Abstract

Soil biodiversity is crucial for maintaining biological soil resilience, understood as a temporal property and as the ability of soils to uphold or recover their ecological functions under stress thanks to the diversity and complementarity of their biological communities. To evaluate this property, we developed the Biological Soil Resilience Index (BSR), conceived as an evolution of the QBS-ar approach by integrating additional key bioindicators—entomopathogenic nematodes, entomopathogenic fungi, and earthworms—together with microarthropod eco-morphological adaptation scores. This multi-taxon framework provides a more comprehensive assessment of soil biological conditions than single-group indices and is specifically designed to be applied repeatedly over time to detect resilience trajectories. The Biodiversity Soil Resilience (BSR) Index was applied across nine sites subject to low, medium, and high anthropogenic disturbance, spanning urban, industrial, and airport environments. Results revealed not a resilience gradient but a clear disturbance gradient: low-impact sites achieved the highest BSR values (52–59), reflecting diverse and functionally complementary assemblages; medium-impact sites maintained moderate BSR value (27–42), but displayed imbalances among faunal groups; and high-impact sites showed the lowest values, including a critically low score at C_HI (17.86), where entomopathogens were absent and earthworm populations reduced. Entomopathogenic organisms proved particularly sensitive, disappearing entirely under severe disturbance. The BSR was sensitive to environmental gradients and effective in distinguishing ecologically meaningful differences among soil communities. Because it can be repeatedly applied over time, BSR provides the basis for monitoring long-term resilience dynamics, detecting early warning signals, and support timely mitigation or restoration measures. Overall, the study highlights the pivotal role of biodiversity in sustaining soil resilience and supports the BSR Index as a simple yet integrative tool for soil health assessment and for future resilience monitoring in disturbed landscapes.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity encompasses the variety of life on Earth, including the genetic resources essential for the survival, resilience, and long-term stability of populations. It also includes the diversity of ecological interactions among plants, animals, and microorganisms, which underpin ecosystem processes and regulate the balance between structure and function. Among the different components of biodiversity, soil biodiversity represents a unique and fundamental living system that supports the functioning and health of terrestrial ecosystems. Soils host some of the most diverse and functionally relevant organisms on the planet, with belowground diversity exceeding aboveground diversity by several orders of magnitude [1]. Through their activity, soil organisms regulate key ecosystem services such as organic matter decomposition, nutrient cycling, soil formation, improvement of soil structure, pest suppression, and the maintenance of plant productivity. High soil biodiversity is generally associated with increased ecosystem resilience, particularly in agroforestry systems exposed to biotic and abiotic stressors [2,3,4]. Recent research has demonstrated that soil biodiversity plays a central role in sustaining ecosystem multifunctionality, influencing key processes such as decomposition, nutrient cycling, and long-term ecological stability [5]. Yet soil biodiversity is increasingly threatened by a wide range of environmental pressures, including land-use change, reduction in organic matter, soil sealing, habitat fragmentation, extreme climatic events, global warming, drought, fires, pollution, pesticides, and urbanisation. These forms of environmental stress—stemming from both human activities and climate change—can significantly affect ecosystem functioning, soil quality, and the services soils provide. Despite the recognized importance of soil biota, current monitoring tools often focus on single taxonomic groups or narrow functional attributes, limiting their ability to capture the integrated response of soil communities to environmental stress. A clear methodological gap remains: the need for a composite, multi-taxa indicator capable of assessing soil resilience by linking biological quality with the intensity of environmental disturbance. The goal of this study is to address this gap by introducing a novel approach that evaluates soil resilience through the combined analysis of environmental stress factors and multiple biological indicators. In this work, we adopt the QBS-ar protocol for microarthropods and integrate it within a broader multi-taxa framework termed the Biodiversity Soil Resilience (BSR) Index. The BSR index is not intended to replace QBS-ar; rather, it functions as a modular meta-index that expands its scope by incorporating three complementary components of soil biota: microarthropods (QBS-ar), entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi (as proxies for biological control potential), and earthworms, which serve as ecosystem engineers influencing soil structure, hydrology, and biogeochemical cycles [6,7,8,9,10]. Earthworms contribute to nutrient cycling, aggregate stability, water infiltration, plant growth, and carbon storage through litter fragmentation, burrowing, and casting activities [11]. More broadly, soil organisms mediate essential ecosystem functions that affect crop productivity through organic matter breakdown, nutrient availability, soil structural modification, disease suppression, and chemical degradation [12,13]. Contemporary studies highlight the need to incorporate multi-taxa biological indicators when assessing soil functioning, as the ecological response to disturbance often emerges from the interactions among multiple components of the soil biota [14]. By integrating these components, the BSR Index provides an accessible and biologically meaningful tool for assessing soil resilience. It is conceived as a monitoring instrument that can support both the scientific community and governmental authorities in designing sustainable land-use strategies and implementing environmentally effective management actions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of Study Sites and Sampling Phases

