Abstract

The growing demand for sustainable pavement materials has increased interest in using recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) as a substitute for natural aggregates. However, the mechanical, durability, and environmental performance of roller-compacted concrete pavement (RCCP) incorporating very high RCA contents (≥75%) remains poorly understood, particularly when combined with hybrid steel fiber reinforcement. This knowledge gap limits the practical adoption of high-RCA RCCP in infrastructure applications. To address this gap, this study investigates the eco-efficiency of RCCP produced with 75% RCA and different steel fiber systems, including industrial (ISF), recycled (RSF), and hybrid (HSF) combinations. Mechanical performance was evaluated through compressive, tensile, and flexural testing, while freeze–thaw durability was assessed under extended cyclic exposure. Environmental impacts were quantified through a cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA), and a multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) was applied to integrate mechanical, durability, and environmental indicators. The findings show that although high-RCA mixtures exhibit reduced mechanical performance due to weaker interfacial bonding, HSF reinforcement effectively mitigates these drawbacks, enhancing toughness and improving freeze–thaw resistance. The LCA results indicate that replacing natural aggregates and industrial fibers with RCA and RSF substantially reduces environmental burdens. MCDA rankings further identify HSF-reinforced high-RCA mixtures as the most balanced and eco-efficient configurations. Overall, the study demonstrates that hybrid steel fibers enable the development of durable, low-carbon, and high-RCA RCCP, providing a viable pathway toward circular and sustainable pavement construction.

1. Introduction

The construction industry is one of the largest consumers of natural resources and contributors to global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, accounting for nearly one-third of global energy use and material extraction [1,2,3]. Within this sector, concrete infrastructure plays a dominant role in environmental degradation due to the intensive production of cement and the extensive exploitation of natural aggregates (NAs) [4,5,6]. The growing concern over climate change and resource scarcity has therefore motivated the development of eco-efficient construction materials that minimize embodied carbon while maintaining structural reliability [7,8].

Roller-compacted concrete pavement (RCCP) is increasingly recognized as a sustainable alternative to conventional pavement systems owing to its low cement content, reduced water demand, and rapid construction process involving high compaction energy [9,10]. It has been widely used in heavy-duty applications such as highways, industrial yards, and airfields because of its cost-effectiveness and durability. However, conventional RCCP still relies heavily on virgin aggregates and industrial steel fibers (ISFs), both of which are associated with significant energy consumption and CO2 emissions during extraction, processing, and transportation [11,12]. Enhancing the sustainability of RCCP requires innovative material substitutions that lower environmental impact while preserving or improving mechanical and durability performance [13].

Recycled concrete aggregate (RCA), derived from construction and demolition waste, and has emerged as a promising substitute for natural aggregates. Its use supports circular-economy principles by diverting waste from landfills, conserving natural resources, and reducing environmental burdens [14,15,16]. Nevertheless, incorporating RCA often leads to reduced mechanical strength, lower stiffness, and inferior durability compared with natural aggregates. These shortcomings are primarily attributed to the adhered mortar, higher porosity, and weaker interfacial transition zones (ITZ) within RCA particles [17,18,19]. Such deficiencies become especially critical when RCA replacement levels exceed 50%, limiting its application in high-performance pavement systems. Achieving durable concrete with high RCA content (≥75%) therefore remains a major challenge requiring targeted performance enhancement strategies.

Fiber reinforcement is widely recognized as an effective means to mitigate the mechanical limitations of RCA-based concretes. The addition of steel fibers enhances post-cracking behavior, flexural toughness, and energy absorption capacity [20,21,22]. Industrial steel fibers (ISFs), characterized by high tensile strength and uniform geometry, improve crack bridging and stiffness but impose high environmental costs due to the energy-intensive nature of virgin steel production [23]. In contrast, recycled steel fibers (RSFs), typically recovered from end-of-life tires, offer a low-carbon alternative that valorizes waste streams and reduces dependence on virgin materials [24,25,26]. However, RSFs exhibit irregular geometry and variable aspect ratios, which can hinder consistent dispersion and mechanical performance [27].

Recent studies suggest that hybrid steel fiber (HSF) systems, combinations of ISF and RSF, can generate synergistic effects that outperform single-fiber systems [28,29]. ISFs primarily enhance load-carrying capacity and stiffness, while RSFs improve ductility and multi-directional crack control [30]. This complementary action improves both strength and durability through multi-scale crack stabilization, where RSFs control micro-cracks and ISFs bridge macro-cracks. Despite these advantages, comprehensive research addressing the combined use of high RCA and HSF reinforcement in RCCP remains limited, particularly concerning freeze–thaw durability and life-cycle environmental performance [31,32,33]. Furthermore, the integration of mechanical, durability, and environmental metrics through systematic multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) has been seldom explored in this context [34,35,36].

In addition to RCA- and fiber-based research, numerous studies have explored waste-derived materials in pavement and rigid concrete systems. Examples include bentonite clay-blended concrete for durable rigid pavements [37], the use of C&D waste as recycled aggregates [38,39,40], fiber-reinforced RAC at elevated temperatures [41], PET-modified cement grouts modeled using multivariate and response-surface techniques [42,43], and mixtures incorporating recycled steel slag and LDPE for improved pavement performance [44]. Furthermore, advanced binder optimization strategies, such as nano-silica-modified geopolymers, have shown significant microstructural and mechanical enhancements [45]. Although these works demonstrate the wide potential of waste-derived materials, they seldom focus on RCCP containing very high RCA contents, nor do they integrate mechanical performance, freeze–thaw durability, and life-cycle environmental assessment within a unified framework.

Recent studies have investigated RCCP incorporating 25% RCA with hybrid steel fibers [46] and 50% RCA using the same experimental and environmental methodology [47]. These studies demonstrated that HSF can successfully compensate for the performance loss caused by moderate RCA levels while improving freeze–thaw durability and reducing environmental impacts. However, no study to date, has evaluated RCCP with very high RCA content (75%) using a combined mechanical–durability–LCA–MCDA framework, leaving a critical gap in understanding the limits, performance trade-offs, and eco-efficiency potential of high-recycled-content pavement materials.

Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the feasibility and eco-efficiency of RCCP containing 75% RCA reinforced with different steel fiber systems (ISF, RSF, and HSF). To achieve this, twenty mixtures with 0% and 75% RCA and fiber dosages of 0–0.9% were experimentally assessed for compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths and subjected to extended freeze–thaw cycling. A cradle-to-gate life cycle assessment (LCA) was performed to quantify environmental impacts, and an entropy-weighted MCDA (WSM and TOPSIS) was applied to identify the most sustainable mixture. The central hypothesis is that hybrid steel fibers will produce a synergistic enhancement—defined as simultaneous improvement in mechanical behavior, higher freeze–thaw strength retention, and reduced environmental impacts—thus enabling the development of durable, low-carbon RCCP with very high RCA content.

2. Materials

A total of twenty roller-compacted concrete pavement (RCCP) mixtures were prepared and grouped into two categories based on the replacement level of natural aggregate (NA) with recycled concrete aggregate (RCA): 0% and 75% by mass. Each group consisted of ten mixes, including a plain control (no fibers), ISF-only and RSF-only mixes at 0.3%, 0.6%, and 0.9% by volume fraction, and hybrid steel fiber (HSF) mixtures combining ISF and RSF equally. Mix codes followed the format N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0, where “N25” and “R75” denote 25% NA and 75% RCA, respectively, with fiber dosages indicated by the suffixes. This grouping structure was applied consistently in the mixture design table and the organization of results.

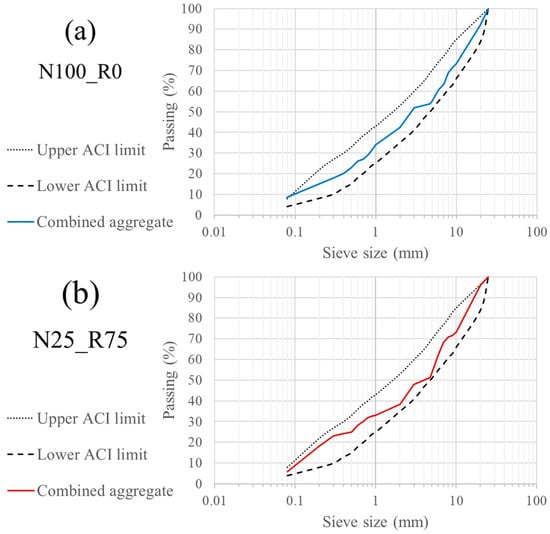

The coarse and fine aggregates were selected and characterized following ACI 211.3R [48] and ACI 325.10R [49] guidelines, with all physical and mechanical properties determined according to ASTM standards to ensure their suitability for RCCP production. The RCA used in this study was produced from previously tested structural-grade OPC concrete cylinders with an average compressive strength of approximately 40 MPa. The parent concrete was less than five years old, manufactured with CEM I cement and an estimated water–cement ratio of 0.45. Prior to use, the RCA source material underwent quality-control checks including visual inspection for contaminants (asphalt, wood, plastics, and gypsum), removal of loose mortar and fine dust, and verification that no deleterious substances were present. After crushing, the RCA was washed, sieved, and oven-dried to minimize variability. Moisture content was measured for each batch, and moisture corrections were applied during mix proportioning following ACI 211.3R guidelines. Although obtained from a clean and controlled source, it is acknowledged that RCA properties may vary depending on parent concrete age, composition, curing conditions, and contamination levels, which may influence performance in broader field applications. Natural coarse aggregate (crushed granite, CG; 4.76–22.50 mm) and natural fine aggregate (river sand, RS; 0–4.76 mm) were also used. The particle size distributions of the combined aggregates for the two RCA replacement groups, N100_R0 and N25_R75, are shown in Figure 1, with all gradation curves within the limits of ACI 211.3R, confirming well-graded aggregates suitable for high-density RCCP. The key physical properties, determined following ASTM C127 [50], C128 [51], C29 [52], C136 [53], and C117 [54], are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution curves of combined aggregates for two RCCP groups: (a) N100_R0 (100% natural aggregates); (b) N25_R75 (75% RCA replacement).

