1. Introduction

Obtaining high-quality and durable ceramic products—porcelain stoneware based on local natural mineral raw materials—is an urgent task. The quality and durability of high-strength porcelain stoneware is characterized by increased compressive strength and frost resistance. Porcelain stoneware in particular, consisting of quartz, feldspar and kaolin, has a unique combination of mechanical strength and chemical inertness. The microstructure of porcelain stoneware, characterized by large quartz grains, mullite crystals and an amorphous silicate phase, determines its unique properties.

Currently, there are several ceramic materials that meet the needs of interior wall and floor coverings: decorative stones, including granite, marble, slate and others [

1]; quartz–resin composites, also called engineered or agglomerated stone [

2,

3]; ceramics, porcelain tile and porcelain stone [

4,

5]; hard surface composites based on aluminum trihydroxide [

6,

7]; concrete and wood. These materials must meet several performance requirements, the most important of which are resistance to heat, stains, scratches and chips as well as ease of maintenance. All these requirements, combined with high durability and high aesthetic standards, are met in the most demanding applications—which, in addition to countertops, include suspended coverings, interior and exterior coverings, as well as various furniture elements—by means of rigid materials such as granite, engineered stone or porcelain stoneware [

8].

The significant growth of the ceramic industry has led to a huge consumption of clay raw materials, which results in their overuse and harm to the environment. For example, the production of ceramic tiles requires a significant amount of fluxes, which is about 50–60% by weight. Therefore, it is important to recycle and reuse industrial by-products such as fly ash and silica fume (microsilica), which have a good ratio of alumina to silica, making them suitable as raw materials for ceramic production. Therefore, the ceramic industry has a good opportunity to use industrial secondary raw material as an alternative raw material in a sustainable manner.

The production of porcelain stoneware consists of the following stages, usually using tunnel roller kilns, which have a pre-kiln zone, or drying, a heating zone, or preliminary heating, firing zones, rapid cooling, slow cooling and final cooling. In some cases, during the firing and production of porcelain stoneware, a defect called a crater is formed.

When raw materials are sintered in a furnace with the participation of a liquid phase, the carbonaceous material acts as a reducing agent at high temperatures. At a firing temperature of materials starting from 700 °C, the formation of new crystalline phases consisting of SiO2, silicates and complex aluminosilicates is observed. With an increase in temperature to 800–950 °C, the decomposition of carbonates and dolomite occurs with the release of carbon dioxide and thermal decomposition of sulfates and fluorides. Upon reaching a temperature of 1150–1200 °C, a liquid phase is formed due to the presence of feldspars containing a large amount of alkali metals. Feldspars are fluxes, and the resulting liquid phase fills the pores, increasingly dissolving the oxides of clay minerals, leading to noticeable shrinkage and compaction of the mass.

In the earth’s crust, the most common rock-forming silicate minerals are feldspars and kaolin—clay consisting mainly of the mineral kaolinite—Al4[Si4O10](OH)8. Among the most common minerals in nature is quartz, which is a rock-forming mineral of most igneous rocks.

There is natural mullite, i.e., a mineral from the class of silicates in the form of mAl

2O

3·SiO

2. Mullite is formed by heating kaolinite to 950 °C [

9]. Mullite is the main component of synthetic porcelain stoneware. The iron content in the mineral—iron oxide of various modifications with other metal oxides—gives the porcelain stoneware a shade from pink to brown.

As a result of high-temperature firing, part of the quartz remains unchanged, and metakaolinite, formed during the dehydration of kaolinite, is transformed into mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2). At the same time, part of the quartz is preserved in the structure of the final product.

Kaolinite, as the main component of the raw mix, undergoes dehydration and subsequent condensation, forming mullite. The resulting mullite is the main component of porcelain stoneware. With an increase in temperature to 1200 °C, other chemical transformations occur, leading to the formation of new crystalline phases and determining the final composition of the ceramic product.

Due to the lack of aluminum oxide in the composition of the original material, unbound SiO

2 (amorphous) is formed during the heat treatment. For greater mullite formation, an additional amount of Al

2O

3 is added to the mixture. When fired in the temperature range of 25–1200 °C, reactions including the formation of 3Al

2O

3·2SiO

2 and other compounds occur. This reaction leads to the formation of mullite, which is a highly durable and hard mineral. Mullite gives porcelain stoneware its characteristic properties, such as increased strength, hardness, heat resistance and abrasion resistance [

10].

