Abstract

The growing energy demand in the residential sector, driven by the extensive use of air conditioning systems, poses serious environmental and economic challenges. A sustainable alternative is the use of efficient insulating materials derived from waste resources. This study presents the synthesis of glass–ceramic foams produced from recycled glass (90 wt%), pumice (5 wt%), and limestone (5 wt%), sintered at 800 °C for 10 min. The resulting foams exhibited a low apparent density of 684 kg/ and thermal conductivity of 0.09 W/m·K. These were incorporated into composite insulating panels composed of 70 wt% ceramic pellets and 30 wt% Portland cement, achieving a thermal conductivity of 0.18 W/m·K. The panels were evaluated in a 64.8 social housing model located in Chihuahua, Mexico, using TRNSYS v.17 to simulate annual energy performance. Results showed that applying a 1.5-inch ceramic foam panel reduced the annual energy demand by 16.9% and the total energy cost by 14.7%, while increasing the panel thickness to 2 in improved savings to 18.4%. Compared with expanded polystyrene (EPS), which achieved 24.9% savings, the proposed ceramic panels offer advantages in fire resistance, durability, local availability, and environmental sustainability. This work demonstrates an effective, low-cost, and circular-economy-based solution for improving thermal comfort and energy efficiency in social housing.

1. Introduction

Residential space conditioning represents a significant portion of global energy consumption, contributing considerably to carbon dioxide () emissions [1,2,3]. In Mexico, social interest housing is often designed and built without adequately considering the local climatic and geographical conditions [4]. This lack of integration between architectural design and the natural environment results in the need for intensive use of artificial heating and cooling systems to achieve basic thermal comfort levels [5]. Given the increasing construction rate and high demand for this type of housing, a significant rise in associated energy consumption is expected. Social interest housing consists of low-cost dwellings intended for low-income families, typically ranging from 40 to 70 [6] in floor area. These buildings usually feature simple designs and are constructed with conventional materials such as concrete blocks and cement slab roofs [7,8]. The main issue lies in the absence of thermal insulation, which leads to extreme indoor temperatures, particularly in regions with harsh climates, increasing energy consumption and negatively affecting residents’ well-being [9]. This situation not only raises air-conditioning costs but also poses health risks due to prolonged thermal stress [10]. To address this challenge, it is essential to incorporate thermal insulation solutions into construction practices. Currently, one of the most widely used options includes polymeric insulators such as polyurethane and expanded polystyrene foams, valued for their low thermal conductivity and ease of installation [11] These materials offer high thermal efficiency by significantly reducing heat transfer, while also being lightweight and easy to handle [12]. However, they also have notable limitations. They are susceptible to degradation under extreme conditions, such as prolonged exposure to ultraviolet radiation or high temperatures [13]. Moreover, many of these materials are flammable and can pose fire risks even when containing flame retardants as they may release toxic gases during combustion [14]. Another critical factor is cost, which tends to be relatively high for the average budget of families living in social housing. Additionally, their application often requires supplementary protective layers, such as waterproof coatings, increasing both initial and long-term maintenance costs [15]. A viable, cost-effective, and sustainable alternative is represented by glass–ceramic foams produced from vitreous waste materials [16]. These foams offer good thermal performance at a lower cost, capable of reducing indoor temperatures by up to 8 °C. Furthermore, they are more resistant and safer than traditional synthetic materials [17]. Their implementation allows for reduced energy consumption, improved thermal comfort, and decreased negative environmental impacts [18]. Production can be localized using industrial waste such as recycled glass, promoting circular economy models and generating regional employment [19]. Although the synthesis of glass–ceramic foams from recycled glass has been explored in prior work, this study introduces distinct advancements that address both technical and social dimensions of sustainable insulation in the context of social housing. The novelty of this work lies in four key aspects: (i) the exclusive use of post-consumer glass bottles collected from municipal landfills, thereby directly valorizing urban solid waste that would otherwise contribute to environmental degradation; (ii) the formulation of the foam using locally sourced natural additives with limestone and pumice, which enhances regional material circularity and reduces raw material costs; (iii) the development of easy-to-apply insulating panels by combining 70% glass–ceramic foam with 30% Type I Portland cement, ensuring compatibility with conventional construction practices in social housing; and (iv) a comprehensive evaluation framework that integrates materials characterization, including microstructural analysis via computed tomography [20,21] and the measurement of physical and thermal properties such as apparent density and thermal conductivity [22] with dynamic energy simulations performed using the software TRNSYS v.17 [23]. The simulations were applied to a standard social housing unit located in Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico, and compared three scenarios: no insulation, conventional polyurethane insulation, and the developed ceramic-cement insulating panels. This approach enabled the quantification of annual energy savings and the assessment of economic feasibility under real climatic conditions. Therefore, the objective of this work is to synthesize glass–ceramic foams from municipal waste glass, fabricate composite insulating panels, and evaluate their thermal and economic performance in a representative model of Mexican social interest housing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of Ceramic Foams

