A Multi-Analytical Archaeometric Approach to Chalcolithic Ceramics from Charneca do Fratel (Portugal): Preliminary Insights into Local Production Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

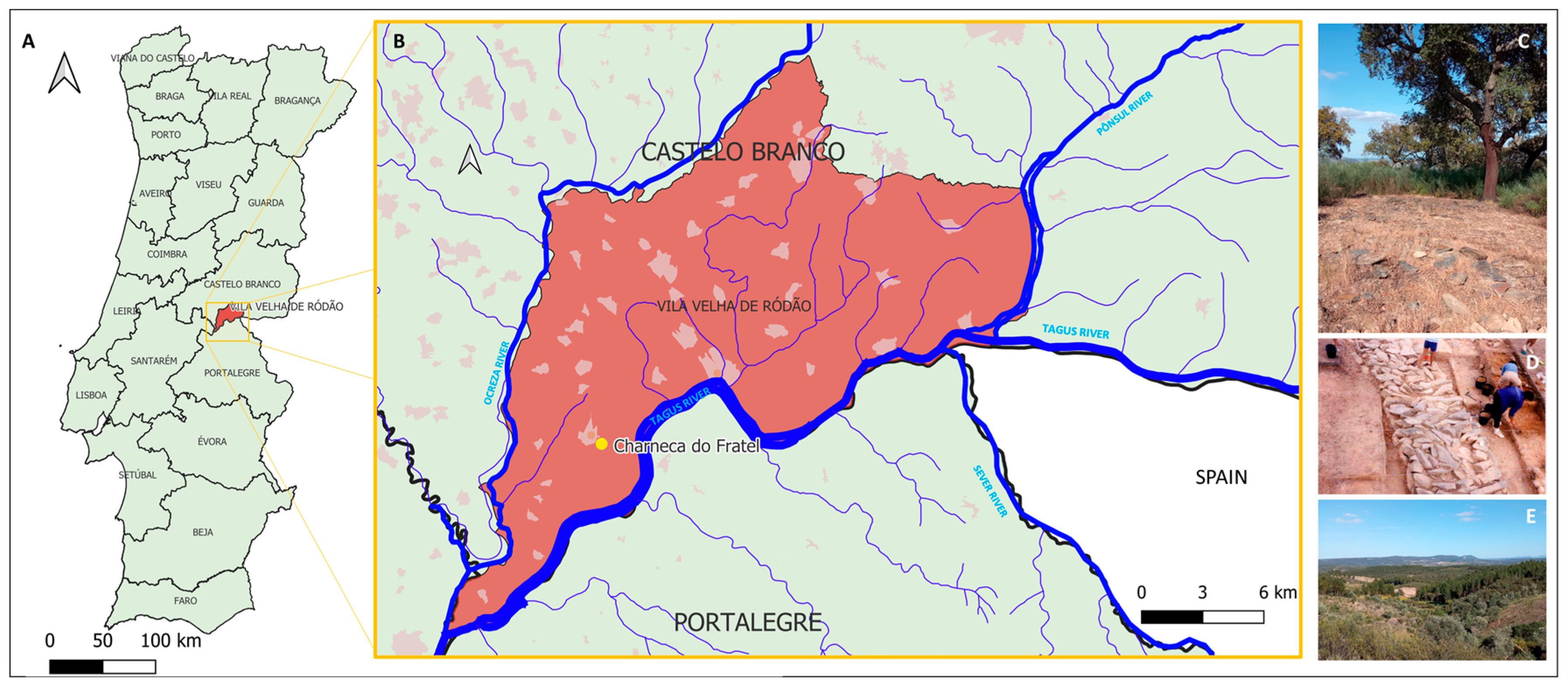

1.1. Charneca do Fratel Geological and Archaeological Setting

1.2. Research Aim

2. Materials and Methods

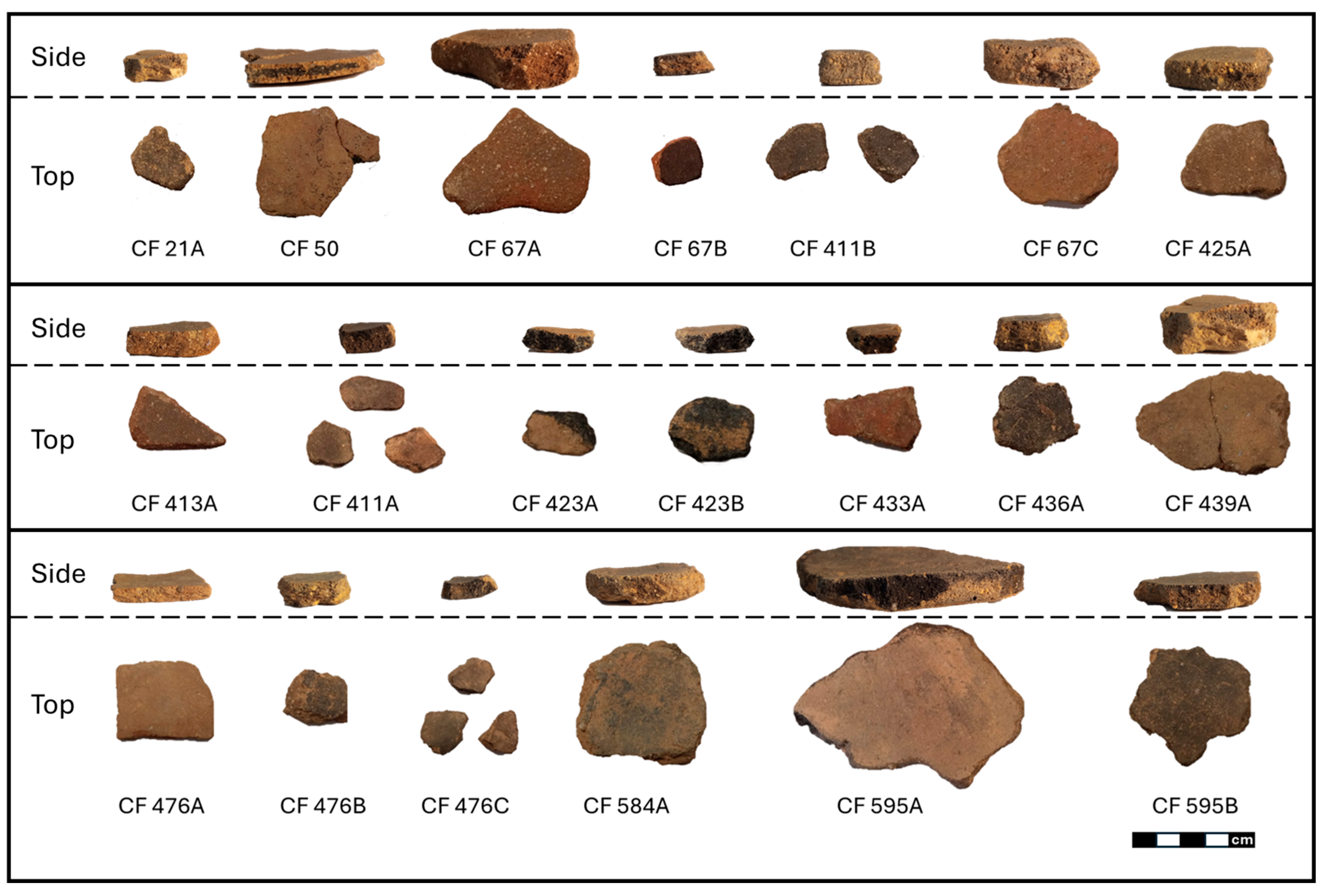

2.1. Samples

2.2. Sample Preparation and Equipment

3. Results and Discussion

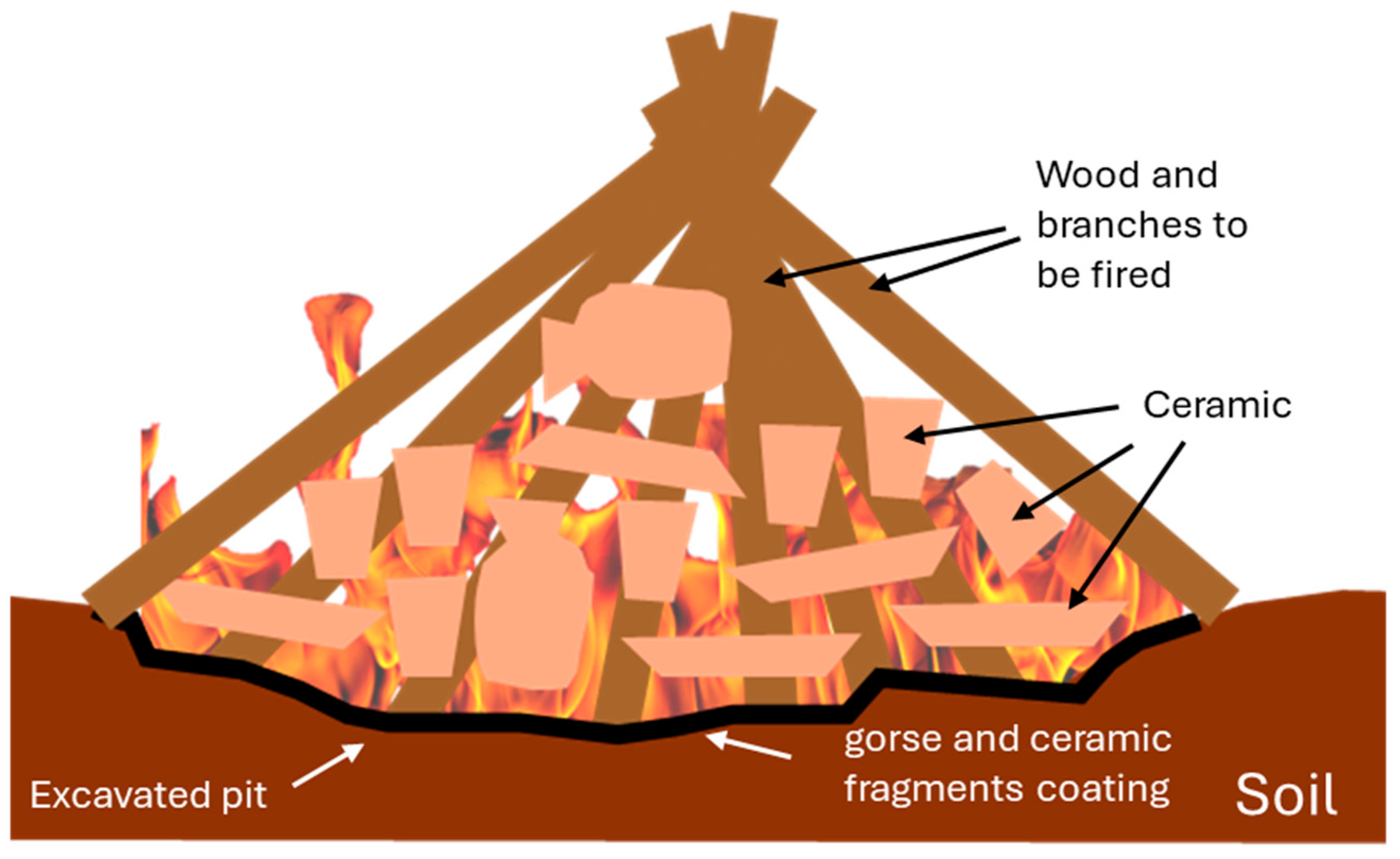

3.1. Textural Analysis

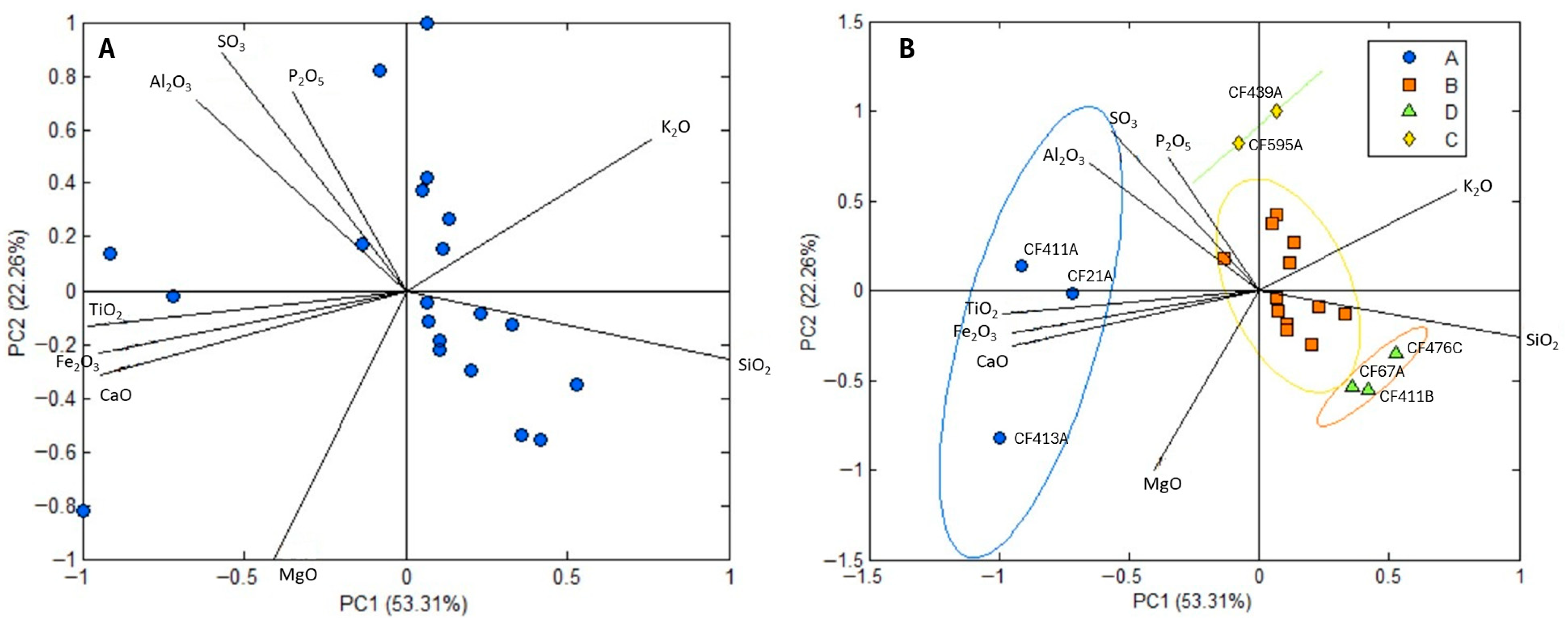

3.2. Chemical–Elemental Analysis

3.3. Mineralogical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pearce, M. The “Copper Age”—A History of the Concept. J. World Prehistory 2019, 32, 229–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J.L. Pré-História de Portugal; Editorial Verbo: Lisbon, Portugal, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, G. La Cerámica con Decoración Acanalada y Bruñida en el Contexto Pre-Campaniforme del Calcolítico de la Extremadura Portuguesa: Nuevos Aportes a la Comprensión del Proceso de Producción de Cerámicas en la Prehistoria Reciente de Portugal; BAR International