Abstract

This study explores how research on carbon capture technologies (CCTs) has developed over time and shows how semantic text mining can improve the analysis of technology trajectories. Although CCTs are widely viewed as essential for net-zero transitions, the literature is still scattered across many subthemes, and links between engineering advances, infrastructure deployment, and policy design are often weak. Methods that rely mainly on citations or keyword frequencies tend to overlook contextual meaning and the subtle diffusion of ideas across these strands, making it difficult to reconstruct clear developmental pathways. To address this problem, we ask the following: How do CCT topics change over time? What evolutionary mechanisms drive these transitions? And which themes act as bridges between technical lineages? We first build a curated corpus using a PRISMA-based screening process. We then apply BERTopic, integrating Sentence-BERT embeddings with UMAP, HDBSCAN, and class-based TF-IDF, to identify and label coherent semantic topics. Topic evolution is modeled through a PCC-weighted, top-K filtered network, where cross-year connections are categorized as inheritance, convergence, differentiation, or extinction. These patterns are further interpreted with a Fish-Scale Multiscience mapping to clarify underlying theoretical and disciplinary lineages. Our results point to a two-stage trajectory: an early formation phase followed by a period of rapid expansion. Long-standing research lines persist in amine absorption, membrane separation, and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), while direct air capture emerges later and becomes increasingly stable. Across the full period, five evolutionary mechanisms operate in parallel. We also find that techno-economic assessment, life-cycle and carbon accounting, and regulation–infrastructure coordination serve as key “weak-tie” bridges that connect otherwise separated subfields. Overall, the study reconstructs the core–periphery structure and maturity of CCT research and demonstrates that combining semantic topic modeling with theory-aware mapping complements strong-tie bibliometric approaches and offers a clearer, more transferable framework for understanding technology evolution.

1. Introduction

Understanding how knowledge develops and reorganizes within an intellectual domain has long been central to research on technological change and the sociology of science [1,2,3]. This issue is particularly important for carbon capture technologies (CCTs). The field covers a wide range of approaches—such as post-combustion amine scrubbing, membrane separation, solid sorbents (including zeolites and MOFs), oxy-fuel and pre-combustion routes, and direct air capture (DAC)—and progress in these areas unfolds alongside advances in energy-system integration, infrastructure deployment, and policy design. For net-zero strategies to be credible, we need a clearer picture of how CCT research has evolved: which pathways have become dominant, and which emerging or less-explored options (for example, low-temperature sorbents, hybrid flowsheets, or robust MRV standards) may still hold significant potential.

Yet existing evidence on how CCT knowledge evolves remains fragmented. Prior work has largely relied on citation-based indicators and traditional bibliometric techniques such as co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, co-word networks, and main-path analysis [4,5,6,7]. While these methods are valuable, they are optimized for strong-tie relations (formal citations, frequently co-occurring terms) and struggle to capture (i) contextual semantic meaning, (ii) weak ties and bridging themes across materials–process–system layers, and (iii) the fine-grained mechanisms through which topics emerge, recombine, persist, or fade [8,9]. In practice, influence in CCTs often travels through language, framing, and problem decompositions—for example, reframing “capture” as “carbon removal services” or transferring membrane insights into mixed-matrix designs—without consistently leaving a trace in citation links. As a result, citation-only approaches cannot fully reveal how conceptual and technological trajectories in CCTs are structured and connected.

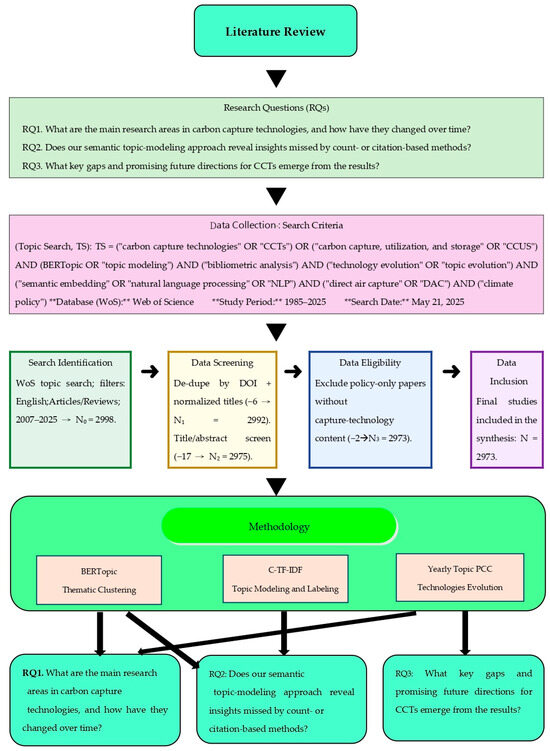

Against this background, we ask three research questions:

- RQ1. What are the main research areas in carbon capture technologies, and how have they changed over time?

- RQ2. Does our semantic topic-modeling approach reveal insights missed by count- or citation-based methods?

- RQ3. What key gaps and promising future directions for CCTs emerge from the results?

To answer these questions, we develop a three-stage analytical framework. First, we construct a transparent and reproducible CCT publication corpus using a PRISMA-guided procedure [10], applying explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria to Web of Science records (English-language articles and reviews) related to CCT materials, processes, and system-level applications. Second, we apply BERTopic to discover, label, and track semantically coherent topics over time. The model integrates Sentence-BERT embeddings with UMAP, HDBSCAN, and class-based TF-IDF to discover, label, and track semantically coherent topics over time [11,12,13,14]. Third, we model temporal evolution using a PCC-based rule set on yearly topic–presence vectors to classify cross-year links into weak, differentiation, convergence, and inheritance types, and interpret the resulting trajectories through established theories of technological life cycles, modularity, and weak ties.

Our empirical analysis focuses on the 2007–2025 evolution of CCTs as a rich testbed: it features multiple competing technological paradigms (solvent/sorbent/membrane/oxy-fuel/DAC), strong interactions between scientific knowledge and deployment constraints, and dense but heterogeneous publication activity. By integrating semantic topic modeling with a theory-aware evolution graph, we map core trajectories, show how weak-tie bridges connect layers of work, and clarify how the framework complements traditional bibliometrics.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Mapping Scientific and Technological Evolution

Understanding how knowledge evolves within technological domains has long been a central concern in the study of scientific and technological change [1,2,3]. In the context of carbon capture technologies (CCTs), this issue is particularly salient because advances in materials and process engineering co-evolve with transport–storage infrastructure, hub-and-cluster configurations, and policy instruments. Existing work on scientific evolution and technology mapping has relied heavily on traditional bibliometric methods and network-based science mapping.

Classical approaches include co-citation analysis, bibliographic coupling, citation mapping, community detection, and algorithmic historiography/main-path analysis to identify influential works and trace canonical trajectories [4,5,6,7,15]. These methods are powerful for uncovering strong-tie structures—formal citation links and stable co-occurrence patterns—and remain foundational tools in scientometrics. However, they have three limitations that are critical for CCTs: (i) they often treat documents and topics as static units, making it difficult to capture fine-grained temporal dynamics; (ii) by focusing on explicit citations and high-frequency terms, they under-represent weak ties, boundary-spanning recombination, and shifts in framing or vocabulary; and (iii) they provide limited visibility into how materials, process, and system-level themes interlock over time across communities. Consequently, classical bibliometrics alone yields an incomplete picture of how CCT knowledge and technological options evolve.

2.2. Bibliometric and Topic Modeling Approaches in CCT-Adjacent Domains

To enrich citation-based mapping, a growing body of work applies text mining and topic modeling to large scientific corpora. Frequency-based techniques such as TF–IDF weighting and Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) remain standard for identifying thematic clusters and constructing topic timelines [16,17,18,19].In energy and technology domains, clustering and topic models have been used to track the growth of research areas, map emerging themes, and examine the evolution of complex fields (e.g., big data, additive manufacturing, technology convergence) [20,21,22,23], building on broader observations about the rapid expansion and fragmentation of scientific output [24]. Dynamic co-word and sparse-representation approaches (e.g., TrendNets) and updated bibliometric syntheses offer more recent examples of structured mapping in adjacent fields [25,26,27].