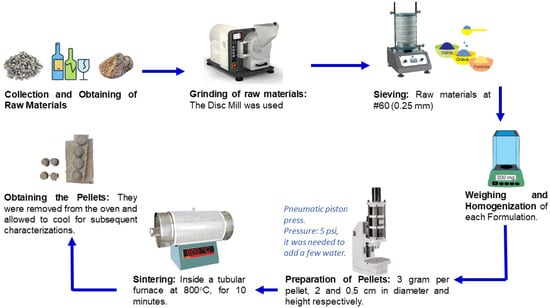

The raw materials used for the synthesis of glass–ceramic foams included recycled glass, pumice, and limestone. The recycled glass was collected from discarded bottles found in urban landfills or sourced from specialized recycling centers. The bottles were washed to remove all dirt and labeled. Pumice and limestone were obtained from local geological deposits in the vicinity of Chihuahua City, Mexico. Prior to use, all materials were processed by grinding in a BICO disc mill. Each component was milled separately and sieved to a particle size of 60 mesh (250 microns), ensuring uniformity in particle size distribution, an essential factor for achieving homogeneous mixing and reproducibility in the final formulation. The chemical composition of the raw materials determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) is reported in the Supplementary Materials (Table S7). The mixture was prepared with a composition of 90% recycled glass, 5% pumice, and 5% limestone by weight. This formulation was selected based on prior studies, such as Hisham et al. (2021) [24], who analyzed foam glass–ceramic compositions derived from waste glass sintered at varying temperatures. The foaming mechanism was governed by the controlled decomposition of and the viscosity of the softened glass phase [25]. Additional discussion of the viscosity–decomposition relationship, supported by dilatometry curves of glass and pumice, is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S3). Figure 1 illustrates the general flow diagram of the experimental procedure. For the pellet fabrication, 3 g of the homogeneous mixture were weighed using an analytical balance and pressed into cylindrical green bodies (0.5 cm diameter × 2.0 cm height) using a hydraulic press under 60 psi. The compacted pellets were then sintered in a Thermoline tube furnace (model 6500) at 800 °C for 10 min. The heating rate was approximately 155 °C/min from ambient temperature to 800 °C, followed by a 10-min dwell at the target temperature. Cooling occurred naturally at an average rate of 30 °C/min down to 50 °C. These conditions were selected to ensure uniform foaming and to avoid structural collapse or excessive coalescence during expansion. The softening behavior of post-consumer glass used in this work (softening point = 547 °C) confirms that the glass phase was sufficiently viscous at 800 °C to enable controlled foaming. A comparative table of softening points for different glass types is provided in the Supplementary Materials (Table S6). This thermal treatment induced material expansion through the decomposition of calcium carbonate , releasing carbon dioxide and forming the characteristic porous structure of ceramic foam. The dilatometric behavior of raw materials supporting this temperature selection is discussed in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S3). The sintered pellets were subsequently subjected to physical and microstructural characterization.

Figure 1.

Process for the synthesis of glass–ceramic foam pellets.

2.2. Manufacturing of Insulating Panels (Ceramic Foam–Cement)

The insulating panels were fabricated by combining the previously sintered ceramic foam pellets with Type I Portland cement in a proportion of 70% pellets to 30% cement by weight. The dry components were homogenized, and water was added at 40% of the total dry weight to activate the mixture. The resulting paste was poured into square molds measuring 20 cm per side and left to cure under ambient conditions for 48 h. After demolding, the panels were evaluated for physical and thermal properties. Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of the panel manufacturing process. The manufactured panels were intended for use as external thermal insulation layers in building envelopes. Their physical characteristics, including density and thermal conductivity, were later used as input parameters for the annual energy simulation described in Section 3.4. This simulation aimed to evaluate the panels’ thermal performance in a standard social housing model located in Chihuahua, Mexico.

