Abstract

Driven by regulatory and environmental demands, composite structures must combine high structural performance, recyclability, and resource efficiency. Here, an investigation on the structural adhesive bonding of glass-fibre-reinforced thermoplastic Elium© composite laminates is undertaken. Substrates are manufactured using vacuum infusion. Evaluation is performed on the following three commercial two-component adhesives cured at RT: an epoxy (EP), a polyurethane (PU), and an acrylate system (AC). Based on Dynamic Mechanical Analysis, the glass transition temperatures of the EP, PU, and AC adhesives are 56.5, 102.9, and 111.9 °C, respectively. The AC adhesive exhibits the highest shear strength and displacement at failure, reflecting a superior load-bearing capacity. Fractographic analysis further supports these findings: AC joints show a mixed substrate/cohesive failure mode, while EP samples fail exclusively by adhesion failure and PU samples predominantly by a mixture of special cohesion, adhesion and substrate failure. Regarding processing, the EP samples show the highest pot life, followed by PU and then AC. Nonetheless, the pot life of the AC adhesive does not limit its range of application.. The results highlight the advantages of adhesive bonding of Elium© in enabling lightweight and more circular composites. RT-cured adhesives eliminate the need for drilling and energy-intensive thermal curing, allowing design flexibility and reductions in CO2 footprint within composite production.

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

Fibre-reinforced composites play a significant role in lightweight construction due to their high strength and stiffness relative to weight. Compared to metals, their lower weight increases the efficiency of transportation systems such as aircraft, rail vehicles, ships, and automobiles [1,2]. While fibre-reinforced composites usually demonstrate a positive environmental footprint in these applications, their energy-intensive production and recycling processes still leave room for improvement. Many composites currently used in industry are not recyclable, or their components can only be reused through downcycling processes. For instance, this can involve shredding the composite material, which turns continuous fibres into short ones [3]. Separation of the matrix and fibres is also possible using pyrolysis. However, even then, the materials lose their outstanding properties—such as high specific strengths. Therefore, recyclable matrix systems are a necessary advancement to allow for more resource-efficient and energy-saving production.

Thermoset composites can be considered the state-of-the-art matrix system for structural applications. At the same time, owing to their densely cross-linked molecular structure, they face strong challenges regarding their recyclability [4,5], which hinders the efficiency of standard recycling approaches. In contrast, thermoplastic composites are much more beneficial with regard to recyclability, as they can be melted, shaped, repaired, and reused [6]. Nonetheless, a limiting factor for the high-scale use of thermoplastic composites lies in the high viscosity of resin systems that either demand high pressure and temperature during production or impede production altogether [7].

To combine the positive properties of thermoplastics with the high strength and low melt viscosities of thermosets, alternatives have been explored [8]. One such alternative is the class of materials known as vitrimers. They are characterised by dynamic covalent bonds for materials such epoxies [9], benzoxazines [10], and polyurethanes [11]. Another approach to combine the advantages of thermosets and thermoplastics is the reactive processing of liquid thermoplastic resins. For commercial applications, this has been widely established by Elium©, an acrylic-based system developed by Arkema SA (Colombes, France). As a matrix system, Elium© can be combined with a wide range of fibres, e.g., carbon [12], glass [13], aramid [14], and natural fibres [15,16]. On this matter, a recent study revealed that glass presented the best adhesion to the Elium© matrix system [14].

Besides the manufacturing of laminates, the joining of composite parts is essential for effective construction of lightweight structures. Previous studies have shown that Elium© can be welded [17], adhesively bonded [18], and mechanically joined [18]. In this regard, structural adhesive bonding presents several advantages in terms of multi-material joining, continuous load distribution, and weight reduction by eliminating the need for mechanical fasteners [19,20]. Furthermore, the continuous fibres of the composite laminate are not interrupted by holes or notches required for mechanical fastening [21].

Banea et al. [22] presented an overview of chemical classes for the adhesive bonding of composites, as follows:

- Epoxy (EP) adhesives are characterised by high strength and temperature resistance, relatively low curing temperatures, easy processing, and low cost. Their application temperature range is between −40 °C and +100 °C (up to 180 °C for certain types). One-component epoxies cure under heat, while two-component epoxies cure at room temperature, with the possibility of accelerated polymerisation by elevated temperatures.

- Acrylic (AC) adhesives are versatile bonding agents with rapid curing, capable of adhering even to less clean or poorly prepared surfaces. They can be used within a temperature range of −40 °C to +120 °C and cure through a radical mechanism at room temperature.

- Polyurethane (PU) adhesives exhibit good flexibility at low temperatures, excellent fatigue resistance, high impact toughness, and long-term durability. Their application temperature range is from −200 °C to +80 °C, and they can also be cured at room temperature.

Moreover, another relevant aspect of adhesive selection is the adhesive’s glass transition temperature (Tg), as this influences key performance characteristics across temperature ranges. Below its Tg, an adhesive behaves in a “glassy” state—exhibiting high stiffness, dimensional stability, and cohesive strength—whereas above Tg, it becomes more flexible and rubbery. This transition critically affects bonded joints, being a direct decision-making parameter for the operational temperature of adhesives [23].

