Abstract

The structural integrity of adhesively bonded composites is critically dependent on manufacturing process fidelity. While the MGS L418 epoxy system is widely used in aerospace applications, a quantitative hierarchy of its process variables is absent from the literature, leading to reliance on qualitative guidelines and inherent performance variability. This study closes this gap through a comprehensive sensitivity analysis. A 26-2 fractional factorial Design of Experiments (DOE) quantified the effects of six variables on single-lap shear strength. An Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) established a definitive hierarchy: induction time was the dominant factor, with a sub-optimal 15 min period causing a 74% strength reduction (p < 0.000). Surface preparation was the second most significant factor, with mechanical abrasion increasing strength by 17% (p = 0.000). Ambient humidity was a marginal factor (p = 0.013), linked to amine blush formation. The interaction effects were statistically insignificant, simplifying the control strategy. This work provides a validated, quantitative model that defines a robust process window, prioritizing induction time and surface preparation to de-risk manufacturing and ensure the reliability of safety-critical bonded structures.

1. Introduction

The adoption of advanced composite materials in the aerospace industry is driven by an uncompromising demand for lightweight and high-performance structures [1,2]. Adhesive bonding is the technology enabling the assembly of these components, offering superior stress distribution and eliminating stress concentrations inherent to mechanical fasteners [3,4]. However, the performance of an epoxy adhesive is not an intrinsic material property but a process-defined characteristic. The transformation from a liquid mixture to a structural solid is a kinetic process exquisitely sensitive to manufacturing conditions [5]. This sensitivity is a primary source of performance scatter and a critical risk, as sub-critical bond flaws can evade inspection and lead to catastrophic in-service failures [6].

The MGS L418 two-part epoxy system is a benchmark for bonding primary and secondary structures, particularly in gliders, light aircraft, and other applications where a long working time and low initial viscosity are required for large-scale wet lay-up or component assembly. Despite its prevalence, a quantitative model defining the hierarchical influence of its process variables remains a significant knowledge gap. Current guidelines are often qualitative (e.g., “avoid high humidity”), forcing manufacturers to rely on costly internal validation or overly conservative specifications [7]. This research deficit means that the principal sources of variability for this specific system are not well understood or ranked.

Extensive research has focused on optimizing joint strength through other avenues. Many studies have investigated the influence of adherend geometry, showing that tapering the adherends or using spew fillets can significantly reduce stress concentrations at the overlap ends [8,9]. Others have explored hybrid joints (e.g., bonded-bolted) to improve damage tolerance and load-bearing capacity over bonded-only joints [10]. While this work is critical, it often presupposes an ideal adhesive layer. Less understood is the quantitative, relative impact of the manufacturing process variables that create that layer.

Successful adhesion requires two primary conditions: adequate wetting of the substrate by the adhesive and the subsequent solidification of the adhesive to a state capable of bearing load [1,11]. The quality of the interface between the substrate and the adhesive is therefore paramount and is governed by surface energy and preparation [12]. Surface preparation is widely cited as a critical factor in achieving a durable bond [13,14], as its goal is to create a clean, chemically active, and topographically suitable surface [13]. Mechanical methods like grit or sandblasting increase surface roughness, which enhances mechanical interlocking and provides a larger surface area for bonding [15,16].

The MGS L418 system cures via a polyaddition reaction between epoxy functional groups and amine functional groups in the hardener [17,18]. This reaction is susceptible to several environmental factors. In the presence of atmospheric moisture and carbon dioxide, primary amines on the uncured surface can react to form ammonium carbamates [19,20]. This waxy, water-soluble layer, known as amine blush, is physically weak and non-adherent, leading to a weak boundary layer and catastrophic interfacial failure [19,20,21]. Furthermore, the induction time (the period after mixing but before application) allows for initial polymerization, or B-staging [22]. This builds molecular weight, increasing viscosity. The rheological state of the adhesive at the moment of application is critical for proper wetting and achieving the desired bond line thickness [22].

