Abstract

The growing adoption of laminated fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) composites in aerospace, automotive, and civil engineering demands advanced design methodologies capable of navigating their complex anisotropic behavior. While traditional design approaches rely heavily on iterative simulations and classical optimization, recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) offer a transformative alternative. This review systematically examines the expanding role of AI in composite design and optimization—highlighting a critical transition from physics-based modeling to data-driven, intelligent frameworks. This paper emphasizes emerging AI paradigms not yet widely covered in the composite literature, including Explainable AI (XAI) for interpretable decision-making and Large Language Models (LLMs) for automating design synthesis and knowledge retrieval. Key findings demonstrate AI’s capacity to efficiently optimize stacking sequences, ply orientations, and manufacturing parameters while satisfying multi-objective constraints such as weight, stiffness, and damage tolerance. Furthermore, we explore AI’s integration across the composite lifecycle—from surrogate-assisted finite element analysis and uncertainty-aware design allowables to in-service structural health monitoring. By bridging the gap between computational intelligence and industrial practicability, this review underscores AI’s potential not as a supplementary tool, but as a foundational technology poised to redefine next-generation composite engineering.

1. Introduction

Laminated Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) composites have become the material of choice for high-performance applications in aerospace, automotive, wind energy, and civil infrastructure due to their exceptional specific strength and stiffness, superior fatigue resistance, and tailorable anisotropic properties [,,]. The design of these materials, however, presents a formidable challenge. The vast design space, encompassing an almost infinite combination of ply orientations, stacking sequences, material selections, and geometric parameters, interacts in highly non-linear ways to determine the final structural performance. Traditional design paradigms, heavily reliant on iterative Finite Element Analysis (FEA) and classical optimization techniques, often prove computationally prohibitive and can easily converge on sub-optimal local minima, failing to exploit the full potential of composite materials.

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) has inaugurated a new era in composite design. These data-driven approaches offer a paradigm shift from purely physics-based simulation to hybrid models that learn from data to predict complex behaviors with remarkable speed and accuracy. The development of advanced machine learning models in the design of laminated FRP composites has opened new avenues for optimizing components like vibration energy harvester beams []. AI techniques can navigate the complex, multi-dimensional design space more efficiently than traditional methods, identifying non-intuitive optimal configurations that satisfy multiple, often competing, objectives such as minimizing weight while maximizing stiffness, strength, and damage tolerance [].

The necessity for a comprehensive understanding of AI in laminated FRP optimization stems from a critical juncture in engineering. The escalating performance demands in aerospace, automotive, and renewable energy sectors are pushing traditional design methods, reliant on iterative simulations and engineering intuition, to their computational and practical limits. These classical approaches often fail to exploit the full, complex anisotropic potential of composites, leading to conservatively designed and sub-optimal structures. This review is therefore urgently needed to synthesize and critically evaluate the emerging AI toolkit that can overcome these barriers, enabling the rapid discovery of high-performance, lightweight, and reliably manufacturable designs that are otherwise inaccessible, thereby accelerating innovation and the adoption of next-generation composite solutions.

This review paper aims to provide a systematic and exhaustive examination of the role of AI in the design and optimization of laminated FRP composites. It is structured to guide the reader from fundamental AI methodologies to advanced, specialized applications. The paper will first explore the cornerstone of AI in composites: the use of surrogate models, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), and their mixture with evolutionary algorithms like Genetic Algorithms (GAs) for global optimization. It will then delve into the critical need for transparency through Explainable AI (XAI), which reveals the “black box” nature of complex models. A key focus is placed on the emergent role of Large Language Models (LLMs) in automating process planning, facilitating cross-disciplinary knowledge integration, and interpreting multimodal data, thereby introducing a new layer of intelligence to the design workflow. Subsequent sections will address the application of AI in handling real-world uncertainties and establishing statistical design allowable limits, its transformative impact on manufacturing processes including additive manufacturing and automated fiber placement, and its growing role in the in-service phase through structural health monitoring and fault assessment. By synthesizing findings from a wide body of recent literature (2015–2025), this review seeks to delineate the current state of the art, highlight persistent challenges, and outline promising future research directions, ultimately underscoring AI’s role as an indispensable enabler for the next generation of high-performance composite structures.

The scope of this review is deliberately focused on laminated FRP composites and a select set of AI paradigms due to their distinct significance in the field. Laminated FRPs represent the most prevalent form of advanced composites in high-performance structures, and their design, characterized by a high-dimensional, discrete optimization problem of stacking sequences and ply orientations, proposes a quintessential challenge that AI is uniquely suited to address. Consequently, the AI models examined, including surrogate models like ANN-GA for global optimization, XAI for interpretable decision-making, and emerging LLMs for knowledge integration, were selected as they represent the most impactful and trending computational intelligence frameworks specifically capable of navigating this complex, anisotropic design space and streamlining the associated engineering workflows.

2. Foundational AI Methodologies: Surrogate Modeling and Evolutionary Optimization

The most prevalent and successful application of AI in composite design lies in the creation of surrogate models, also known as metamodels, which serve as fast-to-evaluate approximations of computationally expensive physics-based simulations like FEA. Among these, ANNs have emerged as a particularly powerful tool due to their ability to learn complex, non-linear relationships from data. Table 1 shows the core ai methodologies for composite design and optimization that will be discussed in this section.

2.1. Artificial Neural Networks as Predictive Surrogates

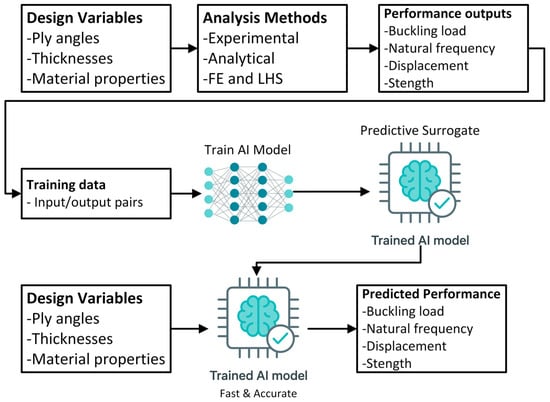

ANNs are leveraged to map the relationship between design variables (e.g., ply angles, thicknesses, material properties) and performance outputs (e.g., buckling load, natural frequency, displacement, strength). The process typically involves generating a comprehensive dataset through techniques like FEA and Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS), which ensures a well-distributed sampling of the design space [,,]. This dataset is then used to train the ANN, effectively teaching it the underlying physics without explicitly programming the governing equations.

The efficacy of this approach is well-documented. For instance, Liu et al. demonstrated that by employing ANN-based surrogate models, researchers can predict vibration, bending, and buckling behaviors, buckling loads without the need for exhaustive iterative processes, thereby expediting the optimization of stacking sequences and structural dimensions [,,]. This method mitigates the burden of dimensionality by utilizing lamination parameters, streamlining the input data required for the ANN models. The integration of these advanced AI techniques within a GA framework not only minimizes the weight of composite laminates but also opens new avenues for cost-effective, high-performance design solutions. The precision achievable with ANNs is exemplified in the work of Sahibab & Kovács, where a multilayer feedforward neural network achieved an impressive coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.99) and a low Mean Square Error (MSE = 1.3 × 10−5) in modeling composite sandwich structures for high-speed train floors []. The correlation between FEA modeling and optimization results, with a deviation of about 8.9%, demonstrates the robustness of this ANN approach in real-world applications [].

Beyond standard ANNs, more sophisticated architectures are being deployed. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), renowned for their prowess in image recognition, have been adapted for composite design. To address this, a CNN-based model for predicting buckling instability in sheet metal panels was developed, which offers a promising avenue for laminated FRP composites []. By leveraging the ability of CNNs to identify geometric features that influence buckling, these models facilitate the optimization of panel shapes, thus potentially reducing the need for costly redesigns. The high accuracy achieved by such models, exemplified by a 90.1% success rate in predicting buckling severity, underscores their practical utility in real-world engineering applications []. For larger-scale structural analysis, the Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) neural network architecture has been shown to significantly enhance computational efficiency. This approach leverages FEA data to accurately predict laminate deflections and stresses, thus facilitating more precise design and engineering assessments []. As such, the MoE model provides a robust tool for optimizing laminate parameters, offering significant improvements over traditional linear and non-linear FEA methods. Figure 1 visualizes the role of ANNs as Predictive Surrogates in composite structure design. The central flow illustrates the training process: Design Variables are used to generate a comprehensive dataset via FEA and LHS, which then trains the multi-layered ANN. The trained network then efficiently maps the inputs to Performance Outputs (e.g., buckling load, natural frequency and strength). Furthermore, the figure highlights the adoption of advanced architecture, specifically showing the application of a CNN for buckling prediction and the enhanced computational efficiency offered by the MoE network for predicting laminate deflections and stresses.