Series; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, S. Colónias, fortificações, lugares monumentalizados. Trajectória das concepções sobre um tema do Calcolítico peninsular. Rev. Fac. Let. 1998, 11, 447–545. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, H.J. The Secondary Products Revolution: The past, the present and the future. World Archaeol. 2010, 42, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, J. Searching for the Turning Point to Bronze Age Societies in Southern Portugal: Topics For A Debate. In Between the 3rd and the 2nd Millennia BC: Exploring Cultural Diversity and Change in Late Prehistoric Communities; Lopes, S., Gomes, S., Eds.; Archaeopress: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 82–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tavares da Silva, C.; Soares, J. Contribuição para o conhecimento dos povoados calcolíticos do Baixo Alentejo e Algarve: 43 anos em perspectiva. In Fogo e Morte. Sobre o Extremo sul no 3° Milénio a.n.e.; Sousa, A.C., Ed.; Câmara Municipal de Loulé: Loulé, Portugal, 2024; pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R. Cerâmica Calcolítica da Região de Lisboa: Caracterização Arqueométrica de Cerâmica Pré-Histórica. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa: Almada, Portugal, 2022. Available online: https://run.unl.pt/handle/10362/150112 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Amaro, G. Continuidade e evolução nas cerâmicas Calcolíticas da Estremadura (um estudo arqueométrico das cerâmicas do Zambujal). Estud. Arqueol. Oeiras 2010, 18, 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, M.I.; Valera, A.C.; Lago, M.; Prudêncio, M.I. Proveniência e tecnologia de produção de cerâmicas nos Perdigões. Vipasca Arqueol. História 2007, 2, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Amaro, G.; Anunciação, C. Reproducción experimental del proceso de producción de cerámicas calcolíticas de la Extremadura portuguesa. Bol. Arqueol. Exp. 2010, 8, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaro, G. How to (re)make a “prehistoric pot”? A small synthesis based on the study of chalcolithic pottery of Zambujal (Torres Vedras, Portugal) and also on the current manufacture of mapuche pottery (Lumaco, Chile). Oppidum 2020, 16, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, R.C.; Veiga, J.P.; Monge Soares, A. Characterization of Chalcolithic Ceramics from the Lisbon Region, Portugal: An Archaeometric Study. Heritage 2022, 5, 2422–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, R.C.; Veiga, J.P.; Monge Soares, A. Cerâmicas calcolíticas de Vila Nova de São Pedro (Região de Lisboa)—Caracterização Textural e Química. Estud. Arqueol. Oeiras 2021, 29, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira Ferreira, L.F.; Barros, L.; Ferreira Machado, I.; Pereira, M.F.C.; Casimiro, T.M. An archaeometric study of a Late Neolithic cup and coeval and Chalcolithic ceramic sherds found in the São Paulo Cave, Almada, Portugal. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2020, 51, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, A.; Beltrame, M.; Mirão, J.; Mateus, J. Archaeometric study of the Proto-historic ceramics from the settlement of the Avecasta Cave (Ferreira do Zêzere, Portugal). Estud. Quaternário 2022, 22, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Macías, J.A.; Martins, A.; Fernández, O.R. Primeiras evidências de mineração do cobre em Aljustrel—Um cadinho Calcolítico proveniente do Castelo. Vipasca Arqueol. História 2013, 4, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fratel. Grande Enciclopédia Portuguesa e Brasileira; Editorial Enciclopédia: Lisboa, Portugal, 1950; Volume 11, p. 804. [Google Scholar]

