Abstract

On the road to developing more sustainable and cost-efficient carbon fibres (CFs), replacing the conventional polyacrylonitrile (PAN) precursor with polyethylene (PE) is a promising alternative. Yet most PE-CF studies focus on fibre properties at laboratory or pilot scale and largely overlook scalability—especially in melt-spinning, where precursor filament counts have typically been limited to 32–100, far below industrial CF tows (1000–48,000). This study addresses that gap by (i) modifying a staple-fibre melt-spinning line (MSFP) to directly produce a 10,000-filament PE precursor and (ii) demonstrating inline filament merging on an industrial yarn (IDY) plant at Institut für Textiltechnik (ITA) as a pragmatic scale-up route. Direct 10 k spinning proved technically feasible but did not meet convertibility targets owing to inhomogeneous extrusion and quench: the MSFP precursor showed 18.1 ± 2.0 µm filament diameter, 21.9 ± 3.8 cN/tex tenacity and 130.8 ± 40.8% elongation (total solid draw ratio 2.02). In contrast, the IDY route delivered a fine and uniform precursor with a 9.43 ± 0.02 µm filament diameter, 38.42 ± 0.43 cN/tex tenacity, 15.91 ± 0.76% elongation, and 15.32 ± 1.16% shrinkage at 120 °C (total solid draw ratio 4.55). After discontinuous sulfonation, TGA indicated superior cross-linking of the IDY precursor (≈15% mass loss at 400–600 °C) versus MSFP (≈18%). Inline merging doubled filament count inline and small-scale plying enabled a 6 k tow. Transferring the IDY precursor into continuous sulfonation and carbonisation yielded PE-based CF with a filament diameter < 8.5 µm, tensile strength up to 2.0 GPa, tensile modulus up to 170 GPa, and elongation at break up to 1.75%, without surface defects. The results establish a clear scale-up roadmap: prioritise homogeneous fine-filament extrusion at low throughputs, co-develop segmented quench, and use a stepwise strategy (1–2 k filaments → inline merging → ≥6 k) to enable industrially relevant, cost-effective PE-based CF production.

1. Introduction

Carbon fibres (CFs) have become indispensable materials in high-performance applications due to their outstanding mechanical properties and low weight []. They are widely used in aerospace, automotive engineering, wind energy, and sports equipment industries []. The conventional production of CF predominantly relies on polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as a precursor []. However, approximately 50% of the total production costs of CFs are attributed to the manufacture of the PAN precursor fibre. This is primarily due to the energy- and time-intensive wet-spinning process, as well as the necessary recovery of solvents, which limits the application of CF in cost-sensitive industries [,,].

The use of new precursors offers the greatest opportunity for cost savings. Polyethylene (PE) is an ideal, cost-effective precursor due to its high carbon content, low raw material costs, high availability, and melt-processability. Using PE facilitates a more efficient and environmentally friendly fibre production through melt-spinning. While the stabilisation of PAN fibres is achieved via heat treatment in an air atmosphere, this is not feasible for PE due to its thermoplastic properties. Instead, stabilisation of PE is achieved through sulfonation, where the fibre is passed through sulfuric acid heated to 120 °C. The incorporation of sulfo groups into the polymer structure renders the fibre infusible, allowing it to be carbonised subsequently [,,,].

One of the primary challenges in producing PE precursors is the comparatively low filament count in contrast to PAN-based processes. While PAN precursor fibres, with filament counts ranging from 6000 to 50,000, are directly produced via wet-spinning [], melt-spinning research for PE precursor fibres typically yields only about 32–100 filaments [,,,,]. Consequently, achieving higher filament counts requires an additional consolidation step, which complicates the process and introduces potential quality issues. Moreover, conventional melt-spinning facilities are not designed for such large filament numbers, as there is currently no industrial application for melt-spun filament yarns with such high filament counts. This study represents the first attempt to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale research and industrial-scale production of polyethylene-based carbon fibres. Specifically, it focuses on upscaling the first stage of the process chain—the melt-spinning of the precursor—to produce a continuous 10,000-filament yarn. In contrast to previous studies that relied on small-scale production, this work adapts and modifies existing standard melt-spinning equipment originally designed for staple fibre production. This approach not only demonstrates the technical feasibility of large-scale PE precursor manufacturing but also provides crucial insights into process limitations, equipment requirements, and potential pathways for future industrial implementation. The findings therefore contribute an essential step towards establishing polyethylene as cost-efficient precursor material for next-generation carbon fibre production.

1.1. State of the Art of PAN-Based Carbon Fibre Production

Approximately 96% of all CFs are produced from PAN-based precursors []. In 2024, global demand for CF was approximately 126,500 tonnes, primarily supplied by a few companies []. Worldwide production capacity in 2023 was around 190,000 tonnes [].

PAN-based carbon fibre production involves four steps [,,,]:

- Wet-Spinning of the Precursor Fibre: PAN polymer is dissolved in a suitable solvent (e.g., Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) or Dimethylformamide (DMF)) and spun into fibres using wet-spinning technology. The fibres are then stretched to align the polymer molecules preferentially.

- Stabilisation: The stretched PAN fibres undergo thermal treatment at temperatures between 200 and 300 °C in an oxidising atmosphere (air). This process induces cyclisation and oxidation of the nitrile groups, forming a highly crosslinked, infusible structure that prevents melting during subsequent carbonisation.

- Carbonisation: The stabilised fibres are carbonised under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen) at temperatures ranging from 1000 to 1500 °C. Non-carbon elements are removed, and a graphitic structure is formed.

- Post-Treatment: After carbonisation, surface treatment is carried out and sizing applied to enhance adhesion in composite materials, and to protect the fibres.

Carbon fibre costs exhibit variability based on the application domain, with values ranging from 13 EUR/kg in the automotive sector to 96 EUR/kg in the aerospace sector []. The high production costs are mainly due to the energy- and time-intensive wetsspinning process and the necessary solvent recovery and recycling. The precursor accounts for about 50% of the total cost of carbon fibre production [], limiting the use of CF in cost-sensitive industries such as automotive manufacturing.

1.2. PE-Based Carbon Fibre Production—Advantages, Process Chain, and Current Developments

Polyethylene (PE) is a promising alternative precursor for carbon fibre production. PE offers several advantages over PAN [,]:

- High Carbon Content: PE has a carbon content of about 85.7%, higher than PAN’s 67.9%, leading to higher carbon yields after carbonisation.

- Low Raw Material Costs and High Availability: PE is a mass-produced commodity polymer, making it cost-effective and widely available.

- Melt-Processability: Unlike PAN, PE can be processed using melt-spinning, a faster, more efficient, and environmentally friendly method that eliminates the need for solvents.

PE-based carbon fibre production involves:

- Melt-Spinning of the Precursor Fibre: PE is melted and extruded through spinnerets to form filaments. These filaments solidify in a cooling air stream. The fibres are then drawn to align the molecular chains and increase crystallinity [].

