Abstract

The investigation of the behavior of ZrB2-SiC-based ultra-high temperature ceramic (UHTC) materials under high-velocity CO2 plasma flow is of significant importance and relevance for evaluating their prospective use in the exploration of planets such as Venus or Mars. Accordingly, the degradation process of a ZrB2-30 vol.% SiC ceramic composite, fabricated by hot-pressing at 1700 °C with a 15 vol.% Ti2AlC sintering aid, was examined using a high-frequency induction plasmatron. It was found that the modification of the ceramic’s elemental and phase composition during consolidation, resulting from the interaction between ZrB2 and Ti2AlC, leads to the formation of an approximately 400 µm-thick multi-layered oxidation zone following 15 min stepwise thermochemical exposure at surface temperatures reaching up to 1970 °C. This area consists of a lower layer depleted of silicon carbide and an upper layer containing large pores (up to 160–200 µm), where ZrO2 particles are distributed within a silicate melt. SEM analysis revealed that introduction of more refractory titanium and aluminum oxides into the melt upon oxidation, along with liquation within the melt, prevents the complete removal of this sealing melt from the sample surface. This effect remains even after 8 min exposure at an average temperature of ~1960–1970 °C.

1. Introduction

ZrB2-SiC-based ceramics have attracted significant interest [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] due to their unique combination of properties. Apart from the high melting/decomposition temperatures of their constituent phases and the eutectic in this system [8], these materials exhibit reasonably good mechanical properties for ceramics, in particular, a high emissivity, high thermal conductivity and oxidation resistance at temperatures above 2000 °C [9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. This property profile is retained even under gas flows containing atomic oxygen [12,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These ultra-high temperature ceramic composites (UHTCs) are considered extremely promising for use in next-generation aerospace vehicle designs [1,18,23,24,25,26,27]. Their suitability stems from their ability to dissipate heat from critical leading edges, which experience the most severe aerodynamic heating, via a passive cooling mechanism [25,28].

In recent years, interest has been renewed not only in near-Earth space exploration but also in the exploration of other large Solar System bodies with atmospheres whose composition differs radically from that of Earth, such as Mars, Venus, and Titan. The development of descent vehicles for such missions also involves managing high thermal loads on nose cones and wing leading edges. Consequently, studying the behavior of ultra-high temperature ceramic materials in high-enthalpy gas flows that simulate the atmospheres of Venus or Mars—composed of 95–96% CO2 [29,30]—is of fundamental importance and high scientific relevance.

Previous studies have investigated the behavior of HfB2-SiC ceramics modified with graphene in a supersonic flow of dissociated CO2, including under additional laser heating [10,31,32]. It was established that exposure to a supersonic CO2 plasma flow results in a steady-state surface temperature of ~1800–1825 °C, which can be increased to ~2300–2400 °C via laser heating. This leads to the formation of a multi-layered near-surface oxidation zone, similar to that formed under air plasma flows [10]. Subsequent studies on the oxidation of ZrB2-30 vol.% SiC UHTCs in a static CO2 atmosphere—fabricated by hot-pressing [33] and by an additive manufacturing technique (extrusion printing followed by stepwise heat treatment in argon at a maximum temperature of 2100 °C) [34]—have confirmed this finding for ZrB2-based materials at temperatures up to 1400 °C and 1000 °C, respectively. Notably, lower activation energies for oxidation were reported compared to those in air. The authors of these studies highlighted the potential of ZrB2-SiC materials for high-temperature industrial applications involving oxidizing environments, such as in heat exchangers [34].

Advancing experimental approaches for the relatively low-temperature manufacturing of ultra-high temperature ceramics is essential for enabling more detailed studies of their behavior. Methods such as reactive hot pressing or spark plasma sintering [35,36,37,38,39,40] are particularly promising, as they can significantly reduce consolidation temperatures and promote a uniform distribution of modifying components. These additives are introduced to increase oxidation resistance and improve mechanical or thermophysical properties. However, these methods often involve a labor-intensive process for synthesizing the initial composite powders. Research into effective sintering additives for ZrB2/HfB2-based compositions remains highly relevant. This includes studies of carbon-based materials [41,42,43,44] and refractory metal carbides [45,46,47]. Recently, MAX phases have also been considered in this context. For example, Silvestroni et al. [48] investigated the interaction between ZrB2 and the Ti3SiC2 MAX phase during the hot pressing of a Ti3SiC2-30 vol.%ZrB2 composition. They demonstrated that even at moderate temperatures (1450 °C), a multiphase system of TiC-ZrC-TiB2-ZrSi-ZrSi2-Al2O3 with high hardness and strength is formed. In a study by Shahedi Asl et al. [49], the hot pressing of ZrB2 and Ti3AlC2 powders (with a high TiC impurity) at 1900 °C was examined. The authors reported the fabrication of a multiphase ZrB2-ZrC-Al2OC-TiB-TiC-Al2O3 system, leading to a significant improvement in fracture toughness (up to 7.8 MPa·m1/2) and hardness (31 GPa) [49]. The influence of MAX phase sintering additives (Ti3SiC2, Ti2AlC, and Cr2AlC) has also been studied for refractory boron carbide-based materials [50]. It was found that their introduction reduces the consolidation temperature by up to 800 degrees, with Ti3SiC2 providing the most beneficial effect in terms of enhancing fracture toughness while maintaining hardness.

Our previous research [51] demonstrated that employing the Ti2AlC MAX phase to consolidate an HfB2-HfO2-SiC system improves the densification process and increases oxidation resistance under thermal analysis in flowing air up to 1200 °C. Furthermore, the resulting multiphase material (Hf,Ti)B2-(Hf,Ti)(C,B)-HfO2-SiC, fabricated by hot pressing at 1400 °C, withstood stepwise heating in a subsonic flow of dissociated air generated by a high-frequency induction plasmatron. Despite a 14% porosity, the material retained a protective silicate melt on its surface at temperatures of ~1900–2000 °C without complete removal [51]. These findings indicate that the use of MAX phases as sintering aids for ZrB2/HfB2-SiC UHTCs is a rational strategy for reducing consolidation temperatures while enhancing hardness and strength. However, the formation of secondary phases, such as (Zr/Hf,Ti)(B,C), and the presence of aluminum-containing grain inclusions can have significant implications. In addition to the documented improvements in mechanical properties, these microstructural changes are expected to affect thermal conductivity and the oxidation resistance of the fabricated UHTCs under aerodynamic heating conditions, necessitating additional extensive analysis. A particularly significant and unexplored area is the behavior of ZrB2/HfB2-SiC ceramic composites under a CO2 plasma flow, which, as mentioned above, can serve as an approximation for aerodynamic heating in the atmospheres of Mars or Venus.

