Abstract

Transparent CAD/CAM monolithic ceramics are increasingly used in dentistry due to their combination of high strength, esthetics, and durability, achieved through high yttria content and multilayered systems. This study evaluates the mechanical behavior of four widely used CAD/CAM ceramics, correlating their performance with microstructural characteristics. Bar-shaped specimens (n = 10 per material, for each test) of ZOLID® FX ML (ZF), IPS E.MAX® CAD (MC), E.MAX® ZIRCAD (ZM), and KAT-ANA® STML (KS) (all A2 shade) were prepared and sintered according to manufacturers’ protocols. Flexural strength and elastic modulus were measured using three-point bending, and Vickers hardness was determined separately. Statistical normality was confirmed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Flexural strength ranged from 252.8 ± 39.8 MPa (MC) to 547.6 ± 125.7 MPa (ZM), elastic modulus from 65.8 ± 6.5 GPa (MC) to 94.1 ± 5.8 GPa (KS), and hardness from 4.2 ± 0.2 GPa (MC) to 9.6 ± 0.6 GPa (ZF). High-elastic-modulus materials (KS, ZM) can better resist deformation under occlusal loads, improving long-term stability of posterior crowns, bridges, and implant-supported restorations. High hardness (ZF) provides superior wear resistance and preserves occlusal anatomy over time, making it suitable for thin-shell restorations and high-stress functional surfaces. Materials with lower modulus and hardness (MC) are more suitable for intra-coronal restorations or thin veneers where stress shielding and material compliance are advantageous. These findings support material selection based on mechanical demands, and further clinical studies are needed to confirm long-term performance.

1. Introduction

Monolithic Zirconia ceramics represent a significant evolution in dental materials, offering a solution to the clinical limitations associated with veneered Zirconia restorations. For decades, bi-layered Zirconia restorations were favored for their esthetics; however, frequent chipping and delamination of the veneering layer have compromised their long-term success and patient satisfaction. Furthermore, the need for extensive tooth reduction to accommodate the veneering porcelain posed an additional clinical drawback [1]. To address these issues, monolithic Zirconia was introduced as a single-phase alternative that eliminates the weaker veneer while delivering superior fracture strength and wear resistance [2].

Despite the enhanced mechanical reliability of monolithic Zirconia, early formulations suffered from high opacity, limiting their esthetic application in anterior regions. Recent material innovations have focused on increasing translucency through the incorporation of higher yttria content (4–8 mol%), promoting the formation of cubic Zirconia grains [3]. These cubic phases enhance light transmission due to their isotropic refractive properties, resulting in highly translucent Zirconia systems that visually approximate lithium disilicate glass-ceramics [4,5,6,7,8].

However, while esthetics have improved, the shift in microstructure may reduce mechanical strength and aging resistance, raising concerns regarding their long-term performance [9,10]. So current research suggests that high-translucency monolithic Zirconias should be used strategically according to clinical demands—e.g., high-strength variants for posterior use, and ultra-translucent grades for anterior restorations [11,12]. Many systems boast flexural strengths exceeding 1000 MPa, supporting more conservative tooth preparations without sacrificing structural integrity [12]. Nonetheless, the rapid proliferation of these materials on the market has outpaced independent scientific validation. Not all commercially available products have been assessed under standardized conditions, particularly ISO 6872:2015(E) protocols [13], making comparisons difficult and impeding the development of evidence-based guidelines.

Short-term clinical outcomes are encouraging, with reported survival rates of 97.6% (95% CI: 94.3–99.0) for implant-supported monolithic Zirconia crowns over three years [14], and 91–100% for multi-unit restorations in shorter studies [15]. However, these data are limited by heterogeneity and follow-up duration, emphasizing the need for continued laboratory and clinical validation [11,16].

Building upon prior reports that have characterized the optical behavior of multilayered transparent ceramics, this study provides second part where a detailed mechanical performance assessment of these materials is reported, particularly focusing on emerging high-yttria-content Zirconia systems. The findings are relevant not only for dental applications but also for the broader field of transparent ceramic optimization, where mechanical integrity under function is equally critical to optical clarity. Specifically, we compare three CAD-CAM-fabricated, multilayered Zirconia ceramics to a lithium disilicate control, evaluating their flexural strength, elastic modulus, and hardness under ISO 6872:2015(E) protocols.

