Abstract

Accurate vertical distribution of fire-induced heat fluxes in the atmosphere is critical for realistic coupled fire–atmosphere simulations. In response to concerns raised by Shamsaei et al. (2023) regarding potential energy conservation issues in the WRF-SFIRE heat distribution scheme, this study first conducts a comprehensive theoretical analysis, demonstrating that the original exponential formulation exhibits negligible error under typical domain configurations. Then, it introduces a novel formulation, called the Versatile Energy-Conservative Distribution scheme, that rigorously guarantees energy conservation while providing enhanced flexibility in specifying vertical distribution profiles. The proposed method accommodates multiple profiles, including exponential, Gaussian, and gamma, and enables the independent treatment of surface and canopy heat fluxes, thereby yielding a more flexible representation of fire heat fluxes. Numerical evaluations on both fine and coarse non-uniform meshes confirm that the new formulation maintains perfect energy balance across various configurations and overcomes the limitations observed in other schemes, such as the truncated Gaussian approach. These advancements not only refute previous claims of significant energy misrepresentation but also offer a robust and flexible framework intended to improve the representation of fire–atmosphere interactions in numerical models.

1. Introduction

Coupled fire–atmosphere models are useful tools for studying wildfires at a wide range of spatial scales, ranging from local to regional [1,2,3,4]. They comprise an atmospheric model representing the atmospheric circulation (weather) and a fire model, simulating fire spread and computing fire-released heat and moisture fluxes. The fire is represented as a moving front that separates burned and unburnt areas. The front is represented using a front tracking numerical method, and advanced in time according to a rate-of-spread parameterization [5,6,7,8] that requires as input topography, wind speed and direction, as well as fuel properties, including fuel moisture content [9,10]. In the atmospheric model, the fire is represented by the sensible and latent heat fluxes added as lower boundary conditions or volume source terms in the energy balance equation. Usually, the fire model computes fire-released heat as a surface flux [ ]. This surface flux is then distributed vertically to (1) represent the vertical extent of the fire impact on the atmosphere, including radiative heating not explicitly accounted for by the fire model, (2) eliminate mesh-dependent effects when the vertical resolution is smaller than the vertical extent of the fire processes that produce the heat, and (3) improve numerical stability. Therefore, the vertical distribution schemes are designed to compute the fire-related source term for the energy equation [ ], where k is the vertical index of the considered cell. The cell k represents the volume between the vertical levels and [ AGL], and the cell size is . The distribution is a function of the elevation above the ground level, meaning m AGL. The major challenge of a vertical distribution scheme is to conserve energy, meaning satisfying the following relation:

Equation (1) can also be formulated using the proportion of surface flux distributed to an atmospheric cell, [–], satisfying the equation:

Recently, Shamsaei et al. [11] has pointed out that the vertical distribution scheme used in WRF-SFIRE was not conservative to an alarming extent. The authors claimed that “this scheme [WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme] incorrectly magnifies the heat generated from the fire as the sum of the proportions of all vertical levels is equal to ∼3.78”. This claim is concerning, as if true, it would question the analysis of all previous WRF-SFIRE and WRF-FIRE simulations that used the exponential scheme. Therefore, the work presented in this paper has a double objective: (1) to refute the claims from Shamsaei et al. [11] by examining the energy conservation properties of the original WRF-SFIRE scheme along with the other popular schemes and the new Truncated Gaussian WRF-FIRE scheme proposed by Shamsaei et al. [11], and (2) to propose a new formulation called the Versatile Energy-Conservative Distribution (VECD) scheme enabling an independent distribution of surface and canopy heat fluxes, and conserving energy.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the tested heat distribution methods and defines the configurations used for evaluating their energy conservation properties. It reviews the methods utilized by various coupled models and introduces a new formulation that allows for a flexible distribution of surface and canopy heat fluxes based on three analytical profiles. Section 3 presents the results of the energy conservation evaluation, quantifying the error of the WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme, and refuting the claims in [11] about the alleged conservation issues. Furthermore, it highlights the energy conservation properties of the multiple popular heat distribution schemes (including the truncated Gaussian scheme from [11]) for surface and canopy heat fluxes. Section 4 offers discussions of the results, while Section 5 summarizes the findings and comments on future work.

2. Methods and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Overview of Heat Distribution Schemes

This section focuses on reviewing the current methods for representing fire heat fluxes. We begin with the original WRF-SFIRE heat distribution method, which was criticized by [11]. We analyze its energy conservation properties and compare it with other methods, including the Truncated Gaussian scheme (TG scheme) proposed there.

2.1.1. Exponential Decay-WRF-SFIRE and Derivatives

Originally, WRF-SFIRE, WRF-FIRE, and CAWFE shared the same exponential distribution method [12,13,14,15]. More recently, UFS-FIRE [16] also adopted the same exponential decay scheme. The scheme is intended to represent the heat exchange between the fire and the atmosphere. Since the coupled fire–atmosphere models with parameterized fire progression do not explicitly treat radiative and sensible heat fluxes, the scheme provides a bulk heat flux representation accounting for both heat transfer modes. Another role of the heat distribution scheme is to stabilize the atmospheric model numerically by reducing the strong thermal gradients that the model cannot handle. The energy conservation equation of the WRF model can be written as:

where [] is the dry air mass per unit area, [] is the moist potential temperature, [ ] is the air density, [ ] is the specific heat capacity, and [ ] represents the other source terms in the energy conservation equation. WRF-SFIRE defines the distribution factor [–] as:

where [] is the extinction depth. Then, the source term used in the energy conservation equation is defined as:

To preserve the physical significance of the parametrization, the difference must be negative, requiring a profile that decreases with height.