Figure 1.

Artificial Neural Networks as Predictive Surrogates.

2.2. Hybrid AI Models for Enhanced Optimization

While ANNs provide rapid performance predictions, they are often coupled with optimization algorithms to navigate the design space effectively. Here, GAs and other meta-heuristics have proven to be exceptionally synergistic. GAs, inspired by natural selection, are well-suited for handling discrete variables like ply angles and can effectively avoid local minima, making them ideal for the combinatorial problem of stacking sequence optimization.

The integration of ANN and GA has emerged as a powerful approach to optimizing laminated composite structures, significantly reducing computational costs and enhancing design efficiency []. This synergy allows for the multi-objective optimization of composite structures, particularly in minimizing weight and cost for applications such as high-speed train floor panels []. This method employs classical lamination theories alongside Monte Carlo simulations to generate comprehensive design data, which is crucial for predicting safety factors and optimizing structural parameters. Similarly, this integrated approach was showcased for the design optimization of smart laminated composites for harvesting energy []. By integrating ANNs with GA, engineers can enhance the performance of these beams through precise design optimizations that maximize displacement while reducing natural frequency. This approach employs FEA to perform detailed parametric studies, leading to the creation of surrogate models that facilitate efficient design exploration.

The hybrid approach extends beyond ANN-GA. Other hybrid models have been developed to address specific challenges. For predicting the critical buckling load of structural members, considering the influence of initial geometric imperfections, Ly et al. utilized techniques such as the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS) optimized through metaheuristic methods like simulated annealing and biogeography-based optimization []. The enhanced prediction accuracy achieved through these hybrid AI models, as evidenced by improvements in correlation coefficients and reduction in errors, showcases their potential in refining design processes for more reliable and efficient composite structures. Furthermore, leveraging hybrid AI models, such as ANFIS-GA and ANFIS-PSO, can significantly enhance the design of laminated FRP composites by offering precise predictions of buckling loads []. These models, validated through rigorous quality assessment criteria like R2 and RMSE, outperform traditional methods by accurately simulating real-world stress conditions. The integration of genetic algorithms and particle swarm optimization within these systems not only refines the prediction accuracy but also improves the adaptability of composites to varying operational demands []. In addition to these advancements, the exploration of hybrid machine learning models like PSO-ANN further illustrates the enhancement of predictive capabilities in composite designs []. By integrating particle swarm optimization with artificial neural networks, these models adeptly predict buckling damage in structural members, showcasing improved accuracy through performance metrics such as RMSE and MAE [].

Another critical performance metric is the fatigue life prediction where Mirzaei et al. integrated an ANN model with a non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm (NSGA-II) []. This hybrid model capitalizes on experimental data from carbon/epoxy composites, addressing various stress concentration geometries and stacking sequences to improve predictive accuracy. The R2 scores of 88% and 90% for test and validation datasets underscore the model’s robustness, surpassing conventional machine learning techniques such as decision trees and gradient boosting. This enhanced predictive capability facilitates more precise laminate design, ensuring that performance metrics like fatigue life can be met with greater confidence []. The application of a Genetic Algorithm-Backpropagation Neural Network (GA-BPNN) model has demonstrated significant potential in optimizing the impact resistance of fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) hybrid laminates, specifically within the yacht industry []. This model leverages experimental tests and finite element simulations, coupled with C-scan imaging, to effectively evaluate and predict damage from low-velocity impacts, highlighting the model’s efficacy in enhancing the durability and performance of FRP laminates.

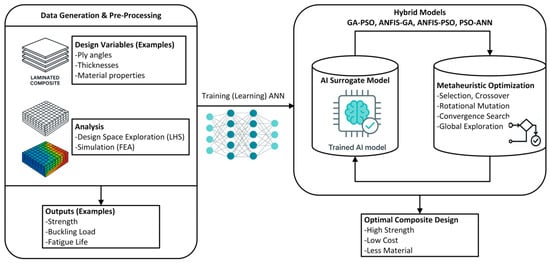

Figure 2 outlines the process of leveraging an ANN for composite design optimization. The workflow begins with Data Generation, where design variables and corresponding performance outputs are paired to create training data. This data is fed into the multi-layered ANN, which undergoes training to learn the underlying complex relationships. The resulting Trained ANN Model acts as a surrogate, providing instantaneous, fast, and accurate performance predictions, dramatically reducing the computational time from hours or days (typical for traditional FEA) down to mere seconds.

Figure 2.

Hybrid Enhanced AI Models for Enhanced Optimization.

ANN–GA hybrid methods, while powerful, have several important limitations: the ANN surrogate is prone to overfitting when training data are limited, noisy, or not representative of the full design space, so the model can appear accurate on the training set but generalize poorly during the GA search; the overall computational cost is often high because expensive simulations are needed to generate training data, the network itself must be trained and tuned, and the GA may require many generations and large populations to converge; performance is highly sensitive to hyperparameters on both sides (network architecture, learning rate, regularization, population size, mutation and crossover rates), so poor choices can cause instability or premature convergence; predictions become unreliable when the GA explores regions where the ANN is extrapolating beyond its training range; and, finally, the hybrid behaves largely as a black box with sometimes ad hoc constraint handling, which reduces interpretability and can make it harder to enforce practical design rules and gain engineering confidence in the “optimal” solution [,,,].

Compared with traditional optimization in which a GA is directly coupled to full FEA, AI-based approaches such as ANN–GA can deliver similar optima at a much lower computational cost. GA–FEM optimization of an in-plane loaded laminated plate required 264.7 h, whereas the corresponding GA–ANN procedure with the same design space took 112.9 h—a 57% reduction—with negligible differences in fitness and laminate weight []. Similar savings of about 51% were obtained for a non-linear shallow shell problem. Additionally, embedding an ANN surrogate in a GA reduces the cost of each buckling evaluation from 10.57 s for a full FE run to roughly 10−4 s for an ANN prediction (only 0.0009% of the FE cost) []. This led to time savings of about 44 h per optimization for flat laminates and 185–258 h per run for stiffened laminates, while keeping mean absolute percentage errors in buckling response within about 3–4% of the high-fidelity solution.

Table 1.

Core AI Methodologies for Composite Design and Optimization.

Table 1.

Core AI Methodologies for Composite Design and Optimization.

| Methodology Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Function in Composite Design | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surrogate Modeling & Global Optimization [,,] | ANN-GA, ANN-PSO, PSO-ANN | Replaces costly FEA simulations; finds global optimum for stacking sequences, dimensions. | Drastic reduction in computational cost; effective for high-dimensional, non-linear problems. |

| Hybrid & Advanced Predictive Models [,] | ANFIS-GA, ANFIS-PSO, ANN-NSGA-II | Predicts complex behaviors like buckling and fatigue life, accounting for imperfections. | High accuracy (high R2, low RMSE); handles uncertainty and multi-objective optimization. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) [,,] | SHAP, Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs), Counterfactual Analysis | Interprets “black-box” models; identifies critical design parameters and their influence. | Builds engineer trust; enables informed design adjustments; supports certification. |

| Uncertainty & Design Allowables [,,,,] | XGBoost, Random Forests, Gaussian Processes | Predicts statistical distribution of properties (e.g., notched strength) for reliable design. Fire-retardant behavior | Establishes statistical design allowables computationally; manages material/process variability. |

| Large Language Models (LLMs) [,,] | GPT-4 with LangChain, MechGPT, CompCap for MLLMs | Automates process planning; integrates cross-disciplinary knowledge; interprets multimodal data. | Automates workflows; enhances knowledge retrieval and synthesis; bridges design and documentation. |

3. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Composite Design

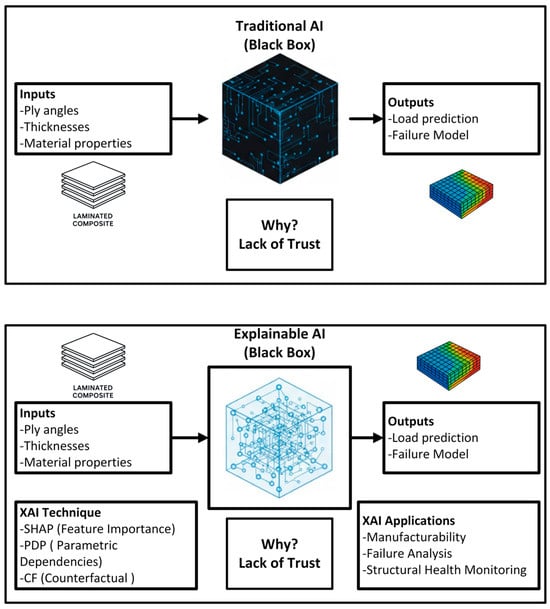

As AI models, particularly deep learning networks, have grown in complexity, they have often been treated as “black boxes,” providing accurate predictions but little insight into the underlying reasoning. This lack of transparency is a significant barrier to adoption in engineering fields, where understanding the “why” behind a design recommendation is crucial for validation, certification, and engineer trust. XAI has thus emerged as a critical subfield aimed at making AI decisions interpretable to humans.

In the context of laminated FRP composites, XAI provides invaluable insights into the influence of specific design variables on the final performance. By employing SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs), engineers can examine the input–output relationships within machine learning models, which is crucial for adjusting design parameters to achieve target mechanical properties []. In practical terms, SHAP-based feature importance rankings can show which ply angles, thicknesses, or material properties dominate responses such as buckling load, stiffness, or damage index [], guiding where to tighten quality-control tolerances, add safety factors, or prioritize additional testing. PDPs then complement this by revealing whether these effects are approximately linear, strongly non-linear, or threshold-like, thereby indicating whether simple design rules are sufficient or whether re-optimization is required within a narrower, code-compliant design window. This methodology not only enhances the transparency of AI models but also facilitates the identification of critical design elements, such as stacking sequences and ply orientations, that directly influence the strength and stability of the composites.

This approach is transformative for refining specific composite behaviors, as XAI has been incorporated to understand the static characteristics of bistable composites []. By utilizing SHAP, researchers can elucidate the influence of material properties, geometric dimensions, and environmental conditions on the curvatures and snap-through force of bistable laminates. This provides clarity on the roles of transverse thermal expansion coefficients and moisture variation, while integrating seamlessly with advanced AI methods such as eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) for validation []. Such insights are crucial for optimizing laminate design, allowing engineers to anticipate how changes in material selection or geometry will shift the operating range and to predict and mitigate potential failure modes more effectively.

Moreover, the use of counterfactual (CF) techniques within the XAI framework allows for the precise tailoring of composite configurations that meet performance requirements while maintaining manufacturability and cost-effectiveness []. CF explanations can suggest minimal changes to ply angles, stacking sequence, or material grade to move from a borderline design to one that satisfies target safety margins, thereby linking model explanations directly to actionable design modifications. Hence, the XAI framework is a transformative tool, bridging the gap between traditional design approaches and modern AI-driven optimization. In parallel, leveraging ensemble learning models in the design of laminated FRP composites presents a promising avenue for enhancing mechanical property predictions []. The inclusion of SHAP and individual conditional expectation plots further enriches this approach by providing transparent insights into how input parameters, such as unconfined compressive strength or fiber volume fraction, impact model outputs. This transparency is crucial for engineers aiming to refine stacking sequence, ply angles, and other laminate parameters to meet stringent performance targets.

The application of XAI also extends beyond the design phase into structural health monitoring (SHM). For example, Azad and Kim developed an explainable artificial intelligence-based approach for reliable damage detection in polymer composite structures using deep learning [,]. Utilizing an explainable vision transformer (X-ViT), this approach leverages deep learning while enhancing transparency and reliability of damage assessment through a patch-attention mechanism that highlights critical regions. This not only facilitates improved repair planning but also bolsters the operational performance of composite structures by supporting timely and accurate interventions. The emerging role of XAI in the classification and monitoring of composite structures is further enhanced through techniques such as LIME and Grad-CAM, which provide valuable insight into the decision-making processes of deep learning models []. These methods significantly improve the transparency and interpretability of CNNs, making them particularly beneficial in quality control and SHM applications, where engineers must justify inspection thresholds and maintenance actions.

Figure 3 contrasts traditional “black-box” AI with explainable AI (XAI). In black-box models, inputs such as ply angles, thicknesses, and materials yield outputs such as buckling load or failure index, but engineers cannot see why the model made that prediction, leading to low trust and limited acceptance in certification workflows. XAI, depicted as a transparent box, uses tools like SHAP, PDPs, and counterfactuals to reveal which parameters drive predictions and how changes in these variables shift structural response. These interpretable insights support decisions on manufacturability, quality control, SHM, failure analysis, and the setting of conservative design margins, thereby moving toward more transparent and trustworthy AI in composites design and assessment.

Figure 3.

Applications for Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Composite Design.

Despite this promise, integrating XAI into formal certification frameworks remains challenging. Regulators typically require stable, reproducible evidence chains, whereas XAI explanations can be sensitive to data shifts, retraining, or the choice of background samples, and there is still no consensus on standardized XAI metrics or reporting formats. Consequently, in current practice XAI is best used as a supporting layer—improving traceability, documenting model behavior, and guiding engineering judgment—while final approval still relies on physics-based checks, code provisions, and conservative safety factors rather than explanations alone.

4. Large Language Models

LLMs build on these advances by shifting the focus from predicting numerical responses to coordinating information, tools, and decisions in a language-centric way. Whereas XAI methods primarily explain the behavior of specific predictive models, LLMs can act as high-level controllers that reason over design documents, simulation outputs, manufacturing constraints, and code, and then call specialized tools when needed. In the context of laminated FRP composites, this opens new possibilities for automating engineering process planning, integrating cross-disciplinary knowledge, and interpreting multimodal data. For example, models implemented using frameworks such as LangChain with OpenAI’s GPT-4 can use deterministic tools that encode process-planning knowledge to construct multi-step solutions for tasks like cycle time estimation and resource allocation, thereby streamlining the design process and improving the manufacturability of composite structures [].

LLMs also exhibit a compositional ability for decomposing complex design tasks. They can tackle intricate problems by integrating simpler sub-tasks, which is pivotal for optimization []. However, their performance is less reliable with complex multi-step reasoning, necessitating a strategic application where task complexity matches the model’s strengths to manage design parameters effectively. The utility of LLMs expands with multimodal capabilities. The integration of Composite Captions (CompCap) enhances Multimodal Large Language Models (MLLMs) by improving their understanding of composite images, addressing a gap in training data for synthetic visuals []. This allows engineers to visually assess and fine-tune structural properties with greater precision, facilitating the development of configurations that meet industry standards.

The transformative potential of LLMs lies in cross-disciplinary knowledge integration. Strategies like MechGPT leverage LLMs to facilitate hypothesis generation and knowledge retrieval for complex processes like failure mechanics and structural modeling []. Through Ontological Knowledge Graphs, this approach extracts structural insights to support robust laminate configurations. Similarly, transformer-based composite language models that amalgamate multiple individual models can refine the evaluation of design specifications and detect inconsistencies, ensuring reliability []. The integration of composite speech-language models, such as ComSL, further enhances this by enabling cross-modality learning to process complex design specifications efficiently, improving data efficiency crucial for managing extensive datasets [].

To overcome the limitations of static models, architectures like Composite Learning Units (CLUs) transform LLMs into adaptive learners capable of continuous learning []. By maintaining a dynamic knowledge repository, CLUs enhance reasoning for complex design tasks, allowing for the autonomous refinement of design parameters such as stacking sequences and ply angles to meet specific performance targets.

