Non-Invasive Soil Texture Prediction Using Machine Learning and Multi-Source Environmental Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- to develop a dynamic, laboratory-independent soil texture classification model based solely on soil moisture and environmental response patterns,

- (2)

- to encode soil hydrological behavior using LSTM-based temporal representation learning, and

- (3)

- to predict ordered soil texture classes using ordinal regression, ensuring physical consistency and reducing unrealistic misclassification errors.

2. Materials and Methods

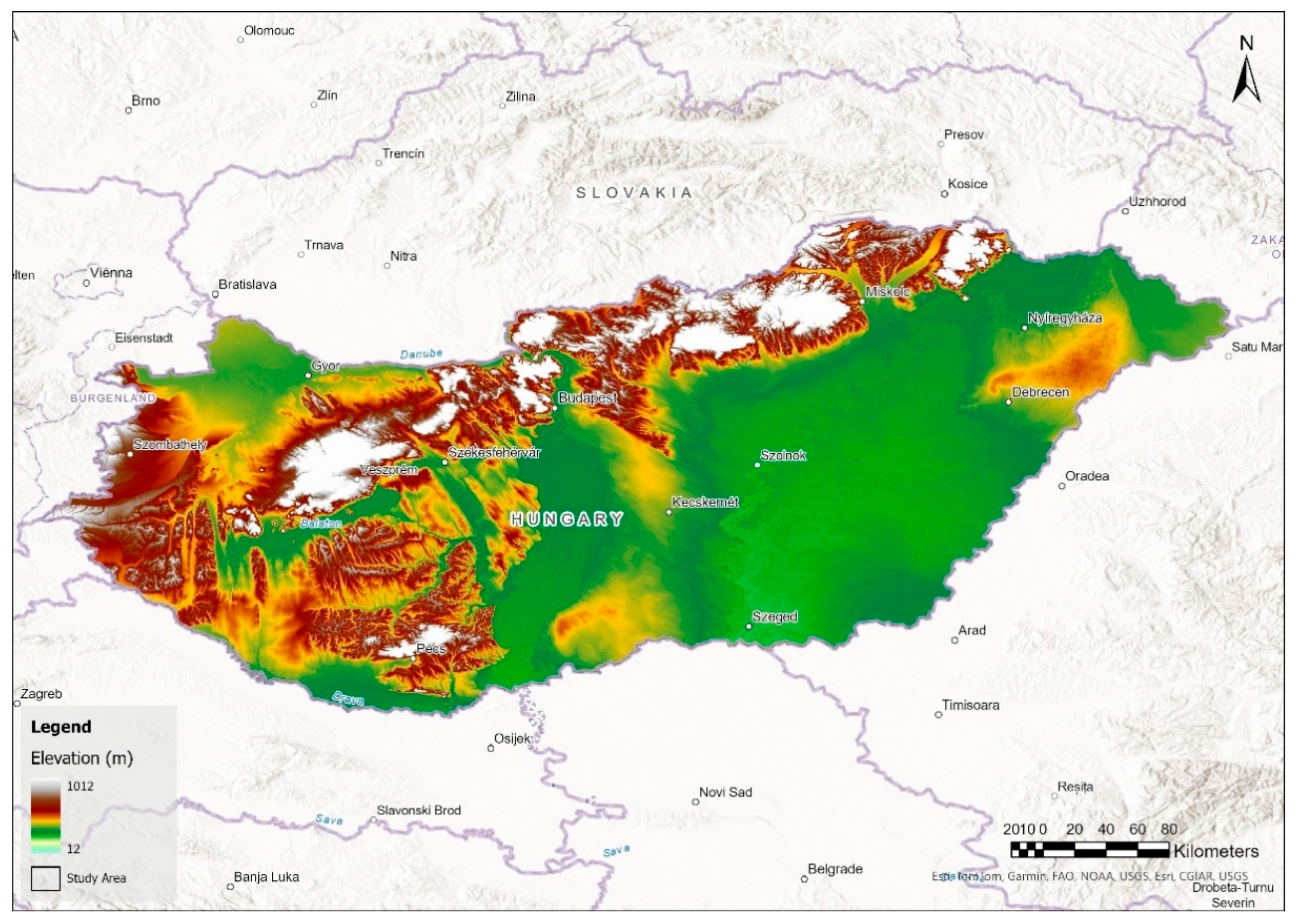

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Sampling Design and Experimental Scheme

