Abstract

The world is being orchestrated by dramatic changes caused by technological and innovative disruptions. Accordingly, Industry X.0 terminology was coined because the revolutionary numbers could not represent this industrial disruption. Coping with these technological disruptions is essential for an organization’s sustainability and resilience. Therefore, defining the technological gaps, as well as mapping the potential innovative disruptions for industrial systems, becomes compulsory. Technology Readiness Levels is a standardized method widely adopted to evaluate the maturity of a technology, using a scale from 1 (concept) to 9 (commercialized solution). This framework helps stakeholders to benchmark different industrial systems from a technology innovation perspective. However, TRL sometimes fails to capture the maturity of breakthrough innovations and lacks quantification. In this paper, a comprehensive framework for assessing technological readiness levels is proposed. The automotive industry was selected as one of the top technology-related industries to validate this framework. This framework maps the technological readiness levels of the following three main industry components: product, engineering, and operations. A tailored Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) model has been employed as a benchmarking approach to evaluate the technological readiness gaps and map the technological footprint position of a selected automotive company across the best practices in the automotive industry.

1. Introduction

1.1. The Influences of the Technological and Innovative Disruptions on the Industrial Revolutions’ Lifetime Spans

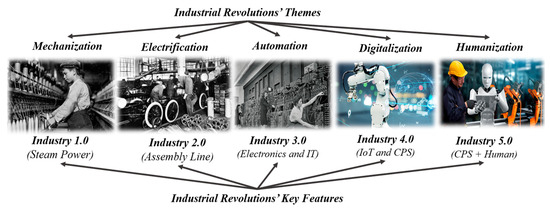

During the 1700s, the invention of steam power paved the path to the era of machinery. The textile industry and the evolution of locomotive systems marked the beginning of the first industrial revolution [1]. One century later, the evolution of electricity guided Henry Ford to develop the concept of mass production and assembly lines, which revolutionized the Second Industrial Revolution [2]. After World War II (WWII), the transformation journey from analog to digital and the birth of electronics and production automation paved the way for the Third Industrial Revolution [3]. During the 2000s, the birth of the Internet of Things (IoT), Artificial Intelligence (AI), along with the new stream of Big Data Analytics (BDA) and Cyber Physical Systems (CPS), shaped the architecture of Industry 4.0 [4]. Around 2020, industrial ecosystems recognized the significance of cognitive interaction between humans and robots, which generates intelligent harmony and optimizes industrial productivity. Consequently, Industry 5.0 is now being coined [5]. Each industrial revolution has a specific theme and key features based on a significant technological disruption, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Industrial Revolutions’ themes and key features. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [6]. 2024, Ahmed H. Salem.

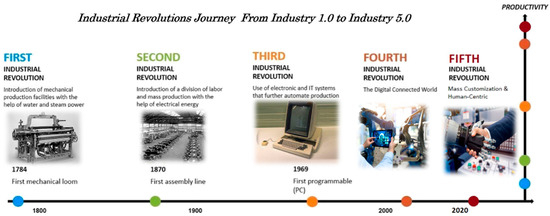

There is a significant relationship between technological and innovative disruptions and the Industrial Revolution. Currently, the lifetime of the Industrial Revolution is rapidly declining, while industrial productivity is booming, as shown in Figure 2. As technological evolutions are booming fast, the cycles of industry become much more prevalent and dynamic, and, hence, can be considered as a dynamic variable X. This is why the Industry X.0 concept has been introduced. Therefore, the industrial and business ecosystems should be more flexible and agile to adapt to rapid changes.

Figure 2.

Industrial revolutions timeline vs. productivity. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [6]. 2024, Ahmed H. Salem.

1.2. The Significance of the Technological Readiness Evaluation of the Ideal Shape of Industry in the Industry X.0 Era

The traditional and current business behavior in any industry worldwide may be inadequate to cope with the rapid innovative disruptions. The industrial sector is not keeping pace with the continuously evolving technological developments promptly. There is a gap between recent technologies and industrial behavior. Therefore, evaluating the readiness for technological disruptions in any industrial behavior creates new industrial cultures that could exist in a world of change. Moreover, this is necessary to keep up with market competition and sustain eco-friendly industrial systems.

As per Schaeffer [7], the ideal shape of industry in the Industry X.0 practice consists of the following three main industrial components: Product X.0, Engineering X.0, and Operations X.0. These three components should be harmonized instantly with the technological and innovative disruptions to optimize the readiness capabilities of any industrial system. Therefore, the new terminology of Industry X.0 could be defined as the new definition of Industry X.0 as how technological disruptions are transforming between different industrial components and layers. Regarding Product X.0 it is defined as a new smart connected product that intelligently, digitally, and effectively integrates with the entire Industry X.0 model. For Engineering X.0, it is embracing the use of digital T’s (Twins, Threads, Technology, and Transformation) and deploying them during the engineering practices such as managing the concept of the product. Finally, Operations X.0 engage all operational practices and value chains starting from the manufacturing stage until the continual feedback of the end user toward ultimate levels of operational excellence. According to Schaeffer et al. [8], new technological Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) terminologies, such as “Flexiagility” have been introduced in the era of Industry X.0, which means that the responsiveness level of any Industry X.0 system should be flexible as well as agile to the rapid technological and innovative changes. As a result, evaluating the technological readiness of industries becomes obligatory to optimize the sustainability and resilience capabilities of the Industry X.0 system.