Several case studies on LLM assistant for composite materials were introduced by Kapoor et al. []. The authors built a domain-specific assistant on top of GPT-4 using retrieval-augmented generation and a curated composites database (~2 MB of txt files: research articles, magazines, contact info for experts and companies, etc.). They then ran a user study with 5 composites researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s Manufacturing Demonstration Facility (MDF). Each participant evaluated 6 prompts (ranging from beginner questions to expert-level design queries). For every prompt, they saw two anonymous answers: one from the Composites Guide and one from standard GPT-4o, and selected which they preferred. On a 1–5 correctness/quality scale, GPT-4o averaged 3.23, while the Composites Guide averaged 4.0 for composites Q&A. Qualitative feedback indicated GPT-4o tended to provide good general overviews, whereas the Composites Guide more often supplied richer, composites-specific details, definitions, and practical options (e.g., multiple fabrication routes), which experts judged more helpful for real design decisions. It was reported that LLMs can produce plausible sounding but incorrect information. In case of safety-related inquiries, it is important to include human experts to review the recommendations [].

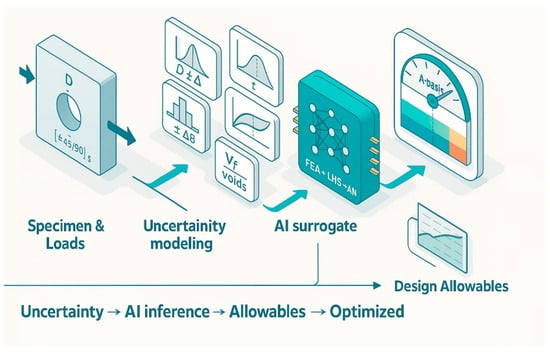

5. Managing Uncertainty and Establishing Design Allowable Limits with AI

The performance of composite structures is inherently variable due to uncertainties in material properties, manufacturing imperfections, and environmental conditions. Traditional design accounts for this through “design allowable limits” that refers to conservative lower-bound property values (e.g., strength, stiffness, fatigue life) that the material is expected to exceed for the vast majority of parts in service, often defined so that at least 90–99% of the population will be stronger than the published value with a specified confidence level. The process of establishing these allowable limits through testing is often time-consuming and expensive. AI offers a powerful, simulation-driven alternative to augment and accelerate this process. The transformative impact of AI on the composite design paradigm is crystallized in Table 2, which provides a synthesized comparison of key aspects between traditional and AI-driven methodologies.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of AI vs. Traditional Methods.

Integrating design allowable limits into the AI-driven optimization of FRP composites is essential for ensuring structural integrity and compliance with certification standards []. By incorporating statistical definitions and methodologies from the Composite Material Handbook (CMH-17), AI models can be calibrated to predict laminate properties with higher accuracy, taking into account variations in manufacturing processes and material characteristics []. This approach is particularly crucial when evaluating notched and unnotched allowable limits, as it provides a robust framework for assessing the impact of structural modifications and environmental conditions on composite performance. Compared with conventional statistical procedures prescribed in aerospace standards such as CMH-17 and relevant ASTM methods, which typically fit simple distributions (e.g., normal, lognormal, Weibull) to coupon test data and then derive A- or B-basis values, AI models offer a more flexible way to capture multi-parameter interactions (fiber volume fraction, cure cycle, layup, environmental conditions) in a single surrogate.

Machine learning is particularly adept at this statistical task. Furtado et al. demonstrated this by employing algorithms such as XGBoost, Random Forests, and Gaussian Processes to predict notched strength and its statistical distribution with remarkable precision, accommodating variability in material and geometric properties []. This predictive capability is crucial for optimizing the design of Legacy Quad Laminates and double-double laminates, where low generalization errors enhance confidence in the anticipated performance. Additionally, the use of Gaussian Processes with smaller datasets and Artificial Neural Networks with larger ones underscores the adaptability of these techniques to varying data conditions, ensuring efficient resource utilization. Ultimately, these advancements in machine learning not only expedite the computational process but also contribute to a more streamlined approach in achieving reliable design allowable limits, thereby supporting safer and more efficient composite structure designs.

The integration of explainable machine learning (XML) within finite element modeling (FEM) offers a novel approach to address uncertainty in the design of laminated FRP composites, particularly in extreme environments []. By leveraging XML, engineers can predict stress and strain responses with greater precision, even when subjected to variability in mechanical and thermal properties, as demonstrated in carbon-carbon composites for solar receivers. This methodology strengthens the predictive framework by incorporating a synthetic dataset from extensive simulations, thus enabling more reliable performance evaluations under uncertain conditions []. As XML continues to evolve, its application in composite design proactively addresses the complexity of material behavior, offering a robust tool for enhancing design accuracy and safety.

Furthermore, AI can be integrated directly into reliability-based design optimization (RBDO). The integration of GA and ANN was able to address reliability constraints in laminated composite structures []. By incorporating a reliability index within the optimization process, these AI techniques enhance the structural design by accommodating variations in loading conditions, fiber orientations, and ply thicknesses. This approach not only streamlines the computational process, reducing the need for extensive experimental trials, but also improves accuracy and saves computational time, even in the presence of non-linear behaviors [].

Figure 4 shows how uncertainty in material properties, geometry, and defects is fed into an AI surrogate (based on FEA and neural networks) to quickly predict behavior of an open-hole CFRP laminate, from which statistical design allowables (like A-basis) are derived for optimized, certifiable designs.

Figure 4.

Managing Uncertainty and Establishing Design Allowable Limits with AI.

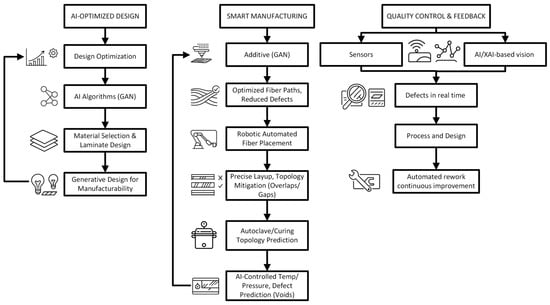

6. AI-Driven Manufacturing and Process Optimization

The optimal design of a composite laminate is of limited value if it cannot be manufactured reliably and cost-effectively. AI is playing an increasingly pivotal role in bridging the gap between design and manufacturing, optimizing fabrication processes, and ensuring that manufacturability constraints are embedded within the design loop from the outset. Figure 5 illustrates a closed-loop framework where AI supports the full manufacturing chain of laminated FRP composites. In AI-optimized design, algorithms choose materials, laminate layups, and generative designs that are manufacturable and performance-optimized. In smart manufacturing, AI guides additive/robotic fiber placement, layup topology, and autoclave curing by controlling paths, temperature, pressure, predicting defects and topology mitigation to reduce defects. Finally, in quality control & feedback, sensors and AI/XAI-based vision detect defects in real time and feed corrections back to both process and design, enabling automated rework and continuous improvement. More information will be provided in the following sections.

Figure 5.

Show Summary of applications of AI Driven Manufacturing and Process Optimization.

6.1. Additive Manufacturing and Automated Fabrication

Additive manufacturing (AM) of composites, with its layer-by-layer approach, generates rich process data that is ideal for AI analysis. In laminated FRP composites, AI is increasingly used to optimize both additive and autoclave manufacturing, where data-driven control of temperature, pressure, and printing parameters improves dimensional accuracy, reduces defects, and enhances mechanical performance []. Explainable AI further helps identify and mitigate defects during curing, ensuring that the final product meets stringent aerospace and civil engineering standards. AI-guided AM enables the creation of complex structures with tailored properties, accelerates simulations, and supports more efficient material selection, thereby reducing the time and cost associated with traditional trial-and-error fabrication []. For example, hybrid Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)–ANN frameworks have been used to refine AM process parameters, with ANN models accurately predicting ultimate tensile strength (UTS) from material and printing variables, ensuring the production of high-quality FRP components [].