Table 1.

Physical properties of natural and recycled aggregates used in RCCP mixtures, determined in accordance with relevant ASTM standards.

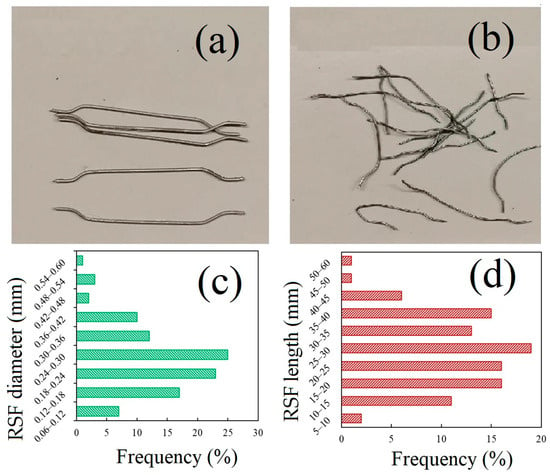

Two types of steel fibers were incorporated to improve the mechanical performance, durability, and sustainability of the RCCP mixtures: ISF and RSF. Their physical forms are illustrated in Figure 2. The ISFs were commercially manufactured hooked-end fibers, 33 mm in length, commonly used in structural concrete for their uniform geometry and reliable mechanical performance. The RSFs were recovered from post-consumer tires through mechanical shredding, promoting waste valorization and circular economy principles. Due to their irregular geometry and non-uniform dimensions, a representative sample of 3000 RSFs was analyzed to determine their diameter and length distributions, which are presented in Figure 2c,d. Because such variability can affect mix workability, fiber dispersion, and the repeatability of mechanical results, extended mixing procedures and visual dispersion checks were conducted to minimize fiber clustering and promote uniform distribution. The chosen fiber volume fractions of 0.3%, 0.6%, and 0.9% lie within the typical dosage range used in pavement-grade steel-fiber concretes (0.3–1.0%). These levels maintain acceptable workability while still delivering noticeable gains in strength, toughness, and post-cracking behavior [55,56]. The inclusion of RSFs reduces the environmental impact associated with virgin steel production and tire disposal. The physical and mechanical properties of both fiber types are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Steel fibers used in RCCP mixtures: (a) industrial steel fibers (ISF); (b) recycled steel fibers (RSF) recovered from post-consumer tires; (c) RSF diameter distribution; and (d) RSF length distribution.

Table 2.

Physical and mechanical properties of industrial (ISF) and recycled (RSF) steel fibers used in RCCP mixtures.

The binder used was OPC classified as CEM I 42.5R, conforming to EN 197-1 specifications. It exhibited compressive strengths of 20 MPa at 2 days and 42.5 MPa at 28 days. The cement (Cem), supplied by a local manufacturer, was stored in a temperature-controlled, low-humidity environment to prevent premature hydration. Its specific gravity was 3.18 g/cm3. Potable tap water (Wat), compliant with ASTM C1602, was used for all mixing and curing operations. A polycarboxylate-based superplasticizer (SP; Master Glenium SKY 617) was incorporated at dosages of 3.4–10.2 kg/m3 to ensure adequate workability, especially in mixtures with lower water content and higher fiber volume.

3. Methodology

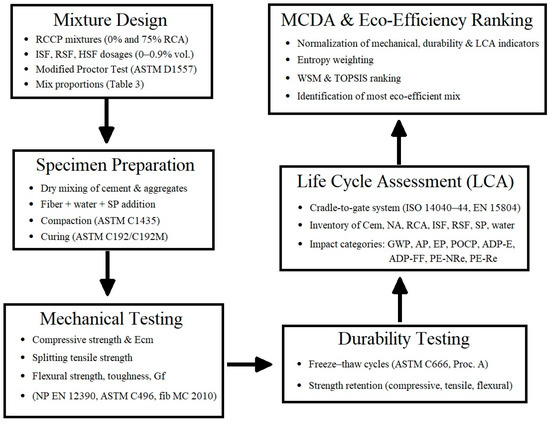

A total of twenty RCCP mixtures were designed in accordance with ACI 211.1-91 [57], comprising two groups of ten mixtures each, including one plain control mix (0% ISF and 0% RSF). The Modified Proctor Test (ASTM D1557 [58]) was used to determine the optimum moisture content (OMC) and corresponding maximum dry density (MDD). Water content was varied incrementally, and the OMC was defined as the moisture level corresponding to the MDD. Based on the OMC, the water-to-cement ratio (Wat/Cem) and material quantities per cubic meter were established, as shown in Table 3. The resulting Wat/Cem ratios fall within the typical range reported for RCCP (0.35–0.65) and were selected to ensure proper compaction, aggregate interlock, and sufficient paste lubrication, enabling both field-representative workability and target strength development. The selected mixture-design parameters follow established RCCP procedures to ensure that laboratory conditions reflect typical pavement construction practices and allow direct comparison with existing literature. To enhance clarity, a methodological flow diagram has been added (Figure 3), providing a step-by-step overview of the procedures used in mixture preparation, mechanical and durability testing, LCA, and MCDA.

Table 3.

Mix design and material quantities of RCCP mixtures per cubic meter.

Figure 3.

Overview of the methodological framework, summarizing the sequential steps: mixture design, specimen preparation, mechanical and durability testing, LCA, and MCDA [58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

Dry materials (cement and aggregates) were first mixed for one minute, followed by the gradual addition of fibers, water, and superplasticizer (SP) to ensure uniform dispersion and prevent clumping. Mixing continued for an additional five minutes to achieve homogeneity. Fresh RCCP was cast into cylindrical molds (150 × 300 mm) for compressive and splitting tensile tests and prismatic molds (150 × 150 × 600 mm) for flexural and durability tests.

Compaction was performed in three layers using an electric vibrating hammer(Utest, Ankara, Turkey) in accordance with ASTM C1435 [59], with each layer compacted for up to 20 s or until a mortar ring appeared, indicating sufficient consolidation. Specimens were demolded after 24 h and cured in water at 23 ± 2 °C for 28 days, following ASTM C192/C192M [60]. These preparation and compaction parameters were selected because they replicate field-relevant RCCP compaction energy and ensure consistent mechanical performance across specimens.

The mechanical performance of the RCCP specimens was evaluated through uniaxial compressive strength, splitting tensile strength, and three-point notched beam-bending tests (3PNBBT). All tests were performed in accordance with relevant standards to ensure accuracy and repeatability.

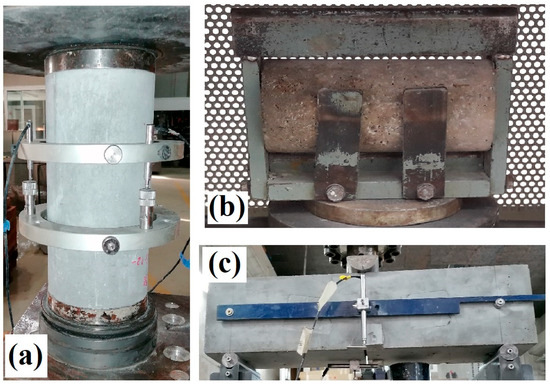

The uniaxial compressive strength (), secant modulus of elasticity () were determined after 28 days of curing following NP EN 12390-3:2011 [67] and NP EN 12390-13:2014 [68], respectively. Tests were conducted on cylindrical specimens (150 × 300 mm) using a servo-controlled universal testing machine (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) with a maximum capacity of 2000 kN. Axial displacement was recorded by an integrated displacement transducer, which served as the control variable during loading. The compressive strength was calculated based on the peak load, while the modulus of elasticity was obtained from the slope of the stress–strain curve in its linear region. The compressive toughness (), defined as the area under the stress-displacement curve up to 0.33 of the peak stress, quantified the energy absorption capacity of the RCCP mixtures [69]. The loading rates, instrumentation, and strain-measurement configuration were selected based on NP EN testing requirements to ensure accurate capture of stiffness and post-peak behavior. The experimental setup and instrumentation are shown in Figure 4a, illustrating the test configuration and monitoring system.

Figure 4.

Experimental setups and monitoring systems for mechanical testing of RCCP specimens: (a) uniaxial compressive strength and modulus of elasticity tests; (b) splitting tensile strength test; (c) three-point notched beam-bending test (3PNBBT) for flexural behavior evaluation.

The splitting tensile strength () was determined according to ASTM C496/C496M [62] using cylindrical specimens (150 × 300 mm). Each specimen was positioned horizontally between two hardened steel bearing strips, and a diametral compressive load was applied until failure. Transverse deformation was measured perpendicular to the loading axis to capture the material response under indirect tension. ASTM C496 was selected because it is the standard method for determining tensile capacity in pavement concretes and provides high repeatability for fiber-reinforced materials. The splitting tensile strength was calculated from the peak load () obtained from the load-deformation curve, corresponding to the elastic limit of the material. The experimental setup and loading configuration are shown in Figure 4b.

The flexural behavior of the RCCP mixtures was evaluated using 3PNBBT in accordance with the fib Model Code 2010. Prismatic specimens (150 × 150 × 600 mm) with a 500 mm span and a 25 mm mid-span notch (<5 mm wide) were tested under monotonic loading using a 250 kN servo-hydraulic actuator. The initial flexural tensile strength () was determined at a crack mouth opening displacement (CMOD) of 0.05 mm, representing the material’s cracking resistance. Residual flexural strengths (–) were obtained at CMODs of 0.5, 1.5, 2.5, and 3.5 mm, respectively. The flexural toughness () was calculated as the area under the load-CMOD curve up to 3.5 mm, representing the material’s energy absorption capacity. The CMOD-controlled setup was adopted because it enables precise evaluation of crack propagation, post-cracking response, and fiber-bridging mechanisms—critical parameters for RCCP. The fracture energy () was derived from the same curve, normalized by the specimen’s fracture surface area. The experimental setup and instrumentation are shown in Figure 4c.

