Abstract

Radiation shielding in medical settings has traditionally relied on fixed structural models, with thicknesses and material composition determined by their shielding effect against direct X-rays. However, clinical practice increasingly demands lightweight and biocompatible shielding tools that can be locally applied to specific anatomical regions. Such tools should allow rapid installation and removal, skin protection, and disposable as well as continuous shielding. As a potential solution, this study aimed to improve the effectiveness of a cream-type material that directly coats the skin with shielding agents. A modeling pack was fabricated using bismuth oxide, an eco-friendly shielding material; zinc oxide, commonly utilized in cosmetics for ultraviolet protection; and alginate, which enhances skin adhesion by evaporating moisture. The effects of varying bismuth oxide and zinc oxide ratios on porosity and shielding performance were evaluated to establish assessment criteria for future commercialization. The experimental results demonstrated that higher proportions of bismuth oxide enhanced the shielding effect, while a linear change in shielding rate was observed at a thickness of 1.0 mm. Although pore structure variations were minimal, optimizing inter-particle arrangement may further improve skin adhesion. These findings suggest that cream-type radiation-shielding materials are highly promising for medical applications.

1. Introduction

Radiological examinations in medical institutions typically utilize ionizing radiation. With advances in medical imaging and analysis technologies, the increased frequency and duration of fluoroscopic and interventional procedures involving ionizing radiation have raised concerns about occupational radiation exposure among healthcare workers [1]. Therefore, shielding tools that protect medical personnel during radiation-based imaging are essential. Beyond ensuring the justified use of radiation, it is equally important to establish safe and eco-friendly protective systems for the human body that proactively mitigate potential risks [2].

Radiation-protective shielding tools are categorized and employed according to the type of radiation used (X-rays and gamma rays), corresponding energy ranges, and specific activity domains where they can reduce both direct and indirect exposure and thus prevent harm [3]. Among these, functional protective clothing is the most accessible shielding tool for healthcare workers and other personnel [4]. Traditionally, lead has been the primary material used for such protective clothing; however, due to the recognized risks associated with lead-based shielding tools, interest in eco-friendly shielding materials has increased [5]. To fabricate shielding devices using eco-friendly materials, it is essential that their thickness and weight do not restrict the movements of medical workers or impose spatial limitations. Therefore, shielding tools for healthcare providers must exhibit flexibility, biocompatibility, and other features that do not interfere with medical practice [6,7].

During fluoroscopic and interventional procedures, clinicians predominantly use their hands, leaving the fingers and dorsal areas particularly exposed to direct X-rays or scattered radiation, including secondary charged particles [8,9]. Existing protective measures for these exposed regions include protective gloves and barriers containing shielding materials; however, all such approaches often hinder dexterity and visibility, making complete shielding practically impossible [10,11].

The key requirements of radiation-shielding devices involve balancing three factors: shielding performance, thickness, and weight. In general, increasing thickness improves shielding performance but reduces flexibility and increases weight, thereby restricting the mobility of healthcare workers and serving as a major obstacle to image formation during procedures [12].

This limitation is one of the main reasons conventional shielding tools fail to meet the practical needs of medical personnel. Current cream-type materials must account for slipperiness when in contact with surgical gloves, the stability required to maintain a uniform thickness, and sustained adhesion and retention; therefore, new design models and processes that reduce internal voids in the material are required for further development [13,14,15]. Reducing internal voids enlarges the interaction area between the material density and the incident energy, thereby improving the shielding performance. Medical radiation shielding requires new shielding tools that can be locally applied to specific anatomical regions, with adjustable lightweight thickness, biocompatibility, and ease of application and removal. Such tools should maintain skin adherence, provide reproducible and continuous shielding effects, and allow disposable use [16,17]. The shielding agents must be uniformly dispersed to achieve shielding efficacy against diagnostic X-rays, even with a thin layer [18].

The proposed shielding material is intended to be environmentally friendly. The relationship between the shielding performance of the cream-type material and the porosity formed among the particles in the fluid medium was analyzed to evaluate practical effectiveness. Therefore, bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and zinc oxide (ZnO) were selected as lead-free, eco-friendly shielding agents [19]. This represents a novel shielding approach, in which the materials were selected based on their shielding performance and safety, as well as user accessibility and cost-effectiveness compared with existing products. As these materials are already used as environmentally friendly shielding agents and as UV-blocking components in cosmetic formulations, they are expected to be more effective than conventional products.