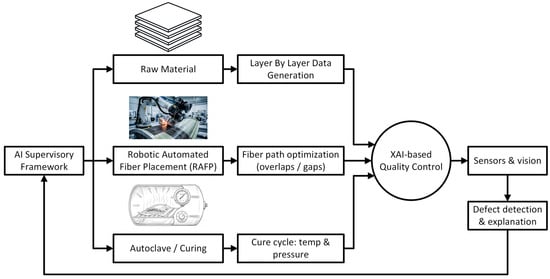

Beyond AM, Robotic Automated Fiber Placement (RAFP) offers a complementary, AI-enabled route for manufacturing laminated FRP composites. Machine-learning surrogates coupled with Genetic Algorithms have been used to optimize fiber paths while explicitly accounting for manufacturing imperfections such as overlaps and gaps, leading to composite panels with improved buckling performance []. The integration of generative design and robotic fabrication within this AI framework allows researchers to automatically generate efficient surface geometries, 3D mesh graphs, and object layouts, and then realize them through robotic processes such as object recognition and adaptive metal sheet folding []. Figure 6 shows an AI framework supervising the entire composite fabrication chain: it optimizes additive and autoclave parameters, uses XAI to detect and mitigate defects, and controls robotic automated fiber placement to select efficient fiber paths, ultimately enabling faster simulations, better material selection, and cheaper, higher-quality FRP components for aerospace and civil engineering.

Figure 6.

Additive Manufacturing and Automated Fabrication.

6.2. Addressing Manufacturability Constraints and Topology Optimization

A key contribution of AI is its ability to handle complex manufacturability constraints that are difficult to formalize in traditional optimization. Addressing manufacturability constraints in the design of laminated FRP composites is crucial for ensuring practical application and performance reliability. The survey by Patterson et al. emphasizes the significance of developing minimally restrictive constraints that accommodate complex FRP designs, which traditional design-for-manufacturing concepts often overlook []. By leveraging AI techniques, engineers can generate and enforce manufacturability constraints at various design levels, from macro to sub-micro scales, facilitating a more integrated and holistic design process []. This approach not only streamlines the production of complex composites but also enhances their sustainability by optimizing resource use and reducing material waste.

The integration of multiscale topology optimization in the design of laminated FRP composites offers a revolutionary approach to enhancing their mechanical properties and manufacturability []. This method allows for the simultaneous optimization of macroscale topology and microscale fiber orientations, which can significantly improve the stiffness and strength of composite structures []. The use of voxel-based multi-material jetting further supports this workflow by enabling the precise fabrication of continuous fiber-reinforced composites with spatially varying properties. The experimental validation of this approach, particularly in 3D-printed planar structures, underscores its potential to produce composites with tailored material distribution, enhancing their performance in demanding aerospace applications.

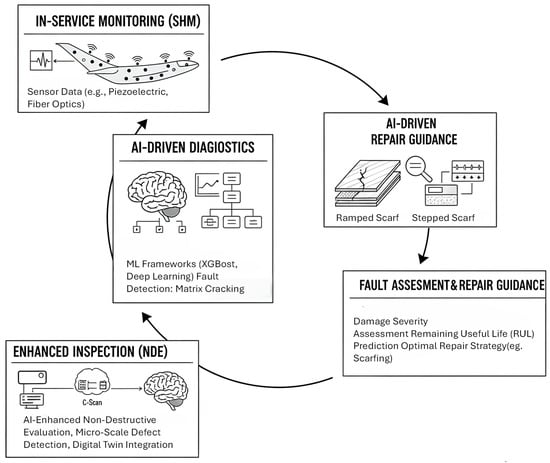

7. AI in Structural Health Monitoring, Fault Assessment, and Repair

The utility of AI extends beyond the design and manufacturing phases into the entire lifecycle of a composite structure. SHM involves using sensor data to detect, localize, and assess damage in real-time. AI, with its pattern recognition capabilities, is perfectly suited to interpret complex signal data from sensors like piezoelectric transducers or fiber optics, enabling predictive maintenance and improving operational safety.

The integration of ML frameworks, particularly those incorporating tree-based models like XGBoost and gradient boosting, represents a significant advance in optimizing CFRP laminate designs []. These models are adept at predicting tensile and bending strengths due to their high accuracy and interpretability, which are crucial for tailoring composite structures to specific engineering demands. By combining experimental results with finite element simulations, these ML approaches enhance the initial datasets, offering a robust platform for performance prediction and design iteration.

The intersection of artificial intelligence and the design of laminated FRP composites parallels advancements seen in other technological domains, such as China’s Earth Observation (EO) system, where AI integration has accelerated innovation []. This synergy highlights the transformative potential of AI in optimizing composite structures, akin to how onboard data processing enhances EO capabilities. The application of deep learning innovations, such as ResNet, in the design and optimization of laminated FRP composites, holds promising potential for advancing structural health monitoring systems []. ResNet’s deep residual learning capabilities allow for the extraction of complex patterns from high-resolution data, enhancing the precision of fault detection in composite materials.

The application of artificial intelligence techniques in the fault assessment of laminated composite structures is gaining traction, as evidenced by recent advancements in supervised and unsupervised machine learning methodologies []. These techniques are pivotal for the accurate diagnosis and condition monitoring of composite structures, particularly in identifying non-linear failure modes such as delamination and matrix cracking. By enhancing fault detection capabilities, AI-driven approaches significantly improve the reliability and safety of composite materials in high-stakes sectors like aerospace and civil engineering. The review highlights that incorporating AI into fault assessment not only addresses current limitations in detecting structural anomalies but also paves the way for more resilient laminate designs.

For damage localization, advanced signal processing combined with ML is highly effective. The strategic integration of multi-feature extraction techniques enhances the efficacy of damage localization in laminated composites, particularly through the innovative application of Lamb-wave-based methodologies []. By leveraging these advanced techniques, explainable machine learning models can pinpoint damage without relying on traditional imaging methods, thereby streamlining the structural health monitoring process. This approach not only optimizes the detection and localization of damage but also facilitates a deeper understanding of the internal dynamics of laminated composites under various stress conditions.

AI also informs repair strategies. The experimental investigation of buckling and post-buckling behavior of composite laminates further underscores the crucial role of artificial intelligence in optimizing repair techniques and structural performance []. By examining Ramped Scarf (RS) and Stepped Scarf (SS) repair schemes, researchers have demonstrated the potential of AI-based machine vision to enhance the quality and reliability of composite repairs under in-plane shear loading. These findings reveal that RS repairs exhibit superior mechanical performance, showing higher maximum displacement and failure load compared to pristine laminates, although they are more prone to repair patch detachment. This highlights the importance of incorporating AI tools in the assessment and improvement of repair methodologies, addressing the unique challenges faced in aerostructures [].

Non-destructive evaluation (NDE) techniques, enhanced by AI, offer substantial benefits in the manufacturing and in-service inspection of laminated FRP composites by detecting internal and external defects without compromising material integrity []. This synergy allows for a comprehensive understanding of microstructural variations during the production process, leading to improved mechanical properties and longer material lifespan. AI-driven NDE not only expedites the analysis but also facilitates the creation of digital material twins, which are crucial for optimizing the design and performance of next-generation biocomposites. The use of advanced imaging techniques such as edge-illumination X-ray dark-field imaging proves invaluable []. This method complements AI-driven design optimization by providing detailed insights into micro-scale defects that often evade traditional detection methods. The ability to visualize and characterize small-scale damage, such as cracks and voids, allows for more precise assessment of structural integrity, which is crucial for maintaining safety standards. Compared with conventional NDE (manual ultrasonic C-scan, tap testing, visual inspection), AI-enhanced methods offer clear quantitative gains. Deep-learning defect detectors in composite laminates typically reach 95–98% accuracy, versus about 80–90% for traditional threshold or handcrafted-feature approaches under similar noise and operator conditions [,,]. Automated AI analysis can process ultrasonic or thermographic data in seconds to minutes, cutting inspection time by roughly a factor of 5–10 compared with manual C-scan interpretation, and several studies report about a 30–50% reduction in missed defects (false negatives) for impact damage, directly improving the reliability of in-service inspections [,].

Figure 7 shows a closed loop for AI-assisted life-cycle management of composites: sensor data from in-service SHM are fed to AI-driven diagnostic models to detect and classify damage; this informs fault assessment (severity, remaining useful life (RUL), and optimal repair strategy such as ramped or stepped scarf), and AI-enhanced NDE provides detailed imaging and micro-defect detection, feeding back to update diagnostics and digital twins.

Figure 7.

AI in Structural Health Monitoring, Fault Assessment, and Repair.

