Abstract

Hydrogen, a promising alternative to conventional fuels, presents significant combustion hazards due to its low minimum ignition energy (MIE) and wide flammability range (4–75 vol.%). The risks are amplified with liquid hydrogen (LH2), which has an extremely low boiling point (20.3 K) and high diffusivity. Once released, LH2 vaporizes rapidly and mixes with ambient air. This process forms a cryogenic and highly flammable cloud, which significantly increases ignition and explosion hazards. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the MIE of cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures is crucial for quantitative risk assessment. This work develops and validates a numerical algorithm for predicting the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures at cryogenic temperatures (down to 93 K) across a wide range of hydrogen concentrations (10~50 vol.%) and oxygen concentration ratios [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%]. By coupling a detailed H2/O2 reaction mechanism with a large eddy simulation (LES) turbulence model, this algorithm demonstrates high reliability and accuracy. The results indicate (1) an exponential increase in MIE with decreasing initial temperature; (2) a U-shaped dependence of MIE on hydrogen concentration, with the minimum occurring near 25% hydrogen concentration; (3) an asymptotic dependence of MIE on oxygen concentration ratio, particularly at 40% hydrogen concentration. The initial temperature has the greatest influence on MIE; hydrogen concentration is the second; and the oxygen concentration ratio has the weakest influence. This study provides a theoretical framework and a practical computational tool for assessing and mitigating cryogenic ignition associated with LH2 leakage, thereby enabling safer application of liquid hydrogen technologies.

1. Introduction

Hydrogen energy is internationally recognized as a cornerstone of future energy systems, known for its renewable and environmentally friendly properties [1,2]. Hydrogen offers high energy density, no secondary pollution, and a wide range of feedstock sources [3,4], making it an ideal choice for large-scale, long-term, and low-cost energy storage [5]. Liquid hydrogen has a wide range of applications. In aerospace, LH2 has been extensively utilized as a highly efficient propellant [6,7]. In transportation, breakthroughs in fuel cell vehicles and hydrogen internal combustion engine technologies have significantly increased their commercialization potential [8,9]. LH2 also holds unique value in industrial applications, such as superconductor cooling [10,11]. Despite these advantages, the large-scale deployment of hydrogen energy faces significant safety challenges. The key issues arise from its extremely low boiling point (20.3 K) and its high diffusion coefficient, which is approximately four times that of natural gas and twelve times that of gasoline. LH2 is susceptible to leakage from operational errors, material degradation, or mechanical impacts [12]. A release event of liquid leads to rapid vaporization and the formation of a cryogenic flammable cloud. At ambient temperatures, hydrogen–air mixtures exhibit an exceptionally low minimum ignition energy (MIE) of 0.017 mJ and a broad flammability range (4~75 vol.%). Notably, even concentrations near the lower flammability limit (4~8 vol.%) can initiate deflagration [13]. These hazards are underscored by accidents such as the 2010 Space Shuttle Discovery launch delay and the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster.

The MIE, defined as the minimum energy required to ignite a combustible mixture, is a crucial parameter for assessing the ignition susceptibility [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Accurate MIE determination is essential for a monitoring and warning system for LH2 leakage [21]. At the same time, the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures at ambient temperatures has been extensively studied [22,23,24,25]. Ono et al. [22] measured the MIE values of hydrogen–air mixtures at different equivalence ratios, with a minimum value of 0.017 mJ occurring at ambient temperature, near the stoichiometric ratio (Φ = 1). Li et al. [26] predicted the MIE of various combustible gas mixtures based on a 20 L sphere using the theory of layer-by-layer flame propagation. Han et al. [27] analyzed the effects of energy supply procedure, spark channel radius, electrode size, and electrode gap distance on MIE by numerical methods. Wähner [28] used logistic regression to statistically analyze the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures based on experimental MIE test results.

Experimental determination of cryogenic MIE is challenging due to spark discharge instability caused by electrode condensation and mixture heterogeneity resulting from hydrogen’s low density. Additionally, defining safe experimental boundaries is difficult because it imposes limitations on experimental reproducibility. Cryogenic MIE data are therefore relatively scarce. Proust et al. [29] found experimentally that cryogenic temperatures in the LH2 leakage scenario lead to a significant increase in the MIE. Cirrone et al. [30] introduced a cryogenic MIE prediction model based on the flame thickness theory, and the calculations showed high agreement with Proust’s experimental data. Ghosh et al. [31] measured the MIE of dilute hydrogen–air mixtures at cryogenic temperatures (200 K to 295 K). They found that the MIE decreased by approximately eight at 245 K with an equivalence ratio ranging from 0.16 to 0.2, indicating that the MIE becomes significantly more sensitive to hydrogen concentration.

Furthermore, hydrogen’s boiling point is significantly lower than that of oxygen and nitrogen. Upon leakage, LH2 rapidly vaporizes by absorbing heat from the surroundings. The resulting intense cooling can cause the oxygen in ambient air to condense and even solidify, as shown in Figure 1. Such solid oxygen may undergo rapid phase transitions (sublimation or melting) due to ambient temperature fluctuations or mechanical disturbances, resulting in a localized increase in oxygen concentration. This oxygen-enriched atmosphere elevates the probability of secondary explosions following initial deflagration events. Hall et al. [32] documented, for the first time, through liquid-hydrogen release and ignition experiments, that solid air deposits, formed by the phase transition of air components, triggered secondary explosions. In the experiment, the secondary explosion generated a fireball with a diameter of approximately 8 m, and its peak infrared radiation reached 120.14 kW/m2, significantly higher than the 57.82 kW/m2 observed during the initial ignition phase. Kumamoto et al. [33] further showed that when O2/(O2 + N2) was increased from 0.35 to 1.00, the MIE minima decreased from 0.006 mJ to less than 0.004 mJ, which reveals a significant modulation of MIE by oxygen concentration.

Figure 1.

Solid deposit occurred in experiments of liquid hydrogen leakage [34].

Oxygen enrichment of the condensed air may have occurred due to oxygen having a higher boiling temperature than nitrogen. Critically oxygen-enriched atmosphere resulting from air-component phase transitions during LH2 leakage can alter fundamental combustion parameters. However, the reality is that experimental/numerical research on MIE of cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures predominantly focuses on specific ignition source types and limited temperature ranges; at the same time, quite a few systematically address the oxygen enrichment phenomenon.

