Effects of Magnetized Saline Irrigation on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salinity, Nutrient Distribution, and Enzyme Activity: Based on the Interaction Between Salinity and Magnetic Field Strength

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Soil Properties

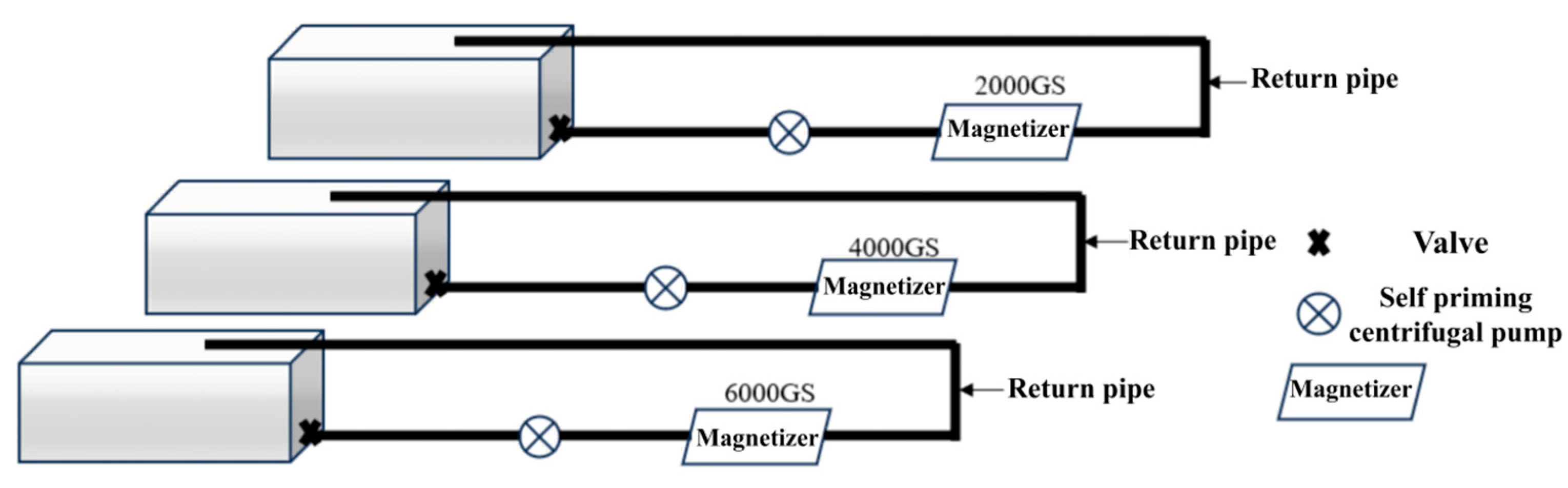

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Soil Column Setup and Irrigation Protocol

2.4. Soil Sampling and Sample Preparation

2.5. Measurement of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

2.5.1. Aggregate Stability

2.5.2. Salinity and Ions

2.5.3. Nutrients and Enzymes

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Soil Aggregation and Structural Stability

