1. Introduction

The rapidly increasing population, urbanization rates and industrial production worldwide are causing the rapid depletion of natural resources, waste production and environmental pollution [

1]. The food industry in particular is considered a critical sector in terms of environmental sustainability, not only in terms of its consumer production but also in terms of the very large volumes of waste generated during the production process [

2]. A large portion of the by-products resulting from food processing activities—such as fiber, hulls, and pulp—are mostly converted into animal feed, compost, or low-value-added products or disposed of in landfills. However, the high levels of organic matter, cellulose, and complex structures such as lignin in these wastes make them suitable for advanced engineering applications [

3]. This is achievable, but still, the present study does not inform us sufficiently about the low-temperature pretreatments’ (like microwave and oven roasting) influence on the physicochemical properties of oilseed cakes when incorporated into cementitious systems. A significant gap is observed in the systematic studies that compare the variants of the same food-derived waste (untreated, oven-roasted, and microwave-processed) under the same experimental conditions.

The discipline of food engineering covers not only food production processes but also the optimization of these processes, the recycling of by-products, and the economic transformation of waste. In this context, the oilseed oilcakes (such as sesame, black cumin, rapeseed, and pomegranate seed) resulting from cold pressing or solvent extraction can be evaluated not only as biofuel, feed, or food additives, but also as functional additives, due to their high carbon, protein and fiber content [

4]. The high surface area, porous morphology, and water retention capacity of these materials make them potential additives in areas such as biocomposites or the construction industry. Shivamurthy et al. [

5] reported that jatropha oil cakes act as lubricants or bio-solid lubricant fillers in epoxy composites due to their soft and oily composition, thus increasing wear resistance and enabling high load applications. Khalil et al. [

6] studied the effective use of jatropha biomass components (including oil cake) in the production of biocomposites. Besides Jatropha oil cake, sunflower, linseed, pumpkin, and castor oil cakes have also been used as filler materials for composite applications [

7,

8,

9,

10].

Food engineering encompasses all food production processes, their byproducts, and the conversion of wastes into economic value. The functional properties of biomass-based residues supplied by this discipline enable new applications in various engineering fields, such as building materials. Oilseed oil cakes are an example of highly organic-rich biological wastes that can serve as functional additives both in the food industry and in material-intensive industries, like civil engineering, owing to their fibrous structure, porous morphology, and water-holding capacity. This multifaceted bridge between the two disciplines—food engineering and civil engineering—based on sustainability offers significant opportunities not only in waste management but also in the development of environmentally friendly building materials.

Sustainability efforts, especially in the construction materials sector, have brought alternative solutions to the agenda in terms of partial or complete substitution of high-energy-consuming and high-carbon-emitting materials such as cement [

11]. Cement production is responsible for approximately 7% of global CO

2 emissions, and numerous studies are being conducted on “green cement” and alternative binder systems to reduce these emissions [

12]. A significant portion of these studies focuses on the use of industrial or agricultural wastes as supplementary cementitious materials [

13,

14,

15]. Many agricultural wastes, such as rice husk ash, sugarcane bagasse ash, palm leaf ash, and palm oil fuel ash, are reactively integrated into binder systems through high-temperature treatments. There are very few examples of dioxin-containing waste, and most of those materials require intense heat treatment, including silica or alumina post-processing additions [

16,

17,

18].

In recent years, the use of less processed or uniquely thermally pretreated biobased food waste as additives in cement-based systems has begun to attract attention. The use of such organic resources not only reduces carbon emissions but also provides microstructure improvement, increased impermeability, gains in thermal resistance, and balance in mechanical strength. Microwave heating offers a significant sustainability advantage due to its lower energy demand, faster volumetric heating, and reduced carbon emissions compared to traditional oven roasting. Various studies have shown that low-energy, rapid and homogeneous thermal treatments improve the functional properties of such wastes, particularly microwave heat treatment [

19,

20]. Furthermore, the fibrous, carbon-rich structures of these wastes contribute to the microstructure of concrete and positively affect properties such as microcrack control and consistency stabilization. However, the precise effects of thermal pretreatment on the surface chemistry, porosity, and hydration compatibility of these organic residues remain inadequately elucidated, indicating a significant knowledge deficiency.

Comprehensive reviews [

21] show that global trends in the use of seed-based waste in cement composites are increasing, and the number of publications in this field has increased rapidly, especially in the last five years. However, there are still important gaps in this literature. One of them is the integration of oilseed cakes into concrete, either unprocessed or with different thermal pretreatments. Systematic and comparative studies on how the chemical properties of these wastes change with pretreatment, their effects on the hydration process, their contributions to the microstructure, as well as their roles in high-temperature resistance are quite limited. In this context, it is important to evaluate the effects of thermal processing techniques, which are widely used in food engineering, on the performance of building materials with a holistic approach.

The use of food waste in concrete offers not only environmental sustainability but also economic, social and technical benefits. On-site processing of waste obtained from local food producers and its use in the construction sector reduces carbon emissions from transportation and provides economic advantages to concrete producers with low-cost additive systems. In addition, such applications are of strategic importance in terms of increasing university-industry collaborations and regional development.