In particular, Bi2O3, which can achieve shielding performance comparable to that of shielding devices, is widely used as an eco-friendly shielding material [20]. It has economic feasibility comparable to lead and, with an atomic number of 83 and a density of 8.9 g/cm3, it provides effective radiation attenuation, making it suitable for incorporation into composite materials [21]. ZnO is a cosmetic ingredient regarded as safe for skin applications and is widely used as a component of ultraviolet (UV)-blocking agents [22]. Owing to its low skin irritation and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, it is an appropriate material for topical use [23]. Furthermore, it can help reduce skin irritation caused by chemical interactions, making it advantageous for use as a shielding cream or coating agent. With a density of approximately 5.61 g/cm3, ZnO, when mixed with Bi2O3 as a composite material, is expected to provide radiation attenuation benefits through multiple scattering and porosity reduction [24]. Sodium alginate was used as the base matrix to form the gel structure of the modeling pack [25].

The objective of this study was to propose a new material model that addresses the limitations of conventional radiation-protective creams, particularly the inadequate shielding performance and poor usability. This approach aims to enhance user comfort and accessibility in clinical practice. Further research on advanced medical radiation shielding materials that can provide effective direct and indirect protection for frequently exposed areas, such as the dorsal side of the hand, will be necessary in the future.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this experiment, the shielding device was designed as a modeling pack rather than a protective cream to ensure uniform thickness and strong adhesion to the skin, while minimizing surface stickiness and slipperiness, and enabling easy removal after use through moisture evaporation [26]. Alginic acid—a natural polymer extracted from brown algae (Phaeophyceae)—and diatomaceous earth have been reported as base materials satisfying these requirements [27]. In this study, alginic acid was selected as the base matrix, with a density of ~1.60 g/cm3 and a molar mass range of 10,000–600,000 g/mol [28], as it reacts effectively with shielding agents to form a gel-like, hardened structure.

The final composition in the modeling pack comprised sodium alginate, Bi2O3, and ZnO (powder, Hunan Mana Materials Technology Co., Ltd., 2022, Changsha, Hunan, China). Furthermore, several additives were incorporated for functional purposes rather than shielding effects, including hyaluronic acid to help retain moisture and enhance adhesion, gellan gum (Tech-Way Co., Ltd., 2022, Zhuji, Zhejiang, China) for viscosity control, and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) to improve film integrity after drying [29,30].

To evaluate shielding performance, three samples were prepared based on the ratio of the primary shielding material, Bi2O3, and the skin-friendly material ZnO. Sample A consisted of 50% Bi2O3 and 10% ZnO; Sample B consisted of 40% Bi2O3 and 20% ZnO; and Sample C consisted of 30% Bi2O3 and 30% ZnO. In all cases, the sodium alginate content was fixed at 40% to fabricate the modeling pack. These ratios were selected to investigate how effectively ZnO particles filled interstitial gaps between the larger Bi2O3 particles, thereby improving shielding efficiency.

Sample preparation involved mixing the Bi2O3 and ZnO powders with distilled water and dispersing them via ultrasonication for 30 min. Sodium alginate and additives were completely dissolved upon stirring at 60–70 °C. PVA was then incorporated, and the mixture was stirred at 500 rpm for 1 h to afford a modeling pack [31]. The mixture was cast onto a flat surface and hardened by spraying with calcium chloride (CaCl2) to yield the final samples. The particle size and dispersibility of the shielding materials on the surface of the modeling pack were examined via field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; Hitachi, S-4800, Hong Kong, China) [32]. Porosity was visually confirmed through this analysis. As shown in Figure 1, the shielding performances and porosities of the three samples were compared. Each sample was prepared in four different thicknesses (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mm) to evaluate the influence of thickness on shielding performance.

Figure 1.

Modeling packs prepared with three compositional ratios: (A) 50% bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and 10% zinc oxide (ZnO); (B) 40% bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and 20% zinc oxide (ZnO); (C) 30% bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) and 30% zinc oxide (ZnO).

2.2. Evaluation of Shielding Performance

To reduce indirect exposure to medical radiation environments, it is necessary to maintain a safe distance. When this is not possible, scattered radiation must be mitigated using appropriate shielding tools [33]. Radiation shielding involves decreasing the intensity of incident radiation through attenuation within the shielding medium. The density and thickness of the shielding material play crucial roles in this process, as expressed in Equations (1) and (2) [34]. Accordingly, the interaction of incident radiation can be calculated using the well-established Beer–Lambert law (Equations (1) and (2)) [35]:

where and represent the intensities of incident and transmitted photon energy, respectively; and denote the linear and mass attenuation coefficients, respectively; and indicate thickness and the mass thickness per unit area of the shielding sheet, respectively; and ) refers to the material density. Therefore, the interaction of incident energy is influenced by the density of the shielding sheet [36]. For effective protection of transient and active areas such as the dorsal skin of the hand, which are influenced by both the absorption coefficient of the material and its thickness, it is necessary to establish a minimum functional thickness and design a structure that does not hinder mobility [37]. Structural design in this context requires minimizing porosity [38].