The freeze–thaw resistance of the RCCP mixtures was assessed according to ASTM C666, Procedure A, which replicates aggressive environmental conditions through repeated freezing and thawing in water. Before testing, all specimens were immersed in water for 24 h to achieve full saturation and uniform moisture distribution. The freeze–thaw cycles (FTCs) were carried out in a programmable climatic chamber(Serve Real, Wuxi, China) for 100, 200, and 300 cycles. Each cycle consisted of cooling the specimens to −18 °C, followed by thawing in water at +4 °C, with one complete cycle lasting approximately 4–5 h.

To evaluate durability degradation, compressive strength (NP EN 12390-3:2011 [67]), splitting tensile strength (ASTM C496 [62]), and flexural tensile strength (fib Model Code 2010) were determined after each exposure stage. The strength retention ratio was obtained by comparing the post-exposure strength to that of companion specimens cured under standard laboratory conditions (ASTM C192/C192M [60]). The selected cycle counts (100, 200, 300) correspond to moderate and severe freeze–thaw exposure levels widely used in pavement durability research, ensuring comparability with prior studies. The present durability evaluation focused on strength-retention metrics; complementary indicators such as mass loss, dynamic modulus, and surface scaling were not measured and will be included in future studies to provide a broader understanding of freeze–thaw mechanisms.

All mechanical and durability tests were performed on four replicate specimens, and the results were expressed as mean values. The coefficient of variation (CoV) was used to quantify data variability, while Dixon’s Q test and boxplot analysis were applied to identify and remove statistical outliers, ensuring the reliability of the results. In all figures, error bars and values in parentheses indicate the corresponding CoV (%) for each dataset.

A cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was carried out to quantify the environmental impacts associated with twenty RCC pavement (RCCP) mixtures containing various proportions of RCA and steel fibers (ISF, RSF, and HSF types). The analysis followed the methodological framework established in ISO 14040-44 (2006) [70] and EN 15804:2012+A1 [66], consistent with circular economy principles that promote material efficiency and waste reduction in concrete production.

Two RCA replacement levels (0% and 75%) and four fiber dosages (0%, 0.3%, 0.6%, and 0.9% by volume) were considered, as summarized in Table 3. The system boundary encompassed all processes from raw material extraction and processing to concrete mixing, representing a cradle-to-gate perspective. Stages beyond production, such as transportation and placement, were excluded since their contributions were assumed comparable across all mixtures. A functional unit of 1 m3 of concrete was adopted to enable a fair comparison between mixture alternatives.

The life cycle inventory (LCI) included the consumption of raw materials and energy, together with emissions and solid waste generated during production. Environmental datasets for the superplasticizer (SP) were obtained from the International Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) database [71], whereas cement and background data were sourced from the European Life Cycle Database (ELCD) [72]. Data for RCA originated from on-site surveys, supplier information, and previously published studies [4,73,74]. Information related to ISF and RSF was collected from local producers, with RSF environmental burdens adapted from Kurda et al. [75]. The datasets for natural aggregates and water were compiled from relevant literature [75,76,77], ensuring alignment with regional and technological conditions.

The LCA was intentionally conducted under a cradle-to-gate system boundary to focus exclusively on the upstream production impacts of materials, which represent the main differentiating factors among the mixtures. Construction, transportation, and use-phase processes were excluded because all RCCP mixtures would undergo identical batching, compaction, hauling distance, equipment use, and service-life behavior under a given project scenario. Including these identical downstream processes would add complexity and uncertainty without influencing the comparative ranking of mixtures, which was the primary objective of this study. Transportation impacts (distance, fuel type, and transport mode) were also excluded because all aggregates and fibers were sourced from the same suppliers, using the same transportation routes and vehicle types. As a result, transportation-related emissions would be constant for all mixtures and would not affect the comparative assessment. The selection of ELCD, EPD, and literature-based datasets was made to ensure transparency and traceability. ELCD and EPD sources are internationally recognized and peer-reviewed databases widely used in construction material LCA studies. All datasets were verified against documented system boundaries, allocation procedures, and technological representativeness to ensure consistency with EN 15804 and CML methodological requirements.

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) was performed according to the categories defined in EN 15804:2012+A1 [66], covering eight key indicators: global warming potential (GWP), ozone depletion potential (ODP), acidification potential (AP), eutrophication potential (EP), photochemical ozone creation potential (POCP), and abiotic depletion potential (ADP) for both elements and fossil resources, together with primary energy demand, divided into renewable (PE-Re) and non-renewable (PE-NRe) sources. The CML baseline method was employed to calculate GWP, ODP, AP, EP, POCP, and ADP, whereas the Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) approach was used for energy-related indicators.

For each concrete mixture, the impact of individual constituents was computed by multiplying their material quantities (Table 3) by the corresponding impact factors (Table 4 and Table 5). The total environmental burdens were then normalized per cubic meter of concrete. The uncertainty associated with LCA data sources, emission coefficients, and recycled-material burdens was assessed through a sensitivity analysis. Cement-related impact factors were varied by ±15%, while RCA and fiber-related GWP values were adjusted by ±20% to reflect potential fluctuations in recycling efficiency, energy demand, and regional processing variations. The resulting sensitivity ranges confirmed that the relative ranking of mixtures remained stable, demonstrating the robustness of the LCA conclusions.

Table 4.

Baseline environmental impact factors for the production of 1 kg of each raw material, calculated using the CML method within a cradle-to-gate system boundary.

Table 5.

Mix design parameters and material quantities of RCCP mixtures normalized to 1 m3 of concrete.

A multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) was carried out to evaluate the eco-efficiency of twenty RCCP mixtures by integrating their mechanical, durability, and environmental performances. The objective was to identify mixtures that best balance sustainability and functionality, consistent with circular economy principles. To holistically assess mixture performance, the MCDA incorporated key mechanical indicators (compressive strength, modulus of elasticity, splitting tensile strength, flexural strength, fracture energy, and compressive and flexural toughness) representing the structural capacity of RCCP. Durability indicators included strength retention after 300 freeze–thaw cycles (CSR_300FTCs for compressive strength, TSR_300FTCs for tensile strength, and FSR_300FTCs for flexural strength). Environmental impacts were evaluated using eight representative categories (GWP, AP, EP, POCP, ADP-elements, ADP-fossil, PE-NRe, and PE-Re) consistent with EN 15804 [66] and CML methods. These indicators were selected because they directly influence pavement performance, sustainability, and long-term serviceability.

All criteria were normalized following procedures in [78,79]. For mechanical and durability metrics (“higher-is-better”), the following normalization was applied:

where x′ij is the normalized value for specimen i and criterion j, xij is the original value, and min(xj), max(xj) are the minimum and maximum values for criterion j, respectively.

For environmental indicators (“lower-is-better”), the inverted form was used:

where x′ij, xij, min(xj), and max(xj) are as defined above.

These normalization formulas ensured that all parameters were dimensionless and comparable across categories with different scales, enabling consistent integration of mechanical, durability, and environmental performance. Criterion weights were obtained using the entropy weighting method [78,79], which assigns greater importance to parameters with higher variability. These indicators were selected because they directly influence pavement safety, serviceability, and sustainability.

Entropy weighting was chosen because it is objective and data-driven, avoiding subjectivity in assigning weights. Parameters with higher discriminatory power—such as splitting tensile strength and GWP—received larger weights due to their broader variability across mixtures. The entropy weighting procedure followed four steps:

(1) Probability matrix:

(2) Entropy calculation:

(3) Divergence (information utility):

(4) Weight normalization:

All entropy-based weights were documented for transparency, ensuring reproducibility of the MCDA results. Two ranking techniques, the Weighted Sum Method (WSM) and the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), were employed to ensure consistency. To evaluate the robustness of the MCDA results, a secondary sensitivity analysis was conducted using equal weights (1/m for m criteria). The mixture rankings obtained using equal weights were consistent with the entropy-weighted results, confirming that the final eco-efficiency ranking was not overly dependent on the weighting scheme. This demonstrated the stability and reliability of the MCDA outcomes and ensured a transparent, data-driven identification of the most sustainable RCCP mixtures.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Mechanical Performance

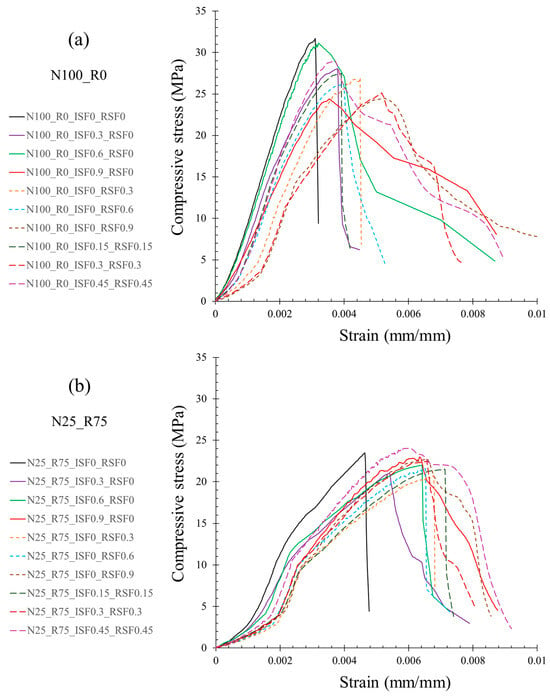

The 28-day stress–strain responses of RCCP mixtures are shown in Figure 5, and the corresponding compressive strength (fcm), secant modulus of elasticity (Ecm), and compressive toughness (Toug_Comp) with their CoV values are presented in Table 6. Both the RCA content and fiber type had a marked influence on the compressive behavior of the mixtures. In the N100_R0 group (0% RCA), compressive strength ranged from 24.4 MPa (N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0) to 31.7 MPa (plain RCCP), defining the baseline for natural aggregate mixtures. When 75% of the natural aggregates were replaced with RCA (N25_R75 group), the compressive strength dropped to 23.5 MPa (N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0), representing an average reduction of about 26%. This reduction primarily stems from the higher porosity and weaker interfacial transition zone (ITZ) of RCA, which diminish the load transfer capacity between paste and aggregate [43]. The incorporation of steel fibers significantly mitigated this strength loss. At 75% RCA, the hybrid steel fiber (HSF) mixture (N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45) achieved 24 MPa, exceeding the performance of single-fiber mixes (≈21–22 MPa). However, excessive fiber addition (e.g., 0.9% ISF) slightly decreased compressive strength (24.4 MPa for N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0), which may be attributed to fiber agglomeration and non-uniform dispersion within the matrix.

