Abstract

The rubber industry uses phthalates as plasticizers in technical rubber goods due to their excellent compatibility, low volatility and cost-effectiveness. Growing concerns over their environmental and health impact have driven the search for sustainable alternatives. Bio-based plasticizers offer a promising solution due to their renewable nature, non-toxicity and biodegradability. This study explores the feasibility of replacing a conventional petroleum-based Di-Iso-Nonyl Phthalate (DINP) with a bio-based phthalate-free plasticizer, Aurora PHFree, in Nitrile Butadiene Rubber (NBR) compounds filled with semi-reinforcing carbon black N660. Aurora PHFree achieves similar processing behavior, cure characteristics, and mechanical properties as well as aging performance by using only half of the amount by weight of DINP. This efficiency is attributed to the improved plasticizing effects, which enable polymer chain mobility, without altering the overall crosslink density, as well as the enhanced dispersion of the carbon black (CB) fillers of the rubber compounds. This research supports the development of more sustainable rubber materials and contributes to reducing the dependence on fossil-based materials while maintaining high-quality standards.

1. Introduction

Plasticizers are considered essential additives in rubber compounding as they improve processability, flexibility and filler dispersion [1]. In polar rubber compounds, such as nitrile butadiene rubber (NBR), plasticizers with moderate to high polarity are preferred to ensure good compatibility and to maintain key properties such as oil and fuel resistance conferred by the rubber matrix [1,2]. Traditionally, phthalate esters such as Di-Octyl Phthalate (DOP), Di-Iso-Nonyl Phthalate (DINP), and Di-Iso-Decyl Phthalate (DIDP) are widely used due to their efficient plasticization, cost-effectiveness and excellent compatibility with NBR [3].

However, increasingly strict regulations have raised health and environmental concerns in the use of the traditional petroleum-based plasticizers. DINP has been classified as a Category 2 carcinogen under the EU Classification, Labelling and Packaging (CLP) Regulation and is listed on California’s Proposition 65 due to potential cancer risks. Although its toxicity is considered lower than that of DOP, restrictions on its use in toys and childcare articles reflect rising safety standards [4,5]. These growing concerns have accelerated the transition to safer alternative plasticizers. Adipate esters, such as Di-Octyl Adipate (DOA) and Di-Iso-Nonyl Adipate (DINA) and sebacate esters, such as Di-Octyl-Sebacate (DOS) provide better low-temperature performance due to its linear molecular structures, making them ideal for applications like seals and gaskets in refrigeration systems [2,3]. Additionally, chlorinated paraffins, which contain polar chlorine groups, enhance oil resistance and flame retardancy, serving as effective secondary plasticizers in technical rubber goods [6]. While polymeric plasticizers offer improved resistance to volatility and aging, their costs are higher.

In addition to regulatory demands, increasing sustainability goals have driven the search for bio-based alternatives derived from renewable sources. Various vegetable oils and their derivatives have been investigated for their plasticizing effect [7]. Epoxidized Soybean Oil (ESO) and N-phenyl-p-phenylenediamine modified ESO (pA-m-ESO) were studied as replacements for DOP in carbon black filled NBR compounds. Results have shown that ESO can reach similar processing characteristics to DOP, including mixing energy, Mooney viscosity and cure behavior, unlike the compound containing pA-m-ESO. However, the mechanical performance is inferior to those with conventional DOP [8]. Moreover, Epoxidized Ester of Glycerol formal derived from Soybean Oil (EESO) and Epoxidized Ester of Glycerol formal derived from Canola Oil (EECO) were compared to the traditional petroleum-based Treated Distillate Aromatic Extract (TDAE) oil and synthetic plasticizer Mesamoll® (LANXESS, Cologne, Germany). The results showed that both EESO and EECO provided similar tensile strength, improved low-temperature flexibility and better tear strength compared to the traditional plasticizers [9]. In a recent study, castor oil-based plasticizers were evaluated against DOP, showing enhanced mechanical performance. Specifically Epoxy Acetylated Castor Oil (EACO) and Epoxy Benzoyl Castor Oil (EBCO) can replace DOP as plasticizers in NBR compounds used in fields that require high mechanical properties, aging resistance and thermal stability [10]. These studies report improvements in processing behavior and mechanical properties together with reductions in toxicity and environmental impact. Despite these advances, the development and optimization of new bio-based plasticizers remain an active and essential research field in the rubber industry.

This study explores Aurora PHFree, a newly developed bio-based plasticizer derived from cashew nutshell, as a potential replacement to the conventional phthalate-based plasticizer, DINP, in nitrile butadiene rubber (NBR) compounds. Aurora PHFree is derived from food industry waste stream. Hence, it is not in competition with food production. In this study, an NBR model compound filled with semi-reinforcing furnace carbon black (grade N660) was used. Although Aurora PHFree has been developed as a sustainable plasticizer, its effects on processability and the performance of final rubber products have not yet been systematically investigated. Therefore, this study evaluates its effects on the mixing behavior, as well as on the properties of both the uncured and vulcanized rubber compounds. The aim is to elucidate the role and impact of this bio-based plasticizer in rubber formulations.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

The compounds studied in this work were prepared using commercially available Nitrile Butadiene Rubber (NBR) KRYNAC 3345 F (33% acrylonitrile content) (Arlanxeo, La Wantzenau, France) and carbon black N660 (Birla Carbon, Hanover, Germany) as semi-reinforcing filler. Zinc oxide (ZnO) (Umicore zinc Chemicals, Angleur, Belgium) and stearic acid (Edenor ST1 GS, Emery Oleochemicals GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany) were added as activators. Sulfur (Zolfindustria, Trecate, Italy), 2-2′-Di-thio-bis(benzothiazole) (MBTS) and Tetra-Benzyl-Thiuram Disulfide (TBZTD) (Caldic B.V., Rotterdam, The Netherlands) were used as curatives. Vulkanox HS TMQ (Trimethyl-dihydroquinoline) (Lanxess, Mannheim, Germany) as anti-degradant. Di-Iso-Nonyl Phthalate (DINP) (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) and Aurora PHFree (Ergon International Inc., Antwerp, Belgium) as plasticizers. According to the supplier, Aurora PHFree contains 98% bio-based carbon in accordance with ASTM D6866 [11], confirming its renewable origin and supporting its classification as sustainable plasticizers. The main physical characteristics of DINP and Aurora PHFree are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Main physical characteristics of DINP and Aurora PHFree.

2.2. Compound Preparation

The formulations used for the preparation of the rubber compounds are summarized in Table 2. The base formulation was kept constant for all samples: NBR 3345 F (100 phr), N660 carbon black (75 phr), zinc oxide (5 phr), stearic acid (1 phr), TMQ (2.5 phr), sulfur (0.3 phr), MBTS (2 phr), and TBzTD (5.6 phr). The only variable was the type and amount of plasticizers. The weight in Table 2 is given in “phr”, parts per hundred rubber (by weight).

Table 2.

NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree as plasticizers in 1:1 replacement ratio.

In the first mixing stage, the rubber compounds were mixed in an internal mixer (Brabender Plasticorder 350 S, Duisburg, Germany) for 10 min with a fill factor of 0.7, an initial temperature of 50 °C and a rotor speed of 50 rpm following the procedure shown in Table 3. The second mixing stage was carried out in an open two-roll mill (Polymix 80T, Servitec Maschinenservice GmbH, Wustermark, Germany) at room temperature as the starting temperature. The curing agents were gradually added in small portions along the nip while the compound was repeatedly passed through the rolls, followed by cutting and folding until homogeneous dispersion of the curing package was obtained.

Table 3.

Mixing procedure of the studied compounds in an internal mixer (stage 1).

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP)

The Hansen Solubility Parameter values (δD, δP, δH and δtotal) for the plasticizers and polymer were calculated using the Hansen Solubility Parameter in Practice (HSPiP) software 6th edition (version 6.1.02).

2.3.2. Mooney Viscosity

The Mooney viscosity of the rubber compounds was evaluated using a Mooney Viscometer (Premier MV, Alpha Technologies, Hudson, OH, USA) at 100 °C using the large rotor (L-type). After a 1 min preheating period with the rotor at rest, the measurement was performed for 4 min under rotation at 2.0 rpm. The minimum torque recorded was reported as Mooney viscosity (ML 1 + 4 at 100 °C).

2.3.3. Cure Characteristics

The cure characteristics of the compounds were obtained using a Rubber Process Analyzer (RPA Elite, TA instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) at 160 °C by applying a deformation of 6.98% at a frequency of 1.667 Hz, for 30 min, following ASTM D5289 [12]. The optimum cure time for each formulation is defined based on the time to reach 90% of the maximum torque () determined from cure curves. The Cure Rate Index (CRI) was calculated using (Equation (1)).

Standard test specimens were vulcanized for subsequent characterization in an electrically heated automatic press (Wickert, Maschinenbau GmbH, Landau, Germany) at 160 °C and 100 bar.

2.3.4. Payne Effect

The Payne effect was analyzed by first curing samples to their in a Rubber Process Analyzer (RPA Elite, TA instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), then cooling the samples to 60 °C before beginning the Payne effect analysis. The test was performed using a strain sweep mode from 0.56 to 100%, and a fixed frequency of 1.6 Hz.

2.3.5. Thermal Treatment

After the vulcanization, the samples were thermally aged in a hot-air oven (LUT 6050, Heraeus, Germany) at 100 °C for 100 h, following ASTM D573 [13].

2.3.6. Tensile Test

The uniaxial tensile test of the compounds was performed using type 2 dumbbell-shaped samples with a thickness of 2.0 ± 0.2 mm and a width in the narrow of tested section of 4.0 ± 0.2 mm. The test was performed using a universal testing machine (Zwick Z01, ZwickRoell GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany). Samples were stretched until failure at a constant crosshead speed of 500 mm/min at room temperature, following ISO 37 [14].

2.3.7. Hardness

The hardness of the compounds was measured using a digital durometer (Zwick 3120, ZwickRoell GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany) in accordance with ASTM D2240 [15] at a temperature of 23 °C. The Shore A scale was used.

2.3.8. Compression Set (CS)

The compression set tests were carried out at room temperature and at 100 °C for 70 h. After releasing the compression force, the sample height was measured and recorded after 30 min and again after 24 h, following ASTM D395 [16].

3. Results and Discussion

To evaluate the feasibility of Aurora PHFree as a sustainable alternative plasticizer to conventional DINP in technical rubber goods, NBR compounds with varying plasticizer content were systematically analyzed. The comprehensive analysis focused on processing behavior, cure characteristics, filler dispersion and mechanical properties of the rubber compounds before and after thermal aging as key performance parameters.

