Abstract

Currently, in hydrotechnical engineering, such as oil and gas platform construction, floating docks, and other floating structures, the need to develop new lightweight composite building materials is becoming an important problem. Expanded clay concrete (ECC) is the most common lightweight concrete option for floating structures. The aim of this study is to develop effective composite ECC with improved properties and a coefficient of structural quality (CCQ). To improve the properties of ECC, the following formulation and technological techniques were additionally applied: reinforcement of lightweight expanded clay aggregate by pre-treatment in cement paste (CP-LECA) with the addition of microsilica (MS) and dispersed reinforcement with basalt fiber (BF). An experimental study examined the effect of the proposed formulation and technological techniques on the density and cone slump of fresh ECC and the density, compressive and flexural strength, and water absorption of hardened ECC. A SEM analysis was conducted. The optimal parameters for LECA pretreatment were determined. These parameters are achieved by treating LECA grains in a cement paste with 10% MS and using dispersed reinforcement parameters of 0.75% BF. The best combination of CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF provides increases in compressive and flexural strength of up to 50% and 61.7%, respectively, and a reduction in water absorption of up to 32.8%. The CCQ increases to 44.4%. If the ECC meets the design requirements, it can be used in hydraulic engineering for floating structures.

1. Introduction

Lightweight concrete is a promising composite material and is used in many structural sectors, including hydrotechnical engineering for the construction of oil and gas platforms, floating docks, and other floating structures [1,2]. The most popular lightweight concrete option for the construction of hydrotechnical structures, including floating ones, is expanded clay concrete (ECC) [3,4]. In the construction of floating reinforced concrete structures, one of the most important objectives is to reduce the weight of the structure without losing strength properties, and the effectiveness of ECC composites is assessed by the ratio of the material’s strength to its weight. The effectiveness of ECC in hydrotechnical engineering has been confirmed by many studies. For example, colored ECCs developed for floating reinforced concrete structures containing iron oxide pigments have demonstrated excellent mechanical properties and frost resistance from F450 to F500 [5]. The inclusion of complex plasticizing and antifreeze additives in the composition of ECC allows for significant improvement of their properties and the full use of these composites in construction in the conditions of the Far North and the Arctic [6]. Self-compacting ultra-light foam concrete with 20% recycled expanded clay content demonstrates good strength properties and increased buoyancy [7].

Despite all the potential advantages of using ECC composites in hydrotechnical engineering and for manufacturing floating structures, its actual application in this field is limited. Technological difficulties in the ECC manufacturing process are the main reason limiting its application. Lightweight expanded clay aggregate (LECA) has a cellular porous structure and high water absorption, which significantly affects the rheology of ECC mixtures [8,9]. In addition, a significant difference in the density of cement-sand mortar and LECA can lead to segregation and, as a result, to a decrease in the homogeneity of the composite structure [10]. The use of formulation and technological techniques aimed at processing the surface of LECA grains allows us to solve the above-mentioned problems in the ECC manufacturing technology and improve their strength properties. Treatment of the LECA surface with cement mixtures with the addition of glass powder and ground granulated blast furnace slag allows us to reduce its water absorption and significantly increase the strength properties of the composite, while maintaining the same density [11]. Pre-treatment of LECA with cement mortar improves its adhesion to the cement matrix and, therefore, increases compressive strength [12]. The inclusion of LECA impregnated with polyethylene glycol reduces water absorption of concrete and increases its durability [13]. Treatment of LECA with a geopolymer suspension and its inclusion in the composition of lightweight alkali-activated concrete ensures maximum compressive strength of up to 49.17 MPa [14]. Other popular formulation and technological solutions aimed at improving the properties of concrete, including ECC, are modification with mineral additives and dispersed reinforcement with various types of fiber [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The use of MS in the composition of cement-stable concrete improves its strength characteristics and increases corrosion resistance [21]. Positive results from the use of MS additive in concrete have been demonstrated in several other studies [22,23,24]. The addition of fibers to the concrete composition allows to improve its mechanical properties, reducing shrinkage, and increasing durability [25,26,27]. The most popular and most accessible type of dispersed fiber used in concrete technology is basalt fiber. For example, the introduction of 0.3% basalt fiber (BF) into the composition of ECC reduces the drying shrinkage on the 90th day by 20.67% [28]. BF in the composition of lightweight concrete in an amount of 0.3% increases its compressive and flexural strength by 24.7% and 33.9%, respectively [29]. The combination of basalt and polypropylene fibers in dosages of 0.05% and 0.1% provides an increase in compressive strength by 13.7% and tensile splitting strength by 76.3% [30]. Dispersed reinforcement of BF has a positive effect on the mechanism of concrete destruction, slowing down crack propagation through the mechanism of stress concentration transfer [31]. Similarly, other studies have shown that including BF provides improved properties of composites [32,33,34,35,36].

As seen from the review, the amount of scientific research aimed at developing strong and lightweight composite materials for the construction of floating reinforced concrete structures is currently limited. The use of lightweight porous aggregates in cement composite technology will allow for a significant reduction in density; however, the mechanical properties of the composites will also decrease [37]. In addition, technological difficulties during the preparation of fresh concrete using lightweight aggregates, caused by their high water absorption capacity and uneven distribution of aggregate grains in the cement-sand mortar, limit the use of ECC. This study is aimed at exploring and selecting formulations and technological methods aimed at obtaining ECC with improved performance properties. It is possible to increase the strength of composites, in particular ECC, intended for the construction of floating structures through the use of various formulation and technological methods and their combinations in the process of selecting compositions and manufacturing ECC [38,39,40]. The scientific novelty of this work lies in the development of new compositions of effective ECC with reinforced lightweight aggregate and dispersed fiber for the construction of floating hydrotechnical structures and the derivation of new relationships between the properties and structure of ECC and formulation and process parameters.

The aim of this study is to produce composite reinforced expanded clay concrete and basalt fiber concrete for hydrotechnical engineering for floating structures.

The objectives of the study included:

- Developing compositions of cement pastes with varying MS dosages and their preparation;

- Treating LECA with cement pastes and obtaining experimental samples of pre-treated LECA (CP-LECA);

- Developing compositions of fresh ECC using experimental samples of CP-LECA and dispersed fiber BF, as well as the production of 11 series of experimental ECC samples;

- Conducting a series of laboratory studies to evaluate the density and slump of fresh ECC, as well as the density, compressive strength, flexural strength, and water absorption of experimental ECC samples; determining the structural quality factor of the developed ECC;

- Studying the structure of the developed ECC, processing experimental data, and determining optimal formulation parameters;

- Describing the scope of application of the developed ECC.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The following raw materials were used to produce ECC:

- Portland cement CEM II A-Slag 42.5 N (PC) (Sebryakovcement, Mikhailovka, Russia). Properties: Blaine specific surface area—3050 cm2/g; initial setting time—195 min; final setting time—300 min; normal consistency—30%; bulk density—1281 kg/m3; compressive strength at 28 days—48.2 MPa; flexural strength at 28 days—7.9 MPa.

- Quartz sand (QS) (Nedra, Samara, Russia). Properties: bulk density—1365 kg/m3; apparent density—2564 kg/m3; dust and clay particle content—0.07%; fineness modulus—1.69.

- Lightweight expanded clay aggregate (LECA) (ZSM, Belgorod, Russia). Properties: fraction 10–20 mm; bulk density—349 kg/m3; strength—0.96 MPa.

- Pre-treated LECA (P-p. LECA). Manufactured in a laboratory.

- Basalt fiber (BF) (CEMMIX, Moscow, Russia). Properties: fiber length—6 to 24 mm; fiber diameter—17 µm; elastic modulus—84 GPa; lubricant—water-soluble alkali-resistant K-B42.

- Microsilica (MS) (NLMK, Lipetsk, Russia). Bulk density—150 kg/m3.

- Plasticizer PK1 (P) (Polyplast, Moscow, Russia). Properties: density—1.11 g/cm3.