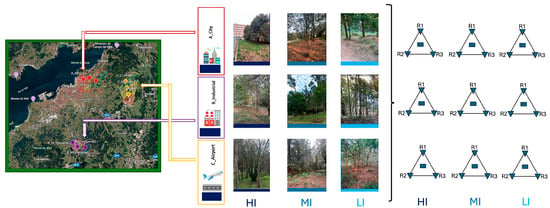

Soil sampling was conducted in three anthropogenically impacted areas—urban area (A), industrial area (B), and airport area (C)—selected in the city of Vigo, Spain. These areas were characterised by different levels of environmental stress: high (HI), medium (MI), and low (LI). To define the levels of environmental stress (HI, MI, LI), the sampling sites were positioned along a spatial disturbance gradient. The high-impact site (HI) was located closest to the main anthropogenic pressure sources—urban areas, industrial areas and airport areas. The medium-impact site (MI) was placed 600 metres further along the same transect, while the low-impact site (LI), located an additional 600 metres away (1.2 km from the HI point), represented an area with minimal anthropogenic influence and served as the ecological reference (control). The three environments examined—an urban area, industrial area and airport area—represent distinct yet ecologically liked forms of disturbance (Figure 1). Each exerting different pressures on soil quality and on the composition of the soil fauna. Urban areas are characterised by chronic, diffuse disturbance arising from soil sealing, compaction caused by vehicular and pedestrian traffic, low organic matter availability and the presence of various micro-pollutants. These conditions typically lead to impoverished soil communities dominated by generalist and stress-tolerant taxa. Industrial zones produce more localised but often intense forms of disturbance, linked to potential chemical contamination, atmospheric emissions, vibrations and microclimatic alterations. Such pressures affect both the soil fauna and the soil microbiome, resulting in the loss of sensitive taxa and a reduction in key ecosystem functions. Airport area constitutes a particularly complex type of disturbance, generated by heavy aircraft and ground-vehicle traffic, continuous noise, vibration, emissions of hydrocarbons and particulate matter, and intensive vegetation management practices. The combined effect of these pressures produces conditions of marked environmental stress, leading to depauperate soil communities and a slowdown of essential processes such as decomposition and nutrient turnover. Taken together, these three settings define a coherent ecological gradient in which disturbance intensity decreases progressively with increasing distance from the primary sources of impact. This gradient is reflected in predictable shifts in soil community structure, in the occurrence of disturbance-sensitive indicator taxa and in the overall capacity of the system to maintain or recover fundamental biological functions. Each area was divided into three distinct sites to ensure an effective comparative analysis. For the analysis of microarthropods, entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs), and entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), three soil samples were collected at each site. These samples were positioned at the vertices of an equilateral triangle, measuring 10 m between them. Each sample was composed of subsamples taken up to a depth of 10–20 cm, following the removal of the surface litter layer. The three subsamples from each vertex were combined into a single composite sample.

Figure 1.

Sampling plan—Territorial classification, division into 3 areas with different anthropogenic impact (city, industrial, airport), with different impact gradients based on distance.

The composite sample was then divided into two parts: one-half was allocated for microarthropod analysis, processed using the Berlese–Tullgren method. The other half was designated for EPNs and EPF analysis, using the “Modified Bait Insect Technique” for the isolation of entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi. Earthworm extraction was performed at the centre of the triangle formed by the three sampling points, using the formalin extraction method followed by manual soil excavation down to a depth of 25 cm. Additionally, for each site, a soil sample was taken from three central subsamples for the analysis of physicochemical parameters, including pH, organic matter content, electrical conductivity, bulk density, and redox potential. During sampling, environmental parameters such as soil temperature, air temperature, and vegetation cover percentage (herbaceous and arboreal) were recorded. All data were collected using a dedicated application and specific field instruments. After labelling, the samples were transported directly to the laboratory, where analyses and extraction procedures commenced within 48 h of collection.

2.2. Analysis of Biological Indicators

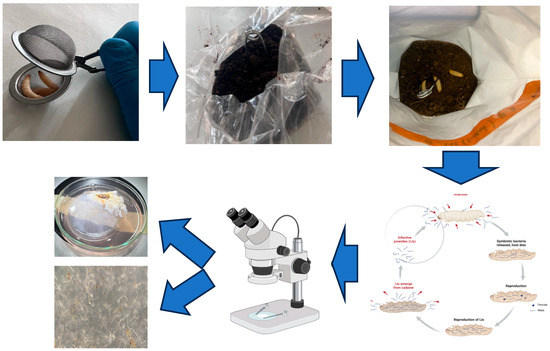

The analysis of soil microarthropods was carried out using the QBS-ar (Soil Biological Quality Index) method, originally developed by Parisi [15] and subsequently refined in later work [6]. This index is based on the concept of biological forms, which reflect the degree of adaptation of microarthropods to life in the soil environment. Microarthropods were extracted from soil samples using the Berlese–Tullgren funnel system. Each sample was exposed to continuous heat for a period of seven days using a 60-watt incandescent bulb placed 20 cm above the sample. The bulbs remained switched on 24 h a day throughout the entire extraction period. A mesh with 2 × 2 mm openings was used to support the soil samples during the extraction process. The specimens collected were preserved in a solution of ethyl alcohol and glycerol at a 3:1 ratio (Figure 2). Identification and counting of the organisms were performed under a stereomicroscope at magnifications ranging from 8× to 50×. The extracted microarthropods were then classified into morphologically homogeneous groups to assess their level of adaptation to subterranean life, as required by the QBS-ar protocol. Entomopathogenic fungi (EPF) and entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) are globally distributed soil-dwelling organisms that play an important role as natural biological control agents against a wide range of insect pests. Both groups are also integral components of soil food webs, contributing to nutrient cycling and ecosystem functioning. Recent studies have demonstrated that the natural presence of EPNs can serve as a bioindicator of the effects of soil management practices [16,17]. The analysis of EPNs and EPF was carried out using the Modified Bait Insect Technique, a method previously employed by members of this research group, as described in the study “Survey on Entomopathogens from the Arasbaran Biosphere Reserve (Iran) with a Modified Bait Insect Technique” [18]. This methodology has proven to be effective and reliable for isolating and identifying soil-dwelling entomopathogens. Soil samples (approximately 500 g each) were collected from the top 10–20 cm of the soil profile using a manual auger, placed in clean plastic bags, and transported to the laboratory in cooled containers to preserve the native soil fauna. Each sample was homogenized and transferred to plastic containers (1–2 L capacity) equipped with aerated lids. For each soil sample a total of 6 Galleria mellonella larvae were released, 3 inside a long-handled tea infuser placed in the middle of the sample to attract the mobile entomopathogens (as the nematodes), and 3 released free on the top of each sample, to search for the static entomopathogens (Figure 2). This technique involves an integration between the techniques that involved either the free release of the larvae in the sample or the containment of the larvae in a perforated container to be inserted into the soil sample [18]. The containers were kept in darkness at room temperature (20–25 °C) and inspected daily for a period of 7–10 days. Infected larvae—identified by characteristic signs such as colour changes (e.g., beige to brown or black in EPN infections, or white mycelial growth in EPF infections)—were carefully removed using sterile forceps and individually placed on White traps to recover infective juvenile nematodes. Nematodes were identified morphologically using light microscopy, and molecular methods were applied when necessary, following the protocol described by Tarasco et al. [18]. It is at this point in the methodology that this baiting technique differs from those previously used: the procedure integrates the two classical approaches, namely the free release of larvae into the soil sample and the containment of larvae inside a perforated container inserted into the sample. The samples were kept at room temperature, and observations were carried out after one week to monitor infected or dead larvae. The symptoms of the cadavers after infection were recorded and used to diagnose infections caused by EPNs and EPF. For the isolation of entomopathogenic nematodes, dead larvae from each sample were transferred to modified White traps and maintained at room temperature (~26 °C). Infective juveniles (IJs) were collected and stored in distilled water at 8 °C. These nematodes were then used to infect fresh Galleria mellonella larvae, and the resulting progeny was used for identification and for establishing laboratory cultures. Measurements were performed on fresh specimens; morphometric identification was based on infective juveniles and male morphology. A molecular analysis was subsequently conducted for the EPN strains.