Kayba et al. [18] investigated adhesive bonding of glass-fibre Elium© using epoxy and Elium© itself as adhesives, in which Elium© had a better performance than epoxy. Koumba et al. [24] also used Elium© as an adhesive for Elium© composite laminates to successfully repair damaged structures. However, in all cases, curing took place at elevated temperatures above room temperature (RT), which limits processing due to the requirement of thermal heating equipment.

1.2. Research Gap and Aim

Even considering the existing research works, there are still relevant adhesive classes that were not taken into account in investigations, as well as other aspects such as glass transition temperature, RT curing, processing, chemical compatibility, and ease of handling that are essential for the selection of adhesives for structural bonding of Elium©-based composite laminates.

The current work presents an investigation on the structural adhesive bonding of glass-fibre-reinforced (GFRP) Elium© composite laminates. The focus lies on adhesive selection, evaluating the following three commercially available two-component adhesives under room-temperature curing: one epoxy, one polyurethane, and one acrylate. Single-lap joints serve as reference samples. The adhesives are evaluated based on the following criteria: adhesion to Elium© GFRP substrates, lap-shear strength, glass transition temperature, ease of processing, and manufacturing of adhesive joints.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The methyl-methacrylate-based matrix system was a mixture of vacuum-infusion-optimised formulations consisting of 49% Elium© 151 XO and 49% Elium© 191 SA, as well as 2% of peroxide hardener Metox 50 W. E-glass was employed in the form of non-crimp fabrics (NCFs), as follows:

- ▪

- 0°: Saertex U-E-640 g/m2-1260 mm, Areal weight of 640 g/m2

- ▪

- 0°/90°: Saertex B-E-625 g/m2-1270 mm. Areal weight of 625 g/m2

- ▪

- ±45°: Saertex X-E-610 g/m2-1270 mm, Areal weight of 610 g/m2

For the acrylate adhesive, a product from Henkel (Dusseldorf, Germany) designated as Loctite® AA V1315 was applied. The polyurethane adhesive used, Loctite® UK 1351, and the epoxy adhesive, Loctite® EA 3423, are also manufactured by Henkel. Selected physical and mechanical properties from technical datasheets of the adhesives are given in Table 1. Pot life describes the time span during which the mixed adhesive remains usable before it starts to cure/harden. Handling time is the minimum time required after application before the bonded parts can be moved or processed without compromising the bond. A special alcohol-based cleaning/primer agent, Teroson© SB450, was used to wipe clean the laminate surfaces before bonding.

Table 1.

Adhesive properties according to supplier’s data sheet.

2.2. Manufacturing of Composite Laminate Using Vacuum Infusion

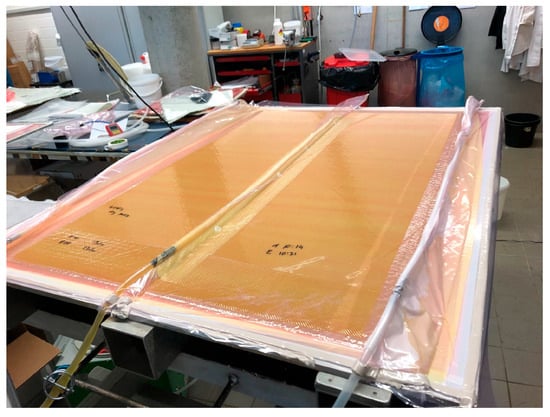

The vacuum infusion setup (see Figure 1) was assembled on an aluminium plate, following a carefully arranged stacking sequence from bottom to top. The layup began with a release film made of ETFE (WL 5200R), followed by a layer of peel ply (Release Ply 960). Next, 12 layers of glass fabric with a layup [±45/0/0/±45/0–90/0]S were placed, topped again with a layer of the same peel ply. Above these came the mesh flow, a breather cloth, and finally the vacuum film (Securlon® L1000). Inlet and outlet hoses were attached to facilitate resin infusion. Once the vacuum bag was sealed, a negative pressure of approximately 10 mbar was applied to evacuate trapped air and enable complete impregnation of the fibres with resin. Further information on the manufacturing of the laminate, including infusion setup and the laminate’s cross section, can be found in the work of Beber et al. [28].

Figure 1.

Vacuum infusion setup.

According to the datasheet specifications, the composite laminates were subsequently post-cured at 80 °C for two hours to achieve optimal mechanical properties. The substrates for lap-shear joints were cut into a final geometry of 30 × 120 mm2 from a larger plate using water-jet cutting.