To overcome experimental limitations, this work developed a CFD-based numerical algorithm for predicting MIE in cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures. The algorithm integrates a detailed H2/O2 reaction mechanism with a large eddy simulation (LES) turbulence model. The effects of initial temperatures (93 K to 300 K), hydrogen concentrations (10 vol.% to 50 vol.%), and oxygen concentration ratio [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%] on cryogenic MIE were systematically investigated, and compared with experimental data to verify its reliability. The validated model provides a crucial theoretical foundation for the safety protection design of LH2 storage and transportation systems. The lower temperature limit of 93 K was deliberately selected because it is close to the normal boiling point of oxygen (90.2 K at 1 atm). This study primarily focuses on near-critical and subcritical thermodynamic conditions relevant to liquid hydrogen leakage scenarios. When the initial temperature falls below the oxygen boiling point, oxygen in the surrounding air predominantly transitions into the solid phase. However, the scope of the present work is not the ignition behavior of solid oxygen itself, but rather the potential ignition hazards arising after solid oxygen is released and re-enters the gas phase, leading to localized oxygen-enriched mixtures.

2. Numerical Model and Methods

2.1. Mathematical Models

The ignition process of the premixed gas is simulated by solving the two-dimensional compressible reacting Navier–Stokes equations. The governing equations for continuity, momentum, energy, and species mass fraction are expressed as follows:

The continuity equation:

The momentum equation:

The energy equation:

The mass fraction equation:

where is the fluid density; is the pressure; is the component of the fluid velocity in the i-direction; is the effective coefficient of viscosity; is the enthalpy; is the component mass fraction; is the fuel combustion rate; is the turbulent energy; and is the energy source term.

The LES turbulent model can capture the dynamic behavior of the flame during the combustion process more accurately by directly resolving the large-scale turbulent eddy structure and only sub-grid-scale modeling of the small-scale turbulent motion [35,36,37,38,39]. This turbulence modeling approach is fundamentally based on the scale-separation principle of turbulent eddies, in which large-scale eddies that dominate the flow’s energy cascade and structural characteristics are directly resolved in the numerical solution of the Navier–Stokes equations. In contrast, small-scale eddy motions are modeled via subgrid-scale (SGS) parameterization. It is particularly suitable for simulating hydrogen combustion, characterized by a fast combustion rate, rapid flame propagation, and significant turbulence–combustion interaction. Therefore, LES is employed to enhance computational accuracy and more accurately reflect the turbulence characteristics and the evolution of the flame structure during hydrogen combustion.

In the LES model, each transient variable is decomposed into a large-scale resolved component and a small-scale subgrid component through a filtering operation. The following equation gives the mathematical representation of this filtering process:

The filtered momentum equations for LES are obtained through the application of the filtering operation, expressed as follows:

where represents the subgrid-scale stress, and this study employs the WALE subgrid-scale model; the corresponding subgrid-scale stress is expressed as

In the WALE model, the eddy viscosity coefficient is formulated as follows:

Among them, the expressions of and are as follows:

2.2. Detailed Chemical Reaction Mechanism

Table 1 presents the physical parameters of hydrogen–air mixtures at temperatures of 93 K, 100 K, 200 K, and 300 K [36]. The reaction mechanism of hydrogen combustion is crucial to combustion chemistry. Hydrogen combustion mechanisms have been revealed in recent years, as reviewed by Ó Conaire et al. [37], Konnov [38], Hong et al. [39], and Kéromnès et al. [40]. Based on a comprehensive comparative analysis, the Ó Conaire mechanism is selected for this study. It consists of 19 reversible elementary reactions and eight components (H2, O2, H2O, H, O, OH, HO2, H2O2), as shown in Table S1 in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Physical parameters of hydrogen–air mixtures at 93 K, 100 K, 200 K, and 300 K [36].

The Arrhenius formula in chemical kinetics describes the effect of temperature on reaction rate constants, which is expressed as

where is the reaction rate; is the pre-exponential factor indicating the frequency of effective collisions of reactant molecules; is temperature; n is the temperature exponent for the pre-exponential factor in the reaction rate; is the reaction activation energy; and is the ideal gas constant, 8.314 J·(mol·K)−1.

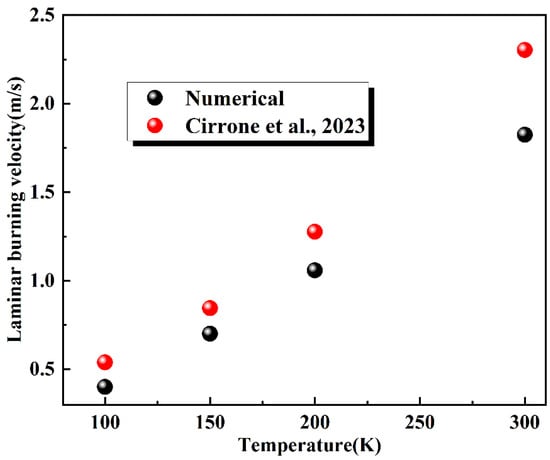

To validate the mechanism’s applicability under cryogenic conditions, the laminar burning velocity was numerically calculated for stoichiometric hydrogen–air mixtures at various initial temperatures. A comparative analysis with reference data from the literature [30] is presented in Figure 2. The computed values are consistent with the overall trend of the data, and the relative errors fall within the acceptable range. This also confirms the reliability and practical utility of the reaction mechanism for cryogenic applications.

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of laminar burning velocity (Φ = 1) [30].

