Abstract

Reliable recognition of people on water from UAV imagery remains a challenging task due to strong glare, wave-induced distortions, partial submersion, and small visual scale of targets. This study proposes a hybrid method for human detection and position recognition in aquatic environments by integrating the YOLO12 object detector with optical-flow-based motion analysis, Kalman tracking, and BlazePose skeletal estimation. A combined training dataset was formed using four complementary sources, enabling the detector to generalize across heterogeneous maritime and flood-like scenes. YOLO12 demonstrated superior performance compared to earlier You Only Look Once (YOLO) generations, achieving the highest accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 0.95) and the lowest error rates on the test set. The hybrid configuration further improved recognition robustness by reducing false positives and partial detections in conditions of intense reflections and dynamic water motion. Real-time experiments on a Raspberry Pi 5 platform confirmed that the full system operates at 21 FPS, supporting onboard deployment for UAV-based search-and-rescue missions. The presented method improves localization reliability, enhances interpretation of human posture and motion, and facilitates prioritization of rescue actions. These findings highlight the practical applicability of YOLO12-based hybrid pipelines for real-time survivor detection in flood response and maritime safety workflows.

1. Introduction

In the modern world, with catastrophic events occurring more frequently, prompt response to floods is essential. Floods complicate locating people due to high water flows, limited visibility, and the ineffectiveness of standard tracking devices. Recent research focuses on recognizing body positions using 3D joint coordinates and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). Several methods have been proposed to address this issue. Recognizing human actions based on joint angles from skeleton data, developing FPGA-based real-time object detection systems for drones, and using UAVs with multispectral cameras combined with CNNs for enhanced body detection [1,2,3]. YOLO-pose enables detecting 2D joint positions without heatmaps, surpassing 90% accuracy, while BlazePose [4] combined with weighted distance methods improves body position recognition [5,6]. Deep learning techniques have been employed for real-time semantic segmentation of UAV images, and lightweight multiscale coordinate attention networks have improved pose estimation accuracy on datasets like COCO 2017 [7,8]. Systems for RGB-only human posture detection on platforms like Jetson Nano were developed, although facing computational limitations, and tracking face direction via 2D images instead of depth cameras showed higher reliability [9,10]. Further advancements include YOLOv5-HR-TCM for fast 3D human pose estimation, adaptation of visible image methods for thermal imagery using CNNs and Vision Transformers, and HOG-based RHOD algorithms for flood zone detection under adverse weather conditions [11,12,13]. YOLOv8 [14] saw improvements through new network modules, boosting activity detection accuracy, while UAV-specific YOLOv8 adaptations enhanced small object detection and reduced misses in aerial imagery [15,16]. Training YOLOv8 on high-resolution nadir images further increased detection accuracy in search and rescue operations [17]. Determining a human location and position plays a much more important role in search and rescue operations on water than standard object detection. Conventional frame boundary detection only confirms the presence of a person in the frame, but provides no information about their physical condition or likelihood of survival. In an aquatic environment, a person’s posture is a key indicator of their condition and level of danger. For example, a face-down or horizontal immobile position often indicates loss of consciousness, critical fatigue, or imminent drowning [18,19]. Conversely, a vertical position, partially raised body, or active movements usually indicate attempts to stabilize the body independently, which is associated with a higher probability of rescue. Additional important signals include the degree of immersion in water, the symmetry of limb position, the smoothness or chaos of movements, and the stability of position over time. These characteristics allow UAV operators and autonomous systems to draw conclusions about the urgency of the situation, the type of intervention required, and the priority of rescue. At the same time, the aquatic environment creates numerous complications: strong sun glare, wave distortion, periodic occlusions, and unstable object contours. Under such conditions, simple detection using a bounding box does not allow distinguishing between an unconscious person passively drifting on the surface, an active swimmer, or even floating debris, which significantly complicates real-time decision-making. That is why determining the position and condition of a person in the water is extremely important. This allows for the early detection of potentially life-threatening situations, the assessment of movement trajectories under the influence of waves, the differentiation between victims and swimmers, the prioritization of rescue operations in the presence of multiple targets, the reduction of false alarms, and the provision of more reliable navigation of unmanned aerial vehicles to people in critical condition. Thus, the integration of position analysis, spatial context, and temporal dynamics is a necessary extension of the classical approach to object detection in search and rescue operations on water, both during floods and in maritime rescue operations. The objective of this work is the development of the hybrid method for automatic and accurate human position recognition on the base 3D joints coordinates with conditions YOLO method in flood. The hybrid method emphasizes the need to provide fast processing and real-time analysis for emergency responses. In addition, several recent studies highlight important developments that directly support the need for robust human detection in water-based SAR scenarios. Wu et al. demonstrated that synthetic data generation and domain adaptation techniques can significantly improve detector robustness in conditions with limited real aerial datasets. Their Syn2Real framework showed that YOLO-based models trained with diverse synthetic scenes exhibit higher resilience to background noise, object deformation, and environmental variability, which is highly relevant for UAV-based detection over dynamic water surfaces [20]. Tjia et al. further addressed environmental instability by introducing an augmented YOLO-based approach trained on datasets simulating multiple weather, illumination, and motion conditions. Their experiments showed that such augmentation substantially increases recall and stability in realistic SAR environments, indicating that environmental diversity is essential for detecting partially visible human targets on water [21]. Guettala et al. proposed a real-time TIR-based human detection pipeline using YOLOv7 and FLIR sensors, achieving high accuracy and frame rates even for small and low-visibility human silhouettes. Their findings confirm that multi-modal sensing, particularly thermal imaging, can compensate for RGB degradation caused by reflections, submersion, and wave interference during aquatic emergencies [22]. Together, these studies reinforce the importance of combining synthetic data, environmental augmentation, and multimodal sensing—approaches that align with the hybrid recognition strategy developed in this work.

2. Methods

2.1. Datasets and Data Preparation

For a complete and comprehensive evaluation of the proposed hybrid method for detecting and recognizing people in complex water rescue operations, four representative datasets were used: SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A (Combination-to-Application Dataset), and SynBASe (Synthetic Bodies At Sea). Each dataset provides a distinct type of information and specific scenarios necessary for a comprehensive coverage of the task. Their combined use made it possible to form a model capable of generalizing different types of environments, noise levels, viewing angles, degrees of human immersion in water, and characteristics of water surface behavior. Recent research based on these benchmarks confirms both their relevance and structural limitations for SAR scenarios on water. SARD is primarily used as a land-based benchmark for detecting people and does not cover water scenes or temporal dynamics. SeaDronesSee has become the de facto standard for detecting and tracking people at sea, but it focuses on open sea conditions and only partially reflects river floods and urban flooding. C2A provides large-scale synthetic disaster scenes with a variety of human poses, but the inserted humans remain photometrically inconsistent with real flood images. SynBASe compensates for the lack of extreme marine conditions with synthetic domain generation, but its wave patterns and human behavior cannot fully replicate real-world emergencies. These limitations prompted us to combine all four datasets with additional footage from unmanned aerial vehicles and develop a hybrid method that is robust to gaps between ground, synthetic, marine, and real flood environments.

2.1.1. SARD Dataset (Search and Rescue Image Dataset)

SARD [23] is a static image dataset created specifically for detecting people in search and rescue operations. It is based on approximately 35 min of video footage, from which 1981 frames showing people were selected. All images were manually labeled using LabelImg, specifying the bounding box coordinates and classes: Standing, Walking, Running, Sitting, Lying, Not Defined. Thus, the dataset represents a wide range of behavioral states—from active movement to complete immobility (Figure 1).

