Fire Safety Analysis of Alternative Vehicles in Confined Spaces: A Study of Underground Parking Facilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

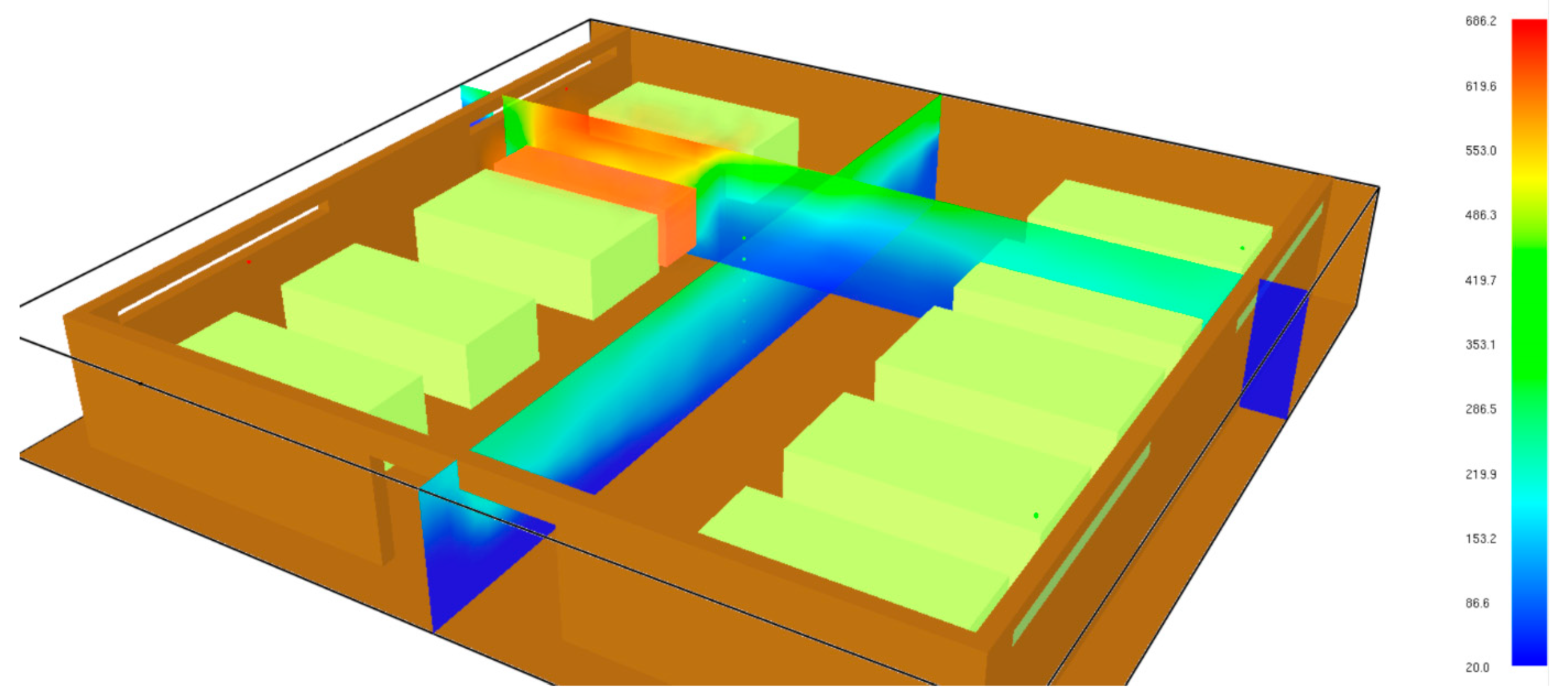

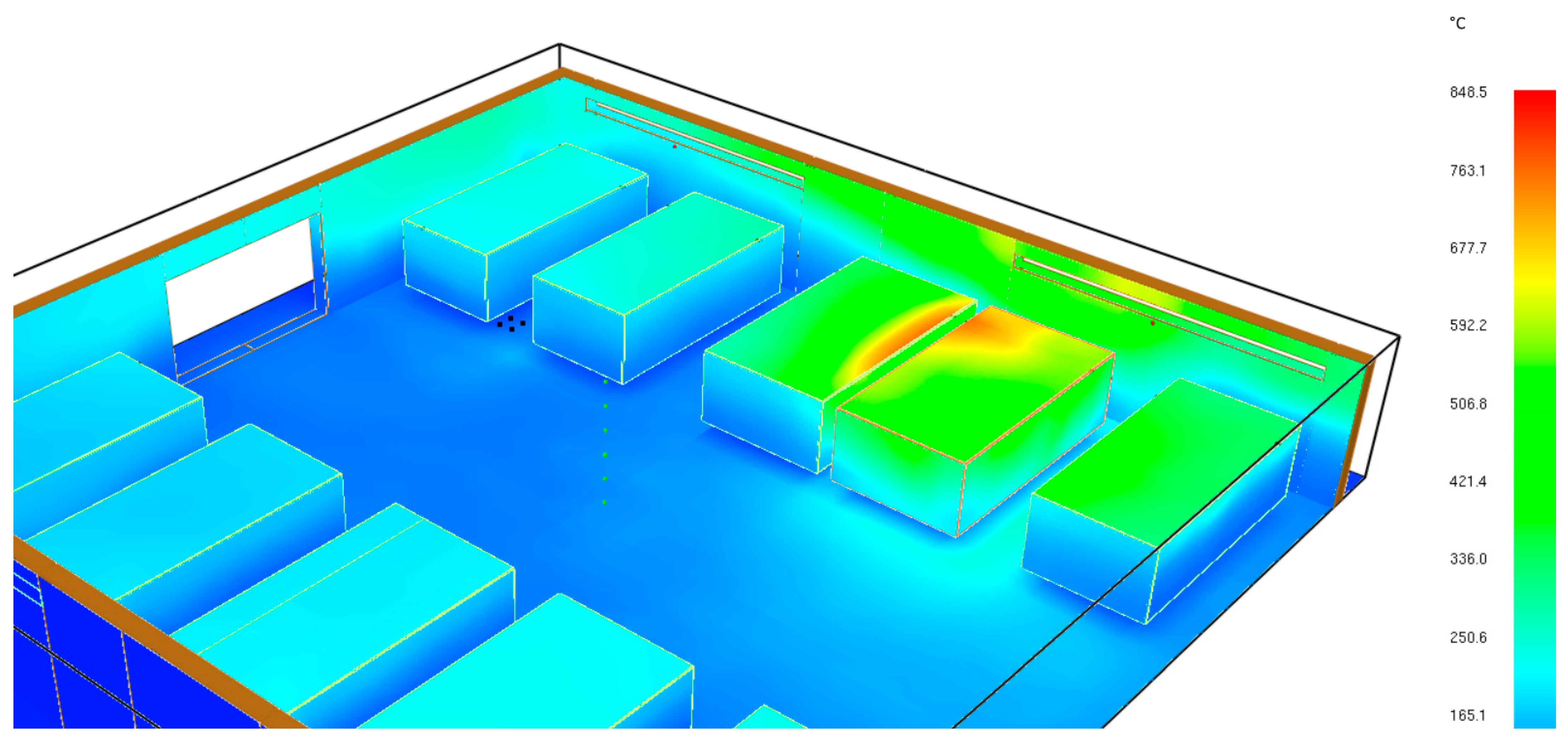

2. Material and Methods—Simulation

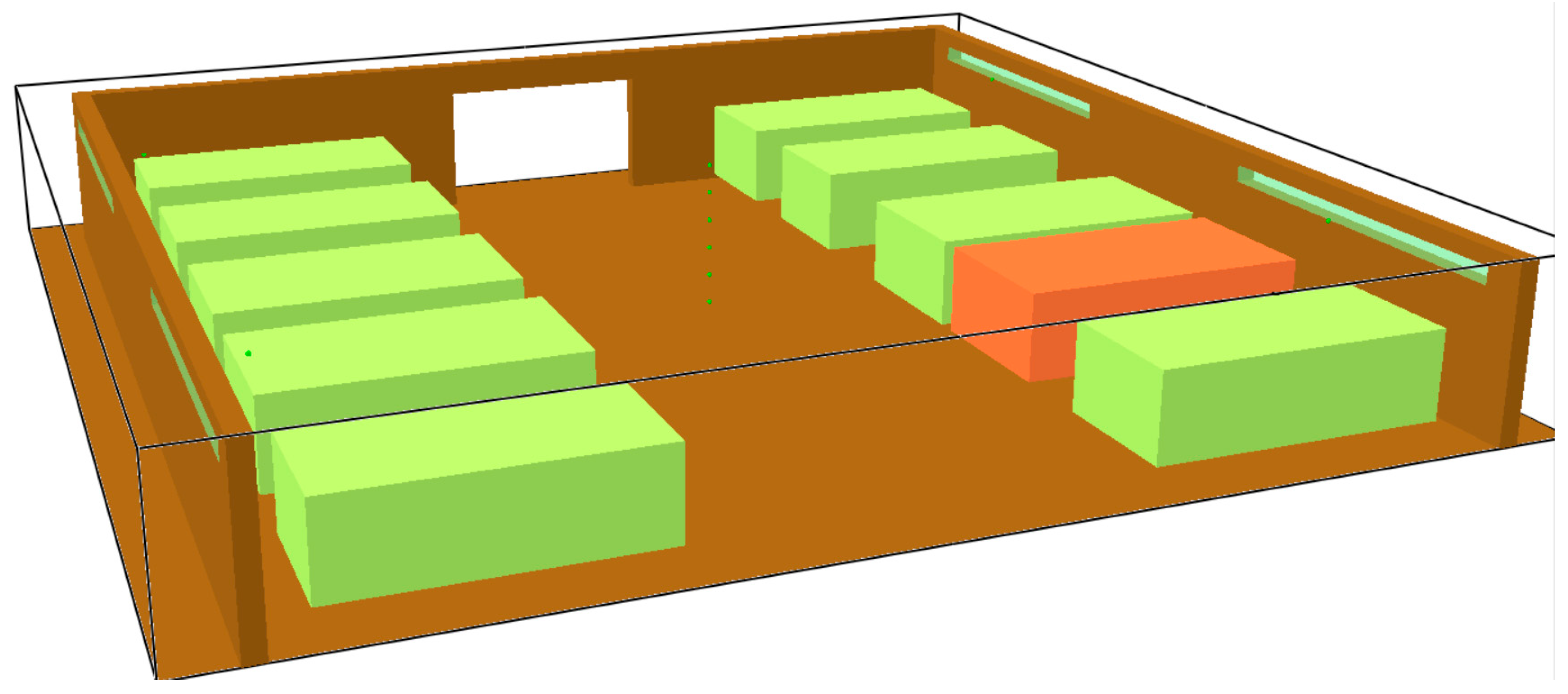

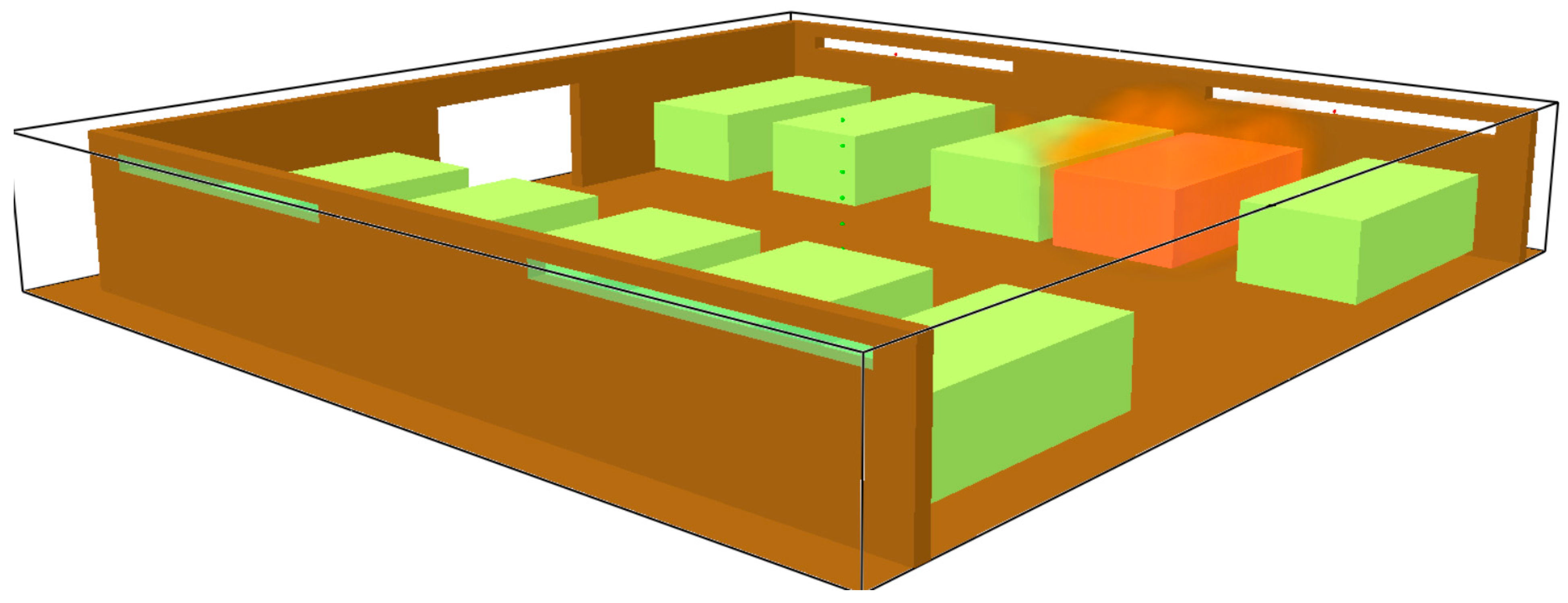

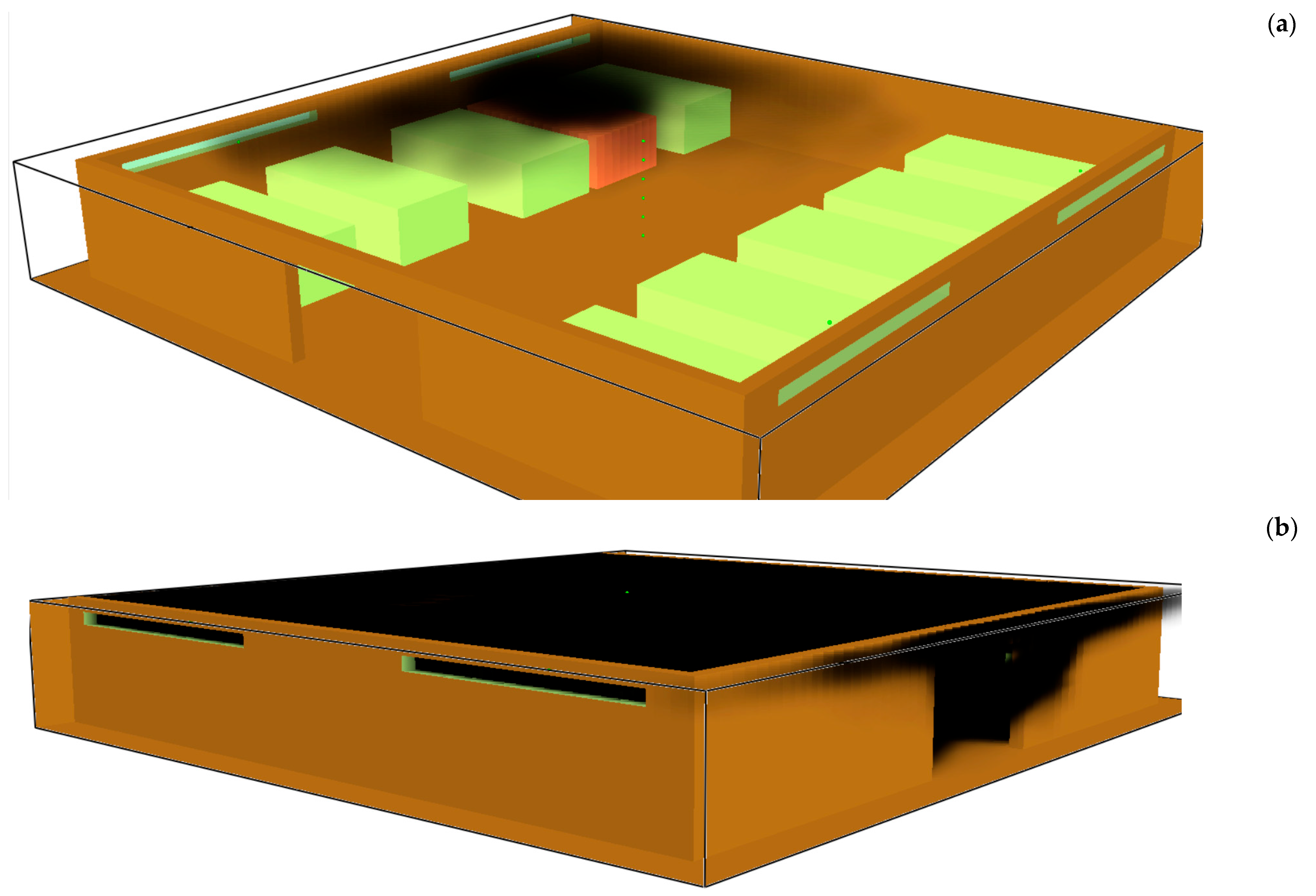