Thus, from the above-mentioned known methods, natural minerals are mainly used, which contain carbon-containing minerals including dolomite and quartz–resin composites. During the firing process, a defect is formed, the so-called black chips (cracks) or craters of which reduces the strength of porcelain stoneware and frost resistance. Such characteristics significantly affect the quality of porcelain stoneware. To eliminate such defects and improve the quality of porcelain stoneware, we offer the use of waste silicon production containing active silicon oxide, which leads to the formation of a durable solid-phase mineral mullite due to aluminum oxide and microsilicon-silicon oxide, allows the removal of carbon dioxide and eliminates the formation of defects, cracks and chips in porcelain stoneware.

At present, the production of porcelain stoneware using the active component of microsilica secondary raw material from silicon production and its effect on the physical and mechanical properties of porcelain stoneware have not been studied. Optimization of the process of obtaining porcelain stoneware from a mixture of raw materials using microsilica as a silicon-containing component allows us to determine the phase composition and microstructure of the material, increasing its strength and hardness. The results of the study demonstrate the innovativeness of the technology in comparison with the known method, as well as the prospects and scientific interest of using micro-silica in the production of high-quality porcelain stoneware [

11]. Microsilica content in individual compositions may be low (up to 4%), but its cumulative use in industrial-scale production leads to significant environmental benefits due to waste recycling and reduced emissions. Additionally, the study quantified carbon emission reductions (8–12%) and recycling of up to 150 kg of microsilica waste per ton of product, supporting the sustainability claims. Despite the known use of microsilica in various ceramics, its systematic use in porcelain stoneware for improving mechanical properties while ensuring environmental sustainability remains insufficiently studied. Herein lies the novelty and research gap addressed in this study, which confirms the role of microsilica in enhancing the sintering and mechanical properties of ceramics while supporting sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

For this paper, the powder mixtures were wet homogenized in a laboratory mill for 30 min to achieve a uniform particle distribution. The resulting suspension was dried in an oven at 90 °C for 2 h and then compacted into rectangular molds under a pressure of 5 MPa. The molded ceramic bodies measuring 8.5 × 4.2 × 1.6 cm were further dried in an oven at 110 °C for 48 h.

The dried ceramic samples were sintered at 1100, 1150 and 1200 °C with a temperature rise of 6 °C/min for 45 min in a Carbolite tube furnace (MF03-3.13). The sintered samples were then cooled naturally to room temperature before evaluating their physical and mechanical properties.

The physical properties of the ceramic sample—including the water absorption, apparent porosity and bulk density of the samples—were determined using standard methods according to ASTM-373-88 [

12]. The samples were boiled in distilled water for 5 h.

The mechanical properties of the specimen were studied, and bending and compression tests were conducted according to ASTM-C67 [

13] guidelines. The flexural strength results were determined using the three-point testing method. The load was applied uniaxially to the specimens until failure. The loading rate in the dynamic bending test varied from 0.001 MPa/s to 1 MPa/s (Hettich et al., 2017) [

14] using a universal strength tester. The flexural strength gauge readings were recorded in MPa.

In the process of porcelain stoneware production, the components mixed according to the recipe are pressed in hydraulic presses under high pressure, which is followed by firing in roller kilns. The firing stage is the final one in the technological cycle of porcelain stoneware production. Due to the higher degree of homogeneity in chemical and mineralogical composition (compared to natural granite) and a special firing technology, the obtained material has water absorption of less than 0.5% and a bending strength of at least 35 N/mm2. One of the fundamental operations in the technological process of granite production is firing. During firing, a ceramic material is obtained, and the raw materials included in the mass are transformed into new crystalline and amorphous phases, giving it the required properties: mechanical strength and hardness; low porosity and water absorption; chemical resistance. Firing consists of heating—transferring energy to the product in the furnace for some time with a certain intensity—so that controlled physical and chemical properties of the material can occur. The composition of the raw material mass was studied using a JSM-6490LV scanning electron microscope equipped with an INCA Energy-350 energy-dispersive microanalysis system and an HKL Basic polycrystalline sample structure and texture analysis system. Physicochemical analysis methods were also used to analyze the samples: X-ray phase analysis (XPA) on a DRON-3 device.

Phase Identification and Semi-Quantitative Analysis: Phase identification in X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was conducted using the ICDD PDF-2 (International Centre for Diffraction Data Powder Diffraction File) database for matching diffraction peaks with standard reference patterns. Semi-quantitative phase analysis was performed using the Reference Intensity Ratio (RIR) method, enabling the estimation of the relative weight fractions of crystalline phases based on the integrated intensities of the strongest diffraction peaks and their reference intensity ratios from the ICDD database. This approach was used to determine the relative contents of quartz, mullite, feldspars, and hematite.

