Abstract

Additive manufacturing (AM) is a significant contributor to Industry 4.0. However, one considerable challenge is usually encountered by AM due to the bed size limitations of 3D printers, which prevent them from being adopted. An appropriate post-joining technique should be employed to address this issue properly. This study investigates the influence of key friction stir butt welding (FSBW) factors (FSBWFs), such as tool rotational speed (TRS), tool traverse speed (TTS), and pin profile (PP), on the weldability of 3D-printed PLA–Chromium (PC) composites (3PPCC). A filament containing 10% by weight of chromium reinforced in PLA was used to prepare samples. The material extrusion additive manufacturing process (MEX) was employed to prepare the 3D-printed PCC. A Taguchi-based design of experiments (DOE) (L9 orthogonal array) was employed to systematically assess weld hardness (WH), weld temperature (WT), weld strength (WS), and weld efficiency. As far as the 3D-printed samples were concerned, two distinct infill patterns (linear and tri-hexagonal) were also examined to evaluate their effect on joint performance; however, all other 3D printing factors were kept constant. Experimentally validated findings revealed that weld efficiency varied significantly with PP and infill pattern, with the square PP and tri-hexagonal infill pattern yielding the highest weld efficiency, i.e., 108%, with the corresponding highest WS of 30 MPa. The conical PP resulted in reduced WS. Hardness analysis demonstrated that tri-hexagonal infill patterns exhibited superior hardness retention, i.e., 46.1%, as compared to that of linear infill patterns, i.e., 34%. The highest WTs observed with conical PP were 132 °C and 118 °C for both linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns, which were far below the melting point of PLA. The lowest WT was evaluated to be 65 °C with a tri-hexagonal infill, which is approximately equal to the glass transition temperature of PLA. Microscopic analysis using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) indicated that optimal weld zones featured minimal void formation, directly contributing to improved weld performance. In addition, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) were also performed on four deliberately selected samples to examine the microstructural features and elemental distribution in the weld zones, providing deeper insight into the correlation between morphology, chemical composition, and weld performance.

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) enables unprecedented flexibility in fabricating complex polymer structures and has been revolutionizing modern engineering and industrial applications. Among various techniques, material extrusion additive manufacturing (MEX) is widely adopted due to its cost-effectiveness [1]. Sung-Hoon Ahn et al. [2] and L. Li & Q. Sun et al. [3] acknowledge AM for the ease of operation and its ability to produce complex geometries with minimal material waste. S. A. Kumar & Y. S. Narayan [4] and J. G. Carrillo et al. [5] have mentioned in their research that polylactic acid (PLA) is one of the most frequently utilized thermoplastics in MEX due to its biodegradability, reliable printability, and moderate mechanical properties. However, pure PLA suffers from limitations such as low thermal resistance, brittleness, and suboptimal mechanical strength, rendering it unsuitable for high-load structural applications, as A. R. Torrado Perez et al. [6] and L. Fontana et al. [7] have highlighted in their studies. To address these drawbacks, researchers like W. Cong et al. [8] and H. Li et al. [9] have investigated reinforced composites that add fillers like carbon fibers, nanoparticles, or metal powders to the PLA matrix, achieving improved mechanical performance.

Having attained improved mechanical performance, welding of 3D-printed parts becomes essential due to the bed size limitations of AM, which compel researchers to produce merely size-constrained complex objects. To acquire the required sizes of 3D-printed complex objects, welding is deemed appropriate. Therefore, it is highly desired to weld 3D-printed objects with sufficient bond strength [10,11,12,13].

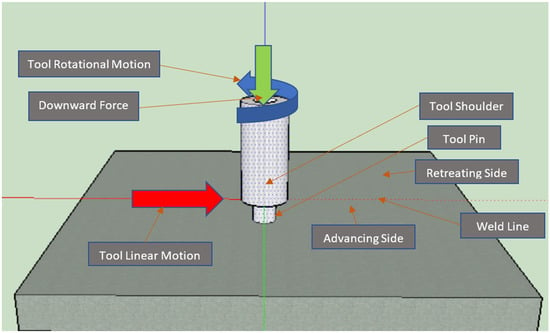

Many researchers have identified various joining techniques to weld various materials. For instance, P. Bettini et al. [14] found that PLA-based composites exhibit enhanced tensile strength and hardness. Effective post-processing and joining methodologies are necessary to maintain structural integrity. B. Kumar et al. [15] and P. L. Threadgill [16] studied traditional joining techniques, such as laser welding and ultrasonic welding, which often lead to excessive thermal exposure, melting, and porosity formation in the joint area. B. M. Darras et al. [17] and K. Abhishek et al. [18] confirmed that friction stir butt welding (FSBW) is a solid-state joining process that overcomes these issues by generating controlled frictional heat and plastic flow without melting the polymeric materials, in contrast to other joining processes, resulting in defect-free joints and retaining mechanical properties. M. Arab et al. [19] and A. M. Hassan et al. [20] reported that FSBW uses a rotating tool to induce required heat and shear deformation, enabling efficient material consolidation.

S. S. Ambati & R. Ambatipudi [21] and S. F. Khan et al. [22] explained in their respective studies that the selection of a proper infill pattern during AM plays a critical role in strengthening 3D-printed PLA components, whereas V. Arikan [23] discussed that the triangular and tri-hexagon infill patterns perform better in terms of achieving the best mechanical properties of additively manufactured PLA samples, as compared to other infill patterns. D. Popescu et al. [24] studied fused deposition modeling (FDM) parameters for 3D printing, which clearly affect the mechanical strength of the specimens. Infill patterns are shown to improve weld efficiency in FSBW by promoting better heat distribution and consistent consolidation. T. Sadowski et al. [25] and M. Ayaz et al. [26] explained that factors like tool speed and pin profile control the heat input, material flow pattern, and microstructural evolution in the stir zone, which directly affect the weld strength and hardness of the FSW joint. A. H. Elsheikh et al. [27] demonstrated that cylindrical pin profiles produce distinct flow patterns and void distributions. However, O. Kocar et al. [28] and R. Singh et al. [29] explained in their studies that square pin geometries typically yield superior weld efficiency due to enhanced stirring actions and minimized void formation. C. Mcllroy and P. D. Olmsted [30] investigated the interdiffusion and entanglements among various layers of fused filament fabricated (FFF) samples. It was found that the joining of layers in 3D-printed samples was significantly affected by shear rates in the nozzle.

A. A. Hamza & S. R. Jalal [31] and R. Chandana & K. Saraswathamma [32] explained in their studies that the tool pin profiles have a significant impact on the final weld quality. Moreover, stationary shoulder tools were also found to perform better than traditional tools. For instance, many researchers employed a variety of pin profiles, which include cylindrical, square, hexagonal, triangular, threaded cylinder, cylindrical cam, conical, taper, pentagonal, cylindrical tools with taper, and square tools with taper geometry.

Surface morphology analysis of FSBW joints using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or optical microscopy is found to be vital in disclosing various phenomena, revealing grain structure and porosity, and evaluating the causes of low welding efficiency [5,33]. However, various other imaging techniques such as Gesellschaft für Optische Messtechnik (GOM) inspect analysis, X-ray computed tomography (CT) characterization, and coordinate measuring machine (CMM) can still offer valuable information on surface roughness, void formation, and weld integrity at the heat-affected zone (HAZ) in cases where SEM is inaccessible due to time and other constraints [7].

SEM has been widely employed in previous studies to provide microstructural evidence with the mechanical characterization of various polymers and their composite. Researchers have reported that SEM micrographs can really help identify fracture modes, void distribution, and interfacial bonding quality, which directly correlate with tensile strength and hardness outcomes [34]. For instance, SEM analysis has been used to distinguish between ductile and brittle fracture surfaces in 3D-printed thermoplastic composites, offering insight into the failure mechanisms under different process conditions [35]. Similarly, SEM images have revealed the presence of uniform material flow and reduced porosity, validating the effectiveness of optimized tool geometries and process parameters in FSW joints [36]. These findings demonstrate that SEM not only serves as a visualization tool but also acts as a critical validation method linking joint morphological characteristics with its mechanical performance.

Despite the existence of extensive research on both 3D printing and FSW of metallic and fiber-reinforced polymer composites, limited studies have addressed the welding behavior of 3D-printed metal-particles-reinforced PLA composites to resolve the size limitations of AM technologies. Particularly, no research work was found on FSW of 3PPCC where Cr is present in 10 percent by weight. This research contributes towards understanding how chromium reinforcement alters thermal generation, material flow, and interfacial bonding during friction stir welding of additively manufactured 3PPCC. Comprehending the interplay between FSBWFs, infill patterns incorporated first by 3D printing, and weld performance metrics (WT, WH, WS, and weld efficiency) may help us optimize them to probe the underlying thermo-mechanical response of the 3PPCC, as expected and highly hypothesized. This will expand the applicability of FSBW of 3PPCC in engineering fields, e.g., automotive, aerospace, and biomedical engineering, where lightweight, high-strength, large-size polymer composites are increasingly sought. However, a significant research gap still exists in the field of welding 3D-printed novel metal-particles-reinforced polymeric composites. This study aims to fill this research gap by systematically evaluating, for the first time, the influence of FSBWFs on the weld temperature, weld hardness, weld strength, weld efficiency, and microstructural integrity of 3PPCC.

2. Materials and Methods

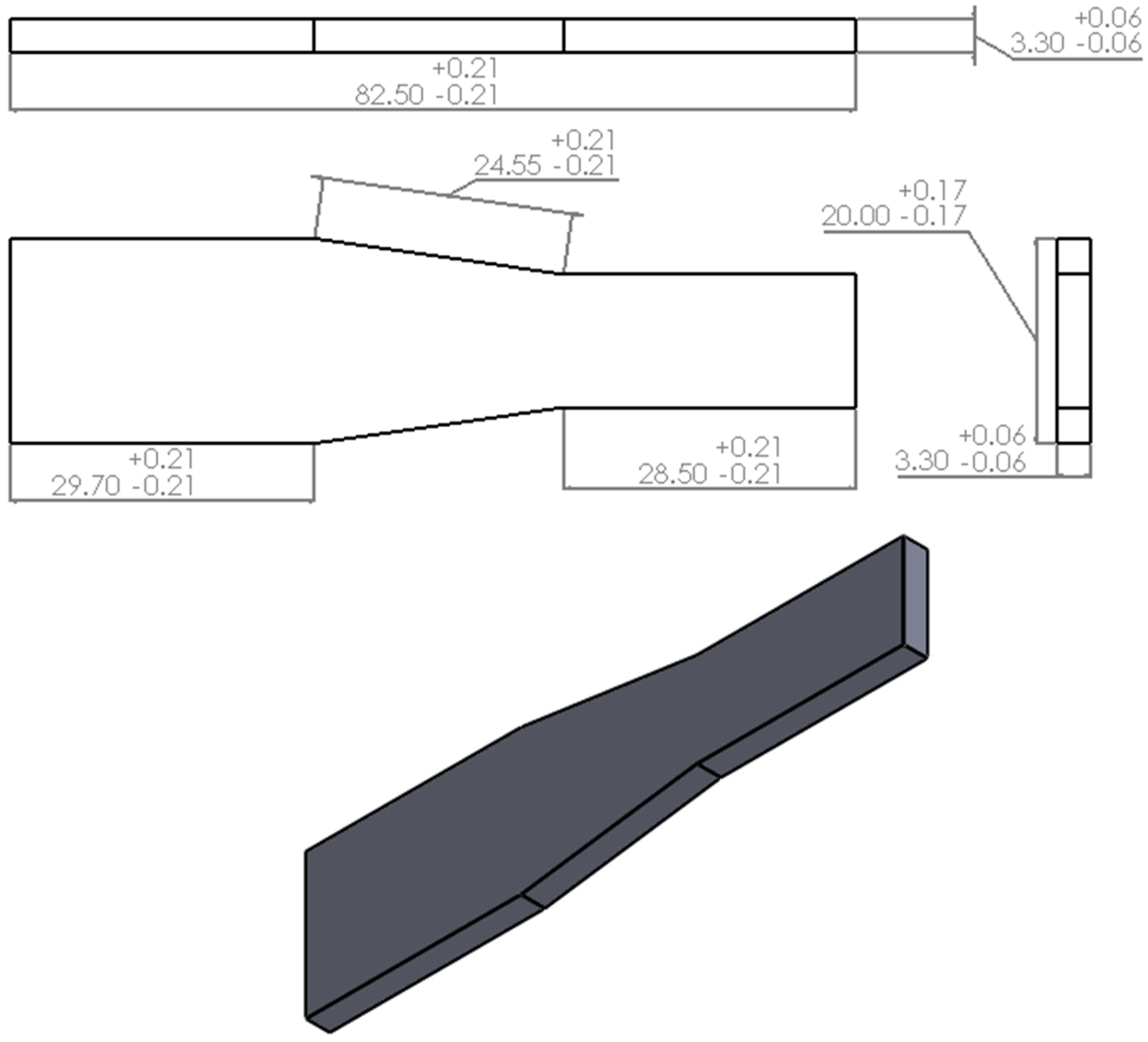

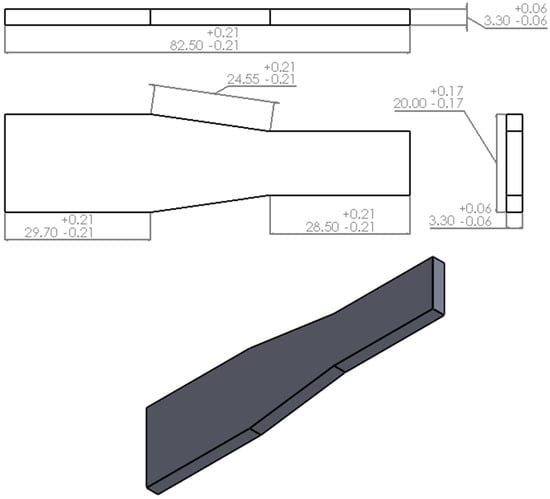

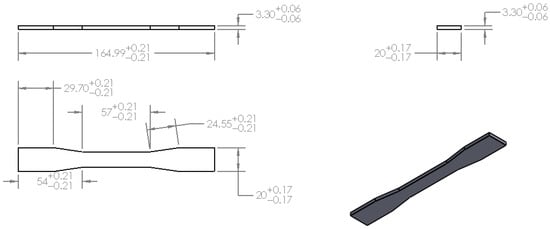

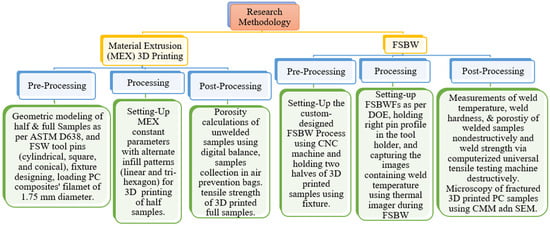

This research presents a comprehensive empirical investigation into the joining and morphological behavior of 3D-printed PLA-Chromium (10% by weight) (PC) composites (3PPCC) subjected to friction stir butt welding (FSBW). The filament of 3PPCC was manufactured and supplied by Shenzun Eryone Technology, Shenzhen, China. The size range of Cr particles embedded in PLA ranges from 800 to 8000 nm. 3PPCC filament has a diameter of 1.75 mm. Polylactic acid (PLA) was selected as the base matrix polymer for its biodegradability, printability, and relevance in additive manufacturing, while chromium particles were introduced in PLA as a reinforcement to enhance the thermal and mechanical properties of 3PPCC. Chromium was selected due to its higher thermal conductivity, stiffness, and wear resistance, which are expected to modify local heat generation, frictional behavior, and stress transfer within the heat-affected zone (HAZ) of 3PPCC. Thermal and mechanical properties of both PLA and Cr are shown in Table 1. 3PPCC specimens were fabricated in two halves, as shown in Figure 1, using material extrusion additive manufacturing (MEX), following ASTM D638 standards for tensile test geometry, as shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Thermomechanical Properties of both PLA and Chromium.

Figure 1.

Half Specimen Based On ASTM D638 (to be welded) (All Dimensions in mm).

Figure 2.

Full Specimen Based On ASTM D638 After FSBW (All Dimensions in mm).