1.3. The Impacts of Technological Disruption on the Automotive Industry

This technological disruption has affected a broad spectrum of industries. One of the most significantly affected industries is the automotive industry. The dynamics of the entire industry are undergoing a paradigm shift due to rapid technological development in automotive capabilities, the demand for sustainable solutions, and the rise in sharing platforms. A new era is dawning, where established automotive companies’ competition is becoming aggressive due to this technological disruption, besides the quick movement towards automation and autonomous vehicles [9]. In 1988, Foster presented his well-known S-curve model, which states that technology starts with a phase of moderate performance growth, expands quickly, and then matures with a phase of limited progress [10]. Christensen, in 1997 [11], showed that when a new product architecture is about to be developed, pioneers have an edge over other competitors in the same industry. He popularized the idea of disruptive innovation, which is the process by which new businesses replace established ones and move away from promising technological capabilities. Additionally, according to Foster, entrepreneurs have a competitive edge because of their flexibility and adaptability to change. As the S-curve of technological development claims that the need for continually upgrading the technology is a must for survival performance in order to compete in the industry, today’s technological disruption, which is continuously trending up, is urging automotive industry leaders and practitioners to be agile and responsive to the change [12,13]. In addition to the technological invasion in the automotive industry, this industry is crucial to the economy locally and worldwide. The automotive industry is a significant driver of the world’s economy, directly impacting Gross Domestic Product (GDP). It has a strong political influence and hosts the highest number of employees [14]. Moreover, it combines some of the other industries, such as the electronics and high-tech industries. Therefore, the automotive industry has been selected as the scope for studying and evaluating technological disruption and Technology Readiness Level (TRL) assessment in the Industry X.0 era. Despite the importance of the automotive industry and the availability of technologies that enhance this sector, there is always a challenge in benchmarking your automotive company among others, as well as assessing your technology readiness for adopting these technologies [15].

According to the initial research, the high-tech industries, like the automotive industry, are most influenced by technological disruptions due to their ecosystem nature and behavior. In addition, it does not only affect the world’s economy, but it also has a significant impact on political influence. However, there is a gap in quantifying the technological disruption in these industries while addressing the corresponding areas of improvement to cope with these disruptions. Moreover, the previously proposed solutions lacked a systematic approach tailored for automotive benchmarking and TRL assessment. Additionally, most of the developed models were human-biased or qualitative assessments that are not compatible with the modern, dynamic world.

Thus, the scope of this research focuses on technological disruptions and their impact on industry in general and the automotive industry in particular. The approach will determine the most proper relationship between these technological disruptions and the automotive industry practices, as this gap hinders the utilization of emerging technologies and affects the success of any improvement plans in automotive companies.

This paper aims to develop technological pillars and quantitative, non-biased evaluation methodologies, which are crucial for tracking technological performance and behavior. This study entails four main research objectives:

- Determine the state-of-the-art technology based on X.0 practice.

- Define the major Industry X.0 layers and the corresponding sub-layers.

- Develop a generic framework to assess a target company’s gaps in adopting X.0 technologies in the automotive industry.

- Validate the framework by applying it to the automotive industry.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 covers the literature review, including benchmarking techniques, and explains the Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) as a benchmarking model. Section 3 presents the research methodology and the proposed framework. Section 4 discusses the key findings and results of the study. Finally, Section 5 presents the study’s conclusions and potential future work.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Benchmarking Paradigms and Techniques

Benchmarking is a strategic business tool that has become increasingly essential for organizations across various industries to stay competitive and drive continuous improvement. By comparing processes, products, services, or performance metrics against industry’s best practices or competitors, benchmarking enables companies to identify areas for enhancement, innovation, and efficiency gains.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were the development of benchmarking as a formal, methodical approach for performance improvement in the corporate sector [16]. According to Camp [17], Xerox was the first company to initiate employing benchmarking through its manufacturing operations. It implemented a new procedure in early 1979 called competitive benchmarking to analyze its unit production costs and compare them with those of rival copiers based on their mechanical components, features, and operational capabilities. Since then, more activities have progressively begun to use benchmarking due to its effective implementation.

The definition of benchmarking has evolved over the years. Abstractly, benchmarking could be defined as the pursuit of industry’s best practices that result in enhanced performance. According to Watson in 1993 [18], benchmarking is the ongoing search and use of better practices that result in the implementation of benchmarking concepts and superior competitive performance. Compared to other studies, Harrington and Harrington in 1996 [19] provided a more inclusive definition of benchmarking, as it is a methodical approach to identifying, comprehending, and innovatively developing improved goods, services, machinery, procedures, and practices to enhance an organization’s overall performance. The American Productivity and Quality Center defined benchmarking in 1998 [20] as the process of continuously identifying, understanding, studying, and analyzing exceptional practices and methods from both within and outside the organization, followed by implementation to encompass all aspects of the organization. Furthermore, Moriarty and Smallman in 2009 [21] claimed that benchmarking is not a general evaluation tool for the organization among its competitors. Still, it is a model-driven teleological process that operates within an organization to transform an existing state of an aspect into a higher state of the same specific aspect.

