Abstract

A flexible piezoresistive material based on vulcanized natural rubber (VNR) and multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) was developed and systematically investigated for strain sensing applications. The nanocomposites were prepared by melting and vulcanizing MWCNT, while keeping the rubber composition constant to isolate the effect of the conductive nanofiller. By scanning electron microscopy, morphological analyses indicated that MWCNTs were dispersed throughout the rubber matrix, with localized agglomerations becoming more evident at higher loadings. In mechanical tests, MWCNT incorporation increases the tensile strength of VNR, increasing the stress at break from 8.84 MPa for neat VNR to approximately 10.5 MPa at low MWCNT loadings. According to the electrical characterization, VNR-MWCNT nanocomposite exhibits a strong insulator–conductor transition, with the electrical percolation threshold occurring between 2 and 4 phr. The dc electrical conductivity increased sharply from values on the order of 10−14 S·m−1 for neat VNR to approximately 10−3 S·m−1 for nanocomposites containing 7 phr of MWCNT. Impedance spectroscopy revealed frequency-independent conductivity plateaus above the percolation threshold, indicating continuous conductive pathways, while dielectric analysis revealed strong interfacial polarization effects at the MWCNT–VNR interfaces. The piezoresistive response of samples containing MWCNT exhibited a stable, reversible, and nearly linear response under cyclic tensile deformation (10% strain). VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites demonstrate mechanical compliance and tunable electrical sensitivity, making them promising candidates for flexible and low-cost piezoresistive sensors.

1. Introduction

The development of smart materials capable of interacting with external stimuli in a controlled and predictable manner has been stimulated by the need to develop functional, adaptable, and sustainable solutions in recent years. As a result of their light weight, versatility, and ease of processing, polymeric materials have gained prominence in this area, as well as their ability to form conductive composites when combined with conductive particles [1,2]. By combining different types and concentrations of conductive particles into these composites, they combine polymeric structural characteristics with adjustable electrical properties, thereby targeting a variety of technological applications, such as flexible sensors, actuators, electronic devices, responsive biomaterials, and real-time monitoring systems [3,4].

One of the most common polymers used as matrices for nanocomposite production is the natural rubber (NR), which is a highly relevant material, particularly because it is renewable and has unique mechanical and elastic properties. Due to its molecular structure, which contains long chains of cis-1,4-polyisoprene, it performs well in applications that are flexible, resilient, and abrasion resistant [5]. With an average molecular weight of around 200,000, NR is widely used in the automotive, aerospace, and medical industries, mainly in the production of tires, technical artifacts, and hospital devices [6,7].

Furthermore, NR can be vulcanized to meet specific requirements in addition to its natural properties. During the vulcanization process of NR, cross-links between polymer chains are formed, typically with the help of sulfur [8]. A combination of accelerators, plasticizers, antioxidants, and other auxiliary substances can also be used to control the processing time and improve the final performance of the material. The incorporation of functional particles and nanoparticles presents a more recent and promising approach for producing composites and nanocomposites with optimized properties for high-tech applications [9].

When conductive nanoparticles are dispersed properly in nanocomposites, significant improvements in thermal, mechanical, and electrical performance can be achieved, enabling their application in strategic areas such as biomedicine, water filtration, flexible electronics, energy storage, and sensors [4,10,11,12,13,14]. Moreover, sectors such as automotive, aerospace, and renewable energy are also taking advantage of these advanced materials [15,16].

Among the available functional fillers, carbon-based nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), nanographite, carbon black, graphene, etc., are widely considered to be excellent electrical fillers due to their high aspect ratio, large surface area, and good mechanical properties [17,18,19,20]. The incorporation of these materials into polymer matrixes can create percolation pathways that transform an electrical insulator into a functional semiconductor. According to previous research, the introduction of these carbon-based nanomaterials into different polymers results in a significant improvement in their electrical and mechanical properties [21,22,23,24].

According to Cheng et al. (2014) [25], introducing multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) into a poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) matrix led to significant increases in electrical conductivity and mechanical strength. A large part of this effect is due to the elongated and highly conductive structure of MWCNTs, which create conductive networks even at low concentrations [26].

Recently, several studies have explored the use of natural rubber as a polymeric matrix for MWCNTs, resulting in nanocomposites that combine flexibility, durability, and electrical conductivity [27,28,29,30]. In addition, studies by have contributed to our understanding of NR interactions with carbon-based nanomaterials, primarily for sensors, actuators, and responsive devices [27,28,29,30,31].

Due to their flexibility, tunable conductivity, and mechanical compliance, elastomer composites reinforced with carbon-based fillers such as carbon black, graphene, and carbon nanotubes have attracted increasing attention for piezoresistive strain-sensing applications. Particularly, MWCNT-filled elastomers have demonstrated high sensitivity and low percolation thresholds, enabling the detection of small deformations [32,33,34]. However, challenges related to hysteresis, signal stability, and long-term durability under cyclic loading remain active research areas [35]. Researchers have recently explored strategies to balance sensitivity and stability by optimizing filler content, dispersion, and processing conditions [36,37]. Despite these advances, a comprehensive understanding of how filler concentration influences electrical, dielectric, and piezoresistive behavior-particularly under cyclic deformation-remains lacking. In this context, the present work focuses on the electrical, dielectric, and piezoresistive characterization of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites in order to contribute to our understanding of their behavior under mechanical deformation.

In this study, we present the preparation and characterization of piezoresistive nanocomposites based on vulcanized natural rubber (VNR) reinforced with multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), which are intended to be used as flexible strain sensors. In order to produce the nanocomposites, a conventional sulfur vulcanization route was employed, where the rubber formulation and vulcanizing system were kept constant, while the MWCNT content was systematically varied from 1 to 7 percent. The use of this method enabled the direct assessment of the effect of the conductive nanofiller on the electrical, dielectric, and electromechanical properties of the material, minimizing the influence of secondary formulation variables that were often overlooked in previous studies.

The main novelty of this study is the direct evaluation of the piezoresistive behavior of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites under in situ mechanical loading, which goes beyond compositional effects. It is noteworthy that, in contrast to most reports in the literature, which rely primarily on ex situ electrical measurements or low-strain regimes, the present study investigates the real-time evolution of electrical resistance during cyclic tensile deformation. As a function of applied strain, the nanocomposites showed a stable, reversible, and nearly linear resistance response, indicating a robust coupling between mechanical deformation and the conductive MWCNT network.

