An Energetic Analysis of Apparent Hardening and Ductility in FRP Plate Debonding

Abstract

1. Introduction

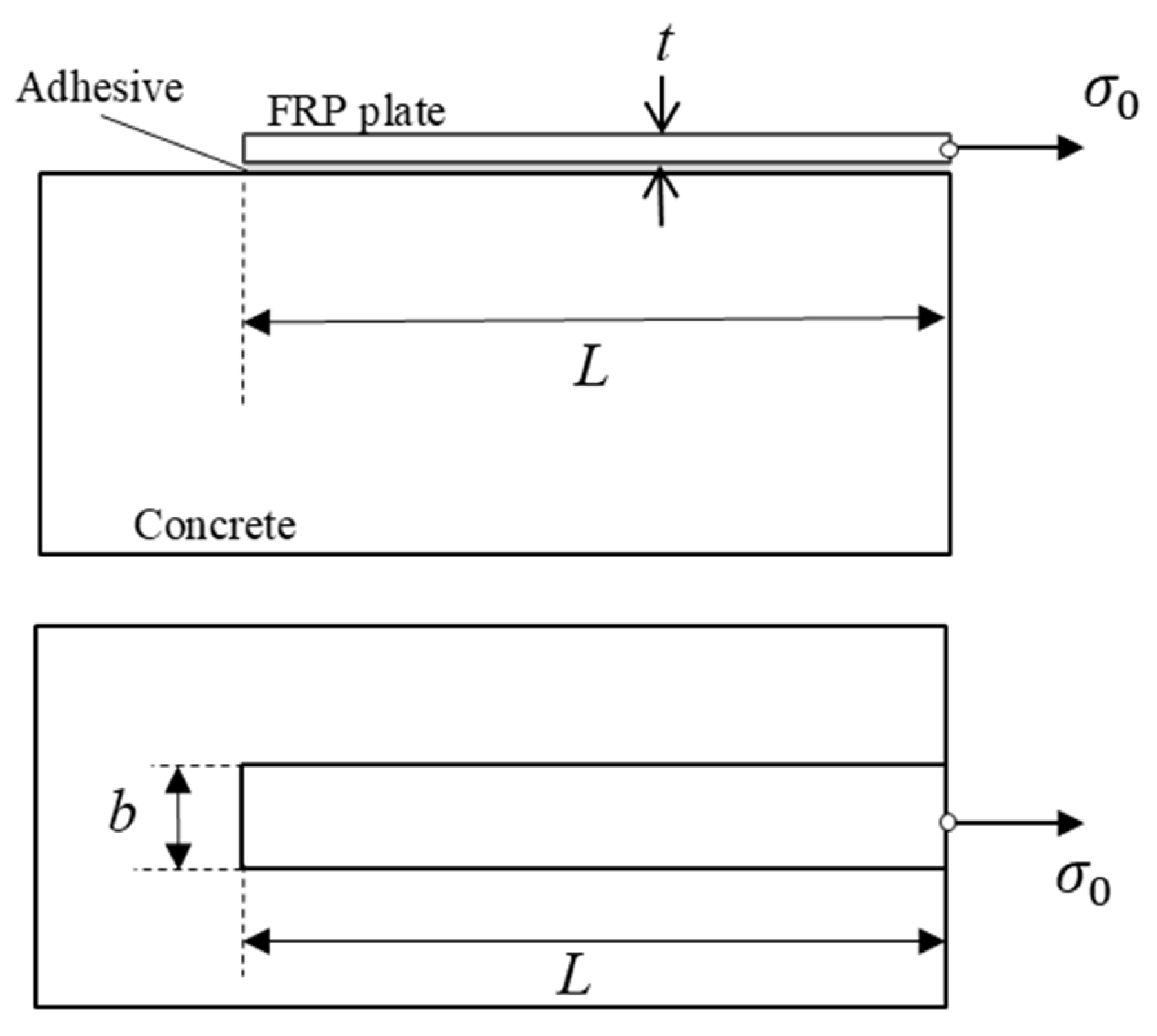

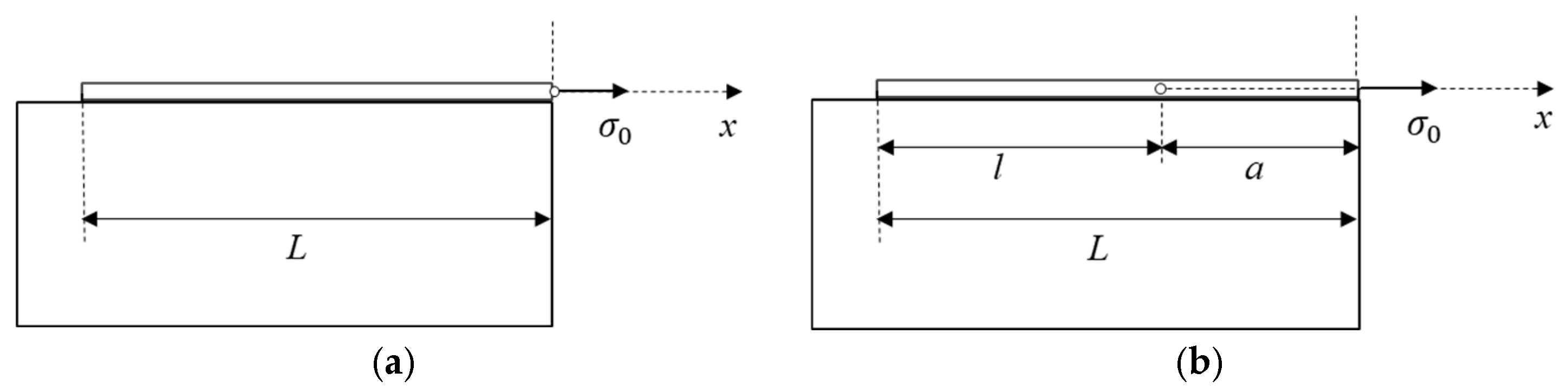

2. The Analytical Model

2.1. The Strengthening System

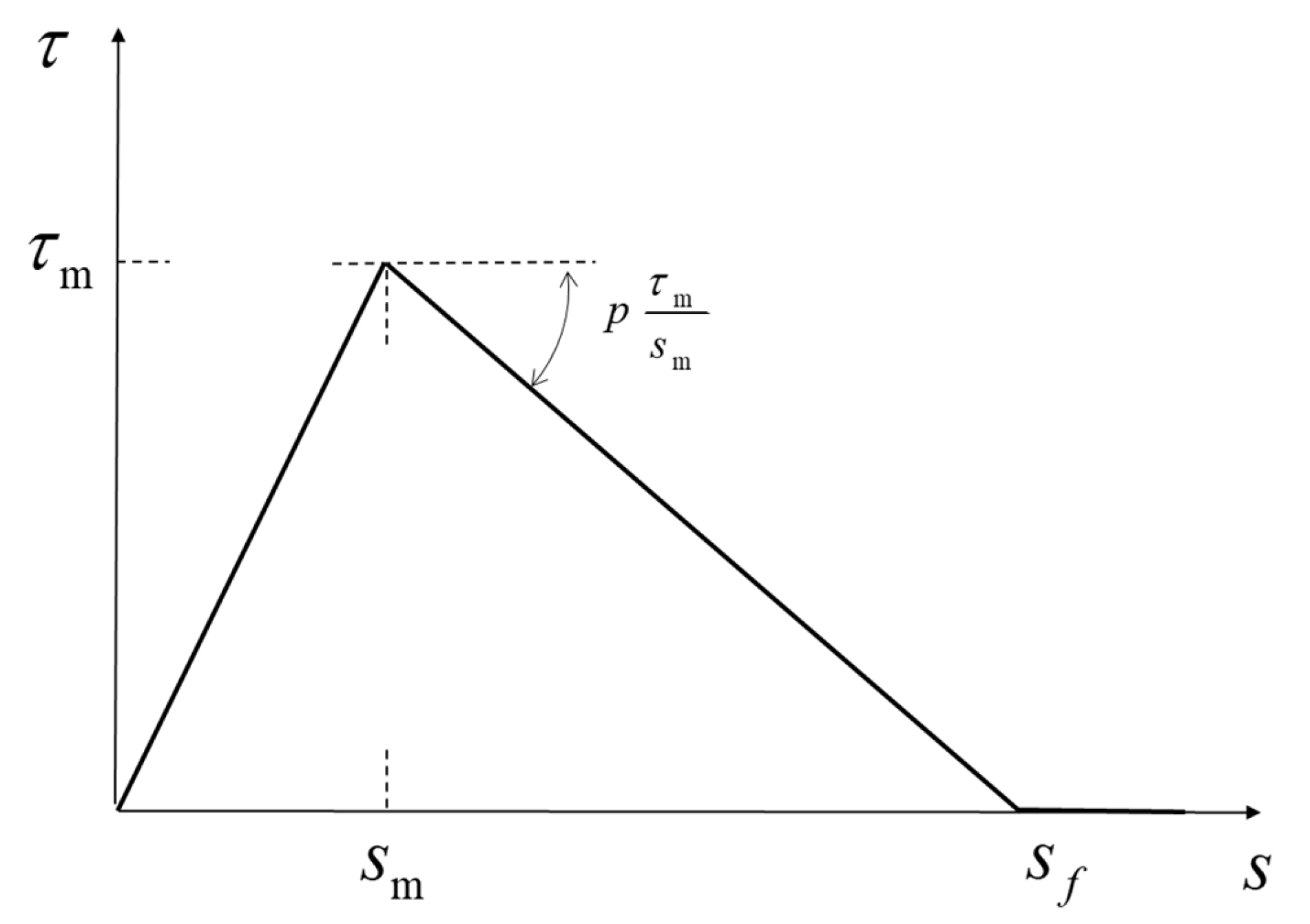

