1. Introduction

Recent innovations in GenAI are driving the rapid transformation of human–system interaction (HSI) from static and pre-defined personalization into dynamic and integrated hyperpersonalization that decreases the system complexity of each human interaction. This evolution has reshaped how we interact with systems by making every touchpoint more relevant and insightful [

1]. Given its broad applicability across multiple domains, numerous definitions for personalization have emerged, each varying depending on the focus, implementation methods, intended outcome, and domain contexts. A generalized early definition of personalization [

2] is defined as “whenever something is modified in its configuration or behavior by information about the user, this is personalization”. While personalization can occur in both online and offline contexts, it is generally referred to as custom virtual/online experiences using user data to meet individual needs [

3]. Early implementations of personalization were primarily developed using rule-based systems, collaborative filtering, content-based recommendations, and user segmentation methods [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Recommender systems are foundational for delivering personalization, while collaborative filtering and content-based filtering methodologies are used to predict user preferences and selections. However, it is also observed that these systems typically prioritize system objectives at the expense of a personalized human experience [

10]. These approaches consider the user as a member of a broader segment rather than as a unique individual, also referred to as “segments of one”. Although these techniques have been effective in conventional personalization, more recent HSIs expect highly relevant and individualized interactions that dynamically adapt to preferences and intentions. Thereby, conventional personalization systems face challenges in representing dynamic user behavior, real-time adaptability, and scalability and also tend to perform poorly in situations with limited user data, which is commonly referred to as the “cold start” problem [

11]. Collectively, these limitations can be addressed through the transition from personalization to hyperpersonalization. Hyperpersonalization aims to provide a highly individualized human–system experience by adapting in real time to changing user behaviors, preferences, contexts, and intents. In this paper, we define hyperpersonalization as “the continuous adaptation of human–system interactions that significantly decrease the complexity of information, decision, and action to provide a continuously individualized experience of system use and operation”.

AI-driven personalization has been reported in the recent literature, where advancements in GenAI have accelerated its progression [

12] towards hyperpersonalization. The extensive pretrained knowledge of LLMs offers the ability to generate highly personalized outputs even in cold start scenarios with minimal user input. This capability is enabled through various techniques, such as prompt engineering [

13], in-context learning [

14], retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) [

15], and agentic AI [

16]. These techniques allow the personalization systems to incorporate their pretrained knowledge, retrieved external information, contextual cues, and reasoning and planning capabilities to generate adaptive and relevant experiences. Although these advanced capabilities have significantly improved the personalization capabilities of modern systems, true hyperpersonalization remains unrealized. The primary gap in this regard is a persistent and evolving understanding of the user, which is the capacity of systems to remember, reason, and adapt continuously across sessions, contexts, and roles. Present methods are mainly session-bound and event-driven. Their level of personalization is based on immediate context rather than maintaining a lifelong user representation that captures cognitive and behavioral continuity. Furthermore, most approaches focus on narrow, task-specific applications rather than addressing hyperpersonalization as a framework that adapts in real time based on HSI depth and cognitive intent.

In this paper, we address this gap through the design and development of the Z2H2 framework, which consists of a three-layer architecture operating across three incremental stages. This paper makes the following three contributions: (1) the Z2H2 framework for hyperpersonalization, consisting of three incremental stages named zero-shot, few-shot, and head-shot, (2) the Z2H2 Data Modality Matrix (ZDMM), which formulates the four modalities of data, explicit, implicit, passive, and derived, for each of the three incremental stages, and (3) experimental validation of the framework’s capabilities in an educational setting for progressive HSI across the Z2H2 stages. The rest of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents related work on personalization and hyperpersonalization using AI techniques, followed by

Section 3, which outlines the proposed Z2H2 framework, detailing its layered architecture and stage-by-stage progression.

Section 4 demonstrates the framework in a real-world educational setting, followed by an empirical evaluation in

Section 5 using the OULAD dataset.

Section 6 discusses limitations and ethical considerations and

Section 7 concludes this paper.

2. Related Work

Personalization is a broad and widely studied area that spans numerous domains. In this section, we focus on the evolution of personalization towards hyperpersonalization and explore the existing literature, highlighting the role of AI, especially GenAI, in modern-day hyperpersonalization. Early-stage personalization systems were mainly rule-based or expert-driven. They used if–then rules or domain ontologies to personalize the user experience. The pioneering work of Goldberg et al. [

17] introduced the idea of using collaborative filtering to make predictions about a user’s interest by looking into preferences from many other users, laying the foundation for recommender systems and personalization. In [

18], authors introduce one of the early collaborative filtering systems, named GroupLens, which recommends news articles to users based on articles liked by similar users. However, collaborative filtering had limitations in addressing the cold start problem, and content-based filtering emerged as a solution. It focuses the individual user’s preferences and the content characteristics of items for recommendations. Hybrid methods such as Fab [

19] combined collaborative and content-based features, and clustering-based approaches [

20,

21] were also widely used within this first generation of personalization systems. However, they were mainly bound to specific domains and showed limitations in adaptivity, where the updates were infrequent and not real-time.

