Abstract

The use of simulated environments for the development and validation of Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) has proven to be an effective approach for reducing costs and accelerating the testing process. Simulated environments offer a safe and controlled means for performance analysis and controller parameter adjustment. However, most simulators employed for AGVs and mobile robots rely on kinematic models, which limits the fidelity of the tests. This work introduces a physics-driven Unity framework that leverages the NVIDIA PhysX engine to model AGV dynamics—including payload variation, wheel–ground interactions, and suspension effects—addressing a critical gap in surveyed studies. A factory-floor virtual environment was developed, and a holonomic AGV was implemented with RigidBody and WheelCollider components. PID controllers were tuned via Exhaustive Search and Ziegler–Nichols methods across loads from 0 kg to 100 kg. Exhaustive Search achieved a mean lateral error of just 0.0069 cm and a standard deviation of 1.33 cm at 50 kg—58% lower variability than Ziegler–Nichols. Meanwhile, controller tuning using Ziegler–Nichols required only up to 40 min per load but exhibited up to 84% inter-operator gain variability. Performance was validated on infinity-shaped track, demonstrating Unity’s utility for quantitative performance benchmarking. As contributions, this study (i) presents a novel dynamic AGV simulation framework, (ii) proposes a dual validation workflow combining on-site tuning and systematic optimization, and (iii) integrates an embedded evaluation suite for reproducible control- strategy comparisons.

1. Introduction

Industry routinely employs simulation tools for product development, manufacturing optimization, and control-system design [1,2,3]. In robotics, simulations play a central role in developing new applications, primarily due to modern simulators’ ability to provide high-fidelity physics and realistic world modeling [4]. The Industry 4.0 era has further intensified the use of simulation and virtual environments for testing, training, and validating robotic systems [3,5].

Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) have operated in manufacturing environments for over five decades [6]. Today, they serve internal logistics systems and industrial shop floors, as well as various non-industrial applications [7]. AGV control-system performance ensures safe operation and directly impacts production-line efficiency [1]. Position control represents the core of any AGV system.

Modern simulators reproduce sensor and actuator behavior in far greater detail than numerical control models, enabling more realistic and varied experiments. These virtual environments cut development time and resource costs while offering flexible test conditions that would be impractical to replicate physically. By using simulation tools for control-system design and tuning, engineers can safely evaluate critical scenarios—such as extreme loads or dynamic disturbances—and concurrently run multiple AGV instances, a process that would otherwise demand several physical vehicles and extensive setup.

This paper demonstrates Unity as a simulation platform for developing, tuning, and operating AGV position-control systems. Our research advances beyond traditional simulators that rely solely on kinematic models by using Unity’s dynamic representation capabilities. Although several mobile robot and AGV simulators support physics engines [8,9], the literature indicates they are typically applied only for kinematic modeling [7]. Unity’s native physical components inherently integrate with its physics engine, enabling physically accurate dynamic behavior simulation.

Beyond dynamic modeling, Unity excels in visual fidelity and real-time sensor simulation. Originating from game development, Unity delivers high-quality graphics, scalable environments, and accurate shadow rendering, which can enhance vision-based localization and mapping experiments. Its multithreaded architecture supports real-time 3D LiDAR simulations [10,11,12], while Time-of-Flight cameras benefit from Unity’s precise 3D object modeling and synchronized viewpoints for millimeter-level depth accuracy [13]. Compared to Gazebo’s strong ROS integration—which can limit rendering performance in large-scale LiDAR scenarios—Unity delivers superior scalability and real-time sensor fidelity [14]. Moreover, Unity is freely available to academics under the Education Grant License [15], making it an accessible choice for AGV control strategy analysis under realistic conditions.

While Unity enables accurate physical and visual modeling, effective control remains crucial for ensuring AGV stability and trajectory tracking. PID controllers remain the industry standard, with about 97% of industrial control loops relying on them [16]. These controllers adjust proportional, integral, and derivative gains to minimize tracking errors, yet poor tuning often results in slow dynamic response, higher energy consumption, and potential safety risks [17]. In extreme cases, misconfigured gains can destabilize the system. Despite advances in adaptive and intelligent control, line-following AGVs continue to depend on PID schemes for their simplicity and reliability [7].

This study employs PID tuning strictly as a case study to validate the proposed Unity-based AGV simulation platform, not to advance PID methodology. Two classic tuning approaches—exhaustive search and Ziegler-Nichols—were selected as baseline methods for the following reasons: (i) they are widely adopted in industry for their simplicity and predictable behavior; (ii) they serve as clear reference points to demonstrate Unity’s ability to replicate real-world controller performance under varying payloads and dynamic interactions; and (iii) they establish quantitative performance benchmarks that future research can directly compare when investigating more sophisticated tuning algorithms. Focusing on these baseline methods keeps our emphasis on the physics-based simulation framework rather than PID development.

Commercial line-following AGVs are usually tuned under full-load conditions, since maintaining line adherence at lower loads and slow speeds is rarely problematic. However, physical tuning demands extensive gain adjustments and on-site testing, which can be time-consuming and costly. A virtual environment streamlines this process by allowing rapid evaluation of controller performance across various payload scenarios, and by facilitating feasibility studies for additional sensors—such as load detectors—without hardware modifications.

Tuning AGV controllers on-site often leads to significant delays and costs, requiring weeks of specialized trials and production downtime. Our simulation framework overcomes these challenges by providing a virtual environment for safe parameter exploration, rapid design iterations, and comprehensive performance validation under varied payloads and operating conditions—eliminating risks to personnel and hardware. This capability is particularly valuable in electronics manufacturing, where AGVs navigate narrow aisles with millimeter-level precision to protect sensitive equipment.

Despite growing interest in simulation for AGV development [18,19], most research remains confined to numerical models and light-load vehicles [10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Popular platforms such as Gazebo, ADAMS with MATLAB/Simulink, and Unity support various validation and trajectory-tracking scenarios, yet they typically employ simplified kinematic models. This gap—between basic numerical approaches and fully dynamic simulators—highlights the need for our physics-based Unity framework, which extends simulation capabilities to heavy-load and dynamic conditions.

Most AGV simulation studies rely on kinematic models in environments like Gazebo [27,28,29], ADAMS with MATLAB/Simulink [30], or Unity [31,32], but they rarely use modern physics engines for true dynamic modeling. A systematic review of 92 papers shows only 3 (3.3%) used physics-based simulators according to [7], while 34 (37%) depended solely on numerical simulations, with further examples as [10,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, 61 studies (66.3%) limited themselves to kinematic-only models, and just 21 (22.8%) incorporated dynamic effects—an important omission for AGVs facing variable payloads and changing friction conditions.

Unity-based robotics research has largely emphasized visualization and basic motion control [11,31,33,34,35,36,37]. In contrast, we harness Unity’s NVIDIA PhysX engine to simulate AGV dynamics—capturing load variations, suspension behavior, and realistic wheel-ground interactions. Our systematic review reveals that only 6 of 92 papers (6.5%) explore load variation, 49 (53.3%) lack industrial validation, and just 16 (17.4%) use quantitative performance metrics [7]. By embedding dynamic modeling at the core of our framework, this work aims to overcome the prevailing reliance on numerical and kinematic-only simulations, enabling realistic AGV controller validation under industrial constraints.

We simulate a lightweight, compact AGV tailored to electronics manufacturing, where small-form-factor vehicles must navigate narrow aisles and handle standard light-load boxes [6]. This design optimizes storage density while demanding precise position control to prevent collisions, highlighting the need for fine-tuned control parameters in the virtual environment. We implement AGV dynamics with Unity’s NVIDIA PhysX engine, using RigidBody component, applying forces and torques to replicate realistic robot behavior [12,38,39]. The WheelCollider component was used to simulate mecanum-wheel traction at 45°. It simulates wheel characteristics—friction, damping, and traction—allowing accurate representation of suspension effects and wheel–ground interactions. This setup makes it possible to reproduce critical dynamic conditions, such as varying load masses, without the complexity and cost of physical prototypes. For line following, a virtual sensor array of 100 BoxCollider elements detects the guidance line—offset slightly above the floor—to emulate optical or magnetic sensor behavior.

Considering the gaps identified in [7], this paper makes three distinct contributions. First, a physics-driven Unity framework is introduced, integrating NVIDIA PhysX dynamics to model AGV behavior under varying payloads, wheel–ground interactions, suspension effects, and trajectory conditions. Unlike most existing tools, which apply only kinematic models, the proposed platform captures dynamic responses, addressing the fact that only 3.3% of prior studies employed physics-based simulators.

Second, a dual validation methodology is proposed, consisting of (i) a shop-floor support tool that enables technicians to tune PID gains in situ without halting production, and (ii) an optimization module that performs exhaustive parameter searches to identify performance-optimal gains.

