Abstract

In flooded soils, the concentrations of exchangeable Mn2+ and, especially, Fe2+ can be high and must be considered when determining the cation exchange capacity (CEC) of the soil under flooded conditions. However, these reduced forms of Mn and Fe are oxidized and precipitated during the extraction process used in traditional CEC methods. This procedure underestimates the exchangeable portion of these cations and, consequently, the CEC value of the flooded soil. We introduce a pH-gradient-based model to predict ECEC and exchangeable Fe2+ in flooded soils, circumventing oxidation artifacts inherent in conventional methods. The objective of this study is to propose an alternative to estimate the exchangeable Fe2+ and the effective CEC (ECEC) of flooded soils. To achieve this goal, 21 surface samples (0–20 cm) of soil from rice fields were collected and distributed in the cultivation regions of southern Brazil. The soils were flooded for 50 days. The soil solution was collected on the first day and after 50 days of flooding and pH, Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe and Mn were determined. In these samples, exchangeable cations (K, Na, Ca, Mg, Mn, Al and H + Al) were determined to calculate ECEC and CEC at pH 7 of unflooded soil and after 50 days of flooding. There was a wide range of variation in the exchangeable cation contents among the soil samples. The K contents ranged from 0.12 to 0.54 cmolc kg−1, the Na contents from 0.00 to 1.18 cmolc kg−1, the Ca contents from 0.48 to 37.31 cmolc kg−1, the Mg contents from 0.10 to 15.53 cmolc kg−1, the Mn contents from 0.01 to 0.36 cmolc kg−1, the Al contents from 0.10 to 1.74 cmolc kg−1 and the H + Al contents from 2.01 to 8.42 cmolc kg−1. The results were used to develop models to predict ECEC and exchangeable Fe content after 50 days of flooding. Estimating the ECEC after flooding using the pH gradient before and after flooding yielded values closer to CEC pH 7.0, correcting for the possible underestimation of the ECEC during flooding. The amount of exchangeable Fe estimated was higher than the exchangeable Fe determined, correcting the possible underestimation of these quantities determined during flooding. It is concluded that the estimations of ECEC after flooding through the equation , where pHsol.before is pre-flooding soil pH, pHsol.after is after flooding pH, ECECafter is effective CEC after flooding and the exchangeable Fe2+ after flooding through the equation where Feexc.after.estimated is estimated exchangeable Fe2+ after flooding corrected the problem of underestimating the values of these variables by analytical methods, demonstrating its viability for use in flood-prone soils.

1. Introduction

Rice cultivation in Brazil is characterized by the flood irrigation system [1,2]. Under these conditions, a series of physical, chemical, and biological transformations occurs in the soil [3], leading to a shift from an aerobic (oxidized) to an anaerobic (reduced) environment [4]. The main chemical change that occurs during flooding is the reduction of poorly soluble Fe3+ to highly soluble Fe2+, with a consequent increase in pH to values close to 6.5–7.0 in three to four weeks’ time [5,6]. The pH in acid soils increases with flooding, as reduction reactions consume H+ [4]. Manganese (Mn) is another cation whose oxidation-reduction is altered by flooding, changing from Mn (IV) (oxidized form) to more soluble Mn (II) (reduced form), and significant amounts of Mn2+ begin to accumulate in the exchange complex [7]. However, the determination of these exchangeable cations in soil samples after flooding is often underestimated, as protocols that involve agitation favor oxygen availability, thereby increasing their oxidized forms. This occurs mainly with Fe2+, which is highly unstable, leading to significant determination errors. The cations Na+, K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ are not directly involved in the oxidation–reduction reactions and what generally occurs is a displacement of these cations from the exchange sites to the soil solution [8]. As pH increases above 6.0, almost all exchangeable Al will precipitate and be removed from the exchangeable phase [9].

The CEC of soils under dryland conditions is composed mainly of the cations K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, and Al3+ [8]. However, with the changes caused by flooding, the ECEC of a soil after three to four weeks of flooding will be composed of K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Fe2+. Fe2+ can occupy a very significant portion of the exchange complex due to the large amounts of this element that can be reduced during flooding [4]. Another change caused by the increase in pH is the increase in variable soil charges or pH-dependent charges. Thus, the ECEC after flooding is expected to assume values close to those of the potential CEC (pH 7.0) [10]. The CEC is an important index of soil nutrient availability [10], acts on cation mobility throughout the soil profile and is also linked to aggregate formation and stability.

The process of chemically reducing Mn and Fe and increasing the concentration of these elements in the soil solution is beneficial for rice, as they increase the pH, the availability of Mn and Fe, and displaces other cations into the soil solution. Additionally, they are important because they increase phosphorus availability [7]. All these changes favor rice growth and development by increasing nutrient availability to plants [11,12]. However, under certain circumstances, Fe can reach toxic levels, impairing plant growth and rice yield [5,13]. Fe toxicity in irrigated rice is one of the most important abiotic stresses limiting rice production worldwide [14]. In severe cases, it can cause plant death and reduce rice yields by up to 100%, depending on the level of toxicity and the cultivar’s tolerance [15]. Predicting the occurrence of Fe toxicity in flood-irrigated soils can lead to more effective measures to prevent or minimize this disturbance. However, the simple interpretation of soil sample analysis conducted under dryland conditions does not align with conditions after flooding, given the transformations it causes. To solve this problem, it may be possible to estimate cation levels in flooded soil using soil characteristics related to chemical transformations during flooding. This can be determined in samples under dryland conditions. However, to establish all these relationships, it is necessary to have the amount of Fe2+ accumulated during flooding. Since acquiring this variable is very difficult, obtaining these data via estimation would allow one to establish the changes when comparing before and after flooding and, consequently, a way to predict the occurrence of Fe toxicity [5,16].