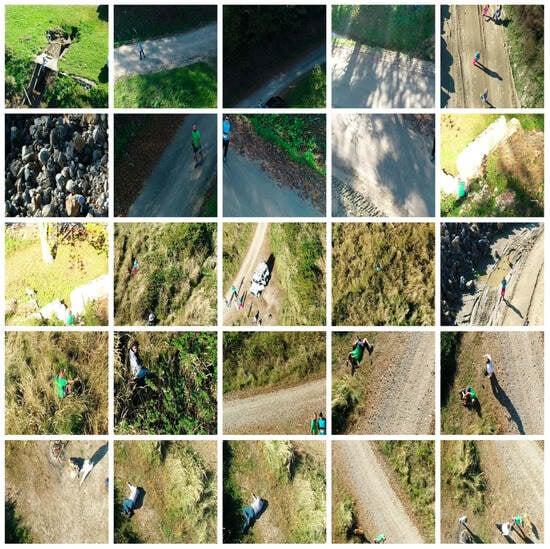

Figure 1.

Examples of images from SARD showing different human poses (standing, walking, lying) in natural ground landscapes, including tall grass, quarries, and shaded areas. The images demonstrate the diversity of backgrounds and poses typical of ground search and rescue operations.

The data covers a variety of terrain types, including dirt roads, quarries, low and high grass, forest areas, shaded areas, and other natural backgrounds. To improve the robustness of the model, the team created the SARD-Corr supplement, which contains synthetically modified images with fog, snow, ice, and sharp blurring that simulate camera movement during flight. SARD’s strengths lie in its ability to reproduce a wide range of realistic ground conditions in which victims may be found during rescue operations. The variety of poses, ranging from active movement to complete immobility, makes this set extremely useful for training models that need to recognize both dynamic and immobile people. The variety of locations, including quarries, forests, shaded areas, and tall grass, provides the complex background conditions necessary for stable algorithm performance. The additional Corr subset with fog, snow, ice, and blur further enhances the model’s ability to generalize in conditions of variable visibility and camera motion. At the same time, SARD has certain limitations. The main drawback is the lack of aquatic scenes, which makes this dataset insufficient for modeling human behavior in aquatic environments or during floods. In addition, the dataset is completely static—all images are separate frames, so it does not reflect the dynamics of movement or changes in a person’s position over time. This reduces its suitability for methods that use temporal or kinematic information. Examples of SARD images demonstrating different types of poses and complex natural scenes are shown in Figure 1.

2.1.2. SeaDronesSee Dataset (Maritime UAV Dataset)

SeaDronesSee [24] is one of the most comprehensive and accurate datasets created for research in the field of marine computer vision. It was compiled and presented by a research group at the University of Tübingen, and later officially presented at WACV 2023 as the extended SeaDronesSee Object Detection v2 benchmark. The goal of this dataset is to provide realistic and diverse data for algorithms that recognize and track people and objects in open water using drones. The current version of SeaDronesSee contains 14,227 RGB images, which are divided into three subsets: 8930 images for training, 1547 for validation, and 3750 for testing. All materials were obtained from unmanned aerial vehicles at various altitudes—from 5 to 260 m—and under a wide range of observation angles, from vertical to almost horizontal. The images are high-resolution, specifically 3840 × 2160, 5456 × 3632, and 1229 × 934 pixels, which provides detailed rendering of even very small objects, such as swimmers at a great distance. Metadata is preserved for a significant portion of the images: UAV altitude, camera tilt angle, date, time, GPS coordinates, and other parameters that often contribute to the development of multimodal approaches. Each image has annotations for several typical objects encountered in search and rescue scenarios: swimmers, people in life jackets, people on boards, boats, buoys, and rescue equipment. Some areas are marked as “ignore” if they contain ambiguous objects or objects that are difficult to label accurately. Compared to the previous 2022 version, which contained 5630 images, SeaDronesSee v2 is significantly larger and includes a deeper variety of conditions, frames, and angles. The dataset is particularly realistic in its reproduction of the marine environment. It includes scenes with calm water and intense waves, with sun glare, wave foam, and partially submerged people and objects. This makes SeaDronesSee an extremely valuable tool for simulating the real-world challenges faced by algorithms working in the context of searching for victims in the water. Additionally, the set includes video sequences that allow you to explore not only detection but also tracking of objects over time, as in single and multi-object tracking tasks. Despite its obvious advantages, SeaDronesSee also has certain limitations. Since it mainly reflects the marine environment, its characteristics do not always fully correspond to the conditions of floods in urban or river locations, where debris, infrastructure fragments, or fast, unstable currents may be present in the frame. In addition, the data was mainly collected in favorable weather conditions, so extreme scenarios, such as heavy rain or storms, are only partially represented. Despite this, SeaDronesSee remains one of the highest quality and most representative datasets for detecting people in open water areas and is a key component of modern methods in maritime SAR computer vision. Examples of SeaDronesSee marine scenes with different wave types and human immersion levels are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Typical examples of images from SeaDronesSee, containing open water scenes with varying shooting heights, waves, glare, and partially submerged people. The images demonstrate the main challenges of maritime detection: strong mirror reflections, a wide range of object sizes, and complex lighting conditions.

2.1.3. C2A (Combination-to-Application Dataset)

C2A (Combination-to-Application Dataset) [25] is one of the most specialized and methodically designed datasets created for the development of automatic human detection systems in natural disaster scenarios. Its emergence is due to a significant shortage of UAV datasets suitable for training models that simultaneously combine realistic scenes of natural disasters and authentic images of human poses. C2A fills this gap with a large-scale synthetic approach that integrates real images of destruction with artificially inserted human figures of various types, providing exceptional diversity and control over scene complexity. At its core, C2A combines two independent but complementary sources: real background images from AIDER, a dataset dedicated to aerial photography of natural disaster areas, and a wide range of human poses from LSP/MPII-MPHB, which provides high flexibility in behavioral scenarios. As a result, C2A has created a unique collection of 10,215 high-quality images featuring over 360,000 annotated human figures in various body positions. The dataset covers five types of poses—from standing upright to lying down and semi-bent positions typical of real victims in emergency situations. Another key advantage of C2A is the breadth of scenarios represented. The set covers four main categories of disasters: fires and smoke, floods, building collapses, and man-made accidents on roads. This diversity allows the model to learn in conditions with significant changes in the environment—from dust and smoke to wet or flooded surfaces, from chaotic debris to deformed structures (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Examples of synthetic and mixed scenes from C2A, where various types of disasters are simulated: floods, fires, destruction, and road accidents. The images show different poses of people inserted into realistic background scenes with high complexity and numerous occlusions.

The images have different resolutions—from 123 × 152 to 5184 × 3456 pixels—which allows for adaptation to different optical configurations, including low-quality frames or shots from high altitudes. All human figures in C2A are accurately annotated using bounding box markings, allowing this dataset to be used for a wide range of tasks—from basic detection to multi-position analysis, risk assessment, victim search, and training models that operate in heterogeneous environments. The overall structure of the dataset is designed to reflect the complexity of real-world search and rescue operations as much as possible: a large number of small objects, sharp contrasts, partial occlusions, uneven lighting, and situations where people are difficult to distinguish from the background. The creation of C2A was motivated by the real needs of industry and rescue services, which increasingly rely on UAV systems for rapid survey of large areas after disasters. The authors of the dataset sought to lay the groundwork for the development of computer vision methods that not only identify people in controlled environments, but also remain accurate in truly complex and critical environments. Thus, C2A is designed not only to improve the accuracy and generalizability of models, but also to accelerate the implementation of AI solutions in real search and rescue operations, where these technologies can play a decisive role and potentially save lives.