This research addresses the existing process knowledge gap by employing a structured Design of Experiments (DOE) framework [23]. Our objective is to replace anecdotal understanding with a data-driven, quantitative hierarchy of control for the MGS L418 system, enabling robust and reliable manufacturing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Substrates were 25.4 mm (1-inch) diameter coupons machined from an 8-ply, 121 °C (250 °F) cure glass pre-preg laminate with a nominal thickness of 2.5 mm. The 25.4 mm diameter was selected as it is a standard dimension for fabricating single-lap shear specimens from composite panels and is compatible with common grips for mechanical testing.

The adhesive system used was EPIKOTE MGS L418 epoxy resin combined with H418 hardener (Westlake Epoxy, Houston, TX, USA). This two-component epoxy features low viscosity (1400 mPa·s for the resin and 100 mPa·s for the hardener), a long pot life of approximately 60 min, and a high glass transition temperature (Tg) of 120 °C. It is certified for aerospace applications, ensuring reliability and performance under demanding conditions.

2.2. Design of Experiments

A 16-run, 26-2 fractional factorial design was used to screen six process variables. Each of the 16 unique experimental runs was replicated three times, for a total of 48 distinct samples, to ensure statistical power and account for experimental variability. The six process variables (factors) and their low (−) and high (+) levels are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

DOE experimental matrix, factors (coded levels −1, +1), and response (Ultimate Tensile Load).

- Surface Preparation: Compared a low-level (solvent wipe-only) with a high-level (mechanical abrasion via sandblasting) method.

- Induction Time: The hold time post-mixing. A 15 min (low) versus an 85 min (high) period was evaluated.

- Humidity: Ambient relative humidity (RH) during application and cure (Low: 40% RH vs. High: 90% RH).

- Stirring: Manual stirring (low) vs. mechanical planetary mixing (high).

- Temperature: Ambient temperature during application (Low: 18 °C vs. High: 25 °C).

- Mix Ratio: Deviations from the nominal 100:40 ratio (Low: 98:40 vs. High: 102:40).

2.3. Sample Preparation and Bonding

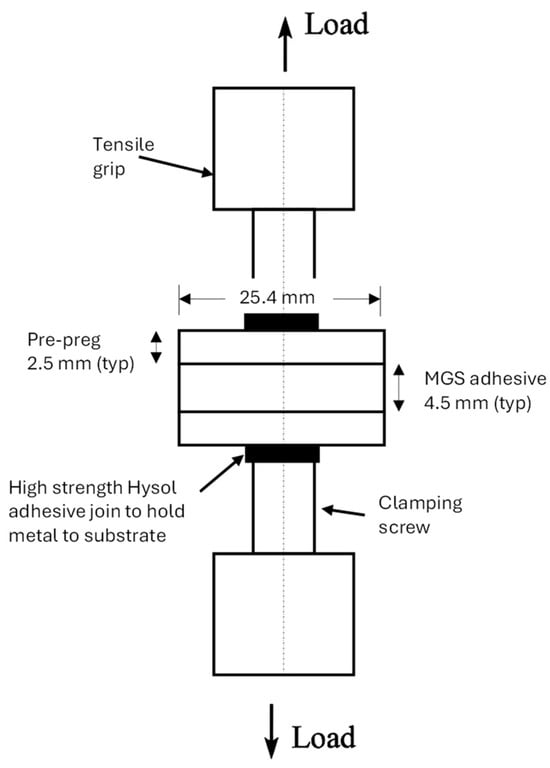

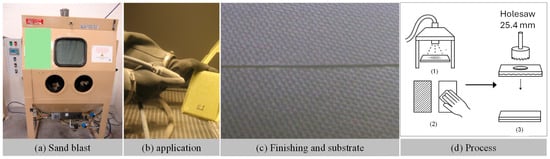

For the high-level surface preparation (+1), substrates were mechanically abraded using 120-grit aluminum oxide sandblasting at 0.55 MPa (80 psi), followed by a two-wipe cleaning procedure with isopropyl alcohol in a controlled cleanroom environment. For the low-level preparation (−1), only the two-wipe cleaning process was performed. The specimen was fabricated in accordance with the design specifications illustrated in Figure 1. The manufacturing process of the composite pre-preg section of the specimen is detailed in Figure 2, which outlines the equipment used for sandblast preparation, the hole-saw operation, and the cleanliness protocols followed during fabrication.

Figure 1.

Single-lap shear specimen.