- Stabilisation via Sulfonation: Due to its thermoplastic nature, PE cannot be stabilised through thermal treatment alone, as it would melt upon heating. Instead, PE fibres are stabilised via sulfonation, where the fibres are passed through sulfuric acid heated to 120 °C. Sulfo groups are incorporated into the polymer structure, cross-linking the chains and rendering the fibre infusible [,].

- Carbonisation: The sulfonated PE fibres are carbonised under inert atmosphere at temperatures up to 1300 °C. Non-carbon elements are removed, and a graphitic-like structure is formed [].

- Post-Treatment: After carbonisation, surface treatment is applied to enhance adhesion in composite materials, and sizing is added to protect the fibres.

A comparison of PAN- and PE-based CF production highlighting its main differences is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of PAN- and PE-based CF production [,].

In 1990, Postema et al. laid the groundwork for the development of PE-based carbon fibres (CFs) with their pioneering work on amorphous carbon fibres derived from LLDPE []. Since then, most research has focused on improving the stabilisation process of PE-based precursors through various methods, primarily using sulfonation techniques under atmospheric conditions [,,,,], under increased hydrostatic pressure [], or by combining sulphur-based treatments with irradiation techniques such as electron-beam [,,] or UV irradiation [,]. Additional research approaches looked into the use of additives such as diphenylamine [] or Boron-doping and graphitisation []. The overarching goal of the research on the field is to enhance the mechanical properties of PE-based CFs while making the production process safer, more sustainable, and more efficient [,].

In parallel, extensive research has been conducted on the melt-spinning of PE precursor fibres, which represents the first step of the process chain. Current investigations primarily focus on optimising spinning and drawing parameters to control molecular orientation and crystallinity, as these structural features strongly influence the subsequent stabilisation and carbonisation behaviour []. Building on the early work of Ward and Wilding, who established the fundamental relationship between draw ratio and chain orientation in melt-spun polyethylene fibres [], subsequent studies by Penning et al. demonstrated that heated-air spinning environments delay crystallisation and thus enable higher draw ratios before solidification []. Recent industrial developments by Dow Global Technologies [,,] have further advanced this understanding, introducing multi-stage drawing concepts—up to 500× in the melt-state followed by solid-state drawing—to achieve filament diameters below 10 µm and enhanced molecular alignment.

Wortberg adapted an IDY process to produce HDPE-based precursors with high orientation and mechanical integrity. These studies aim to identify processing windows that maximise drawability and chain alignment while maintaining sufficient amorphous regions to enable uniform sulfonation. Further investigations address polymer type selection—particularly HDPE versus LLDPE—to balance spinnability, crystallinity, and stabilisation kinetics [,,]. Across all studies, research has primarily focused on understanding how spinning parameters and polymer structure influence the orientation, crystallinity, and subsequent chemical stabilisation behaviour of PE precursor fibres. The existing work has provided valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of drawing, diffusion, and cross-linking during stabilisation. However, no study to date has reported an attempt to directly produce a PE precursor with an industrially relevant filament count using melt-spinning.

1.3. Challenges in PE-Based CF Production

Despite its potential, PE-based carbon fibre production faces several challenges:

- Low Precursor Filament Count: Current melt-spinning technology for PE typically produces yarns with 32–100 filaments. Industrial applications require higher filament counts to facilitate processing and optimise the properties of the resulting CF [].

- Stabilisation via Sulfonation: Controlling the sulfonation process is critical to ensure uniform stabilisation and to avoid defects in the fibre [].

- Mechanical Properties: Further research is needed to enhance the mechanical properties of PE-based CF to match those of PAN-based fibres [,].

PE-based carbon fibre (CF) production holds considerable potential to reduce manufacturing costs by up to 50%, thereby enabling wider adoption of CF in mass-market applications [,]. The primary distinctions compared to PAN-based CF production involve differences in spinning and stabilisation methodologies. Specifically, PE precursor fibres are produced through melt-spinning and chemically stabilised via sulfonation, whereas PAN precursor fibres require wet-spinning and thermal stabilisation [,]. Achieving higher filament counts in PE precursor production represents a critical step toward industrial applicability [,,].

The primary objective of this study is to address the limitations inherent to the conventional two-step PE precursor spinning and combining process by developing a single-step production method through substantial upscaling of the filament count. This research utilises standard industrial equipment commonly employed in other textile processes, adapting and combining them to suit this novel application. Specifically, modifications were made to an existing melt-spinning plant designed for staple fibres. By circumventing conventional processing steps such as crimping, cutting, and can deposition, and instead integrating a winder for direct precursor fibre collection, high-filament-count precursors can be produced in a single step.

This study further examines the technical challenges and limitations associated with this upscaling approach. It evaluates the properties of the resulting precursor fibres and the derived CF, comparing them with PE precursors produced via the two-step process involving spinning industrial yarn at lower filament counts, followed by filament combination. To further increase the filament count in this experimental approach, extruded filaments from two spinnerets are combined inline into a single yarn, effectively doubling the filament count within the yarn. Particular attention is given to understanding how the precursor manufacturing method influences the mechanical properties of both precursors and resulting CF.

In the context of upscaling, it remains imperative to ensure that previously established mechanical requirements for PE precursor fibres continue to be met, as detailed in the subsequent section.

1.4. Mechanical Requirements for PE Precursor Fibres

The mechanical properties of PE precursor fibres are critical for their successful conversion into CF and significantly influence the properties of the resulting carbon fibres [,,]. A precursor tensile strength of 25.7 ± 2.7 cN/tex enables the production of carbon fibres with tensile strength values of up to 2.22 GPa and an elastic modulus of up to 170 GPa. The projected market price of these carbon fibres is approximately 11.14 EUR/kg [].

The mechanical properties detailed below focus specifically on ensuring convertibility—effective stabilisation and carbonisation of the fibres [,]. The targeted mechanical requirements for PE precursor fibres include the following:

Single-filament diameter: Approximately 10 µm. This filament diameter facilitates efficient and uniform sulfonation during the stabilisation process by minimising the diffusion path of sulfonating agents. A precursor filament diameter of about 10 µm yields a carbon fibre filament diameter around 7 µm, consistent with the dimensions typically observed for PAN-based CF [].

Tensile strength: Greater than 20 cN/tex. Adequate tensile strength is crucial for maintaining fibre integrity during the mechanical stresses encountered during sulfonation and carbonisation. This ensures that the fibres remain intact under the necessary processing tensions [].

Elongation at break: Less than 100%. Controlled elongation at break prevents excessive fibre stretching under tension, reducing the risk of defects or breakage. Maintaining molecular orientation is essential for effective stabilisation and carbonisation processes [].

Shrinkage at 120 °C: Less than 30%. Minimising shrinkage at elevated temperatures is vital to avoid undesired fibre contraction during thermal treatments, which could introduce stresses and deformations, thereby compromising fibre integrity and hindering conversion efficiency []. The shrinkage is determined at 120 °C to allow insight into the entropic shrinkage during sulfonation, with the sulfonation process being carried out at that temperature.

The mechanical requirements for PE precursor fibres are summarised again in Table 2, representing the target parameters for the experiments.

Table 2.