The objective of this work is to study the behavior of a ZrB2-30 vol.% SiC ultra-high temperature ceramic, fabricated with a 15 vol.% Ti2AlC addition, under exposure to a subsonic flow of dissociated CO2.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

The following reagents were used: ZrB2 powder (Tugoplavkie Materialy LLC., Taganrog, Russia), SiC powder (98% purity, 20 µm particle size, Osobo Chistye Veshchestva LLC., Moscow, Russia), titanium powder (>99% purity, Snabtekhmet LLC., Moscow, Russia), aluminium powder (≥98% purity, RusHim LLC., Moscow, Russia), graphite powder (>99.99% purity, Osobo Chistye Veshchestva LLC., Moscow, Russia), and KBr (>99% purity, RusHim LLC., Moscow, Russia). The Ti2AlC MAX phase was synthesized from elemental powders via the molten salt shield technique described in [52]. The synthesis was performed using a starting molar ratio of n(Ti):n(Al):n(C) = 2:1.2:0.9 at a temperature of 1100 °C in a KBr medium. The resulting product contained >97% of the target Ti2AlC phase.

The general method for fabricating ceramics using various additives, including the Ti2AlC MAX phase, has been described in previous studies [51,53]. A powder mixture with a composition of (ZrB2-30 vol.% SiC)–15 vol.% Ti2AlC was homogenized in a ball mill and subsequently subjected to hot pressing. The process was carried out in graphite dies at a temperature of 1700 °C (heating rate of 10 °C/min, holding time at the maximum temperature of 30 min) under a pressure of 30 MPa, using a Hot Press model HP20-3560-20 (Thermal Technology Inc., Minden, NV, USA) [54,55]. The sample was cooled at a rate of 10°/min between 1800 and 1000 °C and 15°/min to lower temperatures. The resulting cylindrical samples, with a diameter of 15 mm and a thickness of 3.5–4.0 mm, exhibited a relative density of 98 ± 2%. The specific sample used to study the behavior of this ceramic composite in the CO2 plasma flow had a porosity of 3%, as determined by the Archimedes method.

A high-purity cylinder gas (CO2 ≥ 99.8%; Impurities: H2O ≤ 10 vpm, JSC MGPZ, Moscow, Russia) was used to generate the CO2 plasma.

2.2. Test Facility

The degradation of the ultra-high temperature ceramic under a subsonic CO2 plasma flow was studied using a 100 kW high-frequency induction plasmatron, VGU-4 [56,57]. The diameter of the water-cooled conical nozzle outlet was 30 mm, and the distance from the nozzle to the sample was set at 30 mm. The gas flow rate was set at 2.4 g/s using a Bronkhorst MV-306 flow meter (Bronkhorst High-Tech B.V., Ruurlo, The Netherlands). The pressure in the plasmatron chamber was maintained at (5.05 ± 0.05) × 103 Pa throughout the experiment. A conceptual sketch of the VGU-4 plasmatron, used in this work and allowing us to evaluate the relative positions of the setup’s structural elements and the sample in the holder, is presented in [32]. A ceramic sample of the nominal composition (ZrB2-30 vol.%SiC)-15 vol.%Ti2AlC, in the form of a cylinder approximately 15 mm in diameter and 3.8 mm thick, was friction-fitted into a socket of a vertically oriented, water-cooled holder. The sample was mounted flush with the holder’s surface and introduced into the CO2 plasma jet at a plasmatron anode power (N) of 30 kW. The power was then increased stepwise in 10 kW increments up to 60 kW (the exposure regime is shown in Figure 1). The total duration of the experiment was 15 min.

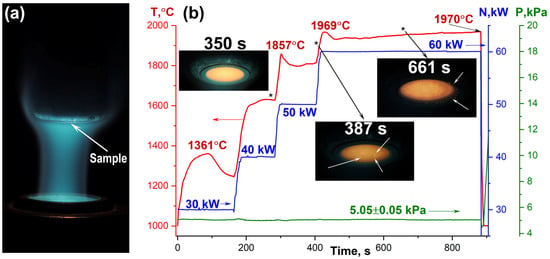

Figure 1.

(a) Photograph of the CO2 plasma flow interacting with the water-cooled holder and the mounted sample. (b) Temporal evolution of the average surface temperature at the center of the ceramic sample, plotted alongside the chamber pressure (P, kPa) and the plasmatron anode power (N, kW). White arrows indicate bright spots on the sample surface (gas bubbles) and droplets of the ejected silicate melt on the surface of the water-cooled holder. The asterisk (*) indicates the moment at which the corresponding photograph was taken.

The surface temperature at the center of the heated sample was measured using a Mikron M700S spectral-ratio IR pyrometer (Mikron Infrared Inc., Oakland, CA, USA) with an operational range of 1000–3000 °C and a target spot diameter of approximately 5 mm. The temperature distribution across the sample surface was recorded using a Tandem VS-415U thermal imager (OOO «PK ELGORA», Korolev, Moscow region, Russia). Thermal images were recorded at a set spectral emissivity ελ value of 0.7 at a wavelength of 0.9 µm, as changes in ελ were anticipated during the exposure. The temperatures in the central region obtained from the thermal imager were corrected against the color temperature measured by the spectral-ratio pyrometer. This cross-calibration allowed for the estimation of the actual spectral emissivity values and their evolution throughout the test.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the ceramic sample surface, both in its initial state and after exposure to the subsonic flow of dissociated CO2, were acquired using a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). The measurements were performed with CuKα radiation, a step size of 0.02°, and a counting time of 0.3 s per point. Phase analysis was conducted using the MATCH! software (Phase Identification from Powder Diffraction, Version 3.8.0.137, Crystal Impact, Bonn, Germany) with reference to the Crystallography Open Database (COD, version 3.7.1.143).

Raman spectra were recorded using an SOL Instruments Confotec NR500 Raman spectrometer (SOL Instruments Ltd., Minsk, Belarus), objective 40, 532 nm laser, grating—600, signal accumulation time—60 s. The laser beam was focused on the sample surface via the microscope integrated into the Raman spectrometer.