- Charneca. Grande Enciclopédia Portuguesa e Brasileira; Editorial Enciclopédia: Lisboa, Portugal, 1950; Volume 6, p. 616. [Google Scholar]

- Houaiss, A.; Villar, M.; de Mello Franco, F.M.; de Lexicografia, I.A.H.; Charneca. Dicionário Houaiss da Língua Portuguesa; Temas e Debates: Lisbon, Portugal, 2001; Volume II. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, J. O Povoado da Charneca do Fratel e o Neolítico Final/Calcolítico da Região Ródão-Nisa—Notícia Preliminar. Alto Tejo 1988, 2, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Caninas, J.C.; Henriques, F.; Osório, M. Ocupação do Território de Fratel (Vila Velha de Ródão) na Pré-História recente: Ensaio de análise espacial. Sci. Antiq. 2017, 1, 177–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, C.; De Carvalho, H.; Peres, A.; Fernandes, A.P. Carta Geológica de Portugal na Escala 1/50 000—Notícia Explicativa da Folha 28-B NISA; Direcção Geral de Minas e Serviços Geológicos: Lisboa, Portugal, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Vilaça, R. Registos e Leituras da Pré-história recente e da Proto-história antiga da Beira Interior. In Proceedings of the Pré-história Recente da Península Ibérica; ADECAP—Associação para o Desenvolvimento da Cooperação em Arqueologia Peninsular: Oporto, Portugal, 2000; pp. 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Soares, J. Transformações Sociais Durante o III Milénio AC no Sul de Portugal. O Povoado do Porto das Carretas; EDIA, DRACAL and MAEDS: Lisboa, Portugal, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira da Silva, F.A. Mamoa da Charneca das Canas. Fratel. Câmara Municipal de Vila Velha de Ródão. 1991. Available online: https://www.vaiver.com/castelobranco/mamoa-da-charneca-das-canas/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Orton, C.; Hughes, M. Pottery in Archaeology, 2nd ed.; Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva, A.S.; Coutinho, M.L.; Tavares da Silva, C.; Soares, J.; Duarte, S.; Veiga, J.P. Archaeological Ceramic Fabric Attribution Through Material Characterisation—A Case-Study from Vale Pincel I (Sines, Portugal). Heritage 2025, 8, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, E.; Silva, R.J.; Araújo, M.F.; Fernandes, F.M.B. Multifocus Optical Microscopy Applied to the Study of Archaeological Metals. Microsc. Microanal. 2013, 19, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepard, A.O. Ceramics for the Archaeologist; Carnegie Institution of Washington publication; Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington, DC, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Little, G.A. The Technology of Pottery Production in Northwestern Portugal During the Iron Age; Unidade de Arqueologia da Universidade do Minho; Cadernos de Arqueologia, no. 4; Universidade do Minho: Braga, Portugal, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, A.M.; Woods, A. Prehistoric Pottery for the Archaeologist; Leicester University Press: Leicester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Summerhayes, G.R. Losing Your Temper: The Effect of Mineral Inclusions on Pottery Analyses. Archaeol. Ocean. 1997, 32, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilikoglou, V.; Vekinis, G.; Maniatis, Y.; Day, P.M. Mechanical performance of quartz-tempered ceramics: Part I, strength and toughness. Archaeometry 1998, 40, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffer, Z.; Winefordner, J.D.; Dovichi, N.J. Archaeological Chemistry; Chemical Analysis: A Series of Monographs on Analytical Chemistry and Its Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-471-91515-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzo, E. Ceramic technology. How to reconstruct the firing process. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bonis, A.; Cultrone, G.; Grifa, C.; Langella, A.; Leone, A.P.; Mercurio, M.; Morra, V. Different shades of red: The complexity of mineralogical and physico-chemical factors influencing the colour of ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 8065–8074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritan, L.; Nodari, L.; Mazzoli, C.; Milano, A.; Russo, U. Influence of firing conditions on ceramic products: Experimental study on clay rich in organic matter. Appl. Clay Sci. 2006, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, K.J.D.; Cardile, C.M. A57Fe Mössbauer study of black coring phenomena in clay-based ceramic materials. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 2937–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Lisboa, J.V. Argilas comuns em Portugal Continental: Ocorrência e características. In Proveniência de Materiais Geológicos: Abordagens Sobre o Quaternário de Portugal; Dinis, P., Gomes, A., Monteiro-Rodrigues, S., Eds.; APEQ: Coimbra, Portugal, 2014; pp. 135–164. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10316/32068 (accessed on 17 October 2025).