Figure 2.

Sample preparation process: (a) sandblasting equipment, (b) sandblast application, and (c) sample cleaning with wipes. After preparing the rectangular prepreg coupons, MGS418 adhesive is applied to join both coupons, and a (d) 25.4 mm (1-inch) holesaw is used to extract the substrate.

The adhesive was mixed according to the ratio of 100:40 by weight. For mechanical stirring, a planetary mixer was used at 150 RPM. Following mixing, the adhesive was held for the specified induction time in a controlled environment. A consistent bead of adhesive was applied to one substrate, and the joint was assembled with the second substrate to create a single-lap shear specimen with a 9.5 mm (0.37-inch) overlap. Assemblies were cured in a fixture applying uniform pressure of 0.14 MPa (20 psi) using a calibrated pneumatic press to ensure consistency. The cure cycle was conducted in an oven at 80 °C (176 °F) for 4 h, as per manufacturer recommendations for an elevated temperature cure.

2.4. Mechanical Testing

Tensile lap shear tests were conducted on a calibrated 10 kN universal testing machine following the general principles of ASTM D1002 [24] for guidance on test setup and procedure, as shown in Figure 3. A constant crosshead displacement rate of 1.3 mm/min was applied until joint failure. The peak lap shear load (in Newtons) was recorded as the primary response.

Figure 3.

Lap shear testing of a bonded coupon specimen, as specified in the materials and method section.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The experimental data was analyzed using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a significance level (α) of 0.010 to determine the statistical significance of main effects and two-factor interactions.

3. Results

The peak lap shear load for each of the 48 experimental runs was recorded (Table 1) and analyzed. The ANOVA results are summarized in Table 2. The model F-value of 601.99 with p < 0.000 indicates that the model is highly significant.

Table 2.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) for Bond Strength.

- Factor B (Induction Time) exhibited the largest effect, with an F-value of 8808.87 (p < 0.000).

- Factor A (Surface Preparation) was the second most significant effect, with an F-value of 139.96 (p = 0.000).

- Factor C (Humidity) was marginally significant, with an F-value of 6.9 (p = 0.013).

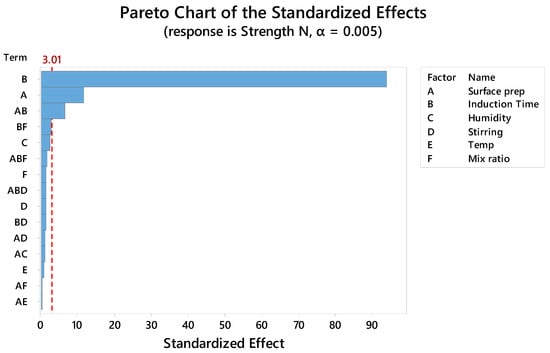

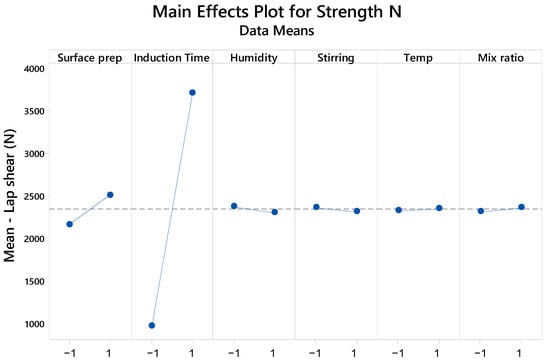

All other factors were statistically insignificant (p > 0.10). The Pareto Chart (Figure 4) clearly illustrates this hierarchy. The Main Effects Plot (Figure 5) illustrates the magnitude and direction of each factor’s influence. Moving from the low to high level of Induction Time produced the largest positive change in mean strength, while the same change for Surface Preparation produced the second-largest positive change. Conversely, increasing Humidity resulted in a negative change in mean strength.

Figure 4.

Pareto Chart of the Standardized Effects. The chart confirms for main factors that only Induction Time (B) and Surface Preparation (A) exceed the statistical significance threshold (α = 0.005, dashed line).

Figure 5.

Main Effects Plot for Bond Strength.