The choice of source materials is determined by their availability and accessibility on the market and the compliance of their properties with regulatory requirements and research objectives. The appearance of the main raw materials required for the manufacture of ECC is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Appearance of the main raw materials: (a) cement; (b) sand; (c) LECA; (d) pre-treated LECA; (e) MS; (f) BF.

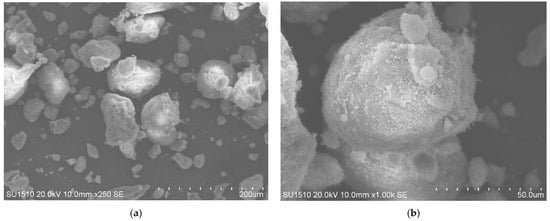

SEM images of MS particles are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SEM images MS with magnification: (a) 250×; (b) 1000×.

MS particles are spherical, angular, and plate-like in shape. Particle agglomeration is observed: smaller angular and fragmentary particles are adjacent to the surface of larger spherical particles. The results of EDS mapping of the MS particles and the full EDS spectrum, reflecting the distribution of chemical elements and their abundance, are presented in Figure 3.

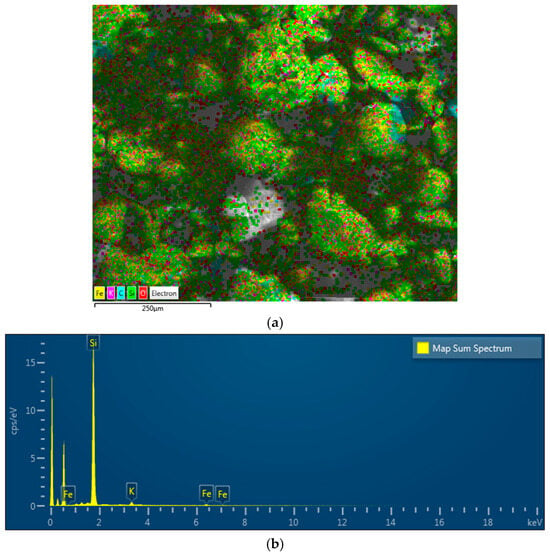

Figure 3.

EDS analysis of FA: (a) EDS mapping; (b) EDS spectrum.

From Figure 3a, it can be seen that among the predominant green zones reflecting the distribution of Si, there are multiple yellow areas related to the distribution of Fe, which corresponds to its low amount (Table 1) and indicates the distribution of Fe atoms on the surface of the MS particles. It is also worth noting that the conductive carbon adhesive tape used to immobilize the MS particles during the EDS analysis is the cause of the significant content of C. The EDS spectrum covered a certain area with the MS particles, as a result of which a significant content of C was recorded, which is presented in Figure 3a as several local blue zones. The elemental composition of MS is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Elemental composition of MS.

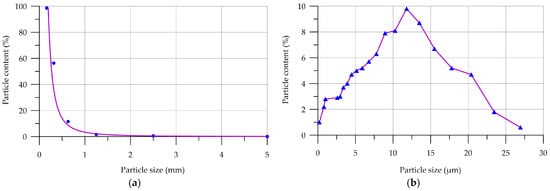

The granulometric compositions of sand and MS are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution curves: (a) QS; (b) MS.

For QS, the total residuals on sieves 2.5, 1.25, 0.63, 0.315, and 0.16 were 0%, 0.5%, 1.6%, 11.5%, 56.3%, and 98.6%, respectively, corresponding to a fineness modulus of 1.69. The MS particle distribution was as follows. The percentage of MS particles in the size range up to 5 μm was 29.3%. Most of the MS particles (68.3%) were in the size range from 5 μm to 20 μm.

2.2. Methods

In the current study, the development of the optimal ECC composition with expanded clay and basalt fiber reinforced aggregate was carried out in two main stages:

Stage 1: Surface treatment of LECA with cement paste. Before being included in the ECC mix, the LECA surface was treated with a pre-prepared cement paste modified with MS additive. The MS additive was introduced into the composition of cement pastes in an amount from 0% to 15% of the binder weight in 5% increments. The MS modification range of 0–15% is due to the results of preliminary tests and previous studies devoted to the modification of cement composites with microsilica [22,23]. The purpose of LECA surface treatment was to improve and strengthen its surface. The composition of the cement pastes is presented in Table 2. The cement pastes were prepared immediately before LECA surface treatment. Raw materials were dosed in the required quantities. PC and MS were poured into the bowl of a laboratory mortar mixer and mixed dry (60 ± 5) s. Then, mixing water was added, and the paste was mixed until a homogeneous state (180 ± 5) s. Next, the cement paste was poured into the concrete mixer with the previously poured LECA. Mixing was continued for 2–3 min until the cement paste was distributed as uniformly as possible over the entire surface of the LECA grains. The treated LECA was unloaded from the concrete mixer and evenly distributed in a laboratory pan and dried for 24 h under laboratory conditions. After drying, the LECA treated with cement paste was collected in a container and subsequently used to manufacture composites. If necessary, agglomerated LECA grains were separated manually.

Table 2.

Cement paste compositions for LECA pretreatment.

Stage 2: Production of fresh ECC and cured ECC samples. ECC was produced according to the formula presented in Table 3. BFs were introduced into the ECC composition in amounts from 0% to 1.5% of the binder mass in 0.25% increments. The range of 0–1.5% BF is because of the results of preliminary tests and previous studies [33,34].

Table 3.

ECC compositions with flow rates per 1 m3.

The preparation of fresh and hardened ECC samples included the following stages.

Stage 1. Batching and preparing raw materials in the required quantities.

Stage 2. Loading PC, QS, and CP-LECA into the concrete mixer and mixing them dry (60 ± 5) s.

Stage 3. Adding mixing water with a pre-diluted plasticizing additive to the concrete mixer and mixing the mixture (180 ± 5) s. For fiber-reinforced concrete, BF is added at this stage and the mixture is mixed for another (60 ± 5) s.

Stage 4. The finished mixture was unloaded from the concrete mixer and distributed into molds. Compaction of the molds containing the concrete mixture was performed on a vibrating platform (60 ± 5) s. Stage 5. One day after production, the ECC samples were removed from the molds and aged for 27 days at a temperature of 20 ± 2 °C and a relative humidity of 60 ± 10%.

The preparation of the ECC control mixture differed for stages 2 and 3. First, LECA and 1/3 of the mixing water with a pre-dissolved plasticizer were loaded into the concrete mixer and mixed for 180 ± 5 s. PC, QS, and the remaining water were then gradually added. Mixing was continued until a homogeneous mixture was obtained.

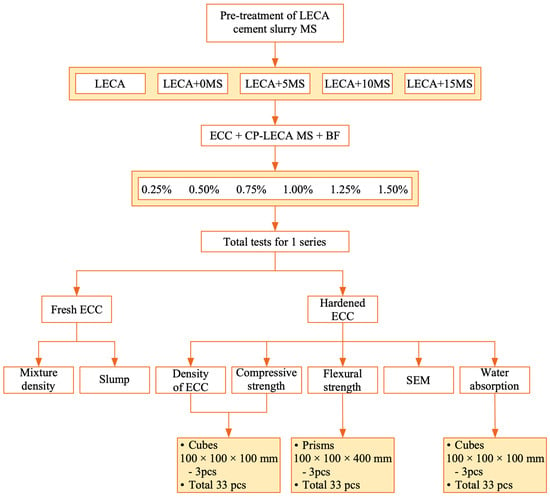

The experimental design is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Experimental Study Schematic.

The properties of ECC were determined according to standardized methodologies.

1. Density of fresh ECC [41]. The prepared fresh ECC was loaded into a pre-weighed graduated cylinder and compacted. Excess was trimmed with a metal ruler, and the graduated cylinder was weighed. The density of fresh ECC was calculated using Formula (1). The density of fresh ECC is calculated as the arithmetic mean of two density determination results differing from each other by no more than 2%.

where m is the mass of the graduated vessel with fresh ECC (g);

m1 is the mass of the empty graduated vessel (g);

V is the capacity of the graduated vessel (cm3).