2.2. The Interface Cohesive Law and the Interface Fracture Energy

3. Analysis of Progressive Debonding

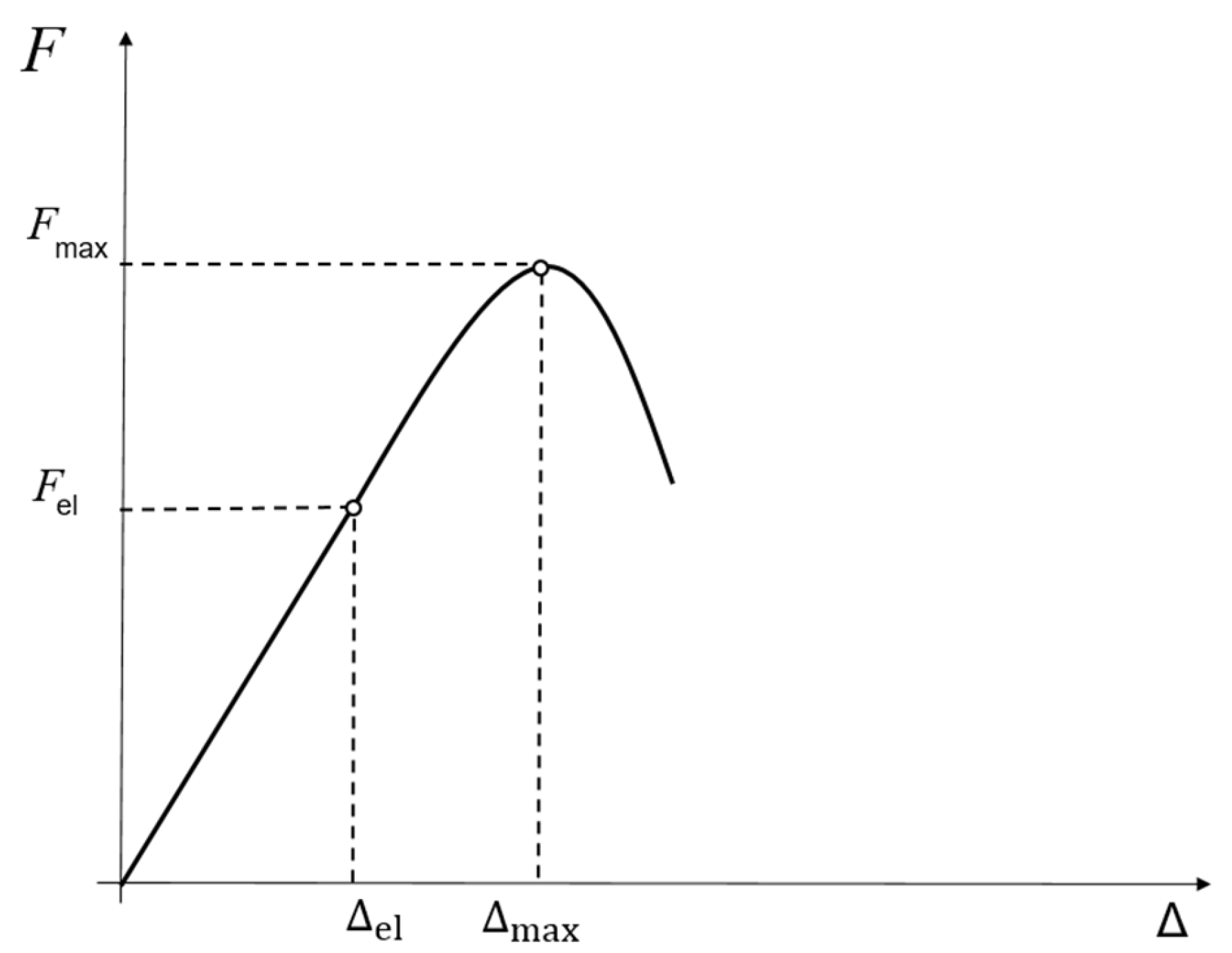

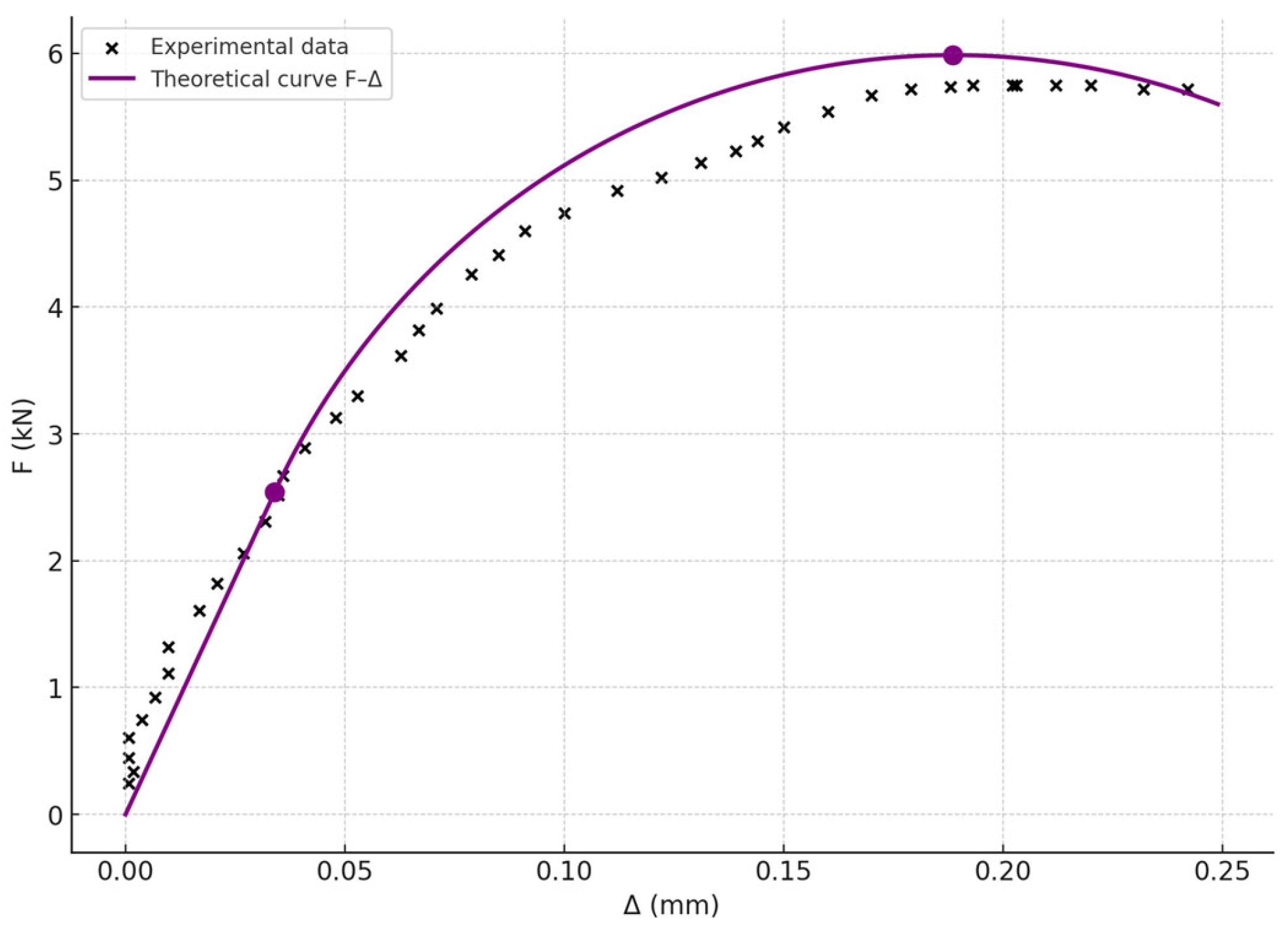

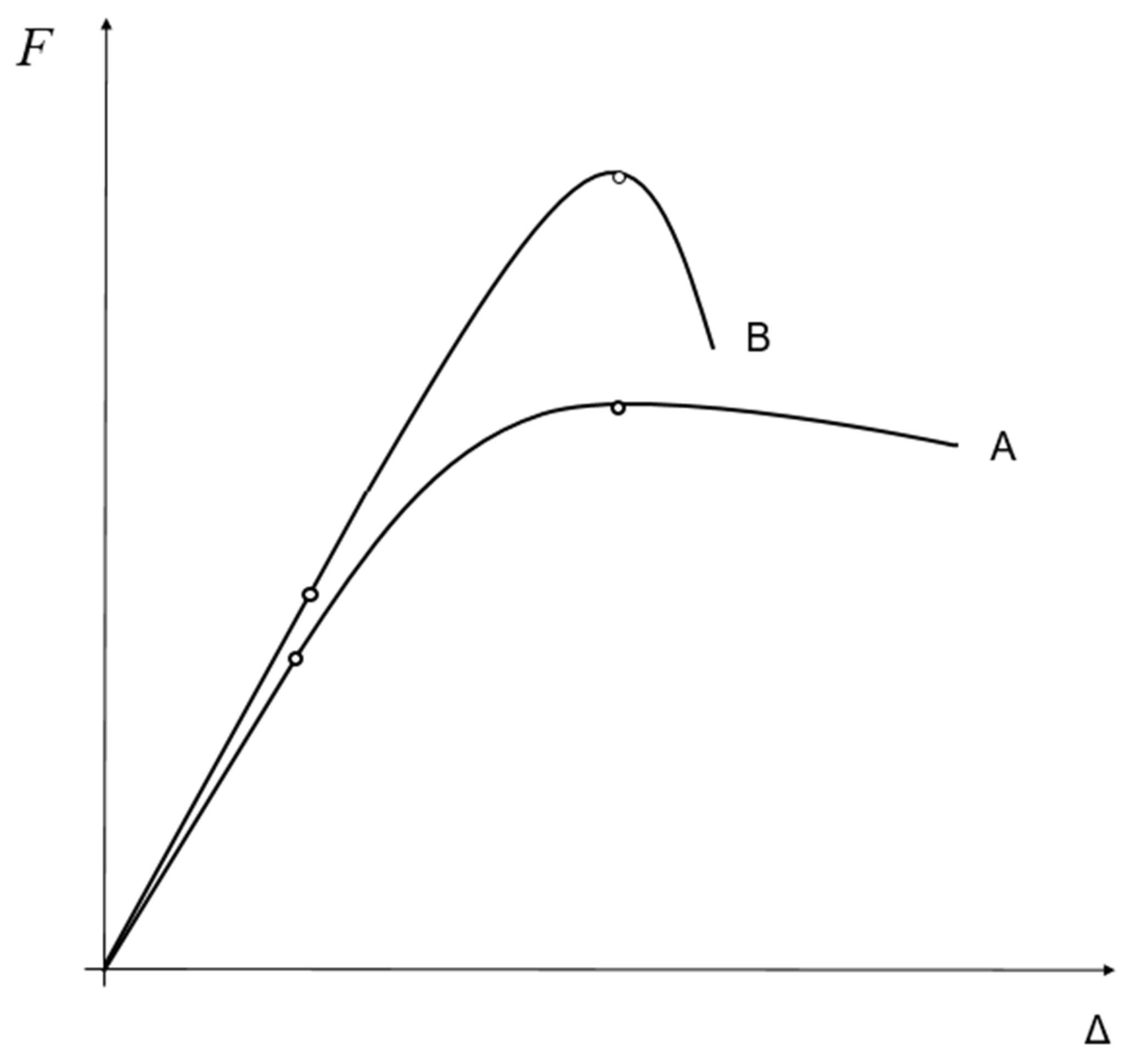

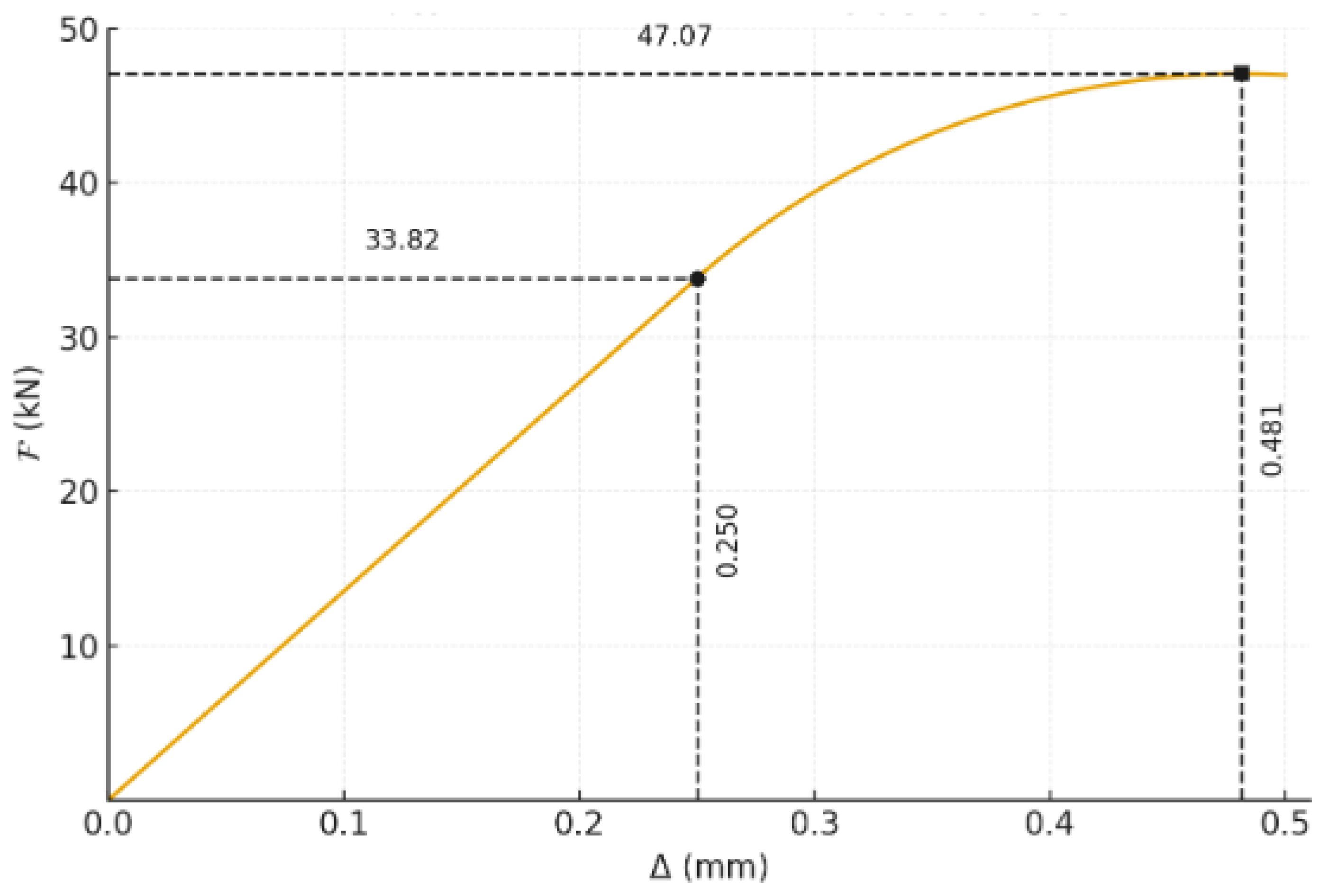