2.1.2. The Truncated Gaussian Scheme from WRF-FIRE 4.6.1

Recently, a new vertical distribution scheme, called the Truncated Gaussian (TG scheme), has been proposed by Shamsaei et al. [11] to replace the exponential method and is currently in use in WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 [17]. The TG scheme proposes to distribute the heat flux in a non-monotonic way with a maximum at the canopy height level. This new scheme (originally Equation (9) in Shamsaei et al. [11]) is formulated as:

where is the proportion of heat flux assigned to the k-th cell, [AGL] is the height of the k-th vertical level, [AGL] is the peak heat release height, [] is the heat extinction depth, [] is the k-th cell size, and [] is a truncated Gaussian probability density function. represented originally in their Equation (6), is defined as:

The functions and are smooth approximations of the standard Gaussian probability density function and the cumulative distribution function, respectively. Finally, the source term calculated using the TG scheme is defined as .

However, the implementation of the TG scheme in the WRF-FIRE code [17] is very different from the scheme presented above. It uses the same principles as the original exponential profile, i.e., calculation of the distribution factors , and then differentiation of these factors. The reformulated equation used in WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 can be written as:

where [] is the truncated Gaussian function described in Shamsaei et al. [11], is the peak heat release elevation [AGL]. Then the distribution factors are used in Equation (5) to compute the final source term.

Therefore, here we will evaluate both versions of the TG scheme. The one described by Shamsaei et al. [11] will be referred to as TG Shamsaei, while the one implemented in WRF-FIRE will be referred to as TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1.

2.1.3. MesoNH-ForeFire

ForeFire [18,19,20] is coupled to MesoNH using surface boundary conditions. The heat fluxes are not distributed vertically but are concentrated in the first atmospheric cell. By definition, this scheme is perfectly conservative but lacks physical consistency, as the energy is released in one cell regardless of the actual depth of the flaming zone, and the exponential character of the fire heat fluxes due to the radiation is not accounted for.

2.1.4. MesoNH-Blaze

MesoNH-Blaze [21,22] uses an exponential profile to distribute sensible and latent heat fluxes in the atmosphere. The method is designed to conserve energy (Equation II.19 in [22]) and uses a principle similar to the formulation presented in this paper (Equation II.20 in [22]). However, it is limited to surface fluxes (cannot be used for canopy fluxes) and supports only an exponential profile.

2.2. Introduction of New Versatile Energy-Conservative Distribution Scheme

To address the limitations of existing vertical heat flux distribution schemes in coupled fire–atmosphere models, the Versatile Energy-Conservative Distribution (VECD) scheme was developed. It addresses the limitations of traditional methods, like the exponential decay scheme used in WRF-SFIRE, which are not suitable for distributing elevated heat fluxes from burning canopies, and the issues with energy conservation of the recently proposed Truncated Gaussian (TG). The VECD, as shown later, conserves energy across both coarse and fine meshes while offering greater flexibility through the customizable analytical profiles (exponential, Gaussian, gamma) and independent treatment of surface and canopy heat fluxes.

In the VECD method, the surface flux is distributed between a minimal elevation and a maximum elevation , where is the domain top height and N is the number of cells in the vertical direction. The scheme computes the distribution coefficients [] such that . In order to rigorously satisfy the energy conservation, Equation (1), the distribution coefficients must follow:

The distribution profile [–] is defined as:

where [–] is a vertical distribution profile defined such that , and is the box function equal to one between and , and zero otherwise. This formulation guarantees that . By defining the distribution coefficient as:

the energy conservation, shown in Equation (9), is satisfied. To calculate the integral, we introduce the primitive, i.e., the indefinite integral, of as with the constant in the primitive set to zero, as it will cancel out in the expression of the distribution coefficient later. Then, the coefficient is computed as:

This formulation guarantees the energy conservation between the surface heat flux and the source term in the energy conservation equation of the atmospheric model. To improve the flexibility of this method as compared to others, it leverages three different distribution profiles (functions): (1) the exponential profile, (2) the Gaussian profile, and (3) the gamma profile, associated with three expressions for the primitive of , to be used in Equation (12).

2.2.1. The Exponential Profile

The exponential profile is a function of parameters , with the extinction depth [], defined as:

This function satisfies the energy conservation criteria , and the primitive is given by:

2.2.2. The Gaussian Profile

The Gaussian profile is a function of the parameters , where [ AGL] is the elevation of the maximum heat flux, . The Gaussian profile is defined as:

where is the Gauss error function. The primitive of , is defined by:

2.2.3. The Gamma Profile

The gamma profile as a function of parameters , is defined as:

The maximum of this profile occurs at . The primitive of , is defined by:

2.3. Addition of Canopy Heat Fluxes

The addition of canopy fuel consumption aims to enhance the representation of fire heat release under crowning conditions. In WRF-SFIRE, the computation of heat fluxes as part of the crown fire module is currently being developed. The proposed scheme, therefore, is a prerequisite for its implementation. To be able to represent the transition between surface and crowning fires, canopy heat fluxes and surface heat fluxes are computed independently. They are then aggregated in Equation (5), written as:

and use distribution factors computed from Equation (4).

On the contrary, in the WRF-FIRE code (which lacks the crowning model) [17], when the TG scheme is used, surface and canopy fluxes are aggregated before being distributed vertically. First, separate distribution factors are calculated:

where is calculated using Equation (8). Then, the source term is computed as:

Shamsaei et al. [11] proposed scheme does not specify any special treatment for canopy heat fluxes. We consider that they aggregate surface and canopy heat fluxes before distributing them.

