Abstract

Low-altitude palaeoglaciation in Atlantic mountain regions provides important insights into past climatic conditions and moisture dynamics during the Last Glacial Cycle. This study presents the first quantitative reconstruction of palaeoglaciers in Serra da Cabreira (northwest Portugal), a mid-altitude granite massif located along the Atlantic fringe of the Iberian Peninsula. Detailed geomorphological mapping (1:14,000) and field surveys identified 48 glacial and periglacial landforms, enabling reconstruction of two small valley glaciers in the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys using GlaRe numerical modelling. The spatial distribution of palaeoglacial landforms shows a pronounced west–east asymmetry: periglacial features prevail on wind-exposed west-facing slopes, whereas glacial erosion and depositional landforms characterise the more protected east-facing valleys. The reconstructed glaciers covered 0.24–0.98 km2, with maximum ice thicknesses of 72–89 m. Equilibrium-line altitudes were estimated using AABR, AAR, and MELM methods, yielding consistent palaeo-ELA values of ~1020–1080 m. These results indicate temperature depressions of ~6–10 °C and enhanced winter precipitation associated with humid, Atlantic-dominated conditions. Comparison with regional ELA datasets situates Cabreira within a clear Atlantic–continentality gradient across northwest Iberia, aligning with other low-altitude maritime palaeoglaciers in the northwest Iberian mountains. The findings highlight the strong influence of the orographic barrier position, moisture availability, valley hypsometry, and structural controls in sustaining small, climatically sensitive glaciers at low elevations. Serra da Cabreira thus provides a key reference for understanding Last Glacial Cycle palaeoclimatic variability along the Western Iberian margin.

1. Introduction

Across mid-latitude mountain environments, palaeoglacial landforms preserve essential evidence of past climate variability and, at the same time, represent valuable geo-heritage features [1,2]. Beyond their heritage value, glacial landforms enable the reconstruction of former glaciers and the derivation of quantitative palaeoclimatic proxies [3,4,5,6,7]. Among these, the equilibrium-line altitude (ELA) is a key indicator of glacier mass balance and a robust proxy for palaeotemperature and palaeoprecipitation gradients [8,9,10]. Moreover, determining the timing and extent of palaeoglaciations improves regional and global interpretations of past atmospheric circulation patterns through the spatial analysis of former glacier distributions [1,2,11,12,13,14].

In the Iberian Peninsula, palaeoclimatic research has traditionally focused on mountains below 2000 m [15], where extensive ice masses during the Last Glacial Cycle (LGC) reshaped valley morphology and left a pronounced imprint on present-day landscapes [16,17,18,19,20,21]. While topographic factors such as elevation, aspect, and valley-floor elevations influenced glacier development, moisture availability was often the principal control on glacier formation and preservation in low-altitude ranges [22,23,24,25].

Modern precipitation patterns confirm the strong W–E and N–S moisture supply affecting the northwestern Iberian mountains, where the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) exerts a major influence, intensified by proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the exposure of these massifs to westerly flows [24,26]. During the LGC, the NAO configuration likely differed from the present, with a predominantly negative NAO-like pattern enhancing the advection of westerly moisture into southwestern Europe [27]. Such conditions would have favoured the growth of low-altitude glaciers with steep mass-balance gradients in Atlantic-facing ranges, pointing to a humid and climate-sensitive glaciation [19,28].

Low-altitude palaeoglaciers are critical for constraining the spatial variability of glaciation in Iberia [15,29], and the northwest Portugal mountains, which are located at the interface between Atlantic moisture sources and mid-latitude westerlies, were found to be highly sensitive to minor climatic shifts [30]. Their study allows testing whether topographic factors and continentality impact could compensate for limited altitude of relief [1]. These systems thus provide insights into glacier–climate transfer functions at mid-latitudes and refine palaeoclimatic observations for western Europe [15].

Despite their importance, quantitative palaeoglacial reconstructions remain scarce for low-altitude systems in northwest Portugal, particularly concerning palaeoglacier extent, palaeo-ELA estimates, and absolute chronologies [31,32,33,34]. Although previous work in Peneda–Gerês National Park (PNPG) has produced geomorphological maps, sedimentological analyses, and limited dating records [32,33,34,35,36], comparable studies in surrounding massifs, such as Serra da Peneda, Amarela, and Cabreira, likewise focus mainly on geomorphological and sedimentological descriptions [31,35,37,38,39]. However, these mountain systems still lack a coherent quantitative and chronological framework, and their broader palaeoclimatic significance within northwest Iberia remains poorly understood.

Serra da Cabreira (1262 m a.s.l.) is one of the few low-altitude massifs on the Atlantic fringe of northwest Portugal that preserves well-developed glacial landforms. Earlier studies mapped its glacial and periglacial features, particularly in the Gaviões Valley, and documented fracture-controlled granitic landforms [30,40,41,42]. More recent studies analysed moraine ridges and fluvioglacial fans using till-macrofabric and sedimentological approaches [39]. However, no quantitative palaeoglacier reconstruction has yet been undertaken for Serra da Cabreira, and its palaeo-ELA and associated palaeoclimatic implications remain unknown. Additionally, the integration of this massif into a regional palaeoclimatic framework is therefore crucial for understanding the dynamics of low-altitude glaciation across northwestern Iberia.

Considering this geomorphological setting, the present study develops the first quantitative palaeoglacier reconstruction for Serra da Cabreira. Our analysis is based on a detailed geomorphological map (1:14,000 scale), validated at 48 field sites containing key palaeoglacial landforms. The objectives are to: (I) refine the existing geomorphological map using new field observations and morphometric analyses; (II) reconstruct the former glaciers and derive palaeo-ELA values for the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys using the Altitude–Area Balance Ratio (AABR) and Accumulation Area Ratio (AAR) methods; and (III) compare the resulting palaeo-ELA values with those from other NW Iberian mountain ranges to integrate Serra da Cabreira into a regional palaeoclimatic context and clarify the dynamics of low-altitude glaciation across northwestern Iberia.

Study Area

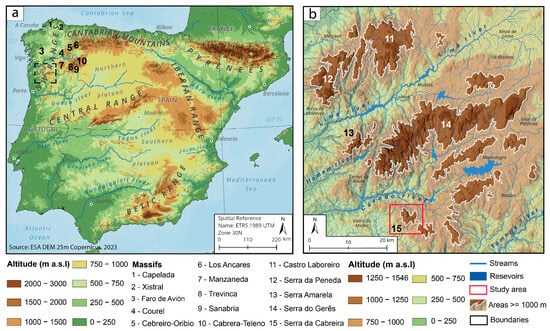

Northwest Iberia inland relief consists of a chain of mid-altitude massifs aligned SW–NE, broadly parallel to the Atlantic coast (Figure 1a). On the Spanish side, the Xistral (1055 m), Los Ancares (1967 m), Cebreiro (1470 m), Courel (1643 m) and Manzaneda (1784 m) massifs separate the Miño basin from the Sil basin [43,44]. Further east, the Trevinca (2127 m) and the Teleno (2188 m) ranges host the highest summits of the region [45] (Figure 1a). South of the border, the Portuguese mountains—Castro Laboreiro (994 m), Serra da Peneda (1416 m), Serra Amarela (1361 m), Serra do Gerês-Xurés (1523 m) and Serra da Cabreira (1262 m)—form a near-coastal orographic barrier that strongly influences atmospheric circulation and moisture delivery [24,31] (Figure 1b).

Figure 1.

Regional mountain framework of the northwest Iberia: (a) Major mountain ranges of the Iberian Peninsula and northwest Iberian mountains; (b) Northwest Portugal mountains.

The mountains of northwest Portugal are predominantly composed of fine- to coarse-grained granitic lithologies, which promote the development of characteristic granite landscapes including small highlands, plateaus, and structurally controlled elevated surfaces [46]. This lithological and geological setting is fundamental for understanding the formation and preservation of glacial accumulation landforms in the region [31]. Granite fabrics and fracture networks exert a strong control on landscape evolution, as pre-glacial freeze–thaw processes exploited these structural weaknesses, enhancing bedrock disintegration and facilitating subsequent glacial erosion [31].