Third, an evaluation suite is embedded into the simulation workflow, which provides quantitative performance benchmarks across multiple load scenarios. The possibility of embedding the computation of different performance indicators addresses the omission in 82.6% of previous works that relied solely on graphical or qualitative analyses. Together, these contributions advance Unity-based AGV research beyond mere visualization and enabling practical on-line tuning, systematic parameter exploration, and reproducible performance comparison for future metaheuristic or adaptive control strategies.

2. Related Works

Simulation tools accelerate the analysis of real-world processes by predicting future states based on underlying models and enabling flexible time-scaling for observations. When properly configured, these tools reduce development time and resource costs.

Platforms used in robotics and control systems simulations include MATLAB [22,25,26,30,40,41], V-REP [33,42], Gazebo [27,28,43], Plant Simulation [44], Tecnomatix [45], ARGoS [46], Unreal Engine [47], and Unity [11,31,33,34,35,36,37,48]. The last two platforms integrate the NVIDIA PhysX physics engine.

Gallo et al. [49] present a hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) evaluation of a Raspberry Pi as the main control hardware of a four-mecanum-wheel mobile robot. Their Unity model integrates kinematic and dynamic representations to evaluate embedded control strategies.

Hoenig et al. [33] develop a mixed-reality tool that merges physical and virtual robots to facilitate flexible control-algorithm development and testing. The article compares the virtual environment in three specific simulation tools: Unity, V-REP, and Gazebo. Similarly, Liu et al. [12] propose a mixed reality simulation using ROS and Unity to investigate the issues faced by mobile delivery robots in the delivery last mile, while Tatievskyi et al. [50] design controllers for double Ackermann steering mobile robots, comparing their performance against standard Ackermann configurations.

Zhang et al. [51] present a fault diagnosis approach for heavy-loaded AGVs based on a digital mirror system. The study proposes a multi-source data enhancement fusion convolutional neural network (ME-CNN) that integrates an improved stacked autoencoder (SAE) for data augmentation and continuous wavelet transform (CWT) for feature extraction. A digital mirror framework is employed for real-time monitoring, allowing synchronization between physical AGVs and their virtual counterparts in Unity. Experimental results demonstrate the method’s effectiveness, achieving 97% classification accuracy in fault diagnosis with sub-500 ms response times, highlighting its potential for predictive maintenance in industrial environments.

Pogo et al. [52] implement a HIL technique using Unity to monitor and control craft beer production. The authors proposed a PID control for temperature regulation and an Inverse Behavior controller for the level regulation. The process was modeled in CAD software and simulated in Unity to evaluate the control hardware externally. Exploring the advantages of virtual environments for control systems simulations, Suárez-Santillán et al. [39] present an optimization of a PID controller applied to an inverted pendulum system. The simulation environment allows instantiating several plants, speeding up the evolutionary enhancement. A virtual reality biphasic separator process is proposed by Flores-Bungacho et al. for training students and engineers in the field of automatic control [53]. The paper implements and compares three control strategies: a PID controller, a numerical controller, and a model predictive controller.

Nguyen et al. [48] integrate an EtherCAT-based control system with Unity for smart warehouse AGV management. The study employs the industrial Ethernet protocol EtherCAT to enable real-time communication between physical AGVs and their virtual counterparts in Unity, facilitating HIL testing and online manipulation. The authors develop a digital-twin architecture that synchronizes AGV motion, sensor feedback, and task scheduling between the virtual environment and actual warehouse hardware. Experimental validation demonstrates that the EtherCAT protocol achieves communication cycle times below 1 ms, enabling precise AGV coordination in multi-vehicle scenarios. The Unity-based visualization supports path planning, collision avoidance, and real-time monitoring, offering a practical framework for integrating virtual prototyping with operational warehouse systems.

Beyond mobile robotics, simulation tools enhance broader industrial applications. Li et al. [36] optimize robotic assembly sequencing in Unity, leveraging dynamic models to reduce development time compared to physical prototyping. Kokkas et al. [54] employ augmented reality in Unity for flexible manufacturing system (FMS) layout planning, overlaying virtual machines onto physical environments to assess spatial configurations. Li et al. [55] implement a digital twin for automated container terminals using 3D Max and Unity, incorporating geometric, physical, and behavioral AGV models for real- time optimization.

Recent studies position Unity as a versatile platform spanning research domains from mobile robotics to manufacturing optimization. The reviewed literature demonstrates Unity’s applicability across four complementary dimensions: (i) general robotic simulation—standalone or integrated with ROS; (ii) AGV-specific implementations, including hardware-in-the-loop integration; (iii) control-system simulation, particularly for PID controllers; and (iv) optimization frameworks supporting systematic parameter tuning. While these studies underscore Unity’s potential for AGV position-control research, they predominantly employ kinematic models or application-specific scenarios, leaving a gap in dynamic modeling that this work addresses.

3. Proposed Simulation Environment

3.1. Vehicle Modeling and Implementation

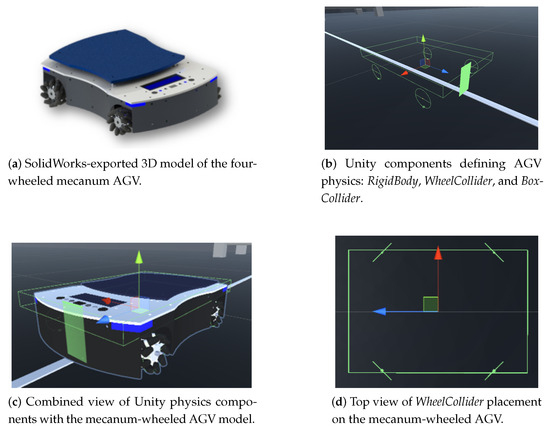

The AGV implemented in the virtual environment is a holonomic platform, featuring four omnidirectional mecanum wheels constrained to behave as a differential-drive system. Such constraints were previously presented by [56] for the real AGV constructed based on the virtual vehicle. The mechanical design and visual modeling were created in SolidWorks 2018, generating an FBX file. Thus, to provide the vehicle with a graphical representation, shown in Figure 1a, it was only necessary to import the model into the simulation software.

Figure 1.

(a–d) show the structural, physical, and spatial configuration of the mecanum-wheeled AGV model developed in SolidWorks and implemented in Unity.

In Unity, GameObject components define both behavior and physical properties. The RigidBody component assigns mass and drag and handles dynamic interactions with forces, gravity, and collisions. Physical boundaries are defined by colliders: BoxCollider for rectangular shapes and WheelCollider for wheels, the latter simulating suspension via spring and damper settings. Figure 1b shows these Unity components, and Figure 1c presents them combined with the 3D AGV model.

Importing the 3D model into Unity occurred in two stages. First, we imported the AGV body and linked it to Unity’s physics via a RigidBody component. Next, we added WheelCollider components and aligned the wheel meshes to those colliders. These adjustments are purely visual—the 3D model does not affect the simulation’s physics.

Although we restricted the AGV to differential-drive motion, we preserved the mecanum wheel layout by positioning each WheelCollider at a 45 degrees angle to match the vehicle’s kinematics (Figure 1d).

Having configured the physical components and wheel layout, the AGV’s kinematic model is derived to compute individual wheel velocities. The inverse-kinematic model of the AGV appears in Equation (1), which relates the desired vehicle velocities along the x- and y-axes and rotation about the z-axis to each wheel’s angular velocity.

where:

- , , , —angular wheel velocities (rad/s)

- —linear velocity along x-axis (m/s)

- —linear velocity along y-axis (m/s)

- —angular velocity about z-axis (rad/s, yaw)

- r—wheel radius ( m)

- L—half the distance between front and rear wheel axes ( m)

- W—half the distance between left and right wheel axes ( m)

To constrain the AGV’s movement to that of a differential drive system, the velocity along the y-axis is set to zero (Equation (2)). As a result, each pair of front and rear mecanum wheels shares the same angular speed, making them act like conventional wheels aligned along the vehicle’s longitudinal axis. Consequently, the AGV exhibits the same motion characteristics as a differential-drive vehicle, despite its omnidirectional wheels.

where:

- —meaning no lateral movement, i.e., robot behaves like a differential drive AGV;

- All other variables as defined by Equation (1).

To implement the AGV’s dynamic model, Unity’s physics components—such as RigidBody, forces, and torques—were used to simulate the robot’s behavior. Rather than directly applying the governing equations, the vehicle’s dynamics were indirectly implemented through Unity’s built-in physics engine, which solver handles inertial and contact interactions. Although this simplifies the model compared to first-principles dynamics, it provides sufficient realism for PID tuning while reducing implementation complexity.

For the robot’s RigidBody component, a mass of was defined. Other physical properties—such as drag, gravity, and moment of inertia—were configured to produce realistic motion. These parameters were calibrated by comparing simulated straight-line acceleration and deceleration times against empirical tests and experimental data.