Qualitative Failure Analysis

While force-displacement curves were not recorded during this DOE, a qualitative analysis of the failure modes was performed, which strongly supports the quantitative data. This analysis provides insight into the nature of the bond failure (e.g., brittle vs. ductile) that complements the ultimate strength values.

Specimens prepared with the sub-optimal 15 min induction time failed at very low loads. These failures were characterized as adhesive (interfacial) failures in a brittle manner. The low-viscosity adhesive was observed to have squeezed out of the joint under clamping pressure, resulting in a starved joint incapable of effective stress transfer.

In contrast, specimens with the optimal 85 min induction time and mechanical surface preparation failed at high loads. These failures were overwhelmingly cohesive, with the failure occurring within the adhesive layer itself, leaving adhesive residue on both substrates. This is the ideal failure mode, as it demonstrates the interfacial bond (adhesive-to-substrate) is stronger than the intrinsic cohesive strength of the epoxy itself.

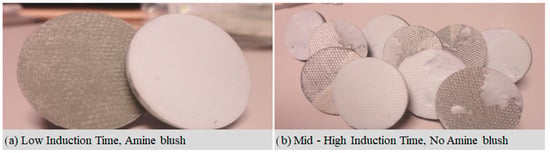

Substrates with low induction time are prone to amine blush due to premature exposure of reactive amines to ambient moisture and CO2, resulting in surface contamination, reduced cross-linking, and poor interfacial bonding, which leads to low lap shear testing results. In contrast, substrates with mid to high induction time undergo a longer pre-reaction period that minimizes the risk of amine blush by allowing the reactive components to partially cure before environmental exposure (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Visual influence of induction time: (a) Substrates with low induction time (15 min) showing amine blush contamination; (b) Substrates with optimal induction time showing clean surfaces and cohesive failure residue.

Specimens prepared with only a solvent wipe (low-level prep), even with optimal induction time, failed interfacial (adhesive failure), though at higher loads than the low-induction-time group. This confirms the surface was not sufficiently activated for a strong bond.

This qualitative assessment confirms the hierarchy identified by the ANOVA: optimal bond strength is achieved only when (1) the rheology is correct (Induction Time) to ensure a cohesive body of adhesive, and (2) the surface is active (Surface Prep) to ensure an interfacial bond stronger than that cohesive body.

4. Discussion

The results of this study provide a clear, quantitative framework for controlling the MGS L418 bonding process. The statistical hierarchy Induction Time > Surface Preparation > Humidity aligns with the fundamental chemical and physical principles of adhesion but, critically, provides the quantitative data necessary for robust industrial process design.

4.1. Dominant Effect of Induction Time on Rheology

The unequivocal dominance of induction time confirms that the rheological state of the adhesive at application is the paramount process parameter. The catastrophic 74% strength loss at the 15 min level is a classic symptom of rheological failure, as visualized in Figure 6. At this short time, the epoxy-amine polyaddition reaction has not progressed sufficiently to build molecular weight. The resulting low-viscosity adhesive is susceptible to being squeezed out of the bond line, leading to starved joints. Furthermore, a less-advanced polymer network has lower intrinsic cohesive strength. The optimal 85 min induction time allows the system to reach a more viscous, gel-like state that re-sists flow-out and ensures a consistent bond line.

4.2. Critical Role of Surface Energetics and Mechanics

The 17% strength increase from mechanical abrasion underscores the non-negotiable role of surface preparation. The solvent wipe-only surface, while clean, is a low-energy, smooth substrate. The sandblasting process increases both the surface free energy and the microscopic surface area. This enhances mechanical interlocking, a key mechanism for adhesion, and provides a more favorable surface for adhesive wetting. The observed shift in failure modes (described in Qualitative Failure Analysis section) from interfacial to cohesive is direct evidence that surface preparation successfully created a bond interface stronger than the adhesive itself.