In contrast, the VECD scheme distributes surface and canopy fluxes independently using distinct vertical profiles. Specifically, the new scheme (Equation (23)) uses an exponential profile for surface fuel and a gamma profile for canopy fuel, with parameters linked to canopy properties. This implementation results in a more realistic positioning of canopy heat fluxes that can be elevated while preserving the original distribution of surface heat fluxes concentrated near the ground.

2.4. Evaluation Configurations

First, we perform the analytical analysis of the error in the WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme. Then, to evaluate the accuracy of the methods presented in this paper, several tests are performed: (1) fine non-uniform mesh with surface flux only, (2) coarse non-uniform mesh with surface flux only, and (3) fine non-uniform mesh with surface and canopy fluxes. The VECD scheme is compared to the WRF-SFIRE original exponential decay, both Truncated Gaussian schemes (from Shamsaei et al. [11] and from WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 [17]), as well as the MesoNH-Blaze exponential scheme.

2.4.1. Fine Non-Uniform Mesh with Surface Flux Only

The fine mesh, with cells, is representative of high-resolution simulations. The cell size is smaller than the characteristic distribution height used in the setup. The first cell size is m, with an expansion ratio of 1.03. The top of the domain is then 377 . The surface heat flux is set to 30 , with set to 0 as we consider heat flux from the surface, and set to 250 so the effect of trimming the heat flux to a certain height is visible. The extinction depth, , is set to 50 as the usual value used in WRF-SFIRE, and no canopy flux is added. The height of maximum heat flux is set to 25 for both TG and VECD-gaussian schemes, as it is the value used in Shamsaei et al. [11].

2.4.2. Coarse Non-Uniform Mesh with Surface Flux Only

The coarse mesh, with cells, is representative of large-scale simulations. The cell size is greater than the characteristic distribution height . The first cell size is m, with an expansion ratio of 1.05. The top of the domain is at 7852 . The coarse mesh uses the same heat flux configuration as the fine mesh (Section 2.4.1).

2.4.3. Fine Non-Uniform Mesh with Surface and Canopy Flux

The fine mesh configuration is used as described in Section 2.4.1. The surface heat flux is set 30 , and the canopy heat flux is set 50 . For the canopy flux, is set to , the canopy top height is 40 , and is set to 250 so the effect of trimming the heat flux to a certain height is visible.

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Analysis of the Error of the WRF-SFIRE Exponential Profile

The WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme (Section 2.1.1) can be retrieved using the VECD formalism with the exponential profile (Section 2.2.1) using and , leading to . By simplifying Equation (14) with the values of and , the WRF-SFIRE scheme can be written using the VECD formalism as:

In this context, the energy conservation equation can be simplified by telescoping the sum:

Using the previous expression, the relative error [%] on the energy conservation (Equation (9)) is:

Therefore, the energy is not conserved because the domain extension is limited, i.e., . In WRF-SFIRE, a typical value of is 50 . For simulations with the top of the domain at 1000 to 15 AGL, the expected error would be between % and %. Even in a more extreme case corresponding to the tested configuration with the model top at 377 m and the extinction depth at 50 m, this error would be %. It has to be noted that this error is always negative, meaning the energy injected into the atmosphere is always underestimated.

3.2. Energy Conservation Evaluation for Surface Flux Only

3.2.1. Fine Non-Uniform Mesh

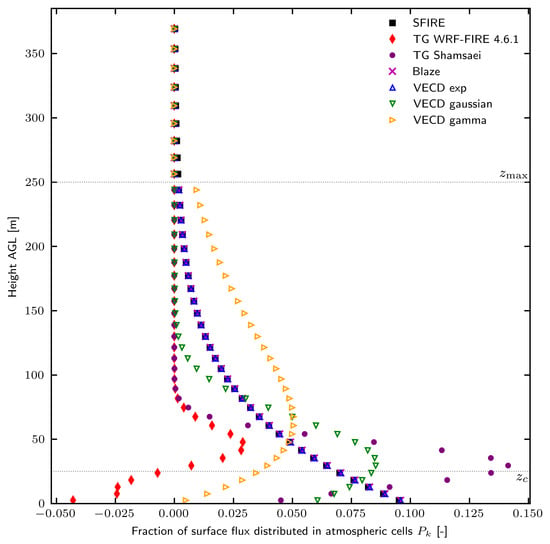

This test represents a scenario of high-resolution simulations with the depth of the first model layer below the extinction depth. Figure 1 shows the vertical distribution of the surface flux as a proportion of the surface flux for each cell according to the four tested schemes: the original SFIRE scheme, the truncated Gaussian (TG) scheme by Shamsaei et al. [11] and its implementation in WRF-FIRE 4.6.1, and the proposed VECD scheme using three profiles (exponential, Gaussian and gamma).

Figure 1.

Proportion of surface flux distributed to atmospheric cells as a function of height for the different schemes evaluated, calculated on the fine mesh.

The three exponential distribution schemes (SFIRE, Blaze, and VECD exponential) are very similar. The SBlaze and VECD exponentials show a slightly higher flux than SFIRE near the surface. However, they are null above the height. SFIRE does not have a maximum height parameter and continues to inject heat above the height. The TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme produces negative heat flux values near the surface. The proportion increases with height with a maximum around 50 and then decreases to 0 before 100 . The TG Shamsaei scheme has a correct Gaussian shape. It shows the highest peak with almost 15% of the surface flux injected in one cell. It is 65% more than the maximum of the VECD Gaussian profile. All the energy is injected in the first 100 of the model domain. The VECD Gaussian scheme generates a Gaussian profile with a maximum flux slightly above the maximum flux height . This offset will be discussed in the discussion section. Compared to the other VECD profiles, this profile distributes all the energy over the shallowest atmospheric layer (about 150 ). The gamma profile, on the other hand, produces the distribution with the smallest flux close to the surface, with less than 1% of the heat flux injected at the first level, but the highest peak flux height, at around 60 . It also has the highest heat flux value at the maximum injection height .