The massif chain experiences a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Csb), with mean annual temperatures of 5 °C to 10 °C and annual precipitation between 2500 mm and 3500 mm [47,48,49,50]. These regional estimates are consistent with observations from a udometric station located at 830 m near Serra da Cabreira, which records a mean annual precipitation of 2728 mm for the period 1950–2001 (https://snirh.apambiente.pt/index.php?idRef=MTIyMw==&FILTRA_BACIA=107&FILTRA_COVER=920123704&FILTRA_SITE=920685974, accessed 11 November 2025).

Proximity to the Atlantic Ocean and the predominant SW–NE orientation of the ranges enhance orographic uplift of westerly air masses, intensifying precipitation on the windward slopes [51]. The massif exhibits a pronounced west–east climatic asymmetry: windward slopes are wetter and receive greater solar exposure, whereas leeward valleys are cooler, more shaded, and substantially drier. Such conditions favoured prolonged snow retention and promoted sheltered glaciation during the LGC [30].

Within this SW–NE-oriented orographic barrier, plateau-dominated massifs such as Peneda–Gerês contrast with the more dissected highlands of Cabreira and Amarela. These distinct geomorphological configurations strongly conditioned the extent, style, and preservation of Quaternary glaciations in northwest Portugal (Figure 1b) [31,33,52].

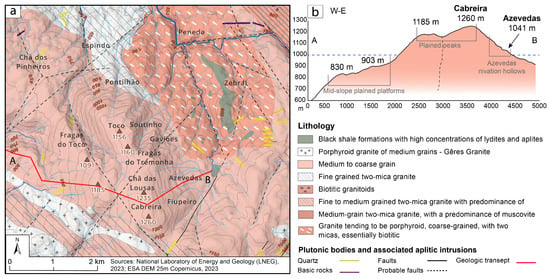

Serra da Cabreira (1262 m a.s.l.) forms the southernmost sector of the Portuguese orographic barrier (Figure 2a). The mountain rises from ~800 m to a series of summits including Chã das Lousas (1235 m), Fragas do Tremonha (1201 m), Toco (1156 m) and Chã do Prado (1185 m) (Figure 2a). A high-level surface between 1000 and 1260 m caps the range, while mid-slope planation surfaces are preserved between 750 and 950 m (Figure 2b). The massif is underlain by granite bedrock dissected by orthogonal SW–NE and NW–SE fault systems, which exert strong structural control on valley orientation, slope morphology, and the development of flat-topped highs and granitic domes (Figure 2b). These structures also promote the occurrence of pseudostratified outcrops and a deeply incised Quaternary drainage network, landscape features typical of northwest Portugal [30,40,41,42].

Figure 2.

Geological context of Serra da Cabreira: (a) Lithological map of the study area showing the orthogonal fault systems; glaciated areas are predominantly located in medium- to coarse-grained granite; (b) Cross-section profile illustrating the mid-slope planation surfaces and the small highlands between 1100 to 1260 m.

2. Materials and Methods

Remote sensing and spatial datasets were used to identify the most prominent glacial and periglacial landforms across Serra da Cabreira. A 10 m digital elevation model (DEM), resampled to 5 m, supported the geomorphological analysis and facilitated the interpretation of distinctive landform morphologies. Orthorectified aerial imagery from the National Geographic Information System (SNIG; https://snig.dgterritorio.gov.pt/, accessed 1 September 2024) for the years 2004, 2006, and 2018, with spatial resolutions of 1 m and 25 cm, was employed to refine landform mapping and assess surface characteristics. Geological context was derived from the National Geological Charts (Sheets 06-A and 06-C) provided by the National Laboratory for Energy and Geology (https://geoportal.lneg.pt/pt/, accessed 1 September 2024).

Fieldwork was carried out between 2021 and 2023. Geomorphological features were georeferenced using the Survey123 mobile application (https://survey123.arcgis.com/, accessed 20 October 2024), resulting in a dataset of 48 georeferenced observation points with associated photographic records. These field observations provided an essential layer of validation for the cartographic mapping. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) photographs were obtained using a Mavic 2 Pro (23 November 2022).

2.1. Geomorphological Mapping

A geomorphological map at 1:14,000 scale was produced using the geomorphological legend and geodatabase of the University of Lausanne, based on the CNRS RCP 77 system (https://www.unil.ch/igd/fr/home/menuinst/recherche/marges-environnement-paysages/la-legende-geomorphologique-de-lunil.html, accessed 23 October 2024) [53,54]. Landforms associated with glacial, periglacial, fluvioglacial, alluvial, and fluvial processes were mapped. The initial map was compiled in ArcGIS Pro 2.5 and subsequently refined and cartographically enhanced in Adobe Illustrator 2019.

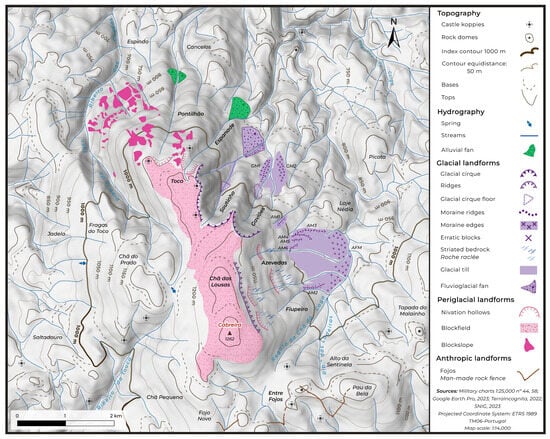

To produce the geomorphological map of Serra da Cabreira (Figure 3), datasets from previous studies were integrated were integrated with systematic field surveys [30,40,41]. These field observations were used to verify and refine landform interpretations, supported by a point shapefile containing the 48 georeferenced field records and associated photographs. The dataset served as a validation and completion layer during the final cartographic editing.

Figure 3.

Geomorphological map of Serra da Cabreira, showing the spatial distribution of the topographic, fluvial, glacial, periglacial and anthropogenic landforms, and illustrating their geomorphological relationships and interactions.

2.2. Palaeoglacial Modelling

For the palaeoglacial reconstruction, latero-frontal moraines marking the maximum glacier extent were used as geomorphological indicators of former glacier limits [55,56,57]. The reconstructed models for the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys were developed using the Glacier Reconstruction (GlaRe) toolbox (https://github.com/cageo/Pellitero-2015?tab=readme-ov-file, accessed on 10 May 2023) [57]. The GlaRe toolbox incorporates several key variables, including basal shear stress values, which provide valuable insights into different glacier types [58,59]. The implemented model in GlaRe applies the ice rheology theory to estimate ice thickness based on basal shear stress, glacial boundaries, and the topographic context [57,60]:

“…where is ice surface elevation, is basal shear stress (in Pa), is a shape factor, is ice density (~900 kg m−3), is the acceleration due to gravity (9.81 ms−2), is step length (in metres), H is ice thickness (in metres), and refers to the iteration (step) number.” [57].

Glacier reconstructions in GlaRe were based on a manually drawn flowline extending from the glacier snout to the cirque. Node intervals of 50 m were adopted, as smaller equidistance improves reconstruction accuracy [57]. For the glacial cirques of Serra da Cabreira, a value of 190,000 kPa was applied, as this provides the most realistic results for cirque-type glaciers [57,58,61,62]. The applied interpolation method was Topo to Raster to achieve a smooth glaciers surface.

2.3. Palaeo-ELA Calculations

The ELA represents the theoretical elevation at which annual ice accumulation equals annual ablation. Although a true steady-state ELA is seldom achieved in natural glacier systems, it remains a key climatic indicator because it reflects the balance between energy inputs and mass exchange on mountain glaciers [4,63,64].

Variations in accumulation and ablation regimes, driven by climatic conditions and modulated by topography, are expressed through shifts in the ELA, making it a powerful parameter for understanding glacier–climate interactions [5,9,22,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. Accurate ELA reconstructions therefore provide a robust means of inferring past temperature and precipitation regimes and are central to palaeoclimatic interpretations [5,72].