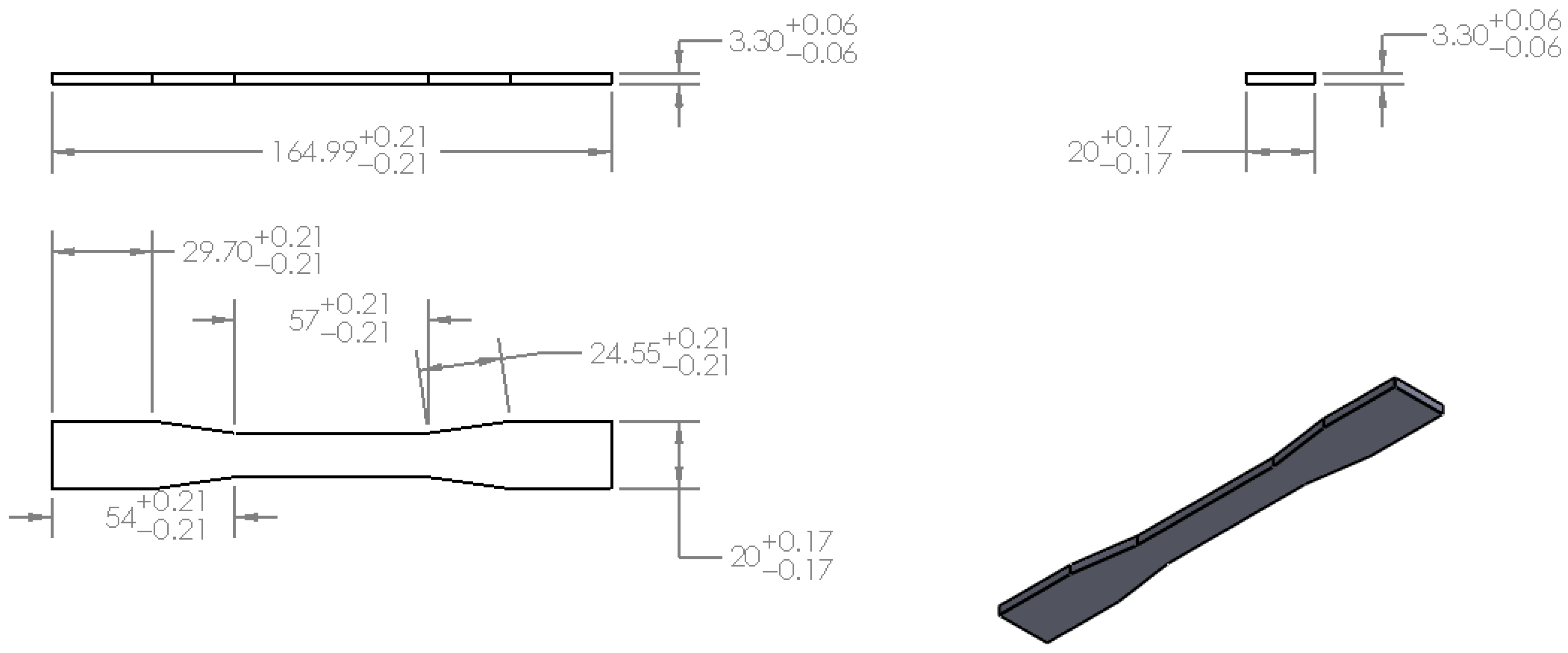

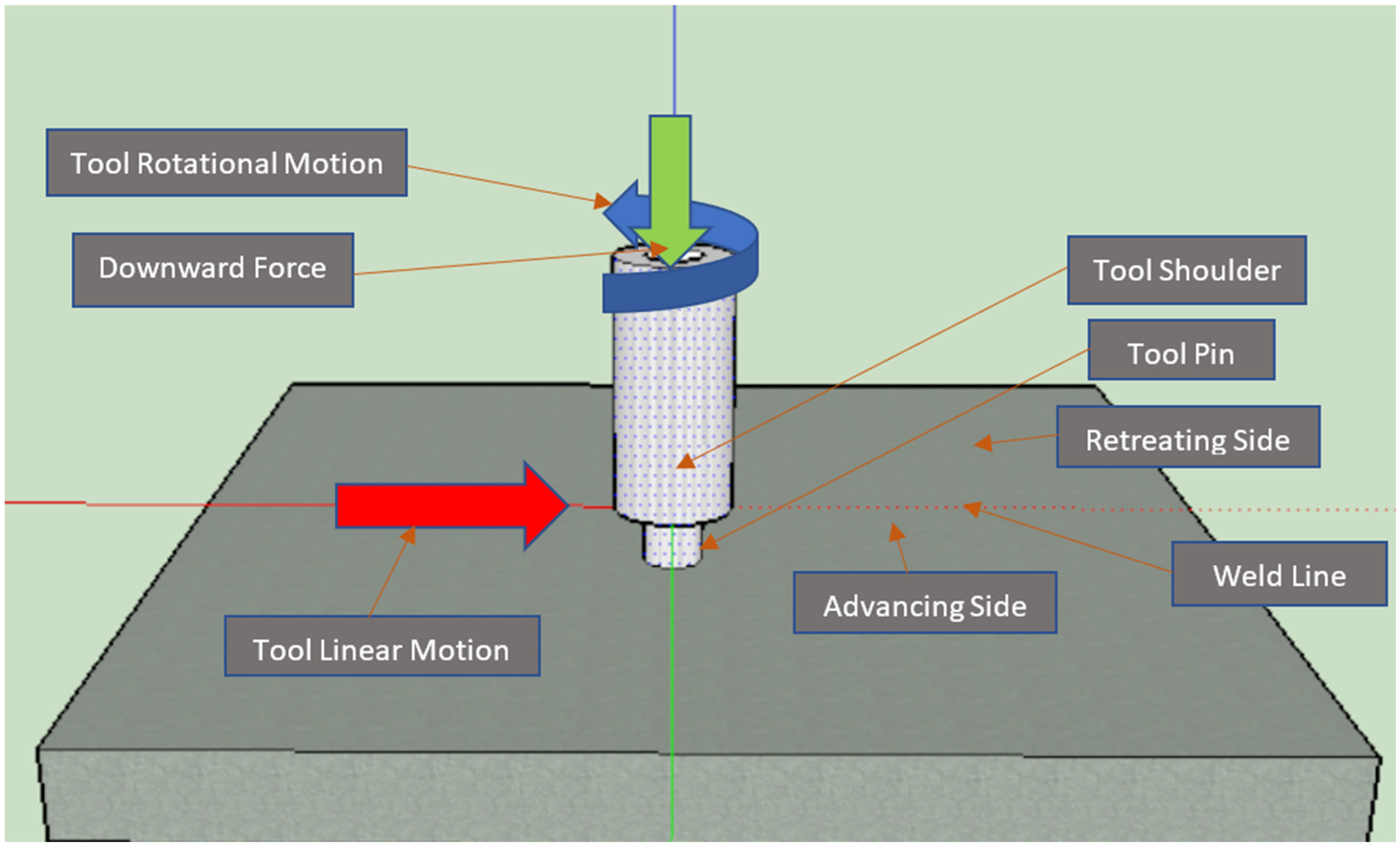

All the specimens were printed using MEX 3D printer parameters such as layer height of 0.2 mm, extrusion temperature of 200 °C, line width of 0.4 mm, printing speed of 60 mm/s, infill density of 100%, and two contours. The selection of MEX parameters is based on an undergraduate project delivering optimal tensile strength for the 3PPCC. The FSBW process, as shown in Figure 3, was customized, as shown in Figure 4, using a numerically controlled computer (CNC) machining center where the movement (i.e., rotational) of FSW tools and movement (i.e., translational) of 3D-printed specimens were deployed by employing and varying a CNC program.

Figure 3.

Friction Stir Butt Welding (FSBW).

Figure 4.

FSBW of 3PPCC Samples Using CNC Machining Center.

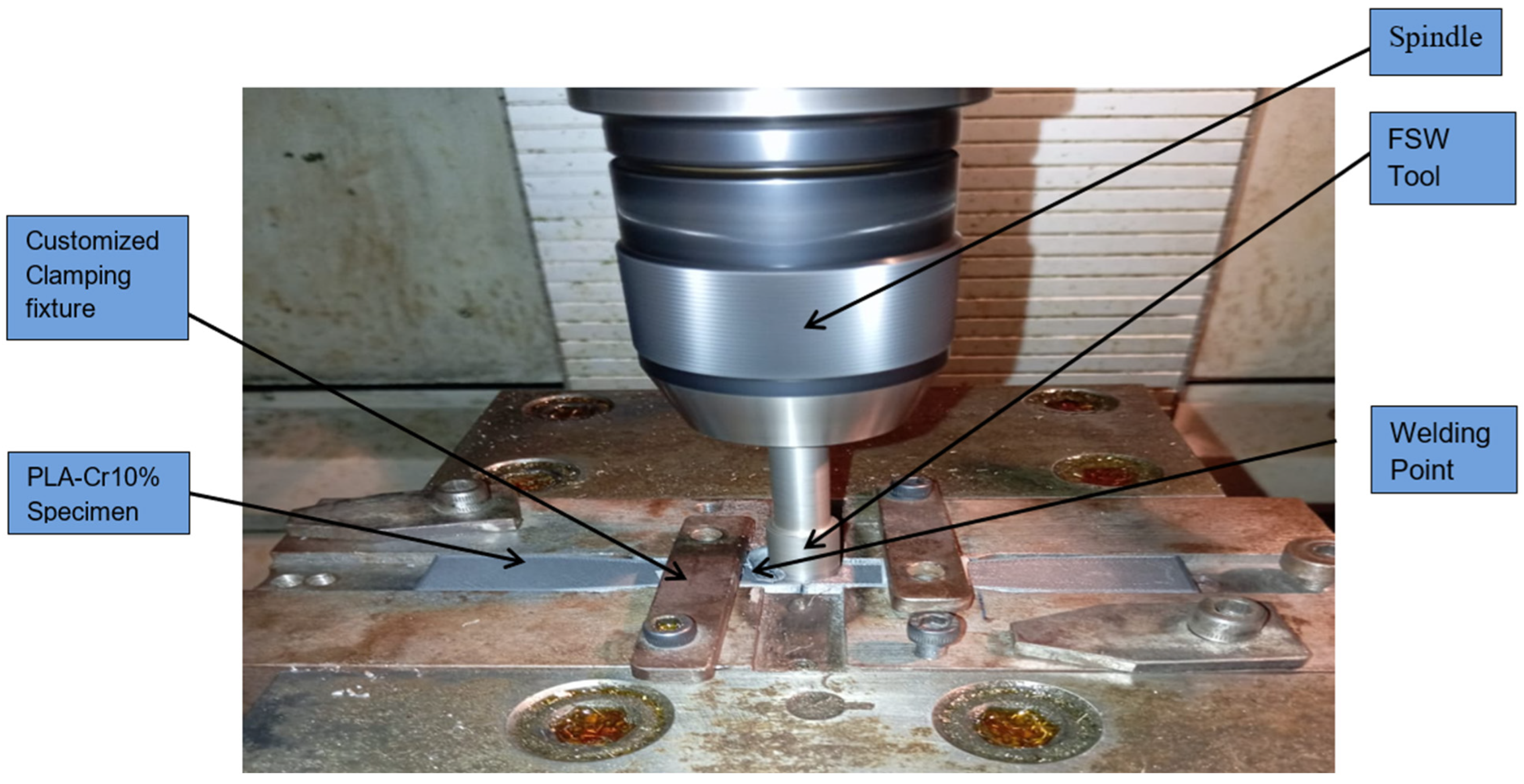

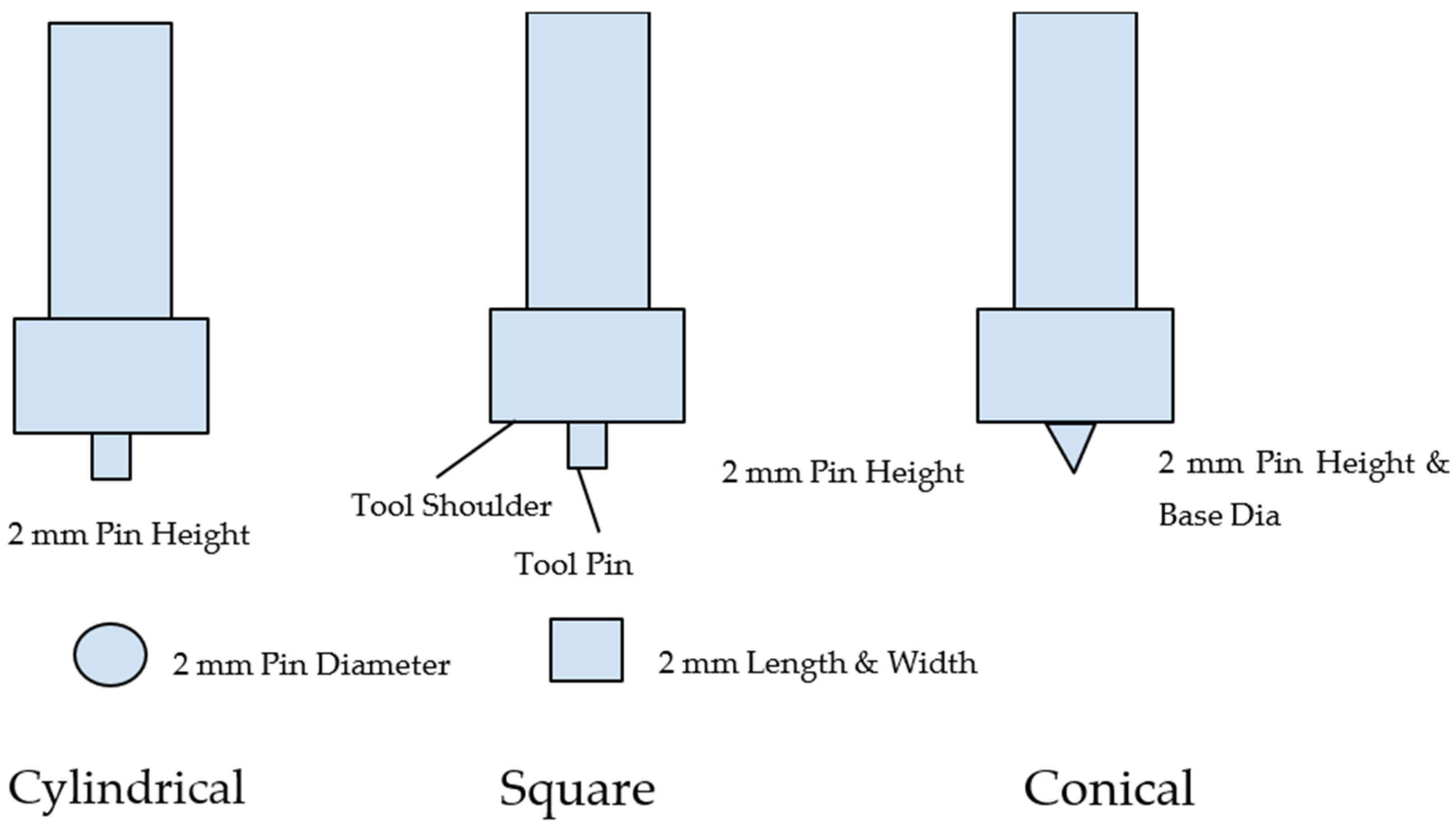

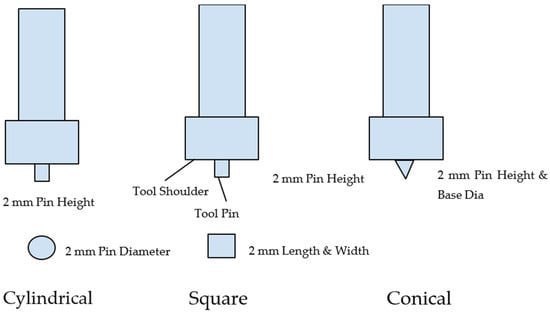

Three FSBWFs were used, namely tool rotational speeds (TRS) (1800, 2000, 2200 rpm), tool traverse speeds (TTS) (8, 10, 12 mm/min), and tool pin geometries (square, cylindrical, and conical) of M2 high-speed steel (HSS), as shown in Figure 5 and Table 2. Selection of these FSBWFs and their levels was based on the literature [10,28,37,38,39] and ensured by preliminary experimentation for their effectiveness towards better weld quality. Design of experiments (DOE) based on an L9 orthogonal array was employed using the Taguchi approach to systematically optimize three friction stir butt welding factors (FSBWFs), as shown in Table 3, for three output parameters, namely WT, WH, and WS. Revolutionary pitch (RP) was also calculated by using TRS and TTS. RP is a ratio of TRS (numerator) and TTS (denominator) imparting a practical understanding of the FSBW tool’s complex motion in terms of revolutions per millimeter (RPMM) during FSBW of 3PPCC.

Figure 5.

FSBW Tool Pin Profiles.

Table 2.

FSBWFs’ Levels.

Table 3.

Design of Experiments (DOE) for FSBW of PLA–Cr Composites.

Joint performance was assessed in terms of WT, WH, and WS measurements, while weld efficiency was also calculated relative to unwelded 3D-printed specimens. WT was measured during FSBW of 3PPCC using a thermal imager, as shown in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Information File (SIF). Emissivity value was assigned to be 0.87 for 3PPCC in the thermal imager at room temperature before taking thermal images. Moreover, the WT and WH were measured first, as both output parameters are nondestructive to welded 3PPCC samples. An ultimate tensile strength (UTS) testing machine was used later to measure the WS of FSBW joint by keeping constant both the nominal strain rate at 0.1 mm/mm·min and speed of testing at 5 mm/min. Additionally, WT and WS were intended to be higher, whereas WH was intended to be lower, to ensure the desired joint quality in terms of its enhanced strength and reduced brittleness, respectively. The Taguchi method describes these higher and lower responses’ qualities in terms of S/N ratio to be “larger the better” and “smaller the better”. The following Equations (1) and (2) are employed to ensure these quality characteristics.

Larger the better∶ S∕N = −10 × log(Σ(1∕Y2)∕n)

Smaller the better∶ S∕N = −10 × log(Σ(Y2)∕n))

Moreover, the total DOEs would be equal to 27 considering the three control factors (FSBWFs) and their three levels (i.e., full factorial) if Taguchi L9 array were not employed. However, the L9 Taguchi array has fewer degrees of freedom, which prevents us from investigating higher-order interaction/combined effects among the factors’ levels. Hence, three-way interactions were not discussed as a limitation to Taguchi orthogonal arrays.

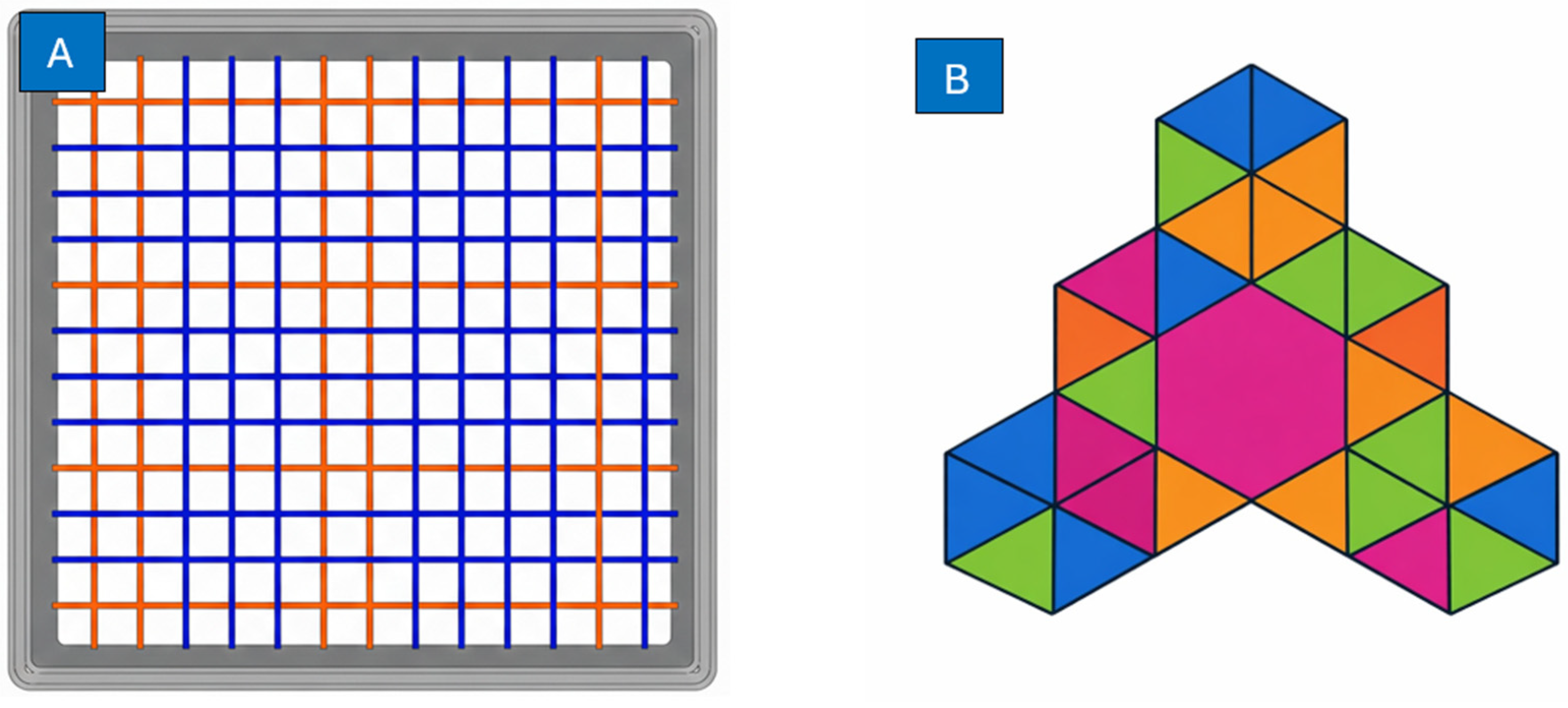

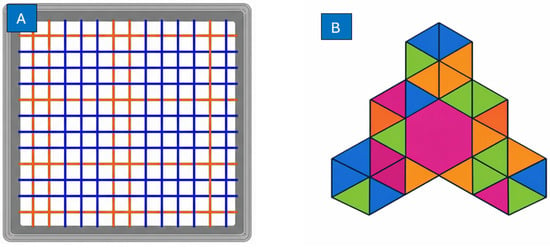

Moreover, two distinct infill patterns, e.g., linear and tri-hexagonal, were incorporated in 3D-printed samples during the samples’ fabrication to assess their potential effect on weld/joint performance, as shown in Figure 6A,B. Therefore, Table 3 was followed twice considering these two infill patterns, one by one, resulting in DOEs of 18 experiments. Each DOE was repeated two times, thereby resulting in a total of 36 experiments.

Figure 6.

(A) Linear Infill Pattern (B) Tri-Hexagonal Infill Pattern.

The Shore D hardness of each 3PPCC sample was measured at three different locations within the welded zone as per ASTM 2240–15 at room temperature, and an average value was computed for each experimental condition. Moreover, a Gibitre Durometer, provided by Gibitre Instruments, Bergamo, Italy, was utilized to measure WH.