Mechanical Requirements for PE Precursor Fibres to Ensure Convertibility.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Production Methods

2.1.1. Description of the Modification of the Melt-Spinning Facility for Staple Fibres

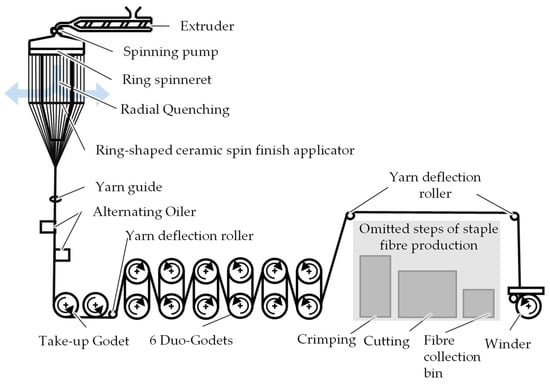

To enable the production of PE precursor fibres with a high filament count a semi-industrial staple fibre pilot line developed by Neumag, Neumünster, Germany, was modified.

The spinneret used was a 10,000-hole ring spinneret with a hole diameter of 0.28 mm and a hole length of 0.56 mm. The filaments were extruded from the spinneret and cooled from the inside out using radial air blowing. The spin finish was applied three times: once through a ring ceramic and then via two double-slot oilers.

After the take-up godet, the yarn was drawn over six pairs of godets. The yarn was then guided over the crimping and cutting units. To wind the yarn directly, a XT3 winder, from Georg Sahm GmbH & Co. KG, Eschwege, Germany, was installed (see Figure 1). By installing a winder, the usual process of crimping and cutting was bypassed, allowing continuous filament yarn to be produced.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the modified staple fibre plant with omitted process steps and installed winder.

Adjustments for Processing Yarns with High Filament Counts

- Cooling: Due to the high filament count, efficient cooling is crucial. Radial air blowing from the inside ensured uniform cooling of the filaments.

- Yarn Guidance: Guides were installed to prevent twisting or entanglement of the yarn.

- Winding: The winder was adjusted to handle the low production speed and large yarn cross-section.

Process Parameters and Procedure of the Upscaling Trials—Melt-Spinning Facility for Staple Fibres

The process parameters of the settings are provided in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. The staple fibre plant operated at a production speed of 100 m/min.

Table 3.

Extruder and spinneret temperatures of upscaling trials.

Table 4.

General process parameters of the upscaling trials.

Table 5.

Process parameters of godets.

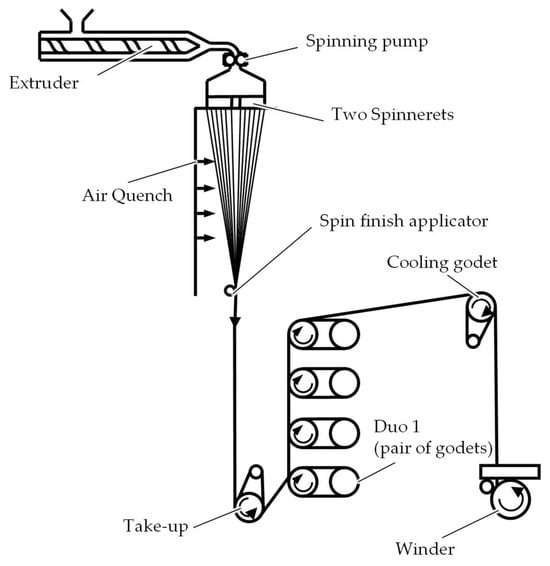

2.1.2. Production of Comparative PE-Fibre at ITA

In comparison, the IDY plant at ITA of RWTH Aachen University was used. The plant has two spinning positions. Both spinning positions were utilised to produce yarns with 96 filaments each, which were then combined inline to form a yarn with 192 filaments. The production speed at the ITA plant was 2500 m/min.

Each spinneret contained 96 holes, with a hole diameter of 0.25 mm and a hole length of 0.5 mm. After the application of the spin finish, the two yarns were combined inline, drawn over four pairs of heated godets, and wound onto an ASW602 winder from STC Spinnzwirn GmbH, Chemnitz, Germany (see Figure 2). Following the spinning process, the yarns were combined in a second step to form a 6144-filament yarn, resulting in a 6 k precursor.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the industrial yarn (IDY) plant of ITA.

Process Parameters and Procedure of the Upscaling Trials—IDY Plant at ITA

Table 6.

Extruder and spinneret temperatures of IDY trials.

Table 7.

Process parameters of the spinning pump and winder at the IDY plant.

Table 8.

Process parameters of godets at the IDY plant.

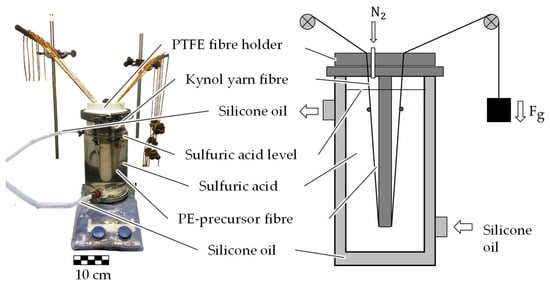

2.1.3. Discontinuous Sulfonation Trials

The two produced PE precursor fibres are investigated first in discontinuous sulfonation trials in 96%-concentrated sulfuric acid to investigate their sulfonation ability and the achievable sulfonation degree. The discontinuous sulfonation trials are conducted using a batch reactor, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Picture of double-walled glass reactor (left) and schematic construction of the reactor (right).

The reactor is a double-walled glass structure. The reaction temperature is adjusted by circulating heated silicone oil through the gap between the walls, which is supplied by a heating module. The reactor is filled with one litre of 96%-concentrated sulfuric acid. To keep the fibres in place during the reaction, they are held in the acid using a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) piece that guides and secures them. Kynol fibre, manufactured by Kynol Europa GmbH in Hamburg, Germany, is attached to both ends of the precursor fibre due to its superior chemical resistance. This ensures that the precursor fibre remains immersed in the acid without rupturing at the PTFE piece’s edges. Additionally, weights are attached to one end of the Kynol fibre to maintain constant tension on the precursor fibre. On one side, the Kynol fibre is fixed, while the weights can be attached on the other side. The discontinuous sulfonation trials are carried out under the conditions outlined in Table 9.

Table 9.

Reaction conditions for the discontinuous sulfonation trials of the PE-based-precursor fibres.

The reaction time is 4 h, with an applied tension of 1.7 MPa, while the temperature is maintained at 120 °C. At the end, the sulfonated PE fibres are extracted from the reactor by cutting the Kynol fibres and pulling out the PE fibre. These fibres are then wound onto a glass rod and allowed to cool for 10 min. Subsequently, they are immersed in a water bath for 10 min before being air-dried overnight at room temperature.