3.1. Mixing Behavior of DINP and Aurora PHFree

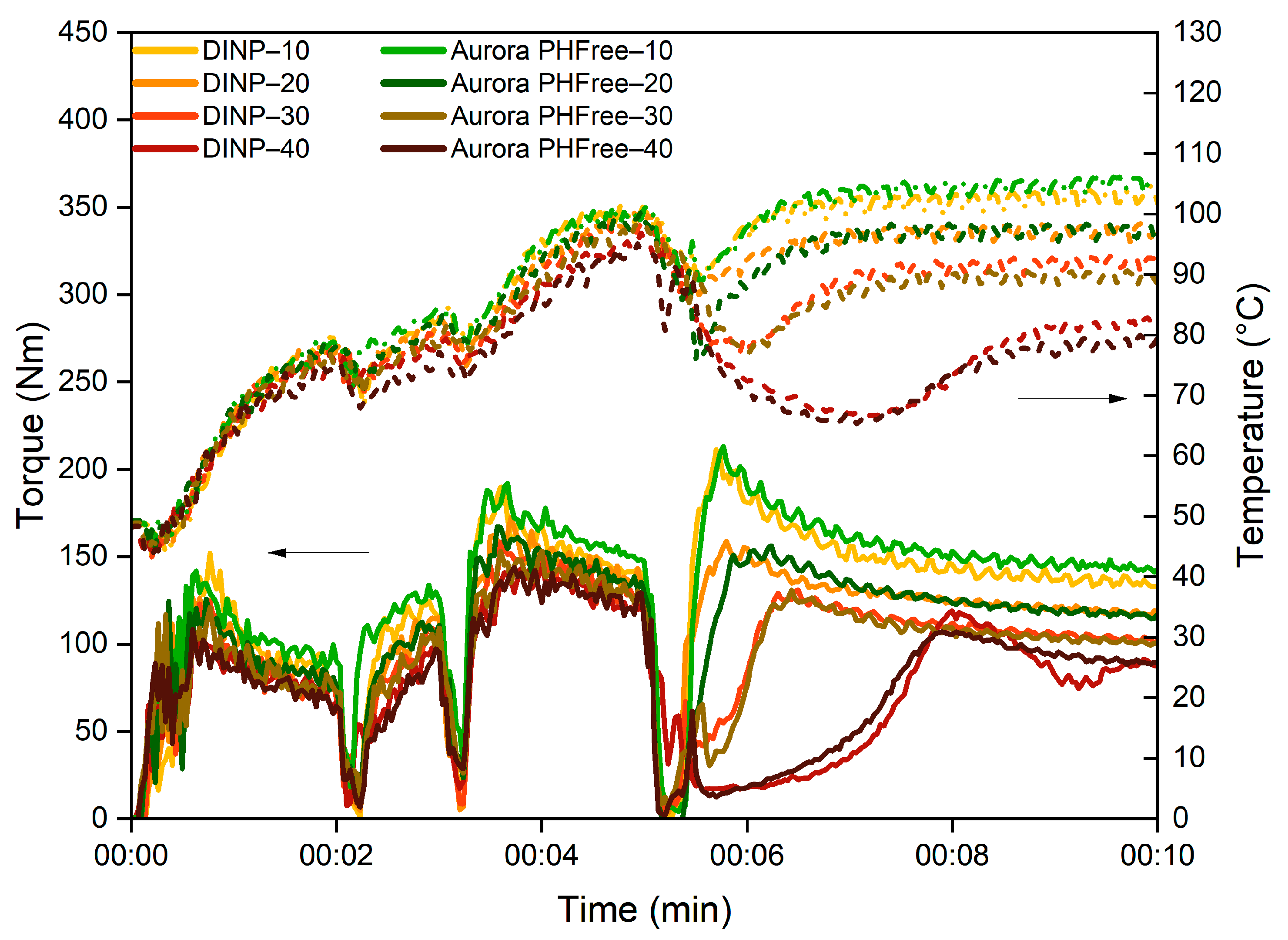

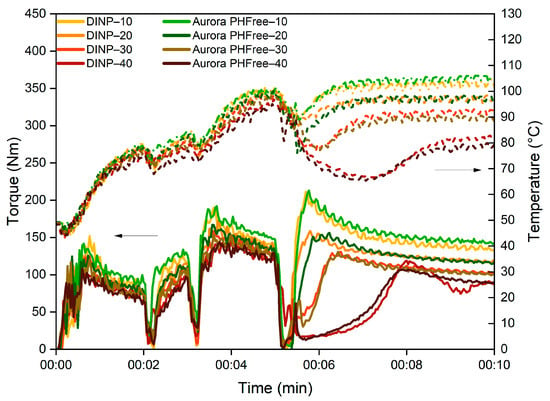

The first step in evaluating the effect of a plasticizer is to analyze its influence during the mixing process. The mixing curves are valuable tools for evaluating the processability of the rubber compounds. Figure 1 shows the evolution of mixing torque and temperature over time of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree. A 1:1 replacement ratio was used to enable a direct comparison between the two plasticizers.

Figure 1.

Mixing torque and temperature profiles of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio.

As the plasticizer content increases, both DINP and Aurora PHFree show a reduction in torque and temperature in the mixing profile. The decrease in torque can be explained by the reduction in internal friction between the polymer chains, while the corresponding decrease in temperature is attributed to the lower mechanical energy dissipated as heat due to the reduction in shear stress [1]. However, the magnitude and rate of torque reduction can vary depending on the characteristics of the plasticizer, such as molecular weight, viscosity, and chemical interactions with the rubber matrix [1].

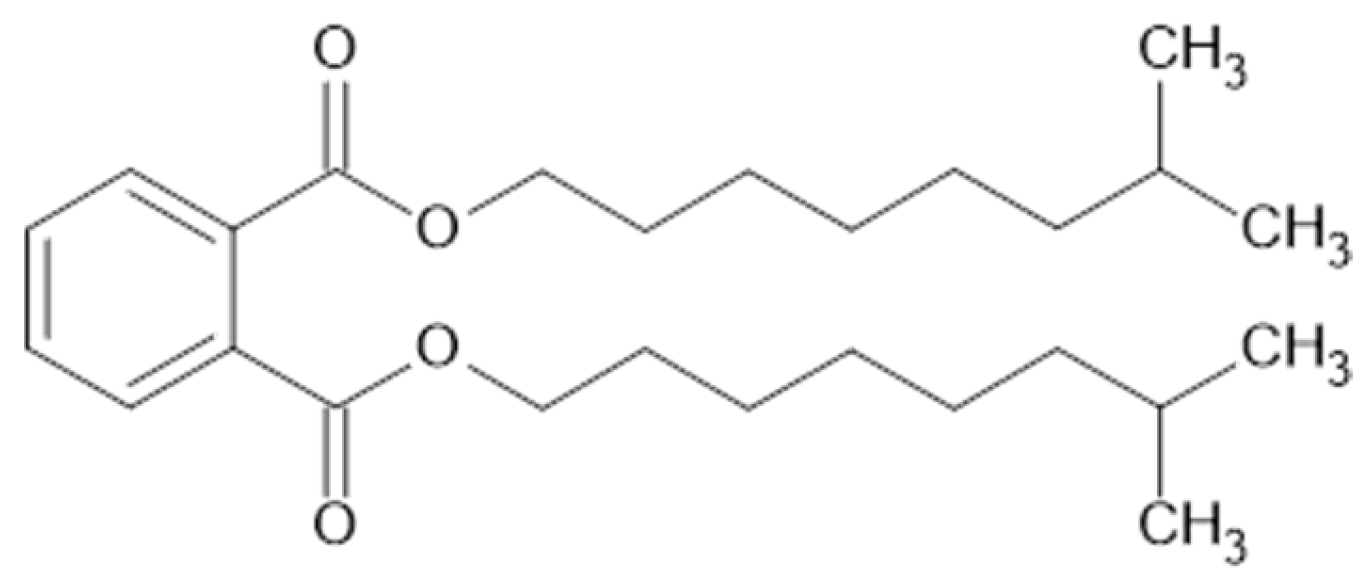

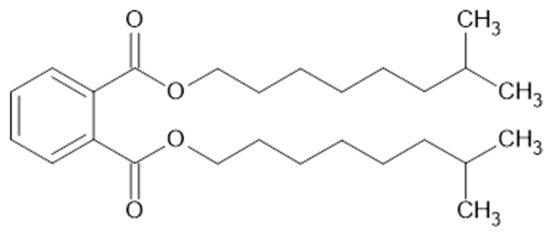

DINP is a branched phthalate ester plasticizer with a relatively high molecular weight (418.62 g/mol) and moderate polarity (see Figure 2). Its chemical structure includes ester functional groups, which improves the compatibility to NBR compared to a non-polar plasticizer. The aromatic rings of DINP can interact mainly through π interactions with the polar nitrile groups (–C≡N) of NBR, improving the mobility of the polymer chains and reducing the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the rubber compounds.

Figure 2.

Chemical structure of Di-Iso-Nonyl Phthalate (DINP).

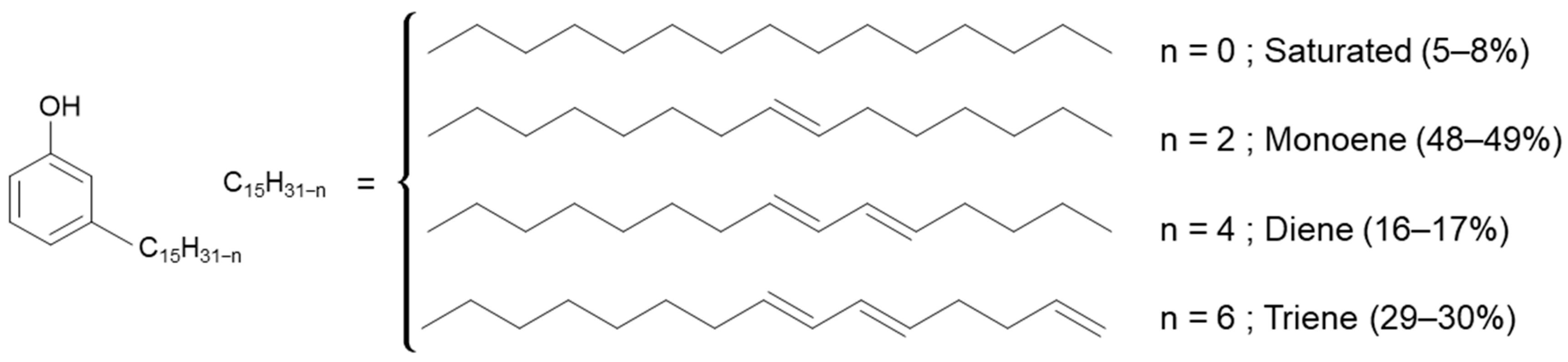

Aurora PHFree is derived from cashew nutshells, indicating that cardanol may be among its main components [17]. Cardanol is a phenolic compound that contains a long aliphatic side chain with varying degrees of unsaturation (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representation of the global chemical structure of cardanol [17].

Considering Aurora PHFree as a cardanol-based plasticizer, its relatively low molecular weight (298.47 g/mol) and the presence of a hydroxyl functional group (–OH), which allows hydrogen bonds interactions with the nitrile units (–C≡N) in NBR, could enhance chain mobility and promote a more efficient reduction in compound viscosity [9,18]. Additionally, the unsaturated aliphatic side chain may act as an internal lubricant during mixing [19].

The compatibility between the plasticizers and the rubber matrix can be evaluated using the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP). The HSP quantify the total solubility (δtotal) of a material in terms of three components: dispersion (δD), related to van der Waals interactions, polarity (δP), associated with dipole–dipole interactions and hydrogen bonding capacity (δH). The closer the d values of two substances are, the better the compatibility [20]. In the case of NBR, its components exhibit distinct solubility parameters; polyacrylonitrile (δtotal = 27.9) is significantly more polar than polybutadiene (δtotal = 16.9). As a result, the NBR copolymer (33% acrylonitrile, 67% butadiene) exhibits an intermediate polarity (δtotal = 21.3). Cardanol (δtotal = 18.7) has a total solubility parameter closer to NBR compared to DINP (δtotal = 17.2) indicating a better compatibility between Aurora PHFree and the rubber matrix.

Examining the individual components of each plasticizer, DINP (δD = 16.3, δP = 4.9, and δH = 2.3, δtotal = 17.2) shows a higher polarity value compared to cardanol which may favor dipole–dipole interactions with the acrylonitrile units of NBR. In contrast, Cardanol (δD = 17.5, δP = 2.3, and δH = 6.2, δtotal = 18.7) exhibits a higher hydrogen bonding parameter compared to DINP indicating stronger potential interactions with the polar acrylonitrile segments of NBR. Additionally, a closer match in dispersion force (δD) values between cardanol and polybutadiene leads to better compatibility in the rubber compound. Consequently, the structural characteristics of Aurora PHFree could provide improved plasticization efficiency compared to conventional DINP.

However, despite the molecular structural differences between DINP and Aurora PHFree, both plasticizers showed similar reduction in torque and temperature profiles at a 1:1 replacement ratio. Therefore, under the specific mixing conditions and compound formulation used in this study, DINP and Aurora PHFree exhibit similar compatibility and performance in the processability of NBR compounds. A possible explanation for the lack of significant improvement in processability compared to DINP could be the complex composition of the bio-based plasticizer, which may not consist entirely of pure cardanol.