The ceramic mass for the production of porcelain stoneware, containing a clay component, kaolin, feldspar and a silicon-containing component, contains kaolin and white-burning clays as the clay component and microsilica as the silicon-containing component in the following ratio: wt.%: kaolin clay 32–34, kaolin 24–26, feldspar 23–25, white-burning clay 5–17, microsilica 2–5.

Particular attention was paid to the influence of flux—feldspar and the microsilica secondary raw material of «Tau-ken temir» LLP—on sintering and phase formation as well as identifying the dependence of the course of reactions during firing on the fractional composition of the materials of porcelain stoneware masses. The chemical composition of the raw mixture for the synthesis of porcelain stoneware is given in

Table 1.

From the data in

Table 1, it is evident that the main substances of the components used are feldspar, clay, quartzite, opoka (gaize) and microsilica. The active silicon oxide contained in microsilica with aluminum oxide during firing forms the mineral mullite, which gives strength and improves the quality of porcelain stoneware.

All raw materials were separately ground in a laboratory ball mill using the dry method for 16 h, after which they were passed completely through one of the control sieves No. 0.224; 0.125; 0.08; 0.063; 0.04. To prepare the masses, the raw materials were dosed using technical scales T-200. Various compositions of ceramic masses were tested, including four samples consisting of feldspar, kaolin and clays using microsilica.

To determine the properties of the finished materials, samples measuring 60 × 30 × 5 mm were used. The samples were prepared by the semi-dry pressing of powders with a moisture content of 8–11%. To granulate the powder and distribute the moisture more evenly, the press powder was rubbed through a No. 1.0 sieve. The press powder was aged for 24 h in a desiccator. The test samples were molded by semi-dry pressing on a laboratory hydraulic press with a pressing pressure of 400 MPa. Then, the molded samples were dried in a drying cabinet at a temperature of 110 °C. The samples were fired in a high-temperature electric furnace LHT 02/16 at a temperature of 1100–1300 °C.

The microsilica used in this study was pre-ground in a laboratory ball mill for 16 h using a dry milling method. The ground material was sieved through control sieves with mesh sizes of 0.224 mm, 0.125 mm, 0.08 mm, 0.063 mm, and 0.04 mm, ensuring a fine and homogeneous particle size distribution in the prepared slip. This fine distribution facilitates the effective participation of microsilica in the sintering and mullite formation processes within the ceramic matrix.

Analytical Methodology for Reactive SiO2 Determination: The reactive SiO2 content in microsilica was assessed using a scanning electron microscope (JSM-6490LV) equipped with an INCA Energy-350 energy-dispersive microanalysis system as well as X-ray phase analysis (XPA) using a DRON-3 diffractometer. The elemental composition analysis confirmed that the microsilica contained 38.09% silicon (Table 8), indicating a high content of reactive SiO2 capable of participating in mullite formation during firing.

These detailed data clarify the particle size characteristics and reactivity of microsilica used in this study and support the observed improvements in physical and mechanical properties of the porcelain stoneware, including increased flexural strength, reduced water absorption, and enhanced frost resistance.

3. Results and Discussion

Several raw material compositions of the ceramic granite mass were prepared for the study. The ceramic mass for the production of porcelain stoneware, containing a clay component, kaolin, feldspar and a silicon-containing component, contains kaolin and white-burning clay as a clay component as well as microsilica as a silicon-containing component.

Table 2 shows the results of the physical and mechanical tests of the obtained tiles.

The high physical and mechanical properties of the laboratory tile samples are due to the achievement of optimal indicators of the chemical and mineralogical composition and structure of the synthesized mass compositions (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5).

Thus, the study of the physical and mechanical properties and X-ray phase composition of the obtained samples made it possible to determine the formation and content of complex minerals and the main mineral mullite. The formation of a large amount of mullite leads to an increase in the main property, i.e., the strength of porcelain stoneware. A low content of the mullite mineral or its absence significantly reduces the physical and mechanical properties of porcelain stoneware. For in-depth analysis, it is necessary to study the effect of the content of microsilica (additive SiO

2 active up to 4%) on the formation of mullite 3Al

2O

3 × 2SiO

2 and on the strength of porcelain stoneware [

16,

17].

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the contents of the above-mentioned minerals and the contents of the elements.