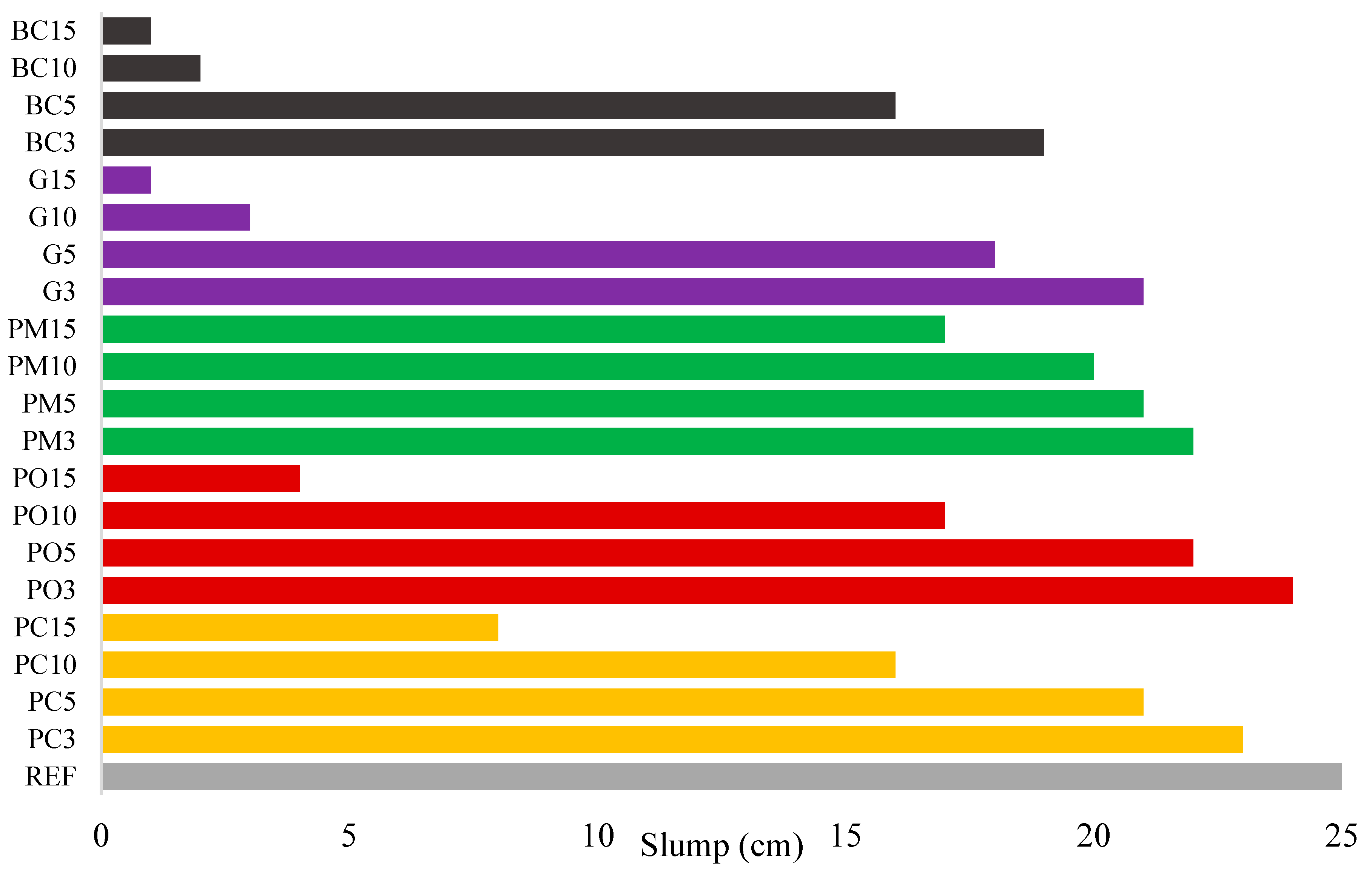

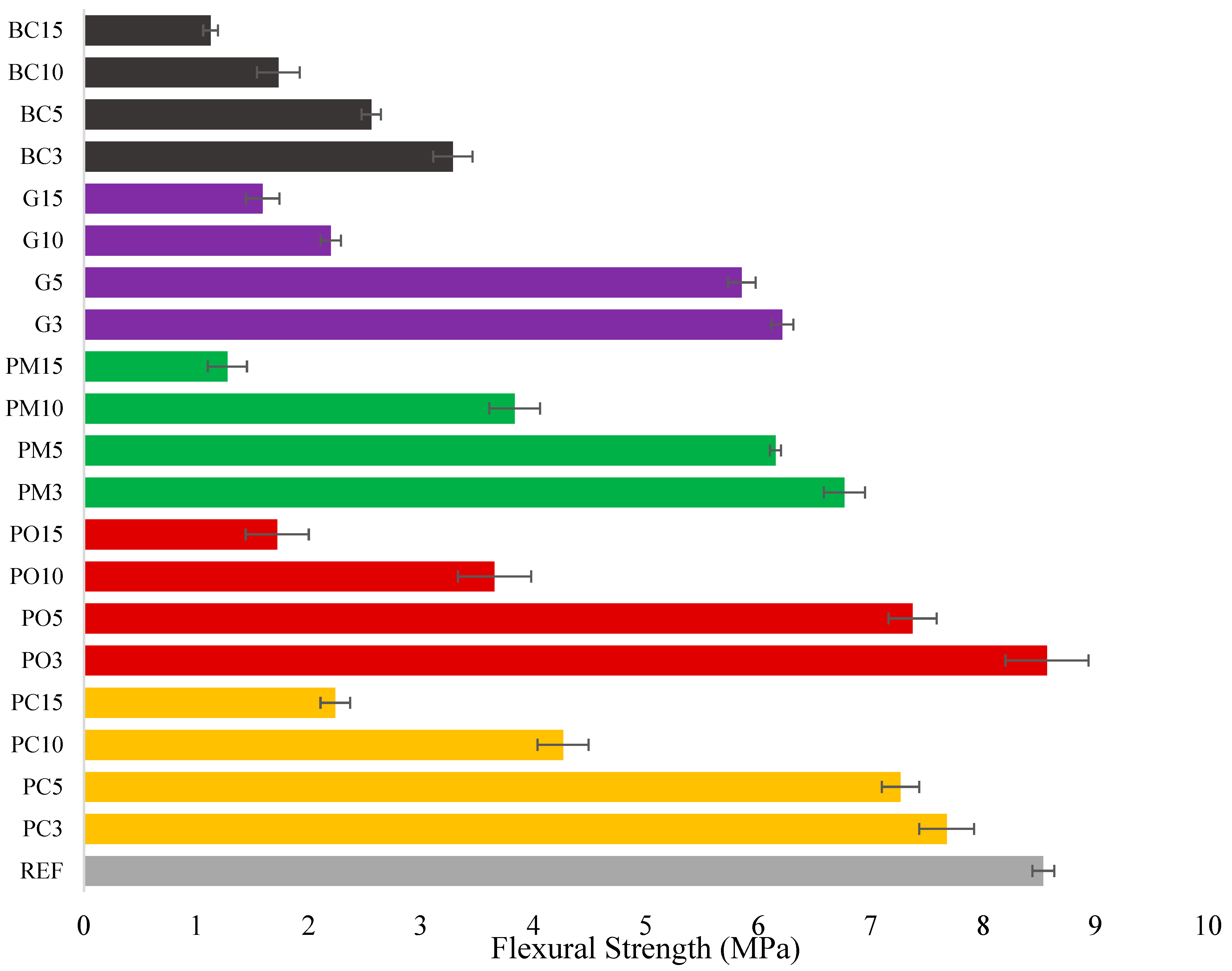

This study investigates the use of three different oilseed cakes (pomegranate seed, grape seed, and black cumin) obtained by the cold pressing method as additives in cement-based concrete systems. In particular, pomegranate seed meal was systematically compared by subjecting it to three different thermal pretreatments (untreated—control group, microwave-heated, and oven-roasted). The study aims to evaluate the effects of heat treatment techniques commonly used in food engineering on workability, mechanical strength, high-temperature resistance, and microstructure properties in cementitious systems with an interdisciplinary approach. The produced concrete samples were prepared at 0%, 3%, 5%, 10% and 15% additive rates and subjected to slump, compressive strength, bending, and tensile strength tests. In addition, SEM, XRD, FTIR, BET, and XRF analyses were performed for microstructural characterization. This study not only assesses mechanical performance but also provides a mechanistic understanding of how thermal pretreatments alter the interaction between bio-modifiers and the cement matrix, addressing an overlooked dimension in the literature.

The distinguishing feature of the present study is the evaluation of three various pretreatment conditions (untreated, oven-roasted, microwave-treated) applied to the same oilseed waste and the investigation of their effects on both the mechanical properties of the concrete and the development of the microstructure. The combination of food engineering thermal processes and sustainable concrete design has opened up a new interdisciplinary field of research that has not been thoroughly explored in the past.

3. Microstructural Analysis Results

3.1. SEM Results

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 shows the SEM figures of oilseed cakes. The figures were sorted ×50 to ×2500 for all seed cakes from above to bottom. Micrographs obtained at four different magnifications for each additive show that the particle structures have an irregular, fibrous and porous morphology. The sponge-like structure observed in BC and G additives (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) indicates high specific surface area and potential water retention capacity. SEM images of PC (

Figure 7) show that the particles have a brittle, irregular, and fractured structure. This morphology, which lacks a fibrous structure, may restrict the homogeneous distribution of the additive in the cement matrix; however, the fractured structure may provide limited advantages in terms of physical bond adhesion. In PM and PO additives (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9), particles with more compact surfaces and edge fractures were detected. Such morphological variations alter the potential for physical interaction of additives with cement paste and may indirectly affect factors such as hydration product accumulation, water retention behavior, and bond interface quality. These observations indicate that microwave treatment promotes micro-fragmentation and the formation of fine micropores, which facilitate better interfacial bonding with the cement matrix compared to untreated and oven-roasted seed cakes.