The microstructure of the sample surface and cleavages after exposure to the subsonic dissociated CO2 flow was examined using a TESCAN AMBER dual-beam focused ion beam scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM, Tescan s.r.o., Brno-Kohoutovice, Czech Republic). Imaging was performed at accelerating voltages of 5 kV and 7 kV. Energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy and elemental mapping were conducted at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Behavior of a ZrB2-SiC-Based Ceramic Composite Under Thermochemical Exposure to a Subsonic Flow of Dissociated Carbon Dioxide

Upon insertion of the water-cooled holder containing the sample into the subsonic CO2 plasma flow at the minimum anode power, a gradual increase in the average surface temperature to 1361 °C was observed over approximately 90 s (Figure 1). However, as surface reactions proceeded, a significant temperature drop of over 100 degrees occurred; by the end of this first heating stage, the temperature stabilized at 1245 °C. Increasing the power to 40 kW raised the temperature to a range of 1600–1630 °C, where it stabilized for the remainder of this two-minute stage. A different thermal response was observed upon further power increases to 50 and 60 kW. In both cases, an initial, rapid temperature surge to 1857 °C and 1969 °C, respectively, occurred within the first 15–25 s after the power change. This was followed by a temperature decrease over the next 30–45 s, and then a very slow temperature rise for the duration of the stage. Immediately before the experiment was finished, the average surface temperature reached 1970 °C. Visual examination of the sample revealed the appearance of small inhomogeneities in the surface temperature field near the end of the 50 kW stage (387 s). These became more pronounced after reaching the final 60 kW stage. Micrographs of the surface show brighter, convex regions compared to the surrounding area, probably resulting from bubble formation due to gas evolution within the silicate melt volume. Subsequently, at approximately the 11 min mark (661 s, 60 kW), a portion of the molten layer was ejected from the sample surface and splattered onto the water-cooled holder.

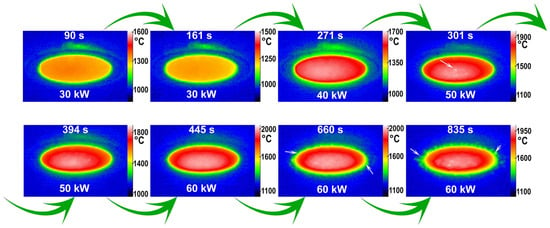

An analysis of the surface temperature distribution during exposure, conducted using a thermal imager (Figure 2), revealed a relatively uniform profile in the initial heating stages. The temperature gradient from the center to the periphery increased slightly with power, ranging from 35 to 85 °C and 70 to 130 °C for the first (30 kW) and second (40 kW) stages, respectively. A distinct change occurred during the initial temperature surge upon increasing the power to 50 kW. The formation of bright spots, with a local temperature excess (ΔT) of 20–45 °C and a size of 0.2 to 0.6 mm, was observed. These regions are attributed to the formation of protruding bubbles within the silicate melt at this temperature. The overall center-to-periphery temperature gradient at the start of this stage was about 170–175 °C. Although the average surface temperature decreased after 1.5–2 min, this gradient remained significant, fluctuating between 160–250 °C. Transition to the maximum anode power (60 kW) also induced a substantial surface temperature rise, characterized by a granular temperature distribution. The hottest regions reached peak temperatures of ~2025 °C, while the average temperature in the central area was around 1980–1990 °C. The sample’s edge registered temperatures between 1690–1760 °C. A slight decrease in the average temperature after approximately 30–35 s led to a more uniform surface temperature profile; the intensity of local hot spots diminished, and the maximum temperature did not exceed 1990 °C. However, prolonged exposure under these fixed conditions caused a gradual increase in the average surface temperature, likely due to the progressive evaporation of components from the silicate melt. This was accompanied by an increase in temperature distribution heterogeneity. By the 11th minute of exposure, evidence of silicate melt ejection from the sample surface onto the face of the water-cooled holder was observed (with the center temperature at ~1995–2025 °C), a phenomenon that became particularly pronounced after the 14th minute. It is important to note that throughout the entire thermochemical exposure, despite a surface temperature gradient of approximately 200–250 °C, no cracking of the ceramic sample occurred.

Figure 2.

Thermal images of the ceramic sample surface at specific time points during the CO2 plasma exposure, with the corresponding plasmatron anode power (N) indicated. The white arrows highlight bright spots on the sample surface (gas bubbles) and droplets of ejected silicate melt on the water-cooled holder.

After the 15 min CO2 plasma exposure, heating was terminated. The sample withstood the subsequent rapid cooling without failure or cracking. Despite visible material ejection during the final stage, the total mass loss was 2.5%, corresponding to a total recession rate of 2.86 × 10−2 g·cm−2·min−1. Conversely, the sample thickness increased by 0.8% due to oxidation.

3.2. Surface Degradation Features of a ZrB2-SiC-Based Ceramic Material Under a Subsonic Flow of Dissociated Carbon Dioxide

Analysis of the sample after testing showed that its surface was covered with a textured, porous, and glossy gray layer of oxidation products (Figure 3, inset).

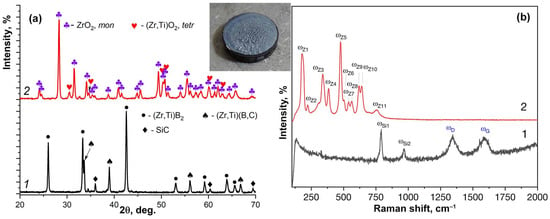

Figure 3.

(a) X-ray diffraction patterns and (b) Raman spectra of the ceramic sample surface after exposure to the subsonic dissociated CO2 flow: 1—initial sample, 2—after exposure. The inset shows a macroscopic view of the sample after the test.

X-ray diffraction analysis (Figure 3a) revealed that after oxidation in the high-enthalpy CO2 flow, the crystalline phases on the surface no longer contained the phases characteristic of the initial material. These missing phases include the complex zirconium-titanium diboride (Zr,Ti)B2 [58,59,60], silicon carbide [61] and the cubic solid solution with an approximate composition of (Zr,Ti)(B,C) [62,63,64,65], which forms during ceramic consolidation via the reaction between ZrB2 and the Ti2AlC sintering additive. The main phase on the oxidized surface was monoclinic ZrO2 [66] with a minor amount of a tetragonal (Zr,Ti)O2 oxide [67]. No crystalline aluminum-containing phases were detected on the surface, this result is consistent with observations from the oxidation of HfB2-HfO2-SiC-Ti2AlC ceramics in a flow of dissociated air [51]. The absence can be attributed to the incorporation of aluminum oxide into the silicate melt and/or its partial evaporation at the high exposure temperatures of around 1900–2000 °C.