Figure 2.

Manufacturing process of insulating panels (Pellets–Cement).

2.3. Material Characterization

The physical and thermal properties of both the sintered pellets and the manufactured insulating panels were evaluated through standardized tests. The apparent density was determined using the Archimedes principle in accordance with ASTM D792-08, “Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity of Plastics by Displacement,” [26] using an Ohaus Explorer analytical balance. Each measurement was repeated five times to ensure data consistency and statistical reliability. Density was determined using five replicate samples for both the pellets and the panels, while thermal conductivity measurements were performed on three replicates. The thermal conductivity was measured using a Unitherm Model 2022 apparatus following the ASTM E1530-19 standard, “Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Resistance to Thermal Transmission by the Guarded Heat Flow Meter Technique” [27]. The internal porosity and microstructure of the sintered pellets were analyzed through X-ray computed tomography (CT) using a NIKON XTH225 microtomograph. This technique enabled the visualization and evaluation of pore distribution, structural density variations, and the presence of surface layers. Structural 3D models were reconstructed using SketchUp software to aid in the interpretation and presentation of CT scan. The data obtained from these characterization methods were subsequently used as input parameters for the energy simulation of thermal performance in the modeled housing unit, as described in Section 3.4. Detailed measurement data and statistical analysis of density and thermal conductivity for both pellets and panels are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S1–S4).

3. Results and Discussion

The results include the characterization of the synthetized pellets: morphology and internal microstructure. The density and thermal conductivity were calculated for both pellets and composites panels. The energy demand and economic analysis is based on a social housing using different insulation configurations including the panels with the synthesized pellets. The crystalline phases of the raw materials were confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), which identified calcite as the main crystalline phase in limestone and a predominantly amorphous structure in pumice (see Supplementary Materials, Figure S4).

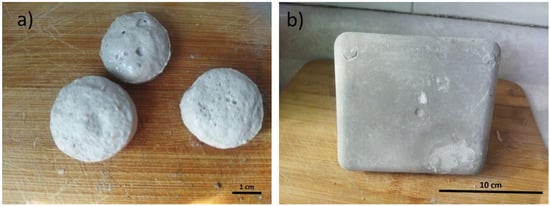

3.1. Morphology and Expansion Behavior of Pellets

After sintering at 800 °C for 10 min, the ceramic foam pellets exhibited uniform expansion and a characteristic convex shape on the upper surface, as shown in Figure 3a. This behavior is attributed to the release of during the thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate, which generates internal porosity and promotes cellular structure formation. In contrast, the fabricated insulating panels (Figure 3b) presented a smooth, continuous surface, with the cement matrix effectively embedding and sealing the porous pellets. This configuration results in a mechanically stable and visually uniform composite material suitable for application as an external insulating layer. Quantitative porosity analysis and pore size distribution obtained by optical microscopy are shown in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S2).

Figure 3.

(a) Pellets 5-5-90 synthesized at 800 °C for 10 min. (b) Insulating panel composed of 70% pellets and 30% cement (0.2 × 0.2 m).

3.2. Internal Microstructure of Ceramic Pellets

X-ray computed tomography (CT) (Figure 4) revealed a pore distribution characterized by a dense outer shell and a more porous core, suggesting competing effects on the thermal and mechanical behavior of the pellets [28]. While the compact skin may enhance handling strength, abrasion resistance, and pellet–cement bonding, it could also provide a preferential path for conductive heat transfer. Conversely, the porous core, rich in closed cavities, is likely the main contributor to the overall low thermal conductivity measured (0.09 W··). To more precisely quantify these competing contributions and establish stronger structure property correlations, future studies should incorporate voxel-resolved image analysis (pore size distribution, connectivity, tortuosity, and specific surface area) combined with effective-medium or pore-network modelling. Complementary tests such as uniaxial compression, water absorption, and permeability would also help to validate the role of the shell in defining mechanical performance and durability. Moreover, process adjustments, including control of heating rate, particle size/distribution, and green compaction pressure, may minimize bubble coalescence and promote a more homogeneous, predominantly closed-cell microstructure, which is expected to further reduce thermal conductivity while preserving mechanical integrity for panel fabrication.