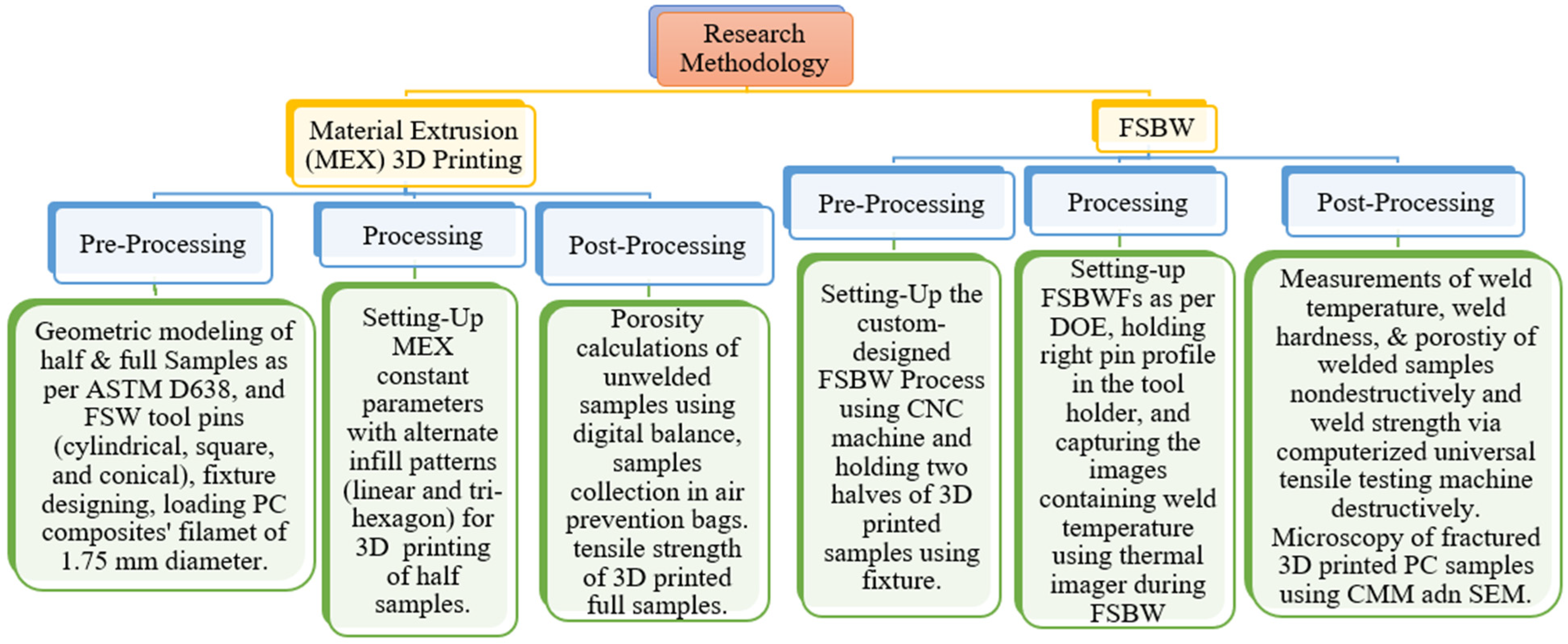

The initial surface of unwelded 3PPCC samples was analyzed using a coordinate measuring machine (CMM) (supplied by Precise Technology Co., Ltd, Kaohsiung Hsien, Taiwan) at 10× magnification, allowing visual inspection of voids, material flow, and weld uniformity for all welded samples. A deeper microstructural characterization of the selected samples, specifically those with the highest and lowest weld strengths, was conducted using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (microscope supplied by Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH. Carl-Zeiss-Promenade Jena, Germany) and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) (spectroscope supplied by AMETEK company, Mahwah, NJ, USA). These analyses provided vital insight into material bonding, particle dispersion, interfacial defects, and elemental composition within the weld zone, enriching the meaningful interpretation of results in terms of weld integrity. A flow diagram showing the research methodology of the current study is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Research Methodology for MEX 3D Printing and FSBW.

Moreover, regions showing elevated temperature exposure, altered surface texture, intersection of welded and non-welded zones, and microstructural modification at bonded locations of 3PPCC were classified as HAZs. The HAZs were determined by evaluating both real-time surface temperature measurements captured by a non-contact thermal imager during welding and post-weld surface morphology variations observed through CMM and SEM analyses.

3. Results and Discussion

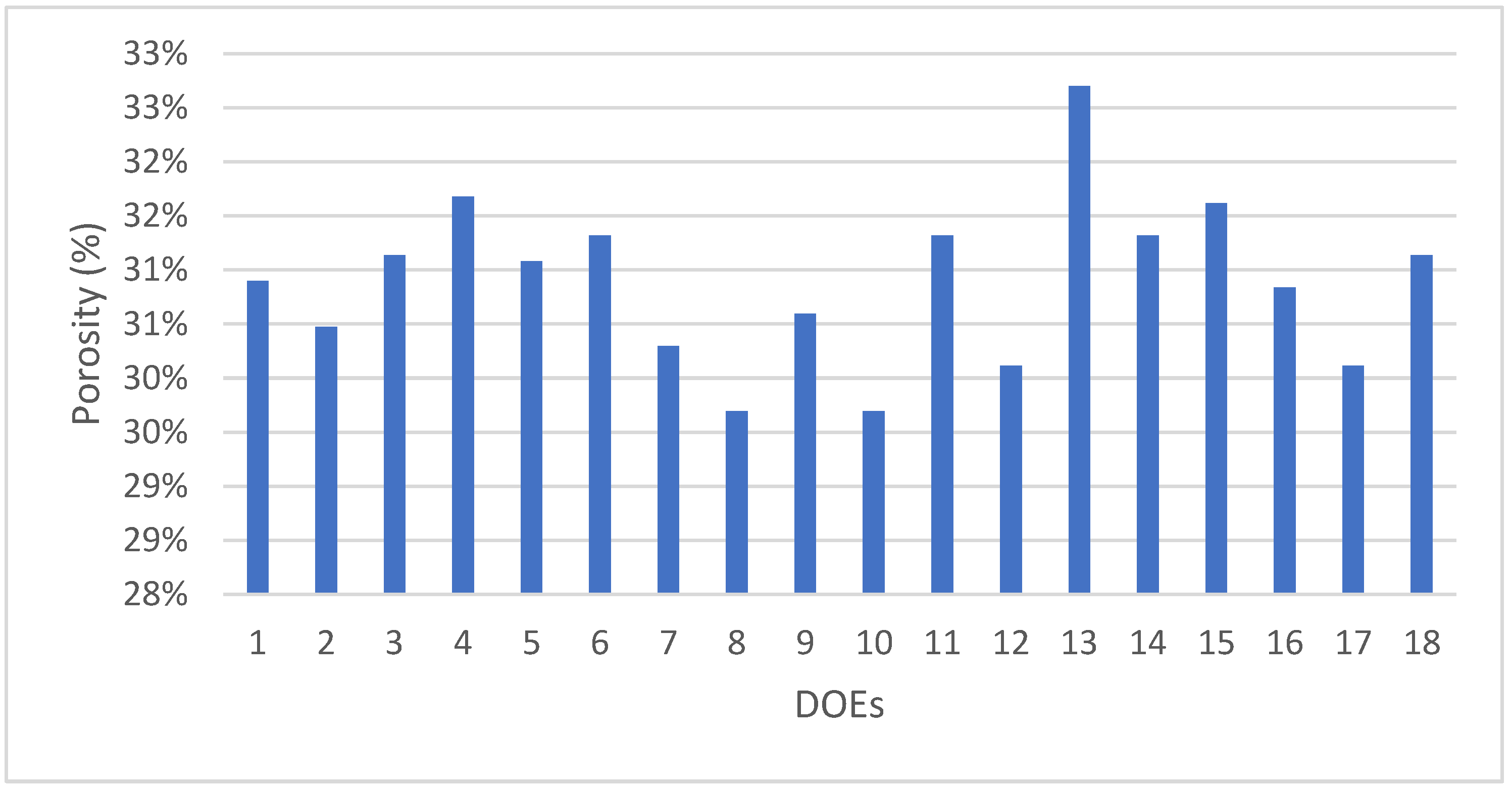

3.1. Porosity

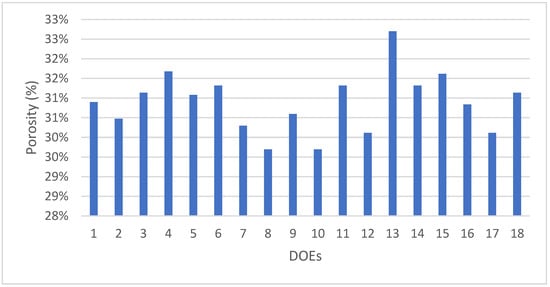

Porosity percentages of 3PPCC samples were calculated before FSBW by using Equation (3). In Figure 8, the first nine 3PPCC samples represent the linear infill pattern, while the tri-hexagonal infill pattern is represented by the 3PPCC samples numbered from 10 to 18. Overall, the porosity was found to range from 30% to 33% for all 18 3PPCC samples. The porosity of tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC samples was slightly higher than that of the samples with the linear infill patterns. Moreover, it is expected that the highly porous tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC samples, such as sample 13, may result in lower WS and vice versa for samples with lower porosity, e.g., sample 8, which is linearly infilled 3PPCC.

Porosity (%) = [1 − (Density of printed PLA90% + Cr10%/Density of Virgin PLA90% + Cr10%)] × 100

Figure 8.

Porosity Percentages For Each DOE Before FSBW.

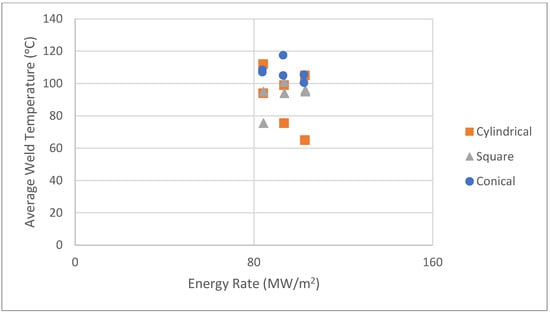

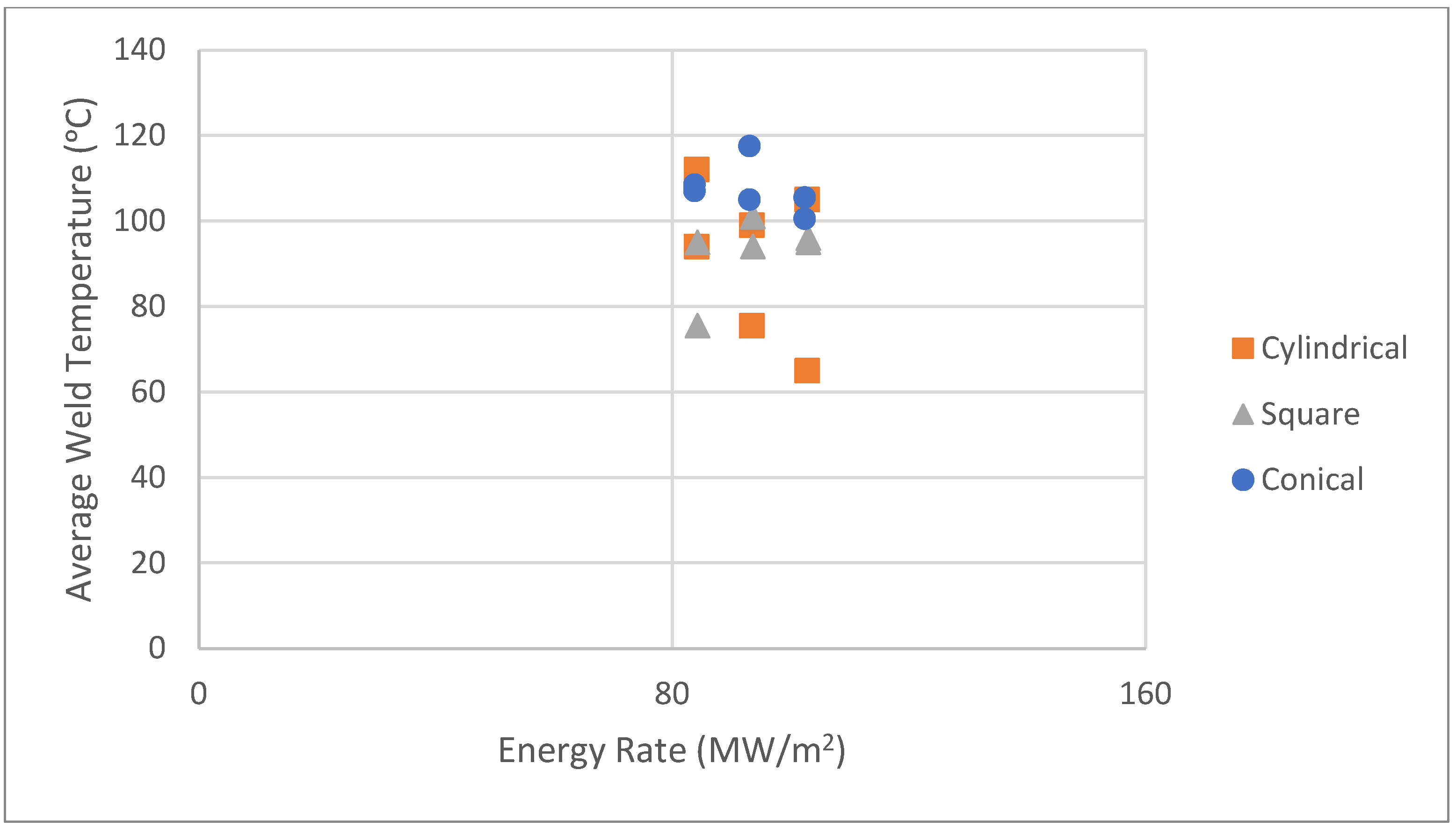

3.2. Weld Temperature (WT)

From Table 4, the recorded weld zone temperatures fall within the range of approximately 65–117.5 °C, indicating that the friction stir butt welding (FSBW) process for 3PPCC generated moderate frictional heating relative to metallic FSBW for each of the 18 experimental runs. WTs are well below the melting point of PLA (i.e., 180 °C), confirming that the joining process remained in a solid-state regime, as intended. Moreover, the temperature range found was either equal to or well above the glass transition temperature of PLA (i.e., 65 °C). At the glass transition temperature (Tg), the polymers usually change their state from solid to rubbery without being melted. Having attained the Tg of PLA is again a good sign during FSBW for each experiment to properly stir the 3PPCC, which has chromium particles as well. Hence, it is now evident that the WT results confirm the true spirit of FSBW, which must be ensured for obtaining optimized FSBW.

Table 4.

Weld Temperature Observed.

In addition, the melting point of chromium is 1860 °C, and it has better thermal conduction than that of PLA. For this reason, the average WT range obtained is exceptionally desirable, and chromium clearly helped the PLA matrix achieve this range as one outcome of FSBW.

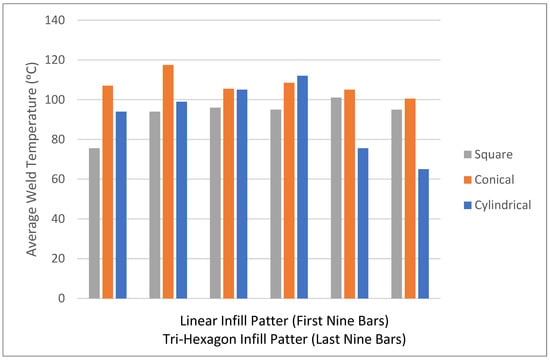

The highest WT recorded was 117.5 °C (i.e., for sample 5 with 2000 rpm, 10 mm/min, conical, linear infill) indicating the strong heat generation capability of conical pins. The lowest observed WT was 65 °C (i.e., for sample 17 with 2200 rpm, 10 mm/min, cylindrical, tri-hexagonal infill), highlighting a potential under-heating condition that could compromise weld integrity.

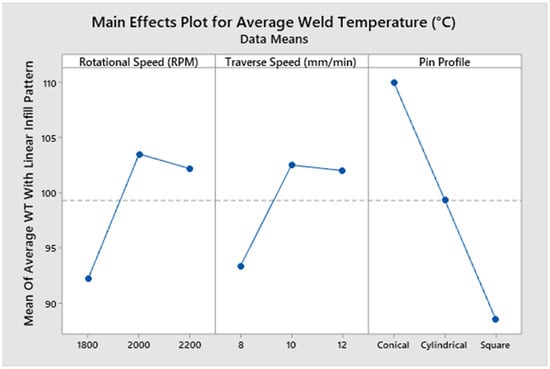

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the linear infill pattern for WT indicated that the pin profile (PP) had the most significant influence among the three FSBWFs, with a p-value of 0.017, well below the 0.05 threshold, as shown in Table 5. This confirms that tool pin geometry plays a decisive role in supplying the proper heat input during FSBW, as PP geometry directly affects material flow, frictional contact area, and stirring efficiency.

Table 5.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of linear infill pattern for weld temperature.

Tool rotational speed (TRS) yielded a significant effect, with p-value = 0.05, suggesting its practical implications in terms of heat generation, though its contribution was less dominant when compared with PP, as could also be seen in the percent contribution (PCR) column of Table 5. Conversely, TTS produced a p-value of 0.070, which is greater than 0.05, indicating that its effect on WT was statistically insignificant considering the test conditions of Table 4. The relatively low error value further validates the independent effects of FSBWFs on WT, demonstrating that most of the variations in WT are independently attributable to the FSBWFs. Overall, the results establish that weld zone heating in linear infilled 3PPCC is primarily governed by pin profile, with rotational speed providing secondary adjustments and traverse speed having minimal impact on WT.