Figure 3b presents the Raman spectra of the initial sample (1) and its oxidized surface after exposure to the CO2 plasma (2). As seen, the spectrum of the initial ZrB2-SiC-based ceramic is characterized by the presence of the characteristic SiC modes ωSi1 and ωSi2 at 791 and 968 cm−1 [68], as well as broadened D and G carbon modes (ωD and ωG) at 1344 and 1584 cm−1, respectively. These carbon bands are attributed by various authors to the decomposition products of Ti2AlC, for instance, under tribological stress [69]. Notably, the modes characteristic of the pristine MAX phase itself, located at ~260–270 and 350–360 cm−1 [70,71] are absent. This finding is consistent with the XRD data, indicating that the Ti2AlC is consumed during consolidation via its reaction with ZrB2 to form a cubic (Zr,Ti)(B,C) solid solution and by dissolving into the zirconium diboride grains. After exposure to the subsonic CO2 plasma flow, the aforementioned modes (of SiC and carbon) disappear. Instead, the spectra reveal characteristic modes of the monoclinic ZrO2 (ωZ1–ωZ11) at 178, 222, 339, 386, 477, 501, 538, 564, 620, 640 and 756 cm−1 [72]. Modes specific to the tetragonal zirconia-titania phase were not explicitly observed, probably due to being covered by the more intense signals of the monoclinic ZrO2.

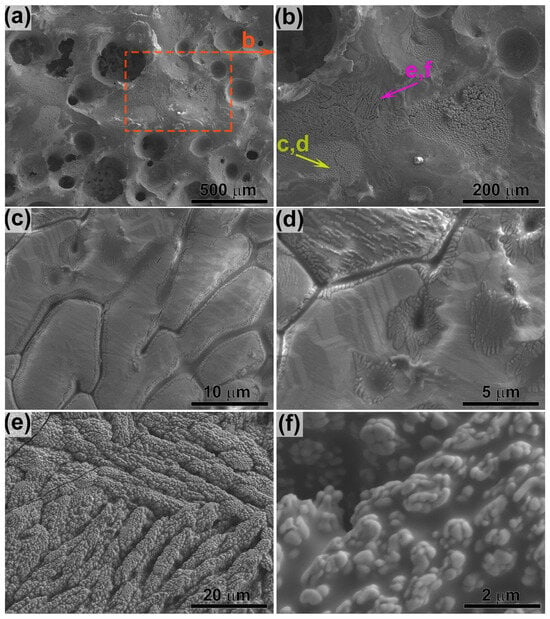

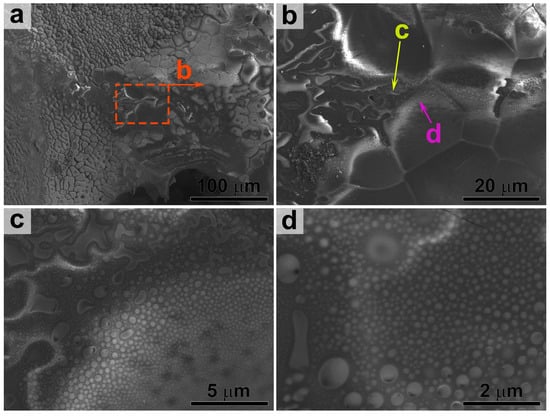

Analysis of the surface microstructure by scanning electron microscopy at a 5 kV accelerating voltage, combined with EDX data (Figure 4), confirmed that the oxidized surface is predominantly composed of zirconia (ZrO2) particles, which protrude through a layer of silicate melt. It is important to note that the formation of new bubbles on the surface continued throughout the entire CO2 plasma exposure, up until the end of the experiment. This observation provides direct evidence that a silicate melt, with suspended ZrO2 particles, was present on the surface during the test. Specifically, EDX analysis of a large surface area (1100 × 850 µm) revealed an average n(Zr):n(Si) atomic ratio of 1.7. However, this ratio decreased to approximately 0.5 in micro-regions dominated by the silicate melt. The ZrO2 particles size protruding from the melt varied across different areas, ranging from 0.2 to approximately 1 µm. Furthermore, in regions of particle accumulation, there were indications of particle alignment, likely induced by the melt flow due to gas evolution.

Figure 4.

SEM micrograph of the oxidized surface of the ceramic sample. The image was acquired at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Increasing the accelerating voltage to 7 kV enabled a more detailed study of the structure within the silicate glass region (Figure 5). This analysis confirmed that the volume of the glass underwent phase separation into two immiscible liquid phases, a phenomenon known as liquation. As noted in the fundamental work by Opeka [73], such phase separation should lead to an increase in the melt’s viscosity and a reduction in the oxygen diffusion rate through the bulk. The occurrence of phase separation in this case is most probably connected to the Ti4+ presence in the ceramic composition. This correlation is supported by another study [73], where the introduction of TiB2 also led to a reduced mass gain during oxidation at 1300 °C compared to the base ZrB2-20 vol.%SiC material. The increase in melt viscosity presumably prevented the complete evaporation or ejection of the protective silicate melt layer from the surface, even at temperatures of ~1900–1970 °C. An analogous effect was previously observed by our group for an HfB2-HfO2-SiC-Ti2AlC ceramic material exposed to a subsonic flow of air plasma [51].

Figure 5.

SEM micrograph of the silicate melt region on the oxidized ceramic surface, acquired at an accelerating voltage of 7 kV.

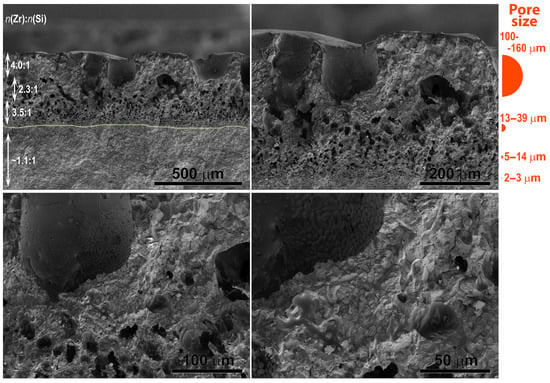

Study of the ceramic sample cleavage oxidized in the CO2 plasma (Figure 6) revealed a total degradation depth of approximately 390–420 µm. Furthermore, a systematic variation in pore size was observed throughout this near-surface region. The smallest pores (2–3 µm) are formed closest to the unaffected ceramic bulk. At a depth of 320–380 µm from the surface, a layer with larger pores, measuring 5–14 µm, is located. The above layer, located at a depth of 230–320 µm from the surface, is characterized by even larger pores, predominantly in the range of ~13–39 µm. The uppermost layer is a loose, friable zone featuring large gas bubbles with diameters of 100–160 µm. As these bubbles approach the very surface, they rupture, forming distinct surface craters. The interior surfaces of these bubbles, as well as the overall oxidized surface of the sample, are lined with ZrO2 particles that protrude from the amorphous glassy matrix.