4.3. Humidity as a Latent Defect Source

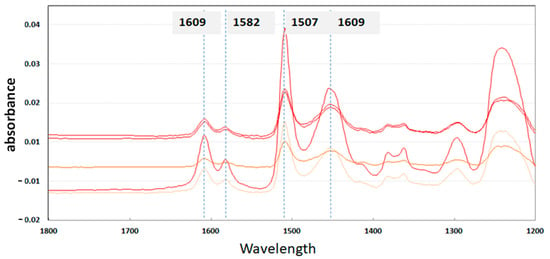

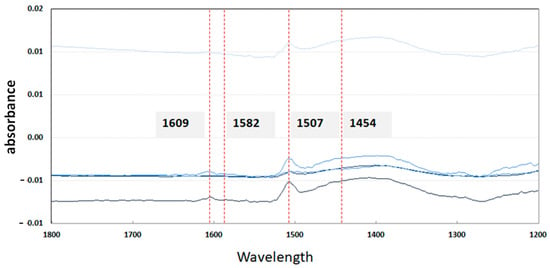

While only marginally significant (p = 0.013), the practical importance of humidity control cannot be overstated. This aligns perfectly with the chemical mechanism of amine blush, which acts as a latent defect. Figure 7 shows the FTIR spectrum of a sample from a high-humidity run with low induction time; the peak at 1582 cm−1 confirms the presence of ammonium carbamates (amine blush). Visual observation of a waxy film on these failed specimens confirmed this. As shown in Figure 8, this blush was not detected in samples with a high induction time, even in high humidity. While its effect might be masked by a more dominant failure mode (like poor rheology), it remains a critical source of inconsistency.

Figure 7.

Amine Blush detected in FTIR for samples with low induction time and 90% humidity. The peak at 1582 cm−1 relative to 1609 cm−1 indicates blush. (Vertical axis: Absorbance; Horizontal axis: Wavenumber, cm−1).

Figure 8.

Amine Blush not detected in FTIR for samples with high induction time at 90% humidity. The 1582 cm−1 peak is absent. (Vertical axis: Absorbance; Horizontal axis: Wavenumber, cm−1).

4.4. Implications for Process Control

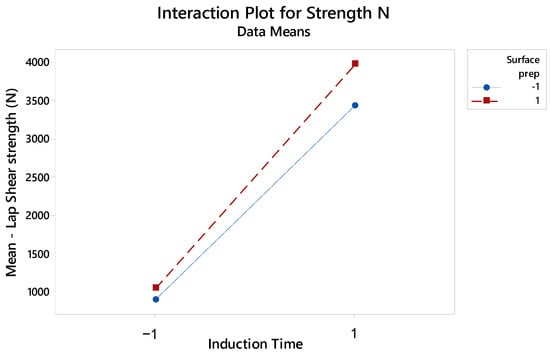

The statistical insignificance of most two-factor interactions (Figure 9) is a powerful outcome for industrial application. It implies that the process can be optimized by controlling each significant factor independently, without needing to account for complex coupled effects. The robustness of the adhesive to minor variations in temperature, the mix ratio, and stirring method simplifies the process by allowing control efforts to be focused where they matter most.

Figure 9.

Interaction Plot for Induction Time and Surface Preparation. The near-parallel lines indicate a lack of significant interaction.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully transitions the understanding of the MGS L418 bonding process from qualitative guidelines to a quantitative, data-driven framework. The results provide a statistically validated hierarchy for manufacturing control:

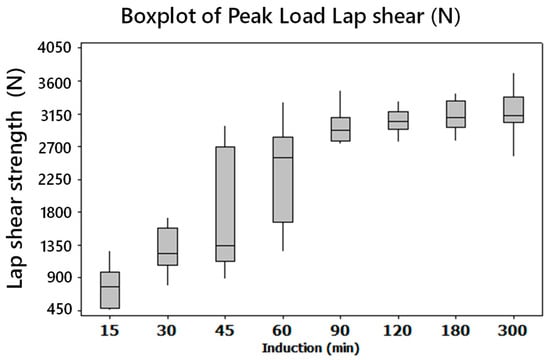

- Primary Control: Induction Time must be rigorously controlled. The optimal window (≥85 min, as shown in Figure 10) allows for proper rheological development to prevent joint starvation and ensure high cohesive strength.

Figure 10. Boxplot of Peak Load (lbf) vs. Induction Time (min). The plot shows strength improving and variability (box size) decreasing as induction time increases, plateauing in the 85–120 min range.