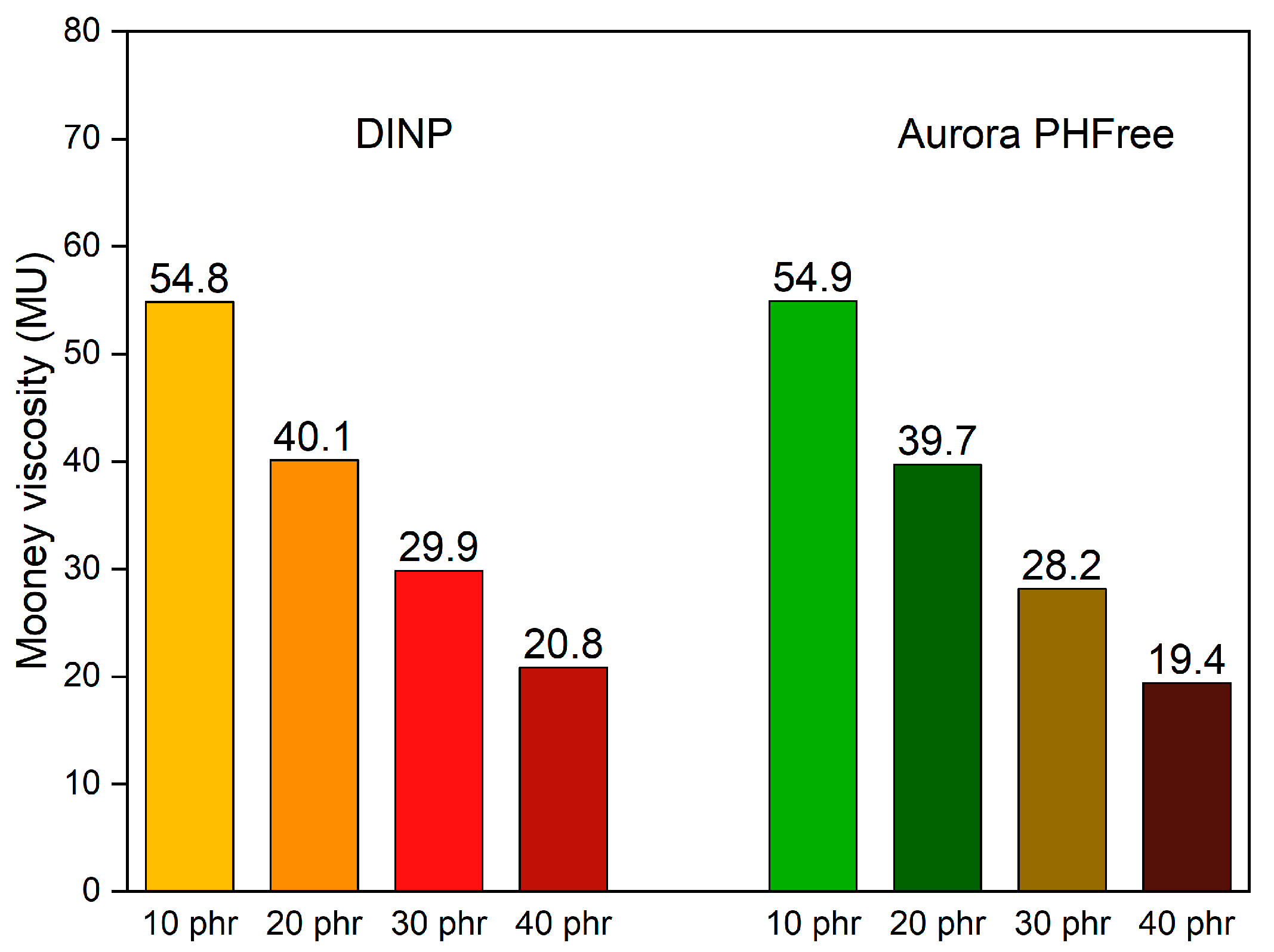

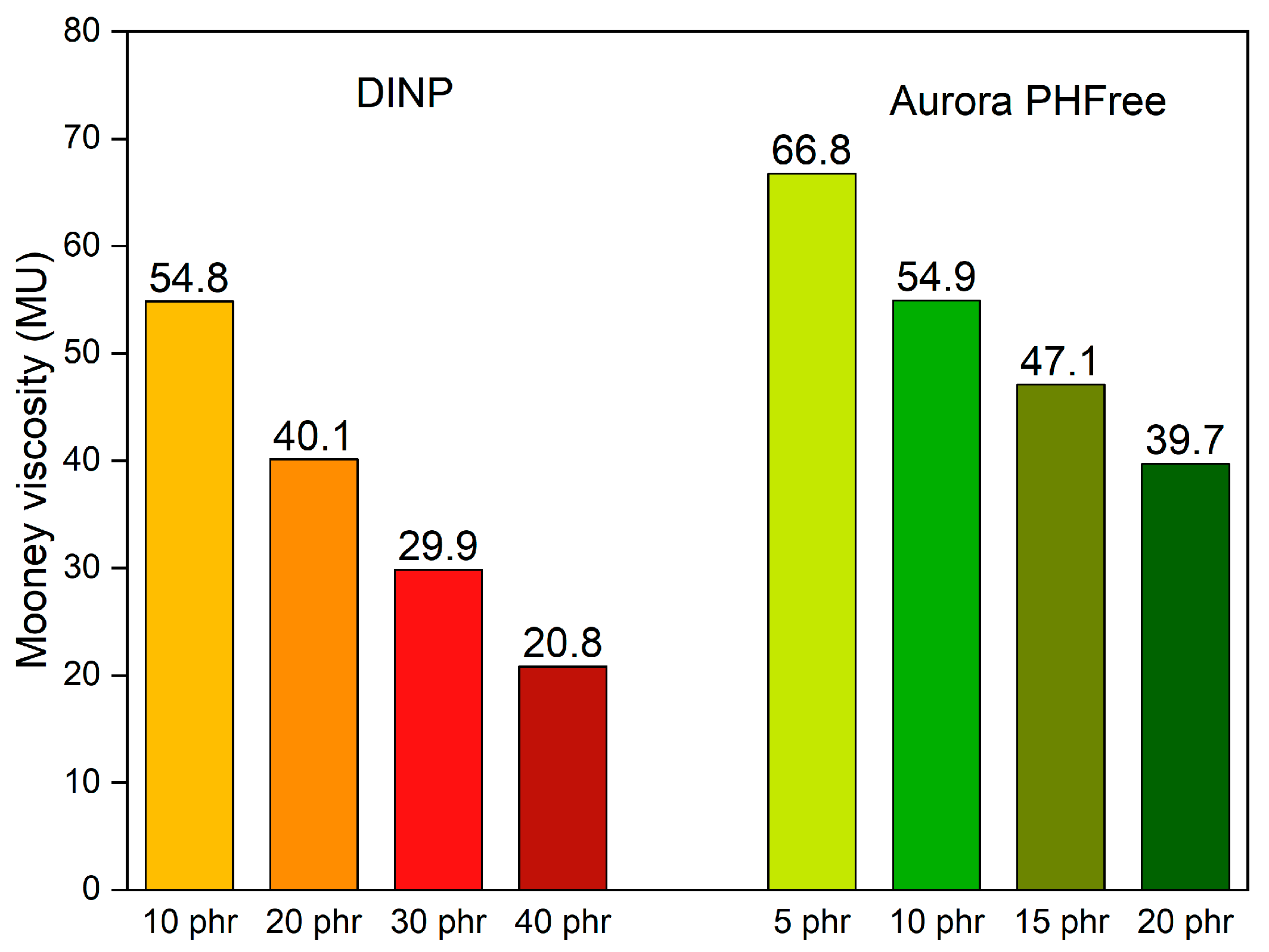

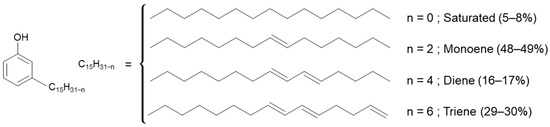

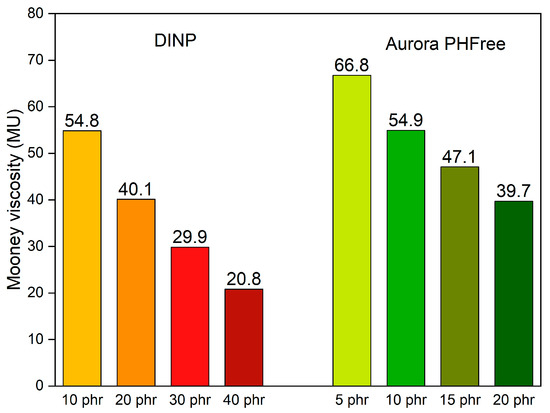

3.2. Mooney Viscosity

The Mooney viscosity is widely used in the rubber industry as a fundamental parameter to characterize the processability of rubber compounds [21]. Figure 4 shows the Mooney viscosity values of NBR compounds with varying content of DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio. As expected, increasing the content of both plasticizers leads to a progressive reduction in the Mooney viscosity. This behavior can be explained due to the reduction in intermolecular forces between the polymer chains and the corresponding increase in chain mobility [1]. This result aligns well with the trends observed in the mixing behavior in Figure 1. At 10 phr, both systems start at nearly the same viscosity values, approximately 55 Mooney units (MU). As the plasticizer content increases up to 40 phr, the viscosity decreases to approximately 20 Mooney units (MU) for both plasticizers. These results indicate that Aurora PHFree provides a similar plasticizing effect in the rubber matrix compared to the conventional DINP.

Figure 4.

Mooney viscosity of the NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio.

3.3. Cure Characteristics

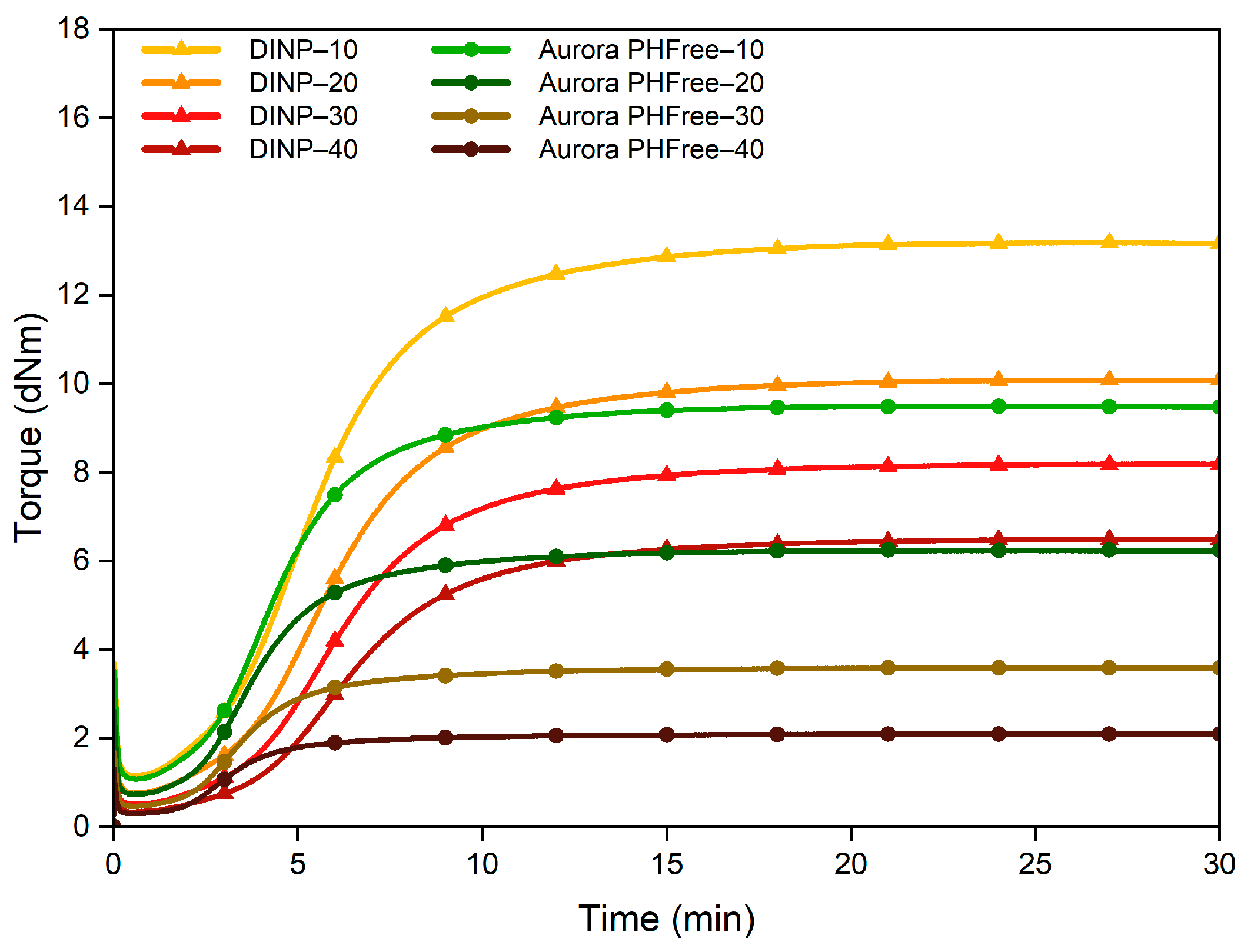

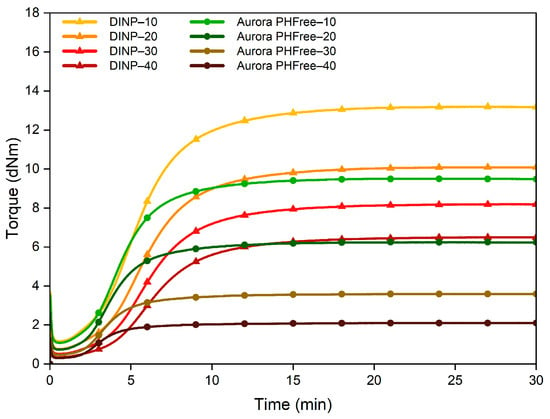

The cure curves provide valuable information on crosslinking kinetics and network formation during vulcanization. Figure 5 shows the evolution of torque over time of the NBR compounds with varying content of DINP and Aurora PHFree as plasticizers.

Figure 5.

Cure curves of the NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio.

As the plasticizer content increases, both DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio shows a reduction in maximum torque (MH). This effect can be attributed to the physical interference of the plasticizer molecules with the formation rubber network by occupying intermolecular spaces between the polymer chains and therefore reducing the number of effective crosslink sites [22]. However, Aurora PHFree shows a more pronounced reduction in MH compared to DINP, while the minimum torque (ML) remains comparable for both plasticizers. Consequently, the torque difference (ΔM = MH − ML) is significantly lower for Aurora PHFree (see Table 4) Although it is reported in the literature that ΔM is influence by filler–filler and polymer–filler interactions and the initial minimum torque of the rubber compound [23], it can be assumed that these contributions are similar in both formulations. This assumption is supported by the similar ML values observed, indicating similar initial viscosity and filler dispersion. Therefore, ΔM may be used as an indicator for the crosslink density of the rubber compounds [19].