These studies demonstrate the value of algorithmic mapping for revealing structure in rapidly expanding bodies of literature, but they also exhibit systematic limitations:

Semantic sensitivity: bag-of-words representations treat terms as independent and struggle with technical phraseology and contextual nuance typical of CCT research.

Weak ties and cross-layer linkages: low-frequency but conceptually important connectors—such as techno-economic assessment (TEA), life-cycle assessment (LCA), measurement–reporting–verification (MRV), transport–storage hubs, or liability regimes—may be downweighted despite their structural importance.

Temporal evolution: many applications rely on ex-post overlays (topics mapped separately by period), rather than modeling explicit mechanisms of emergence, persistence, recombination, and decline along continuous trajectories.

As a result, existing publication analyses only partially capture how CCT-related topics form, interact, and reorganize across materials, processes, and system-level designs.

2.3. Semantic Embeddings, BERTopic, and Integrated Framework

Recent advances in distributional and contextual semantics offer tools to address these gaps. Early work on distributional structure and vector-space retrieval laid the foundation for modern representations [8,9,16,17]; more recently, transformer-based models such as BERT provide contextual embeddings that encode word meaning in relation to its surroundings [12]. These representations are well suited to technical domains with evolving vocabularies.

BERTopic builds on this progress by integrating (i) transformer-based embeddings (e.g., BERT) to capture contextual semantics [12], (ii) UMAP for nonlinear dimensionality reduction [13], (iii) HDBSCAN for density-based clustering without pre-specifying the number of topics and with explicit noise handling [14], and (iv) class-based TF–IDF for interpretable topic representations [11]. Empirical applications report that BERTopic can discover coherent, fine-grained topics in varied domains [28,29], improving interpretability over purely neural models while better reflecting semantic structure than classical LDA [18].

Alternative pipelines—such as Dynamic Topic Models [30], Top2Vec [31], Doc2Vec-based clustering [32], and related neural topic models—also leverage distributional semantics but often involve stronger modeling assumptions, less transparent hyperparameters, or reduced interpretability for practitioners. Against this backdrop, BERTopic offers an attractive balance between semantic richness and practical interpretability.

Our methodological contribution builds on these advances but is not limited to applying BERTopic to CCTs. Instead, we develop an integrated, theory-aware framework that is transferable across technological domains.

Semantic topic discovery: use BERTopic to identify coherent, context-sensitive topics in a large, PRISMA-screened CCT corpus [10,11,12,13,14].

PCC-weighted evolution graph: compute cross-year similarities on topic–presence vectors and apply a transparent rule set to classify edges into inheritance, convergence, differentiation, and extinction events, thus encoding explicit evolutionary mechanisms.

Theory-aware mapping: interpret the resulting trajectories using established concepts from technology and innovation studies—dominant designs, modularity, architectural innovation, weak ties, path dependence, and related constructs [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]—linking semantic patterns to recognizable mechanisms of technological change.

This combination goes beyond conventional bibliometrics and standalone topic models by systematically tracing how topics form, branch, recombine, stabilize, or disappear; by making weak-tie and cross-layer connections visible; and by grounding computational patterns in theoretical constructs. The same pipeline can be applied to other complex technological fields (e.g., hydrogen, batteries, CCUS, industrial clusters), thus providing methodological novelty beyond the CCT case.

We adopt HDBSCAN as the clustering component because it can infer the number of clusters endogenously, handle variable-density clusters, and label noise points explicitly, which is important for a heterogeneous, long-horizon CCT corpus. In contrast, alternatives such as k-means, agglomerative clustering, or Gaussian Mixture Models typically require a pre-set number of clusters and make stronger distributional or shape assumptions that are less compatible with our semantic embedding space. For algorithmic details we refer to Campello et al. [14], and all parameters used in our implementation are documented in Section 3.3 to ensure reproducibility.

2.4. Era Segmentation for Carbon Capture Technologies (2007–2014 vs. 2015–2025)

Guided by prior mapping work and observable shifts in the CCT literature, we distinguish two eras for analysis (Table 1). The 2007–2014 period corresponds to the consolidation of core capture routes (amine absorption, membranes, solid sorbents, oxy-fuel/pre-combustion) and foundational process/materials research, where systems and infrastructure topics appear but remain secondary—patterns consistent with early CCT and CCS mapping studies [4,5,20,21,22,23]. From 2015 onward, publications increasingly emphasize system integration, hub-and-cluster design, TEA/LCA/MRV, and DAC, and display stronger coupling between engineering, infrastructure, and governance [24,26,27]. This literature-consistent segmentation provides a substantive baseline for our formation-versus-expansion reading and aligns with our semantic–evolution framework, which is designed to detect changes in topic structure and cross-layer linkages across these two eras.

Table 1.

Two eras of carbon capture technologies.

3. Research Methodology

Figure 1.

Research framework.

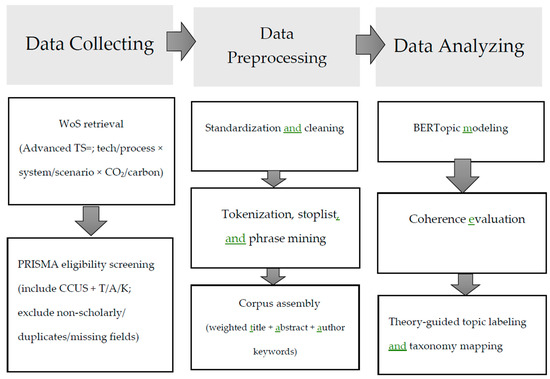

Figure 2.

Research workflow.

(1) PRISMA-guided corpus construction, (2) preprocessing and governance of text fields, (3) BERTopic-based semantic topic modeling, (4) coherence evaluation and theory-aware topic labeling, and (5) temporal evolution analysis using PCC-typed inter-year links. This design aims to be transparent and reproducible while capturing both strong and weak semantic ties in the carbon capture technology (CCT) literature.

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Scope and Protocol

We focus on carbon capture technologies and systems (CC/CCS/CCUS), including post-combustion capture, pre-combustion/oxy-fuel routes, membranes, solid sorbents, direct air capture (DAC), and integrated CCUS systems. Papers must discuss CCTs or system design; papers on climate policy or energy scenarios without substantive capture-technology content are excluded. We restricted our search to English-language articles and reviews. Searches covered 1985–2025 to capture early CCT emergence through recent developments and were executed in May 2025. All search strings and logs were archived to support exact reruns.

3.1.2. Database Choice

All records are retrieved from the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, which offers standardized metadata and stable coverage across relevant journals, enabling consistent bibliometric hygiene and topic modeling.

Table 2.

Core CC/CCUS query blocks used to construct the WoS Topic search for the CCT corpus.

Table 3.

Optional “role-conflict” query blocks, used only for socio-technical sub-analyses and not required for the core CCT topic corpus.

We employed a modular Boolean search in WoS Topic (TS) fields. Table 2 defines the “core CC/CCUS” query blocks (technology/process, systems/scenarios, transport–storage, carbon, and MRV), which were combined with OR/AND operators to construct the main CCT corpus. Table 3 provides an optional “role-conflict” lens (tensions, drivers, outcomes) that was used only when analyzing socio-technical debates and did not change the technical core. These tables document the search design and term blocks derived from iterative pilot searches and domain reading; they are not results tables.