Figure 10a–e shows SEM pictures of samples with 5% oilseed meal additives. These images show how the microstructure of these concretes behaves. A visual examination shows that each addition changes the surface morphology in a different way. These changes might change how the additives physically interact with the cement matrix. Sample G5 (

Figure 10a) demonstrates that the additive particles are unevenly spread throughout the matrix, with porous areas being the most common. This means that the grape seed addition does not mix well with the matrix. Sample BC5 (

Figure 10b) demonstrates that the black cumin additive is in closer proximity to the cement paste, hence reducing void development around the additive. This more compact microstructure is qualitatively compatible with sample BC5′s strong mechanical performance. Sample PC5 (

Figure 10c) is the reference admixture group, however microcracks and uneven voids at the admixture interface show that the pomegranate pulp admixture does not do much to make the concrete denser. Sample PO5 (

Figure 10d), on the other hand, shows that the kiln-dried pomegranate seed additive is spread out more evenly and consistently throughout the cement matrix. It may be inferred that the admixture partly occupies the voids and contributes physically to the matrix. The additive particles in the PM5 sample (

Figure 10e) exhibit a surface morphology that is uneven and rough. Microporosity production is noticeable around them, even though they are partly immersed in the cement matrix. This might mean that the addition does not allow for much physical interaction. It is also evident from the SEM micrographs that the organic additives primarily establish physical adhesion rather than chemical bonding with the cement hydration products, which is consistent with previous studies on biomass-based fillers.