2.3. Geometric Model and Numerical Methods

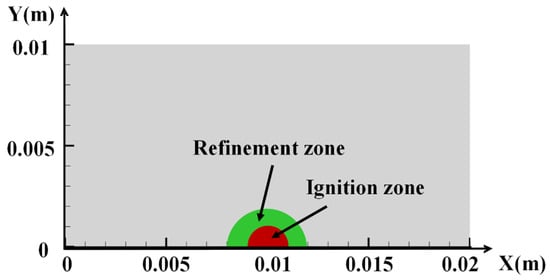

This work simplifies the physical model by adopting a two-dimensional axisymmetric model. The geometric model is set to 0.01 m along the Y-axis and 0.02 m along the X-axis, and it is rotated with the X-axis as the axis of symmetry, as shown in Figure 3. The ignition region is located at the center of the model. The coordinates of the ignition center are (0.01, 0). In the preliminary meshing, the overall cell size of the computational domain was set to 5 × 10−5 m, and the key computational region (centered at the ignition point with a radius of 2 × 10−3 m) was locally refined. The minimum cell size was 3.125 × 10−8 m, and the total number of cells was approximately 119,804. Given hydrogen’s low ignition energy and rapid flame propagation velocity, a locally refined mesh strategy was adopted. The time step is set to 1 × 10−8 s.

Figure 3.

Geometric model.

In this study, all simulations were conducted using ANSYS Fluent 2022 R1. A pressure-based transient solver coupled with the LES turbulence model was employed to simulate the hydrogen–oxygen combustion process. The WALE subgrid-scale model was used, with its model constant set to Cw = 0.325. For combustion modeling, a finite-rate model combined with a volumetric reaction approach was adopted. Adiabatic no-slip walls were applied as boundary conditions. The SIMPLE algorithm was used for velocity–pressure coupling. The PRESTO! scheme was selected for pressure discretization. The momentum equations were in bounded central differencing format. The turbulent kinetic energy, turbulent dissipation rate, and component transport equations used second-order upwind schemes.

2.4. Ignition Setting

The combustible gas within the radius of the ignition source is subjected to the initial ignition energy, chemical reaction, and combustion. After combustion, the flame propagates outward at an accelerated rate, causing the unburnt gas to heat up rapidly and undergo a combustion chemical reaction. As the flame surface continues to propagate, the combustible gas throughout the confined space gradually combusts. Therefore, the initial ignition source can be set as high-temperature gas to simulate the release of electrostatic energy. A semicircular region is defined as the ignition area consisting of H2, O2, and N2, and each component retains the proportion corresponding to its initial concentration. Initially, high temperature and pressure are set in the ignition source, as shown in the red area of Figure 3. The ignition energy of the combustible gas is expressed as

where is the MIE; is the diameter of the critical fire core; is the density of mixtures; is the specific heat capacity of mixtures; is the initially high temperature in the ignition source; and is the initial temperature.

Zhang et al. [41] demonstrated that the peak temperature of spark discharge was slightly greater than 3000 °C across various energy levels, whereas increasing the ignition energy did not significantly increase the peak spark temperature. The applicability of the ideal gas state equation is measured by the compression factor Z, as shown in Equation (13). Z is approximately equal to 1 (deviation < 5%), indicating that the ideal gas assumption is valid. Therefore, the initial temperature of the ignition region is assumed to be 3300 K. The initial pressure in the ignition region is determined by Equation (14). The energy in the ignition region is controlled by adjusting the ignition radius until the critical ignition energy is reached; thus, the MIE is determined.

where is the pressure in the ignition region; is the density of mixtures; is the gas constant, 8.314 J·(mol·K)−1; is the temperature of mixtures; and is the molar mass of mixtures.

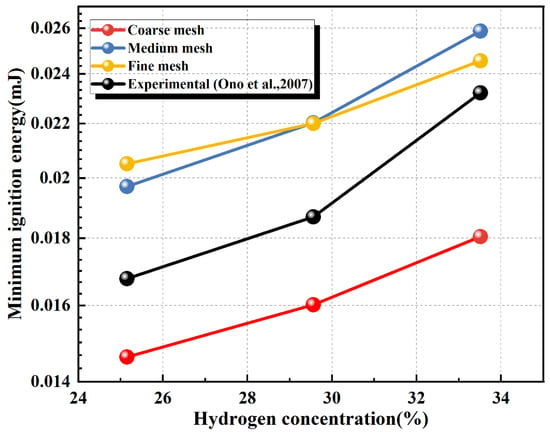

2.5. Independence Verification

As shown in Figure 3, mesh refinement is applied within the central area of the computational domain, defined as a circular region centered on the ignition origin at (0.01, 0) with a radius of 2 × 10−3 m. Fine, medium, and coarse meshes are used for independence verification. The ignition success criterion is described in detail in Section 2.6. The MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures at various concentrations and ambient temperatures is simulated at different mesh resolutions. The simulation results are compared with experimental values in Figure 4. A significant deviation is observed for the coarse and medium meshes. The relative error between the simulation results of the medium and fine meshes is less than 5%, but the computation cost increases several times. Therefore, given mesh convergence, enhanced computational efficiency, and the need to preserve accuracy, the medium mesh is ultimately adopted.

Figure 4.

Numerical values of MIE at different mesh resolutions [22].

2.6. Criteria for Successful Ignition

In this work, ignition success is defined as the gradual expansion of the high-temperature zone into the surrounding unburned region. Based on reaction-kinetics analysis, the criteria for determining ignition success include: the rebound of the maximum temperature after it falls below a critical threshold (minimum threshold: 800 K); the sustained generation of OH radicals; and a continuous increase in the integral mass of water vapor. This contrasts with the failure criterion established by Cirrone et al. [42], in which the system enters an ignition failure state when the maximum temperature in the ignition region drops below 600 K, and there is no stabilized OH radical production and water vapor accumulation.

When investigating the influence of the fuel–air equivalence ratio on combustion characteristics, the equivalence ratio Φ is defined as

where F/A is the actual fuel-to-air mass ratio and is the stoichiometric fuel-to-air mass ratio.

For hydrogen–air mixtures, the equivalence ratio can also be expressed as the ratio of the actual hydrogen-to-oxygen molar ratio to the stoichiometric hydrogen-to-oxygen molar ratio. Therefore, Φ can be written as

When , the mixture is fuel-lean; when , it is a stoichiometric mixture; and when , it is a fuel-rich mixture.