2.3. Manufacturing of Adhesively Bonded Lap-Shear Samples

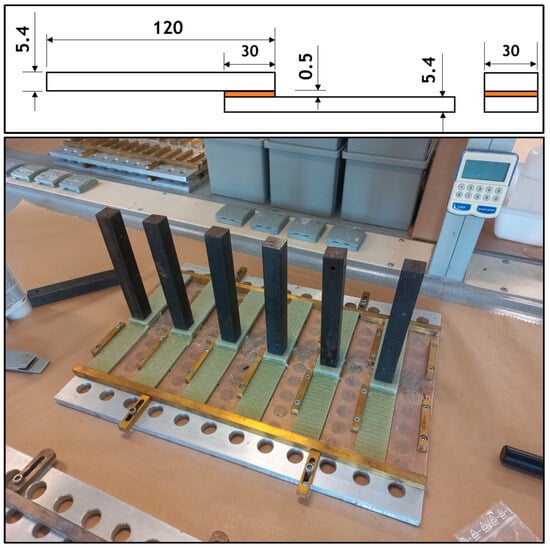

Adhesively bonded lap-shear samples were manufactured, as shown in Figure 2 (top), with substrates measuring 30 mm × 120 mm (width × length) with an overlap length of 30 mm, resulting in a nominal bonded area of 30 mm × 30 mm.

Figure 2.

Manufacturing of lap-shear samples (herein bonded with the PU adhesive): geometric dimensions with orange indicating the adhesive layer (top) and bonding fixture device (bottom).

Sample alignment and overlap length were ensured by using a bonding device, Figure 2 (bottom), in which six samples were bonded at the same time. To achieve a nominal adhesive layer thickness of 0.5 mm, glass beads with diameters between 420 µm and 590 µm (PQ Potters Europe, Wurzen, Germany) were employed. The use of glass beads is a widespread method to ensure a controlled adhesive layer thickness (see Refs. [29,30,31]).

Surface preparation consisted of the removal of the peel ply, followed by wipe application of the cleaning/primer agent Teroson© SB450. After waiting 10 min for the flash time of the agent, adhesives were applied using a handheld cartridge gun, then the glass beads were spread over the bonding surface. Final steps included the pressing together of the substrate pairs and the use of weights over the bonding surface. Curing occurred at RT for at least one week. For quality control, the adhesive layer thickness was measured using a digital calliper MarCal 16 EWRi (Mahr GmbH, Göttingen, Germany).

2.4. Characterisation of Adhesives and Joints

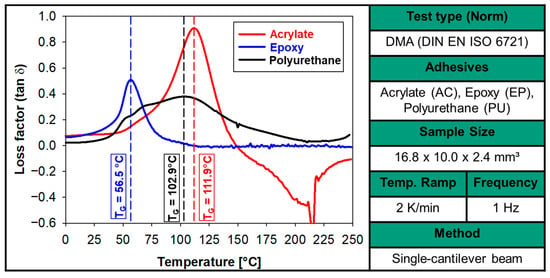

2.4.1. Glass Transition Temperature Determination Using Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

For the determination of the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the adhesives, the Dynamical Mechanical Analysis (DMA) technique according to DIN EN ISO 6721 [32] was employed. Sample size was around 16.8 × 10.0 × 2.4 mm3. The equipment was the DMA Q800 (TA Instruments, Eschborn, Germany) with the single-cantilever beam method using a temperature rate of 2 K/min and a frequency of 1 Hz. The temperature range of analysis lay between 0 and 250 °C.

2.4.2. Lap-Shear Testing

For the lap-shear testing, the adhesively bonded joints were tested with a load cell of 250 kN in a servo hydraulic tensile testing machine (Model 810) from MTS (Berlin, Germany). Based on the standard DIN EN 1465 [33], tests were carried out in a controlled lab facility under 23 °C and 50% R.H. To ensure proper load alignment and minimise bending moments during testing, doublers were bonded to the clamping region to compensate for the offset due to the overlapping geometry, as shown in Figure 3. The test speed was 1 mm/min. The free length between the unclamped regions amounted to 150 mm. Six samples per adhesive were tested. Crosshead machine displacement and force were measured directly by the testing machine.

Figure 3.

Experimental setup for the lap-shear testing in 250 kN machine (MTS model 810).

As seen in Equation (1), the shear strength ( was calculated by the ratio between the maximum applied force () and the nominal bonding surface, with the latter obtained by the overlap length () multiplied by the sample’s width (. The sample’s stiffness (Equation (2)) was obtained as the linear slope of the force-displacement curve between 1000 and 2000 N of force, as follows:

2.4.3. Fracture Surface Analysis

The fracture surface analysis was carried out according to DIN EN ISO 10365 [34]. Optical microscopy images were taken with a digital microscope VHX-7000 (Keyence Deutschland GmbH, Neu-Isenburg, Germany). For failures on the substrate laminate, the following fracture classes were identified: substrate failure (SF), cohesive substrate failure (CSF), and delamination failure (DF). Similarly, for failure on the adhesive layer, the classes of cohesion failure (CF), special cohesion failure (SCF), and failure with stress whitening of the adhesive (SWCF) were taken into account. Each sample was analysed using the Version 1.54 of the Software Image J, and then the average for the testing set was obtained.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Glass Transition Temperature of Adhesives