Table 4.

Cure characteristics of NBR compounds with DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio.

The NBR compounds containing Aurora PHFree show faster vulcanization reflected in slightly reduced scorch times (ts2), shorter optimum curing times (t90) and higher Cure Rate Index (CRI) values compared to DINP. This acceleration could be attributed to the role of cardanol as an auxiliary activator during vulcanization [24]. The phenolic group in its structure can interact with zinc oxide to form zinc cardanol salts, in addition to the conventional zinc stearate from the stearic acid during vulcanization. These salts could act as activators for the accelerators TBzTD and MBTS in the system, allowing early activation and promoting the faster generation of active sulfurating species [19]. The reduction in MH could be attributed to the possible formation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups in the structure of Aurora PHFree and the amine functionality of the accelerator (TBzTD), altering its activity during vulcanization. Another possible explanation could be the consumption of sulfur by the unsaturation in the long aliphatic side chain of Aurora PHFree, reducing the amount of sulfur available for crosslinking the NBR polymer chains [7,17].

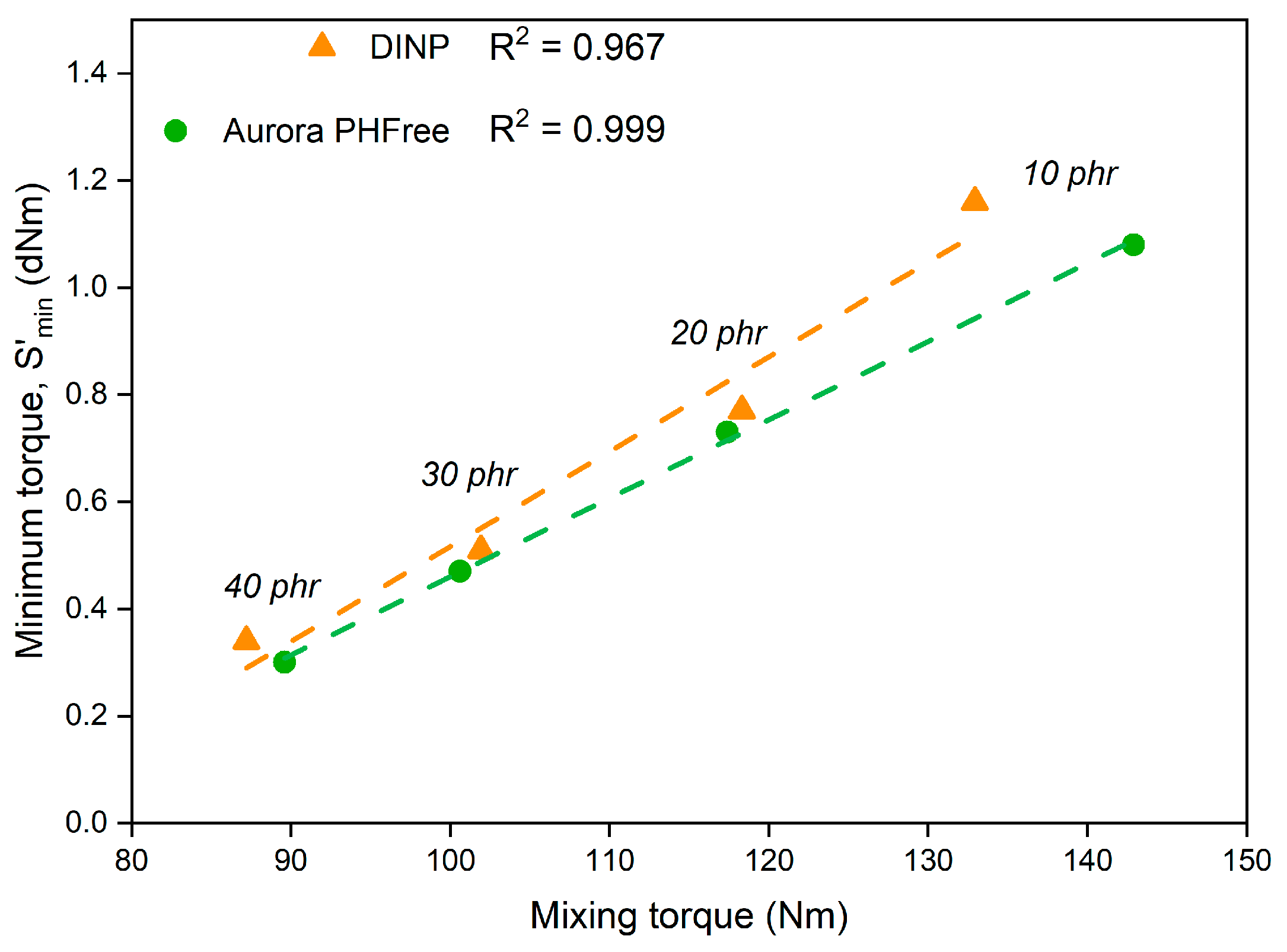

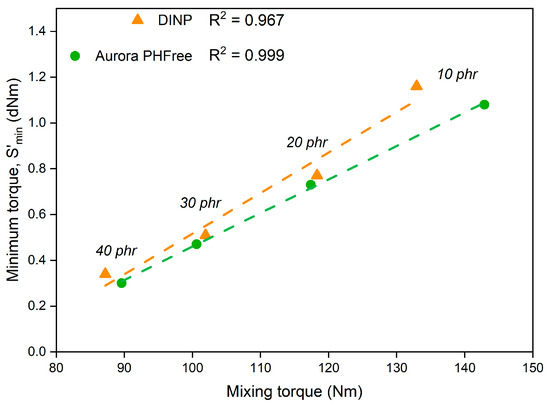

The similar minimum torque (ML) values observed for compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree align well with the trends observed in the mixing behavior in Figure 1. Since both parameters reflect the overall viscosity of the rubber compounds under specific processing conditions, the mixing torque during compounding and the minimum torque during the early stages of vulcanization. Based on these results, it was possible to establish a linear correlation between these parameters with coefficients of determination (R2) of 0.967 for DINP and 0.999 for Aurora PHFree, as shown in Figure 6. This result could provide a practical basis for optimizing rubber compound formulations and for improving control over processing conditions.

Figure 6.

Correlation between mixing torque and minimum cure torque for DINP and Aurora PHFree.

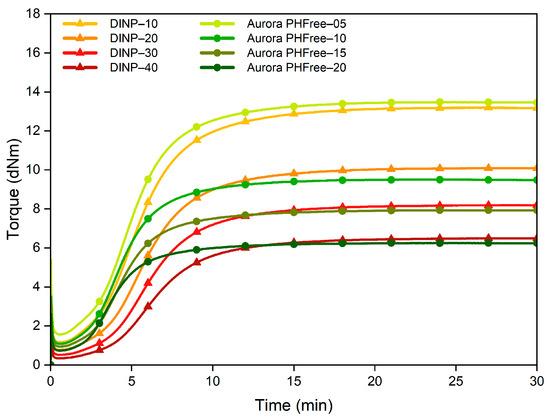

3.4. Selection of Equivalent Plasticizer Content for Comparative Analysis

It was observed that the compound containing 10 phr of Aurora PHFree exhibits a similar torque difference to that of 20 phr of DINP, and correspondingly, the compound with 20 phr of Aurora PHFree reaches the performance of the compound with 40 phr of DINP. Based on these results, new compounds were prepared by keeping the base formulation constant and using half the amount of Aurora PHFree relative to DINP for direct comparison. The new compounds include 5 and 15 phr of Aurora PHFree. Table 5 summarizes the pairs of compounds evaluated including their respective plasticizer content.

Table 5.

NBR compounds containing DINP and half of the amount of Aurora PHFree (2:1 replacement ratio).

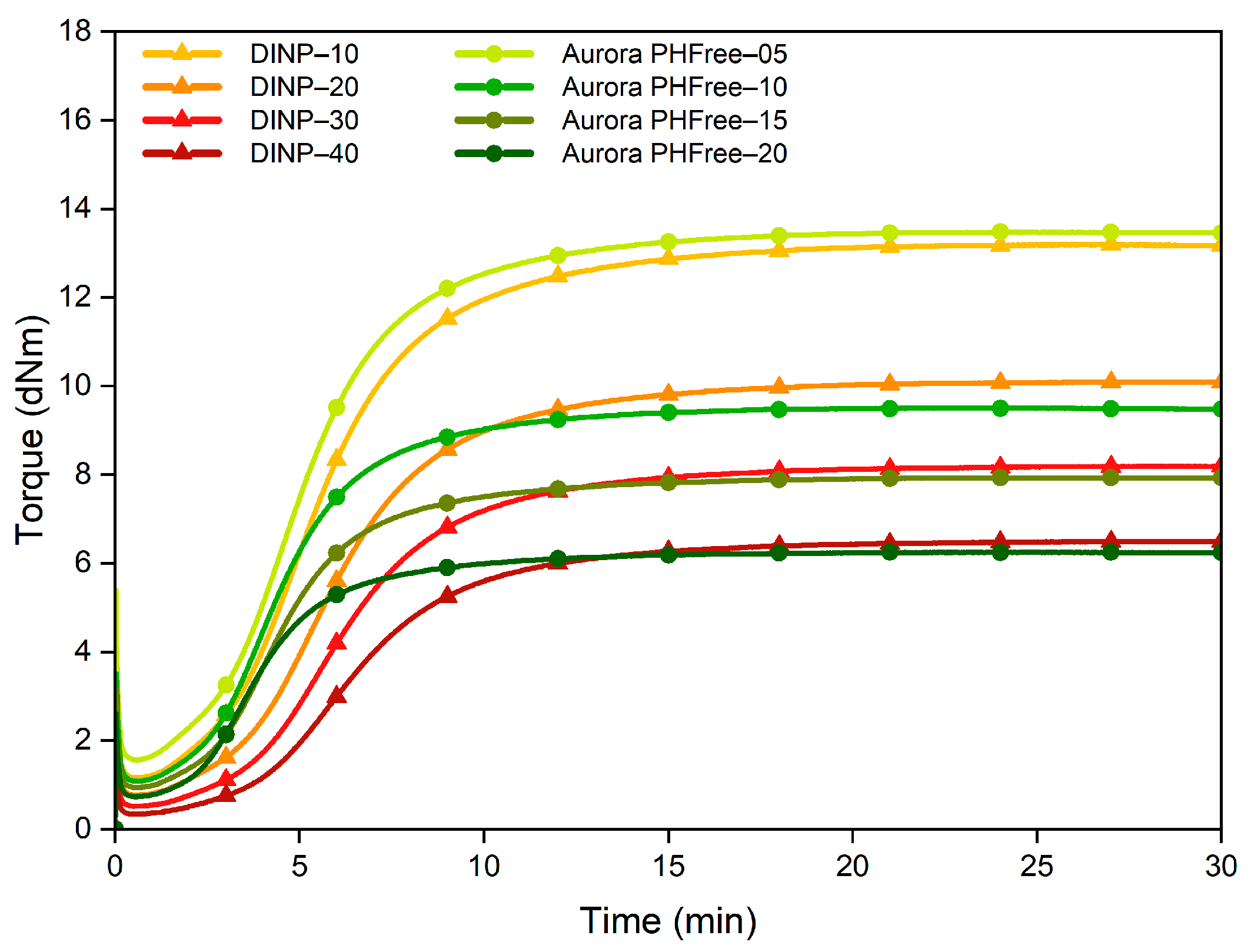

Figure 7 shows the cure behavior of the NBR compounds containing DINP and half the amount of Aurora PHFree compared to DINP. Reducing the content of the bio-based plasticizer by half results in cure properties similar to those with the full content of DINP. Compounds containing Aurora PHFree exhibit slightly higher maximum torque (MH) and minimum torque (ML) values while the torque difference (ΔM) remained similar.

Figure 7.

Cure curves of the NBR compounds with DINP and half the amount of Aurora PHFree.

This similar cure behavior indicates that Aurora PHFree achieves equivalent cure performance efficiency to DINP at a significantly lower content level. Additionally, the compounds containing the bio-based plasticizer show a higher Cure Rate Index (CRI), indicating an accelerated vulcanization process even at lower loading levels. The cure characteristics are summarized in Table 6. A possible explanation for the efficiency of Aurora PHFree could be due to its possible distinct chemical structure which promotes specific interaction with the polymeric matrix and vulcanization system as discussed before.

Table 6.

Cure characteristics of NBR compounds containing DINP and half the amount of Aurora PHFree.