Multiple definitions differ based on the scope and application. Nevertheless, it could be summarized from all the definitions that benchmarking includes finding opportunities for improvement, searching for best practices (both inside and outside the industry), and then evaluating the system’s readiness, adapting, and implementing these best practices in a methodical, ordered, and standardized way to address the specialties and diversities of a company’s own processes and priorities.

Benchmarking using TRL is a widely used approach for assessing different industries’ capabilities compared to other competitors within the technology innovation scope. It has various methods and models that could be employed in this manner. One of these methods is the Delphi method, which involves surveying experts in the field about predetermined relative questions and/or Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) identified in the benchmark study. In ref. [9], the authors address the technological disruption and benchmarking through utilizing an email survey to gather relative TRL scores for each question. They gave a clear set of steps for their approach, besides a study on 300 Indian vehicle manufacturers, which is part of the mixed-method research strategy used to conduct the study. The data analysis included 3 more case studies and 48 valid responses out of 300. The goal of including case studies was to gain a deeper understanding of the problems associated with adopting best practices and then implementing benchmarking initiatives. However, there would be a level of bias that could not be mitigated. The authors suggested using a larger sample size in the future to replicate and generalize research findings. However, quantifying human errors and mitigating bias was not achieved. Using the same method, authors in [22] employed the Delphi method associated with the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to enhance the quality of results of a survey study. They achieved a better result with more effective mitigation plans. Nonetheless, the application was different as the study focused on the cold supply chain. Also, AHP depends on arbitrary pairwise comparisons, which could introduce bias and inconsistency [23]. It can be challenging to provide numerical values to these comparisons, particularly when dealing with ambiguous criteria or novice decision-makers, which compromise the validity of the model. Because of its vulnerability to the rank reversal problem [24], AHP’s results are susceptible to changes in input and have a declining reliability.

Another study addresses the limitations of the traditional TRL framework in effectively assessing and guiding the maturity of innovations developed through co-creation and collaborative models [25]. Co-creation is defined as a mode of technology development in which developers collaboratively work on developing and introducing the technology within an organization. The authors demonstrate, through an empirical case study of an AI-based energy forecasting technology, that many innovations plateau at TRL 6/7 because they lack standalone market value, highlighting a critical gap where the classical TRL approach fails to capture the complexities of modern hybrid innovation ecosystems. To address this, the paper contributes a conceptual extension to the TRL framework by introducing additional co-creative steps (7C1 to 7C3) that emphasize defining co-creative value, actors, and solution interoperability, enabling a more accurate evaluation and progression path for innovations embedded in multi-stakeholder environments. While the proposed amendment offers a promising approach to better accommodate collaborative innovation, the study acknowledges the need for further empirical validation across diverse innovation types. It recognizes that the traditional TRL remains relevant and dominant, necessitating a balanced integration of new models with existing assessment schemes. Although this paper provides a more comprehensive framework to accommodate more technological modes in current industrial systems, it lacks the quantification needed for benchmarking.

Another approach for benchmarking is fuzzy decision-making. Görçünin et al. [26] surveyed multiple fuzzy decision-making approaches utilized for benchmarking in different applications, then identified the gap, and developed a fuzzy logic to fill in this gap. The paper presented a solid, practical, and reliable methodological framework that could transcend the present, incredibly complex ambiguity by considering the industry’s goals and identifying deficiencies. Practitioners in the automotive sector recognized the importance of digital transformation and its implementation after evaluating the results obtained by using the recommended process. However, they lacked a plan of how to proceed. Also, authors were focusing only on the strategic level assessment of not all levels of the three main industrial components, as mentioned in the Section 1, which could be misleading in interpreting the results and taking corrective actions. Despite the effectiveness of fuzzy logic implementation in benchmarking and its advantages in eliminating any methodological errors, it requires intensive preparation and development that could be complex in some cases [27].

The third approach for benchmarking and TRL is the Data Envelopment Analysis. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) is a non-parametric mathematical technique used for evaluating the relative efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs) within a given set [28]. DEA is commonly used among various mathematical model techniques because it is a cost-effective modeling technique, in addition to being a non-parametric model [29]. Researchers in [30] addressed the challenge of benchmarking service industries and the scarcity of data by presenting a comprehensive framework, verified through a case study implementation utilizing the DEA model. The suggested method utilizes DEA, specifically the pure output model without inputs, to quantify the total service quality of multiple units using SERVPERF as a multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach. The SERVPERF model’s five dimensions are regarded as its output. For the sake of demonstration, a case study of auto repair services is given. The gap in this research was in the scoring scale; the authors used a 100-point scale, which was misleading in operating the proposed model, besides their focus on the service industry, which differs from manufacturing industries in some aspects of their implementation steps. Furthermore, authors in [31] utilized Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) as the ranking method of the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) Business Excellence Model in Iran’s automotive industry. The model used is efficient and reasonably performing its intended job and fulfilling one of the most critical gaps, which provides a benchmarking general model in the automotive industry. In spite of the roadmap provided by the authors, the study had ambiguity regarding the implementation steps, guidelines, and challenges faced.

2.2. Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)

This section reviews the different capabilities and basic concepts of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). DEA is a robust linear programming-based method used to evaluate the relative efficiency of decision-making units (DMUs) operating under similar conditions. DEA has gained popularity due to its flexibility, simplicity, and ability to handle multiple inputs and outputs. DEA provides an efficiency score for each DMU, which measures how well the DMU uses its inputs to produce its outputs. DEA has been widely used in various fields, including technology, to evaluate efficiency and identify areas for improvement. This literature review will discuss some of the key studies that have used DEA in technology.