The ELA Calculation Toolbox incorporates several approaches for estimating glacier palaeo-ELAs, including the Median Glacier Elevation (MGE), Altitude Average (AA), Accumulation Area Ratio (AAR), and Area–Altitude Balance Ratio (AABR) methods [73] (https://github.com/cageo/Pellitero-2015, accessed on 10 May 2023). Among these, the AAR and AABR methods are considered the most robust for palaeoglacial reconstructions [22,73]. Reconstructed glacier extents and numerical ice-surface models provided the basis for applying both AAR and AABR to estimate palaeo-ELAs [57,74]. In addition, the Maximum Elevation of Lateral Moraines (MELM) method was used to facilitate comparison with previously published studies [75,76].

The AAR method estimates the ELA from the proportion of glacier area situated above the equilibrium line. Although widely applied, it does not account for variations in mass balance with altitude and may therefore underestimate the influence of key local controls such as topography [22,72,73]. In contrast, the AABR method incorporates glacier hypsometry and the altitudinal distribution of mass balance, explicitly reflecting differences in accumulation and ablation with elevation [71,73,75,77].

Because it integrates both climatic and topographic controls, the AABR method is particularly well suited for reconstructing maritime, topographically constrained, or climatically sensitive glaciers where strong precipitation and temperature gradients shape ice mass balance. The AABR-based ELA estimates were calculated by combining glacier hypsometry with the digital terrain model, applying the proposed formulation [72]:

“…where: is the Area-weighted mean altitude of the accumulation area; is the Area of accumulation; represents the Area-weighted mean altitude of the ablation area, and is the Area of ablation” [73].

AAR estimations for the palaeoglaciers of Serra da Cabreira were calculated using ratios typically applied to cirque- and valley-type glaciers, ranging from 0.40 to 0.65 [64,78,79]. For the AABR method, balance ratios (BR) between 1.5 and 2.1 were used, following values representative of mid-latitude maritime glaciers [80], while adopting 1.9 as the commonly applied central value.

Employing these ranges allows assessment of the sensitivity of the ELA estimates and generates an uncertainty envelope around the optimal statistical values for AAR (0.60 ± 0.05) and AABR (1.9 ± 0.81). This approach avoids methodological circularity by not constraining the reconstruction to a single fixed ratio.

2.4. Regional Palaeo-ELA of the NW Iberian Mountains

The reconstructed palaeo-ELA values provide a basis for interpreting past climatic conditions by converting former glacier equilibrium altitudes into two key palaeoclimatic variables: temperature depression (ΔT) and relative palaeoprecipitation (P) [4,9,10,67,81,82,83,84,85]. Both the AABR-based and AAR-based palaeo-ELA reconstructions were used to derive ΔT estimates and to infer precipitation patterns linked to the Atlantic moisture regime during the LGC. These palaeo-ELA-derived climatic parameters serve as geomorphological proxies of high palaeoclimatic significance.

To broaden the analysis and situate Serra da Cabreira within a representative regional context, previously published ELA–MELM datasets derived from standardised methodologies across the Iberian Peninsula were reviewed [15,31,43,44,86]. ELA–MELM values were examined for the studied massifs to explore the relationships between ELA, continentality, glaciated area, and glacier type, following approaches commonly applied in regional palaeoglacial analyses across Atlantic and Mediterranean mountain systems [3,15,31,43,86]. The compiled dataset included the MELM-derived ELA altitude, the approximate geographic coordinates (latitude and longitude) of each reconstructed site, the glacierized area (km2) associated with each ELA estimate, and the corresponding glacier typology [57,76,80]. The same procedure was applied to the Serra da Cabreira palaeoglaciers to allow direct comparison with the regional dataset (Supplementary Materials, Table S1).

The shortest distance from each massif to the nearest Atlantic or Cantabrian coastline was calculated to quantify continentality, expressed as the degree of maritime climatic influence affecting each glaciated region [3,67]. This parameter was then used to investigate spatial relationships between ELA altitude, palaeoglaciated area, and glacier morphology across the NW Iberian mountain systems [43,44].

3. Results

3.1. Landforms Distribution

The geomorphological map (Figure 3), produced at a scale of 1:14,000 and covering an area of 21 km2, uses distinct colour schemes for each geomorphological process, enhancing the visibility of morphogenetic contrasts across the landscape. It reveals a well-organised assemblage of glacial, periglacial, fluvial, and structural landforms developed within a granite massif shaped by orthogonal fault systems. Glacial features are concentrated in the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys, where cirques, till patches, moraine complexes, erratic blocks, and striated bedrock define two former valley-glacier systems.

The Gaviões Valley preserves the most extensive glacial record, with a succession of latero-frontal moraine ridges (AM1–AM6) marking distinct stages of glacier stillstand or retreat. In contrast, the Azevedas Valley contains a smaller but clearly organised cirque–valley assemblage with moraine arcs and fluvioglacial deposits sourced from the adjacent high surfaces of Chã das Lousas and Toco.

Beyond the glacial footprint, periglacial features, including nivation hollows, blockfields, and blockslope deposits, occur mainly on shaded slopes, reflecting frost-related processes active around and beyond former glacier margins. Taken together, the spatial distribution of glacial and periglacial landforms confirms the presence of two low-altitude palaeoglaciers at Serra da Cabreira and establishes a robust framework to reconstruct their geometries and derive quantitative palaeo-ELA estimates.

3.2. Geomorphological Survey

Field surveys allowed the identification of 48 glacial and periglacial landforms, including palaeoglacial cirques (Soutinho and Gaviões), nivation hollows, moraine ridges with associated till deposits, striated bedrock surfaces, triangulated megablocks of granitic erratics, blockfields, blockslope areas, and fan-shaped depositional features. The characteristic “bulldozing” effect of advancing ice produced well-defined lateral and frontal moraines, marked by abundant erratic boulders, many exceeding 1–2 m in diameter, which clearly delineate the principal glacial depositional zones.

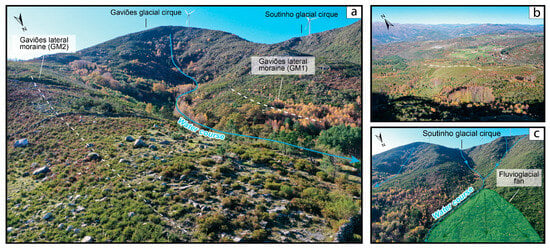

3.2.1. Soutinho Valley

The Soutinho valley preserves a prominent concave cirque and an almost a short developed U-shaped valley (Figure 4c). However, no lateral or terminal moraines have been identified to date. This absence is likely explained by intense torrential melt-out and fluvioglacial reworking, which would have removed or re-distributed primary glacial deposits and contributed to the formation of a large fan-shaped deposit at the valley piedmont. This deposit, associated with debris-flow and supraglacial melt-out processes [39], consists of unsorted and chaotic granitic clasts, some rounded and exceeding 1 m in diameter, embedded within a fine-grained, light-brown sediment matrix.

Figure 4.

Aerial views of the landforms in the Gaviões and Soutinho valleys: (a) Glacial cirque at the headwaters and lateral moraines in the lower section of the Gaviões valley; (b) Lateral moraine edge in the Gaviões valley; (c) Glacial cirque at the headwaters and fan-shaped deposit in the lower section of the Soutinho valley, associated with runoff and debris-flow processes (Aerial photographs acquired on 23 November 2022 with a Mavic 2 Pro UAV).

Given the lack of geomorphological indicators that constrain former glacier limits (such as lateral or latero-frontal moraines), the extent of the Soutinho palaeoglacier could not be reconstructed.

3.2.2. Gaviões Valley

The Gaviões valley is oriented northeastward and is structurally controlled by a southwest–northeast fracture zone. It contains a well-defined, armchair-shaped glacial cirque, a characteristic landform produced by intense bedrock glacial erosion [76] (Figure 4a). Within the valley, two lateral moraine deposits, GM1 and GM2, were identified at approximately 921 m a.s.l. GM1 extends for 266 m along the left side of the valley, whereas GM2, classified as an edge due to its gentle morphological profile, stretches for 427 m along the right side. GM2 is particularly distinctive, marked by large conical granitic boulders dispersed along the moraine.