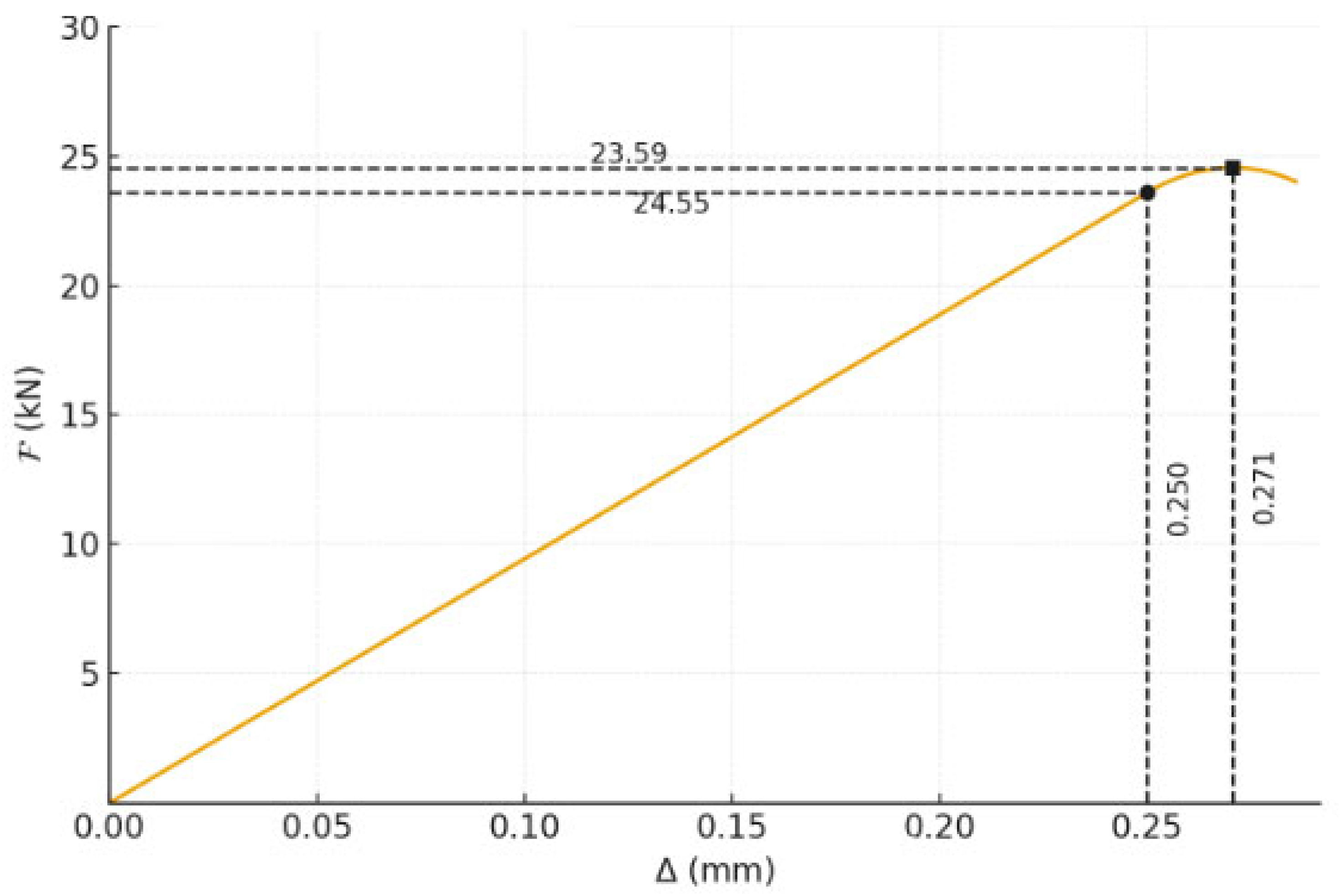

4. The Global System Response ( Curve)

- The elastic phase () (from the onset of loading up to the point (, )): The relationship is linear and is described by the elastic solution , with and .

- The progressive hardening phase (from to ): This is the curvilinear segment between the elastic limit and the maximum force. Even though the interface material at the loaded end has already entered its softening branch, the global resistance of the system continues to increase. This apparent system “hardening” is due to stress redistribution: as the damage zone grows, it “activates” new, undamaged sections of the elastic zone (Zone I) deeper in the anchorage, which contribute to the increase in total force. The curve here is constructed parametrically via the equations and .