Figure 2.

Soil sample with 6 Galleria larvae released, 3 inside a long-handled tea infuser and 3 released free on the top of each sample, by Tarasco et al. [17].

This methodology enabled the effective isolation and identification of entomopathogenic nematodes and fungi from soil samples, providing reliable and consistent results that were essential for the calculation of the BSR index.

The extraction and analysis of earthworms were carried out directly in the field using a combination of chemical expulsion and manual hand-sorting, allowing for an accurate assessment of earthworm abundance and diversity. Sampling was performed within a rectangular transect measuring 1 m × 0.5 m (Figure 2). A formalin solution (typically 0.2–0.4%) was poured evenly over the soil surface to stimulate the emergence of earthworms. This method is widely recognised in soil biology for its effectiveness in recovering specimens from the upper soil layers [18]. Earthworms that surfaced in response to the formalin were manually collected using forceps or gloved hands. Following the chemical extraction, the soil within the transect was excavated to a depth of 25 cm. The excavated soil was placed on a plastic sheet and carefully hand-sorted to recover any individuals that had not emerged. Collected earthworms were temporarily stored in labelled containers lined with moist filter paper and transported to the laboratory for identification. In the lab, specimens were gently rinsed with distilled water to remove soil particles and observed under a stereomicroscope or magnifying lamp. The following morphological characteristics were examined: body pigmentation and external colouration, position and shape of the clitellum, setae (chaetae) arrangement, body size and number of segments. Based on these features, earthworms were classified into three ecological categories: Epigeic (EPI): pigmented, small-sized, fast-moving species that live in the litter layer; Endogeic (END): non-pigmented or lightly pigmented, live within the mineral soil horizon, and build horizontal burrows; and Anecic (ANE): large-bodied, pigmented species that create deep vertical burrows and feed at the soil surface.

2.3. Soil Characterisation

Soil characterisation was performed by collecting undisturbed soil cores using the cylinder method, a widely accepted technique for assessing soil physical properties. A 1 mm-thin-walled stainless steel cylinder with a sharpened edge was employed to extract samples with standard dimensions of 5 cm in height and 5 cm in diameter. The cylinder was carefully pressed vertically into the soil until flush with the surface, ensuring minimal disturbance. It was then extracted by gently digging around it to preserve soil structure. Any excess soil was trimmed to align with the cylinder edges before transport to the laboratory. Sampling was conducted in triplicate at each site to account for spatial heterogeneity and improve data reliability. Sites were selected to represent different land-use categories, including urban, industrial, and airport environments, ensuring a broad assessment of soil conditions. Field temperature measurements, including soil and air temperature (°C), were recorded in situ using a calibrated digital thermometer. Vegetation cover was visually assessed and categorized into arboreal and herbaceous cover (%), providing insight into site-specific vegetation structure. In the laboratory, the collected samples were immediately weighed to determine the wet weight (g). The samples were then oven-dried at 105 °C to constant weight, after which the dry weight (g) was recorded. Soil water content (%) was computed as the difference between wet and dry weight, expressed as a percentage of the dry weight. Bulk density (g/cm3) was calculated as the ratio of dry weight to sample volume, providing a measure of soil compaction. Porosity (%) was estimated using the relationship between bulk density and an assumed particle density of 2.65 g/cm3 (Table S1; Figure S1). This parameter is critical in evaluating soil structure and its ability to retain water and air. All laboratory analyses were performed under controlled environmental conditions to ensure accuracy and repeatability. Quality control measures included duplicate measurements, periodic calibration of laboratory instruments, and adherence to standard soil analysis protocols. The collected data were subsequently subjected to statistical analyses, including descriptive statistics, correlation analyses, and hypothesis testing, to assess variations in soil properties across different land-use types.