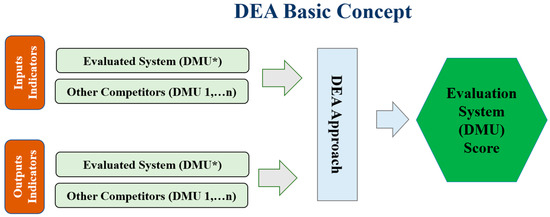

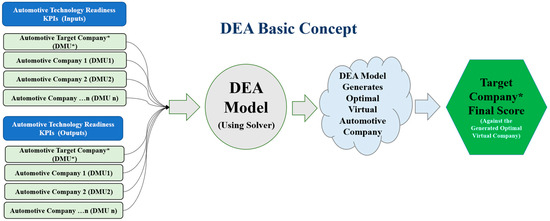

DEA has been used in software development to evaluate different development teams’ efficiency and identify areas for improvement. A study by González-Pachón et al. [32] used DEA to assess the efficiency of software development teams in the automotive industry. Another paper by Salem et al. [33] proposed the DEA as a productivity scoring system used in different industrial practices, specifically the automotive sector, petroleum, and electronics. They developed a multilayer green assessment model using the basic DEA mechanism shown in Figure 3, which can serve as a global guidance map for basic DEA concepts.

Figure 3.

Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) mechanism, “DMU* is the evaluated system”. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. 2025, Ahmed H. Salem.

According to Charnes et al. [28], there are two different types of DEA models: the output-oriented DEA model, where the Linear Programming (LP) model aims to maximize the DMU outputs with the same inputs, and the input-oriented DEA model, which seeks to minimize the inputs while keeping the amount of production unchanged. In the Model, the output-oriented model is preferred to fit the model’s aim.

As claimed in ref. [35], the DEA model should contain desirable outputs to obtain accurate efficiency results. It is not appropriate to integrate the assumptions used by the traditional DEA, maximizing the output quantities and minimizing the input quantities, while there are desirable and undesirable outputs in the same model. Thus, the undesirable outputs conflict with the desirable outputs, resulting in inaccurate results. In case there is a problem when all outputs are undesirable, there are four different methodologies to overcome this obstacle.

- Ignoring the undesirable output, which was proved to be illogical, as they are real outputs from the DMU, and they could not be ignored.

- Treating undesirable outputs as inputs, which also proved to be ineffective during the DEA calculations, because the DEA model should consist of different inputs and outputs.

- Non-linear monotonic decreasing transformation approach (Data transformation), since the undesirable output is modeled as being desirable , where is the undesirable output; this method proved to be the most appropriate solution for the problem.

- Linear monotonic decreasing transformation approach, where the sign of the undesirable output is changed, which was proven to be inaccurate.

3. Methodology

According to the literature, there is an urgent need for clear guidelines to support automotive industry leaders and practitioners in assessing a company’s Technology Readiness Level (TRL) as well as a unified benchmarking and evaluation method for the automotive industry. Additionally, this framework should be associated with a valid benchmarking model. Therefore, the methodology followed to fill this research gap proposes a generic framework applicable to any automotive industry, regardless of its size or other technical attributes. This framework will be integrated with the DEA model assessing Technology Readiness Level TRL KPIs for a selected automotive company (the target company will be evaluated in this proposed framework “Company *”). This solution will be validated using one of the fast-growing automotive companies as a case study.

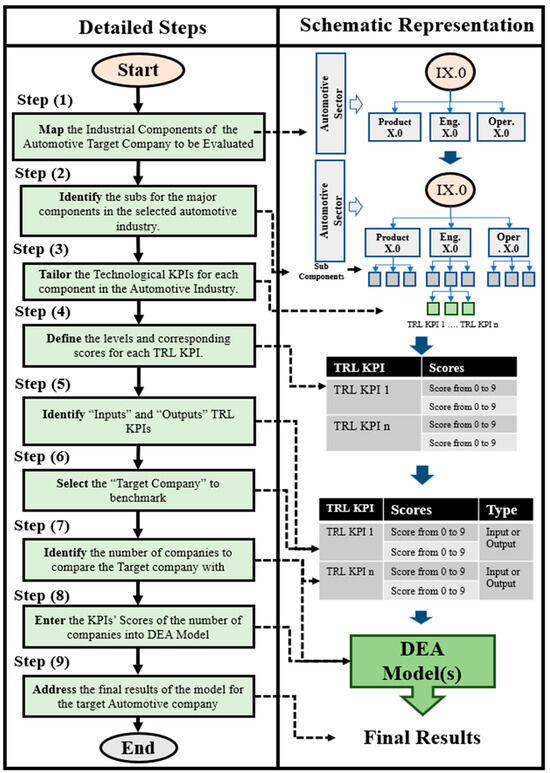

3.1. The Evaluation Framework Architecture and Procedure

In this section, the first aim of this study is explained. This component is developing a general consolidated framework for assessing TRL KPIs of any automotive company among its competitors. As shown in Figure 4, the multi-layer evaluation framework consists of nine main steps. The first five steps are not company-dependent; they are obtained from the automotive industry and are documented without any given scores. Then, the targeted automotive company and its competitors are chosen, ensuring they have the same characteristics to avoid any results bias. Afterward, the TRL KPIs are identified based on the benchmarking type and purpose. In each step, the schematic previews show the User Experience using the proposed system. After providing the DEA model with all requirements, it begins operating to obtain the desired results, which are displayed in the designed dashboard.