Porosity can be expressed by combining the density of the shielding material with the overall density of the proposed modeling pack. Bulk density refers to the mass per unit volume in its natural state, including pores, representing the overall mixture, whereas true density refers to the mass per unit volume of the shielding material. Accordingly, porosity can be defined using Equation (3) [39].

The bulk density () of the shielding material and bulk density () of the base material are defined by Equation (4), and these parameters are directly related to porosity [40]:

where is the shielding material weight, represents the shielding barrier weight, is the shielding material volume, denotes the shielding barrier volume, and is the shielding barrier air space.

Therefore, the final porosity of the shielding device can be determined using Equations (3) and (4) and can also be indirectly estimated from the bulk density [41]. Thus, porosity can be derived from the mass and density of the shielding material. To convert the monoenergetic medical radiation into an effective energy, the half-value layer (HVL) was determined by calculating the slope from the attenuation coefficient law (). From this slope, the linear attenuation coefficient () was obtained, and HVL was then calculated using [42]. The effective energy was determined by comparing the obtained HVL value with the corresponding HVL for monoenergetic radiation using Hubbell’s mass attenuation coefficient tables [43].

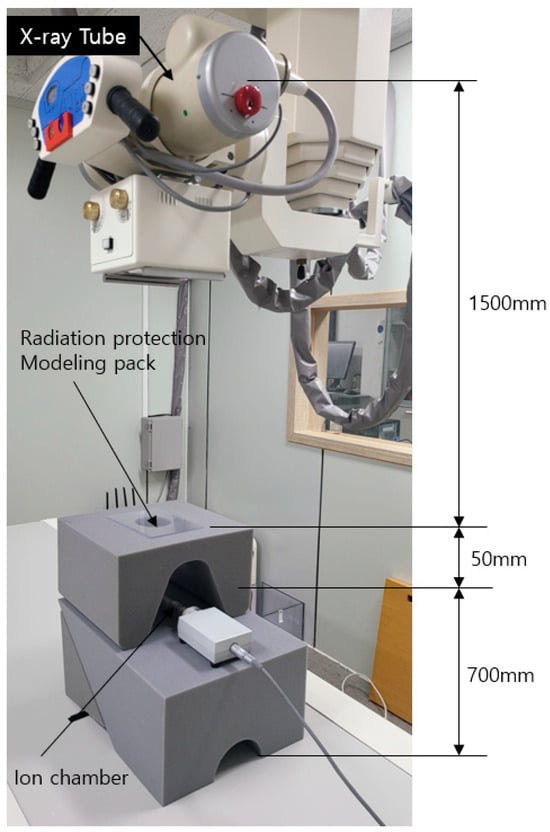

An X-ray generator (Toshiba E7239, 150 kV, 500 mA, 1999, Tokyo, Japan) was operated for ten exposures, and the mean value was used for analysis. The dose detector (DosiMax Plus 1, 2019; IBA Dosimetry Corp., Schwarzenbruck, Germany) was calibrated prior to measurement. The geometric configuration of the X-ray measurement system is shown in Figure 2. For the final performance evaluation, the radiation shielding efficiency was calculated using Equation (5):

where represents the measured exposure dose with the modeling pack positioned between the X-ray source and the detector, while represents the exposure dose measured without the modeling pack [44]. Here, represents the incident dose (mR), while is the transmitted dose (mR).

Figure 2.

Geometric configuration of the medical radiation shielding experiment using the modeling pack.