Table 1 shows each scheme’s energy conservation errors. The relative error on the SFIRE scheme’s energy conservation is small (−0.05%), consistent with theoretical predictions from Section 3.1. The Blaze scheme produces a conservative distribution with a null error (machine precision errors are noted as 0). Due to the large negative values of the TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme, it is the worst scheme studied, with only 2.3% of the original heat flux injected in the atmosphere, which corresponds to 677 instead of 30,000 . The TG Shamsaei scheme shows better energy conservation properties compared to its implementation with 3.6% error, which corresponds to 31.1 . It is the only distribution that injects more energy than expected. Despite better conservation than the implemented version, it performs worse than the original exponential scheme. All VECD profiles are strictly energy conservative with a null relative error in the energy conservation.

Table 1.

Relative error on energy conservation for the evaluated schemes.

3.2.2. Coarse Non-Uniform Mesh

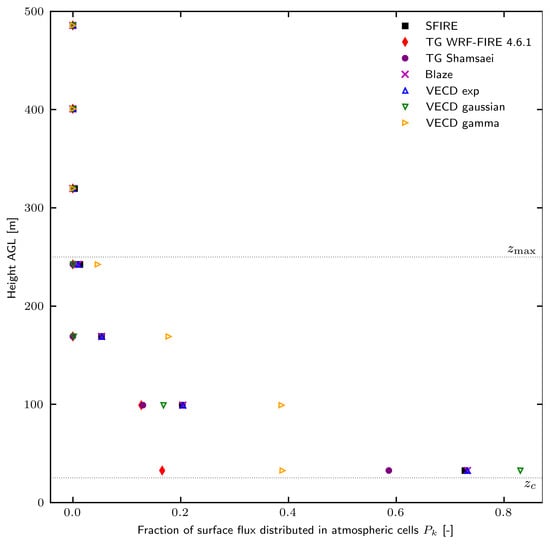

This case corresponds to a scenario of coarse-resolution simulations in which the height of the first cell centroid is above the peak flux height parameter . Figure 2 shows the vertical distribution of the surface flux as the proportion of the surface flux for each cell under such conditions.

Figure 2.

Same as Figure 1 for the coarse mesh.

The three exponential profiles (SFIRE, Blaze and VECD exp) produce very similar vertical distributions. In all these schemes, the amount of injected heat decreases exponentially as the height increases.

However, the remaining schemes display substantial differences. The VECD Gaussian profile concentrates over 80% of the original surface flux in the first atmospheric level, resulting in the highest near-surface heat injection. In contrast, the TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme injects less than 20% of the surface flux at this level, making it the least concentrated near the ground. The TG Shamsaei scheme distributes less heat at each level than the exponential schemes. Meanwhile, the VECD gamma profile distributes heat higher in the atmosphere than the other profiles, producing a more elevated heat injection pattern.

The error in energy conservation for these schemes is shown in Table 1. All schemes, except the TG schemes, show good energy conservation with negligible error (machine precision errors are noted as 0). However, the TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme significantly underestimates heat fluxes, distributing only 29.3% of the total heat flux. This error corresponds to an effective intensity of 8.80 instead of 30 . The TG Shamsaei scheme also significantly underestimates heat fluxes, with an effective intensity of 21.5 .

3.3. Energy Conservation Evaluation for Surface and Canopy Fluxes

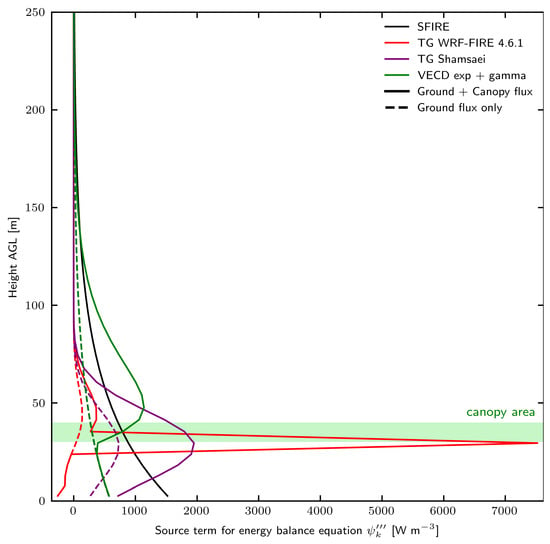

In this section, we focus on a scenario of surface and aerial fuel consumption when both the surface and canopy heat fluxes must be accounted for. Figure 3 shows the vertical distribution of the surface flux as the proportion of the surface flux for each cell. The canopy region is colored light green. The results of ground flux only (the same as in Figure 1) are displayed as a dashed line. The distributions with added canopy flux are shown in a solid line.

Figure 3.

The source term for the energy balance equation for the WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme (black), the TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme (red), the TG Shamsaei scheme (purple), and the VECD exponential + gamma scheme (green). The solid line represents the vertical distribution with canopy and ground heat flux. The dashed line represents the distribution with ground flux only.