2.2.2. Land-Use of the Sampling Areas

2.2.3. Soil Texture

2.2.4. Sentek EnviroScan Sensor

2.2.5. Remote Sensing Data

2.2.6. Data Description

Target Variables

Input Features

- SL: Slope,

- SL_i+1 is the next SL value,

- SL_i−1 is the previous SL value,

- Denominator 2 ensures a centered approximation of the slope.

2.2.7. Model Performance Evaluation

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Retrieval of SF from the Measured Soil Moisture

- SF = Scaled Frequency

- SM = Volumetric Soil Water Content (mm)

- A = 0.19570, B = 0.40400, C = 0.02852 (default calibration coefficients [30])

2.3.2. Dataset and Leakage Control

2.3.3. Remote Sensing Image Selection and Processing

Sentinel 2 Data: Spatial and Temporal Characteristics

Preprocessing of Sentinel-2 Data

2.3.4. Predictive Modeling

2.3.5. LSTM–Ordinal Model Application

3. Results

3.1. Variable Influence

3.2. Soil Texture Prediction Using LSTM-Derived Temporal Embeddings: Performance and Interpretability Analysis

3.2.1. Model Performance Analysis

3.2.2. Model Learning Curve Analysis

3.2.3. SHAP Plot for LSTM-Derived Embeddings

3.2.4. Confusion Matrix Analysis

3.2.5. Evaluation of Model Predictions: True vs. Predicted Soil Composition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hillel, D. Introduction to Environmental Soil Physics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bouma, J. Using Soil Survey Data for Quantitative Land Evaluation. In Advances in Soil Science: Volume 9; Stewart, B.A., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 177–213. ISBN 978-1-4612-3532-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G.W.; Bauder, J.W. Particle-Size Analysis. In Methods of Soil Analysis; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1986; pp. 383–411. ISBN 9780891188643. [Google Scholar]

- Adamchuk, V.I.; Hummel, J.W.; Morgan, M.T.; Upadhyaya, S.K. On-the-Go Soil Sensors for Precision Agriculture. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2004, 44, 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minasny, B.; McBratney, A.B. Digital Soil Mapping: A Brief History and Some Lessons. Geoderma 2016, 264, 301–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, K.E.; Rawls, W.J. Soil Water Characteristic Estimates by Texture and Organic Matter for Hydrologic Solutions. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2006, 70, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huete, A.R.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, G.; Zhang, X. Analysis of NDVI and Scaled Difference Vegetation Index Retrievals of Vegetation Fraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 101, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcbratney, A.; Mendonça Santos, M.; Minasny, B. On Digital Soil Mapping. Geoderma 2003, 117, 3–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ließ, M.; Glaser, B.; Huwe, B. Uncertainty in the Spatial Prediction of Soil Texture: Comparison of Regression Tree and Random Forest Models. Geoderma 2012, 170, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagas, C.d.S.; de Carvalho Junior, W.; Bhering, S.B.; Calderano Filho, B. Spatial Prediction of Soil Surface Texture in a Semiarid Region Using Random Forest and Multiple Linear Regressions. Catena 2016, 139, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocsis, K.; Gercsák, G.; Kovács, Z.; Nemerkényi, Z.; Kincses, A.; Tóth, G.; Agárdi, N.; Koczó, F.; Mezei, G.; McIntosh, R.W. National Atlas of Hungary: Society; Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Geographical Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2021; ISBN 9789639545588. [Google Scholar]

- Gábris, G.; Pécsi, M.; Schweitzer, F.; Telbisz, T. Relief. In National Atlas of Hungary—Natural Environment; MTA CSFK Geographical Institute: Budapest, Hungary, 2018; pp. 42–57. [Google Scholar]