2.4. BSR Index Calculation

The BSR Index is an international tool developed to evaluate the resilience and functional integrity of soils across a wide range of ecosystems, including forests, agricultural lands, and agroforestry systems, in response to various forms of environmental stress [19]. This index is based on the analysis of four key biological indicators: microarthropods, entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs), entomopathogenic fungi (EPF), and earthworms. (Figure 3). These groups were selected because of their ecological relevance, sensitivity to disturbance, and central role in key soil processes. At the core of the BSR Index lies the QBS-ar index (Soil Biological Quality based on Arthropods), which assesses the presence and diversity of soil microarthropods—a group of tiny invertebrates that inhabit the soil and litter layers. The QBS-ar is based on the concept that soil-dwelling organisms develop specific morphological and physiological adaptations to their underground life. Each taxon is assigned an Edaphic Adaptation Score (EMI), which reflects the degree to which it is adapted to soil life [6]. Organisms that dwell primarily on the surface show little to no adaptations and receive low EMIs, while those that inhabit deeper soil layers tend to exhibit strong morphological changes, such as depigmentation, eye reduction or loss, elongated body shapes, and reduced mobility. These features are associated with higher EMIs. Thus, a soil community dominated by highly adapted taxa—reflected in higher QBS-ar values—is interpreted as more resilient and ecologically stable, indicating a biologically rich and well-structured soil [6,20]. Each group is assigned an Ecomorphological Index (EMI) value, which varies from 1 to 20, depending on the level of soil adaptation. The sum of the EMIs assigned to each group gives the value of the QBS-ar index. The value obtained from the QBS-ar will subsequently be incorporated into the calculation of the BSR index. The resilience index represents an evolution of the QBS; while the QBS primarily indicates soil quality, the BSR provides insights into soil resilience following environmental stress. The overall score reflects the number and variety of earthworms found in the soil, providing further insight into the quality of the underground ecosystem. The BSR Index is calculated as an integrated measure of soil biological resilience, based on three complementary faunal components: soil microarthropods, entomopathogens (nematodes and fungi), and earthworms. Soil microarthropods are extracted using Berlese–Tullgren funnels, grouped into morphologically homogeneous units, and assessed according to the QBS-ar protocol, with the assignment of an Edaphic Morphological Index (EMI, 1–20) proportional to their degree of adaptation to soil life. The sum of EMI values provides the raw QBS-ar score (AR_raw, range 0–353). The presence of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPN: Steinernema, Heterorhabditis) and entomopathogenic fungi (EPF: Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae) is determined using a modified insect-bait technique with Galleria mellonella larvae. A presence-based site score (EP_raw, range 0–20) is then assigned: 20 for the joint detection of both EPN and EPF, 10 for only one group, and 0 when absent. Hand-sorting soil monoliths and timed searches sample earthworms. Individuals are classified into Epigeic (EPI), Endogeic (END), and Anecic (ANE) forms. The presence-and-form score (EW_raw) is assigned according to the highest-value form detected at the site, without summing contributions: EPI = 5, END = 10, ANE = 20 (range 0–35). This criterion captures the functional depth stratification of the earthworm community based on the maximum depth reached (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Workflow for the extraction of ecological indicators (microarthropods, entomopathogens, and earthworms).

Table 1.

Scoring system adopted for the BSR Index.

To allow comparability among components, raw scores are normalised to a 0–100 scale using max-scaling (1):

AR_norm = 100 × AR_raw/353; EP_norm = 100 × EP_raw/20; EW_norm = 100 × EW_raw/35

The overall BSR Index (2) is calculated as a weighted mean of the three normalised components, with greater weight assigned to the microarthropod signal:

BSR Index = 0.40 × AR_norm + 0.30 × EP_norm + 0.30 × EW_norm

Final values (0–100) are assigned to four resilience classes: Class 4 (excellent, ≥75), Class 3 (good, 50.00–74.99), Class 2 (moderate, 25.00–49.99), and Class 1 (low, <25). (Table 2) All criteria related to sampling, extraction, scoring, normalisation, and thresholds are kept constant across sites and ecosystem types to ensure repeatability and comparability. The calculation of the resilience index allows for the classification of sites into four distinct resilience classes, each offering a clear interpretative framework for supporting land management decisions. These classes reflect the capacity of the soil ecosystem to maintain or recover its functionality in response to environmental pressures or anthropogenic disturbances. Sites falling within Classes 1 and 2 are considered critical or highly vulnerable areas. These locations exhibit reduced biological activity, low diversity of functional soil organisms (such as earthworms or microarthropods), and diminished ecological resilience. As such, they are identified as priority zones for restoration and mitigation interventions, aimed at restoring soil functions, enhancing biodiversity, and reestablishing ecological balance. This index provides a standardised measure of soil biological resilience, making it a valuable tool for assessing the impacts of environmental stress across various ecosystems.

Table 2.

Resilience classes are defined according to the BSR Index values.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Variation in Soil Physical Properties Along an Impact Gradient

The analysed sites, city (A), industrial (B), and airport (C) and showed clear differences in microclimatic conditions and vegetation cover. Soil temperature varied moderately (15.6–18 °C), while air temperature reached a maximum of 27.3 °C at the C_LI (airport) site, characterised by high arboreal cover (81–100%) and low herbaceous cover (1–20%). Sites with denser vegetation exhibited more buffered soil temperatures and thicker organic layers (e.g., A_LI, City), whereas industrial and airport sites with sparse vegetation had much thinner organic layers (1.5–2 cm), suggesting a direct role of vegetation in soil thermal regulation and organic matter accumulation. Soil physical properties differed significantly depending on anthropogenic impact intensity (HI = High, MI = Medium, LI = Low). Volumetric water content (% H2O vol.) was significantly higher in HI sites compared to MI and LI (p = 0.0028; with post hoc Tukey HSD tests confirming significant differences between HI-MI and HI-LI, but not between MI-LI, suggesting a threshold response to compaction. Gravimetric water content (% H2O/dry weight) followed a similar trend, though marginally significant (p = 0.0651). Bulk density was significantly higher in HI sites (p = 0.0386); therefore, the porosity is substantially lower (with maximum porosity observed in LI sites, particularly airport–LI (>80%), indicating a more stable and aerated soil structure. Although not statistically significant, organic horizon thickness tended to be greater in LI sites, particularly in semi-natural environments, and was associated with higher porosity, confirming the functional role of organic matter in enhancing aggregate stability and water retention. These results are consistent with previous findings highlighting how anthropogenic pressure alters soil physical properties, reducing ecological functionality and the capacity of urban soils to support green infrastructure and hydrological regulation.