2. Cone slump of fresh ECC [42]. The cone was placed on a smooth metal sheet and filled with fresh ECC in three layers from the same height, and each layer was compacted by tacking with a metal rod 25 times. Excess fresh ECC was trimmed with a metal ruler, and the cone was smoothly removed in a strictly vertical direction and placed next to the fresh ECC. Cone slump was determined by measuring the distance from the bottom surface of the rod to the surface of the fresh ECC. The average value of the cone settlement was calculated based on the results of two tests with an error of no more than 0.5 cm.

3. ECC density [43]. ECC density was determined by weighing cube specimens (100 × 100 × 100 (mm)) dried to constant mass and calculated using Formula (2). The average density was calculated as the arithmetic mean of three test results with an error of up to 1 kg/m3.

where m is the specimen mass (g);

V is the specimen volume (cm3).

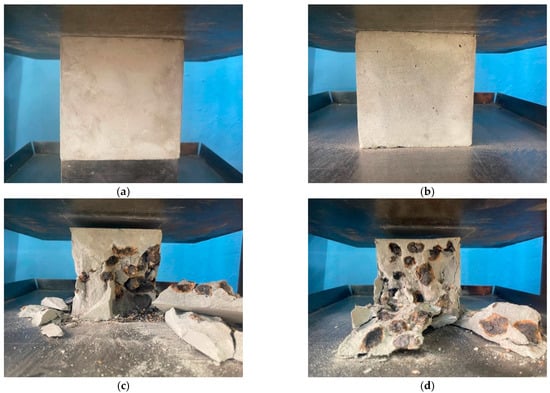

4. Compressive strength of ECC [44,45,46,47]. Compressive strength was determined on cube samples measuring 100 × 100 × 100 (mm) at the age of 28 days. The ECC specimens were mounted in a testing machine and loaded to failure at a constant rate of (0.6 ± 0.2) MPa/s (Figure 6). Compressive strength was calculated using Formula (3). The compressive strength of a series of samples was calculated as the arithmetic mean value of three samples based on the two with the highest strength, with an accuracy of 0.1 MPa.

where F is the breaking load (N);

Figure 6.

Experimental ECC specimens: control (a,c) and with treated expanded clay (b,d) during compressive strength testing: (a,b) before failure; (c,d) after failure.

A is the cross-sectional area of the specimen (mm2);

α is a coefficient accounting for the specimen dimensions (for specimens with a side of 100 mm, α = 0.95).

5. Flexural strength of ECC [48]. Flexural strength was determined on prism samples measuring 100 × 100 × 400 (mm) at the age of 28 days (Figure 7). ECC specimens were installed in a testing machine and loaded until failure at a constant rate of (0.05 ± 0.01) MPa/s. Flexural strength was calculated using Formula (4). Flexural strength of a series of samples was calculated as the arithmetic mean value of three samples based on the two with the highest strength, with an accuracy of 0.01 MPa.

Figure 7.

ECC experimental specimens in the flexural strength test setup (a) side view, (b) front view.

6. Water absorption of ECC [49]. Cube specimens (100 × 100 × 100 (mm)) were placed in a container with water so that the water level was 50 mm above the specimens. Every 24 h, the specimens were removed from the water and weighed. The test was continued until the results of two consecutive weighings differed by no more than 0.1%. Water absorption of ECC was calculated using Formula (5) with an error of up to 0.1%. The water absorption of a series of specimens was determined as the arithmetic mean of three test results for individual specimens in the series.

where mw is the mass of the dried sample (g);

md is the mass of the dry sample (g).

7. To evaluate the surface morphology and analyze the elemental composition of the MS and the microstructure of the ECC, scanning electron microscopy studies were conducted using a Hitachi SU1510 general-purpose scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an X-Max 50N energy-dispersive spectrometer (EDS) (Oxford Instruments) (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, England) integrated into the electron microscope. ECC samples for SEM analysis were collected after determining the compressive strength of the fractured specimen. Samples were taken from the most interesting areas at the phase boundaries of the fracture surface and dried for 5 h in an oven at 50–80 °C to remove excess moisture.

3. Results and Discussion

The main properties, such as density and strength, of untreated LECA and pre-treated LECA are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

LECA Properties.

The data presented in Table 4 demonstrate that treating LECA with cement pastes modified with varying amounts of MS increases its bulk density and strength. The highest bulk density and strength values were recorded for aggregate treated with a cement paste containing 10% MS. Therefore, this paste appears to be the most preferable for pre-treating LECA grains.

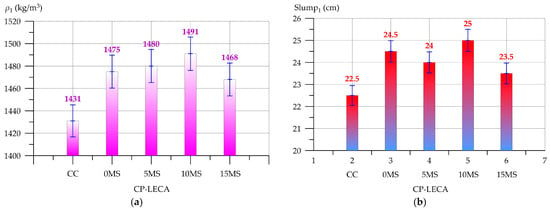

The results of determining the density and slump of fresh ECC produced using LECA pre-treated with cement pastes containing varying amounts of the modifying MS additive are presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Properties of fresh ECC depending on the CP-LECA type: (a) density (ρ1); (b) slump1.

As can be seen in Figure 8a, the inclusion of pre-treated LECA with MS-added cement pastes increases the density of fresh ECC. The minimum density of 1431 kg/m3 is observed for the fresh ECC of the control composition. The maximum density of 1491 kg/m3 is observed for the CP-LECA10MS composition, which is 4.2% higher than that of the control composition. The slight increase in the density of fresh ECC can be explained by the inclusion of CP-LECA. Because of the porous structure of expanded clay grains, they are saturated with cement paste during processing. The paste partially penetrates the upper porous layers of the expanded clay grains and sets there, thereby slightly increasing their mass. An increase in the density of fresh ECC is observed with the inclusion of aggregates treated with cement pastes with varying MS contents from 0% to 10%. The inverse relationship between the decrease in the density of fresh ECC and the inclusion of aggregates treated with cement paste with 15% MS is explained by the supersaturation of the paste with the modifying additive and a decrease in its processing ability. The slump values of fresh ECC show a tendency to increase with the inclusion of CP-LECA. The CP-LECA10MS compound exhibits the highest slump of 25 cm, which is 11.1% higher than the control compound. The surface character of LECA also changes during treatment with cement pastes. Pore sealing occurs, and the water absorption capacity of LECA decreases, resulting in improved workability.

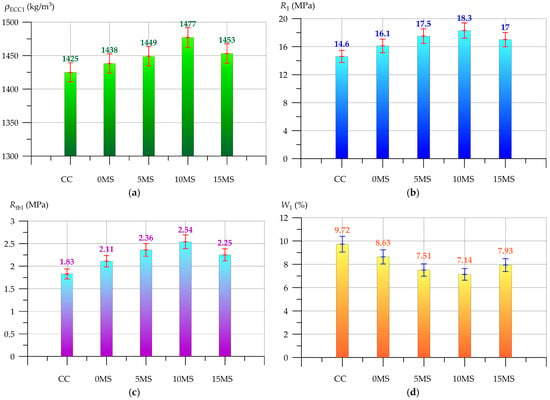

The results of determining the properties of ECC produced using CP-LECA are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Properties of cured ECC depending on the type of CP-LECA: (a) density (ρECC1); (b) compressive strength (R1); (c) flexural strength (Rtb1); (d) water absorption (W1).