Figure 8 shows the Mooney viscosity of NBR compounds containing half the amount of Aurora PHFree compared to DINP. At a 2:1 replacement ratio, the compounds containing half of the amount of Aurora PHFree show higher Mooney viscosity values compared to DINP, which can be attributed to the lower plasticizer content in the rubber compounds. At the lowest plasticizer content, 5 phr, Aurora PHFree shows the highest Mooney viscosity value, approximately 67 Mooney units (MU). However, these values obtained remain within a practical processing window, indicating that even at reduced content Aurora PHFree, the rubber compounds maintain suitable processability behavior [21].

Figure 8.

Mooney viscosity of the NBR compounds containing DINP and half the amount of Aurora PHFree.

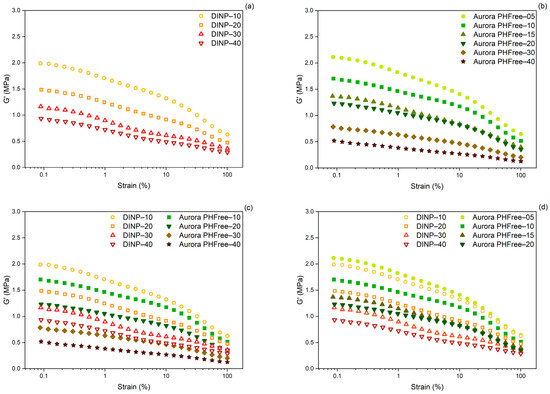

3.5. Filler Network Structure: Payne Effect Comparison

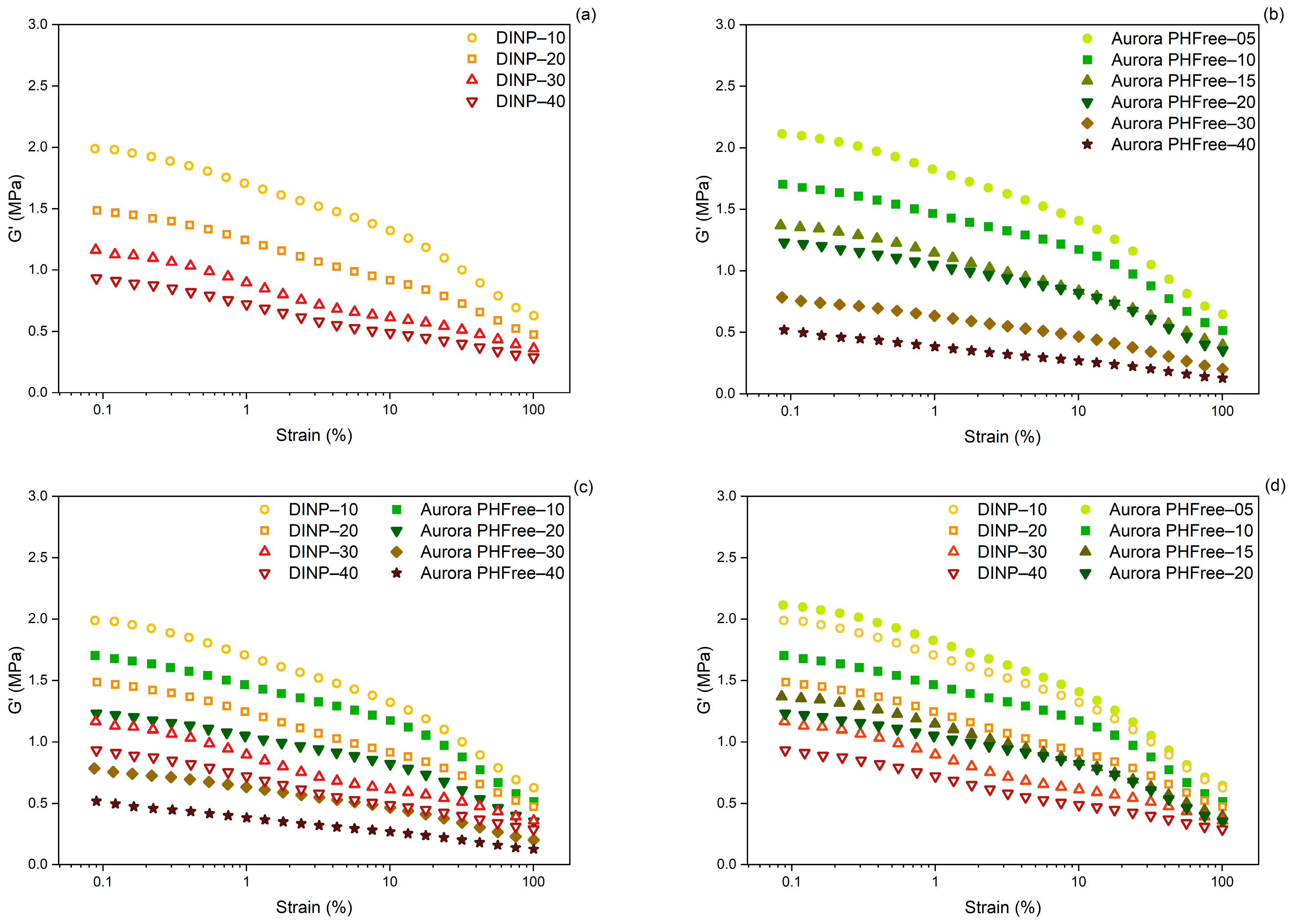

When evaluating the efficiency of a plasticizer, it is important to consider not only its compatibility with the polymer matrix, but also its influence on filler dispersion. A Payne effect analysis of cured compounds was performed to evaluate the influence of plasticizers on filler dispersion and filler–filler network interactions. The Payne effect, defined as the difference in storage modulus (ΔG’) between low (0.56%) and high (100%) strain amplitudes, quantifies the extent of filler–filler interactions and provides an indication of the micro-dispersion of fillers in the rubber matrix. A lower Payne effect indicates a more efficient filler dispersion, while a high Payne effect indicates the presence of a strong filler network, typically due to poor dispersion and/or strong filler–filler interactions [25,26].

Figure 9a,b show the variation in storage modulus as a function of strain amplitude for NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, respectively. As the plasticizer content increases, both DINP and Aurora PHFree lead to a reduction in the Payne effect, indicating weaker filler-filler interactions. This reduction could be attributed to the fact that both plasticizers contain aromatic rings capable of π-π stacking interactions with the graphene-like layers of carbon black (CB) particles. As a result, the dispersion of the fillers is improved within the rubber matrix [27].

Figure 9.

Payne effect of cured NBR compounds containing (a) DINP, (b) Aurora PHFree, (c) DINP and Aurora PHFree at a 1:1 replacement ratio and (d) DINP and half the amount of Aurora PHFree.

Figure 9c,d show the Payne effect of NBR compounds plasticized with DINP and Aurora PHFree at 1:1 and 2:1 replacement ratio, respectively. At a 1:1 replacement ratio, the compounds containing Aurora PHFree show lower Payne effect values compared to DINP, indicating reduced filler–filler interactions. This can be attributed to the molecular structure of the cardanol-based plasticizers. In contrast to DINP, Aurora PHFree presents a hydroxyl group which can promote hydrogen bonding with the nitrile units in NBR matrix. The combination of these interactions (hydrogen bonding and π-π stacking interactions) could promote a better distribution and wetting of filler particles, reducing filler–filler interactions. At a 2:1 replacement ratio, the compounds containing half of the amount of Aurora PHFree compared to DINP show slightly higher filler–filler interactions, which can be attributed to the lower plasticizer content. This result indicates that Aurora PHFree provides a better compatibilization between the rubber matrix and the semi-reinforcing carbon black filler (N660) even at half of the amount compared to the traditional DINP.

3.6. Mechanical Performance

The mechanical performance of a rubber compound plays a key role in evaluating the feasibility of a material as plasticizer. Properties such as tensile strength, elongation at break, modulus, hardness and compression set provide a comprehensive understanding of the rubber compound performance. These properties are influenced by the level of plasticization, crosslink density and filler dispersion, which are affected by the type and amount of plasticizer used [2]. Additionally, the evaluation of properties both before and after thermal treatment (thermal oxidative aging) provides critical understanding into the resistance of the rubber compounds to thermal stress and its suitability for long-term applications.

Pairs of compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree with equivalent cure performance, rather than equivalent phr content, were selected to provide a fair and meaningful comparison between the two plasticizers. Further analyses were performed only comparing the DINP containing compounds with those containing half of the amount of Aurora PHFree. This approach offers insights into the efficiency and potential substitution alternative of Aurora PHFree as a bio-based plasticizer alternative to conventional DINP.

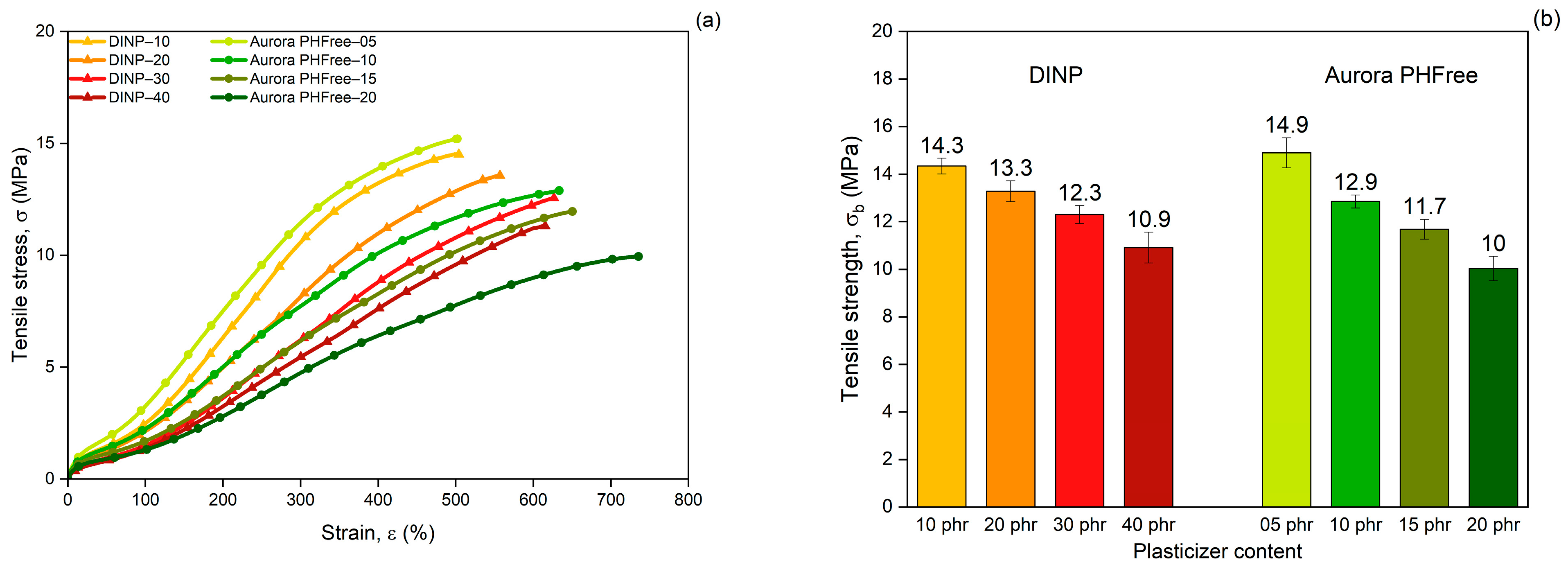

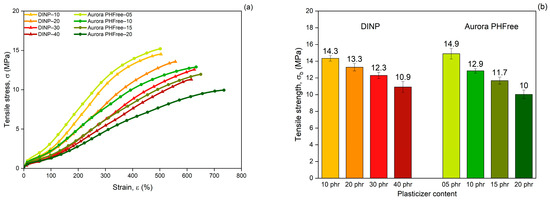

3.7. Tensile Stress–Strain Properties

Figure 10a shows the tensile stress–strain curves of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree as plasticizers at equivalent cure performance. At lower plasticizer content, both systems show similar mechanical responses. However, for compounds with higher plasticizer content (40 phr of DINP and 20 phr of Aurora PHFree), the stress–strain curve diverges. The compound with higher content of Aurora PHFree shows lower stress at higher strains. This behavior could be attributed to the formation of plasticizer-rich domains within the rubber matrix when excessive content of Aurora PHFree is used [22]. These domains could act as weak and soft spots in the vulcanizates, reducing the intermolecular interactions and mechanical strength. As a result, the material becomes more flexible and elongate more.

Figure 10.

(a) Tensile stress–strain curves, (b) Tensile strength, (c) Elongation at break and (d) Reinforcement index of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance.

As expected, increasing the content of both plasticizers, the tensile stress decreases (Figure 10b), while the elongation at break increases (Figure 10c), consistent with the softening effect of plasticizers. The compounds containing half the amount of Aurora PHFree compared to DINP exhibit tensile strength and elongation at break values at a similar level within the measurement error (see Table 7). At the lowest plasticizer content, the tensile strength and elongation at break differ by approximately 4% and 3%, respectively. At the highest concentration, the differences increase up to around 8% for tensile strength and up to 16% for elongation at break between DINP and Aurora PHFree. These variations remain within the reproducibility limits reported in ISO 37 [14], where tensile strength typically varies up to ~10% and elongation at break up to ~18% for NBR compounds, indicating similar mechanical performance between DINP and Aurora PHFree.