Figure 4.

Proposed evaluation framework. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. 2025, Ahmed H. Salem.

The details of the proposed evaluation framework are summarized in nine steps as follows:

- Map the industrial components of the target company (the selected company which is being evaluated); in this step, the three main industry components should be defined and detailed in terms of Product X.0, Engineering X.0, and Operations X.0.

- Identify the sub-components of the target company, so before identifying the technological KPIs, the sub-components of the concerned industry should be defined; for example, the sub-components of automotive industry are completely different than the sub-components of the home appliance industry.

- Tailor the technological KPIs for the selected industry, which is automotive industry in this case study. In this step, the TRL KPIs for the selected industry (Automotive) contain some specific TRL KPIs; for example, TRL KPIs in Table 1.

Table 1. Samples of the tailored technological readiness KPIs in the automotive industry.

Table 1. Samples of the tailored technological readiness KPIs in the automotive industry. - Define the levels and selection intervals of TRL KPIs for the selected industry, so by default TRL KPIs are generic and range from zero to nine, so these tailored TRL KPIs for each specific industry may have some different ranges and intervals based on the nature of the tailored TRL KPI.

- Identify and classify the TRL KPIs into inputs and outputs, since the model used is DEA and it is an output-oriented model, so all tailored TRL KPIs should be classified into outputs and inputs KPIs.

- Select, define, identify TRL KPIs values of the target company to be injected in the model to be evaluated.

- Identify the most common competitors of the selected target company to generate the optimal frontier DMU (virtual optimal company).

- Collect the TRL KPI values of all competitors to be injected into the DEA model.

- Generate and address the results of the selected company among the optimal virtual company.

Starting from step 3, the tailored TRL KPIs for every Industry X.0 were created to meet the primary goal of the study, which was to assess the degree of technological readiness in a particular automotive company. The Technology Readiness Level (TRL) standard scoring scale serves as the basis for these customized TRL KPIs. A score of zero denotes an untested concept with no testing performed, while a score of nine indicates a complete deployment of technology.

Four categories have been created from the TRL KPI scores, ranging from zero to nine: the idea phase is scored on a scale of zero to four. The prototype phase is represented by scores four and five, the validation phase by scores six and seven, and the full implementation and deployment phase by scores eight and nine. Each industry component’s suggested technology readiness KPIs has been created to be general enough to work with a variety of industry types. Table 1 shows some examples of TRL KPIs for the three components of the automotive industry. Table 2 illustrates the details of one sample TRL KPI and how it is tailored to overcome and avoid human bias for input TRL KPI number 38 in Appendix A.

Table 2.

Sample of one detailed tailored technological readiness KPIs in the automotive industry.

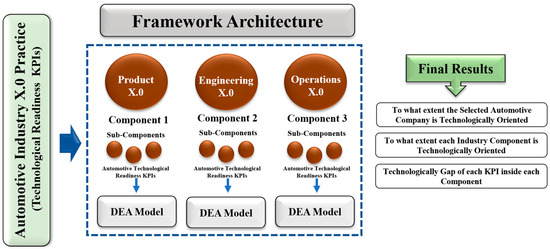

After defining the Industry X.0 components’ details, the proposed multi-layer framework’s boundary and architecture are framed as shown in Figure 5. Based on the defined industry layers, this multi-layer framework is developed to fit in any level of the automotive industry. The Industry X.0 practice of a specific automotive company type will select the most representative KPIs’ statements from the tailored TRL KPIs repository of this industry type. Then, the DEA model will benchmark this industrial practice against the optimal practice of the most advanced practices in the same industry type. The results and outcomes of this framework are technological scores, and they are summarized in three points as follows:

- Top level of results (1): it shows to what extent the selected automotive company is technologically oriented.

- Middle level of results (2): this level of results shows to what extent each industry component is technologically oriented.

- Deep level of results (3): finally, this level shows the technological gaps of selected and specific major KPIs inside each component—further details on references.

Figure 5.

The evaluation framework architecture for Automotive Industry. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. 2025, Ahmed H. Salem.

3.2. DEA Model

The used DEA model is a maximization model. The basic concept of the model used is illustrated in Figure 6. It takes the KPIs of the selected automotive company (DMU*) as well as competitors (DMU 1, 2, …, n). It utilized the mathematical model shown in Equations (1)–(6) [28] in order to generate an optimal virtual company, then compared the selected company with the optimal virtual company generated to obtain the desired score.

Figure 6.

DEA architecture. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. 2025, Ahmed H. Salem.

The detailed functions of the output-oriented model (maximization model) are explained. The output-oriented model of technical efficiency of a system is generating the output from the input; is measured as:

where (N) represents the number of DMUs, stands for the weight of DMU, stands for the output of j DMU, and finally, stands for the input of DMU.

In conclusion, DEA is a powerful technique that has been widely used in the technology industry to evaluate efficiency and identify areas for improvement. The literature review shows that DEA has been used in software development, IT, telecommunications, manufacturing, and cybersecurity to evaluate efficiency and identify relative scoring systems.