- The peak : This is the point of maximum resistance. It occurs at the critical softening length .

- The descending branch after the peak : After the peak, the growth of the damage zone can no longer be compensated for by the activation of new elastic segments, and the total resistance of the system begins to decrease.

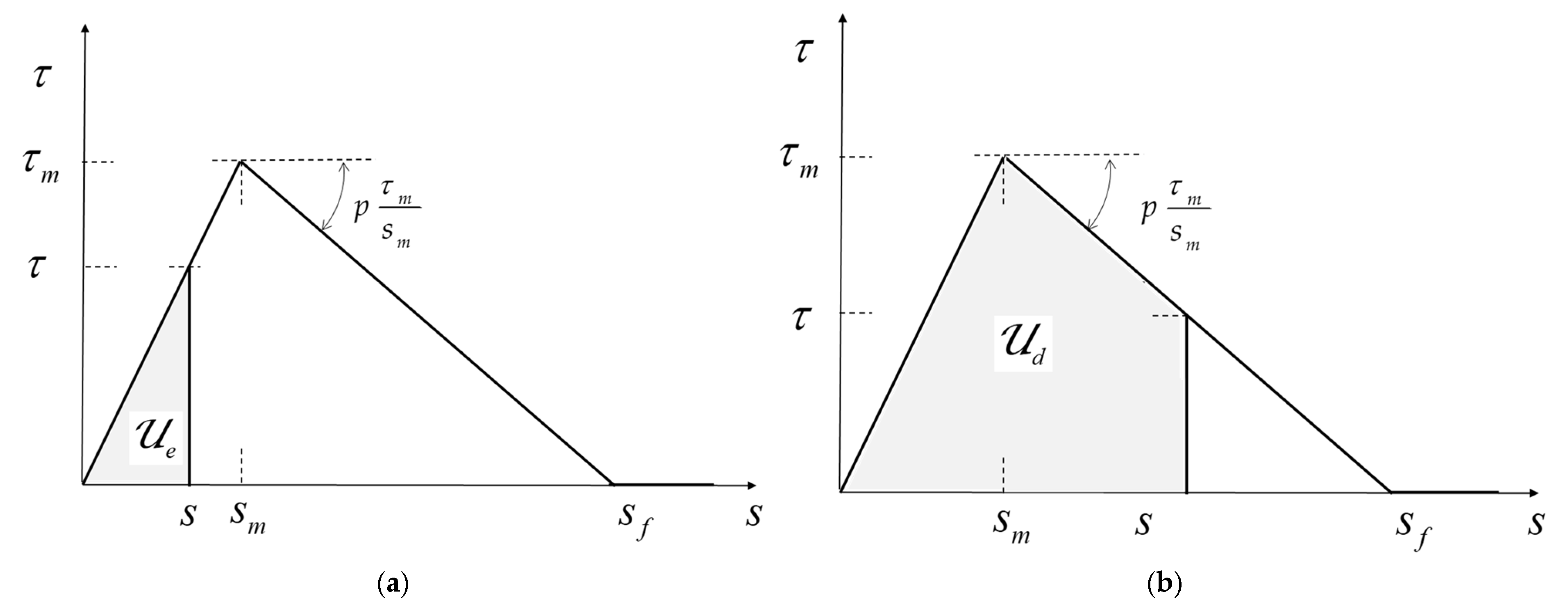

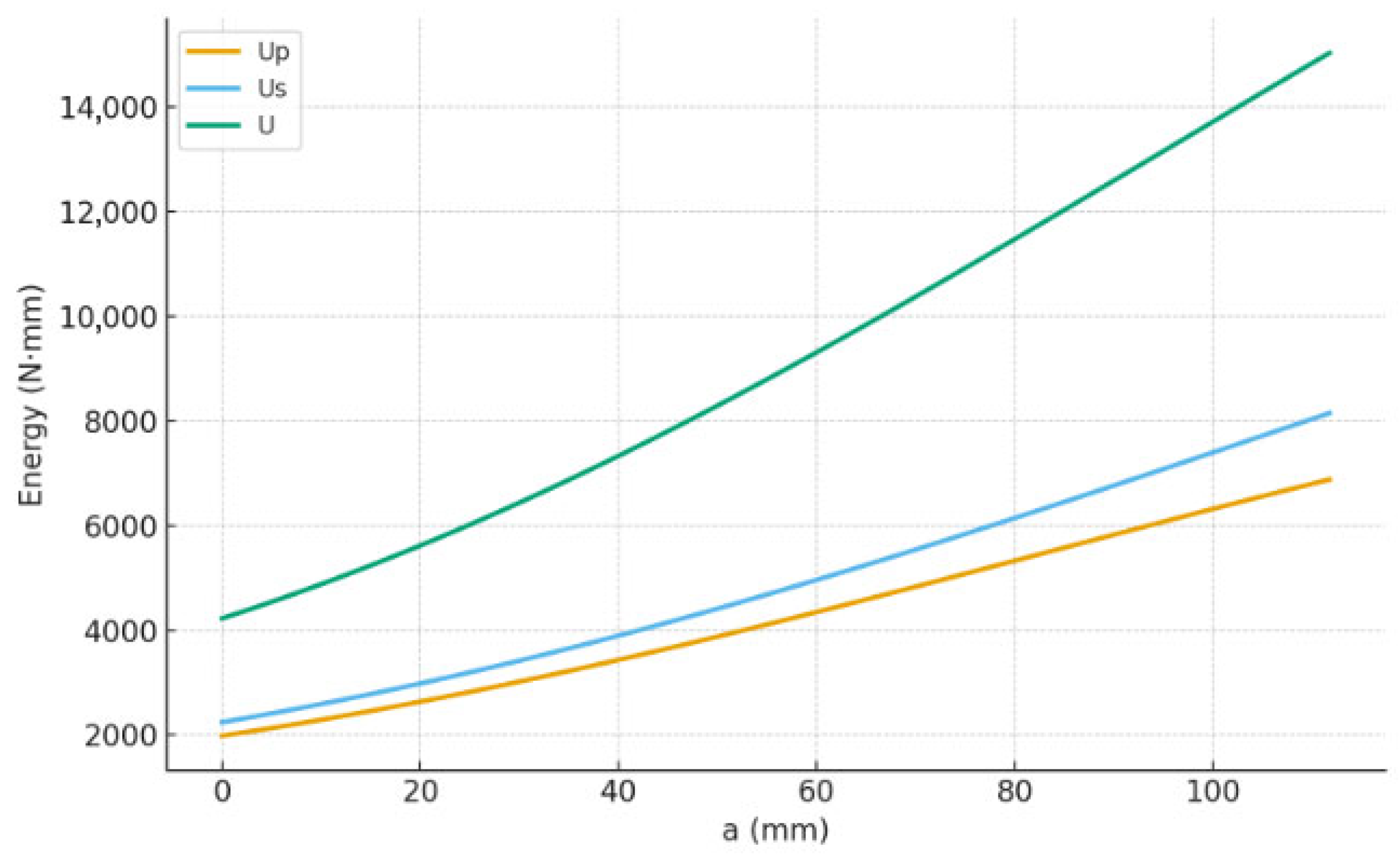

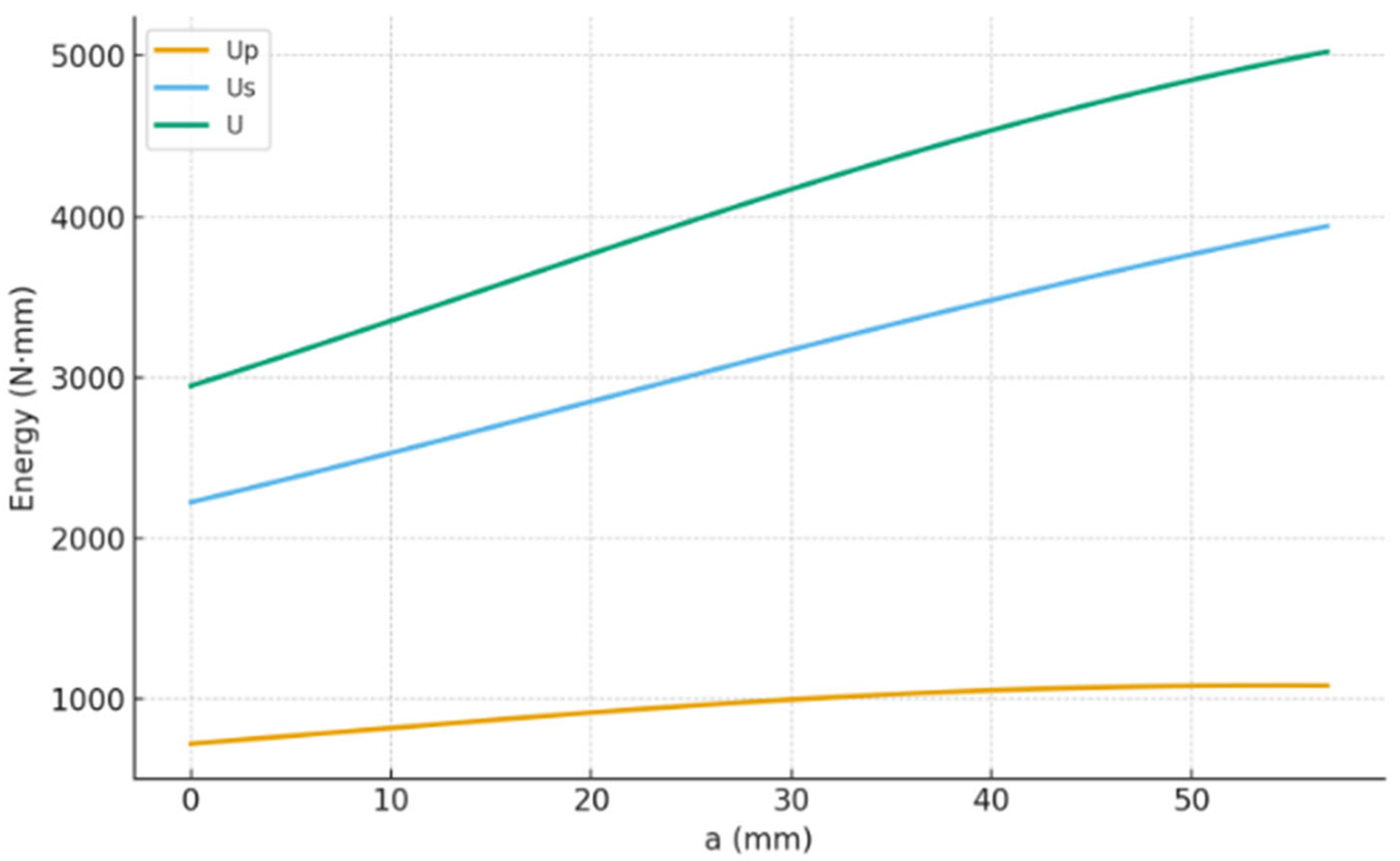

5. Energetic Analysis of Damage Evolution

5.1. Calculation of Energy Components

5.2. The Energy Balance

5.3. Energetic Investigation of Apparent Hardening

6. Ductility and Toughness

7. Conclusions and Discussion

- The non-linear “apparent hardening” phase observed in the curve is not an intrinsic material property. It was demonstrated to be a structural phenomenon caused by stress redistribution. As the softening zone steadily develops, it “activates” new, intact sections of the elastic anchorage zone, allowing the system to take on increasing load.

- The apparent hardening phase terminates when the maximum force, , is reached. This occurs at a specific, critical length of the softening zone , at which point the rate of strength loss from damage overcomes the rate of strength gain from redistribution.

- We developed a complete energy balance, deriving analytical expressions for all energy components. The analysis confirmed that the progressive failure consistently follows fracture mechanics principles, maintaining the condition throughout the propagation.