Table 7.

Tensile strength, elongation at break, and percentage differences in NBR compounds with DINP and Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance.

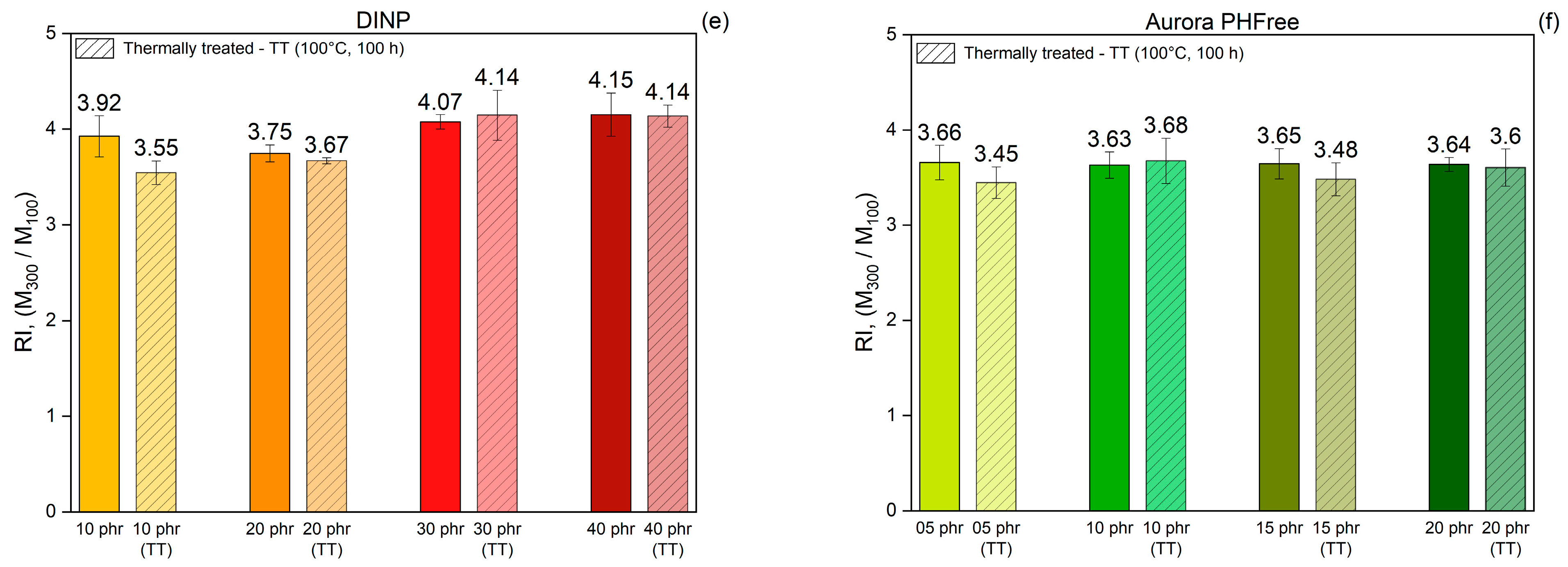

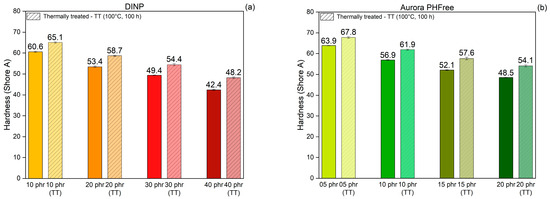

Figure 10d shows the reinforcement index (RI), calculated as the ratio of the moduli at 300% strain to 100% strain (M300/M100). The RI is a widely used parameter for evaluating the reinforcing efficiency of fillers in elastomeric matrices, as it reflects the extent to which a filler increases the stiffness of a rubber compound [28]. Compounds containing half of the amount of Aurora PHFree show slightly lower reinforcement indices compared to the pairing compound with DINP. Although Aurora PHFree improves the filler dispersion, which enhances the reinforcement efficiency of the rubber compound, its pronounced plasticizing effect increases the polymer chain mobility. This enhanced mobility reduces the stress at higher elongation. Therefore, a lower moduli at 300% elongation (M300) relative to that at 100% (M100) leads to a decrease in RI.

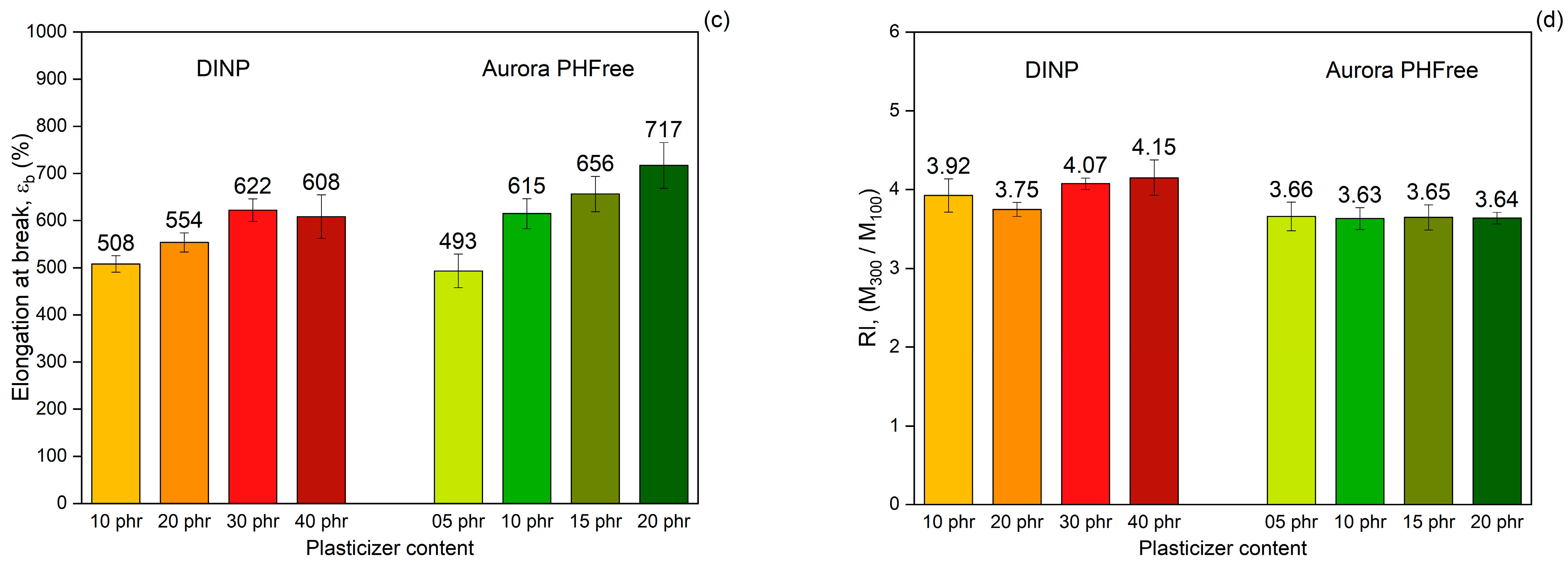

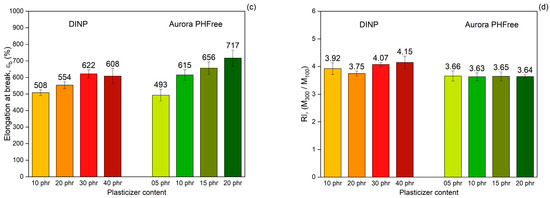

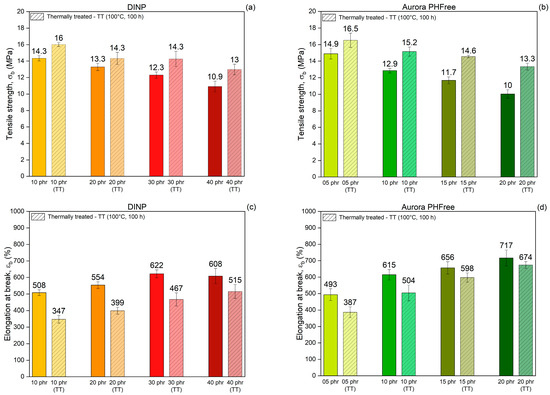

To evaluate the changes in mechanical and physical properties before actual long-term use, an accelerated thermal aging method was used to simulate long-term service conditions on vulcanized rubber. This method involves exposing the rubber compounds to elevated temperatures for extended periods, which simulates oxidative degradation and other aging phenomena that occur naturally over time [29]. Figure 11a,b show the tensile strength while Figure 11c,d show the elongation at break of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, respectively, measured before and after thermal aging at 100 °C for 100 h. After thermal treatment, all samples exhibit higher tensile strength and lower elongation at break, indicating that the rubber compounds become stiffer and less flexible. This effect results from the formation of additional crosslinks during thermal treatment, driven by the thermo-oxidative degradation mechanism of NBR. Specifically, the butadiene segments in the NBR matrix are susceptible to oxidative crosslinking, where radicals generated by heat promote the creation of new covalent bonds between polymer chains [29,30].

Figure 11.

Comparison of tensile strength (a,b), elongation at break (c,d) and Reinforcing index (e,f) of NBR vulcanizates containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance, before and after thermal treatment at 100 °C for 100 h (TT: Thermally Treated).

Table 8 summarizes the tensile strength and elongation at break before and after thermal aging of the rubber compounds and their respective percentage difference. The results show distinct trends in property retention depending on the type and content of plasticizer. Increasing the content of both plasticizers improves the retention of elongation at break, while tensile strength retention is higher at lower plasticizer content. Moreover, compounds containing DINP exhibit better retention of tensile strength with a maximum increase of 19% at 40 phr, compared to 33% for 20 phr of Aurora PHFree. In contrast, Aurora PHFree shows better retention of elongation at break after aging with a decrease of 6% at 20 phr, compared to 15% for 40 phr of DINP.

Table 8.

Tensile strength, elongation at break, and percentage differences in NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance, before and after thermal treatment.