These studies discussed in this literature review have highlighted the usefulness of DEA in identifying areas for improvement and driving performance improvements in the technology industry. By providing a non-parametric method for evaluating the relative efficiency of DMUs, DEA can help identify areas for improvement and drive performance improvements in different industrial sectors.

3.3. Case Study Implementation

This section explores the validation of the framework through case study implementation as well as the selection criteria of the most advanced automotive companies. Four automotive manufacturer giants have been selected based on the availability of their annual reports, including technological data and information, as well as their prestigious brand names in the automotive industry. These four automotive practices represent the most advanced automotive decision-making units (DMUs) used in this framework’s DEA models.

The selected company (Company*) is one of the top-growing autonomous car manufacturers. It has been chosen as the concerned DMU to be evaluated against the remaining four automotive manufacturer giants. The technical annual reports of the four remaining giants have been reviewed, investigated, and analyzed to extract the latest and most up-to-date technological KPIs that can be incorporated into the developed model.

Based on deep investigations and conducted analysis, all selected KPIs for all four automotive giants are shown in Appendix A. Based on the selected KPIs’ references, some information, annual records, and raw data from these annual reports have been re-calculated to select the most appropriate KPI sub-statement properly.

4. Results and Discussion

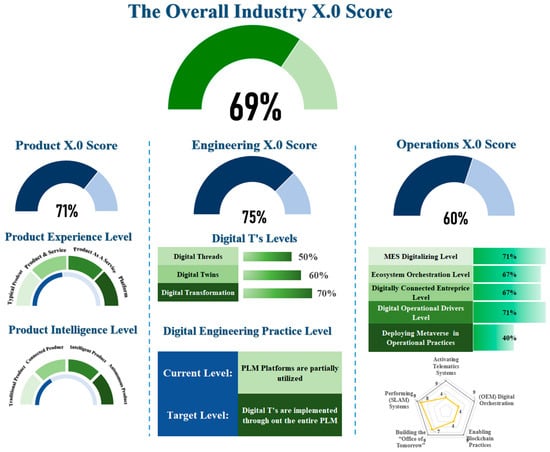

The results generated from the developed model are classified into three levels discussed earlier; the top level is the final Industry X.0 score, which is calculated based on the average scores from the middle level scores. It shows to what extent the selected automotive company* is Industry X.0 or technologically oriented. The second-level scores have been calculated from standalone DEA models for each industry component, Product X.0, Engineering X.0, and Operations X.0 components. The scores at this level represent how much each specific industry component is technologically oriented. Digging more into the deeper level, it is seen that it concerns the particular behaviors of specific TRL KPIs in each component.

Regarding the selected company’s results, Figure 7 shows the results of implementing the framework in each level and component. Illustrating that the overall technological-orientation score (Industry X.0 score) is 69%, calculated as an average result generated from each DEA model in each industry component. This 69% is an average (Arithmetic Mean) result of 71%, 75%, and 60%, assuming equal weights of the three components.

Figure 7.

The framework results of the selected automotive company. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [34]. 2025, Ahmed H. Salem.

Moving towards more details, the Product X.0 score is 71% generated from the customized DEA model of the Product X.0 component, considering the existing TRL KPIs of four automotive giants. Engineering X.0 and Operations X.0 scored 75% and 60%, respectively. Finally, the last deeper level of results represents customized details of each industry component. For example, in the Product X.0 component, there are two main modern concerns related to the technological readiness of products.

These two concerns are the product experience level and the product intelligence level. Inside each of them, there are four categories related to sequential experience and intelligence levels. The same steps are carried out for Engineering X.0 and Operations X.0. Digital T’s (Digital Threads, Digital Twins, and Digital Transforming) represent the core pillar of the Engineering X.0 practice. In contrast, the ecosystem orchestration level and digital operational driver level are combined to form Operations X.0 level.

5. Conclusions

Due to today’s high competition in the automotive industry, the need for a well-established benchmarking technique has been raised. Therefore, this study aims to provide a framework that benchmarks the technological readiness gaps of a selected automotive company against the best optimal practices of the most advanced automotive practices. There is a direct technological relationship between all industry components in the automotive industry. In fact, there is a significant technological readiness relationship between product and engineering components. However, automotive technological operational practices may be performed independently. Product X.0 component and engineering X.0 component results are almost the same.

The proposed framework draws the existing technological readiness gaps of a selected automotive practice, based on analytical and strategic points of view. It showed the detailed results of each industry component and how they are propagated up to affect the overall Industry X.0 result (score). The proposed framework also identifies the technological position of a specific automotive practice. It maps it across the top competitors in the same field and the optimal virtual practice generated from the DEA models.

Some practices thought they were acquiring the technological disruptive features. However, they needed to determine how far they were using these technological disruptions. Using this framework, the stakeholders concerned can strategically identify their technological footprint among the top advanced practices in the same industry type. Consequently, the resistance to change will be eliminated sequentially by defining the technological footprint and mapping the technological position among the same competitors to sustain and improve the competition position. Finally, this framework encourages the stakeholders and the chief technology officers to look deeper into the correct and standard technological terminologies and abbreviations. Moreover, this framework supports and guides the managers at different managerial and operational levels to emphasis the technological positions and gaps for seeking the ultimate levels of optimizing the operational excellence goals.