The DMA results for loss factor (tan δ) as a function of temperature for all three adhesives are plotted together in Figure 4. The peak of the loss factor was interpreted as the glass transition temperature (Tg) [35]. The obtained Tg of the epoxy, polyurethane, and acrylate adhesives was 56.5, 102.9, and 111.9 °C, respectively. These differences in Tg have direct implications for their structural performance on the adhesive bonding of Elium® GFRP composites. The relatively low Tg of the epoxy system limits its applicability in environments with elevated service temperatures, where stiffness and load-bearing capacity would decrease above 50 °C. In contrast, the polyurethane adhesive demonstrates a robust thermal performance with slightly more flexibility than the acrylate. The acrylate adhesive, exhibiting the highest Tg values, is expected to retain its mechanical integrity and load transfer capability even under higher operational temperatures, which is advantageous for applications involving heat exposure.

Figure 4.

DMA results of loss factor (tan δ) as a function of temperature for all three adhesives.

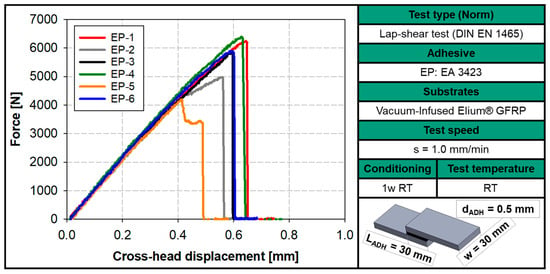

3.2. Epoxy (EP) Adhesive

The results of force-displacement curves from six repetitions of lap-shear testing with the epoxy (EP) adhesive are illustrated in Figure 5. Relevant resulting parameters are given in Table 2. In addition to the parameters described in Section 2.3, is the adhesive layer and is the maximum displacement. Dimensional parameters of adhesive layer thickness exhibited slightly higher variation with a standard deviation of 30%. However, based on Pearson’s r analysis, there was no direct correlation between adhesive layer thickness and the shear strength (p = 0.692). In terms of processing, the epoxy adhesive showed excellent behaviour, as the pot life allowed for manufacturing without significant time limitations.

Figure 5.

Force-displacement results (six repetitions) of lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the epoxy (EP) adhesive.

Table 2.

Relevant parameters from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the EP adhesive.

The average maximum force was , which corresponds to an average shear strength of MPa. The average maximum displacement was mm. Finally, the average stiffness was .

As a reference, Kayba et al. [18] obtained shear strengths of 3.9 MPa (Elium© as adhesive) and 2.0 MPa (epoxy as adhesive) for the adhesive bonding of vacuum-infused glass-fibre-reinforced Elium©. The nominal substrate thickness was 3 mm, and the bonding surface amounted to 25 × 25 mm2. Therefore, the overall shear strength of the present work was above the benchmark values (even for bolted joints), with an important remark that thinner substrates can reduce the shear strength due to higher bending moments during testing [36].

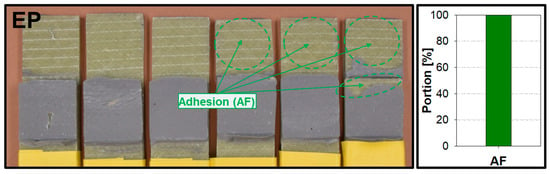

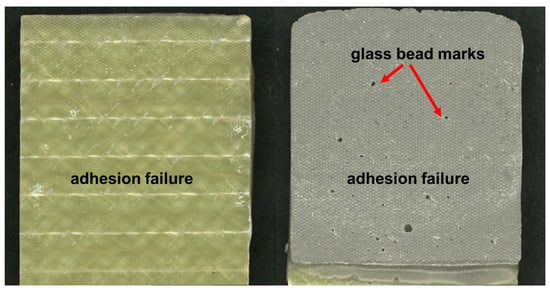

The fracture surfaces for each sample (EP-1 to EP-6 from left to right) are given in Figure 6, along with the surface classification. All samples showed 100% adhesive failure, which indicates a lack of compatibility between the EP adhesive and the Elium© substrates. More detailed optical microscopy of a representative sample (EP-5) is given in Figure 7. This behaviour is also seen in the force-displacement curve of the samples bonded with epoxy adhesive, implied as a sudden drop in force.

Figure 6.

Fracture surface analysis from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the EP adhesive.

Figure 7.

Detailed optical microscopy of a lap-shear sample (EP-5) of Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the EP adhesive.

This incompatibility of EP with thermoplastics, in general, has been reported in the literature, and it requires complex surface pre-treatments such as plasma activation or acid etching [37]. For this reason, efforts have been made in recent years to develop hybrid epoxy/MMA adhesives to improve bonding strength [38]. Therefore, it is expected that if the other adhesives (PU and AC) present improved adhesion to Elium©, the shear strength of adhesive joints could be improved.