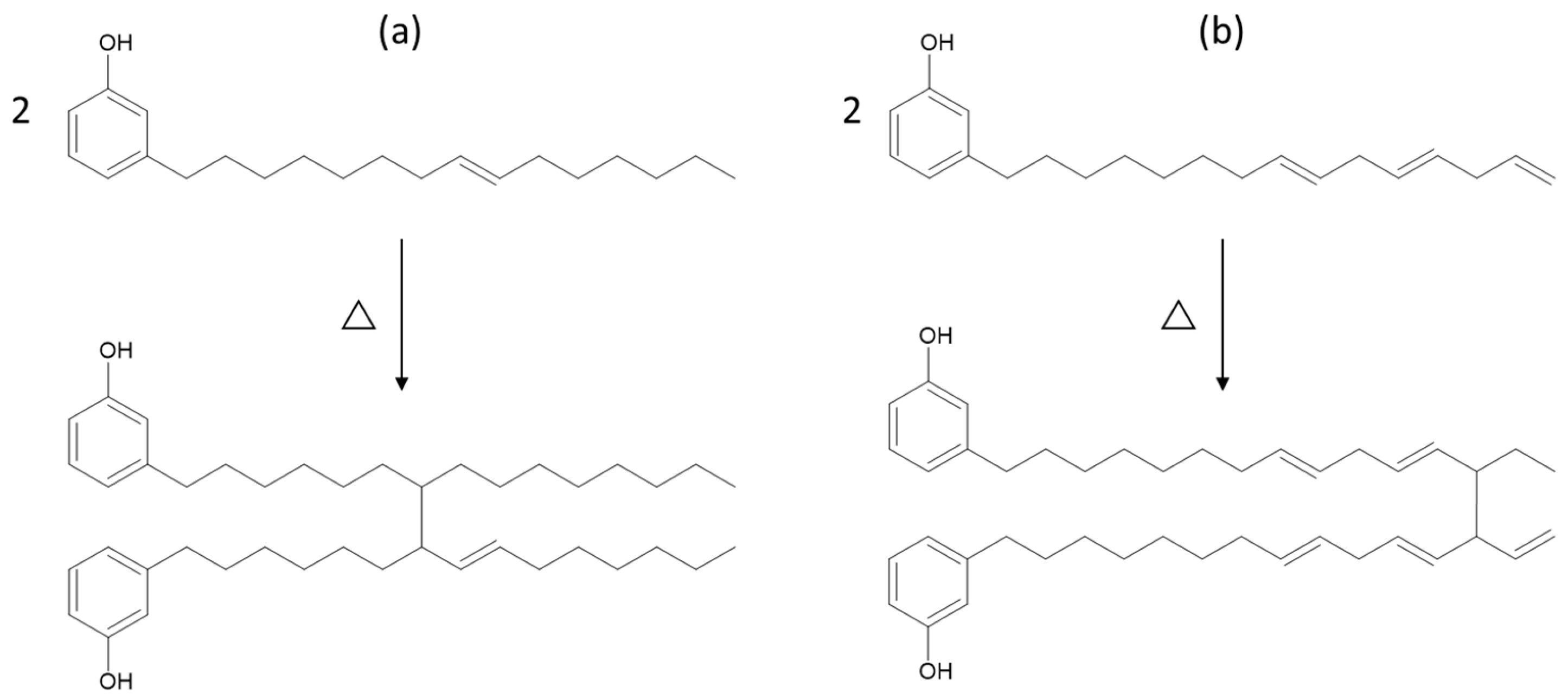

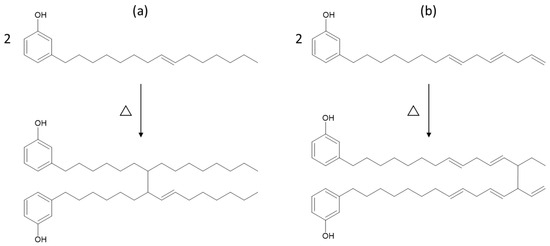

A possible explanation for the improved retention in elongation at break of the rubber compounds containing Aurora PHF could be due to its chemical structure. The phenolic functionality in the cardanol-based plasticizer can act as a radical scavenger. This antioxidative behavior offers protection against thermo-oxidative degradation by neutralizing free radicals. Therefore, Aurora PHFree maintains chain mobility and reduces embrittlement under thermal aging [17]. At higher concentrations, the increased availability of phenolic sites can enhance this protective effect. In principle, the radical-scavenging behavior of cardanol should also limit additional crosslink formation during thermo-oxidative aging of NBR, potentially supporting better tensile strength retention. However, the observed lower retention in tensile strength of Aurora PHFree compared to DINP indicates that other mechanisms influence the aging response. A possible explanation for this behavior could be the oligomerization reaction of the unsaturated side chains of cardanol, which may act as secondary crosslinks. The unsaturated side chains are susceptible to thermos-oxidative reactions at elevated temperatures [17]. Figure 12 shows two schematic representations of possible oligomerization pathways: (a) through internal double bond loss and (b) through vinyl loss in the triene segment. The exact position of the remaining double bonds and connecting bond between the molecules is unclear. However, according to the literature, these are the proposed structures. The complex composition of the bio-based plasticizer, which may not consist entirely of pure cardanol could be a possible reason for the differences in aging behavior. Therefore, the full mechanism underlying the effect of Aurora PHFree on property retention during thermal aging remains not fully understood and requires further investigation.

Figure 12.

Possible oligomerization reactions of cardanol under high temperatures: (a) through internal double bond loss and (b) through vinyl loss in triene segment.

Figure 11e,f present the reinforcement index (RI) values of the vulcanizates before and after thermal aging. The results indicated that the RI remains unchanged after thermal aging for both plasticizers. This stability could be attributed to the proportional increase in both M100 and M300 due to additional crosslinking induced by thermo-oxidative degradation during thermal exposure. The uniform stiffening of the rubber compound could cause both moduli to increase, similarly preserving their ratio. The unchanged RI reflects that the structural integrity and mechanical response of the rubber compounds are maintained under prolonged thermal stress.

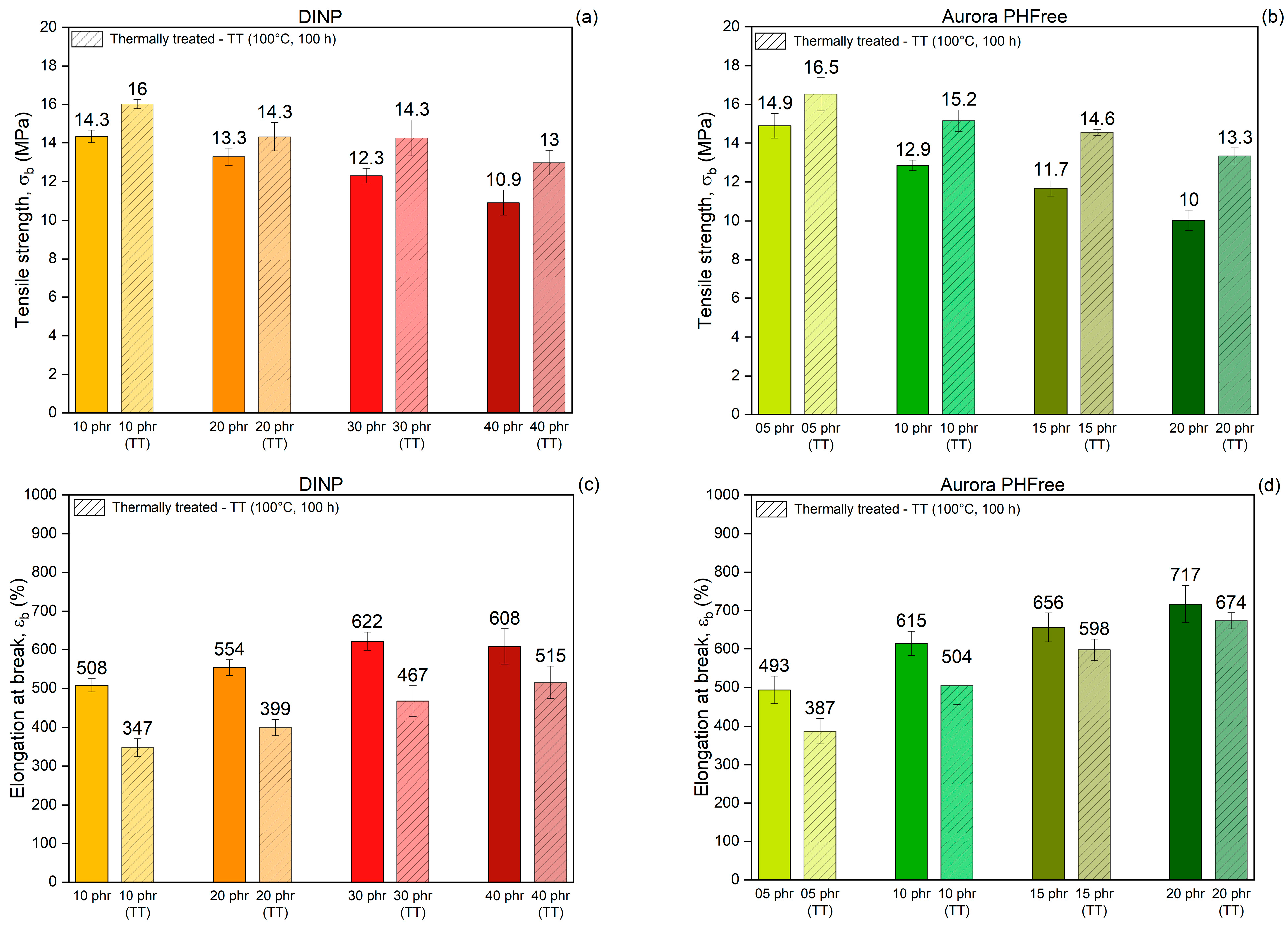

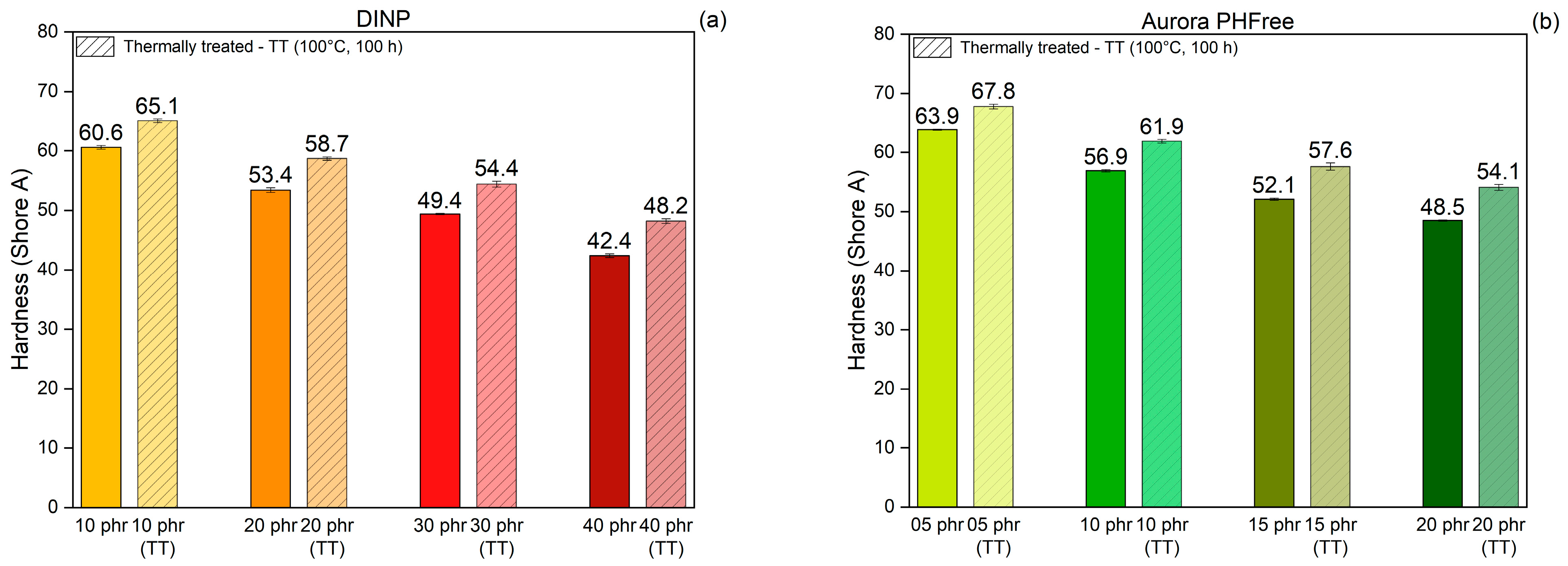

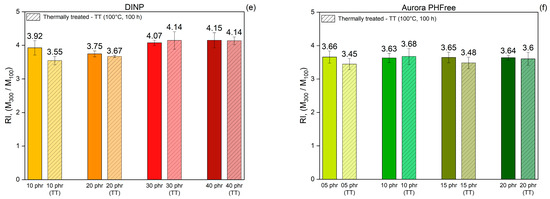

3.8. Hardness

The hardness of rubber compounds reflects the resistance to indentation and correlates with the stiffness of the material. It is significantly influenced by the crosslink density, filler content, and presence of plasticizers in the rubber compound [21]. Figure 13a,b present the hardness values of the NBR compounds containing DINP and half of the amount of Aurora PHFree, measured at room temperature and after thermal treatment at 100 °C for 100 h, respectively. As expected, increasing the content of both plasticizers leads to a reduction in the hardness of the NBR compounds due to the enhanced polymer chain mobility and reduced stiffness. When comparing pairs of rubber compounds with equivalent cure performance, Aurora PHFree presents slightly higher hardness values compared to DINP. Since the crosslink density of the compounds is similar, this difference in hardness values could be attributed to the slightly higher filler–filler interactions observed in the compound containing Aurora PHFree, as indicated by the Payne effect measurements of the compounds containing Aurora PHFree. This could be a result from the lower plasticizer content, which allows more interactions between filler particles.

Figure 13.

Shore A Hardness of NBR compounds containing (a) DINP and (b) Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance, before and after thermal treatment at 100 °C for 100 h (TT: Thermally Treated).

After thermal aging at 100 °C for 100 h, all samples exhibit a slight increase in hardness values, with maximum changes of up to 13%, indicating that the rubber compounds become stiffer and less flexible. This increase in hardness is a consequence of the thermo-oxidative crosslinking of NBR, which leads to an increase in crosslink density due to the formation of new covalent bonds between polymer chains, as discussed before.