As a result of these findings, it has been demonstrated that VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites are capable of operating reliably under conditions reflective of practical service conditions. Consequently, the materials presented herein can be used as flexible piezoresistive sensor materials in structures undergoing dynamic loads, vibration, or crack initiation, especially in civil construction and structural health monitoring applications that require durability, sensitivity, and real-time response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The natural rubber used in this study was Brazilian light crepe rubber (BLC), which has a Mooney viscosity of 98 (determined at 100 °C). The BLC was provided by DLP Industries and Commerce of Borrachas and Artefacts Ltda-ME, located in Poloni, São Paulo, Brazil.

A multiwalled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) with an external diameter between 10 and 30 nm, a length ranging from 5 to 30 um, and a purity greater than 93% was provided by the Center for Nanomaterials Technology (CTNano/UFMG). MWCNTs contain less than 2% of other forms of carbon and up to 5% catalytic residues. These residues are mainly composed of Al2O3, Co, and Fe.

The rubber vulcanization process was carried out using commercially available additives, such as zinc oxide (ZnO, 99.8% purity, from Neon company, Brazil), stearic acid (C18H36O2, 95%, from Êxodo Científica, Brazil), sulfur (S8, 99.5%, from Êxodo Científica, Brazil), and benzothiazole disulfide (MBTS, from Basile Química, Brazil) and tetramethylthiuram disulfide (TMTD, from Basile Química, Brazil), both of which have 99% purity.

This formulation was selected to ensure consistent processing conditions and chemical compatibility among all components.

2.2. Piezoresistive Nanocomposites Production

A vulcanized NR (VNR) sample was prepared for the purpose of comparing it with piezoresistive nanocomposites. In this sense, the production of pure VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite was done in accordance with ASTM D3182 [38], with the mixing process conducted in an open parallel roller mixer (OPRM) with a friction ratio of 1:1.25.

The neat NR was initially added to the OPRM in a proportion of 100 per hundred rubber (phr). The shear generated by the parallel rollers facilitated the dispersion of the additives into the NR matrix. The next step was to incorporate ZnO and stearic acid, which serve, respectively, as activating agents and adhesion promoters between the polymer phases.

In order to allow the internal stresses created during the processing to relax after the compound was homogeneously mixed, it was left at room temperature for 24 h. Afterwards, the mass was processed again in the OPRM, where sulfur was added as a crosslinking agent, as well as MBTS and TMTD accelerators, which improved vulcanization kinetics.

Using steel molds with dimensions of 150 mm × 150 mm × 2 mm, the final mixture was pressed in a Mastermac thermopress (model Vulcan 400/20−1, manufactured in Itapira, São Paulo, Brazil) under 210 kgf cm2 pressure at temperature of 150 °C for 5 min. The samples obtained were then packaged and stored in a controlled environment until they were characterized.

The preparation of VNR/MWCNT-based piezoresistive nanocomposites was carried out according to the same procedure as that used to prepare neat VNR, with the only difference being the content of MWCNT (Table 1). The nanotubes were added to the mixer along with ZnO and stearic acid, in proportions ranging from 1 to 7 phr in comparison to neat NR.

Table 1.

Material used to prepare the VNR-MWCNT nanocomposite with different amounts of MWCNT in phr.

Table 1.

Material used to prepare the VNR-MWCNT nanocomposite with different amounts of MWCNT in phr.

| Samples | VNR | VNR-MWCNT1 | VNR-MWCNT2 | VNR-MWCNT3 | VNR-MWCNT4 | VNR-MWCNT5 | VNR-MWCNT7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| ZnO | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Stearic acid | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Sulfur | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| MBTS | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| TMTD | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| MWCNT | 0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 7.0 |

After dispersing the MWCNT and homogenizing the mass, the compound was left to rest for 24 h before vulcanization with sulfur, MBTS, and TMTD was completed. All vulcanized samples were pressed under identical experimental conditions, allowing comparison of the formulations and evaluation of the effect of the MWCNT content on the electrical, dielectric and piezoresistive properties of the nanocomposites.

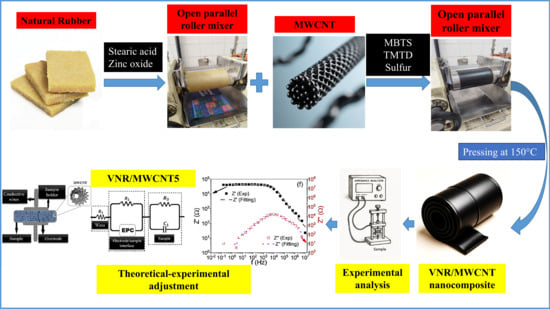

A sketch of the production and experimental analysis is shown in Figure 1, as well as a representation of the theoretical–experimental method used to evaluate the electrical characteristics of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples.

Figure 1.

A sketch of the production process and experimental analysis used to evaluate the electrical characteristics of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples.

2.3. Characterization

2.3.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis

Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the surface and internal structure of the VNR-based nanocomposite with MWCNTs were analyzed morphologically. In order to conduct the SEM analysis, the samples were cryo-fractured in liquid nitrogen and dried in a dynamic vacuum for approximately 10 min to eliminate moisture. Sputtering was used to metalize the ultrathin carbon layer (less than 10 nm thick). A scanning electron microscope (SEM) Zeiss EVO LS15 (manufactured in Oberkochen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany) was used to obtain micrographs.

2.3.2. Mechanical Tensile Analysis

Using a Biopdi universal testing machine (manufactured in São Carlos, São Paulo, Brazil), a 5 kN load cell and an internal strain transducer were used for stress-strain tests. In accordance with ASTM D412-16 [39], Type A specimens (dumbbell-shaped) were used for the tests.

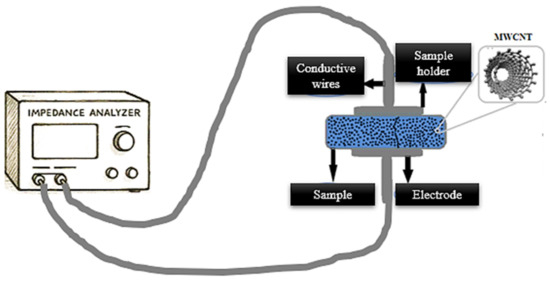

2.3.3. DC and AC Electrical Measurements

Electrical measurements were conducted on samples that had been plated with conductive paint on both sides, forming circular electrodes with a radius of 4.5 mm. The samples were mounted in an electrode-sample-electrode configuration, and the electrical measurements were carried out using the two-point method coupled to the electrical measuring equipment as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the sample port of the two-probe electrical analysis system used for both DC and AC regime analyses of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites.