With increasing data availability, incorporation of deep learning methodologies allowed personalization systems to capture nonlinear patterns and complex feature interactions. Models such as collaborative deep learning (CDL) [

22] integrated deep autoencoders with matrix factorization to jointly learn item content and user preferences. Moreover, Deep Learning Recommendation Model (DLRM) [

23] combined embedding-based categorical features with dense multilayer perceptrons or large-scale prediction tasks such as ad ranking. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) were also widely explored in the domain [

24,

25] to capture session-based user content evolution over time. This allowed personalization systems to consider the order and the context of the prior events. Although early deep learning methods collectively contributed to the personalization domain, the majority of them mainly focused on optimizing recommendations. These systems often overlooked implicit cognitive signals, temporal intent evolution, and multimodal and cross-platform interactions, which are crucial elements for hyperpersonalization. Subsequent advancements in the domain have introduced a new set of approaches that appear more aligned with the objectives of hyperpersonalization. These include session-based recommenders, sequential user modeling architectures, multi-agent recommender systems, and large language model-driven personalization methods. These approaches extend beyond classical collaborative filtering and neural models by incorporating context relevancy, agentic collaboration, and generative modeling.

Session-based recommender systems such as GRU4Rec treat each session independently, aiming to predict the user’s next action based only on the current session’s behavior without relying on any prior user profile [

26]. Subsequent improvements introduced attention mechanisms to capture the user’s intent within the session more effectively. For example, Neural Attentive Recommendation Machine (NARM) uses an attention encoder to emphasize a user’s main purpose in the session [

27]. These session-based methods excel at adapting to a user’s short-term interests instantly, making them valuable when preferences shift quickly within a session. However, these approaches lack persistent user understanding, which causes them to ignore long-term preferences or past behavior patterns. The adaptation stops when the session ends, limiting any learning from one session to the next. Therefore, their short-term, session-only adaptation and absence of evolving user understanding distinguish them sharply from Z2H2’s persistent, multi-stage hyperpersonalization framework.

Sequential recommender systems extend personalization beyond session-based recommender systems by modeling the sequence of user interactions over time. This enables the systems to capture behavioral signals across multiple sessions rather than restricting personalization to a single interaction window. Transformer-based [

28] architectures such as SASRec introduced self-attention mechanisms to dynamically weight past interactions, effectively modeling both short-range and long-range behavioral patterns [

29]. Building upon this, BERT4Rec used a bidirectional transformer to model sequential data, which allowed these models to encode contextual information from both preceding and succeeding interactions [

30]. These advanced integrations supported models to incorporate capabilities to recognize temporal trends, preference drift, and long-term behavioral structure. Although these systems maintain a form of temporal continuity by encoding multi-session behavior, their personalization mainly focuses on optimizing next-item prediction accuracy. This limits their ability to support richer user representation learning. Sequential recommender systems learn representations that reflect statistical co-occurrence rather than deeper user intent, goals, or identity, and unlike Z2H2, they also do not support progressive personalization stages and apply the same predictive pipeline regardless of whether the user is in a zero-shot, few-shot, or mature head-shot state.

LLM-driven personalization methods highlight the most recent shift within this trajectory. These systems incorporate the generative intelligence of LLMs to either directly generate recommendations or to improve parts of the recommendation pipeline. Chen et al. [

31] argue that LLMs can be utilized as a general-purpose interface for personalization tasks. The abilities, like in-context learning and reasoning, in LLMs help interpret user requests, plan actions, and call external tools or APIs to fulfill user needs. Lyu et al. [

32] introduce LLM-Rec, which is family of prompt templates that enrich the item description with paraphrases before feeding it to the recommender systems. Their work highlights that these enriched prompts benefit from in-context learning and outperform strong content-based baselines on the MovieLens-1M and Recipe datasets, without any additional user fine tuning. Extending prompt-level personalization, Tan et al. [

33] propose PER-PCS, which is a modular parameter-efficient framework where users share small LoRA layers that can be recombined on demand. Furthermore, recent research has also explored improving classic models by injecting LLM-generated knowledge [

34].