The null hypothesis tested is that no significant mechanical differences exist among the tested ceramics. The findings contribute to the growing body of data needed to support evidence-based material selection and underscore the importance of transparency and rigor in evaluating next-generation ceramic systems for restorative dentistry, and beyond.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Selection

Four types of monolithic esthetic CAD-CAM ceramic materials in A2 shade were examined. Among them, three were highly translucent, multilayered Zirconia disks:

The zirconia and glass-ceramic materials evaluated in this study included ZOLID® FX Multilayer (ZF; Amann Girrbach AG, Koblach, Austria), IPS E.MAX® ZirCAD MT Multi (ZM; Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein), KATANA® STML (KS; Kuraray Noritake Dental Inc., Tokyo, Japan), and IPS E.MAX® CAD LT (MC; Ivoclar Vivadent AG, Schaan, Liechtenstein). ZOLID® FX Multilayer (ZF) consists of ZrO2 + HfO2 + Y2O3 ≥ 99% with Y2O3 content of 8.5–9.5%, representing a high-translucent, cubic phase–stabilized zirconia. IPS E.MAX® ZirCAD MT Multi (ZM) contains ZrO2 86–93.5% and Y2O3 6.5–8.0%, characterized as a medium-translucency zirconia with a tetragonal–cubic mixed phase. KATANA® STML (KS) comprises ZrO2 + HfO2 88–93% and Y2O3 7–10%, classified as a high-translucent, multi-layered zirconia. The glass-based ceramic material, IPS E.MAX® CAD LT (MC), is composed of SiO2 58–80% and Li2O 11–19%, representing a lithium disilicate glass-ceramic.

All materials were obtained from identical batch numbers as per the manufacturers’ guidelines.

The sample size was determined using GPower statistical software (GPower Ver. 3.0.10, Franz Faul, Universität Kiel, Kiel, Germany) with parameters set at a power of 0.75, an α value of 0.23, and an effect size of 0.38 (in-house calculation). ISO 6872:2015(E): recommends 10–30 samples. A total of 80 samples were prepared, allocating 20 specimens per material—10 for evaluating flexural strength and elastic modulus, and 10 for hardness testing.

2.2. Sample Preparations

Milling was conducted in the green state to compensate for shrinkage during sintering, utilizing a CAD-CAM system (K5+, vhf camfacture AG, Ammerbuch, Germany). Polishing was performed with a grinding device (echo LAB POLI-1X/250, Devco S.r.l., Como, Italy) operating at 300 rpm, using silicon carbide papers of 600, 800, and 1000 grit. Water was applied during the polishing of lithium disilicate samples, whereas Zirconia was polished dry, following manufacturer recommendations.

For Zirconia-based materials, polishing was performed in the pre-sintered state rather than after sintering. Although the manufacturer’s recommendation is to polish Zirconia after final sintering (which is the clinical case where samples are altered to fit occlusion), this adjustment was made for research purposes and to standardize sample preparation across groups. Polishing in the pre-sintered stage was chosen because the material is softer and easier to finish, and because post-sintering polishing can induce surface alterations that may mask intrinsic differences in microstructure and mechanical performance. No further polishing was performed after sintering to avoid introducing such alterations. In contrast, lithium disilicate CAD/CAM blocks were polished under wet conditions to reduce the risk of surface microcracking and because the material is temperature-sensitive during adjustment. These standardized yet material-appropriate protocols ensured that each ceramic was finished in a way that reflected its clinically relevant processing pathway while minimizing variability from post-sintering surface alterations.

Bar-shaped specimens were used for flexural strength testing in accordance with ISO 6872:2015, which standardizes geometry to ensure reproducibility and accurate stress distribution. While they do not perfectly mimic the complex shapes of clinical restorations, bar specimens provide a baseline for material comparison and allow for a direct comparison with the existing literature. Final dimensions were verified with a digital caliper (Insize 1111-75A, Insize Co., Ltd., São Paulo, Brazil), maintaining a precision of ±0.01 mm.

Sintering and crystallization adhered to material-specific protocols (Table 1).

Table 1.

The workflow for the study.