2.1. Simulation Environment and Model Design

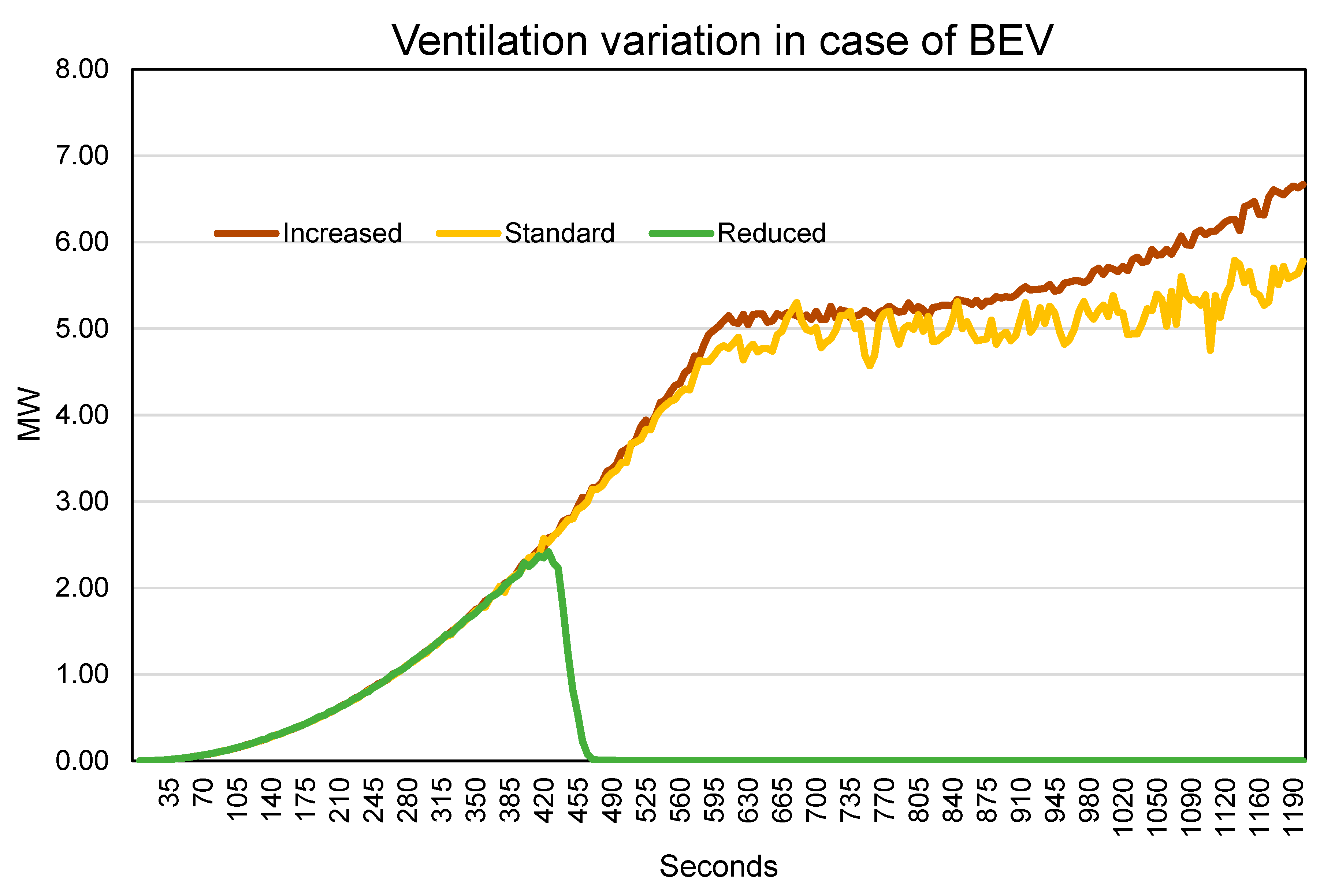

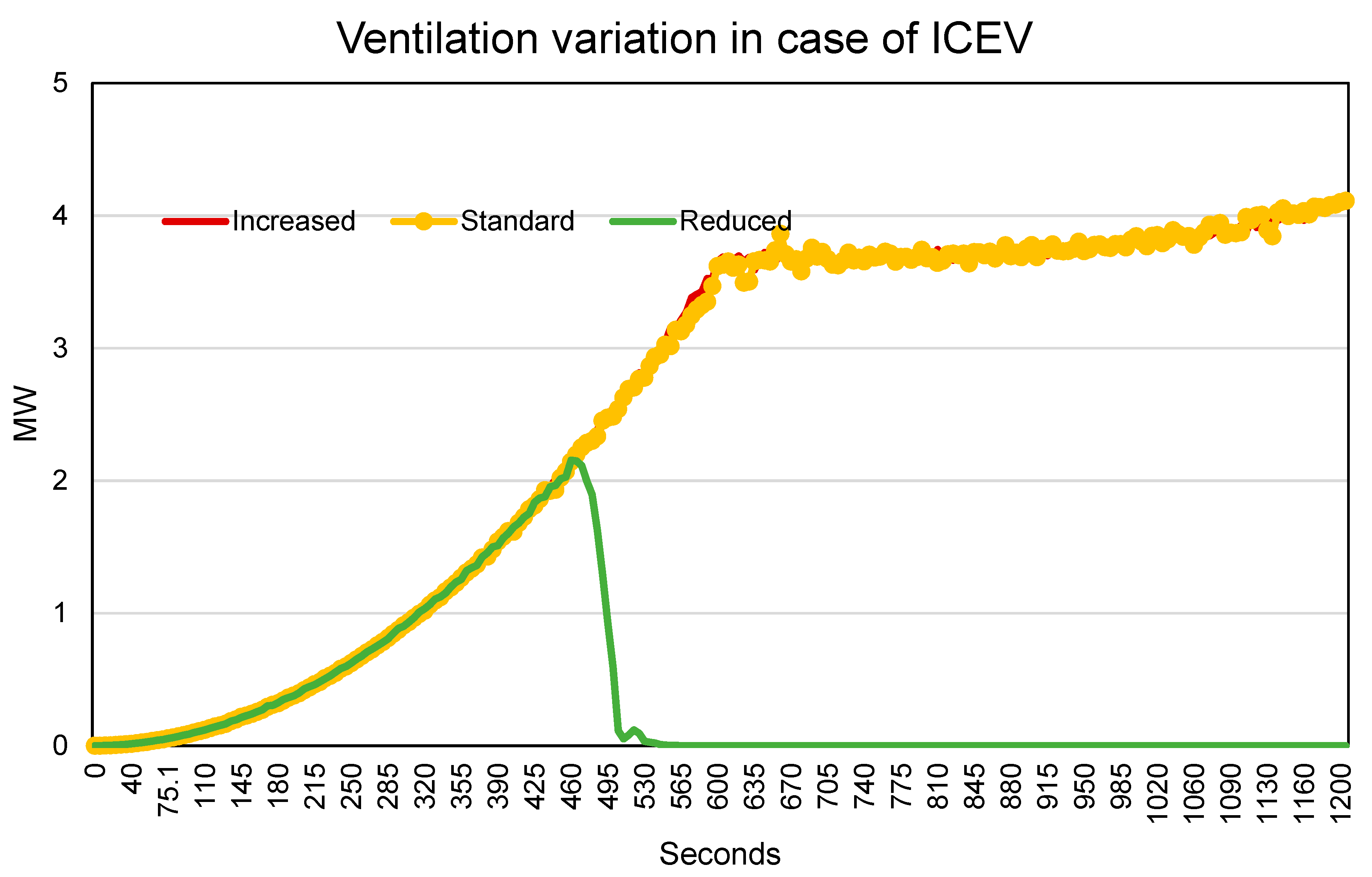

- Reduced ventilation, with limited air exchange and closed lateral openings. In this configuration, all side openings were kept closed, and air exchange occurred only through minimal leakage and the main entrance area (6 m2). This condition represents a worst-case scenario where oxygen availability is limited, leading to incomplete combustion and rapid smoke accumulation beneath the ceiling. The lack of fresh air inflow caused the fire to become oxygen-limited after a short growth phase.

- Standard ventilation, with windows breaking at approximately 300 °C, simulating glass failure [35]. In the baseline configuration, the side windows were initially closed but programmed to break automatically when the local temperature reached 300 °C, simulating the thermal cracking of glass observed in real fires. This dynamic event introduced natural ventilation at mid-height, allowing partial air exchange between the interior and exterior. The resulting airflow helped stabilise the combustion process and delayed full smoke saturation, providing a realistic representation of typical underground parking conditions.