LLM-based personalization brings clear advancements towards realizing hyperpersonalization. Their broader pretrained knowledge helps personalization systems to handle zero-shot and few-shot scenarios, which then aligns with the Z2H2 positioning of zero-shot and few-shot hyperpersonalization where the system can start personalizing based on limited HSI data. Furthermore, LLMs introduce a form of cognitive reasoning into personalization where systems are able to infer user intents from context and conduct guided planning tasks. However, without special design, an LLM still struggles to remember a user across sessions due to the absence of evolving user representation learning. Each interaction is stateless unless we explicitly provide conversation history or employ external memory tools through RAG architectures [

35,

36]. This special design requirement motivated the emergence of multi-agent personalization systems. In the first instance within the hyperpersonaization trajectory, systems moved beyond recommendation, ranking, and content suggestion to interpret user intent, plan multi-step tasks, coordinate specialized agents, and execute actions on behalf of the user. Approaches such as MACRec [

37] and Rec4AgentVerse [

38] demonstrate how these multi-agent frameworks overcome limitations with single-model LLM personalization systems by introducing distributed intelligence, delegation, coordination, cross-agent verification, self-reflection, autonomous tool use, and task execution.

Modern-day multi-agent personalization systems stand as the closest class of technologies to true hyperpersonaization. However, their intelligence remains fragmented, as each agent focuses on only a partial and task-specific view of the user rather than contributing towards an evolving user understanding. Their coordination mechanisms are mainly task-driven and lack a progression pathway to gradually build up the required personalization depth across stages. Similar limitations have been highlighted in other real-time, multimodal cognitive systems. For example, authors demonstrate how situation awareness architectures must fuse multimodal data to extract controlling intent and forecast future system states [

39]. This highlights the need for continuous, intent-aware, closed-loop modeling rather than isolated task execution. In contrast to the task-driven approach within multi-agent personalization systems, a hyperpersonalization system aims to be objective-driven, grounded in a lifelong understanding of the user’s evolving representation. Such systems focus on achieving continuity and adaptivity, progressively refining user models by integrating multimodal signals, contextual reasoning, and behavioral evolution. Z2H2 builds on the strengths of generative and agentic intelligence while directly addressing these limitations. Rather than reacting to isolated tasks, Z2H2 formalizes personalization as an ongoing, learning-driven process that strengthens in precision as user interactions accumulate. In the next section, we introduce the Z2H2 framework, which formalizes the evolution of personalization across multiple phases by incorporating GenAI technologies.

3. Methodology: The Proposed Z2H2 Framework

The proposed Z2H2 framework incrementally develops a user profile, beginning with zero-shot assumptions, advancing through few-shot behavioral adaptations, and finally evolving into head-shot cognitive precision. The zero-shot stage refers to the initial interaction stage, where the system relies heavily on limited prior data about a user to deliver personalization without observing any user behavior. The few-shot stage begins once the user starts interacting, which allows the system to adapt personalization using behavioral signals. The head-shot stage is reached when the system has accumulated sufficient data to infer the user’s objective, intent, and decision strategies by enabling deep personalization. The framework employs GenAI technologies across different stages of the hyperpersonalization session to deliver a deeply personalized experience unique to each user. It consists of three core components named the ZDMM, the cognitive layer, and the Hyperpersonalization Layer, which are responsible for data collection, profile creation, and personalized experience generation, respectively. GenAI systems have evolved from pretrained language models into autonomous multi-agent architectures. In our work, we aligned this generative intelligence within the Z2H2 framework, where each stage of the Z2H2 framework is associated with the following GenAI capabilities: reasoning, contextual understanding, and user intent alignment. Specifically, we focused on employing prompt engineering techniques for zero-shot, in-context learning (ICL) for few-shot, and agentic AI and RAG methodologies for head-shot hyperpersonalization.

Figure 1 illustrates the three-layered Z2H2 framework.

3.1. The Z2H2 Data Modality Matrix

The data modality matrix is a foundational layer for the entire Z2H2 framework. Given the dynamic and objective-driven nature of hyperpersonalization, this layer focuses on the systematic integration of diverse data sources. This consists of all potential data points across a user journey, including evolving data streams, shifting objectives, and behavioral changes. Therefore, this evolving data foundation not only supports hyperpersonalization but also drives the framework’s ability to interpret intent and dynamically align its outputs with user goals. The matrix is composed of four data modalities: explicit, implicit, passive, and derived. The description and focus area of each modality are presented in

Table 1.