Figure 5.

Compressive stress–strain relationships of RCCP mixtures at 28 days: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

Table 6.

Compressive strength, elastic modulus, and toughness of cylindrical RCCP specimens after 28 days.

The elastic modulus (Ecm) followed a comparable trend, decreasing from 34,431 MPa (N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0) to 28,594 MPa (N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0) due to the inherently lower stiffness of RCA [43]. Nonetheless, fiber inclusion partially recovered stiffness, particularly in HSF mixtures (28,965 MPa for N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45), owing to improved stress redistribution and enhanced confinement of microcracks [80,81,82]. As observed in Figure 5, the N100_R0 series exhibited sharper stress peaks and steeper slopes, whereas the N25_R75 series showed more gradual curves, confirming reduced stiffness with higher RCA content. The fiber-reinforced mixtures displayed smoother post-peak transitions, reflecting enhanced ductility and energy absorption under compressive loading.

The compressive toughness (Toug_Comp) showed a substantial increase with fiber incorporation. It rose from 15.8 N/mm (plain RCCP) to 40.5 N/mm (N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45) and 37.6 N/mm (N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45), corresponding to improvements exceeding 120% relative to the control mixture. The enhanced toughness results from the complementary effect of short RSFs and long ISFs, which collectively promote multiscale crack bridging, RSFs effectively control microcrack propagation, while ISFs bridge macrocracks, improving post-peak load-carrying capacity [83,84,85,86]. It should be noted that some mechanical and durability results exhibited noticeable deviations among replicate specimens, as reflected in the reported CoV (%) values. These deviations are related to RCA heterogeneity and fiber-distribution effects and were taken into account when interpreting all performance trends. Overall, although the inclusion of RCA reduces both strength and stiffness due to its weaker physical characteristics, the use of hybrid steel fibers compensates for these drawbacks by significantly enhancing ductility and energy dissipation. The combination of 75% RCA and 0.9% hybrid fibers (ISF0.45_RSF0.45) achieved a balanced performance, demonstrating that high-RCA hybrid fiber RCCP can meet mechanical requirements for pavement applications while aligning with circular economy and sustainability goals. These mechanical properties are consistent with strength and stiffness ranges recommended in pavement regulatory documents such as AASHTO Guide for Pavement Design and EN 13108, confirming that the evaluated RCCP mixtures satisfy typical performance requirements for pavement base and surface layers.

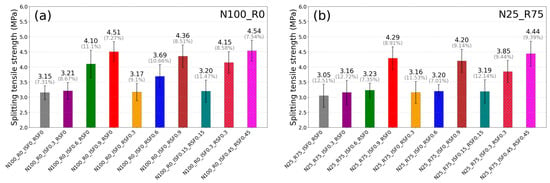

The splitting tensile strength () results of RCCP mixtures after 28 days are shown in Figure 6, highlighting the influence of RCA incorporation and fiber configuration. Overall, the inclusion of steel fibers significantly enhanced the tensile response, with hybrid steel fiber (HSF) mixtures demonstrating the highest performance gains.

Figure 6.

Splitting tensile strength (MPa) and corresponding coefficient of variation (CoV %) of fiber-reinforced RCCP mixtures at 28 days: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

The plain reference mixtures exhibited the lowest tensile capacity, attaining 3.15 MPa and 3.05 MPa for the N100_R0 and N25_R75 groups, respectively. The slight reduction observed in RCA-based mixes is attributed to the weaker interfacial transition zones (ITZs) and higher porosity of recycled aggregates, which adversely affect the bond between paste and aggregate [87]. The addition of ISF notably increased tensile strength through improved crack-bridging efficiency. For example, N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 and N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 reached 4.51 MPa and 4.29 MPa, corresponding to improvements of approximately 43% and 41% compared with their respective controls. Conversely, RSF produced moderate gains due to their irregular geometry and smaller dimensions; N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9 achieved 4.20 MPa, about 38% higher than the control. The most pronounced enhancement was recorded in HSF mixtures, which consistently outperformed single-fiber systems. The mixtures N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 and N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 exhibited peak strengths of 4.54 MPa and 4.44 MPa, representing 44% and 46% increases over the plain counterparts. This superior performance is attributed to the synergistic interaction between long ISFs, effective in bridging macrocracks, and short RSFs, which control microcrack initiation and propagation, resulting in enhanced multi-scale crack resistance and uniform fiber distribution [28,88].

The coefficient of variation (CoV) for most fiber-reinforced mixtures remained below 12%, confirming consistent and reliable performance. Even with a 75% RCA replacement, hybridization maintained mechanical stability, as observed in N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 (4.44 MPa, CoV = 9.4%). These findings align well with previous studies [21,85,89,90], which emphasize the role of fiber hybridization in improving the tensile response, post-cracking resistance, and overall toughness of concrete containing recycled aggregates. Thus, employing HSF-reinforced RCCP represents a viable and sustainable approach to offset RCA-induced weaknesses while ensuring structural integrity in eco-efficient pavement applications.

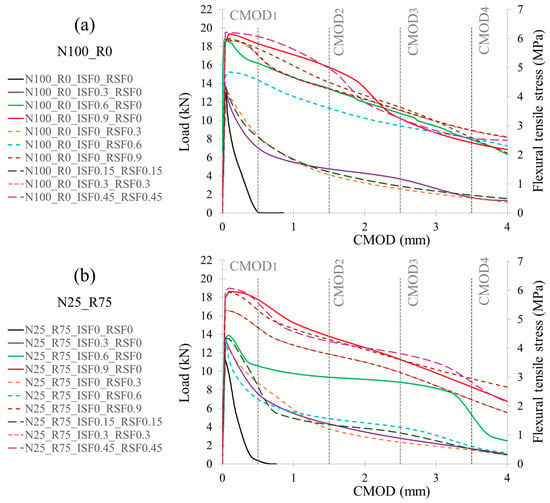

The flexural performance of the RCCP mixtures at 28 days, assessed using the 3PNBBT, exhibited a clear dependency on both RCA incorporation and fiber reinforcement strategy. The corresponding parameters, initial flexural tensile strength () and residual flexural strengths (–), are shown in Figure 7 and summarized in Table 7. The initial flexural strength () ranged from 3.65 MPa in N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0 to 6.25 MPa in N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45. In plain RCCP, increasing the RCA content from 0% to 75% caused an approximate 12% reduction in (4.14 MPa for N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0 vs. 3.65 MPa for N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0), confirming the negative influence of the higher porosity and weaker interfacial transition zones (ITZs) of recycled aggregates [18]. The introduction of steel fibers, particularly in hybrid steel fiber (HSF) configurations, significantly enhanced the post-cracking load-bearing capacity. HSF mixtures at moderate to high fiber dosages (up to 0.9%) consistently outperformed single-fiber systems. For instance, N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 achieved = 5.97 MPa, with residual strengths of = 5.56 MPa and = 2.82 MPa. In comparison, the ISF-only mixture N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 showed = 5.71 MPa, = 5.68 MPa, and = 2.66 MPa, while the RSF-only mix N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9 reached = 5.94 MPa, = 5.31 MPa, and = 2.94 MPa. The CMOD curves (Figure 7) further support these findings. HSF mixtures showed a more gradual stress decay and extended post-peak plateau, indicating enhanced ductility and sustained load-carrying capacity after cracking. In contrast, single-fiber mixtures exhibited steeper stress reductions, reflecting limited energy dissipation and less stable post-peak behavior.

Figure 7.

Load and flexural stress versus CMOD curves for RCCPs at 28 days: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

Table 7.

Flexural tensile strength results of RCCP specimens obtained from three-point notched beam-bending tests (3PNBBT) at 28 days.