3.2. Microarthropods

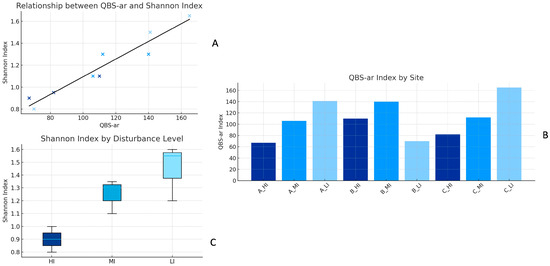

The analysis of microarthropod biodiversity revealed a clear distinction among sites along a gradient of anthropogenic impact. Low-impact (LI) sites exhibited a significantly higher Shannon diversity index compared to high-impact (HI) sites, confirming greater species and functional diversity in the former. The Shannon diversity index (H′) was calculated to describe the diversity of the soil microarthropod community; the index was computed using the standard formula , where represents the proportional abundance of each taxonomic group. Similarly, values of the QBS-ar index, which reflects the presence of biological forms highly adapted to soil life, were highest in LI sites (up to 165) and lowest in HI sites (67), with statistically significant differences (F = 6.65; p = 0.02). These findings suggest that anthropogenic pressures—such as urbanisation, pollution, traffic, and reduced vegetation covers substantially reduce the complexity of soil fauna communities. Soil microarthropods have been shown to respond sensitively to land management practices and to be correlated with beneficial soil functions [6]. The collection, analysis, and categorisation of soil microarthropods have proven to be an inexpensive and easily quantifiable method of gathering information about the biological response to anthropogenic changes in the environment [21]. Several studies have confirmed that the QBS-ar index is an effective tool for evaluating the ecological status of soils in both natural and disturbed environments [20] and is particularly useful in the context of urban and agricultural biomonitoring [22]. Furthermore, the decline in microarthropod biodiversity in disturbed areas has been linked to a loss of key soil ecological functions, including organic matter decomposition and moisture regulation [23]. The QBS-ar values recorded across the nine sampling sites varied consistently with disturbance intensity and land-use categories. The highest scores were found in low-disturbance sites, namely C_LI (165), A_LI (141), and B_MI (140), while intermediate values appeared at C_MI (112), B_HI (110), and A_MI (106). The lowest values were recorded at A_HI (67) and B_LI (70). A strong positive correlation was observed between the QBS-ar index and the Shannon diversity index, which reflects the taxonomic richness and evenness of the microarthropod community. Shannon values were consistently higher in low-disturbance (LI) sites and lower in high-disturbance (HI) sites, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of r = 0.98 (p < 0.001) between the two indices. This trend is illustrated in Figure 4A, showing the linear relationship between the indices across all sites. Figure 4B displays the distribution of QBS-ar scores by site, with higher values under low-disturbance conditions. Figure 4C presents Shannon diversity according to impact level, emphasizing higher medians and less variability in LI sites. An exception was observed at site B_LI, where both indices unexpectedly showed low value despite its classification as low disturbance. This anomaly is probably related to recent reforestation with chestnut (Castanea sativa Mill.) and proximity to a heavily trafficked road, factors that may have caused localised disturbances not reflected in the overall land-use classification.

Figure 4.

(A) Correlation between QBS-ar and Shannon Index; (B) Variation in QBS-ar index; (C) Variation in QBS-ar Index Across Sites and impact levels Shannon Index by impact level.

3.3. Entomopathogenic Nematodes (EPNs) and Entomopathogenic Fungi (EPF)

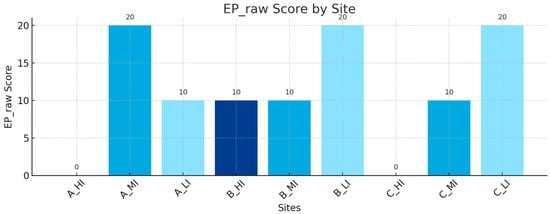

The analysis of the entomopathogenic component of the BSR Index (BSR EP) revealed marked differences in the occurrence of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) and fungi (EPF) across the nine sampled sites, each subjected to different levels of anthropogenic disturbance. Site scores (EP_raw, range 0–20) were defined as 20 when both groups (EPNs and EPF) were detected, 10 when only one group was present, and 0 when neither was recorded. Maximum scores (20) were obtained in C_LI (airport, low impact), A_MI (intermediate urban zone, medium impact), and B_LI (low impact), where both EPNs and EPF were consistently detected. Intermediate values (10) were observed in A_LI, B_HI, B_MI, and C_MI, reflecting partial presence and greater spatial variability. In high-impact sites, scores were notably reduced: C_HI (airport, high impact) and A_HI (central urban zone, high impact) recorded absence (0) and isolated detection (10), respectively (Figure 5).Overall, a clear negative gradient emerged between anthropogenic disturbance and the occurrence of entomopathogens. Low- and medium-impact sites supported a higher probability of harbouring EPNs and EPF, whereas high-impact sites were impoverished or devoid of these biological control agents. This trend is consistent with previous studies showing that environmental stressors such as soil compaction, contamination, and reduced organic matter negatively affect the survival and infectivity of entomopathogenic organisms [15,24,25]. Within this framework, the maximum score recorded at site A_MI is of particular interest: located in an intermediate zone immediately outside the densest urban matrix, and functioning as a public park, it appears to benefit from vegetation cover and soil conditions that mitigate the pressures typically associated with the surrounding urban environment.