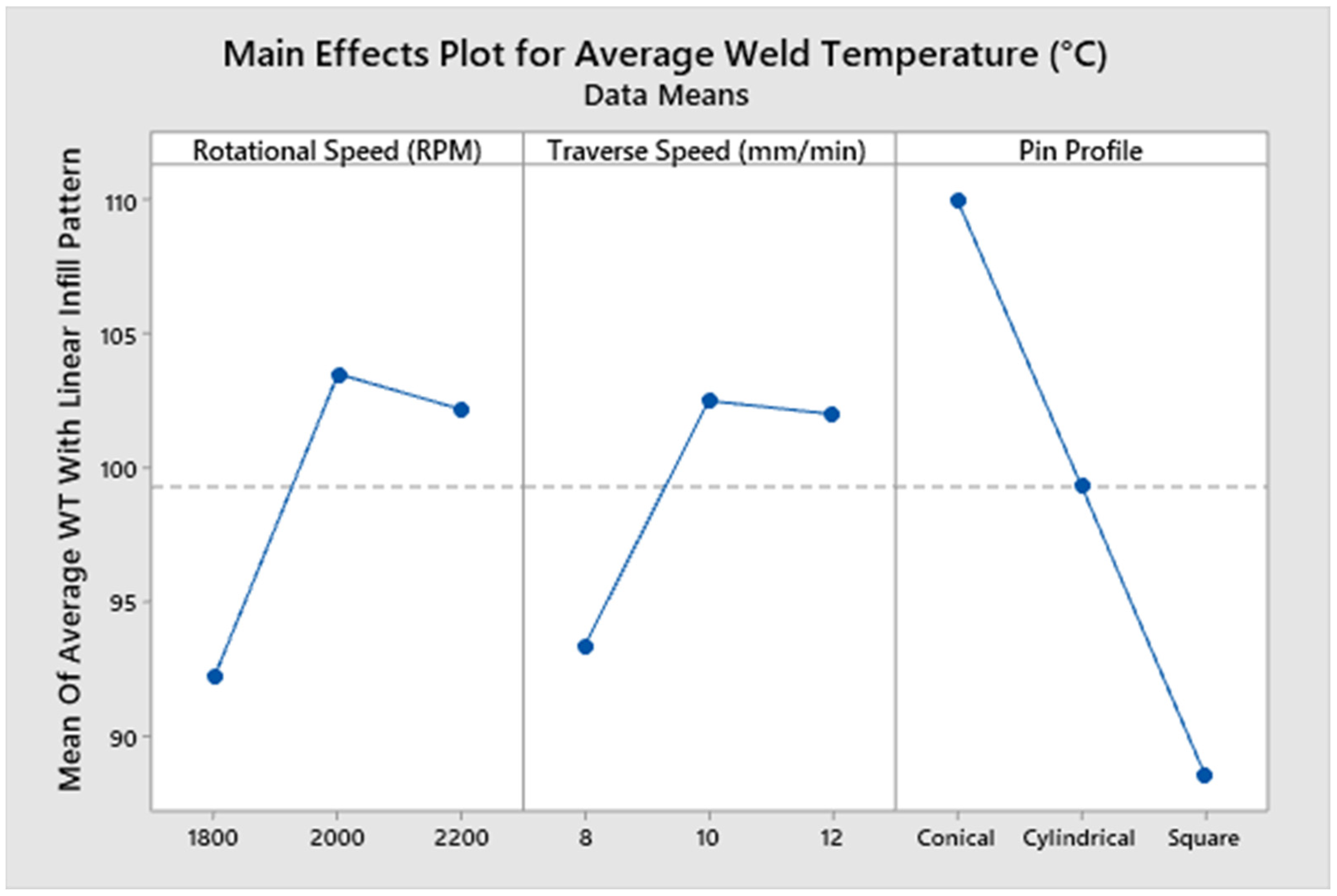

In Figure 9, the main effects plot reveals distinct influences of the FSBWFs’ levels with linear infill conditions for average WT. The optimal level of TRS was found to be 2000 RPM, where maximum WT could be obtained while welding 3PPCC samples. In contrast, the optimal TTS to ensure maximum WT at the welding zone was found to be 10 mm/min. These optimal TRS and TTS values are moderate levels capable of delivering the optimal WT, as desired for optimal weld quality at the weld zone. Generally, during FSBW, it is anticipated that a WT strictly higher than the glass transition temperature of PLA (65 °C)—a matrix polymer of 3PPCC [1]—and lower than its melting point (180 °C) [1] will be attained. Among the PPs, the conical tool produced the highest temperatures, likely owing to its tapered geometry, which helped the tool gradually increase pressure on the path/line of the weld zone with a better local concentration of enhanced interfacial friction. Additionally, the 3D slope of the conical pin initiated rapid dynamic changes in temperature and molecules of PLA composites while the conical PP moved along the weld line. The cylindrical PP generated moderate heat, while the square PP yielded comparatively lower temperatures, possibly due to their flat faces promoting more efficient material movement rather than heat buildup. This is due to the static volumes of the cylindrical and square pins, which are larger than that of the conical pin, implying further that the volume swept or moved per rotation of the tool pin is higher in the case of the cylindrical and square pins, as evaluated in Table 6. These trends underscore the critical role of pin geometry and TRS in controlling thermal profiles, with TTS acting as a regulating factor.

Figure 9.

Main effects plot for average WT with linear infill pattern.

Table 6.

Swept ratios for different PPs.

Managing these FSBWFs is essential to achieve sufficient material plasticity without exceeding the thermal decomposition/depolymerization threshold of the PLA–chromium composite, which start above 282 °C [1].

The ANOVA results for WT with the tri-hexagonal infill pattern show that none of the effects from the investigated FSBWFs were statistically significant, as shown in Table S1 of SIF. The p-values for rotational speed (0.447), traverse speed (0.547), and pin profile (0.392) are all greater than 0.05, confirming that the variations in WT due to these FSBWFs were not significant when the tri-hexagonal infill configuration was incorporated in the 3PPCC samples.

The main effects plot considering the tri-hexagonal infill pattern is shown in Figure S2 of SIF for average WT. The main effects reveal notably different thermal behavior as compared to the linear infill configuration. The most striking observation is the relative stability of the WT across varying FSBWFs, indicating that the tri-hexagonal infill architecture itself plays a dominant role in regulating heat distribution. TRS shows a less pronounced effect on temperature, with its optimal level found at 1800 RPM, suggesting that the complex internal structure of the tri-hexagonal pattern dissipates heat more effectively, thereby dampening the influence of rotational velocity above 1800 RPM. This implies that excessive as well as unnecessary heat input at the HAZ is greatly controlled by the tri-hexagonal structure within 3PPCC samples. Similarly, TTS exhibits a minimal impact on thermal gradients in the weld zone, as the interconnected nature of the tri-hexagon design promotes uniform heat transfer regardless of the tool’s increasing travel rate. Optimal TTS was found to be 8 mm/min. Regarding PPs, while some variations exist, the differences in temperature due to conical, cylindrical, and square tools were less extreme than those seen in linear infill samples. This attenuated response underscores the ability of the tri-hexagonal pattern to mitigate localized detrimental heating effects, resulting in a more stable and desired thermal environment. Overall, the conical pin produced the maximum WT and hence should be deduced as the optimal pin profile. The geometry of the conical pin is extremely different from that of other tool pin profiles, like the square and cylindrical geometries. Firstly, there is no geometrical irregularity present in a conical pin, which varies perpetually along its length/height. This originates the thermal gradients within the weld zone at its best, as compared to those from other PPs. The conical PP was also found to be optimal due to its thermal support for heat deficiencies if they occurred due to low levels of both TRS and TTS. Overall, the optimal FSBWFs observed (1800 rpm, 8 mm/min, and conical PP) can guarantee the superior thermal stability conferred by the tri-hexagonal infill, reducing sensitivity to variations in FSBWFs and promoting consistent weld quality.

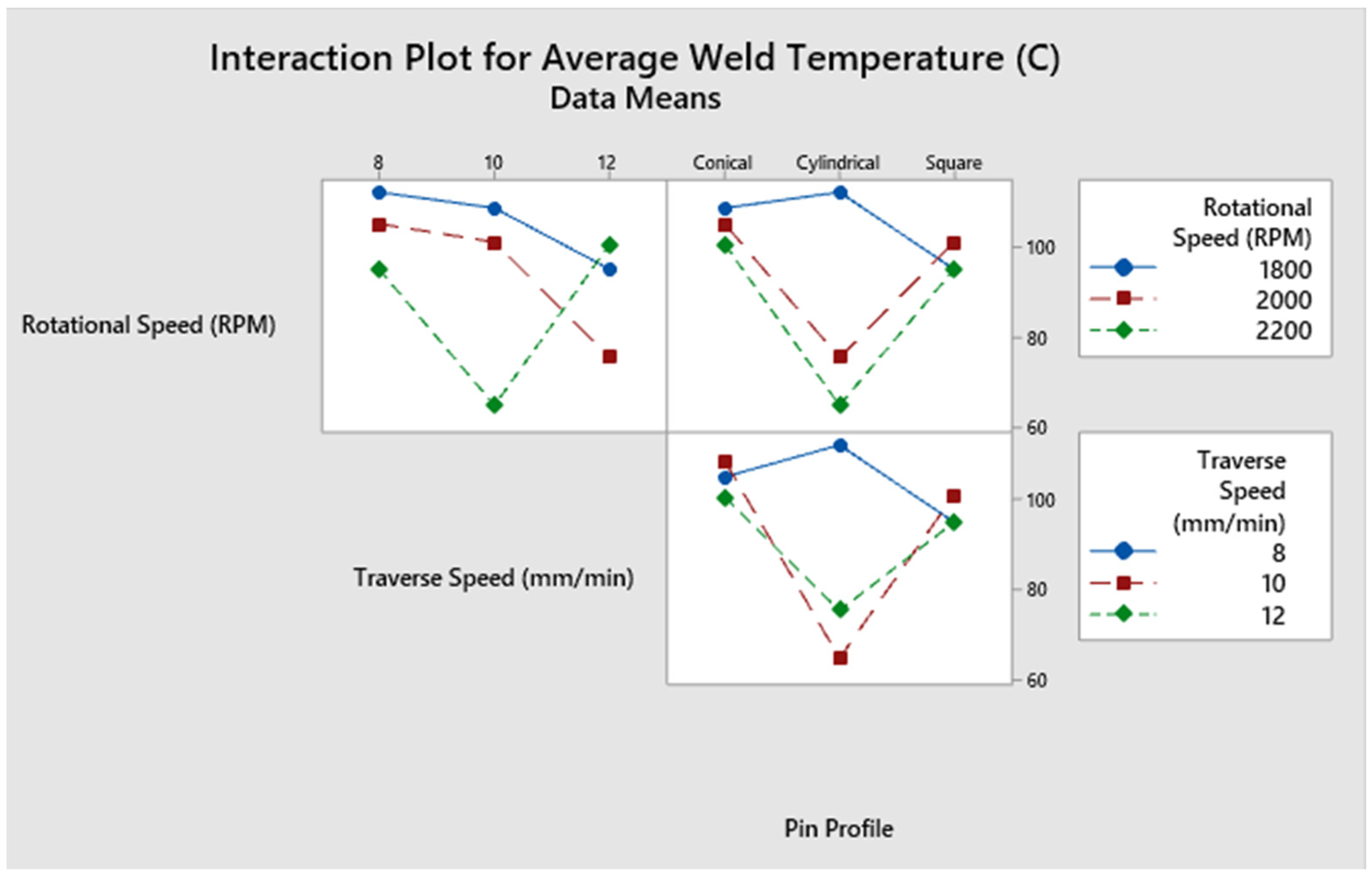

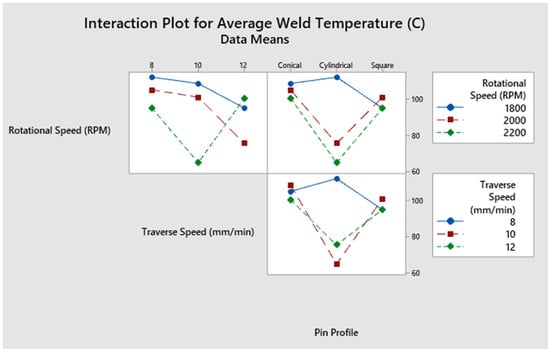

The error PCR was deduced to be 21.67, as compared to those of independent FSBWFs, suggesting that the temperature distribution, however uniform, in tri-hexagonal samples was less sensitive to independent FSBWF fluctuations than those with linear infill structures where the error PCR was negligibly low, i.e., 1.1. This calls for investigating the interaction plots [40,41,42], as shown in Figure 10, for the tri-hexagonal infill pattern with due consideration for the dependent effects of FSBWFs on WT. Therefore, unlike the linear infill case, where PP was dominant, the tri-hexagonal infill pattern demonstrated inherent stability when deeming the simultaneous FSBWF effects by combing their effects due to insignificance of independent FSBWF effects on WT.

Figure 10.

Interaction plots of average WT for tri-hexagonal infill pattern.

As shown in Figure 10, the interactions among three FSBWFs are plotted for the tri-hexagonal infill pattern. It is pertinent to mention here that an interaction effect of the severity index (SI) above 80% is thought to impact WT considerably. In other words, the interaction effect of any FSBWF will be significant/severe if the SI is found to be either equal to or greater than 80%. The severity index is defined as the ratio of the angle between the lines of interacting factors in the interaction plot to a 90° angle when multiplying the resulting fraction of the ratio by 100. For instance, the SI is 100% if the interaction angle is found to be exactly 90° between the lines of interacting factors. This percentage appears to be less than 100% if the angle between interacting lines is less than 90°. Parallel lines have an intersection angle of zero between them, implying no interaction or combined effect. However, nonparallel lines intersect each other at some angle. The closer the angle is to a value of 90°, i.e., an the case of perpendicular intersecting lines, the greater will be the severity of interaction. For SIs above 80%, it is found that two levels (1800 and 2000) of TRS severely interact with a TRS of 2200 rpm at a TTS of 12 mm/min. This implies that moderate levels of TRS, when combined with higher levels of TTS, impart the desired WT necessary for an optimal bond. The interaction effect is also known as the combined effect of various levels of at least two FSBWFs,, e.g., TRS and TTS in this research. A likely explanation of this interaction effect is that the right combination of levels of both TRS and TTS are essential from two perspectives. Firstly, this is the spirit of actual FSBW. Second, the joint quality is ensured optimal as a result of right levels’ selection of TRS and TTS. This also suggests that TRS must be assigned a level in controlled manner without setting its extreme level, i.e., 2200 rpm, however, in combination with 12 mm/min can guarantee optimal WT and weld joint with tri-hexagonal infill pattern. This is due to this reason that error PCR was found to be 21.67% as per Table S1 of SIF verifying that the FSBWF are having sever interactions among their levels in affecting WT during FSBW.

As far as the interaction between PPs and TRS is concerned, cylindrical and square pins at 1800 mm/min are found to be interacting severely with higher levels of TRS, i.e., 2000 rpm and 2200 rpm towards affecting optimally WT. This indicates that PPs perform outstandingly in terms of attaining optimal WT without degrading 3PPCC required for FSBW when TRS is kept at its lowest level, i.e., 1800 rpm. This is also confirmed from the main effects for WT, as shown in Figure S2 of SIF. Moreover, similar interactions were also found among the same PPs and all TTS values, with the extra recommendation of keeping TTS lower while performing FSBW of 3PPCC, i.e., 8 mm/min, as confirmed from Figure S2 of SIF. Overall, maintaining WT in the range of 90–105 °C appears most favorable for obtaining sufficient polymer softening and bonding, and avoiding oxidative degradation of 3PPCC. Interaction plots, as shown in Figure 10, also infer that the conical pin profile raises WT substantially, which can improve mixing but risk degradation, whereas the square and cylindrical pins achieve controlled heating with stable weld quality. Moreover, the swept ratios were higher for both the cylindrical and square pins (please see Table 6), as compared to the conical pin, and the sweeping of 3PPCC was better than that achieved with the conical pin (with a lower swept ratio). Hence, the resulting joint health is also expected to be better in the case of cylindrical and square pins. Overall, the tri-hexagonal infill lowers the heat input due to reduced resistance, while the linear infill promotes higher frictional heating, as shown in Table 4 for WTs. Furthermore, the heat input seems optimal with the conical pin profile when considering it independently, and the other two PPs (cylindrical and square) are also deemed optimal in terms of the combined or interaction effects of FSBWFs on WT.

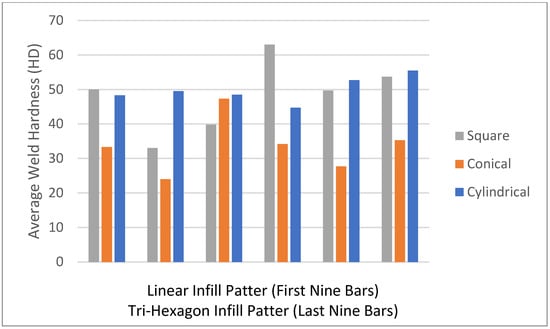

3.3. Weld Hardness (WH)

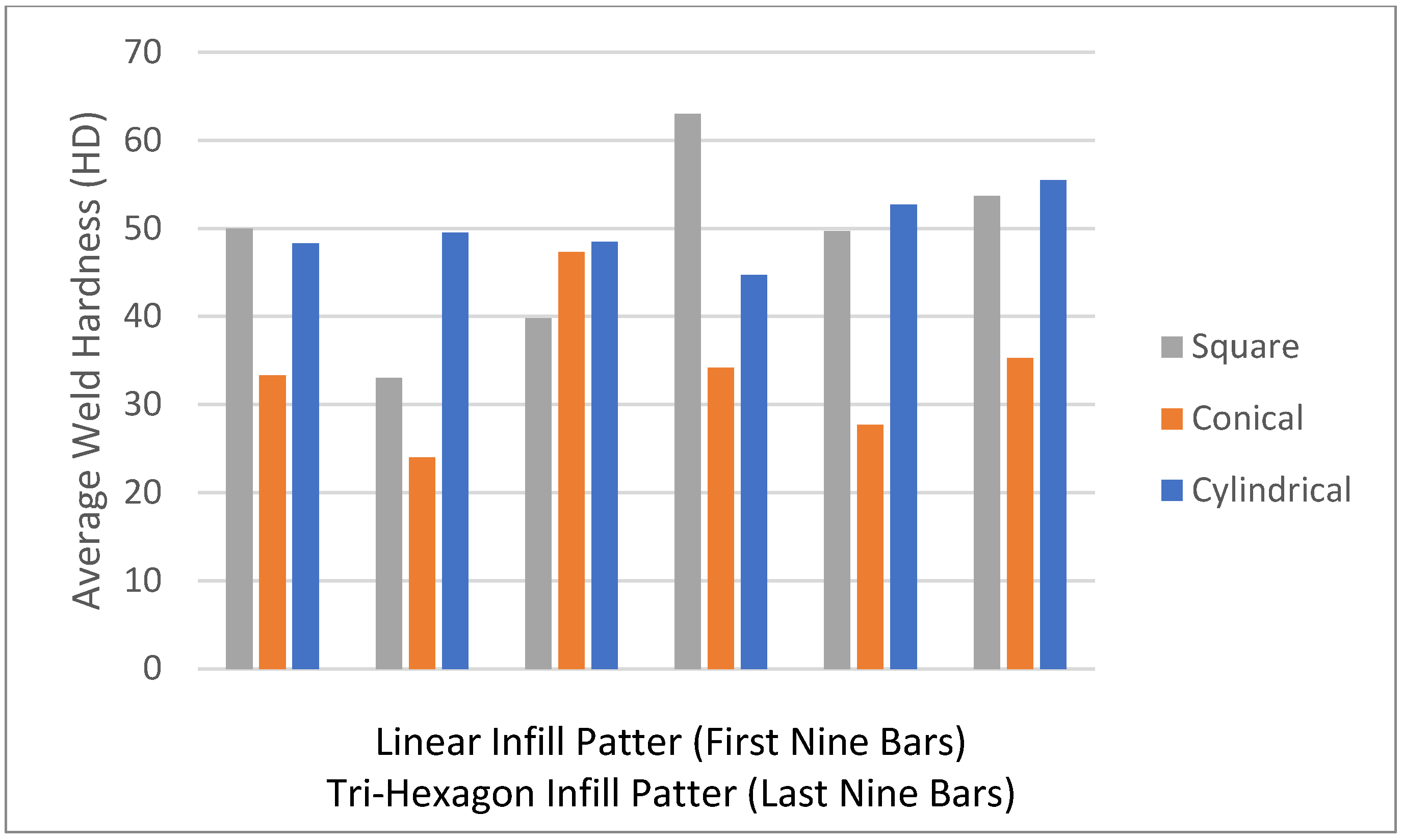

Hardness analysis of FSBW of 3PPCC joints was conducted to evaluate the impact of FSBWFs on weld quality, as shown in Table S2 of SIF. Weld hardness was varied significantly by experimental conditions based on TRS, TTS, PP, and infill pattern. The highest hardness at Shore D (HD) was observed to be 63 HD in 3PPCC joints by employing 1800 rpm, 12 mm/min, square PP, and the tri-hexagonal infill pattern, indicating enhanced material mixing and better interfacial bonding. The lowest hardness was recorded as 24 HD for 3PPCC welds using 2000 rpm, 10 mm/min, conical PP, and the linear infill pattern, suggesting inadequate material flow and insufficient consolidation.

Average hardness of unwelded specimens with the linear infill pattern was 53 Shore D, and for the tri-hexagonal pattern, it was 55 Shore D.