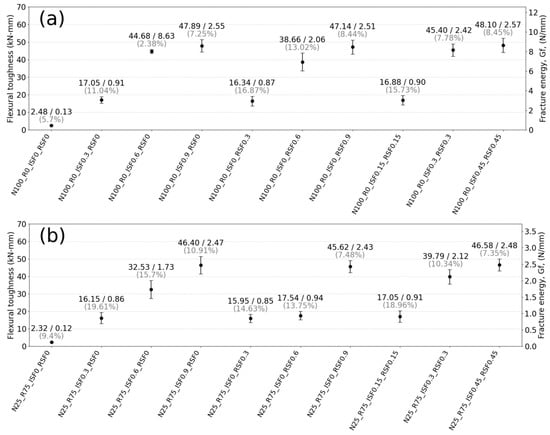

Figure 8 further illustrates flexural toughness () and fracture energy () up to a CMOD of 3.5 mm. The plain RCCPs exhibited brittle behavior with rapid stress drops and minimal post-peak ductility, yielding toughness values between 2.32 and 2.48 kN.mm and fracture energy () below 0.14 N/mm, regardless of RCA content. The inclusion of ISF-only fibers (particularly at 0.9% volume) markedly improved energy absorption, with toughness values exceeding 46 kN·mm and reaching 2.5 N/mm. However, RSF-only mixtures exhibited lower post-cracking performance, confirming that short fibers alone are less effective in macrocrack bridging [91,92,93]. The HSF-reinforced RCCPs displayed the most superior flexural response, achieving the highest toughness and fracture energy values. Notably, N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 and N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 exhibited peak toughness values of 48.1 kN·mm and 46.6 kN·mm, with corresponding values of 2.57 N/mm and 2.48 N/mm, respectively. These results demonstrate a synergistic effect between long, hooked-end ISFs (effective in macrocrack bridging) and short RSFs (efficient in microcrack control), resulting in improved stress redistribution, crack resistance, and energy absorption across the entire CMOD range [91,93,94]. This apparent trend—where RSF mixtures show lower toughness than ISF mixtures, and hybrid systems outperform both—is consistent with established fiber-bridging mechanisms reported in the literature. Due to their irregular and short geometry, RSFs primarily control microcracks but offer limited macrocrack bridging, while ISFs provide stronger post-peak load transfer yet may cause localized crack planes at higher contents. Hybridization combines these mechanisms, producing a multiscale crack-bridging network that delays crack localization and enhances post-cracking ductility, explaining the distinct toughness hierarchy observed in Figure 8 [29,91,92,93,94].

Figure 8.

Flexural toughness and fracture energy up to a CMOD of 3.5 mm: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

Overall, hybrid steel fiber reinforcement significantly improved the flexural strength, residual capacity, and ductility of RCCP mixtures, even with high RCA incorporation. Although RCA-rich mixtures inherently exhibited reduced due to their weaker matrix structure, the inclusion of steel fibers, particularly in hybrid form, effectively compensated for these losses. Consequently, HSF-reinforced RCCPs with up to 75% RCA demonstrated comparable performance to conventional mixtures with natural aggregates, supporting the transition toward sustainable and circular concrete pavement solutions.

The reduced strength and stiffness of the 75% RCA mixtures arise from the porous adhered mortar and weaker ITZ of recycled aggregates. The hybrid steel fibers partially compensate for these weaknesses through a multiscale crack-bridging mechanism, where long ISFs stabilize macrocracks and short RSFs control microcrack initiation. This combined action improves stress redistribution, delays crack localization, and densifies the matrix, reducing pore connectivity and limiting moisture movement. However, no microstructural characterization (e.g., SEM, XRD, porosity, or ITZ analysis) was conducted in this study; therefore, interpretations of fiber–matrix interaction remain inferential and should be validated through future microstructural examination.

4.2. Durability

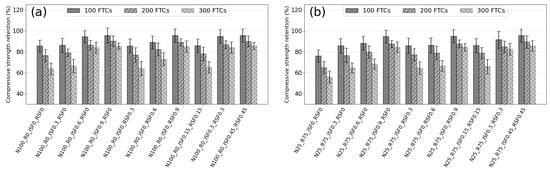

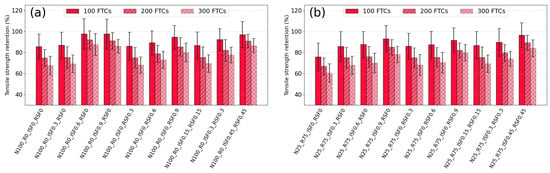

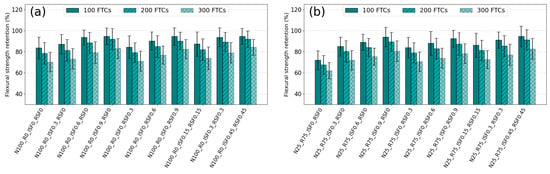

The resistance of RCCP mixtures to freeze–thaw deterioration was assessed by monitoring compressive strength retention after 100, 200, and 300 FTCs. The results, illustrated in Figure 9 and detailed in Table A1 (Appendix A), indicate that both aggregate type and fiber configuration played a decisive role in the mixtures’ long-term durability. The unreinforced RCCPs (ISF0_RSF0) exhibited the highest rate of degradation. In the N100_R0 mixture, strength retention decreased from 85.4% after 100 FTCs to only 63.8% after 300 FTCs. When natural aggregates were replaced with 75% RCA, the deterioration became even more severe, with the N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0 mix retaining just 56% of its original compressive strength after 300 FTCs. This accelerated decay is primarily associated with the porous and microcracked structure of recycled aggregates, which allows greater moisture ingress and induces internal expansion and matrix disruption during freeze–thaw cycling [95,96]. Incorporating steel fibers notably mitigated this damage, particularly when hybrid steel fiber (HSF) systems were used. The mixture N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 maintained 95.4%, 89.4%, and 85.6% of its strength after 100, 200, and 300 FTCs, respectively, representing nearly a 53% improvement in durability compared with the plain RCA mix at 300 FTCs. Likewise, N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 retained 95.5%, 90.2%, and 85.2%, confirming the strong role of fibers in mitigating thermal fatigue and cracking. The hybrid fiber-reinforced concretes consistently achieved the best results, outperforming both ISF- and RSF-only systems. For instance, N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 preserved more than 84% strength after 200 FTCs and 82.5% after 300 FTCs. The superior performance of HSF mixtures can be attributed to their multi-scale reinforcement mechanism, where long ISFs act as macro-crack bridges and short RSFs control microcrack propagation. This dual action enhances the fiber interconnectivity and network density, thereby reducing permeability, limiting moisture migration, and minimizing internal stresses caused by freezing and thawing. Such mechanisms effectively delay crack initiation and maintain the structural integrity of the cementitious matrix under cyclic frost exposure [97,98].

Figure 9.

Compressive strength retention of RCCP mixtures after 100, 200, and 300 freeze–thaw cycles: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

In summary, the results clearly demonstrate that hybrid fiber reinforcement significantly enhances freeze–thaw durability, even in concretes incorporating high levels of RCA. RCCP mixtures with up to 75% RCA, reinforced with 0.9% HSF, displayed strength retention comparable to or even exceeding that of ISF-only mixtures with 100% natural aggregates. This confirms the effectiveness of hybrid reinforcement in producing durable, sustainable, and low-carbon RCCP materials suitable for long-term pavement applications in cold climates.

The influence of freeze–thaw exposure on the tensile strength retention of RCCP mixtures is presented in Figure 10 and detailed in Table A2. The results demonstrate that both recycled aggregate incorporation and fiber architecture strongly govern the rate of degradation under cyclic freezing and thawing. A pronounced reduction in tensile performance was observed in unreinforced mixtures, where progressive cracking and matrix disruption occurred with repeated cycles. In the control mix N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0, tensile strength retention declined from 85.6% after 100 FTCs to 67.6% after 300 FTCs. When 75% of natural aggregate was replaced with RCA, as in N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0, retention fell from 75.7% to 60.5%, indicating that the more porous RCA microstructure and weaker paste, aggregate interfaces accelerate internal damage under cyclic thermal stress [99,100]. By contrast, steel fiber inclusion greatly enhanced the resistance to freeze–thaw deterioration. At higher fiber dosages, the improvement was particularly evident: for instance, N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 maintained >92% of its initial tensile strength after 100 FTCs and still retained >78% after 300 FTCs. The most durable behavior was observed in HSF configurations, which synergistically combine long ISFs and short RSFs. The mixture N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 achieved 96.5%, 89.3%, and 84.0% retention after 100, 200, and 300 FTCs, respectively, representing a 39% gain over the plain mix and an 8% improvement over the ISF-only system at 300 cycles. The enhanced stability of HSF mixtures arises from the cooperative mechanisms of multi-scale crack control. Long ISFs bridge macrocracks and maintain load transfer, while short RSFs stabilize microcracks and densify the matrix. This hybrid reinforcement refines the pore structure, reduces permeability, and restricts internal water migration, thus mitigating frost-induced stresses and delaying the onset of structural damage [91,101,102]. Consequently, microstructural fatigue is reduced, and tensile capacity is preserved even under prolonged cyclic exposure.

Figure 10.

Tensile strength retention of RCCP mixtures after 100, 200, and 300 FTCs: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

The overall trend mirrors the compressive strength retention behavior discussed earlier: hybrid fiber systems provide the most effective resistance to freeze–thaw deterioration. Notably, RCCP mixtures with up to 75% RCA, reinforced with 0.9% HSF, maintained nearly equivalent tensile strength retention to those made entirely with natural aggregates. These findings confirm that hybrid fiber reinforcement not only offsets the durability drawbacks of RCA but also enables the production of robust, sustainable, and frost-resistant RCCPs, aligning with circular economy objectives for infrastructure materials.

The results of the flexural strength retention tests for RCCP mixtures exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs are presented in Figure 11 and detailed in Table A3. The data clearly indicate that both RCA incorporation and fiber configuration play decisive roles in the material’s ability to sustain flexural performance under cyclic freezing and thawing. For plain RCCP mixtures (ISF0_RSF0), a continuous decline in flexural strength was observed with increasing exposure cycles. After 300 FTCs, the N100_R0 mixture retained only 70.24% of its original strength, while N25_R75 dropped further to 62.02%, representing an 11.7% reduction linked to the use of RCA. This deterioration is primarily caused by the higher porosity, weaker ITZs, and enhanced microcracking susceptibility of recycled aggregates, which accelerate internal frost damage, a trend consistent with the findings of Lu et al. [103]. The decline was evident even at earlier stages, where retention decreased from 83.58% to 78.55% in N100_R0 and 71.98% to 67.64% in N25_R75 between 100 and 200 FTCs, underscoring the influence of RCA on freeze–thaw vulnerability.

Figure 11.