Figure 10. Boxplot of Peak Load (lbf) vs. Induction Time (min). The plot shows strength improving and variability (box size) decreasing as induction time increases, plateauing in the 85–120 min range. - Secondary Control: Surface Preparation Mechanical abrasion is essential to activate the substrate and enable mechanical interlocking, providing a significant and consistent strength benefit.

- Tertiary Control: Ambient Humidity should be maintained below critical levels (<70% RH) to prevent the formation of amine blush and ensure consistent interfacial quality.

By focusing control efforts on this hierarchy, manufacturers can define a robust process window that minimizes variability and de-risks the production of safety-critical composite assemblies.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author. The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request. As the experimental setup involved proprietary materials and internal procedures, no publicly archived datasets were generated. Data sharing is subject to institutional and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used Microsoft Copilot (GPT-4, November 2025 version) solely for refining language and formatting suggestions. No content related to study design, data analysis, or interpretation was generated using AI tools. The author has reviewed and edited all AI-assisted output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| lbf | Pound-force (unit of load) |

| MPa | Megapascal (unit of stress) |

| RH | Relative Humidity |

References

- Pocius, A.V. Adhesion and Adhesives Technology: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Hanser Publications: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2012; ISBN 9781569905111. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritz, A.P. Introduction to Aerospace Materials; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, L.F.M.; Öchsner, A.; Adams, R.D. (Eds.) Handbook of Adhesion Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3-642-01169-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banea, M.D.; da Silva, L.F.M. Adhesively bonded joints in composite materials: An overview. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2009, 223, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, E.M. Epoxy Adhesive Formulations; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.D. Adhesive Bonding: Science, Technology and Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, M.; Sixou, M.; Budtova, T.; Eceiza, A.; Gabilondo, N. Influence of humidity on the curing process and properties of an amine-cured epoxy system. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2017, 144, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Golewski, P.; Sadowski, T. The Influence of Single Lap Geometry in Adhesive and Hybrid Joints on Their Load Carrying Capacity. Materials 2019, 12, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monajati, L.; Vadean, A.; Boukhili, R. Mechanical Behavior of Adhesively Bonded Joints Under Tensile Loading: A Synthetic Review of Configurations, Modeling, and Design Considerations. Materials 2025, 18, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moya-Sanz, E.M.; Ivañez, I.; Garcia-Castillo, S.K. Effect of the geometry in the strength of single-lap adhesive joints of composite laminates under uniaxial tensile load. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 72, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packham, D.E. Handbook of Adhesion, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Raos, G.; Zappone, B. Polymer Adhesion: Seeking New Solutions for an Old Problem. Macromolecules 2021, 54, 10617–10644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchlow, G.W.; Brewis, D.M. Review of surface pretreatments for structural adhesion. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 1996, 16, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegman, R.F.; Van Twisk, J. Surface Preparation Techniques for Adhesive Bonding, 2nd ed.; William Andrew: Norwich, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G.P.; Pocius, A.V. The effects of surface roughness on adhesion. In Adhesion Science and Engineering, Volume 1; Dillard, D.A., Pocius, A.V., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 415–455. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.; Viana, J.C. The effect of grit blasting on the surface properties and adhesion of composite laminates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 91, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pascault, J.P.; Sautereau, H.; Verdu, J.; Williams, R.J. Thermosetting Polymers; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- García, J.M.; Eon, L.; Cado, A.; Bar-Cohen, Y.; Calvo, F.; Goyanes, S. New insights into the curing of epoxy resins. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 623–652. [Google Scholar]

- Schuft, C. Amine Blush: What it is and how to avoid it. Epoxyworks 1998, 12, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente, J.L.; Madaleno, E. The effect of amine blushing on the physical and mechanical properties of a DGEBA/polyetheramine system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 4163–4172. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.V.; Davis, C.R. Characterization and effects of amine blush on epoxy adhesive bonds. J. Mater. Sci. 2001, 36, 935–942. [Google Scholar]

- Halley, P.J.; Mackay, M.E. The effect of B-stage curing on the rheology of an epoxy resin. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1996, 36, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments, 9th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D1002-10; Standard Test Method for Apparent Shear Strength of Single-Lap-Joint Adhesively Bonded Metal Specimens by Tension Loading (Metal-to-Metal). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).