Figure 6.

SEM micrograph of cleavage surface of the ZrB2-SiC-based ceramic sample after exposure to the subsonic dissociated CO2 flow.

A notable finding is that within a ~100–150 µm thick sub-surface layer directly adjacent to the surface, the n(Zr):n(Si) atomic ratio is approximately 4:1, which is even higher than on the surface itself. This suggests that the average surface analysis included regions dominated by the silicate melt, diluting the apparent Zr concentration. In the transition layer between the zones of large and small pores, this ratio decreases to approximately 2.3:1. This can be related to the lower temperature in this region—resulting from the low thermal conductivity of the porous ZrO2 layer—reduces the evaporation rate of the melt components. Deeper within the sample, the n(Zr):n(Si) ratio increases again to ~3.5:1, identifying this as the SiC-depleted layer. The mechanism likely involves the oxidation of SiO to SiO2 at the layer’s upper boundary, facilitated by oxygen diffusing through the melt, coupled with active oxidation of SiC at its lower boundary. Furthermore, a systematic increase in titanium and aluminum content was observed with depth. This gradient is presumably a consequence of the evaporation of their respective oxides at high temperatures of the exposed surface.

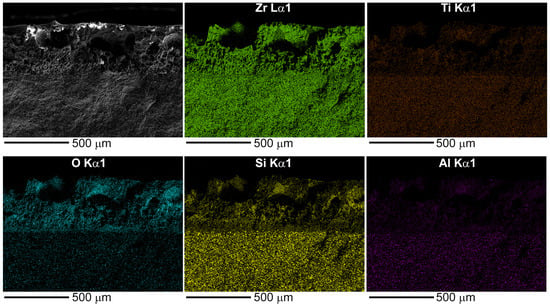

Elemental mapping of Zr, Ti, Si, Al, and O across the cleavage (Figure 7) confirms that the thickness of the degraded zone is approximately 400 ± 20 µm. Qualitatively, the maps indicate a depletion of silicon, aluminum, and titanium within the oxidized layer compared to the bulk material. A distinct region approximately 100 µm thick, adjacent to the unaffected ceramic, can be identified as the SiC-depleted layer. As evidenced by the maps, this layer contains a significant amount of oxygen. This confirms that, in addition to the active oxidation of SiC yielding volatile SiO, the oxidation of ZrB2 resulting in solid ZrO2 also occurs within this zone.

Figure 7.

SEM micrograph of the cleavage surface of the ultra-high temperature ceramic after CO2 plasma exposure and the corresponding elemental distribution maps for Zr, Ti, O, Si, and Al.

In summary, it can be concluded that the introduction of the Ti2AlC MAX phase additive into the composition of the initial powder for hot pressing not only promotes the densification of the ZrB2-30 vol%SiC ultra-high-temperature ceramic, but also affects the oxidation resistance of the composite as a whole in a subsonic flow of dissociated CO2. The interaction of ZrB2 with Ti2AlC, as shown in schemes (1–3), results in the formation of solid solutions of zirconium–titanium diboride, cubic titanium–zirconium monoborocarbide, and, most likely, small inclusions of Al2O3 (as noted in [48,49]) due to the reaction of aluminum that did not evaporate during hot pressing with oxide impurities at the grain boundaries of ZrB2 and SiC.

ZrB2 + Ti2AlC ⟶ (Zr,Ti)B2 + (Zr,Ti)(B,C) + Al

ZrO2 + ZrB2 + Al ⟶ Al2O3 + ZrB

SiO2 + Al ⟶ Al2O3 + SiO↑

As a result, the traditional oxidation mechanism of ZrB2(HfB2)-SiC ceramics by atomic oxygen formed through the CO2 molecule dissociation is supplemented by the oxidation of the newly formed (Zr,Ti)(B,C) phase, producing titanium dioxide as a result. TiO2 and the Al2O3 inclusions present in the ceramic are glass-forming oxides capable of modifying the borosilicate melt layer produced during the oxidation of ZrB2 and SiC.

In summary, this experiment resulted in the formation of a multi-layered near-surface degradation zone, a morphology characteristic of ZrB2-SiC-based ceramics exposed to high-enthalpy dissociated air flows. The specific test conditions, despite maintaining a surface temperature of 1950–1970 °C for a significant duration (~8 min), led to an intermediate scenario. This outcome lies between the low-temperature regime (<1750–1850 °C), where a continuous, protective silicate melt layer is preserved, and the high-temperature regime (>2200–2500 °C), characterized by the complete removal of this layer [19]. The prolonged retention of the silicate melt residue on the surface can be attributed to the incorporation of more refractory titanium and aluminum oxides (melting temperatures of 1830–1870 °C [74] and 2050–2070 °C [75], respectively) into its composition, which reduced the evaporation rate of its components even at elevated temperatures. Furthermore, the fact that the silicate melt, along with the dispersed ZrO2 particles, did not fully liquefy and undergo intensive ejection by the gas stream at ~2000 °C is likely due to an increased refractoriness of the glassy phase and a significant increase in the melt viscosity induced by phase separation (liquation).

Nevertheless, the viscosity of the resulting silicate melt, when doped with aluminum and titanium oxides (the oxidation products of the decomposed Ti2AlC integrated into the UHTC structure), can likely be tuned within certain limits. This could be achieved by varying the MAX phase content in the ceramic composition or by selecting a different sintering additive. For instance, using Ti3AlC2 or Ti3SiC2 instead of Ti2AlC may offer a pathway to engineer the melt’s protective properties.

4. Conclusions

The behavior of an ultra-high temperature ceramic composite based on the ZrB2-SiC system, fabricated with a 15 vol.% Ti2AlC MAX phase sintering additive, was studied under a subsonic dissociated carbon dioxide flow. It was demonstrated that the formation of an additional cubic (Zr,Ti)(B,C) phase during consolidation has no significant impact on the overall UHTC oxidation mechanism. A 15 min thermochemical exposure at temperatures up to 1970 °C resulted in the formation of a multi-layered near-surface oxidation zone approximately 400 µm thick. This zone consists of a lower SiC-depleted layer and an upper layer containing large pores (up to 160–200 µm), where ZrO2 particles are distributed within a silicate melt. Furthermore, it was established that despite an average surface temperature of ~1960–1970 °C being maintained for 8 min, the silicate melt was not completely evaporated or removed by the gas flow. This remarkable retention is attributed to two key factors: first, the incorporation of more refractory titanium and aluminum oxides (from the oxidation of the MAX phase additive) into the melt, and second, a significant increase in the melt’s viscosity due to phase separation.