2.3. Flexural Strength and Elastic Modulus Testing

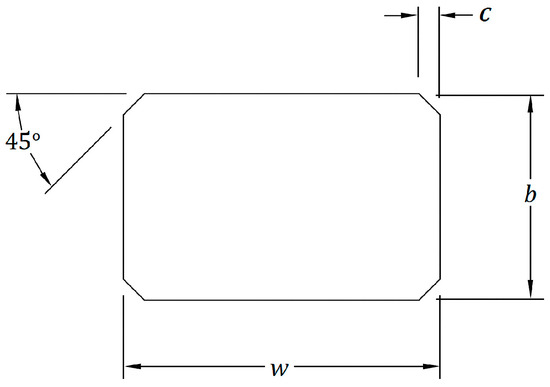

In accordance with ISO 6872:2015(E) standards, bar-shaped specimens were fabricated with final dimensions of 18 × 4 × 3 mm3 and edge chamfered at a 45° angle (Figure 1). This chamfer reduces stress concentrations at the corners, preventing premature fractures during testing. Prior to testing, samples were stored in distilled water at 37 °C for 24 h.

Figure 1.

The chamfer edge for bar shaped of the flexural strength samples. Width w = 4.0 mm ± 0.2 mm (dimension of the side at right angles to the direction of the applied load), Thickness b = 3.0 mm ± 0.2 mm (with 3.0 mm recommended; dimension of the side parallel to the direction of the applied load), Chamfer c = 0.15 mm.

The flexural strength was determined using a three-point bending test (3-PBT) on a universal testing machine (Computer-controlled electromechanical universal testing machine (Jinan Testing Equipment Co., Ltd., Jinan, China) with a 16 mm span and a crosshead speed of 1.0 mm·min−1.

Flexural strength (σ) in MPa was calculated using Equation (1) ISO 6872:2015(E) [13]:

where; P is the breaking load, in newtons; l is the test span (Centre-to-centre distance between support rollers), in millimeters; w is the width of the specimen, i.e., the dimension of the side at right angles to the direction of the applied load, in millimeters; b is the thickness of the specimen, i.e., the dimension of the side parallel to the direction of the applied load, in millimeters.

σ = 3Pl/2wb2

The elastic modulus (Em) in GPa was obtained using 3-PBT and Equations (2) and (3) [17]:

where l is the span length (16 mm), b is the sample width w (millimeters), h is the sample thickness (millimeters), S is the stiffness (Newton/meter), and it was calculated from the Formula

where d is the deflection corresponding to load f at a point in the straight-line portion of the trace.