Thus, this work makes the assumption that, based on a sample collected before flooding, it is possible to estimate the ECEC after flooding through a linear relationship between the variation of pH before and after flooding with the variation of the ECEC and CEC pH 7.0, and assigning the difference between this estimated ECEC and the sum of the cations Ca, Mg, Mn, K and Na to the amount of exchangeable Fe2+ that starts to occupy the exchange sites after flooding. The linear relationship between pH-dependent charge and CEC was established by Barrow & Hartemink [10]. Based on what was previously mentioned, this paper aims to propose an alternative for estimating exchangeable Fe2+ and ECEC after flooding.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

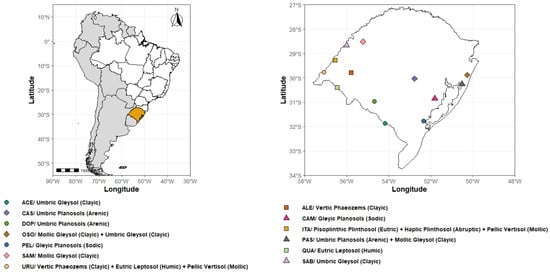

For this study, 21 soil surface samples (0–20 cm) from rice fields were collected and distributed from cultivation regions in southern Brazil. The proportion of soil classes sampled was carried out to reproduce what occurs in the environment, collecting in greater numbers the soils most cultivated with rice. Thus, most soils are located in floodplains, but some are on gently undulating relief. Table 1 describes the soil samples and their mapping units and its location in Figure 1. After collection, the samples were air-dried, sieved through a 4 mm mesh, and stored in plastic bags.

Table 1.

Samples from 21 rice field soils used in the experiment and their respective counties, located in southern Brazil. The soils are classified by World Reference Base for Soil Resources (WRB) [17], CEC at pH 7.0, and organic carbon content.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of soil sample collection points in paddy fields in southern Brazil. Figure made by the authors.

2.2. Soil Analysis

To ensure the accuracy of the results, the evaluations were conducted by adding control samples to the set of soil samples. Furthermore, our soil analysis laboratory is included in a quality control program coordinated by the Southern Regional Center of the Brazilian Society of Soil Science. To evaluate the effect of soil flooding on the quantities of exchangeable cations and to determine these cations in the soil solution, subsamples of 0.85 L of sieved soil were placed in duplicate in PVC pots measuring 7.5 cm in diameter and 30 cm in height. To facilitate soil reduction, ground corn straw (shoots) was added to the soil at 2 t ha−1 (0.85 g pot−1). The effect of corn straw should be limited to stimulating redox reactions, since its nutrient levels are insufficient to alter exchangeable cation levels significantly. Considering K as an example, if the corn straw contains 3% K, this amount corresponds to 0.08 cmolc kg of K, a value well below the total exchangeable cations in the soils of the study. The straw was mixed with the soils before placing them in the pots, together with enough water to raise the moisture content to values close to field capacity. After this procedure, the subsamples were placed in the incubation pots (the soil was added gradually, gently tapping the bottom of the pots on the table to help it settle). All pots were kept in this field capacity condition for 13 days and were then flooded with distilled water. The water level was maintained 5 cm above the soil surface for 50 days.

Collection tubes similar to those described elsewhere [4] were used to collect soil solution and were installed in the incubation vessels at the time the soil was placed. The solution was sucked from these tubes using a plastic syringe. Soil solution samples were collected at 1 day and 50 days after flooding. The solution collected after 1 day of flooding was considered representative of the oxidized conditions of the soils.

As the samples were placed in the pots, a subsample of each soil was collected, which was air-dried again and used to determine the contents of exchangeable cations before flooding (K, Na, Ca, Mg, Mn, Al and H + Al). The K and Na cations were extracted with 1 mol L−1 NH4OAc pH 7.0, the cations Ca, Mg, Mn and Al with 1 mol L−1 KCl and the H + Al cations with 1 mol L−1 CaOAc pH 7.0 [18]. The cations were extracted with a single extraction. In all cases, a soil–extractor ratio of 1:10 was used with shaking for 1 h. After extraction, the determination of Na and K in the extracts was performed by flame photometry (ELEVELAB Equipamentos Científicos, model FP-6400, Porto Alegre City, Brazil), the determination of Ca, Mg and Mn by atomic absorption spectrophotometry (GBC Scientific Equipment, model GBC-SAVANTAA, São Paulo City, Brazil), and the determination of Al and H + Al by titration with NaOH. The ECEC of the soil was determined by the sum of K, Na, Ca, Mg, Mn and Al, while the CEC at pH 7.0 was determined by the sum of K, Na, Ca, Mg, Mn and H + Al [18]. The sum of cations, when correctly expressed in charge units (cmolc kg−1), represents the total amount of positive charges that the soil can retain, which is the practical definition of CEC.