Each wheel uses a WheelCollider to convert target angular speeds—computed from the inverse-kinematic model (Equation (2))—into forces and torques. Friction and damping coefficients were tuned to reflect measured wheel-surface interactions, thereby ensuring the simulated motion matches real-world wheel slip and traction behavior.

The vehicle mass in the simulation can be increased to represent an additional load, which directly impacts dynamic behavior, influencing acceleration, speed, and response to applied forces.

As the mass increases, the vehicle responds more slowly to forces during acceleration and braking, allowing for the observation of its behavior under loading conditions. In addition, the stopping time increases, since the greater inertia associated with the added mass requires more time to reduce the vehicle’s speed.

When using WheelCollider components, an increase in mass also affects suspension properties such as damping and the frictional interaction between the wheels and the surface.

These effects demonstrate the capability of the simulation environment to reproduce dynamic characteristics while highlighting the importance of configuring parameters to reflect real-world conditions. Mass variations allow the vehicle to be stressed under different scenarios more easily than with a physical prototype.

3.2. Position Control: PID Controller

Equation (3) presents the standard continuous-time form of a PID controller. Because the simulation runs at discrete time steps, the controller is discretized (Equation (4)), where:

- —control output at the discrete time step k;

- —error at time k, representing the lateral displacement of the AGV relative to the line;

- —proportional term, based on the most recent error;

- —integral term, computed from the sum of the last 10 error values;

- —derivative term, representing the difference between the two most recent error values.

A saturation function (Equation (5)) constrains the control output to , preventing unrealistic values that could destabilize the simulation or physical system.

The integral term uses a 10-sample moving window, limiting error accumulation to prevent windup and improve numerical stability. This approach balances controller responsiveness with memory efficiency in real-time simulation.

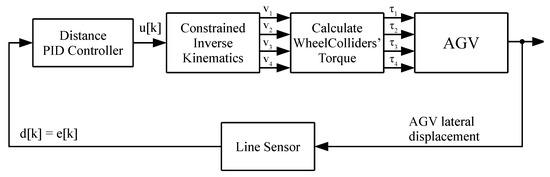

Figure 2 shows the control loop structure. The reference is zero (line center), so the sensor output directly represents position error. This error feeds the PID controller (Equations (4) and (5)), which computes angular velocity via inverse kinematics (Equation (2)). The resulting wheel speeds are converted to torques, updating the AGV’s position. Linear velocity remains constant to maintain steady forward motion. The control loop executes each simulation frame, updating the AGV’s position, lane alignment, and wheel animation based on PID output.

Figure 2.

Block diagram of the PID controller for AGV line-following, showing error feedback and inverse-kinematic mapping to wheel torques.

Controller gains are set manually or via exhaustive search. Manual tuning begins with baseline values , , and known to provide stable line tracking.

3.3. Unity-Based Implementation Framework

3.3.1. Unity Game Engine Overview

Unity is a cross-platform environment originally designed for 2D and 3D game development. However, it is now used for diverse applications in architecture, information management, education, entertainment, medicine, spatial design, simulations, and training [38]. According to Alves and Aronowitz [38], Unity simplifies the complexities of developing games and similar interactive experiences by handling aspects such as graphics rendering, world physics, and compilation. These features make the platform easier for beginners while still allowing the configuration and adaptation of more advanced features as needed. Applications in Unity are developed in two parts: within the Unity Editor and through code, specifically using the C# language, typically written in MonoDevelop or Visual Studio Community [10].

The platform can simulate dynamic environments, and consists of rendering and physics engines, capable of three-dimensional representation as well as the simulation of the characteristics and behaviors of solids, supporting 3D models from software such as 3ds Max, Maya, and CAD [31,39].

Unity enables realistic robotic simulations by replicating sensors, actuators, and the robot’s physical interactions within a virtual environment that supports easy distribution and flexible control and communication [31]. The platform also supports combining simulated worlds with the physical world for more realistic multi-robot simulations, enabling mixed reality (MR) applications, digital twins, and HIL applications [12].

Unity allows configuring system elements by dimensions and properties without explicit mathematical models, facilitating rapid prototyping and on-the-fly reconfiguration. It also automates collision, force, torque, and friction calculations [39].

According to Wijaya et al. [10], compared to other robotic simulators such as Gazebo, Unity has several advantages. One of its main advantages is its enhanced graphics quality, as it was initially developed for gaming applications. Unity also scales more effectively to larger environments compared to ROS-Gazebo, offers higher-quality shadows, achieves equal or better vision-based SLAM performance, and is more capable of real-time LiDAR simulation [10].

Furthermore, Wijaya et al. [10] also state that manually editing scripts to modify robot models through the native graphical interface or using multiple programming languages in Unity is considered easier than editing SDF files in Gazebo for the same purpose.

However, Unity also has some disadvantages compared to other simulators. Although high-quality graphics enhance visualization, they are not the most critical aspect of robotics simulation projects [10]. Since Unity was not specifically designed for simulation, it lacks some features present in other simulators, such as built-in pre-designed sensors. This requires the user to have in-depth knowledge of the sensors to implement them in the environment.

Gazebo offers native ROS integration and lower computational overhead for small/static environments, whereas Unity demands extra tooling and may incur higher costs for commercial deployment [10].

Unity was chosen over traditional robotics simulators such as Gazebo or V-REP due to its combination of high-quality visualization, flexible scripting environment, and ease of importing CAD-based models. These features facilitate rapid prototyping of AGV models and experimental setups without requiring detailed mathematical modeling of every component. Unity also supports interactive, on-the-fly modifications during simulation—functionality that is less straightforward in ROS-Gazebo—providing a more versatile platform for testing control strategies in dynamic virtual industrial environments.

To address potential concerns regarding the physical accuracy of the simulation, preliminary validation tests were conducted. The AGV’s response to simple maneuvers, such as straight-line motion and turns, was compared with analytical predictions based on kinematic and dynamic models. These comparisons indicate that Unity’s physics engine, while primarily designed for gaming, provides sufficiently realistic behavior for the purpose of evaluating AGV control strategies. Future work may include more rigorous validation against high-precision motion capture data and comparison to the real vehicle data.

Overall, Unity stands out as a versatile and powerful tool for robotics simulation, offering high-quality visualization, extensive customization, and integration capabilities. Given these characteristics, Unity was selected as the simulation platform in this study. The implementation was conducted in two versions: 2019.4.16f1 and 2021.3.2f1. Both versions executed the same simulation without affecting performance or implementation.

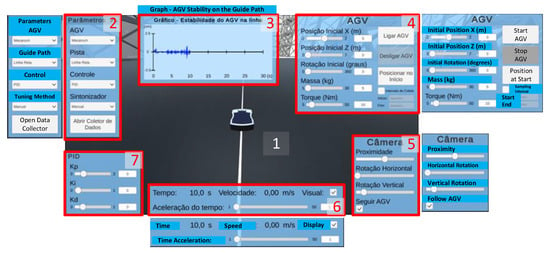

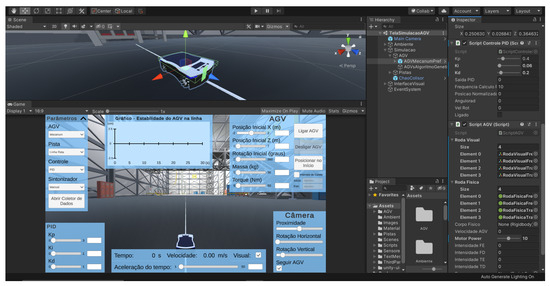

Figure 3 shows the AGV simulation environment with user-accessible controls. The simulation environment is labeled as 1, representing an industrial setting with the AGV and its designated lane. Panel 2 contains the main simulation parameters, encompassing controls for selecting the AGV type (initially, only the AGV described in this study), the lane configuration (a straight-line lane, or an infinity-shaped lane), the controller type (PID only), and the controller tuning method (manual or exhaustive search). The Open Data Collector command opens the window for configuring the export of simulation data.

Figure 3.

Simulation interface showing control panels for AGV type, lane, controller settings, and real-time parameters (panels 1–7). Unity’s XZ plane is horizontal, with Y vertical and as the rotation axis for planar motion.

Panel 3 continuously displays the AGV’s lateral deviation from the lane center in centimeters.

Panel 4 configures AGV parameters—initial position, mass, and wheel torque—and provides controls to start, stop, and reset the vehicle, as well as define the data sampling interval. Panel 5 contains camera controls for static view or AGV-follow mode.

Panel 6 displays the simulation time, along with settings for adjusting its acceleration and graphical visibility. Unchecking ’Display’ hides the graph and boosts speed. Additionally, the panel also shows the AGV’s current speed.

Finally, panel 7 displays the PID controller gain controls. The sliders become available when manual tuning is selected.

