Abstract

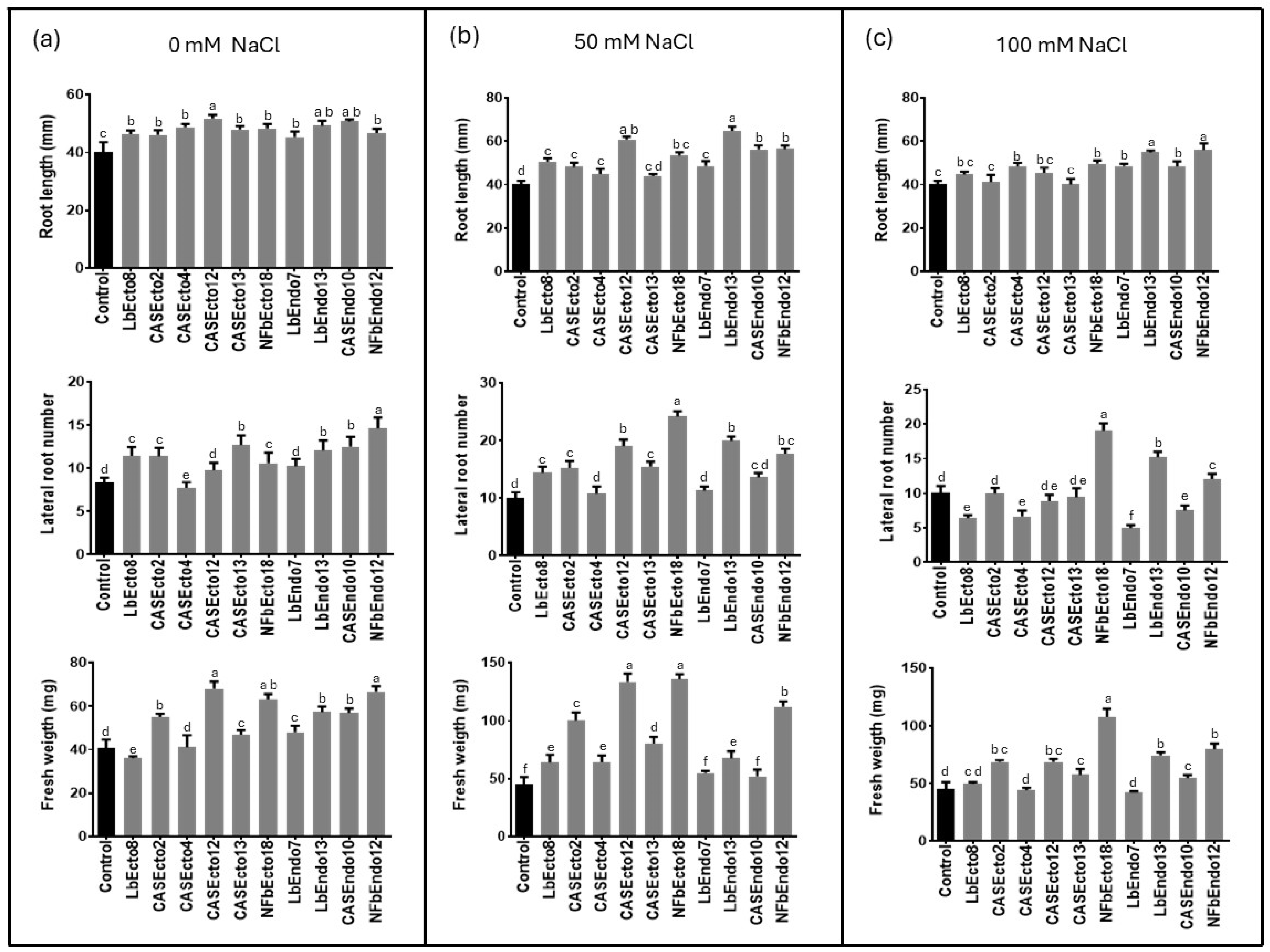

Soil salinity imposes a critical constraint on plant productivity, highlighting the need for sustainable biological strategies to enhance stress tolerance. This study assessed the effects of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by ten plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) isolated from the rhizosphere of Euphorbia antisyphilitica on the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings exposed to 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl. A divided Petri dish system was used to quantify biomass, root architecture, proline accumulation, sodium content, and chlorophyll concentration. Three strains—Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12, Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, and Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12—significantly enhanced seedling development under saline and non-saline conditions (p ≤ 0.05). At 50 mM NaCl, S. colletis CASEcto12 increased primary root length from 40.25 to 64.81 mm and fresh weight from 45.05 to 133.33 mg, while E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 elevated lateral root number from 10 to 24, compared to the uninoculated control. Under 100 mM NaCl, E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 increased proline accumulation (0.564–1.378 mmol g−1 FW) and reduced Na+ content (0.146–0.084 mmol g−1 FW), indicating improved osmotic and ionic regulation. VOC profiling using SPME-GC-MS revealed aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols as predominant classes. Overall, these findings demonstrate the potential of candelilla-associated PGPR VOCs as promising biostimulants for enhancing plant performance in salt-affected soils.

1. Introduction

Soil salinization is characterized by the excessive accumulation of soluble salts in the soil profile, a critical issue that severely reduces crop yields, increases plant mortality, degrades soil quality, and often leads to the abandonment of agricultural land [1]. Globally, approximately 1 billion hectares are affected by salinity, with arid and semi-arid areas being the most impacted [2]. In irrigated lands, 20–30% are already affected by salinity, significantly limiting their productivity [1]. Salt accumulation can stem from both primary (natural or geological) and secondary (human activity) causes, but its effect on plants is uniform: it disrupts multiple physiological functions by creating osmotic imbalances, inhibiting root growth, and altering root architecture, thereby reducing water and nutrient uptake [3]. Furthermore, high salt levels trigger the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), compromising cell viability, photosynthetic pigment stability, membrane integrity, and hormonal balance [4,5].

To mitigate the impacts of salinity on soils and crops, researchers have explored the use of various strategies, including plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). These beneficial microorganisms colonize the rhizosphere and promote plant development, enhancing tolerance to both abiotic and biotic stresses [6]. Their mechanisms include phytohormone production (indole-3-acetic acid, gibberellic acid, and cytokinins); improved nutrient availability through phosphate solubilization and siderophore production; ACC deaminase activity; and the release of secondary metabolites such as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) [7].