3.2.3. Azevedas Valley

Glacial erosion along the Azevedas slope produced a smoothed surface with a gentle, curved profile and several small granitic platforms interpreted as nivation hollows which can also be understood as a glacial threshold, acting as local ice-accumulation basins during inner glacial stages and supporting short, confined glacier tongues (Figure 5a,b).

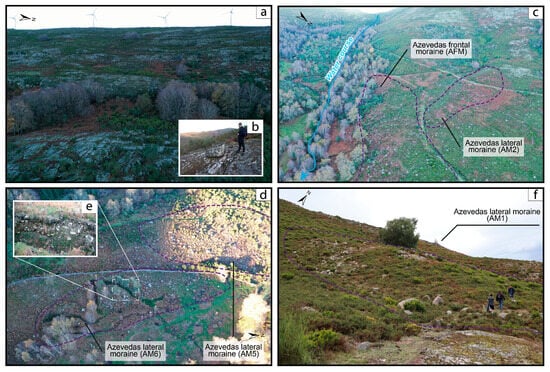

Figure 5.

Landforms in the Azevedas: (a) Aerial view of a mid-slope nivation hollow; (b) Polished granitic bedrock surface within the nivation hollow; (c) Aerial view of the lateral and frontal moraine ridges on the right side of the valley; (d) General aerial view of recessional glacial deposits; (e) Detailed view of a transverse talus within lateral moraine AM6; (f) Photographic record of a lateral moraine section exposed during water-extraction works (Aerial photographs acquired on 23 November 2022 with a Mavic 2 Pro UAV).

At the piedmont, a well-developed glacio-depositional field contains abundant erratic boulders and a series of clearly defined lateral and frontal moraine ridges (Figure 5c). The main frontal moraine (AFM) forms a south–north-trending ridge approximately 563 m long, positioned ~240 m downslope from the piedmont at ~945 m a.s.l., and is classified as a dump moraine [30,32]. Two lateral moraines (AM1 and AM2) converge with the AFM, delineating the maximum glacier extent. AM1 is 114 m long, located at ~1018 m a.s.l., and oriented southeast; AM2 extends 189 m between 1010 and 972 m a.s.l., oriented west–east. Four additional moraine ridges (AM3–AM6) occur upslope within the Azevedas glacio-depositional complex. Notably, AM6—partially exposed during hydrological works—offers promising potential for future sedimentological analysis (Figure 5e).

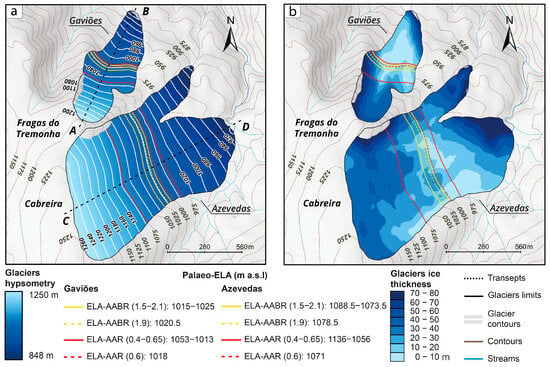

3.3. Palaeoglacial Reconstruction

The GlaRe modelling results (Table 1) indicate that during the LGC, the Azevedas and Gaviões palaeoglaciers corresponded to small valley glaciers with reconstructed areas of 0.98 km2 and 0.24 km2, respectively. Despite its smaller extent, the Gaviões glacier attained a greater maximum ice thickness (89 m) than Azevedas (72 m), although its total ice volume remained lower (11.4 hm3 compared with 38.1 hm3). Reconstructed glacier lengths from headwall to snout were 1.29 km for Azevedas and 0.90 km for Gaviões. The larger accumulation area and gentler altitudinal gradient of the Azevedas Valley appear to have favoured ice preservation and reduced ablation, whereas the steeper Gaviões Valley promoted higher ablation rates and a steeper mass-balance gradient (Figure 6a,b). In both cases, glacier initiation occurred below 1250 m within sheltered north-facing hollows controlled by the predominant N–S topography of Serra da Cabreira.

Table 1.

Global measurements obtained for Serra da Cabreira palaeoglaciers.

Figure 6.

Numerical modelling of the Cabreira palaeoglaciers: (a) Reconstructed ice-surface hypsometry. Dashed lines corresponds to the Glacio-topographic profiles (A-B; C-D) from Figure 7a,b; (b) Modelled ice-thickness distribution.

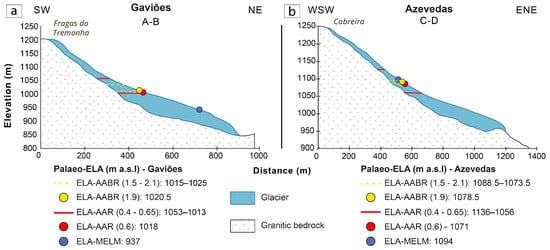

3.4. Palaeo-ELA Estimates

The reconstructed palaeo-ELAs were calculated for two small (<1 km2), undated palaeoglaciers using the numerical ice-surface models as the basis for AABR and AAR estimations (Table 2; Figure 6). Applying the selected ratio ranges (AABR = 1.5–2.1; AAR = 0.40–0.65) resulted in AABR-derived ELA thresholds of 1015–1025 m a.s.l. for Gaviões and 1073.5–1088.5 m a.s.l. for Azevedas. The corresponding AAR-derived values ranged from 1013–1053 m for Gaviões and 1056–1136 m for Azevedas (Figure 7a,b).

Table 2.

Palaeo-ELA estimations on both reconstructed numerical models.

Figure 7.

Glacio-topographic profiles of the Cabreira palaeoglaciers: (a) Transverse profile of the Gaviões palaeoglacier; (b) Transverse profile of the Gaviões palaeoglacier.

AAR-derived ELAs are consistently higher and more variable than AABR estimates, reflecting the AAR method’s lower sensitivity to glacier hypsometry and vertical mass-balance gradients. In contrast, the AABR method yields narrower and more physically coherent intervals, confirming its robustness for small, topographically confined palaeoglaciers [73,80]. Using the standard ratios (AABR = 1.9; AAR = 0.60), the resulting palaeo-ELA values are 1020.5 m a.s.l. (AABR) and 1018 m a.s.l. (AAR) for Gaviões, and 1078.5 m a.s.l. (AABR) and 1071 m a.s.l. (AAR) for Azevedas. These estimates compare well with the MELM-derived ELAs (937 m for Gaviões and 1094 m for Azevedas), supporting the reliability of the numerical modelling framework and the associated local mass-balance interpretation.

4. Discussion

The geomorphological mapping and numerical reconstructions presented in this study provide a comprehensive characterisation of low-altitude palaeoglaciation in Serra da Cabreira. Two small valley glaciers, developed in the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys, were mapped, each occupying structurally guided north-facing hollows and sustained by favourable topographic configurations [30]. Their reconstructed geometries, with areas of 0.24–0.98 km2 and ice thicknesses up to 89 m, illustrate the capacity of modest mid-altitude massifs to support LGC glaciation when conditions of snow accumulation and limited ablation prevail. The absence of moraines in the Soutinho valley further highlights the role of post-glacial reworking in modifying or erasing glacial signatures in such environments, underscoring the importance of integrating geomorphology with modelling approaches to identify former ice limits [57].

Multi-method equilibrium-line reconstructions (AABR, AAR, MELM) converge on palaeo-ELA values of ~1020–1080 m, implying temperature depressions of 6–10 °C. Such values align with the proposed regional estimates in previous studies [19,22] and suggest a moisture-rich palaeoclimate strongly influenced by Atlantic westerlies during the LGC [1].

Together, these findings point to a dominant climatic signal driven by enhanced winter snowfall and negative NAO-like atmospheric configurations, modulated by local topography that amplified snow retention and constrained glacier geometry [15,24].