3.3. Polyurethane (PU) Adhesive

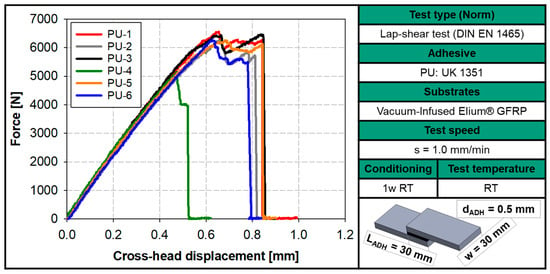

Force-displacement plots from six repetitions of lap-shear samples with the polyurethane (PU) adhesive are provided in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Force-displacement results (six repetitions) of lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the polyurethane (PU) adhesive.

Relevant resulting parameters are given in Table 3. The adhesive layer thickness of PU-bonded samples exhibited slightly higher variation compared to the EP adhesive, with a standard deviation of 37.7%. Based on Pearson’s r, PU samples showed no clear correlation between adhesive layer thickness and the attained shear strength (p = 0.992). Regarding processing, the polyurethane adhesive showed good behaviour. However, as the pot life of PU (20–30 min) was shorter than that of the EP adhesive (30–60 min), adhesive application might require more planning to avoid premature cure initiation before proper positioning.

Table 3.

Relevant parameters from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the PU adhesive.

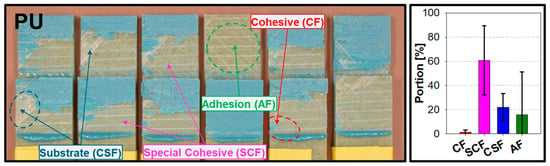

The average maximum force was , leading to an average shear strength of MPa. The average maximum displacement was mm. Finally, the average stiffness was . Compared to epoxy, polyurethane-bonded samples exhibited a higher shear strength and displacement, but with a slight reduction in stiffness. Likely, these higher values of shear strength could be associated with the higher proportion of cohesive failure on the adhesive layer, as shown in Figure 9. More detailed optical microscopy of a representative sample (PU-6) is shown in Figure 10. The dominant mechanism was special cohesion failure of the adhesive layer (SCF, 60.8 ± 28.5%), i.e., a substrate-close failure, but still with a thin layer of adhesive in both sides of the substrates. Cohesion (CF, 1.3 ± 2.0%) and cohesive substrate failure (CSF, 22.1 ± 11.4%) were also present, whereas the proportion of adhesive failure was around (AF, 15.8 ± 35.4%), compared to the 100% of the epoxy samples. The force-displacement curves also reflect this trend, as no sudden drop of force is seen (cf. Figure 8), but rather a serrated curve progression close to the failure.

Figure 9.

Fracture surface analysis from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the PU adhesive.

Figure 10.

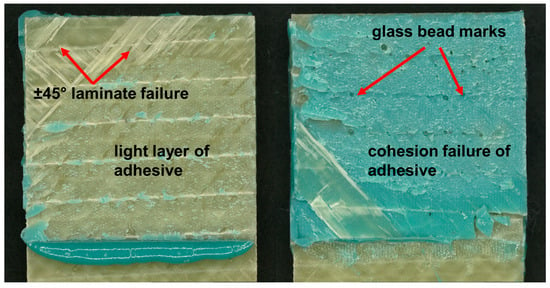

Detailed optical microscopy of a lap-shear sample (PU-6) of Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the PU adhesive.

3.4. Acrylate (AC) Adhesive

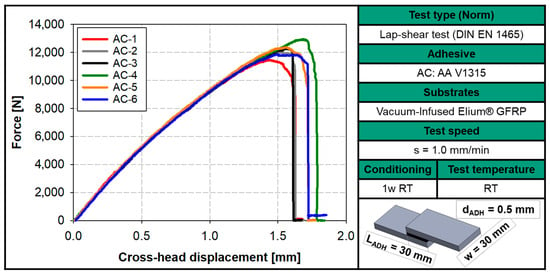

The resulting force-displacement curves of the lap-shear testing with the acrylate (AC) adhesive are shown in Figure 11. Key parameters are given in Table 4.

Figure 11.

Force-displacement results (six repetitions) of lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the acrylate (AC) adhesive.

Table 4.

Relevant parameters from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminate bonded with the EP adhesive.

Compared to the remaining adhesives, the variation in the adhesive layer thickness between samples was lower (16.2% of the mean value), which indicates a good manufacturing quality. At the same time, based on Pearson’s r analysis, there was no correlation between adhesive layer thickness and shear strength (p = 0.851). For processing, the acrylate adhesive had the shortest pot-life time window, a factor that demands planning with regard to sample positioning and manufacturing attention.

The average maximum force was , which corresponds to an average shear strength of MPa. These results are more than double those of the epoxy adhesives and nearly double those of the polyurethane adhesives. The average maximum displacement was mm. Again, these are significantly higher values, i.e., nearly triple those of the remaining adhesives. Taken together, the higher force and displacement values indicate an increased energy absorption capacity of the joints. Finally, the average stiffness of was smaller than that of epoxy and polyurethane, but only by 1.8 and 4.1%, respectively.