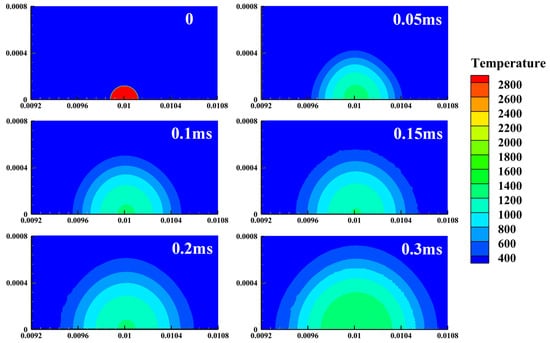

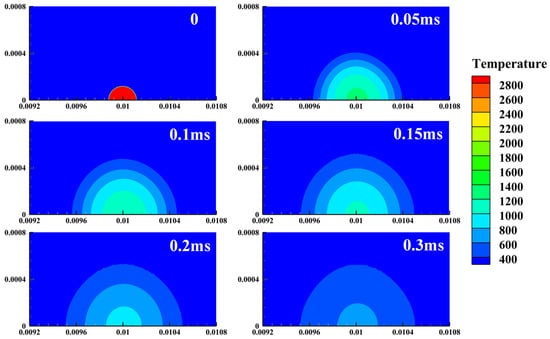

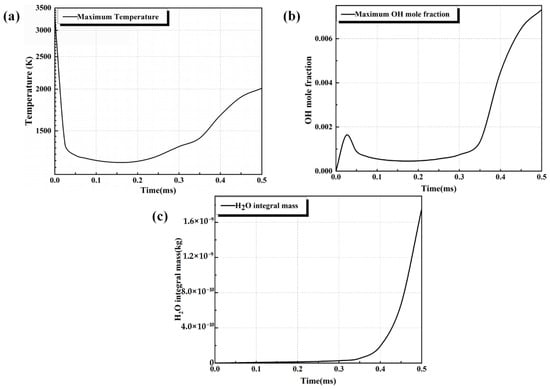

Figure 5 depicts the temporal evolution of the temperature field after ignition in a hydrogen–air mixture (Φ = 1.4). The flame kernel propagates spherically outward. The central temperature exhibits a transient decrease (0~0.15 ms) followed by sustained elevation (>0.15 ms), indicating that high-temperature reactions dominate over heat-dissipation mechanisms, thereby enabling a self-sustained process. In contrast, Figure 6 presents a scenario of failed ignition. After ignition, the central temperature rises to a peak and then rapidly declines to 800 K within 0.2 ms, exhibiting a characteristic decay profile. The combustion fails to expand effectively, and the temperature eventually drops to the initial value. Figure 7 provides kinetic confirmation of the temperature-field evolution shown in Figure 5, as evidenced by the concurrent increase in the peak OH molar fraction and the integral mass of water vapor. Their synergistic rise indicates that chain-branching reactions persist, and the positive feedback between reactive-radical concentrations and combustion-product accumulation further corroborates the chemical-kinetic criterion for successful ignition.

Figure 5.

Temperature history for a successful ignition.

Figure 6.

Temperature history for a failed ignition.

Figure 7.

Assessment of (a) maximum temperature, (b) maximum OH mole fraction, and (c) domain-integrated H2O mass as criteria for successful ignition in Φ = 1.4 hydrogen–air mixtures.

3. Model Validation

3.1. Model Validation of MIE at Ambient Temperature

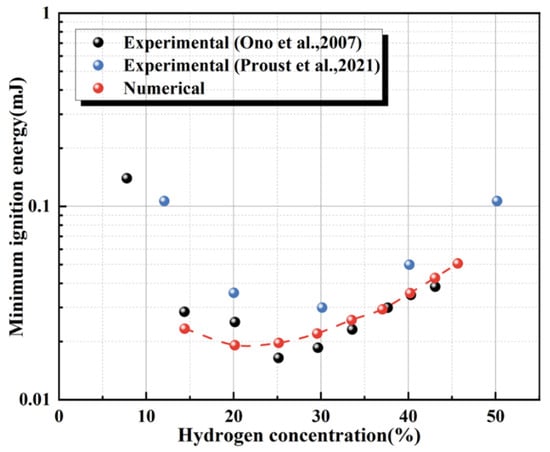

Validation data for MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures at ambient temperature were taken from experiments by Ono et al. [22] and Proust et al. [29]. The predicted MIE values for hydrogen–air mixtures at various concentrations at 298 K were compared with the measurements reported by Ono et al. [22]. The comparison, summarized in Table 2, shows that the MIE of hydrogen reaches a minimum of approximately 0.019 mJ at a hydrogen concentration of approximately 25%. At an equivalence ratio of 1.4, the relative error is only 1% compared with the experimental value. Across all operating conditions, the relative deviations between the predictions and experiments remain within 20%.

Table 2.

Comparison of simulated MIE with literature data at different hydrogen concentrations (298 K).

Figure 8 illustrates the dependence of the minimum ignition energy (MIE) on hydrogen concentration in hydrogen–air mixtures. The MIE exhibits a pronounced U-shaped concentration trend, in agreement with experimental observations. In both the lean (<20 vol.%) and rich (>30 vol.%) regimes, the MIE varies substantially and increases markedly, whereas it remains comparatively low in the intermediate range of 20–30 vol.% hydrogen. In the lean regime (<20 vol.%), insufficient fuel reduces the production rates of reactive radicals (e.g., OH and H) in the chain-branching reactions, making it challenging to sustain flame propagation and thus requiring higher ignition energy. In the rich regime (>30 vol.%), the MIE increases again because oxygen becomes limiting, thereby suppressing the overall oxidation rate. These results indicate that the numerical algorithm and ignition-processing approach adopted in this study can effectively reproduce the MIE behavior of hydrogen–air mixtures at ambient temperature.

Figure 8.

Validation of simulated data against experimental data of MIE of hydrogen–air mixture at ambient temperature [22,29].

