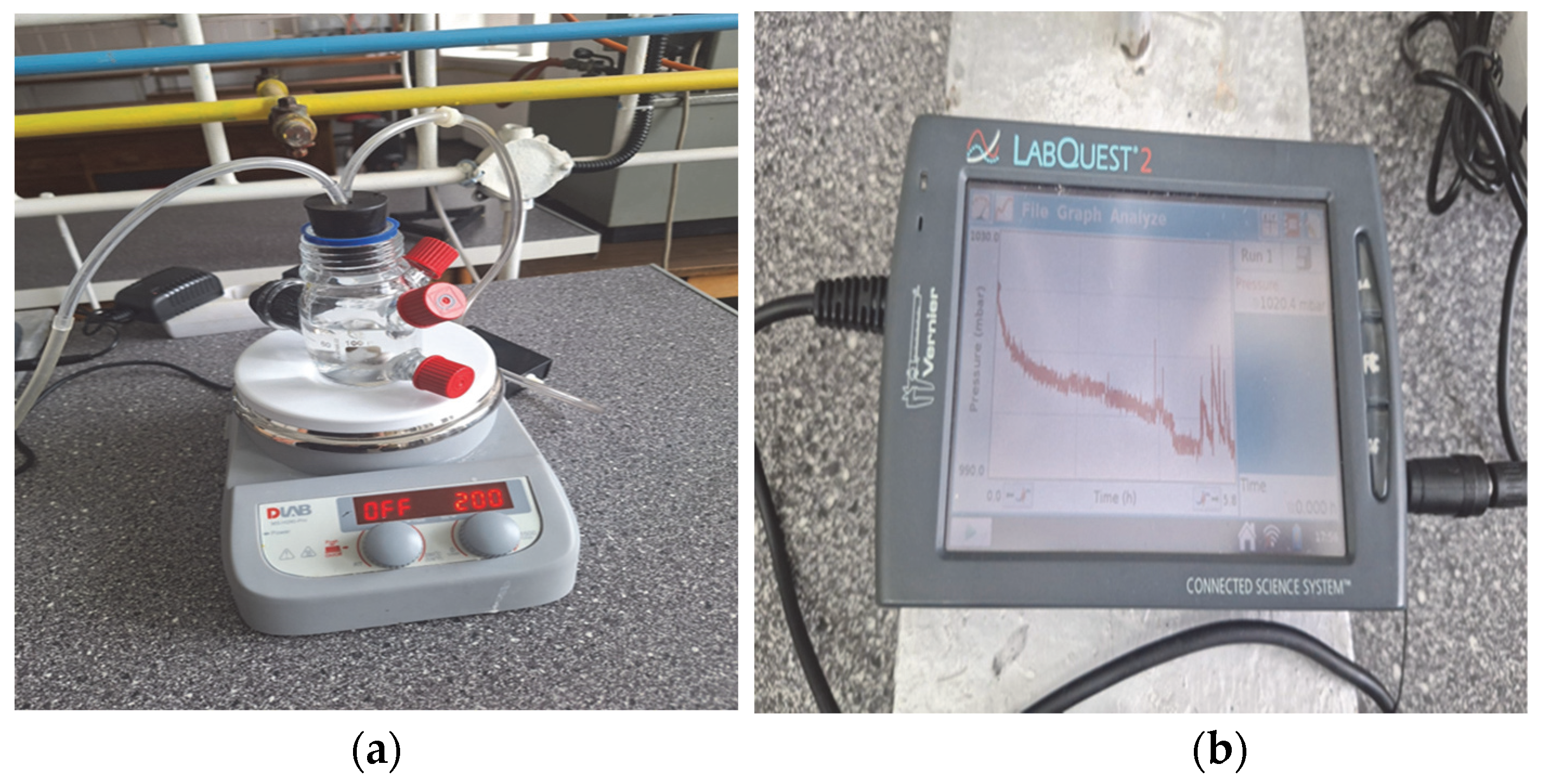

2.2. Absorption Studies

3. Results and Discussions

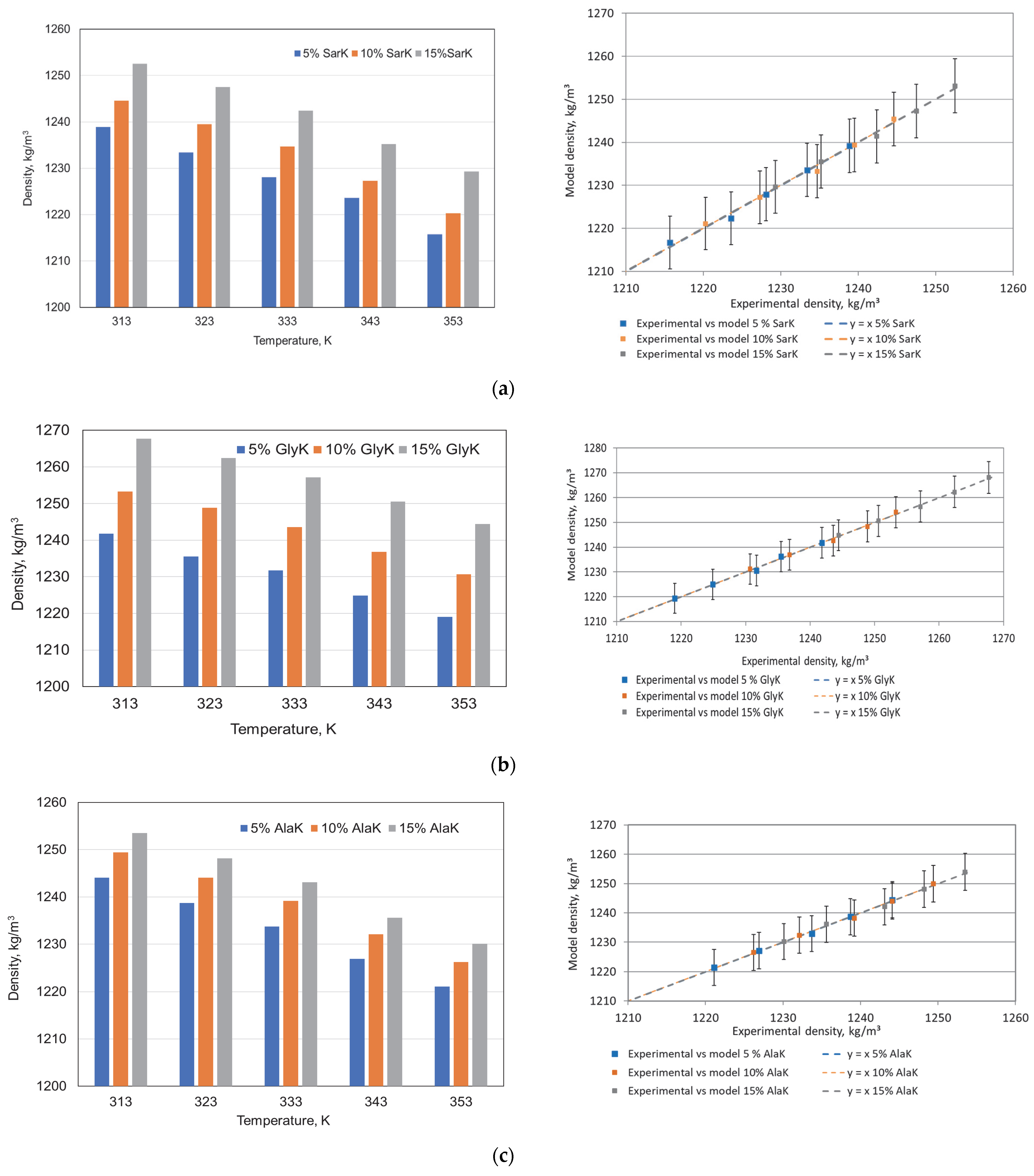

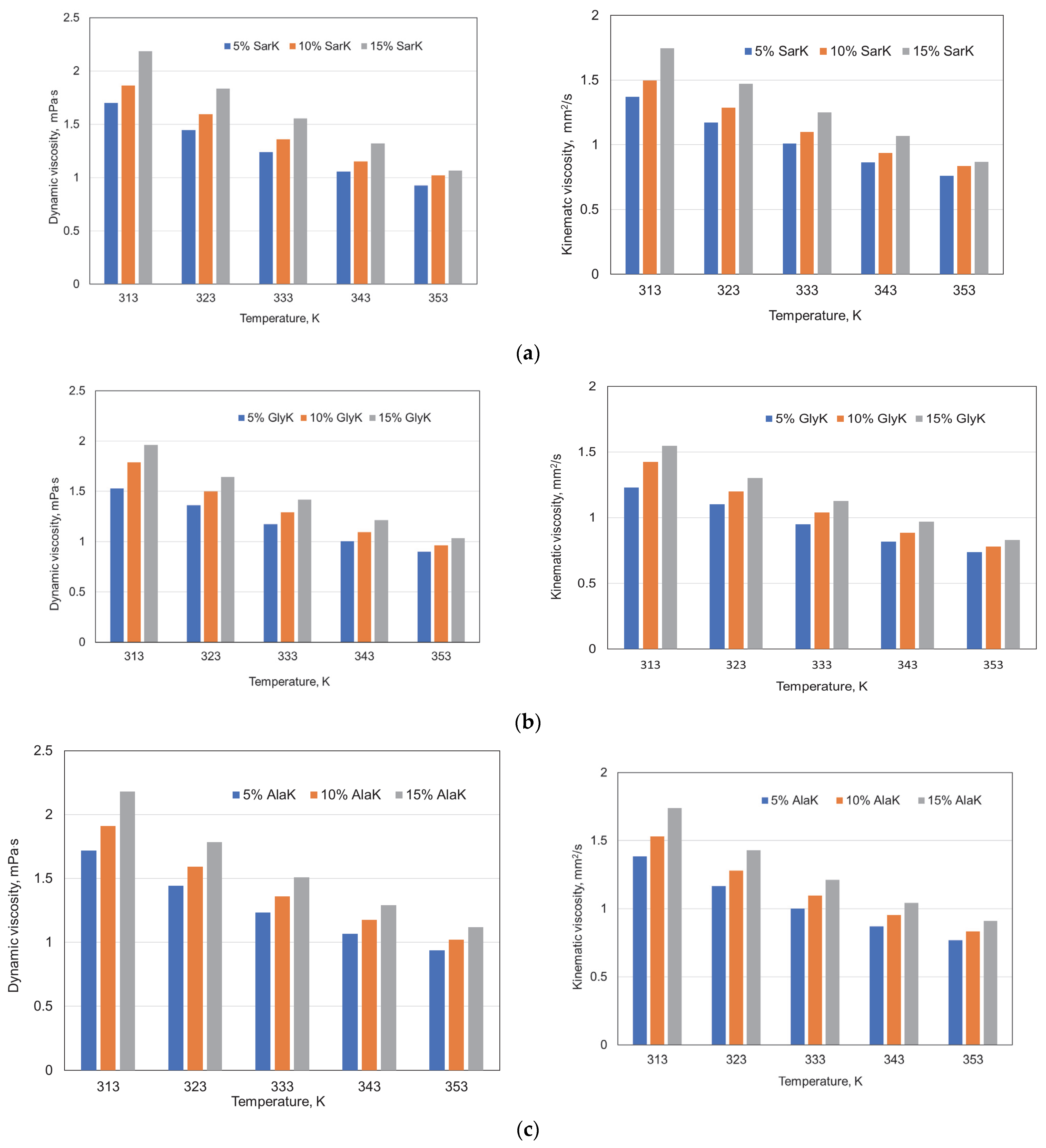

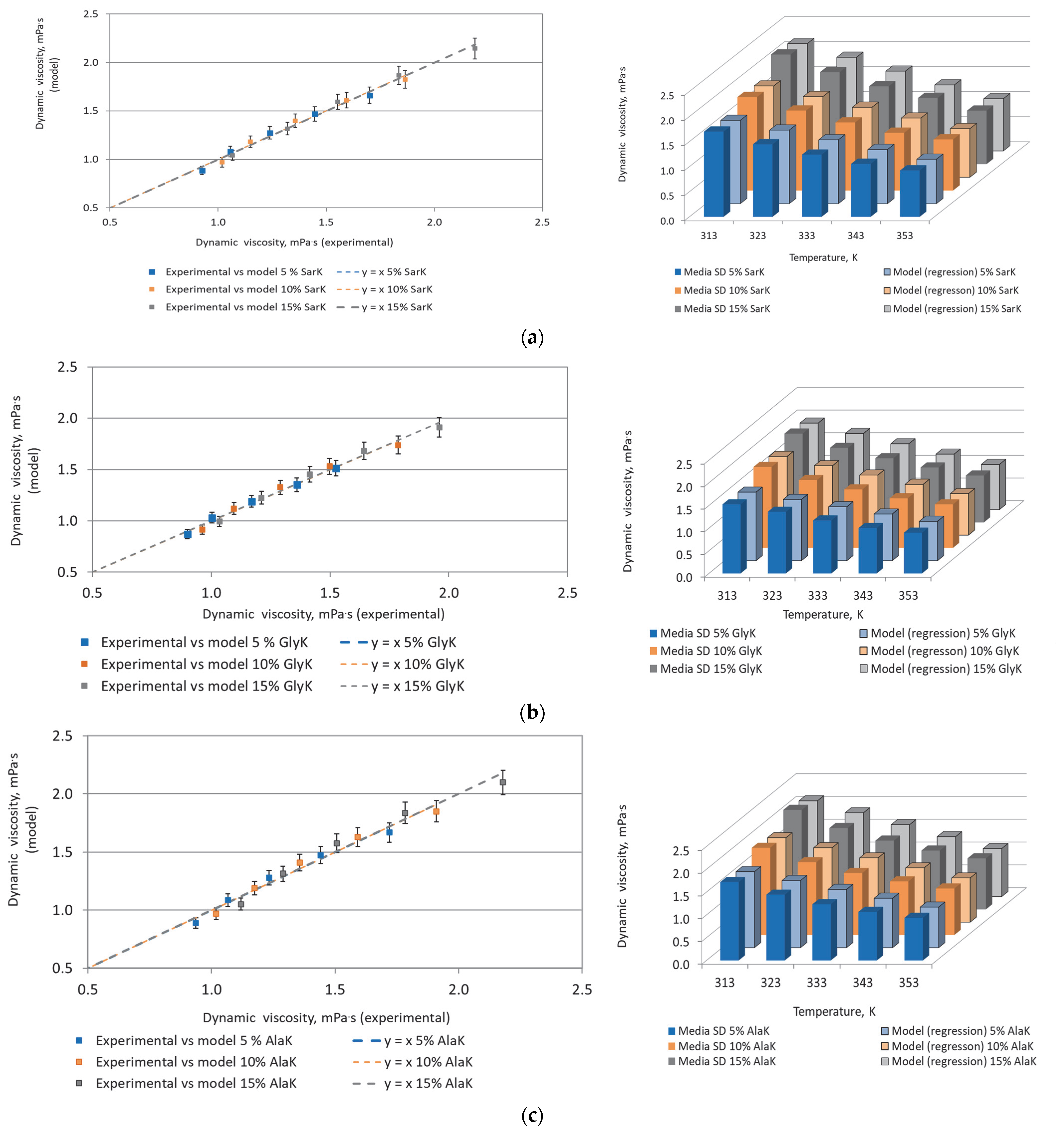

3.1. Properties of Green Absorbents