At the end of the soil flooding period (50 days), the exchangeable cation contents were determined again. To do this, a second collection of subsamples was performed using a plastic syringe with the end cut to form a collection tube. This tube was inserted into the soil through a hole in the wall of the incubation vessel, with a diameter that allowed the collection tube to fit snugly (this hole was made before placing the soils in the vessels and was kept closed during the incubation period using a rubber stopper). The collection of subsamples of approximately 3 cm3 was performed under a N2 jet, spraying the gas onto the samples as they were removed from the soil until they were released into a centrifuge tube containing 30 mL of the 1 mol L−1 KCl extraction solution. The tubes were immediately capped and weighed to determine the soil weight (the tare weight of the tubes was previously determined). They were then shaken for 1 h and centrifuged. A 10 mL aliquot of the supernatant was then removed with a pipette and placed in a glass containing 1 mL of 1.1 mol L−1 HCl, so that the final acid concentration was 0.1 mol L−1. Subsequently, the exchangeable Fe and Mn contents were determined by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Exchangeable K was determined using the same procedure as for the sample before flooding. Part of the subsample corresponding to the middle of the incubation tube was used, and for this purpose, the upper half of the soil from the tubes was eliminated. Since it was found that exchangeable K did not change after flooding relative to the initial levels, it was assumed that the exchangeable cations Ca and Mg did not change either. These cations were not determined after flooding. In all cases, the soil moisture content was determined, and cation levels were calculated on a dry soil basis; the concentration of the soil solution was subtracted when determining the exchangeable levels.

The pH of the soil solution was determined on the first day and 50 days after flooding, using samples collected with a syringe, as previously described. For this purpose, 20 mL aliquots of the solution were injected immediately after collection into an electrometric cell containing a combined electrode for pH measurement. The electrometric cell was constructed from an acrylic flask and a rubber stopper with holes for electrode installation, as described in [4]. The volume of solution in the cell equipped with the electrode was 18 mL. The solution was injected into the cell with the same syringe in which it had been collected from the incubation vessels, through a small feeding tube inserted flush with the bottom of the cell. This was performed until it filled the entire volume of the cell and the excess exited through the discharge hose connected to the lid, releasing the excess into a beaker. This was intended to minimize any contact between the solution and oxygen.

The soil solution was collected in the same manner as for pH determinations. It was filtered through a 0.45 µm Millipore filter immediately after collection, under vacuum, and the filtrate was placed in a glass vial with 1 mL of 1.1 mol L−1 HCl. The aliquots had a volume of 10 mL, so that the final acid concentration was 0.1 mol L−1. To calculate the exact sample dilution with acidification, the glass vials were weighed before and after adding acidified soil solution. In the solution thus collected and acidified, the concentrations of Na, K, Ca, Mg, Fe, and Mn were determined: the first two by flame photometry and the others by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Soluble Al3+ was considered insignificant. In 3 of the 21 samples (1, 10, 19), solution measurements were taken weekly to determine approximately when the transformations reached their peak, which occurred at 49 days of flooding. Afterward, all samples were collected and analyzed. To estimate the amount of exchangeable Fe accumulated during flooding, the ECEC after flooding of the soil (ECECafter) was first estimated solely from the variation in cation exchange capacity determined in the dry soil samples and the variation in pH resulting from soil reduction. In this sense, the estimated ECEC after flooding was calculated using Equation (1).

The estimation of exchangeable Fe is based on the estimated ECEC and the contents of exchangeable cations, both after flooding. Since exchangeable Ca, Mg, K, and Na do not change much after flooding and, with the increase in pH, Al3+ is neutralized, it is assumed that any increase in CEC due to the increase in pH resulting from flooding is reflected in the contents of Mn and Fe. Therefore, the difference between the estimated ECEC after flooding and the sum of Ca, Mg, K, Na and Mn can be attributed to the exchangeable Fe content after flooding. Thus, the estimated exchangeable Fe content after flooding was calculated using Equation (2).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The results of the cation fractions in the soil solution, in the ECEC and in the estimated ECEC, both after flooding, were subjected to analysis of variance using the F test and, when significant, were compared using the Duncan mean comparison test at p ≤ 0.05 (qualitative factor).

3. Results

3.1. pH, Mn, Fe, K, Ca and Mg in Soil Solution

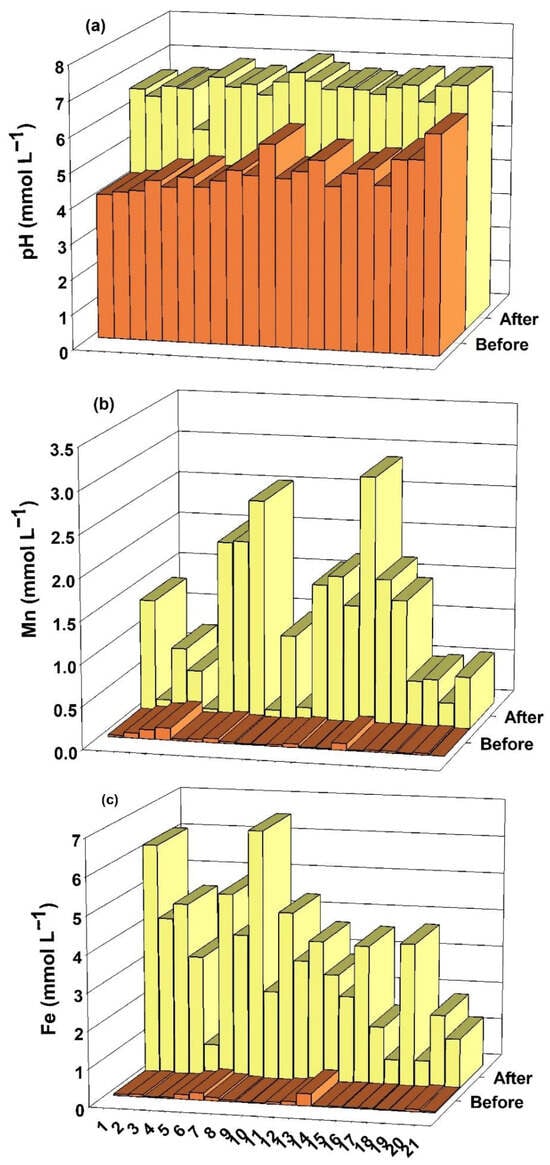

The concentrations of Mn and Fe in the solution of the 21 soil samples are presented in Figure 2, before and after flooding. The Mn concentration increased in all soil samples with flooding. On average, it went from 0.03 mmol L−1 before to 1.12 mmol L−1 after flooding. Soil flooding increased Fe concentration in the soil solution, from 0.06 mmol L−1 before to 3.19 mmol L−1 after flooding.