8. Challenges, Future Directions, and Conclusions

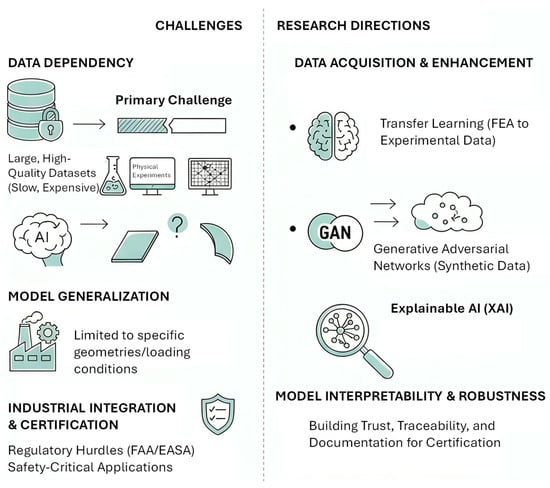

8.1. Persistent Challenges and Research Gaps

Despite significant progress, the widespread adoption of AI in composite design and optimization faces several challenges. The transformative potential of AI in composite material engineering, as highlighted by recent studies, presents both challenges and opportunities that are pivotal to advancing the design of laminated FRP composites []. Addressing issues such as data acquisition and model interpretability, researchers are now focusing on strategies to enhance these areas, which include improving data collection techniques and developing more interpretable AI models. These advancements are crucial for overcoming existing computational limitations and ensure that AI can be effectively integrated into the design process.

The primary challenge is data dependency. High-fidelity AI models require large, high-quality datasets for training. Generating this data through high-fidelity FEA or, more critically, physical experiments, is time-consuming and expensive. Techniques like transfer learning, where a model pre-trained on a large FEA dataset is fine-tuned with a smaller set of experimental data, and the use of generative adversarial networks (GANs) to create synthetic data are promising avenues for research. As noted by Cakiroglu & Cakiroglu, integrating these ensemble learning techniques with data enhancement strategies, such as generating synthetic datasets with tabular generative adversarial networks, can significantly improve the robustness and reliability of laminated composite designs [].

Model generalization is another critical issue. An AI model trained on a specific class of laminates (e.g., flat plates) may not perform well on a different geometry (e.g., curved shells) or under a different loading condition. Developing AI frameworks that are more adaptable and can generalize across a broader range of composite structures and physical scenarios is a key research direction. AI’s capabilities extend beyond the repair and enhancement of composite materials, playing a pivotal role in the initial design and analysis of steel structures []. Addressing challenges such as data limitations and model generalization, AI thus becomes a critical asset in bridging the gap between research innovations and practical implementation in aerospace and civil engineering projects.

Furthermore, the full integration into industrial workflows and certification remains a hurdle. Regulatory bodies like the FAA and EASA have stringent requirements for certifying aerospace structures. Demonstrating the reliability and traceability of AI-driven designs is essential for their acceptance in safety-critical applications. The continued development and application of XAI will be paramount in building the necessary trust and providing the required documentation for certification processes.

Finally, Real-time deployment of AI-enabled SHM systems is limited by practical issues in both computation and data acquisition. Continuous sensing on large structures can generate massive data streams that exceed available bandwidth and storage, unless significant edge processing or smart triggering is used (e.g., on bridges, wind turbines, and aircraft structures). Models must often run on low-power hardware in harsh environments, so latency, model size, and energy consumption become critical constraints. On the sensing side, temperature, moisture, EMI, and mechanical damage can degrade or disconnect sensors, while poor synchronization of heterogeneous signals (vibration, images, environmental data) can introduce artefacts that mimic damage. Because real structures rarely provide clean, labeled data for all damage states, deployed models must handle class imbalance and changing conditions without producing excessive false alarms, and they must integrate securely with existing control/asset-management systems to be trusted in safety-critical use. Table 3 summarizes key challenges and corresponding AI-driven opportunities and future research pathways.

Table 3.

Key challenges and future research directions for AI in laminated FRP composites.

Figure 8 contrasts the main challenges of using AI for laminated FRP composites with key research directions. It highlights data dependency, limited model generalization to specific geometries/loadings, and difficulties with industrial integration and certification in safety-critical sectors (FAA/EASA). It shows also how research is addressing these issues through better data acquisition and, explainable AI to increase transparency, and improved model interpretability and robustness to build trust, traceability, and documentation for certification.

Figure 8.

AI Challenges and Research Directions.

8.2. Future Outlook and Emerging Trends

The future of AI in laminated composite design is exceptionally bright, driven by several emerging trends. The exploration of AI in the design of ship and offshore structures offers valuable insights applicable to the optimization of laminated FRP composites []. The incorporation of life-cycle effects and the management of imperfections are critical aspects that AI can address, providing robust solutions through predictive analytics and optimization algorithms. One promising direction is the deeper integration of AI with multiscale modeling. MLapplications in the design of laminated FRP composites are revolutionizing the approach to optimizing material properties by addressing complex multi-scale architecture challenges []. These algorithms serve as efficient surrogate models that extract critical material information, enabling the discovery of composites with novel and enhanced properties. This will allow for the simultaneous optimization of the microstructure (e.g., fiber architecture in a textile) and the macrostructure (e.g., laminate stacking sequence) in a seamless workflow. Another trend is the development of physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), which incorporate the governing physical equations (e.g., equilibrium equations, constitutive laws) directly into the loss function of the neural network. This hybrid approach can reduce the amount of data required for training and ensure that the model’s predictions are physically consistent, even in regions of the design space where data is sparse.

The concept of the digital twin, a virtual, dynamic replica of a physical composite structure, will be heavily reliant on AI. By continuously updating the digital twin with sensor data from the physical asset (SHM), AI models can predict remaining useful life, optimize maintenance schedules, and even suggest design improvements for future iterations. The integration of AI-enhanced DevOps strategies, as outlined by Alnafessah et al., facilitates continuous integration and delivery (CI/CD) pipelines, which are critical for managing the iterative processes inherent in the AI-driven design cycles of composite materials []. This synergy not only accelerates the deployment of optimized FRP composites but also ensures that they meet stringent performance standards.

The most recent trend is integration of language models (LLMs) in the design and optimization of laminated FRP composites [,,]. These models, such as those implemented using the LangChain framework with OpenAI’s, offer enhanced flexibility and autonomy in engineering workflows. By utilizing deterministic tools that encode process planning knowledge, LLMs enable multi-step solution paths for complex challenges like cycle time estimation and resource allocation. This innovative approach not only streamlines the design process but also improves the precision of resource deployment and efficiency, directly impacting the manufacturability and cost-effectiveness of composite structures. Consequently, the application of LLM-based agents can significantly contribute to optimizing the entire lifecycle of composite materials, aligning with the broader goals of AI-driven advancements in structural engineering.

Finally, AI will continue to drive innovation in architected materials. The integration of multidimensionally ordered mesoporous intermetallics (MOMIs) into laminated FRP composites offers a novel approach to enhancing catalytic activity and structural stability, which could be pivotal for advanced composite applications []. By utilizing MOMIs’ unique physicochemical properties, engineers can potentially address challenges related to the durability and performance of these materials under various environmental conditions.

9. Conclusions

In conclusion, the integration of artificial intelligence into the design and optimization of laminated FRP composites is moving the field from trial-and-error and equation-driven design toward data-driven, model-based workflows. In practical terms, surrogate models combined with evolutionary and metaheuristic algorithms already allow engineers to explore much larger design spaces at a fraction of the computational cost, leading to lighter and more efficient laminates within realistic design timelines. Explainable AI techniques provide interpretable rankings and response trends for stacking sequences, ply angles, and material choices, which can be translated into design rules, process windows, and quality-control tolerances. On the manufacturing and service side, AI-assisted process monitoring and SHM can reduce the likelihood of defects escaping production, shorten inspection times, and enable earlier, more targeted interventions over the structure’s lifecycle.

However, these benefits come with clear limitations that must be acknowledged. High-quality experimental and FEA datasets remain expensive and limited in scope, so many models are still trained on narrow configurations and may not generalize reliably to new geometries, load cases, or manufacturing routes. The black-box nature of some deep architectures, the risk of overfitting, and the possibility of misleading “hallucinations” from LLM-based tools mean that AI outputs cannot yet be treated as standalone truth in safety-critical applications. Moreover, certification and regulatory frameworks (e.g., aerospace and major civil codes) are only beginning to recognize AI-assisted design, and there is not yet a shared standard for validation, XAI reporting, or uncertainty quantification that regulators can routinely accept.