4.1. Geological and Geomorphological Controls on Glaciation

Despite their modest dimensions, the Gaviões and Azevedas glaciers played an important role in re-shaping the Serra da Cabreira landscape. Their development was strongly conditioned by structural controls, with valley alignment guided by pre-existing fracture and fault networks that facilitated overdeepening by basal shear [31]. The vertical and stepped headwalls of the cirques of the Soutinho, Gaviões, and Azevedas illustrate the imprint of plucking on structurally weakened granite bedrock. The geomorphological pattern observed in Serra da Cabreira mirrors broader tendencies across the northwest Portuguese mountains, where topography, lithology, and hydrology jointly governed glacial behaviour during the LGC [31,33]. These massifs have long been described as “two-sided systems”, characterised by cold-climate landforms concentrated on sheltered leeward slopes and active freeze–thaw processes on the exposed windward flanks [33,87,88].

Within this framework, Serra da Cabreira, and the near glaciers of Serra Amarela, and Branda da Gémea exemplify confined valley glaciation, in which eastward snowdrift and sheltered topography favoured local ice accumulation [30,31,37]. By contrast, in massifs with extensive highlands such as Peneda and Gerês, palaeosurfaces acted as broad accumulation caps, feeding multiple outlet valleys and sustaining compound ice fields during the LGC [31,33,38]. The comparison underscores that, although climatic forcing was broadly uniform, the style and extent of glaciation were primarily controlled by topography specifically, by plateau continuity, relief amplitude, and exposure to prevailing Atlantic air masses [4,23,24,89].

Accordingly, two dominant glaciation types can be distinguished in northwest Portugal [76]: Scandinavian-type glaciation, represented by Peneda–Gerês–Xurés, where ice caps and compound cirques with dendritic outlets developed on high plateaus [31,33,37], and Valley-type glaciation, observed in Serra da Cabreira, Serra Amarela and Branda da Gémea valley, where isolated cirques functioned as primary accumulation basins feeding short valley tongues [31,38]. Together, these regional contrasts demonstrate that geological structure and relief configuration, rather than absolute altitude alone, governed the local expression of glaciation and the palaeo-ELA variability recorded across northwest Portugal.

4.2. Maritime Influence, Continentality and Palaeoglacial Equilibrium-Lines in NW Iberia

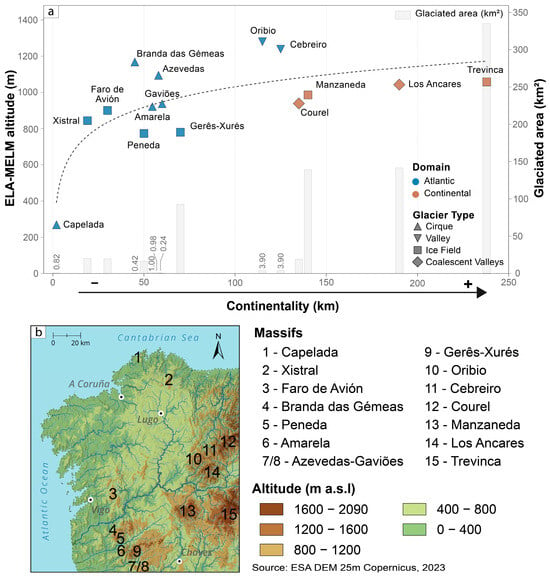

Considering the ELA-MELM values for the northwest Iberian mountains [31,43,44,86], the lowest palaeo-ELA values (≈270–900 m a.s.l.) correspond to the coastal and maritime-influenced ranges of Capelada, Faro de Avión, Xistral where abundant Atlantic precipitation sustained glacier equilibrium under limited temperature depression. Inland, ELAs progressively rise above 1000 m a.s.l. in Azevedas–Gaviões, Amarela, and Peneda–Gerês–Xurés, reaching maxima of 1200–1300 m a.s.l. in the Oribio–Cebreiro and Ancares–Trevinca systems.

At the same time, glaciated area increases markedly with continentality and massif altitude, suggesting that relief, plateau extent, and topographic confinement exerted a stronger influence on ice volume than ELA elevation alone (Figure 8a,b) [1,15,17]. In lower coastal ranges, such as Capelada or Azevedas, ice accumulation was restricted to cirques and short valley tongues, whereas in higher interior plateaus—Courel, Manzaneda, Los Ancares, Trevinca—ice fields and coalescent glaciers developed.

Figure 8.

LGC ELA Altitude and Glaciated Area vs. Distance from the Coastline and Glaciers Typology: (a) Plotted values of ELA-MELM and glaciated area per massif, distributed by distance since the coastline in the northwest Iberia classified as glacier type and type of continental effect; (b) Northwest Iberia geographical arrangement of the studied massifs.

The ELA–MELM values inferred for the studied massifs (Figure 8) reveal a clear continentality gradient, expressed by the logarithmic rise of ELAs with increasing distance from the Atlantic Ocean and Cantabrian Sea (Figure 8a). This pattern reflects the rapid inland depletion of maritime moisture sources and the previous described west–east asymmetric pattern on geomorphological development of moraines in the northwest Iberia [15,17,19,27,29].

During the LGC, mean annual air temperatures in Iberia were approximately 6–10 °C lower than those at present [19]. This broad cooling uniformly depressed ELAs, yet its local expression was modulated by both topography and continentality [22,23,24,25]. In northwest Portugal, the lower, maritime massifs maintained glacial balance under moderate cooling, as high precipitation compensated for smaller temperature drops. Further inland, however, higher-standing plateaus and elevated valley floors—notably in Los Ancares, and Trevinca—preserved altitude over longer distances, enhancing snow accumulation but requiring greater cooling to sustain equilibrium. Consequently, the observed logarithmic inland rise of ELA and the expansion of glaciated area reflect the combined effects of moisture depletion, orographic height, and thermal contrast on palaeoglacial equilibrium [4,5,15,19,31,67].

A broader European comparison shows that the northwest Iberian palaeo-ELA pattern lies at the low end of the continent-wide range [90]. In the Alps, LGC ELAs typically span 1200–1800 m, increasing toward the more continental northeastern sectors [91]. In the Carpathians, major ice fields in the Southern Carpathians reached ELAs of ~1000–1200 m, while the more continental Apuseni cirques lay above ~1600–1800 m [92]. Across the Pyrenees, Atlantic-facing catchments display ELAs of ~1200–1600 m, rising to >1800–2000 m in the Mediterranean east [93]. Similar west–east gradients characterise the Apennines, Balkans, and Tatra mountains, where maritime ranges maintain lower ELAs than interior massifs [90,94,95]. Within this framework, the northwest Iberian gradient, from ~270–900 m along the coast to ~1200–1300 m inland, forms one of the lowest maritime-influenced ELA range in Europe, reflecting the exceptional effectiveness of Atlantic moisture in sustaining low-elevation glacier equilibrium [17,19].

4.3. Study Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study provides the first quantitative reconstruction of the palaeoglaciers of Serra da Cabreira, several limitations must be acknowledged. Foremost is the absence of absolute chronological constraints for the mapped glacial landforms. Without dating, the reconstructed glacier geometries and palaeo-ELAs cannot yet be assigned to a specific phase of the LGC [1,2,11,12,13,14]. While the geomorphological characteristics strongly suggest a Late glacial or Last Glacial Maximum origin, this remains a working hypothesis. Future cosmogenic nuclide exposure dating or optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) analysis would be essential to establish a precise temporal framework [15,96,97,98].

A second limitation relates to the subtle topographic expression and partial reworking of glacial deposits, particularly in the Soutinho valley, where melt-out processes and post-glacial fluvial activity have obscured or removed moraine ridges. The resulting uncertainty in identifying maximum glacier limits restricts the reconstruction of one of the three potential glacier systems in Cabreira. High-resolution LiDAR, UAV-based photogrammetry, and sedimentological coring may help detect buried or degraded morainic features and refine valley-specific reconstructions [99,100].

Additionally, the small size of the Cabreira palaeoglaciers and their strong structural and hypsometric confinement introduce uncertainties in ELA reconstructions. Although the AABR, AAR and MELM methods converge on consistent values, small errors in mapping, hypsometry, or balance ratio selection may disproportionately influence ELA estimates for glaciers with limited altitudinal range [57]. More robust palaeoclimate inferences would benefit from applying spatially distributed mass-balance models, coupled with sensitivity tests using varying temperature and precipitation scenarios [9,10].