3.2. EDS Results

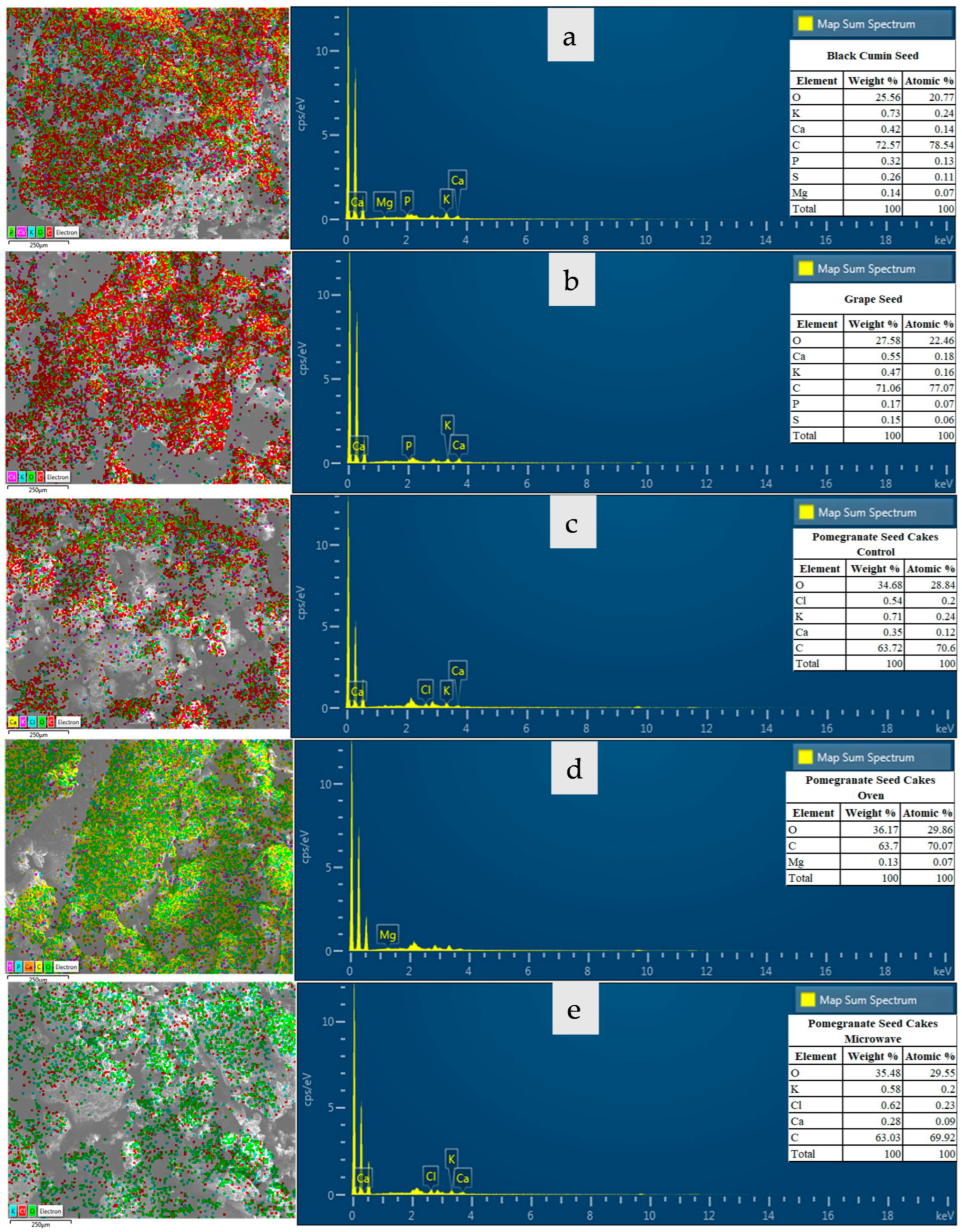

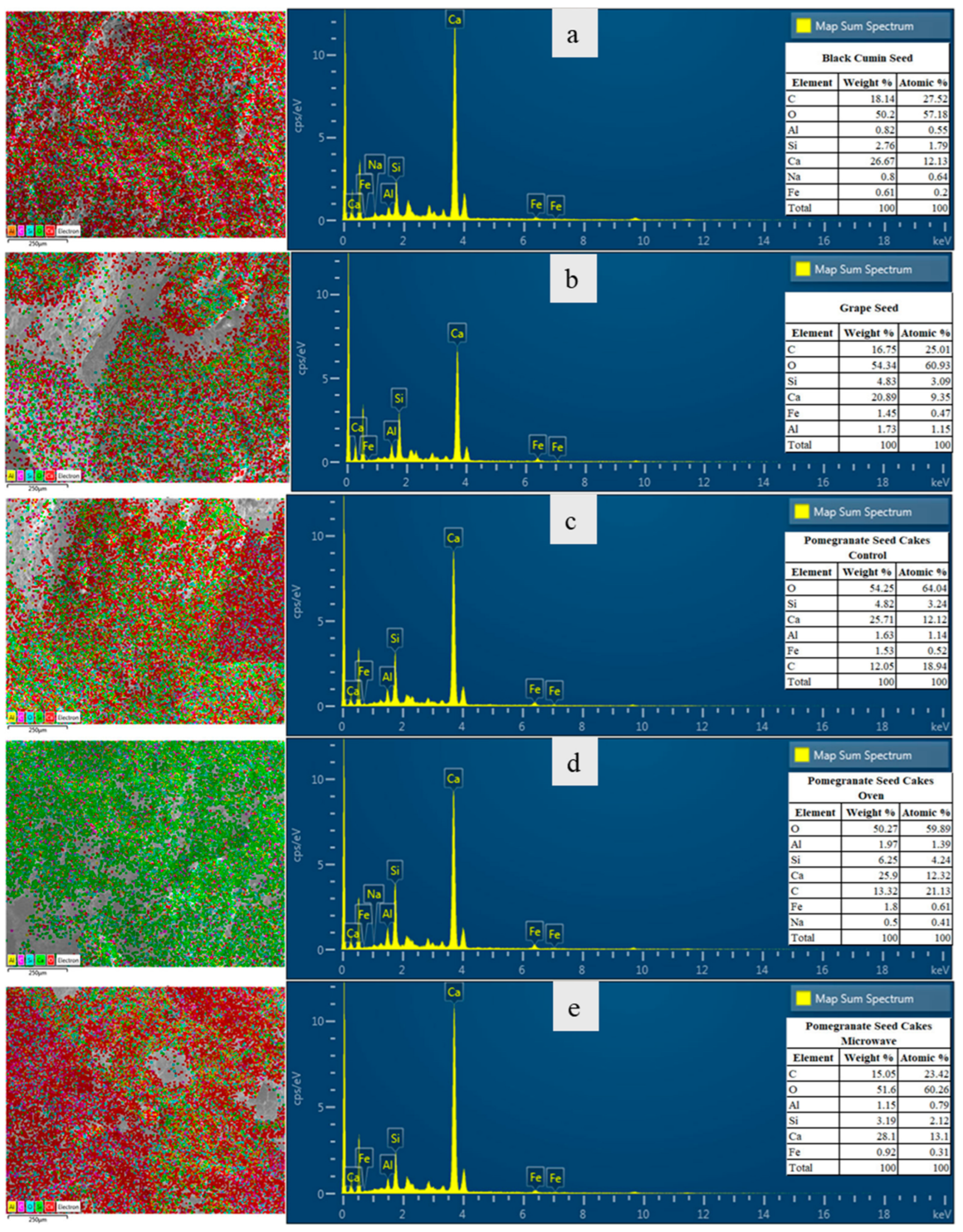

The EDS analysis results presented in

Figure 11 and

Figure 12, show significant elemental composition differences in both oilseed cake samples and concrete samples prepared with these additives. Energy dispersive EDS analyses performed on the seed meal (BC, G, PC, PO, PM) showed high levels of elements such as carbon (C), oxygen (O), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P) (

Figure 11). These components indicate the organic structure and biological mineral content of the meal. The decrease in carbon signals was evident in the PM and PO samples, implying the decrease in organic content. And yet, because EDS analysis is only semi-quantitative, the inference remains suggestive at best. This indicates that volatile organic compounds were removed by thermal treatments and the meal structure became more mineralized.

EDS analyses of concrete samples reveal the interaction between cement and oilseed meal additives in more detail, as shown in

Figure 12. Ca and Si signals indicate the presence of C–S–H (calcium silicate hydrate), portlandite (Ca(OH)

2), and other hydration products. These signals are dominant in all concrete samples. However, this Ca/Si ratio tends to be better balanced in PC5 and PM5 samples, thus implying a more homogeneous incorporation of the additives into the cement matrix. Furthermore, the higher concentrations of elements such as Mg and K in the PO5 sample indicate that heat treatment increases the concentration. High carbon content and irregular element distribution were observed in BC5 and G5 concrete samples, indicating poor hydration, low binding capacity, and limited interaction of the additives with the cement matrix.

EDS analyses showed local elemental composition of both raw additives and selected concrete regions. Thermally pretreated admixtures (especially PM and PO) were more responsive to cement based on their mineral composition, hence contributing to the hydration, while less reactive admixtures such as grape and black cumin had little chemical bonding capability with the cement matrix.

The baked PO sample had Mg, while the control sample did not. The increase in Mg content observed in the roasted samples can be attributed to thermally induced mass loss of organic components, moisture evaporation, and localized concentration effects. As the organic matrix decomposes during heating, inorganic mineral phases become more detectable in surface-level EDS analysis, leading to an apparent increase in Mg intensity. This mechanism is consistent with previous findings on thermally treated biomass materials.