Looking ahead, the most impactful outcomes will come from work that directly closes these gaps: data-efficient and physics-informed models that can operate on realistic test campaigns rather than idealized datasets; robust XAI and reliability metrics that can support formal certification; edge-capable SHM pipelines that cope with sensor degradation and evolving damage; and domain-grounded LLM copilots that are tightly linked to vetted material databases and design standards. If these directions are pursued, AI will move from a promising research tool to a practical, trusted component of everyday composite engineering—supporting, rather than replacing, human judgment in delivering safer, lighter, and more economical laminated FRP structures for aerospace, civil, mechanical, and marine applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Data Collection, Software, Formal analysis and Writing—original draft preparation: A.E.; Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Software, Visualization, and writing—review and editing: S.A.-M.; Supervision, Formal analysis, Investigation, and writing—review and editing: H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was generated in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used DeepSeek for the purposes of text polishing and Gemini for enhancing Sketches. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghimire, R.; Raji, A. Use of Artificial Intelligence in Design, Development, Additive Manufacturing, and Certification of Multifunctional Composites for Aircraft, Drones, and Spacecraft. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeinali, M.; Rahimi, G.; Hosseini, S. Buckling Load Estimation for Sandwich Plates with Innovative Circular Cell Cores via Nondestructive Vibration Correlation Technique and Machine Learning. J. Eng. Mech. 2025, 151, 4025027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, L.; Alnowibet, K.A. Optimizing Structural Resilience of Composite Smart Structures Using Predictive Artificial Intelligence and Carrera Unified Formulation: A New Approach to Improve the Efficiency of Smart Building Construction. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jegadeesan, K.; Shankar, K.; Datta, S. Design Optimization of Smart Laminated Composite for Energy Harvesting Through Machine Learning and Metaheuristic Algorithm. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2025, 50, 9325–9338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, W.; Yu, T.; Liu, W.; Li, Y. Intelligent Methods for Optimization Design of Lightweight Fiber-Reinforced Composite Structures: A Review and the-State-of-the-Art. Front. Mater. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B. Orthogonal Array-Based Latin Hypercubes. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1993, 88, 1392–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, A.B. Orthogonal Arrays for Computer Experiments, Integration and Visualization. Stat. Sin. 1992, 2, 439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, K.Q. Orthogonal Column Latin Hypercubes and Their Application in Computer Experiments. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1998, 93, 1430–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qin, J.; Zhao, K.; Featherston, C.A.; Kennedy, D.; Jing, Y.; Yang, G. Design Optimization of Laminated Composite Structures Using Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. Compos. Struct. 2023, 305, 116500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercument, D.B.; Safaei, B.; Sahmani, S.; Zeeshan, Q. Machine Learning and Optimization Algorithms for Vibration, Bending and Buckling Analyses of Composite/Nanocomposite Structures: A Systematic and Comprehensive Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 1679–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Taras, A. Prediction of the Local Buckling Strength and Load-Displacement Behaviour of SHS and RHS Members Using Deep Neural Networks (DNN)—Introduction to the Deep Neural Network Direct Stiffness Method (DNN-DSM). Steel Constr. 2022, 15, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Sahib, M.; Kovács, G. Multi-Objective Optimization of Composite Sandwich Structures Using Artificial Neural Networks and Genetic Algorithm. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Quagliato, L.; Park, D.; Berti, G.A.; Kim, N. A Buckling Instability Prediction Model for the Reliable Design of Sheet Metal Panels Based on an Artificial Intelligent Self-Learning Algorithm. Metals 2021, 11, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, M.A.; Bischof, R.; Riedel, H.; Schmeiser, L.; Pauli, A.; Stelzer, I.; Drass, M. Strength Lab AI: A Mixture-of-Experts Deep Learning Approach for Limit State Analysis and Design of Monolithic and Laminate Structures Made of Glass. Glass Struct. Eng. 2024, 9, 607–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, H.B.; Le, L.M.; Duong, H.T.; Nguyen, T.C.; Pham, T.A.; Le, T.T.; Le, V.M.; Nguyen-Ngoc, L.; Pham, B.T. Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Approaches for Predicting Critical Buckling Load of Structural Members under Compression Considering the Influence of Initial Geometric Imperfections. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, L.M.; Ly, H.B.; Pham, B.T.; Le, V.M.; Pham, T.A.; Nguyen, D.H.; Tran, X.T.; Le, T.T. Hybrid Artificial Intelligence Approaches for Predicting Buckling Damage of Steel Columns under Axial Compression. Materials 2019, 12, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, N.X.; Le, T.-T.; Dinh, T.-H.; Nguyen, V.-H. Prediction of Buckling Damage of Steel Equal Angle Structural Members Using Hybrid Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, A.H.; Haghi, P.; Shokrieh, M.M. Prediction of Fatigue Life of Laminated Composites by Integrating Artificial Neural Network Model and Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 188, 108528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Q.; Zhuo, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Peng, M.; Fan, K.; Qin, Y. Machine Learning-Based Optimization of Impact-Resistant Layups for FRP Hybrid Laminates in Yachts. Ocean Eng. 2025, 324, 120600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehteram, M.; Panahi, F.; Ahmed, A.N.; Mosavi, A.H.; El-Shafie, A. Inclusive Multiple Model Using Hybrid Artificial Neural Networks for Predicting Evaporation. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 9, 789995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastjan, P.; Kuś, W. Method for Parameter Tuning of Hybrid Optimization Algorithms for Problems with High Computational Costs of Objective Function Evaluations. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, K.; Refahi Sheikhani, A.H.; Kordrostami, S.; Khoshhal Roudposhti, K. New Hybrid Feature Selection Approaches Based on ANN and Novel Sparsity Norm. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 2024, 7112770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Reshi, A.A.; Shafi, S.; Aljubayri, I. An Adaptive Hybrid Framework for IIoT Intrusion Detection Using Neural Networks and Feature Optimization Using Genetic Algorithms. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardozo, S.D.; Gomes, H.M.; Awruch, A.M. Optimization of Laminated Composite Plates and Shells Using Genetic Algorithms, Neural Networks and Finite Elements. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2011, 8, 413–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yossef, M.; Noureldin, M.; Alqabbany, A. Explainable Artificial Intelligence Framework for FRP Composites Design. Compos. Struct. 2024, 341, 118190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, S.; Nasiri, H.; Ghorbani, O.; Friswell, M.I.; Castro, S.G.P. Explainable Artificial Intelligence to Investigate the Contribution of Design Variables to the Static Characteristics of Bistable Composite Laminates. Materials 2023, 16, 5381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.M.; Kim, H.S. An Explainable Artificial Intelligence-Based Approach for Reliable Damage Detection in Polymer Composite Structures Using Deep Learning. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 1536–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, C.; Pereira, L.F.; Tavares, R.P.; Salgado, M.; Otero, F.; Catalanotti, G.; Arteiro, A.; Bessa, M.A.; Camanho, P.P. A Methodology to Generate Design Allowables of Composite Laminates Using Machine Learning. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2021, 233, 111095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumbo, R.; Baroni, A.; Ricciardi, A.; Corvaglia, S. Design Allowables of Composite Laminates: A Review. J. Compos. Mater. 2022, 56, 3617–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, K.T.Q.; Le, T.C.; Zhang, G. Review on the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Predict Fire Performance of Construction Materials and Their Flame Retardancy. Molecules 2021, 26, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osa-uwagboe, N.; Udu, A.G.; Ghalati, M.K.; Silberschmidt, V.V.; Aremu, A.; Dong, H.; Demirci, E. A Machine Learning-Enabled Prediction of Damage Properties for Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites under out-of-Plane Loading. Eng. Struct. 2024, 308, 117970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, M.; Chaudhari, K. Large Language Model Based Agent for Process Planning of Fiber Composite Structures. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 40, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, M.J. MechGPT, a Language-Based Strategy for Mechanics and Materials Modeling That Connects Knowledge Across Scales, Disciplines, and Modalities. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2024, 76, 21001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shukla, S.N.; Azab, M.; Singh, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, D.; Peng, S.; Yu, H.; Yan, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. CompCap: Improving Multimodal Large Language Models with Composite Captions. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakiroglu, C. Explainable Data-Driven Ensemble Learning Models for the Mechanical Properties Prediction of Concrete Confined by Aramid Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Wraps Using Generative Adversarial Networks. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 11991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieradzki, A.; Bednarek, J.; Jegorowa, A.; Kurek, J. Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques for Convolutional Neural Network-Based Classification of Drilled Holes in Melamine Faced Chipboard. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škorić, M.; Utvić, M.; Stanković, R. Transformer-Based Composite Language Models for Text Evaluation and Classification. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, C.; Qian, Y.; Zhou, L.; Liu, S.; Zeng, M.; Huang, X. ComSL: A Composite Speech-Language Model for End-to-End Speech-to-Text Translation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.14838. [Google Scholar]