When canopy flux is added to the SFIRE scheme, the energy is mainly added near the surface. The exponential profile distributes the heat regardless of the canopy geometry, which in reality controls the height at which heat is released. The TG WRF-FIRE scheme adds some energy around the canopy area but shows a significant discontinuity at the canopy bottom level. The peak heat flux calculated by the TG WRF-FIRE scheme is almost five times higher than the maximum flux given by the SFIRE scheme. Aside from this discontinuity, the addition of canopy heat fluxes does not significantly change the overall shape of the profile above the canopy, which remains similar to the surface TG WRF-FIRE scheme. When canopy fluxes are added, the TG Shamsaei scheme produces a profile that scales the one from the configuration with only surface fluxes. The addition of canopy heat flux does not change the character of vertical distribution but only the intensity of the heat flux. It shows the highest peak heat flux intensity with almost 2 . The VECD exp+gamma profile, on the other hand, distributes canopy fluxes only above the canopy bottom height. The peak heat flux is located above the canopy top when canopy fluxes are added and at the surface level when only surface fluxes are considered. Thanks to the gamma profile, the VECD scheme injects energy higher into the atmosphere than the other schemes. At the same time, it maintains a consistent representation of surface and canopy fluxes, which peak at the surface and just above the canopy top, respectively.

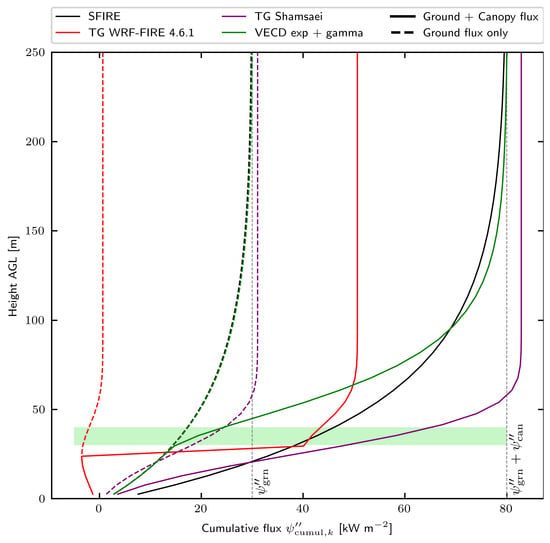

To study schemes’ energy conservation properties, we can calculate the surface equivalent cumulative flux , which represents the heat flux injected below a certain height, as:

The surface equivalent cumulative flux should converge to the value of the surface flux to distribute ( or ) at the top of the domain.

Figure 4 shows the vertical profile of the surface equivalent cumulative flux . The SFIRE scheme shows good energy conservation properties as it converges toward the initial flux when distributing heat for both configurations (with and without canopy flux). As canopy heat is injected close to the surface, 48% of the total energy is distributed below the canopy bottom height, whereas surface heat flux represents only 37.5% of the total flux. This allows to differentiate between the physical origin of the heat fluxes and make their distribution consistent with their character. The TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme does not converge to the expected surface flux value for both configurations. When canopy fluxes are added, it distributes only 63% of the fire heat flux. The discontinuity of the TG scheme represents 55% of the total flux to be injected. The TG Shamsaei injects 3.6% more energy than expected. Moreover, due to the aggregation of surface and canopy fluxes, it injects 59% of the total flux below the canopy level, showing a discrepancy between the physical source of heat and its location. All the energy is injected in the first 76 of the atmosphere. The VECD scheme converges appropriately to the expected value, showing good energy conservation properties for both configurations. With the canopy fluxes being added above the canopy, only 17% of the total heat is injected below the canopy bottom height.

Figure 4.

Same as Figure 3 for the surface equivalent cumulative flux (representing the heat flux injected below a certain height).

4. Discussion

Section 3.1 demonstrates that the analytically computed error in the energy conservation of the SFIRE scheme is negligible for typical model configurations.

Even in extreme cases with very small domain heights (377 ) and the extinction depth of 50 m, the error is about −0.05%.

Section 3.2, which tests the schemes numerically in two different grid resolutions, reinforces the results from the analytical analysis and proves good energy conservation properties from the SFIRE exponential scheme for both fine and coarse meshes.

Therefore, the claim by Shamsaei et al. [11] of a +278% relative error in energy conservation is unsubstantiated. We hypothesize that this assertion likely stems from a misinterpretation of the WRF-SFIRE scheme. Specifically, Figure 3 of Shamsaei et al. [11] presents the distribution factors, , defined in Equation (4), but mistakenly interprets them as the proportion of surface heat flux, . This confusion may have led to the incorrect conclusion that the scheme over-injected energy, as the sum of the distribution factors exceeds one. However, both analytical and numerical evaluations confirm that the energy conservation error in the WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme is negligible. The reported error most likely results from misidentifying the distribution factors as the heat flux proportions .

This work also evaluated the Truncated Gaussian (TG) scheme introduced by Shamsaei et al. [11] as a remedy to the allegedly faulty SFIRE distribution scheme. A discrepancy between the analytical formulation proposed in [11] and its implementation in WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 [17] has been identified. The implementation uses the cell centroid height instead of vertical levels. It also uses the same differentiation of distribution factors as the original exponential scheme, whereas the analytical formulation directly computes the fraction of surface flux to distribute. Both formulations have been assessed in this work. The same numerical analysis used to evaluate the SFIRE exponential scheme indicated multiple issues with both versions of the TG scheme.

The TG implementation in WRF-FIRE may yield negative fluxes, which are physically unrealistic. This issue arises because the function used in the TG formulation is non-monotonic. As a result, the difference in Equation (5) can become positive, leading to a negative source term , which lacks physical justification. It has been verified that this issue does occur in a test case using WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 (see Appendix A). It is important to note, however, that this issue does not occur if the first model level is located above the peak heat release height (as illustrated in Figure 2). Adding canopy heat fluxes in the implemented TG formulation introduces further issues, resulting in a non-physical discontinuity at the canopy bottom.