Em = Sl3 × 4bh−3

S = f/d

2.4. Vickers Microhardness Testing

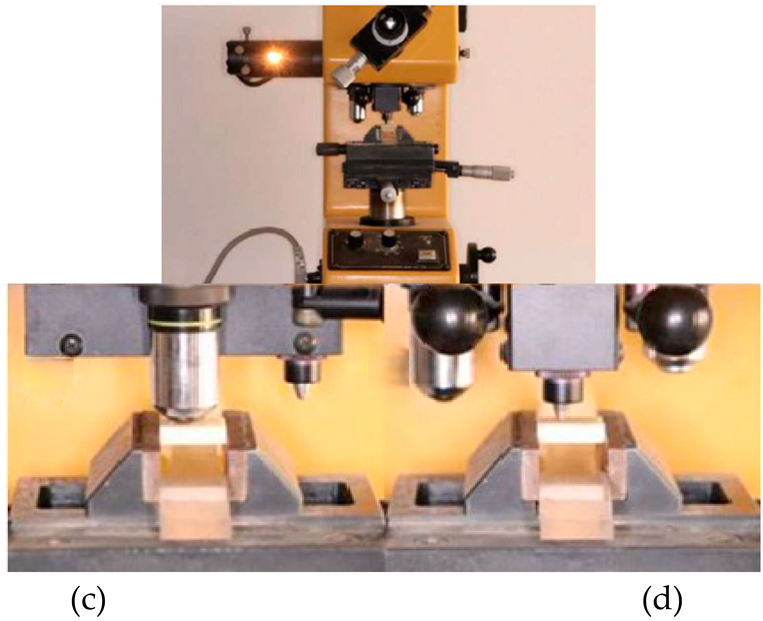

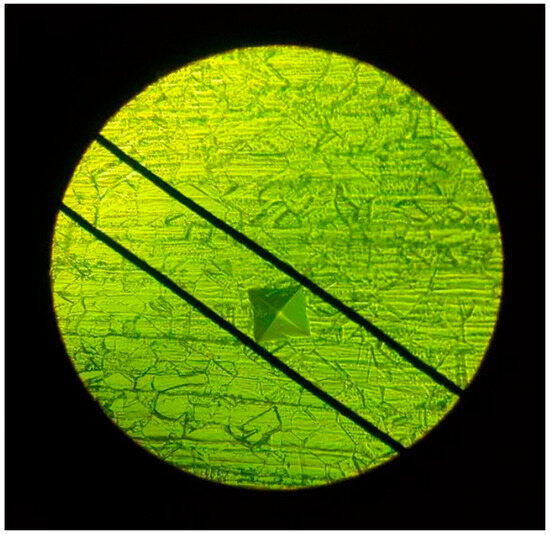

Rectangular specimens measuring 18 × 14 × 5 mm3 were prepared, polished, and sintered as previously described. After 24 h storage in distilled water at 37 °C, the microhardness of the samples was evaluated using a Vickers hardness tester (Matsuzawa Seiki Co., Ltd., Akita, Japan) following ASTM C1327 guidelines [18]. A load of 300 g was applied for 10 s. Each specimen underwent five indentations, with a minimum spacing of 0.5 mm between them. The indentation diagonals (d1 and d2) were measured using an optical microscope (Figure 2), and hardness was calculated as follows: in Equation (4); ASTM C1327.

where N represents the applied load (N), and d1 and d2 denote the diagonals of the indentation (mm).

HV = 0.0018544 × N × (d1 × d2)−1

Figure 2.

Tested and Measurement of indentation size under microscope using green filter.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics v25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated for each mechanical property. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was applied to assess data normality. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze flexural strength, elastic modulus, and Vickers hardness, with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons. However, flexural strength was specifically analyzed using the Games-Howell test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Flexural Strength

Flexural strength values ranged from 252.8 to 547.6 MPa (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mean (±standard deviation) values and statistical analysis of flexural strength, elastic modulus and hardness of tested materials.

Statistical analysis indicated a significant variation among the tested groups (p < 0.05), with adjustments applied for multiple comparisons. The ZM group (547.6 ± 125.7 MPa) exhibited significantly greater flexural strength (p < 0.05) compared to ZF (462.4 ± 22.7 MPa) and KS (431.8 ± 60.4 MPa). Both ZF and KS also demonstrated significantly higher values (p < 0.05) than MC (252.7 ± 39.7 MPa). However, no significant difference was observed between ZF and KS (p = 0.472).

3.2. Elastic Modulus

Elastic modulus values ranged from 65.7 to 94.1 GPa (Table 1). The KS (94.1 ± 5.8 GPa) and ZM (93.9 ± 5.08 GPa) groups exhibited significantly higher elastic modulus values (p < 0.05) compared to ZF (83.9 ± 6.4 GPa), which in turn had significantly greater values (p < 0.05) than MC (65.7 ± 6.4 GPa). No significant difference was found between KS and ZM (p = 1.000).

3.3. Vickers Microhardness

Vickers microhardness values ranged from 4.1 to 9.6 GPa (Table 1). A significant difference was observed across the groups (p < 0.05), with multiple comparison adjustments confirming these distinctions. ZF (9.6 ± 0.6 GPa) and KS (9.6 ± 0.3 GPa) exhibited significantly higher hardness values (p < 0.05) compared to ZM (8.4 ± 0.5 GPa), and both were also significantly harder (p < 0.05) than MC (4.1 ± 0.2 GPa). However, no significant difference was detected between ZF and KS (p = 1.000). Among all tested materials, MC displayed the lowest hardness value, which was statistically significant (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Flexural Strength

Flexural strength is a crucial parameter for assessing the mechanical behavior of brittle materials, which are inherently weaker in tension than in compression [19]. The results revealed substantial differences among the materials, with E.MAX® ZIRCAD exhibiting the highest flexural strength, significantly outperforming ZOLID® FX and KATANA® STML. All Zirconia-based materials demonstrated significantly greater flexural strength than E.MAX® CAD.

Although the measured flexural strength values were generally lower than the manufacturers’ reported values (e.g., E.MAX® ZIRCAD: 850 MPa, ZOLID® FX: 700 ± 150 MPa, KATANA® STML: 748 MPa, and E.MAX® CAD: 360 MPa), they remain within clinically acceptable thresholds as recommended by ISO 6872:2015(E) standards. This is particularly relevant for clinicians when selecting materials for restorations subjected to high occlusal forces, such as posterior crowns. The absence of significant differences between ZOLID® FX and KATANA® STML suggests that these materials may be used interchangeably in clinical applications where a slight reduction in strength is acceptable, potentially allowing for greater flexibility in material selection based on esthetic and functional considerations.