3.2. Model Validation of MIE at Cryogenic Temperatures

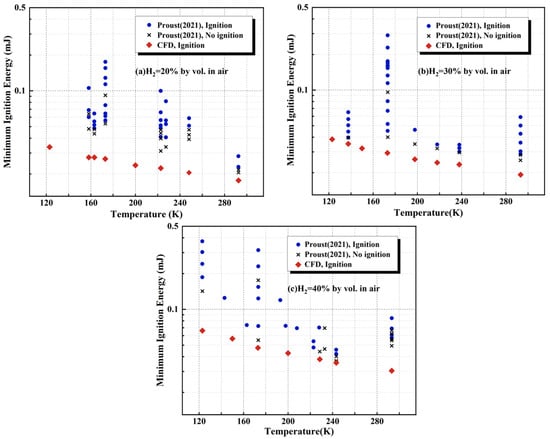

Figure 9 compares the simulated MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures with hydrogen volume fractions of 20%, 30%, and 40% over a temperature range of 123~293 K against the experimental data reported by Proust et al. [29]. The blue “○” and black “×” indicate the successful and failed conditions of ignition, respectively, and the red “◇” indicates the simulated values in this study. The experiments show a clear overall trend: the MIE increases as the initial temperature decreases. For the 20 vol.% hydrogen–air mixture, when the initial temperature drops from 293 K to 158 K, the measured MIE rises from 23 μJ to 60 μJ. The simulated MIE values obtained in this study capture this temperature dependence well and agree with the experimental trend. For the 40 vol.% hydrogen–air mixture, the experimental MIE increases from 58 μJ to 188 μJ as the initial temperature decreases from 293 K to 123 K. Under the condition of 30 vol.% hydrogen at an initial temperature of 137 K, the relative error reaches 13%; similarly, at 40 vol.% hydrogen and 243 K, the relative error is 14%. Overall, the relative errors remain within an acceptable range. Nonetheless, the predicted MIE values are consistently lower than the experimental measurements across all cases.

Figure 9.

Comparative analysis of simulated and experimental MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures at initial temperature in the range 123~293 K and hydrogen volume fractions of 20%, 30%, and 40% [29].

The observed deviations are likely primarily due to uncertainties in the spark-discharge characteristics in the experiments. Because hydrogen has an extremely low MIE, the ignition discharge process is susceptible to the precision and stability of the experimental apparatus. At cryogenic temperatures, the effective energy delivered to the mixture is lower than the nominal set value. In addition, small fluctuations in temperature and humidity in experiments can affect discharge behavior, potentially introducing measurement bias. By contrast, the numerical simulations assume that the input energy is entirely deposited into heating the hydrogen–air mixture, without accounting for energy losses or discharge inefficiencies. Therefore, it is reasonable that the simulated MIE values are systematically slightly lower than the experimental measurements.

Despite the discrepancies between simulations and experiments, the overall trends are consistent, and the deviations remain within an acceptable range. Therefore, this numerical algorithm is capable of accurately predicting the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures under cryogenic conditions.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effect of Initial Temperature

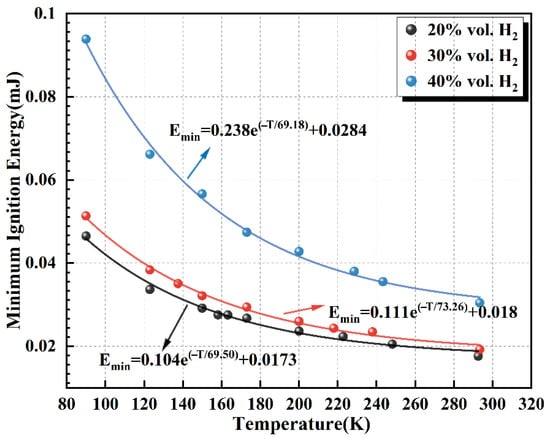

Figure 10 demonstrates the variation in MIE with temperature for hydrogen–air mixtures at hydrogen volume fractions of 20%, 30%, and 40%, respectively. Calculations indicate that the MIE increases significantly as the temperature decreases. Taking a hydrogen concentration of 30% as an example, when the initial temperature was reduced from 240 K to 93 K, the MIE increased approximately 1.3 times. The fitting analysis further shows an exponential growth relationship between MIE and temperature for cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures.

Figure 10.

Dependence of the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures on initial temperature.

It is further analyzed that this temperature dependence arises from two primary factors. First, enhanced heat dissipation is critical. Because the MIE of hydrogen is extremely low, the transient high-temperature gas kernel formed immediately after ignition is highly sensitive to ambient conditions. As the initial temperature decreases, the temperature gradient between the hot kernel and the surrounding cryogenic mixture increases, substantially accelerating heat loss via conduction and convection. The rapid cooling of the premixed-gas core prevents it from reaching and maintaining the critical temperature required for self-sustained combustion, leading to kernel quenching. Consequently, at cryogenic temperatures, a larger external ignition energy is needed to offset the increased heat losses and to establish a stable flame kernel.

Second, cryogenic conditions suppress chemical-kinetic processes. According to the Arrhenius relation, reaction rates increase exponentially with temperature [43]. Lower initial temperatures reduce the average molecular kinetic energy and decrease the fraction of molecules able to overcome the activation barrier, thereby significantly slowing the initiation and branching of combustion reactions. Moreover, the reduced diffusion coefficients and collision frequencies of hydrogen and oxygen at cryogenic temperatures further hinder the formation and transport of key chain-carrying radicals (e.g., H, O, and OH), weakening the self-sustaining nature of the chain reactions. As a result, the MIE increases as the temperature decreases.

4.2. Effect of the Hydrogen Concentration

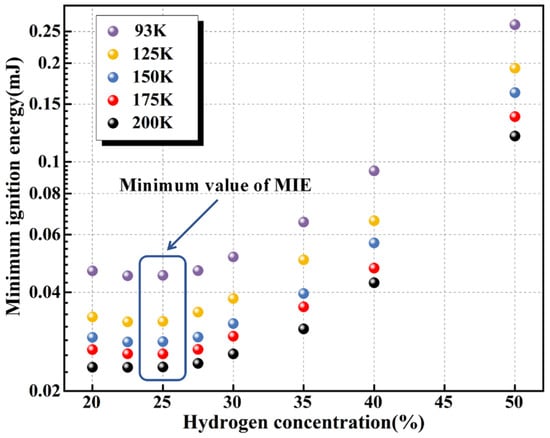

Figure 11 presents the variation in the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures over six hydrogen concentrations, with initial temperatures ranging from 93 to 200 K. At a given initial temperature, the MIE exhibits a typical U-shaped dependence on hydrogen concentration, with the minimum occurring near Φ ≈ 0.8. This differs from the ambient-temperature findings in the literature [26,33], where the minimum MIE was reported at Φ = 1, suggesting that cryogenic conditions modify the combustion dynamics of the mixture. Further analysis shows that at 200 K, the MIE increases by approximately four as the hydrogen volume fraction rises from 20% to 50%. For mixtures with hydrogen concentrations between 20% and 30%, the MIE variation among different equivalence ratios at the same initial temperature remains below 10%, indicating weak sensitivity in this range.