3. Results

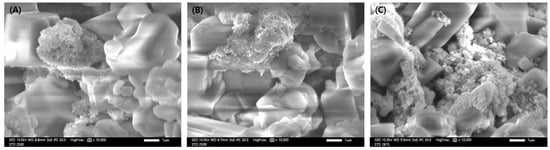

The primary difference between the modeling pack and conventional shielding cream lies in their moisture content. The modeling pack is in a state where most of the moisture has evaporated, whereas the cream retains only a small amount of moisture. As shown in Figure 3, the interparticle porosity of the modeling pack was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The corresponding quantitative results are presented in Table 1. At a thickness of 1.0 mm, no significant difference in porosity was observed, which may be attributed to the fluidity of the modeling pack material. SEM images in Figure 3 show visible differences in interparticle spacing and confirm the incorporation of ZnO particles between Bi2O3 particles. The porosities of the fabricated samples ranged from 19% to 22% (Table 1). When the same base materials were used, the total mass of the sample was the primary factor determining porosity. Consequently, samples with a higher Bi2O3 content, which is a denser material, exhibited higher porosity. Although this increase in porosity may theoretically reduce shielding efficiency, samples containing less Bi2O3 exhibited reduced shielding performance (Figure 4) and lower porosity values (Table 1). The pores formed in the composite mixing state were visually confirmed (Figure 5). A comparison between Figure 3A,C indicates no substantial differences in the overall structure, although a larger fraction of alginate appears to be present, as shown in Figure 3C. Therefore, it can be inferred that spacing between Bi2O3 and ZnO particles remains largely consistent across compositions.

Figure 3.

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images of the modeling pack: (A) 50% bismuth oxide, 10% zinc oxide; (B) 40% bismuth oxide, 20% zinc oxide; (C) 30% bismuth oxide, 30% zinc oxide. The alginate content was fixed at 40% in all samples.

Table 1.

Porosity of the modeling pack.

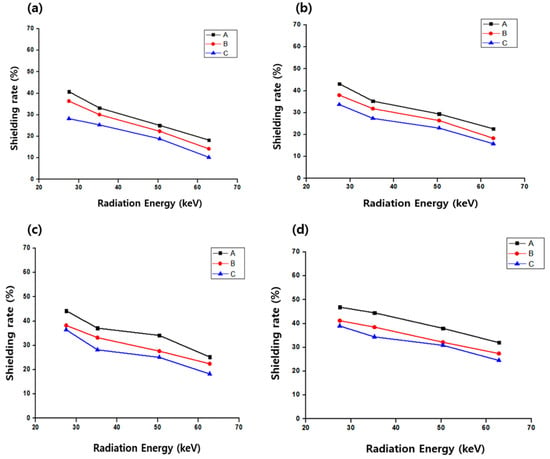

Figure 4.

Variation in the shielding performance of the modeling pack with different compositions: A, 50% bismuth oxide and 10% zinc oxide; B, 40% bismuth oxide and 20% zinc oxide; C, 30% bismuth oxide and 30% zinc oxide; alginate was fixed at 40%. (a) 0.5 mm, (b) 1.0 mm, (c) 1.5 mm, and (d) 2.0 mm present the changes in shielding efficiency according to coating thickness.

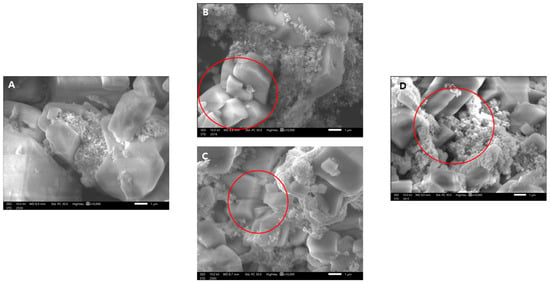

Figure 5.

Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images of composites prepared with bismuth oxide and zinc oxide: (A) 10% zinc oxide, (B,C) 20% zinc oxide, and (D) 30% zinc oxide. The circled region in image B shows particle agglomeration accompanied by the formation of voids, whereas the circled region in (C) indicates well-dispersed particles with appropriate interparticle spacing. The circled region in (D) does not represent individual particles but rather an agglomeration of the base material.

Considering that the composite material is a randomly polydisperse system, as shown in Figure 5A, the interparticle spaces are not sufficiently filled by ZnO, and clear gaps between particles can be observed. In Figure 5B,C, where the proportion of ZnO is increased compared to that in Figure 5A, the dispersion of particles (highlighted by the red circle in Figure 5C) demonstrates that the interparticle spacing can be controlled. Thus, introducing smaller particles to occupy the voids between larger particles is effective. However, as shown in the red circle in Figure 5B, smaller ZnO particles may be displaced by the alginate base material, leading to the formation of air gaps. Furthermore, as shown in the red circle in Figure 5D, excessive distribution of the alginate matrix can promote local aggregation, which may reduce the shielding performance. Therefore, a sufficient quantity of base material and the use of particles with multiple sizes are essential for optimal performance. In conclusion, multimodal particle dispersion according to particle size can reduce the pore size.