Cured ECC with CP-LECA exhibits a slight increase in density. The highest density of 1477 kg/m3 was recorded for the CP-LECA10MS composition, which is 3.6% higher than the density of the control composition. As noted above, the increase in ECC density is explained by the inclusion of CP-LECA. The compressive and flexural strengths of ECC increase because of the addition of CP-LECA. As seen from Figure 9b,c the CP-LECA10MS composition has the highest compressive strength of 18.3 MPa and flexural strength of 2.54 MPa. The strength gains compared to the control composition were 25.3% and 38.8%, respectively. The inclusion of CP-LECA reduces the water absorption of ECC. The CP-LECA10MS composition has the lowest water absorption of 7.14%, which is 26.5% less than the control value. The pre-treatment process improves the strength properties of the composite by increasing the total amount of cementitious material in the matrix [12]. Also, hydration processes are more active on the CP-LECA surface, and stronger bonds are formed at the interfaces of the CP-LECA-cement-sand mortar phases. The inclusion of up to 10% MS in the cement paste composition enhances the above-described effects. MS particles act as additional crystallization centers and, because of their high pozzolanic activity, bind free Ca (OH)2, facilitating the formation of additional calcium silicate hydroxides (CSH). The formation of CSH accumulation zones at the phase boundaries increases the bond strength and the strength of the entire composite [50]. Changes in ECC properties depending on the CP-LECA type are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Changes in ECC properties depending on the CP-LECA type.

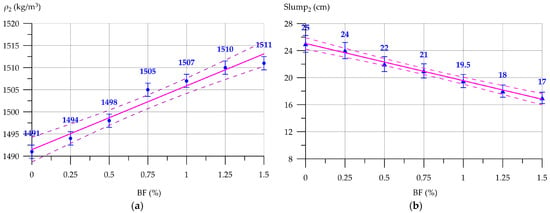

Figure 10 presents the results of property determination of fresh ECC with LECA pre-treated cement paste modified with 10% MS and different BF dosages.

Figure 10.

Properties of ECC mixtures with CP-LECA10MS depending on BF content: (a) density (ρ2); (b) slump2.

The density of ECC mixtures containing CP-LECA10MS and varying amounts of BF varied from 1491 kg/m3 to 1511 kg/m3. As the BF content increased, the workability of the mixtures decreased. At a maximum BF content of 1.5%, the slump was 17 cm, which is 32% less than the slump of CP-LECA10MS.

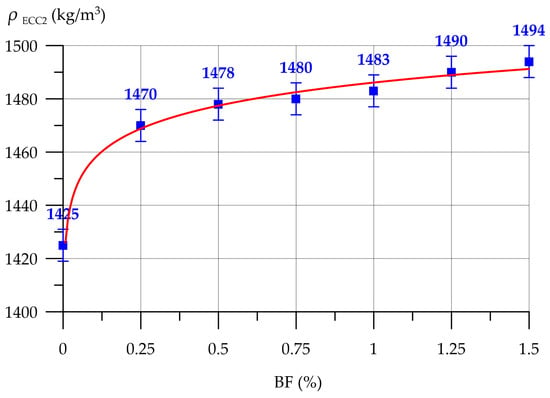

The impact of the adopted formulation and process solutions, including the combined use of CP-LECA10MS and BF, on the density, compressive strength, flexural strength, and water absorption of ECC was assessed by comparison with a control type CC mixture. The test results are presented in Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. Figure 11 shows the dependence of the ECC density with CP-LECA10MS () on the amount of BF.

Figure 11.

Density of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (ρECC2) versus BF content.

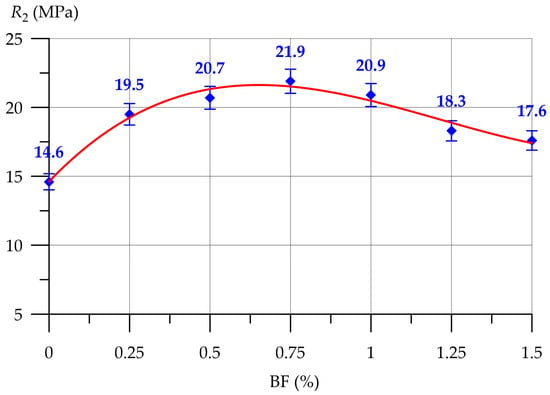

Figure 12.

Compressive strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (R2) versus BF content.

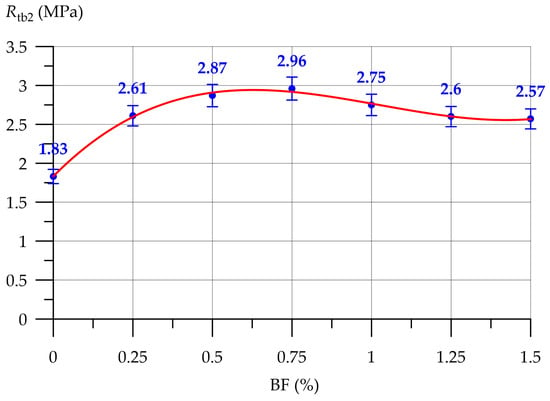

Figure 13.

Flexural strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (Rtb2) versus BF content.

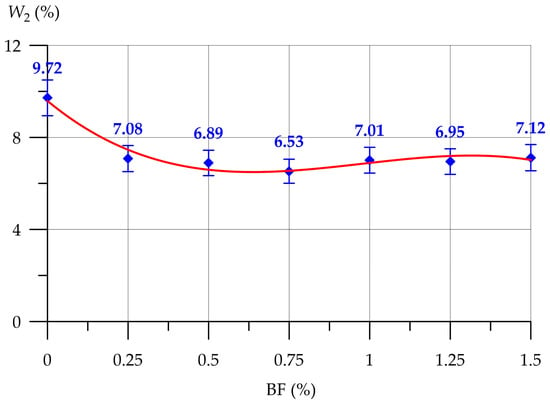

Figure 14.

Water absorption of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (W2) versus BF content.

Figure 11 shows that the inclusion of up to 1.5% BF in ECC with CP-LECA10MS does not significantly affect the density of cured ECC. The maximum density of 1494 kg/m3 was recorded for the CP-LECA10MS-1.50BF composition, which is 4.8% higher than the control composition. Figure 12 shows the compressive strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (R2) versus BF content.

The dependence of the change in compressive strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS on the BF content, shown in Figure 12, is as follows. At BF content levels from 0.25% to 0.75%, an increase in compressive strength is observed, reaching a peak value of 21.9 MPa at 0.75% BF. As the BF content further increases above 0.75%, the effectiveness of dispersed reinforcement decreases. Thus, at the optimal BF dosage of 0.75%, the maximum increase in compressive strength was 50%. For the composition with 1.5% BF, the increase in compressive strength was 20.5%. Figure 13 shows the dependence of the flexural strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (Rtb2) on the BF content.

The dependence of the change in flexural strength of ECC with CP-LECA10MS on the BF content is similar to that of R2. In the range from 0.25% to 0.75% BF, flexural strength increases with a peak value at 0.75%. The flexural strength of the CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF composition was 2.96 MPa, which is 61.7% higher than that of the control composition. Compositions with a higher BF content demonstrated smaller increases. At the maximum dosage of 1.5% BF, the increase in flexural strength was 40.4%. Dispersed BF reinforcement in an optimal amount forms additional bonds and macrostructural cells in the composite structure, which strengthens the composite structure [51,52]. Figure 14 shows the dependence of water absorption of ECC with CP-LECA10MS (W2) on the amount of BF.

Dispersed BF reinforcement at optimal dosages also further reduces the water absorption of ECC with CP-LECA10MS. The minimum water absorption value was recorded at 0.75% and amounted to 6.53%, which is 32.8% lower than the control composition. The opposite effect was observed with increasing BF content. Dispersed reinforcement of ECC with basalt fibers in optimal quantities reduces water absorption by forming denser macro- and microstructural bonds. However, when the BF content exceeds the optimal amount, the opposite effect is observed. BF fibers are unevenly distributed throughout the composite, tangle into clumps, and form weak spots and voids. It should be noted that the reduction in water absorption of ECC due to dispersed BF reinforcement is very important for composites intended for use in floating structures. The water absorption properties of materials are important for floating structures and directly impact their durability. The water absorption of the CP-LECA10MS-1.5BF composition was 7.12%, which is 26.7% lower than the control value (Table 6). The water absorption of the CP-LECA10MS-1.5BF type composition at 7.12% is somewhat higher in comparison with heavy concretes on dense aggregates, however, it is within the permissible standard values [52].