2.1.4. SynBASe—Synthetic Bodies at Sea

SynBASe [26] is a specialized synthetic dataset developed for research in the field of search and rescue in the marine environment using unmanned aerial vehicles. Its main purpose is to compensate for the significant lack of high-quality data in maritime SAR scenarios, where the collection of real images is often limited by the complexity of shooting conditions, the risk to rescue services, and the minimal number of available victim poses. The dataset was created using the Unreal Engine 4, which allowed for a high level of photorealism and flexible control over environmental conditions. The dataset consists of 1295 synthetic RGB images of a single size of 1200 × 1200 pixels. All images contain one or more human figures of the “swimmer” category, which corresponds to the most critical object for maritime search and rescue operations. In total, SynBASe contains 3415 annotated bodies, giving an average of 3.76 people per image, ranging from one to twelve. Annotations are available in three formats—COCO, YOLO, and PASCAL-VOC—which greatly facilitates the integration of the dataset into various machine learning frameworks. SynBASe was created as a synthetic analogue of real marine scenes from the SeaDronesSee dataset: the image structure, angles, and composition were modeled according to the “swimmers” subcorpus of SeaDronesSee. When forming synthetic scenarios, the authors also preserved the characteristic statistics of real frames: the number of people in the scene, their distribution in space, the average relative bounding box area, and other parameters. That is why the number of bodies in the image and their variability in SynBASe almost completely correspond to the real distribution in SeaDronesSee, although the average value is slightly higher (3.76 ± 2.82 vs. 3.42 ± 2.78). A particular advantage of SynBASe is its ability to simulate complex weather and lighting conditions that are critically difficult or impossible to capture in reality. The set includes scenes with fog, rain, low light, twilight glare, and enhanced reflections on waves. These modifications were not created manually, but were automated using UE4 generative modules, which guarantees the consistency of the physical simulation. In addition, the code for creating these domains and instructions for regenerating them are publicly available, making SynBASe a reproducible and flexible resource for further research. Compared to SeaDronesSee, SynBASe has two strategic advantages: control over the environment and scalability. Unlike a real dataset, which is limited by actual shooting conditions, SynBASe allows for precise adjustment of angles, lighting, wave processes, and behavioral poses (Figure 4). This makes it a valuable addition for training models that operate in the extreme conditions of maritime rescue operations, where real data is often insufficient.

Figure 4.

Examples of synthetic marine scenes from SynBASe. The images show different weather conditions, degrees of water turbulence, and poses of partially submerged bodies, with high photorealism and controllable scene parameters.

However, the dataset also has natural limitations due to its synthetic origin. Despite their high photorealism, the images cannot fully reproduce the complex spectral and chaotic effects of the real sea surface under the influence of wind, currents, or unpredictable human behavior in real emergency situations. Therefore, SynBASe is considered optimal for use in conjunction with real datasets such as SeaDronesSee, providing models with an important stage of preliminary training and domain expansion.

2.1.5. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

The data preparation process included both the unification of heterogeneous datasets (SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, and SynBASe) and the preprocessing of video streams from unmanned aerial vehicles to extract informative frames for further analysis of human poses and coordinates. All images and video frames were resized to a uniform size of 640 × 640 pixels, normalized, and cleaned of noise typical of aquatic environments and aerial photography. Preliminary image processing was performed using the OpenCV library, which provided photometric and geometric correction. Video processing began with breaking the stream into individual frames. Since real videos from UAVs often contain a significant amount of irrelevant segments without the presence of people, a mechanism for automatic selection of relevant frames was implemented. For this purpose, the dense optical-flow motion analysis based on the Farnebäck algorithm [27,28], was employed, as implemented in OpenCV. This research uses the Farnbek optical flow method, as it is one of the most stable and computationally easy algorithms for analyzing motion in low-contrast conditions and with a large number of small local changes characteristic of water surfaces. Unlike classical gradient methods, such as Lucas–Kanade, which involve calculating motion in small local windows and are sensitive to noise and glare, the Farnbek algorithm uses a polynomial approximation of image intensity, which provides a more stable motion estimation on the heterogeneous texture of waves. In addition, modern deep methods (RAFT, PWC-Net) demonstrate high accuracy but are not suitable for real-time use on UAV onboard platforms due to their excessively high computational complexity [29]. The configuration parameters were set as follows: pyramidal scale = 0.5, pyramid levels = 3, window size = 15 pixels, iterations per level = 3, polynomial neighborhood size = 5 pixels, and σ = 1.1. This setup provides a pixel-wise motion field, enabling the discarding of static fragments and focusing computations on regions with consistent motion patterns associated with humans on the water surface.

A Gaussian filter [30] was used to eliminate high-frequency noise caused by small wave oscillations, water surface glare, and sun glare. In cases of complex lighting or significant contrast between the human body and the water surface, threshold segmentation was used to separate the object from the background even in conditions of low visibility or strong reflections. After filtering the frames, human motion tracking was performed using a Kalman filter [31,32]. The use of Kalman-based prediction is essential for ensuring temporal consistency in highly dynamic aquatic environments, where reflections, wave-induced occlusions, and fluctuating contours frequently lead to short-term loss of detections. Recent studies have shown that improved variants of the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) significantly enhance stability and accuracy in noisy water environments, particularly in underwater navigation and surface tracking tasks [33], which supports our choice of Kalman-based tracking for maritime and flood scenarios. This approach is critically important in dynamic marine and flood environments, where a person may periodically disappear behind waves or change their posture unevenly. After video processing was completed, the selected frames were integrated with four main datasets, and all annotations were converted to a single format compatible with YOLO. As part of domain adaptation, brightness normalization, color temperature correction, synthetic texture smoothing, and visual style matching between real and synthetic images were performed. Detected false bounding boxes were automatically removed or corrected. The final stage of preparation included the formation of train/validation/test samples with control to ensure that frames from the same SeaDronesSee video did not fall into several subsets at the same time. This prevented the leakage of temporal information and ensured an objective assessment of the model’s generalization ability. Together, the preprocessing steps—motion analysis, noise filtering, segmentation, tracking, and domain normalization—made it possible to form a high-quality, structurally coherent, and trainable model sample focused on accurate human recognition in complex aquatic conditions. To ensure complete transparency and reproducibility of the experiments, an integrated description of all data sources used during the training of the YOLO12 model was created. Since each of the basic datasets SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, and SynBASe demonstrates significant differences in background types, human poses, interference intensity, and shooting conditions, combining these samples provided a wide range of scenarios necessary for generalizing the model in complex aquatic environments. It is particularly important to note that no fragments of the real video sequences we collected were used for training. They were reserved exclusively for the stress testing phase, which completely eliminates the possibility of data set overlap and guarantees the objectivity of the experimental results. The generalized structure of the training data used is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Training data structure.

This combination of diverse sources made it possible to avoid the dominance of any single domain and to form a balanced training sample that includes both controlled laboratory conditions and simulated extreme marine situations. This ensured the model’s high ability to adapt to the variability of wave texture, bright glare, partial occlusions, and different levels of human immersion in water.

2.2. Simulation Research

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method in conditions close to real water rescue operations, a simulation environment was created, focused on the use of the Raspberry Pi 5 (Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK, sourced in Kyiv, Ukraine) onboard hardware platform. This single-board computer model, equipped with a quad-core ARM Cortex-A76 (Arm Ltd., Cambridge, UK) with a clock speed of 2.4 GHz, an accelerated VideoCore VII GPU, and improved memory bandwidth, is a representative example of a modern low-power edge processor for unmanned aerial vehicles. The increased performance of the Raspberry Pi 5 compared to previous generations allows for more efficient real-time neural network inference, which is critical for search and rescue tasks. The Reaper 7 drone (custom UAV platform, assembled in Ukraine) served as the test platform for the system, which, thanks to its high speed, large range, and payload capacity, provides conditions close to real-world application. The UAV is equipped with a CADDX H1 camera (Caddx Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) and a PandaRC 2.5W 5.8G transmitter (PandaRC, Shenzhen, China), which provide a stable wireless video stream to the Raspberry Pi 5, which simulates onboard data processing during flight. The simulation environment included real video recordings of water surfaces with various hydrodynamic conditions: wave turbulence, glare, splashes, variable light intensity, and partial occlusions. The use of real data ensured natural variability in the environment and allowed for the reproduction of the types of noise that most complicate the detection of people in the water during rescue missions. In this environment, the YOLO12 model was integrated into the Raspberry Pi 5 onboard conveyor and performed real-time video stream analysis. Thanks to the increased performance of the processor and GPU, YOLO12 ensured stable frame processing at a high frequency and accurate human recognition even in conditions of strong glare, low contrast, and partial immersion. The results showed that the improved YOLO12 architecture maintains high resistance to background noise and dynamic artifacts characteristic of aquatic environments. In addition, targeted optimization of the system’s software was carried out to ensure stable real-time operation on the Raspberry Pi 5 hardware platform. In particular, the number of intermediate frame preprocessing operations was reduced, normalization and scaling procedures were optimized, and accelerated SIMD implementations of basic OpenCV operations were applied. The YOLO12-s inference module operated in a fixed input tensor size mode and static initialization of computational graphs, which minimized delays between consecutive frames. At the hardware level, active cooling and SoC high-performance mode were used to prevent thermal throttling. Thus, the performance indicators obtained are the result of a combination of an optimized software stack and stable temperature control, which meets the requirements for UAV onboard systems in real operating conditions. The simulation results confirm that the combination of the lightweight YOLO12 architecture with the modern Raspberry Pi 5 edge platform ensures full real-time operation of the system, opening up the possibility of its practical application on board unmanned aerial vehicles. This combination ensures fast and reliable detection of people on the water surface, which is a key factor in the success of rescue operations in emergency situations.