The shielding performance of the modeling pack was evaluated by fixing the alginate content at 40% while varying the Bi2O3-to-ZnO ratio. The shielding effects at different coating thicknesses for medical radiation skin protection are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, with radiation attenuation increasing with increasing coating thickness and decreasing incident energy. However, at higher incident radiation energies, the shielding effect decreased, even for thicker coatings. At a coating thickness of 1.0 mm—representative of practical application to the dorsal side of the hand—Sample A, with the highest Bi2O3 content, exhibited a shielding effect of 22.65% at an X-ray effective energy of 62.8 keV, whereas sample C, with the lowest Bi2O3 content, exhibited 15.85% at the same energy level. Overall, the reduction in medical radiation by the modeling pack was relatively low, with a shielding efficiency of less than 50%. In addition, changes in the ZnO content had little effect on the shielding performance.

Table 2.

Medical radiation reduction effect of the 0.5 mm dorsal hand modeling pack.

Table 3.

Medical radiation reduction effect of the 1.0 mm dorsal hand modeling pack.

Table 4.

Medical radiation reduction effect of the 1.5 mm dorsal hand modeling pack.

Table 5.

Medical radiation reduction effect of the 2.0 mm dorsal hand modeling pack.

The variation in shielding performance according to coating thickness of the modeling pack composed of Bi2O3, ZnO, and alginate is shown in Figure 5. As presented in the graph, a thickness of 1.0 mm exhibited a stable pattern in which the decrease and increase in shielding performance occurred at similar rates. The result suggests that a thickness of 1.0 mm can be proposed as a reproducible thickness.

4. Discussion

In medical institutions, products that are applied directly to the skin for radiation shielding have not yet been widely implemented; instead, indirect protective devices such as aprons, gloves, goggles, and caps are commonly used [45]. Although several protective creams for patients have been proposed, these are primarily intended to reduce skin damage occurring during radiotherapy and to promote skin regeneration [46]. To improve the performance of such protective creams, some studies and commercial products have incorporated shielding materials to provide intrinsic radiation-protective effects, and several of these have already been commercialized.

As demonstrated in this study, materials applied directly to the skin generally provide limited radiation shielding. Moreover, in clinical practice, direct skin exposure to radiation is relatively uncommon [47]. However, during medical procedures such as surgery or in patient protection and support activities, direct radiation exposure can occur [48]. Under such conditions, alternative shielding models that differ from conventional protective tools are required. Composite shielding materials, such as modeling packs, offer a promising approach to meet this need [49].

In radiation-shielding modeling packs, sufficient shielding efficiency and user mobility can be achieved if the shielding performance is reproducible through simple optimization of the coating thickness. Unlike conventional protective creams, modeling packs may overcome limitations related to poor skin adhesion, restricted wearing duration, and difficult removal [50]. Partial shielding from direct radiation and the attenuation of scattered radiation can provide an important protective model.

To enhance shielding performance, interparticle voids within the composite can be partially addressed by diversifying the particle sizes. However, because the modeling pack retains a fluid or semi-fluid character similar to shielding creams, irregular interparticle spacing may occur, making reproducibility challenging. Therefore, the most effective strategies for minimizing interparticle voids include reducing particle size, diversifying particle size distribution, and eliminating entrapped air [51].

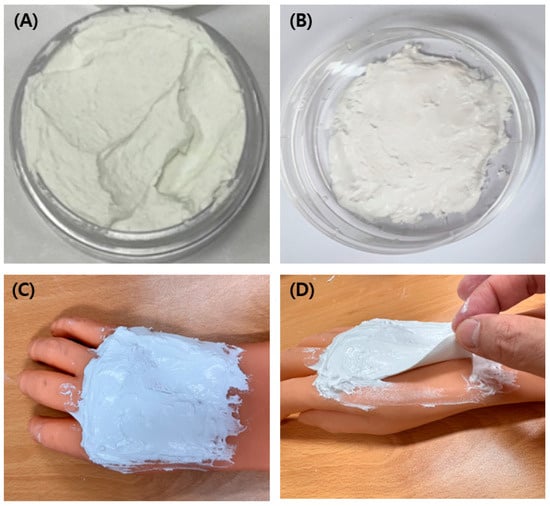

ZnO, a common cosmetic ingredient widely used for UV protection, exhibited little independent effect on radiation shielding in this study. Thus, the assumption that high UV protection correlates with low-dose radiation attenuation remains unsubstantiated. Finally, the modeling pack presented in this study shows practical differences compared to conventional radiation-shielding creams. Figure 6A shows the cream-based shielding material and Figure 6B shows the modeling pack material. As shown in Figure 6C, the shielding cream exhibits reduced adhesion due to flowability from even small amounts of moisture. In contrast, Figure 6D shows that the modeling pack can be easily spread onto the skin before hardening, adhere effectively through shrinkage during solidification, and be easily removed after use. These properties collectively support its potential for practical protection applications.