The results further showed that specimens fabricated with tri-hexagonal infill patterns generally retained higher hardness compared to those fabricated with linear infill patterns. For example, the sample welded with a square PP and tri-hexagonal infill pattern reached 115% hardness retention as compared to the hardness of unwelded 3PPCC, whereas its linear infill counterpart only reached ~46%, as shown in Table S2 of SIF. This suggests that tri-hexagonal structure provides better stress distribution and enhanced resistance against localized softening during FSBW.

The ANOVA results, as shown in Table S3 of SIF, reveal that all three FSBWFs exert a statistically significant influence on average WH with the linear infill pattern. The p-values for TRS (0.047), TTS (0.032), and PP (0.027) were below 0.05, confirming their significant effects on WH. Among these FSBWFs, the highest PCR of 40.82% was found for PP, indicating that tool geometry plays the most dominant role in obtaining optimal WH, followed by TTS (PCR = 34.80%), and TRS (PCR = 23.24%). These results demonstrate that the impact of linear infilled 3PPCC with other FSBWFs on WH is highly sensitive to its lowest value, which makes it less brittle, particularly to the choice of FSBWF levels that govern material flow, compaction, and reinforcement distribution during FSBW of 3PPCC. The choice of optimal levels of FSBWFs is usually indicated and determined by the main effects plot, as shown in Figure S3 of SIF. The main effects show that the optimal levels of FSBWFs should be selected as 2000 rpm for TRS, 10 mm/min for TTS, and conical PP to minimize the weld hardness when a linear infill pattern is imparted in 3PPCC.

It should be noted here that the optimal levels of FSBWFs are exactly the same, as found for the weld temperature when incorporating the linear infill pattern in 3PPCC. This remarkably validates the connection between optimal levels for WT and WH with linear infill patterns. This also reveals the similar impacts of optimal levels of FSBWFs, after being connected, on both WT and WH in terms of their optimal outcomes. In other words, it is confirmed here that the optimal WT developed at the weld zone results in optimal WH without causing brittleness in the HAZ. Interestingly, the optimal/lowest WH can also be seen in Table S2 of SIF at the optimal levels of 2000 rpm, 10 mm/min, and conical pin, as discussed in the first paragraph under Section 3.3.

The ANOVA shows that PP was the only FSBWF with a statistically significant influence on average WH with the tri-hexagonal infill pattern, with a value that was just equal to 0.05, as shown in Table S4 of SIF, and a maximum PCR of 82.55%. This indicates that tool geometry plays a decisive role in determining WH by controlling the degree of material stirring and compaction during FSBW. In contrast, TRS (p-value = 0.545, PCR = 3.61%) and TTS (p = 0.312, PCR = 9.52%) did not exhibit significant effects towards achieving optimal WH, suggesting that their variations do not strongly alter WH in welded 3PPCC with a tri-hexagonal pattern. The error PCR remained moderate, however, higher than the PCR for TRS and just comparable with that for TTS. In Figure S4 of SIF, the main effects can help identify the optimal levels of FSBWFs to acquire the optimal WH, which are 2000 rpm, 8 mm/min, and conical pin. These optimal parameters of FSBWFs for tri-hexagonal patterned samples are closely similar to those observed for linearly patterned samples except for the TTS, which was 10 mm/min for the latter.

Overall, the ANOVA highlights that WH is predominantly governed by PP, while the effects of other FSBWFs such as TRS and TTS may be investigated further to identify their significant interactions or combined effects in obtaining the optimal WH for tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC.

The interaction plots were obtained, as shown in Figure S5 of SIF, finally to investigate the reason for the high statistical error PCR, which led us to critically examine the interaction/combined effects of various FSBWF values. After thorough investigation of the interaction plot, the interaction/combined effects were only revealed to be significant among the levels of TRS and TTS, i.e., between 1800 rpm and 2200 rpm at 12 mm/min. The interaction effects were found to be less severe among the levels of PP, TRS, and TTS as per the interaction plot in Figure S5 of SIF. This is because 1800 rpm and 2200 rpm are neither optimal levels of TRS, nor is 12 mm/min the optimal level of TTS, as confirmed from the main effects plots (please see Figures S3 and S4 of SIF) of both linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns for WH. Due to this significant interaction effect, the significance of independent FSBWFs was not observed with higher error PCR. The practical implications of these interacting levels of TRS and TTS reveal the fact that these are extreme levels of FSBWFs used in joining 3PPCC. When any of these levels are employed alone with the tri-hexagonal infill pattern, they might result in a higher WH. Additionally, optimal hardness could be ensured, as a desired minimum, when these are applied in combination.

3.4. Weld Strength (WS)

A universal testing machine (UTM), as shown in Figure S6 of SIF, was used to evaluate the WS of each 3PPCC sample as per the DOE settings in Table S5 of SIF. According to ASTM D638-14 [33], the WS was tested and measured for all welded samples with a nominal strain rate of 0.1 mm/mm· min and testing speed of 5 (0.2) + 25% mm/min.

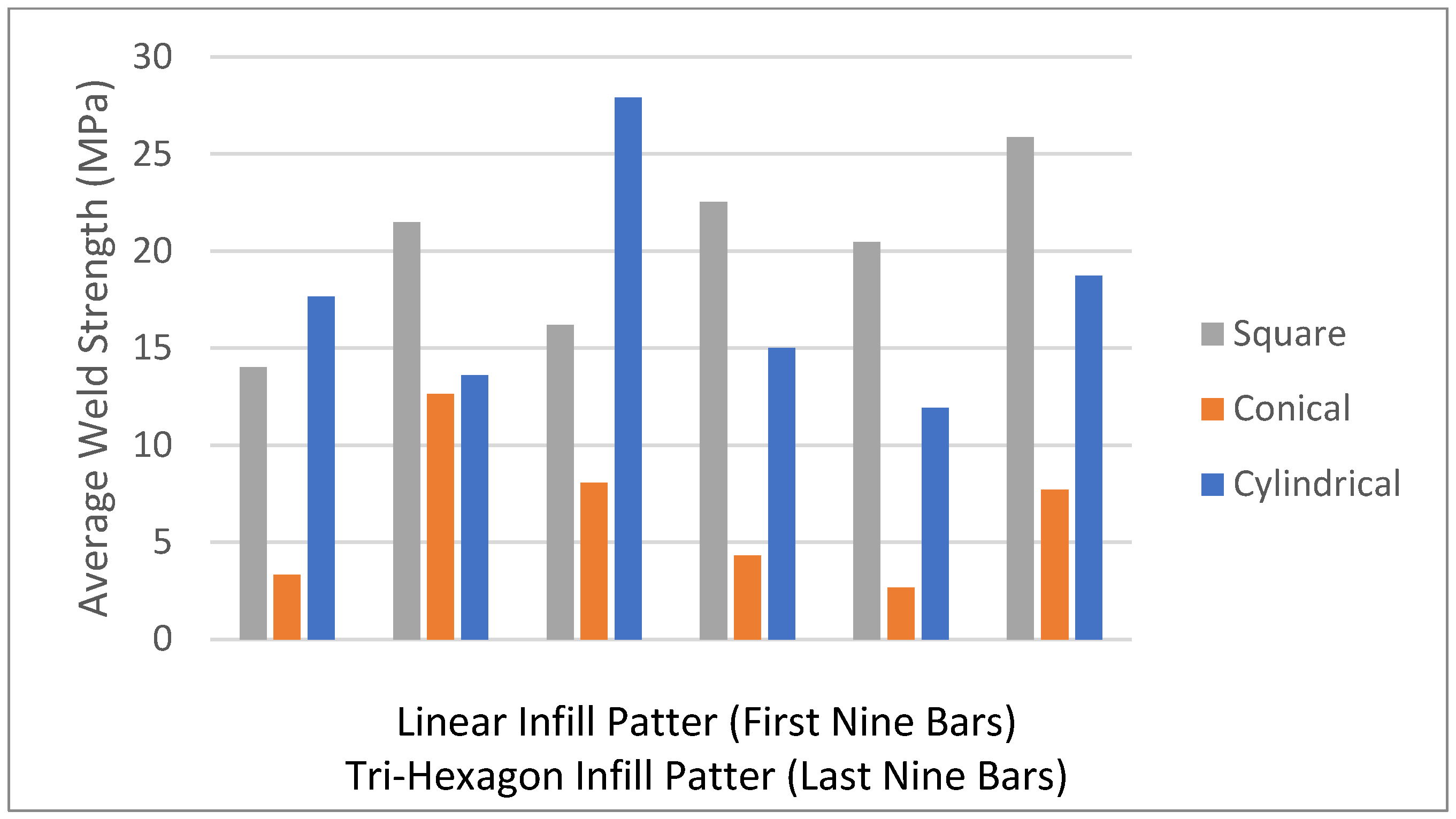

From Table S5 of SIF, the WS results indicated that higher TRS and moderate TTS yielded improved WS of welded 3PPCC, particularly when using a square PP. The highest average WS was found for Sample 9 (2200 rpm, 12 mm/min, cylindrical pin, linear infill), which achieved 27.91 MPa, while the lowest WS was recorded for Sample 3 (1800 rpm, 12 mm/min, conical pin, linear infill), with only 3.305 MPa. This suggested that cylindrical and square PPs contribute significantly to strength enhancement by ensuring better plastic flow and minimal void formation, as would be confirmed through ANOVA, main effects, and interaction plots (if deemed necessary).

The ANOVA results reveal that none of the FSBWFs yields a statistically significant effect on the average WS of welds with the linear infill pattern, as shown in Table S6 of SIF. TRS (p = 0.600, PCR = 12.89%) and TTS (p = 0.616, PCR = 12.07%) both exhibited p-values of more than 0.05, indicating their non-significant effects on average WS. Although the PP showed the lowest p-value of 0.258 with the highest PCR value of 55.70%, it still did not reach statistical significance. This suggests that FSBWFs are highly likely to interact with each other, which needs to be investigated via interaction plots for linearly infilled 3PPCC. Moreover, investigating the interaction plots was deemed essential due to the evident presence of an error PCR of up to 19.33%. This error PCR was found to be comparatively higher than those for the TRS and TTS, thereby originating the dire necessity of examining critically the interaction plots.

In the main effects plot in Figure S7 of SIF for the linear infill pattern, the optimal levels of FSBWFs are shown as 2200 rpm, 12 mm/min, and cylindrical PP. As expected, higher levels of FSBWFs were found again for WS, as also evident from the main effects for WT and WH; the only difference is that the TRS and TTS were one level more extreme than those for WT and WH, and the optimal PP was cylindrical, whereas it was conical for WT and WH. This shows that more energy was required to soften the internal configuration, i.e., linear infill pattern, that had been incorporated into 3PPCC. The linear infill pattern is somehow stronger than the tri-hexagonal infill pattern due to its orderly layup, which is more rigid and uniform throughout the sample geometry.

In Figure S8 of SIF, the interaction plots for average WS with the linear infill pattern show that the combined effects of FSBWFs were only of considerable severity among various levels of TRS and TTs and TRS and PPs. The TRS of 1800 rpm was found to interact severely with its higher levels, which were 2000 rpm and 2200 rpm at 12 mm/min, the highest level of TTS. These interactions may be considered significant in delivering maximum WS. Hence, this was also confirmed by revealing that these significant interactions at the highest levels of both TRS and TTS are necessary for breaking the organized internal structure of 3PPCC due to the presence of the linear infill pattern. In other words, better energy input is guaranteed at the weld and tool interface when the highest levels of TRS and TTS are set for FSBW. Due to this sufficient energy availability, the 3PPCC was softened and stirred properly to establish a stronger bond between the parental mating 3PPCC components. At a lower TRS of 1800 rpm and 8 and 10 mm/min, the WS values remained comparatively lower, indicating insufficient heat generation resulting in weaker bonding. PP had also the most pronounced influence, especially the cylindrical and square patterns, when combined with two levels of TRS, i.e., 2000 and 2200 rpm, producing higher WS than the conical pattern, which consistently underperformed, as a result of which poor material flow and void formation were obtained. Higher levels of TRS with the right PP also enabled the 3PPCC to soften sufficiently and develop a healthy bond with maximum WS. These interactions suggest that WS for linearly infilled 3PPCC is governed more by the combined effects of FSBWFs such as tool pin geometry, TRS, and TTS in producing a considerable source of the heat input required, rather than by the independent effects of these FSBWFs.

From Table S7 of SIF, ANOVA results indicate that both TRS and pin profile were found statistically significant towards optimally affecting average WS, while TTS showed no significant influence on average WS with the tri-hexagonal infill pattern. TRS exhibited a significant effect with a p-value of 0.011 and PCR 9.27% suggesting that variations in heat input due to different TRS directly influenced material softening and bonding eventually. PP emerged as the most dominant welding factor among other FSBWFs with an exceptionally high PCR of 90.56% and a p-value of 0.001 confirming its critical role in governing material flow and joint consolidation. In contrast, TTS did not significantly impact WS with a p-value of 0.572 and PCR of merely 0.07% implying that variations due to varying TTS did not affect and contribute sufficiently towards WS. Overall, these findings demonstrate that WS is primarily controlled by tool pin geometry and TRS, while TTS plays only a minor role for tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC.

In Figure S9 of SIF, the main effects plot reveals the optimal levels of FSBWFs for affecting average WS when the tri-hexagonal infill pattern is incorporated into 3PPCC. The optimal levels of FSBWFs found were 2200 rpm, 10 mm/min, and square PP. The highest and optimal level of TRS ensured higher rotational velocities, enhancing proper mixing of softened 3PPCC at the HAZ through increased frictional heat and improved plastic flow, thereby resulting in optimal WS. In contrast, TTS demonstrates a complex relationship with WS; moderate speed around 10 mm/min appears optimal, while both slower and faster TTS result in reduced WS, suggesting that an intermediate rate of TTS balances heat input and material consolidation effectively. Overall, TTS shows a comparatively subdued influence due to its statistical insignificance (p = 0.572), with only minor variations in WS at different TTS, suggesting that the tri-hexagonal architecture’s inherent stability mitigates the negative effects of faster travel rates that typically reduce heat input. Among different PPs, the square pin geometry yields the highest WS, benefiting from a balanced combination of stirring action and material displacement, due to its highest swept ratio, while the cylindrical pin geometry produces moderate WS, and the conical pin geometry performs poorly due to inadequate material engagement and increased void formation stemming from its overly dynamic nature. PP emerges as the most dominant factor, with the square PP, in particular, producing the highest WS, attributable to its superior stirring action and ability to disrupt the intricate infill pattern for better mixing of 3PPCC.

3.5. FSBW Efficiency

Friction stir butt welding (FSBW) efficiency, as shown in Table S8 of SIF, was evaluated in terms of WS retention compared to the unwelded 3PPCC, obtaining 38.86 MPa in the case of the linear infill pattern and 27.16 MPa in the case of the tri-hexagonal infill pattern. 3PPCC with the tri-hexagonal infill pattern exhibited an overall higher weld efficiency compared to that with the linearly infilled pattern, particularly when employing the square PP geometry. The highest weld efficiency was recorded for sample 16 (resulting from 2200 rpm, 8 mm/min, square pin, tri-hexagonal infill) with 95% efficiency, while the lowest was found in sample 3 (welded employing 1800 rpm, 12 mm/min, conical pin, linear infill), with 9% efficiency. This highlights the superior performance of square pin profiles in reducing stress concentration and increasing bonding efficiency.

Overall, the FSBW efficiency is observed to be perfectly and interestingly interlinked with three average output responses, i.e., WT, WH, and WS. Based on the weld strength of 3PPCC, maximum and minimum strengths were identified in four samples, namely samples 3 and 9 and samples 13 and 16 for both the linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns, respectively. For these four samples, there was an interesting connection among WT, WH, and WS. For maximum WTs related to samples 3 and 13 for both the linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns, respectively, WS and WH were found to have minimum values, yielding weak bonds with less joint hardness. For minimum WTs associated with samples 9 and 16 for both the linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns, respectively, WS and WH were found to have maximum values, which yielded strong bonds with better hardness. In Figure 8, the porosity was observed to be lower for samples 9 and 16, and higher for samples 3 and 13, leading to correspondingly higher and lower WS values, respectively, as expected and confirmed hereby.

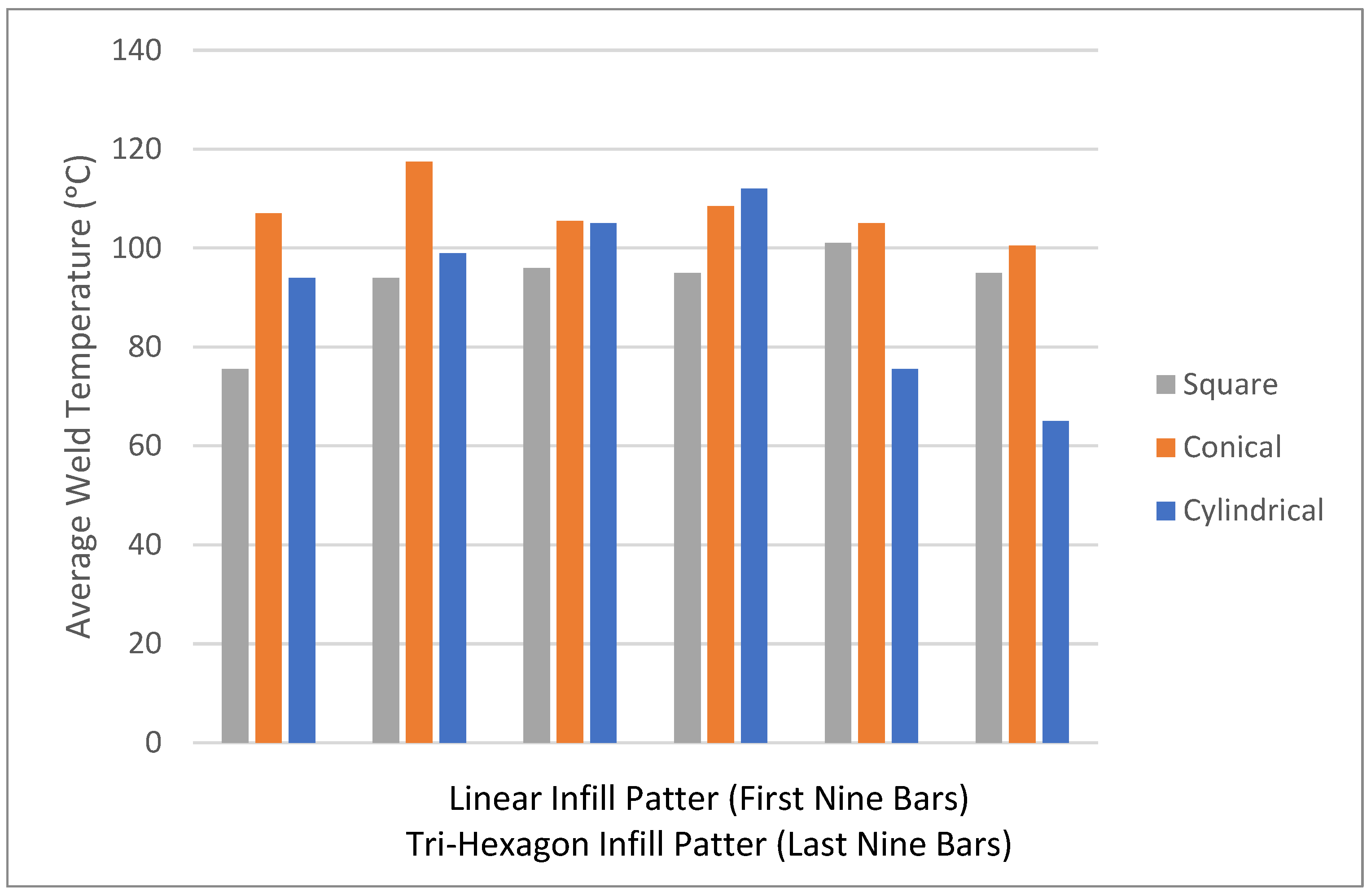

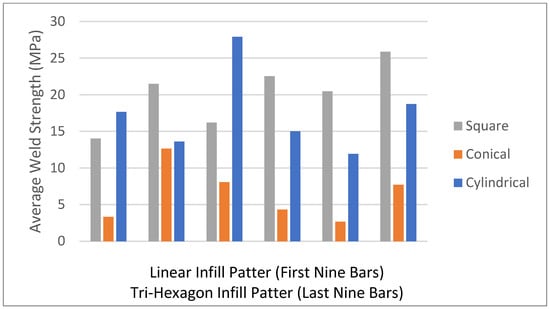

Therefore, weld temperature must be ensured appropriately as a function of FSBWFs, including infill pattern configuration, to achieve desired characteristics of the weld in terms of WT, WH, and WS. Too low and high WTs will result in poor bonding in terms of both WS and WH. For example, the PP is the FSBWF that contributed the most in terms of its PCR, as mentioned and discussed in the ANOVA tables earlier for WT, WH, and WS. So, the impact of PPs on WT, WH, and WS cannot be overlooked in the presence of both infill patterns. In fact, the conical PP produces the maximum WT, while the cylindrical and square PPs cause the WT to reach its appropriate value. Hence, WS and WH were found to be lower with the conical PP and higher with both the cylindrical and square PPs for both linear and tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC, as shown in Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, where the first nine bars are plotted for linearly infilled 3PPCC and the last nine bars for tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC.