The dc regime analysis was conducted with the aid of a high-voltage power supply (model 247) coupled to an electrometer (model 610C), both from Keithley Instruments. The potential difference of 10 V was applied to samples with MWCNT concentrations greater than 2 phr. In the case of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with lower MWCNT concentrations, a voltage of 50 V was applied to compensate for their lower electrical conductivity. Using the applied voltage and current measured in the experimental analysis, the DC electrical conductivity (σdc) of VNR-MWCNT nanocomposite samples with different MWCNT phr concentrations was calculated, as given in Equation (1):

where L represents the thickness of the sample and A represents the area metallized of the electrodes on both surfaces of the samples.

An electrical impedance analysis was conducted using a Solartron SI 1260 system (with 0.1% accuracy) from AMETEK, manufactured in Farnborough, UK, operating at 10−2 to 106 Hz, applying an AC voltage of 0.5 V at room temperature.

By analyzing the complex impedance (Z*(f)) and real (Z′(f)) and imaginary (Z″(f)) components as a function of frequency, it is possible to establish direct relationships between the electrical response and the material’s microstructure. In this sense, the vector Z*(f) in the complex plane can be viewed as a matrix of its components, where the x-axis represents the real quantities while the y-axis represents the imaginary quantities [40]. In this case, vector Z*(f) is given by Equation (2):

i is an imaginary number (i2 = −1). Consequently, the real part of the equation is Z′(f) and is related to purely resistive effects (energy dissipation), whereas the imaginary part of the equation is Z″(f) and is related to purely capacitive or inductive effects (energy storage) [40,41]. In this sense, a set of quantities can be derived from the complex impedance that allow obtaining important information about molecular movements and relaxation processes, which are other forms of response of the material studied when a potential difference is applied to it [40]. Thus, electrical and dielectric properties can be studied based on complex impedance functions.

Among these quantities, complex electrical conductivity (σ*(f)) is noteworthy, as it refers to a material’s ability to conduct an electric current under the influence of an AC electric field. For materials subjected to ac electric fields, the quantity σ*(f) is realized with the quantity Z*(f) by Equation (3):

A is the metallized area on both faces of the sample (electrode) and L is the sample’s thickness. It may be noted that the real (σ′(f)) and imaginary (σ″(f)) components of the complex conductivity are related to the real and imaginary components of the complex impedance Z* as shown in Equations (4) and (5):

and

Similarly, using Z*(f), it is possible to determine the dielectric permittivity in the complex plane, which is represented by Equation (6):

represents the ability of a material to be polarized and therefore corresponds to the capacity of a material to store energy as a result of an electric field, whereas

is the imaginary component that is related to the dielectric losses of the material, which is a measure of the material’s conductivity [40,41]. Equation (7) describes the capacitance in vacuum (C0) as follows:

ε0 represents the permittivity of vacuum (8.85 × 10−12 F/m). The real and imaginary magnitudes of ε* can be calculated using Equations (8) and (9):

and

2.3.4. Piezoresistive Characterization

Piezoresistive characterization of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite films with varying MWCNT concentrations was conducted under cyclic axial mechanical tension, simultaneously with direct current (DC). A Keithley model 237 current and voltage source was used, which provided an accuracy of 0.3%.

In accordance with ISO 37:2011 [42], mechanical tests were conducted on an Instron universal testing machine, model 3639, equipped with a 100 N load cell. The load was applied by axial displacement of the grips at a constant speed of 12.5 mm/min up to the predetermined load limit. The mechanical deformation (ε-deformation of 10%) can be determined based on the relative displacement of the grips, taking into account the useful length of the sample.

To measure the electrical response, copper electrodes (10 mm × 5 mm × 0.2 mm) were fixed to the upper and lower ends of the films, ensuring good electrical contact and alignment with the tensile axis. During the test, a 10 V constant voltage was applied, while the electric current flowed in real time throughout the mechanical deformation cycle.

In this study, VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite films containing 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 phr of MWCNT were selected because samples with lower contents had very high electrical resistances, preventing reproducible piezoresistive responses from being obtained. In order to ensure geometric uniformity and reproducibility of the experimental results, the samples were prepared and cut according to ISO 1286:2006 [43].

3. Results

3.1. Morphological Analysis

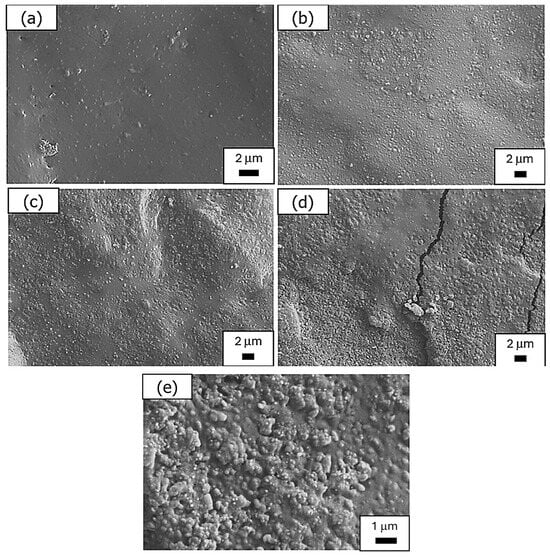

In the present study, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to evaluate how MWCNTs dispersed in the VNR matrix in a cryofractured cross-section of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite at various MWCNT concentrations. Figure 3a–d illustrate cross-sections of cryofractured surfaces of neat VNR samples and NR/MWCNT nanocomposites with MWCNT concentrations of 1, 5, and 7 phr.

Figure 3.

SEM analyses of the cryofracture cross-sectional surface of (a) pure VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites at MWCNT concentrations of (b) 1 phr, (c) 5 phr, and (d,e) 7 phr.

VNR samples have a smooth and homogeneous surface, demonstrating the effectiveness of the process of processing and vulcanization. Based on the findings of Santos et al. (2015), the few visible particles may indicate additives and accelerators that did not fully react with the matrix [44]. A homogeneous surface indicates that both the mixing process in parallel rolls and the vulcanizing process were carried out efficiently, resulting in a matrix free of visible imperfections [45].

In VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites, matrix roughness increases with increasing MWCNT content, both at the surface and in cryofractured cross-sections, especially in samples with 5 and 7 phr. According to the micrographs, localized MWCNT clusters can be seen, but the nanotubes dispersed homogeneously in general, indicating that the MWCNTs had been homogenized effectively. In Figure 3e, the SEM image at a higher magnification (20 KX) is shown to demonstrate the good dispersion and homogenization of the MWCNT in the matrix of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with 7 phr. Even when considering the natural tendency of MWCNTs to agglomerate due to Van der Waals forces, the mixing process in open parallel rolls proved to be effective [46].

An important indicator is the homogeneous dispersion of MWCNTs, since the efficiency of the distribution of nanoparticles directly influences the percolation threshold as well as the electrical and mechanical properties of nanocomposites. In conclusion, the results confirm that the experimental strategy used was effective in incorporating the nanotubes, resulting in materials with consistent, well-distributed internal structures that are able to withstand mechanical deformations while maintaining electrical conductivity.

3.2. Mechanical Analysis

The mechanical behavior of the neat VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites was evaluated based on the tensile parameters summarized in Table 2. VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples exhibit high deformability, as expected for elastomeric materials, although a clear dependence on the MWCNT content is observed with increasing filler concentration.

Table 2.

Mechanical parameters obtained from tensile mechanical test: tensile strength at 100% (σ100%) stress; stress at break (σat break); and the strain at break (εat break) of neat VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with different MWCNT fillers.

The incorporation of MWCNT into the VNR matrix leads to a systematic increase in the stress at 100% strain (σ100%), which rises from 0.72 MPa for neat VNR to a maximum of 1.47 MPa for the nanocomposite containing 5 phr of MWCNT. This trend reflects the progressive stiffening of the VNR matrix, associated with the restriction of polymer chain mobility induced by the rigid MWCNT network and the filler-matrix interactions [47]. Such behavior is commonly reported for rubber-based nanocomposites reinforced with high-aspect-ratio fillers and confirms the effective reinforcing role of MWCNT at low and intermediate loadings [45,48].

Regarding the stress at break (σat break), an increase is observed with increasing MWCNT content up to 3 phr, where the highest value among the nanocomposites is achieved. This improvement suggests that, at low filler concentrations, MWCNT are relatively well dispersed within the VNR matrix, enabling efficient stress transfer from the polymer chains to the MWCNT network [47]. Beyond this concentration, however, σat break value no longer follows an increasing trend and shows a reduction for higher MWCNT loadings, particularly for the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite containing 7 phr of MWCNT, which exhibits the lowest tensile strength among all samples. This pronounced decrease is likely associated with the formation of MWCNT agglomerates promoted by van der Waals interactions at higher filler contents, which act as stress concentration sites and compromise the mechanical integrity of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite.

The strain at break (εat break) decreases with increasing MWCNT concentration, from approximately 780% for neat VNR to 375% for the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with 7 phr of MWCNT. This reduction in extensibility indicates a progressive loss of elasticity as the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites become stiffer with increasing MWCNT content. The presence of MWCNT constrains the large-scale deformation of the NR chains, limiting their ability to undergo reversible stretching under tensile loading. The effect is particularly pronounced at high MWCNT loadings, where filler agglomeration further restricts chain mobility and accelerates premature failure [31,].

Overall, the mechanical tensile data reveal a clear trade-off between stiffness and deformability as a function of MWCNT concentration. While low to moderate filler contents (up to 3 phr) promote mechanical reinforcement without severely compromising tensile strength, excessive MWCNT loading leads to reduced tensile performance due to aggregation effects. Importantly, despite the observed decrease in εat break value, all nanocomposites maintain sufficient mechanical integrity within the strain range employed in the piezoresistive experiments, supporting their suitability for flexible strain-sensing applications.

3.3. DC Electrical Conductivity Analysis

Direct current (DC) electrical analysis has proven to be a fundamental tool for evaluating the potential application of polymeric materials and their compounds in electronic devices, sensors, actuators, and energy storage devices. Understanding how the internal structure of these materials affects their electrical properties enables, among other things, modifying formulations and adjusting processing parameters in order to achieve the desired performance in specific applications.

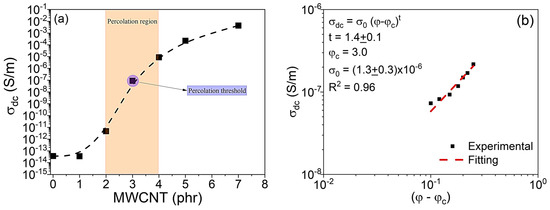

Polymers are inherently insulating materials due to their low density of free charge carriers and high electrical resistivity. Therefore, the incorporation of conductive fillers is necessary to enable charge transport and impart electrical functionality to polymer-based composites [41,49,50]. Figure 4a illustrates the typical behavior of the DC electrical conductivity (σdc) for conductive polymer nanocomposite materials that are described as disordered solids [51].

Figure 4.

(a) DC electrical conductivity as a function of MWCNT concentration (phr) in VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite and (b) double logarithmic plot based on Equation (2).

For concentrations below approximately 2 phr of MWCNT, σdc values remain very close to those of the neat VNR matrix, with orders of magnitude between 10−14 and 10−12 S/m. As a result, it appears that the MWCNTs are still distributed in an isolated manner, without sufficient contact between them to create conductive pathways [52]. Electrical conduction occurs in this region primarily because of the movement of spatial charges trapped in the VNR matrix [53].

An abrupt change in the electrical conductivity of VNR/MWCNT is observed above 2 phr of MWCNT, indicating that the percolation region lies between 2 and 4 phr. In this percolation region, a three-dimensional conductive network of interconnected MWCNTs is formed, allowing charge carriers to move along paths of lower potential or resistance barrier under the influence of an external electric field [41,52]. It can be observed that the σdc values increases from 10−14 S/m for samples with 1 phr of MWCNT to a value of 10−7 S/m for samples with 3 phr of MWCNT. Nevertheless, the highest σdc values were observed for samples with 5 phr (10−4 S/m), while the 7 phr sample (10−3 S/m) showed a tendency towards saturation, suggesting that the nanocomposite contains an uninterrupted conductive network of well-formed MWCNTs.