2.3. Hybrid Method

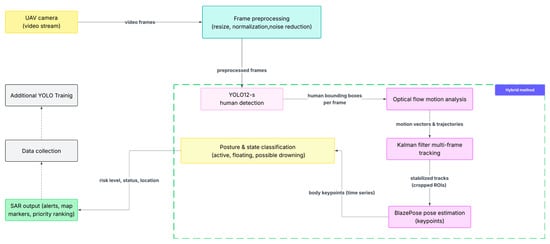

The hybrid method developed in this research is based on the YOLO12 architecture and integrates multiple complementary techniques to improve the detection and analysis of people on water. The selection of YOLO12 was driven by its significant advancements over previous YOLO versions, offering higher detection accuracy, improved generalization across complex environments, and better robustness to environmental noise such as water reflections and dynamic lighting conditions. YOLO12 integrates modern deep learning practices, including novel backbone architectures, advanced data augmentation strategies, and enhanced loss functions, which collectively enable superior performance in real-time applications. These capabilities make YOLO12 particularly suitable for detecting small or partially submerged objects on water surfaces, ensuring reliable identification of individuals in critical rescue scenarios [34]. The method combines real-time object detection, motion analysis, joint coordinate estimation, and continuous data refinement. Initially, YOLO12 is used to rapidly and accurately detect human in the video frames, even under challenging aquatic conditions [35]. Following detection, motion analysis is conducted using dense Farnebäck optical flow, which estimates a pixelwise motion field between consecutive frames and is used to identify movement directions and speeds by tracking coherent motion patterns around each detected person. Once motion has been identified, BlazePose library is applied to estimate key body joint coordinates, enabling the detailed analysis of posture and movement patterns, even in cases of partial submersion or low visibility. After obtaining pose information, the system refines the data by filtering out noise, irrelevant frames, and artifacts caused by environmental factors such as water glare or debris. This ensures that only high-quality, meaningful data are used in subsequent steps. The refined detection, motion, and pose information are then synchronized and analyzed collectively to build a comprehensive model of human behavior. Finally, the optimization and feedback loop stage retrains and fine-tunes the detection model based on the filtered and synchronized data, continuously improving the accuracy, robustness, and adaptability. This multi-stage integration ensures precise human recognition, efficient tracking, and reliable real-time performance, providing a strong foundation for UAV-assisted operations over water environments. The full pipeline of the proposed hybrid method is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Overall pipeline of the proposed hybrid method integrating YOLO12 detection, motion analysis, Kalman filter and BlazePose pose estimation.

2.3.1. Optimizing Video Data and Object Detection

AI that processes video in real time needs to optimize input data to detect people quickly. For this purpose, video compression and frame size reduction algorithms are used to reduce the amount of data without losing important information. Popular compression standards, such as H.264, H.265 (HEVC), and VP9, use frame prediction, encoding only the changes between consecutive frames. Reducing the resolution or cropping non-informative parts also effectively reduces the load on the system without significant loss of quality. Choosing a modern codec, such as HEVC, provides a better balance between quality and file size. Adaptive video transmission via MPEG-DASH or HLS protocols is used for stable broadcasting in conditions of variable network quality. Frame interpolation reduces the number of frames per second without losing the smoothness of playback. Removing noise before compression improves video quality and makes it easier to process. To avoid delays in data transmission, video processing can be performed directly on board the drone using microcomputers (e.g., Raspberry Pi or Orange Pi). This reduces the time from shooting to frame analysis. To track people in the video stream, Kalman Filter and SORT algorithms are used, which efficiently process data in real time. Multithreading and parallel processing on multi-core processors or clusters of microcomputers accelerate the detection of people in large amounts of video data. If it is possible to transfer data to a remote server, graphics processing units (GPUs) are used, which significantly speed up object recognition due to their efficiency in parallel computing.

2.3.2. Joint Detection Movement and Position Analysis

The hybrid method uses dense Farnebäck optical flow to analyze human movement. Optical flow is a technique in computer vision used to determine the motion of objects between two consecutive frames of video based on changes in the visual scene. This method is particularly useful for analyzing motion in images where objects can change their position or orientation. Its application to detecting people on the surface of water during floods involves several key aspects: Optical flow analyzes changes in the location of pixels between consecutive frames. Based on these changes, it determines the direction and speed of a person’s movement. Each pixel or group of pixels receives a vector showing the direction and magnitude of the movement. Optical flow allows detecting and tracking movements on the water surface, which can indicate the presence of people. This is especially useful when people are partially submerged or difficult to recognize for other reasons. By analyzing the motion pattern, different types of activity can be identified, such as whether a person is swimming, floundering for help, or stationary. Optical flow can also be integrated with other image analysis systems, increasing the overall accuracy of detecting and identifying people on the water surface. This method allows for the rapid detection and tracking of potentially injured people in real time, which is critical for effective rescue operations. To determine the coordinates of the joints and analyze the pose, BlazePose library is used, which specializes in detecting and tracking key points of the human body in real time. BlazePose is able to accurately locate key points on the human body, even in difficult conditions. This includes detecting hands, feet, head, and other important body parts that may be partially visible or submerged in water during a flood. This precise detection capability allows for rapid response by identifying the location and condition of individuals who may need assistance. It should also be noted that the use of such technology in extreme conditions such as floods has certain challenges. For example, variable lighting conditions, water, and other unpredictable elements can make it difficult to accurately determine positions. Therefore, continuous improvement of the algorithms and their adaptation to specific conditions are key to ensuring BlazePose’s effectiveness in such scenarios.

2.3.3. Filtered Data Refinement

In flood scenarios, where environmental conditions can change rapidly, data filtering plays an important role in improving the accuracy and effectiveness of AI models for human detection. In this context, the filtering process involves removing noise, irrelevant information, and erroneous data that may arise from challenging conditions such as rough waters, light glare, floating objects, and other visual challenges. To improve the accuracy of the YOLO12 model in flood conditions, a key step is to use the filtered data to retrain it. This process involves several critical steps that allow the model to better adapt to the specific conditions and challenges of flooding. Before using the data for model training, it must be carefully filtered. Data filtering before model training is aimed at removing noise and improving the quality of video or images. One way of filtering is to use anti-aliasing filters to reduce noise in images, which eliminates random reflections on water and other visual artifacts. This helps make objects in the image clearer and easier to identify. In addition, lighting and contrast correction, such as histogram equalization, improves the visibility of objects in dark or over lit areas. This allows you to better distinguish people on the water surface, even in difficult lighting conditions. To optimize the training dataset, it is important to filter out irrelevant frames that do not contain useful information. Classification and time series analysis algorithms help to identify and select only those frames where there is a potential human presence. All of these data filtering steps significantly improve the quality of information used to train the YOLO12 model. As a result, the model becomes more adapted to detecting people in difficult flood conditions, increasing the accuracy and reliability of the hybrid method.