Figure 11.

WT developed at HAZ due to both PPs and infill patterns.

Figure 12.

WS developed at HAZ due to both PPs and infill patterns.

Figure 13.

WH developed at HAZ due to both PPs and infill patterns.

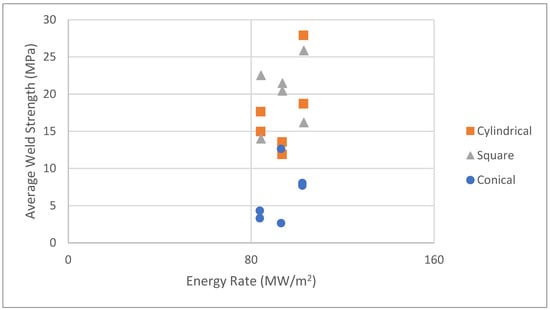

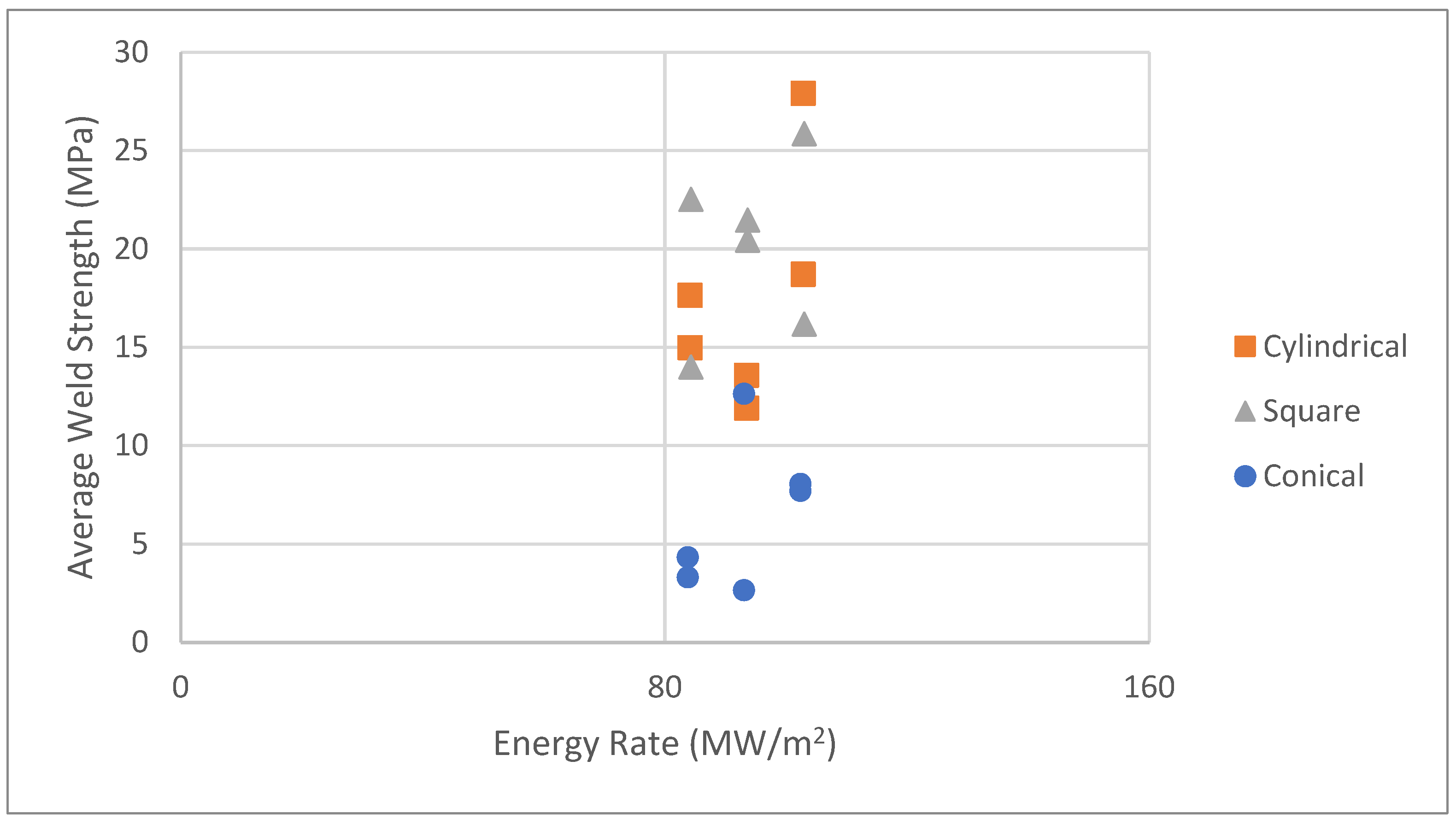

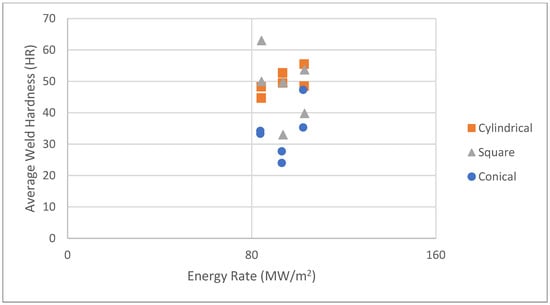

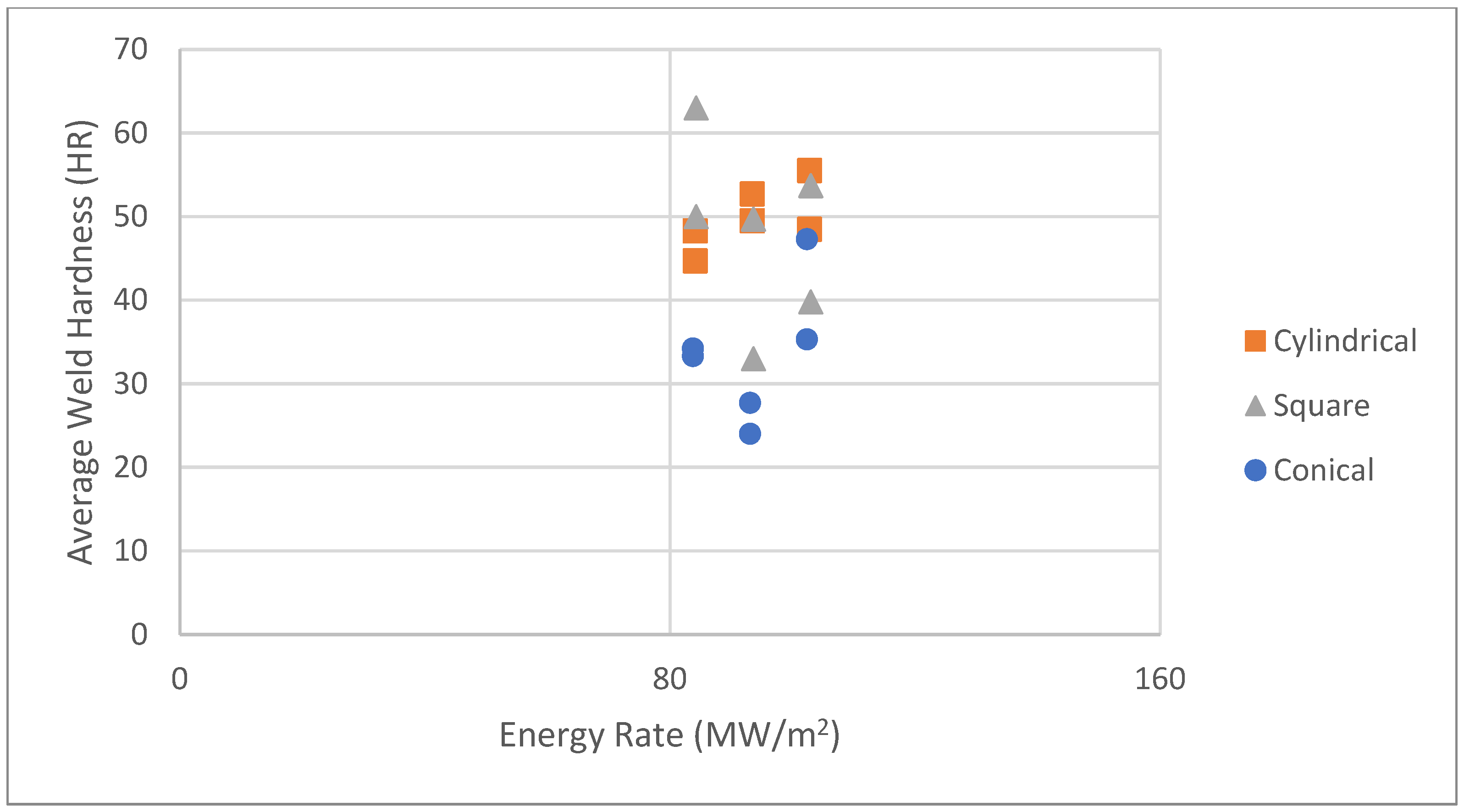

Energy input (Q) was also computed as a function of FSBWFs, including TRS, tool pin and tool shoulder radii, and yield strength, as shown in Equation (4) [43]. The units of energy input were J/s.m2 or Watt/m2. Figure 14, Figure 15 and Figure 16 show the impact of energy input on WT, WS, and WH for three PPs.

where

- k = Yield Strength of 3PPCC (MPa)

- W = TRS (rad/s)

- Rs = Radius of Shoulder (mm)

- Rp = Radius of Cylindrical/Equivalent Radius of Any of Square/Conical Pins (mm)

Figure 14.

Impact of energy input on WT for three PPs.

Figure 14.

Impact of energy input on WT for three PPs.

Figure 15.

Impact of energy input on WS for three PPs.

Figure 15.

Impact of energy input on WS for three PPs.

Figure 16.

Impact of energy input on WH for three PPs.

Figure 16.

Impact of energy input on WH for three PPs.

Figure 14 shows that the optimal WT could only be acquired with moderate energy input, i.e., 93.07 × 106 Watt/m2 (93.07 megawatts (MW)/m2) with the conical PP. Higher energy input of up to 102.95 × 106 Watt/m2 or 102.95 MW/m2 was required, however, with the cylindrical and square PPs to ensure optimal WS and WH, as shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16.

3.6. Validation of WT, WH, and WS

Six validation experiments were conducted against optimal levels of FSBWFs, as shown in Table 7. As the maximum WT found was 117.5 °C, WT was found to be 132 °C with the linearly infilled 3PPCC after a validation experiment showing an improvement of 12.3% over 117.5 °C in WT and an improvement of 0.4% over 117.5 in WT with the tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC. Likewise, the minimum WH was desired to alleviate the brittleness in welds. After validation experiments, the WH was found to be further reduced by up to 18 HD and 25.33 HD, as shown in Table 7, for both the linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns in 3PPCC yielding a reduction of 34% and 46.1%, as compared to HD values for unwelded 3PPCC samples with linear and tri-hexagonal infill patterns, respectively. The validated values for WT and WH were measured nondestructively before the tensile testing of welded 3PPCC specimens. In the same manner, an improvement in WS was also observed after the validation experiment involving destructive tensile testing. The highest values for WS were found to be 29.39 MPa and 30 MPa, which are again improvements in WS.

Table 7.

Validation experiments employing optimal levels of FSBWFs (NA means “not applicable”).

Tool pin profile markedly influences weld-zone behavior in PLA-based friction stir welding, as evidenced by several recent investigations. For instance, Arumugam et al. (2025) [44] reported that optimized pin geometries in polymer spot-welding led to measurable increases in hardness and UTS, with peak joint strength occurring at the largest pin diameter and lowest defect count. These findings reinforce the conclusion that the choice of pin profile not only governs material flow and mixing quality but directly impacts thermal exposure, hardness retention, and ultimate tensile strength in 3PPCC. Many researchers have welded the vital materials (wood, calcium carbonate (CaCO3), etc.) and reinforced PLA composites to obtain optimal welding output parameters such as weld temperature, weld hardness, and weld efficiency. For example, N. Anac et al. [28] achieved an average weld efficiency of 63.77% in 30% reinforced wood in PLA parts while testing tensile strength using a square pin at 1750 rpm and 20 mm/min, and observed weld temperatures of up to 207 °C for the highest-strength joints. Moreover, weld hardness was found to be equal to 72 according to the Shore D Hardness scale for PLA-30%Wood. In another study, on FSW of 3D-printed PLA-Plus (PLA-2%CaCO3), N. Anac et al. [11] found the tensile weld efficiency, weld temperature, and weld hardness (Shore D) to be equal to 28.30%, 198.97 °C, and 83, respectively, while corresponding values of 74.5%, 219.21 °C, and 73 were found by O. Kocar et al. [45] in the same parametric order. N. Anac et al. [46] conducted another study on FSW of 3D-printed PLA-Plus. They found weld efficiency and weld temperature to be 87.04% and 163 °C, respectively. Weld hardness, as they claimed to have evaluated, was not found in their published work.

In Table 7, the current research interestingly achieved a weld temperature well below the melting point of PLA (180 °C), i.e., 118 °C for tri-hexagonal and 132 °C for linear infill patterns. This fulfills the requirement of solid-state joining of 3PPCC via FSBW with sufficient softening above Tg, i.e., 65 °C. On the other hand, the weld hardness was found to be comparatively much lower, as compared to previous studies, i.e., up to 25.33 and 18 for both tri-hexagonal and linear infill patterns, respectively. This ensures a substantial reduction in 3PPCC joint brittleness at the HAZ. Finally, the tensile weld efficiencies were found to be 108% and 75.63% for the tri-hexagonal and linear infill patterns. Conclusively, tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC remained optimal in terms of weld temperature and weld efficiency, as compared to past studies, and linearly as well as tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC achieved comparatively better and optimal weld hardness. These are the significant improvements found for weld temperature, weld hardness, and weld efficiency/weld strength, which have never been achieved before for composites based on PLA.

3.7. Microscopic and Morphological Analyses Through Coordinate Measuring Machine (CMM) and Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