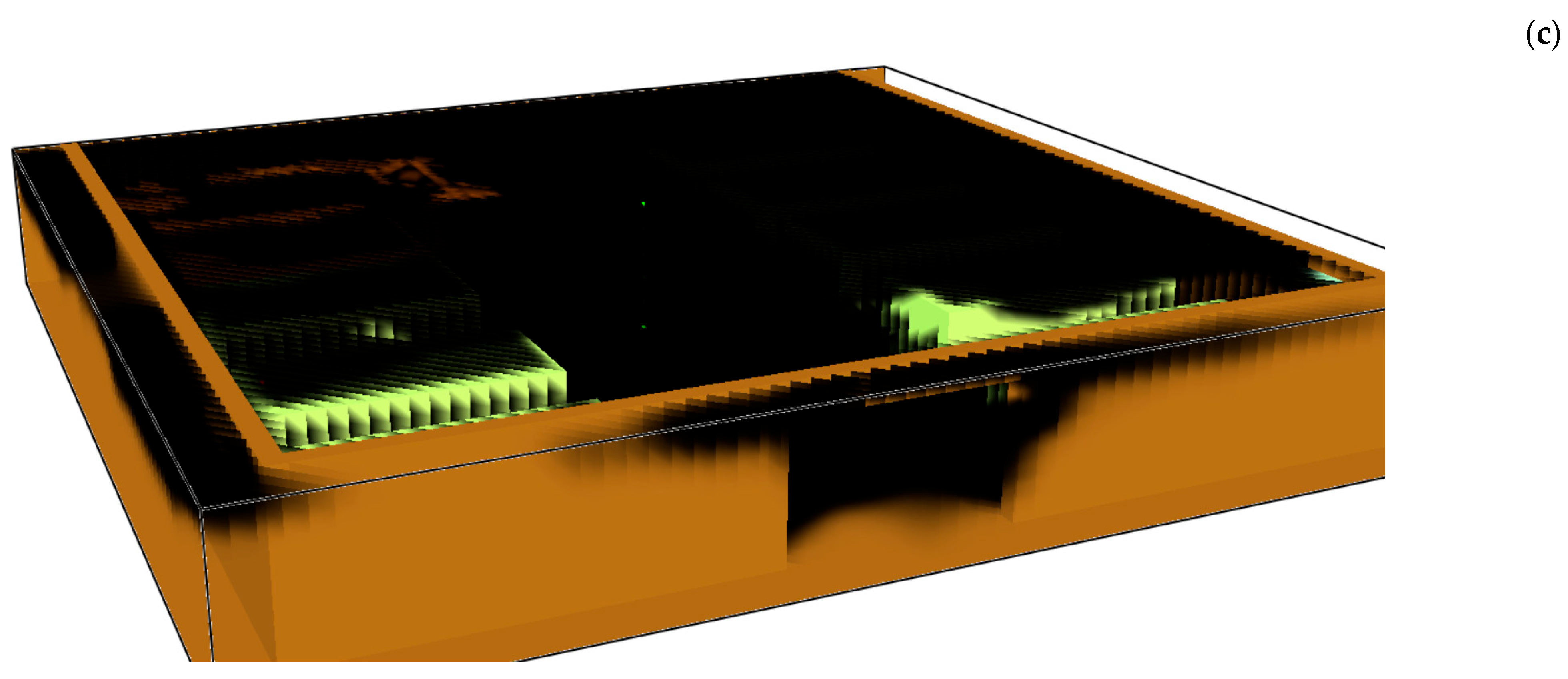

- Increased ventilation, with side openings kept open throughout the simulation. In this case, the lateral openings were kept open from the start of the simulation, enabling continuous air exchange. The total effective opening area was approximately 20 m2 (four side windows of 5 m2 each), supplemented by the 6 m2 entrance. This produced stronger natural convection currents, improving smoke removal but also enhancing flame intensity due to the higher oxygen supply. The airflow induced by temperature-driven buoyancy and pressure differences generated turbulent circulation patterns that increased radiant heat transfer to adjacent vehicles.