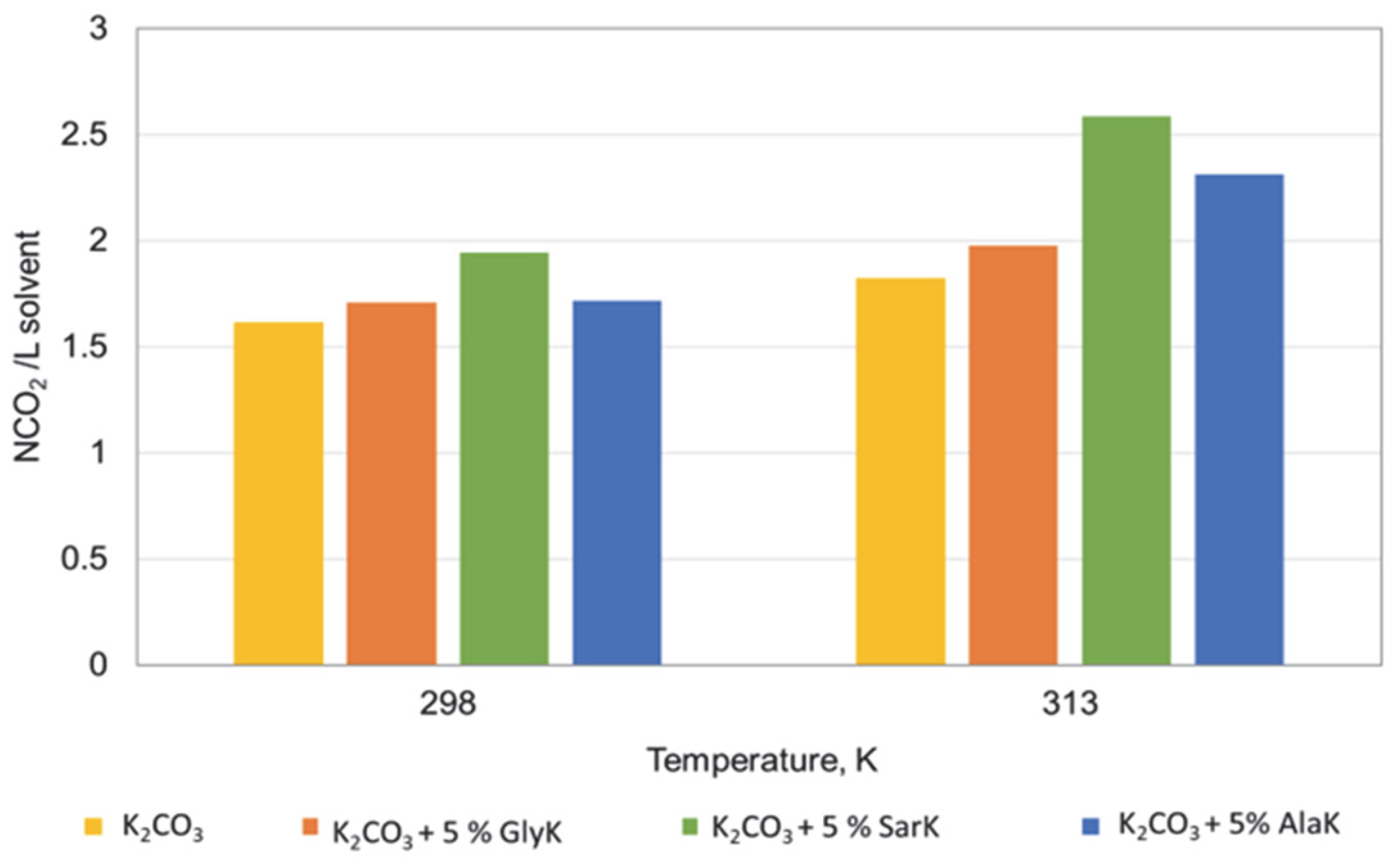

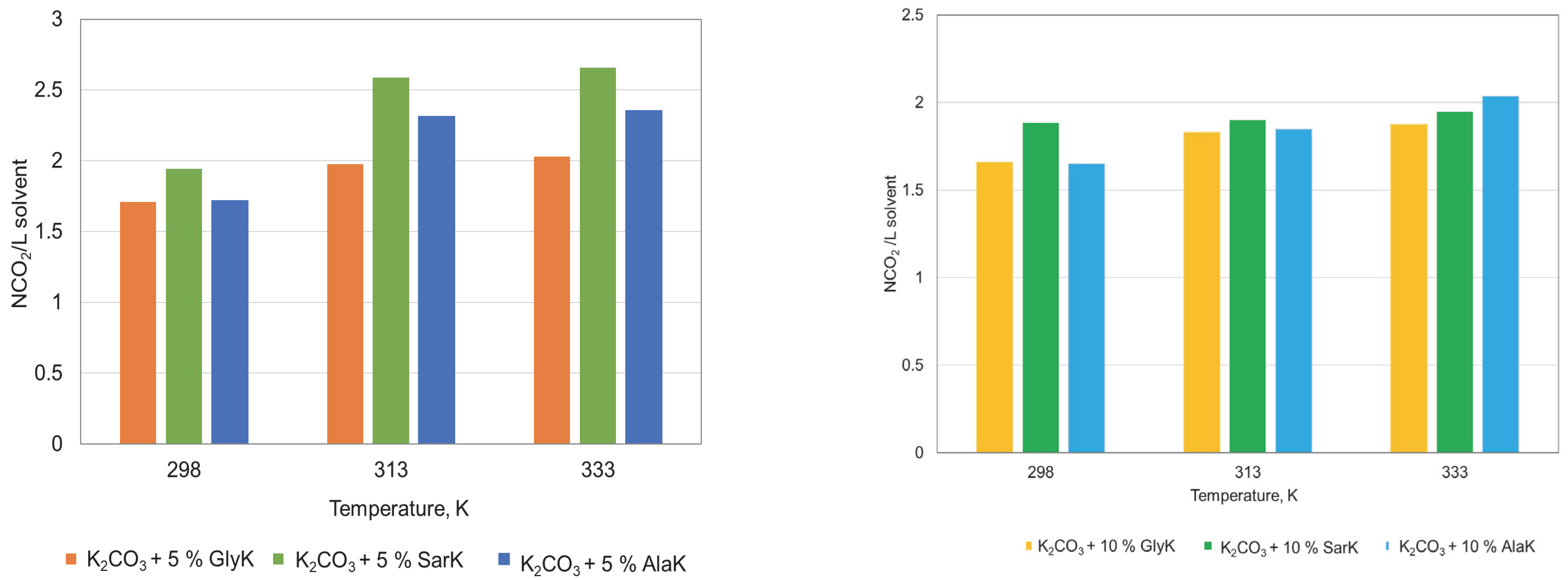

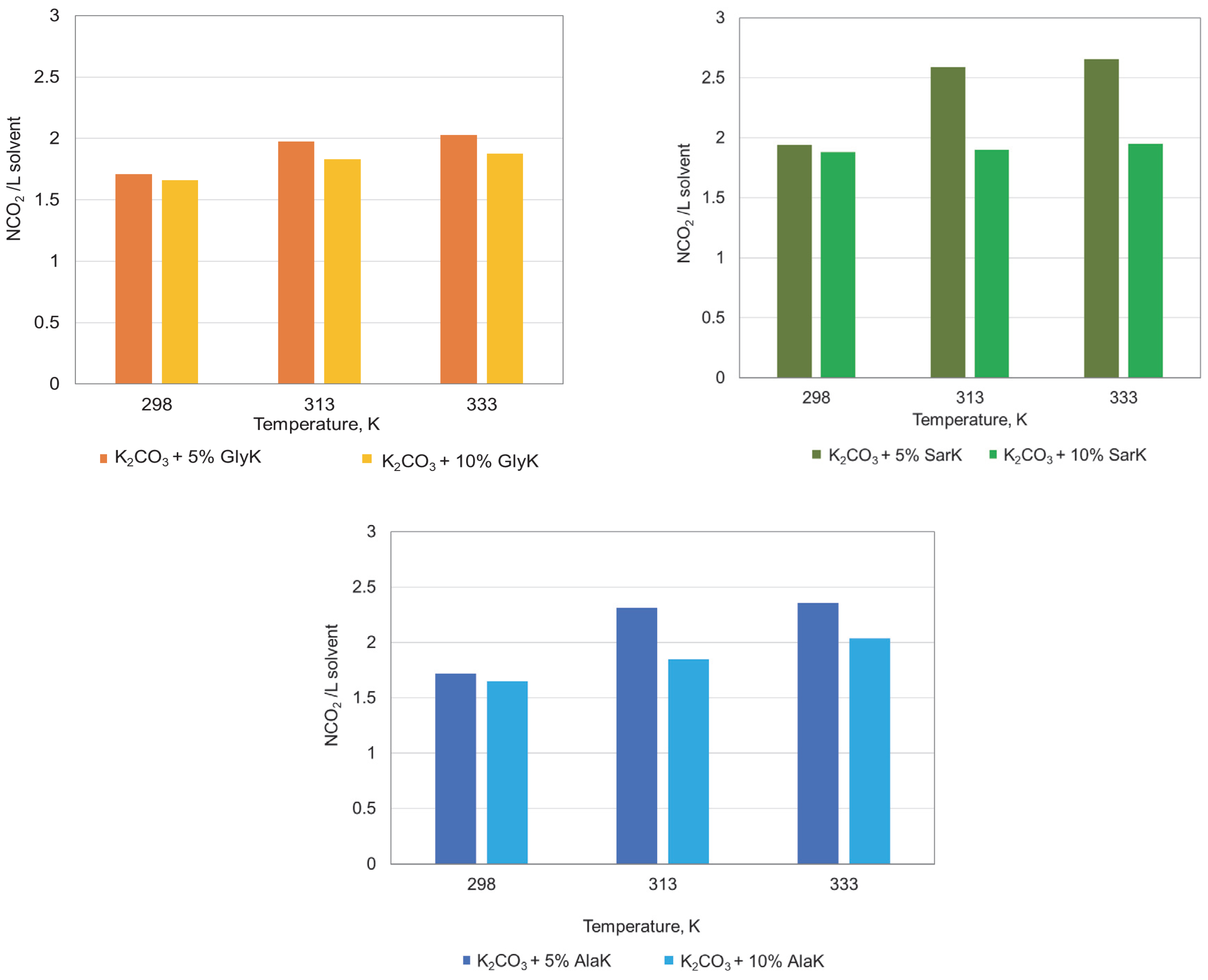

3.2. Influence of Parameters on Absorption

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GHGs | Greenhouse gases |

| CCS | Carbon capture and storage |

| PCC | Post-combustion CO2 capture |

| MEA | Monoethanolamine |

| DEA | Diethanolamine |

| MDEA | Methyldiethanolamine |

| DGA | Diglycolamine |

| DIPA | Diisopropylamine |

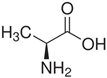

| Ala | Alanine |

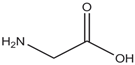

| Gly | Glycine |

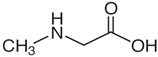

| Sar | Sarcosine |

| AlaK | Alanine potassium salt |

| GlyK | Glycine potassium salt |

| SarK | Sarcosine potassium salt |

| AAS | Amino acid salts |

| AAK | Amino acid potassium salt |

| EC–50 | Ecotoxicity |

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| ThOD | Theoretical oxygen demand |