Comparing these findings with previous literature, E.MAX® CAD flexural strength values in this study (210.2–471.2 MPa) align with the range reported in systematic reviews compiling data from three-point bending tests [20,21]. However, other studies have reported higher flexural strength values for ZOLID® FX (e.g., 557 ± 88 MPa, 657.35 ± 112.02 MPa, 676 ± 49.7 MPa), as well as a lower value of 433.54 ± 101.56 MPa, which is closer to the findings of the current study [22,23]. Similarly, KATANA® STML flexural strength has been reported with wide variation, ranging from 347.22 ± 32.73 MPa to 762.16 ± 200.96 MPa, with differences attributed to testing methodology, sample geometry, and preparation protocols [24,25,26].

The flexural strength values obtained in this study (547.5 MPa) for ZirCAD ceramic materials are considerably lower than those reported in another study (1462 ± 105 MPa) [27], but within the range reported before thermal aging [28,29]. The observed discrepancy could be attributed to several factors, including differences in composition, sintering conditions, and testing methodologies [30,31].

Another important consideration is the influence of multilayered Zirconia structures and their gradient properties. Studies have demonstrated that the flexural strength of Zirconia varies across layers due to compositional gradients, where the transition from tetragonal-rich to cubic-rich phases impacts the mechanical behavior [32,33]. The presence of weaker layers, particularly those with higher cubic-phase content, may have contributed to the lower strength values observed in this study. While the current results suggest a lower flexural strength for the evaluated ZirCAD material, further investigations incorporating microstructural analysis and controlled sintering parameters are needed to better understand the factors influencing its mechanical performance.

4.2. Elastic Modulus

The elastic modulus values varied significantly among the tested materials. KATANA® STML and E.MAX® ZIRCAD exhibited significantly higher values compared to ZOLID® FX and E.MAX® CAD. The lack of significant differences between KATANA® STML and E.MAX® ZIRCAD suggests that these materials offer similar rigidity, which is crucial in clinical applications requiring dimensional stability under load.

The elastic modulus of Zirconia-based materials is influenced by Yttria (Y2O3) content, which determines the crystalline phase distribution. Higher Yttria content stabilizes the cubic phase, increasing translucency while reducing strength and stiffness. Among the tested materials, ZOLID® FX (8.5–9.5% Y2O3), E.MAX® ZIRCAD (6.5–8.0%), and KATANA® STML (7–10%) differ in their Yttria concentrations, which explains the observed mechanical variations. E.MAX® CAD, inherently has a lower modulus of elasticity due to its composition, resulting in greater flexibility compared to Zirconia materials. This property can enhance adaptation and longevity, particularly in patients with parafunctional habits such as bruxism.

These findings align with existing literature, where Zirconia-based materials consistently demonstrate higher elastic modulus values than lithium disilicate ceramics [7,34]. For instance, a study on cubic/tetragonal Zirconia materials also found high elastic modulus values, indicating the material’s suitability for restorations requiring high mechanical stability [22]. The difference between ZF and KS in our study is comparable to their findings on the mechanical properties of Zirconia, where variations in composition can lead to different performance characteristics. Moreover, studies suggest that materials with a lower modulus of elasticity tend to exhibit improved machinability and adaptability, which can be advantageous in CAD/CAM restorations [34,35,36].

4.3. Vickers Microhardness

Significant differences in Vickers microhardness were observed among the materials. ZOLID® FX and KATANA® STML exhibited the highest values, significantly surpassing E.MAX® ZIRCAD and E.MAX® CAD.

The hardness of Zirconia-based materials is influenced by Yttria content and phase transformation behavior. Higher Yttria levels stabilize the cubic phase, which enhances translucency but can lower hardness compared to materials with a higher tetragonal phase proportion, such as E.MAX® ZIRCAD. In contrast, the glass-ceramic E.MAX® CAD exhibits the least hardness due to its glass matrix, making it more susceptible to wear but potentially more enamel-friendly.

The hardness of ceramic materials, also, plays a crucial role in their finishability, and polishability [37,38]. The hardness value of E.MAX®CAD is slightly above that of human enamel (3.5 GPa) [39] Zirconia materials could be beneficial in protecting opposing tooth structures from excessive wear. However, further studies are necessary, as material hardness is not the sole factor in the complex wear process.