To take this study to the next level, future work is expected to develop an integrated AI module to collect automatically and digitally the concerned TRL KPIs during the industrial practice, which will be a perfect chance to enhance this evaluation framework. Moreover, this integrated AI module may translate the common industrial practices and behaviors into the required technological TRL KPIs to be added digitally into the framework model. In addition, the weights for each tailored TRL KPI are recommended to be adjusted according to market statistics and not to be assumed as equal weights for better interpretations. Also, targeting sustainable and circular technologies and ecosystems will be considered and integrated into this framework in order to seek the ultimate levels of organizational excellence goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.H.S. and T.M.K.; methodology, K.M.M.; software, A.H.S.; validation, A.H.S., M.F.A., K.M.M. and T.M.K.; formal analysis, A.H.S. and M.F.A.; investigation, K.M.M.; resources, A.H.S.; data curation, A.H.S. and M.F.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H.S. and K.M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.F.A. and T.M.K.; visualization, A.H.S.; supervision, T.M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DEA | Data Envelopment Analysis |

| WWII | World War II |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BDA | Big Data Analytics |

| CPS | Cyber Physical System |

| KPIs | Key Performance Indicators |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| DMU | Decision-Making Units |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| EFQM | European Foundation for Quality Management |

| LP | Linear Programming |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| V2X | Vehicle-2-Everything |

| MES | Manufacturing Execution System |

Appendix A

This appendix includes a comprehensive list of the KPIs with the DMU scoring used in the proposed DEA-based proposed framework.

Table A1.

TRL KPIs’ Scores of all DMUs.

Table A1.

TRL KPIs’ Scores of all DMUs.

| # | Automotive TRL KPI Description | Type | Company* DMU* | Company 1 DMU (2) | Company 2 DMU (3) | Company 3 DMU (4) | Company 4 DMU (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Vehicle-2-Vehicle (V2V) Connection | Input | 4 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| 2 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Vehicle-2-Infrastructure (V2I) Connection | Input | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 3 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Vehicle-2-Everything (V2X) Connection | Input | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 4 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Biometric Seating and Human Interactions Capabilities | Output | 8 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| 5 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Improving Security Against Cyber Attacks | Output | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 5 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Meeting Regulatory Legislation and Standardization | Input | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| 6 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Performing Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) Systems and Platforms | Input | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| 7 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Smartphones Penetrations between the entire Ecosystem Layers | Input | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| 8 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Vehicle Optimization via Cloud-Supported Vehicle Analytics Updates, (Over-The-Air (OTA) Software updates and optimization of configurations) and Implementing Re-Engineering on the Fly (OTF) Concepts | Output | 8 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 9 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Synchronizing Real-Time Date Navigation and Traffic Information | Input | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 10 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Vehicle Features as a Service (Dynamic Activation/Deactivation of paid add-on services) | Input | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 11 | Level of Product Flexagility (Flexagility combines flexibility, the willingness and capability to change, and agility, the speed of change) | Input | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| 12 | Level of Data Augmentation and Leveraging AI | Output | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 13 | Level of Ecosystem Orchestration (Level of Industrial Business Engagement) | Input | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 14 | “As-A-Platform” Competencies and Implementation Level | Output | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| 15 | Level of Digital Engineering Practices Continuity | Output | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| 16 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Full Digital Assets Management System | Output | 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 3 |

| 17 | Engineering Return on Digital Investment (RODI) and Engineering Return on Innovation Investment (ROI2) Levels | Output | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 18 | Level of Digitalizing the Manufacturing Execution System (MES) | Input | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 19 | Level of Car Connectivity (Connectivity Type) | Output | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 20 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Digital Twins in Automotive Engineering Practices | Input | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 21 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Digital Threads in Automotive Engineering Practices | Input | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| 22 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Digital Transformation in Automotive Engineering Practices | Input | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 23 | Level of Acquiring Next-Generation R&D in the Automotive Industry | Output | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 24 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Implementing Circular Car | Output | 8 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| 25 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Activating Telematics Systems and Associated Features on New Cars | Output | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 26 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Adopting Edge Computing and AI in real-time processing of Operational Datasets | Output | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| 27 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Adopting Virtual Simulations and Digital Twins Technologies in Operations (Training, Test Driving, Remote assistance, …) | Output | 7 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 4 |

| 28 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Enabling Blockchain Practices in Different Automotive Operations Practices (Payments, Insurance, Personal Information, …) | Output | 8 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 29 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Automotive Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) Digital Orchestration (Digital Synchronization between Supply chain (Suppliers) and Manufacturing (Shop floor) | Output | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| 30 | Automotive Digital Operational Drivers | Input | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 31 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Facilitating Fleet Management using Emerging Mobility Services | Input | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| 32 | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) of Building the “Office of Tomorrow” with Digital Workplaces | Input | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 33 | Level of Enabling the Digitally Connected Enterprise | Input | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 34 | Level of Deploying Metaverse Opportunities in Operational Practices in the Automotive Industry | Output | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| 35 | Level of Sensing Digital Dynamic Capabilities (DDC) in Operations in the Automotive Industry (Detect digitally enabled growth potential) | Output | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 36 | Level of Seizing Digital Dynamic Capabilities (DDC) in Operations in the Automotive Industry (Leverage digitally enabled growth potential) | Output | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 37 | Level of Transforming Digital Dynamic Capabilities (DDC) in Operations in the Automotive Industry (Transform capabilities to realize the full potential of digital strategic change) | Output | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| 38 | Level of Digital Support Roles in the Automotive Industry | Input | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 39 | Level of On-Going Human Elements Dynamic Analysis | Input | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 40 | Level of Data Augmentation and Leveraging AI | Output | 4 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