To further demonstrate how these data modalities are incrementally accumulated and utilized within a hyperpersonalization session, we have aligned them across the zero-shot, few-shot, and head-shot stages. At the zero-shot stage, the focus is on the limited prior data available at the beginning of the session, which mostly consists of information that requires no or minimal user interaction. These early signals help the system deliver an initial personalization based on assumptions and generalizations. In the few-shot stage, the focus shifts to behavioral data, which helps the system to identify evolving preferences and adapt responses accordingly. At this stage, the system uses these signals to refine its understanding of the user to personalize interactions through behavioral alignment. In the head-shot stage, the system consists of sufficient cognitive-level data that reveals the user’s intent, urgency, and objectives. In

Figure 2, we visualize the ZDMM to provide a unified view of the incremental data accumulation and utilization across modalities. The different types of data contributing to each modality and stage are discussed in detail in the following subsections.

3.2. Zero-Shot Stage

In the zero-shot stage of the Z2H2 framework, the ZDMM considers explicit inputs such as sign-up metadata, language preferences, and system-level inputs, as well as passive signals such as device type, browser metadata, location, time, and referrer URLs. Additionally, derived data types such as prebuilt personas, embedding matches using models like CLIP, BERT, or GPT, and knowledge graph-based priors are used to further enhance this early understanding. This diverse set of data collectively forms the groundwork for zero-shot hyperpersonalization in the absence of any user-specific behavioral data. Using the collected data, the system constructs an IP, which is represented as a dense vector

. This serves as the initial representation of the user and is curated by fusing zero-shot data through embedding-based methods.

where

denotes a general embedding function that may be implemented using any suitable encoder architecture. These include simpler metadata-driven encoders or even transformer-based models such as BERT, CLIP, or GPT. Explicit and passive data points are converted into natural language descriptors (e.g., “mobile device on Saturday evening,” and “prefers English content”) and passed through transformer-based encoders to produce embeddings. Derived data, such as persona embeddings, are retrieved by matching the user’s explicit and passive inputs against a bank of prebuilt persona profiles using cosine similarity over existing persona vectors. To further enhance the

, neighborhood aggregation or graph attention methods are used to identify semantically related nodes (regional preferences and related topics) within knowledge graphs, which are then encoded into graph-aware embeddings. Furthermore, social trends are encoded by embedding textual representations of aggregate behaviors (e.g., “most learners in this region prefer short weekend courses”). All these embeddings are then concatenated using embedding fusion techniques to form the final

. Representing IP as an embedding profile ensures memory efficiency, supports vector-based operations and fusion techniques, and also enables effective integration with contemporary GenAI systems.

Once

is constructed, the GenAI-driven hyperpersonalization is initiated by conditioning an LLM on this initial profile using prompt engineering techniques, as shown in (

2). Here,

y is the personalized output, and it can take various forms such as natural language responses, structured content, or even interface configurations.

acts as the system prompt, and it sets the behavior of the model by defining the tone, role, and other constraints.

represents any available user inputs.

is included in the prompt by transforming the embedding vector into a set of semantic descriptions or persona attributes that the LLM can interpret. Thereafter, these descriptors are concatenated with

and

to form the complete prompt. Also,

can be directly integrated with the LLM’s token embedding space by using soft prompts or adapter-based conditioning. This allows the LLM to align the model’s generation with the semantic attributes encoded in

[

40].

Advanced prompting strategies such as persona-based prompting, Chain-of-Thought (CoT) prompting, and contextual prompting can be used at this stage to refine the personalization quality [

41]. Through this zero-shot hyperpersonalization, even first-time users can experience a level of personalization, as the system is capable of using the limited prior data to generate recommendations, personalized content, and dynamic UI layouts, thus effectively addressing the cold start problem.

3.3. Few-Shot Stage

This stage of the Z2H2 framework begins once the user initiates active interactions with the system. At this phase, the ZDMM considers explicit data such as user-provided inputs, including search queries, applied filters, bookmarking, or other preferences. Implicit data mainly emerges from user behavior patterns and consists of clicks, scroll depth, dwell time, and navigation patterns, which indirectly reveal the user’s short-term preferences and intent. Passive data, such as location changes, device state transitions, or fluctuating network conditions, will decide the type of content or level of personalization delivered at this phase. Finally, derived data becomes more relevant as interaction data helps summarize high-level semantic patterns, such as inferred intent behind search queries and other behavior patterns. The integration of these four modalities ensures the transition of the Z2H2 framework from zero-shot assumptions to behavior-driven few-shot hyperpersonalization.