Figure 4.

X-ray Computed Tomography: (a) profile and (b) top view of sintered pellets.

3.3. Density and Thermal Conductivity

Table 1 summarizes the average values of apparent density and thermal conductivity for both the pellets and the composite panels. The sintered pellets exhibited a low density of 684 kg/ and thermal conductivity of 0.09 W/(m·K), consistent with intermediate-performance insulation materials such as cellular concrete. The incorporation of cement in the composite panels increased both properties. Density rose to 926.7 kg/ and thermal conductivity doubled to 0.18 W/(m·K), attributed to the denser nature of the cement matrix and partial loss of porosity due to pellet encapsulation.

Table 1.

Density and thermal conductivity values for pellets and the composites panels.

For a comparative summary of density and thermal conductivity with other insulating materials, see Supplementary Materials (Table S5).

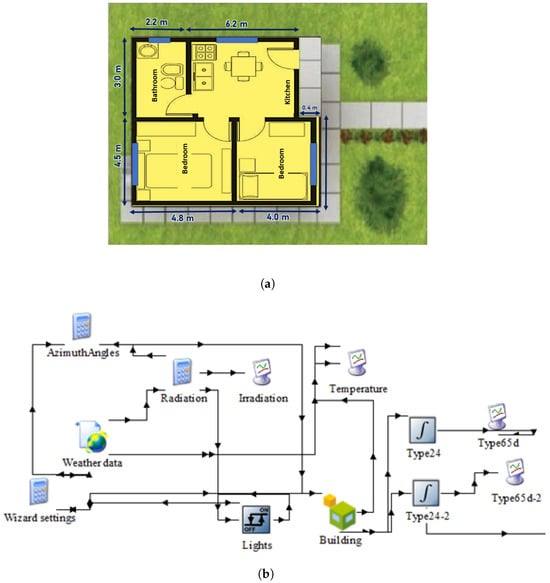

3.4. Housing Model and Simulation Setup

To evaluate the thermal performance of the proposed material, a social housing unit with a total floor area of 64.8 and internal volume of 129.6 was modeled. The house includes two bedrooms, a living room, and a kitchen (Figure 5a). Using Google SketchUp 8 [29], the building geometry was recreated and exported into the TRNBuild module [30] of TRNSYS v.17 for simulation (Figure 5b). The model incorporated realistic thermal properties of construction materials (Table 2), and climatic data were provided by the Meteonorm module [31] for Chihuahua, Mexico, representing a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY). Thermal comfort was defined in the range of 20–25 °C. Indoor temperatures outside this band required the use of heating or cooling systems, and the associated energy demand was recorded over 8760 h. The simulation considered typical boundary conditions for residential buildings in Chihuahua, with indoor comfort temperatures maintained between 20–25 °C. A simple HVAC control loop (ideal air-conditioning system) was used to restore indoor temperature to the comfort range. Internal heat gains from occupants, equipment, and lighting were set to 3.5 W/, following standard residential occupancy assumptions in TRNSYS models. It should be noted that this study does not address the long-term stability of the thermal performance of insulating materials, including aging mechanisms such as moisture absorption, freeze–thaw cycles, carbonation, or UV-induced degradation. These factors are crucial for evaluating the durability and viability of insulation systems on an industrial scale and will be the focus of future research.

Figure 5.

(a) Social housing plan. (b) TRNSYS model used for the simulation.

Table 2.

Thermal properties of construction materials used in the Social Housing unit.

Insulation thickness rationale (Mexico standards). In Mexico, NOM-020-ENER-2011 is a performance-based regulation for building envelopes, which limits the total annual heat gain of a proposed building compared to a reference model but does not prescribe fixed insulation thicknesses. Therefore, the selection of 1.5-inch and 2-inch layers was guided by thermal-resistance targets defined in NMX-C-460-ONNCCE-2009, which specifies minimum R-values for roofs and walls by climate zone.