The novelty of this study lies in integrating a full-featured Unity-based virtual environment with a customizable AGV platform and sensor system, enabling real-time line-following experiments and PID controller tuning in a flexible industrial layout. Unlike prior Unity robotics work, this framework systematically addresses AGV-specific challenges—load variation, wheel–ground interactions, and suspension dynamics via the NVIDIA PhysX engine—and bridges vehicle modeling, sensor emulation, controller implementation, and virtual industrial scenarios, prioritizing accessibility and adaptability for both research and educational purposes.

3.3.2. Line Sensor and Lane Construction

The virtual line sensor emulates a discrete optical or magnetic sensor array without replicating its exact physics. Typical sensors measure line presence via light or magnetic variations, but our model prioritizes control testing over physical fidelity. Resolution is limited by the grid element size, introducing discretization effects that may affect results when high positional accuracy is required.

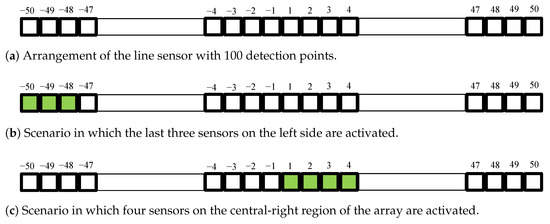

The virtual sensor has a resolution of 100 detection points, similar to infrared sensors that identify the line directly beneath the AGV by distinguishing it from the surrounding floor. To implement this sensor, small parallelepiped-shaped elements were constructed using BoxCollider components and arranged side by side at the location where the real sensor would be installed.

The sensor is positioned perpendicularly and symmetrically along the vehicle’s lateral axis, just ahead of the AGV’s front wheels, as shown in Figure 1b,c. Each element is associated with a trigger script that is activated upon contact with the line, thereby signaling the line’s position relative to the AGV’s frame.

The line track is represented by a single RigidBody-enabled parallelepiped (0.005 m thick, 0.019 m wide) that serves as an active trigger area for the sensor.

Mounted at the AGV front with a 5 cm range, the 100-element array yields 0.5 mm spatial resolution and 0.25 mm error (Figure 4). Each element returns true upon line contact, as illustrated in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

Arrangement of the line sensor with 100 detection points (50 on each side of the AGV), indicating the lane position. Negative values correspond to the left side of the vehicle, while positive values represent the right side.

With 50 sensors on the left and 50 on the right, each sensor is assigned a weight proportional to its distance from the center of the AGV. To determine the lane’s position relative to the center of the vehicle, a weighted average of the active sensors is computed. This average is normalized by 0.02 to yield an error signal in . This value serves as the feedback error signal to the PID controller, where negative values correspond to the AGV being displaced to the right of the lane, and positive values indicate displacement to the left.

Multiplying the normalized error by 25 mm converts it to physical displacement, since 0.5 mm sensor spacing over a 0.025 m half-span yields the 0.02 normalization. If no sensor is activated, an out-of-range value (>1) flags lane loss.

To illustrate the measurement process, consider Figure 4b, in which the last three sensors on the left side are activated—a condition represented by the detection points highlighted in green. The algebraic sum of the sensor, S, value in this case is shown in Equation (6). Considering the number of active sensors, , and the normalization factor of 0.02, the normalized error, , is calculated in Equation (7). Finally, this value is multiplied by 25 mm to obtain the estimated distance to the lane, as shown in Equation (8).

As another example, consider the scenario shown in Figure 4c, where four detection points located near the center of the sensor are activated. Since the line is 19 mm wide and each sensor covers 0.5 mm, fewer than 38 detection points can be simultaneously active only at the edges of the sensor array. Considering that the lane width does not correspond exactly to 38 detection points, up to 40 detection points may be activated. This explains the maximum error of 0.25 mm. In the case illustrated in Figure 4c, which is simplified to only four activated detection points, the sum S, as defined in Equation (9), equals . The normalized error is then calculated as shown in Equation (10), and the distance d is obtained using Equation (11).

While the virtual sensor does not replicate every physical characteristic of a real optical line sensor, it provides a practical approximation for testing control algorithms. The discretization of the sensor and simplified lane geometry introduce minor errors, which are quantified in Equations (8) and (11). The AGV’s kinematic constraints and dynamic response were tuned to reflect the behavior observed in physical prototypes. Therefore, results obtained in the virtual environment can be used to predict trends and optimize controller parameters before conducting real-world experiments, although exact numerical performance may differ due to unmodeled real-world effects such as wheel slip or surface irregularities.

3.4. Virtual Industrial Environment

The simulation environment was built using a model available in Unity that resembles an industrial setting. Initially, no machinery or detailed factory elements were included. As previously explained, the tracks were created to enable collision detection with the line sensor, but their thickness is negligible for the AGV and does not affect its locomotion.

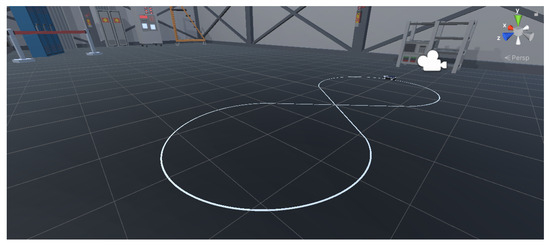

The infinity-shaped track was built from straight segments and two 260° arcs of 1.5 m radius, connected by straight runs to form a closed m loop (Figure 5). A custom script precisely positions each segment. This layout—featuring bidirectional curves, straights, and an intersection—enables comprehensive, continuous evaluation of AGV control performance over varied path geometries.

Figure 5.

Design and implementation of the infinity-shape lane used in the virtual environment.

The straight-line lane consists of a single 30-m segment. It was implemented specifically for the tuning process of the PID controller gains, as will be detailed in the following sections. The simulation camera shows only the AGV and track, hiding debug panels, parameters, and construction interfaces.

A screenshot of the virtual industrial simulation environment developed in Unity is shown in Figure 6. This environment provides a flexible, interactive platform for testing AGV models, controllers, and industrial scenarios via dropdown menus and Unity’s Inspector window, which enables real-time model modifications. The Inspector panel on the far right displays active scripts and parameters, including PID controller gains and AGV configuration settings such as visual and physical wheel components.

Figure 6.

Development interface of the virtual simulation environment developed in Unity, showing real-time configuration of the AGV, and visualization of its trajectory and performance.

4. Case Study: PID Controller Tuning Processes

4.1. Exhaustive Search

The exhaustive-search (ES) method systematically explores the solution space by evaluating all combinations of PID gains (, , and ) across different payload masses. Each combination is simulated, performance metrics are computed, and results are filtered according to predefined acceptance criteria.

The main advantage of ES is its exhaustive coverage of parameter combinations, increasing the likelihood of identifying the optimal parameter set. However, this method imposes a significant computational burden, as the number of required simulations grows exponentially with the number of variables considered and the granularity of the search grid.

The search covers nine discrete payload masses—, , , , , , , , kg—added to the AGV’s fixed base mass of . At each total mass, the AGV navigates a straight-line lane while all PID gain combinations are tested.

The proportional gain varies from to , while the integral and derivative gains vary from to . All parameters are incremented in steps of , resulting in a dense grid of possible configurations that are systematically simulated. These ranges and the step size were determined empirically from preliminary tests that identified gain combinations capable of keeping the AGV on track while balancing resolution and computational cost. Using this grid, the exhaustive search required between 60 and 80 h of simulation on our standard hardware.

Each gain triplet (, , ) undergoes two evaluation stages. First, the AGV must maintain lane following for at least 10 s; triplets that fail this test are discarded. The 10 s sustainment criterion requires that the lateral error remain within ±5 cm of the track centerline, sampled every 10 ms, starting from a fixed initial pose .

In the second stage, valid configurations are assessed quantitatively by computing three lateral-deviation metrics: the mean , standard deviation , and maximum absolute value of the lateral deviation over time . This information is stored along with the corresponding PID parameters and the total vehicle mass for each simulation instance. For each stable triplet, the ES simulation script automatically logs the performance metrics. Instantaneous error samples were discarded to limit data volume. For infinity-track trials, besides those metrics, the simulation stores the AGV’s trajectory.

Equation (12) defines the mean lateral deviation , calculated as the arithmetic average of the individual displacement errors over recorded samples. This metric represents the average deviation of the AGV from the center of the lane throughout the simulation.

Equation (13) defines the standard deviation of the lateral deviation, which quantifies the variability of the AGV’s deviation from the center of the lane. It is computed as the square root of the unbiased sample variance, based on the differences between each recorded error and the mean error , over samples.

Finally, Equation (14) defines the maximum absolute lateral deviation , calculated as the largest absolute error observed among all recorded samples. This metric indicates the greatest deviation of the AGV from the center of the lane during the simulation.

Algorithm 1 presents the pseudocode that describes the procedure adopted to perform the exhaustive search of the PID controller parameters.