3.3. FTIR Results

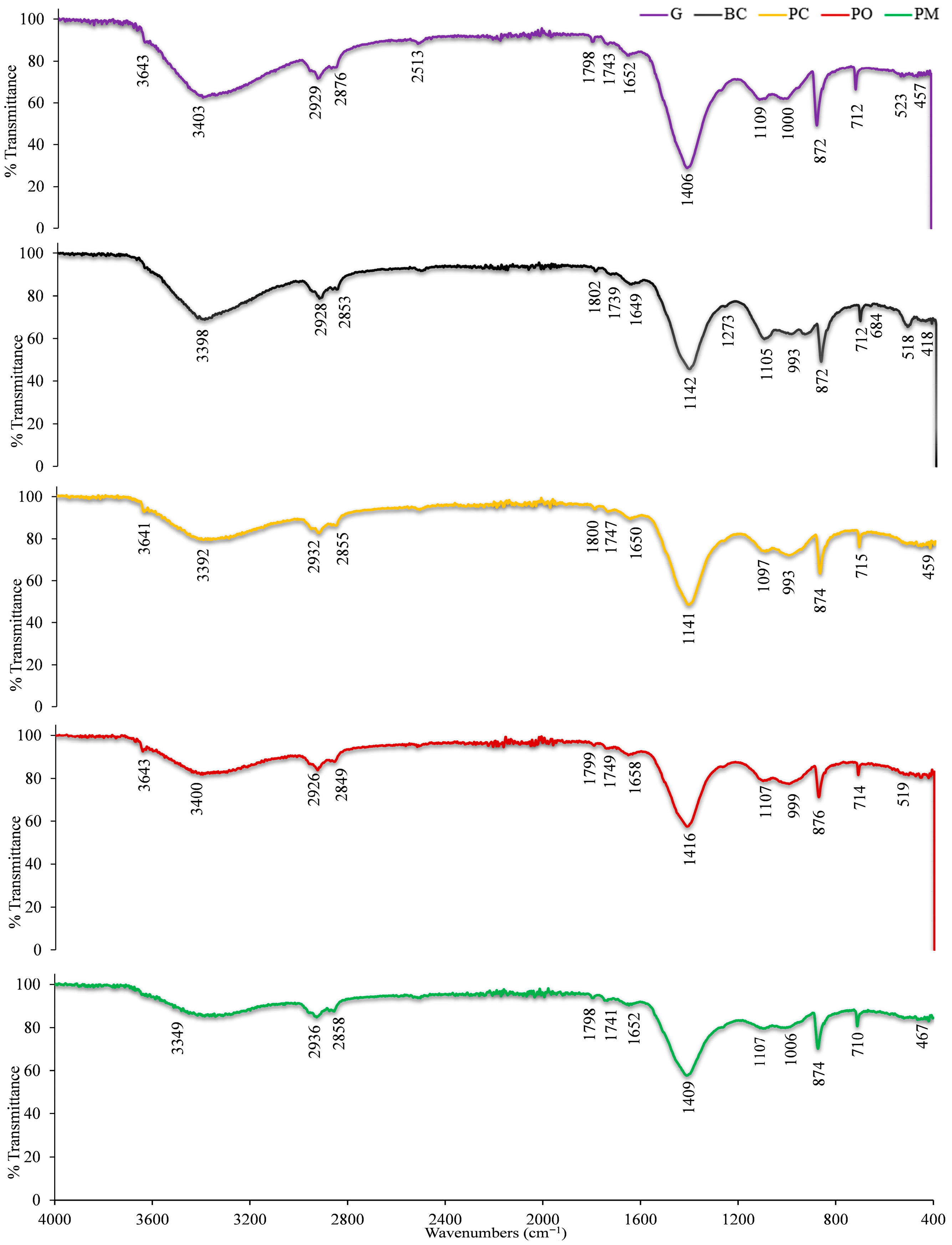

FTIR analyses were conducted on both the powdered form of the oilseed additives and concrete samples with a 5% mixture of these same oilseed additives to establish a comparison for the chemical functionalities of the additives and their interaction with the cement matrix. The samples were analyzed without drying.

The spectra for the powder samples show broad O–H stretching bands from 3300 to 3500 cm

−1 in

Figure 13. These bands represent moisture that is physically trapped by hydroxyl groups present in the cellulosic structure of the additives. This absorption intensity was lower in the microwave-treated PM sample but was higher in PO and PC samples, thus suggesting that heat treatments are capable of altering the surface chemistry of the additives and consequently the presence of hydroxyl groups. The C=O stretching vibrations detected in the 1700–1750 cm

−1 were more intense in PO and PC samples, which implies the presence of carbonyl structures such as esters, carboxylic acids, or aldehydes in the structure of the additives. The significant weakening of this signal in the PM sample indicates that microwave treatment caused fragmentation in these groups. Aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations observed in the 2850–2950 cm

−1 range were remarkably intense, especially in grape (G) and black cumin (BC) powder samples, indicating the high lipid and hydrocarbon contents of these additives. In addition, prominent peaks observed in the 1040–1100 cm

−1 range were interpreted as Si–O–Si and C–O stretching vibrations, indicating the presence of natural silicate phases or polysaccharide structures.