Growing interest in VOCs produced by microorganisms has led to several lines of research aimed at understanding their influence on plants and their potential applications in agriculture and biotechnology. VOCs—low-molecular-weight, lipophilic compounds with distinctive odors, high vapor pressures, and low boiling points—easily diffuse through soil pores. Nearly 2000 VOCs from about 1000 microbial species have been described [8,9]. Microbial VOCs include alkenes, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, terpenes, benzenoids, pyrazines, aromatic and aliphatic hydrocarbons, acids, esters, and nitrogen- or sulfur-containing compounds [10,11,12,13]. These metabolites can induce plant resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses and promote growth.

Microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) produced by plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) have been recognized as chemical signals capable of modulating plant development and physiology, although they still receive less attention than other plant–microbe interaction mechanisms. Several reviews have highlighted that mVOCs can induce pathways associated with growth, defense, and abiotic stress tolerance through hormonal regulation, redox balance modulation, and ion homeostasis adjustment [14,15]. Experimental studies have shown that certain bacterial VOCs improve salt tolerance in model plants and crops, mainly through strains of widely studied genera such as Bacillus and Pseudomonas [16,17]. However, significant gaps in knowledge remain: there are a limited number of studies that systematically characterize the VOCs emitted by less studied PGPR, as well as their effects on Arabidopsis thaliana under controlled salinity conditions [18]. This gap hinders our understanding of the specific mechanisms involved and highlights the need for studies that integrate chemical analyses of VOCs with the physiological and molecular responses of the plant, such as the one proposed here.

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of VOCs emitted by PGPR on A. thaliana seedlings’ development under varying salinity conditions, using physiological and biochemical assays alongside volatile profile analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Rhizobacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The rhizobacterial strains used in this study were isolated from the rhizosphere of Euphorbia antisyphilitica Zucc. (candelilla), a plant endemic to the Chihuahuan Desert in northern Mexico. Rhizosphere samples were collected from the municipality of Viesca, Coahuila, Mexico (25°10′41″ N, 102°39′12″ W). In previous research, these bacterial strains were shown to possess multiple traits associated with plant growth promotion in A. thaliana seedlings [19].

From the original 21 strains identified as plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR), 10 high-performing strains were selected for this study. The selection was based on a dual assessment: the most efficient plant growth promotion in preliminary A. thaliana assays and the highest tolerance to salinity stress (where the tolerance criterion was confirmed by their growth on LB solid medium supplemented with high concentrations of NaCl). These 10 selected strains were further assessed for their ability to emit volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Detailed information on the isolation and initial PGPR characterization of the 21 strains is available in the previous publication [19]. The strains were molecularly identified through 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Although some strains in the previous publication were reported with low identity percentages or short sequence lengths [19], molecular identification in the present study was improved and updated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Molecular identification of bacteria isolated from candelilla rhizosphere.

2.2. Plant Material and In Vitro Evaluation of PGPR-Emitted VOCs Under Salinity Stress

A. thaliana seeds (ecotype Col-0) were surface-sterilized in Eppendorf tubes using 20% (v/v) solution of commercial sodium hypochlorite (which corresponds to an approximate concentration of 1.0–1.2% active NaOCl), with agitation on a vortex for 5 min [20]. The seeds were then rinsed four times with sterile distilled water. To synchronize germination, the seeds underwent vernalization at 4 °C for 48 h. A total of 45 seeds were sown on Petri dishes containing 0.2× Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium prepared using the standard Murashige and Skoog basal salt mixture and vitamin formulation (PhytoTech Labs, product number M519) and diluted to 20% of its final working concentration. The plates were incubated in a bioclimatic chamber under a 16 h/8 h light/dark photoperiod at 25 °C [21]. Germination began approximately four days after sowing.

To assess the effects of VOCs emitted by the 10 PGPR selected, a divided Petri dish system was employed (SYM brand). Each dish contained MS medium supplemented with NaCl at concentrations of 50 and 100 mM to induce salinity stress, alongside a control treatment without NaCl added. On one side of each divided dish were four A. thaliana seedlings that had germinated for four days. The opposite side was inoculated with 10 µL of a bacterial suspension at a concentration of 1 × 109 CFU mL−1; bacteria were previously reactivated as individual strains in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 28–30 °C for 24 h, inoculated into LB liquid culture, and the concentration adjusted. All Petri dishes for the treatments were carefully sealed with sealing film. Dishes without bacterial inoculation were included as a control [21].

The plates were positioned vertically in a growth chamber under a 16 h/8 h light/dark cycle at 25 °C. Twelve days after inoculation with rhizobacteria, the following parameters were recorded: fresh weight of seedlings using an analytical balance, number of lateral roots, and length of primary root measured with digital caliper. Each treatment included 4 replicates with a total of 16 seedlings.

2.3. Biochemical Analysis of A. thaliana

2.3.1. Proline Quantification

Proline extraction was performed following the protocol described by Bates [22]. Plant samples previously exposed to VOCs emitted by rhizobacteria were used. A total of 100 mg of aerial plant tissue was weighed using an analytical balance (Ohaus Pioneer, Model PX224, manufactured in Shanghai, China) and transferred to an Eppendorf tube containing 140 mM sulfosalicylic acid. The tissue was homogenized with a micro pestle, and the resulting solution was filtered through a 0.20 μm membrane. The filtrate was mixed in a 1:1:1 ratio with 140 mM acid ninhydrin and glacial acetic acid, incubated at 100 °C for one hour, and then cooled on ice for 5 min. An equal volume of toluene was added, followed by vigorous vortexing. After standing for 10 min, the organic phase was separated and transferred to a quartz cuvette for spectrophotometric analysis at 520 nm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genesys 20, Model 4001/4, manufactured in Rochester, NY, USA) to quantify the ninhydrin–proline complex. A standard curve was constructed using commercial proline solutions at concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 50, 75, and 100 μg.