- Sánchez Ramos, S.; Bosch Reig, F.; Gimeno Adelantado, J.; Yusá Marco, D.; Doménech Carbó, A. Application of XRF, XRD, thermal analysis, and voltammetric techniques to the study of ancient ceramics. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2002, 373, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murad, E.; Wagner, U. Clay and clay minerals: The firing process. Hyperfine Interact. 1998, 117, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holakooei, P.; Tessari, U.; Verde, M.; Vaccaro, C. A new look at XRD patterns of archaeological ceramic bodies. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2014, 118, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laita, E.; Bauluz, B. Mineral and textural transformations in aluminium-rich clays during ceramic firing. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 152, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordán, M.M.; Boix, A.; Sanfeliu, T.; de la Fuente, C. Firing transformations of cretaceous clays used in the manufacturing of ceramic tiles. Appl. Clay Sci. 1999, 14, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristály, F.; Kelemen, É.; Rózsa, P.; Nyilas, I.; Papp, I. Mineralogical investigations of medieval brick samples from Békés County (SE Hungary). Archaeometry 2012, 54, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, M.J.; Dias, M.I.; Coroado, J.; Rocha, F. Firing Tests on Clay-Rich Raw Materials from the Algarve Basin (Southern Portugal): Study of Mineral Transformations with Temperature. Clays Clay Miner. 2010, 58, 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritan, L. Ceramic abandonment. How to recognise post-depositional transformations. Archaeol. Anthropol. Sci. 2020, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathossi, C.; Pontikes, Y.; Tsolis-Katagas, P. Mineralogical differences between ancient sherds and experimental ceramics: Indices for firing conditions and Post-burial alteration. In Proceedings of the 12th International Congress Patras, Patras, Greece, 19–22 May 2010; pp. 856–865. [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi, M.P.; Messiga, B.; Duminuco, P. An approach to the dynamics of clay firing. Appl. Clay Sci. 1999, 15, 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, C.; Hoeck, V. Firing-induced transformations in Copper Age ceramics from NE Romania. Eur. J. Mineral. 2011, 23, 937–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouahabi, M.E.; Daoudi, L.; Hatert, F.; Fagel, N. Modified Mineral Phases during Clay Ceramic Firing. Clays Clay Miner. 2015, 63, 404–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cultrone, G.; Rodriguez-Navarro, C.; Sebastian, E.; Cazalla, O.; De La Torre, M.J. Carbonate and silicate phase reactions during ceramic firing. Eur. J. Mineral. 2001, 13, 621–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Texture | Friability | Surface Colour | Core Colour | Thickness (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF21A | Coarse | Semi-compact | Grey (N3) | Light brown (10YR 4/2) | 1.014 ± 0.066 |

| CF50 | Coarse | Semi-compact | Light brown (5YR 5/6) | Dark grey (N2) | 0.569 ± 0.058 |

| CF67A | Very coarse | Compact | Reddish brown (2.5YR 4/4) | Reddish (2.5YR 4/8) | 1.322 ± 0.120 |

| CF67B | Coarse to average | Semi-friable | Grey (N2) | Reddish brown (10R 4/10) | 0.722 ± 0.036 |

| CF67C | Very coarse | Friable | Light brown (10YR 7/6) | Light brown (10YR 7/6) | 1.453 ± 0.063 |

| CF411A | Average | Semi-friable | Grey (N2) | Light brown (10YR 5/6) | 0.828 ± 0.008 |

| CF411B | Coarse | Compact | Grey (10YR 5/2) | Grey (10YR 5/2) | 1.108 ± 0.061 |

| CF413A | Very coarse | Compact | Brown (10YR 4/6) | Brown (10YR 5/6) | 0.961 ± 0.043 |

| CF423A | Coarse | Very friable | Light brown (10YR 6/6) | Black (N1) | 1.028 ± 0.050 |

| CF423B | Coarse | Very friable | Light brown (10YR 6/8) | Black (N1) | 0.965 ± 0.051 |

| CF425A | Very coarse | Compact | Brown (10YR 5/4) | Grey (10YR 3/4) | 0.980 ± 0.053 |

| CF433A | Coarse to average | Semi-friable | Reddish brown (10R 3/6) | Black (N1) | 0.858 ± 0.083 |

| CF436A | Very coarse | Friable | Grey (N2) | Light grey (10YR 3/2) | 1.116 ± 0.008 |

| CF439A | Very coarse | Friable | Brown (10YR 5/6) | Brown (10YR 3/4) | 1.780 ± 0.082 |

| CF476A | Average | Compact | Light brown (10YR 6/6) | Reddish (2.5YR 5/6) | 0.655 ± 0.044 |

| CF476B | Very coarse | Friable | Grey (10YR 5/2) | Brown (10YR 4/4) | 1.123 ± 0.011 |

| CF476C | Average | Semi-friable | Light grey (N4) | Grey (N2) | 0.800 ± 0.037 |