Figure 5.

Entomopathogen component scores (BSR EP) contributing to the BSR Index across sampling sites. Values (0–20) represent the cumulative presence of entomopathogenic nematodes (EPNs) and fungi (EPF) based on three replicates for site.

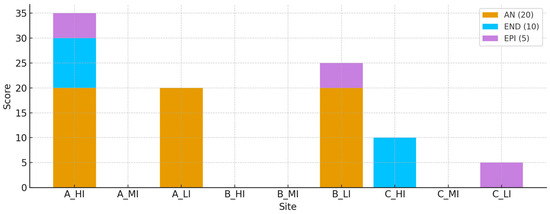

3.4. Earthworm

The earthworm component of the BSR Index (BSR EW) demonstrated substantial spatial variability across the sampled sites, reflecting the influence of anthropogenic disturbance on soil macrofauna. Earthworms were categorised into three ecological groups—anecic (AN), endogeic (END), and epigeic (EPI)—based on their ecological strategies and vertical distribution in the soil profile. The BSR EW score was calculated using a weighted presence system (AN = 20 points, END = 10, EPI = 5), with a maximum possible score of 35 per site. The highest BSR EW value was recorded in A_HI (urban, high impact), with a total of 35 points, corresponding to the presence of all three ecological groups: Lumbricus rubellus (anecic, 16 individuals), L. friendi (endogeic), Aporrectodea caliginosa (endogeic, 18 individuals), and Dendrobaena octaedra (epigeic, 15 individuals). This site was the only one exhibiting a complete and abundant earthworm community across all functional categories. Moderate BSR EW values were recorded in A_LI (20), B_LI (25), C_HI (10), and C_LI (5). In A_LI, the presence of L. friendi (endogeic) was noted, while B_LI supported a more diverse community including L. rubellus (AN), L. friendi (END), Eisenia eiseni (END), and D. octaedra (EPI), resulting in a relatively high BSR EW score. By contrast, C_HI contained only endogeic individuals (A. caliginosa, 2 individuals), and C_LI was represented by a single epigeic species (D. octaedra). No earthworms were detected in A_MI, B_HI, B_MI, or C_MI, all of which scored zero, indicating poor macrofaunal colonisation and potentially unfavourable soil conditions (e.g., compaction, low organic matter). Unexpectedly, the urban high-impact site A_HI displayed the most complete and functionally diverse earthworm assemblage (Figure 6). This pattern is likely related to the artificial nature of the site, corresponding to a managed public park with enriched and fertilised soil and additional water inputs from surrounding paved areas. As such, A_HI highlights how well-managed green spaces in dense urban contexts can sustain high levels of soil biodiversity. In this study, we interpreted urban green space as intra-urban areas situated among buildings and exposed to characteristic city pressures. Within this context, the high earthworm score at A_HI reflected elevated organic-matter availability and favorable microclimatic conditions, consistent with resilience to urban stress mediated by key ecosystem functions (improved soil structure, enhanced infiltration, and reinforced biogeochemical cycling). Rather than representing a managerial artifact, this signal indicated that mitigation measures (litter inputs and management, vegetative cover, judicious irrigation) translated into measurable functional benefits for urban soils. We therefore considered A_HI as evidence that the BSR captured the capacity of the park–soil system to buffer typical urban stressors, and we argued that increasing the extent and connectivity of urban green spaces could amplify these benefits at the landscape scale.

Figure 6.

Distribution of earthworm functional groups (AN = anecic, END = endogeic, EPI = epigeic) across experimental sites.

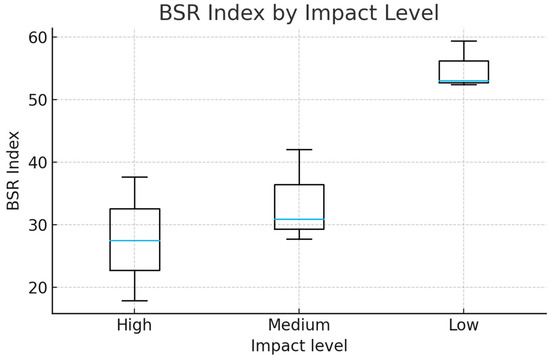

3.5. BSR Index and Resilience Classification

The BSR Index (0–100) showed clear variability among sites exposed to different levels of stress and impact, determined by differences in the communities of arthropods (AR), entomopathogens (EP), and earthworms (EW) (Table 3; Figure 7). Class 1 (low resilience) occurred exclusively at site C_HI (BSR = 17.86), where high stress corresponded to low arthropod abundance, absence of entomopathogens, and reduced earthworm presence, indicating severe functional loss. Class 2 (moderate resilience) was the most common condition, encompassing sites A_HI, A_MI, B_HI, B_MI, and C_MI, with values ranging between 27 and 42. These soils maintained partial functionality but displayed imbalances among faunal groups, consistent with patterns reported for communities subjected to moderate disturbance. Class 3 (high resilience) was recorded in A_LI, B_LI, and C_LI (BSR = 52–59), where reduced impact supported greater coexistence of arthropods, entomopathogens, and earthworms, reflecting the role of soil biodiversity in sustaining ecosystem stability [26]. Comparative trends among site groups were distinct: in group A, resilience increased progressively from high to low impact; in group B, resilience remained moderate under stress but increased sharply under reduced impact; and in group C, it ranged from critically low (C_HI) to moderate (C_MI) and finally high (C_LI), illustrating a broad spectrum of responses. Overall, lower stress and impact were consistently aligned with higher BSR values, underscoring the sensitivity of soil faunal associations to disturbance gradients. To statistically evaluate these patterns, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to assess whether BSR values differed significantly among the three impact levels (High, Medium, Low). The analysis revealed a significant effect of impact level on the BSR index (F = 10.99, p = 0.0099), indicating that the groups are not statistically homogeneous. A clear gradient emerged, with the lowest BSR values occurring at High-impact sites and the highest values at Low-impact sites. This trend is visually represented in the boxplot (Figure 8)., which shows a distinct separation in the distribution of BSR values across the three categories. These findings confirm that the BSR index is responsive to the intensity of environmental impact and effectively captures differences in soil resilience along the disturbance gradient.