Figure 6.

Comparison between the developed modeling pack and a shielding cream: (A) shielding cream prepared with barium sulfate; (B) modeling pack containing 50% bismuth oxide, 10% zinc oxide, and 40% alginate; (C) shielding cream applied on the dorsal hand; and (D) modeling pack applied on the dorsal hand.

The results of this study demonstrate that the effectiveness of medical radiation attenuation is primarily dependent on the Bi2O3 content. Accordingly, higher concentrations of Bi2O3 yielded superior shielding performance, which may serve as a useful guideline for the development of future radiation-protective products. One limitation of this study is the need to investigate a wider variety of environmentally friendly materials across a broader energy spectrum.

Radiation protection in medical settings is of critical importance, and active shielding measures supported by continuous monitoring are required. As indicated by the present findings, further research into alternative shielding models, such as the developed modeling pack, which offers improved skin adhesion compared to conventional shielding creams, is necessary.

5. Conclusions

The developed modeling pack offers practical advantages over conventional radiation-shielding creams, including easier application and removal, as well as tunable shielding performance according to coating thickness. The experimental results showed that thicker layers and higher Bi2O3 contents provided better shielding effects. For example, at a thickness of 2.0 mm, the modeling pack containing 50% Bi2O3 achieved a shielding efficiency of 32.02% at 62.8 keV. Notably, at a 1.0 mm thickness, an almost linear reduction in radiation was observed. Microscopic analysis further revealed that when the Bi2O3 and ZnO contents were both approximately 30%, interparticle voids were reduced. However, this did not lead to substantial differences in the shielding performance, which can be attributed to the fluid characteristics of the product. Overall, the findings of this study suggest that modeling packs represent a promising model for localized skin protection against medical radiation, offering tunable performance, ease of use, and potential adaptability for clinical application.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (RS-2025-19643007).

Data Availability Statement

All data generated during this study are included in this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| FE-SEM | Field emission scanning electron microscopy |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| HVC | Half-value layer |