Table 6.

Changes in the properties of ECC with CP-LECA10MS depending on BF content.

The adopted formulation and technological solutions, such as pre-treatment of the LECA surface with MS-containing cement pastes and dispersed BF reinforcement, significantly improve the properties of ECC. ECC has compressive strength classes B10 (C12/15) and B15 (C16/20), which meet the requirements of regulatory and technical documentation classifying concrete composites [52]. Concrete classes B10 (C12/15) and B15 (C16/20) can be fully applied in real construction practice, including in hydraulic engineering [6,53,54]. The following key relationships were identified based on the experimental studies.

1. Density and slump of fresh ECC. Pre-treatment of LECA with MS-containing cement pastes increased the density of fresh ECC by 4.2% and the slump of the mixture by 11.1%. The inclusion of BF in fresh ECC with CP-LECA did not significantly affect the density; however, as the BF content increased, a decrease in the slump was observed.

2. Density, compressive strength, and flexural strength of ECC. The inclusion of CP-LECA in ECC provided a slight increase in density of 3.6%. ECC compositions with CP-LECA demonstrated increases in compressive and flexural strength. The maximum strength increases were 25.3% and 38.8%, respectively. The inclusion of 10% MS in the cement paste formulation was optimal and enhanced the effect of the LECA pretreatment. Additional dispersed reinforcement with 0.75% BF in CP-LECA10MS-containing formulations enhanced the effectiveness of the first formulation and technology step, providing increases in compressive and flexural strength of up to 50% and 61.7%, respectively, compared to the control formulation.

3. Water absorption of ECC. The inclusion of CP-LECA10MS and 0.75% BF had a complex positive effect and reduced water absorption by 32.8%.

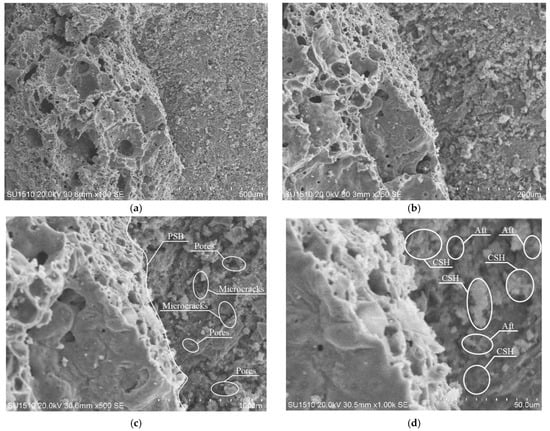

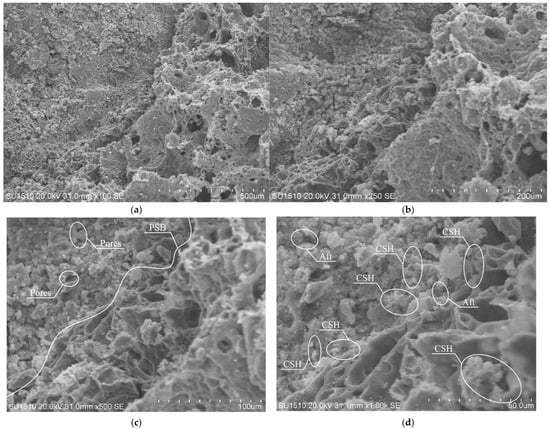

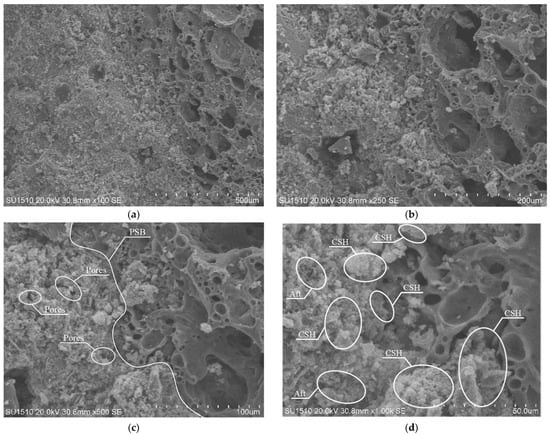

The results of SEM analysis of the ECC of the control, CP-LECA10MS, and CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF formulations are presented in Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17, respectively. The microstructural analysis of these compositions was based on the analysis of the phase boundaries between the coarse aggregate and the cement-sand mortar, as well as on the overall assessment of the structural features of the aggregate and mortar.

Figure 15.

SEM analysis of the ECC structure of the control composition: (a) ×100; (b) ×250; (c) ×500; (d) ×1000.

Figure 16.

SEM analysis of the structure of the ECC CP-LECA10MS composite: (a) ×100; (b) ×250; (c) ×500; (d) ×1000.

Figure 17.

SEM analysis of the CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF composite structure: (a) ×100; (b) ×250; (c) ×500; (d) ×1000.

The microstructure images of the ECC control composition, shown in Figure 15, clearly show the phase boundary (PSB) between the LECA and cement-sand mortar. No significant mortar accumulations were observed within the porous structure of the aggregate. The mortar structure is compact, with isolated pores and microcracks. Zones of calcium silicate hydroxides (CSH) and ettringite (AFt) accumulation are also observed (Figure 15d). The CSH and AFt phases are products of cement clinker hydration and are identified as follows. CSH consists of short silicate chains held together by calcium oxide regions, with water trapped within the structure. CSH provides the bonding of numerous other crystal hydrates. CSH accumulation zones are randomly arranged within the composite structure. AFt crystallizes as acicular structures, which can also be randomly arranged within the composite structure.

Figure 16 shows the microstructure of the CP-LECA10MS composite. The contact zone between CP-LECA and cement–sand mortar exhibits distinctive features compared to the control composite, which used coarse aggregate without pre-treatment. Cement paste clusters are present within the porous structure of the aggregate, primarily in the boundary zone. The area where the mortar adheres to the aggregate grain is dense and contains CSH clusters, indicating a high level of adhesion between CP-LECA and the ECC mortar component. The presence of CSH clusters at the interface is explained by the presence of the MS modifying additive in the cement slurry, which was applied to the surface of the coarse aggregate. The structure of the solution is compact, and zones of accumulation of calcium hydrosilicates (CSH) and ettringite (AFt) are also observed (Figure 16d).

The microstructure of the CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF composite, shown in Figure 17, is similar to that of CP-LECA10MS. Cement paste accumulations are observed within the pores of the coarse aggregate, and CSH accumulation zones are also present at the phase boundary. CP-LECA adheres tightly to the mortar. The mortar structure is compact, and zones of calcium silicate hydrous (CSH) accumulation are observed (Figure 17d). SEM analysis of the structure of the developed ECC control composition, compositions of the CP-LECA10MS and CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF types is comparable with the obtained values of strength properties. Significant accumulations of cement paste in the porous structure of the filler in the boundary zone of “CP-LECA—cement-sand mortar” contribute to the formation of stronger bonds in the PSB zones, which ensures higher values of compressive and flexural strength of ECC containing treated coarse aggregate [11,55]. The practical significance of the preliminary treatment of LECA with modified cement pastes, according to the results of the studies, is determined by the following criteria: an increase in the strength of LECA, a decrease in water absorption of LECA, the formation of denser bonds at the interfaces of the “CP-LECA—cement-sand mortar” phases.