Figure 11.

MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures for different hydrogen concentrations at initial temperatures of 93 K, 125 K, 150 K, 175 K, and 200 K.

In contrast, the influence of hydrogen concentration on MIE becomes much more pronounced in the fuel-rich regime. This can be attributed to both kinetic and thermophysical effects. From a kinetic perspective, increasing hydrogen concentration reduces the relative oxygen fraction, leading to oxygen deficiency and suppressing chain-branching reactions. As a result, the concentrations of key radicals (H, O, and OH) decrease, while the likelihood of three-body recombination rises, accelerating chain-termination processes. From a thermophysical standpoint, higher hydrogen concentrations markedly alter mixture properties, including reduced density and increased specific heat capacity (Table 3). Under fuel-rich conditions, the lower density decreases the number of fuel and oxidizer molecules per unit volume, reducing collision frequency, slowing reaction rates [44], and thus increasing the ignition-energy requirement. Moreover, the substantial increase in mixture thermal conductivity enhances heat diffusion from the hot ignition kernel to the surrounding cold medium, weakening the kernel’s ability to sustain high temperatures. Consequently, a higher external energy input is required to compensate for heat losses and maintain the continuity of the combustion reactions.

Table 3.

Parameters of hydrogen–air mixtures for different hydrogen concentrations at initial temperatures of 200 K.

4.3. Effect of the Oxygen Concentration Ratio O2/(O2 + N2)

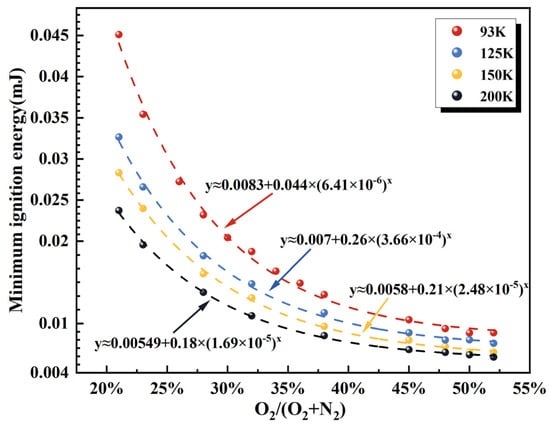

Calculations in this work show that the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures is minimized at approximately 25% hydrogen concentration. Accordingly, a hydrogen volume fraction 25% is selected to investigate the influence of the oxygen concentration ratio [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%] on MIE under different temperatures, as illustrated in Figure 12. The results indicate a pronounced nonlinear dependence of MIE on O2/(O2 + N2) at a fixed hydrogen concentration, exhibiting clear asymptotic behavior. For all initial temperatures examined, the MIE decreases sharply as the oxygen ratio increases from 21% to approximately 45%. Once the oxygen ratio exceeds 45%, the curve approaches a plateau, and further oxygen enrichment leads only to a marginal reduction in MIE.

Figure 12.

MIE of H2-O2-N2 mixture with fixed hydrogen concentration (25 vol.%) for various ratios of O2/(O2 + N2) at initial temperatures of 93 K, 125 K, 150 K, 175 K, and 200 K.

This behavior can be attributed to a dual effect of oxidant concentration. On the one hand, increasing the oxygen fraction markedly enhances the laminar burning velocity of the mixture [45], thereby promoting chain-branching reactions through elevated production of reactive radicals (H, O, and OH). On the other hand, once the oxygen concentration reaches approximately 45%, the radicals approach a chemical-equilibrium state governed by the law of mass action. Chain-termination reactions become increasingly dominant, markedly diminishing the sensitivity of the overall reaction rate to further oxygen enrichment and signaling a shift in the kinetic control regime.

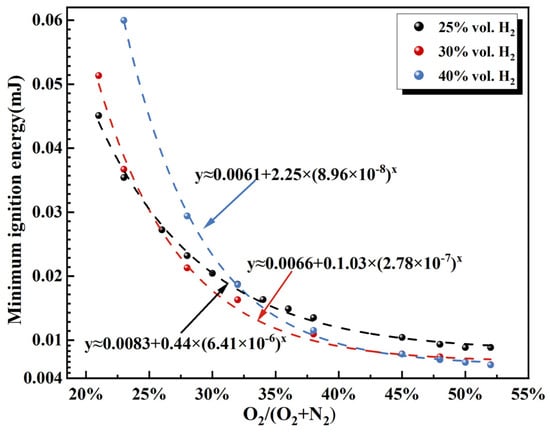

During liquid hydrogen (LH2) leakage, rapid vaporization can reduce the surrounding air temperature below the condensation temperatures of air components, thereby inducing localized oxygen enrichment. The condensed or solidified oxygen subsequently re-evaporates and interacts with the hydrogen–air mixture, leading to locally oxygen-enriched conditions. Figure 13 compares the influence of different O2/(O2 + N2) ratios on the MIE for hydrogen–air mixtures with varying initial hydrogen concentrations at 93 K. The results show that as O2/(O2 + N2) increases from 21% to 45%, the MIE for each hydrogen-concentration case follows an asymptotic-type correlation that can be fitted using a power-law exponent. Among all cases, the 40% hydrogen mixture exhibits the highest sensitivity, with an approximate 92% reduction in MIE, which is substantially greater than the reductions observed for 25% and 30% hydrogen concentrations (see Table 4). When O2/(O2 + N2) exceeds 45%, the MIE for the high-hydrogen case (40%) becomes lower than that for the lower-hydrogen cases (25% and 30%). This indicates that increasing hydrogen concentration amplifies the promoting effect of oxygen enrichment on ignition. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the design of inerting and detonation-suppression systems in scenarios involving high-concentration hydrogen leakage.

Figure 13.

MIE of H2-O2-N2 mixtures for various hydrogen concentrations and oxygen concentration ratios O2/(O2 + N2) at 93 K.