When compared to the zero-shot phase, which is based mainly on limited prior data, the few-shot cognitive layer incrementally constructs a behavioral profile (BP), which can be denoted as the vector form

. It reflects the user’s evolving preferences, interests, and decision-making patterns during the few-shot phase. This helps the system to deliver real-time adaptation of personalization using ICL and embedding fusion techniques. Each user interaction is transformed into a behavioral embedding (

) using a transformer-based encoder, as denoted in (

3), where

is the

user interaction in natural language form. Then, these interaction embeddings are accumulated and fused with the previous BP state using an exponential moving average, as in (

4). Here,

controls the balance between past and the most recent user interactions. To maintain the impact from the context of the zero-shot phase, the BP is combined with the (

) using a variable

, where

, and it balances prior assumptions with new behavioral insights, as depicted in (

5).

denotes the enriched behavior profile, which combines

with the evolving behavior profile

.

In the few-shot phase, the GenAI layer utilizes this enriched vector

as the input to the LLM by embedding it directly or serializing it into semantic descriptors. The prompt is extended by using both the user’s recent interaction history

and the behavioral context vector

to achieve ICL, as shown in (

6). Here,

captures the sequence of user interactions

and corresponding system replies

. In this setting, ICL guides the LLM by embedding the interaction and response pairs as few-shot examples within the prompt. The final prompt can be expressed as shown in (

7), where ⊕ denotes concatenation and

represents the structured encoding of each user interaction and the corresponding response.

transforms the high-dimensional embedding

into a natural language summary or structured descriptors so that the LLM can interpret and condition on the profile semantics.

By including both behavioral examples and serialized profile information in the final LLM prompt, the LLM is capable of inferring evolving user preferences and dynamically adapting its output, such as recommendations, personalized actions, summaries, or even system layouts. This allows the system to deliver adaptive personalization to the end user by continuously refining outputs as the session evolves.

3.4. Head-Shot Stage

The transition into the head-shot stage is based on the accumulation of sufficient data to infer the user’s cognitive intent and long-term objectives. This phase focuses on delivering deep and precise personalization. At this stage, the system already consists of zero-shot and few-shot data, and it collectively uses this data along with head-shot phase data to construct the Cognitive Intent Profile (CIP), represented as

. Explicit data such as feedback, survey responses, goal declarations, or chatbot interactions become available, providing direct insights into the user’s long-term objectives. Implicit data, such as sequence modeling of multi-step user interactions, recurrence patterns, and decision-making behaviors observed over time, indicate user intent. Passive data evolves to include multimodal inputs and tool usage metadata, which help the system understand the user’s environment. Finally, derived data supports the system by providing inferred user urgency levels, decision strategies, and outcomes from agentic AI reasoning to build a more precise and cognitively aligned CIP. The head-shot cognitive layer is responsible for constructing the CIP, represented as

in its vector form. This layer abstracts all head-shot data from the ZDMM and goes beyond behavioral embeddings by incorporating cognitive embeddings, as defined in (

8). In this context,

denotes the

interaction,

represents the head-shot data modalities, and

is an embedding function that transforms user interactions and head-shot data into a cognitive embedding vector. To implement

, the system utilizes transformer-based LLMs for textual data, multimodal encoders such as CLIP for non-textual data, and knowledge graph-based embeddings to capture the relationships between user objectives and domain concepts.

The CIP evolves over time as new cognitive embeddings are observed, and

is updated incrementally, similarly to the BP in the few-shot phase. This update is defined in (

9), where

controls the balance between historical cognitive signals and new head-shot insights. Furthermore, to ensure that all relevant data from the zero-shot and few-shot phases are incorporated into the head-shot phase,

is fused with the enriched BP,

, to form the complete and enriched

, as formally presented in (

10). Here,

controls the weighting between historical behavioral context and inferred cognitive intent. This two-step CIP construction ensures that it captures both historical user behavior patterns from

and other related, real-time information required for accurate cognitive modeling.

Once

is finalized, this complete representation of the user is utilized by the system, along with GenAI capabilities, to generate precise, objective-driven hyperpersonalization for the user, as shown in (

11). The system context,

, provides high-level task instructions to the LLM, while

represents the user interaction history, ensuring that the LLM has a clear understanding of prior interaction steps. Additionally,

consists of serialized natural language descriptors. RAG further contributes real-time external content, which helps enhance the input prompt [

42]. Agentic AI plays a crucial role in this phase by leveraging advanced agentic capabilities that enable hyperpersonalization systems to perform objective-driven decision making.