3.2. Soil pH and Electrical Conductivity

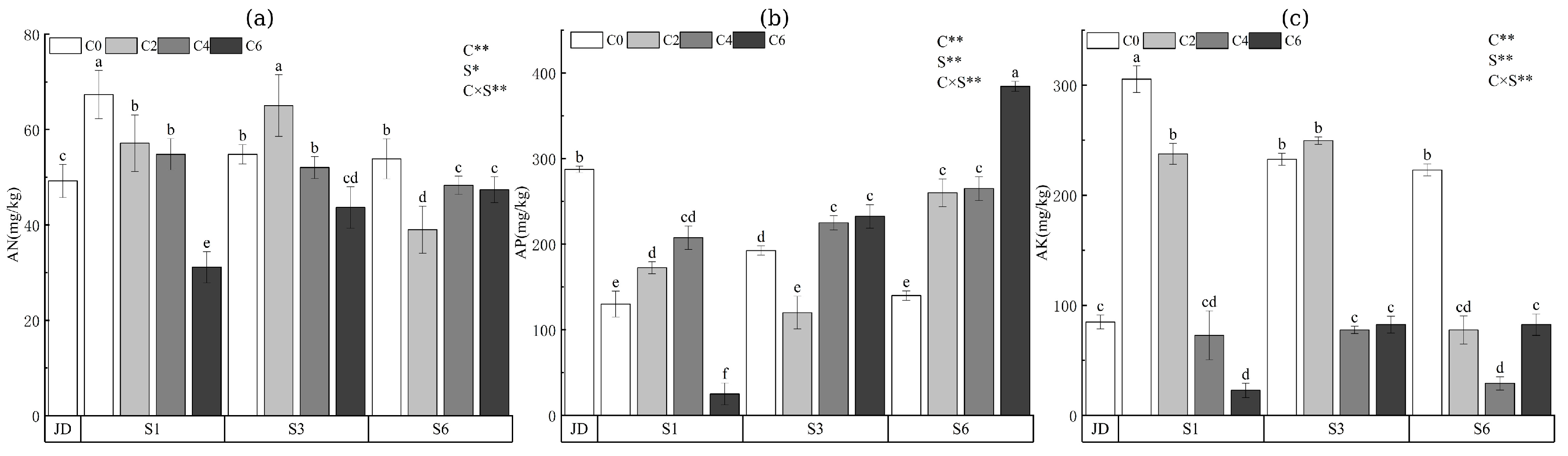

3.3. Soil Nutrients

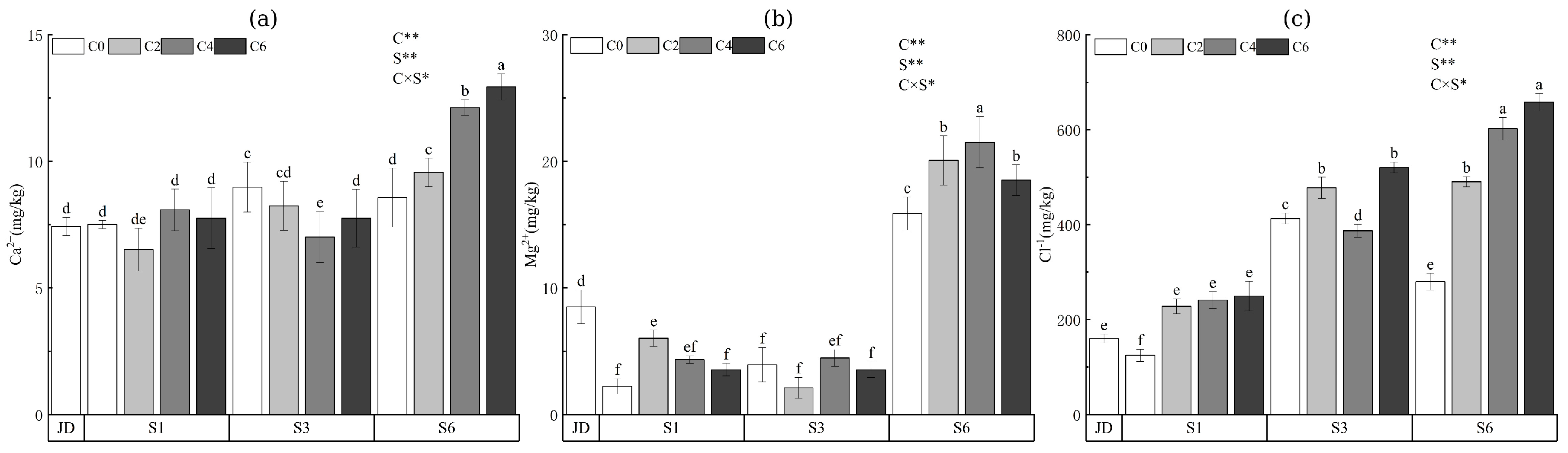

3.4. Soil Salinity Ion Composition and Characteristics

3.5. Linkages Between Soil Matrix Ions and Soil Aggregate Stability

3.6. Effects of Magnetized Saltwater on Soil Enzyme Activity

3.7. Structural Equation Model–Based Analysis of Factors Affecting Soil Aggregate Stability

4. Discussion

4.1. Magnetized Saltwater Irrigation Affects the Soil Aggregate Stability

4.2. Magnetized Saltwater Irrigation Affects Soil Physicochemical Properties

4.3. Magnetized Saline Irrigation Influences Soil Nutrient Availability and Dynamics

4.4. Magnetized Saltwater Irrigation Affects the Soil Salt Ions Distribution in Soil Aggregates

4.5. Magnetized Saltwater Irrigation Affects the Soil Enzyme Activities

4.6. Possible Synergistic Effects on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salt Ion Distribution, and Soil Enzyme Activity Under Magnetized Saline Irrigation

5. Conclusions

- In terms of scientific novelty and mechanisms, the work provides a quantitative and integrated understanding of the multi-scale processes involved. Structural equation modeling (SEM) showed that the enhancement of soil aggregate stability was mainly driven by indirect pathways, in which EC-associated flocculation/dispersion processes (consistent with DLVO-type colloidal interactions) and enzyme-mediated organic matter turnover acted as key mediators. This helps to open the “black box” of magnetic treatment by supplying quantitative evidence for the cascade of physical, chemical and biological responses.