The formulation and technological techniques used in this study to improve the properties of ECC demonstrate a positive effect. The use of processed filler and dispersion-reinforcing fiber allows for an increase in the composite class from B10 (C12/15) to B15 (C16/20). ECC with a compressive strength class of B15 (C16/20) can be used in hydraulic engineering in accordance with the requirements of regulatory and technical documentation [52]. Thus, the obtained ECC possesses the required operational properties and can be used in hydraulic engineering during the construction of oil and gas platforms, floating docks, and other floating structures. Pretreatment of LECA mitigates the effects that occur during the ECC manufacturing process. Upon mixing, the LECA grains begin to absorb moisture from the cement-sand mortar. Hydration processes occur simultaneously, forming crystalline hydrates that fuse with the LECA grains, forming a contact zone and strengthening the composite. Subsequently, under the influence of shrinkage deformations of the hardened cement paste, LECA compression occurs, which is enhanced by the expansion of saturated aggregate grains [11]. The strength properties of ECC largely depend on the compression effect and the strength of the contact zone. However, a large amount of moisture accumulated in LECA migrates back into the mortar, leading to decompression of the contact zone. Thus, reinforcing LECA grains with MS-containing cement pastes closes pores, reduces water absorption, and increases strength. CSH formation on the CP-LECA surface is more active due to unreacted cement and MS particles, resulting in a denser and stronger contact zone [53,54]. The inclusion of BF improves the properties of ECC by changing the mechanism of failure and redistribution of stresses that arise in the composite body under compressive and tensile loads. Typically, when an experimental ECC specimen with BF is subjected to a load, the fibers absorb part of the stress and dissipate it. BF delays the initiation and propagation of micro cracks in the composite matrix, thereby optimizing and increasing its strength properties [56,57,58].

The key indicator for ECC used in the construction of floating structures is the coefficient of the structural quality (CCQ). The structural quality coefficient is calculated using Formula (6):

R is compressive strength (MPa);

—density (g/cm3).

This formula allows one to evaluate the effectiveness of developed ECCs based on their strength-to-density ratio. When designing and constructing reinforced concrete floating structures, the density and strength of the composites used are critical parameters and directly impact their technical and operational performance. Increasing the strength of composites without increasing their density will ensure higher CCQ values, which is desirable for floating reinforced concrete structures.

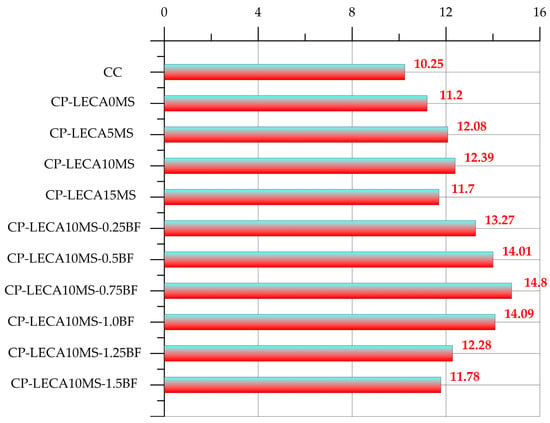

The results of determining the CCQ for the ECC developed in this study are presented in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

CCQ Results for Developed ECC.

As seen in Figure 18, LECA values vary depending on the formulation and process decisions adopted and tend to increase. After pre-treatment of LECA with cement pastes with dosages ranging from 0% to 15% MS, CCQ values range from a minimum CC of 10.2 to a maximum of 12.4 for a composition with 10% MS. The inclusion of BF at an optimal dosage of 0.75% increases CCQ to 14.8. For the best-performing composition, CP-LECA10MS-0.75BF, the CCQ increase was 44.4%. The increase in CCQ also proves the rationality of the proposed formulation and technological methods, which make it possible to obtain the most effective ECC for floating structures in terms of the strength-to-density ratio.

The results obtained in this study, the relationships, and the identified mechanisms of the influence of formulation and process techniques on the final properties of the composite are in good agreement with similar previous studies (Table 7).

Table 7.

Effect of Formulation Decisions on ECC Properties.

Based on the results of this study and similar work by other authors, it can be concluded that pre-treatment of LECA grains is a feasible formulation and technological solution that can mitigate a number of disadvantages, such as high water absorption, low strength, and insufficient adhesion of cement-sand mortar [63,64]. Dispersed reinforcement is one of the most popular formulation solutions aimed at improving the strength properties of cementitious composites. Depending on the type of fiber and composite, a series of experimental studies is required to select the optimal amount of dispersed fiber, which was carried out in this study. The inclusion of 0.75% BF further enhances the effect obtained through the use of CP-LECA in the manufacture of ECC [65,66,67,68,69,70,71].

The developed ECC possesses sufficient performance properties and, if they meet design requirements, can be fully applied in industrial and civil construction, including hydraulic engineering for floating structures. Formulation and manufacturing techniques, such as LECA pretreatment and BF dispersed reinforcement, will serve as the basis for the development of high-strength ECCs intended for the construction of floating platforms in the Far North and Arctic regions.

To obtain a more complete picture and confirm the results obtained in this study, future work will examine the long-term properties of ECCs, such as frost resistance, chloride penetration resistance, and water resistance.

4. Conclusions

In this study, effective ECC formulations containing hardened LECA and dispersed BF reinforcement were developed. Fresh ECC was evaluated for density and slump. Hardened ECC was evaluated for density, compressive and flexural strength, water absorption, and microstructural features.

- (1)

- The inclusion of pre-treated LECA and BF grains in ECC formulations does not significantly affect the density of fresh and hardened ECC. A slight increase in density was observed with the inclusion of CP-LECA, up to 4.2%.

- (2)

- Pre-treatment of LECA grains increases the slump of fresh ECC to 11.1%.Cement paste treatment seals the pores of LECA, causing the aggregate grains to absorb less water from fresh ECC, resulting in increased ECC slump values. With dispersed reinforcement, the opposite effect is observed: with increasing BF dosage, ECC slump values decrease to 32.0%.

- (3)

- ECC with CP-LECA and BF exhibits improved strength properties and reduced water absorption. The use of LECA treated with cement paste containing 10% MS provides an increase in compressive strength of up to 25.3%, flexural strength of up to 38.8%, and a decrease in water absorption of up to 26.5%. An additional modification with BF at a dosage of 0.75% increases compressive and flexural strength by up to 50% and 61.7%, respectively. Water absorption decreases to 40.4%. The improved strength properties and reduced water absorption of ECC are largely because CP-LECA has greater strength and reduced water absorption, while the dispersed fibers further bind the composite structure and redistribute stresses within it under load.

- (4)

- SEM analysis of the ECC structure demonstrates that CP-LECA10MS-based composites exhibit high levels of adhesion between the coarse aggregate grains and the ECC mortar component, as indicated by the large accumulation of CSH zones at the interfaces. The presence of cement paste with the active mineral additive MS on the surface of the coarse aggregate grains ensures a stronger bond in the CP-LECA–cement–sand mortar contact zone. The ECC mortar component has a compact structure containing pores, microcracks, and CSH and ettringite accumulation zones.

- (5)

- The developed ECCs are suitable for industrial and civil construction, including hydraulic engineering for floating structures and facilities.

- (6)

- The limitations of the study include:

- –

- technological complexities in the ECC manufacturing process;

- –

- the cellular porous structure and high water absorption of LECA, which significantly impacts the rheology of ECC mixtures;

- –

- a significant difference in the density of cement-sand mortar and LECA, which can lead to segregation and reduced homogeneity of the composite structure.