Lastly, this study highlights the need for broader regional integration. While we compare the Cabreira palaeoglaciers with other NW Iberian and European low-altitude systems, the regional dataset still lacks uniform reconstructions, consistent dating, and standardised ELA methodologies [20,31,37,38,43,44,45]. Future work should prioritise coordinated geomorphological mapping, chronological programmes, and numerical glacier modelling across the Portuguese–Galician border region. Such efforts will allow the development of a comprehensive regional model of Atlantic low-altitude glaciation and improve understanding of moisture-driven palaeoclimatic gradients during the LGC [1,7,15].

5. Conclusions

This study provides a quantitative reconstruction of the low-altitude palaeoglaciers of Serra da Cabreira, revealing two small, thin and topographically confined valley glaciers preserved in the Gaviões and Azevedas valleys. Their limited length, modest ice thickness, and restricted accumulation areas show that the Cabreira glaciation was highly sensitive to topographic controls, with glacial development constrained by north-facing cirques, fracture-guided valleys, and sheltered leeward settings.

Glacier extent and geometry were strongly controlled by topography, particularly the role of north-facing hollows and structurally guided valleys, which allowed glaciation at elevations significantly lower than northwest Iberian mountains.

Numerical modelling and multi-method ELA estimation (AABR, AAR, MELM) produce consistent palaeo-ELA values of ~1020–1080 m, indicating temperature depressions of 6–10 °C and enhanced winter snowfall under moisture-rich Atlantic conditions during the LGC.

These low ELAs align with patterns observed in other Atlantic-facing massifs of northwest Iberia and highlight the sensitivity of Cabreira’s small glaciers to precipitation-driven mass-balance regimes. When compared regionally, the Cabreira palaeoglaciers occupy an intermediate position within the Atlantic–continentality gradient, with ELA values comparable to those of other low-altitude European maritime glaciers.

Overall, the results demonstrate that the palaeoglaciation of Serra da Cabreira was driven by sustained Atlantic moisture supply within a structurally controlled granitic landscape. They provide an important key reference point for understanding the climatic sensitivity and geomorphological evolution of low-altitude mountain environments along the western Iberian margin during the LGC.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/quat8040071/s1, Table S1: Compiled dataset used for the continentality–ELA and glaciated area analysis in northwest Iberia [31,43,44,86]. The table compiles palaeo-ELAs (MELM) values, glaciated areas, glacier types, and domains for 15 palaeoglaciated massifs. Distances represent the shortest linear path from each massif to the Atlantic or Cantabrian coastline. These data were used to derive the logarithmic continentality trend shown in Figure 8 and to assess the relationship between ELA altitude, topographic setting, and ice extent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.F. and A.G.; methodology, E.F.; software, E.F.; validation, E.F., A.G. and J.C.; formal analysis, E.F. and A.G.; investigation, E.F. and A.G.; resources, E.F. and A.G.; data curation, E.F.; writing—original draft preparation, E.F. and A.G.; writing—review and editing, E.F., A.G. and J.C.; visualisation, E.F. and A.G.; supervision, A.G.; project administration, E.F., A.G.; funding acquisition, A.G. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.G. and J.C. received support from the Centre of Studies in Geography and Spatial Planning (CEGOT) (Grant 2016/19020-0), funded by national funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under the reference UIDB/04084/2020.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in the current study are not publicly archived due to size and format constraints, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the work of João Barreiros and Jorge Jesus, who contributed to this study throughout the field validation phases and the acquisition of aerial imagery using UAVs.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Hughes, P.D.; Woodward, J.C. Quaternary Glaciation in the Mediterranean Mountains: A New Synthesis; Geological Society: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, J.L.; Hughes, P.D.; Woodward, J.C. Heinrich Stadial aridity forced Mediterranean-wide glacier retreat in the last cold stage. Nat. Geosci. 2021, 14, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, P.D.; Braithwaite, R.J. Application of a degree-day model to reconstruct Pleistocene glacial climates. Quat. Res. 2008, 69, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, A.; Funk, M. Climate at the equilibrium line of glaciers. J. Glaciol. 1992, 38, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rea, B.R.; Pellitero, R.; Spagnolo, M.; Hughes, P.; Ivy-Ochs, S.; Renssen, H.; Ribolini, A.; Bakke, J.; Lukas, S.; Braithwaite, R.J. Atmospheric circulation over Europe during the Younger Dryas. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.; Ely, J.; Barr, I.; Boston, C. Section 3.4.9: Glacier Reconstruction. In Geomorphological Techniques; Cook, S., Clarke, L., Nield, J., Eds.; Online Edition; British Society for Geomorphology: London, UK, 2017; Available online: http://geomorphology.org.uk/sites/default/files/chapters/3.4.9_Glacier%20Reconstruction-min_0.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Palacios, D.; Hughes, P.D.; García-Ruiz, J.M.; Andrés, N. European Glacial Landscapes Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brugger, K.A.; Goldstein, B.S. Paleoglacier reconstruction and late Pleistocene equilibrium-line altitudes, southern Sawatch Range, Colorado. Spec. Pap. Geol. Soc. Am. 1999, 337, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oien, R.P.; Rea, B.R.; Spagnolo, M.; Barr, I.D.; Bingham, R.G. Testing the area-altitude balance ratio (AABR) and accumulation-area ratio (AAR) methods of calculating glacier equilibrium-line altitudes. J. Glaciol. 2021, 68, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohmura, A.; Boettcher, M. Climate on the equilibrium line altitudes of glaciers: Theoretical background behind Ahlmann’s P/T diagram. J. Glaciol. 2018, 64, 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.; Palacios, D.; Andrés, N.; Mora, C.; Vázquez Selem, L.; Woronko, B.; Soncco, C.; Úbeda, J.; Goyanes, G. Penultimate Glacial Cycle glacier extent in the Iberian Peninsula: New evidence from the Serra da Estrela (Central System, Portugal). Geomorphology 2021, 388, 107781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Mena, M.; Fernández-Fernández, J.M.; Tanarro, L.M.; Zamorano, J.J.; Palacios, D.; García, J.M.; Peña, J.L.J.L.; Martí, C.; Gómez, A.; Constante, A.; et al. Legenda. J. Maps 2013, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçar, N.; Yavuz, V.; Ivy-Ochs, S.; Reber, R.; Kubik, P.W.; Zahno, C.; Schlüchter, C. Glacier response to the change in atmospheric circulation in the eastern Mediterranean during the Last Glacial Maximum. Quat. Geochronol. 2014, 19, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, N.; Ghil, M.; Rousseau, D.D. Ocean circulation, ice shelf, and sea ice interactions explain Dansgaard–Oeschger cycles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11005–E11014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliva, M.; Palacios, D.; Fernández-Fernández, J.M.; Andrés, N.; Cacho, I.; Cañedo, D.G.; Carrasco, R.M.; Celis, A.G.; Domínguez-Cuesta, M.J.; García-Hernández, C.; et al. Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Janco, C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Alberti, A.; Valcárcel Díaz, M. Caracterización y distribución espacial del glaciarismo pleistoceno en el Noroeste de la Península Ibérica. In Las Huellas Glaciares las Montañas Españolas; Universidad de Santiago de Compostela: Galicia, Spain, 1998; pp. 17–54. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alberti, A.; Díaz, M.V.; Chao, R.B. Pleistocene glaciation in Spain. In Developments in Quaternary Sciences; Ehlers, J., Gibbard, P.L., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 2, Pt 1, pp. 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Alberti, A.; Rodríguez Guitán, M. Periglacial Forms and Block Deposits and Present Periglacial Phenomena in Sierras Septentrionales and Sierras Orientales of Galicia (NW Iberian Peninsula). In La Evolución del Paisaje en las Montañas del Entorno de los Caminos Jacobeos; Consellería de Relacións Institucionais e Portavoz do Goberno: Xunta de Galicia, Spain, 1993; ISBN 84-453-0885-8. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, M.; Palacios, D.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J.M.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, L.; Garcia-Ruiz, J.M.; Andres, N.; Carrasco, R.M.; Pedraza, J.; Pérez-Alberti, A.; Valcarcel, M.; et al. Late Quaternary glacial phases in the Iberian Peninsula. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 192, 564–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rodríguez, L.; Jiménez-Sánchez, M.; Domínguez-Cuesta, M.J.; González-Lemos, S. The glaciers around Lake Sanabria. In Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 335–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Vega, J.M.; Santos-González, J.; González-Gutiérrez, R.B.; Gómez-Villar, A. The glaciers of the Montes de León. In Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-González, J.; Redondo-Vega, J.M.; González-Gutiérrez, R.B.; Gómez-Villar, A. Applying the AABR method to reconstruct equilibrium-line altitudes from the last glacial maximum in the Cantabrian Mountains (SW Europe). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2013, 387, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, E.; González-Trueba, J.J.; Pellitero, R.; González-García, M.; Gómez-Lende, M. Quaternary glacial evolution in the Central Cantabrian Mountains (Northern Spain). Geomorphology 2013, 196, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigo, R.M.; Pozo-Vázquez, D.; Osborn, T.J.; Castro-Díez, Y.; Gámiz-Fortis, S.; Esteban-Parra, M.J. North Atlantic oscillation influence on precipitation, river flow and water resources in the Iberian Peninsula. Int. J. Climatol. 2004, 24, 925–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Moreno, J.I.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Morán-Tejeda, E.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Kenawy, A.; Beniston, M. Effects of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) on combined temperature and precipitation winter modes in the Mediterranean mountains: Observed relationships and projections for the 21st century. Glob. Planet. Change 2011, 77, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, E.; Lippold, J.; Gutjahr, M.; Frank, M.; Blaser, P.; Antz, B.; Fohlmeister, J.; Frank, N.; Andersen, M.B.; Deininger, M. Strong and deep Atlantic meridional overturning circulation during the last glacial cycle. Nature 2015, 517, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, S.; Diz, P.; Vautravers, M.J.; Pike, J.; Knorr, G.; Hall, I.R.; Broecker, W.S. Interhemispheric Atlantic seesaw response during the last deglaciation. Nature 2009, 457, 1097–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesje, A.; Jansen, E.; Birks, H.J.B.; Bjune, A.E.; Bakke, J.; Andersson, C.; Dahl, S.O.; Kristensen, D.K.; Lauritzen, S.E.; Lie, Ø.; et al. Holocene Climate Variability in the Northern North Atlantic Region: A Review of Terrestrial and Marine Evidence. In The Nordic Seas: An Integrated Perspective; American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 158, pp. 289–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Gibbard, P. Quaternary Glaciations Extent and Chronology Part I: Europe. Volume I. 2008. Available online: http://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle:QUATERNARY+GLACIATIONS+EXTENT+AND+CHRONOLOGY#1 (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Daveau, S.; Devy-Vareta, N. Gelifraction, nivation et glaciation d’abri de la Serra da Cabreira (Portugal). Actas 1a Reunião do Quaternário Ibérico Atas 1985, 1, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alberti, A. The glaciers of the Peneda, Amarela, and Gerês-Xurés massifs. In Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Santos-González, J.; Blanca González-Gutiérrez, R.; Assunção, A. Timing of deglaciation in the Serra do Gerês Mountains (NW Portugal National Park) based on AMS dating. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Programs 2023, 55, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, B. A Glaciação Plistocénica da Serra do Gerês-Vestígios Geomorfológicos e Sedimentológicos. Finisterra 1999, XXXV, 39–68. [Google Scholar]