2.3.2. Sodium (Na+) Content Determination

Sodium determination was carried out following the methodology of Levinsh [23]. Aerial tissue from A. thaliana seedlings previously exposed to rhizobacterial VOCs was used for sodium quantification. A total of 0.1 g of aerial tissue was weighed, ground into a green paste using a mortar and pestle, and diluted in 50 mL of Milli-Q water in Falcon tubes. Sodium content was measured using a sodium-ion-selective electrode via potential (Horiba, model 1512A, manufactured in Kyoto, Japan). A standard curve was prepared using NaCl and NaOH solutions at concentrations of 0, 3, 7, 30, 60, 120, and 240 mM.

2.3.3. Chlorophyll Content Determination

Chlorophyll content was assessed in four 20-day-old A. thaliana seedlings exposed to VOCs, following the protocol of Zhang and Huang [24]. Total chlorophyll was extracted from leaf tissue using N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and incubated for 24 h at 4 °C in the dark. Chlorophyll A and chlorophyll B concentrations were measured spectrophotometrically at 664 nm and 647 nm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Genesys 20, Model 4001/4), respectively. The concentrations were calculated using the following equations:

Chlorophyll (A) = 12.7 × A664 − 2.79 × A647;

Chlorophyll (B) = 20.7 × A647 − 4.62 × A664;

Total Chlorophyll (A + B) = 17.90 × A647 + 8.08 × A664.

2.4. Identification of VOCs from Rhizobacteria

VOCs released by rhizobacteria were collected from 2-day-old colonies grown on plastic Petri dishes (90 × 15 mm) containing solid MS medium, which were sealed with parafilm. Using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis, volatile compounds were adsorbed using a blue SPME fiber (Polydimethylsiloxane/Divinylbenzene) and desorbed at 180 °C for 30 s into the injector port of a gas chromatograph (Agilent 7890B; Agilent Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA) equipped with a mass spectrometry detector (Agilent 5977A), and data acquisition were performed using the MassHunter Workstation software (2010 version) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA).

A capillary column with a fatty acid phase and a film thickness of 0.25 mm was used. Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The injector temperature was set to 250 °C. The column temperature was initially held at 40 °C for 5 min, then increased at a rate of 3 °C per minute to a final temperature of 220 °C, which was maintained for 5 min. Three independent measurements were performed for each sample. The ion source pressure was 7 Pa, the filament voltage was 70 eV, and the scan rate was 1.9 scans per second.

Volatile compounds were identified by comparing the obtained mass spectra with entries in the NIST/EPA/NIH Mass Spectral Library (2011 version).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A completely randomized design was employed to evaluate the ten PGPR strains and a non-inoculated control under three NaCl concentrations (0, 50, and 100 mM), along with their respective controls without NaCl added to the MS medium. Each treatment included four replicates, resulting in a total of 132 experimental units.

Data from the measured variables were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and treatment means were compared using Tukey’s test at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the SAS software package (Statistical Analysis System Institute, version 9.1). Graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism version 6.

3. Results

3.1. Rhizobacteria Promote A. thaliana Seedling Growth via VOCs

Of the ten rhizobacterial strains tested, three (Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12, Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, and Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12) significantly increased biomass production in A. thaliana seedlings under non-saline conditions through exposure to rhizobacterial volatile organic compounds for 12 days.

Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12 exhibited the largest effect relative to the uninoculated control. Seedlings exposed to its VOCs had an average root length of 51.75 mm and a fresh weight of 68.08 mg, compared to control averages of 40.06 mm and 40.58 mg, respectively (Figure 1a and Figure 2b). In terms of lateral root number, Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 induced an average of 14.63 lateral roots per seedling, significantly more than the uninoculated control’s 8.31 roots (Figure 1a and Figure 2d).

Figure 1.

Effect of rhizobacterial inoculation on primary root length, lateral root number, and fresh weight of A. thaliana seedlings after 12 days of indirect exposure in divided Petri dishes under (a) no salinity, (b) 50 mM NaCl, and (c) 100 mM NaCl. Error bars represent the standard deviation of the mean (n = 4). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between means (p ≤ 0.05).