Flexural strength retention of RCCP mixtures after 100, 200, and 300 FTCs: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

Incorporating steel fibers substantially mitigated these losses. Among all mixtures, those reinforced with HSF demonstrated the most stable behavior. At a total fiber dosage of 0.9% (ISF0.45_RSF0.45), the HSF mixtures retained up to 84.3% (N100_R0) and 82.8% (N25_R75) of their initial flexural strength after 300 FTCs. By comparison, ISF-only systems achieved 83.1% and 80.63%, while RSF-only counterparts recorded 82.4% and 78.29%, respectively. The slightly inferior performance of RSF mixtures can be attributed to the shorter and more irregular geometry of recycled fibers, which limits their capacity for macro-crack bridging, as previously observed by Bao et al. [104]. The superior endurance of HSF mixtures arises from the complementary functions of the two fiber types. Long hooked-end ISFs control macrocracks and sustain load transfer, whereas short RSFs enhance matrix integrity and delay the onset of microcracking. This multi-scale crack-bridging mechanism improves internal stress distribution, reduces strain localization, and minimizes frost-induced fracture propagation, consistent with the mechanisms described by Wang et al. [105].

Even with high RCA replacement levels (75%), HSF-reinforced RCCPs preserved a large portion of their flexural capacity, whereas plain specimens exhibited sharp degradation. The integration of hybrid fibers therefore provides a robust and durable reinforcement strategy, improving both mechanical reliability and resistance to cyclic environmental degradation. These outcomes confirm that HSF incorporation is a viable approach for producing eco-efficient, freeze–thaw-resistant RCCP mixtures, aligning with circular-economy goals for sustainable pavement infrastructure.

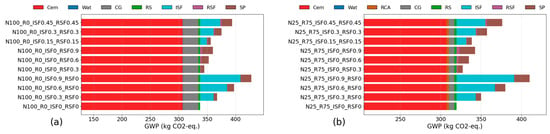

4.3. Environmental Impacts and Eco-Efficiency Ranking

A comprehensive cradle-to-gate Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was carried out for twenty RCCP mixtures to quantify their environmental performance per 1 m3 of concrete, following the CML baseline and Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) methodologies. The analysis covered nine major impact categories: GWP, ODP, AP, EP, POCP, ADP-E and ADP-FF, and both renewable and non-renewable primary energy consumption (PE-Re and PE-NRe). An overview of the variation across these categories is presented in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16, Figure 17, Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20, with detailed datasets provided in Table A4 and Table A5 in the Appendix A.

Among all indicators, global warming potential (GWP) was the most influential due to its direct link to CO2 emissions and its relevance to the environmental footprint of construction materials [106]. As illustrated in Figure 12, the incorporation of RCA consistently reduced GWP. In plain RCCP mixtures, the total carbon footprint declined from 337.4 kg CO2-eq for the full natural aggregate mix (N100_R0) to 319.8 kg CO2-eq for the 75% RCA mix (N25_R75). This reduction stems from the lower embodied emissions associated with RCA production compared to the extraction and crushing of virgin aggregates, aligning with the results of earlier LCA studies [107,108]. Fiber type and content further influenced the GWP outcomes. Mixtures reinforced exclusively with ISF exhibited the highest carbon intensity, mainly due to the high energy consumption and emission profile of virgin steel manufacturing. For instance, N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 registered approximately 410 kg CO2-eq, whereas its counterpart reinforced solely with RSF, N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9, recorded a much lower 342.5 kg CO2-eq, corresponding to a ~16.5% reduction. This highlights the environmental advantage of utilizing recovered tire-derived fibers, which not only divert waste from landfills but also avoid the intensive smelting and processing stages inherent in virgin steel production [109].

In HSF systems containing both ISF and RSF, GWP rose modestly with increasing fiber volume. For example, at 75% RCA replacement, raising the total fiber content from 0.3% to 0.9% increased emissions from 338.7 to 376.3 kg CO2-eq, an ~11% increment. However, this remained well below the levels recorded for ISF-only mixes. This balance suggests that hybrid fiber dosages can achieve optimized eco-efficiency, delivering structural resilience with a reduced environmental burden. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that integrating recycled aggregates and fibers can substantially reduce the carbon footprint of RCCP mixtures without compromising performance, reinforcing the potential of such hybrid systems as viable components of low-carbon, circular pavement technologies.

Figure 12.

Global warming potential (GWP) of 1 m3 RCCP mixtures across different fiber configurations: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

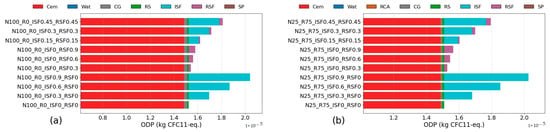

Ozone depletion potential (ODP) values showed minimal variation across all RCCP mixtures (Figure 13), decreasing slightly from 1.52 × 10−5 to 1.51 × 10−5 kg CFC-11 eq as RCA content increased to 75%. This indicates that ozone depletion is largely insensitive to aggregate replacement and is instead governed by materials with higher chemical processing footprints, such as cement and admixtures. Among fiber-reinforced mixtures, RSF-based systems recorded the lowest ODP values (e.g., 1.56 × 10−5 for N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9), whereas ISF-only mixtures showed higher values (e.g., 2.03 × 10−5 for N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0), attributable to the use of refrigerants and solvents in virgin steel manufacturing. Hybrid fiber (HSF) mixes exhibited intermediate results (e.g., 1.8 × 10−5 for N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45). Overall, the narrow ODP range across all mixtures confirms that ozone depletion is a secondary environmental concern in RCCP production but remains a relevant comparative indicator for sustainable mix optimization.

Figure 13.

Ozone depletion potential (ODP) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

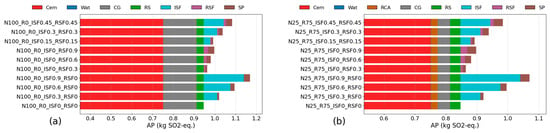

Acidification potential (AP), expressed in kg SO2-equivalents, is primarily associated with emissions of sulfur and nitrogen oxides (SOx and NOx) released during the extraction of raw materials and cement manufacturing processes. As illustrated in Figure 14, the use of RCA led to a measurable reduction in acidification impacts. The AP value declined from 0.95 kg SO2-eq for the natural aggregate mixture (N100_R0) to 0.85 kg SO2-eq for the 75% RCA mix (N25_R75, plain), demonstrating the environmental advantage of partially replacing virgin aggregates. Mixtures incorporating ISF recorded comparatively higher acidification levels, reaching up to 1.07 kg SO2-eq, a result of the energy-intensive production and combustion-related emissions associated with virgin steel manufacturing. Conversely, the inclusion of RSF or HSF contributed to noticeable impact reductions. For instance, N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 exhibited an AP of 0.98 kg SO2-eq, highlighting the benefits of integrating recycled materials into the fiber matrix. These findings align with the conclusions of previous studies [110,111], which reported that using recycled steel can effectively mitigate acidification impacts through lower fuel use and emission intensities. Overall, the results underscore that the combined use of RCA and recycled fibers offers a practical strategy to decrease the acidification footprint of RCCP mixtures.

Figure 14.

Acidification potential (AP) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

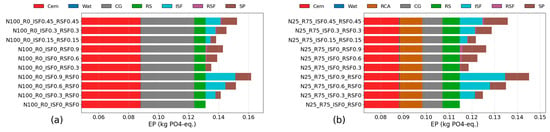

Eutrophication potential (EP), expressed in kg PO43−-equivalents, quantifies the potential for nutrient enrichment, mainly from nitrate and phosphate emissions, that can lead to algal blooms and ecosystem imbalance. As shown in Figure 15, EP was primarily affected by cement production and energy consumption during material processing. Similarly to acidification trends, increasing the RCA replacement ratio resulted in lower EP values. For the plain mixtures, EP decreased from 0.13 kg PO43−-eq at 0% RCA (N100_R0) to 0.11 kg PO43−-eq at 75% RCA (N25_R75), highlighting the environmental benefit of substituting natural aggregates with recycled ones. Fiber inclusion further influenced EP outcomes. ISF-only mixtures exhibited the highest values, reaching up to 0.15 kg PO43−-eq, reflecting the nutrient-related emissions associated with the energy-intensive steel manufacturing process. In contrast, mixtures reinforced with recycled or hybrid steel fibers showed lower EP values, typically ranging between 0.13 and 0.14 kg PO43−-eq. Moreover, reducing total fiber dosage was found to further minimize eutrophication impacts, particularly in hybrid systems, where EP declined from 0.14 to 0.12 kg PO43−-eq as fiber content decreased from 0.9% to 0.3%.

Figure 15.

Eutrophication potential (EP) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

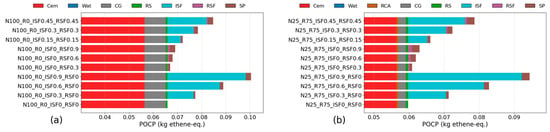

Photochemical ozone creation potential (POCP), expressed in kg ethene-equivalents, measures the tendency of emissions to contribute to ground-level ozone (smog) formation. As illustrated in Figure 16, POCP values decreased with higher RCA incorporation, mirroring the trends observed for other impact categories. In the plain RCCP mixtures, POCP dropped from 0.066 kg ethene-eq for N100_R0 to 0.059 kg ethene-eq for N25_R75, reflecting the environmental benefit of substituting virgin aggregates with recycled ones. When analyzing fiber-reinforced systems, clear differences emerged among fiber types. RSF mixtures consistently achieved the lowest POCP values, whereas ISF mixtures produced the highest. At a total fiber volume of 0.9%, POCP reached 0.063 kg ethene-eq for RSF, compared with 0.094 kg for ISF, and 0.079 kg for HSF systems within the N25_R75 group. The lower POCP in RSF mixtures can be attributed to the absence of volatile emissions typically associated with primary steel manufacturing, as RSF recovery involves mechanical recycling rather than energy-intensive melting or refining processes [112,113].