3.1.3. PRISMA Screening

The raw WoS results passed through the following PRISMA stages: Identification (initial hits), Screening (de-duplication by DOI and normalized titles; removal of non-scholarly types and missing fields), Eligibility (manual/title–abstract checks for CCT relevance), and Inclusion. The PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) reports record counts and exclusion reasons at each step. After screening, N0 records form the clean CCT corpus. After PRISMA screening, 2973 records were included in the CCT corpus. During BERTopic modeling, documents assigned to the noise cluster (HDBSCAN label − 1), belonging only to unstable micro-clusters below the minimum topic-size threshold, or associated with topics failing coherence/quality checks were excluded from the evolution graph. The final set of documents with stable topic assignments used for the temporal trajectory analysis therefore comprised 2039 records.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing follows a single scripted pipeline.

- (1)

- Standardization and cleaning.

We normalize Unicode and case; harmonize British/US spellings; unify CO2/CO2/CO2e notations and hyphen/slash variants (e.g., oxy-fuel/oxyfuel); remove records missing titles, abstracts, or author keywords; resolve “early view” vs. final duplicates using DOI with title-similarity checks; and correct obvious metadata anomalies.

- (2)

- Tokenization, stopwords, and phrase handling.

Texts are tokenized and lemmatized while preserving chemical symbols, units, and common process abbreviations (MEA, PZ, PSA, VSA, DAC, BECCS). Stopwords combine standard lists with domain-specific additions (generic engineering terms, boilerplate phrases) that do not aid topic discrimination. We mine bi- and trigrams by PMI/NPMI and frequency, then curate them via whitelist/blacklist (e.g., post_combustion, geological_storage, mixed_matrix_membrane). A thesaurus map merges key variants and abbreviations (MOF/metal–organic framework, amine_absorption/amine_scrubbing, oxy-fuel/oxyfuel).

- (3)

- Modeling field construction.

For each document, titles, abstracts, and author keywords are concatenated into one text field with practical weighting (titles emphasized relative to sparse keyword lists). Multiword expressions are joined with underscores to stabilize downstream modeling. The result is an audited corpus {s_i} that serves as the direct input to BERTopic.

3.3. Semantic Topic Modeling and Labeling

Building on the preprocessed texts, the analysis proceeds in three steps: BERTopic modeling, coherence evaluation, and theory-guided topic labeling.

3.3.1. BERTopic Modeling

We use BERTopic [11] with the following components:

- -

- Embeddings: a sentence-transformers model (BERT-based) [12] to encode each s_i.

- -

- Dimensionality reduction: UMAP [13] with cosine metric, fixed random state, and documented key parameters (n_neighbors, min_dist).

- -

- Clustering: HDBSCAN [14] to identify variable-density clusters without fixing the number of topics; minimum cluster size and minimum samples are reported.

- -

- Topic representation: class-based TF–IDF (c-TF–IDF) to extract top terms and exemplar documents for each topic [11,16,17].

We retain topics above a minimum size and allow post hoc merging where topics show high overlap in centroids and c-TF–IDF terms. All hyperparameters and random seeds are recorded to enable replication.

3.3.2. Coherence Evaluation

Topic quality is evaluated using standard coherence measures (C_V as primary, c_NPMI as secondary) computed on top terms. Topics below a pre-set coherence threshold are inspected and either merged with neighbors or removed when clearly spurious. We run limited grid scans over UMAP/HDBSCAN settings and alternative embedding models to check stability, summarizing robustness via overlap in term sets and document assignments.

3.3.3. Topic Labeling and Taxonomy Mapping

Labeling follows a two-stage, theory-aware procedure:

- -

- Stage 1 (automatic proposals): for each topic, we combine c-TF–IDF terms and exemplar documents to generate candidate labels, matched against a curated CCT vocabulary (amines, membranes, MOFs/porous carbons, DAC, TEA/LCA/MRV, etc.).

- -

- Stage 2 (taxonomy alignment): candidates are reconciled with a hierarchical materials–process–systems–governance taxonomy. Ambiguities (e.g., MOF vs. porous carbon; CCS-general vs. DAC) are resolved using (i) keyword overlap, (ii) centroid similarity, and (iii) contextual reading of exemplars. All decisions are logged.

Final canonical labels and their taxonomy placement are reported in the topic tables. The resulting names and crosswalks are provided in Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix C, Appendix D:

Appendix A. Subfield dictionary (controlled vocabulary).

Appendix B. Auto-proposed labels and matches (log).

Appendix C. Fish-Scale taxonomy (root → field → subfield).

Appendix D. Final canonical names and taxonomy placement (topic ↔ label table).

3.3.4. Implementation and Software Environment

All analyses were implemented in Python 3.10 using open-source libraries. Text preprocessing and data handling were conducted with pandas and numpy, while semantic embeddings were generated using the sentence-transformers library. Topic modeling was performed with BERTopic, which integrates UMAP for dimensionality reduction and HDBSCAN for density-based clustering, and the standard scikit-learn stack was used for auxiliary computations. Visualization and descriptive plots were produced with matplotlib. The entire workflow was executed via scripted pipelines rather than proprietary or black-box interfaces; all key hyperparameters and random seeds for BERTopic, UMAP, HDBSCAN, and the PCC-based evolution graph were specified to support reproducibility. Experiments were run on a typical workstation environment (Python 3.10, multi-core CPU, and sufficient RAM for a ~2039-document corpus), and the observed runtimes are consistent with the expected performance characteristics of these libraries.

3.4. Temporal Technological Evolution

To trace how technologies evolve across years, we convert the corpus prepared in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 into two time-indexed inputs: a topic–year presence matrix and a set of inter-year similarity matrices. The presence matrix is assembled from the wide table in which rows are topic labels and columns are years; duplicate labels are normalized (e.g., hyphen/space variants) and merged with a logical OR so that each topic has a single binary activation vector over time. Inter-year proximity is taken from precomputed Pearson correlation (PCC) matrices whose entries measure the similarity between topic at year and topic at year . This design lets us treat yearly topic states as nodes and PCC-weighted links as hypothesized evolutionary transitions.

Edges are selected by a top-K, thresholded rule. For each active topic in year , we rank its candidates in year by and keep the top match(es) that exceed pre-registered cutoffs. We operationalize event types with three bands: inheritance when , convergence when , and differentiation when ; additionally, we record ‘weak’ ties when 0.30 ≤ < 0.45; such links are not promoted to events; values below an extinction floor (e.g., ) are ignored. Many-to-one patterns of accepted links are interpreted as convergence into a successor, whereas one-to-many patterns indicate differentiation of a predecessor. To prevent over-counting, outgoing links are emitted only in a topic’s first active year (a first-occurrence constraint consistent with the presence matrix), while the presence matrix itself records subsequent activity without forcing additional edges.

4. Results

This section reports the empirical outputs obtained from the workflow in Section 3 (PRISMA-based retrieval, preprocessing, BERTopic modeling, topic labeling, and PCC-typed temporal evolution) and is structured to answer the three research questions: (RQ1) the main research areas and their evolution; (RQ2) the methodological value-added of the semantic/PCC approach; and (RQ3) weak ties, bridging themes, and implications for future CCT pathways.

4.1. Topic Structure and Major Clusters

The PRISMA-guided procedure (Figure 1) identified 2973 CCT-relevant records from the WoS Core Collection (1985–2025). During BERTopic modeling and quality control, records assigned only to the HDBSCAN noise cluster or to unstable micro-topics below the minimum topic-size and coherence thresholds were excluded from the semantic evolution graph. The resulting analytic corpus used for topic modeling and temporal analysis thus comprises 2039 documents; stage-wise counts and exclusion reasons are reported in the PRISMA flow.