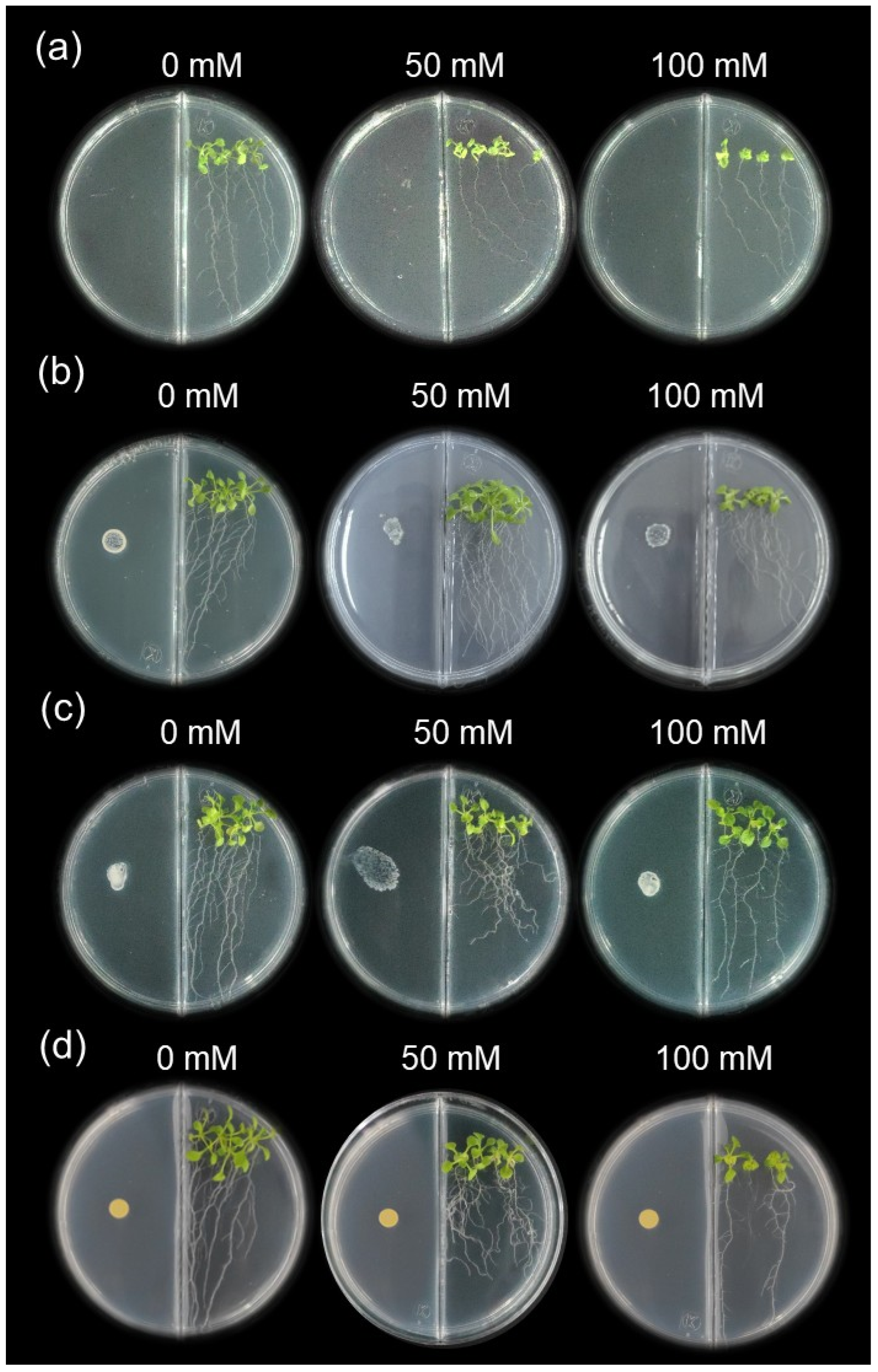

Figure 2.

Effect of rhizobacterial inoculation on growth promotion in A. thaliana seedlings after 12 days of PGPR interactions. Seedlings were grown in divided Petri dishes on MS medium supplemented with 0, 50, or 100 mM NaCl to assess the impact of VOC emissions on growth: (a) uninoculated control; (b) Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12; (c) Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18; (d) Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12.

These results demonstrate the plant-growth-promoting potential of S. colletis CASEcto12, E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, and B. wiedmannii NFbEndo12 rhizobacteria isolated from the rhizosphere of candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica Zucc.) and confirm that their VOCs can stimulate the development of A. thaliana seedlings.

3.2. Effect of Rhizobacterial VOCs on A. thaliana Under Salinity Stress

A. thaliana seedlings grown on MS medium supplemented with 50 mM NaCl and exposed to rhizobacterial VOCs for 12 days exhibited significantly greater growth than the uninoculated control. For root length and fresh weight, S. colletis CASEcto12 yielded the highest values, averaging 64.81 mm and 133.33 mg, respectively, compared to 40.25 mm and 45.05 mg in the uninoculated control (Figure 1b and Figure 2b).

E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 induced the most lateral roots—24 per seedling—and the greatest total fresh weight, averaging 135.78 mg; both were significantly higher than in the uninoculated control with 10 roots per seedling and 45.05 mg of fresh weight (Figure 1b and Figure 2c).

Under 100 mM NaCl, similar trends were observed. Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 achieved an average total fresh of 107.95 mg and 19.06 lateral roots on average, while Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12 promoted the longest primary root length (56 mm). All measured parameters differed significantly from the uninoculated control: 45.05 mg, 10 lateral roots, and 40.25 mm, respectively (Figure 1c and Figure 2c,d).

3.3. Extraction and Measurement of Proline in A. thaliana Plants Under Salinity Stress in Interaction with VOCs

Under non-saline conditions (MS medium without NaCl), no significant differences in proline content from aerial tissue of A. thaliana seedlings were observed among treatments exposed to rhizobacterial VOCs, with values ranging from 0.153 to 0.175 mmol g−1 fresh weight (FW).

In contrast, under salt stress (50 mM and 100 mM NaCl), the aerial tissue of A. thaliana seedlings exposed to Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 VOCs at 12 days post-inoculation accumulated significantly more proline than the uninoculated control. At 50 mM NaCl, the proline content reached 0.657 mmol g−1 FW vs. 0.334 mmol g−1 FW in the control. At 100 mM NaCl, the proline content increased to 1.378 mmol g−1 FW in inoculated seedlings compared to 0.564 mmol g−1 FW in the control (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proline accumulation in A. thaliana aerial tissues under salinity stress conditions of 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl.

3.4. Na+ Concentration in A. thaliana Leaves Under Salinity Stress with VOC Exposure

Under non-saline conditions (MS medium without NaCl), no significant differences in Na+ content were observed among the PGPR treatments. In uninoculated seedlings, sodium accumulation was 0.062 mmol g−1 fresh weight (FW), similar to the values recorded in rhizobacteria-treated seedlings after 12 days (0.056–0.067 mmol g−1 FW).

Under salt stress (50 mM and 100 mM NaCl), Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 significantly reduced Na+ accumulation in aerial seedlings tissues, reaching only 0.074 mmol g−1 FW at 50 mM and 0.084 mmol g−1 FW at 100 mM, compared to the results in the uninoculated control with amounts of 0.102 and 0.146 mmol g−1 FW, respectively. These results indicate that inoculation with Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 effectively mitigated Na+ accumulation in A. thaliana under saline stress (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sodium accumulation (Na+) in aerial tissue A. thaliana seedlings under salinity stress conditions of 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl.

3.5. Chlorophyll Concentration in A. thaliana Leaves Under Salinity Stress with VOC Exposure

Chlorophyll A, chlorophyll B, and total chlorophyll (A + B) were measured in A. thaliana leaves following exposure to rhizobacterial VOCs under 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl.

Under non-saline conditions (0 mM NaCl), Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12 significantly increased chlorophyll A to 32.429 µg mL−1 compared with 30.214 µg mL−1 in the uninoculated control. Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18-inoculated seedlings showed a higher chlorophyll B concentration (33.287 µg mL−1) than the control (23.117 µg mL−1), resulting in a greater total chlorophyll content (60.594 µg mL−1 vs. 53.313 µg mL−1).

At 50 mM NaCl, chlorophyll A did not differ significantly among treatments; the uninoculated control measured 31.495 µg mL−1. In contrast, Staphylococcus epidermidis CASEcto13 treatment increased chlorophyll B to 29.982 µg mL−1 vs. 20.574 µg mL−1 in the control, driving a higher total chlorophyll level (60.349 µg mL−1 vs. 51.069 µg mL−1).