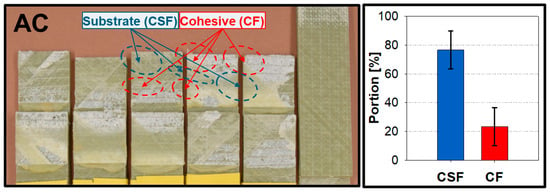

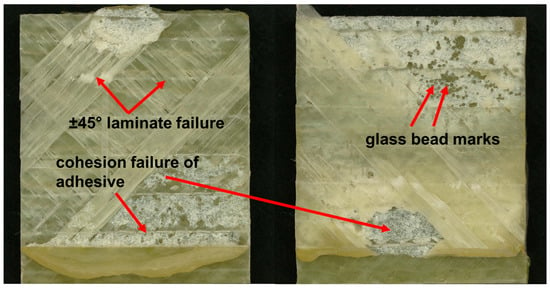

It is assumed that these significantly higher values of shear strength can be traced back to the chemical compatibility of the acrylate adhesive and the metha methilacrylate basis of the Elium© substrates. This was reflected on the fracture surface, see Figure 12, in which no adhesion failure was seen, but rather cohesive substrate failure (76.6 ± 13.1%) and cohesion failure of the adhesive layer (23.4 ± 13.1%). More detailed optical microscopy of a representative sample (AC-4) is provided in Figure 13. The force-displacement curve does not present a sudden drop in force; instead, an arch close to the failure is observable.

Figure 12.

Fracture surface analysis from the lap-shear testing of the Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the AC adhesive.

Figure 13.

Detailed optical microscopy of a lap-shear sample (AC-4) of Elium© GFRP laminates bonded with the AC adhesive.

3.5. Comparative Discussion

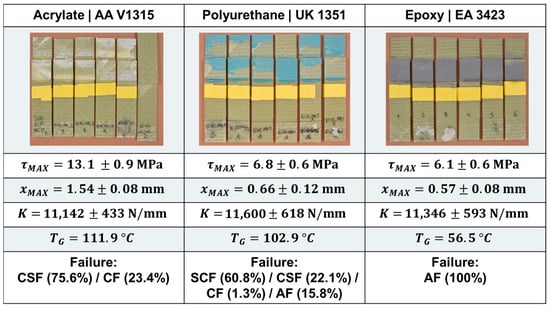

A summary of relevant results among the three adhesives under investigation is provided in Figure 14.

Figure 14.

Comparison of key parameters from lap-shear testing and DMA of adhesively bonded samples of GFRP-Elum© laminates with acrylate, polyurethane, and epoxy | CSF (cohesive substrate failure), CF (cohesion failure), SCF (special cohesion failure), and AF (adhesion failure).

In terms of glass transition temperature, the Tg of the epoxy, polyurethane, and acrylate adhesives was 56.5, 102.9, and 111.9 °C, respectively. Such results significantly limit the temperature application range of the EP adhesive, highlighting the advantages of the PU and AC adhesives, especially the latter.

The acrylate adhesive (AC) exhibited the highest shear strength and displacement at failure, indicating a superior load-bearing capacity and enhanced toughness compared to the epoxy (EP) and polyurethane (PU) systems. By carrying out a pairwise Welch’s t-test, there is no significant distinction in the lap-shear strength of the EP and PU adhesives (p = 0.163), whereas the AC-adhesive possesses a significantly higher strength than EP (p = 2.5 × 10−7) and PU (p = 4.2 × 10−9). Comparatively, the lap-shear strength results for all three adhesives were superior than benchmark values found in the literature [18].

It is assumed that these results can be associated with the excellent compatibility of the acrylate adhesive with Elium©, as they share a similar chemical basis. All adhesives exhibited similar stiffness values (K ≈ 11,000 N/mm).

The failure analysis further supports these findings: AC joints exhibited a mixed substrate/cohesive failure mode (CSF/CF), while EP samples failed exclusively by adhesion failure (AF) and the PU samples predominantly by a mixture of special cohesion failure, cohesive substrate failure, and adhesion failure (SCF/CSF/AF). Nevertheless, this also indicates that the thermoplastic components may suffer damage. Therefore, for reuse and recycling, a debonding strategy—beyond just mechanical separation—could be considered, as described in Refs. [39,40,41].

With regard to processing, the epoxy has the most favourable characteristics due to its comparatively longer pot life, followed by the polyurethane and the acrylate. However, the superior mechanical properties of the acrylate adhesive compensate for its shorter pot life.

4. Conclusions

The present study dealt with an investigation on the structural adhesive bonding of glass-fibre-reinforced thermoplastic Elium© composite laminates. Substrates were manufactured using vacuum infusion with a 12-layer composite layup of [±45/0/0/±45/0–90/0]S. The work focused on the evaluation of three commercially available two-component adhesives capable of curing at room temperature, namely an epoxy, a polyurethane, and an acrylate system. The evaluation criteria included adhesion to Elium© GFRP substrates, lap-shear strength, glass transition temperature, and the overall ease of processing and joint manufacturing.