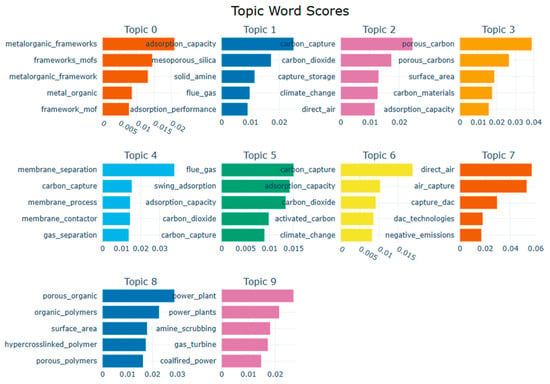

On this corpus, BERTopic discovers 30 coherent topics (IDs 0–29). Table 4 reports the 10 largest topics, which already explain a substantial share of the assigned documents—for example, metal–organic frameworks (Topic 0; 713 docs, 35.0%), amine-based absorption (Topic 1; 176 docs, 8.6%), CCS-general and climate contexts (Topic 2; 155 docs, 7.6%), porous carbons (Topic 3), membrane separation (Topic 4), DAC (Topic 7), POPs (Topic 8), and power-plant amine scrubbing (Topic 9).

Table 4.

Topic summary.

Dictionary-guided labeling and taxonomy alignment (Section 3.3.3) group these topics into three core families (Table 5): Materials (e.g., MOFs, porous carbons, activated carbons, POPs), Processes/Units (amine absorption, membranes, swing adsorption, power-plant scrubbing), and Systems/Scenarios (CCS-general, DAC/system-level contexts). Model-wide coherence scores (C_V = 0.5486; c_NPMI = 0.0847) indicate acceptable semantic consistency for an abstracts-based, multi-decade technical corpus, and low-coherence clusters were merged or removed prior to labeling. Collectively, these results address RQ1 by establishing a transparent, empirically grounded map of the major CCT research lines. Figure 3 visualizes the top c-TF–IDF terms for each of the ten largest topics (0–9), confirming their labels—for example, metalorganic_frameworks for Topic 0, amine_scrubbing for Topic 9, and direct_air/negative_emissions for Topic 7—and highlighting both their distinct technological foci and areas of overlap (Figure 3).

Table 5.

Topic labeling.

Figure 3.

Top distributions across 10 core topics identified by BERTopic.

4.2. Temporal Evolution Mechanisms and Trajectories

To examine how these topics evolve, we construct yearly topic–presence matrices and consecutive-year PCC similarity matrices and apply the rule set of Section 3.4. Only a topic’s first active year emits outgoing edges; cross-year similarities above fixed thresholds are classified as inheritance ( ≥ 0.85), convergence (0.65 ≤ < 0.85), differentiation (0.45 ≤ < 0.65), or weak (0.30 ≤ < 0.45; logged but not promoted), while < 0.30 is treated as extinction/no link. Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 summarize the promoted links, and Table 10 synthesizes the main trajectories.

Table 6.

Era I PCC metrics.

Table 7.

Formation phase (2007–2014).

Table 8.

Era II PCC metrics.

Table 9.

Expansion phase (2015–2025).

Table 10.

Technological trajectories (2007–2025).

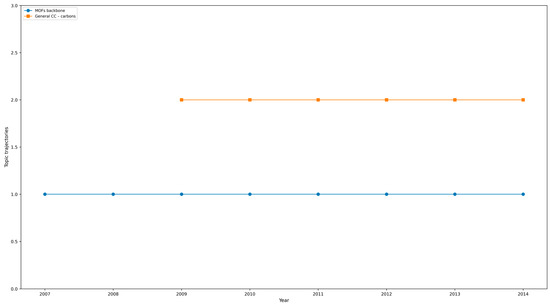

Two eras emerge:

Era I: 2007–2014 (formation):

There is an evolutionary map of the main technological trajectories in the formation phase in Figure 4 (see also Table 7. The vertical position (y-axis) denotes distinct topic lines rather than a numerical scale. The MOF backbone (Trajectory 1; Topic 0, 713 docs, 35.0% of the corpus) and the general-CC–carbon line (Trajectory 2; Topics 2 and 3, 253 docs, 12.4%) appear continuously from their first emergence through 2014, indicating two stable early platforms that anchor subsequent topic differentiation. Around these backbones, several supporting trajectories evolve: Porous carbons (Trajectory 3; Topic 3, 98 docs) form a side material line adjacent to general-CC–carbons; membrane separation and amine-based absorption (Trajectories 4–5; Topics 4 and 1) provide stable but moderate engineering and process baselines; and post-combustion capture (Trajectory 6) remains an episodic, exploratory route that later feeds into broader CCS topics.

Figure 4.

Technological topic evolution (Era I: 2007–2014).

Era II: 2015–2025 (expansion and densification):

An evolutionary map of the dominant technological trajectories in the expansion phase can be seen in Figure 5 and Table 9. The MOFs → utilization/functionalization trajectory (Trajectory 1; Topic 0, 713 docs, 35.0% of the corpus) remains the persistent backbone, but its focus shifts from material discovery to pore/ligand design and process integration. Parallel to this, POP and porous carbons (Trajectories 2–3; Topics 8 and 3) form a dense cluster of carbon-based materials that increasingly differentiate from, and occasionally converge with, the MOF line. Around these materials trajectories, process and engineering routes—amine-based absorption, membrane separation, and DAC (Trajectories 4–6; Topics 1, 4, and 7) provide mature, incrementally optimized baselines at system level, while the general-CC–process and general-CC–carbon continuation lines (Trajectories 7–8; Topics 2 and 3 combined, 253 docs, 12.4%) act as interpretive and bridging hubs linking materials developments to broader carbon-capture system contexts. Together, Table 9 and Figure 5 show that Era II is characterized by diversification and functionalization around a stable MOF backbone, with multiple materials and process trajectories running in parallel and connected through general CCS themes.

Figure 5.

Technological topic evolution (Era II: 2015–2025).

Taken together, the PCC-typed maps indicate a two-stage trajectory: an initial formation era with few strong ties followed by an expansion era characterized by dense presence but relatively sparse strong links—consistent with post-dominant-design, modular, incremental innovation in CCTs. This directly responds to RQ1 on temporal dynamics and inflection patterns.

4.3. Weak Ties, Bridging Themes, and Cross-Layer Integration (RQ3)

The semantic maps highlight several bridging topics that connect materials, processes, and system-level studies via weak or moderate ties:

- Techno-economic assessment (TEA) and cost/learning analyses;

- Life-cycle assessment (LCA) and environmental impact studies;

- MRV (measurement–reporting–verification) standards and carbon accounting;

- Transport–storage hubs, liability, and infrastructure planning;

- Cross-cutting discussions of policy, incentives, and deployment risk.

These themes frequently sit at the interfaces between materials/process topics and CCS/DAC system topics, appearing as differentiation or weak links that nevertheless persist across years. Their positions suggest they function as semantic and organizational bridges, channeling knowledge between engineering design, infrastructure choices, and governance debates.

By making such connectors visible, the framework informs RQ3: it identifies where integration is already emerging and where gaps remain—for example, sparse ties between some advanced materials topics and full-chain deployment studies—thereby pointing to promising directions for coordinated R&D portfolios and policy support.

4.4. Methodological Insights Beyond Citation-Only Views

Finally, the results illustrate how the proposed semantic–PCC framework adds to traditional, citation-based publication analyses, addressing RQ2:

The BERTopic-derived topics capture nuanced technical phraseology and evolving vocabularies that bag-of-words LDA and purely frequency-based co-word maps tend to blur.

The PCC-typed evolution graph encodes explicit mechanisms—newborn, inheritance, convergence, differentiation, and extinction—rather than relying solely on ex-post visual overlays or raw citation counts.

Weak-tie and cross-layer connections (e.g., TEA/LCA/MRV, hub-and-cluster design, DAC–CCS interactions) become empirically traceable even when citation links are sparse, revealing recombination pathways that conventional main-path or co-citation analyses are likely to miss.

These methodological gains are not specific to CCTs: the same pipeline can be applied to other complex technological domains where semantic drift, modular architectures, and cross-disciplinary coupling are central.

The temporal maps indicate a two-stage trajectory: (i) an early formation phase (2007–2014) in which core lines—MOFs, amine absorption, membrane separation, and CCS-general—emerge and stabilize, followed by (ii) a later expansion phase (2015–2025) marked by denser annual activity, process differentiation, and the emergence and consolidation of DAC. These dynamics provide the basis for interpreting technology maturation and portfolio shifts discussed in the next section.