Under high salinity (100 mM NaCl), S. epidermidis CASEcto4 elevated the total chlorophyll to 56.481 µg mL−1 (control: 52.293 µg mL−1). E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 again yielded the highest chlorophyll B, (33.112 µg mL−1; control; 21.215 µg mL−1) and total chlorophyll (62.612 µg mL−1; control: 52.293 µg mL−1). These data confirm the beneficial impact of VOC exposure on chlorophyll retention under salt stress (Table 4).

Table 4.

Chlorophyll A, chlorophyll B, and total chlorophyll content (A + B) in A. thaliana tissues under salinity stress conditions of 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl.

3.6. Identification of VOCs

VOC profiling using SPME-GC-MS was performed on two bacterial strains—Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 and Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12—both of which significantly influenced multiple physiological and biochemical parameters in A. thaliana seedlings, including root length, number of lateral roots, fresh weight, proline content, and sodium accumulation.

Aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols were among the predominant volatile compounds detected in both strains across all tested NaCl concentrations (0, 50, and 100 mM) (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

Volatile organic compounds identified in the Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFBEcto18 in 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl conditions.

Table 6.

Volatile organic compounds identified in Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12 in 0, 50, and 100 mM NaCl conditions.

3.6.1. Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18

VOC emissions from E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 declined markedly with increasing salinity. In the absence of NaCl, the most abundant emitted compound was 1-hexanol, comprising 29.66% of the total VOCs profile. Its relative abundance dropped to 5.09% at 50 mM and to just 1.26% at 100 mM, representing a reduction of over 95% relative to the control. Other compounds that showed substantial decreases included 2-pentadecanol (from 9.23% to 0.24%), 3-tetradecanone (from 7.73% to 0.39%), dimethyl disulfide (from 7.30% to 0.23%), acetophenone (from 6.94% to 0.90%), and 6-methyl-2-heptanol (from 3.52% to 0.94%) (Table 5).

Despite the overall decline, a few compounds were newly detected or slightly increased under saline conditions, albeit in low proportions. For example, 2-pentanamine was absent in the control but appeared at 1.23% in 50 mM and 0.91% in 100 mM. Similarly, 1-octanol and 3-methyl-2-butanol emerged under saline conditions, though neither exceeded 1.05% (Table 5).

3.6.2. Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12

Similarly to E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, exposure to salinity led to a pronounced reduction in VOC emissions from S. colletis CASEcto12. Under non-saline conditions, acetophenone was the predominant compound (53.47%), but its abundance declined to 29.36% at 50 mM and to 8.35% at 100 mM NaCl—an overall reduction of more than 80%. Other compounds with notable decreases included 9-octadecanone (from 13.08% to 2.17%), 3-tetradecanone (from 11.32% to 1.30%), 1-hexanol (from 10.31% to 1.75%), and 6-methyl-2-heptanol (from 6.25% to 0.84%) (Table 6).

Despite the general decline in emissions, several compounds were induced by salinity: 2,3-butanedione, absent in the control, appeared at 2.04% (50 mM) and 1.79% (100 mM). Similarly, 3-methyl-2-butanol emerged at 1.35% at 50 mM, and dimethyl disulfide reached 0.76% under this condition (Table 6).

4. Discussion

The current study advances our understanding of PGPR-mediated salinity stress alleviation by identifying two potent strains—Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12 and Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18—isolated from the rhizosphere of Candelilla (Euphorbia antisyphilitica Zucc.) and characterized as PGPR in the published work of Salazar-Ramirez [19]. Candelilla is an endemic plant of the Chihuahuan desert, adapted to drought, salinity, and high temperatures. The ecological origin of these isolates suggests that they are preadapted to harsh environments, representing a unique resource for developing resilient biostimulants. Our primary finding is that the VOC blends emitted by both strains elicited significant growth promotion in A. thaliana seedlings under both optimal and saline conditions (50 and 100 mM NaCl). Although S. colletis and E. quasihormaechei have been previously reported as PGPR [25,26,27], their VOCs had not been characterized nor had their protective effects against stresses such as salinity been evaluated. This study provides the first report of these properties, positioning these PGPR as promising bioinoculants for mitigating the increasing challenges of soil salinization in agriculture.

The emission of VOCs by rhizobacteria is widely recognized as a key mechanism for promoting plant growth, acting as short- or long-distance signal molecules [16,24,28,29,30]. This study aligns with pioneering evidence from Ryu [28,30], who demonstrated that exposing A. thaliana to VOCs from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens GB03 resulted in an increase of up to fivefold in leaf area. Similarly, Paenibacillus polymyxa E681 has been reported to double leaf biomass in A. thaliana [31]. In our work, the strains S. colletis CASEcto12 and E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 markedly enhanced the primary root length, lateral root number, and fresh weight of A. thaliana seedlings under non-saline conditions (Figure 1a). These results support the hypothesis that bacterial VOCs modulate plant development, potentially through molecular pathways that modulate the expressions of cell division and auxin-related genes.

Beyond growth promotion, VOCs are known to induce tolerance to various abiotic stresses [32]. PGPR can activate diverse physiological and biochemical mechanisms in Arabidopsis seedlings to cope with saline stress. In this study, we observed that A. thaliana seedlings exposed to VOCs from S. colletis CASEcto12, E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, and Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12 showed significantly enhanced development and growth compared with seedlings not exposed to VOCs under salt stress (50 and 100 mM NaCl) (Figure 2). These findings align with Bhattacharyya [33] and Luo [18], who observed that VOCs emitted by Alcaligenes faecalis JBCS1294 and Burkholderia pyrrocinia CNUC9, respectively, improved fresh weight, primary root length, and lateral root number in A. thaliana exposed to 100 mM NaCl.

The root system can uptake water and nutrients from the surroundings; thus, more developed radical systems could improve resistance to various stresses [34,35]. Root development in A. thaliana seedlings was markedly impaired by salinity, as evidenced by reduced primary and lateral root growth in the controls. However, these effects were substantially mitigated by exposure to VOCs from PGPR. VOCs from S. colletis CASEcto12 notably restored primary root elongation and biomass at 50 mM NaCl, while E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 promoted a significant increase in lateral root formation, highlighting strain-specific impacts on root system architecture (Figure 2). Although the precise mechanisms by which these PGPR alter root hormonal networks remain to be elucidated, these findings are consistent with reports that PGPR volatiles influence auxin- and cytokinin-regulated developmental pathways. This suggests that the distinct VOC profiles of these strains differentially modulate hormonal networks to enhance seedling resilience under salt stress [28,36].