Considering the measured thermal conductivity of the developed composite panel (0.18 W/m K), the 1.5-inch (0.038 m) and 2-inch (0.051 m) panels provide R-values of approximately 0.21 K/W and 0.28 K/W, respectively. When combined with other envelope layers (block, plaster, air films), these assemblies align with the overall R-values typically required to comply with NOM-020 performance criteria for hot, dry regions such as Chihuahua.

Additionally, these thicknesses correspond to standard commercial dimensions for insulation panels commonly used in Mexican housing projects (e.g., EPS and polyurethane panels of 1–2 inches), ensuring material availability, constructibility, and cost competitiveness. Their use thus reflects both regulatory consistency and market practice in the national context.

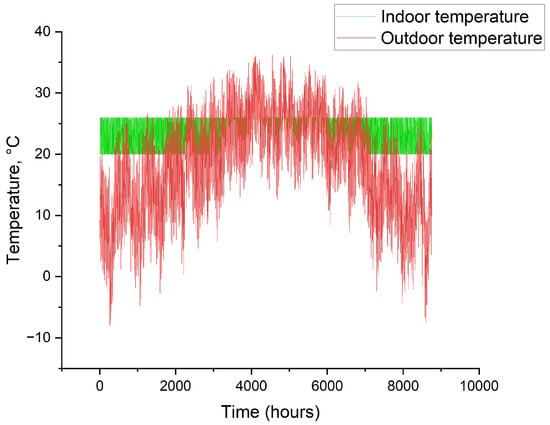

3.5. Energy Performance of Insulating Systems

To evaluate the effectiveness of the ceramic foam insulation, thermal simulations were performed over a one-year period using TRNSYS v.17. The hourly temperature profile of Chihuahua City, Mexico, was used as input, representing a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY). Figure 6 presents a comparison between the outdoor air temperature and the indoor temperature range defined for thermal comfort (20–25 °C). The outdoor temperature fluctuated between −7 °C in winter and nearly 36 °C in summer. The green band in the figure represents the comfort zone, while the red band illustrates the hourly outdoor temperature variation throughout the year. The simulation results demonstrated that, in the absence of insulation, the indoor temperature followed outdoor fluctuations more aggressively, exceeding the comfort range during both summer and winter. When insulation was applied, the indoor temperature remained within the defined comfort range for longer periods, reducing the need for active heating and cooling systems. Applying a 1.5-inch external ceramic foam panel on walls and roofs resulted in a 16.9% reduction in annual energy demand compared to the uninsulated baseline. Although expanded polystyrene achieved a higher reduction of 24.8%, the ceramic alternative offers advantages in terms of cost, safety, and long-term durability.

Figure 6.

Hourly temperatures outside and inside the simulated home in a typical meteorological year in Chihuahua City, Chih.

3.6. Hourly Energy Demand Analysis

Figure 7 presents the annual hourly energy demand required to maintain indoor temperatures within the thermal comfort range (20–25 °C) in the modeled social housing unit. The simulation differentiates between energy required for heating (primarily during winter) and cooling (during summer), allowing for the identification of critical demand periods. The graph reveals that the building, when uninsulated, requires substantial energy input throughout the year to compensate for extreme fluctuations in outdoor temperature. Peak heating demand occurs between December and February, while cooling demand increases notably between May and September.

Figure 7.

Annual hourly heating/cooling energy demand to maintain the comfort range inside the simulated home.

When the ceramic foam insulation was applied, both heating and cooling energy requirements were noticeably reduced. The material acted as a thermal buffer, mitigating rapid indoor temperature changes and decreasing peak loads. Compared to the baseline condition, the simulation showed a 16.9% overall reduction in energy demand with the 1.5-inch ceramic foam panels. These findings confirm that the developed ceramic insulation effectively reduces annual energy consumption while enhancing indoor comfort, even in a climate with high seasonal temperature variation such as Chihuahua City. Simulation results indicate that applying a 1.5-inch external ceramic foam panel on walls and roofs reduced annual energy demand by 16.9% compared to an uninsulated home. Expanded polystyrene insulation yielded a higher reduction of 24.8%, but presents limitations such as flammability, higher cost, and environmental impact. Figure 8 compares monthly heating and cooling demands for each scenario. Notably, the ceramic panels delivered consistent performance year-round and significantly reduced peak loads during summer months, enhancing thermal comfort and reducing energy expenditure.