- (7)

- Further research is already underway to develop high-strength ECCs intended for the construction of floating platforms in the Far North and Arctic zones, as well as to study the long-term properties of ECCs, such as frost resistance, resistance to chloride penetration, and water impermeability. This will allow us to expand on this research and obtain a more complete picture of the application of the developed ECCs in various engineering applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.O.Ö., A.N.B., S.A.S., E.M.S., D.M.S. and A.C.; methodology, A.N.B., S.A.S., E.M.S., M.N., A.E. and Y.O.Ö.; software, M.N., A.C.; validation, S.A.S., E.M.S., Y.O.Ö., A.E., M.N. and D.M.S.; formal analysis, A.E. and A.N.B.; investigation, E.M.S., Y.O.Ö., A.E., S.A.S., E.M.S., A.N.B., A.C. and D.M.S.; resources, A.C. and D.M.S.; data curation, S.A.S. and E.M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.M.S., Y.O.Ö., S.A.S., E.M.S. and A.N.B.; writing—review and editing, D.M.S., Y.O.Ö., S.A.S., E.M.S. and A.N.B.; visualization, S.A.S., E.M.S. and A.N.B.; supervision, Y.O.Ö.; project administration, Y.O.Ö.; funding acquisition, Y.O.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the grant of the Russian Science Foundation No. 25-79-32007, https://rscf.ru/project/25-79-32007/.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administrations of Don State Technical University and Necmettin Erbakan University for their resources and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ECC | Expanded clay concrete |

| CCQ | Coefficient of structural quality |

| LECA | Lightweight expanded clay aggregate |

| CP-LECA | Lightweight expanded clay aggregate by pre-treatment in cement paste |

| MS | Microsilica |

| BF | Basalt fiber |

References

- Beskopylny, A.; Stel’MAkh, S.A.; Shcherban, E.; Saidumov, M.; Abumuslimov, A.; Mezhidov, D.; Wang, Z. Eco-Friendly Foam Concrete with Improved Physical and Mechanical Properties, Modified with Fly Ash and Reinforced with Coconut Fibers. Constr. Mater. Prod. 2025, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmand, M.; Aminzadeh, M.; Eftekhar, M. Production of evaporation suppression floating covers using ultra-lightweight alkali-activated slag concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2022, 74, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, D.; Feng, X.; Chen, J.-F. Hydroelastic analysis and structural design of a modular floating structure applying ultra-high performance fiber-reinforced concrete. Ocean Eng. 2023, 277, 114266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocherov, Y.; Agabekova, A.; Ramatullaeva, L.; Mamitova, A.; Medeshev, B.; Razikov, R.; Syrlybekkyzy, S.; Kolesnikov, A. Study of thermal-physical properties of porous ceramic insulation products. Constr. Mater. Prod. 2025, 8, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroviakov, S.; Semenova, S.; Kryzhanovskyi, V.; Zavoloka, M. Influence of Iron Oxide Pigments on the Properties of Expanded Clay Concrete for Floating Reinforced Concrete Structures. Spr. Proc. Mater. 2025, 70, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchenko, Y.; Panchenko, D.; Khafizova, E. Use of Expanded Clay Concrete for Transportation Construction in the Far North and the Arctic. In Networked Control Systems for Connected and Automated Vehicles. NN 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Guda, A., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, M.K.; Yew, M.C.; Beh, J.H.; Lee, F.W.; Lim, S.K.; Lee, Y.L. Exploring the Strength Properties and Buoyancy of Self-compacting Ultra-Lightweight Foamed Concrete Utilizing Recycled LECA. In Proceedings of 5th International Conference on Resources and Environmental Research—ICRER 2023. ICRER 2023. Environmental Science and Engineering; Yuan, C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssf, O.; Hassanli, R.; Mills, J.E.; Ma, X.; Zhuge, Y. Cyclic Performance of Steel–Concrete–Steel Sandwich Beams with Rubcrete and LECA Concrete Core. J. Compos. Sci. 2019, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroszek, M.; Rudziewicz, M.; Rusin-Żurek, K.; Hager, I.; Hebda, M. Recycled Materials and Lightweight Insulating Additions to Mixtures for 3D Concrete Printing. Materials 2025, 18, 4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherban’, E.M.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Mailyan, L.R.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Mailyan, A.L.; Shcherban’, N.; Chernil’nik, A.; Elshaeva, D. Composition and Properties of Lightweight Concrete of Variotropic Structure Based on Combined Aggregate and Microsilica. Buildings 2025, 15, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouna, K.; Ali Boucetta, T.; Maherzi, W.; Ayat, A. Enhancing the properties of expanded clay aggregates through cementitious coatings based on waste glass powder and granulated slag: Impact on lightweight self-compacting concrete performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 485, 141896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmmod, L.M.R.; Dulaimi, A.; Bernardo, L.F.A.; Andrade, J.M.d.A. Characteristics of Lightweight Concrete Fabricated with Different Types of Strengthened Lightweight Aggregates. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostofinejad, D.; Abdoli, M.; Saljoughian, A.; Karimi, A.; Eftekhar, M. Innovative energy-efficient lightweight concrete with improved thermal and mechanical properties using PCM-impregnated LECA aggregates. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 482, 141588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuttagola, I.; Prashanth, M.H. Development and performance evaluation of self-compacting lightweight alkali-activated concrete incorporating hydroton clay balls. Structures 2025, 71, 108124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federowicz, K.; Techman, M.; Sanytsky, M.; Sikora, P. Modification of Lightweight Aggregate Concretes with Silica Nanoparticles—A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sridhar, M.; Vinod Kumar, M. Structural and Sustainability Enhancement of Composite Sandwich Slab Panels Using Novel Fibre-Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kroom, H.; Elrahman, M.A.; Stephan, D.; Strzałkowski, J.; Stolarska, A.; Chung, S.-Y.; Sikora, P. Physico-mechanical properties, microstructure, and durability of ultra-high-performance lightweight concrete (UHPLWC) incorporating expanded thermoplastic microspheres and basalt fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 142868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-Q.; Yu, L.; Wang, H.-R.; Gao, S.-H.; Huang, J.-S.; Chen, X.; Shao, M.-S. LC50 fly ash microbead lightweight high-strength concrete: Mix ratio design, stress mechanism, and life cycle assessment. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Yan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xu, F.; Liu, M.; Gong, Y. Effect of Recycled Powder from Construction and Demolition Waste on the Macroscopic Properties and Microstructure of Foamed Concrete with Different Dry Density Grades. Buildings 2025, 15, 3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Su, L.; Geng, J. Pore structure characteristics, mechanical properties, and microscopic simulation of nano-SiO2-modified coal gangue coarse aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaraman, A.; Vasudevan, M.; Aravind, R.; Keerthika, M.; Prakash, J.H. Optimization of partial replacement of cement by silica fume and rice husk ash for sustainable concrete. Mater. Today. Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meskhi, B.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Shcherban, E.M.; Mailyan, L.R.; Beskopylny, N.; Chernil’nik, A.; El’shaeva, D. Insulation Foam Concrete Nanomodified with Microsilica and Reinforced with Polypropylene Fiber for the Improvement of Characteristics. Polymers 2022, 14, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Q.; Du, G.; Zhang, J. Mechanical properties of concrete with low-content rubber particles co-reinforced by silica fume and steel fiber under freeze-thaw cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chishi, A.K.; Gautam, L. Sustainable use of silica fume in green cement concrete production: A review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharun, M.; Klyuev, S.; Koroteev, D.; Chiadighikaobi, P.C.; Fediuk, R.; Olisov, A.; Vatin, N.; Alfimova, N. Heat Treatment of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Expanded Clay Concrete with Increased Strength for Cast-In-Situ Construction. Fibers 2020, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Shi, J.; Cao, X.; Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Jiang, J. A Review on the Applications of Basalt Fibers and Their Composites in Infrastructures. Buildings 2025, 15, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhao, S.; Guo, Y.; Yue, W.; Sun, C.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X. Study on the Mechanical Properties of Optimal Water-Containing Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Triaxial Stress Conditions. Materials 2025, 18, 3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Rong, X.; Wei, S.; Li, D. Investigation on Drying Shrinkage of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Concrete with Coal Gangue Ceramsite as Coarse Aggregates. Materials 2025, 18, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Song, Y.; Lee, J.C. Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete Incorporating Basalt Fiber. Buildings 2025, 15, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Lin, Z.; Xu, C.; Xu, H.; Li, B.; Shen, J. Study on the Hybrid Effect of Basalt and Polypropylene Fibers on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Yu, S. Failure Mechanisms of Basalt Fiber Concrete Under Splitting Tensile Tests and DEM Simulations. Buildings 2025, 15, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, Z.F.; Guler, S. Structural self-compacting lightweight concrete: Effects of fly ash and basalt fibers on workability, thermal and mechanical properties under ambient conditions and high temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 481, 141658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, M.; Waqar, G.Q.; Mao, J.; Javed, M.F.; Almujibah, H. Mechanical properties, microstructure and GEP-based modeling of basalt fiber reinforced lightweight high-strength concrete containing SCMs. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Q. Experimental evaluation of fracture toughness of basalt macro fiber reinforced high performance lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodur, B.; Benli, A.; Bayraktar, O.Y.; Alcan, H.G. Impact of attapulgite and basalt fiber additions on the performance of pumice-based foam concrete: Mechanical, thermal, and durability properties. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkılıç’, Y.O.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Mailyan, L.R.; Meskhi, B.; Chernil’nik, A.; Ananova, O.; Aksoylu, C.; Madenci, E. Lightweight expanded-clay fiber concrete with improved characteristics reinforced with short natural fibers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baghdadi, H.M.; Kadhum, M.M.; Shubbar, A. Evaluate the bonding strength performance between lightweight concrete and lightweight engineered cementitious composite using different percentages of cenosphere and hybrid fibers. J. Build. Rehabil. 2025, 10, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrinejad, I.; Naimi, M.A.M.; Saradar, A.; Sarvandani, M.M.; Karakouzian, M. Experimental and numerical investigation of the tensile strength of lightweight concrete including expanded clay aggregate with emphasis on the double punch test. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, J.; Gao, X.; Jia, K.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, X.; Cui, C.; Feng, J. Experimental and simulation studies on the anti-penetration performance of high-strength concrete incorporated with new green ceramsite aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, A.M.; Khajehdezfuly, A.; Poorveis, D. Structural Lightweight Concrete Containing Basalt Stone Powder. Buildings 2024, 14, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST R 57813-2017/EN 12350-6:2009; Testing Fresh Concrete. Part 6. Density. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200157335 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- GOST R 57809-2017/EN 12350-2:2009; Testing Fresh Concrete. Part 2. Slump Test. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200157288 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-7:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 7: Density of Hardened Concrete. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/811a0cf3-55e3-495a-b06e-5c302d5f2806/en-12390-7-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-1:2021; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 1: Shape, Dimensions and Other Requirements of Specimens and Moulds. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2021. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/d1c9ccee-2e5a-425e-a964-961da95d2f99/en-12390-1-2021 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-2:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 2: Making and Curing Specimens for Strength Tests. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/ae7e6a86-1cbc-455e-8b2a-8964be9087f9/en-12390-2-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/7eb738ef-44af-436c-ab8e-e6561571302c/en-12390-3-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-4:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 4: Compressive Strength—Specification for Testing Machines. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/10b1c613-819b-42d7-8f94-480cd37a666a/en-12390-4-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- EN 12390-5:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 5: Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. iTeh Standards: Etobicoke, ON, Canada, 2019. Available online: https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/5653c2c7-55a9-4bcb-8e13-5b1dfb0e3baf/en-12390-5-2019 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- GOST 12730.3; Concretes. Method of Determination of Water Absorption. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/100177301 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Malaiškienė, J.; Jakubovskis, R. Influence of Pozzolanic Additives on the Structure and Properties of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, H.A.; Mutalib, A.A.; Kaish, A.B.M.A.; Syamsir, A.; Algaifi, H.A. Development of Ultra-High-Performance Silica Fume-Based Mortar Incorporating Graphene Nanoplatelets for 3-Dimensional Concrete Printing Application. Buildings 2023, 13, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOST 26633; Normal-Weight and Sand Concretes. Specifications. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200133282 (accessed on 9 September 2019).