Table 3.

BSR Index values and resilience classes across nine sampling sites, showing higher resilience inow-disturbance (LI) sites and lowest scores under high-disturbance conditions.

Figure 7.

Biodiversity Soil Resilience Index (BSR) values and resilience classes across the nine sampling sites.

Figure 8.

Variation In the BSR Index Across Impact Levels (High, Medium, Low).

The interpretation of the BSR index must acknowledge that ecological resilience is an inherently dynamic property, manifesting over time rather than at a single point of measurement. Although the spatial gradient examined in this study provides an initial indication of the index’s sensitivity to differing levels of disturbance, the real utility of the BSR lies in its application within long-term monitoring frameworks. Repeated assessments over successive years would enable the quantification of both the direction and the rate of ecological recovery or degradation, thereby offering insight into how rapidly—and to what extent—soil biological structure and functional integrity are restored following disturbance. Consequently, the BSR should be regarded not merely as a diagnostic tool for comparing sites at a given moment, but as an indicator capable of tracing temporal trajectories of resilience and the overall condition of soil ecosystems. This study provides the first application of the Biodiversity Soil Resilience (BSR) Index across a gradient of anthropogenic disturbance. The results show that the index is sensitive to environmental pressure, with lower BSR values recorded in highly disturbed areas and higher values in sites with minimal human impact (Table 3; Figure 8). This pattern reflects well-established ecological expectations regarding the response of soil communities to increasing distance from disturbance sources. It is important to note that the BSR is not intended to quantify ecological resilience from a single sampling event. Resilience is inherently a temporal property, emerging from the speed and direction of recovery following disturbance. For this reason, the strength of the BSR lies in its application within long-term monitoring programmes. Repeated measurements over multiple years will allow the assessment of whether a soil system is recovering, stabilising, or continuing to degrade, thus supporting informed management decisions. The structure of the BSR integrates three complementary components—microarthropod adaptation (QBS-ar), presence of entomopathogens (EPNs + EPF), and earthworm ecological categories—capturing different facets of soil biological functioning. The anomalous low QBS-ar value observed at the B_LI site highlights the sensitivity of microarthropod communities to local or recent disturbances and reinforces the need for repeated measurements to distinguish transient fluctuations from long-term trends. While the study is limited by its small spatial scale and single sampling event, it provides a solid framework for future applications of the BSR and demonstrates its potential as a multi-taxa indicator of soil condition.

4. Conclusions

This study represents the first application of the Biodiversity Soil Resilience Index (BSR), demonstrating its robustness and ecological relevance for assessing soil biodiversity and resilience across gradients of anthropogenic disturbance. By integrating soil microarthropods, entomopathogenic organisms, and earthworms, the BSR captures complementary functional dimensions of soil biota, providing a more comprehensive signal than single-indicator approaches. Results showed that highly disturbed sites (e.g., industrial and airport areas) were consistently associated with lower resilience classes, while low- and medium-impact sites supported richer and more functionally diverse communities. The consistent association between higher BSR values and reduced disturbance confirms the sensitivity of the index to environmental gradients. Moreover, the resilience class framework provides a practical tool not only for long-term monitoring and cross-site comparisons, but also for detecting potential seasonal variations. This capacity makes it possible to track changes in soil resilience over time, identify priority areas for restoration, and evaluate the effectiveness of management interventions. Overall, the BSR emerges as a simple, integrative, and operationally effective methodology for soil health monitoring, particularly suited to urban and industrial landscapes under strong anthropogenic pressure. The BSR Index proved effective in distinguishing soil biological conditions along a disturbance gradient and represents a practical, multi-taxa approach for soil assessment. Although it does not measure resilience directly at a single point in time, the index offers a useful tool for evaluating resilience trajectories when applied over multiple years. Expanding the number of sites, integrating functional soil measurements, and establishing long-term monitoring will be essential to fully validate the BSR as a resilience indicator. Overall, the BSR has the potential to support soil biodiversity conservation and improve decision-making in ecosystem management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/soilsystems9040134/s1, Table S1: Soil physical parameters measured across urban, industrial, and airport sites, including temperature, vegetation cover, sample weights, bulk density, and porosity [27,28,29]. Figure S1: Variation of key soil physical and hydrological properties across impact levels (HI = High Impact, MI = Medium Impact, LI = Low Impact), grouped by land-use category (City = A, Industrial = B, Airport = C).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.M.A. and E.T.; methodology, G.M.A., E.T., G.B., V.S., J.G., S.M. and B.S.; investigation, G.M.A., E.T., G.B., V.S., J.G., S.M. and B.S.; resources, G.M.A., E.T. and G.B.; data curation, G.M.A., B.S., V.S. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M., J.G., E.T., G.B. and V.S.; visualization, E.T., J.G. and S.M.; supervision, E.T.; project administration, G.M.A. and E.T.; funding acquisition, E.T., G.M.A. and G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministerial Decree no. 351 of 9 April 2022, based on the PNRR-funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU-I.4.1 General PhD Research Scholarships funded under the NRRP. This research was funded by Convention Bio-Care UPB: BIO-CARE LAMA BALICE, funded by Parco Naturale Regionale “Lama Balice”-Città Metropolitana di Bari.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the Corresponding Author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EPNs | Entomopathogenic nematodes |