The AC adhesive exhibited the highest shear strength and displacement at failure, reflecting a superior load-bearing capacity and adhesion to Elium© substrates. Fractographic analysis further supported these findings. Regarding Tg, both the AC and PU adhesives showed suitable results, with values of 111.9 and 102.9 °C, respectively. EP had a Tg of 56.5 °C, which considerably limits its application. In terms of processing, the epoxy exhibited the most favourable characteristics due to its relatively long pot life, followed by the polyurethane and then the acrylate. Nonetheless, the pot life of the acrylate adhesive does not limit its range of application.

Finally, it is important to highlight that the advantages of adhesive bonding of Elium© are numerous, such as no need for drilling and energy-intensive heating equipment due to room-temperature curing, flexibility of design, and adaptable manufacturing (handheld or automatised adhesive application). Taken together, these results evidence the relevance of adhesive bonding for enabling the next generation of lightweight and recyclable composite structures in fields such as railway, automotive and ship building, and on- and off-shore wind energy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.X.B. and V.C.B.; methodology, N.X.B., C.N. and V.C.B.; formal analysis, N.X.B., P.H.E.F., M.V., S.V. and V.C.B.; investigation, N.X.B., P.H.E.F. and V.C.B.; resources, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.X.B., M.V., S.V. and V.C.B.; visualization, N.X.B. and V.C.B.; supervision, C.N.; project administration, K.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy (BMWE) under the ID (Förderkennzeichen) 03LB2035A.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Henkel for the supplying of the adhesives and to Raul Renken and Theresia Hochleim for the scientific discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Giorgini, L.; Benelli, T.; Brancolini, G.; Mazzocchetti, L. Recycling of carbon fiber reinforced composite waste to close their life cycle in a cradle-to-cradle approach. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2020, 26, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Karl, C.W.; Gagani, A.I.; Jørgensen, J.K. Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Choudhary, P.; Krishnan, V.; Zafar, S. A review on recycling and reuse methods for carbon fiber/glass fiber composites waste from wind turbine blades. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 215, 108768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veers, P.; Bottasso, C.L.; Manuel, L.; Naughton, J.; Pao, L.; Paquette, J.; Robertson, A.; Robinson, M.; Ananthan, S.; Barlas, T.; et al. Grand challenges in the design, manufacture, and operation of future wind turbine systems. Wind Energ. Sci. 2023, 8, 1071–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.R.; Prabhakara, H.M.; Bramer, E.A.; Dierkes, W.; Akkerman, R.; Brem, G. A critical review on recycling of end-of-life carbon fibre/glass fibre reinforced composites waste using pyrolysis towards a circular economy. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhudolia, S.K.; Joshi, S.C. Low-velocity impact response of carbon fibre composites with novel liquid Methylmethacrylate thermoplastic matrix. Compos. Struct. 2018, 203, 696–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Yuksel, O.; Zanjani, J.S.M.; An, L.; Akkerman, R.; Baran, I. Experimental Investigation of the Interlaminar Failure of Glass/Elium® Thermoplastic Composites Manufactured With Different Processing Temperatures. Appl. Compos. Mater. 2022, 29, 1061–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishnaevsky, L., Jr. How to Repair the Next Generation of Wind Turbine Blades. Energies 2023, 16, 7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Builes Cárdenas, C.; Gayraud, V.; Rodriguez, M.E.; Costa, J.; Salaberria, A.M.; Ruiz de Luzuriaga, A.; Markaide, N.; Dasan Keeryadath, P.; Calderón Zapatería, D. Study into the Mechanical Properties of a New Aeronautic-Grade Epoxy-Based Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Vitrimer. Polymers 2022, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.; Pursche, L.; Boskamp, L.; Koschek, K. Amine Exchange of Aminoalkylated Phenols as Dynamic Reaction in Benzoxazine/Amine-Based Vitrimers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2024, 45, e2400557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Liang, X.; Zhang, J.; Lei, I.M.; Liu, J. Polyurethane vitrimers: Chemistry, properties and applications. J. Polym. Sci. 2023, 61, 2233–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhudolia, S.K.; Perrotey, P.; Joshi, S.C. Optimizing Polymer Infusion Process for Thin Ply Textile Composites with Novel Matrix System. Materials 2017, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obande, W.; Mamalis, D.; Ray, D.; Yang, L.; Ó Brádaigh, C.M. Mechanical and thermomechanical characterisation of vacuum-infused thermoplastic- and thermoset-based composites. Mater. Des. 2019, 175, 107828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaybal, H.B.; Ulus, H.; Cacik, F.; Eskizeybek, V.; Avci, A. Multi-Scale Mechanical Behavior of Liquid Elium® Based Thermoplastic Matrix Composites Reinforced with Different Fiber Types: Insights from Fiber–Matrix Adhesion Interactions. Fibers Polym. 2024, 25, 4935–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allagui, S.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.-L.; Beyaoui, M.; Bouguecha, A.; Haddar, M. Effect of Recycling Cycles on the Mechanical and Damping Properties of Flax Fibre Reinforced Elium Composite: Experimental and Numerical Studies. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 695–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilali, A.; Zouari, W.; Assarar, M.; Kebir, H.; Ayad, R. Analysis of the mechanical behaviour of flax and glass fabrics-reinforced thermoplastic and thermoset resins. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2016, 35, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, G.; Bhudolia, S.K.; Kantipudi, J.; Leong, K.F.; Barsotti, R.J. Ultrasonic welding of novel Carbon/Elium® with carbon/epoxy composites. Compos. Commun. 2020, 22, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaybal, H.B.; Ulus, H. Comparative analysis of thermoplastic and thermoset adhesives performance and the influence on failure analysis in jointed Elium-based composite structures. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 3474–3492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, N.; Beber, V.C.; Brede, M.; Koschek, K. Adhesively- and hybrid-bonded joining of basalt and carbon fibre reinforced polybenzoxazine-based composites. Compos. Struct. 2020, 236, 111800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, L.F.M.; Öchsner, A.; Adams, R.D. Handbook of Adhesion Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-55410-5. [Google Scholar]