The hardness values reported in this study were generally lower than those found in previous investigations. For instance, Goujat et al. reported a Vickers hardness of 5.98 ± 0.94 GPa for E.MAX® CAD, while Elsaka et al. reported 11.36 ± 0.61 GPa for ZOLID® FX [23,40]. Discrepancies in hardness values across studies may result from variations in sample preparation, testing methods, indentation parameters, and environmental conditions.

Additionally, data provided by manufacturers and other studies for various Zirconia materials are often presented as dimensionless Vickers hardness numbers rather than in GPa. No data was available for E.MAX®ZIRCAD. The discrepancies in results may be attributed to variations in material sample preparation and other external factors, such as the measuring system, the shape of the indenter, and the applied load.

4.4. Clinical Implications and Recommendations

The microstructural origins of the mechanical properties directly inform evidence-based clinical material selection. The exceptional strength and stiffness of E.MAX® ZIRCAD make it the material of choice for the most demanding clinical situations, including long-span fixed dental prostheses (FDPs), molar crowns, and implant-supported restorations. Its microstructure is optimized to withstand high cyclic occlusal forces.

Aesthetic-Critical Single Units: ZOLID® FX and KATANA® STML are ideally suited for single-unit posterior crowns, inlays, and onlays where aesthetic appeal is paramount. Their strength, close to Class 1 ceramics, supports their recommendation for use as EndoCrowns and Posterior veneers (Thin crowns). Their graded structure allows technicians to mimic the natural dentin-enamel complex with a monolithic material. Furthermore, their superior hardness ensures excellent resistance to wear and the ability to maintain a polished surface over time, reducing plaque adhesion.

Anterior Restorations and Enamel-Friendly Applications: E.MAX® CAD remains a superb option for anterior crowns, veneers, and inlays. Its lower hardness is a significant clinical advantage, as it is less abrasive to opposing natural dentition. This is particularly important in patients with parafunctional habits or when restoring the antagonist to a natural tooth.

4.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite providing valuable insights into the mechanical performance of monolithic CAD/CAM ceramics, this study has several limitations. First, only bar-shaped specimens were tested for flexural strength, elastic modulus, and hardness. While standardized per ISO 6872:2015(E), these geometries do not fully replicate the complex shapes and stress distributions of clinical restorations, potentially limiting direct clinical extrapolation. Second, the study assessed only a few mechanical properties, omitting fracture toughness and fatigue resistance, which are critical for predicting long-term performance under cyclic intraoral forces.

Third, polishing and sintering protocols varied among materials (different temperatures and speeds), which may affect comparability. Fourth, only A2 shade materials were tested, limiting the generalizability of results, as shade-dependent translucency or microstructure variations can influence mechanical properties. Fifth, the study did not incorporate thermal cycling or cyclic loading, which simulate the oral environment and are known to impact material durability.

Additionally, the correlation between microstructural differences (grain size, crystalline phases, density) and mechanical behavior, although discussed, was not fully explored in relation to long-term performance. Related optical properties, such as translucency and color stability, were only considered in previous studies; including them here could provide a more comprehensive assessment, as microstructural features often influence both optical and mechanical behavior. Finally, the study was limited to in vitro conditions, which cannot fully replicate clinical stresses and environmental factors.

Future research should include testing crown or anatomically shaped specimens, multiple shades, and a broader range of mechanical properties, including fracture toughness, fatigue resistance, and wear behavior. Incorporating thermal cycling and simulated oral forces will enhance the clinical relevance of findings. Furthermore, combining microstructural analysis with both mechanical and optical characterization will allow for a more complete understanding of material behavior, guiding selection for durable and esthetic dental restorations.