This study provides the basis for initiating systematic research into the oxidation behavior of ultra-high temperature ceramics based on ZrB2(HfB2)-SiC systems, modified with various chemical components, under aerodynamic heating in a CO2 atmosphere. Such investigations are crucial for the development of thermal protection systems for missions to celestial bodies with CO2-rich atmospheres, such as Mars or Venus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P.S. and A.V.C.; methodology, A.F.K. and N.T.K.; investigation, A.V.C., E.P.S., N.P.S., I.V.L., A.S.L., I.A.N., K.A.B., T.L.S. and A.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.S. and A.V.C.; writing—review and editing, N.P.S., I.V.L., A.S.L., I.A.N., K.A.B., T.L.S., A.S.M. and A.F.K.; visualization, E.P.S., N.P.S. and A.V.C.; supervision, A.F.K. and N.T.K.; project administration, A.V.C. and E.P.S.; funding acquisition, E.P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No. 24-23-00561, https://rscf.ru/en/project/24-23-00561/, accessed on 25 November 2024).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Simonenko, E.P.; Sevast’yanov, D.V.; Simonenko, N.P.; Sevast’yanov, V.G.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Promising Ultra-High-Temperature Ceramic Materials for Aerospace Applications. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 58, 1669–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajpai, S.; Singh, K.P.; Setia, P.; Venkateswaran, T.; Balani, K. Microstructure and Interfacial Stability of Diffusion Bonded HfB2-SiC and ZrB2-SiC Based Composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irom, E.; Zakeri, M.; Razavi, M.; Farvizi, M. ZrB2-Based Ultrahigh-Temperature Ceramic with Various SiC Particle Size: Microstructure, Thermodynamical Behavior, and Mechanical Properties. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2025, 22, e14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, L.; Guo, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, B.; Bai, S.; Ye, Y. Accelerated Hardness Optimization of Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics via Generative Adversarial Network–Enhanced Active Learning. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 258, 114038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Yin, J.; Tang, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhang, H.; Zuo, J. Microstructure and Ablation Behaviors of ZrB2 and La2O3 Modified C/C-SiC-ZrC Composites Prepared by Reactive Melt Infiltration. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 42427–42437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Zhang, S.; Liu, K.; Chen, F. Vat Photopolymerization-Based Additive Manufacturing of ZrB2-Based Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics Using Low-Absorbance Precursors. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shershov, Y.M.; Orbant, R.A.; Bannykh, D.A.; Utkin, A.V.; Svintsitskiy, D.A.; Baklanova, N.I. Zirconium Diboride-Based Slurries with Readily Controlled Viscosity for Preparing Ceramic Matrix Composites. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 25281–25289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordan’yan, S.S. Interaction Regularities in SiC-MeIV-VIB2 Systems. J. Appl. Chem. 1993, 66, 2439–2444. (In Russia) [Google Scholar]