- Spinoni, J.; Szalai, S.; Szentimrey, T.; Lakatos, M.; Bihari, Z.; Nagy, A.; Németh, Á.; Kovács, T.; Mihic, D.; Dacic, M.; et al. Climate of the Carpathian Region in the Period 1961–2010: Climatologies and Trends of 10 Variables. Int. J. Climatol. 2015, 35, 1322–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibirige, D.; Dobos, E. Off-Site Calibration Approach of EnviroScan Capacitance Probe to Assist Operational Field Applications. Water 2021, 13, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazekas, I.; Nel, A. Sesiidae Wing Impression in Miocene (Badenian) Dacitic Tuff from Hungary (Magyaregregy, Mecsek Mountains). Lepidopterol. Hung. 2025, 22, 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nrcs, U. Soil Survey Manual Soil Science Division Staff Agriculture Handbook No. 18; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Paltineanu, I.C.; Starr, J.L. Real-Time Soil Water Dynamics Using Multisensor Capacitance Probes: Laboratory Calibration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1997, 61, 1576–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajdu, I.; Yule, I.; Bretherton, M.; Singh, R.; Hedley, C. Field Performance Assessment and Calibration of Multi-Depth AquaCheck Capacitance-Based Soil Moisture Probes under Permanent Pasture for Hill Country Soils. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 217, 332–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provenzano, G.; Rallo, G.; de Almeida, C.D.G.C.; de Almeida, B.G. Development and Validation of a New Calibration Model for Diviner 2000® Probe Based on Soil Physical Attributes. Water 2020, 12, 3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, C.; Qian, H.; Cao, W.; Ni, J. Design and Test of a Soil Profile Moisture Sensor Based on Sensitive Soil Layers. Sensors 2018, 18, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, J.H.; Topp, G.C. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 4: Physical Methods; Soil Science Society of America, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kelleners, T.J.; Soppe, R.W.O.; Ayars, J.E.; Skaggs, T.H. Calibration of Capacitance Probe Sensors in a Saline Silty Clay Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rosny, G.; Chanzy, A.; Pardé, M.; Gaudu, J.-C.; Frangi, J.-P.; Laurent, J.-P. Numerical Modeling of a Capacitance Probe Response. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, M. Sensitivity of Capacitance Probes to Soil Cracks Courses ENG4111 and ENG4112 Research Project. Bachelor’s Thesis, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Wei, W.; Chen, L.; Jia, F.; Mo, B. Spatial Variations of Shallow and Deep Soil Moisture in the Semi-Arid Loess Plateau, China. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 16, 3199–3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myneni, R.B.; Hall, F.G.; Sellers, P.J.; Marshak, A.L. The Interpretation of Spectral Vegetation Indexes. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1995, 33, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.; Brady, N. The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0133254488. [Google Scholar]

- Sentek. Probe Configuration Utility User Guide; Sentek Technologies: Stepney, Australia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kubat, M.; Holte, R.C.; Matwin, S. Machine Learning for the Detection of Oil Spills in Satellite Radar Images. Mach. Learn. 1998, 30, 195–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabro, J.; Leib, B.; Jabro, A. Estimating Soil Water Content Using Site-Specific Calibration of Capacitance Measurements from Sentek EnviroSCAN Systems. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2005, 21, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SUHET Sentinel-2 User Handbook. Available online: https://sentinels.copernicus.eu/documents/247904/685211/Sentinel-2_User_Handbook (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, P.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Anand, G.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G.M. LSTM-Based Encoder-Decoder for Multi-Sensor Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.00148. [Google Scholar]