- Fan, T.-H.; Zeng, J.-J.; Su, T.-H.; Hu, X.; Yan, X.-K.; Sun, H.-Q. Innovative FRP reinforced UHPC floating wind turbine foundation: A comparative study. Ocean Eng. 2025, 326, 120799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.-J.; Feng, R.-M.; Yuan, X.-Y.; Song, L.-T.; Tong, G.-S.; Tong, J.-Z. A Review on Research Advances and Applications of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer in the Construction Industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SP 41.13330; Concrete and Reinforced Concrete Hydraulic Structures. Available online: https://docs.cntd.ru/document/1200095549 (accessed on 1 January 2013).

- Stel’makh, S.A.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Shcherban, E.M.; Elshaeva, D.; Chernilnik, A.; Kuimov, D.; Evtushenko, A.; Oganesyan, S. Geopolymer Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties on a Combined Binder Reinforced with Dispersed Polypropylene Fiber. Polymers 2025, 17, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskopylny, A.N.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Mailyan, L.R.; Meskhi, B.; Varavka, V.; Beskopylny, N.; El’shaeva, D. A Study on the Cement Gel Formation Process during the Creation of Nanomodified High-Performance Concrete Based on Nanosilica. Gels 2022, 8, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stel’makh, S.A.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Razveeva, I.; Oganesyan, S.; Shakhalieva, D.M.; Chernil’nik, A.; Onore, G. Compressive Strength of Geopolymer Concrete Prediction Using Machine Learning Methods. Algorithms 2025, 18, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Guo, Y.; Yao, C.; Zhao, W.; Chen, Z.; Shen, A. Flexural toughness of basalt fiber reinforced concrete under different environmental temperatures: Mesoscopic model characterization and numerical analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 499, 144063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiadighikaobi, P.C.; Muritala, A.A.; Mohamed, I.A.M.; Noor, A.A.A.; Ibitogbe, E.M.; Niazmand, A.M. Mechanical characteristics of hardened basalt fiber expanded clay concrete cylinders. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baghdadi, H.M.; Kadhum, M.M. Strengthening Fire-Damaged Lightweight Concrete T-Beams Using Engineered Cementitious Composite with Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Grid. Fibers 2025, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Lei, D.; Wan, Z.; Zhu, F.; Bai, P.; Hu, F. Early-age mesoscale deformation in lightweight aggregate concrete under different water-to-cement ratios and pretreated methods. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2025, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; Shokouhian, M.; Jenkins, M.; McLemore, G.L. Quantifying the Self-Healing Efficiency of Bioconcrete Using Bacillus subtilis Immobilized in Polymer-Coated Lightweight Expanded Clay Aggregates. Buildings 2024, 14, 3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Ismail, N.; Mourad, A.-H.I.; Rashid, Y.; Laghari, M.S. Preparation and Characterization of Expanded Clay-Paraffin Wax-Geo-Polymer Composite Material. Materials 2018, 11, 2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puzatova, A.V.; Dmitrieva, M.A.; Tovpinets, A.O.; Leitsin, V.N. Study of Structural Defects Evolution in Fine-Grained Concrete Using Computed Tomography Methods. Adv. Eng. Res. (Rostov-on-Don) 2024, 24, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Tang, X.; Guo, T. Effect of Fiber Type and Content on the Mechanical Properties of High-Performance Concrete Under Different Saturation Levels. Buildings 2025, 15, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyuev, S.V.; Klyuev, A.V.; Ayubov, N.A.; Fediuk, R.S.; Levkina, E.V. Finite Element Design and Analysis of Sustainable Mono-Reinforced and Hybrid-Reinforced Fibergeopolymers. Adv. Eng. Res. 2025, 25, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antipas, I.R. Effect of Glass Fiber Reinforcement on the Mechanical Properties of Polyester Composites. Adv. Eng. Res. (Rostov-on-Don) 2023, 23, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saprykina, T.K.; Zhadanov, V.I. Improving Theoretical Concepts of Composition Design of Dispersedly-Reinforced Concretes. Mod. Trends Constr. Urban Territ. Plan. 2024, 3, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.J.; Zeng, W.B.; Ye, Y.Y.; Liao, J.; Zhuge, Y.; Fan, T.H. Flexural behavior of FRP grid reinforced ultra-high-performance concrete composite plates with different types of fibers. Eng Struct. 2022, 272, 115020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.J.; Zeng, J.J.; Lin, X.C.; Zhuge, Y.; He, S.H. Punching Shear Behavior of FRP Grid-Reinforced Ultra-High Performance Concrete (UHPC) Slabs. J. Compos. Constr. 2023, 27, 04023031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).