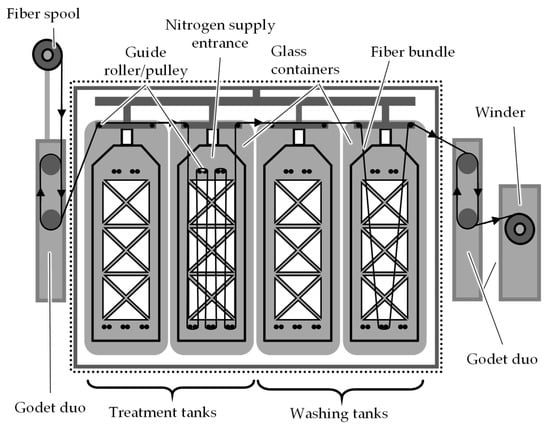

2.1.4. Continuous Sulfonation Trials

The continuous setup consists of four borosilicate tanks mounted on a mobile aluminium structure with an acrylic glass enclosure. Each tank is equipped with a rig mounted on its lid to guide the fibres through the tank. The tanks are connected to a lifting mechanism that allows the fibres and rig to be fully lifted out of the tanks. Two sets of godets are positioned at the entrance and exit of the pilot setup to facilitate the movement of fibres through the tanks. Finally, a winder is placed after the exit godet pair to wind the fibres onto a bobbin. During continuous sulfonation, only two of the tanks are utilised. The second tank is filled with approximately 20 L of 96%-concentrated sulfuric acid, while the fourth tank is filled with de-ionised water. After passing through the treatment tank, the fibre is washed into the water tank. Lastly, the fibre is guided through the final godet duo and wound onto a bobbin. The setup is illustrated in Figure 4. Throughout all zones of the continuous sulfonation process, the force on the fibre is manually measured immediately after the treatment tank and after the water tank. The tables below provide the parameters for the continuous sulfonation trials of the ITA precursor. Zones 1, 2, 3, and 4 correspond to the sulfonation zones. In the sulfonation zones, the pulling is force-controlled (Table 10).

Figure 4.

Schematic depiction of the continuous sulfonation set-up.

Table 10.

Parameters during the sulfonation of the ITA precursor at 120 °C (zones 1, 2, 3, and 4).

2.1.5. Discontinuous Carbonisation Trials

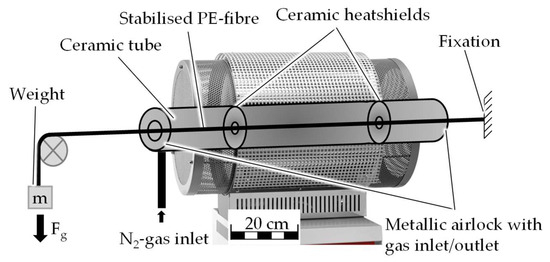

The sulfonated fibres are carbonised using a discontinuous set-up, as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Picture and schematic representation of the construction of the discontinuous carbonisation furnace.

The sulfonated fibre is secured on the right side of the furnace and guided through the furnace. After passing through a metal roll, a weight is attached to the fibre to apply a defined tension during the carbonisation process. The carbonisation is carried out in an inert atmosphere maintained by flowing N2 gas. The discontinuous carbonisation trials for the samples from batch sulfonation are carbonised to a maximum temperature of 1300 °C with an applied fibre tension of 1 MPa. All samples are subjected to a heating rate of 4 °C/min and maintained at the maximum carbonisation temperature for 5 min. The carbonisation samples are analysed using gas pycnometry, Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, light microscopy, and electron microscopy.

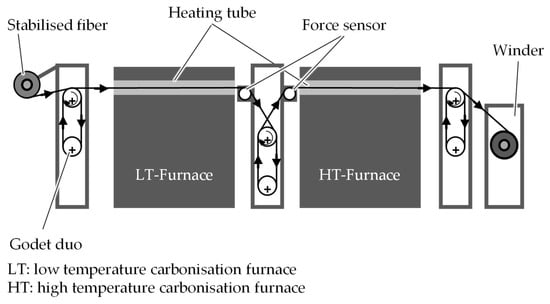

2.1.6. Continuous Carbonisation Trials

The continuous carbonisation trials for the fibres obtained from continuous stabilisation are conducted in a low-temperature (LT) and a high-temperature (HT) carbonisation furnaces which are operated sequentially. Both furnaces are equipped with five separate temperature zones and have a heating length of 2.25 m. The fibres are guided and pulled through the furnaces by two sets of godets and a winder. A schematic representation of the continuous carbonisation furnaces is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the construction of the continuous LT- and HT-carbonisation furnaces.

To create an inert atmosphere, the heating tubes of the LT- and HT-carbonisation furnaces are flooded with nitrogen. The gases released during the process are removed at both the entrance and exit of the furnaces.

The parameters for the continuous carbonisation trials of the sulfonated fibres are listed in Table 11 (LT) and Table 12 (HT).

Table 11.

Parameters for the continuous carbonisation in the LT furnace.

Table 12.

Parameters for the continuous carbonisation in the HT furnace.

2.2. Analytical Methods

2.2.1. Characterisation Methods for the Precursors

The 10,000-filament yarns were characterised using the FAVIMAT instrument, Textechno Herbert Stein GmbH & Co. KG, Mönchengladbach, Germany. For the yarns with 192 filaments, the methods listed in Table 13 were employed.

Table 13.

Analysis of fibre parameters.

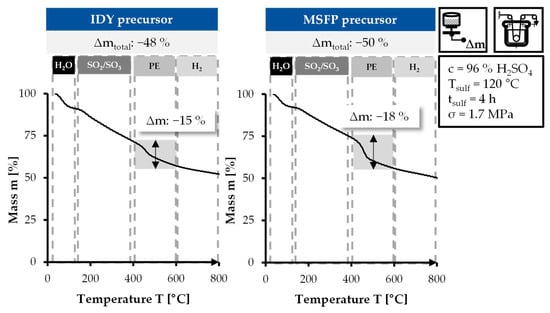

2.2.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

The TGA device used in this study is the STARe System TGA/DSC1 from Mettler Toledo GmbH, Gießen, Germany. The temperature range of TGA is usually between room temperature and 800 °C. The atmosphere is N2. The expected reactions in the thermogravimetric analysis of sulfonated PE-precursor fibres are outlined in Table 14.

Table 14.

Expected reactions in the thermogravimetric analysis of sulfonated PE [].

The percentage of non-cross-linked PE that gets decomposed at 400–600 °C should lower with a higher sulfonation degree. The sulfonic acid groups are hydrophilic and absorb water. These groups undergo decomposition between 120 °C and 400 °C, releasing SO2. Starting from 600 °C, dehydrogenation reactions occur, resulting in the release of H2 and the carbonisation of the fibres.

2.2.3. Light Microscopy

The used microscope is a Leica DM 4000 M from Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany. The microscope makes use of the LAS V4.12 software. To prepare the samples, the fibres are embedded in a resin and cross-sectional samples are cut out. The illumination allows for the observation of potential core–shell structures in the sulfonated fibres.

2.2.4. Electron Microscopy

The electron microscope makes use of scanning electron microscopy (SEM) technology. The model used is a Jeol JSM-6400 Scanning Electron Microscope from JEOL Ltd., Tokyo (Japan). SEM provides higher depth resolution compared to light microscopy, enabling clearer identification of pores or defects in the analysed PE-based carbon fibres.