2.2. Fire Source Definition and Input Parameters

2.3. Fire Suppression Modelling

3. Results and Discussion—Underground Parking

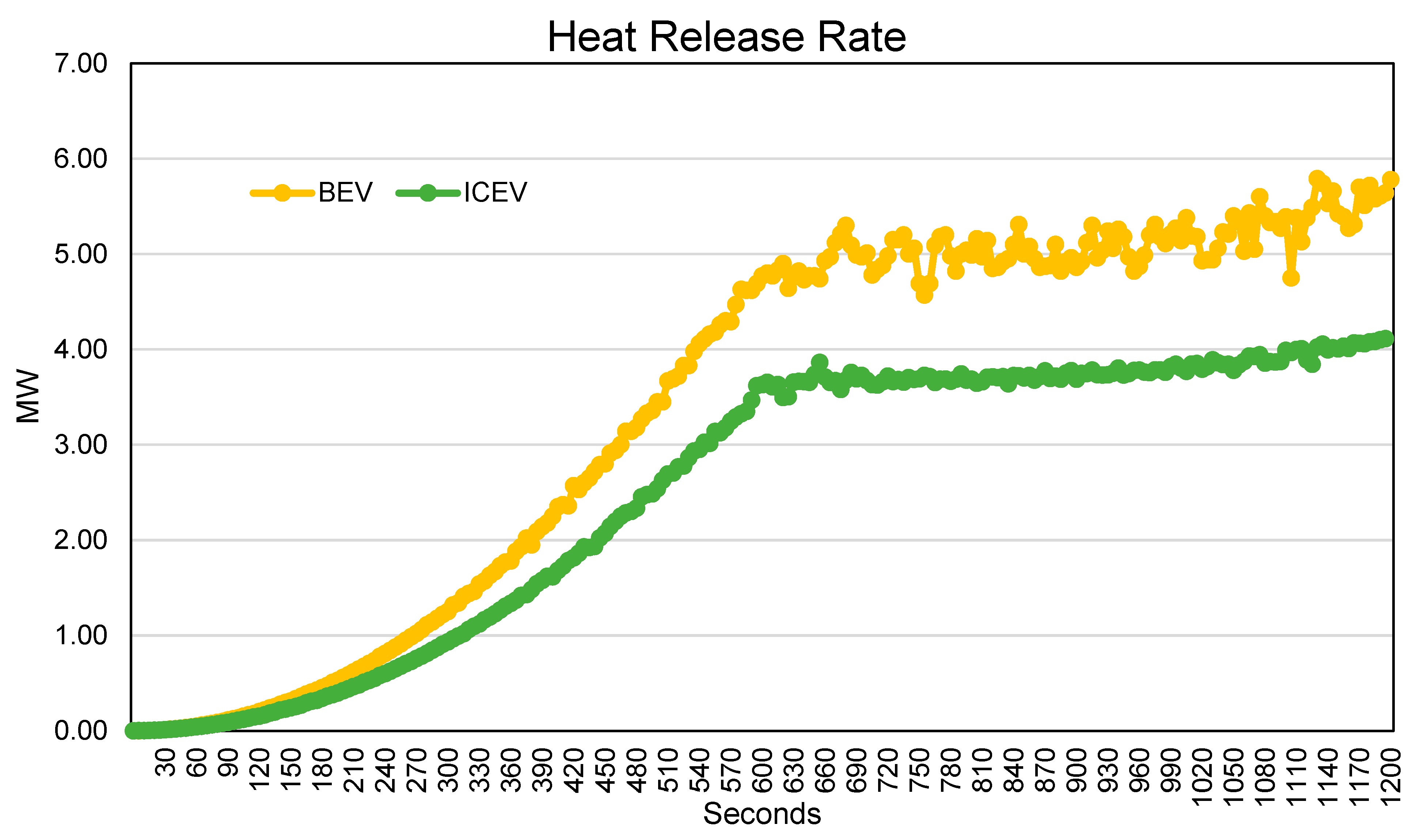

3.1. Fire Development

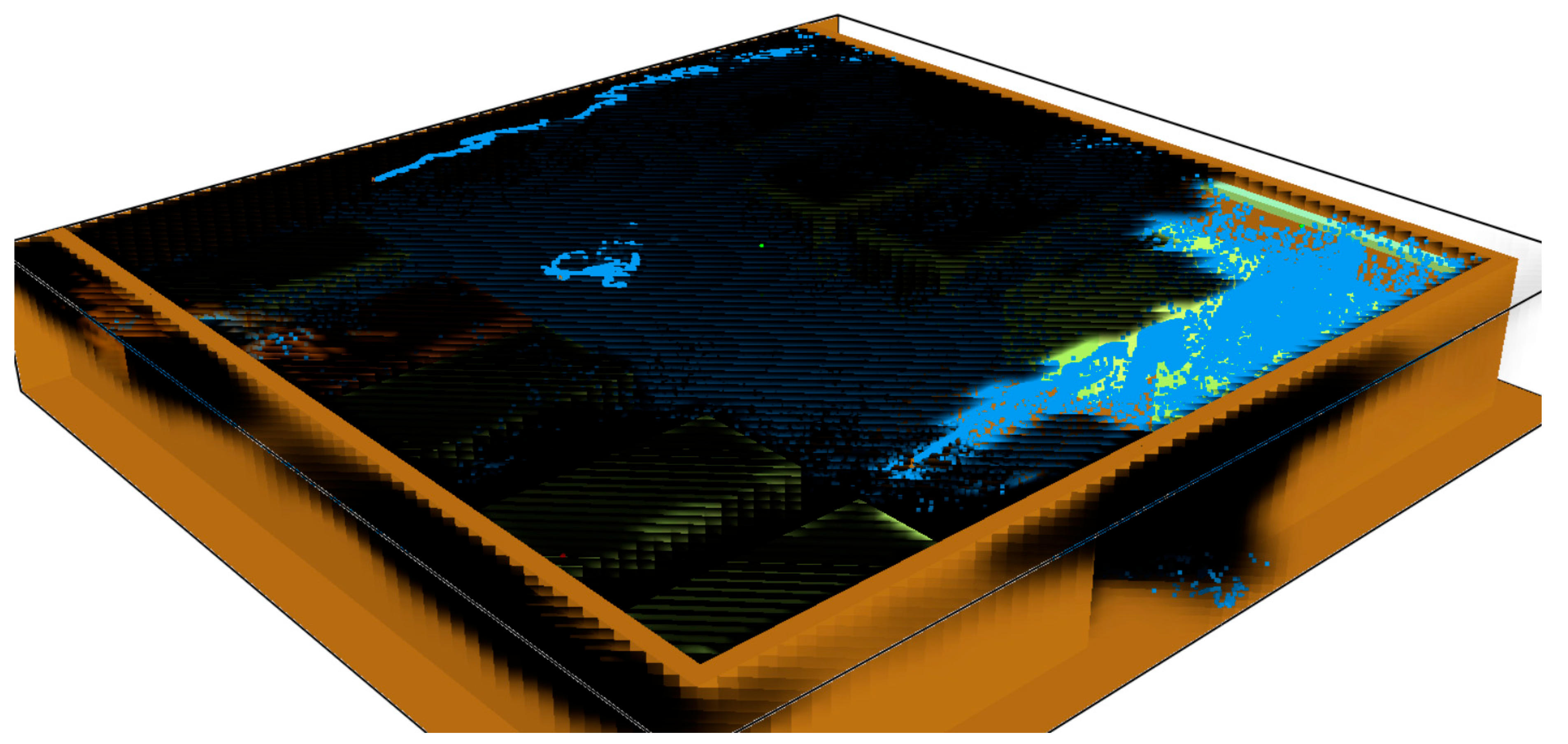

3.2. Effect of the Ventilation Strategy

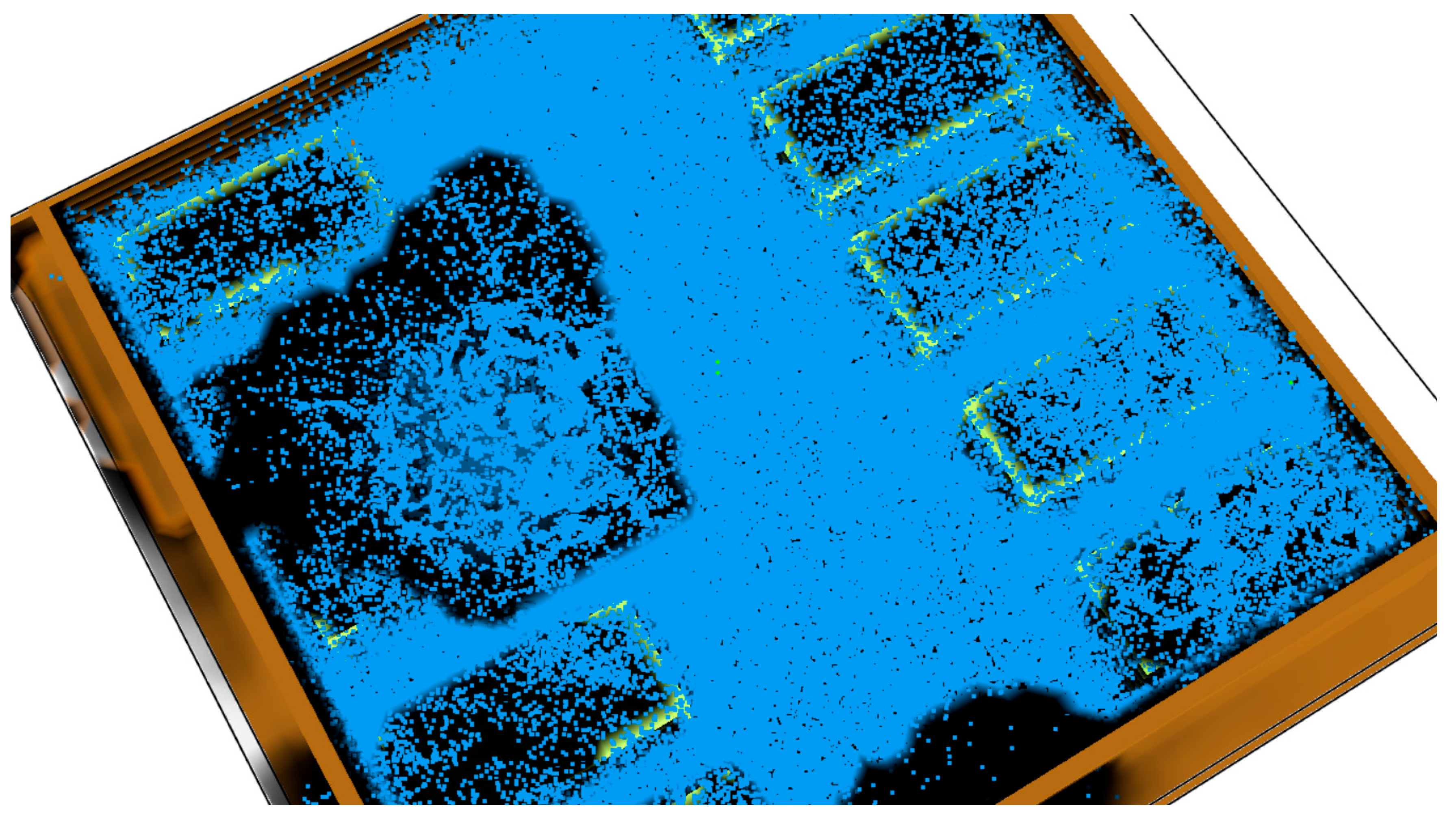

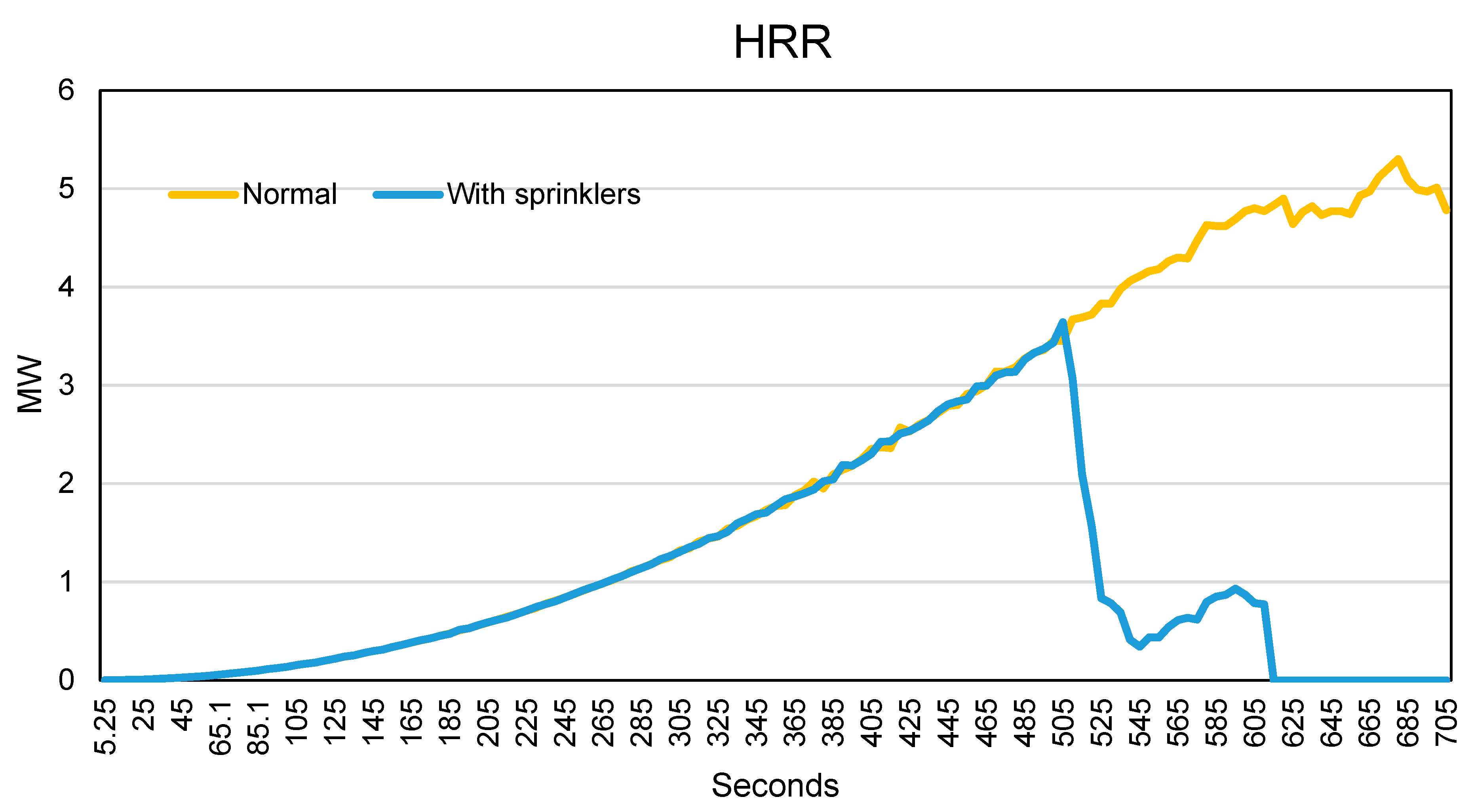

3.3. Fire Suppression

- Early sprinkler activation is critical for limiting fire spread and protecting adjacent vehicles.

- Water spray cooling and steam displacement are effective mechanisms for temperature reduction and oxygen suppression.

- Residual heat management is crucial for BEVs due to possible re-ignition.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICEVs | Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| MHEVs | Mild Hybrid EV |

| HEVs | Hybrid EV |

| PHEVs | Plug-in Hybrid EV |

| BEVs | Battery EV |

| LIB | Li-Ion Battery |

| BMS | Battery Management System |

| HRR | Heat Release Rate |

| FDS | Fire Dynamics Simulator |

| SMW | Smokeview |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| HRRPUA | Heat Release Rate Per Unit Area |