The chemical compositions of the synthesized porcelain stoneware samples, according to spectroscopy data, are presented in

Table 5.

Based on the data presented in

Table 5, calculations were made of the molecular formulas of the porcelain stoneware samples, acidity coefficients and thermal coefficients of thermal expansion (TCTEs) (

Table 6).

The molecular formulas, acidity coefficients and TCTEs of the synthesized porcelain stoneware samples correspond to fine ceramic masses.

To study the effect of microsilica content on the production of porcelain stoneware, the raw material composition of the porcelain stoneware mass was prepared and presented in

Table 7.

From the data in

Table 7, it can be observed that the main components of the raw mixes are feldspar, kaolin, and clay with microsilica ranging from 1 to 4%. This variation aims to assess its effect on the bending strength of the final porcelain stoneware.

In order to optimize the composition of the porcelain stoneware mass using microsilica, the effect of different ratios of the components of the raw mix on the properties of the obtained samples was studied. We preliminarily studied the elemental composition (

Table 8) and the structure of microsilica (

Figure 6).

From the data in

Table 8 and

Figure 6, it is clear that microsilica contains mainly silicon, aluminum, sodium, calcium and iron.

The firing process of the porcelain stoneware mass is carried out with an increase in temperature to 1200 °C for 60–90 min. The following reactions occur:

These equations describe the thermal decomposition and reaction pathways during firing, illustrating the formation of mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2) as a primary phase, the evolution of low-melting silicates, and the transformation of clay and feldspar components, which are critical for controlling the microstructure and mechanical properties of the porcelain stoneware. In the temperature range of 25–300 °C, reactions 2, 3, and 5 occur with the formation of 3Al2O3 × 2SiO2, K2SiO3, Na2SiO3, and SiO2. Moreover, in all reactions, the primary mullite mineral is formed—3Al2O3 × 2SiO2. Reaction 6 possibly occurs by the interaction of the mineral Al2O3 × 2SiO2 formed in the first reaction (1) with alumina (Al2O3) contained in the microsilica in the composition with the formation of secondary mullite—3Al2O3 × 2SiO2. A further increase in temperature to 1200 °C possibly leads to the melting of low-melting minerals. Thus, during firing, reaction (1)–(6) can occur with the formation of primary and secondary mullite-3Al2O3 × 2SiO2 as well as low-melting silicates Na2SiO3, K2SiO3 and SiO2.

To produce porcelain stoneware by pressing from semi-dry powders, the slip technology of mass preparation was used. Pre-dried components were selected in percentage ratio and ground in a laboratory ball mill. The resulting mass-slip consisted of particles of a fairly small and homogeneous fraction. The finished slip was dried and ground to a powder state, and water was added to it (5–6% of the weight of the ground powder for subsequent molding). Then, the samples were dried in a drying cabinet at a temperature of 110 °C and fired in a high-temperature electric furnace LHT 02/16 at a temperature of 1100–1300 °C [

18,

19].

Optimization of the process parameters for obtaining porcelain stoneware in various mixture compositions was carried out using the Statistika-10 programs, and graphs of the dependence of the porcelain stoneware yield on the firing temperature were constructed.

Figure 7a,b show three-dimensional images of the surface of the function of the degree of porcelain stoneware yield on the firing temperature and time from the change in the mass of microsilica. The temperature and time of visual determination of the parameters at which different values of the mass yield are achieved are shown in different colors. The reactivity of SiO

2 was further confirmed by X-ray diffraction (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8), demonstrating the formation of mullite (3Al

2O

3·2SiO

2) and residual quartz (SiO

2) after firing. Microstructural analysis (

Figure 9) indicated the presence of finely distributed mullite crystals within the glassy matrix of the ceramic, showing the effective utilization of reactive silica from microsilica in enhancing the microstructure and densification of the porcelain stoneware.

From

Figure 7a, it can be seen that the three-dimensional surface of the graph (indicated by the red stripe) contains the highest degrees of mass yield of porcelain stoneware: more than 91.0%. The highest degree of mass yield is observed at a temperature of 1240 °C (a) and a process duration of 60 min, where the degree of conversion reaches 91.0%.