5. Discussion

Using the Section 3.4 rule set—only a topic’s first active year emits outgoing edges; weak (0.30 ≤ r < 0.45, not promoted), differentiation (0.45 ≤ r < 0.65), convergence (0.65 ≤ r < 0.85), and inheritance (r ≥ 0.85)—the 2007–2025 maps reveal a clear two-stage pattern. The 2007–2014 formation era shows the emergence and stabilization of a few core lines with limited strong ties, while the 2015–2025 expansion era exhibits dense yearly activity but relatively sparse promoted edges dominated by differentiation. This is consistent with technology life-cycle and dominant-design perspectives [33,34], modular and architectural innovation logic [35,36], episodic boundary-spanning recombination [37,38,39,40], and rare but decisive inheritance events associated with path dependence and lock-in [2,41,42]. The persistence of system-level DAC is in line with platform logic, complementary assets, and dynamic capabilities required for scale-up [43,44,45]. Methodologically, the map builds on time-aware topic modeling and embedding-based similarity to recover semantically proximate links that citation-only views may miss [11,12,13,30,32] and supports opportunity mapping via proximity-weighted relatedness [23].

5.1. Technological Trajectories of CCTs (Formation vs. Expansion Eras)

This subsection addresses RQ1 by synthesizing the BERTopic–PCC results into an integrated view of how major CCT lines emerge, branch, and stabilize across the formation (2007–2014) and expansion (2015–2025) eras. In the formation phase (2007–2014), MOFs, amine-based absorption, membrane separation, and CCS-general topics emerge as core lines (Table 7). MOFs constitute a large, stable materials platform; amine absorption and membrane separation act as mature engineering routes; general CCS becomes an early hub; porous carbons and post-combustion capture remain smaller, exploratory branches. Only a limited number of inheritance links—most notably within general carbons—satisfy the strict r ≥ 0.85 rule, indicating that much continuity is expressed through persistent topic presence rather than structural rewiring.

In the expansion phase (2015–2025), annual topic presence becomes dense (Table 9). differentiation dominates, signaling modular refinement of established designs; MOFs, POP, and porous carbons co-evolve as material families; amine absorption and membranes remain stable baselines; hybrid configurations and CCS-general topics knit processes and operations together. Convergence events mark boundary-spanning recombination across materials and processes [37,38,39,40], while inheritance events remain rare but identify robust backbones. DAC appears from the mid-2010s and persists, consistent with emerging platform/ecosystem architectures and capability building [43,44,45].

5.2. Role of Weak Ties, Bridging Themes, and Theory-Aware Mapping

Addressing RQ3 (and complementing RQ2), this subsection interprets weak ties, bridging themes, and theory-aware mapping to explain how semantic connectors link materials, processes, systems, and governance. The observed pattern—continuity with multi-point branching—matches the literature on the exploration–exploitation balance [46], modularity and architectural innovation [35,36], and combinatorial search [38]. Frequent differentiation edges indicate component-level tuning within a stable architecture; episodic convergence captures cross-domain recombination; and inheritance marks lock-in and dominant backbones [2,41,42]. Co-evolving clusters of MOFs, POP, and porous carbons fit combinatorial innovation arguments [38], while the thickening of “general—process/methods/operations” topics signals standardization and institutionalization after a dominant design [34].

Our theory-aware semantic mapping foregrounds weak ties and bridging themes that traditional citation clustering may understate: general process/operations topics link multiple material lines; DAC connects back to CCS discourse via shared MRV and infrastructure vocabulary. Using BERTopic with embedding-based similarity and PCC-typed edges aligns with time-aware topic modeling [20-22,25,30] and proximity-weighted diversification analysis [23,39,40], providing an interpretable complement to classical bibliometric mapping.

5.3. Policy and Managerial Implications for CCT Portfolios

Building on the trajectories and bridging themes identified for RQ1 and RQ3, this subsection derives implications for R&D portfolio design, infrastructure planning, and strategic decision-making in CCTs. Given that differentiation dominates (with convergence secondary and inheritance rare), the maps support an “expansion-era” operating principle: emphasize modular, incremental optimization within robust architectures, while using semantic signals to time larger bets.

- (i)

- Portfolio strategy (70/20/10).

A disciplined allocation reflects the following trajectories [47,48,49,50,51,52,53]:

Core, 70%: amine absorption, membrane separation, and general process/operations for near-term retrofit revenue and reliability [47].

Adjacent, 20%: MOFs, POP, and porous carbons co-developed with processes to target cost, footprint, or durability advantages [48].

Bets, 10%: DAC and related system-level options staged demo → commercial → hub/cluster under credible offtakes and policy instruments [43,44,45].

- (ii)

- Type-based triggers.

Convergence (0.65 ≤ r < 0.85, repeated): trigger alliance, JV, or M&A/cross-licensing assessments to internalize complements [39,49].

Differentiation (repeated): justify product-line splits or MVE iterations to capture niche opportunities [50].

Inheritance (r ≥ 0.85): treat as backbone confirmation and scale-up signal, moving to next Stage-Gate with larger capex [51].

Weak/ignored: keep on a watchlist; avoid heavy capital, following real-options discipline [52,53].

- (iii)

- Governance and cadence.

Stage-Gate combined with real options [51,52,53], quarterly portfolio reviews [54], and an MRV-first stance [55] align governance with observed trajectories: standardized module interfaces, dual-sourcing, and explicit kill points (SEC, LCOC, uptime, MRV error) reduce technological and policy risk while preserving flexibility.

Overall, this management playbook exploits architectural stability, leverages convergence nodes as partnering signals, and reads inheritance as a prompt for confident scaling—it is directly grounded in the evolution patterns recovered from our semantic maps.

6. Conclusions

This study addressed three research questions on the evolution of carbon capture technologies (CCTs) using a semantic topic-modeling and temporal mapping framework.

First (RQ1: topic structure and temporal dynamics), we reconstruct a 2007–2025 landscape of 30 coherent topics derived from 2039 WoS articles and reviews. Applying a PCC-typed evolution graph reveals a two-stage trajectory (Table 10). In the formation era (2007–2014), core lines—MOFs, amine-based absorption, membrane separation, and CCS-general—emerged and stabilized with a few strong cross-year ties. In the expansion era (2015–2025), activity became dense while promoted edges remained relatively sparse and dominated by differentiation, an empirical pattern consistent with post-dominant-design, modular, incremental innovation [33,34,35,36]. Nine representative trajectories—covering MOFs, amine absorption, membrane separation, solid adsorption (including POPs and porous carbons), CCS/process overviews, cryogenic separation, oxy-fuel/pre-combustion routes, hybrid flowsheets, and DAC—show how materials, process, and system layers interlock and how DAC consolidates as a persistent system-level pathway increasingly coupled with infrastructure, measurement, and governance arrangements [43,44,45].

Second (RQ2: methodological value-added), the results demonstrate that our integrated framework—BERTopic-based semantic topic discovery, PCC-weighted evolution typing (inheritance, convergence, differentiation, weak ties, extinction), and theory-aware interpretation—provides insights beyond conventional citation-only or frequency-based approaches [4,5,16,17,18,19,20]. Embedding-based topics and PCC-typed edges capture contextual semantics and weak-tie links among materials, processes, and system-level studies; separate continuity from structural change via explicit and reproducible rules; and yield interpretable maps of how technological options branch, recombine, and stabilize over time [11,12,13,14,18,19,20,23,24,25,30]. The pipeline is transparent and replicable (Section 3) and is transferable to other technological domains, offering a generalizable tool for studying knowledge and technology evolution.