| RSD | Residual Standard Deviation |

References

- Siddik, M.; Islam, M.; Zaman, A.K.M.M.; Hasan, M. Current status and correlation of fossil fuels consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. Int. J. Energy Environ. Econ. 2021, 28, 103–119. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, F.; Felgueiras, C.; Smitkova, M.; Caetano, N. Analysis of fossil fuel energy consumption and environmental impacts in European countries. Energies 2019, 12, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, L.; Gencel, O.; Damian, I.; Harja, M. Capitalization of tires waste as derived fuel for sustainable cement production. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 56, 103104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiliu, L.; Lazăr, L.; Harja, M. Reducing the carbon dioxide footprint of inorganic binders industry. J. Int. Sci. Pub. Ecol. Safety 2023, 17, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, M.; Eberhardt, W. A simple model for the prediction of CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere, depending on global CO2 emissions. Eur. J. Phys. 2024, 45, 025803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.; Lu, X.; Wang, D. A systematic review of carbon capture, utilization and storage: Status, progress and challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, H.; Gonzales Calienes, G.; Shadbahr, J. Ex Situ Carbon Mineralization for CO2 Capture Using Industrial Alkaline Wastes—Optimization and Future Prospects: A Review. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Peng, Z.; Pei, Y.; Ajmal, T.; Rana, K.J.; Aitouche, A.; Mobasheri, R. Oxy-fuel combustion for carbon capture and storage in internal combustion engines–A review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harja, M.; Ciobanu, G.; Juzsakova, T.; Cretescu, I. New approaches in modeling and simulation of CO2 absorption reactor by activated potassium carbonate solution. Processes 2019, 7, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragan, S.; Lisei, H.; Ilea, F.M.; Bozonc, A.C.; Cormos, A.M. Dynamic Modeling Assessment of CO2 Capture Process Using Aqueous Ammonia. Energy 2023, 16, 4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, N.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Kong, F.; Li, X.; Ren, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, S. Novel amine emissions control methods for CO2 capture based on reducing amine concentration in the scrubbing liquid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 354, 129295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krótki, A.; Solny, L.W.; Stec, M.; Spietz, T.; Wilk, A.; Chwoła, T.; Jastrząb, K. Experimental results of advanced technological modifications for a CO2 capture process using amine scrubbing. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2020, 96, 103014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunlami, O.A.; Vershima, D.A.; Oladimeji, T.E.; Nkongho, S.; Ogunlade, S.K.; Fakinle, B.S. Advanced techniques for the capturing and separation of CO2—A review. Results Eng. 2022, 15, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, Z.L.; Tan, P.Y.; Tan, L.S.; Yeap, S.P. Amine-based solvent for CO2 absorption and its impact on carbon steel corrosion: A perspective review. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessel, V.; Tran, N.N.; Asrami, M.R.; Tran, Q.D.; Long, N.V.D.; Escribà-Gelonch, M.; Tejada, J.O.; Linke, S.; Sundmacher, K. Sustainability of green solvents–review and perspective. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 410–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Gopinath, K.P.; Vo, D.V.N.; Malolan, R.; Nagarajan, V.M.; Arun, J. Ionic liquids, deep eutectic solvents and liquid polymers as green solvents in carbon capture technologies: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 2031–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshid, G.; Butt, W.A.; Garg, S. Investigation of thermophysical properties for aqueous blends of sarcosine with 1-(2-aminoethyl) piperazine and diethylenetriamine as solvents for CO2 absorption. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 278, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Soltanian, M.R.; Olabi, A.G. Effectiveness of amino acid salt solutions in capturing CO2: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 98, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, R.; Mazinani, S.; Di Felice, R. State–of–the–art of CO2 capture with amino acid salt solutions. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2022, 38, 273–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Smith, K.H.; Wu, Y.; Mumford, K.A.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. Carbon dioxide capture by solvent absorption using amino acids: A review. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 2229–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariff, A.M.; Shaikh, M.S. Aqueous Amino Acid Salts and Their Blends as Efficient Absorbents for CO2 Capture. In Energy Efficient Solvents for CO2 Capture by Gas-Liquid Absorption. Green Energy and Technology; Budzianowski, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrowicz, M.E.; Brilman, D.W.; Groeneveld, M.J. Precipitation regime for selected amino acid salts for CO2 capture from flue gases. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, J.P.; Feron, P.H.M.; Ten Asbroek, N.A.M. Amino-acid salts for CO2 capture from flue gases. In Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference on Carbon Capture & Sequestration, Alexandria, VA, USA, 2–5 May 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feron, P.H.; Asbroek, N. New solvents based on amino-acid salts for CO2 capture from flue gases. In Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 1153–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.C.; Puxty, G.; Feron, P. Amino acid salts for CO2 capture at flue gas temperatures. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2014, 107, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Borhani, T.N.; Olabi, A.G. Status and perspective of CO2 absorption process. Energy 2020, 205, 118057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Liu, Y.; Wang, K. Detailed experimental study on the performance of Monoethanolamine, Diethanolamine, and Diethylenetriamine at absorption/regeneration conditions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 125, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Bao, Z.; Akhmedov, N.G.; Li, B.A.; Duan, Y.; Xing, M.; Wang, J.; Morsi, B.; Li, B. Unraveling the role of Glycine in K2CO3 solvent for CO2 removal. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 12545–12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Nicholas, N.J.; Smith, K.H.; Mumford, K.A.