2.2.5. Single-Filament Tensile Testing

The single-filament tensile test applies DIN EN ISO 1973:1995-12 [] to characterise the mechanical properties of the analysed fibre. Single filaments are separated and clamped in between two clips. The filaments are first put into vibration through sound waves. The vibration frequency of the filament is used to determine the fineness of the filament.

For the single-filament tensile test, the lower clip is pulled down and the needed force and the distance are measured. By plotting the force against the elongation, the maximum force and elongation at fibre break can be determined. The filament diameter and the resulting tensile stress distributed over the filament cross-section area, are obtained out of the frequency, tensile force, and density of the filament. The tensile modulus is calculated by division of the tensile stress with the elongation in the linear sector of the tensile stress-elongation diagram. Specifically, the region between 0.4% and 0.6% elongation is chosen for carbon fibres. For each fibre type, 25 single-filament measurements (n = 25) were conducted to ensure statistical reliability of the mechanical data.

2.3. Materials

The polymer employed in this study was the high-density polyethylene (HDPE) grade M200056 supplied by SABIC (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia). The same material was utilised for both the modified staple fibre pilot line and the IDY line at ITA. This grade was selected because it had previously demonstrated favourable processing behaviour and mechanical performance in filament yarn production. Since HDPE is not commonly employed in industrial continuous-filament processes, no commercially available grades are specifically designed for fibre production. The selection of a suitable HDPE for filament spinning is therefore challenging, as the polymer must meet demanding rheological and mechanical criteria, which typically requires extensive experimental evaluation.

The sulfuric acid used was 96%-concentrated technical sulfuric acid from the company Julius Hoesch GmbH & Co. KG, Düren, Germany.

3. Results

3.1. Results from 10 k Precursor Upscaling

By modifying a staple fibre plant (see Figure 1), it was possible to successfully produce a 10,000-filament PE precursor yarn in a single step. Samples were produced for an initial evaluation of the spinning technology and subsequent conversion into carbon fibres. The produced fibres are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Direct spun 10 k PE Precursor.

The winding duration was limited to a few minutes due to rapid bobbin growth, which quickly exceeded the winder’s capacity, and instability in the spinning process. Several challenges arose during the experimental trials:

3.2. Challenges During Upscaling

Achieving small filament diameter: The targeted filament diameter of approximately 10 µm could not be reached. Low throughput rates resulted in filament breaks at the spinneret due to excessive melt-drawing between the spinneret and the take-up. Melt breaks consistently occurred clustered at specific points on the spinneret, suggesting inhomogeneous pressure distribution within the spinneret pack, particularly at lower pressures caused by reduced throughput. Higher throughput rates required increased winding speeds to maintain the filament diameter, but speeds exceeding 150 m/min at the last godet were not achievable due to filament and yarn breaks during solid-state drawing. The maximum solid-state draw ratio achieved was 2.02.

Technical difficulties with winding high filament counts: The long path between Duo 6 and the winder, resulting from bypassing the crimp and cut unit typical of staple fibre production, complicated yarn guidance during winding. Due to the thick tow, the bobbin diameter grew rapidly, complicating the maintenance of uniform yarn tension. Yarn slipping occurred laterally off the bobbin even after achieving a stable winding process. To counteract slipping, fibre guide bars were positioned between Duo 6 and the winder, and discs were installed on the bobbin sides (see Figure 8). Additionally, winding speed was set 50 m/min lower than the last godet speed, significantly reducing yarn tension and enabling effective traversing during the winding period.

Figure 8.

Modified tube to prevent yarn slippage from the bobbin.

Melt-breaks and cooling challenges: Effective cooling of PE yarns with high filament counts proved challenging as gentle, homogeneous cooling had to be ensured. At low cooling airflow rates, central filaments were inadequately cooled, while higher airflow rates resulted in filament breakage near the airflow-exposed areas. Cooling air was applied at a pressure of 12.5 bar and a temperature of 32 °C. Covering one-third of the radial quench area with adhesive tape improved cooling and significantly reduced filament breakage.

Additional parameters varied to optimise spinning stability included extrusion and spinneret temperatures, ranging stepwise from 200 °C to 245 °C. Optimal extrusion was achieved at 245 °C, and this temperature was maintained at the spinneret for sample production.

The mechanical properties of the produced fibres were measured and compared with the requirements (see Table 15). A series of 25 single-filament tests was carried out to determine the mechanical data. On average, the sample exceeded the target tenacity of 20 cN/tex; however, due to the large standard deviation, not all individual filaments achieved this value. The high variability in tenacity and elongation confirms the previously described irregular extrusion behaviour, resulting in pronounced filament-to-filament inhomogeneity. The elongation at break also exceeded the limit of 100% on average, disqualifying the precursor as a suitable candidate for conversion into carbon fibre. However, the specified limits do not represent absolute exclusion criteria that would prevent conversion, but rather indicate thresholds beyond which the carbon fibre properties and conversion performance deteriorate significantly.

Table 15.

Mechanical properties of the produced 10 k PE precursor fibres.

The targeted single-filament diameter of approximately 10 µm was not achieved. The considerably higher filament diameters are detrimental to subsequent conversion steps, as they hinder uniform processing and stabilisation. In addition, the large diameter variations lead to differing diffusion paths into the fibre core, resulting in inhomogeneous sulphonation during the stabilisation stage.

Shrinkage tests could not be performed, as the available test equipment was unsuitable for thick yarns. The precursor from the modified staple fibre plant (MSFP) that was selected for conversion trials, characterised by minimal filament breakage, is listed in Table 15 and is designated as MSFP precursor.

3.3. Summary of Upscaling Spinning Results

The trials demonstrated that spinning a 10,000-filament PE precursor yarn is fundamentally feasible. Despite significant technical challenges, valuable insights were obtained for designing a new plant concept, and precursor yarns were successfully wound. However, key mechanical properties such as filament diameter were not achieved, highlighting the need for further optimisation in future trials.

3.4. Trial Results—ITA IDY Plant

The mechanical properties of the IDY precursor fibres were determined from a series of 25 single-filament tensile tests, as summarised in Table 16. Compared with the MSFP precursor, the IDY material exhibits a markedly higher tenacity of 38.42 ± 0.43 cN/tex, corresponding to an improvement of approximately 75% relative to the MSFP value (21.87 ± 3.81 cN/tex). The standard deviation amounts to only about 1.1% of the mean, indicating a highly uniform filament quality. This improvement is primarily attributed to the higher draw ratio achievable in the ITA melt-spinning process, which promotes enhanced molecular orientation and crystallite alignment.

Table 16.

Mechanical properties of the produced IDY PE precursor fibres.

The elongation at break was significantly reduced to 15.9 ± 0.8%, well below the specified upper limit of 100%, confirming the suitability of the IDY precursor for conversion into carbon fibre. The filament diameter of 9.43 ± 0.02 µm fully meets the target criterion of 10 µm, as a smaller diameter is advantageous. This fineness enables the formation of carbon fibres with diameters of approximately 7 µm, comparable to commercial PAN-based carbon fibres in dimension.