5. Conclusions

The mechanical properties of contemporary dental ceramics are a direct manifestation of their engineered microstructure. The high-strength Zirconia E.MAX® ZIRCAD leverages a fine-grained tetragonal structure for supreme toughness, while the high-translucency Zirconias ZOLID® FX and KATANA® STML utilize a cubic-phase-dominated microstructure to achieve an optimal balance of aesthetics and strength, enhanced by a functionally graded architecture. Lithium disilicate E.MAX® CAD offers an enamel-friendly alternative based on an interlocking crystal network. This structure-property relationship provides a clear scientific rationale for clinicians to select the optimal material based on the specific biomechanical and aesthetic demands of each clinical case.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.A.-N.; methodology, L.A.A.-N. and S.N.A.; formal analysis, T.A.Z.; investigation, T.A.Z.; resources, L.A.A.-N.; data curation, T.A.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.N.A.; writing—review and editing, L.A.A.-N. and S.N.A.; visualization, L.A.A.-N.; supervision, L.A.A.-N. and S.N.A.; project administration, L.A.A.-N. and S.N.A.; funding acquisition, L.A.A.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Jordan University of Science and Technology, Deanship of Research; grant number [20190375].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the Deanship of Research; Jordan University of Science and Technology for their valuable support throughout the duration of this research. All research procedures were carried out in accordance with ethical guidelines, ensuring the safety and well-being of participants. We would also like to acknowledge Abedelmalek Tabnjah, BSDH, MDPH, from Jordan University of Science and Technology (JUST), for his invaluable statistical advice and guidance during this study. His expertise significantly contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data, thereby enhancing the overall quality of the research. L.A.A.-N. used OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT (GPT-5) for the writing process to improve readability and language during the preparation of this manuscript. After using ChatGPT, the outcomes were reviewed and edited by the authors, who declare that they are fully responsible for the content and integrity of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Miura, S.; Fujita, T.; Fujisawa, M. Zirconia in fixed prosthodontics: A review of the literature. Odontology 2025, 113, 466–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stawarczyk, B.; Keul, C.; Eichberger, M.; Figge, D.; Edelhoff, D.; Lümkemann, N. Three generations of Zirconia: From veneered to monolithic. Part I. Quintessence Int. 2017, 48, 369–380. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Naba’a, L.A. A narrative review of recent finite element studies reporting references for elastic properties of Zirconia dental ceramics. Ceramics 2023, 6, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontonasaki, E.; Rigos, A.E.; Ilia, C.; Istantsos, T. Monolithic Zirconia: An update to current knowledge. Optical properties, wear, and clinical performance. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, J.O. Zirconia: The material, its evolution, and composition. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2018, 39 (Suppl. 4), 4–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lawn, B.R. Novel Zirconia materials in dentistry. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, K.; Raigrodski, A.J.; Chung, K.H.; Flinn, B.D.; Dogan, S.; Mancl, L.A. A comparative evaluation of the translucency of Zirconias and lithium disilicate for monolithic restorations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2016, 116, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyad, T.A.; Abu-Naba’a, L.A.; Almohammed, S.N. Optical properties of CAD-CAM monolithic systems compared: Three multi-layered Zirconia and one lithium disilicate system. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A.; Büyükerkmen, E.B. Fracture resistance of CAD/CAM monolithic Zirconia crowns supported by titanium and Ti-base abutments: The effect of chewing simulation and thermocyclic aging. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2023, 38, 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontonasaki, E.; Giasimakopoulos, P.; Rigos, A.E. Strength and aging resistance of monolithic Zirconia: An update to current knowledge. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2020, 56, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhochhibhoya, A. Translucent monolithic, multi-layered Zirconia: Matching esthetics with strength. J. Nepal. Prosthodont. Soc. 2022, 5, 55730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felberg, R.V.; Bassani, R.; Pereira, G.K.R.; Bacchi, A.; Silva-Sousa, Y.T.C.; Gomes, E.A.; Sarkis-Onofre, R.; Spazzin, A.O. Restorative possibilities using Zirconia ceramics for single crowns. Braz. Dent. J. 2019, 30, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6872:2015; Dentistry—Ceramic Materials. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Pjetursson, B.E.; Valente, N.A.; Strasding, M.; Zwahlen, M.; Liu, S.; Sailer, I. A systematic review of the survival and complication rates of Zirconia-ceramic and metal-ceramic single crowns. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2018, 29 (Suppl. S16), 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, C.I.M.B.; Fernandes, G.V.O.; Azevedo, L.P.P.; Araújo, F.M.; Donato, H.; Correia, A.R.M. Clinical performance of monolithic CAD/CAM tooth-supported Zirconia restorations: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2022, 66, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewan, H. Clinical effectiveness of 3D-milled and 3D-printed Zirconia prosthesis—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C.; Rask, H.; Awada, A. Mechanical properties of resin-ceramic CAD-CAM materials after accelerated aging. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 954–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C1327-15; Standard Test Method for Vickers Indentation Hardness of Advanced Ceramics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Della Bona, A.; Anusavice, K.J.; Mecholsky, J.J. Failure analysis of resin composite bonded to ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2003, 19, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarone, F.; Di Mauro, M.I.; Ausiello, P.; Ruggiero, G.; Sorrentino, R. Current status on lithium disilicate and Zirconia: A narrative review. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, A.; Zhao, Z.; Paolone, G.; Louca, C.; Vichi, A. Flexural strength of CAD/CAM lithium-based silicate glass-ceramics: A narrative review. Materials 2023, 16, 4398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassary Zadeh, P.; Lümkemann, N.; Sener, B.; Eichberger, M.; Stawarczyk, B. Flexural strength, fracture toughness, and translucency of cubic/tetragonal Zirconia materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 120, 948–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsaka, S.E. Optical and mechanical properties of newly developed monolithic multilayer Zirconia. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, J.I.; Kwon, Y.H.; Seol, H.J. In vitro evaluation of speed sintering and glazing effects on the flexural strength and microstructure of highly translucent multilayered 5 mol% yttria-stabilized Zirconia. Materials 2024, 17, 4634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, T.; Fan, Y.; Giordano, R. Mechanical properties of translucent multilayered dental Zirconia. J. Dent. Oral Disord. 2020, 6, 1124. [Google Scholar]