Under saline stress, plants undergo physiological and biochemical changes. Proline accumulation is a key indicator of the stress response. One major adaptation to salinity is the accumulation of compatible solutes such as proline, which act as osmoprotectants and antioxidant defense molecules, helping to maintain osmotic balance under salinity stress [18,37,38,39]. PGPR inoculation has been shown to enhance proline accumulation in plants under salt stress [40]. In our study, E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 significantly increased proline levels in A. thaliana seedlings under both 50 and 100 mM NaCl, suggesting VOC-mediated activation of osmotic defense pathways (Table 3). Similar results were reported for Kocuria rhizophila Y1, which increased proline content in maize under salinity stress [41]. Nawaz [3] also demonstrated that consortium inoculation with Pseudomonas fluorescens, Bacillus pumilus, and Exiguobacterium aurantiacum significantly increased free proline content in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under saline stress conditions.

Chlorophyll—the vital green pigment that enables plants to absorb light energy for growth and development—is also affected by salinity. Under saline conditions, chlorophyll content decreases which impairs photosynthesis [42]. Ledger [43] showed that VOCs from Bacillus sp. GB03 and Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN modulate chlorophyll content in A. thaliana, while Taïbi [44] documented progressive chlorophyll and carotenoid loss in Phaseolus vulgaris with increasing salinity. Our results demonstrated that exposure to VOCs from E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 under 100 mM NaCl yielded the highest chlorophyll B and total chlorophyll levels (Table 4). These findings are consistent with Liu [39] and Luo [18], who reported that VOCs from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 and Burkholderia pyrrocinia CNUC9 increased the total chlorophyll in salinity-stressed A. thaliana.

Plants exposed to salt stress experience ion toxicity due to the increased concentration of Na+. Beneficial microbes such as PGPR can alleviate Na+ toxicity in plants through various mechanisms, including restricting uptake, extruding ions from tissues, sequestering them in vacuoles, redirecting Na+ from shoots to roots, and increasing the K+/Na+ ratio [45,46]. For example, in A. thaliana, seedlings exposed to VOCs from Bacillus subtilis GB03 accumulated less Na+ in both roots and shoots [28]. Similarly, inoculation of maize plants with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 lowered Na+ content compared with non-inoculated plants [47]. Liu [39] reported that VOCs from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 significantly decreased Na+ content in A. thaliana and induced the expression of genes such as NHX1 (Na+/H+ exchanger 1) and HKT1 (high-affinity K+ transporter 1) which function to alleviate Na+ toxicity. In the present study, we also found that VOCs emitted by E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 reduced Na+ accumulation in the shoots of A. thaliana seedlings compared with control seedlings under salinity stress that were not exposed to NFbEcto18 VOCs (Table 4). Although this study did not explore the transcriptional regulation of NHX1 and HKT1 in Arabidopsis, these transcripts are likely involved in the observed decrease in Na+ in the aerial parts of plants exposed to PGPR VOCs from NFbEcto18.

SPME-GC-MS profiling of VOCs emitted by E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 and S. colletis CASEcto12 revealed that aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols dominated their spectra (Table 5 and Table 6). Notably, 1-hexanol and acetophenone were the most abundant compounds in the non-saline controls for E. quasihormaechei NFbEcto18 and S. colletis CASEcto12, respectively. Importantly, the abundance of these VOCs decreased markedly when 50 mM NaCl was applied, and this reduction was further accentuated at 100 mM NaCl. However, some VOCs were detected only after NaCl application (50 mM) and even at higher concentrations under greater stress (100 mM). Salinity shifted the VOC profiles, inducing compounds such as methanethiol, 2-pentanamine, 2,3-butanedione, and 2,3-butanediol, which may reflect stress-triggered alterations in bacterial secondary metabolism. VOC production varies greatly with bacterial genotype, growth phase, nutrient availability, oxygen concentration, and inoculum density [48]. Shestivska [49] documented up to 100-fold differences in VOC profiles among 36 Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains grown under similar conditions, underscoring strain-specific emissions. Specific VOCs have been linked to salt tolerance; e.g., Raoultella aquatilis JZ-GX1 emits 2,3-butanediol which reduces Na+ accumulation and boosts antioxidant activity in Robinia pseudoacacia under 100 mM NaCl [17]. Ayuso-Calles [50] observed that salinity triggers the loss of some volatiles and the emergence of others (e.g., acetoin, 3-heptanone) in Rhizobium sp., supporting adaptive modulation of VOC profiles. Reviews of halotolerant PGPR also highlight compounds such as dimethyl disulfide, 2,3-butanediol, acetoin, and tridecane as differentially regulated under saline conditions [51]. The current data regarding VOC biosynthesis pathways are insufficient to elucidate these phenomena. Consequently, a more in-depth investigation into the metabolic processes and genetic regulation governing VOC biosynthesis is imperative, along with the determination of their mechanisms of action on diverse plant species.

5. Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that VOCs emitted by rhizobacteria play a pivotal role in promoting the growth of A. thaliana and enhancing its tolerance to salt stress. Specifically, Siccibacter colletis CASEcto12, Enterobacter quasihormaechei NFbEcto18, and Bacillus wiedmannii NFbEndo12 each significantly increased seedling biomass, root development, and proline accumulation, underscoring their potential as agricultural biostimulants.