FTIR spectra of the concrete samples (

Figure 14) indicate the presence of cement hydration products and the level of their chemical interaction with the admixtures. Each spectrum corresponds to concrete specimens prepared with 5% replacement of cement by oilseed cakes. Strong peaks observed in the 1040–1100 cm

−1 range correspond to Ca–O–Si and Si–O–Si bonds and were particularly intense in the PM5 and PC5 samples. Compared to the untreated and oven-roasted samples, the microwave-treated additive exhibited reduced hydroxyl intensity and more distinct carbonyl rearrangements, suggesting a more stable surface structure compatible with cement hydration. This indicates that these admixtures contribute to the formation of C–S–H (calcium silicate hydrate) phases in the cement matrix and effectively establish chemical bonds with the matrix. The broad O–H bands located around 3400 cm

−1 were interpreted as indicators of structural water and physical water retained in the matrix after hydration. The intensity of this band in the PM5 and PC5 samples indicates that the admixtures entered a hydration process compatible with the binder system, while the weakening of this band in the PO5 sample suggests that firing may have reduced reactivity. In some concrete samples, moderate intensity peaks were detected in the range of 870–880 cm

−1. Those bands were characteristic of the beginning of carbonation processes and partial transformation of additives into carbonate structures inside the matrix. The preservation of characteristic cellulose-, hemicellulose-, and lignin-related bands in all concrete samples confirms that the additives do not undergo significant chemical reactions during hydration but act mainly as physical modifiers within the matrix.

FTIR analysis showed how the much pretreatment procedures of additives significantly affected their chemical functionality; such changes will be imposed directly on how these additives integrate into the cement matrix. Particularly the microwave-treated additives interacted more with cement and also more actively integrated into the hydration product structure. However, since the analyses were performed on undried specimens, the absorption peaks include contributions from physically retained moisture.

3.4. XRD Results

Diffraction patterns were obtained by XRD analyses from crude and heat-treated oilseed cake powders to characterize their mineralogical content before being integrated into cementitious mixtures, with scans performed in the 2θ range of 20–80° (

Figure 15). The XRD spectra of the additive powders exhibited crystalline peaks primarily for calcite (CaCO

3) and quartz (SiO

2), which are common in plant-based materials. Since the analysis was limited to oilseed cakes prior to cement mixing, no hydration-related phases such as portlandite or C–S–H were observed. The XRD spectrum of the PM sample reveals the structural regularity and reactivity potential of the microwave-pretreated pomegranate seed additive. Prominent peaks observed around 2θ = 29.4°, 32.2°, and 47.1° indicate the presence of mineral phases such as quartz and calcite. Microwave treatment affected the crystallinity of the oilseed cakes by increasing the intensity of quartz-related peaks, suggesting some phase restructuring during thermal processing. While these changes may influence reactivity when later mixed with cement, the XRD analysis itself was limited to the raw additive powders. The PO sample reflects the mineral phase composition of the pomegranate seed additive obtained after heat treatment. Peaks in the spectrum, particularly observed around 2θ = 18.1°, 29.3°, and 50.1°, indicate the dominance of natural components such as calcite and quartz. It is observed that some organic structures decompose with heat treatment, while certain crystalline phases become more prominent. While no distinct phase formation is observed in the regions overlapping with C–S–H and portlandite, the additive has a structure prone to carbonation and may provide a physical additive that could indirectly increase matrix integrity. XRD patterns of the PC sample indicate the mineral composition of the raw pomegranate seed pulp. The quartz peak, also observed at 2θ = 26.6°, is extremely intense, indicating that this sample consists of abundant crystalline phases. No distinct structures indicate hydration products such as portlandite or C–S–H, revealing low reactivity of the additive in its raw state. It appears that if the PC additive were included in the additive system, it would have been treated for reactivity and to serve more as a filler rather than a mechanical agent.

Sample G belongs to the grape seed additive, and its spectral analysis revealed typical mineral phase peaks originating from quartz and calcite, such as 2θ = 26.6° and 29.4°. The distinct crystalline structures indicate that this additive has undergone a high-temperature or drying process and consists of relatively stable phases. While no direct signals of hydration products are observed, the hydration products’ regular structure may create a filling effect in the cement matrix. However, the scarcity of organic phases and the high level of crystallization indicate that this additive will contribute volumetrically rather than chemically to the binder system. The BC (black cumin) sample, representing the black cumin seed inclusion, and XRD analysis revealed reflections of common quartz and calcite phases in the 2θ range of 26.6–29.4°. Although not highly intense, the peaks indicate the presence of crystalline and amorphous phases in the inclusion structure. The structure indicates low chemical reactivity of the BC inclusion during the binding process in the cement matrix, but it can contribute to homogeneous distribution as well as physical integrity. The usual carbon-rich components, of the inclusion structure, though not readily detectable by XRD, indicate the inclusion’s fibrous and carbonate content.

The absence of new hydration-related crystalline phases in the XRD patterns aligns with the expected behavior of organic biomass additives, which typically participate through microstructural and physical effects rather than chemical pozzolanic reactions.