| CF584A | Very coarse | Friable | Brown (10YR 5/4) | Dark brown (10YR 3/4) | 1.487 ± 0.043 |

| CF595A | Coarse | Semi-compact | Light brown (10YR 6/6) | Black (N1) | 0.998 ± 0.047 |

| CF595B | Coarse | Compact | Grey (N3) | Brown (10YR 3/4) | 0.758 ± 0.083 |

| Sample | Area of NPE (%) | Size 1 (mm) | Geometry 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CF21A | 20.88 | 0.43 ± 0.39 | Sub-angular |

| CF50 | 22.37 | 0.28 ± 0.18 | Sub-rounded |

| CF67A | 21.17 | 0.38 ± 0.22 | Sub-angular |

| CF67B | 18.72 | 0.18 ± 0.11 | Sub-rounded |

| CF67C | 19.54 | 0.37 ± 0.31 | Angular |

| CF411A | 17.48 | 0.49 ± 0.28 | Angular |

| CF411B | 19.79 | 0.28 ± 0.09 | Sub-angular |

| CF413A | 21.26 | 0.24 ± 0,09 | Sub-rounded |

| CF423A | 13.71 | 0.47 ± 0.43 | Sub-rounded |

| CF423B | 12.54 | 0.23 ± 0.12 | Sub-rounded |

| CF425A | 22.72 | 0.37 ± 0.20 | Sub-angular |

| CF433A | 20.33 | 0.30 ± 0.22 | Sub-angular |

| CF436A | 13.90 | 0.35 ± 0.16 | Sub-rounded |

| CF439A | 25.06 | 0.23 ± 0.09 | Sub-angular |

| CF476A | 19.86 | 0.33 ± 0.29 | Sub-rounded |

| CF476B | 16.38 | 0.23 ± 0.15 | Sub-rounded |

| CF476C | 23.07 | 0.50 ± 0.44 | Sub-rounded |

| CF584A | 17.04 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | Sub-angular |

| CF595A | 12.20 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | Sub-rounded |

| CF595B | 15.82 | 0.26 ± 0.09 | Sub-angular |

| TOTAL (avg.) | 18.7 ± 3.7 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | - |

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | CaO | TiO2 | P2O5 | MgO | SO3 | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF 411A | 52.80 ± 0.30 | 23.10 ± 0.30 | 14.40 ± 0.10 | 3.24 ± 0.05 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 2.19 ± 0.04 | 1.27 ± 0.03 | 1.29 ± 0.05 | 0.22 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| CF 413A | 52.84 ± 0.30 | 23.02 ± 0.30 | 15.01 ± 0.10 | 1.82 ± 0.04 | 2.20 ± 0.04 | 1.77 ± 0.04 | 1.34 ± 0.03 | 1.77 ± 0.06 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.03 |

| CF 21A | 53.51 ± 0.30 | 24.10 ± 0.20 | 13.10 ± 0.20 | 3.28 ± 0.08 | 1.93 ± 0.06 | 1.58 ± 0.04 | 1.18 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.04 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.08 |

| CF 433A | 57.59 ± 0.30 | 21.80 ± 0.30 | 13.80 ± 0,10 | 4.15 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.58 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| CF 439A | 61.11 ± 0.30 | 25.50 ± 0.30 | 4.93 ± 0.06 | 5.21 ± 0.07 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 0.60 ± 0.02 | 1.48 ± 0.04 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| CF 67C | 61.43 ± 0.30 | 23.31 ± 0.30 | 6.66 ± 0.07 | 4.98 ± 0.07 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 1.03 ± 0.03 | 1.40 ± 0.40 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.04 |

| CF 595A | 62.15 ± 0.30 | 23.12 ± 0.20 | 5.79 ± 0.10 | 4.17 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.03 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 2.57 ± 0.05 | 0.66 ± 0.03 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.04 |

| CF 476B | 62.90 ± 0.30 | 22.50 ± 0.30 | 6.83 ± 0.08 | 4.30 ± 0.06 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 1.32 ± 0.05 | <LOD | 0.17 ± 0.03 |

| CF 595B | 63.63 ± 0.30 | 21.61 ± 0.30 | 8.05 ± 0.08 | 3.98 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.02 | 0.96 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.26 ± 0.05 |

| CF 50 | 63.74 ± 0.30 | 22.72 ± 0.30 | 7.41 ± 0.08 | 3.84 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.80 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.03 |