| EPF | Entomopathogenic Fungi |

| EW | Earthworms |

| BSR | Biodiversity Soil Resilience |

| QBS | Soil Biological Quality |

References

- Heywood, V.H. Global Biodiversity Assessment; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J.E. Why biodiversity is important to the functioning of real-world ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loreau, M. Linking biodiversity and ecosystems: Towards a unifying ecological theory. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Eldridge, D.J.; Liu, Y.R.; Liu, Z.W.; Coleine, C.; Trivedi, P. Soil biodiversity and function under global change. PLoS Biol. 2025, 23, e3003093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bongers, T.; Ferris, H. Nematode community structure as a bioindicator in environmental monitoring. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1999, 14, 224–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, V.; Menta, C.; Gardi, C.; Jacomini, C.; Mozzanica, E. Microarthropod communities as a tool to assess soil quality and biodiversity: A new approach in Italy. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byers, J.E.; Cuddington, K.; Jones, C.G.; Talley, T.S.; Hastings, A.; Lambrinos, J.G.; Crooks, J.A.; Wilson, W.G. Using ecosystem engineers to restore ecological systems. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2006, 21, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, N. The action of an animal ecosystem engineer: Identification of the main mechanisms of earthworm impacts on soil microarthropods. Pedobiologia 2010, 53, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, L.; Chapuis-Lardy, L.; Razafimbelo, T.; Razafindrakoto, P.A.L.; Legname, E.; Poulain, J.; Brüls, T.; Donohue, M.O.; Brauman, A.; Chotte, J.L.; et al. Endogeic earthworms shape bacterial functional communities and affect organic matter mineralization in a tropical soil. ISME J. 2012, 6, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, M.; Hodson, M.E.; Delgado, E.A.; Baker, G.; Brussard, L.; Butt, K.R.; Dai, J.; Dendooven, L.; Peres, G.; Tondoh, J.E.; et al. A review of earthworm impact on soil function and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 161–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, D.C.; Crossley, D.A.; Hendrix, P.F. Fundamentals of Soil Ecology, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, C.A.; MacDonald, K.B. Challenges related to soil biodiversity research in agroecosystems—Issues within the context of scale of observation. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2003, 83, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestre, F.T.; Biancari, L.; Chen, N.; Corrochano-Monsalve, M.; Jenerette, G.D.; Nelson, C.; Shilula, K.N.; Shpilkina, Y. Research needs on the biodiversity–ecosystem functioning relationship in drylands. Npj Biodivers. 2024, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.C.; Gewin, V.L. Soil microbial diversity: Present and future considerations. Soil Sci. 1997, 162, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi, V. La qualità biologica del suolo: Un metodo basato sui microartropodi. Acta Nat. De L’Ateneo Parm. 2001, 37, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Herrera, R.; El-Borai, F.E.; Duncan, L.W. Modifying soil to enhance biological control of belowground dwelling insects in citrus groves under organic agriculture in Florida. Biol. Control 2015, 84, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Pérez, R.; Bueno-Pallero, F.Á.; Vicente-Díez, I.; Campos-Herrera, R. Soil management impact on entomopathogenic nematodes: Relevance to conservation biological control. Biol. Control 2020, 151, 104381. [Google Scholar]

- Tarasco, E.; Kary, N.E.; Fanelli, E.; Mohammadi, D.; Xingyue, L.; Mehrvar, A.; Troccoli, A. Modified bait insect technique in entomopathogens’ survey from the Arasbaran Biosphere Reserve (Iran). Redia 2020, 103, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Ingram, J.S.I. Tropical Soil Biology and Fertility: A Handbook of Methods, 2nd ed.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, G.M.; Garrido, J.; Moino Junior, A.; Tkaczuk, C.A.; Santarcangelo, V.; Bari, G.; Mato, S.; Tarasco, E. Biodiversity Soil Resilience (BSR): A new Index to assess resilience in environmentally stressed ecosystems by including entomopathogenic nematodes. In Proceedings of the 35th International Symposium of the European Society of Nematologists, Cordoba, Spain, 15–19 April 2024; pp. 119–120. [Google Scholar]

- Menta, C. Soil fauna diversity—Function, soil degradation, biological indices, soil restoration. In Biodiversity Conservation and Utilization in a Diverse World; Abdul-Rahman, A.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 59–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, N.R.; Peterson, J.A.; Gilley, J.E.; Schott, L.R.; Schmidt, A.M. Soil arthropod abundance and diversity following land application of swine slurry. Agric. Sci. 2019, 10, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardi, C.; Menta, C.; Tarocco, L.; Parisi, V. Biodiversity indices for soil quality evaluation: The QBS-ar approach. Ecol. Indic. 2009, 9, 418–428. [Google Scholar]

- Lavelle, P.; Decaëns, T.; Aubert, M.; Barot, S.; Blouin, M.; Bureau, F.; Margerie, P.; Mora, P.; Rossi, J.P. Soil invertebrates and ecosystem services. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2006, 42, S3–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppenhöfer, A.M.; Fuzy, E.M. Soil management and entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Nematol. 2008, 40, 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y. Soil characteristics and management in an urban park in Hong Kong. Environ. Manag. 1998, 22, 683–695. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s002679900139 (accessed on 16 August 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Carbon Sequestration in Forest Ecosystems; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharenbroch, B.C.; Lloyd, J.E.; Johnson-Maynard, J.L. Distinguishing urban soils with physical, chemical, and biological properties. Pedobiologia 2005, 49, 283–296. Available online: https://treefund.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/scharenbroch_etal_2005_pedobiologia.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).