Table 4.

Effect of oxygen concentration ratios O2/(O2 + N2) on MIE of H2-O2-N2 mixtures for various hydrogen concentrations at 93 K.

This indicates that regions with moderate oxygen enrichment (O2/(O2 + N2) ≈ 25–40%) represent the highest ignition-risk zones. In contrast, although extremely oxygen-rich regions remain hazardous, their ignition probability does not increase proportionally due to the asymptotic stabilization of the MIE curve. In liquid hydrogen (LH2) infrastructure, safety protection measures should therefore prioritize areas where localized moderate oxygen enrichment is likely to occur, rather than focusing exclusively on regions with the highest oxygen concentrations. In addition, the alarm thresholds of oxygen monitoring systems should be optimized accordingly. Incorporating these findings into quantitative analyses of LH2 leakage accidents enables ignition-probability assessments that better reflect the underlying physical processes, thereby improving the inherent safety design of hydrogen energy systems.

5. Conclusions

The originality of this study lies in the development and validation of a numerical algorithm capable of predicting the MIE of hydrogen–air mixtures (10–50% vol.) in cryogenic environments (down to 93 K). The algorithm systematically investigates the effects of initial temperature, hydrogen concentration, and oxygen concentration ratio [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%] on the MIE of cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures by coupling the LES turbulence model with detailed chemical reaction mechanisms. The specific conclusions are as follows:

A numerical algorithm is developed to predict the MIE of cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures using computational fluid dynamics methods. The algorithm calculates the MIE by inputting the mixture composition and initial temperature parameters and verifies that the numerical algorithm is reliable.

When the hydrogen concentration is the same, the MIE of cryogenic hydrogen–air mixtures increases exponentially with the decrease in temperature. For typical hydrogen concentrations, the MIE at 93 K is 2–4 times higher than that at 200 K, demonstrating the dominant influence of temperature on cryogenic ignition behavior. When the initial temperature is the same, the MIE exhibits a typical “U” distribution with changes in hydrogen concentration, with the minimum value occurring near 25% of the hydrogen concentration. The ratio of the MIE to the oxygen concentration [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%] showed a significant nonlinear correlation. Its trend matches the characteristics of an asymptotic function.

The initial temperature has the most significant effect on the MIE of the cryogenic hydrogen–air mixture, followed by hydrogen concentration. The oxygen concentration ratio [O2/(O2 + N2) = 21~52%] has a relatively minor effect. This can be attributed to the chain-reaction mechanism of hydrogen combustion, which relies heavily on the generation and accumulation of free radicals (e.g., H, O, OH). The rates of branching reactions (e.g., O+H2 → H+OH) increase exponentially with temperature. Additionally, higher temperatures accelerate the overall reaction kinetics, rendering the mixture more ignitable and thus drastically reducing the MIE. In contrast, hydrogen concentration primarily affects the amount of reactants, while the oxygen concentration ratio modulates chain-transfer efficiency. Neither directly governs free radical generation rates, unlike temperature.

Future work will further extend the present model by incorporating multiphase effects, such as oxygen condensation and solidification at temperatures below its boiling point. In addition, the model will be expanded to predict the flammability limits of hydrogen–air mixtures under cryogenic conditions, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of ignition and combustion risks. Experimental measurements under cryogenic and oxygen-enriched environments are also required to validate and refine the proposed numerical methodology and to enhance its applicability to hydrogen safety assessments.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/fire9010018/s1. Table S1. The Ó Conaire hydrogen combustion reaction mechanism used in this study, including 19 reversible elementary reactions and eight species (H2, O2, H2O, H, O, OH, HO2, H2O2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L., M.L. (Miao Li) and X.C.; Methodology, L.L., L.H. and M.L. (Mengru Li); Software, Y.D.; Validation, C.H.; Investigation, Y.Y., W.H. and X.W.; Data curation, Y.D.; Writing—original draft, M.L. (Miao Li); Visualization, X.W.; Supervision, L.H., M.L. (Mengru Li), X.C. and C.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12572420), the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2025A1515011920), and the Natural Science Foundation Innovation Group Project of Hubei Province (2023AFA013).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author L.H. was employed by the company Aerospace Hydrogen Energy Technology Co., Ltd., Y.Y. and W.H. were employed by the company Sinosteel Wuhan Safety & Environmental Protection Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors report no conflicts of interest related to the work under consideration.