- Naik, A.K.; Kallien, G.; Schell, G.; Patel, M.; Laha, T.; Roy, S. A Comparative Study of Structural, Mechanical, and Thermal Shock Properties in ZrB2-B4C-SiC-LaB6 Functionally Graded and Non-Graded Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1036, 182159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; Chaplygin, A.V.; Kotov, M.A.; Yakimov, M.Y.; Lukomskii, I.V.; Galkin, S.S.; Shemyakin, A.N.; Solovyov, N.G.; Lysenkov, A.S.; et al. Oxidation of Ceramic Materials Based on HfB2-SiC under the Influence of Supersonic CO2 Jets and Additional Laser Heating. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Meng, S.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, Q.; Niu, J. Effects of Oxidation Temperature, Time, and Ambient Pressure on the Oxidation of ZrB2–SiC–Graphite Composites in Atomic Oxygen. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 1855–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciti, D.; Vinci, A.; Zoli, L.; Galizia, P.; Mor, M.; Fahrenholtz, W.; Mungiguerra, S.; Savino, R.; Caporale, A.M.; Airoldi, A. Elevated Temperature Performance: Arc-Jet Testing of Carbon Fiber Reinforced ZrB2 Bars up to 2200 °C for Strength Retention Assessment. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 14, 9221022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, A.; Zhang, C.; Boesl, B.; Agarwal, A. Synthesis of Hf6Ta2O17 Superstructure via Spark Plasma Sintering for Improved Oxidation Resistance of Multi-Component Ultra-High Temperature Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Zeng, Q.; Jin, H.; Wang, L.; Xu, C. Evaluation of Atomic Oxygen Catalytic Coefficient of ZrB2–SiC by Laser-Induced Fluorescence up to 1473 K. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 075207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, Z.; Deng, Y.; Han, J.; Li, D.; Li, W. Fracture Strength and Toughness Evolution in ZrB2-SiC-Si/SiCw Composites Exposed to Air up to 1550 °C. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2026, 135, 107528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potanin, A.Y.; Astapov, A.N.; Pogozhev, Y.S.; Rupasov, S.I.; Shvyndina, N.V.; Klechkovskaya, V.V.; Levashov, E.A.; Timofeev, I.A.; Timofeev, A.N. Oxidation of HfB2–SiC Ceramics Under Static and Dynamic Conditions. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Simonenko, N.P.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; Chaplygin, A.V.; Sakharov, V.I.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Nagornov, I.A.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Effect of 2 Vol % Graphene Additive on Heat Transfer of Ceramic Material in Underexpanded Jets of Dissociated Air. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 67, 2050–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecere, A.; Savino, R.; Allouis, C.; Monteverde, F. Heat Transfer in Ultra-High Temperature Advanced Ceramics Under High Enthalpy Arc-Jet Conditions. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 91, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, R.; Criscuolo, L.; Di Martino, G.D.; Mungiguerra, S. Aero-Thermo-Chemical Characterization of Ultra-High-Temperature Ceramics for Aerospace Applications. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2018, 38, 2937–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschall, J.; Pejakovic, D.; Fahrenholtz, W.G.; Hilmas, G.E.; Panerai, F.; Chazot, O. Temperature Jump Phenomenon During Plasmatron Testing of ZrB2-SiC Ultrahigh-Temperature Ceramics. J. Thermophys. Heat Transf. 2012, 26, 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, G.; Nisar, A.; Zhang, C.; Boesl, B.; Agarwal, A. Predicting Oxidation Damage of Ultra High-Temperature Carbide Ceramics in Extreme Environments Using Machine Learning. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 19974–19981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Hu, P.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, W. Effects of Oxygen Partial Pressure and Atomic Oxygen on the Microstructure of Oxide Scale of ZrB2–SiC Composites at 1500 °C. Corros. Sci. 2013, 73, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestroni, L.; Savino, R.; Cecere, A.; Mungiguerra, S. Failure Tolerant Functionally Graded Fiber-Reinforced UHTCs Exposed to Hypersonic Flows. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2024, 185, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, T.A.; Petry, M.D.; Cinibulk, M.K.; Mathur, T.; Gruber, M.R. Thermal and Oxidation Response of UHTC Leading Edge Samples Exposed to Simulated Hypersonic Flight Conditions. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, T.H.; Marschall, J. Material Property Requirements for Analysis and Design of UHTC Components in Hypersonic Applications. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 30, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Murtaza, Q.; Yuvraj, N. Development of ZrB2-SiC Plasma-Sprayed Ceramic Coating for Thermo-Chemical Protection in Hypersonic Vehicles. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 1401–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ge, Y.; Jin, X.; Lu, P.; Hou, C.; Wang, H.; Fan, X. Cyclic Thermal Shock Behaviors of ZrB2-SiC Laminated Ceramics Sintered with Different-Sized Particles for Each Sublayer. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2023, 59, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteverde, F.; Savino, R. ZrB2-SiC Sharp Leading Edges in High Enthalpy Supersonic Flows. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 95, 2282–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroz, V.I. Chemical Composition of the Atmosphere of Mars. Adv. Space Res. 1998, 22, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, V.I.; Carle, G.C.; Woeller, F.; Pollack, J.B.; Reynolds, R.T.; Craig, R.A. Pioneer Venus Gas Chromatography of the Lower Atmosphere of Venus. J. Geophys. Res. 1980, 85, 7891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplygin, A.; Simonenko, E.; Simonenko, N.; Kotov, M.; Yakimov, M.; Lukomskii, I.; Galkin, S.; Kolesnikov, A.; Vasil’evskii, S.; Shemyakin, A.; et al. Heat Transfer and Behavior of Ultra High Temperature Ceramic Materials Under Exposure to Supersonic Carbon Dioxide Plasma with Additional Laser Irradiation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 201, 109005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplygin, A.V.; Simonenko, E.P.; Kotov, M.A.; Sakharov, V.I.; Lukomskii, I.V.; Galkin, S.S.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Nagornov, I.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; et al. Short-Term Oxidation of HfB2-SiC Based UHTC in Supersonic Flow of Carbon Dioxide Plasma. Plasma 2024, 7, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakusta, M.; Watts, J.L.; Fahrenholtz, W.G.; Lipke, D.W. Effects of Processing and Microstructure on the Oxidation of ZrB2-SiC in CO2. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 117153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakusta, M.; Timme, N.M.; Rafi, A.H.; Watts, J.L.; Leu, M.C.; Hilmas, G.E.; Fahrenholtz, W.G.; Lipke, D.W. Oxidation of Additively Manufactured ZrB2–SiC in Air and in CO2 at 700–1000 °C. High Temp. Corros. Mater. 2024, 101, 827–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, B.; Wang, T.; Hu, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, R.; Yin, S.; Li, J.; Feng, Z.; et al. Reactive Sintering of Tungsten-Doped High Strength ZrB2–SiC Porous Ceramics Using Metastable Precursors. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 51, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Papynov, E.K.; Shichalin, O.O.; Belov, A.A.; Nagornov, I.A.; Simonenko, T.L.; Gorobtsov, P.Y.; Teplonogova, M.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Simonenko, N.P.; et al. Reactive Spark Plasma Sintering and Oxidation of ZrB2-SiC and ZrB2-HfB2-SiC Ceramic Materials. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1566–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-Q.; Kim, J.-S.; Seo, H.; Lee, S.-H. Effects of High-Energy Ball Milling and Reactive Spark Plasma Sintering on the Densification, Microstructure, and Mechanical Properties of Ultra-Fine and X-Ray Pure ZrB2-SiC Composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 116714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asl, M.S.; Nayebi, B.; Ahmadi, Z.; Zamharir, M.J.; Shokouhimehr, M. Effects of Carbon Additives on the Properties of ZrB2–Based Composites: A Review. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 7334–7348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lee, S.-H.; Feng, L. HfB2–SiC Composite Prepared by Reactive Spark Plasma Sintering. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 11009–11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, O.; Dibrov, V.; Kuryliuk, V.; Vishnyakov, V. Reactive and Non-Reactive Hot Pressing of ZrB2-SiC-C UHTCs: Structure, Mechanical and Thermal Properties. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2026, 46, 117839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoli, L.; Servadei, F.; Failla, S.; Mor, M.; Vinci, A.; Galizia, P.; Sciti, D. ZrB2–SiC Ceramics Toughened with Oriented Paper-Derived Graphite for a Sustainable Approach. J. Adv. Ceram. 