Figure 2.

pH values (a), Mn (b) and Fe (c) concentrations in the solutions of 21 soil samples from rice fields in southern Brazil, before and after 50 days of flooding.

The pH values after a 50-day flooding period increased in all samples on average, ranging from 4.89 before to 6.71 after the flooding (Figure 2).

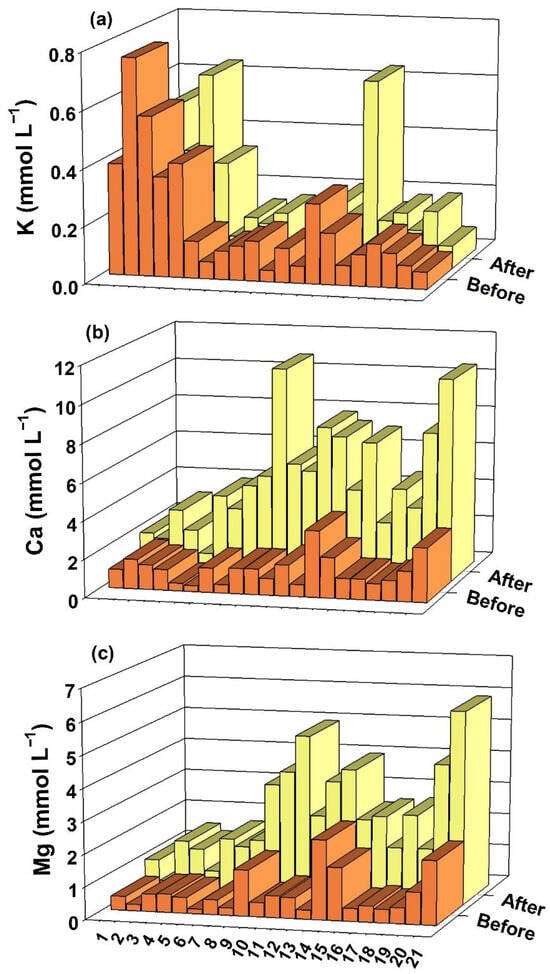

The data on the concentrations of K, Ca and Mg in the solution of the soil samples before and after flooding are presented (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

K (a), Ca (b) and Mg (c) contents in the soil solution of 21 soil samples from rice fields in southern Brazil, before and after 50 days of flooding.

The concentrations of Ca and Mg increased in all samples with flooding (Figure 3), on average going from 1.30 to 5.07 mmol L−1 and from 0.73 to 2.57 mmol L−1 after flooding, respectively.

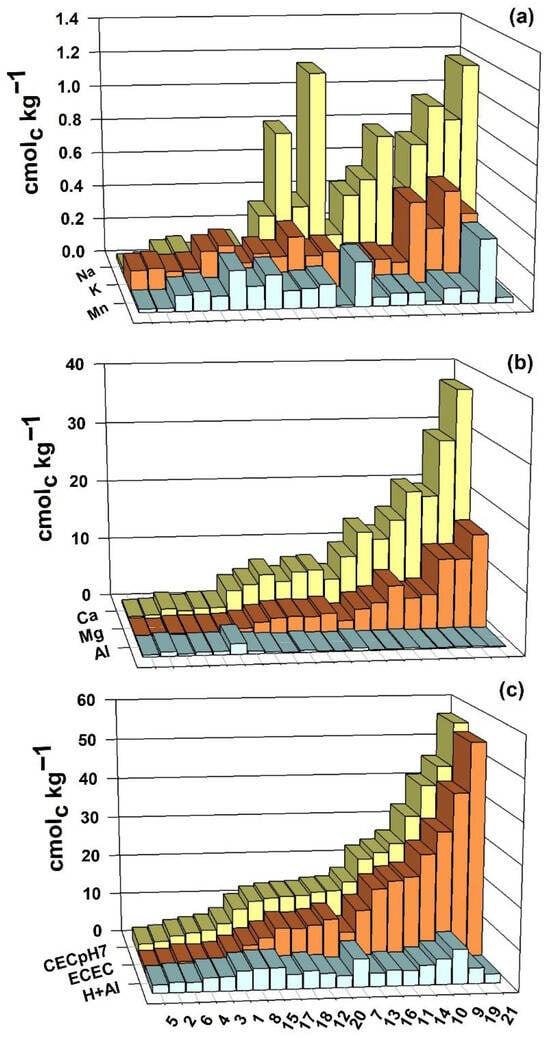

3.2. Exchangeable Cation Contents, ECEC and CEC at pH 7.0

Exchangeable cation contents of the soil samples before flooding are presented (Figure 4). There was a wide range of variation in the contents among the soil samples. The K contents ranged from 0.12 to 0.54 cmolc kg−1, the Na contents from 0.00 to 1.18 cmolc kg−1, the Ca contents from 0.48 to 37.31 cmolc kg−1, the Mg contents from 0.10 to 15.53 cmolc kg−1, the Mn contents from 0.01 to 0.36 cmolc kg−1, the Al contents from 0.10 to 1.74 cmolc kg−1 and the H+Al contents from 2.01 to 8.42 cmolc kg−1.

Figure 4.