The shrinkage of 15.3 ± 1.2% is roughly 27% lower than that of the earlier Wortberg precursor (≈21%), confirming that the modified process conditions yield thermally more stable fibres. Compared with the PE precursor reported by Wortberg, which exhibited a tenacity of ≈22 cN/tex, a diameter of ≈9.8 µm, and an elongation of ≈49% [], the IDY precursor demonstrates superior mechanical performance across all key indicators, including significantly higher tenacity, lower elongation, reduced shrinkage, and excellent filament uniformity.

Collectively, these results show that the IDY precursor meets or exceeds all established criteria for successful conversion into carbon fibre. A small-scale upscaling trial, involving inline yarn doubling from two spinnerets, was also successfully conducted, confirming the technical feasibility of merging filaments within the existing pilot-scale equipment. However, a further increase in filament count within a single yarn cannot yet be implemented with the current system configuration. In total, eight spools were wound, each with a 10 min winding period. Precursor fibres were plied to create a 6144 (6 k) filament precursor yarn, as opposed to direct spinning of a 10,000 (10 k) filament precursor yarn. This precursor is designated as IDY precursor.

3.5. Conversion to PE-Based Carbon Fibres

Both PE precursors (MSFP and IDY) are investigated first in discontinuous sulfonation trials to investigate their sulfonation ability, the achievable sulfonation degree, to verify the previously determined criteria, especially regarding the filament diameter of the precursor, and to compare the resulting thermal properties of the sulfonated fibres. These are essential for ensuring effectiveness of the subsequent process step of carbonisation, as the highest possible thermal stability is targeted and a possibly low mass loss in the non-cross-linked PE decomposition temperature range (400–600 °C) is targeted. This guarantees the essential carbon yields in the produced PE-based carbon fibre [].

The TGA results shown in Figure 9 show the dependency of the sample mass loss from the temperature. In the case of the sulfonated IDY precursor, there is a total mass loss of 48%, and a lower 15% mass loss in the relevant 400–600 °C region. Importantly, a steep drop in the TGA curve in that temperature region is mostly avoided. When comparing the TGA curves of both sulfonated precursors, the IDY precursor achieves a higher sulfonation and cross-linking degree, which is one of the main factors for establishing suitability of PE precursors for carbon fibre production. In the case of the sulfonated MSFP precursor, there is a total mass loss of 50%, an 18% mass loss in the critical range of 400–600 °C, which is accompanied by a significant steep drop in the TGA curve in that region. This indicates insufficient sulfonation and cross-linking degree, which can lead to hollow or porous carbon fibres after carbonisation.

Figure 9.

TGA curves of sulfonated IDY precursor (left) and sulfonated MSFP precursor (right) from discontinuous sulfonation trials.

Comparison of the two curves should consider not only the relative mass loss but also the TGA curve profile in the region between 400 and 600 °C where non-cross-linked PE decomposes into volatile aliphatic and olefinic compounds. The IDY precursor exhibits a more favourable profile, with no pronounced drop in this range, whereas the MSFP precursor shows a steeper drop, indicative of incomplete sulfonation across the filament cross-section. This is likely attributed to the approximately 90% larger filament diameter of the MSFP precursor, which requires extended sulfonation due to the diffusion-limited nature of the sulfonation process.

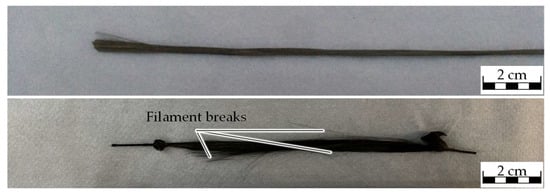

Discontinuous carbonisation in a tube furnace is carried out to verify the influence of the sulfonation and cross-linking degree on the carbonisation step. Both sulfonated precursors are put through discontinuous carbonisation at 1300 °C with an applied tensile stress of 1 MPa. The resulting PE-based carbon fibres are shown in Figure 10. The CF from the 10 k MSFP precursor shows clear filament breaks and a significant brittleness, which is a result of the lower sulfonation and cross-linking degree achieved during sulfonation. In contrast the CF produced out of the IDY precursor shows no apparent filament breaks and better handling and fibre characteristics.

Figure 10.

Picture from carbon fibre from discontinuous sulfonation and discontinuous carbonisation, using the IDY precursor (top) and the MSFP precursor (bottom).

Considering the results from the discontinuous sulfonation and carbonisation trials, the IDY precursor fibre shows the greatest potential for continuous sulfonation and carbonisation into a PE-based CF. The MSFP precursor seems to be limited in its convertibility to CF by failing to meet the requirement regarding filament diameter of the precursor. The excessive filament diameter of 18.1 ± 2.0 µm for the MSFP precursor, compared to 9.43 ± 0.02 µm for the IDY precursor, strongly limits the diffusion-limited process of sulfonation and therefore results in filament breaks and worse handling properties after carbonisation.

The first trials, transferring the gained insight from discontinuous sulfonation and carbonisation trials to the continuous technical scale, demonstrate the potential of PE-based CF production from the developed IDY precursor via the demonstrated route. After continuous sulfonation in four tension zones and continuous carbonisation divided into LT and HT carbonisation, PE-based CFs are produced with a filament diameter under 8.5 µm, tensile strength of up to 2.0 GPa, tensile modulus of up to 170 GPa with an elongation at break of up to 1.75%, when avoiding the creation of fibre surface defects.

4. Discussion

This study explored the upscaling of PE-based precursor fibres for carbon fibre production and presented a practical route to higher filament counts by (i) directly spinning a 10,000-filament yarn on a modified staple-fibre line and (ii) demonstrating inline merging on an industrial drawn yarn line. The results highlight both the potential and the current limitations of PE precursor upscaling. Most PE-CF studies have reported precursor filament counts ≤ 100 and relied on post-spinning consolidation. In contrast, the MSFP route in this work directly produced a 10 k tow, and the IDY route doubled the filament count inline.

Regarding precursor quality, the IDY precursor achieved a filament diameter of 9.43 ± 0.02 µm and a tenacity of 38.4 ± 0.4 cN/tex, with 15.9 ± 0.8% elongation and 15.3 ± 1.2% shrinkage (120 °C). These values (i) meet the convertibility targets established in the PE-CF literature (≈10 µm, >20 cN/tex, <100%, <30%) [] and (ii) exceed those of previous precursors (≈22 cN/tex, ≈9.8 µm, ≈49% elongation) []. By contrast, the MSFP 10 k precursor (18.1 ± 2.0 µm; 21.9 ± 3.8 cN/tex; 130.8 ± 40.8% elongation) did not meet convertibility requirements and produced brittle CF with filament breaks after discontinuous carbonisation.