By applying the concept of percolation theory, it is possible to study and evaluate the behavior of σdc as a function of MWCNT mass concentration for VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites [54]. This theory can be used to interpret and evaluate the conduction process in composites made up of an insulating matrix and conductive phase as a second phase, with the aim of determining the nature of the insulator–conductor transition that occurs in composite materials of this type [54,55]. Using this percolation theory, the σdc value near the percolation threshold can be described by a power-type equation, as shown in Equation (10):

φ represents the volume fraction of the conducting phase and φC represents the critical volume of the conducting phase at which the transition from insulator to conductor occurs (also referred to as the percolation threshold), σ0 is the pre-exponential constant, and t is the critical exponent. In this case, the t exponents are determined by the geometry of the system and the dimensions of the conductive network [56,57]. A system such as the VNR/MWCNT conductive nanocomposite, for example, when the concentration of the conducting phase is below the percolation threshold (φ < φC), the σdc value is characteristic of the insulating VNR matrix. The reason for this behavior is that the MWCNTs in the polymer matrix are very far apart from each other, resulting in a lack of a continuous path along which the charge carriers could move in the presence of an electric field [41,54].

Conversely, when the volume fraction of the conducting phase equals the critical concentration or percolation threshold (φ = φC), the σdc value of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite increases dramatically; therefore, an insulator–conductor transition occurs in the nanocomposite [41,54,56]. When the concentration of the conducting phase reaches the percolation threshold value, the first uninterrupted path of MWCNTs is formed within the VNR matrix, as illustrated in Figure 4b. This leads to a sharp increase in the σdc value. Finally, when the volume fraction exceeds the percolation threshold (φ > φC), the σdc value approaches that of the conducting phase. This occurs due to the formation of a continuous network of conductive paths, in which charge carrier conduction occurs primarily by hopping mechanisms between states located in regions where the MWCNTs are in physical contact or close enough to each other, but still separated by small interatomic distances [41,54,56].

Accordingly, the logarithmic scale graph of the σdc behavior as a function of (φ–φC) can be obtained by taking φ values above the percolation threshold of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples as shown in Figure 4b. Using the data from Figure 4a, the theoretical–experimental adjustment was performed using Equation (10) and linear regression to calculate the linear (σ0) and angular (t exponent) coefficients. The theoretical–experimental adjustment was used to determine the σ0 and t values for the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples, which were approximately (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−6 and 1.4 ± 0.3, respectively.

In accordance with percolation theory, when the t exponent is between 1.0 and 1.5 for percolative systems, such as composites involving polymer matrices and conductive phases with perfectly spherical morphology, the conduction process occurs within a two-dimensional network resulting from physical contact between particles [57]. When the value of t is between 1.6 and 2.0, the conduction process takes place through a three-dimensional network in which the charge carriers move under the influence of the DC electric field [58]. Thus, based on the results obtained from the theoretical–experimental fit of the line in Figure 4b, it can be observed that the electrical conduction process of the charge carriers under the action of a DC electric field occurs in the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite through a two-dimensional conductive network of MWCNT in geometric contact dispersed in the matrix of VNR.

The transition from insulating to conductive behavior observed in the VNR/MWCNT system is consistent with the results reported by other authors. In a study by Rebeque et al. (2019) [41], carbon black (CB) and activated carbon (AC) nanoparticles were incorporated into a castor oil-based polyurethane (PUR) matrix resulting in a significant increase in electrical conductivity. Similarly, Deniz et al. (2019) [31] found that electrical percolation of nanocomposite films made from prevulcanized natural rubber latex with CB particles occurred with approximately 3 wt.% of the conductive phase present. With a dispersion of 4 wt.% CB, the σdc value increased from 10−12 S/m for neat NR matrix to 10−6 S/m for NR/CB nanocomposite (96/04).

The results presented here demonstrate that the addition of MWCNT to the VNR matrix is an effective method for modifying the electrical properties of this material. Identifying the percolation threshold at approximately 3.0 phr provides a valuable parameter for the development of conductive systems with adjustable performance, which could facilitate applications in piezoresistive sensors, flexible electronic components, and other emerging technologies using polymer nanocomposites [59].

3.4. Electrical Properties Analysis in the AC Regime

Even though it is crucial to study composite materials’ electrical properties under DC conditions, alternating electric fields (AC) are also important, since they provide a deeper understanding of electrical conduction when a material is subjected to a variable frequency AC electric field. In contrast to the DC regime, in which charge carriers follow relatively long interatomic paths in the direction of the electric field, in the AC regime they must continuously respond to rapid reversals of the alternating electric field. In heterogeneous and disordered systems, this dynamic interaction between matrices and conductive nanofillers allows the identification of electrical conduction and charge carrier relaxation within conductive nanocomposite materials [60]. Consequently, electrical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) provides a powerful analytical method for investigating the conduction and polarization mechanisms of different types of materials over a wide frequency range [61,62].

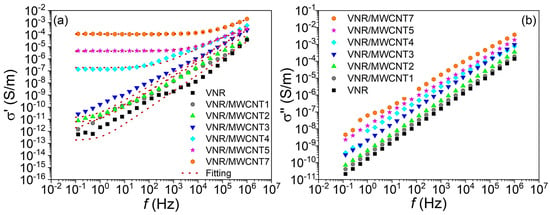

The behavior of σ′(f) and σ″(f) for VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites with different MWCNT concentrations is displayed in Figure 5a,b as a function of frequency. Figure 5a illustrates that the value of σ′(f) increases continuously with frequency for NR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with concentrations below the percolation threshold (0, 1, 2, and 3 phr of MWCNT). This behavior indicates that the charge carriers are strongly influenced by the potential barriers that arise along the path due to the presence of thin NR layers separating the MWCNTs, which act as potential barriers, as well as the interfacial effect resulting from the trapping of charge carriers between the NR-MWCNT interfaces, resulting in strongly frequency dependent electrical conduction [31,41]. According to similar studies in the literature, this behavior is typical of disordered solids [63,64].

Figure 5.

Analysis of (a) σ′(f) and (b) σ″(f) as a function of frequency for neat VNR and samples of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites with different MWCNT concentrations.

There are two distinct, well-defined regions on the σ′(f) curves of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with MWCNT concentrations exceeding the percolation thresholds (4, 5, and 7 phr): one region where σ′(f) values exhibit frequency-independent behavior (plateau) followed by a region where σ′(f) values exhibit frequency-dependent behavior (high-frequency region).

The frequency at which the transition occurs between frequency-independent and frequency-dependent behavior of the σ′(f) is called the critical frequency (fC) and indicates the presence of a well-formed percolation network capable of sustaining conduction approximately in the DC regime at low frequencies due to a low-resistance conduction path formed by MWCNTs [65]. In conductive composites containing a concentration of the conductive phase above the percolation threshold, this behavior is observed. As a result, charge carriers at lower frequencies have sufficient time to travel greater interatomic distances with a free path and lower electrical resistance [50].