Third (RQ3: gaps, bridges, and implications), the semantic maps highlight cross-cutting themes—such as TEA and learning curves, LCA and MRV, hub-and-cluster design, and policy/investment coordination—as recurrent bridges between micro-level technology development and macro-level deployment. Their positions within the evolution graph indicate where integration is emerging and where gaps persist, informing evidence-based portfolio design, infrastructure planning, and policy support for CCTs and DAC [43,44,45].

This framework has several limitations. The corpus is restricted to English-language WoS articles and reviews and uses titles, abstracts, and author keywords; patents, non-English outputs, and full texts may reveal additional patterns that are not captured here. BERTopic- and PCC-based evolution patterns depend on modeling choices (embedding model, UMAP/HDBSCAN parameters, minimum topic size, similarity thresholds); alternative specifications could slightly adjust fine-grained topic boundaries or individual links [11,12,13,14,18,19,20,23,24,25,30]. Unlike traditional main-path and co-citation analyses, our semantic links do not encode formal, directional citations and therefore should be interpreted as measures of semantic proximity rather than causal evidence of intellectual influence [2,4,5,6,7]. We thus position the approach as complementary to established bibliometric methods: strong-tie citation structures remain essential for identifying seminal works and authoritative knowledge flows, while our semantic mapping makes weak ties, cross-layer recombination, and vocabulary shifts visible [37,38,39,40]. Future research should integrate semantic trajectories with citation networks, patent and deployment data, techno-economic assessments, and systematic sensitivity analyses [31,32,37,38] to further validate and refine technology roadmaps for carbon capture and related climate technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, supervision: K.-K.L.; resources, validation, visualization, writing—original draft: C.-W.H.; software, data curation, writing—review and editing: Y.-J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors used OpenAI’s ChatGPT (model GPT-5.1 Thinking, accessed in 2025) to assist with language polishing, text rephrasing, and formatting suggestions. All scientific ideas, study design, data analysis, and final interpretations were conceived, validated, and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the content of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Subfield Dictionary (Controlled Vocabulary)

Table A1.

Controlled vocabulary for carbon-capture technology subfields.

Table A1.

Controlled vocabulary for carbon-capture technology subfields.

| Canonical Name | Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Amine-Based Absorption | Conventional post-combustion solvent capture using amines. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Physical Solvent Absorption | Common in pre-combustion/syngas with high CO2 partial pressure. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Solid Sorbents—Zeolite | Pressure/vacuum swing adsorption using zeolites. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Solid Sorbents—Activated Carbon | PSA/VSA sorption using porous carbons. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Solid Sorbents—MOFs | High surface area crystalline frameworks for CO2 capture. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Solid Sorbents—Alkali/Alkaline Earth | Chemisorbents for high-temperature capture. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Membrane Separation—Polymeric | CO2 -selective polymer membranes. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Membrane Separation—Inorganic | Non-polymeric or hybrid membranes including MMMs. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Cryogenic Separation | Phase-change/condensation based CO2 capture. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Calcium Looping | High-temperature looping using lime/sorbents. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Chemical Looping Combustion | In situ oxygen transfer avoids N2 dilution. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Oxy-fuel Combustion | Combustion in O2/CO2 to yield CO2 -rich flue gas. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Pre-combustion Capture | CO2 removal from H2-rich syngas after water-gas shift. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Post-combustion Capture | Downstream of combustion; low CO2 partial pressure. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Direct Air Capture—Liquid Solvent | DAC using aqueous alkaline solutions, e.g., KOH. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Direct Air Capture—Solid Sorbent | DAC using amine-based solid sorbents. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| BECCS | Bioenergy systems integrated with capture and storage. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Mineral Carbonation—Ex situ | React CO2 with mined minerals/industrial residues. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Mineral Carbonation—In situ | CO2 injected into reactive rock for mineralization. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Biochar Sequestration | Carbon-rich solid applied to soils for storage and co-benefits. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement | Add alkalinity to seawater to enhance CO2 uptake. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Enhanced Rock Weathering | Spread crushed silicates to accelerate CO2 uptake. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| CO2 Hydrate/Clathrate | Form CO2 hydrates for separation under pressure/low temp. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Electrochemical CO2 Capture | Electrochemically driven uptake/release of CO2. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Ionic Liquids for CO2 Capture | Room-temperature ionic liquids and derivatives. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

| Carbonate Looping—Solvent | Hot carbonate solvent systems distinct from amines. | Wikipedia CCS; Capture Map; Verde.ag Top 10 |

Appendix B. Auto-Proposed Labels and Matches (Log)

Table A2.

Auto-proposed topic labels and controlled-vocabulary matches.

Table A2.

Auto-proposed topic labels and controlled-vocabulary matches.

| Topic | Proposed Topic Name | Subfield | Field | Root Discipline | Keywords_List |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amine-Based Absorption | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | [‘adsorption’, ‘capacity’, ‘mesoporous’, ‘silica’, ‘solid’, ‘amine’, ‘flue’, ‘gas’] |

| 9 | Amine-Based Absorption | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Engineering | [‘power’, ‘plant’, ‘power’, ‘plants’, ‘amine’, ‘scrubbing’, ‘gas’, ‘turbine’] |

| 14 | Amine-Based Absorption— aerogel, aerogels, hybrid | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘adsorption’, ‘capacity’, ‘silica’, ‘aerogel’, ‘carbon’, ‘aerogels’, ‘amine’, ‘hybrid’] |

| 24 | Amine-Based Absorption— calcium, looping, sorbent | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘calcium’, ‘looping’, ‘caobased’, ‘sorbents’, ‘amine’, ‘scrubbing’, ‘caobased’, ‘sorbent’] |

| 13 | Amine-Based Absorption—consumption | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Engineering | [‘amine’, ‘scrubbing’, ‘absorption’, ‘rate’, ‘regeneration’, ‘energy’, ‘energy’, ‘consumption’] |

| 22 | Amine-Based Absorption— direct, dac | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘direct’, ‘air’, ‘air’, ‘capture’, ‘capture’, ‘dac’, ‘amine’, ‘sorbents’] |

| 19 | Amine-Based Absorption—steel, slag, water | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘amine’, ‘scrubbing’, ‘packed’, ‘bed’, ‘steel’, ‘slag’, ‘water’, ‘wash’] |

| 7 | Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘direct’, ‘air’, ‘air’, ‘capture’, ‘capture’, ‘dac’, ‘dac’, ‘technologies’] |

| 6 | General Carbon Capture | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘carbon’, ‘capture’, ‘adsorption’, ‘capacity’, ‘carbon’, ‘dioxide’, ‘activated’, ‘carbon’] |

| 29 | General Carbon Capture | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘swing’, ‘adsorption’, ‘temperature’, ‘vacuum’, ‘vacuum’, ‘swing’, ‘carbon’, ‘capture’] |

| 3 | General Carbon Capture— carbons | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | [‘porous’, ‘carbon’, ‘porous’, ‘carbons’, ‘surface’, ‘area’, ‘carbon’, ‘materials’] |

| 25 | General Carbon Capture— coffee, grounds, almond | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | [‘activated’, ‘carbon’, ‘coffee’, ‘grounds’, ‘almond’, ‘shells’, ‘pcacg’, ‘acg’] |

| 20 | General Carbon Capture— Engineered, slow | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | [‘biochar’, ‘carbon’, ‘engineered’, ‘biochar’, ‘slow’, ‘pyrolysis’, ‘pyrolysis’, ‘process’] |

| 15 | General Carbon Capture— liquid, ilmof, composites | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘ionic’, ‘liquids’, ‘ionic’, ‘liquid’, ‘ilmof’, ‘composites’, ‘liquids’, ‘ils’] |

| 16 | General Carbon Capture—mgobased, mgo, alkali | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘mgobased’, ‘adsorbents’, ‘mgo’, ‘adsorbents’, ‘alkali’, ‘metal’, ‘center’, ‘dot’] |

| 23 | General Carbon Capture— molecules, vapor, reduction | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘water’, ‘molecules’, ‘water’, ‘vapor’, ‘capacity’, ‘reduction’, ‘alfumarate’, ‘cauh’] |