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. Carbon dioxide absorption into promoted potassium carbonate solutions: A review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2016, 53, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harja, M.; Hultuană, E.; Apostolescu, N.; Apostolescu, G.A.; Tataru Farmus, R.E. Viscosity of potassium carbonate solutions promoted by new amines. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. 2020, 5, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isa, F.; Zabiri, H.; Ng, N.K.S.; Shariff, A.M. CO2 removal via promoted potassium carbonate: A review on modeling and simulation techniques. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2018, 76, 236–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thee, H.; Suryaputradinata, Y.A.; Mumford, K.A.; Smith, K.H.; da Silva, G.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. A kinetic and process modeling study of CO2 capture with MEA-promoted potassium carbonate solutions. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 210, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullinane, J.T.; Rochelle, G.T. Carbon dioxide absorption with aqueous potassium carbonate promoted by piperazine. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 3619–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borhani, T.N.G.; Azarpour, A.; Akbari, V.; Alwi, S.R.W.; Manan, Z.A. CO2 capture with potassium carbonate solutions: A state-of-the-art review. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 41, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, X. Experimental studies on carbon dioxide absorption using potassium carbonate solutions with amino acid salts. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 219, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Alivand, M.S.; Hu, G.; Stevens, G.W.; Mumford, K.A. Nucleation kinetics of glycine promoted concentrated potassium carbonate solvents for carbon dioxide absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Smith, K.H.; Wu, Y.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. Screening amino acid salts as rate promoters in potassium carbonate solvent for carbon dioxide absorption. Energy Fuels 2017, 31, 4280–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thee, H.; Nicholas, N.J.; Smith, K.H.; da Silva, G.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. A kinetic study of CO2 capture with potassium carbonate solutions promoted with various amino acids: Glycine, sarcosine and proline. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2014, 20, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.; Lee, A.; Mumford, K.; Li, S.; Thanumurthy, N.; Temple, N.; Anderson, C.; Hooper, B.; Kentish, S.; Stevens, G. Pilot plant results for a precipitating potassium carbonate solvent absorption process promoted with glycine for enhanced CO2 capture. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 135, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Myers, M.B.; Versteeg, F.G.; Adam, E.; White, C.; Crooke, E.; Wood, C.D. Next generation amino acid technology for CO2 capture. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 1692–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Wolf, M.; Kromer, N.; Mumford, K.A.; Nicholas, N.J.; Kentish, S.E.; Stevens, G.W. A study of the vapour–liquid equilibrium of CO2 in mixed solutions of potassium carbonate and potassium glycinate. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 36, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang Sefidi, V.; Luis, P. Advanced amino acid-based technologies for CO2 capture: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 20181–20194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Brilman, W.; Mengers, H.; Nijmeijer, K.; Wessling, M. Kinetics of CO2 absorption in aqueous sarcosine salt solutions: Influence of concentration, temperature, and CO2 loading. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 9693–9702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Thee, H.; Tan, C.Y.; Chen, J.; Fei, W.; Kentish, S.; Stevens, G.W.; da Silva, G. Amino acids as carbon capture solvents: Chemical kinetics and mechanism of the glycine+ CO2 reaction. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 3898–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.A.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, Y.; Jeong, S.K.; Park, K.T.; Nam, S.C. Absorption of CO2 into aqueous potassium salt solutions of L-alanine and L-proline. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 3910–3918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Gaur, A.; Park, J.W.; Lee, S.J. Carbon dioxide absorption characteristics of aqueous amino acid salt solutions. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2012, 11, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Song, H.J.; Lee, M.G.; Jo, H.Y.; Park, J.W. Kinetics and steric hindrance effects of carbon dioxide absorption into aqueous potassium alaninate solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 2570–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellah, M.H.; Kiani, A.; Conway, W.; Puxty, G.; Feron, P. A mass transfer study of CO2 absorption in aqueous solutions of isomeric forms of sodium alaninate for direct air capture application. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tătaru-Fărmuș, R.E.; Apostolescu, N.; Cernătescu, C.; Cobzaru, C.; Poroch, M. Screening of the amino acid-based solvents for carbon dioxide absorption. Bul. Inst. Polit. Iasi Chem. Chem. Eng. 2022, 68, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, R.; Stangeland, A. Amines Used in CO2 Capture-Health and Environmental Impacts; The Bellona Foundation: Oslo, Norway, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Garg, S.; Shariff, M.A.; Shaikh, M.S.; Lal, B.; Aftab, A.; Faiqa, N. Measurement and prediction of physical properties of aqueous sodium salt of L-phenylalanine. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2017, 82, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili-Nezhaad, G.R.; Al-Mammari, R.; Gujarathi, A.M.; Ahmad, W. Thermophysical properties for the binary mixtures of tert-amyl methyl ether with n–hexane, cyclopentane, benzene and m-xylene at different temperatures. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 252, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’mun, S. Solubility of carbon dioxide in aqueous solution of potassium sarcosine from 353 to 393 K. Energy Procedia 2014, 51, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Sar | Gly | Ala |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical formula | C3H7NO2 | C2H5NO2 | C3H7NO2 |