2.4. Training and Testing Neural Network Procedure

After preprocessing the images and filtering the data, people were detected using neural networks based on the YOLO architecture. The model was trained on a combined dataset that included four separate datasets: SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, and SynBASe. This approach provided the necessary variety of scenes, lighting types, observation angles, levels of human immersion in water, as well as sea and rescue conditions. The SARD data contains individual RGB frames obtained from video recordings, but the dataset itself does not contain video files and consists exclusively of 1981 images with different human poses and complex landscapes. SeaDronesSee, on the other hand, includes both RGB images (14,227 frames) and annotated video sequences, providing realistic water surface characteristics, reflections, variable viewing angles, and different UAV flight heights. Additional C2A and SynBASe datasets provided coverage of synthetic sea conditions, varying levels of water agitation, and varying degrees of human partial submersion. To train the model, all images were standardized to a single format, normalized, and classic augmentation techniques (scaling, rotation, random contrast and lighting changes) were applied to improve the network’s generalization ability. YOLO12 was trained using the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.01, a batch size of 64, and 50 training epochs, which ensured balanced model convergence without overfitting. During training, the model predicted the bounding box coordinates for each potentially present person on the water surface. To improve detection accuracy, SeaDronesSee metadata was additionally used, in particular the drone’s flight altitude and camera angle, which allowed for stabilizing the scale estimation of objects and compensating for perspective distortions. For validation, the standard SeaDronesSee validation set (1547 images) was used, as well as corresponding subsets from C2A and SynBASe. Testing was performed on the SeaDronesSee test subset (3750 images) and separate parts of other datasets that were not included in the training sample. This experimental design ensures that the model’s results are evaluated on qualitatively different scenes, including strong glare, low contrast, water waves, floating objects, and partial human occlusion. Additionally, stress testing was performed on real data obtained from UAVs, including two sequences recorded over a fast-flowing river and three recordings captured during heavy rain, with a total duration of approximately 18 min and about 21,600 frames (Figure 6).

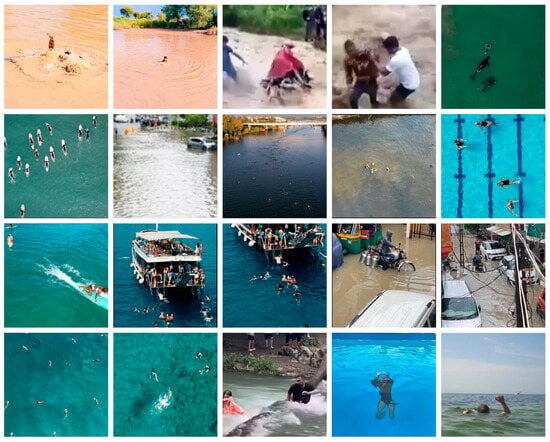

Figure 6.

Examples of real-world aquatic scenarios from the collected dataset. The images illustrate diverse environments such as rivers, coastal areas, open water, swimming pools, and urban floods, capturing swimmers, people in distress, rescue interactions, and small vessels under varying visibility and motion conditions.

These recordings were annotated with the same object classes as the SeaDronesSee dataset, namely swimmers, people in life jackets, and small boats or floating debris. It is important to note that Farnebäck optical flow and Kalman filter–based tracking modules were applied exclusively to video data. The evaluation was performed on the SeaDronesSee dataset, which contains several annotated video sequences with an average duration of 20–45 s. These sequences include object classes such as swimmers, people in life jackets, people on boards, boats, and buoys and were used to verify the temporal consistency of the proposed tracking method. In contrast, the static datasets SARD, C2A, and SynBASe were used exclusively for training and validating the detection components of YOLO12. No evaluation of tracking methods was performed on these static datasets. This division ensures that optical flow and the Kalman filter are used only in conditions where temporal information is available, while static datasets contribute to the robustness and generalizability of the detection model. Final optimization involved applying a dedicated formula to fine-tune network parameters, ensuring optimal recognition performance:

where —general error on the dataset, —loss function that determines the difference between the actual and predicted values, —is the actual value of the label for the i-th sample, —is the predicted value of the model for the i-th sample with parameters θ, —number of samples in the dataset.

2.5. Ablative Research of YOLO Architectures

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed system in search and rescue operations on water, we conducted a comparative analysis of several YOLO architectures, from early classic detector YOLOv4 to modern lightweight models (YOLO11 and YOLO12). Although several generations were tested for comparison (see Table 2), the main model used in all subsequent experiments in this work is YOLO12, due to its excellent balance between accuracy and efficiency, as well as its reliability in aquatic environments. As part of the ablation analysis, the YOLOv4 [36] model was deliberately included as a classic baseline detector, which is traditionally used in UAV-based human detection tasks and in most early studies on the SeaDronesSee and SARD datasets. Although YOLOv4 was proposed in 2020, it continues to serve as a benchmark due to its high stability, well-documented behavior, and widespread use in search and rescue operations. It is based on CSPDarknet53 with Mish activation, a multi-scale FPN-PAN structure, and improved feature aggregation mechanisms, providing a moderate trade-off between accuracy and speed [37,38]. The inclusion of YOLOv4 allows us to quantitatively demonstrate the advantages of modern YOLO11 and YOLO12 models over classical architectures and ensures the correct reproducibility of experiments in line with previous work. This highlights the limitations of Darknet- and CSPDarknet-based base structures when applied to dynamic water surfaces. YOLO8 served as an important transitional model, offering improved detection of small objects thanks to its anchor-free design and redesigned Neck structure. However, its increased memory footprint reduces its suitability for real-time use on unmanned aerial vehicles, especially in limited onboard computing environments. YOLO11 [39] and YOLO12 [40] demonstrated the highest detection accuracy across all datasets in the ablation study (SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, SynBASe). YOLO11 gained an advantage through improved feature aggregation, but it was YOLO12 that consistently demonstrated the best overall performance, combining lower FLOPs, higher FPS, and improved accuracy for small partially submerged targets. Importantly, YOLO12 outperformed YOLO8 despite having fewer parameters and lower computational costs. Given this remarkable stability and efficiency, YOLO12 was chosen as the primary architecture for all main experiments, evaluation, optical flow integration, Kalman tracking, and pose-based refinement modules. The hybrid system combining YOLO12 with motion and position signals demonstrated the highest accuracy among all tested configurations, showing increased robustness to wave dynamics, surface reflections, and partial occlusions. Ablation at the dataset level (Table 2) further confirmed that YOLO12 maintains high performance across all domains, achieving the highest mAP and Recall values when trained on the combined dataset. This highlights the importance of domain diversity and justifies the choice of YOLO12 as the main detector for the proposed water SAR structure.

Table 2.

Ablation analysis of YOLO models on different datasets.

2.6. Justification for Choosing the YOLO12 Model

A systematic evaluation found that the YOLO12 architecture has the most suitable properties for operations in an aquatic environment. Its distinction lies in the use of advanced feature aggregation and attention mechanisms, which significantly improve the ability to localize objects with a small projection area and unstable contours. This is critically important for detecting people who are partially submerged, disoriented in space, or located at a considerable distance from the UAV camera. Combined with an updated multi-level feature extraction system, YOLO12 demonstrates higher resistance to noise caused by wave deformations, sun reflections, and the non-stationary texture of the water surface. Particular attention was also paid to the computational efficiency of the models, as the target application involves operation on board unmanned aerial vehicles with limited hardware resources. In this context, YOLO12 proved to be the best compromise between complexity and accuracy. Its computational cost was lower than that of YOLOv8, while its actual accuracy exceeded the results of all previous generations. This indicates an optimized architecture capable of delivering high computational speed on low-power devices, including Raspberry Pi, in accordance with real-time requirements. Further experiments on all datasets showed that YOLO12 achieves the highest mAP@0.5, and Recall scores on both real SeaDronesSee maritime images and synthetic C2A and SynBASe datasets. Unlike other models, it maintains detection stability under domain mismatch conditions: transitions between land, sea, and simulated scenes have virtually no impact on the model’s generalization ability. This is especially important for a task in which real flood data is limited, and therefore the training process inevitably requires the use of heterogeneous sources. It has also been found that the YOLO12 output is characterized by a lower level of object boundary fluctuations and less sensitivity to short-term lost fragments. Thanks to this, the model naturally combines with other components of the hybrid method, such as the optical flow algorithm, the Kalman filter, and pose estimation using BlazePose. This combination ensures stability and reliability in consecutive frames. Taken together, architectural updates, empirical advantage on multi-domain datasets, high resistance to water artifacts, and compliance with computational constraints have proven YOLO12 to be the most suitable model for further development and integration into a human recognition system on water.