2024, 13, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Kuang, C.; Liu, Z.; Yu, C.; Deng, C.; Ding, J. Effect of Nano-Graphite on Mechanical Properties and Oxidation Resistance of ZrB2–SiC–Graphite Electrode Ceramics. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wu, J.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Pan, J.; Tian, Y.; Wu, F. Study on Low Content Short Carbon Fibers to Enhance Mechanical Properties of ZrB2-SiC Composites with Improved Damage Tolerance. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lu, J.; Ni, D.; Chen, B.; Cai, F.; Zou, X.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Y.; Dong, S. Microstructure Evolution and Ablation Mechanisms of Csf/ZrB2-SiC Composites at Different Heat Fluxes under Air Plasma Flame. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 3514–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Ye, F.; Cheng, L. Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Ablation Resistance of ZrCw/ZrB2-SiC Composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1022, 179576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potanin, A.Y.; Zaitsev, A.A.; Korolev, V.V.; Soloshchenko, N.A.; Pogozhev, Y.S.; Rupasov, S.I.; Levashov, E.A. Effects of Synthesis and Hot-Pressing Conditions on ZrB2-ZrC-SiC Eutectic Ceramics: Structure Formation and Properties. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 32224–32239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Shahedi Asl, M.; Ghassemi Kakroudi, M.; Ahmadi, Z. Microstructure, Mechanical Properties and Oxidation Behavior of Reactive Hot-Pressed (Zr,Ti)B2-SiC-ZrC Composites. JOM 2025, 77, 1954–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestroni, L.; Melandri, C.; Gonzalez-Julian, J. Exploring Processing, Reactivity and Performance of Novel MAX Phase/Ultra-High Temperature Ceramic Composites: The Case Study of Ti3SiC2. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 41, 6064–6069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahedi Asl, M.; Nayebi, B.; Akhlaghi, M.; Ahmadi, Z.; Tayebifard, S.A.; Salahi, E.; Shokouhimehr, M.; Mohammadi, M. A Novel ZrB2-Based Composite Manufactured with Ti3AlC2 Additive. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 817–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozień, D.; Graboś, A.; Pasiut, K.; Ziąbka, M.; Chlubny, L.; Wójtowicz, M.; Banaś, W.; Grabowy, M.; Pędzich, Z. UHTC Ceramics Derived from B4C and MAX Phases by Reactive Sintering. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Nagornov, I.A.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Papynov, E.K.; Shichalin, O.O.; Belov, A.A.; Kolodeznikov, E.S.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Simonenko, N.P.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Effect of Ti2AlC on Sintering of Ultrahigh-Temperature Ceramics Based on HfB2–HfO2–SiC System. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 69, 2151–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Nagornov, I.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Sapronova, V.M.; Gorobtsov, P.Y.; Simonenko, N.P.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Synthesis of Ti2AlC in KBr Melt: Effect of Temperature and Component Ratio. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 69, 1744–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Chaplygin, A.V.; Simonenko, N.P.; Lukomskii, I.V.; Galkin, S.S.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Nagornov, I.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Simonenko, T.L.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; et al. Oxidation of HfB2-HfO2-SiC Ceramics Modified with Ti2AlC Under Subsonic Dissociated Airflow. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Simonenko, N.P.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; Chaplygin, A.V.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Nagornov, I.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Investigation of the Effect of Supersonic Flow of Dissociated Nitrogen on ZrB2–HfB2–SiC Ceramics Doped with 10 Vol.% Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2022, 15, 8507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonenko, E.P.; Simonenko, N.P.; Chaplygin, A.V.; Lukomskii, I.V.; Galkin, S.S.; Lysenkov, A.S.; Nagornov, I.A.; Mokrushin, A.S.; Kolesnikov, A.F.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Surface Degradation of Ultrahigh-Temperature Ceramics Based on HfB2–30vol%SiC in Subsonic Nitrogen Plasma Flow. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 130, 107139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplygin, A.V.; Vasil’evskii, S.A.; Galkin, S.S.; Kolesnikov, A.F. Thermal State of Uncooled Quartz Discharge Channel of Powerful High-Frequency Induction Plasmatron. Phys. Kinet. Gas Dyn. 2022, 23, 38–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeev, A. Overview of Characteristics and Experiments in IPM Plasmatrons. VKI, RTO AVT/VKI Spec. Course Measurement Techniques for High Enthalpy Plasma Flows. 1999. Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADP010736.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Norton, J.T.; Blumenthal, H.; Sindeband, S.J. Structure of Diborides of Titanium, Zirconium, Columbium, Tantalum and Vanadium. JOM 1949, 1, 749–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehr, S.; Mueller-Buschbaum, H.; Grin, Y.; von Schnering, H.G. H-TiO Oder TiB2?-Eine Korrektur. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1996, 622, 1035–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, B.; Glaser, F.W.; Moskowitz, D. Transition Metal Diborides. Acta Metall. 1954, 2, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braekken, H. Zur Kristallstruktur des Kubischen Karborunds. Z. Krist. 1930, 75, 572–573. [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, R.W.G. New Yorkrocksalt Structure. In Crystal Structures, 2nd ed.; Interscience Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1963; Volume 1, pp. 85–237. [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, R.W.G. Structure of Crystals, 2nd ed.; The Chemical Catalog Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, P. Über die Binären Systeme des Titans mit den Elementen Stickstoff, Kohlenstoff, Bor und Beryllium. Z. Anorg. Chem. 1949, 259, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, K.; Lengauer, W.; Rafaja, D.; Ettmayer, P. Lattice Parameters and Thermal Expansion of Ti(CxN1−x), Zr(CxN1−x), Hf(CxN1−x) and TiN1−x from 298 to 1473 K as Investigated by High-Temperature X-Ray Diffraction. J. Alloys Compd. 1994, 215, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterer, M.; Delaplane, R.; McGreevy, R. X-Ray Diffraction, Neutron Scattering and EXAFS Spectroscopy of Monoclinic Zirconia: Analysis by Rietveld Refinement and Reverse Monte Carlo Simulations. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2002, 35, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutterotti, L.; Scardi, P. Simultaneous Structure and Size–Strain Refinement by the Rietveld Method. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1990, 23, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechelany, M.; Brioude, A.; Cornu, D.; Ferro, G.; Miele, P. A Raman Spectroscopy Study of Individual SiC Nanowires. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 939–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus, C.; Cooper, D.; Sharp, J.; Rainforth, W.M. Microstructural Evolution and Wear Mechanism of Ti3AlC2–Ti2AlC Dual MAX Phase Composite Consolidated by Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS). Wear 2019, 438–439, 203013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, Z.; Meng, F.; Li, F. Raman Active Phonon Modes and Heat Capacities of Ti2AlC and Cr2AlC Ceramics: First-Principles and Experimental Investigations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 86, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, V.; Naguib, M.; Chaput, L.; Togo, A.; Hug, G.; Barsoum, M.W. First-Order Raman Scattering of the MAX Phases: Ti2AlN, Ti2AlC0.5N0.5, Ti2AlC, (Ti0.5V0.5)2AlC, V2AlC, Ti3AlC2, and Ti3GeC2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2012, 43, 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, G.G.; Stokes, M.J.; Liu, Y. Variation of Fundamental and Higher-Order Raman Spectra of ZrO2 Nanograins with Annealing Temperature. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 3173–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opeka, M.M.; Talmy, I.G.; Zaykoski, J.A. Oxidation-Based Materials Selection for 2000 °C + Hypersonic Aerosurfaces: Theoretical Considerations and Historical Experience. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 5887–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Takéuchi, Y. The Crystal Structure of Rutile as a Function of Temperature up to 1600 °C. Z. Krist.-Cryst. Mater. 1991, 194, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizawa, N.; Miyata, T.; Minato, I.; Marumo, F.; Iwai, S. A Structural Investigation of α-Al2O3 at 2170 K. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1980, 36, 228–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).