The analytical formulation of the TG scheme shows better behavior than that of its implemented version. It only gives positive fluxes but is inconsistent in conserving energy. The analytical formulation would yield better results if the cell centroid height were used instead of vertical levels and if applied to a very refined mesh. The last criterion is never met in practice, which makes this scheme mostly unusable for WRF simulations (see Appendix B).

Moreover, because both of the TG schemes use the same profile to distribute both surface and canopy heat fluxes, surface fluxes are erroneously injected higher into the atmosphere, even in the absence of canopy contributions. This behavior is nonphysical for surface fires, such as those represented in WRF-FIRE, which do not resolve crowning and canopy fuel consumption.

Both the issues of the original exponential SFIRE scheme and the most recent TG scheme implemented into WRF-FIRE are addressed by the proposed Versatile Energy-Conservative Distribution (VECD) scheme.

The newly introduced VECD scheme demonstrates excellent energy conservation across various configurations. It ensures rigorous energy balance and offers enhanced flexibility compared to the SFIRE scheme by supporting multiple analytical profiles, with the potential to incorporate any continuous function for future extensions. The inclusion of minimum and maximum heat injection heights (that can be user-defined or linked to physical properties) provides additional control over the vertical distribution of heat fluxes.

In particular, the VECD scheme allows for the independent distribution of surface and canopy heat fluxes using separate profiles. This capability improves the physical accuracy of heat flux positioning, ensuring that canopy heat injection does not interfere with surface heat distribution. By linking the canopy flux distribution to the canopy structure, the scheme offers a more realistic representation of fire–atmosphere interactions, making it a robust and versatile scheme for coupled fire–atmosphere models.

It is worth noting that in Figure 1, a slight offset appears between the expected and actual peak heat flux positions for the VECD Gaussian () and VECD gamma () profiles. This discrepancy is due to the non-uniformity of the vertical mesh: as cell sizes increase with height, more energy is injected into higher layers, shifting the apparent peak upward. Verification with a uniform mesh (Supplementary Figure S1) confirms that the peak heat flux positions align correctly in that case.

Among the profiles, the VECD exponential distributes the highest flux near the surface, making it particularly well-suited for surface heat flux representation. The Gaussian profile distributes heat symmetrically around a specified peak height, offering a balanced representation. In contrast, the gamma profile spreads energy over a broader vertical range, with minimal flux near the surface, making it more appropriate for canopy heat flux distribution.

5. Summary

The first objective of this work was to evaluate the energy conservation error in the WRF-SFIRE exponential scheme. The results of this study refute the findings of Shamsaei et al. [11]. They prove that the current scheme used in WRF-SFIRE has a negligible error when the top of the domain is large compared to the characteristic height used in the scheme. As this value is typically 50 , the error is less than 0.1% when the top of the domain is above 345 . This criterion is met practically in all WRF-SFIRE simulations.

The second objective was to address the limitations of existing heat distribution schemes and to benchmark the new formalism against existing methods for both energy conservation properties and physical representativeness when canopy fluxes are added.

All evaluated schemes demonstrate excellent energy conservation performance, except for both formulations of the Truncated Gaussian scheme. The implemented version consistently underestimates the heat flux, particularly at higher resolutions. The analytical version performs better than the implemented version, but is still several orders of magnitude worse in energy conservation than the original exponential scheme.

As a result, the TG schemes exhibit large relative errors in energy conservation. The implemented version reaches % and % for fine and coarse resolutions, respectively. The analytical version gives 4% and % errors, respectively. The implemented version also suffers from nonphysical negative heat flux values when the peak heat release height lies above the centroid of the first model level. Furthermore, when both surface and canopy fluxes are included, both TG schemes unrealistically position surface heat fluxes at the same elevation as canopy fluxes, undermining the physical representation of thermal fire effects.

After discussions with WRF-FIRE developers during the review process of this paper, an implementation error was detected in [17]. This error will be corrected, making the code performance consistent with the original formulation described in [11].

The VECD scheme provides a more accurate, physically representative, and flexible framework for vertical heat flux distribution in coupled fire–atmosphere models. Its ability to independently distribute surface and canopy heat fluxes is essential for correctly positioning heat sources, particularly under crowning fire conditions. This development lays the groundwork for the implementation of the new crowning model in SFIRE, planned for the next release. Future efforts will focus on evaluating the sensitivity of coupled simulations to vertical flux profiles and calibrating this new parameterization.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fire9010019/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; methodology, A.C.; software, A.C.; validation, A.C.; formal analysis, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and A.K.K.; writing—review and editing, A.K.K. and A.C.; funding acquisition, A.K.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by CALFIRE grant 8GG21829, NASA Awards #: 80 NSSC22K1405, 80 NSSC23K1344, 80 NSSC25K7276, US FS grant 22-CR-11221633-027, Future of Life Institute award 023-1505-2802, and NSF grant IUCRC-2113931.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues, original authors of Shamsaei et al. [11], and developers of WRF-FIRE, for the constructive discussions we had during the review process. Their openness in revisiting the initial claim, acknowledging the source of the error, and engaging in technical exchanges was greatly appreciated. I am also grateful for their willingness to explore the implementation of the VECD scheme in WRF-FIRE and to address the limitations of the TG scheme. Our interactions highlight a shared interest in improving coupled fire atmosphere models. We would like to acknowledge high-performance computing support from the Derecho system (doi:10.5065/qx9a-pg09) provided by the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), sponsored by the National Science Foundation. We are also grateful to the SJSU Fire HPC Support group for providing the computational assistance needed to carry out simulations and model analyses shown here.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Symbol | Name | Unit |