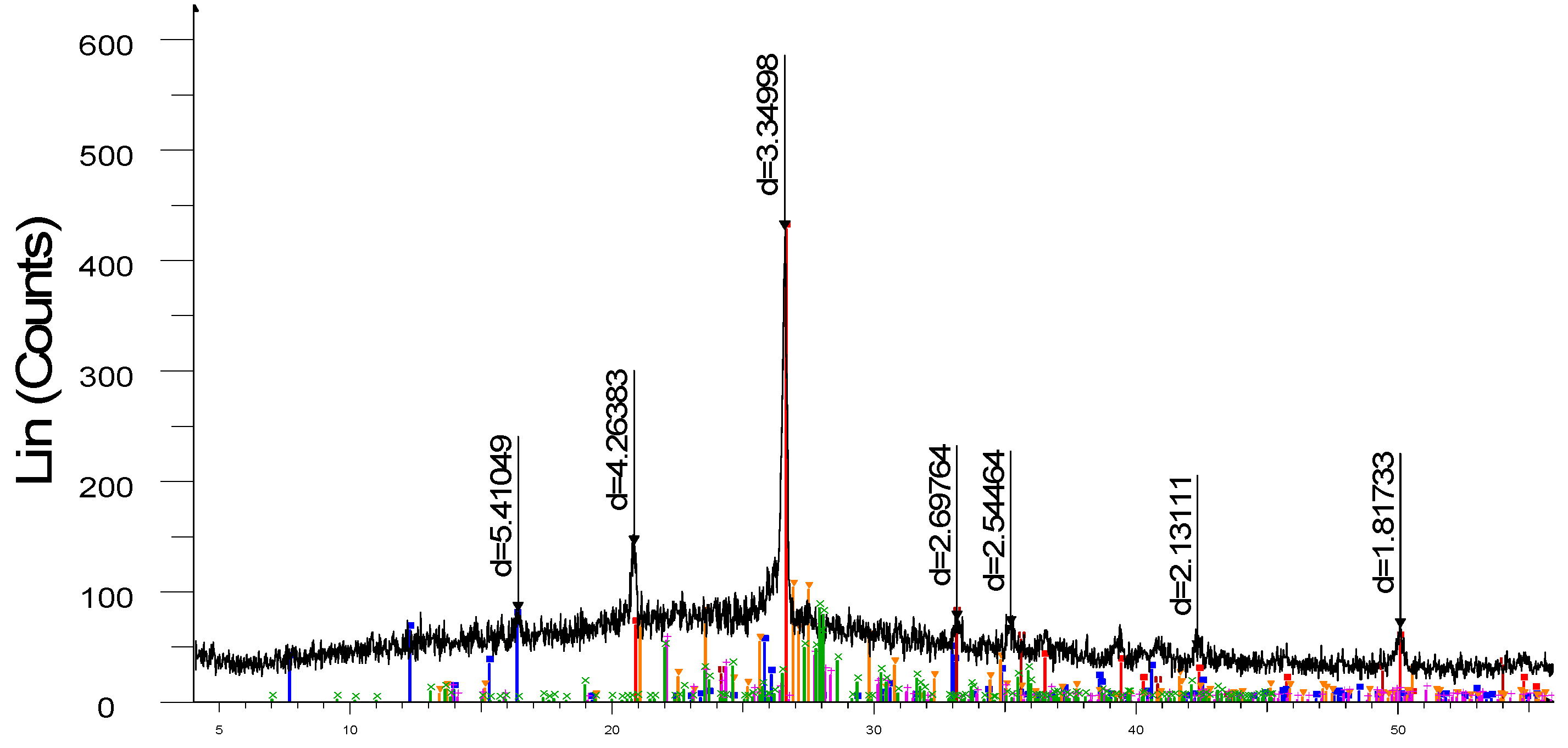

X-ray phase analysis of the finished samples, carried out on the X-ray diffractometer DRON-3, are shown in

Figure 7. The study of the obtained sample by the X-ray phase analysis method shows that in the X-ray diffraction pattern (

Figure 3) of the synthesized porcelain stoneware, the intensity (d/n = 5.41049, 3.34996 A°) corresponds to mullite (3Al

2O

3·2SiO

2) and the intensity (d/n = 4.26383; 3.34998; 2.13111; 1.81733 A°) corresponds to quartz (SiO

2).

As a result of the studies of physical and chemical processes accompanied by the formation of new mineral and liquid phases, the possibility of using microsilica as a silicon-containing raw material was found. The samples (

Figure 8) have a fairly dense structure.

As seen in

Figure 9, the microstructural analysis of the porcelain stoneware shows the presence of clearly distinguishable feldspar relics consisting of glass phase and mullite. Sample (a) has a more porous structure, while sample (b) has a denser structure due to the content of more mullite crystals and glass phase. Quartz grains are surrounded by rims of high-silica glass and pores of various shapes and sizes. Mullite areas corresponding to the original feldspar particles and incompletely decomposed arrays of clay substances are clearly identified [

20,

21].