Figure 16.

Photochemical ozone creation potential (POCP) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

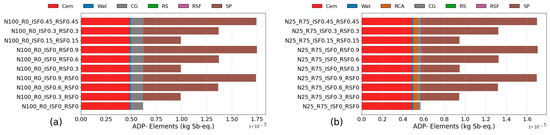

Abiotic depletion potential for elements (ADP-elements) quantifies the use of non-renewable mineral resources, which in this study was mainly affected by the aggregate type and fiber composition. As shown in Figure 17, ADP-elements varied notably among mixtures, with higher values generally associated with fiber-reinforced systems. Across both RCA replacement levels, mixtures containing RSF recorded the highest ADP-elements values, reaching approximately 1.70 × 10−5 kg Sb-eq at a 0.9% fiber dosage. Although RSF originates from waste tire recycling, its elevated ADP-elements score can be explained by the additional energy demand and resource inputs required during fiber recovery, cleaning, and reprocessing, as reported by Biswas et al. [114]. The influence of RCA on this category was more pronounced in plain mixtures, where increasing RCA content from 0% to 75% led to a substantial decrease in ADP-elements, reaching 0.57 × 10−5 kg Sb-eq. This reflects the reduced dependence on virgin aggregates and the associated mineral extraction. In contrast, the impact reduction was less evident in RSF and HSF mixtures, as the contribution from steel processing partially offset the benefits of RCA substitution. HSF systems displayed intermediate ADP-elements values, providing a balanced environmental profile by combining moderate resource use with strong mechanical and durability performance.

Figure 17.

Abiotic depletion potential for elements (ADP-elements) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

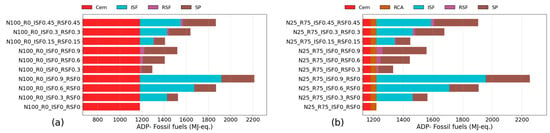

Abiotic depletion potential for fossil fuels (ADP-fossil fuels), expressed in megajoules (MJ), reflects the consumption of non-renewable energy resources and exhibited trends similar to GWP. As shown in Figure 18, ADP-fossil fuel values increased slightly with RCA incorporation, rising from 1180.5 MJ for the N100_R0 plain mixture to 1219.8 MJ for the N25_R75 counterpart. This modest increase is likely linked to the additional energy demands associated with processing recycled aggregates. Fiber inclusion had a much stronger influence on fossil fuel depletion. Mixtures reinforced exclusively with ISF recorded the highest ADP-fossil fuels, reaching 2253.4 MJ at a 0.9% dosage, primarily due to the energy-intensive steel manufacturing process. Conversely, RSF mixtures exhibited substantially lower values, remaining below 1558.2 MJ, thereby confirming the energy-saving benefits of recycled steel utilization. HSF systems at 0.9% fiber volume achieved intermediate results, such as 1905.8 MJ for N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45, balancing performance and energy efficiency.

Figure 18.

Abiotic depletion potential for fossil fuels (ADP-fossil fuels) associated with the production of 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

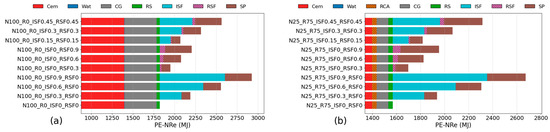

Non-renewable primary energy consumption (PE-NRe) quantifies the use of finite energy resources that cannot be naturally replenished within a human lifetime (EN 15804). As illustrated in Figure 19, cement production dominated PE-NRe in all mixtures, contributing about 76.6% of the total energy demand for the plain mix (N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0), followed by crushed granite (CG) at roughly 21.2%. Introducing industrial steel fibers (ISF) further increased energy use, accounting for nearly 27% of total PE-NRe in N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0, reflecting the high energy intensity of steel manufacturing, consistent with GWP and ADP-fossil fuel patterns. Conversely, replacing 50% of ISF with RSF and 75% of CG with RCA in the N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 mix achieved a ~21% overall energy reduction, confirming the efficiency of sustainable material substitutions.

Figure 19.

Non-renewable primary energy consumption (PE-NRe) for 1 m3 of RCCP mixture: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

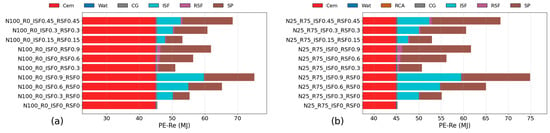

Renewable primary energy consumption (PE-Re) quantifies the use of energy derived from naturally replenishable, non-fossil sources (EN 15804). As illustrated in Figure 20, cement production dominated renewable energy use, contributing approximately 60% of the total PE-Re for all mixtures. In the N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 mix, superplasticizer (SP) and ISF production accounted for an additional ~20% and ~19%, respectively, making them the next most energy-demanding components. Substituting ISF with RSF drastically reduced renewable energy demand, lowering ISF’s contribution from ~19% to ~2%. Furthermore, the inclusion of RCA and natural fibers (NFs) showed negligible influence on PE-Re values. The N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9 mixture demonstrated up to an 18% reduction in renewable energy consumption compared to N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0, confirming that using RSF and RCA enhances energy efficiency and supports the production of more sustainable RCCP mixtures.

Figure 20.

Renewable primary energy consumption (PE-Re) for producing 1 m3 of RCCP mixtures: (a) N100_R0 series; (b) N25_R75 series.

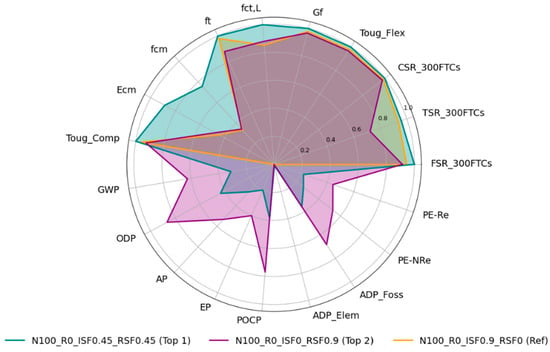

A comprehensive multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) combining WSM and TOPSIS was applied to integrate mechanical, durability, and environmental indicators. The results (Table 8, Figure 21) show that the hybrid fiber mix N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 achieved the highest eco-efficiency scores (WSM = 0.67; TOPSIS = 0.64), indicating the best balance between strength, freeze–thaw durability, and environmental performance. This mix maintained strong tensile and flexural strengths ( = 4.54 MPa; = 6.25 MPa), over 84% retention after 300 FTCs, and moderate impacts (GWP = 393.8 kg CO2-eq; ADP-fossil = 1866.5 MJ), outperforming the control mixture by ~31%. The second-ranked N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.9 mix achieved slightly lower mechanical results but reduced emissions (GWP = 360.1 kg CO2-eq) and strong toughness ( = 2.5 N/mm; = 47.1 kN·mm). Conversely, the reference mix N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 scored lowest (WSM = 0.51; TOPSIS = 0.50) due to its high environmental burden despite high strength (GWP = 427.6 kg CO2-eq; PE-NRe = 2925.7 MJ).

Table 8.

Eco-efficiency ranking of RCCP mixtures based on WSM and TOPSIS results.

Figure 21.

Normalized comparison of mechanical, durability (after 300 FTCs), and environmental indicators for the two most eco-efficient RCCP mixtures versus the reference mix (N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0).

Overall, hybrid fiber reinforcement, particularly 0.45% ISF + 0.45% RSF, proved the most effective strategy for optimizing eco-efficiency in RCCP. While hybridization significantly enhanced sustainability in 100% NA mixtures, it only partially offset the mechanical drawbacks of highly recycled (≥75% RCA) systems.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the combined effects of industrial (ISF), recycled (RSF), and hybrid (HSF) steel fibers with high recycled concrete aggregate (RCA) contents on the mechanical performance, freeze–thaw durability, and environmental efficiency of roller-compacted concrete pavement (RCCP). Twenty mixtures were produced using 0% and 75% RCA and fiber dosages up to 0.9%, integrating mechanical testing, life cycle assessment (LCA), and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA).

High-RCA mixtures showed reductions of approximately 26% in compressive strength and 17% in elastic modulus compared with natural-aggregate mixtures, primarily due to the weaker and more porous interfacial transition zone of RCA. However, incorporating 0.9% hybrid fibers significantly compensated for these losses. In natural-aggregate mixtures, HSF reinforcement increased compressive toughness from 15.8 N/mm to 40.5 N/mm and enhanced splitting tensile strength from 3.15 MPa to above 4.5 MPa. In mixtures containing 75% RCA, HSF reinforcement raised splitting tensile strength to 4.44 MPa compared with 3.05 MPa in the plain mix.

Flexural behavior also improved substantially with hybrid reinforcement. The HSF mixture (ISF0.45_RSF0.45) achieved higher residual strengths ( ≈ 5.56 MPa and ≈ 2.82 MPa) and markedly increased fracture energy (≈2.5 N/mm) compared with plain mixtures (<0.14 N/mm). Freeze–thaw durability similarly benefited from fiber hybridization: after 300 cycles, compressive strength retention increased from 56% in the plain 75% RCA mixture to 85.6% in the corresponding HSF mixture. Tensile strength retention increased from 60.5% to 84.0%, confirming the improved stability of hybrid fiber RCCP under cyclic frost exposure.

The LCA demonstrated that substituting natural aggregates with RCA and incorporating recycled steel fibers reduced global warming potential and non-renewable energy consumption by up to 20%. MCDA identified the ISF0.45_RSF0.45 mixture as the most eco-efficient configuration, achieving approximately 31% higher overall performance compared with the control mixture.