- The energetic analysis revealed the critical “dual” nature of the hardening phase. While this phase allows for load increase, it is simultaneously the period during which the system stores vast amounts of elastic energy (primarily in the FRP), acting as an “engine” for potential unstable failure.

- We demonstrated a clear distinction between toughness (the total area of the curve) and ductility (defined as the stability of the post-peak failure, i.e., the capacity for a gentle “plateau”). It was proven that brittle, violent “snap-back” failure is the result of the uncontrolled release of excess stored elastic energy. This occurs when the interface’s energy dissipation capacity is insufficient to manage the “engine” of stored energy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ACI 440.2R-17; Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Concrete Structures. American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2017.

- Neale, K. Manual No. 4—Strengthening Reinforced Concrete Structures with Externally-Bonded Fibre Reinforced Polymers (FRPs); ISIS Canada Research Network: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, T.; Dai, J. Interface bond between FRP sheets and concrete substrates: Properties, numerical modeling and roles in member behaviour. Prog. Struct. Eng. Mater. 2005, 7, 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Teng, J.G.; Chen, J.F. Experimental study on FRP-to-concrete bonded joints. Compos. Part B Eng. 2005, 36, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.Z.; Teng, J.G.; Ye, L.P.; Jiang, J.J. Bond–slip models for FRP sheets/plates bonded to concrete. Eng. Struct. 2005, 27, 920–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lorenzis, L.; Miller, B.; Nanni, A. Bond of FRP laminates to concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2001, 98, 256–264. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=88233f963f62689622cfa44ceb217cf615cc5516 (accessed on 1 May 2001).

- Biscaia, H.C.; Chastre, C.; Silva, M.A.G. Linear and nonlinear analysis of bond-slip models for interfaces between FRP composites and concrete. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 45, 1554–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Debonding of FRP-plated reinforced concrete beam, a bond-slip analysis. I. Theoretical formulation. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2006, 43, 6649–6664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Teng, J.G. Anchorage Strength Models for FRP and Steel Plates Bonded to Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2001, 127, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diab, H.M.; Farghal, O.A. Bond strength and effective bond length of FRP sheets/plates bonded to concrete considering the type of adhesive layer. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 618–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, R.; Paulay, T. Reinforced Concrete Structures; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Bažant, Z.P. Size effect in blunt fracture: Concrete, rock, metal. J. Eng. Mech. 1984, 110, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduini, M.; Di Tommaso, A.; Nanni, A. Brittle failure in FRP plate and sheet bonded beams. ACI Struct. J. 1997, 94, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Täljsten, B. Strengthening of concrete prisms using the plate-bonding technique. Int. J. Fract. 1996, 82, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achintha, P.M.M.; Burgoyne, C.J. Fracture mechanics of plate debonding. J. Compos. Constr. 2008, 12, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, C.K.Y.; Yang, Y. Energy-based modeling approach for debonding of FRP plate from concrete substrate. J. Eng. Mech. 2006, 132, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Yuan, H.; Teng, J.G. Debonding failure along a softening FRP-to-concrete interface between two adjacent cracks in concrete members. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, S.A.; Colombi, P.; D’Antino, T. Analytical solution of the bond behavior of FRCM composites using a rigid-softening cohesive material law. Compos. Part B Eng. 2019, 174, 107051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, U.; Greco, F.; Leonetti, L.; Nevone Blasi, P.; Pranno, A. Debonding failure analysis of FRP-plated RC beams via an inter-element cohesive fracture approach. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2022, 39, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, U.; Greco, F.; Leonetti, L.; Nevone Blasi, P.; Pranno, A. An investigation about debonding mechanisms in FRP-strengthened RC structural elements by using a cohesive/volumetric modeling technique. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2022, 117, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, F.; Leonetti, L.; Luciano, R.; Nevone Blasi, P.; Pranno, A. Nonlinear effects in fracture induced failure of compressively loaded fiber reinforced composites. Compos. Struct. 2018, 189, 688–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranno, A.; Greco, F.; Lonetti, P.; Luciano, R.; De Maio, U. An improved fracture approach to investigate the degradation of vibration characteristics for reinforced concrete beams under progressive damage. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 163, 107032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghabagloo, M.; Carreras, L.; Prasad, M.; Codina, A.; Baena, M. Assessment of the Experimental and Numerical Bond–Slip Law of Various Strengthening Systems in Reinforced Concrete Elements. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2025, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Gu, L.; Wu, R.Y.; Li, Y.; Sheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Lu, S. A deformability-based mechanical model for predicting shear strength of FRP-strengthened RC beams failed in concrete cover separation. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2024, 311, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C. From Micromechanics to Structural Engineering—The Design of Cementitious Composites for Civil Engineering Applications. Struct. Eng./Earthq. Eng. 1993, 10, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNR-DT 200 R1/2013; National Research Council of Italy, Guide for the Design and Construction of Externally Bonded FRP Systems for Strengthening Existing Structures. Advisory Committee on Technical Recommendations for Construction: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Yuan, H.; Teng, G.J.; Seracino, R.; Wu, S.Z.; Yao, J. Full-range behavior of FRP-to-concrete bonded joints. Eng. Struct. 2004, 26, 553–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mitsopoulou, N.; Kattis, M. An Energetic Analysis of Apparent Hardening and Ductility in FRP Plate Debonding. J. Compos. Sci. 2026, 10, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010007

Mitsopoulou N, Kattis M. An Energetic Analysis of Apparent Hardening and Ductility in FRP Plate Debonding. Journal of Composites Science. 2026; 10(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleMitsopoulou, Nefeli, and Marinos Kattis. 2026. "An Energetic Analysis of Apparent Hardening and Ductility in FRP Plate Debonding" Journal of Composites Science 10, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010007

APA StyleMitsopoulou, N., & Kattis, M. (2026). An Energetic Analysis of Apparent Hardening and Ductility in FRP Plate Debonding. Journal of Composites Science, 10(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcs10010007