3.7. Economic Analysis

The estimated economic savings associated with each insulation system were calculated based on electricity consumption for cooling and gas consumption for heating.

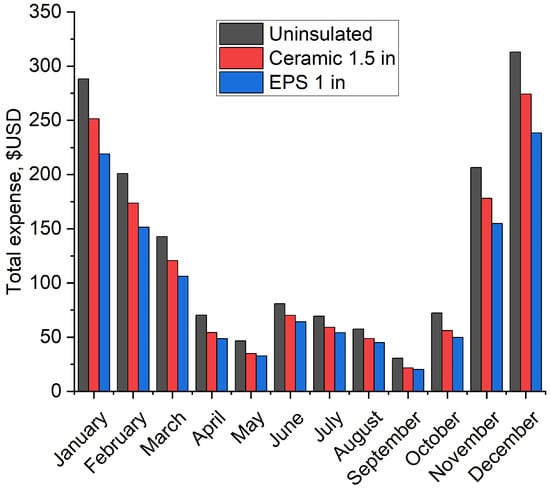

Figure 8.

Cooling + Heating energy demand for each month of a Typical Meteorological Year in the city of Chihuahua, Chih.

3.8. Economic Cost Estimation

To assess the economic viability of the developed ceramic foam insulation panels, a comparative analysis of annual energy costs was conducted based on the simulated energy demand required to maintain indoor thermal comfort in a social housing unit located in Chihuahua, Mexico. The simulation considered two energy sources: electricity for cooling during summer and butane gas for heating during winter. Hourly energy demand values obtained from TRNSYS v.17 were combined with representative residential energy prices in Mexico as of January 2025: $0.055 USD/kWh for electricity and $1.03 USD/kg for butane gas. These rates correspond to the intermediate residential tariff bracket and average national gas price, respectively. Figure 9 illustrates the monthly energy expenditure for each insulation scenario. The uninsulated housing unit exhibited the highest annual cost, primarily due to increased summer cooling and winter heating requirements. In contrast, the application of a 1.5-inch ceramic foam insulation panel resulted in a 14.7% annual cost reduction, while increasing the panel thickness to 2 inches further improved performance, achieving an 18.4% reduction in total energy expenditure.

Figure 9.

Monthly energy expenditure for cooling (electricity) and heating (butane gas) across the four insulation scenarios over a Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) in Chihuahua, Mexico.

Table 3 summarizes the cumulative annual costs for each case:

Table 3.

Annual accumulated energy costs and savings for each insulation configuration.

- No insulation;

- 1.5-inch ceramic foam panel;

- 2-inch ceramic foam panel;

- 1-inch expanded polystyrene (EPS) panel.

The best-performing scenario was the EPS panel, which led to a 24.9% reduction in energy costs. However, despite its higher thermal performance, expanded polystyrene presents significant disadvantages, including flammability, environmental persistence, susceptibility to UV degradation, and higher long-term maintenance costs due to its shorter lifespan. In contrast, the ceramic foam panels composed of 90% recycled glass, 5% pumice, and 5% limestone, demonstrated adequate thermal performance (0.18 W/m·K for the composite panel), high mechanical integrity, and strong durability, while being produced from locally sourced, low-cost materials. Their fire resistance, environmental sustainability, and compatibility with regional waste streams make them a technically and economically viable solution for insulating social housing in extreme climates.