| 21 | General Carbon Capture—pressure | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | [‘pressure’, ‘swing’, ‘psa’, ‘process’, ‘swing’, ‘adsorption’, ‘adsorption’, ‘psa’] |

| 10 | General Carbon Capture— reduced, graphite, split | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | [‘graphene’, ‘oxide’, ‘reduced’, ‘graphene’, ‘graphite’, ‘oxide’, ‘split’, ‘pore’] |

| 26 | General Carbon Capture— tsa | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | [‘temperature’, ‘swing’, ‘swing’, ‘adsorption’, ‘adsorption’, ‘tsa’, ‘tsa’, ‘process’] |

| 4 | Membrane Separation | Membrane Separation | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘membrane’, ‘separation’, ‘carbon’, ‘capture’, ‘membrane’, ‘process’, ‘membrane’, ‘contactor’] |

| 11 | Membrane Separation | Membrane Separation | Separation Technologies | Materials Science | [‘mixed’, ‘matrix’, ‘matrix’, ‘membranes’, ‘separation’, ‘performance’, ‘gas’, ‘separation’] |

| 28 | Membrane Separation | Membrane Separation | Separation Technologies | Materials Science | [‘membrane’, ‘separation’, ‘power’, ‘plant’, ‘membrane’, ‘module’, ‘net’, ‘efficiency’] |

| 0 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous Materials | Materials Science | [‘metalorganic’, ‘frameworks’, ‘frameworks’, ‘mofs’, ‘metalorganic’, ‘framework’, ‘metal’, ‘organic’] |

| 5 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘flue’, ‘gas’, ‘swing’, ‘adsorption’, ‘adsorption’, ‘capacity’, ‘carbon’, ‘dioxide’] |

| 2 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)—climate, change | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘carbon’, ‘capture’, ‘carbon’, ‘dioxide’, ‘capture’, ‘storage’, ‘climate’, ‘change’] |

| 27 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)—covalent, cofs, adsorbent | General Carbon Capture | Porous Materials | Materials Science | [‘covalent’, ‘organic’, ‘organic’, ‘frameworks’, ‘frameworks’, ‘cofs’, ‘adsorbent’, ‘performance’] |

| 18 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)—dual, utilization | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | [‘dual’, ‘function’, ‘integrated’, ‘capture’, ‘function’, ‘materials’, ‘capture’, ‘utilization’] |

| 8 | Polymeric Materials | Polymeric Materials | Process Engineering | Materials Science | [‘porous’, ‘organic’, ‘organic’, ‘polymers’, ‘surface’, ‘area’, ‘hypercrosslinked’, ‘polymer’] |

| 12 | Post-Combustion Capture | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | [‘swing’, ‘adsorption’, ‘purity’, ‘recovery’, ‘vpsa’, ‘process’, ‘flue’, ‘gas’] |

| 17 | Post-Combustion Capture | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | [‘silica’, ‘gel’, ‘flue’, ‘gas’, ‘modified’, ‘paint’, ‘adsorption’, ‘capacity’] |

Appendix C. Fish-Scale Taxonomy (Root → Field → Subfield)

Table A3.

Fish-scale taxonomy of topics by root discipline, field, and subfield.

Table A3.

Fish-scale taxonomy of topics by root discipline, field, and subfield.

| Topic | Representative Words | Root Discipline | Field | Subfield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 19_amine_scrubbing_packed_bed_steel_slag_ water_wash | Chemistry | Process Engineering | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 24 | 24_calcium_looping_caobased_sorbents_amine_ scrubbing_caobased_sorbent | Chemistry | Process Engineering | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 9 | 9_power_plant_power_plants_amine_ scrubbing_gas_turbine | Engineering | Process Engineering | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 13 | 13_amine_scrubbing_absorption_rate_ regeneration_energy_energy_consumption | Engineering | Process Engineering | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 14 | 14_adsorption_capacity_silica_aerogel_carbon_ aerogels_amine_hybrid | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 22 | 22_direct_air_air_capture_ capture_dac_amine_sorbents | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 1 | 1_adsorption_capacity_mesoporous_ silica_solid_amine_flue_gas | Materials Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Amine-Based Absorption |

| 7 | 7_direct_air_air_capture_capture_dac_dac_ technologies | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Direct Air Capture (DAC) |

| 10 | 10_graphene_oxide_reduced_graphene_ graphite_oxide_split_pore | Chemistry | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 15 | 15_ionic_liquids_ionic_liquid_ilmof_composites_ liquids_ils | Chemistry | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 16 | 16_mgobased_adsorbents_mgo_adsorbents_ alkali_metal_center_dot | Chemistry | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 23 | 23_water_molecules_water_vapor_capacity_ reduction_alfumarate_cauh | Chemistry | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 2 | 2_carbon_capture_carbon_dioxide_capture_ storage_climate_change | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 3 | 3_porous_carbon_porous_carbons_surface_area_ carbon_materials | Environmental Science | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 6 | 6_carbon_capture_adsorption_capacity_carbon_ dioxide_activated_carbon | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 18 | 18_dual_function_integrated_capture_function_ materials_capture_utilization | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 20 | 20_biochar_carbon_engineered_biochar_slow_ pyrolysis_pyrolysis_process | Environmental Science | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 25 | 25_activated_carbon_coffee_grounds_ almond_shells_pcacg_acg | Environmental Science | Process Engineering | General Carbon Capture |

| 29 | 29_swing_adsorption_temperature_vacuum_ vacuum_swing_carbon_capture | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 21 | 21_pressure_swing_psa_process_swing_ adsorption_adsorption_psa | Materials Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 26 | 26_temperature_swing_swing_adsorption_ adsorption_tsa_tsa_process | Materials Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | General Carbon Capture |

| 27 | 27_covalent_organic_organic_frameworks_ frameworks_cofs_adsorbent_performance | Materials Science | Porous Materials | General Carbon Capture |

| 4 | 4_membrane_separation_carbon_capture_ membrane_process_membrane_contactor | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Membrane Separation |

| 11 | 11_mixed_matrix_matrix_membranes_ separation_performance_gas_separation | Materials Science | Separation Technologies | Membrane Separation |

| 28 | 28_membrane_separation_power_plant_ membrane_module_net_efficiency | Materials Science | Separation Technologies | Membrane Separation |

| 0 | 0_metalorganic_frameworks_frameworks_mofs_metalorganic_framework_metal_ organic | Materials Science | Porous Materials | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) |

| 8 | 8_porous_organic_organic_polymers_ surface_area_hypercrosslinked_polymer | Materials Science | Process Engineering | Polymeric Materials |

| 5 | 5_flue_gas_swing_adsorption_adsorption_ capacity_carbon_dioxide | Environmental Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Post-Combustion Capture |

| 12 | 12_swing_adsorption_purity_recovery_vpsa_ process_flue_gas | Materials Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Post-Combustion Capture |

| 17 | 17_silica_gel_flue_gas_modified_paint_ adsorption_capacity | Materials Science | Carbon Capture Technologies | Post-Combustion Capture |

Appendix D

Table A4.

Topic–subfield matching results (topic IDs, subfields, fields, root disciplines, and match scores).

Table A4.