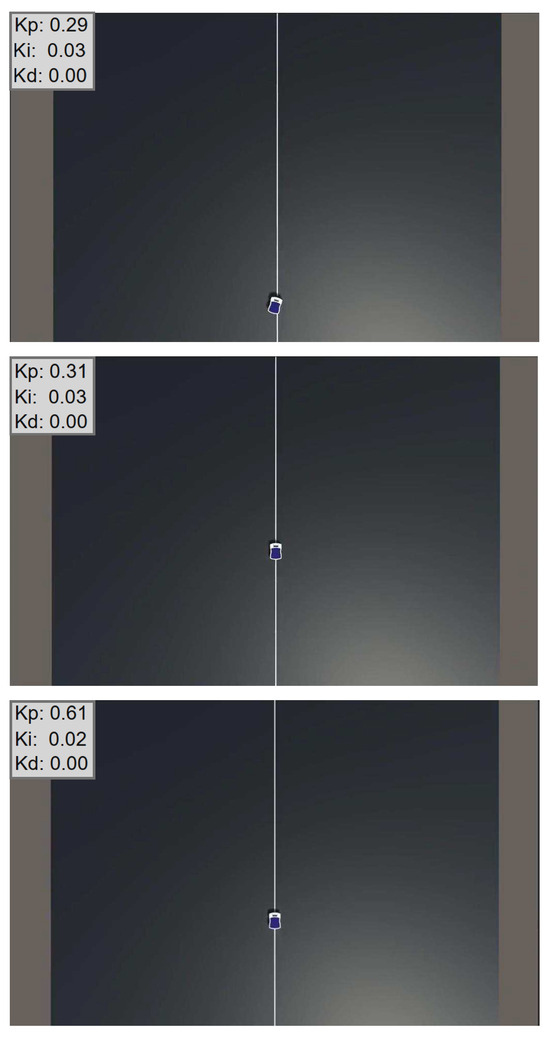

Figure 7 illustrates different instances of the simulation performed during the exhaustive search of the PID controller parameters for the AGV. The evaluated gain values appear in the upper-left corner of each image. Although these visuals are not required for the search itself, they offer qualitative insight into the AGV’s lateral behavior throughout the process. This demonstration highlights Unity’s versatility as a simulation platform for systematically investigating control-parameter spaces and observing system responses under different PID settings and load conditions.

| Algorithm 1 Exhaustive search algorithm for PID tuning with varying load masses. |

|

Figure 7.

Snapshots from Unity simulations during the exhaustive PID-parameter search under varying payloads, with current PID gains shown in the upper-left corner.

4.2. Ziegler-Nichols Tuning Method

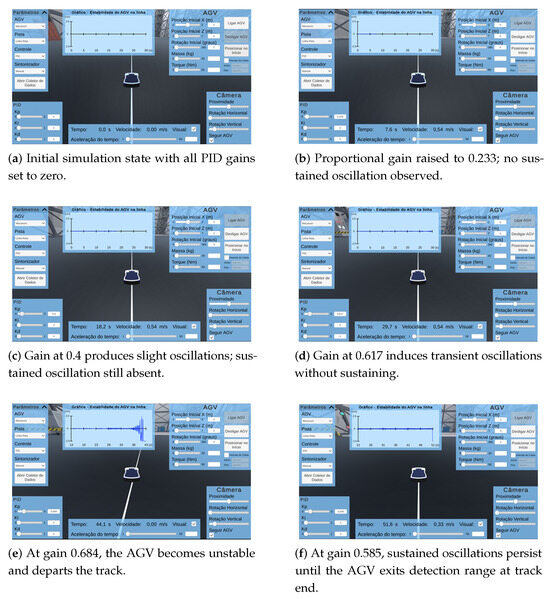

Ziegler–Nichols methods are empirical techniques commonly used to configure PID controllers [57]. The second method relies on varying the proportional gain , while keeping and and observing the system’s response. The goal is to identify a value of that leads the system to a condition of sustained oscillation, known as the stability limit. This value is referred to as the critical gain , and the corresponding oscillation period is called the critical period . Algorithm 2 presents the pseudocode for applying this tuning method.

| Algorithm 2 Ziegler-Nichols second tuning method algorithm. |

|

Once and are identified, the remaining gains are calculated using Ziegler–Nichols empirical formulas. This approach allows satisfactory controller performance without an explicit mathematical model.

Although the method enables fast tuning, its application may lead to suboptimal performance, particularly in terms of disturbance rejection and settling time. This limitation arises because the sustained oscillation criterion considers only the marginal stability of the system, neglecting other important response characteristics, such as overshoot and steady-state error.

This method also highlights Unity’s value as an interactive simulator: operators can adjust PID gains and immediately observe AGV responses, facilitating hands-on learning and controller configuration.

To simulate the AGV using this tuning method, the parameters , , and are first set to zero. Then, the user increments until sustained oscillations appear. This process is repeated for each load condition to identify .

Two users executed the tuning process using distinct -scanning strategies:

- Linear search: the value of is gradually increased from zero using a fixed step size until the system reaches the sustained oscillation condition;

- Binary search: a range is defined, and the value of is adjusted using the bisection method until convergence to the critical gain.

After determining and , the PID gains are calculated using classical Ziegler–Nichols formulas based on controller type (P, PI, or PID).

Critical gain was identified via manual peak detection in Unity’s debug output, and critical period was computed as the average interval between consecutive peaks over five cycles. Each user required 20–40 min per load to converge on , reflecting realistic variability in operator experience. Figure 8 illustrates a sequence of simulation snapshots demonstrating the application of the Ziegler–Nichols tuning method in the Unity virtual environment.

Figure 8.

Snapshots from Unity simulations demonstrating the Ziegler–Nichols PID-tuning workflow for AGV position control under varying payloads.

Tuning was performed across six discrete payloads—, , , , , kg—added to the AGV’s base mass of .

4.3. Experimental Setup

This section describes the experiments conducted to evaluate different PID controller tuning strategies applied to an AGV simulated in a virtual environment on two workstations (Intel Core i7-7700HQ @ 2.80 GHz processor, 16 GB DDR4 2400 MHz RAM, NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050-4GB GDDR5 GPU, Windows 10 OS and Intel Core i5-8250U CPU @ 1.60 GHz processor, 8 GB DDR4 2400 MHz RAM, NVIDIA GeForce 930MX 2 GB GDDR5 GPU, Windows 10 OS) with a fixed time step of s and default PhysX solver settings. The experiments were organized into two main stages: the controller tuning stage and the evaluation stage, which assessed the performance of the tuned controllers under varying operating conditions. Each trial on the infinity-shaped track consisted of a single complete lap. Since no noise sources were introduced and preliminary checks confirmed negligible variability, each gain configuration was tested only once per load condition.

In the first approach, an exhaustive search was performed to identify combinations of gains , , and that maintained lane following for at least 10 s. Each combination within the defined parameter ranges was tested on a straight-line lane, and only those resulting in stable behavior were retained.

To simulate different system operating points, the mass of the load transported by the AGV was varied. For each stable combination, the mean, standard deviation, and maximum value of the lateral error with respect to the guide track were recorded. The objective of this experiment was to obtain, for each load condition, a set of gain values that ensured system stability.

The second experiment involved applying the second Ziegler–Nichols empirical tuning method, based on identifying the critical proportional gain and the corresponding oscillation period , both obtained from sustained oscillations. The parameters and were initially set to zero, and was gradually adjusted until the AGV response reached the marginal stability condition.

Two operators—both Computer Engineering students with basic control-systems knowledge and prior Unity experience—independently applied the Ziegler–Nichols tuning procedure to assess user variability. Each operator performed one tuning trial per payload, visually judging the onset of sustained oscillations. Final PID gains were then computed using classical Ziegler–Nichols formulas. This experiment evaluated Unity’s utility as an interactive tuning platform and quantified the impact of subjective judgment on empirical controller tuning.

After determining the PID gains using both strategies, the controllers were tested on a infinity-shaped lane, under the same load conditions used during tuning. The goal was to analyze controller performance in a more complex scenario than the straight track, considering metrics such as position error and the duration of stable operation. The evaluation recorded gain values, payload mass, and motor torque limits. Motor torque was limited to 5 Nm.

To further assess controller robustness, simulations were also performed under conditions different from those used during tuning. Each controller was tested with its original load value plus three distinct payload variations. This setup enabled analysis of how changes in the transported mass affect system performance, with the aim of evaluating the controller’s ability to handle variations in the system’s dynamic behavior.

The simulation results underscore the limitations of fixed-gain PID controllers when operating under variable payloads, suggesting the need for adaptive or gain-scheduled control strategies in AGVs with dynamic loads. We emphasize that Unity was used primarily as a development and simulation platform, not as an optimizer for AGV performance. Both exhaustive-search and Ziegler–Nichols methods were applied to demonstrate how Unity enables systematic exploration of controller-parameter spaces, revealing how load variations affect controller performance. This case study illustrates Unity’s potential for in-depth analysis and testing of control strategies in a fully virtual environment.