| specific heat capacity | ||

| Relative error on energy conservation | % | |

| Gauss error function | ||

| distribution factor | – | |

| g | continuous function defining a profile | |

| indefinite integral of g | ||

| k | vertical index | – |

| P | proportion of surface flux distributed in atmospheric cell | – |

| source terms in the energy conservation equation | ||

| Truncated Gaussian function of [11] | ||

| Truncated Gaussian scheme of [11] | ||

| t | time | |

| z | vertical coordinate | |

| peak heat release height of Gaussian schemes | ||

| canopy bottom height | ||

| canopy top height | ||

| extinction depth | ||

| maximal elevation for heat flux distribution | ||

| minimal elevation for heat flux distribution | ||

| distribution coefficient | – | |

| cell vertical extent | ||

| moist potential temperature | ||

| dry air mass per unit area | ||

| box function | ||

| air density | ||

| surface heat flux | ||

| surface heat flux for canopy fuels | ||

| surface equivalent cumulative flux | ||

| surface heat flux for ground fuels | ||

| volume heat flux |

Appendix A. Evaluation of WRF-FIRE TG Scheme for Test Case Two Fires

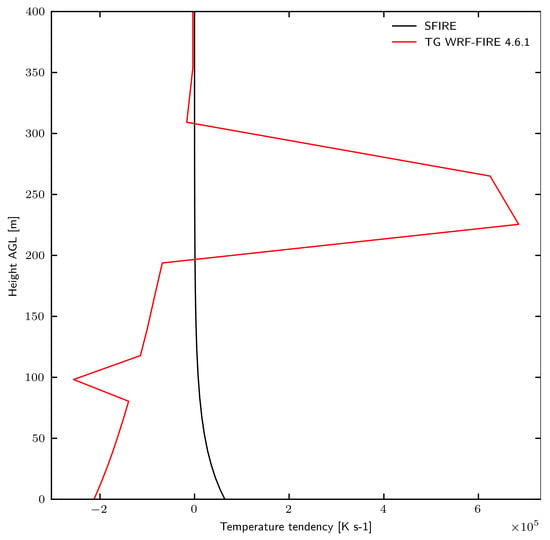

To further investigate the issue with the implementation of the TG scheme in WRF-FIRE version 4.6.1, we conducted simulations using the idealized test case two_fires. The code was compiled from the official WRF tag 4.6.1 [17]. Configuration files for this case are provided in the directory test/em_fire/two_fires.

By default, the simulation employs the original exponential heat flux profile, which is identical to that used in SFIRE. To activate the TG scheme, the flag was set to 1. All other relevant parameters were left at their default values, specifically fire_heat_peak = 0 , and fire_tg_ub = 1000 , corresponding to the peak heat flux height and the maximum heat release height , respectively.

Figure A1 compares the vertical profiles of temperature tendency—closely related to the energy source term described in this study—obtained using the exponential and TG schemes. The exponential profile (SFIRE) exhibits the expected smooth exponential decay. In contrast, the TG scheme produces significant negative values and discontinuities in the vertical profile. These features are consistent with the analytical issues previously identified in this paper. Moreover, the simulation using the TG scheme became numerically unstable and terminated after only five minutes.

This test case clearly demonstrates that the TG scheme, as currently implemented in WRF-FIRE 4.6.1, fails to provide a robust and physically consistent vertical heat flux distribution and is therefore unsuitable for operational fire simulations.

Figure A1.

Vertical profile of temperature tendency for the two fires test case using WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 with the exponential distribution scheme (black) and the TG WRF-FIRE 4.6.1 scheme (red). The profile is shown at ( , ), 4 min after the start of the simulation.

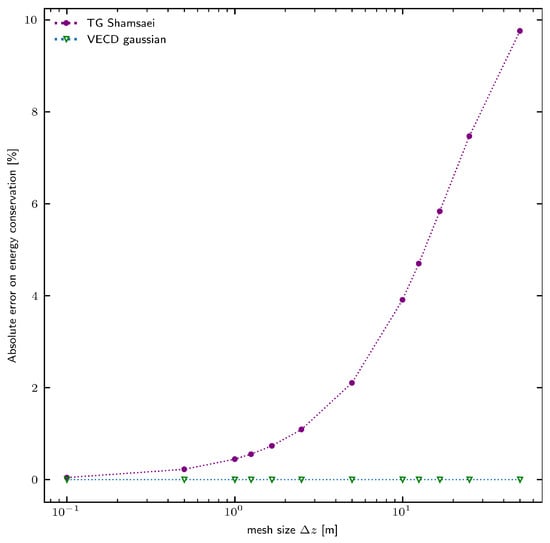

Appendix B. Mesh Convergence Study on Uniform Mesh for Gaussian Schemes

In principle, the TG scheme formulation [11] conserves energy in its continuous form. However, the discretization introduces sampling error that becomes non-negligible when the mesh is too coarse. This mesh convergence study aims to prove that the discretized TG scheme can be employed only with very refined meshes.

We consider a baseline uniform mesh of levels with initial mesh size . The finest mesh tested counts cells and a cell size . The surface heat flux is set to 30 , with set to 0 as we consider heat flux from the surface, and set to 250 . The height of maximum heat flux is set to 25 for both TG and VECD-gaussian schemes.

Figure A2 shows the absolute error on energy conservation as a function of mesh size for a uniform mesh configuration for TG Shamsaei (purple circles) and VECD-gaussian (green triangles) schemes. The formulation described in [11] converges to a null error for very fine meshes. Therefore, this scheme can display energy conservation properties when the sampling error is negligible, converging toward the continuous formulation. For a cell size of 0.1 , the absolute error is 0.045%, which is the same order of magnitude as the original exponential scheme of WRF-SFIRE for the fine mesh configuration (5 ). In practice, using the TG scheme to ensure reasonable energy conservation requires a significantly refined vertical mesh. The typical vertical mesh size near the surface used in WRF is too coarse for the TG scheme.