- Budhe, S.; Banea, M.D.; de Barros, S.; Da Silva, L. An updated review of adhesively bonded joints in composite materials. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 72, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banea, M.D.; Da Silva, L.F.M. Adhesively bonded joints in composite materials: An overview. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2009, 223, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Azúa, O.R.; Agulló, N.; Arbusà, J.; Borrós, S. Improving Glass Transition Temperature and Toughness of Epoxy Adhesives by a Complex Room-Temperature Curing System by Changing the Stoichiometry. Polymers 2023, 15, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumba, N.; Boumbimba, R.M.; Bonfoh, N.; Eba, F.; Wary, M. Effect of reparation on the mechanical behavior of glass fibers/ E lium acrylic laminate composites: Experimental and numerical approaches. Polym. Compos. 2024, 45, 6385–6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henkel. Technical Datasheet: Loctite(R) AA V1315; Henkel: Dusseldorf, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Henkel. Technical Datasheet: Loctite(R) EA 3423; Henkel: Dusseldorf, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Henkel. Technical Datasheet: Loctite(R) UK1351/UK5452; Henkel: Dusseldorf, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beber, V.C.; Fernandes, P.H.E.; Nagel, C.; Arnaut, K. Integrated Analytical and Finite Element-Based Modelling, Manufacturing, and Characterisation of Vacuum-Infused Thermoplastic Composite Laminates Cured at Room Temperature. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.P.J.R.; Marques, E.A.S.; Carbas, R.J.C.; Gilbert, F.; Da Silva, L.F.M. Experimental Study of the Impact of Glass Beads on Adhesive Joint Strength and Its Failure Mechanism. Materials 2021, 14, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rządkowski, W.; Tracz, J.; Cisowski, A.; Gardyjas, K.; Groen, H.; Palka, M.; Kowalik, M. Evaluation of Bonding Gap Control Methods for an Epoxy Adhesive Joint of Carbon Fiber Tubes and Aluminum Alloy Inserts. Materials 2021, 14, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricca, F.; Galindo-Rosales, F.J.; Akhavan-Safar, A.; Da Silva, L.F.M.; Fkyerat, T.; Yokozeki, K.; Vallée, T.; Evers, T. Predicting the Adhesive Layer Thickness in Hybrid Joints Involving Pre-Tensioned Bolts. Polymers 2024, 16, 2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DIN EN ISO 6721; Plastics-Determination of Dynamic Mechanical Properties, German Version. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- DIN EN 1465; Adhesives-Determination of Tensile Lap-Shear Strength of Bonded Assemblies, German Version. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2009.

- DIN EN ISO 10365; Adhesives-Designation of Main Failure Patterns, German and English Versions. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2020.

- Henriques, I.R.; Borges, L.A.; Costa, M.F.; Soares, B.G.; Castello, D.A. Comparisons of complex modulus provided by different DMA. Polym. Test. 2018, 72, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Adams, R.D.; Da Silva, L.F. Experimental and numerical analysis of single-lap joints for the automotive industry. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2009, 29, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; de Souza, M.; Creighton, C.; Varley, R.J. New approaches to bonding thermoplastic and thermoset polymer composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2020, 133, 105870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennemann, K.K.; Lenz, D.M. Structural methacrylate/epoxy based adhesives for aluminIum joints. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 89, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.V.; Idapalapati, S. Review of debonding techniques in adhesively bonded composite structures for sustainability. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 30, e00345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veller, S.; Adam, M.; Hempel, M.; Rudlof, M. Improving the recyclability of rare earth magnets in electrical motors by using debonding-strategies. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 45, e01586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekas, V.; Arnaut, K.; Beber, V.C. Debonding-on-demand of vacuum-infused thermoplastic fibre-reinforced laminates with improved recyclability. J. Adv. Join. Process. 2025, 12, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.