Furthermore, their response to the reversal of the AC electric field is faster and more effective due to the low electrical resistance along the free conduction path. With increasing frequency, the charge carrier’s response time to the reversal of the electrical field is faster, resulting in the charge carrier moving in increasingly smaller regions, making hopping between localized states with lower potential barriers [53,66]. This reflects a typical behavior of disordered materials, as also described by [67,68], who explain that charge transport is influenced by both the morphology of the system and the connectivity between the conductive phases in a disordered system, as often seen in composite materials.

Furthermore, as the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite becomes more conductive, the fC value shifts to higher frequency values, demonstrating that the free path of charge carriers has a lower electrical resistance, which results in a faster response of charge carriers when the electric field is inverted as the concentration of MWCNTs increases. As well, it has been observed that the higher the concentration of MWCNTs, the higher the σ′(f) values in the low frequency regime, indicating that increasing the number of conductive phases facilitates the formation of an efficient conductive percolation network, increases the number of electric charge carriers participating in electrical conduction, and increases the amount of available conductive phases. Those results are consistent with the analysis of electrical conductivity in the DC regime (Figure 4a).

Similarly, Rebeque et al. (2019) reported similar results when studying castor oil-based polyurethane nanocomposites reinforced with carbon black and activated carbon. According to the authors, the value of σ′(f) increases with the frequency of the applied electric field in low-frequency regimes as the concentration of the conductor phase also increases [41]. Also, it was observed that the value of σ′(f) for compounds with conductor phase concentrations below the percolation limits shows frequency-dependent behavior [41].

Figure 5b illustrates the frequency-dependent behavior of the imaginary component of conductivity (σ″(f)) over the entire range studied and for all concentrations assessed. This behavior is characteristic of systems that exhibit capacitive effects and charge trapping phenomena [40]. Under the influence of an AC electric field, the quantity σ″(f) is associated with charges that cannot directly contribute to electrical conduction within the composite; in other words, these charge carriers fail to follow the AC field or become out of phase because they are trapped at the interfaces between the MWCNT matrix and the VNR matrix, resulting in capacitive behavior [69]. The reason for this behavior is that microcapacitors are formed within the composite, consisting of regions or clusters of MWCNT separated by thin layers of VNR dielectrics [31,70].

The other hypothesis is that these charge carriers are unable to follow the inversion of the electric field because of the energy loss caused by friction along the conduction path [41]. As the frequency increases, these charges lose the ability to keep up with the rapid reversals of the electric field, which results in a phase-shifted response, which is precisely what constitutes the imaginary contribution of conductivity. Figure 5b also illustrates that σ″(f) increases as the concentration of MWCNTs increases at low frequency, in a similar manner to how the amount of charge carriers available for electrical conduction increases with an increase in MWCNT concentration [41]. However, as the frequency of the electric field increases, there is also an increase in the number of charge carriers that cease participating in conduction.

It is possible to employ the theoretical model known as Jonscher’s universal power law to explain more fully the behavior of σ′(f) of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites. In the literature, this model has been widely used to explain the behavior of disordered solids and semiconductor materials, especially in polymer composites containing dispersed conductive phases [65,71]. In accordance with Jonscher’s law, the real component of the σ*(f) can be described by the following Equation (11):

In this equation, σdc represents the approximately continuous-state electrical conductivity (the behavior is not affected by frequency in low-frequency regimes); A is a pre-exponential factor related to the system’s polarization; and n is the dispersion exponent, a fractional value between 0 and 1, which tells you what charge transport mechanism the system has. The Jonscher’s universal power law does not limit the n value to less than 1, according to Papathanassiou et al., there is no physical reason to restrict n to less than 1 [72].

The exponent n provides important information regarding the type of electrical conduction prevalent in the material. Values less than 1 (Table 3) indicate hopping conduction between localized states for conductive samples of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites [65,71]. According to our results in these nanocomposite samples (4–7 phr of MWCNT) the evolution of a plateau at low frequencies indicates that conduction occurs usually through percolative paths, where σ′(f) is typically equal to DC regime in the low frequency regime. For certain electrical parameters, particularly near the percolation threshold, large error margins were observed due to local variations in MWCNT dispersion and stochastic pathway formation. It is possible that even small differences in MWCNT connectivity and contact resistance during measurement may result in increased data scattering in this regime, which is characteristic of conductive polymer composites near the percolation transition.

Table 3.

Parameter values of the Jonscher’s universal power law obtained through experimental fitting from Figure 5a.

Furthermore, the electrical conduction process occurs essentially through dispersive mechanisms in samples which contain less MWCNT content, as predicted by the Jonscher’s equation, σ(f) ≅ Aωn [73]. In contrast to the samples with MWCNT concentrations above the percolation threshold, VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with lower MWCNT concentrations display frequency-dependent behavior for the studied range, as illustrated in Figure 5a, indicating an insulating behavior. It can be seen in Table 3 that the n values for these samples exceeded 1, which may be related to the limited number of charge carriers available for conduction, as well as the AC-regime conduction process, which is influenced by the interfacial polarization process of space charges trapped at the interfaces of VNR-MWCNT [74].

Based on the combination of experimental σ′(f) data and analysis based on Jonscher’s Law, it was possible to gain a deeper understanding of the different transport mechanisms present in VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites. MWCNT concentration directly influences the transition between conduction regimes, highlighting the importance of forming an efficient conductive network for electronic devices and functional sensors [71].

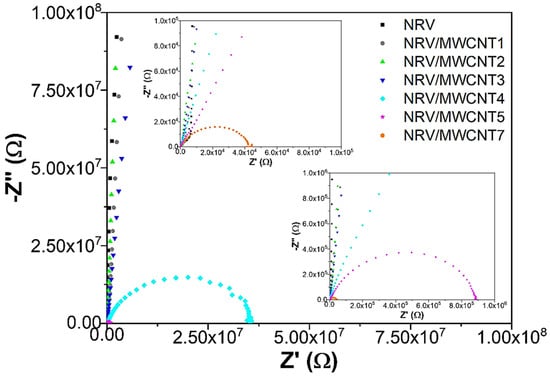

The Nyquist diagram can also be used to evaluate the AC electrical behavior of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples, which is represented by the impedance graph in the complex Z* plane, that is, the graph of Z″ versus Z′. Figure 6 illustrates the Nyquist diagram for the different MWCNT phr concentrations in VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples.