References

- Rodrigues, B.V.; Lopes, P.C.; Mello-Moura, A.C.; Flores-Fraile, J.; Veiga, N. Literacy in the scope of radiation protection for healthcare professionals exposed to ionizing radiation: A systematic review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelodun, M.; Anyanwu, E. Comprehensive risk management and safety strategies in radiation use in medical imaging. Int. J. Front. Med. Surg. Res. 2024, 6, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Sarma, B.; Chaturvedi, K.; Malvi, D.; Srivastava, A.K. Emerging graphene and carbon nanotube-based carbon composites as radiations shielding materials for X-rays and gamma rays: A review. Compos. Interfaces 2023, 30, 223–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.C.; Çubukçu, N.Ü.; Oner, E. The disadvantages of lead aprons and the need for innovative protective clothing: A survey study on healthcare workers’ opinions and experiences. Usak Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2024, 7, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.; Rocha, R.; Silva, C.J.; Barroso, H.; Botelho, J.; Machado, V.; Mendes, J.J.; Oliveria, J.; Loureiro, M.V.; Marques, A.C. Gamma radiation for sterilization of textile based materials for personal protective equipment. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 194, 109750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.B.; Khandelwal, C.; Dangayach, G.S. Advancements in healthcare materials: Unraveling the impact of processing techniques on biocompatibility and performance. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2024, 63, 1608–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.B.; Khandelwal, C.; Dangayach, G.S. Revolutionizing healthcare materials: Innovations in processing, advancements, and challenges for enhanced medical device integration and performance. J. Micromanuf. 2024, 25165984241256234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, D.; Almatari, M.; Tumayhi, M.; Alanazi, W.; Shrefan, M.; Agealy, W.; Alabdan, N.; Tumayhi, B.; Alanazi, I.; Ajeebi, T. Occupational exposure of scatter radiation and proper protective methods. J. Healthc. Sci. 2022, 2, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamoto, K.; Moritake, T.; Kowatari, M.; Morota, K.; Nakagami, K.; Matsuzaki, S.; Nihei, S.; Kamochi, M.; Kunugita, N. Occupational radiation dose on the hand of assisting medical staff in diagnostic CT scans. Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2023, 199, 1774–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmoonfar, R.; Moslehi, M.; Khoshghadam, A.; Khodaveisi, T. Occupational radiation exposure of surgical teams: A mini-review on radiation protection in the operating room. Avicenna J. Care Health Oper. Room 2024, 2, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S.A.; Rosli, N.N.F.; Farizah, N.H. The effectiveness of radiation protection in medical field-A short review. Malays. J. Appl. Sci. 2023, 8, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, F.H.; Razakamanantsoa, L.; Ben Ammar, M.; Lehrer, R.; Haffaf, I.; El-Mouhadi, S.; Gardavaud, F.; Najdawi, M.; Barral, M. Ergonomics in interventional radiology: Awareness is mandatory. Medicina 2021, 57, 500. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/medicina (accessed on 16 October 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulawik-Pióro, A.; Miastkowska, M.; Bialik-Wąs, K.; Zelga, P.; Piotrowska, A. Physicochemical properties and composition of peristomal skin care products: A narrative review. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asal, S.; Erenturk, S.A.; Haciyakupoglu, S. Bentonite based ceramic materials from a perspective of gamma-ray shielding: Preparation, characterization and performance evaluation. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2021, 53, 1634–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfi, M.Y.; El-Soad, A.A.; Alresheedi, N.M.; Alsufyani, S.J.; Mahmoud, K.A. The impact of pressure rate on the physical, structural and gamma-ray shielding capabilities of novel light-weight clay bricks. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 4938–4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, B.; Tyagi, A.K. Characterization and biocompatibility studies of lead free X-ray shielding polymer composite for healthcare application. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2017, 138, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.; Chen, M.; Xi, Y.; Cheng, W.; Mao, C.; Xu, T.; Zhang, X.; Lin, C.; Gao, W.; et al. Efficient angiogenesis-based diabetic wound healing/skin reconstruction through bioactive antibacterial adhesive ultraviolet shielding nanodressing with exosome release. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 10279–10293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Guo, S. High-efficiency, flexibility and lead-free X-ray shielding multilayered polymer composites: Layered structure design and shielding mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobczak, J.; Cioch, K.; Żyła, G. Paraffin-based composites containing high density particles: Lead and bismuth and its’ oxides as γ-ray shielding materials: An experimental study. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafi, K.; El-Nahal, M.A.; Al-Saleh, W.M.; Almutairi, H.M.; Abdel-Gawad, E.H.; Elsafi, M. Utilization of waste marble and Bi2O3-NPs as a sustainable replacement for lead materials for radiation shielding applications. Ceramics 2024, 7, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Alomayrah, N.; Kırkbınar, M.; Çalışkan, F.; Mansour, H. Recycling of borosilicate waste glasses through doping with bismuth (III) oxide (Bi2O3): Enhancing the structure and radiation shielding properties. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 6715–6723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.B.; Kim, Y.W.; Lim, S.K.; Roh, T.H.; Bang, D.Y.; Choi, S.M.; Lim, D.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Baek, S.H.; Kim, M.K. Risk assessment of zinc oxide, a cosmetic ingredient used as a UV filter of sunscreens. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B 2017, 20, 155–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.; Ali, W.; Khan, N.Z.; Aasim, M.; Khan, T.; Khan, A.A. Delphinium uncinatum mediated biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles and in-vitro evaluation of their antioxidant, cytotoxic, antimicrobial, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-aging activities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2023, 30, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonkwo, U.C.; Idumah, C.I.; Okafor, C.E.; Ezeani, E.O. Construction of radiation attenuating polymeric nanocomposites and multifaceted applications: A review. Polym. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 1639–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pearce, A.K.; Dove, A.P.; O’Reilly, R.K. Precise tuning of polymeric fiber dimensions to enhance the mechanical properties of alginate hydrogel matrices. Polymers 2021, 13, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, M.H.; van Hilst, Q.; Cui, X.; Ramaswamy, Y.; Woodfield, T.; Rnjak-Kovacina, J.; Wise, S.G.; Lim, K.S. From Adhesion to Detachment: Strategies to Design Tissue-Adhesive Hydrogels. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2024, 4, 2300090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaghari, S.; Velagala, S.; Alla, R.K.; Av, R. Advances in alginate impression materials: A review. Int. J. Dent. Mater. 2019, 1, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draget, K.I.; Skjåk-Bræk, G.; Stokke, B.T. Similarities and differences between alginic acid gels and ionically crosslinked alginate gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2006, 20, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.C.; Bersaneti, G.T.; Mali, S.; Celligoi, M.A.P.C. Films based on blends of polyvinyl alcohol and microbial hyaluronic acid. Braz. Arc. Biol. Technol. 2020, 63, e20190386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, P.; Moreira, A.; Lopes, B.; Sousa, A.C.; Coelho, A.; Rêma, A.; Balca, M.; Atayde, L.; Mendonca, C.; da Silva, L.P.; et al. Honey, Gellan Gum, and Hyaluronic Acid as Therapeutic Approaches for Skin Regeneration. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winingrum, L.A.; Zai, K. Optimization of peel-off gel mask formula containing Binahong (Anredera cordifolia) leaf extract based PVA CMC-alginate combination. J. Res. Pharm. 2024, 28, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, W.; Ramli, R.M.; Khazaalah, T.H.; Azman, N.Z.N.; Nawafleh, T.M.; Salem, F. Enhancing X-ray radiation protection with novel liquid silicone rubber composites: A promising alternative to lead aprons. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 3608–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizik, D.G.; Gosselin, K.P.; Burke, R.F.; Goldstein, J.A. Comprehensive radiation shield minimizes operator radiation exposure in coronary and structural heart procedures. Cardiovasc. Revasc. Med. 2024, 64, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmahroug, Y.; Tellili, B.; Souga, C. Determination of total mass attenuation coefficients, effective atomic numbers and electron densities for different shielding materials. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2015, 75, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, H.; Milan, K.G.; Sadr, A.; Sedighy, S.H.; Malekie, S.; Mosayebi, A. Multilayer radiation shield for satellite electronic components protection. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, X.; Zhao, J.; Song, S.; Zhou, N.; Fan, J.; Tian, B.; Du, Y. Layered structural engineering of Bi2O3/PP and WO3/PP composites for γ-ray shielding in high energy range: Anisotropic attenuation mechanisms via Monte Carlo simulation and experiments. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 10324–10336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassemiro, A.; Motta, L.J.; Fiadeiro, P.; Fonseca, E. Predictive Model of the Effects of Skin Phototype and Body Mass Index on Photobiomodulation Therapy for Orofacial Disorders. Photonics 2024, 11, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.A.H.; Rashid, R.S.M.; Amran, M.; Hejazii, F.; Azreen, N.M.; Fediuk, R.; Voo, Y.L.; Vatin, N.I.; Idris, M.I. Recent trends in advanced radiation shielding concrete for construction of facilities: Materials and properties. Polymers 2022, 14, 2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciari, M. Nomes de lugar: Confim. Rev. Let. 2005, 45, 13–22. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26459823 (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Qiu, J.; Khalloufi, S.; Martynenko, A.; Van Dalen, G.; Schutyser, M.; Almeida-Rivera, C. Porosity, bulk density, and volume reduction during drying: Review of measurement methods and coefficient determinations. Dry. Technol. 2015, 33, 1681–1699.34491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nodagala, R.; Ponnada, T.R. Influence of Bi2O3 Concentration on Optical and Gamma Ray Shielding Properties of BaTiO3 Ceramics. Appl. Res. 2025, 4, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, B.; Hupe, O. Can half value layer measurements be used together with the effective energy to obtain conversion coefficients for X-ray spectra? Radiat. Prot. Dosim. 2017, 173, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Osman, A.M. Evaluation of radiation shielding effectiveness of some metallic alloys used in the nuclear facilities. J. Nucl. Eng. Radiat. Sci. 2025, 11, 031001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhmayies, S.J. Advanced Composites, Advances in Material Research and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-031-42730-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, R.T.; Mohammed, H.A.; Zead, M.M.A. Operating room nurses’ knowledge and practice regarding radiation Protection from C-arm fluoroscopy machine. Egypt. Nurs. J. 2025, 22, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasadziński, K.; Spałek, M.J.; Rutkowski, P. Modern dressings in prevention and therapy of acute and chronic radiation dermatitis—A literature review. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, L.; Passante, M.; Cameli, N.; Cristaudo, A.; Patruno, C.; Nisticò, S.P.; Silvestri, M. Skin manifestations after ionizing radiation exposure: A systematic review. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, N.W.; Parrish, J.M.; Sheha, E.D.; Singh, K. Intraoperative risks of radiation exposure for the surgeon and patient. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chunglok, W.; Nwabor, O.F.; Ushir, Y.V.; Singh, S.; Panpipat, W. Hydrophilic biopolymer matrix antibacterial peel-off facial mask functionalized with biogenic nanostructured material for cosmeceutical applications. J. Pol. Environ. 2022, 30, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.C.; Son, J.S. Manufacturing and performance evaluation of medical radiation shielding fiber with plasma thermal spray coating technology. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.A.; Razzaq, A.; Dormocara, A.; You, B.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Iqbal, H.; Cui, J.H. Current trends in inhaled pharmaceuticals: Challenges and opportunities in respiratory infections treatment. J. Pharm. Investig. 2025, 55, 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).