Likewise, the Ziegler–Nichols tuning procedure showcases Unity’s value as an interactive support tool that allows operators to adjust controller parameters and visualize AGV responses in real time. Controlled experiments with multiple operators reveal how Unity facilitates both theoretical learning and hands-on tuning, bridging the gap between design methods and practical implementation. Overall, this case study underscores Unity’s flexibility for developing, testing, and understanding control strategies in a virtual environment, emphasizing its role as a learning and experimentation platform rather than as a definitive PID tuning solution.

5. Results and Discussions

The comparative study of exhaustive search and Ziegler–Nichols tuning demonstrates that Unity is an effective platform for validating AGV control systems. Exhaustive search yields more consistent performance and lower sensitivity to load variations across all tested conditions.

Although we compare PID tuning methods, the main objective is to showcase Unity as a simulation environment for control systems. It enables testing different controllers under varying load conditions, collecting detailed performance metrics, and analyzing complex trajectories, providing a safe, repeatable, and visually verifiable tool. Our results confirm its ability to provide performance, stability, and sensitivity data, underscoring Unity’s value for validation and optimization before physical testing.

From an Industry 4.0 perspective, Unity offers multiple integration pathways. First, as a digital twin for operator training, it lets technicians explore AGV behavior without halting production. Second, the shop-floor support module interfaces directly with PLCs via EtherCAT or Modbus, allowing on-site tuning and validation before controller deployment. Third, simulation results export to standard formats (e.g., OPC UA, MTConnect), facilitating integration with MES and WMS. This multi-layered approach makes Unity a practical tool for AGV lifecycle management, from controller design to post-deployment optimization.

Mean error values from exhaustive search remained consistently closer to zero across all load levels, see Table 1, indicating better trajectory tracking. Although the empirical method occasionally yielded smaller absolute errors (e.g., at 15 kg), the overall trend favored exhaustive search, which showed greater precision and reduced variation across loads.

Table 1.

Comparison of exhaustive search and Ziegler–Nichols performance metrics.

Moreover, system variability, measured by error standard deviation, was substantially lower with exhaustive-search tuning. For instance, under no-load conditions (0 kg), Ziegler–Nichols produced a standard deviation of cm versus cm for exhaustive search; at 50 kg, this metric dropped from cm to cm. These results confirm that exhaustive search yields more stable trajectories with reduced oscillations.

Lap times showed negligible differences between methods for loads up to 20 kg, varying by at most three seconds. At 50 kg, both methods resulted in identical lap times (98 s), suggesting that, in this case, the lap duration is constrained by the system’s inherent inertia rather than the tuning method employed.

We selected the best gains per load by first identifying triplets with the lowest maximum absolute error, then ranking them by mean absolute error, resulting in controller configurations with optimal peak and average performance.

Table 2 presents the best set of gains for each load condition. The controller identifiers use the letter B to indicate the best-performing configurations. For comparison purposes, Table 3 shows the worst results from the same simulations, identified by the letter W in the Controller ID. Although the mean error values may be similar to those in Table 2, the standard deviation and absolute maximum error reveal significant differences in vehicle performance.

Table 2.

Best results of the exhaustive search.

Table 3.

Worst results of the exhaustive search.

The superior performance of exhaustive-search controllers can be attributed to their ability to systematically explore the parameter space under specific load conditions, resulting in gain combinations that better compensate for system inertia variations. For instance, controllers tuned at moderate loads (e.g., B8 at 50 kg) exhibited higher integral gains () compared to lighter-load configurations (), enabling improved steady-state error correction when vehicle mass increased. This suggests that tuning under representative operational loads produces controllers with inherent robustness to load variations—a critical requirement for industrial AGVs that frequently transport payloads of varying masses.

These differences reveal a key trade-off: exhaustive search demands computational resources but delivers more reliable, reproducible results than empirical methods—particularly for systems with variable loads, where consistency is critical in industrial settings.

This study used classical methods to establish performance baselines. Future work will integrate modern heuristic algorithms—such as genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization—within Unity. These could accelerate convergence and enable adaptive tuning for real-time load changes. The Unity platform’s modular architecture inherently supports such extensions, enabling direct comparative analysis of classical versus metaheuristic methods under identical simulation conditions.

Two operators applied the Ziegler–Nichols method to tune the AGV’s position controller. Table 4 and Table 5 show the results obtained for the different load conditions. From the determination of the critical gain and critical oscillation period, the gains of the P, PI, and PID controllers were computed according to Algorithm 2.

Table 4.

PID gains computed using the Ziegler–Nichols method based on the tuning performed by Operator A for load conditions ranging from 0 to 100 kg.

Table 5.

PID gains computed using the Ziegler–Nichols method based on the tuning performed by Operator B for load conditions ranging from 0 to 100 kg.

Table 4 and Table 5 reveal that operator subjectivity significantly affects Ziegler–Nichols PID tuning, even in a virtual environment. It can be observed that the critical gains calculated using the empirical Ziegler–Nichols method did not vary significantly between operators. However, variations in the measured oscillation period caused large discrepancies in computed PID gains.

The differences observed in the tuned parameters reveal key limitations of the Ziegler–Nichols method in terms of its reliability and reproducibility. As it relies on the accurate identification of specific conditions—such as the critical gain and critical period —the method is highly vulnerable to operator-dependent interpretation. In systems with higher dynamic complexity, such as those involving heavier loads, this vulnerability becomes even more pronounced, resulting in significantly different parameter sets for the same system. This variability undermines the quality of the tuning and, consequently, the performance of the controlled system. It is also noteworthy that, although the proportional gain calculated by the empirical method was similar to that obtained via exhaustive search, the integral and derivative gains exhibited significant discrepancies, which led to instability in all simulations using the PI and PID controllers tuned empirically.

Table 6 compares the PID controller gain values obtained by the operators and through exhaustive search. A trend of increasing divergence in the operator-tuned parameters is observed as the load applied to the AGV increases. The gains , , and exhibited small discrepancies for light loads (0 to 20 kg), with small and consistent absolute differences. However, for higher loads, particularly at 100 kg, these differences became substantial. The proportional gain differed by 0.516 between operators, while the integral gain reached a discrepancy of . This sharp increase in divergence suggests that the dynamic complexity of the system compromises the consistency of the empirical tuning method. Notably, the integral and proportional gains were the most sensitive to variation between operators, indicating that these components are particularly susceptible to subjective interpretations during the identification of the sustained oscillation point.

Table 6.

Comparison of PID gains computed by Operators A and B and the Exhaustive Search (ES) for varying load conditions.

In light of these findings, the adoption of more robust tuning strategies becomes essential. Automated methods or simulation-based exhaustive search techniques are capable of minimizing subjective interference and ensuring greater consistency and standardization in the tuning results.

The current implementation relies on a discretized line sensor model and a differential-drive kinematic constraint, which may introduce biases in reported metrics. For instance, the sensor’s discrete resolution (100 elements) could underestimate small-amplitude oscillations, while the absence of external disturbances (e.g., floor irregularities, wheel slippage) limits the generalizability of tuning results to real-world environments. Future work will validate these findings with physical AGV prototypes and incorporate sensor noise models to assess controller robustness under non-ideal conditions.

From an industrial perspective, the operator-dependent variability observed in Ziegler-Nichols tuning presents significant challenges for standardization and quality assurance in automated manufacturing environments, reinforcing the value of simulation-based optimization approaches that minimize human subjectivity.

After identifying the best gains obtained through the exhaustive search, the controllers tuned to each load condition on the straight-line lane were tested on the infinity-shaped lane. The results, based on the defined performance metrics, are shown in Table 7. Although there is a slight change in the average error values ( change < 0.05 cm), the standard deviation increases by up to 50% compared to Table 2—for example, rising from 0.28 cm to 0.42 cm at 20 kg—highlighting reduced precision on curved tracks. An important aspect of this difference is that the tuning was performed on a track without curves. When the controller is tested on the infinity-shaped lane, its curves force the vehicle to operate under different conditions than those present during the tuning phase.

Table 7.

Best results of the exhaustive search for load conditions ranging from 0 to 100 kg, evaluated on the infinity-shaped lane.

Table 7 also presents the time required for the vehicle to complete a lap. From these values, it can be seen that, for the AGV configuration in the virtual environment, the difference in lap time becomes significant only for loads of 50 kg or more, which reduce the vehicle’s speed and consequently increase the time needed to complete a lap. For loads of 20 kg or less, the lap times remain very similar. These data will also serve as a basis for future comparisons with other controllers.