- From an application perspective, the study proposes salinity-dependent optimization strategies. A moderate-salinity (3 g L−1), moderate-magnetic-field (0.4 T) regime emerged as an optimal, balanced strategy for overall soil health, simultaneously improving aggregate stability and maintaining high levels of multiple enzyme activities. In contrast, the high-salinity, high-magnetic-field treatment (C6-6) produced the strongest structural improvements, highlighting its potential for targeted remediation under more severe salinity.

- Mechanistic insights indicate that magnetic treatment may shift soil-solution physicochemical conditions (particularly EC and pH) and ion redistribution, which together provide a plausible linkage between soil structure and biological functioning in saline soils. Future research should prioritize long-term field trials across diverse soil types, and explicitly couple these responses to crop productivity and microbial community dynamics beyond enzyme activity. Such efforts are essential to refine magnetized saline irrigation as a sustainable, non-chemical management option for mitigating soil degradation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MSW | Magnetized saline water |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| JD | Initial soil |

| C | Magnetic field intensity |

| S | Salinity level |

| C × S | Interaction between magnetic intensity and salinity |

| R0.25 | Percentage of mechanically stable aggregates larger than 0.25 mm |

| MWD | Mean weight diameter of soil aggregates |

| GMD | Geometric mean diameter of soil aggregates |

| PH | Soil pH |

| EC | Electrical conductivity of soil solution |

| AN | Soil ammonium nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| AK | Available potassium |