- Stock, A.; Subramaniam, A. Iterative Spatial Leave-One-out Cross-Validation and Gap-Filling Based Data Augmentation for Supervised Learning Applications in Marine Remote Sensing. GISci. Remote Sens. 2022, 59, 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durner, W.; Flühler, H. Soil Hydraulic Properties. In Encyclopedia of Hydrological Sciences; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780470848944. [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara, S.; Funakawa, S.; Shinjo, H.; Kosaki, T. Short-Term Dynamics of Soil Organic Matter and Microbial Biomass after Simulated Rainfall on Tropical Sandy Soil. In Management of Tropical Sandy Soils for Sustainable Agriculture; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Antonini, A.S.; Tanzola, J.; Asiain, L.; Ferracutti, G.R.; Castro, S.M.; Bjerg, E.A.; Ganuza, M.L. Machine Learning Model Interpretability Using SHAP Values: Application to Igneous Rock Classification Task. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil Site Reference Name | Sand | Silt | Clay | Soil Texture Class |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiszavasvari_01 | 37.6 | 38.8 | 23.6 | Loam |

| Tiszavasvari_02 | 32.7 | 43.2 | 24.2 | Loam |

| Tiszavasvari_03 | 34.4 | 41.6 | 24.0 | Loam |

| Tiszavasvari_04 | 64.8 | 23.9 | 11.3 | Sandy Loam |

| Tiszavasvari_05 | 25.9 | 46.9 | 27.3 | Clay Loam |

| Tiszavasvari_17 | 56.3 | 26.2 | 17.5 | Sandy Loam |

| Somodor_4 | 59.4 | 21.7 | 19.1 | Sandy Loam |

| Somodor_13 | 52.2 | 26.3 | 21.5 | Sandy Clay Loam |

| Somodor_21 | 69.0 | 18.6 | 12.4 | Sandy Loam |

| Urbán_4 | 12.4 | 27.3 | 60.3 | Clay |

| Urbán_17 | 51.3 | 22.1 | 26.6 | Sandy Clay Loam |

| Tépe_06 | 30.3 | 40.4 | 29.3 | Clay Loam |

| Tépe_08 | 38.0 | 39.9 | 22.2 | Loam |

| Tépe_09 | 45.6 | 27.3 | 27.2 | Sandy Clay Loam |

| Tépe_12 | 47.7 | 20.9 | 31.5 | Sandy Clay Loam |

| Tépe_13 | 39.2 | 32.1 | 28.8 | Clay Loam |

| Magyaregregy_10 | 60.9 | 19.8 | 19.4 | Sandy Loam |

| Magyaregregy_11 | 48.6 | 27.7 | 23.7 | Sandy Clay Loam |

| Magyaregregy_14 | 47.1 | 34.9 | 18.0 | Loam |

| Kunszentmárton_7 | 21.0 | 44.5 | 34.5 | Clay Loam |

| Kunszentmárton_18 | 22.0 | 30.2 | 47.7 | Clay |

| Kunszentmárton_19 | 25.3 | 32.6 | 42.1 | Clay |

| Matyo_12 | 32.5 | 31.4 | 36.1 | Clay Loam |

| Matyo_17 | 26.6 | 27.5 | 45.9 | Clay |

| Matyo_21 | 27.5 | 31.9 | 40.6 | Clay |

| Feature | Depth (cm) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | - | The temperature measurement in the sensor is typically performed using a thermistor or resistance temperature detector (RTD), both of which offer high-precision detection of soil temperature fluctuations. Soil temperature, influencing evapotranspiration, soil thermal regime, and root activity, and indirectly affecting soil moisture dynamics [28]. |

| T_10_Days_Avr | - | A moving window average of temperature, where the mean temperature is computed continuously over a sliding 10-day period. This approach smooths short-term fluctuations and highlights progressive trends in temperature variation. |

| Humidity | - | The capacitance-based sensors within the sensor detect changes in soil dielectric properties, which are strongly influenced by soil humidity and moisture levels. Higher soil moisture content correlates with higher soil humidity, reducing evaporation rates and influencing plant water uptake efficiency. |

| H_10_Days_Avr | - | A 10-day moving window average humidity, calculated by averaging humidity values over a continuously updating 10-day period. This moving average method smooths short-term fluctuations while capturing long-term trends in humidity variation. |