- Coudé-Gaussen, G. Les Serras da Peneda et do Gerês; Memórias do Centro de Estudos Geográficos; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.; Cunha, L.; Vieira, A.; Bento-Gonçalves, A. Genesis of the Alto Vez Glacial Valley Pleistocene Moraines, Peneda Mountains, Northwest Portugal Caracterização E Génese Das Moreias Plistocénicas Do Vale Glaciário Do Alto Vez, Serra Da Peneda, Noroeste De Portugal; Associação Portuguesa de Geomorfólogos (APGEOM): Porto, Portugal, 2013; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.; Santos-González, J.; Redondo-Vega, J.M. Till-Fabric analysis and origin of late Quaternary moraines in the Serra da Peneda Mountains, NW Portugal. Phys. Geogr. 2015, 36, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, E.; Gomes, A.; Costa, J. Cartografia geomorfológica glaciária e delimitação da paleoglaciação da Serra Amarela. Comun. Geológicas 2025, 112, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, E.; Gomes, A.; Pérez-Alberti, A. Pleistocene Glaciations of the Northwest of Iberia: Glacial Maximum Extent, Ice Thickness, and ELA of the Soajo Mountain. Land 2023, 12, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Gomes, A.; Costa, J.; Figueira, E. Till Macrofabric and Grain Size Analysis of Glacial Diamictons in the Serra Da Cabreira Mountains, NW Portugal. Geol. Soc. Am. Programs 2022, 54, 373413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Gonçalves, A.B. Vestiges of the Quaternary glaciation in Cabreira Montain (North-West Portugal). Estud. Quaternário/Quat. Stud. 2001, 4, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, A.; Gonçalves, A.; Almendra, R. Vestígios De Glaciação Da Serra Da Cabreira–Cartografia Geomorfológica De Pormenor Com Recurso a Tecnologias De Geoprocessamento. 2005, 10. Available online: http://apgeo.pt/files/docs/CD_X_Coloquio_Iberico_Geografia/pdfs/094.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D.; Rodrigues, L. Pseudoestratificação granítica na Serra da Cabreira: Geoformas com influência climática e estrutural. Assoc. Port. Geomorfólogos 2005, 3, 215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alberti, A.; Valcarcel, M. The glaciers in Eastern Galicia. In Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 375–395. [Google Scholar]

- Valcarcel, M.; Pérez-Alberti, A. The glaciers in Western Galicia. In Iberia, Land of Glaciers: How the Mountains Were Shaped by Glaciers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alberti, A.; Gómez-Pazo, A. Glaciers Landscapes during the Pleistocene in Trevinca Massif (Northwest Iberian Peninsula). Land 2023, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Pereira, D.I. The Granite and Glacial Landscapes of the Peneda-Gerês National Park. In Landscapes and Landforms of Portugal. World Geomorphological Landscapes; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Estatal de Meteorología Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino; Instituto de Meteorologia de Portugal. Atlas Climático Ibérico: Temperatura do Ar e Precipitação (1971–2000)/Iberian Climate Atlas: Air Temperature and Precipitation (1971/2000). 2011. Available online: http://www.ipma.pt/resources.www/docs/publicacoes.site/atlas_clima_iberico.pdf%0A (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Daveau, S. Répartition et Rythme des Précipitations au Portugal; Centro de Estudos Geográficos: Lisbon, Portugal, 1977; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and future köppen-geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2007, 11, 1633–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Angulo, D.; Trigo, R.M.; Cortesi, N.; González-Hidalgo, J.C. The influence of weather types on the monthly average maximum and minimum temperatures in the Iberian Peninsula. Atmos. Res. 2016, 178–179, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coude, G. La glaciation du Minho au Pleistocène récent dans son contexte paléogéographique local et régional. Géologie Méditerranéenne 1978, 5, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambiel, C.; Maillard, B.; Ragamey, B.; Martin, S.; Kummert, M.; Schoeneich, P.; Pellitero-Ondicol, R.; Reynard, E. The ArcGIS Version of the Geomorphological-Mapping Legend of the University of Lausanne. 2013. Available online: https://wp.unil.ch/hmg/research/geomorphological-mapping/unil-geomorphological-legend/ (accessed on 2 January 2023).