| - |  |  |  |

| CAS | 107-97-1 | 56-40-6 | 56-41-7 |

| Molecular weight (kg/kmol) | 89.093 | 75.07 | 89.10 |

| Density at 293 K (kg/m3) | 1093 | 1161 | 1424 |

| Solubility in water (g/L) (at 20 °C) | 89.09 | 249.9 | 167.2 |

| pH of 1 wt.% solution | 11.64 | 9.6 | 9.87 |

| AAKs | - | a | b | R2 | RSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SarK | 5% | −0.562 | 1415.1 | 0.9913 | 0.832 |

| 10% | −0.608 | 1435.7 | 0.9908 | 0.925 | |

| 15% | −0.587 | 1436.9 | 0.9951 | 0.652 | |

| GlyK | 5% | −0.562 | 1417.7 | 0.9941 | 0.683 |

| 10% | −0.573 | 1433.5 | 0.9937 | 0.722 | |

| 15% | −0.584 | 1450.9 | 0.9978 | 0.435 | |

| AlaK | 5% | −0.578 | 1425.4 | 0.9973 | 0.472 |

| 10% | −0.584 | 1432.7 | 0.9959 | 0.592 | |

| 15% | −0.594 | 1439.9 | 0.9955 | 0.629 |

| AAKs | - | a | b | R2 | RSD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SarK | 5% | −0.0194 | 7.7325 | 0.9864 | 0.036 |

| 10% | −0.0213 | 8.5030 | 0.9850 | 0.042 | |

| 15% | −0.0276 | 10.7677 | 0.9932 | 0.036 | |

| GlyK | 5% | −0.0161 | 6.5542 | 0.9911 | 0.024 |

| 10% | −0.0205 | 8.1584 | 0.9823 | 0.043 | |

| 15% | −0.0228 | 9.0507 | 0.9868 | 0.042 | |

| AlaK | 5% | −0.0194 | 7.7461 | 0.9788 | 0.045 |

| 10% | −0.0220 | 8.7375 | 0.9789 | 0.051 | |

| 15% | −0.0262 | 10.2849 | 0.9727 | 0.059 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tataru-Farmus, R.E.; Harja, M.; Tonucci, L.; Coccia, F.; Ciulla, M.; Lazar, L.; Soreanu, G.; Cretescu, I. Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts. Clean Technol. 2025, 7, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040099

Tataru-Farmus RE, Harja M, Tonucci L, Coccia F, Ciulla M, Lazar L, Soreanu G, Cretescu I. Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts. Clean Technologies. 2025; 7(4):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040099

Chicago/Turabian StyleTataru-Farmus, Ramona Elena, María Harja, Lucia Tonucci, Francesca Coccia, Michele Ciulla, Liliana Lazar, Gabriela Soreanu, and Igor Cretescu. 2025. "Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts" Clean Technologies 7, no. 4: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040099

APA StyleTataru-Farmus, R. E., Harja, M., Tonucci, L., Coccia, F., Ciulla, M., Lazar, L., Soreanu, G., & Cretescu, I. (2025). Green CO2 Capture from Flue Gas Using Potassium Carbonate Solutions Promoted with Amino Acid Salts. Clean Technologies, 7(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/cleantechnol7040099