Moreover, exposure to these bacterial VOCs significantly reduced sodium accumulation in A. thaliana tissues under saline conditions, suggesting a protective mechanism linked to the modulation of proline metabolism and regulation of ion transport. VOC profiling identified aldehydes, ketones, and alcohols as dominant compound classes, with 1-hexanol, acetophenone, 2,3-Butanedione, and 2-pentanamine emerging as promising candidate bioactives. Although the beneficial effects of VOC-producing PGPR are evident, further research is needed to identify the specific compounds responsible for growth promotion and salinity tolerance and to validate their individual bioactivity through pure-compound assays. Additional steps include elucidating the molecular signaling pathways activated in plants, evaluating VOC stability and diffusion in soil environments, and testing these strains under greenhouse and field conditions, where environmental variability may influence performance. A key challenge is scaling VOC-based technologies to agricultural applications while ensuring consistent activity across different crop species and soil types. Importantly, VOC-emitting PGPR hold strong potential for crops impacted by salinity, such as sugarcane, where salt stress reduces root vigor, sucrose accumulation, and overall yield. Implementing these strains—or their most active VOCs—could enhance root architecture, improve nutrient and water uptake, and strengthen physiological resilience, contributing to more sustainable and productive sugarcane cultivation in saline or marginal lands. Taken together, these findings confirm the dual function of rhizobacterial VOCs as growth-promoting agents and stress-mitigating factors. They position bacterial volatiles as promising biotechnological tools for the development of sustainable agricultural practices in saline and otherwise challenging environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.S.-R. and J.S.-M.; methodology, R.P.-R.; software, J.J.Q.-R.; validation, T.E.V.-C. and G.M.-P.; formal analysis, G.M.-P.; investigation, M.T.S.-R.; resources, H.I.O.-R.; data curation, A.G.Y.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.S.-R., J.J.Q.-R., and J.S.-M.; writing—review and editing, J.S.-M., J.J.Q.-R., and R.P.-R.; visualization, G.A.V.-H.; supervision, J.S.-M.; project administration, J.A.O.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by SECIHTI (Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación) through a doctoral scholarship awarded to María Teresa Salazar Ramírez (number 355051).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Microsoft Copilot (version as of August 2025) for the purposes of language assistance during manuscript preparation, specifically for improving syntax, punctuation, and grammar. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zaman, M.; Shahid, S.A.; Heng, L. Guideline for Salinity Assessment, Mitigation and Adaptation Using Nuclear and Related Techniques; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R. Mapping of Salt-Affected Soils—Technical Manual; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Asadullah; Imran, A.; Marghoob, M.U.; Imtiaz, M.; Mubeen, F. Potential of Salt Tolerant PGPR in Growth and Yield Augmentation of Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Under Saline Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, B.; Wang, X.; Saleem, M.H.; Sumaira; Hafeez, A.; Afridi, M.S.; Khan, S.; Zaib-Un-Nisa; Ullah, I.; Amaral Júnior, A.T.d.; et al. PGPR-Mediated Salt Tolerance in Maize by Modulating Plant Physiology, Antioxidant Defense, Compatible Solutes Accumulation and Bio-Surfactant Producing Genes. Plants 2022, 11, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellari, L.d.R.; Chiappero, J.; Palermo, T.B.; Giordano, W.; Banchio, E. Volatile Organic Compounds from Rhizobacteria Increase the Biosynthesis of Secondary Metabolites and Improve the Antioxidant Status in Mentha piperita L. Grown under Salt Stress. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha-Tran, D.M.; Nguyen, T.T.M.; Hung, S.-H.; Huang, E.; Huang, C.-C. Roles of Plant Growth-promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) in Stimulating Salinity Stress Defense in Plants: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Prasad, P.; Das, S.N.; Kalam, S.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Reddy, M.S.; El Enshasy, H. Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPR) as Green Bioinoculants: Recent Developments, Constraints, and Prospects. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottb, M.; Gigolashvili, T.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Piechulla, B. Trichoderma Volatiles Effecting Arabidopsis: From Inhibition to Protection against Phytopathogenic Fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemfack, M.C.; Gohlke, B.-O.; Toguem, S.M.T.; Preissner, S.; Piechulla, B.; Preissner, R. MVOC 2.0: A Database of Microbial Volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D1261–D1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.A.C.; de Araujo, N.O.; Dias, B.H.S.; de Sant’Anna Freitas, C.; Coerini, L.F.; Ryu, C.-M.; de Castro Oliveira, J.V. The Power of the Smallest: The Inhibitory Activity of Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds against Phytopathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 951130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macías-Rubalcava, M.L.; Sánchez-Fernández, R.E.; Roque-Flores, G.; Lappe-Oliveras, P.; Medina-Romero, Y.M. Volatile Organic Compounds from Hypoxylon anthochroum Endophytic Strains as Postharvest Mycofumigation Alternative for Cherry Tomatoes. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morath, S.U.; Hung, R.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal Volatile Organic Compounds: A Review with Emphasis on Their Biotechnological Potential. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2012, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhou, J.; Tian, R.; Liu, Y. Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds: Antifungal Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 922450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbeva, P.; Weisskopf, L. Airborne medicine—Bacterial volatiles and their influence on plant health: Transley review. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montejano-Ramírez, V.; Ávila-Oviedo, J.L.; Campos-Mendoza, F.J.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Microbial volatile organic compounds: Insights into plant defense. Plants 2024, 13, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-M.; Zhang, H. The effects of bacterial volatile emissions on plant abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.-S.; Kong, W.-L.; Wu, X.-Q.; Zhang, Y. Volatile organic compounds of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria JZ-GX1 enhanced the tolerance of Robinia pseudoacacia to salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 753332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Riu, M.; Ryu, C.-M.; Yu, J.M. Volatile organic compounds emitted by Burkholderia pyrrocinia CNUC9 trigger induced systemic salt tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1050901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Ramírez, M.T.; Sáenz-Mata, J.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Fortis-Hernández, M.; Rueda-Puente, E.O.; Yescas-Coronado, P.; Orozco-Vidal, J.A. Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria associated to candelilla rhizosphere (Euphorbia antisyphilitica) and its effects on Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2021, 49, 12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Meier, F.; Ann Lo, J.; Yuan, W.; Lee Pei Sze, V.; Chung, H.J.; Yuk, H.-G. Overview of recent events in the microbiological safety of sprouts and new intervention technologies: Sprout safety and control. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2013, 12, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bucio, J.; Campos-Cuevas, J.C.; Hernández-Calderón, E.; Velásquez-Becerra, C.; Farías-Rodríguez, R.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.I.