| SF | 10, 20, 30 | The scaled frequency (SF) is derived from the raw frequency output of the sensor and is normalized to minimize variations caused by sensor drift, environmental conditions, and soil texture differences [17]. SF measured at multiple depths, reflecting dielectric properties of the soil–water matrix and serving as a proxy for soil moisture state. |

| SF_30/SF_10 | 10–30 | Ratio between deep and shallow SF, capturing vertical redistribution of soil moisture and infiltration behavior within the soil profile. A higher SF_30/SF_10 ratio suggests that the deeper layer has relatively higher SF values than the upper layer. |

| SM | 10, 20, 30 | The Sentek probe determines soil moisture content using SF, which is derived from the sensor’s raw frequency response influenced by the dielectric properties of the soil-water matrix [28]. Volumetric soil moisture content at different depths, representing instantaneous water availability within the root zone and deeper soil layers. |

| Max SM, Min SM, Range SM | 10, 20, 30 | It is a 5-day moving window of the maximum, the minimum and the range of SM at different depths. Maximum soil moisture value, identifying wetting events associated with rainfall or irrigation. Minimum soil moisture value, reflecting short-term drying driven by evapotranspiration and drainage processes. The range is difference between maximum and minimum soil moisture, providing insights into moisture dynamics, infiltration efficiency, and evaporation rates. |

| Range SM | 10–20, 10–30, 20–30 | Range SM is the difference in soil moisture between depths, characterizing vertical moisture gradients related to infiltration, percolation, and root water uptake. |

| Range Range SM | 10–20, 10–30, 20–30 | A 5-day moving window of the difference between the range SM at different depths, highlighting depth-dependent responses to hydrological processes. A higher value indicates that moisture fluctuations at upper depth are more pronounced compared to deeper depth. Conversely, a lower value suggests more uniform moisture fluctuations between the two depths, indicating consistent infiltration, stable deep moisture retention, or minimal difference in drying rates. |

| CDiff Slope | 10, 20, 30 | Central difference slope of soil moisture time series, capturing rapid temporal changes indicative of infiltration pulses, drainage, or drying events. |

| Season_value | - | The Season_value is a normalized time variable that represents the progression of a specific seasonal interval, ranging from 30 January at 23:00 to 15 July at 23:00. This variable provides a continuous, scaled representation of time, where 30 January, 23:00 is assigned a value of 0 (seasonal start) and 15 July, 23:00 is assigned a value of 1 (seasonal end). Every hour within this interval is assigned a proportional value between 0 and 1, ensuring a smooth, normalized transition across the time range. |

| Day_Night | - | The Day_Night variable is a normalized, scaled variable representing a fixed daily time interval. This period spans 5 h, and the normalization is applied consistently to every day in the dataset, ensuring a standardized representation of night-time conditions. 11 PM is assigned a value of 0 and 4 AM is assigned a value of 1. This approach allows Day_Night to be used as a continuous feature in modeling diurnal variations in environmental conditions. |

| NDVI | - | Vegetation index derived from Sentinel-2 imagery, serving as an indirect indicator of soil moisture availability through vegetation condition and stress response. |

| Texture Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clay | 0.33 | 0.2 | 0.25 | 5 |

| Loam | 0.56 | 0.75 | 0.64 | 12 |

| Sandy | 0.6 | 0.43 | 0.5 | 7 |

| Overall accuracy | — | — | 0.54 | 24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rajhi, M.; Deak, T.; Dobos, E. Non-Invasive Soil Texture Prediction Using Machine Learning and Multi-Source Environmental Data. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010008

Rajhi M, Deak T, Dobos E. Non-Invasive Soil Texture Prediction Using Machine Learning and Multi-Source Environmental Data. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleRajhi, Mohamed, Tamas Deak, and Endre Dobos. 2026. "Non-Invasive Soil Texture Prediction Using Machine Learning and Multi-Source Environmental Data" Soil Systems 10, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010008

APA StyleRajhi, M., Deak, T., & Dobos, E. (2026). Non-Invasive Soil Texture Prediction Using Machine Learning and Multi-Source Environmental Data. Soil Systems, 10(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010008