| Urease | Soil urease activity |

| Sucrase | Soil sucrase activity |

| ALP | Alkaline phosphatase activity |

References

- Sodaeizadeh, H.; Hokmollahi, F.; Ghasemi, S.; Sadeghian, M.; Tarrah, S. Cyanobacteria inoculation mitigates salinity stress by regulating plant growth, photosynthetic performance, elemental concentrations and yield in wheat. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 180, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F.; Sodaeizadeh, H.; Yazdani-Biouki, R.; Hakimzadeh-Ardakani, M.-A.; Kamali Aliabadi, K. Effect of bio-priming on morphological, physiological and essential oil of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L.) under salinity stress. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 167, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Blanchy, G.; Cornelis, W.; Garré, S. Changes in soil hydraulic and physio-chemical properties under treated wastewater irrigation: A meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 295, 108752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ogaidi, A.A.M.; Wayayok, A.; Rowshon, M.K.; Abdullah, A.F. The influence of magnetized water on soil water dynamics under drip irrigation systems. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 180, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, G.J.; Fine, P.; Goldstein, D.; Azenkot, A.; Zilberman, A.; Chazan, A.; Grinhut, T. Long term irrigation with treated wastewater (TWW) and soil sodification. Biosyst. Eng. 2014, 128, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Akhras, M.-A.H.; Al-Quraan, N.A.; Abu-Aloush, Z.A.; Mousa, M.S.; AlZoubi, T.; Makhadmeh, G.N.; Donmez, O.; Al Jarrah, K. Impact of magnetized water on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat and barley. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wu, P.; Zhang, L.; Hang, Y.; Wei, Y. Effects of irrigation-mediated continuously moist and dry-rewetting pattern on soil physicochemical properties, structure and bacterial community. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 205, 105767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Ye, S.; Peng, Y.; Liang, C. Effect of magnetic water irrigation on the improvement of salinized soil and cotton growth in Xinjiang. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 248, 106784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelghany, A.E.; Abdo, A.I.; Alashram, M.G.; Eltohamy, K.M.; Li, J.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, F. Magnetized saline water irrigation enhances soil chemical and physical properties. Water 2022, 14, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, G.; Saxena, C.; Rajwade, Y. Magnetic treatment of irrigation water: Its effect on water properties and characteristics of eggplant (Solanum melongena). Emir. J. Food Agric. 2022, 34, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pang, J.; Hamani, A.K.M.; Xu, C.; Dang, H.; Cao, C.; Wang, G.; Sun, J. Impacts of saline water irrigation on soil respiration from cotton fields in the North China Plain. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Tian, H.; Tan, X.; Megharaj, M.; He, Y.; He, W. Distribution of soil nutrients and enzyme activities in different aggregates under two sieving methods. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, E.M.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil aggregate isolation method affects measures of intra-aggregate extracellular enzyme activity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 69, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000; ISBN 978-7-109-06644-1. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.Y. Soil Enzyme and Its Research Methods; Chinese Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel, Y. Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, K.A.H.; Ahmed, M.A.; El-Sayed, H.A.M. Effect of magnetic irrigation saline water and pre-sowing of grains treated with magnetic field on saline soil fertility and wheat productivity and quality. Asian J. Adv. Agric. Res. 2023, 23, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, Y.; Hegab, S.; Youssef, M.; Abd El-Gawad, A. Effects of magnetized saline irrigation water and fertilizers on soil prosperities and wheat productivity. Arch. Agric. Sci. J. 2023, 6, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, T.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, M.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H.M. The higher relative concentration of K+ to Na+ in saline water improves soil hydraulic conductivity, salt-leaching efficiency and structural stability. Soil 2023, 9, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Zhang, A.; Zhu, C.; Dang, H.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, J.; Cao, C. Saline water irrigation changed the stability of soil aggregates and crop yields in a winter wheat–summer maize rotation system. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Liu, X. The effect of soil salt content and ionic composition on nitrification in a Fluvisol of the Yellow River Delta. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 235, 105907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, P. Effects of salinity of magnetized water on water–salt transport and infiltration characteristics of soil under drip irrigation. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, H.; Mostafa, H.; El-Ansary, M.; Awad, M.; Sultan, W. Magnetization treatment effect on some physical and biological characteristics of saline irrigation water. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, M.; Zhao, Q.; Qiao, Y.; Ma, Y. Magnetized saline water drip irrigation alters soil water-salt infiltration and redistribution characteristics. Water 2024, 16, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amor, H.; Elaoud, A.; Ben Hassen, H.; Ben Salah, N.; Masmoudi, A.; Elmoueddeb, K. Characteristic study of some parameters of soil irrigated by magnetized waters. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Tian, J.; Yan, X. Effects of mineralization degree of irrigation water on yield, fruit quality, and soil microbial and enzyme activities of cucumbers in greenhouse drip irrigation. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Du, S.; Guo, H.; Min, W. Long-term saline water drip irrigation alters soil physicochemical properties, bacterial community structure, and nitrogen transformations in cotton. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 182, 104719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wu, S.; Jiao, X.; Guo, W.; Adeloye, A.J.; Tianao, W. Effects of magnetized saline water irrigation on maize photosynthesis, growth and WUE under reduced phosphorus fertilizer. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, R.; Wang, Z. Rationale saline-water irrigation also serves as enhancing soil aggregate stability, regulating carbon emissions, and improving water use efficiency in oasis cotton fields. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 223, 120144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Tian, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Specific cation effects on soil water infiltration and soil aggregate stability–Comparison study on variably and permanently charged soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 247, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gao, R.; Ndzana, G.M.; An, H.; Huang, J.; Liu, R.; Du, L.; Kamran, M.; Xue, B. Nutrient addition affects stability of soil organic matter and aggregate by altering chemical composition and exchangeable cations in desert steppe in northern China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 1430–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, B.; Feng, H.; Siddique, K.H.M. Adverse effects of Ca2+ on soil structure in specific cation environments impacting macropore-crack transformation. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 302, 108987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Du, Z.; Guo, K.; Liu, X. Irrigation with freezing saline water for 6 years alters salt ion distribution within soil aggregates. J. Soils Sediments 2019, 19, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Ning, S.; Wei, K.; Hu, X. Effects of magnetized ionized water and Bacillus subtilis on water and salt transport characteristics and ion composition in saline soil. Irrig. Drain. 2025, 74, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Shao, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, X. Soil enzymes as indicators of saline soil fertility under various soil amendments. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 237, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, B.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X. PhoD harboring microbial community and alkaline phosphatase as affected by long term fertilization regimes on a calcareous soil. Agronomy 2023, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Zhou, C.; Li, H.; Zhou, Z.; Ni, G.; Yin, X. Effects of rumen microorganisms on straw returning to soil at different depths. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2023, 114, 103454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, C.; Hernández, T. Influence of salinity on the biological and biochemical activity of a calciorthird soil. Plant Soil 1996, 178, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horchani, F.; Bouallegue, A.; Namsi, A.; Abbes, Z. Exogenous application of ascorbic acid mitigates the adverse effects of salt stress in two contrasting barley cultivars through modulation of physio-biochemical attributes, K+/Na+ homeostasis, osmoregulation and antioxidant defense system. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 70, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; González-Espíndola, L.Á.; Jacobo-Salcedo, M.D.R.; Gramillo-Ávila, I.; Miranda-Rojas, J.A. Magnetized saline water modulates soil salinization and enhances forage productivity: Genotype-specific responses of Lotus corniculatus L. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, T.; Bao, Y.; Tang, Q.; Li, Y.; He, X. The impacts of the hydrological regime on the soil aggregate size distribution and stability in the riparian zone of the Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Water 2023, 15, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Luo, G.; Sutanudjaja, E.H.; Hellwich, O.; Chen, X.; Ding, J.; Wu, S.; He, X.; Chen, C.; Ochege, F.U.; et al. Recent impacts of water management on dryland’s salinization and degradation neutralization. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 3240–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamza, A.H.; Shreif, M.; Abd El-Azeim, M.; Mohamed, W. Impacts of magnetic field treatment on water quality for irrigation, soil properties and maize yield. J. Mod. Res. 2020, 3, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Aggregate Size Fraction (mm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >2 mm | 1–2 mm | 0.25–1 mm | 0.053–0.25 mm | <0.053 mm | |