3. Results

3.1. Human Recognition

The first stage of the proposed method involves recognizing people in a video stream above the water surface, which is received from the onboard camera of an unmanned aerial vehicle. In this research, the YOLO12 model is used to localize people, integrated into a hybrid method that combines spatial feature analysis, motion information, and pose estimation. This approach provides a more informative representation of the scene compared to using only classical detection, which is critically important in the dynamic and noisy conditions of the aquatic environment. Figure 7 shows an example of basic human detection using YOLO12. The model localizes the object based on spatial features, successfully identifying a person even in situations where the body is partially submerged, merging with the background, or distorted by wave structure. A distinctive feature of aquatic scenes is that the contours of objects change over short time intervals, so accurate localization of a person in each individual frame is fundamentally important for further processing.

Figure 7.

Human detection by YOLO12.

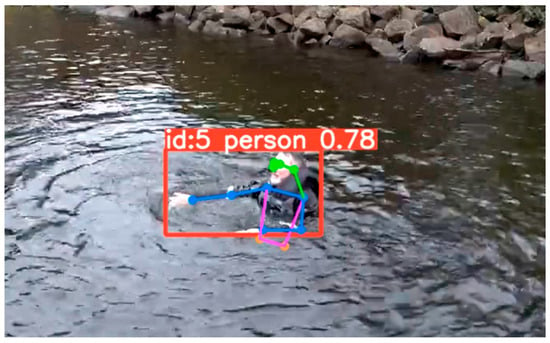

However, detection alone does not provide enough information to assess a person’s condition, orientation, or activity. That is why, after determining the area where a person is located, the BlazePose pose estimation module is used, which allows reconstructing the body structure as a set of key points. This module provides interpretation of a person’s shape and position in conditions of partial visibility—situations where waves or water movement obscure the lower limbs or distort the contours of the torso. BlazePose demonstrates high resistance to such distortions, as it models not only the external contours but also the internal structure of the body. Figure 8 shows an example of key points being applied to a detected object. For the system, this is the basis for further analysis of the situation: a horizontal posture may indicate a loss of energy, a vertical posture may indicate an active struggle to stay afloat, and uneven limb movement may indicate panic or fatigue. Tracking these characteristics over time allows the model to make assumptions about the level of risk for each detected person.

Figure 8.

Object recognition result with key points using BlazePose.

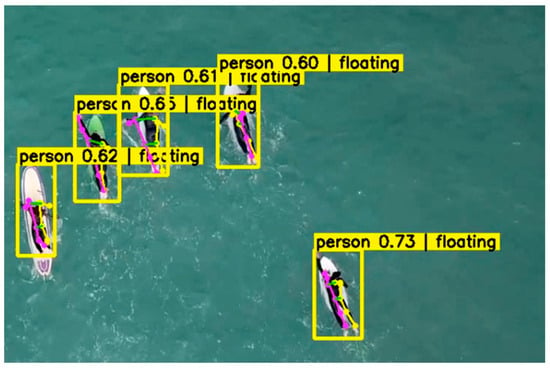

The next important aspect is motion analysis. Since the water surface is highly variable, the system must distinguish between actual human motion and the motion of waves, splashes, or reflections. To do this, subsequent modules of the hybrid method use the results of the initial YOLO12 localization and BlazePose keypoints to form a spatio-temporal trajectory of the person. Even if some parts of the body temporarily disappear from the frame due to wave distortions, the preliminary skeleton structure and predicted points allow the analysis to remain intact. The module’s ability to work in cases where several people are on the water at the same time is particularly important. After initial detection, each object receives its own skeletal model and individual motion trajectory. This allows each person to be treated separately, analyzing their position, movements, and possible signs of disorientation or unconsciousness. Figure 9 shows an example of a situation where the system simultaneously localizes and analyzes the positions of several people.

Figure 9.

Detection and pose estimation of multiple humans on water using the hybrid method.

The key advantage of the method is that the system not only detects the presence of a person in the frame, but also provides semantic information about their position and behavior. This opens up the possibility for a more in-depth analysis of the situation: whether the person is actively moving, diving into the water, or changing their body orientation. Such information is vital in search and rescue operations, as it can serve as an indicator of the degree of danger and help make operational decisions regarding the priority of assistance. The method demonstrates that the combination of YOLO12 and BlazePose significantly enhances the system’s capabilities when operating in complex hydrodynamic conditions. Primary detection provides object segmentation, while pose estimation provides further structuring. This creates the basis for a complete hybrid method that includes motion analysis, trajectory prediction, and state estimation in a dynamic water surface environment. As a result, the YOLO12-based recognition module, combined with BlazePose, forms the first level of a multi-stage analysis system that not only detects a person but also provides a deep interpretation of their spatial and behavioral characteristics on the water. This approach provides a basis for further integration with decision-making scenarios and automated rescue algorithms, making the proposed system effective for real-world application in high-risk environments.

3.2. Evaluation Metrics and Comparative Analysis of YOLO Models

To evaluate the accuracy of the proposed detection model, the F1-Score is used. The F1-Score represents the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balanced measure of the model’s ability to correctly identify positive instances while minimizing both false positives and false negatives. This metric is especially useful in domains where the cost of misclassification is high, such as search-and-rescue scenarios on water.

where represents the proportion of correctly predicted positive cases relative to all cases that the model identified as positive. This reflects how well the detector avoids false positives caused by reflections, waves, or other visual artifacts on the water surface. It is computed as:

Recall (or Sensitivity) quantitatively evaluates the model’s ability to detect all actual positive cases in a scene. A high Recall value indicates that the detector successfully identifies people even when partially occluded, in low contrast, or with dynamic wave interference. It’s calculated as:

denote correctly identified human instances, refer to non-human objects incorrectly classified as people, and are cases where the detector fails to identify a person who is present in the frame. These three categories form the basis of all performance metrics and allow a comprehensive quantitative evaluation of the detection system. Within the scope of this study, different generations of YOLO models—YOLOv4, YOLOv8-s, YOLO11-s, and YOLO12-s—were compared to determine their suitability for recognizing people on water surfaces. Each subsequent version of the YOLO architecture demonstrates gradual improvements in network structure, feature aggregation mechanisms, optimization strategies, and resistance to visual distortions. YOLOv4 improves accuracy through enhanced multi-level feature aggregation, the use of Mish activation, and attention mechanisms, but its architecture remains less flexible compared to newer models. YOLOv8-s demonstrates the most significant leap in performance thanks to its modular structure, optimized detection head, improved generalization mechanisms, and increased efficiency for small and partially occluded objects. YOLO11-s further improves accuracy and stability by optimizing feature transfer and improving performance with small objects in high-noise conditions. YOLO12-s, according to the analysis, demonstrates the best balance between accuracy, speed, and resistance to visual deformations, providing the highest mAP values and the lowest computational complexity among the tested models. The results shown in Table 3 demonstrate the evolution of the performance of different generations of YOLO models when trained on a combined dataset containing various scenes with people in an aquatic environment, including different lighting conditions, wave levels, and degrees of immersion. Comparison by key metrics—mAP@0.5, Recall, Precision, F1-score, and integral mAP@0.5:0.95—allows us to evaluate not only the ability of models to detect the presence of a person in the frame, but also the accuracy of object boundary localization. YOLOv4 improves accuracy through advanced feature processing mechanisms. YOLOv8-s takes a noticeable step forward, significantly improving Recall and mAP metrics. The YOLO11-s and YOLO12-s models demonstrate the highest performance among all tested architectures, indicating improved generalization ability and resistance to distortions caused by water dynamics and glare. Crucially, YOLO12-s demonstrates high accuracy with reduced computational complexity, which is critical for onboard UAV systems.