Advanced reasoning and task decomposition capabilities help the system understand the “why” behind user actions, predict future needs, and identify decision-making strategies, similarly to intent-driven session-based reasoning approaches [

43]. Agentic AI leverages the reasoning capabilities of LLMs to decompose complex personalization tasks into reasoning chains and sub-goals. Frameworks like AutoGPT, LangChain, and LangGraph demonstrate these capabilities through structured agent planning and decision making. Head-shot hyperpersonalization also benefits from multimodal agentic AI capabilities, which enable processing and generation across various modalities such as text, audio, image, and video. Multimodal generative models further allow the system to respond in the appropriate modality, producing images, audio, or videos personalized to the user. In the head-shot phase, agentic AI extends beyond response generation to goal-oriented actions. Tool calling capabilities enable the system to execute external services or APIs to fulfill complex user goals. Furthermore, as hyperpersonalization reaches greater cognitive depth, interactions become increasingly human-like. Socially aware AI agents (avatars or personas) can maintain continuity across conversation turns and adapt their tone and behavior based on the user’s CIP. Additionally, recent advancements such as Model Context Protocol (MPC) can also be incorporated in this layer to further enhance modular tool orchestration and external integrations. Together, these advanced GenAI capabilities will contribute towards a complete system that incrementally improves its understanding of the user to deliver precise, objective-driven, and user-centric hyperpersonalization.

4. Z2H2 in Education

Aligned with the progressive and gradual nature of learning, the Z2H2 framework is demonstrated for the education sector to personalize the student learning experience, as illustrated in

Figure 3. In this example, a learner maintains the objective of finding a suitable course in the GenAI domain that matches their preferences. The referral may come from a search engine, an LLM suggestion, or a UTM-based marketing campaign. The data available at the zero-shot stage is defined by the ZDMM, and it includes explicit inputs such as language preferences or sign-up metadata if available. Passive data related to the device, location, time of access, etc., and derived data such as regional educational trends and prebuilt persona embeddings help the system to establish an initial understanding of the learner without any active input.

The cognitive layer processes these modalities through embedding techniques and similarity checks against prebuilt personas to construct the . For example, if the learner interaction happens on a Saturday night and the learner device is a mobile phone, the system may identify the persona of a “casual weekend learner”. This helps the GenAI layer to deliver personalization even at the zero-shot phase. The personalized outputs may include course recommendations, homepage layout suggestions, onboarding headlines, and more. More technically advanced personalization can be integrated by integrating multimodal capabilities such as personalized banner generation using text-to-image GenAI models (e.g., DALL·E and Stable Diffusion) and personalized chatbots. Once the user starts to interact with the platform, it transitions to the few-shot phase.

In this phase, the data layer captures meaningful behavior inputs such as search queries (GenAI courses), applied filters (short projects), and other engagement inputs such as course previews, scroll depth, or time spent exploring specific courses (opened Course A with 80% scroll depth and skipped Course B). In the cognitive layer, these behavioral interactions are semantically embedded and fused with the to refine the . Thus, the cognitive layer is capable of inferring a more meaningful persona like “beginner GenAI enthusiast with weekend project focus” to match the user’s few-shot behavioral inputs. In the GenAI layer, ICL is used to embed recent interaction and response pairs into the LLM to support context-aware recommendations without any additional training. For example, if a learner previously searched “GenAI course for beginners” () and received recommendations [Course A, B, C] (), this helps the LLM to understand the learner’s evolving preferences and deliver more targeted course suggestions and personalized outputs. The personalized outputs at this phase will be more refined and aligned towards the user’s short-term intent. The current page layout may also be dynamically adapted to prioritize frequently interacted topics or sections that align with the BP.

Once sufficient behavioral data is collected to infer the learner’s long-term intent, the platform transitions into the head-shot phase. At this phase, the platform integrates a full representation of the user along with the historical interaction sequences to construct the CIP (). The CIP considers the learner’s declared goals, final course selections, learning style, urgency level, and commitment data to infer a more accurate cognitive interpretation of the learner. External knowledge is also retrieved through RAG to enhance the context with real-time insights such as trending GenAI case studies. In the GenAI layer, agentic frameworks apply reasoning and tool calling capabilities to decompose learner objectives into subtasks, invoke relevant APIs for tasks such as career path generation and course enrollment, and personalized discount generation. Agentic frameworks such as LangChain, AutoGPT, and LangGraph can be employed in this phase. This final stage delivers a hyperpersonalized experience to the learner, which includes a personalized course interface, one-click enrollment with pre-filled preferences, and a post-enrollment roadmap that includes certification and career path recommendations. At the end of the session, both the user’s goal and the system’s goals have been achieved. The learner finds the most suitable GenAI course aligned with their preferences, and the system successfully enrolls a new learner to the platform, completing this progressive hyperpersonalization session.