The results of the simulations conducted by Operator A are presented in Table 8. Based on the data collected from the infinity-shaped lane, a direct comparison between the controllers tuned using the Ziegler–Nichols method applied by Operator A and those obtained through exhaustive search, shown in Table 7, reveals notable differences in performance. High integral and derivative gains caused PI and PID controllers to fail—only P controllers remained on track, except at 100 kg where even P control lost the lane.

Table 8.

Performance metrics and PID gains for Ziegler–Nichols controllers tuned by Operator A, evaluated on infinity-shaped lane (load: 0–100 kg).

For equivalent load conditions (0, 10, 15, 20, and 50 kg), the controllers tuned via exhaustive search consistently exhibited lower mean errors and smaller standard deviations compared to those obtained through empirical tuning, while maintaining comparable lap times.

Four controllers tuned using the exhaustive search method—B1, B7, B8, and B9—and four controllers tuned by Operator A—A0-P, A20-P, A50-P, and A100-P—were included in the analysis, see Table 9. These eight controllers were evaluated under four distinct load conditions to assess the impact of load variation on control performance. Controller B1 failed to maintain the vehicle on track under the 100 kg load condition. Meanwhile, controller A100-P was unable to ensure vehicle stability across all tested load conditions.

Table 9.

Cross-load validation: performance of eight selected controllers (four exhaustive-search, four Ziegler–Nichols) tested under varying load conditions (0, 20, 50, 100 kg).

Controller B9, tuned for 100 kg, also performed consistently across all tested load conditions, with mean errors close to zero and low standard deviations—for example, cm at 50 kg and only cm at 100 kg. The lap time under the design condition was 2852 s, which is comparable to those of the other controllers tested at this load. The consistent performance under lighter loads, such as 0 and 20 kg, reinforces the idea that tuning at full-load conditions can yield controllers capable of maintaining both stability and accuracy across diverse operating scenarios.

In contrast, the empirically tuned controllers, which employed purely proportional action, exhibited greater variability and lower adaptability to load variations. Controller A0-P, tuned for zero load, showed increasing mean error and high standard deviation as the load increased. At 100 kg, although the average error was small ( cm), the lap time was the highest among all configurations (2885 s), indicating a severe limitation in dynamic performance. Controller A20-P demonstrated slightly more stable performance, including at 100 kg (mean error of cm and standard deviation of cm), though the lap time remained excessively high. Controller A50-P, tuned for high load, followed a similar trend, but delivered inferior performance compared to B8, which was tuned for the same condition. These results indicate that, despite its simplicity, pure proportional control exhibits poor adaptability outside its nominal tuning condition, particularly under heavy loads, where stronger integral and derivative actions are needed to ensure control precision and system stability.

The controllers obtained through exhaustive search exhibited lower sensitivity to load variation. For example, controller B1, tuned for zero load, maintained acceptable performance up to 50 kg, with relatively low mean errors and standard deviations, and lap times comparable to those of controllers tuned for specific load points. Controller B7, tuned for 20 kg, showed stable behavior across all load levels, including 100 kg, where it achieved a nearly zero mean error ( cm), a standard deviation of only cm, and a lap time of 2847 s. This high lap time—similar to those observed with B9 and A0-P—indicates that the system remained on track but moved more slowly due to the vehicle’s increased inertia under heavy load. Controller B8, tuned for 50 kg, achieved the best overall performance, with mean errors close to zero and the lowest standard deviations across all load conditions—for instance, cm at 50 kg and cm at 100 kg. The lap time for 100 kg was also significantly lower (2779 s) compared to the other controllers. These findings imply that tuning at moderate loads yields controllers with broad adaptability.

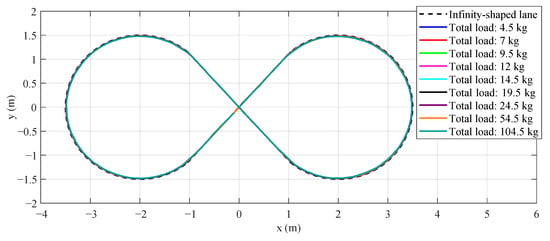

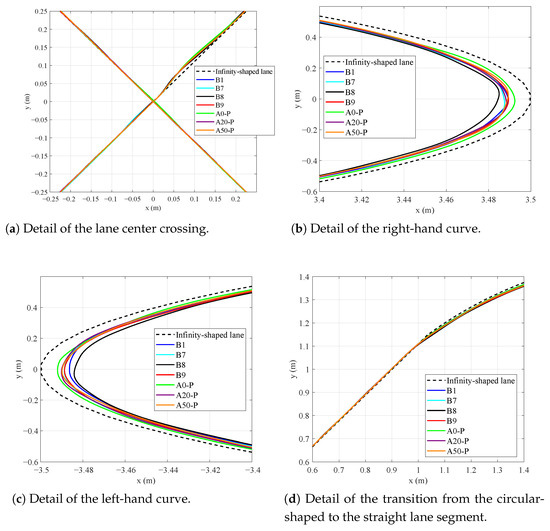

To analyze the results graphically, the paths followed by the vehicle for each controller and load condition are shown in Figure 9. Since the error, although noticeable, is not entirely measurable at the scale of Figure 9, Figure 10 provides detailed views of the paths at specific points on the track.

Figure 9.

AGV trajectories on the infinity-shaped lane for loads 0–100 kg. Curves represent (x,y)(x,y) paths under each load condition.

Figure 10.

Inset views of Figure 9: (a) central intersection disturbance; (b) right curve; (c) left curve; (d) straight-to-arc transition.

Figure 10a shows the central intersection, a point of disturbance for the vehicle due to the abnormal lane width at that location, which may cause the sensor to be triggered in an unintended manner. The graph shows that path disturbances occur, especially in the case of higher loads (starting at 20 kg), although some disturbance is also observed when the AGV operates without load.

The results on the track curves are illustrated in Figure 10b,c. The vehicle’s behavior in both directions of the curve is similar across all load ranges. For heavier loads, starting at 50 kg, the error becomes more pronounced.

Finally, Figure 10d highlights one of the curve sections where the straight segment transitions into an arc, representing a nonlinearity on the track. In this segment, the behavior of all controllers is similar, although controllers under heavier loads again show slightly greater deviations.

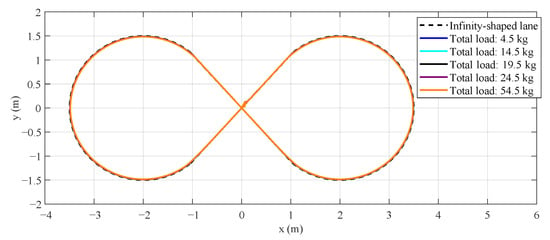

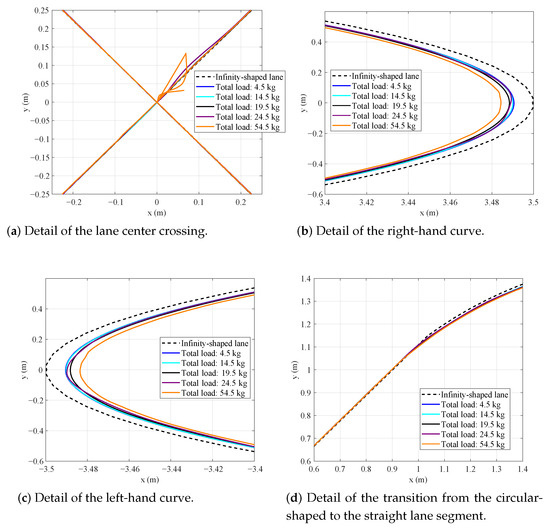

Figure 11 graphically presents the results of the path followed by the AGV during the simulations on the infinity-shaped lane, while Figure 12 provides detailed views of specific segments of the route. Figure 12a focuses on the central intersection, where a slight deviation from the path is observed under the 20 kg load condition, whereas the 50 kg load caused a more pronounced disturbance near the end of the route.

Figure 11.

AGV trajectories on the infinity-shaped lane for Ziegler–Nichols controllers (Operator A).

Figure 12.

Inset views of Figure 11: (a) central intersection disturbance; (b) right curve; (c) left curve; (d) straight-to-arc transition.

Figure 12b,c illustrate the AGV’s behavior along curved sections of the track, and the results closely resemble those presented in Figure 10b,c. Similarly, Figure 12d depicts the transition between a straight and a curved section of the track, also showing results consistent with those of Figure 10d.

Although our virtual line sensor and kinematic model enabled efficient controller testing, they omit several real-world physical effects that can bias performance metrics. First, the sensor’s discrete detection array and perfect trigger behavior ignore sensor noise, ambient lighting variations, and imperfect alignment, all of which in practice introduce measurement jitter and delay. This likely underestimates the true mean error and variability observed in physical AGVs. Second, modeling the vehicle as a rigid differential-drive unit without wheel slip or suspension dynamics neglects traction loss, chassis flexibility, and drivetrain backlash; these factors can degrade controller stability and increase overshoot in curves, meaning our simulated trajectories may appear smoother than real-world behavior. Finally, absence of external disturbances—such as floor friction variability or dynamic obstacles—removes nonrepeatable perturbations that would challenge controller robustness.