References

- Sadeq, A.M.; Homod, R.Z.; Hussein, A.K.; Togun, H.; Mahmoodi, A.; Isleem, H.F.; Patil, A.R.; Moghaddam, A.H. Hydrogen energy systems: Technologies, trends, and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 939, 173622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Zhao, H.; Li, X.; Tian, F.; Liu, Z.; Li, G.; Yuan, C. Investigation on decelerated propagation of hydrogen-air premixed flames in confined space. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 192, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mao, X.; Li, J.; Wei, H.; Shu, G.; Pan, J. Role of hydrogen enrichment in ammonia forced ignition at elevated pressures. Combust. Flame 2025, 272, 113908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.E.; Wahid, M.A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: Promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Nie, B.; Wang, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ma, C.; Hu, B.; Chang, L.; Yang, L. Effect of hydrogen concentration, initial pressure and temperature on mechanisms of hydrogen explosion in confined spaces. Combust. Flame 2024, 269, 113696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, Y. Thermal physical performance in liquid hydrogen tank under constant wall temperature. Renew. Energy 2019, 130, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Z. CFD investigation of thermal and pressurization performance in LH2 tank during discharge. Cryogenics 2013, 57, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, A.; Verstraete, D. Fuel cell propulsion in small fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles: Current status and research needs. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 21311–21333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokrani, Z.; Rekioua, D.; Mebarki, N.; Rekioua, T.; Bacha, S. Proposed energy management strategy in electric vehicle for recovering power excess produced by fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2017, 42, 19556–19575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyuk, V.V.; Blagov, E.V.; Antyukhov, I.V.; Firsov, V.P.; Vysotsky, V.S.; Nosov, A.A.; Fetisov, S.; Zanegin, S.; Svalov, G.; Rachuk, V.; et al. Cryogenic design and test results of 30-m flexible hybrid energy transfer line with liquid hydrogen and superconducting MgB2 cable. Cryogenics 2015, 66, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, Y.; Tatsumoto, H.; Shiotsu, M.; Hata, K.; Kobayashi, H.; Naruo, Y.; Inatani, Y.; Kinoshita, K. Forced flow boiling heat transfer of liquid hydrogen for superconductor cooling. Cryogenics 2011, 51, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordin, P.M. Review of Hydrogen Accidents and Incidents in NASA Operations; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Cleveland, OH, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, J.O.; Gresho, M.; Harris, A.; Tchouvelev, A.V. What is an explosion? Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 20426–20433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, O.; Kyono, T.; Kido, Y.; Ito, H.; Nakamura, Y. Ignition of electrical wire insulation with short-term excess electric current in microgravity. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2011, 33, 2617–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigas, F.; Sklavounos, S. Evaluation of hazards associated with hydrogen storage facilities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2005, 30, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryer, F.L.; Chaos, M.; Zhao, Z.; Stein, J.N.; Alpert, J.Y.; Homer, C.J. Spontaneous ignition of pressurized releases of hydrogen and natural gas into air. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2007, 179, 663–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astbury, G.R. A review of the properties and hazards of some alternative fuels. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2008, 86, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdyumov, V.N.; Jiménez, C. Ignition by concentrated heat sources: Minimum energy required and flame propagation over long distances in mixtures below the flammability limit. Combust. Flame 2025, 273, 113959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.-W.; Jain, V.; Kozola, S. Measurements of minimum ignition energy by using laser sparks for hydrocarbon fuels in air: Propane, dodecane, and jet-A fuel. Combust. Flame 2001, 125, 1320–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essmann, S.; Markus, D.; Grosshans, H.; Maas, U. Experimental investigation of the stochastic early flame propagation after ignition by a low-energy electrical discharge. Combust. Flame 2020, 211, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, K.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Huang, C. Theoretical prediction model for minimum ignition energy of combustible gas mixtures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 69, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, R.; Nifuku, M.; Fujiwara, S.; Horiguchi, S.; Oda, T. Minimum ignition energy of hydrogen–air mixture: Effects of humidity and spark duration. J. Electrost. 2007, 65, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, B.; von Elbe, G. CHAPTER II-The Reaction between Hydrogen and Oxygen. In Combustion, Flames and Explosions of Gases, 3rd ed.; Lewis, B., von Elbe, G., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1987; pp. 25–77. [Google Scholar]

- Calcote, H.F.; Gregory, C.A.; Barnett, C.M.; Gilmer, R.B. Spark Ignition. Effect of Molecular Structure. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1952, 44, 2656–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, H.E.; Priede, T. Ignition phenomena in hydrogen-air mixtures. Symp. Int. Combust. 1958, 7, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sun, W.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z. Minimum ignition energy theoretical model for flammable gas based on flame propagation layer by layer. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2023, 83, 105086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yamashita, H.; Hayashi, N. Numerical study on the spark ignition characteristics of hydrogen–air mixture using detailed chemical kinetics. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 9286–9297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wähner, A.; Gramse, G.; Langer, T.; Beyer, M. Determination of the minimum ignition energy on the basis of a statistical approach. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2013, 26, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust, C.; Jamois, D. Some Fundamental Combustion Properties of “Cryogenic” Premixed Hydrogen Air Flames. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Hydrogen Safety (ICHS 2021), Edinburgh, UK, 21–24 September 2021; pp. 228–239. [Google Scholar]

- Cirrone, D.; Makarov, D.; Proust, C.; Molkov, V. Minimum ignition energy of hydrogen-air mixtures at ambient and cryogenic temperatures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2023, 48, 16530–16544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Munoz-Munoz, N.M.; Lacoste, D.A. Minimum ignition energy of hydrogen-air and methane-air mixtures at temperatures as low as 200 K. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 30653–30659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.E.; Hooker, P.; Willoughby, D. Ignited releases of liquid hydrogen: Safety considerations of thermal and overpressure effects. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 20547–20553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumamoto, A.; Iseki, H.; Ono, R.; Oda, T. Measurement of minimum ignition energy in hydrogen-oxygen-nitrogen premixed gas by spark discharge. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2011, 301, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, P.; Willoughby, D.B.; Royle, M. Experimental releases of liquid hydrogen. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Hydrogen Safety (ICHS), San Francisco, CA, USA, 12–14 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Xiao, J.; Gupta, S.; Freitag, M.; Kuznetsov, M.; Rui, S.; Zhou, S.; Jordan, T. Numerical and experimental investigations of hydrogen-air-steam deflagration in two connected compartments with initial turbulent flow. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2024, 184, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD 69. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/ (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Ó Conaire, M.; Curran, H.J.; Simmie, J.M.; Pitz, W.J.; Westbrook, C.K. A comprehensive modeling study of hydrogen oxidation. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 2004, 36, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, A.A. Remaining uncertainties in the kinetic mechanism of hydrogen combustion. Combust. Flame 2008, 152, 507–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Davidson, D.F.; Hanson, R.K. An improved H2/O2 mechanism based on recent shock tube/laser absorption measurements. Combust. Flame 2011, 158, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kéromnès, A.; Metcalfe, W.K.; Heufer, K.A.; Donohoe, N.; Das, A.K.; Sung, C.-J.; Herzler, J.; Naumann, C.; Griebel, P.; Mathieu, O.; et al. An experimental and detailed chemical kinetic modeling study of hydrogen and syngas mixture oxidation at elevated pressures. Combust. Flame 2013, 160, 995–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. Experimental study of transient response of spark discharge ignition temperature. Gaodianya Jishu High Volt. Eng. 2015, 41, 547–553. [Google Scholar]

- Cirrone, D.; Makarov, D.; Molkov, V. Spontaneous Ignition of Cryo-Compressed Hydrogen in a T-Shaped Channel System. Hydrogen 2022, 3, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.S. The Detonation Phenomenon; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, H.; Lu, L.; Huang, Z. Flammability limits of hydrogen-enriched natural gas. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 6937–6947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckart, S.; Zsély, I.G.; Krause, H.; Turányi, T. Effect of the variation of oxygen concentration on the laminar burning velocities of hydrogen-enriched methane flames. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 49, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.