| CF 423B | 64.02 ± 0.30 | 21.71 ± 0.20 | 7.26 ± 0.08 | 4.02 ± 0.06 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.03 | 1.09 ± 0.03 | 0.64 ± 0.04 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| CF 423A | 65.15 ± 0.30 | 21.38 ± 0.20 | 6.78 ± 0.08 | 3.93 ± 0.06 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.03 | 0.93 ± 0.03 | 0.70 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| CF 476A | 66.14 ± 0.30 | 19.31 ± 0.20 | 5.97 ± 0.07 | 3.87 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 2.70 ± 0.05 | 0.79 ± 0.40 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.23 ± 0.04 |

| CF 584A | 66.99 ± 0.30 | 17.10 ± 0.20 | 8.73 ± 0.08 | 3.47 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.77 ± 0.03 | 1.54 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.02 |

| CF 436A | 67.36 ± 0.30 | 21.09 ± 0.20 | 6.29 ± 0.07 | 3.39 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.02 | <LOD | 0.90 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 |

| CF 67B | 68.11 ± 0.30 | 19.30 ± 0.20 | 6.27 ± 0.07 | 3.65 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.71 ± 0.03 | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.02 |

| CF 67A | 68.11 ± 0.30 | 18.65 ± 0.20 | 5.49 ± 0.07 | 4.76 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 1.40 ± 0.05 | <LOD | 0.54 ± 0.03 |

| CF 425A | 68.86 ± 0.30 | 18.99 ± 0.20 | 5.42 ± 0.07 | 4.45 ± 0.06 | 0.17 ± 0.01 | 0.66 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.02 | 0.92 ± 0.04 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| CF 411B | 71.02 ± 0.30 | 17.11 ± 0.20 | 5.40 ± 0.07 | 4.35 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.03 | <LOD | 1.06 ± 0.05 | <LOD | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| CF 476C | 72.06 ± 0.30 | 16.89 ± 0.20 | 3.94 ± 0.06 | 4.88 ± 0.06 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 1.08 ± 0.04 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.08 ± 0.02 |

| Feldspars | Iron Oxide | Clay Minerals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Quartz | Albite | Microcline | Orthoclase | Magnetite | Illite | Montmorilonite |

| CF 411A | ++++ | +++ | - | - | ++ | - | - |

| CF 413A | ++++ | +++ | - | - | ++ | - | - |

| CF 21A | ++++ | - | +++ | - | - | - | ++ |

| CF 433A | ++++ | ++ | - | - | + | ++ | - |

| CF 439A | ++++ | - | +++ | - | + | + | - |

| CF 67C | ++++ | - | +++ | - | ++ | ++ | - |

| CF 595A | ++++ | +++ | +++ | - | ++ | - | - |

| CF 476B | ++++ | - | ++ | - | - | +++ | - |

| CF 595B | ++++ | - | ++ | - | - | ++ | - |

| CF 50 | ++++ | - | +++ | - | + | - | - |

| CF 423B | ++++ | - | +++ | - | ++ | + | - |

| CF 423A | ++++ | - | ++ | - | + | - | - |

| CF 476A | ++++ | - | - | ++ | + | - | - |

| CF 584A | ++++ | - | - | ++ | + | - | - |

| CF 436A | ++++ | ++ | - | - | + | ++ | - |

| CF 67B | ++++ | +++ | - | - | ++ | - | - |

| CF 67A | ++++ | +++ | - | - | + | - | - |

| CF 425A | ++++ | ++ | ++ | - | + | - | - |

| CF 411B | ++++ | +++ | +++ | - | ++ | ++ | - |

| CF 476C | ++++ | - | +++ | - | + | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saraiva, A.S.; Coutinho, M.L.; Soares, J.; Tavares da Silva, C.; Caninas, J.C.; Veiga, J.P. A Multi-Analytical Archaeometric Approach to Chalcolithic Ceramics from Charneca do Fratel (Portugal): Preliminary Insights into Local Production Practices. Quaternary 2025, 8, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040072

Saraiva AS, Coutinho ML, Soares J, Tavares da Silva C, Caninas JC, Veiga JP. A Multi-Analytical Archaeometric Approach to Chalcolithic Ceramics from Charneca do Fratel (Portugal): Preliminary Insights into Local Production Practices. Quaternary. 2025; 8(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaraiva, Ana S., Mathilda L. Coutinho, Joaquina Soares, Carlos Tavares da Silva, João C. Caninas, and João Pedro Veiga. 2025. "A Multi-Analytical Archaeometric Approach to Chalcolithic Ceramics from Charneca do Fratel (Portugal): Preliminary Insights into Local Production Practices" Quaternary 8, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040072

APA StyleSaraiva, A. S., Coutinho, M. L., Soares, J., Tavares da Silva, C., Caninas, J. C., & Veiga, J. P. (2025). A Multi-Analytical Archaeometric Approach to Chalcolithic Ceramics from Charneca do Fratel (Portugal): Preliminary Insights into Local Production Practices. Quaternary, 8(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/quat8040072