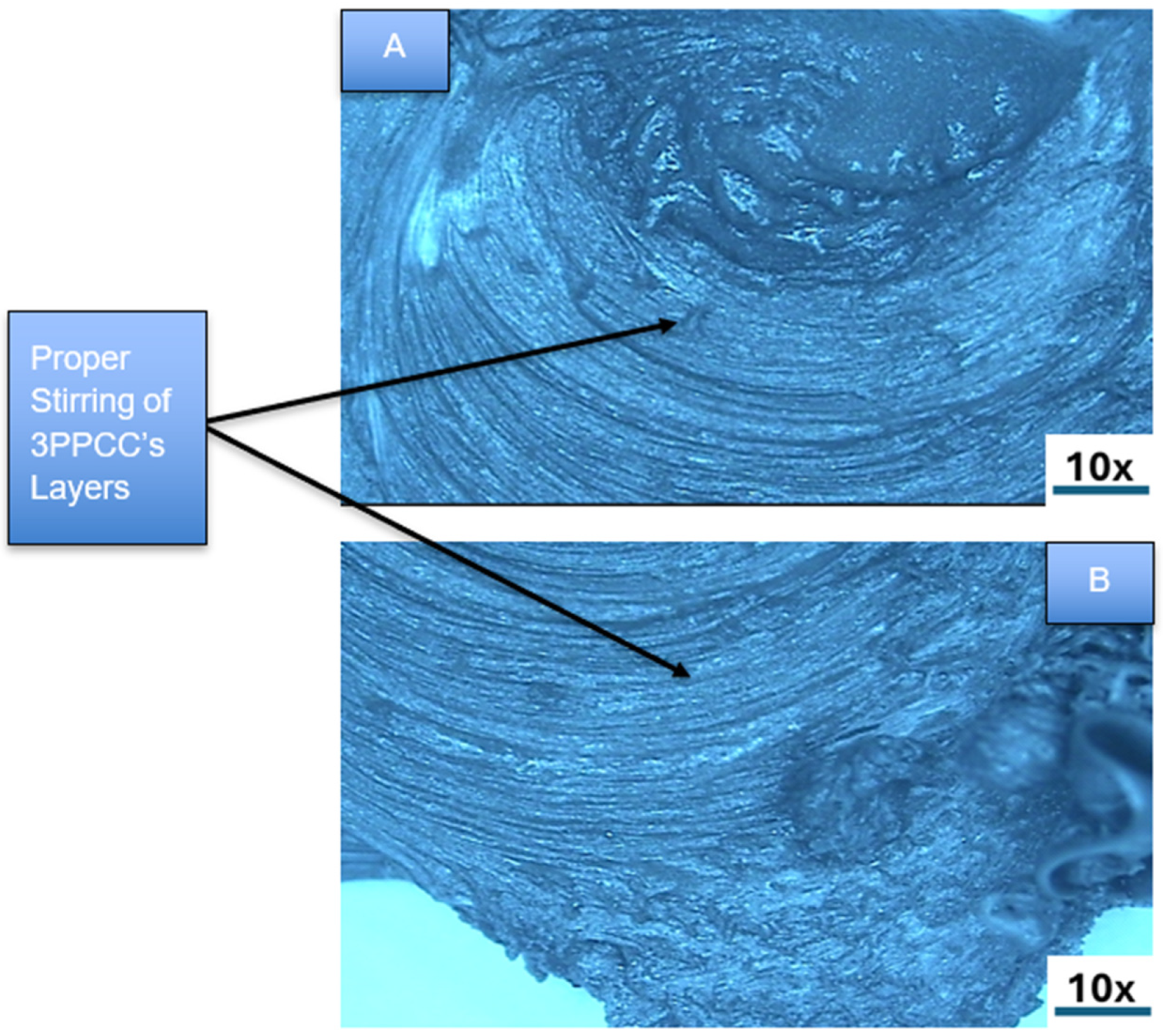

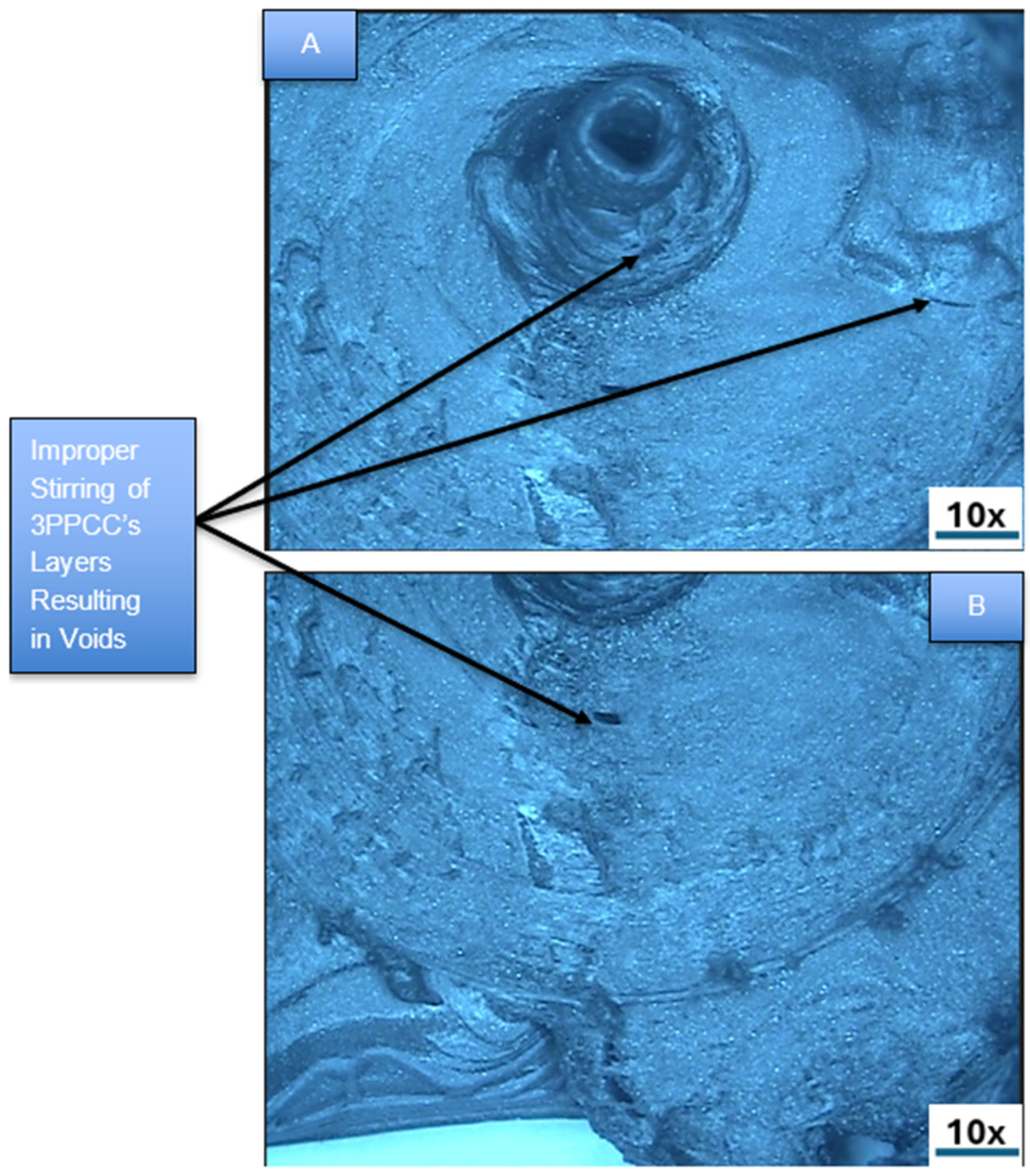

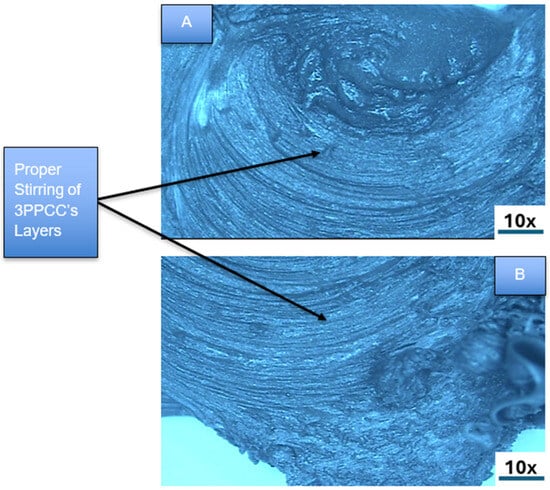

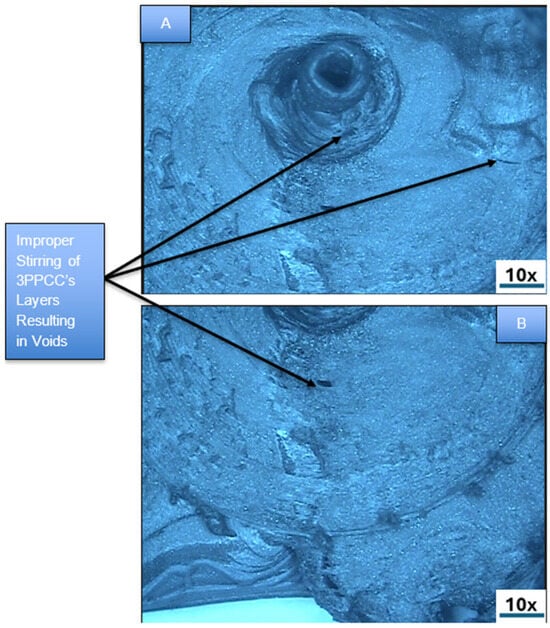

Surface morphology analysis was performed using CMM first at 10x resolution. Four representative samples were selected, namely samples 3, 9, 13, and 16, as already discussed in Section 3.5. These samples were chosen to represent the extreme ends of weld quality considering each infill pattern category. Specifically, sample 3 demonstrated the lowest WS among the linearly infilled 3PPCC samples, while sample 9 exhibited the highest WS in the same category. Similarly, sample 13 showed the lowest WS, and sample 16 presented the highest WS when employing the tri-hexagonal infill group. This selection enabled a comparative microscopic and morphological assessment of both underperforming and high-performing weld zones, providing a deeper understanding of how FSBWFs and infill architecture collectively affect the weld integrity and reinforcement distribution in friction stir welded 3PPCC.

A smoother surface with minimal porosity was accomplished with the cylindrical pin profile, indicating better interfacial bonding and proper material fusion without any voids at the heat-affected zone (HAZ), as shown in all parts of Figure 17A,B and Figure S10 of SIF for sample 9. Large voids and weak material bonding were revealed when welding samples with the conical pin, due to poor material flow, as shown in all parts of Figure 18A,B and Figures S11 and S12A–C of SIF for samples 3 and 13, respectively. A rough surface was found microscopically with FSBW of 3PPCC with the square pin, due to better material shearing and a higher swept ratio, but with excellent strength retention due to minimal void formation with good and proper material fusion, as shown in all parts of Figure S13 of SIF for sample 16. These findings align with existing studies, confirming that PPs and infill pattern play crucial roles in defining surface morphology and mechanical properties of FSBW of 3PPCC.

Figure 17.

(A,B) Heat-affected zone (HAZ) for sample 9.

Figure 18.

(A,B) HAZ for sample 3.

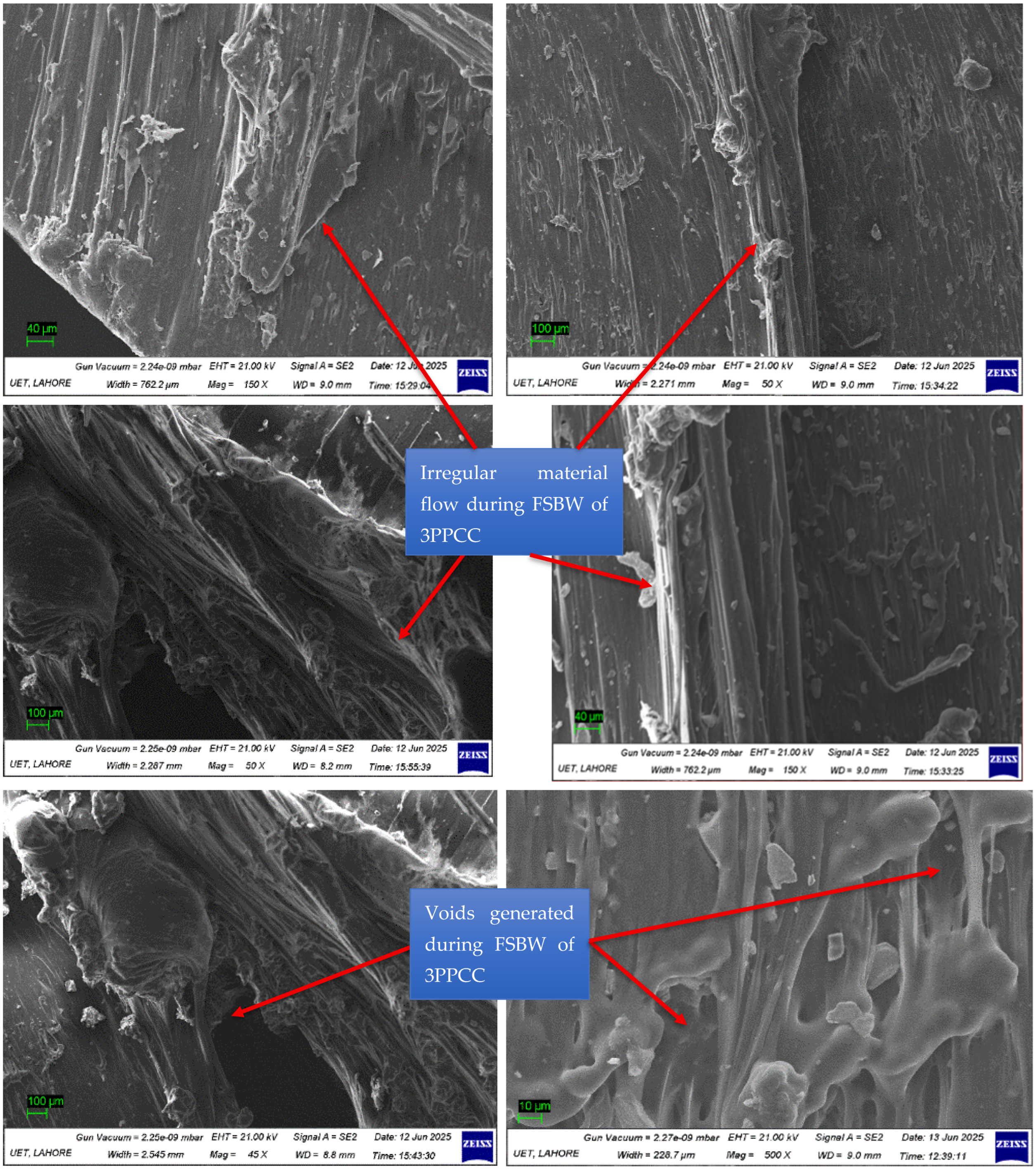

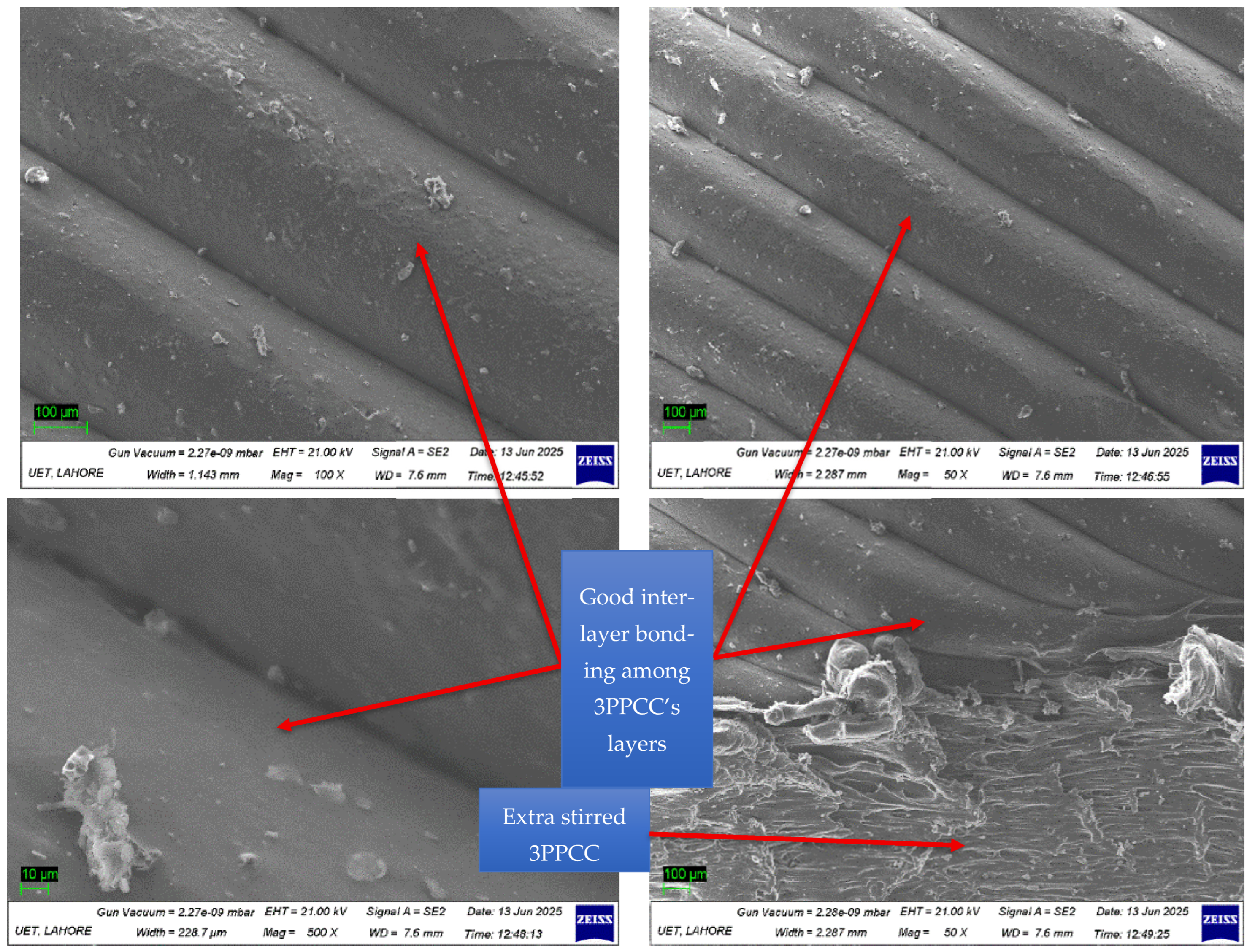

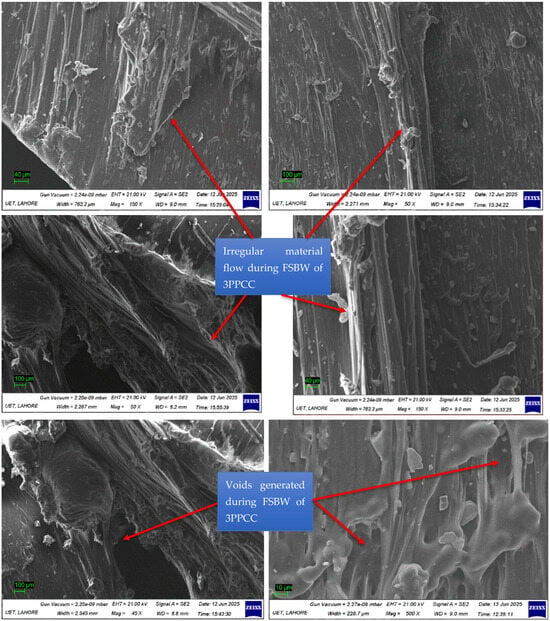

To investigate the microstructural characteristics influencing mechanical performance, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis were also conducted on the weld zones of four strategically selected samples, 3, 9, 13, and 16, as investigated earlier in CMM.

In Figure 19, the SEM results for sample 3 (corresponding to the lowest WS value with linear infill category) revealed distinct morphological features indicating poor weld integrity. The weld zone exhibited incomplete interlayer stirring, characterized by the presence of multiple voids, micro-cracks, and irregular flow lines. These features suggest insufficient plasticization and inadequate material mixing, during the FSBW of 3PPCC, that are likely due to the use of a conical PP at a lower TRS (1800 rpm) and a higher TTS (12 mm/min).

Figure 19.

SEM images for sample 3.

The SEM images (with red arrows) also showed localized gaps/voids between PLA layers, which could have originated from the limited mechanical stirring action of the conical pin geometry. This reduced stirring leads to non-uniform dispersion of chromium reinforcement and inadequate interfacial bonding, both of which contribute to mechanical failure under lower tensile loading. The poor surface continuity observed further supports the hypothesis of disrupted material flow, with some regions indicating effects of thermal gradients initiating pull-out voids, resulting in the weak joint after mechanical tests.

These observations align with the existing literature on FSBW of thermoplastic composites, where low WS is frequently associated with inadequate heat input, insufficient tool–material interaction, and ineffective stirring among the adjoining surfaces [34,35,36]. For instance, the SEM features in sample 3 substantiate the correlation among FSBWFs and inferior mechanical performance of the resulting 3PPCC joint.

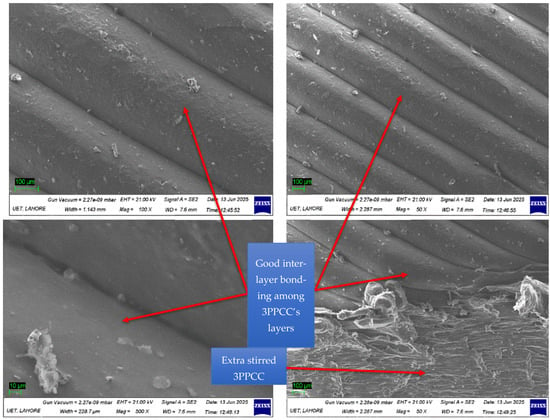

Figure 20 illustrates the SEM-based morphological evaluation of sample 9, which recorded the highest WS among the linear infill group, revealing a distinctly cohesive and well-bonded weld structure. The magnified visual inspection confirmed the presence of uniform interfacial bonding and minimal porosity across HAZ. The material flow appeared continuous and uninterrupted, indicating that the selected FSBWF levels, such as TRS (2200 rpm), TTS (12 mm/min), and cylindrical PP, enabled optimal heat input and effective plasticization at the HAZ of the 3PPCC joint. The absence of visible voids or improper stirring at the HAZ guarantees strong metallurgical contact and enhanced diffusion among the PLA matrix and chromium reinforcement particles. This compact and homogenous microstructure is attributed to efficient stirring action and favorable interlocking of the infill pattern, which collectively contributed to the superior mechanical performance of the obtained joint.

Figure 20.

SEM images for sample 9.

In Figure S14 of SIF, SEM micrographs of sample 13 offer valuable insights into the suboptimal bonding behavior that contributed to its poor mechanical performance in terms of lower WS. At higher magnification (100x), the weld zone reveals the presence of irregular voids, un-melted or partially stirred particles, and discontinuous bonding interfaces. These defects indicate the insufficient heat generation and non-uniform plastic flow during the FSBW of 3PPCC. The observed discontinuities and void clusters suggest that the conical PP, when used at 2000 rpm and 8 mm/min, failed to provide the HAZ with the necessary stiffness, stirring, and proper plastic flow to promote thorough consolidation of the 3PPCC joint.

Moreover, the poor bonding appears to have been exacerbated by the complex internal geometry of the tri-hexagonal infill, which, despite offering potential strength advantages under ideal welding conditions, may have caused uneven heat distribution in this case. The chromium particles in the PLA matrix were not uniformly dispersed within the weld nugget, and certain regions displayed localized aggregation, potentially acting as stress concentrators. Such microstructural discontinuities explain the reason for 3PPCC’s low weld efficiency (10%) and significantly reduced WS (up to 2.645 MPa).