Exchangeable cation contents (a,b), effective cation exchange capacity (c), and pH 7.0 (c) of 21 soil samples from rice fields in southern Brazil, before flooding.

There was a wide range of variation in the CEC values of the soil samples (Figure 4), both at pH 7.0 and at pH 4.0, which is necessary in studies such as this. The values of the ECEC ranged from 1.27 to 54.43 cmolc kg−1, while those of the CEC at pH 7.0 ranged from 2.93 to 56.54 cmolc kg−1. In both cases, the CEC was lower in soil 5 and higher in soil 21.

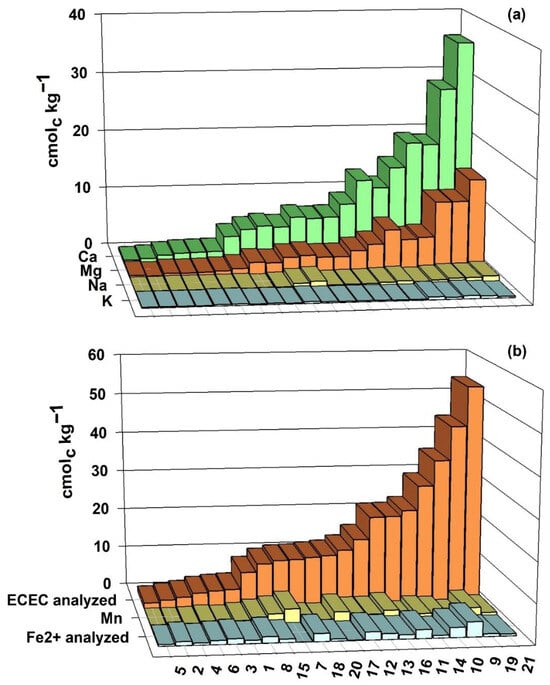

The values of exchangeable cations and ECEC of the 21 soil samples subjected to 50 days of flooding are shown (Figure 5). It should be noted that the exchangeable H content was not determined, as the soils’ pH after flooding was, on average, 6.7 (Figure 2). When the soil reaches pH values above 6.0, the exchangeable H is completely neutralized [9].

Figure 5.

Exchangeable cation contents (a), Mn (b) and Fe2+ analyzed (b) and ECEC (b) of 21 soil samples from rice fields in southern Brazil, after a 50-day flooding period, in the laboratory.

Flooding of the soil did not cause pronounced effects on the exchangeable K contents, which showed small variations both upwards and downwards in the samples. Still, the average of all soils after flooding remained the same as before flooding, 0.23 cmolc kg−1 (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

The exchangeable Na contents behaved similarly to K, showing small variations both upwards and downwards in the samples, and, on average, decreased from 0.45 cmolc kg−1 before (Figure 4) to 0.41 cmolc kg−1 after flooding (Figure 5), being less affected by soil reduction. The Ca and Mg contents decreased in the exchangeable phase as the soil was reduced due to flooding (Figure 5).

The Mn contents in the exchangeable phase increased in all samples with soil reduction. On average, they went from 0.11 cmolc kg−1 before flooding (Figure 4) to 1.17 cmolc kg−1 after 50 days of flooding (Figure 5). The exchangeable Fe content after flooding varied widely among samples, ranging from 0.04 to 3.76 cmolc kg−1 (Figure 5).

The ECEC of soils after flooding is determined by the sum of the exchangeable contents of K, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe and Mn. The values found varied widely, from 1.34 to 54.25 cmolc kg−1 (Figure 5).

3.3. CEC and Fe2+ Estimates

The values of exchangeable Fe2+ and ECEC estimated in flooded soils were higher than the observed by the analytical method (Table 2). The ECEC values estimated after flooding, with an average of 18.41 cmolc kg−1, 1.97 cmolc kg−1 higher than the ECEC determined after flooding are presented (Table 2). The estimated exchangeable Fe values were, on average, 1.19 cmolc kg−1. The exchangeable Fe contents were also higher than those estimated analytically.

Table 2.

Estimated and analyzed ECEC and exchangeable Fe content of 21 soil samples from rice fields in southern Brazil, after 50 days of flooding, in the laboratory.

4. Discussion

4.1. pH, Mn, Fe, K, Ca and Mg in Soil Solution

The increase in Mn concentration with soil flooding was also observed before [4], due to the reduction of Mn (IV) (manganic oxides) to Mn (II) (manganous oxides) and the consequent release into the soil solution [7]. Other authors also observed an increase in Fe concentrations due to soil flooding, with peak Fe concentration varying between soils [4]. The increase in the concentration of this cation in the soil solution is due to the reduction of Fe (III) (ferric oxides) to Fe (II) (ferrous oxides) and the consequent release into the soil solution [5]. The increase in pH in flooded acidic soils is due to the reduction reactions of oxidized compounds in the soil, which always occur with the consumption of H+ ions [19]. The increase in pH promotes the increase of negative charges in the soil (pH-dependent charges), through the dissociation of organic and mineral functional groups. In the soils under study, organic matter is the main contributor to the variable soil charges [19].

With soil flooding, the pH of acidic soils converges to values close to 7.0, except for soils with low Fe contents [4]. Such an example is soil 5, which had a pH of 5.44, well below the average of 6.71, and was the only soil with a pH value after flooding below 6.0. The concentrations of both Mn and Fe in the soil solution are low in this soil (Figure 2), i.e., as there are few reduction products, soil reduction was probably low and H+ consumption was small, consequently the pH after flooding was well below that of other soils.