Although the results are promising, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study considered only one high RCA level (75%) and was conducted under controlled laboratory conditions. Intermediate RCA levels (e.g., 25% and 50%), field compaction variability, real construction conditions, and long-term exposure environments were not examined. In addition, the chemical composition of RCA and recycled steel fibers and the potential release of heavy metals or other hazardous compounds were not evaluated. Thus, the long-term environmental safety of RCA-based RCCP requires further investigation.

While RCA can reduce material costs and RSF can lower fiber expenditure compared with industrial fibers, real-world savings depend on local availability, transportation distance, and processing requirements. Field applicability may also be affected by workability challenges, higher water absorption of RCA, the need for moisture corrections during batching, and the risk of fiber balling at high dosages. Scaling laboratory findings to full-scale pavement construction requires attention to compaction uniformity, pavement thickness tolerances, and variability in RCA sources, which may impact performance under traffic loading and seasonal environmental conditions.

Future research directions should include field-scale trials of high-RCA RCCP, long-term monitoring under traffic and climate conditions, microstructural analysis, shrinkage and fatigue testing, and comprehensive environmental hazard assessments, including leaching and contaminant mobility. These efforts are essential to validate the long-term mechanical, durability, environmental, and safety performance of RCA- and RSF-based RCCP systems.

Overall, the findings confirm that hybrid steel fiber reinforcement offers a robust and effective strategy for producing durable, eco-efficient, and low-carbon RCCP mixtures incorporating high RCA contents, supporting sustainable and circular-economy pavement development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; methodology, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; software, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; validation, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; formal analysis, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; investigation, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; data curation, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; writing—review and editing, O.H.; visualization, A.A.S.M., S.I.M., B.A.O., S.A.A., A.V. and O.H.; supervision, O.H. and S.I.M.; project administration, O.H. and S.I.M.; funding acquisition, S.I.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Zarqa University.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by Zarqa University. Additional appreciation is extended to the University of Petra, INTI International University, Qassim University, King Saud University, Shinawatra University, and the University of Minho for their valuable collaboration and institutional support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The abbreviations appearing in this manuscript are defined below:

| ADP-Elem | Abiotic depletion of elements |

| ADP-fossil | Abiotic depletion of fossil fuels |

| AP | Acidification potential |

| Cem | Cement |

| CG | Crushed granite (coarse aggregate) |

| CMOD | Crack mouth opening displacement |

| CSR_300FTCs | Compressive strength retention after 300 freeze–thaw cycles |

| Ecm | Secant modulus of elasticity |

| EP | Eutrophication |

| fcm | Uniaxial compressive strength |

| fct,L | Initial flexural tensile strength |

| FRC | Fiber-reinforced concrete |

| FSR_300FTCs | Flexural strength retention after 300 freeze–thaw cycles |

| ft | Splitting tensile strength |

| FTCs | Freeze–thaw cycles |

| Gf | Fracture energy |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HSF | Hybrid ISF/RSF |

| ISF | Industrial steel fiber |

| ITZ | Interfacial transition zone |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCI | Life cycle inventory |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MDD | Maximum dry density |

| NA | Natural aggregate |

| ODP | Ozone depletion |

| OMC | Optimum moisture content |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| PE_NRe | Non-renewable energy |

| PE_Re | Renewable energy |

| POCP | Photochemical ozone creation potential |

| RCA | Recycled concrete aggregate |

| RCCP | Roller-compacted concrete pavement |

| RS | River sand (fine aggregate) |

| RSF | Recycled steel fiber |

| SP | Superplasticizer |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| Toug_Comp | Compressive toughness |

| Toug_Flex | Flexural toughness |

| TSR_300FTCs | Tensile strength retention after 300 freeze–thaw cycles |

| Wat | Water |

| WSM | Weighted Sum Method |

| 3PNBBT | Three-point notched beam-bending tests |

Appendix A

The following Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5 are the supplementary data to this article.

Table A1.

Compressive strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

Table A1.

Compressive strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

| Specimens | Compressive Strength Retention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 FTCs | 200 FTCs | 300 FTCs | ||||

| Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0 | 85.43 | 6.65 | 76.38 | 7.49 | 63.83 | 8.46 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 86.2 | 7.89 | 79.05 | 4.58 | 66.41 | 9.61 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 94.43 | 6.17 | 86.38 | 5.26 | 83.83 | 6.33 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 95.53 | 7.51 | 90.18 | 5.48 | 85.2 | 3.54 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 85.62 | 7.68 | 77.0 | 9.09 | 64.16 | 10.54 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 88.97 | 6.72 | 82.3 | 7.38 | 73.05 | 8.27 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.9 | 95.41 | 6.65 | 89.0 | 3.93 | 84.95 | 6.51 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.15_RSF0.15 | 85.83 | 7.6 | 77.98 | 8.12 | 65.21 | 8.44 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 | 94.68 | 7.04 | 86.95 | 4.31 | 84.05 | 6.16 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 | 95.59 | 6.57 | 89.86 | 5.66 | 85.6 | 4.06 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0 | 76.05 | 7.67 | 64.91 | 9.09 | 56.0 | 10.49 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 85.69 | 8.02 | 76.55 | 8.92 | 64.56 | 7.25 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 88.17 | 7.51 | 79.69 | 7.64 | 68.25 | 7.18 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 94.63 | 6.42 | 87.53 | 3.81 | 84.42 | 5.96 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 85.67 | 8.37 | 77.18 | 7.62 | 64.38 | 9.32 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 86.13 | 8.21 | 78.78 | 8.16 | 66.58 | 7.72 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9 | 94.92 | 6.42 | 87.64 | 4.26 | 84.27 | 4.34 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.15_RSF0.15 | 86.0 | 7.93 | 78.71 | 6.82 | 65.92 | 10.32 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 | 91.45 | 8.87 | 84.71 | 6.42 | 82.5 | 6.82 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 | 95.44 | 6.43 | 89.42 | 6.64 | 85.56 | 5.84 |

Table A2.

Tensile strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

Table A2.

Tensile strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

| Specimens | Tensile Strength Retention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 FTCs | 200 FTCs | 300 FTCs | ||||

| Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0 | 85.62 | 14.11 | 74.92 | 10.76 | 67.62 | 13.2 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 86.8 | 14.33 | 75.3 | 13.57 | 69.32 | 12.11 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 97.62 | 14.85 | 91.92 | 9.4 | 87.62 | 11.89 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 97.7 | 14.47 | 91.1 | 8.71 | 85.91 | 7.53 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 85.91 | 15.46 | 75.02 | 12.97 | 68.0 | 11.45 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 89.16 | 12.95 | 78.82 | 10.41 | 73.03 | 11.18 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.9 | 94.52 | 11.75 | 85.37 | 10.12 | 80.12 | 11 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.15_RSF0.15 | 86.78 | 14.63 | 75.34 | 13.2 | 69.5 | 12.08 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 | 92.14 | 11.39 | 82.0 | 12.38 | 77.61 | 9.67 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 | 96.93 | 12.82 | 90.82 | 7.24 | 86.5 | 7.63 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0 | 75.72 | 17.52 | 66.82 | 12.1 | 60.46 | 14.36 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 85.78 | 16.49 | 75.0 | 13.15 | 67.92 | 12.59 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 87.51 | 14.22 | 75.97 | 12.98 | 69.86 | 13.29 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 92.97 | 13.6 | 84.97 | 8.64 | 78.05 | 9.91 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 86.0 | 14.39 | 75.06 | 12.3 | 68.15 | 14.46 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 87.35 | 14.63 | 75.39 | 12.13 | 70.31 | 13.95 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.9 | 91.65 | 12.71 | 82.11 | 8.53 | 79.75 | 9.72 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.15_RSF0.15 | 86.72 | 15.11 | 75.28 | 13.17 | 69.28 | 11.9 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 | 89.75 | 14.79 | 79.63 | 10.05 | 73.98 | 9.6 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 | 96.5 | 12.27 | 89.3 | 7.99 | 84.02 | 9.63 |

Table A3.

Flexural strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

Table A3.

Flexural strength retention of RCCP specimens exposed to 100, 200, and 300 FTCs.

| Specimens | Flexural Strength Retention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 FTCs | 200 FTCs | 300 FTCs | ||||

| Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | Retention (%) | CoV (%) | |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0 | 83.58 | 12.22 | 78.55 | 13.12 | 70.24 | 13.03 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 87.22 | 10.64 | 81.39 | 12.43 | 73.3 | 13.24 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 93.58 | 7.51 | 88.56 | 11.02 | 79.24 | 12.96 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 94.64 | 8.21 | 91.99 | 10.95 | 83.1 | 11.43 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 84.33 | 12.66 | 79.29 | 11.8 | 71.1 | 13.4 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 90.19 | 9.62 | 84.97 | 12.17 | 76.87 | 11.19 |

| N100_R0_ISF0_RSF0.9 | 94.56 | 8.71 | 90.23 | 9.13 | 82.4 | 10.97 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.15_RSF0.15 | 87.36 | 13.17 | 82.1 | 12.4 | 73.91 | 14.41 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.3_RSF0.3 | 93.67 | 9.55 | 89.19 | 10.21 | 79.1 | 12.19 |

| N100_R0_ISF0.45_RSF0.45 | 94.5 | 7.89 | 92.11 | 8.31 | 84.31 | 8.97 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0 | 71.98 | 12.42 | 67.64 | 13.2 | 62.02 | 12.41 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.3_RSF0 | 85.0 | 10.51 | 80.33 | 12.58 | 71.93 | 12.67 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.6_RSF0 | 88.94 | 8.64 | 84.11 | 10.19 | 75.45 | 10.54 |

| N25_R75_ISF0.9_RSF0 | 93.9 | 9.78 | 89.44 | 9.98 | 80.63 | 12.01 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.3 | 83.96 | 11.65 | 78.96 | 12.11 | 70.62 | 13.02 |

| N25_R75_ISF0_RSF0.6 | 87.96 | 12.93 | 83.0 | 11.75 | 74.0 | 12.62 |