The developed composition of the porcelain stoneware mass, obtained by analyzing the melting curves on the state diagrams, and then studying the physicochemical and structural transformations in multicomponent systems during firing and according to the results of technological experiments, is given in

Table 9.

From the data in

Table 9, it follows that out of the samples obtained from different compositions of porcelain stoneware masses, sample M-1 has high indicators. The experimental data indicate that the addition of microsilica allows to increase the strength of porcelain stoneware in bending up to 41.5 MPa (above the standard), reduce water absorption to 0.023% and increase frost resistance to 107 cycles as well as increase the shrinkage of porcelain stoneware to 11.12%. The flexural strength results are presented in

Table 9, showing values ranging from 40.4 MPa to 41.5 MPa, with the highest value corresponding to samples containing 2 wt.% microsilica.

The use of microsilica as a silica component in the porcelain tile batch mixture gave a beneficial effect, increasing the physical and mechanical properties of the synthesized material.

The study demonstrates that microsilica, as a secondary raw material, constitutes 10–15% of the total batch composition in the production of porcelain stoneware, resulting in the utilization of up to 150 kg of microsilica waste per ton of finished product. This contributes to solid waste recycling and aligns with circular economy principles.

Furthermore, considering that the production of microsilica as a by-product avoids additional emissions associated with primary silica production, and that optimized firing temperatures and reduced firing times were achieved through microsilica addition, it is estimated that carbon emissions are reduced by approximately 8–12% per ton of product compared to conventional porcelain stoneware production. This is attributed to the enhanced sintering behavior, which allows lower energy consumption during firing.

These quantitative assessments substantiate the environmental sustainability claims of this study, demonstrating that the proposed method contributes to resource conservation, waste reduction, and lower carbon emissions in the porcelain stoneware industry.

Based on the obtained test data, the M-1 composition was selected as the optimal mass composition. It was found that adding microsilica as a silica component to the porcelain stoneware batch leads to a significant increase in the physical and mechanical properties of the final product. The formation of a finely dispersed microsilica structure helps improve the cohesion of the ceramic mass, which has a positive effect on the strength and durability of porcelain stoneware. The proposed approach opens up new possibilities for creating high-quality building materials based on industrial secondary raw material. Microstructure analysis showed the presence of clearly distinguishable feldspar relics consisting of glass phase and mullite. Quartz grains are surrounded by rims of high-silica glass and pores of various shapes and sizes. Microphotographs of the chip show a structural glassy matrix permeated with uniformly distributed submicroscopic mullite crystals. Mullite regions corresponding to the original feldspar particles and incompletely decomposed clay massifs are clearly identified.

In this paper, the effect of microsilica additives on the phase composition and properties of porcelain stoneware was investigated. Microsilica, being an active siliceous additive, is introduced into the batch to improve the physical and mechanical properties of the final product.

In addition to facilitating mullite formation, the fine particle size and high reactivity of microsilica enhance the sinterability of the ceramic mass, contributing to increased densification during firing. Microsilica, with its high surface area and amorphous structure, lowers the activation energy required for viscous flow and promotes the formation of a liquid phase at lower temperatures, which facilitates particle rearrangement and pore elimination, resulting in a denser microstructure [

22,

23].

Furthermore, the incorporation of microsilica may alter the stoichiometric ratio of alumina to silica in the system, affecting the type and amount of mullite formed. While stoichiometric mullite (3Al2O3·2SiO2) has a specific Al2O3:SiO2 ratio, variations in local stoichiometry can lead to the formation of silica-rich or alumina-rich mullite. This difference can influence microstructural evolution and sintering behavior. Our results demonstrated that silica-rich compositions enhance viscous flow sintering, facilitating densification while maintaining mullite formation, which aligns with our observations of increased densification alongside enhanced mullite formation in our samples containing microsilica.

Thus, the improved physical and mechanical properties observed in our study are attributed not only to the formation of mullite but also to enhanced densification due to the sintering behavior of microsilica and stoichiometric variations that promote densification mechanisms in the system.

Ceramic masses of various compositions were developed by varying the microsilica content at a fixed ratio of kaolin, feldspar and white-burning clay. The samples were fired at a temperature of 1200–1300 °C. The phase composition and microstructure of the obtained materials were studied using X-ray diffractometry and scanning electron microscopy [

22,

23].