The optimum pH of the soil solution for rice plants is approximately 6.6 [20], since at this pH value the supply of most nutrients is adequate, and the concentration of toxic substances is below the levels capable of causing toxicity. The soil solution samples in the present study maintained their pH after flooding close to this optimum value, except for sample 5, which had a pH well below this value, as already mentioned. In general, K was less affected by flooding, with an average concentration of 0.20 mmol L−1 before and 0.24 mmol L−1 after flooding. Although the cations K, Ca and Mg are not directly involved in the oxidation–reduction reactions of flooded soils, their behavior is closely related to the behavior of Fe and Mn, being displaced from the exchange complex to the soil solution by these cations. Fe, Mn and Ca have similar selectivity for adsorption on the surface of clays [21], so when there is an increase in Fe or Mn in the solution, the exchange and displacement of Ca from the exchange site to the soil solution will occur concurrently [22].

4.2. Exchangeable Cation Contents, ECEC and CEC at pH 7.0

A study carried out with 16 samples of floodplain soils from southern Brazil, K levels ranging from 0.08 to 0.48 cmolc kg−1, Ca levels from 0.60 to 20.80 cmolc kg−1, Mg levels from 0.60 to 9.30 cmolc kg−1 and Al levels from 0.00 to 2.60 cmolc kg−1 were observed [23]. In another study, with 57 soil samples from floodplains in southern Brazil [24], observed variations in K levels from 0.03 to 0.75 cmolc kg−1, Na levels from 0.02 to 1.32 cmolc kg−1, Ca levels from 0.00 to 20.40 cmolc kg−1, Mg levels from 0.00 to 8.33 cmolc kg−1 and H+Al levels from 1.19 to 16.93 cmolc kg−1. Comparing the results with data in the literature, it is observed that the levels obtained in this work are within the range cited in the literature, except in two soil samples (19 and 21), whose maximum values of Ca and Mg are above the limits observed by [23,24].

As the floodplain soils used for irrigated rice cultivation in southern Brazil originate from a wide variety of rocks and sediments influenced by environmental factors, soils with very distinct chemical and physical characteristics were formed [25].

The lowest CEC values were observed in Planosol samples, while the highest were observed in Gleysols. Planosols generally have a sandy texture and low organic matter content, while Gleysols have a medium to clayey texture with high organic matter content, which gives them a high CEC [25]. Similar results [24], in which a range of 3.01 to 42.07 cmolc kg−1 of CEC at pH 7.0 in 57 soil samples from southern Brazil, were found.

Exchangeable K and Na were not much affected by flooding (Figure 5). This result is consistent, since K and Na are not directly involved in oxidation–reduction reactions, and since there were no major changes in the concentrations in the soil solution (Figure 3), exchangeable K and Na were not affected.

The Ca and Mg cations are not directly involved in the soil reduction reactions, but there was a displacement of these elements to the soil solution, mainly by Fe [20], decreasing the values in the exchangeable phase (Figure 5). Fe, Mn and Ca have similar selectivity for adsorption on the surface of clays [21]. Therefore, the amount of Ca and Mg displaced into the solution is proportional to the amount of Fe2+ that was formed during the flooding and that came to occupy the charges in place of these cations. Unlike what happens with Fe, no new exchangeable Ca and Mg are formed after flooding, but rather there is a change in the cation in solution/exchangeable cation ratio. Adding the concentrations of exchangeable Ca and Ca in solution before and after flooding yields the same values, and the same happens with Mg. The average sum of exchangeable Ca + solution Ca was 10.07 cmolc kg−1 before flooding and 10.09 cmolc kg−1 after flooding. Regarding Mg, the average of exchangeable Mg + solution Mg was 4.09 cmolc kg−1 before flooding and 4.10 cmolc kg−1 after flooding.

The exchangeable Mn2+ content is low in most soils. Still, as flooding increases the concentration of this cation in the soil solution (Figure 5), due to the reduction of Mn from manganic to manganous oxides [7], Mn2+ begins to be adsorbed from the soil solution onto the exchangeable phase, thereby considerably increasing its quantity.

In soil under aerobic conditions, Fe does not participate significantly in the exchange complex due to its low solubility and small free form concentration. Still, under reducing conditions, Fe changes from the 3+ valence state to 2+, increasing its solubility and concentration (Figure 5). The chemical reduction of Fe and the consequent increase of its concentration in the soil solution and in the exchangeable phase is considered the major change occurring in a flooded soil [4,20].

On average, the CEC was 16.44 cmolc kg−1, a value that was below expectations, since on average the ECEC of samples under rainfed conditions was 15.11 cmolc kg−1 and the average CEC at pH 7.0 was 18.85 cmolc kg−1 (Figure 4), with a difference of 3.74 cmolc kg−1. As the soil pH averaged 6.71 after the flooding period (Figure 2), 1.82 units higher than before flooding and close to pH 7.0, a higher ECEC was expected after flooding, closer to the CEC at pH 7.0. These results confirm that the analytical determination of CEC in flooded soils is inaccurate and support the notion that these values need to be corrected.

4.3. CEC and Fe2+ Estimates

Considering that after flooding there are no significant concentrations of exchangeable Al3+ due to the increase in pH and that the concentrations of exchangeable K, Na, Ca and Mg do not change significantly, it is believed that there are no errors in the determination of these cations. Thus, it is expected that the differences may be related to the determination of Mn and Fe, which are the cations that increase greatly with soil reduction. Possibly, the difference between the measured and estimated CEC values lies in these cations; that is, they must be underestimated despite the care taken to sample and analyze them, since, in the reduced form, these elements are not stable and oxidize easily in contact with oxygen. Since soils generally have higher amounts of Fe than Mn, and because Fe is much less stable than Mn, most of the difference should be in the determination of Fe. Thus, we attempted to correct this possible underestimation of Fe and the consequent ECEC by estimating ECEC after flooding based on the ECEC and CEC at pH 7.0 determined in dry soil and the pH variation before and after flooding, using equations 1 and 2. The values of the ECEC estimated after flooding, with an average of 18.41 cmolc kg−1, 1.97 cmolc kg−1 higher than the ECEC determined after flooding are presented (Table 2). These values were closer to the CEC determined at pH 7.0, which was 18.85 cmolc kg−1 (Figure 4), as expected, since the pH of the solution after flooding was on average 6.7, close to the CEC value of 7.0.