Technical interpretation and process implications: The MSFP spinneret pack, designed for staple fibres, produced inhomogeneous extrusion at the low throughputs required for fine filaments, leading to clustered melt breaks and broad filament-to-filament variability. Cooling a high-filament-count PE bundle proved highly sensitivity-limited: increasing quench air promoted edge breaks, while insufficient quench produced under-cooled core filaments. TGA of discontinuously sulfonated precursors corroborated these effects: the IDY precursor showed a lower mass loss (15%) and no steep drop in 400–600 °C indicative of higher cross-linking, whereas the MSFP precursor exhibited an 18% loss with a pronounced drop, signalling incomplete cross-linking through the filament cross-section.

Although direct spinning of a 10,000-filament yarn was technically feasible, the resulting yarn lacked the uniformity and mechanical strength required for efficient sulfonation and carbonisation. The current plant configuration, therefore, remains unsuitable for producing high-quality precursors. Nevertheless, upscaling remains a crucial step towards industrial relevance—particularly since approximately 50% of CF production costs originate from precursor manufacturing. Transitioning from laboratory-scale filament counts to scalable melt-spinning processes is essential if PE-based CF is to achieve economic viability.

A promising intermediate solution was demonstrated by the IDY spinning trials conducted at ITA, in which the filament count was doubled inline by merging filaments from two spinnerets. This method achieved the mechanical requirements for precursor fibres—including a filament diameter of around 9–10 µm and tenacity exceeding 20 cN/tex—while also exhibiting superior sulfonation and carbonisation behaviour. The achieved tensile strength of up to 2.0 GPa, tensile modulus of up to 170 GPa with an elongation at break of up to 1.75%, is one of the highest reported in literature from continuous sulfonation and carbonisation. Those results are only surpassed through research experiments at more expensive higher carbonisation temperatures of 1800–2400 °C [,,,] or using considerably more expensive gel-spun UHMWPE precursors [,,].

Optimisation Priorities: A variety of subsystems influence the quality of PE-based precursor fibres. The results of this study clearly show, however, that the foremost priority is to achieve homogeneous extrusion of fine filaments at low throughputs. Only under these conditions can filament diameters comparable to those of commercial PAN-based carbon fibres be obtained—an essential prerequisite for establishing PE-based CF in cost-sensitive applications.

The first step towards this goal requires a fundamental redesign of the spinneret and pack assembly to ensure uniform pressure distribution and stable melt flow. Instead of immediately attempting to extrude 10,000 filaments, smaller spinneret configurations producing approximately 1000–2000 fine filaments should be employed initially. These yarns can then—as demonstrated in this study—be combined inline to form larger bundles. This stepwise approach substantially reduces the complexity of subsequent process stages such as cooling, drawing, and winding, while providing a stable basis for future scale-up. This inline merging approach aligns with early conceptual work described in [] and should be further pursued as a practical strategy for increasing filament counts without compromising quality. In the medium term, the direct production of a 6 k precursor should be pursued as an industrially relevant milestone, since this filament range corresponds to the entry level of commercial CF tows.

The second priority is the development of a controlled and homogeneous quenching system that is carefully matched to the spinneret layout and filament arrangement. Cooling exerts a decisive influence on molecular orientation and filament diameter uniformity. Uneven quenching conditions were identified as a root cause of melt breaks and cross-sectional inhomogeneities. Consequently, spinneret development and cooling concept design must proceed in parallel.

The third priority concerns high-speed drawing with uniform thermal input. Although the current godets, operating at up to 2500 m/min, provide sufficient drawing potential, a homogeneous temperature distribution across the entire yarn bundle is essential to obtain consistent molecular orientation. Future developments should therefore focus on optimised wrap angles, zoned temperature control, and improved heat transfer, ensuring uniform energy input at high titres without compromising filament diameter uniformity.

Finally, winding technology must be adapted to accommodate the large linear densities of high-filament-count yarns. Winders capable of handling up to 8500 dtex at 2500 m/min, with active tension control, edge guidance, and automatic doffing, are required for stable continuous operation.

This study underscores the challenge of increasing filament count without compromising fibre quality but also defines a clear route forward. The industrial realisation of PE-based CF depends on developing a melt-spinning process capable of producing fine, homogeneous filaments at low throughputs, supported by precise cooling, controlled drawing, and stable winding. A stepwise scaling strategy—starting with 1–2 k filaments and progressing through inline merging—offers a realistic and scalable approach that reduces complexity while leveraging existing high-speed infrastructure. Economically, inline filament merging eliminates slow post-spinning plying operations and enhances productivity. Together, these measures form a clear roadmap towards a scalable, cost-effective, and high-performance production process for polyethylene-based carbon fibres.

Author Contributions

J.L.: writing—original draft preparation, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, resources, visualisation. F.A.M.D.: writing—original draft preparation, methodology, validation, investigation, data curation, writing—review and editing, resources, visualisation. T.R.: conceptualisation, methodology, resources, validation, project administration, funding acquisition. R.M.: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition, project administration. T.G.: writing—review and editing, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding was provided and organised by Projekt DEAL.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study work is the result of a scientific collaboration between the Institut für Textiltechnik of RWTH Aachen University and the Saudi Aramco Technologies Company.

Conflicts of Interest

Tim Röding is employed by CarboScreen GmbH; Remi Mahfouz is employed by Saudi Aramco. This study was carried out as a joint research effort between ITA and Saudi Aramco within a carbon fibre project framework. All partners contributed to the development and analysis of the presented technology in accordance with the principles of good scientific practice. The authors confirm that the research and the preparation of this manuscript were performed independently and without any breach of scientific integrity. The authors declare that there are no commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| °C | Degrees Celsius |

| CF | Carbon fibre |

| DMF | Dimethylformamide |

| DMSO | Dimethylsulfoxide |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| GPa | Gigapascal |

| HDPE | High-density polyethylene |

| HT | High-temperature (furnace) |

| IDY | Industrial yarn |

| IR | Infrared |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| ITA | Institut für Textiltechnik |

| K/min | Kelvin per minute |

| LT | Low-temperature (furnace) |

| MPa | Megapascal |

| MSFP | Modified staple fibre plant |

| N | Newton |

| PAN | Polyacrylonitrile |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| rpm | Revolutions per minute |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| SO2 | Sulphur dioxide |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| µm | Micrometre |