- Radha, S.K.; Goktas, O. Composite Learning Units: Generalized Learning Beyond Parameter Updates to Transform LLMs into Adaptive Reasoners. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.08037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, G.; Chawla, K.; Ghosal, T.; Villez, K.; Coughlin, D.; Rucker, T.; Paquit, V.; Ozcan, S.; Kim, S. Intelligent Manufacturing Support: Specialized LLMs for Composite Material Processing and Equipment Operation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.06734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CMH-17 Composite Materials Handbook Volume 1: Polymer Matrix Composites—Guidelines for Characterisation of Structural Materials; US Department of Defense: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Volume 1.

- Daghigh, V.; Daghigh, H.; Keller, M.W. Uncertainty-Based Design: Finite Element and Explainable Machine Learning Modeling of Carbon–Carbon Composites for Ultra-High Temperature Solar Receivers. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, G.F.; Mesquita, M.H.; Bendine, K. Predictive Modeling of Buckling in Composite Tubes: Integrating Artificial Neural Networks for Damage Detection. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2025, 32, 2659–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.M.; Awruch, A.M.; Lopes, P.A.M. Reliability Based Optimization of Laminated Composite Structures Using Genetic Algorithms and Artificial Neural Networks. Struct. Saf. 2011, 33, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadharshini, M.; Balaji, D.; Bhuvaneswari, V.; Rajeshkumar, L.; Sanjay, M.R.; Siengchin, S. Fiber Reinforced Composite Manufacturing With the Aid of Artificial Intelligence—A State-of-the-Art Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 5511–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Advincula, R.C.; Wu, H.F.; Jiang, Y. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Design and Additive Manufacturing of Responsive Composites. MRS Commun. 2023, 13, 714–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaddad, W.; He, M.; Halabi, Y.; Yahya Mohammed Almajhali, K. Optimizing the Material and Printing Parameters of the Additively Manufactured Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites Using an Artificial Neural Network Model and Artificial Bee Colony Algorithm. Structures 2022, 46, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayachandran, A.A.; Davidson, P.; Waas, A.M. Optimal Fiber Paths for Robotically Manufactured Composite Structural Panels. Int. J. Non Linear Mech. 2020, 126, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussavi, S.M.; Svatoš-Ražnjević, H.; Körner, A.; Tahouni, Y.; Menges, A.; Knippers, J. Design Based on Availability: Generative Design and Robotic Fabrication Workflow for Non-Standardized Sheet Metal with Variable Properties. Int. J. Space Struct. 2022, 37, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.E.; Lee, Y.H.; Allison, J.T. Generation and Enforcement of Process-Driven Manufacturability Constraints: A Survey of Methods and Perspectives for Product Design. J. Mech. Des. 2021, 143, 110801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Boon, Y.; Joshi, S.C.; Bhudolia, S.K.; Gohel, G. Recent Advances on the Design Automation for Performance-Optimized Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite Components. J. Compos. Sci. 2020, 4, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boddeti, N.; Tang, Y.; Maute, K.; Rosen, D.W.; Dunn, M.L. Optimal Design and Manufacture of Variable Stiffness Laminated Continuous Fiber Reinforced Composites. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Wei, Q.; Wang, T.; Ma, Q.; Jin, P.; Pan, S.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Experimental and Numerical Investigation Integrated with Machine Learning (ML) for the Prediction Strategy of DP590/CFRP Composite Laminates. Polymers 2024, 16, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Guo, H.; Jin, W. On China’s Earth Observation System: Mission, Vision and Application. Geospat. Inf. Sci. 2025, 28, 303–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, G.; Bibbò, L.; Meduri, G.M.; Genovese, E.; Barrile, V. Deep Learning Innovations: ResNet Applied to SAR and Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, S.; Mahapatra, T.R.; Dash, S.; Murty, V.K. Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Fault Assessment in Laminated Composite Structure: A Review. E3S Web Conf. 2021, 309, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Azad, M.M.; Kim, H.S. Multi-Feature Extraction and Explainable Machine Learning for Lamb-Wave-Based Damage Localization in Laminated Composites. Mathematics 2025, 13, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damghani, M.; Bugaje, A.; Atkinson, G.A.; Cole, D. Experimental Investigation of Buckling and Post-Buckling Behaviour of Repaired Composite Laminates under in-Plane Shear Loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205, 112489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preethikaharshini, J.; Naresh, K.; Rajeshkumar, G.; Arumugaprabu, V.; Khan, M.A.; Khan, K.A. Review of Advanced Techniques for Manufacturing Biocomposites: Non-Destructive Evaluation and Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Modeling. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 16091–16146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrizzi, M.; Murat, B.I.S.; Fromme, P.; Olivo, A. Edge-Illumination X-Ray Dark-Field Imaging for Visualising Defects in Composite Structures. Compos. Struct. 2015, 134, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Li, W.; Jiang, P.; Chen, F.; Liu, Y. Deep Learning Approach for Damage Classification Based on Acoustic Emission Data in Composite Materials. Materials 2022, 15, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, S.; Dürrmeier, F.; Grosse, C.U. Spatial and Temporal Deep Learning in Air-Coupled Ultrasonic Testing for Enabling NDE 4.0. J. Nondestruct. Eval. 2023, 42, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Mitchell, D.; Blanche, J.; Harper, S.; Tang, W.; Pancholi, K.; Baines, L.; Bucknall, D.G.; Flynn, D. A Review of Sensing Technologies for Non-Destructive Evaluation of Structural Composite Materials. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero-Chinchilla, S.; Wilcox, P.D.; Croxford, A.J. Deep Learning in Automated Ultrasonic NDE—Developments, Axioms and Opportunities. NDT E Int. 2022, 131, 102703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeske, B.; Osman, A.; Römer, F.; Tschuncky, R. Next Generation NDE Sensor Systems as IIoT Elements of Industry 4.0. Res. Nondestruct. Eval. 2020, 31, 340–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umeliwu, O.A.; Samuel, B.O. Challenges and Opportunities of Artificial Intelligence on Composite Material Engineering. J. Sustain. Mater. Process. Manag. 2024, 4, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarfarazi, S.; Mascolo, I.; Modano, M.; Guarracino, F. Application of Artificial Intelligence to Support Design and Analysis of Steel Structures. Metals 2025, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, P.E.; An, C.; Brubak, L.; Chen, X.; Chiu, J.T.; Czujko, J.; Darie, I.; Feng, G.; Gaiotti, M.; Jang, B.S.; et al. Committee III.1: Ultimate Strength. In Proceedings of the 2022 21st International Ship and Offshore Structures Congress, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 11–15 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, L.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Khorami, M.; Mahmoudi, T.; Wu, H. Modified Couple Stress and Artificial Intelligence Examination of Nonlinear Buckling in Porous Variable Thickness Cylinder Micro Sport Structures. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 31, 12135–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnafessah, A.; Gias, A.U.; Wang, R.; Zhu, L.; Casale, G.; Filieri, A. Quality-Aware DevOps Research: Where Do We Stand? IEEE Access 2021, 9, 44476–44489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitton, S.F.; Ricci, S.; Bisagni, C. Buckling Optimization of Variable Stiffness Cylindrical Shells through Artificial Intelligence Techniques. Compos. Struct. 2019, 230, 111513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Yang, J. Machine Learning Applications in Composites: Manufacturing, Design, and Characterization. In ACS Symposium Series; ACS Publication: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Volume 1416. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Liu, B. Multidimensionally Ordered Mesoporous Intermetallics: Frontier Nanoarchitectonics for Advanced Catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2024, 53, 11321–11333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).