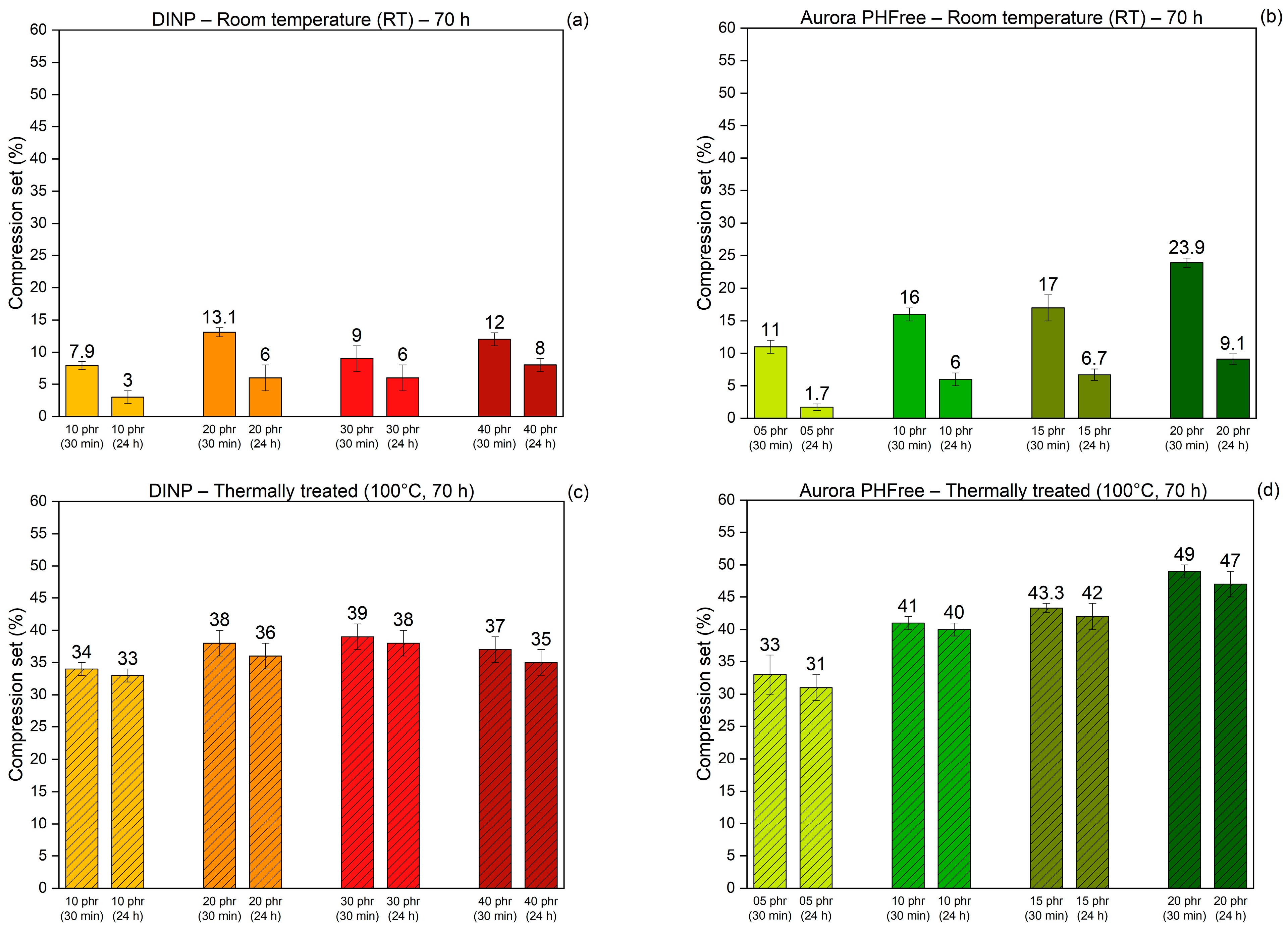

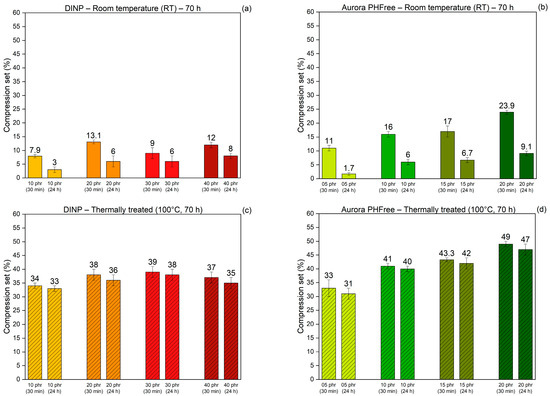

3.9. Compression Set

The compression set reflects the ability of rubber compounds to recover their original shape after being subjected to a compressive force for a determined time and temperature condition. These measurements provide insight into the elastic recovery and permanent deformation characteristics of the rubber compounds [21]. A lower compression set value indicates better elastic recovery and long-term performance. Figure 14a,b present the compression set behavior of the NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, respectively, measured after 30 min and 24 h of recovery after having been compressed for 70 h at room temperature. Figure 14c,d show corresponding compression set behavior after compression at 100 °C for 70 h, followed by the same recovery conditions.

Figure 14.

Compression set of NBR compounds containing DINP and Aurora PHFree, at equivalent cure performance, measured after 30 min and 24 h of recovery following 70 h of compression at (a,b) room temperature and (c,d) 100 °C.

For all rubber compounds, the compression set values measured after 24 h are lower than those recorded after 30 min, indicating a progressive recovery of the elastic network over the full measurement time. Compounds containing Aurora PHFree show slightly higher values of compression set compared to DINP. This could be attributed to the improved lubricating and softening effect of the bio-based plasticizer. Additionally, the compression set values obtained at elevated temperature are higher than those at room temperature, reflecting a higher degree of permanent deformation and reduced elastic recovery. These results align with the structural changes in the rubber matrix due to the creation of new covalent bonds between polymer chains leading to the formation of additional crosslinks. Moreover, the NBR compounds containing Aurora PHFree exhibit slightly higher compression set values compared to those of DINP. This behavior could be attributed to the molecular structure of cardanol-based plasticizers. The presence of unsaturated side chains, which are susceptible to thermo-oxidative reactions, could lead to secondary crosslinking or degradation processes that compromise the recovery of the material [17].

4. Conclusions

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of Aurora PHFree, a bio-based phthalate-free plasticizer, as a sustainable alternative to the conventional petroleum-based Di-Iso-Nonyl Phthalate (DINP) in Nitrile Butadiene Rubber (NBR) compounds for technical rubber good applications.

In terms of processability, Aurora PHFree achieves a similar plasticizing effect to conventional DINP at a 1:1 replacement ratio, evidenced by an equivalent reduction in torque and temperature profiles during mixing as well as by similar Mooney viscosity values. At equivalent plasticizer content, Aurora PHFree exhibits a faster vulcanization and higher cure rate index (CRI). Additionally, the minimum torque (ML) remains unchanged while the torque difference (ΔM) decreases, indicating a lower crosslink density. Comparative analysis reveals that Aurora PHFree achieves equivalent cure performance to DINP using only half the amount, indicating its higher plasticizing efficiency and compatibility. These effects could be attributed to the molecular structure of the cardanol-based plasticizer due to the presence of the phenolic group and the unsaturated long aliphatic side chain and the possible physical interactions with the rubber matrix and the curing package.

At a 1:1 replacement ratio, Aurora PHFree improves filler micro-dispersion, demonstrated by reduced filler–filler interactions in Payne effect experiments.

Mechanically, rubber compounds with equivalent cure performance show that Aurora PHFree maintained similar tensile strength and elongation at break compared to DINP, with slightly higher hardness and compression set values, attributed to the lower plasticizer content and improved plasticizing effect of the bio-based plasticizer. After thermal treatment, Aurora PHFree maintains similar performance to DINP, showing higher tensile strength, hardness and compression set values but lower elongation at break, likely due to the formation of additional crosslinks by the thermo-oxidative degradation of NBR.

Overall, Aurora PHFree has been demonstrated to be a sustainable and technically feasible alternative to traditional petroleum-derived DINP in NBR-based compounds. At half the content, Aurora PHFree causes a slight increase in the Mooney viscosity of the rubber compounds, but the values remain within a favorable processing window. However, at a reduced content, Aurora PHFree provides similar performance on mixing behavior, cure characteristics and mechanical properties, replacing DINP without compromising key functional properties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.-M., C.B., N.W. and A.B.; methodology, J.A.-M., W.K. and C.B.; formal analysis, J.A.-M. and W.K.; investigation, J.A.-M.; resources, C.B., N.W. and A.B.; data curation, J.A.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.-M. and W.K.; writing—review and editing, J.A.-M., W.K., C.B. and A.B.; visualization, J.A.-M.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, J.A.-M. and A.B.; funding acquisition, J.A.-M. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that this study received funding from Ergon, Inc. and Process Oils, Inc. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ergon, Inc. and Process Oils, Inc. for supplying the Aurora PHFree samples used in this study and funding this research.

Conflicts of Interest

Cristina Bergmann, works for a company Ergon International Inc., Drève Richelle, Waterloo, Belgium; Another author, Nick White, works for a company Process Oils Inc., One Sugar Creek Center Blvd, Sugar Land, Texas, USA. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Rodgers, B. Rubber Compounding: Chemistry and Applications; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 333–378. [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann, W. Rubber Technology Handbook; Hanser Publishers: Munich, Germany, 1989; pp. 294–321. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, R. Rubber Basics; Smithers Rapra Technology Ltd.: Shawbury, UK, 2002; pp. 144–155. [Google Scholar]

- OEHHA State of California. The Proposition 65 List. Available online: https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/proposition-65-list (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- ECHA European Chemicals Agency. Evaluation of New Scientific Evidence Concerning DINP and DIDP. Available online: https://echa.europa.eu/documents/10162/31b4067e-de40-4044-93e8-9c9ff1960715 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Chen, C.; Chen, A.; Zhan, F.; Wania, F.; Zhang, S.; Li, L.; Liu, J. Global Historical Production, Use, In-Use Stocks, and Emissions of Short-, Medium-, and Long-Chain Chlorinated Paraffins. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7895–7904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saabome, S.; Abdul-Malik, S.U.; Adu-Poku, B.; Yoon, S. A Review on Plasticizers and Eco-Friendly Bioplasticizers: Biomass Sources and Market. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1138–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Chanpon, K.; Thitithammawong, A.; Kaesaman, A. Effect of Unmodified and Modified Epoxidized Soyabean Oils on Properties of Black-NBR Compounds and Black-NBR Vulcanizates. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 844, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Oßwald, K.; Reincke, K.; Langer, B. Influence of Bio-Based Plasticizers on the Properties of NBR Materials. Materials 2020, 13, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Tan, J.; Wang, F.; Zhu, X. Study on the Synthesis of Castor Oil-Based Plasticizer and the Properties of Plasticized Nitrile Rubber. Polymers 2020, 12, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D6866; Standard Test Methods for Determining the Biobased Content of Solid, Liquid, and Gaseous Samples Using Radiocarbon Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D5289; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—Vulcanization Using Oscillating Disk Cure Meter. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D573; Standard Test Method for Rubber—Deterioration in an Air Oven. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ISO 37; Rubber, Vulcanized or Thermoplastic—Determination of Tensile Stress–Strain Properties. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ASTM D2240; Standard Test Method for Rubber Property—Durometer Hardness. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D395; Standard Test Methods for Rubber Property—Compression Set. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- Parambath, A. Cashew Nut Shell Liquid: A Goldfield for Functional Materials; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, B.; Zhao, X.; Yue, D.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S. A combined experiment and molecular dynamics simulation study of hydrogen bonds and free volume in nitrile-butadiene rubber/hindered phenol damping mixtures. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 12339–12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Elburg, F.; Grunert, F.; Aurisicchio, C.; di Consiglio, M.; di Ronza, R.; Talma, A.; Bernal-Ortega, P.; Blume, A. Exploring the Impact of Bio-Based Plasticizers on the Curing Behavior and Material Properties of a Simplified Tire-Tread Compound. Polymers 2024, 16, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mark, J.E.; Erman, B.; Roland, M. The Science and Technology of Rubber; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 547–589. [Google Scholar]

- Ciullo, P.A.; Hewitt, N. The Rubber Formulary; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 1–72. [Google Scholar]

- Kruželák, J.; Hložeková, K.; Kvasničáková, A.; Džuganová, M.; Chodák, I.; Hudec, I. Application of Plasticizer Glycerol in Lignosulfonate-Filled Rubber Compounds Based on SBR and NBR. Materials 2023, 16, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal, A.; Hackel, N.; Grunert, F.; Ilisch, S.; Beiner, M.; Blume, A. Investigation of Rheological, Mechanical, and Viscoelastic Properties of Silica-Filled SSBR and BR Model Compounds. Polymers 2024, 16, 3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, M.; Thachil, E.T. The Effectiveness of Cardanol as Plasticiser, Activator, and Antioxidant for Natural Rubber Processing. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2010, 26, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.R. The Dynamic Properties of Carbon Black-Loaded Natural Rubber Vulcanizates. Part I. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1963, 36, 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A. Effect of dispersion on dynamic properties of filler-loaded rubbers. Rubber Chem. Technol. 1966, 39, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buaksuntear, K.; Kohl, P.; Li, Y.; Smitthipong, W. Improvement of Carbon Black Dispersion in Mussel-Inspired Composites from Epoxidized Natural Rubber Using Aromatic Interactions. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 3576–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, C.G.; Hardman, N.J. Nature of Carbon Black Reinforcement of Rubber: Perspective on the Original Polymer Nanocomposite. Polymers 2021, 13, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pielichowski, K.; Njuguna, J.; Majka, T.M. Thermal Degradation of Polymeric Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Xu, L.; Zhang, P. Investigation of aging behavior and mechanism of nitrile-butadiene rubber (NBR) in the accelerated thermal aging environment. Polym. Test. 2016, 54, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).