References

- Mohajan, H. The First Industrial Revolution: Creation of a New Global Human Era. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/96644/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Mohajan, H.K. The Second Industrial Revolution has Brought Modern Social and Economic Developments. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 6, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, H.K. Third Industrial Revolution Brings Global Development. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 7, 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Venturini, F. Intelligent technologies and productivity spillovers: Evidence from the Fourth Industrial Revolution. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2022, 194, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, J.; Kayser, I. Industry 5.0—Past, Present, and Near Future. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2023, 219, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.H.; Khalil, T.M. A Proposed Framework for Evaluating the Technological Readiness of Industries in X.0 Era. In Human-Centred Technology Management for a Sustainable Future; Zimmermann, R., Rodrigues, J.C., Simoes, A., Dalmarco, G., Eds.; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, E. Industry X.0: Realizing Digital Value in Industrial Sectors; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer, E.; Sovie, D. Reinventing the Product: How to Transform Your Business and Create Value in the Digital Age, 1st ed.; Kogan Page Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ferràs-Hernández, X.; Tarrats-Pons, E.; Arimany-Serrat, N. Disruption in the automotive industry: A Cambrian moment. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, R.N. Innovation The Attacker’s Advantage. In New York Summit Books—References; Scientific Research Publishing: Wuhan, China, 1986; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2806686 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail—Book; Faculty & Research—Harvard Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 1997; Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=46 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Valero, F. Impact of digital transformation on the automotive industry. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 162, 120343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czuchry, A.; Yasin, M.; Khuzhakhmetov, D.L. Enhancing Organizational Effectiveness through the Implementation of Supplier Parks: The Case of the Automotive Industry. J. Int. Bus. Res. 2009, 8, 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, W.; Iqbal, M. Economic, Social, and Environmental Determinants of Automotive Industry Competitiveness. J. Energy Environ. Policy Options 2022, 5, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Panwar, A.; Nepal, B.; Jain, R.; Yadav, O.P. Implementation of benchmarking concepts in Indian automobile industry—An empirical study. Benchmarking Int. J. 2013, 20, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogan, C.E.; English, M.J. Benchmarking for Best Practices: Winning Through Innovative Adaptation; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Camp, R.C. Benchmarking: The Search for Industry Best Practices that Lead to Superior Performance; Quality Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, G.H. Strategic Benchmarking: How to Rate Your Company’s Performance Against the World’s Best; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1993; Available online: https://books.google.com.eg/books/about/Strategic_Benchmarking.html?id=pffsAAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Harrington, H.J.; Harrington, J.S. High Performance Benchmarking: 20 Steps to Success; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- APQC. What Is Benchmarking? Available online: https://www.apqc.org/expertise/benchmarking (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Moriarty, J.P.; Smallman, C. En route to a theory of benchmarking. Benchmarking Int. J. 2009, 16, 484–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.; Banwet, D.K.; Shankar, R. A Delphi-AHP-TOPSIS based benchmarking framework for performance improvement of a cold chain. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 10170–10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munier, N.; Hontoria, E. Uses and Limitations of the AHP Method; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.springerprofessional.de/en/uses-and-limitations-of-the-ahp-method/18836858 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Wang, Y.-M.; Luo, Y. On rank reversal in decision analysis. Math. Comput. Model. 2009, 49, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yfanti, S.; Sakkas, N. Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) in the Era of Co-Creation. Appl. Syst. Innov. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görçün, Ö.F.; Mishra, A.R.; Aytekin, A.; Simic, V.; Korucuk, S. Evaluation of Industry 4.0 strategies for digital transformation in the automotive manufacturing industry using an integrated fuzzy decision-making model. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 922–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.; Ares, J.; Martínez, M.A.; Pazos, J.; Rodríguez, S.; Suárez, S.M. A fuzzy approach for solving a critical benchmarking problem. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2010, 24, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, C. Benchmarking of service quality with data envelopment analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 3761–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lei, L. How does industrial agglomeration affect internal structures of green economy in China? An analysis based on a three-hierarchy meta-frontier DEA and systematic GMM approach. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 206, 123560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahroudi, K. The application of data envelopment analysis methodology to improve the benchmarking process in the EFQM business model—Case study: Automotive industry of Iran. Iran. J. Optim. 2009, 3, 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Asmild, M.; Paradi, J.C.; Kulkarni, A. Using Data Envelopment Analysis in software development productivity measurement. Softw. Process Improv. Pract. 2006, 11, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.H.; Deif, A.M. Developing a Greenometer for green manufacturing assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 154, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.H.; Mansour, K.M.; Aly, M.F.; Khalil, T.M. Towards Industry X.0: A Consolidated Framework for Evaluating the Technological Readiness Levels of Automotive Industry. SSRN 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.S. Development of a Green Index for the Textile Industry: An Application in China. Ph.D. Thesis, Institute of Textiles and Clothing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China, 2011. Available online: https://theses.lib.polyu.edu.hk/handle/200/6117 (accessed on 14 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Institute of Knowledge Innovation and Invention. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).