Table 3.

Results on the training set.

After training, the model was validated on the testing set. Table 4 presents the results of testing the models on an independent dataset that includes scenes not present during training. Evaluation on such data is key to determining the model’s actual ability to perform correctly in conditions close to practical search and rescue scenarios.

Table 4.

Results on the testing set.

The drop in performance of YOLOv4 on the test set indicates the limited ability of these models to adapt to complex water conditions. YOLOv8-s provides significantly higher stability, but is inferior to YOLO11-s and YOLO12-s in terms of accuracy and completeness of detection. The YOLO12-s model demonstrates the best balance between Precision and Recall, which is especially important for rescue tasks: an excess of false positives complicates data processing by the operator, while missed people directly endanger the lives of victims. High values for mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95 also indicate the model’s confidence in localizing people even with strong background fluctuations and partial body invisibility. This makes YOLO12 one of the most promising methods for autonomous monitoring of flooded areas.

The error analysis presented in Table 5 allows for a more in-depth assessment of the practical reliability of each YOLO model in complex aquatic environments. This type of assessment is particularly important for search and rescue tasks, where different types of errors have varying degrees of criticality, and any missed detection can have dangerous consequences. When comparing models, we can clearly see the evolution of algorithm stability to typical water artifacts, such as glare, ripples, waves, and partial human immersion in water.

Table 5.

Percentage of errors on the testing.

YOLOv4 improves the situation thanks to its extended architecture and attention mechanisms, but it is still vulnerable to a large number of misses, especially in scenes with significant glare or strong water turbulence. YOLOv8-s shows a noticeable reduction in both types of errors. Improved separation of objects from noise reduces FP, while the updated detector head structure positively affects the ability to detect partially occluded people. However, YOLOv8-s can still misinterpret small visible body parts or mixed structures, leading to an increased level of partial detections. More modern architectures—YOLO11-s and YOLO12-s—demonstrate significantly better results. YOLO11-s reduces the number of errors thanks to an improved hierarchical feature transfer mechanism and improved localization stability. However, it is YOLO12-s that shows the lowest FP, FN, and partial detection values. This demonstrates its ability to distinguish humans even in low-contrast conditions, with significant occlusions, and in the presence of complex water structures, which often mislead previous models. Importantly, YOLO12-s demonstrates the lowest number of missed detections, which is a critical factor for rescue operations where the priority is to maximize the coverage of real positive cases. The low false alarm rate also reduces the cognitive load on operators and increases the overall response speed of the system. Taken together, these results emphasize that modern architectures, especially YOLO12-s, are much better suited for use in automated water search and rescue systems because they combine high localization accuracy with a low rate of critical errors.

3.3. Ablation Research of Hybrid Method Components

In order to determine the actual contribution of each functional module of the hybrid method for recognizing people on water, an ablation study was conducted based on the YOLO12-s model trained on a combined dataset (SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, SynBASe). Since all configurations use the same detector, the values of mAP@0.5 remain unchanged. This allows us to evaluate the impact of auxiliary modules—motion analysis, tracking, and pose estimation—on the accuracy and stability of the system in a dynamic aquatic environment. The basic YOLO12-s configuration provides high-quality localization but remains sensitive to false positives caused by glare, wave patterns, and other visual artifacts characteristic of water surfaces. The addition of a Farnebäck-based dense optical-flow motion analysis module eliminates some of these false detections, as static areas of the image do not exhibit the characteristic dynamics of human motion. This leads to an increase in precision and F1-score. The integration of the Kalman filter ensures the system’s resistance to short-term visibility losses caused by water surface turbulence, partial immersion, or angle changes. Thanks to the trajectory prediction mechanism, the system maintains a stable track even when the detector temporarily does not detect the object. This reduces the number of misses and increases the recall parameter, as well as improving the F1-score compared to a configuration without tracking. BlazePose introduces semantic analysis of human pose into the method, which allows distinguishing real anthropomorphic objects from noise formations that may have a similar silhouette but do not contain a characteristic skeletal structure. This further reduces the number of false positives, increasing precision and stabilizing the final decisions of the system. BlazePose is particularly effective in cases where only part of the body is visible, or when waves create false contours resembling human arms or legs. The final configuration combines all modules—YOLO12-s detection, motion analysis, tracking, and pose estimation—and demonstrates the highest F1-score (0.945), confirming the synergistic effect of their integration. A slight decrease in FPS from 23 to 21 frames per second on the Raspberry Pi 5 is quite acceptable and does not affect the system’s ability to operate in real time. The ablation results are summarized in Table 6, which shows a gradual increase in precision, recall, and F1-score after adding each subsequent module. This confirms that the hybrid approach significantly improves the efficiency of recognizing people on the water surface in conditions of complex dynamic obstacles and noise.

Table 6.

Ablation of hybrid system components (based on YOLO12-s Combined).

3.4. Stress Testing of UAVs in Real Conditions

In addition to evaluation on the SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, and SynBASe baseline datasets, the proposed hybrid method was tested on real-world video footage collected from UAVs, as described in Section 2.4. The real video sequences used at this stage were not included in the training or validation samples and differed significantly from the available datasets in terms of hydrodynamics, water movement characteristics, and atmospheric conditions. They included fast river currents, heavy rainfall, sudden changes in lighting, and intense glare, which are not represented in SeaDronesSee, SARD, C2A, or SynBASe. As a result, the final experiment evaluates the model’s ability to generalize in conditions that go well beyond the training domain, rather than re-recognizing familiar scenarios. Before applying the hybrid method, the complete processing pipeline was also optimized to work with streaming video data. Overhead between the detection, optical flow, and tracking stages was minimized, and caching of intermediate results was introduced to reduce data access time. An additional important aspect of stress testing was that the detection module at the evaluation stage worked purposefully with only one class—“swimmer/person”. The YOLO12-s model was configured in such a way that during inference it returned only results related to humans. Other types of objects were automatically filtered out thanks to the corresponding confidence thresholds formed during training. This approach made it possible to significantly reduce the number of false detections and prevent non-anthropomorphic objects from being transferred to the optical flow, tracking, and pose estimation modules. In addition, to improve accuracy in complex hydrodynamic conditions, only key frames with pronounced local motion were processed. Frames were selected based on the size of the Farnebäck optical flow field: static or nearly motionless video fragments were discarded, while frames with consistent motion patterns characteristic of partially submerged human bodies were retained for further analysis. This strategy reduced the number of redundant frames, minimized the accumulation of errors, and ensured that tracking and pose estimation were applied only when the video contained truly informative dynamics. The combination of classification restriction to a single target class and motion-oriented selection of key frames significantly improved the system’s ability to distinguish real human presence and movement from wave structures, reflections, and random floating objects that can visually resemble a human silhouette in challenging conditions of river currents and rain. The complete pipeline—YOLO12-s detection, Farnbek optical flow, Kalman filter-based tracking, and BlazePose pose estimation—was deployed on a Raspberry Pi 5 platform and applied to approximately 21,600 annotated frames captured over a fast-flowing river and during heavy rain. The summarized results are shown in Table 7. On this real-world dataset, the hybrid system achieved Precision = 0.94, Recall = 0.91, and F1-score = 0.925, which is only slightly inferior to the results obtained on the SeaDronesSee test subset. The average number of false positives was approximately 5–6 false detections per 1000 frames, and the average performance on the Raspberry Pi 5 remained at ≈21 FPS, which is consistent with the results of the ablation analysis (Table 7).