4. Conclusions

This work successfully demonstrates the development of a high-performance thermal insulator from 100% waste derived and locally available raw materials post-consumer glass, pumice, and limestone, processed via a low-energy route (800 °C for 10 min). The resulting glass–ceramic foam pellets exhibit a low apparent density of 684 kg/ and an excellent thermal conductivity of 0.09 W/m·K. This outstanding insulating performance stems from their porous microstructure: closed pores effectively trap air and suppress heat transfer by conduction and convection, the reduced solid matrix minimizes conductive pathways, and pore scattering attenuates radiative heat transfer. Together, these microstructural features account for the low thermal conductivity observed in both the pellets and the composite panels. When formulated into panels (70% foam + 30% Portland cement), the material retains competitive insulating properties (926.7 kg/, 0.18 W/m·K), placing it within the performance range of lightweight insulating concretes. Dynamic energy simulations (TRNSYS v.17) for a standard 60 social housing unit in Chihuahua, Mexico, showed that a 1.5-inch panel layer reduces annual energy demand by 16.9% (equivalent to 14.7% in cost savings), with improvements to 18.4% at 2 inches. While expanded polystyrene (EPS) achieves higher energy savings (24.9%), it does so at the expense of flammability, toxic emissions during combustion, petroleum dependence, and limited durability under UV exposure. In contrast, the ceramic-based panels are non-combustible, chemically stable, moisture resistant (due to a sealed surface layer and limited open porosity), and fabricated from urban waste, offering a circular, safe, and socially equitable alternative. These quantified results confirm that the developed material meets the technical, economic, and environmental requirements for scalable application in social housing. To advance toward real-world implementation, future work will focus on three concrete steps: (1) pilot-scale production to validate process reproducibility and cost structure; (2) long-term durability testing under real climatic conditions (including freeze, thaw, moisture, and thermal cycling); and (3) optimization of the cement–foam interface to further reduce thermal conductivity without compromising mechanical integrity. This study thus provides not only a viable insulation solution but also a replicable framework for transforming municipal waste into high-value, climate-resilient building materials.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ceramics8040153/s1: Tables S1–S4: Measurements of density and thermal conductivity of Pellets and Insulating Panels; Figure S1: Porosity measurement using optical microscopy (example); Figure S2: Histogram of the classes obtained; Table S5: Density and thermal conductivity values of different insulating materials; Figure S3: Dilatometry measurement: (a) bottle glass, (b) pumice; Figure S4. XRD analysis: (a) Limestone, (b) Pumice; Table S6. Density and thermal conductivity values of different insulating materials; Table S7. X-ray fluorescence analysis of raw materials.