3.5. XRF Results

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis was conducted to determine the inorganic oxide components of oilseed meal additives before they were incorporated into the concrete mixture. The results are presented in

Table 2. Potassium oxide (K

2O) and calcium oxide (CaO) were predominantly detected in all samples. K

2O reached the highest value of 1.59% in the black cumin seed (BC) sample, while the highest CaO content was measured in the grape seed (G) sample at 1.52%. Sulfate (SO

3) and phosphate (P

2O

5) contents were relatively higher, especially in pomegranate-based samples (PO and PM). XRF analysis results also show very low proportions of primary oxides with binding potential, such as SiO

2, Al

2O

3, and Fe

2O

3. The effect of these additives on the concrete matrix is to alter the physical structure (porosity, water demand, microstructure, etc.) rather than to chemically participate in cement hydration reactions.

3.6. BET Results

To evaluate the effects of additives on the pore structure of concrete samples, BET (Brunauer–Emmett–Teller) analysis was applied to concrete samples containing 5% additive content. The resulting isotherm curves and hysteresis behavior qualitatively reveal the total pore volume and pore typology of the additives in the concrete matrix (

Figure 16). The BET isotherm curve for the concrete sample containing the BC admixture exhibits a distinct hysteresis loop between the adsorption and desorption branches, indicating that the material exhibits a typical type IV isotherm. This suggests that the admixture creates a mesoporous structure in the concrete and that multilayer adsorption and capillary condensation mechanisms are effective. A rapid increase in adsorption was observed at low relative pressures, while a sudden volume increase was observed at high pressures. These observations indicate that the black cumin (BC) admixture increases porosity in the concrete matrix and alters the pore structure.

A similar type IV isotherm and a pronounced hysteresis loop were observed in the grape seed cakes (G) additived concrete sample, suggesting that the doping resulted in a high specific surface area and enhanced pore structure. The sudden increase in the curve, particularly at high relative pressures, indicates that the pores are filled by liquefaction.

The BET curve illustrated in the pomegranate seed cakes (PC) added sample figure also demonstrates the presence of mesopores, while the similar distribution of the hysteresis curve implies that the functional micro-pores in the system are not of the same type and probably in some regions have a closed or narrow-mouthed (throated) structure. This indicates that the additive may create an irregular pore structure in the concrete matrix.

In the pomegranate seed cakes microwave (PM) added sample, it appears that the hysteresis loop becomes more pronounced and the pore structure becomes wider and more throaty. This suggests that the additive exposed to microwave treatment contributes to the formation of a more developed pore network within the matrix.

The concrete sample containing the pomegranate seed cakes oven (PO) additive as shown in

Figure 16 displayed isotherm behavior that was pronounced by the existence of mesoporous characteristics. The difference between the adsorption and desorption branches indicates the presence of closed or irregular pores within the additive. This additive appears to create a more pronounced pore structure within the matrix and increase the total pore volume.

Table 3 shows that the BET analysis revealed considerable microstructural differences depending on the type of the bioadmixtures applied. The pomegranate seed meal (PO), pretreated by kiln drying, exhibited the highest specific surface area, which can be explained by the partial separation of organic components and the development of pore structure resulting from thermal treatment. In contrast, the untreated control sample (PC) had a lower surface area and a more compact and less porous structure.

The higher total pore volume observed in the microwave-treated sample is consistent with SEM observations and indicates that volumetric microwave heating induces a more fragmented and reactive microstructure.

5. Conclusions

This research examined the impacts of food-derived oilseed cakes (pomegranate, grape, and black cumin) and their thermal pretreatments (untreated, oven-roasted, and microwave-treated) as partial substitutes for cement in concrete. Based on the mechanical, microstructural, and functional analyses conducted, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The microwave-treated pomegranate seed cakes worked the best overall. They had stable workability, less slump loss, and better microstructural compatibility than the untreated and oven-roasted samples.

All organic additives made the material less strong as the substitution ratio went up, but a 3–5% replacement gave the best balance between workability, strength retention, and microstructural development.

Oven-roasted pomegranate seed cakes exhibited enhanced initial mechanical performance at 3% replacement, indicating that regulated thermal pretreatment improves surface morphology and diminishes harmful organic constituents.

The cakes made with grape seeds and black cumin seeds made the workability and mechanical properties much worse. This was mostly because they were more porous and did not mix well with the cement matrix.

SEM observations corroborated that additives interact predominantly via physical adhesion rather than chemical bonding, which is consistent with the FTIR and XRD findings that demonstrate the preservation of organic functional groups and the absence of new hydration phases.

Microwave pretreatment created smaller micropores and more broken surfaces, which helped with better dispersion and binder contact, as shown by BET and SEM results.

XRF results showed low levels of pozzolanic oxides. This means that the differences in performance are caused by changes in the physical microstructure, not by changes in chemical reactivity.

Energy analysis showed that microwave processing uses 80–85% less energy than oven roasting, making it a better choice for making bio-modifiers.

All of the additives increased the total pore volume and changed the way the microstructure behaved, even though the mechanical performance went down at high doses. This suggests that they could be useful in lightweight or specialized low-density concrete.

The results show that using food engineering thermal pretreatment methods in the design of cementitious materials could lead to the production of concrete that is low in energy and good for the environment.

This study represents an initial phase in evaluating the use of food-industry by-products as bio-modifiers in cementitious materials. The present work focused on early-age mechanical behavior and basic microstructural compatibility. It is acknowledged that long-term durability tests—such as water absorption, freeze–thaw resistance, sulfate attack, carbonation, and biological resistance—are essential for a full assessment and will be carried out in the next phase of our research. The current findings provide preliminary but necessary insight into the early performance of these additives and form a foundation for future durability-based studies.