References

- Guo, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Experimental Investigation on Fire Smoke Temperature under Forced Ventilation Conditions in a Bifurcated Tunnel with Fires Situated in a Branch Tunnel. Fire 2023, 6, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturm, P.; Fößleitner, P.; Fruhwirt, D.; Galler, R.; Wenighofer, R.; Heindl, S.F.; Krausbar, S.; Heger, O. Fire tests with lithium-ion battery electric vehicles in road tunnels. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 134, 103695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecocq, A.; Bertana, M.; Truchot, B.; Marlair, G. Comparison of the fire consequences of an electric vehicle and an internal combustion engine vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2. International Conference on Fires in Vehicles-FIVE 2012, Chicago, IL, USA, 27–28 September 2012; SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden: Boras, Sweden, 2012; pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kwon, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Choi, S. Full-scale fire testing of battery electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2023, 332, 120497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, J.L.; Salvi, U.; Kapahi, A. Design fire scenarios for hazard assessment of modern battery electric and internal combustion engine passenger vehicles. Fire Saf. J. 2024, 146, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musso, L.; Donati, S.; Benelli, A.; Sobótka, M.; Bodak, B.; Pachnicz, M.; Fruhwirt, D.; Noone, P.; Knaup, L.; Zirker, C.; et al. Thermal runaway in lithium-ion batteries: Experimental insights from mechanical, thermal, and electrical stress tests. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ouyang, M.; Liu, X.; Lu, L.; Xia, Y.; He, X. Thermal runaway mechanism of lithium ion battery for electric vehicles: A review. Energy Storage Mater. 2018, 10, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, F.; Andersson, P.; Blomqvist, P.; Mellander, B.E. Toxic fluoride gas emissions from lithium-ion battery fires. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturk, D.; Rosell, L.; Blomqvist, P.; Tidblad, A.A. Analysis of Li-Ion Battery Gases Vented in an Inert Atmosphere Thermal Test Chamber. Batteries 2019, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, R.; Shen, Z.; Yu, Q.; Xiong, R.; Shen, W. Towards a safer lithium-ion batteries: A critical review on cause, characteristics, warning and disposal strategy for thermal runaway. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 11, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, R.; Fruhwirt, D.; Papurello, D. A Study on Large Electric Vehicle Fires in a Tunnel: Use of a Fire Dynamics Simulator (FDS). Processes 2025, 13, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Bisschop, R.; Niu, H.; Huang, X. A Review of Battery Fires in Electric Vehicles. Fire Technol. 2020, 56, 1361–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, D.; Jeong, Y.; Moon, M.; Kwon, H.; Han, K.; Kim, H.; Im, H.; Park, Y.; Shin, D.; et al. Assessing fire dynamics and suppression techniques in electric vehicles at different states of charge: Implications for maritime safety. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 64, 105474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, O.; Honkavaara, E. A Review of Vehicles for Fire Suppression. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Considerations for ESS Fire Safety Consolidated Edison New York, NY. 2017. Available online: www.dnvgl.com (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Modern Vehicle Hazards in Parking Garages & Vehicle Carriers. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/education-and-research/research/fire-protection-research-foundation/projects-and-reports/modern-vehicle-hazards-in-parking-garages-vehicle-carriers?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Miechówka, B.; Węgrzyński, W. Systematic Literature Review on Passenger Car Fire Experiments for Car Park Safety Design. Fire Technol. 2025, 61, 2651–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehmer, H.; Klassen, M.; Olenick, S. Modern Vehicle Hazards in Parking Structures and Vehicle Carriers. 2020. Available online: www.nfpa.org/foundation (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Boehmer, H.R.; Klassen, M.S.; Olenick, S.M. Fire Hazard Analysis of Modern Vehicles in Parking Facilities. Fire Technol. 2021, 57, 2097–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohir, M.Z.M.; Spearpoint, M.; Fleischmann, C. Probabilistic design fires for passenger vehicle scenarios. Fire Saf. J. 2021, 120, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Ryu, J.; Ryou, H.S. Experimental Study on the Fire-Spreading Characteristics and Heat Release Rates of Burning Vehicles Using a Large-Scale Calorimeter. Energies 2019, 12, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, H.; Yu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, X. Flame spread and smoke temperature of full-scale fire test of car fire. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2017, 10, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, C.; Yingang, S.; Yuechen, C. Simulation of flames and smoke spreading in an underground garage under different ventilation conditions You may also like Design of Intelligent Garage Control System Based on Internet of Things. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1736, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezinska, D.; Bryant, P. Performance-Based Analysis in Evaluation of Safety in Car Parks under Electric Vehicle Fire Conditions. Energies 2022, 15, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thermal Modeling of the Electric Vehicle Fire Hazard Effects on Parking Building on JSTOR. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27349122 (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Impact of ventilation strategies on the evolution of electric vehicle fire characteristics in ships. Ocean. Eng. 2025, 317, 120080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, C.; Năstase, I.; Bode, F.; Calotă, R. Smoke and Hot Gas Removal in Underground Parking Through Computational Fluid Dynamics: A State of the Art and Future Challenges. Fire 2024, 7, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, K.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, D.K. Study of Fire Dynamic Simulation of Electric Vehicle in Basement Parking; National Fire Service College: Nagpur, India, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olenick, S.; Klassen, M.; Hussain, N. Classification of Modern Vehicle Hazards in Parking Structures & Systems-Ph II. 2024. Available online: www.nfpa.org/foundation (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Parking Garages and EVs. Available online: https://www.nfpa.org/news-blogs-and-articles/blogs/2024/07/12/parking-garages-and-evs?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- AMCRPS Underground Car Parks—Life Cycle Assessment|English Version|Enhanced Reader. Available online: https://projects.arcelormittal.com/media/4kspgix2/underground-car-parks-nl-part-2-lca-2021.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Thermal Properties Database of Building Materials and Technologies. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357355874_Thermal_Properties_of_Building_Materials_-_Review_and_Database/citations (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Properties of Polymers|ScienceDirect. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/monograph/9780080548197/properties-of-polymers (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- E. M. Project Manager H Salley A Lindeman, “NUREG-2178, Vol.1, ‘Refining And Characterizing Heat Release Rates From Electrical Enclosures During Fire (RACHELLE-FIRE), Volume 1: Peak Heat Release Rates and Effect of Obstructed Plume’”. 2016. Available online: https://www.nrc.gov/docs/ML1611/ML16110A140.pdf (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Mishra, R.K.; Sharma, P.K.; Kumar, R. Experimental analysis of glass failure criteria under different thermal conditions. Front. Therm. Eng. 2024, 4, 1488206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, J.; Xiao, H.; Tian, S.; Huang, Y. A comprehensive review on thermal runaway model of a lithium-ion battery: Mechanism, thermal, mechanical, propagation, gas venting and combustion. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Leone, E.; Papurello, D. Fire Safety Analysis of Alternative Vehicles in Confined Spaces: A Study of Underground Parking Facilities. Fire 2026, 9, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9010020

Leone E, Papurello D. Fire Safety Analysis of Alternative Vehicles in Confined Spaces: A Study of Underground Parking Facilities. Fire. 2026; 9(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeone, Edoardo, and Davide Papurello. 2026. "Fire Safety Analysis of Alternative Vehicles in Confined Spaces: A Study of Underground Parking Facilities" Fire 9, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9010020

APA StyleLeone, E., & Papurello, D. (2026). Fire Safety Analysis of Alternative Vehicles in Confined Spaces: A Study of Underground Parking Facilities. Fire, 9(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fire9010020