Although demonstrated for an educational setting, the proposed Z2H2 framework is equally applicable to any other hyperpersonalization setting across diverse sectors. For example, in industrial settings of human–system interaction, such as factory automation or cyber–physical systems, the framework will be represented as zero-shot for novice operators or repetitive functions, few-shot for intermediate operators and tasks, and head-shot for expert users and operations. The three layers and corresponding components are sector-agnostic and generalizable to any other application setting that involves human–system interaction with increasing complexity.

6. Limitations and Ethical Considerations

Effective hyperpersonalization requires processing each user action instantly, tracking evolving intent, and maintaining a dynamic session state. Meta’s “Scaling User Modeling” work shows that offline embeddings can become stale when user features or intent shift. Therefore, challenges such as scalable infrastructure, multimodal data fusion, session-based context tracking, memory management, and high computational costs must be addressed while developing such systems. While users expect a highly personalized experience within their digital journey, they are greatly concerned about sharing their user data with such digital platforms. This is a popular scenario in the personalization domain known as the personalization–privacy paradox. Hyperpersonalization relies on a large collection of user data and thus raises various privacy and regulatory concerns while being implemented. Regulations like GDPR and the Australian Privacy Act 1988, and federal-level privacy acts such as the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), explicitly define how personal data should be stored and handled [

47,

48]. According to these acts, the systems must provide transparent consent flows that allow users to control and manage their data. Thus, secure data collection, management, encryption, access control, and maintaining visibility are crucial factors to be considered while implementing hyperpersonalization systems. These systems should adopt “privacy by design” principles to address this personalization–privacy paradox and to deliver a trustworthy and personalized experience to the end user. Hyperpersonalization must also consider social concerns. Filter bubbles and echo chambers are risks of excessive personalization. These prevent the user from exposure to different perspectives and often lead to polarized opinions and reduced openness.