Topic–subfield matching results (topic IDs, subfields, fields, root disciplines, and match scores).

| Topic | Subfield | Field | Root Discipline | Match Score | Topic Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | 2 | Post-Combustion Capture—adsorption, capacity, mesoporous |

| 9 | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Engineering | 2 | Amine-Based Absorption—power, plant, plants |

| 14 | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 1 | Amine-Based Absorption—adsorption, capacity, silica |

| 24 | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 2 | Amine-Based Absorption—caobased, calcium, looping |

| 13 | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Engineering | 2 | Amine-Based Absorption—energy, absorption, rate |

| 22 | Amine-Based Absorption | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 3 | Direct Air Capture—Solid Sorbent—capture, direct, amine |

| 19 | Amine-Based Absorption | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 2 | Amine-Based Absorption—packed, bed, steel |

| 7 | Direct Air Capture (DAC) | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 4 | Direct Air Capture—Solid Sorbent—capture, direct, technologies |

| 6 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 4 | Solid Sorbents—Activated Carbon—capture, adsorption, capacity |

| 29 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 2 | BECCS—swing, vacuum, adsorption |

| 3 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | 2 | Solid Sorbents—Activated Carbon—porous, carbons, surface |

| 25 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | 2 | Solid Sorbents—Activated Carbon—coffee, grounds, almond |

| 20 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Environmental Science | 4 | Biochar Sequestration—carbon, engineered, slow |

| 15 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 4 | Ionic Liquids for CO2 Capture—liquid, ilmof, composites |

| 16 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 2 | Solid Sorbents—Zeolite—mgobased, mgo, alkali |

| 23 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 0 | Graphene/Carbon-based |

| 21 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | 2 | Electrochemical CO2 Capture—swing, psa, pressure |

| 10 | General Carbon Capture | Process Engineering | Chemistry | 0 | MOFs/Calcium Looping |

| 26 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | 2 | Electrochemical CO2 Capture—swing, tsa, temperature |

| 4 | Membrane Separation | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 4 | Membrane Separation—Polymeric—carbon, capture, process |

| 11 | Membrane Separation | Separation Technologies | Materials Science | 3 | Membrane Separation—Polymeric—matrix, mixed, membranes |

| 28 | Membrane Separation | Separation Technologies | Materials Science | 3 | Membrane Separation—Polymeric—power, plant, module |

| 0 | Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous Materials | Materials Science | 4 | Solid Sorbents—MOFs—metalorganic, mofs, framework |

| 5 | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 2 | Post-Combustion Capture—adsorption, swing, capacity |

| 2 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 5 | BECCS—dioxide, climate, change |

| 27 | General Carbon Capture | Porous Materials | Materials Science | 4 | Solid Sorbents—MOFs—covalent, cofs, adsorbent |

| 18 | General Carbon Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Environmental Science | 2 | Pre-combustion Capture—function, dual, integrated |

| 8 | Polymeric Materials | Process Engineering | Materials Science | 2 | Solid Sorbents—MOFs—porous, polymers, surface |

| 12 | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | 2 | Post-Combustion Capture—swing, adsorption, purity |

| 17 | Post-Combustion Capture | Carbon Capture Technologies | Materials Science | 2 | Post-Combustion Capture—silica, gel, modified |

References

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Dosi, G. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. Res. Policy 1982, 11, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitley, R. The Intellectual and Social Organization of the Sciences; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Small, H. Visualizing science by citation mapping. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999, 50, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; López-Herrera, A.G.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F. Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 62, 1382–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummon, N.P.; Doreian, P. Connectivity in a citation network: The development of DNA theory. Soc. Netw. 1989, 11, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfield, E.; Pudovkin, A.I.; Istomin, V.S. Why do we need algorithmic historiography? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2003, 54, 400–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Z.S. Distributional structure. Word 1954, 10, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachims, T. Text categorization with support vector machines: Learning with many relevant features. In Proceedings of the 10th European Conference on Machine Learning (ECML-98), Chemnitz, Germany, 21–23 April 1998; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; pp. 137–142. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grootendorst, M. BERTopic: Neural topic modeling with a class-based TF–IDF procedure. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.05794. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the NAACL-HLT 2019, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection for Dimension Reduction. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03426. [Google Scholar]

- Campello, R.J.G.B.; Moulavi, D.; Sander, J. Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Proceedings of the PAKDD 2013, Gold Coast, Australia, 14–17 April 2013; Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 7819. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M.E.J. Fast algorithm for detecting community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 69, 066133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; Buckley, C. Term-weighting approaches in automatic text retrieval. Inf. Process. Manag. 1988, 24, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salton, G.; McGill, M.J. Introduction to Modern Information Retrieval; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi, R.; Alfalqi, K. A Survey of Topic Modeling in Text Mining. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2015, 6, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, X. Tracking the Evolution of Big Data Research Using Clustering and Topic Modeling. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 78052–78067. [Google Scholar]

- Song, M.; Suh, Y. Semantic trajectory analysis of emerging technologies. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 1359–1384. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Islam, N.; Shi, Y.; Venkatachalam, K.; Huang, L. The Evolution of Interindustry Technology Linkage Topics and Its Analysis Framework in Three-Dimensional Printing Technology. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 70, 3601–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alstott, J.; Triulzi, G.; Yan, B.; Luo, J. Mapping technology space by normalizing patent networks. Scientometrics 2017, 110, 443–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, P.O.; von Ins, M. The rate of growth in scientific publication and the decline in coverage provided by Science Citation Index. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 575–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsurai, M.; Ono, S. TrendNets: Mapping emerging research trends from dynamic co-word networks via sparse representation. Scientometrics 2019, 121, 1583–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdouline, I.; El Baz, J.; Jebli, F. Revisiting technological entrepreneurship research: An updated bibliometric analysis of the state of art. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 179, 121589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.M.; Borghi, M. Industry 4.0: A bibliometric review of its managerial intellectual structure and potential evolution in the service industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 149, 119752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rey-Moreno, M.; Sánchez-Franco, M.J.; Rey-Tienda, M.S. Examining Transaction-Specific Satisfaction and Trust in Airbnb and Hotels: An Application of Topic Modeling and Deep Learning. Tour. Manag. Stud. 2023, 19, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zankadi, H.; Idrissi, A.; Daoudi, N.; Hilal, I. Identifying Learners’ Topical Interests from Social Media Content to Enrich Their Course Preferences in MOOCs Using Topic Modeling and NLP Techniques. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 5567–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blei, D.M.; Lafferty, J.D. Dynamic topic models. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2006), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 25–29 June 2006; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Angelov, D. Top2Vec: Distributed representations of topics. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.09470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.; Mikolov, T. Distributed representations of sentences and documents. In Proceedings of the ICML 2014, Beijing, China, 21–26 June 2014; pp. 1188–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Abernathy, W.J.; Utterback, J.M. Patterns of industrial innovation. Technol. Rev. 1978, 80, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.; Tushman, M.L. Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 604–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.Y.; Clark, K.B. Design Rules, Volume 1: The Power of Modularity; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R.M.; Clark, K.B. Architectural innovation: The reconfiguration of existing product technologies and the failure of established firms. Adm. Sci. Q. 1990, 35, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkopf, L.; Nerkar, A. Beyond local search: Boundary-spanning, exploration, and impact in the optical disk industry. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L. Recombinant uncertainty in technological search. Manag. Sci. 2001, 47, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacklin, F.; Marxt, C.; Fahrni, F. Coevolutionary cycles of convergence: An extrapolation from the ICT industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2009, 76, 723–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, C.S.; Leker, J. Patent indicators for monitoring convergence—Examples from NFF and ICT. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.A. Clio and the economics of QWERTY. Am. Econ. Rev. 1985, 75, 332–337. [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, W.B. Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical events. Econ. J. 1989, 99, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawer, A.; Cusumano, M.A. Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagji, B.; Tuff, G. Managing your innovation portfolio. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2012, 90, 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich, K.T.; Eppinger, S.D. Product Design and Development, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedoorn, J. Understanding the rationale of strategic technology partnering: Interorganizational modes of cooperation and sectoral differences. Strateg. Manag. J. 1993, 14, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, E. The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses; Crown Business: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, R.G. Stage-gate systems: A new tool for managing new products. Bus. Horiz. 1990, 33, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.K.; Pindyck, R.S. Investment Under Uncertainty; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trigeorgis, L. Real Options: Managerial Flexibility and Strategy in Resource Allocation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R.S.; Norton, D.P. The Balanced Scorecard—Measures That Drive Performance. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1992, 70, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2006.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).