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Bacillus megaterium rhizobacteria promote growth and alter root-system architecture through an auxin-and ethylene-independent signaling mechanism in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 207–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievinsh, G.; Meža, S.; Karlsons, A.; Osvalde, A. Validation of ion-selective electrodes for measurement of Na+ and K+ concentration in halophyte tissues. In Proceedings of the 76th Scientific Conference of the University of Latvia, Riga, Latvia, January–April 2018; p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Huang, R. Analysis of Malondialdehyde, Chlorophyll Proline, Soluble Sugar, and Glutathione Content in Arabidopsis seedling. Bio-Protocol 2013, 3, e817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamkhi, I.; Zwanzig, J.; Ibnyasser, A.; Cheto, S.; Geistlinger, J.; Saidi, R.; Ghoulam, C. Siccibacter colletis as a member of the plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria consortium to improve faba-bean growth and alleviate phosphorus deficiency stress. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1134809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, J.T.d.S.S.; Quintanilha-Peixoto, G.; Esteves, B.d.S.; de Souza, S.A.; Lopes, P.S.; da Silva, N.D.; Soares, J.R.; Barroso, L.M.; Suzuki, M.S.; Intorne, A.C. Isolation and Characterization of Plant-Growth-Promoting Bacteria Associated with Salvinia auriculata Aublet. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, S.; Semwal, P.; Pandey, D.D.; Mishra, S.K.; Chauhan, P.S. Siderophore-producing Spinacia oleracea bacterial endophytes enhance nutrient status and vegetative growth under iron-deficit conditions. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 43, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.H.; Reddy, M.S.; Wei, H.X.; Paré, P.W.; Kloepper, J.W. Bacterial volatiles promote growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4927–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Dutta, S.; Ann, M.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Park, K. Promotion of plant growth by Pseudomonas fluorescens strain SS101 via novel volatile organic compounds. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, C.-M.; Farag, M.A.; Hu, C.-H.; Reddy, M.S.; Kloepper, J.W.; Paré, P.W. Bacterial Volatiles Induce Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004, 134, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Farag, M.A.; Park, H.B.; Kloepper, J.W.; Lee, S.H.; Ryu, C.M. Induced Resistance by a Long-Chain Bacterial Volatile: Elicitation of Plant Systemic Defense by a C13 Volatile Produced by Paenibacillus polymyxa. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco-Mosqueda, M.C.; Velázquez-Becerra, C.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.I.; Santoyo, G.; Flores-Cortez, I.; Alfaro-Cuevas, R.; Valencia-Cantero, E. Arthrobacter agilis UMCV2 Induces Iron Acquisition in Medicago truncatula (Strategy I Plant) in Vitro via Dimethylhexadecylamine Emission. Plant Soil. 2013, 362, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.; Yu, S.-M.; Lee, Y.H. Volatile Compounds from Alcaligenes faecalis JBCS1294 Confer Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana through the Auxin and Gibberellin Pathways and Differential Modulation of Gene Expression in Root and Shoot Tissues. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 75, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Na, X.; Yang, L.; Liang, C.; He, L.; Jin, J.; Liu, Z.; Qin, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; et al. Bacillus megaterium strain WW1211 promotes plant growth and lateral root initiation via regulation of auxin biosynthesis and redistribution. Plant Soil. 2021, 466, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shao, J.; Xie, Y.; Jia, L.; Fu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Feng, H.; Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Volatile compounds from beneficial rhizobacteria Bacillus spp. promote periodic lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 1663–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.M.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Ryu, C.M.; Kim, M.K. Bacterial volatile compound 2,3-butanediol enhances salt stress tolerance by regulating auxin and cytokinin balance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verslues, P.E.; Sharma, S. Proline Metabolism and Its Implications for Plant- Environment Interaction. Arab. Book/Am. Soc. Plant Biol. 2010, 8, e0140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Harris, P.J. Potential biochemical indicators of salinity tolerance in plants. Plant Sci. 2004, 166, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Tian, Y.; Jia, M.; Lu, X.; Yue, L.; Zhao, X.; Jin, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, Z.; et al. Induction of Salt Tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana by Volatiles From Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 via the Jasmonic Acid Signaling Pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 562934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R.; Rasul, S.; Aslam, K.; Baber, M.; Shahid, M.; Mubeen, F.; Naqqash, T. Halotolerant PGPR: A hope for cultivation of saline soils. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2019, 31, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sun, P.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, C.; Guan, C. A novel PGPR strain Kocuria rhizophila Y1 enhances salt stress tolerance in maize by regulating phytohormone levels, nutrient acquisition, redox potential, ion homeostasis, photosynthetic capacity and stress-responsive genes expression. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 174, 104023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghafi, K.; Ahmadi, J.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Bakhtiari, S. The effect of microbial inoculants on physiological responses of two wheat cultivars under salt stress. Int. J. Adv. Biol. Biomed. Res. 2013, 1, 421–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ledger, T.; Rojas, S.; Timmermann, T.; Pinedo, I.; Poupin, M.J.; Garrido, T.; Richter, P.; Tamayo, J.; Donoso, R. Volatile-Mediated Effects Predominate in Paraburkholderia phytofirmans Growth Promotion and Salt Stress Tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taïbi, K.; Ait Abderrahim, L.; Boussaid, M.; Bissoli, G.; Taïbi, F.; Achir, M.; Souana, K.; Mulet, J.M. Salt-Tolerance of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Is a Function of the Potentiation Extent of Antioxidant Enzymes and the Expression Profiles of Polyamine Encoding Genes. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 140, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Jia, A.; Xu, G.; Hu, H.; Hu, X.; Hu, L. Jasmonate mediates salt-induced nicotine biosynthesis in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Plant Diver. 2016, 38, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.K.; Singh, J.S.; Singh, D.P. Exopolysaccharide-producing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria under salinity condition. Pedosphere 2011, 21, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, G.; Veronican Njeri, K.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, R. Induced maize salt tolerance by rhizosphere inoculation of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9. Physiol. Plant. 2016, 158, 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Aguilar, M.C.; Espuny Gómez, M.d.R. Compuestos Orgánicos Volátiles (COV) En Las Interacciones Planta-Microorganismo. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Seville, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shestivska, V.; Španěl, P.; Dryahina, K.; Sovová, K.; Smith, D.; Musílek, M.; Nemec, A. Variability in the Concentrations of Volatile Metabolites Emitted by Genotypically Different Strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2012, 113, 701–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso-Calles, M.; Flores-Félix, J.D.; Amaro, F.; García-Estévez, I.; Jiménez-Gómez, A.; de Pinho, P.G.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Rivas, R. Effect of Rhizobium Mechanisms in Improving Tolerance to Saline Stress in Lettuce Plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunita, K.; Mishra, I.; Mishra, J.; Prakash, J.; Arora, N.K. Secondary Metabolites From Halotolerant Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria for Ameliorating Salinity Stress in Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 567768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).