- Reale Reyes, A.; Dennison, J.B.; Powers, J.M.; Sierraalta, M.; Yaman, P. Translucency and flexural strength of translucent Zirconia ceramics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2023, 129, 644–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenthöfer, A.; Schwindling, F.S.; Schmitt, C.; Ilani, A.; Zehender, N.; Rammelsberg, P.; Rues, S. Strength and reliability of Zirconia fabricated by additive manufacturing technology. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, A.; Schurig, A.; Odenthal, A.L.; Schmitter, M. Impact of different layers within a blank on mechanical properties of multi-layered Zirconia ceramics before and after thermal aging. Dent. Mater. 2022, 38, e147–e154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inokoshi, M.; Liu, H.; Yoshihara, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Tonprasong, W.; Benino, Y.; Minakuchi, S.; Vleugels, J.; Van Meerbeek, B.; Zhang, F. Layer characteristics in strength-gradient multilayered yttria-stabilized Zirconia. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 430–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendler, M.; Belli, R.; Petschelt, A.; Mevec, D.; Harrer, W.; Lube, T.; Danzer, R.; Lohbauer, U. Chairside CAD/CAM materials. Part 2: Flexural strength testing. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, A.; Vafaei, F.; Hooshyarfard, A.; Nosrati, E.; Nazari, M.; Farhadian, M. Effect of sintering temperature on flexural strength of two types of Zirconia. Front. Dent. 2022, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharishi, A.; McLaren, E.A.; White, S.N. Color- and strength-graded Zirconia: Strength, light transmission, and composition. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 1236.e1–1236.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, T.; Wertz, M.; Koenig, A.; Koetzsch, T.; Rosentritt, M. Microstructure, composition, and flexural strength of different layers within Zirconia materials with strength gradient. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, T.D.; Jessup, J.P.; Guillory, V.L. Translucency and strength of high translucency monolithic zirconium oxide materials. Gen. Dent. 2017, 65, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Tsitrou, E.A.; Northeast, S.E.; van Noort, R. Brittleness index of machinable dental materials and its relation to the marginal chipping factor. J. Dent. 2007, 35, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, O.; Watts, D.C.; Sigusch, B.W.; Kuepper, H.; Guentsch, A. Marginal and internal fit of pressed lithium disilicate partial crowns in vitro: A three-dimensional analysis of accuracy and reproducibility. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, M.A.; Campos, F.; Ramos, N.C.; Rippe, M.P.; Valandro, L.F.; Melo, R.M. Inlays made from a hybrid material: Adaptation and bond strengths. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlton, D.; Roberts, H.W.; Tiba, A. Measurement of select physical and mechanical properties of three machinable ceramic materials. Quintessence Int. 2008, 39, 573–579. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.R.; Du, W.; Zhou, X.D.; Yu, H.Y. Review of research on the mechanical properties of the human tooth. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 6, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goujat, A.; Abouelleil, H.; Colon, P.; Jeannin, C.; Pradelle, N.; Seux, D.; Grosgogeat, B. Mechanical properties and internal fit of 4 CAD-CAM block materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2018, 119, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).