Table 7.

Performance indicators of the hybrid method on a set of real video data from UAVs.

Qualitative analysis showed that the hybrid approach provides stable tracking of partially submerged people and small objects, even in conditions of strong glare, splashes, and periodic occlusions. Most false positives were caused by white wave crests or bright glare, which locally resembled elongated silhouettes. However, the combination of optical flow and BlazePose pose verification effectively cut off most of these artifacts and prevented them from forming long-term tracks. Throughout all sequences, there were no prolonged target losses or persistent identification errors, indicating the method’s ability to maintain temporal consistency even in significantly more complex hydrodynamic conditions compared to laboratory datasets. The results demonstrate that the performance achieved on the SeaDronesSee reference sets is well transferable to real field conditions, confirming the practical suitability of the proposed system for use in search and rescue operations over water bodies and during floods.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that detecting people on water requires not only accurate object localization, but also a deeper analysis of movement patterns, posture, and temporal dynamics. Traditional detector YOLOv4 showed significant limitations in challenging aquatic environments, especially when obscured by waves, rapid changes in lighting, and distant viewing points. Although later models, such as YOLOv8-s and YOLO11-s, showed significantly better results, they still exhibited noticeable vulnerability to partial immersion and ambiguous silhouettes formed by reflections from the surface. The consistent improvement observed in YOLO12 across all datasets confirms the architectural advantages of this model, particularly its improved feature aggregation and increased robustness to low-contrast scenarios and small targets.

A key finding of this study is the demonstrated advantage of the hybrid method over classical pipelines that use detection alone. By combining YOLO12 with optical flow filtering, Kalman-based temporal stabilization, and position estimation using BlazePose, the proposed system significantly reduces the number of false alarms and missed detections. These findings emphasize that object detection alone is insufficient for real-world search and rescue operations, where the ability to interpret behavior—for example, whether a person is passively floating, actively swimming, or showing signs of distress—is equally important. The hybrid approach enables such interpretation by enriching spatial detections with motion features and skeletal structure analysis, thereby providing a more reliable assessment of the victim’s condition.

The integration of the proposed pipeline into the Raspberry Pi 5 platform further highlights its practical feasibility. Despite severe hardware constraints, the system maintained real-time performance, confirming the suitability of YOLO12 as a lightweight but highly accurate detector for use in unmanned aerial vehicles. However, several challenges remain. Variable environmental conditions, such as turbidity, rain, foam, and rapidly changing water texture, can still cause uncertainty. Wireless communication instability and limited UAV flight duration may limit operational coverage. Furthermore, large-scale generalization requires broader datasets representing inland flooding, river flows, urban inundation areas, and extreme weather conditions, which remain limited in publicly available repositories. Ethical considerations, including privacy, emergency management, and airspace regulation, must also be taken into account when using UAVs in populated disaster areas.

Despite these challenges, the results show that combining modern lightweight detectors with multi-stage improvement pipelines is a promising direction for future UAV-based rescue systems. The results support further research in the areas of environmental adaptation, inter-platform coordination, and joint integration with satellite and ground-based rescue infrastructure.

5. Conclusions

This research presents a hybrid method for detecting and analyzing human presence on water surfaces using images obtained by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). This method combines YOLO12 detection, optical flow motion filtering, Kalman filter-based trajectory stabilization, and BlazePose skeleton estimation, allowing both spatial and behavioral information to be extracted from dynamic water scenes. Experiments conducted on four complementary datasets (SARD, SeaDronesSee, C2A, SynBASe) showed that YOLO12 consistently outperforms previous generations of YOLO in terms of accuracy, reproducibility, and reliability, achieving an intersection mAP@0.5 = 0.95 and the lowest level of false detections and missed persons. The hybrid configuration further improved system performance by reducing critical error types and providing a reliable estimation of human pose and movements in conditions of frequent occlusions and reflections. Real-time tests confirmed that this approach can be applied on low-power embedded hardware such as the Raspberry Pi 5, supporting over 20 frames per second during onboard output. This confirms the practicality of the method for UAV-based search and rescue missions, where rapid decision-making and autonomous tracking are extremely important. The proposed method provides a solid foundation for the future development of integrated technologies to support rescue operations. Potential directions include extending the method to coordinate multiple unmanned aerial vehicles, improving adaptation to indoor flood conditions, introducing thermal sensors for night operations, and developing automated prioritization algorithms for sorting decisions. With further refinements, the hybrid method could serve as the basis for scalable, intelligent, and globally deployed emergency response systems aimed at saving lives in flooded or marine environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and V.M.; methodology, N.B.; software, V.M. and I.A.; validation, I.A., V.I. and V.M.; formal analysis, N.B. and I.K.; investigation, I.A., N.B. and V.M.; resources, I.K.; data curation, I.A. and N.B.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, I.K.; visualization, V.M. and V.I.; supervision, N.B.; project administration, N.B.; funding acquisition, I.K. and N.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The financial support of the Volkswagen Foundation, Grant No 9D167 and Łukasiewicz Research Network—Industrial Research Institute for Automation and Measurements PIAP.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The research was performed in collaboration with the research laboratory “Information Technologies in Learning and Computer Vision Systems” of Kharkiv National University of Radio Electronics and Warsaw University of Technology. During the preparation of this work, the authors used Grammarly 1.2.194 in order to refine the language. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| SARD | Search and Rescue Dataset |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| YOLO | You Only Look Once |

References

- Alwani, A.A.; Chahir, Y.; Goumidi, D.E.; Molina, M.; Jouen, F. 3D-Posture Recognition Using Joint Angle Representation. In Information Processing and Management of Uncertainty in Knowledge-Based Systems; Laurent, A., Strauss, O., Bouchon-Meunier, B., Yager, R.R., Eds.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; Volume 443, pp. 106–115. ISBN 978-3-319-08854-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Min, H.; Peng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z. An Intelligent Real-Time Object Detection System on Drones. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, A.; Pertusa, A.; Gil, P.; Fisher, R.B. Detection of Bodies in Maritime Rescue Operations Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicles with Multispectral Cameras. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 782–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarevsky, V.; Grishchenko, I.; Raveendran, K.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, F.; Grundmann, M. BlazePose: On-Device Real-Time Body Pose Tracking. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.10204. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, D.; Nagori, S.; Mathew, M.; Poddar, D. YOLO-Pose: Enhancing YOLO for Multi Person Pose Estimation Using Object Keypoint Similarity Loss. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.06806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilous, N.V.; Ahekian, I.A.; Kaluhin, V.V. Determination and comparison methods of body positions on stream video. RIC 2023, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, D.; Cecilia, J.M.; Cano, J.-C.; Calafate, C.T. Flood Detection Using Real-Time Image Segmentation from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles on Edge-Computing Platform. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Guo, Y.; Pan, W.; Liu, H.; Xu, B. Human Pose Estimation Based on Lightweight Multi-Scale Coordinate Attention. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.G.D.S.; Teixeira, J.M.X.N.; Teichrieb, V. Analyzing Embedded Pose Estimation Solutions for Human Behaviour Understanding. In Proceedings of the Anais Estendidos do Simpósio de Realidade Virtual e Aumentada (SVR Estendido 2020), Recife, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2020; pp. 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rakova, A.O.; Bilous, N.V. Reference points method for human head movements tracking. RIC 2020, 3, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-C.; Nguyen, T.-H.; Scherer, R.; Le, V.-H. Unified End-to-End YOLOv5-HR-TCM Framework for Automatic 2D/3D Human Pose Estimation for Real-Time Applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Loncomilla, P.; Ruiz-Del-Solar, J. Human Pose Estimation Using Thermal Images. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 35352–35370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]