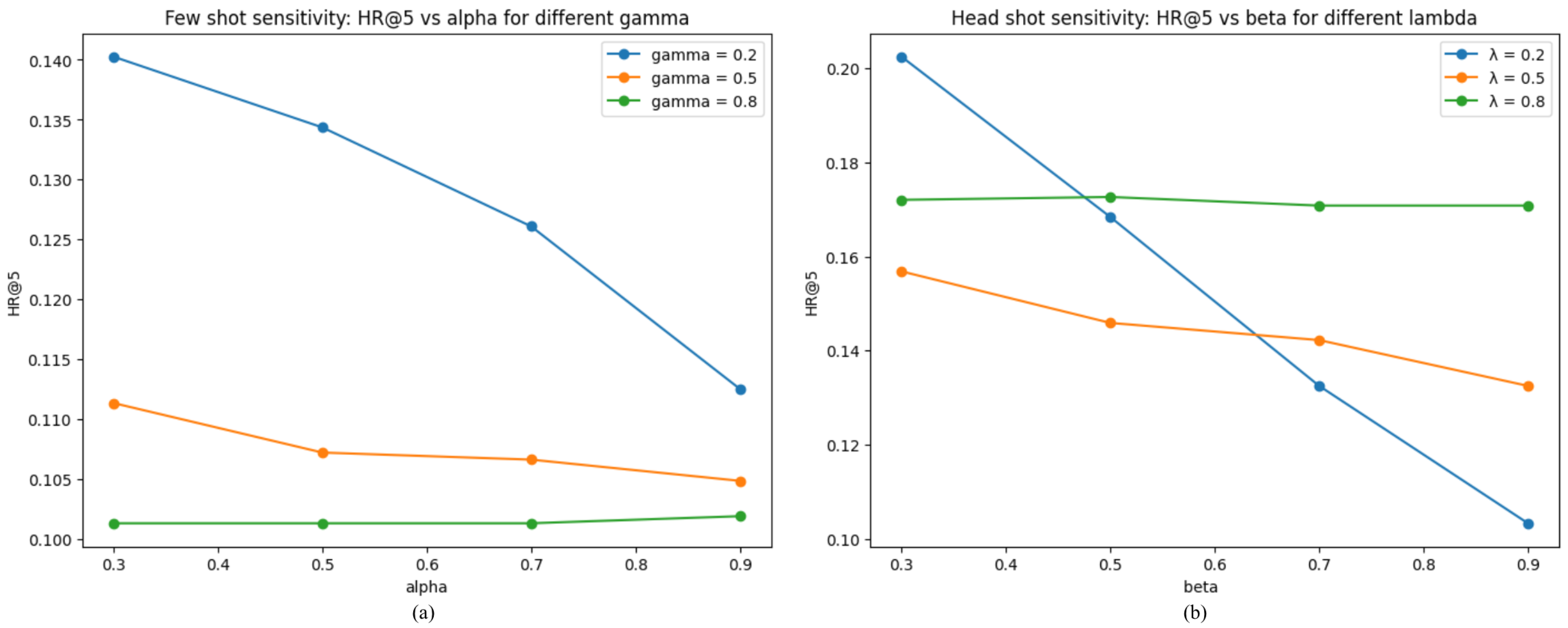

Furthermore, the inclusion of generative intelligence also introduces its own set of challenges and limitations into the hyperpersonalization pipeline. Large-scale pretrained LLMs and LLM-driven agentic systems are prone to hallucinate factual details, propagate hidden biases from their training data, and generate recommendations based on opaque internal reasoning. Within a hyperpersonalization pipeline, these issues can amplify preexisting filter bubbles by over-fitting to inferred preferences or by reinforcing biased correlations present in historical data. Within the Z2H2 architecture, these risks can be mitigated at multiple layers. At the ZDMM layer, explicit, implicit, passive, and derived signals can be validated, cross-checked, and diversified to provide the model with precise structured signals, thereby limiting hallucinated intent. At the cognitive layer, the profile fusion rules provide a natural mechanism for fairness and debiasing. The hyperparameters

,

,

, and

allow the system to detect inconsistent or low-confidence signals at each stage and down-weight them, preventing inferred bias from dominating the evolving user profiles. The contribution of these parameters in the fusion mechanism is examined in detail in

Section 5. At the GenAI layer, grounding mechanisms such as RAG, rule-based guardrails, transparent reasoning chains, and agentic self-verification can help reduce factual as well as faithfulness hallucinations. This layered and staged architecture helps Z2H2 to approach hyperpersonalization as a more balanced and open personalization trajectory, thereby reducing the likelihood of isolating users within filter bubbles and echo chambers. Collectively, these methodologies can be employed to mitigate LLM-based hallucinations as well as system-based limitations such as bias, filter bubbles, and echo chambers.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented the Z2H2 hyperpersonalization framework, consisting of three incremental stages named zero-shot, few-shot, and head-shot that gradually increase the level of hyperpersonalization of the HSI. The framework is further unpacked into a layered system design and the Z2H2 Data Modality Matrix (ZDMM), which systematically maps data types, AI capabilities, and personalization objectives for each stage. Compared to a one-size-fits-all approach, Z2H2 incorporates multiple levels of user engagement and data availability for delivering a scalable, hyperpersonalized experience to the end user. The Z2H2 framework design focuses on the technical, privacy, and ethical limitations that can be listed as some of the major challenges when developing hyperpersonalization systems. From a technical perspective, the layered and staged architecture gives the framework flexibility to act as independent modules. This modularity allows the system components to scale individually and be deployed incrementally. The Z2H2 framework supports multimodal data fusion through its structured data modality matrix, allowing integration of behavioral, contextual, and inferred data streams. On the privacy side, Z2H2 follows a privacy-by-design principle and ensures the user data is processed only with explicit consent, securely stored, and in full compliance with the data protection regulations described in the previous section. The framework promotes transparent consent flows, encrypted storage, and user-controlled data access to allow users to have control over their personal information. Moreover, Z2H2 addresses social concerns due to over-personalization, listed as filter bubbles, echo chambers, and loss of user agency, by incorporating design safeguards that promote content diversity, transparency in decision making, and override capabilities. The agentic AI components in the head-shot phase ensure that users can drive their own experience, which enables a more open, fair, and trustworthy hyperpersonalized experience.

The experimental validation of the Z2H2 framework stages demonstrated that each stage contributes to meaningful improvements. These evaluations confirm the staged progression and illustrate that user representation becomes more precise as more evidence becomes available and relevant across the zero-, few-, and head-shot stages. The experiments only focused on evaluating the representational core of the Z2H2 framework to validate the Z2H2 profile construction process prior to introducing the complexity of generative models for hyperpersonalization delivery. As future work, the generative and agentic components of the Z2H2 framework will be evaluated by integrating RAG, reasoning chains, tool execution, and multimodal agent workflows across different domains. A further research direction is conducting user-centric social studies such as controlled user evaluations to understand the user acceptance level of the personalization produced by the Z2H2 framework and how well the system aligns with real user expectations.