| JD | 0.00 ± 0.00 d | 23.92 ± 1.20 a | 41.61 ± 2.08 a | 33.51 ± 1.68 a | 0.96 ± 0.05 d |

| C0-1 | 11.90 ± 1.25 d | 11.50 ± 1.15 c | 35.10 ± 1.80 b | 35.30 ± 1.80 a | 6.20 ± 0.65 a |

| C2-1 | 18.40 ± 1.85 c | 10.20 ± 0.95 c | 32.30 ± 1.65 bc | 34.50 ± 1.75 a | 4.60 ± 0.45 b |

| C4-1 | 19.20 ± 1.90 b | 14.50 ± 1.45 b | 34.90 ± 1.75 b | 28.90 ± 1.50 b | 2.50 ± 0.30 c |

| C6-1 | 16.10 ± 1.65 bc | 12.50 ± 1.25 c | 31.80 ± 1.60 c | 35.90 ± 1.80 a | 3.70 ± 0.40 b |

| C0-3 | 18.90 ± 1.65 b | 14.20 ± 1.45 b | 36.40 ± 1.85 b | 27.90 ± 1.45 b | 2.60 ± 0.30 c |

| C2-3 | 23.20 ± 1.80 b | 15.40 ± 1.55 b | 32.50 ± 1.65 bc | 27.60 ± 1.40 b | 1.30 ± 0.20 d |

| C4-3 | 29.60 ± 2.05 a | 15.10 ± 1.55 b | 27.20 ± 1.40 d | 24.80 ± 1.30 c | 3.30 ± 0.35 b |

| C6-3 | 27.50 ± 2.00 a | 16.90 ± 1.70 b | 30.80 ± 1.55 c | 23.70 ± 1.25 c | 1.10 ± 0.15 d |

| C0-6 | 16.70 ± 1.55 bc | 14.70 ± 1.50 b | 36.20 ± 1.85 b | 29.80 ± 1.55 b | 2.60 ± 0.30 c |

| C2-6 | 22.50 ± 1.75 b | 18.20 ± 1.80 ab | 29.10 ± 1.50 cd | 28.00 ± 1.45 b | 2.20 ± 0.25 c |

| C4-6 | 26.10 ± 1.95 ab | 18.50 ± 1.85 ab | 32.60 ± 1.65 bc | 21.30 ± 1.15 c | 1.50 ± 0.20 cd |

| C6-6 | 29.90 ± 2.10 a | 18.20 ± 1.80 ab | 29.70 ± 1.50 cd | 21.00 ± 1.10 c | 1.20 ± 0.15 d |

| P (C) | <0.001 | 0.0017 | 0.025 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (S) | <0.001 | 0.0016 | 0.0049 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (C × S) | <0.001 | 0.076 | 0.034 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Soil Aggregate Stability | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | R0.25 | MWD | GMD |

| JD | 65.53 ± 1.50 d | 0.670 ± 0.030 e | 0.460 ± 0.020 f |

| C0-1 | 58.50 ± 1.20 e | 0.804 ± 0.025 d | 0.415 ± 0.015 f |

| C2-1 | 60.90 ± 1.55 de | 0.960 ± 0.040 cd | 0.484 ± 0.018 ef |

| C4-1 | 68.60 ± 1.70 cd | 1.056 ± 0.035 c | 0.588 ± 0.022 de |

| C6-1 | 60.40 ± 1.45 de | 0.925 ± 0.032 cd | 0.480 ± 0.019 ef |

| C0-3 | 69.50 ± 1.75 cd | 1.050 ± 0.040 c | 0.591 ± 0.024 de |

| C2-3 | 71.10 ± 1.80 c | 1.172 ± 0.045 b | 0.668 ± 0.026 cd |

| C4-3 | 71.90 ± 1.82 c | 1.323 ± 0.048 a | 0.719 ± 0.028 bc |

| C6-3 | 75.20 ± 1.90 b | 1.307 ± 0.047 a | 0.770 ± 0.030 b |

| C0-6 | 67.60 ± 1.65 cd | 0.994 ± 0.038 c | 0.558 ± 0.021 e |

| C2-6 | 69.80 ± 1.78 cd | 1.173 ± 0.046 b | 0.654 ± 0.025 cd |

| C4-6 | 77.20 ± 1.95 ab | 1.297 ± 0.049 a | 0.780 ± 0.031 ab |

| C6-6 | 77.80 ± 2.10 a | 1.388 ± 0.052 a | 0.838 ± 0.033 a |

| P (C) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (S) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (C × S) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Treat | Aggregates Size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| >2 mm | 1–2 mm | 0.25–1 mm | 0.053–0.25 mm | <0.053 mm | |

| JD | 0.00 ± 0.00 d | 4.88 ± 0.25 a | 5.26 ± 0.52 a | 3.72 ± 0.19 a | 3.56 ± 0.18 b |