In summary, the morphological evidence supports the conclusion that a conical PP with other FSBWFs was ineffective in achieving adequate bonding and material flow even with the incorporation of tri-hexagonal patterned structures in 3PPCC. This emphasizes the need for optimal combinations of FSBWF levels, especially when working with complex infill architectures.

In Figure S15 of SIF, SEM micrographs of sample 16 reveal a densely packed and well-consolidated weld zone, indicating superior bonding among 3PPCC layers. The material interface appears appropriately dispersed, with minimal evidence of voids or unbonded regions, reflecting highly effective plastic flow during FSBW. The microstructure displays a uniform distribution of chromium particles embedded within the PLA matrix, disclosing its efficient dispersion due to employing optimal levels of both TRS and TTS.

The edges of the HAZ exhibit slight texturing likely caused by mechanical stirring action of the square PP, promoting proper interlayer mixing and enhancing mechanical interlocking. The fracture surface morphology shows ductile tearing features and localized plastic deformation bands, indicating that the joint failure mechanism was predominantly cohesive rather than adhesive. As compared to low WS samples, sample 16 exhibits fewer micro-cracks and significantly reduced porosity, directly contributing to its high weld efficiency and WS.

This microstructural integrity aligns with the mechanical test results confirming that the selected FSBWFs, i.e., 2200 rpm (TRS), 8 mm/min (TTS), square PP, and tri-hexagonal infill, should be confidently employed to achieve maximum WS of 3PPCC.

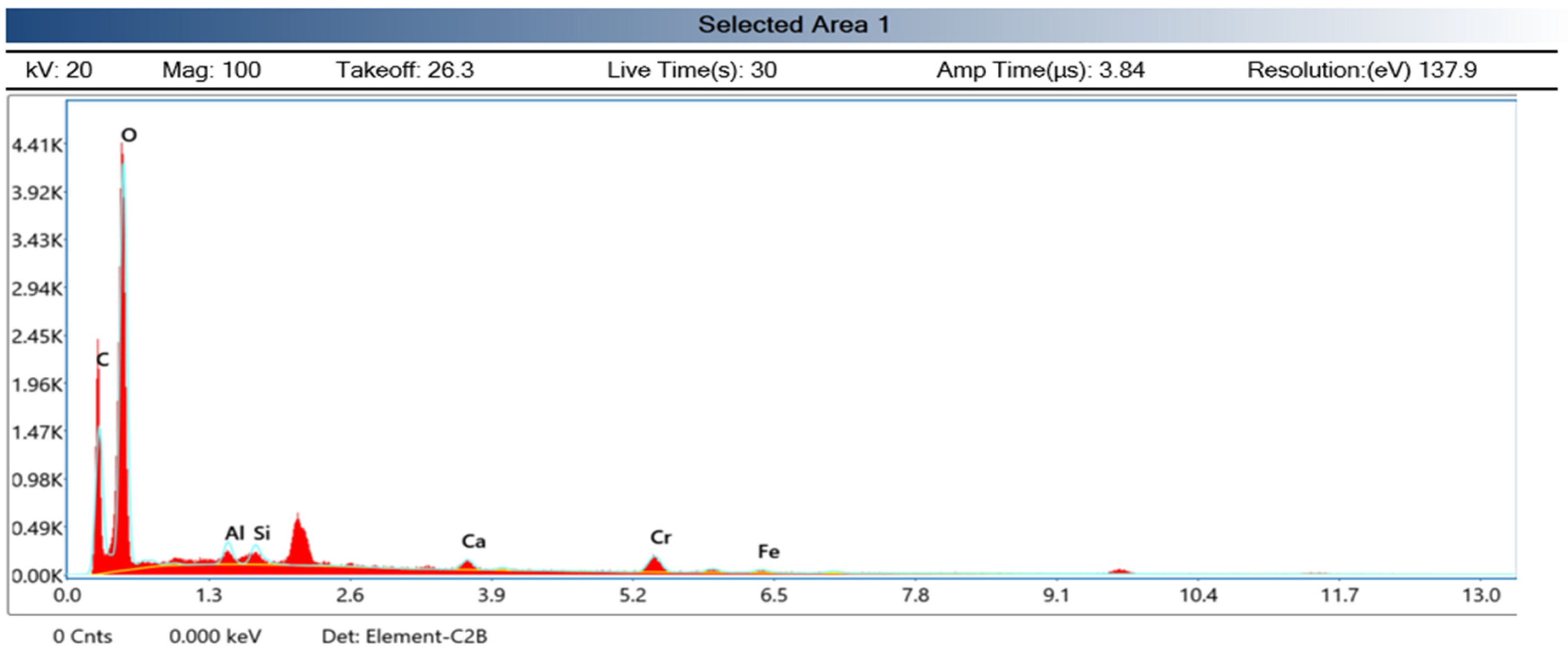

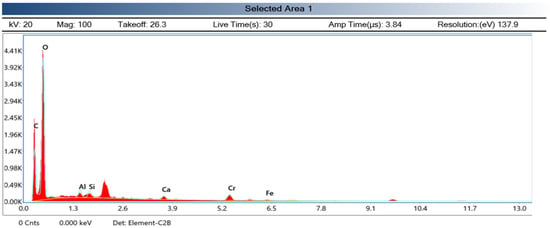

3.8. Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDX) Analysis

The EDX spectrum of sample 3 reveals the dominant presence of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) peaks, which are consistent with the PLA matrix composition. The quantitative analysis earlier confirmed C (28.53 wt%) and O (64.95 wt%), as shown in Table 8, reflecting the decomposition and oxidation behavior of the PLA matrix of 3PPCC under thermal loading during FSBW. The elevated oxygen peak suggests partial oxidative reactions in the HAZ, which may have contributed to brittleness and micro-void formation, ultimately lowering the WS. This observation aligns with the low WS found for sample 3, as compared to those for other samples while joining 3PPCC.

Table 8.

EDX Smart Quant Results for Sample 3.

In addition to the PLA matrix elements, traces of chromium (Cr) (2.52 wt%) were detected, confirming the incorporation of metallic reinforcement within the 3PPCC joint. However, the Cr content appeared to be unevenly distributed, as suggested by the relatively small and sharp Cr peak around 5.2 keV, as shown in Figure 21. Poor dispersion of chromium likely resulted in localized stress concentrations and weak interfacial bonding, which hindered the material’s ability to transfer load effectively across the weld zone. This is one of the causes of low weld efficiency observed for this sample compared to higher-performing specimens (e.g., samples 9 and 16).

Figure 21.

EDX graph for sample 3.

Other detected elements, including aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), calcium (Ca), and iron (Fe), were present in very small amounts (<2 wt%). These are most likely trace contaminants from the feedstock, environmental exposure, or tool interaction during FSBW of 3PPCC. Although their influence on bulk properties is minimal, they may have contributed to elemental heterogeneity in the weld interface, further weakening the joint quality.

Overall, the elemental imbalance, dominated by oxygen enrichment and poor chromium dispersion, was the key factor behind the poor weldability of sample 3. The excessive oxygen content reduced ductility, while insufficient Cr weightage failed to compensate for the sample’s poor weldability. Thus, despite being 3PPCC, the welding performance was significantly undermined by stress concentrators, interfacial voids, and uneven filler distribution, pointing collectively to the lowest WS values obtained for sample 3 with the linear infill configuration.

The EDX results for sample 9 involve carbon (27.95 wt%) and oxygen (62.88 wt%), which dominate the weld composition, consistent with the PLA matrix, where C and O form the primary polymer backbone, as shown in Table S9 of SIF. The EDX graph is shown in Figure S16 of SIF. The relatively high oxygen content suggests localized oxidative interactions during welding, which may have enhanced interfacial adhesion in the weld zone. Chromium was found at 5.58 wt%, slightly lower than its nominal 10% reinforcement within 3PPCC, indicating that while Cr was present in the matrix, some particle segregation or uneven distribution likely occurred during the FSBW process. Nevertheless, this concentration of Cr was sufficient to provide the 3PPCC joint with better strengthening by promoting interfacial bonding, filling the voids, and restricting void growth.

Minor elements such as Al (1.8 wt%) and Ca (1.34 wt%) may originate from trace impurities in the raw material or filler contamination during FSBW. Their small presence did not significantly compromise the weld but could have contributed to localized inclusions. Manganese was observed in trace amounts (0.44 wt%) with a high error margin of 30.26%, suggesting it was not a major contributing element affecting the HAZ.

From a performance perspective, the relatively high chromium retention in sample 9 compared to other low-strength samples (e.g., sample 3) played a decisive role in achieving improved WS and weld efficiency, irrespective of having linear infill structures. The stronger bonding and reduced porosity observed microscopically in sample 9 correlate with the balanced presence of Cr, C, and O, which together enhanced interfacial mixing. Thus, sample 9′s composition directly supports its superior weld strength and structural performance.

The EDX spectrum of sample 13 is dominated by carbon (28.48 wt%) and oxygen (66.51 wt%), as shown in Table S10 of SIF, which is expected from the PLA matrix, indicating the signal is largely polymer-rich in the probed region, as also shown in Figure S17 of SIF. The chromium content was only 2.15 wt%, well below the nominal 10% reinforcement, pointing to severe chromium depletion at the weld surface/volume analyzed. This deficit suggests that the Cr phase either segregated away from the stir zone during FSBW or was pulled out by the FSBW tool, or became trapped in unprobed cluster mechanisms that would all reduce effective particle bridging and load transfer across the HAZ.

Minor elemental traces of Al (1.10 wt%), Ca (0.94 wt%), Fe (0.50 wt%), and Mn (0.32 wt%) also appear. Al and Ca are consistent with environmental/filament impurities or handling debris, while Fe and Mn likely reflect tool/fixture wear or shop contamination. Their low concentrations and the relatively high error for Mn indicate they are incidental; however, such inclusions can act as stress concentrators or nucleation sites for micro-voids if they are not well bonded to the PLA matrix.

From a welding performance standpoint, the low Cr retention in the analyzed weld zone explains the poor mechanical response observed for this sample (lowest WS and weld efficiency within the tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC). With fewer Cr particles participating in the stirred seam, the weld relies mostly on polymer–polymer bonding. That combination, together with possible oxide-rich regions (high O content) and metallic debris, promotes interfacial weakness and void formation, which is consistent with the SEM evidence of discontinuous bonding and defects previously noted for sample 13. In short, sample 13′s composition reveals an under-reinforced/Cr-deficient weld zone with contamination traces that perfectly points to its reduced WS and weld efficiency.

The point EDX analysis of sample 16 shows a surface composition dominated by carbon (38.97 wt%) and oxygen (57.13 wt%), consistent with a polymer-rich (PLA) surface, as shown in Table S11 of SIF. Compared with other samples in this study, sample 16 exhibits a higher carbon fraction and a noticeably lower oxygen fraction, suggesting reduced oxidative alteration of the PLA matrix in the 3PPCC weld. Lower oxygen content at the analyzed location is consistent with less thermal decomposition or surface oxidation during FSBW, and it correlates with the sample’s favorable mechanical behavior (high WS and weld efficiency).

Chromium’s 10 wt% reinforcement does not appear as a strong peak in a particular point of the spectrum. At this probed location, absence (or very low local signal) of Cr should not be interpreted as overall absence of reinforcement in the specimen; instead, it likely reflects local heterogeneity in particle dispersion or a sampling position within a polymer-rich pocket of the HAZ. In strong welds, chromium particles may be more uniformly distributed across the seam cross-section or embedded beneath the immediate surface, reducing their relative concentration in a surface point analysis.

Apparently, local scarcity of Cr in the point measurement does not contradict strong mechanical performance; it likely reflects favorable bulk dispersion of Cr throughout the weld rather than localized surface exposure under investigation. In other words, effective reinforcement can exist even if not visible in a single surface point of the spectrum.

As shown in Figure S18 of SIF, several minor elements were also detected at trace levels (Na, Mg, Al, Si, Mo, Cl, K, Ca, Fe, Ni). These signals likely originate from a combination of additives in the filament, minor contaminants, and very small amounts of tool or fixture transfer (Fe, Ni, Mo). Their low weight fractions (<1 wt% each) and generally modest atomic percentages indicate they are unlikely to dominate mechanical response; nevertheless, they can act as nucleation sites for localized defects if present as agglomerates or hard inclusions. The detection errors for some trace peaks are large, so these elements should be considered along with their minor impacts on HAZ health.

4. Conclusions

This research systematically investigated the application of FSBW for joining 3D-printed PLA-Chromium composites (3PPCC), with a focus on determining the influence of TRS, TTS, PP, and infill patterns on weld quality in terms of WT, WH, and WS. The findings of this study highlight the crucial roles of FSBWFs and internal infill structures in optimizing joint integrity. Key conclusions of this study are as follows:

- This study found that PP was the most strongly contributing FSBWF in securing the optimal weld quality of 3PPCC in terms of WT, WH, and WS, regardless of infilled structure type.

- Both square as well as cylindrical PPs consistently delivered higher weld efficiency, WS, and better WH retention due to superior stirring and defect minimization.

- Conical pins underperformed across both infill patterns, primarily due to excessive material loss, void formation, and maximizing unnecessarily the WT at the HAZ during FSBW. WT was also found to be increased from 117.5 °C to 132 °C after applying optimal FSBWF levels for the validation experiments.

- Integration of tri-hexagonal infill patterns and optimized square PP can substantially enhance weld efficiency in terms of WT, WH, and WS, highlighting FSBW positively as a promising technique for additively manufactured Cr-reinforced PLA composites, i.e., 3PPCC.

- Tri-hexagonal infilled 3PPCC demonstrated overall superior WH retention (up to 34%) in terms of less brittleness after the validation experiment and better weld efficiency as compared to linearly infilled samples owing to better stress distribution and improved interfacial bonding.

- In the linearly infilled 3PPCC, the highest WS (29.39 MPa) was achieved by sample 9 (cylindrical pin, TRS 2200 rpm, TTS 12 mm/min) after the validation experiment, while the lowest WS was observed in sample 3 (conical pin, TRS 1800 rpm, TTS 12 mm/min).

- In the tri-hexagonally infilled 3PPCC, the highest WS of 30 MPa was recorded for sample 16 (square pin, TRS 2200 rpm, TTS 8 mm/min) after the validation experiment, whereas the lowest WS occurred in sample 13 (conical pin, TRS 2000 rpm, TTS 8 mm/min).

- Linearly infilled 3PPCC, being simpler, showed higher variability in WS, with the highest PCR from both TRS and PP.

- SEM analysis confirmed that samples with higher WS (linearly infilled sample 9 and tri-hexagonally infilled sample 16) exhibited well-consolidated and uniformly bonded joints with minimal voids. In contrast, the lowest performing samples showed interfacial gaps and weak bonding.

- EDX analysis revealed that chromium particles (excellent percentages by weight) were retained within the PLA matrix, contributing to weld strengthening, while variations in oxygen and minor elements (such as Na, Mo, and Mg in sample 16) may have supported localized strengthening, leading to higher weld efficiency and WS.

Future work will involve extending this work to either increase the Cr particles by weight in the PLA matrix or embed other metals such as aluminum with a particle percentage by weight almost equal to that of Cr in this research. Weld quality will again be assessed for optimizing WT, WH, and WS. Finally, a comparison of current research work will be established with the future work as a strong case for further improvement in weld characteristics. This study establishes a foundation for further research into enhancing the weld quality and performance of 3D-printed thermoplastic composites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcs10020072/s1, Figure S1. Thermal imager employed for WT; Figure S2. Main effects plot for average WT in tri-hexagonal infill pattern; Figure S3. Main effects plot for average weld hardness in linear infill pattern; Figure S4. Main effects plot for average WH in tri-hexagonal infill pattern; Figure S5. Interaction plots of average weld hardness for tri-hexagonal infill pattern; Figure S6. Universal testing machine (UTM) used to measure WS; Figure S7. Main effects plot for average WS (MPa) in linear infill pattern; Figure S8. Interaction plots of average WS (MPa) for linear infill pattern; Figure S9. Main effects plot for average WS (MPa) in tri-hexagonal infill pattern; Figure S10. Heat-affected zone (HAZ) for Sample 9; Figure S11. HAZ for Sample 3; Figure S12. (A–C). HAZ for Sample 13; Figure S13. (A–D). HAZ for Sample 16; Figure S14. SEM results for Sample 13; Figure S15. SEM results for Sample 16; Figure S16. EDX graph of Sample 9; Figure S17. EDX graph of Sample 13; Figure S18. EDX graph of Sample 16; Table S1. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of tri-hexagonal infill pattern for WT; Table S2. Weld hardness (WH); Table S3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of linear infill pattern for average. weld hardness; Table S4. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of tri-hexagonal infill pattern for average WH; Table S5. Weld strength (WS); Table S6. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of linear infill pattern for average WS; Table S7. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of tri-hexagonal infill pattern for average WS; Table S8. Weld efficiency; Table S9. EDX Smart Quant results for Sample 9; Table S10. EDX Smart Quant results for Sample 13; Table S11. EDX Smart Quant results for Sample 16.

Author Contributions

S.F.R.: Conceptualization, Data analysis, Resources, Methodology, Writing—original draft; M.U.F.: Methodology, Data analysis, Writing, Investigation; S.A.K.: Methodology, Data analysis, Writing, Investigation; K.H.M.: Review and editing; E.U.H.: Review and editing, Data analysis; A.M.M.: Review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The current research did not receive any funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The authors confirm that they have abided by the publication ethics, state that this work is original, and has not been used for publication anywhere before.

Informed Consent Statement

The authors give consent to the journal regarding the publication of this work.

Data Availability Statement

The data related to experimental findings are reported within the paper, and can also be available from corresponding authors, Ahmed M. Mehdi, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan, for access to the research facilities used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence this work.

Abbreviations

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| MEX | Material Extrusion |

| 3D | Three Dimensional |

| FSW | Friction Stir Welding |

| FSBW | Friction Stir Butt Welding |

| FSBWFs | Friction Stir Butt Welding Factors |

| TRS | Tool Rotational Speed |

| TTS | Tool Traverse Speed |

| PP | Pin Profile |

| CMM | Coordinate Measuring Machine |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| Cr | Chromium |

| PC | PLA-Cr |

| PCC | PLA-Cr Composites |

| 3P | 3D-Printed |

| 3PPCC | 3D-Printed PLA-Cr Composites |

| wt | Weight |

| RP | Revolutionary Pitch |

| RPM | Revolutions Per Minute |

| RPMM | Revolutions Per Millimeter |

| EDX | Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| SR | Swept Ratio |

| WT | Weld Temperature |

| WH | Weld Hardness |

| WS | Weld Strength |

| Tm | Melting Temperature |

| Tg | Glass Transition Temperature |

| PCR(s) | Percent Contribution(s) |

| Anova | Analysis of Variance |

| IP | Interaction Plot |

| SI(s) | Severity Index(-ices) |

| HAZ | Heat-Affected Zone |

References

- Raza, S.F.; Shehzad, A.; Ishfaq, K.; Raza, M.T.; Haider, S.M.; Mehdi, A.M. Optimizing the dynamic and static mechanical properties of 3D printed polylactic acid (PLA). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 138, 3473–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.H.; Montero, M.; Odell, D.; Roundy, S.; Wright, P.K. Anisotropic material properties of fused deposition modeling ABS. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2002, 8, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, Q.; Bellehumeur, C.; Gu, P. Composite modeling and analysis for fabrication of FDM prototypes with locally controlled properties. J. Manuf. Process. 2002, 4, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Narayan, Y.S. Tensile Testing and Evaluation of 3D-Printed PLA Specimens as per ASTM D638 Type IV Standard; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]