Figure 6.

Nyquist diagram of the pure VNR sample and the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with varying MWCNT concentrations.

It is evident from the Nyquist diagram that the more conductive the sample, the smaller the semicircle, a fact observed for all samples with concentrations above the MWCNT percolation threshold. As a consequence of the combination of resistive and capacitive elements in parallel circuits that represent the conductive phase (resistor) and matrix phase (capacitor), there is a bulk effect present in the nanocomposites [61,75]. Moharana et al. (2017) observed similar results when evaluating the dielectric and electrical properties of a PVDF/BaTiO3 composite modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG) [76]. The bulk effects arise as a result of the parallel combination of bulk resistance (Rb) and bulk capacitance (Cb), which represent the material’s structure [61,76].

As shown in Figure 6, when the semicircle touches the Z′ axis (x-axis), the overall resistance of the nanocomposite can be determined (being approximately 4.5 × 104 Ω for sample with 7 phr MWCNT, 9.8 × 105 Ω for the 5 phr MWCNT, and 2.7 × 107 Ω for the 4 phr MWCNT). In the case of VNR/MWCNT samples with MWCNT concentrations below the percolation threshold, it would only be possible to observe the semicircle at low frequencies, i.e., below 0.1 Hz.

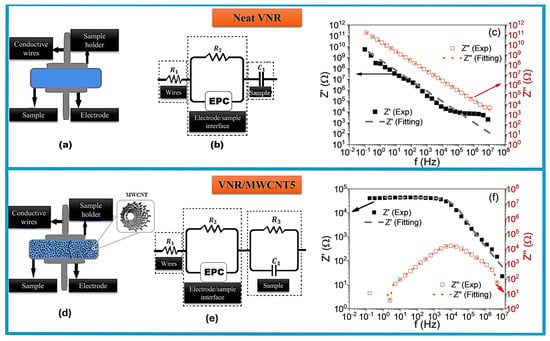

VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites can also be evaluated electrically through process modeling, in which the collected impedance data are fitted to a hypothetical electrical circuit model. In this sense, the theoretical–experimental adjustment can be constructed by using an equivalent electrical circuit consisting of capacitors, resistors, and constant-phase elements (CPEs) with the objective of simulating the electrical properties of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites and represents a specific physical process, as shown in Figure 7. The CPE is defined as an equivalent electrical circuit component used in EIS to model the behavior of real electrode interfaces which do not exhibit ideal capacitance characteristics and can be calculated by Equation (12):

Q and s characterize the pseudo-capacitance and phase dispersion, respectively (where s = 0 indicates an ideal resistor, and s = 1 indicates an ideal capacitor).

Figure 7.

Examples of the system assembled to perform EIE measurements, (a,d) sample holder of the two-probe electrical analysis system, (b,e) the equivalent circuit representing the electrical behavior, and simulation of the Z′ and Z″ curves as a function of frequency for the (c) VNR and (f) VNR/MWCNT samples containing 5 phr of MWCNT.

The theoretical–experimental adjustment was performed using the EIS Spectrum Analyzer software (version 1.97). An analysis was performed on the neat VNR sample and the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite containing 5 phr of MWCNT. For all other samples (VNR/MWCNT) with different phr concentrations of MWCNT, the equivalent circuit configuration resulting from the simulation of the 5 phr MWCNT sample was adopted. During the design process, the topology of the circuit was fixed, while the parameters of each element were individually adjusted based on the experimental results of each sample of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite.

For both neat VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites, Figure 7 shows the experimental scheme and equivalent circuits. The circuit selected to represent the samples consists of the following electrical elements: R1, which represents the wire/electrode contact resistance, whose value has been maintained for all samples (Table 4). R2 is the resistance associated with the electrode and electrode/sample interface; CPE (with the constant Q and the s exponent) is the element that models phase dispersions and non-idealities in the deposited conductive layer and is calculated from Equation (12); C1 is a measure of bulk capacitance in the VNR matrix. In parallel with capacitor C1, which represents the VNR matrix, R3 represents the bulk resistance associated with the conductive paths of the MWCNTs.

Table 4.

Parameter values adopted for the equivalent circuit elements of the samples in order to perform the theoretical–experimental adjustment in the EIS Spectrum Analyser program.

Due to its insulating electrical nature, the simulated circuit for neat VNR does not include resistor R3, as it is understood that only capacitive effects are present inside the sample due to its insulating nature. Therefore, theoretical–experimental adjustments were made to the Z′(f) and Z″(f) curves as a function of frequency (the adjustments are indicated by dashed lines). According to Figure 7, the adjustment occurs satisfactorily for both VNR and VNR/MWCNT samples with 5 phr of MWCNT, demonstrating that the proposed circuits with their different electrical elements represent each experimental component. In Table 4, the parameters used for theoretical–experimental adjustment are presented, and the same trend was observed for other samples as well.

According to Table 4, all samples of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with different concentrations of MWCNT have been adjusted for R1, R2, P1, s, Q, R3, and C1. As a result of the increase in MWCNT, these parameters can be interpreted physically as follows: R1 was maintained around 0.05 for all samples, indicating that the cable/electrode contributed negligible and uniform resistance throughout the measurements, indicating that the observed changes were primarily due to the samples’ intrinsic properties.

The electrode/sample interface resistance, R2, is very high in pure VNR (on the order of 1013 Ω) and significantly decreases when MWCNT concentrations are introduced. As a result of this initial decline in R2, it is likely that the presence of MWCNT facilitates conduction at the interface, potentially by improving the effective electrical contact between the conductive electrode (conductive ink) and the surface of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite.

A final parameter, R3, represents the resistance of the conductive path created by the dispersion of MWCNT within the VNR matrix; that is, it best illustrates the formation of a conductive percolation network within the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite. As the concentration of MWCNT increases, R3 decreases sharply, as shown in Table 4. In particular, a substantial reduction in R3 is observed for concentrations above the percolation threshold (4, 5, and 7 phr of MWCNT), indicating that the system approaches or exceeds this critical concentration, which is consistent with the analysis of the DC electrical conductivity which determined that the percolation threshold is 3 phr of MWCNT.

This is attributed to the fact that uninterrupted percolation path was formed within the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite. Meanwhile, VNR/MWCNTs nanocomposites with MWCNT concentrations below percolation thresholds exhibit high R3 values, resulting from the fact that MWCNTs are separated by long interatomic distances and high electrical potential barriers, which results in high resistance along the charge carrier path.