| C0-1 | 1.81 ± 0.09 c | 2.05 ± 0.10 b | 1.58 ± 0.08 c | 3.42 ± 0.17 a | 2.33 ± 0.12 c |

| C2-1 | 2.05 ± 0.10 c | 4.75 ± 0.24 a | 1.48 ± 0.07 c | 0.83 ± 0.04 c | 7.20 ± 0.86 a |

| C4-1 | 1.65 ± 0.08 c | 3.32 ± 0.17 a | 4.14 ± 0.21 b | 4.14 ± 0.21 a | 2.51 ± 0.13 c |

| C6-1 | 9.62 ± 0.48 a | 3.19 ± 0.16 a | 2.60 ± 0.13 bc | 3.79 ± 0.19 a | 2.95 ± 0.15 c |

| C0-3 | 3.31 ± 0.17 b | 3.59 ± 0.18 a | 4.29 ± 0.21 b | 2.89 ± 0.14 b | 8.70 ± 0.99 a |

| C2-3 | 9.35 ± 0.47 a | 3.91 ± 0.20 a | 2.36 ± 0.12 bc | 1.36 ± 0.07 c | 3.08 ± 0.15 c |

| C4-3 | 5.47 ± 0.27 b | 2.46 ± 0.12 b | 4.76 ± 0.24 b | 2.81 ± 0.14 b | 3.43 ± 0.17 b |

| C6-3 | 5.28 ± 0.26 b | 3.05 ± 0.15 a | 1.57 ± 0.08 c | 1.35 ± 0.07 c | 1.96 ± 0.10 c |

| C0-6 | 0.72 ± 0.04 c | 2.15 ± 0.11 b | 2.78 ± 0.14 bc | 2.05 ± 0.10 b | 1.53 ± 0.08 c |

| C2-6 | 0.50 ± 0.03 c | 0.55 ± 0.03 c | 0.58 ± 0.03 d | 0.55 ± 0.03 c | 1.38 ± 0.07 c |

| C4-6 | 0.75 ± 0.04 c | 0.57 ± 0.03 c | 0.58 ± 0.03 d | 0.51 ± 0.03 c | 0.53 ± 0.03 d |

| C6-6 | 0.61 ± 0.03 c | 0.61 ± 0.03 c | 0.59 ± 0.03 d | 0.47 ± 0.02 c | 0.52 ± 0.03 d |

| P (C) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (S) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| P (C × S) | 0.0015 | 0.0026 | <0.001 | 0.0013 | 0.0027 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, Y.; Ai, P.; Li, F.; Heng, T.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Z.; Ma, Y. Effects of Magnetized Saline Irrigation on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salinity, Nutrient Distribution, and Enzyme Activity: Based on the Interaction Between Salinity and Magnetic Field Strength. Soil Syst. 2026, 10, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010006

Fan Y, Ai P, Li F, Heng T, Xu Y, Wang Z, Ma Z, Ma Y. Effects of Magnetized Saline Irrigation on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salinity, Nutrient Distribution, and Enzyme Activity: Based on the Interaction Between Salinity and Magnetic Field Strength. Soil Systems. 2026; 10(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Yu, Pengrui Ai, Fengxiu Li, Tong Heng, Yan Xu, Zhifeng Wang, Zhenghu Ma, and Yingjie Ma. 2026. "Effects of Magnetized Saline Irrigation on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salinity, Nutrient Distribution, and Enzyme Activity: Based on the Interaction Between Salinity and Magnetic Field Strength" Soil Systems 10, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010006

APA StyleFan, Y., Ai, P., Li, F., Heng, T., Xu, Y., Wang, Z., Ma, Z., & Ma, Y. (2026). Effects of Magnetized Saline Irrigation on Soil Aggregate Stability, Salinity, Nutrient Distribution, and Enzyme Activity: Based on the Interaction Between Salinity and Magnetic Field Strength. Soil Systems, 10(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/soilsystems10010006