The exchangeable Fe values estimated after flooding (Table 2) were higher than those determined, suggesting a correction, as the determined values may have been underestimated by the determination method, as discussed previously.

The cations Fe2+, Mn2+ and Ca2+ have similar selectivity coefficients; that is, there is no adsorption preference in the solid phase between these cations [21]. Thus, it is assumed that the molar fraction between these divalent cations in the soil solution is proportional to the percentage they occupy in the exchangeable phase. Therefore, if we compare the molar fractions of these between the soil solution and the fraction in the exchangeable phase, the values should be very similar.

The molar fractions of the cations in the soil solution and in the exchangeable phase are shown (Table 3). Comparing the fractions in the soil solution with the fractions in the CEC determined after flooding, the fractions are very similar for Mn and Mg, but there is a discrepancy between the fractions for Ca and Fe (Table 3). Using the two methods for determining Fe (soil solution and exchange complex) as a basis, it is possible that the levels are underestimated in both cases. However, this underestimation is likely much smaller in determining the solution, given the care taken at the time of collection to avoid contact of the sample with oxygen in the air. It is also worth mentioning that the quantity in the solution is much smaller than in the exchangeable phase. With this evaluation, it is clear that most of the error is, in fact, in the exchangeable Fe after flooding, since the fraction in the solution of Mn was very similar to the molar fraction in the exchange complex.

Table 3.

Molar fractions of cations in the soil solution, in the exchangeable phase, and estimating the average CEC from 21 rice field soil samples in southern Brazil, after a 50-day flooding period.

Now, comparing the molar fractions in the solution with the fractions estimating the ECEC and exchangeable Fe (Table 3), an improvement in the results is noted, where the proportion of Mg, Fe and Mn are equal in the soil solution with the exchangeable phase, confirming the correction of the amounts of Fe underestimated by the determination.

In summary, there are three assumptions that contribute to demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method: (i) iron and manganese change their oxidation–reduction state with flooding. In the valence 2+ state, they are more soluble, and their concentrations in the soil solution and the exchangeable phase increase. However, during the extraction process for CEC analysis during flooding, part of Fe2+ returns to its oxidized form, which is less soluble and therefore precipitates. This does not happen for other cations. (ii) Since there is a linear relationship between the effective CEC and the CEC at pH 7, this linear relationship allows the calculation of the CEC that soils present at any pH value, including the pH value of flooded soil. (iii) Considering that there is no adsorption preference between the cations Ca2+, Fe2+, Mg2+ and Mn2+ [21], it is assumed that the mole fraction of these divalent cations in the soil solution is proportional to the percentage they occupy in the exchangeable phase. Therefore, if we compare the mole fractions of these cations between the soil solution and the fraction in the exchangeable phase, the values should be very similar. Particularly regarding iron, there is no statistical difference between the soil solution mole fractions and the proposed CEC estimation method, indicating that the exchangeable iron estimate effectively corrected the error caused by the traditional CEC measurement method. This suggests that this is a reliable method and, so far, the best alternative to accurately measure iron content in the soil solution in flooded soils.

The results generated allowed a better understanding of the main cations exchangeable fractions and in solution, involved in the nutrition of rice and iron toxicity, enabling perspectives of studying this nutritional disturbance as a way to predict its occurrence really efficiently.

5. Conclusions

The ECEC estimates after flooding through the equation , and the exchangeable Fe2+ after flooding through the equation corrected the problem of subestimating the values of these variables by analytical methods, demonstrating its viability for use in flood-prone soils. Where pHsol.before is pre-flooding soil pH, pHsol.after is after flooding pH, ECECafter is after flooding effective CEC, Feexc.after.estimated is estimated exchangeable Fe2+ after flooding.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C.V. and R.O.d.S.; methodology, R.O.d.S.; validation, R.C.D.W. and R.O.d.S.; formal analysis, R.C.D.W.; investigation, R.C.D.W.; resources, R.O.d.S.; data curation, R.B.d.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.C.D.W.; writing—review and editing, A.C.d.O., F.S.C., L.C.V. and R.O.d.S.; supervision, R.O.d.S.; project administration, R.O.d.S.; funding acquisition, R.O.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Brazilian Council for Research and Development (CNPq), grant number 2013 and fellowships to A.C.d.O.; the Coordination of Improvement of Superior Personel (CAPES), fellowship to R.C.D.W. and Rio Grande do Sul State Agency for Support to Research (FAPERGS).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/Original_data_Study_Estimation_of_Effective_Cation_Exchange_Capacity_and_Exchangeable_Iron_in_Rice_Fields_After_Soil_Flooding/29949608 (dataset posted on 11 December 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Universidade Federal de Pelotas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CEC | Cation Exchange Capacity |