On the other hand, VECD’s extreme accuracy is independent of the mesh size, which makes it suitable for use with any mesh.

These results confirm that while the TG scheme upholds energy conservation in principle, its practical applicability is limited by the need for extremely fine meshes. In contrast, the VECD-Gaussian method achieves accurate results on any mesh.

Figure A2.

Absolute error on energy conservation as a function of mesh size for a uniform mesh configuration for TG Shamsaei (purple) and VECD-gaussian (green) schemes.

References

- Couto, F.T.; Filippi, J.B.; Baggio, R.; Campos, C.; Salgado, R. Numerical investigation of the Pedróg ao Grande pyrocumulonimbus using a fire to atmosphere coupled model. Atmos. Res. 2024, 299, 107223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrke, C.; Farguell, A.; Kochanski, A.K. Interactions Between a High-Intensity Wildfire and an Atmospheric Hydraulic Jump in the Case of the 2023 Lahaina Fire. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couto, F.T.; Filippi, J.B.; Baggio, R.; Campos, C.; Salgado, R. Triggering Pyro-Convection in a High-Resolution Coupled Fire–Atmosphere Simulation. Fire 2024, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, M.; Lareau, N.P.; Juliano, T.W.; Shamsaei, K.; Ebrahimian, H.; Kosovic, B. Sensitivity of simulated fire-generated circulations to fuel characteristics during large wildfires. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothermel, R.C. A Mathematical Model for Predicting Fire Spread in Wildland Fuels; Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, Forest Service: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1972; Volume 115. [Google Scholar]

- Balbi, J.H.; Morandini, F.; Silvani, X.; Filippi, J.B.; Rinieri, F. A physical model for wildland fires. Combust. Flame 2009, 156, 2217–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, P.A.; Filippi, J.B.; Balbi, J.H.; Bosseur, F. Wildland fire behaviour case studies and fuel models for landscape-scale fire modeling. J. Combust. 2011, 2011, 613424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatelon, F.J.; Balbi, J.H.; Cruz, M.G.; Morvan, D.; Rossi, J.L.; Awad, C.; Frangieh, N.; Fayad, J.; Marcelli, T. Extension of the Balbi fire spread model to include the field scale conditions of shrubland fires. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2022, 31, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drucker, J.R.; Farguell, A.; Clements, C.B.; Kochanski, A.K. A live fuel moisture climatology in California. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1203536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farguell, A.; Drucker, J.R.; Mirocha, J.; Cameron-Smith, P.; Kochanski, A.K. Dead Fuel Moisture Content Reanalysis Dataset for California (2000–2020). Fire 2024, 7, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsaei, K.; Juliano, T.W.; Roberts, M.; Ebrahimian, H.; Lareau, N.P.; Rowell, E.; Kosovic, B. The Role of Fuel Characteristics and Heat Release Formulations in Coupled Fire-Atmosphere Simulation. Fire 2023, 6, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.L.; Jenkins, M.A.; Coen, J.; Packham, D. A coupled atmosphere fire model: Convective feedback on fire-line dynamics. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 1996, 35, 875–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.L.; Jenkins, M.A.; Coen, J.L.; Packham, D.R. A coupled atmosphere-fire model: Role of the convective Froude number and dynamic fingering at the fireline. Int. J. Wildland Fire 1996, 6, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, E.G.; Coen, J.L. WRF-Fire: A coupled atmosphere-fire module for WRF. In Proceedings of the Preprints of Joint MM5/Weather Research and Forecasting Model Users’ Workshop, Boulder, CO, USA, 22–25 June 2004; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, J.; Beezley, J.D.; Kochanski, A.K. Coupled atmosphere-wildland fire modeling with WRF 3.3 and SFIRE 2011. Geosci. Model Dev. 2011, 4, 591–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz y Jimenez, P.A.; Frediani, M.; Eghdami, M.; Rosen, D.; Kavulich, M.; Juliano, T.W. The Community Fire Behavior Model for coupled fire-atmosphere modeling: Implementation in the Unified Forecast System. Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2024, 2024, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- WRF Model Development Team. Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model. Version 4.6.1-Commit d66e442fccc04111067e29274c9f9eaccc3cef28. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/wrf-model/WRF/releases/tag/v4.6.1 (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Filippi, J.B.; Bosseur, F.; Mari, C.; Lac, C.; Le Moigne, P.; Cuenot, B.; Veynante, D.; Cariolle, D.; Balbi, J.H. Coupled atmosphere–wildland fire modelling. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2009, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, J.B.; Bosseur, F.; Pialat, X.; Santoni, P.A.; Strada, S.; Mari, C. Simulation of coupled fire/atmosphere interaction with the MesoNH-ForeFire models. J. Combust. 2011, 2011, 540390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, J.B.; Pialat, X.; Clements, C.B. Assessment of ForeFire/Meso-NH for wildland fire/atmosphere coupled simulation of the FireFlux experiment. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 2633–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, A.; Rochoux, M.; Lac, C.; Masson, V. Subgrid-scale fire front reconstruction for ensemble coupled atmosphere-fire simulations of the FireFlux I experiment. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 126, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, A. Couplage Bidirectionnel Feu-Atmosphère Pour la Propagation des Incendies de Forêt: Modélisation, Incertitudes et Sensibilités. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Paul Sabatier-Toulouse III, Toulouse, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.