- Taillefer, F. Autres cartes géomorphologiques: Cartographie géomorphologique. In Travaux de la RCP 77; Service de Documentation et de Cartographie Géographiques: Paris, France, 1972; pp. 487–488. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, M.; Oliva, M.; Vieira, G.; Lopes, L.F. Geomorphology of the Aran Valley Upper Garonne Basin Central Pyrenees. J. Maps 2022, 18, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, R.; Fernández-Fernández, J.M.; Campos, N.; Serrano, E.; Pisabarro, A. Late Pleistocene climate of the northern Iberian Peninsula: New insights from palaeoglaciers at Fuentes Carrionas (Cantabrian Mountains). J. Quat. Sci. 2019, 34, 342–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, R.; Rea, B.R.; Spagnolo, M.; Bakke, J.; Ivy-Ochs, S.; Frew, C.R.; Hughes, P.; Ribolini, A.; Lukas, S.; Renssen, H. GlaRe, a GIS tool to reconstruct the 3D surface of palaeoglaciers. Comput. Geosci. 2016, 94, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, W.S.B. The sliding velocity of Athabasca Glacier, Canada. J. Glaciol. 1970, 9, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Weertman, J. Shear Stress at the base of a rigidly rotating cirque glacier. J. Glaciol. 1971, 10, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, D.H.; Hollin, J.T. Numerical reconstructions of valley glaciers and small ice caps. In The Last Great Ice Sheets; Denton, G.H.H., Ed.; Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1981; pp. 207–220. [Google Scholar]

- Rea, B.R.; Evans, D.J.A. Quantifying climate and glacier mass balance in north Norway during the Younger Dryas. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 246, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, J.F. The Mechanics of Glacier Flow. Cavendish Lab. Camb. 1952, 1, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.C. Equilibrium-line altitudes of late Quaternary glaciers in the Southern Alps, New Zealand. Quat. Res. 1975, 5, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, G.; Kerschner, H.; Patzelt, G. Methodische Untersuchungen über die Schneegrenze in alpinen Gletschergebieten. Zeitschrift für Gletscherkd. und Glazialgeol. 1978, 12, 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, M.F.; Post, A.S. Recent Variations in Mass Net Budgets of Glaciers in Western North America. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 1962, 58, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, R.J.; Muller, F. On the parameterization of glacier equilibrium line altitude. In Proceedings of the Riederalp Workshop, Riederalp, Switzerland, 17–22 September 1978; IAHS-AISH, 1980; Volume 126, pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, S.C. Snowline depression in the tropics during the last glaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2001, 20, 1067–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cogley, J.G.; Hock, R.; Rasmussen, L.A.; Arendt, A.A.; Bauder, A.; Braithwaite, R.J.; Jansson, P.; Kaser, G.; Möller, M.; Nicholson, L.; et al. Glossary of Glacier Mass Balance and Related Terms; IHP-VII Te.; International Association of Cryospheric Sciences: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, R.G. The status of research on glaciers and global glacier recession: A review. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2006, 30, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.A.; Thackray, G.; Anderson, R.S.; Briner, J.; Kaufman, D.; Roe, G.; Pfeffer, W.; Yi, C. Integrated research on mountain glaciers: Current status, priorities and future prospects. Geomorphology 2009, 103, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, D.I.; Lehmkuhl, F. Mass balance and equilibrium-line altitudes of glaciers in high-mountain environments. Quat. Int. 2000, 65–66, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmaston, H. Estimates of glacier equilibrium line altitudes by the Area × Altitude, the Area × Altitude Balance Ratio and the Area × Altitude Balance Index methods and their validation. Quat. Int. 2005, 138–139, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, R.; Brice, R.R.; Spagnolo, M.; Bakke, J.; Ivy-Ochs, S.; Hughes, P.; Lukas, S.; Ribolini, A. A GIS tool for automatic calculation of glacier equilibrium-line altitudes. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 82, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitero, R. Evolución finicuaternaria del glaciarismo en el macizo de Fuentes Carrionas (Cordillera Cantábrica), propuesta cronológica y paleoambiental lateglacial. Cuaternario Geomorfol. 2013, 31, 45–72. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/CUGEO/article/view/20179 (accessed on 20 March 2023).

- Bahr, D.B. Estimation of Glacier Volume and Volume Change by Scaling Methods. In Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- Benn, D.I.; Evans, D.J.A. Glaciers & Glaciation; Hodder Education: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, C.M.; Lukas, S.; Carr, S.J. A Younger Dryas plateau icefield in the Monadhliath, Scotland, and implications for regional palaeoclimate. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2015, 108, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakke, J.; Nesje, A. Equilibrium Line Altitude (ELA). In Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers; Singh, V.P., Singh, P., Haritashya, U.K., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, Z.; László, P. Size specific steady-state accumulation-area ratio: An improvement for equilibrium-line estimation of small palaeoglaciers. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2010, 29, 2781–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rea, B.R. Defining modern day Area-Altitude Balance Ratios (AABRs) and their use in glacier-climate reconstructions. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009, 28, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, A.N.; Anderson, B.M.; Pierrehumbert, R.T. Reconstructing Climate from Glaciers. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2017, 45, 649–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, R.G. Mountain Weather and Climate, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez, M.; Colhoun, E.A. A note on air temperature lapse rates on Mount Wellington, Tasmania. Pap. Proc.-R. Soc. Tasmania 1986, 120, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnelle, K.B. Atmospheric Diffusion Modeling. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 679–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, N.B.; Kirkpatrick, J.B. Air temperature lapse rates and cloud cover in a hyper-oceanic climate. Antarct. Sci. 2020, 32, 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Alberti, A. El patrimonio de origen glaciar de la Serra da Capelada (Geoparque mundial de la Unesco Cabo Ortegal, Galicia, Península Ibérica). Cuaternario y Geomorfol. 2017, 31, 45–72. Available online: https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/CUGEO/article/view/102466 (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Vieira, G. Combined numerical and geomorphological reconstruction of the Serra da Estrela plateau icefield, Portugal. Geomorphology 2008, 97, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudé-Gaussen, G. Les Serras da Peneda et do Gerês (Minho-Portugal): Formes et Formations D’origine Froide en Milieu Granitique. Ph.D Thesis, Université Paris-I-Panthéon-Sorbonne, Paris, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Coudé, A.; Coudé-Gaussen, G.; Daveau, S. Nouvelles observations sur la glaciation des montagnes du Nord-Ouest du Portugal. Cuad. Lab. Xeol. Laxe 1983, 5, 381–393. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, P.D.; Allard, J.; Woodward, J.; Pope, R. Glacial landscapes of the Balkans. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Ivy-Ochs, S.; Monegato, G.; Reitner, J.M. Glacial landscapes of the Alps. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urdea, P.; Ardelean, F.; Ardelean, M.; Onaca, A. Glacial landscapes of the Romanian Carpathians. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Gunnell, Y.; Calvet, M.; Reixach, T.; Oliva, M. Glacial landscape of the Pyrenees. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasadni, J.; Kłapyta, P.; Makos, M. Glacial landscapes of the Tatra Mountains. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribolini, A.; Giraudi, C. The Italian Peninsula. In European Glacial Landscapes: Maximum Extent of Glaciations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Alberti, A.; Díaz, M.V.; Peter Martini, I.; Pascucci, V.; Andreucci, S. Upper pleistocene glacial valley-junction sediments at Pias, Trevinca Mountains, NW Spain. Geol. Soc. Spec. Publ. 2011, 354, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunai, T.J. Cosmogenic Nuclides-Principles, Concepts and Applications in the Earth Surface Sciences; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016; Volume 5, Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cosmogenic-nuclides/403A3823168B0B721CB2D8ED10177122 (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Siame, L.L.; Bourlès, D.L.; Brown, E.T. In Situ-Produced Cosmogenic Nuclides and Quantification of Geological Processes, 1st ed.; The Geological Society of America: Boulder, CO, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ewertowski, M.W.; Evans, D.J.A.; Roberts, D.H.; Tomczyk, A.M. Glacial geomorphology of the terrestrial margins of the tidewater glacier, Nordenskiöldbreen, Svalbard. J. Maps 2016, 12, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śledź, S.; Ewertowski, M.W.; Piekarczyk, J. Applications of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) surveys and Structure from Motion photogrammetry in glacial and periglacial geomorphology. Geomorphology 2021, 378, 107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).