| ECEC | Effective Cation Exchange Capacity |

References

- SOSBAI. Arroz Irrigado—Recomendações técnicas da pesquisa para o Sul do Brasil. In Sociedade Sul Brasileira de Arroz Irrigado; SOSBAI: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa, R.O.; Carlos, F.S.; da Silva, L.S.; Scivittaro, W.B.; Ribeiro, P.L.; de Lima, C.L.R. No-tillage for flooded rice in Brazilian subtropical paddy fields: History, challenges, advances and perspectives. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2021, 45, e0210102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, A.S.; Carlos, F.S.; Martins, G.L.; Monteiro, G.G.T.N.; Roesch, L.F.W. Bacterial Resilience and Community Shifts Under 11 Draining-Flooding Cycles in Rice Soils. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sousa, R.O.; Bohnen, H.; Meurer, E.J. Composição da solução de um solo alagado conforme a profundidade e o tempo de alagamento, utilizando novo método de coleta. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2002, 26, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos Carmona, F.; Adamski, J.M.; Wairich, A.; de Carvalho, J.B.; Lima, G.G.; Anghinoni, I.; Jaeger, I.R.; da Silva, P.R.F.; de Freitas Terra, T.; Fett, J.P.; et al. Tolerance mechanisms and irrigation management to reduce iron stress in irrigated rice. Plant Soil 2021, 469, 173–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyagoda, L.D.B.; Sirisena, D.N.; Somaweera, K.A.T.N.; Dissanayake, A.; De Costa, W.A.J.M.; Lambers, H. Incorporation of dolomite reduces iron toxicity, enhances growth and yield, and improves phosphorus and potassium nutrition in lowland rice (Oryza sativa L). Plant Soil 2017, 410, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, L.A.; Uren, N.C. Manganese oxidation and reduction in soils: Effects of temperature, water potential, pH and their interactions. Soil Res. 2014, 52, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, T.; Bruneel, Y.; Smolders, E. Comparison of five methods to determine the cation exchange capacity of soil. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2023, 186, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; Denardin LGde, O.; Tiecher, T.; Borin, J.B.M.; Schaidhauer, W.; Anghinoni, I.; Carvalho PCde, F.; Kumar, S. Nine-year impact of grazing management on soil acidity and aluminum speciation and fractionation in a long-term no-till integrated crop-livestock system in the subtropics. Geoderma 2020, 359, 113986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrow, N.J.; Hartemink, A.E. The effects of pH on nutrient availability depend on both soils and plants. Plant Soil 2023, 487, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, J.B.M.; de Campos Carmona, F.; Anghinoni, I.; Martins, A.P.; Jaeger, I.R.; Marcolin, E.; Hernandes, G.C.; Camargo, E.S. Soil solution chemical attributes, rice response and water use efficiency under different flood irrigation management methods. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 176, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, F.S.; de Oliveira Denardin, L.G.; Martins, A.P.; Anghinoni, I.; Carvalho, P.C.F.; Rossi, I.; Buchain, M.P.; Cereza, T.; Carmona, F.C.; de Oliveira Camargo, F.A. Integrated crop–livestock systems in lowlands increase the availability of nutrients to irrigated rice. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 2962–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzschuh, M.J.; Carlos, F.S.; Carmona, F.C.; Bohnen, H.; Anghinoni, I. Iron oxidation on the surface of adventitious roots and its relation to aerenchyma formation in rice genotypes|Oxidação do Fe na superfície de raízes adventícias e sua relação com a formação de aerênquima em genótipos de arroz. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2014, 38, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F.; Fortes, M.d.Á.; Wesz, J.; Buss, G.L.; de Sousa, R.O. The impact of water management on iron toxicity in flooded rice. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2013, 37, 1226–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahrawat, K.L. Iron Toxicity in Wetland Rice and the Role of Other Nutrients. J. Plant Nutr. 2004, 27, 1471–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, H.; Ahmed, S.F.; Santiago-Arenas, R.; Himanshu, S.K.; Mansour, E.; Cha-um, S.; Datta, A. Tolerance mechanism and management concepts of iron toxicity in rice: A critical review. Adv. Agron. 2023, 177, 215–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps, 4th ed.; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Rome, Italy, 2022; Available online: https://www3.ls.tum.de/boku/?id=1419 (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Tedesco, M.; Gianello, C.; Bissani, C.; Bohnen, H.; Volkwiess, S. Análises de Solo, Plantas e Outros Materiais, 2nd ed.; Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, C.; Du, S.; Ma, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X. Changes in the pH of paddy soils after flooding and drainage: Modeling and validation. Geoderma 2019, 337, 511–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnamperuma, F.N. The Chemistry of Submerged Soils. Adv. Agron. 1972, 24, 29–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, K.; Wada, S.; Shibata, M. Ca2+-Fe2+ and Ca2+-Mn2+ exchange selectivity of kaolinite, montmorillonite, and ilite. Soil Sci. 2004, 169, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orucoglu, E.; Grangeon, S.; Gloter, A.; Robinet, J.C.; Madé, B.; Tournassat, C. Competitive Adsorption Processes at Clay Mineral Surfaces: A Coupled Experimental and Modeling Approach. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2022, 6, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.S.; Ranno, S.K.; Rhoden, A.C.; Santos, D.R.; Graupe, F.A. Avaliação de métodos para estimativa da disponibilidade de fósforo para arroz em solos de Várzea do Rio Grande do Sul. Rev. Bras. Ciência Solo 2008, 32, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, C.E.S.d. Caracterização Química e Disponibilidade de Enxofre em Solos de Várzea do Rio Grande do Sul. Master’s Thesis, Faculdade de Agronomia Eliseu Maciel, Pelotas, Brazil, 2008; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Streck, E.V.; Kampf, N.; Dalmolin, R.S.D.; Klamt, E.; do Nascimento, P.C.; Schneider, P.; Giasson, E.; Pinto, L.F.S. Solos do Rio Grande do Sul, 2nd ed.; Emater/RS: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.