We also indicate the need to study incorporation of realistic disturbances—such as sensor noise, wheel slip, and surface friction variability—into the virtual environment. Prototype AGV tests under identical loads and trajectories would then inform the magnitude of simulation-to-reality discrepancies, guiding adjustments to the Unity model.

6. Conclusions

This study aimed to demonstrate Unity 3D as a physics-based simulation platform for AGV control-system development, explicitly addressing dynamic modeling under varying payloads—a capability absent in 96.7% of reviewed AGV simulations works. Through a systematic comparison of two PID tuning methods across nine load conditions (0–100 kg), we quantified Unity’s effectiveness in replicating realistic vehicle dynamics and controller performance.

The proposal was implemented by creating a Unity-based simulation of an industrial setting, where the AGV follows predefined tracks. Within this virtual environment, PID controllers were tuned using two approaches: Exhaustive Search and the Ziegler–Nichols method. These approaches differ in parameter selection—Exhaustive Search systematically scans the entire parameter space for optimal values, while Ziegler–Nichols relies on sustained oscillation tests—enabling a direct comparison between an idealized, data-driven search and a classical, trial-based tuning process.

Quantitative results showed that Exhaustive Search achieved 58% lower standard deviation in lateral error (1.33 cm vs. 2.99 cm at 50 kg) and a 35% reduction in mean absolute error compared to Ziegler–Nichols tuning. However, this performance came at the expense of 60–80 h of computational time, whereas operator-driven Ziegler–Nichols tuning required only 20–40 min per load condition. Inter-operator variability in critical-gain identification reached 84% for integral gain () at 100 kg, underscoring the need for automated parameter-search methods in industrial deployment.

The contributions of this work include: (i) a Unity-based AGV simulation framework that specifically addresses the physics-modeling gap identified in current literature. Unlike the predominant use of kinematic-only models found in our systematic review, this framework leverages the NVIDIA PhysX engine to capture realistic load variations, wheel–ground interactions, and suspension effects typically simplified or omitted in conventional AGV simulations; (ii) a dual-perspective validation methodology bridging the gap between academic simulation and industrial application requirements. In response to our finding that most studies present only simulated results, we offer both a shop-floor support tool for in-situ controller tuning without removing vehicles from production lines and an exhaustive-search optimization platform for thorough parameter-space exploration—both critical for industrial AGV deployment where tuning represents a major bottleneck; and (iii) a flexible performance-evaluation environment within Unity that enables measurement of diverse indicators during simulation. While the present study reports general metrics (mean error, standard deviation, and maximum absolute error), the same data-generation pipeline supports calculation of advanced metrics—such as settling time, overshoot, RMSE, IAE, and ISE—across varying load conditions, facilitating comprehensive, quantitative comparisons of any controller design.

Despite these contributions, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the virtual line sensor employs a discrete 100-element trigger array that does not replicate sensor noise, ambient interference, or calibration drift present in physical optical or magnetic sensors. Second, the dynamic model omits wheel slip, suspension compliance, and drivetrain backlash—factors that can degrade real-world controller. Third, validation was conducted exclusively in simulation; comprehensive validation against motion-capture data from the physical AGV prototype remains pending. These simplifications limit the direct transferability of tuned parameters to physical systems and highlight the need for hybrid simulation–physical tuning workflows.

Future work will extend beyond classical PID tuning by integrating modern heuristic algorithms—such as Genetic Algorithms and Particle Swarm Optimization—directly within the Unity framework. Leveraging Unity’s modular architecture, these metaheuristic methods can be compared side by side with traditional approaches under identical simulation conditions. Moreover, real-time adaptive tuning will be explored by coupling load-variation sensing with online optimization, enabling the AGV to adjust controller parameters on the fly as payloads change. This platform-centric strategy will facilitate a systematic evaluation of classical versus metaheuristic control techniques within a unified virtual environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.P.N.d.R. and O.M.J.; Data curation, V.B.S.C., E.S.V.J. and F.K.K.; Formal analysis, E.S.V.J., F.K.K. and W.P.N.d.R.; Investigation, E.S.V.J. and F.K.K.; Methodology, V.B.S.C.; Project administration, O.M.J.; Software, V.B.S.C., E.S.V.J. and F.K.K.; Supervision, W.P.N.d.R. and O.M.J.; Validation, V.B.S.C., E.S.V.J., F.K.K. and W.P.N.d.R.; Visualization, V.B.S.C.; Writing—original draft, W.P.N.d.R.; Writing—review & editing, W.P.N.d.R. and O.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. Because the dataset is subject to technical and organizational constraints related to its formatting and storage, it is not immediately accessible in a public repository. Data will be shared upon request to ensure ethical and transparent research communication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bechtsis, D.; Tsolakis, N.; Vouzas, M.; Vlachos, D. Industry 4.0: Sustainable material handling processes in industrial environments. In Computer Aided Chemical Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 40, pp. 2281–2286. [Google Scholar]

- Ottogalli, K.; Rosquete, D.; Amundarain, A.; Aguinaga, I.; Borro, D. Flexible framework to model Industry 4.0 processes for virtual simulators. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paula Ferreira, W.; Armellini, F.; De Santa-Eulalia, L.A. Simulation in industry 4.0: A state-of-the-art review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonidis, C.; Nikolaidis, N. Chapter 18–Simulation environments. In Deep Learning for Robot Perception and Cognition; Iosifidis, A., Tefas, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 461–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becue, A.; Fourastier, Y.; Praça, I.; Savarit, A.; Baron, C.; Gradussofs, B.; Pouille, E.; Thomas, C. CyberFactory# 1—Securing the industry 4.0 with cyber-ranges and digital twins. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th Ieee International Workshop on Factory Communication Systems (wfcs), Imperia, Italy, 13–15 June 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, G. Automated Guided Vehicle Systems: A Primer with Practical Applications, 2nd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, W.P.N.d.; Couto, G.E.; Junior, O.M. Automated guided vehicles position control: A systematic literature review. J. Intell. Manuf. 2022, 4, 1483–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Son, B.; Lee, D. Comparative study of physics engines for robot simulation with mechanical interaction. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C.; Gonçalves, J.; Conde, M.Á.; Rodríguez-Sedano, F.J.; Costa, P.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Systematic literature review of realistic simulators applied in educational robotics context. Sensors 2021, 21, 4031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, G.D.; Caesarendra, W.; Petra, M.I.; Królczyk, G.; Glowacz, A. Comparative study of Gazebo and Unity 3D in performing a virtual pick and place of Universal Robot UR3 for assembly process in manufacturing. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2024, 132, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaluz, V.H.; Chicaiza, F.A.; Gallardo, C.; Quevedo, W.X.; Varela, J.; Sánchez, J.S.; Arteaga, O. Unity3D-MatLab simulator in real time for robotics applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality and Computer Graphics, Lecce, Italy, 15–18 June 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 246–263. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Novotny, G.; Smirnov, N.; Morales-Alvarez, W.; Olaverri-Monreal, C. Mobile delivery robots: Mixed reality-based simulation relying on ROS and Unity 3D. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Kang, J.; Eom, D.S. Enhancing ToF Sensor Precision Using 3D Models and Simulation for Vision Inspection in Industrial Mobile Robots. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, J.; Ricks, K. Comparative analysis of ros-unity3d and ros-gazebo for mobile ground robot simulation. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 106, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unity Education Grant License. 2024. Available online: https://unity.com/products/unity-education-grant-license (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Yu, C.C. Autotuning of PID Controllers: A Relay Feedback Approach, 2nd ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2006; p. 261. [Google Scholar]

- Desborough, L.; Miller, R. Increasing customer value of industrial control performance monitoring-Honeywell’s experience. In AIChE Symposium Series; number 326 in 326; American Institute of Chemical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 169–189. [Google Scholar]

- Moshayedi, A.J.; Li, J.; Sina, N.; Chen, X.; Liao, L.; Gheisari, M.; Xie, X. Simulation and Validation of Optimized PID Controller in AGV (Automated Guided Vehicles) Model Using PSO and BAS Algorithms. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2023, 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.; Zalama, E.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. A simulation and control framework for AGV based transport systems. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2022, 116, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra-Garcia, J.E.; Santos, M. Combining reinforcement learning and conventional control to improve automatic guided vehicles tracking of complex trajectories. Expert Syst. 2022, 2, e13076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Wan, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, Y.; Guo, J. Yaw stability control of automated guided vehicle under the condition of centroid variation. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2022, 44, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]