References

- Eberle, C. Carbon Fiber Production from Textile Acrylics. In Proceedings of the Carbon Fibre Futures Conference, Geelong, Australia, 1–3 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, M. Market Report 2024—The Global Market for Carbon Fibers and Carbon Composites; Composites United e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P. Carbon Fibers and Their Composites; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Röding, T. Entwicklung Eines Mehrstufigen Carbonisierungsprofils Für Die Herstellung Von Polyethylenbasierten Carbonfasern; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Röding, T.; Langer, J.; Modenesi Barbosa, T.; Bouhrara, M.; Gries, T. A review of polyethylene-based carbon fiber manufacturing. Appl. Res. 2022, 1, e202100013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, E.; Osswald, T.A.; Rudolph, N. Plastics Handbook; Hanser: München, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ihata, I. Formation and reaction of polyenesulfonic acid. I. Reaction of polyethylene films with SO3. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1988, 26, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortberg, G. Development of Polyethylene-Based Precursors for Thermochemical Stabilisation for Carbon Fibre Production; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, B.; Hong, L.; Chen, P.; Zhu, B. Effect of sulfonation with concentrated sulfuric acid on the composition and carbonizability of LLDPE fibers. Polym. Bull. 2016, 73, 891–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Warren, J.; West, D.; Schexnayder, S. Global Carbon Fiber Composites Supply Chain Competitiveness Analysis; ORNL/SR-2016/100|NREL/TP-6A50-66071; Clean Energy Manufacturing Analysis Center: Golden, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, M.; Schüppel, D. Market Report 2023—The Global Market for Carbon Fibers and Carbon Composites; Composites United e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pichler, D. Implications of a Carbon Fiber Future: High Growth, Evolution, Maturation. Presented at Carbon Fiber, Charleston, SC, USA, 8–10 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, R.C. Comprehensive Polymer Science and Supplements; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Wallenberger, F.; Macchesney, J.; Ackler, H. Advanced Organic Fibers, Processes, Structures, Properties, Application; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, F.; Okabe, T. Comprehensive Composite Materials II; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chawla, K.K. Composite Materials—Science and Engineering, 4th ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greb, C.; Röding, T. Polyethylene-Based Low-cost Carbon Fibers Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Nonmetallic 2nd Symposium, Lyon, France, 17–18 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Leon y Leon, C.; O’Brien, R.A.; McHugh, J.J.; Dasarathy, H.; Schimpf, W.C. Polyethylene and Polypropylene a low cost carbon fiber (LCCF) precursors. In Advancing Affordable Materials Technology: 33rd International SAMPE Technical Conference, Washington, 5–8 November 2001; Falcone, A., Ed.; SAMPE International Business Office: Covina, CA, USA, 2001; pp. 1289–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, D.; Jang, D.; Joh, H.I.; Reichmanis, E.; Lee, S. High Performance Graphitic Carbon from Waste Polyethylene: Thermal Oxidation as a Stabilization Pathway Revisited. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 9518–9527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Carbon fibers from oriented polyethylene precursors. J. Thermoplast. Compos. 1993, 6, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postema, A.R.; De Groot, H.; Pennings, A.J. Amorphous carbon fibres from linear low density polyethylene. J. Mater. Sci. 1990, 25, 4216–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Sun, Q.J. Structure and properties development during the conversion of polyethylene precursors to carbon fibers. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1996, 62, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Palmenaer, A. Ermittlung der Prozessparameter zur kontinuierlichen Herstellung von Polyolefin-Basierten Carbonfasern; Shaker: Aachen, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Lee, J.S. Preparation of carbon fibers from linear low density polyethylene. Carbon 2015, 94, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marter Diniz, F.A.; Röding, T.; Bouhrara, M.; Gries, T. The Production of Ultra-Thin Polyethylene-Based Carbon Fibers out of an “Islands-in-the-Sea” (INS)-Precursor. Fibers 2023, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eun, J.H.; Lee, J.S. Study on polyethylene-based carbon fibers obtained by sulfonation under hydrostatic pressure. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 18028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.-H.; Kim, K.-W.; Kim, B.-J. Carbon Fibers from High-Density Polyethylene Using a Hybrid Cross-Linking Technique. Polymers 2021, 13, 2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, E.; Muks, E.; Ota, A.; Herrmann, T.; Hunger, M.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Structure Evolution in Polyethylene-Derived Carbon Fiber Using a Combined Electron Beam-Stabilization-Sulphurization Approach. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Yoo, S.H.; Lee, S. Safer and more effective route for polyethylene-derived carbon fiber fabrication using electron beam irradiation. Carbon 2019, 146, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Luo, G.; Gao, J.; Li, W.; Han, N.; Zhang, X. Fabrication of liner low-density polyvinyl-based carbon fibers via ultraviolet irradiation-vulcanization crosslinking. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2023, 301, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Li, W.; Han, N.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Fabrication of UV crosslinked polyethylene fiber for carbon fiber precursors. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 14820–14832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Kim, C.B. Small-Molecule Additive for Improving Polyethylene-Derived Carbon Fiber Fabrication. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 1510–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, B.E.; Behr, M.J.; Patton, J.T.; Hukkanen, E.J.; Landes, B.G.; Wang, W.; Horstman, N.; Rix, J.E.; Keane, D.; Weigand, S.; et al. High-modulus low-cost carbon fibers from polyethylene enabled by boron catalyzed graphitization. Small 2017, 13, 1701926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lommerts, B.J.; Lemstra, P.J. Polyethylene vc. para-aramid fibers. Chem. Fibers Int. 2021, 4, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Penning, J.P.; Lagcher, R.; Pennings, A.J. The effect of diameter on the mechanical properties of amorphous carbon fibres from linear low density polyethylene. Polym. Bull. 1991, 25, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, L.H.; Knight, G.W.; The Dow Chemical Company. Fine Denier Fibers of Olefin Polymers. U.S. Patent 4,909,975, 20 March 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Krupp, S.P.; Bieser, J.O.; Knickerbocker, E.N.; The Dow Chemical Company. Method of Improving Melt Spinning of Linear Ethylene Polymers. U.S. Patent 5,254,299, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Spalding, M.; Wang, W.; Pavlicek, C.; The Dow Chemical Company. Small Diameter Polyolefin Fibers. EP3011087B1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sumitomo Chemical Co Ltd. Process for Production of Carbon Fiber and Precursor. GB1458571A, 15 December 1976.

- Horikiri, S.; Iseki, J.; Minobe, M.; Sumitomo Chemical Co, Ltd. Process for Production of Carbon Fiber. U.S. Patent 05/438,704, 24 January 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, M.J.; Landes, B.G.; Barton, B.E.; Bernius, M.T.; Billovits, D.F.; Hukkanen, E.J.; Patton, J.T.; Wang, W.; Wood, W.; Keane, D.T.; et al. Structure-property model for polyethylene-derived carbon fiber. Carbon 2016, 107, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIN EN ISO 2060:1995-04; Textilien—Garne von Aufmachungseinheiten—Bestimmung der Feinheit (Masse je Längeneinheit) durch Strangverfahren (ISO 2060:1994). DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1995.

- DIN EN ISO 2062:2010-04; Textilien—Garne von Aufmachungseinheiten—Bestimmung der Höchstzugkraft und Höchstzugkraftdehnung von Garnabschnitten unter Verwendung eines Prüfgeräts mit Konstanter Verformungsgeschwindigkeit (CRE) (ISO 2062:2009). DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2010.

- DIN EN ISO 14621:2006-03; Textilien—Multifilamentgarne—Prüfverfahren für Texturierte und Nicht Texturierte Multifilamentgarne; Deutsche Fassung EN 14621:2005. DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2006.

- DIN EN ISO 1973:1995-12; Textilien—Fasern—Bestimmung der Feinheit—Gravimetrisches Verfahren und Schwingungsverfahren (ISO 1973:1995). DIN Media GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 1995.

- Zhang, D.; Bhat, G.S. Carbon fibers from polyethylene-based precursors. Mater. Manuf. Process 1994, 9, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).