Author Contributions

N.M.T.-G.: Writing—original draft, Investigation. D.L.-G.: original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis. C.C.-G.: Writing—conceptualization original draft, Project administration, J.E.-B.: Writing, Investigation. I.V.-D. Data collection, analsys. R.B.-C.: Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the support from CIMAV, and Nanotech for providing the necessary infrastructure. Special thanks for data acquisition support to Andrés González (XRD), Gregorio Vazquez (tomography), Ramón Vargas (XRF) and Miguel H. Bocanegra (density).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aydin, E.; Brounen, D. The impact of policy on residential energy consumption. Energy 2019, 169, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Yan, H.; Zhang, S.; Wei, C. Does urbanization increase residential energy use? Evidence from the Chinese residential energy consumption survey 2012. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 59, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Hwang, B.G.; Kua, H.W. Reducing residential energy consumption through a marketized behavioral intervention: The approach of Household Energy Saving Option (HESO). Energy Build. 2021, 232, 110621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, W.; Herrera, C.A. Ventilación pasiva y confort térmico en vivienda de interés social en clima ecuatorial. Ing. Desarro. 2017, 35, 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera, F. Aislantes térmicos para viviendas de la costa ecuatoriana. Yachana Rev. Cient. 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón Duran, A. Propuesta y Diseño de un Sistema Modular para la Construcción de Viviendas de Interés Social en México. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, J.B.; Cabanillas, R.E.; Hinojosa, J.F.; Borbón, A.C. Estudio numérico de la resistencia térmica en muros de bloques de concreto hueco con aislamiento térmico. Inf. Tecnol. 2011, 22, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, J.D.; Gómez, A.F.; Calisto Aguilar, M.; Diulio, M.d.l.P.; Basualdo, D.E.; Reus Netto, G.; Berardi, R.N.; Camporeale, P.; Giraldo, W.; Fuentealba, M.d.l.Á.; et al. Hacia un modelo de certificación de edificios sustentables adecuado al contexto regional. In Proceedings of the XXXVI Encuentro y XXI Congreso ARQUISUR (San Juan, 2017), San Juan, Argentina, 6–8 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mercier, D.; Dutil, Y.; Rousse, D.; Pronovost, F.; Boudreau, D.; Hudon, N.; Castonguay, M. Los aislamientos térmicos naturales: Construcción ecológica y eficiencia energética. In Proceedings of the Coloquio Universitario Franco-Québécois, Saguenay, QC, Canada, 18 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, J.F.P.; Fernández, P.M.E. Propuestas de Mejora para Incrementar la Calidad del Hábitat en Viviendas de Interés Social en México: Caso de Estudio Las Dunas. Master’s Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel Bolaños, Á.; ATEPA. El aislamiento con poliuretano en la construcción sostenible. In Proceedings of the Congreso Nacional de Construcción Sostenible y Soluciones Ecoeficientes (2º. 2012. Sevilla), Seville, Spain, 21–23 November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaei, B.; Najafi, M.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Abtahi, M.; Zhang, C. A review on the applications of polyurea in the construction industry. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 2797–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistry, M.; Prajapati, V.; Dholakiya, B.Z. Redefining construction: An in-depth review of sustainable polyurethane applications. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 3448–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somarathna, H.; Raman, S.; Mohotti, D.; Mutalib, A.; Badri, K. The use of polyurethane for structural and infrastructural engineering applications: A state-of-the-art review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 190, 995–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Barragán, J.; Domínguez-Malfavón, L.; Vargas-Suárez, M.; González-Hernández, R.; Aguilar-Osorio, G.; Loza-Tavera, H. Biodegradative activities of selected environmental fungi on a polyester polyurethane varnish and polyether polyurethane foams. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5225–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Boccaccini, A.; Lee, P.; Kershaw, M.; Rawlings, R. Glass ceramic foams from coal ash and waste glass: Production and characterisation. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2006, 105, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, B.; Zhang, S. A review of glass ceramic foams prepared from solid wastes: Processing, heavy-metal solidification and volatilization, applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez Campos, E.D. Vidrio Espuma a Partir de Desecho de Vidrio y Perlita Mineral Como Aislante Térmico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, San Nicolás de los Garza, Mexico, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- de Salazar, J.G.; Barrena, M.; Soria, A.; Menéndez, M.; González, A. Obtención de recubrimientos vitrocerámicos esponjosos sobre materiales de naturaleza férrea. Boletín Soc. Espa Nola Cerámica Vidr. 2001, 40, 295–299. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzawy, E.M.; El-Bassyouni, G.T.; Abd El-Shakour, Z.A.; Nabawy, B.S. Manufacture of low thermal conductivity anorthite ceramic foam using silica fume, aluminum slag, and limestone. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 7977–7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appoloni, C.R.; Fernandes, C.P.; Innocentini, M.D.d.M.; Macedo, Á. Ceramic foams porous microstructure characterization by X-ray microtomography. Mater. Res. 2004, 7, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Ji, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Z. Preparation of glass ceramic foams for thermal insulation applications from coal fly ash and waste glass. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 112, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J. Energy simulation software for buildings: Review and comparison. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Information Technology for Energy Applicatons-IT4Energy, Lisabon, Portugal, 6–7 September 2012; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hisham, N.A.N.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Aziz, S.H.A.; Muhammad, F.D. Comparison of foam glass-ceramics with different composition derived from ark clamshell (ACS) and soda lime silica (SLS) glass bottles sintered at various temperatures. Materials 2021, 14, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- König, J.; Petersen, R.R.; Yue, Y. Influence of the glass–calcium carbonate mixture’s characteristics on the foaming process and the properties of the foam glass. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 34, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D792-08; Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1991.

- ASTM E1530-19; Standard Test Method for Evaluating the Resistance to Thermal Transmission by the Guarded Heat Flow Meter Technique. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- Batool, F.; Rafi, M.M.; Bindiganavile, V. Microstructure and thermal conductivity of cement-based foam: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2018, 20, 696–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J. Google SketchUp Pro 8 paso a paso en Español; GetProBooks: Brea, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Delcroix, B.; Kummert, M.; Daoud, A.; Hiller, M. Improved conduction transfer function coefficients generation in TRNSYS multizone building model. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation 2013, IBPSA, Chambéry, France, 25–28 August 2013; Volume 13, pp. 2667–2674. [Google Scholar]

- Remund, J. Quality of meteonorm version 6.0. Europe 2008, 6, 389. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).