According to Table 4, the capacitance of the VNR matrix tends to increase as MWCNTs are added. As a result of the greater number of VNR–MWCNT interfaces and a greater accumulation of charge carriers in these regions, an increase in C1 is consistent with an increase in interfacial polarization (Maxwell–Wagner–Sillars effect) [77]. In VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites, these interface regions formed by MWCNT-VNR-MWCNT act as microcapacitors that accumulate electrical charges when exposed to an electric field [56]. Thus, as the concentration of MWCNT increases in the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite, the greater the amount of microcapacitors formation and the greater the amount of charge carriers trapped at these interfaces, increasing the material’s capacitance [31,56,70].

Finally, Table 4 shows values for s exponent as well as for Q, an element of the CPE. Based on all adjustments, s values were close to 0.8–1.0, indicating a predominantly non-ideal capacitive character at the electrode-sample interface. The fact that s value is lower than 1, especially in intermediate samples, indicates dispersive processes (such as hopping conduction between localized states) and heterogeneities in the MWCNT distribution [78]. VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with concentrations above the percolation threshold tend to exhibit a more consistent s value, suggesting a less dispersive electrical response, which is more governed by percolative paths [79].

It is evident, however, that the data indicate a coherent evolution: for low MWCNT concentrations (1–3 phr), the nanocomposite exhibits strong frequency dependence and high path resistance. At higher concentrations, however, the resistance drops sharply along with more defined semicircular structures in the Z″(f) versus Z′(f), as well as conductive-capacitive behavior characteristic of percolated systems. Therefore, maintaining the same circuit for all samples (with parameter adjustments) is justified and useful for comparing quantitatively the impact of the conductive load on each element of the electrical equivalent.

As a result, the application of a single circuit model initially calibrated for 5 phr and adapted for the other concentrations using Table 4 provides a consistent and interpretable description of the effect of MWCNTs on VNR. In response to increasing MWCNT concentration, the value of R3 decreased and the value of C1 increased at the same time, suggesting that the evolution of electrical conduction is guided by two correlated phenomena: (i) the gradual formation of a conductive network reducing internal resistances; (ii) the increase in interfacial polarization as a result of the formation of microcapacitors at the MWCNT-VNR-MWCNT interface, which accumulate large amounts of electrical charge.

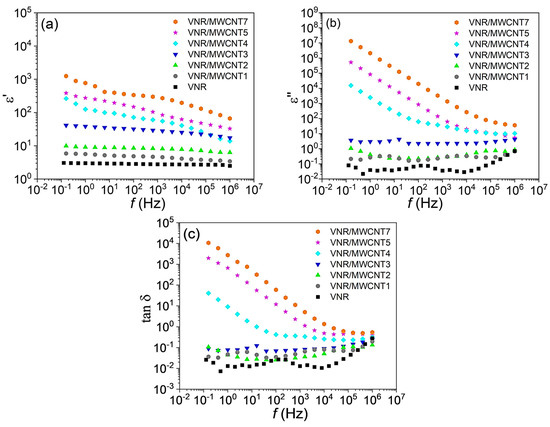

Another quantity obtained from complex impedance that provides relevant information about the dielectric properties of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite is the dielectric permittivity in the complex plane (ε*) and its real and imaginary components. It can be defined as the ability of a material to be polarized under the influence of an external electric field [80].

In the presence of an external electric field, molecules or electric charges within a material tend to form induced electric dipoles or regions that accumulate more charges than other regions. By creating small internal electric fields that oppose the external electric field, the material is able to accumulate more energy due to the electric field [80]. The same occurs when an AC electric field is applied to the material, which enables the evaluation and study of the various polarization processes (space charge polarization, dipolar, ionic and electronic) and electrical relaxation that may occur, as well as the dielectric losses that occur when a dipole or a charged entity moves during a change in direction of an AC electric field.

In Figure 8a, the behavior of

varies with frequency for the pure VNR sample and the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with different MWCNT phr concentrations (from 1 to 7 phr). As shown in Figure 8a, the value of

decreases with increasing frequency for all samples. The reason for this is that the samples are more conductive as the frequency of the AC electric field increases. As frequency increases, the dwell time of charged entities (dipoles and space charges trapped at interfaces) decreases.

Figure 8.

(a) Real and (b) imaginary dielectric permittivity curves and (c) tan δ (ε″/ε′) curve as a function of frequency for pure VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites at varying MWCNT concentrations.

The magnitude of

is proportional to the imaginary part of Z″, which is a function of the capacitive effects of the samples under the influence of the AC electric field. This behavior also corroborates the behavior of σ″(f) as a function of frequency (Figure 5b) of all samples studied, which indicates that charges carriers cannot follow the AC electric field because they are trapped at the VNR-MWCNT interfaces, which prevents them from participating in the conduction process.

Another important aspect is the increase in the

value as the concentration of MWCNT increases, primarily in the regime of low frequencies. As the concentration of MWCNT in the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite increases, the concentration of charge carriers trapped at the interfaces increases, resulting in an increase in the overall polarization of the material [41].

In Figure 8b, the behavior of

is shown as a function of frequency for all samples of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite. For all frequency regimes studied,

exhibits frequency-dependent behavior of the AC electric field. The quantity

represents the dielectric loss of the system; in this instance, the increase is due to the increasing concentration of MWCNT in the VNR/MWCNT samples.

The complex permittivity measurements are significantly influenced by the concentration of the conductive phase in the epoxy matrix, as demonstrated by reference [81]. Furthermore, Yang et al. (2014) [82] stated that the addition of conductive phases to polymeric matrices can result in several effects, such as: (i) an increase in the number of charges at interfaces as the conductive material is added; (ii) facilitating the mobility of polymer segments due to the presence of conductive molecules.

At low frequencies, the dielectric response of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites is dominated by interfacial polarization mechanisms, as described by the Maxwell-Wagner-Sillars model [83]. An explanation for this effect can be found in the strong contrast between the insulating VNR matrix and the conductive MWCNT network in terms of electrical conductivity and dielectric permittivity [84]. When an AC electric field is applied, charge carriers accumulate at the interfaces between these phases, leading to an increase in polarization. Therefore, for nanocomposites with higher MWCNT loadings, higher ε″ and ε′ values are observed in the low-frequency regime. The behavior of heterogeneous conductive polymer composites is explained by the increased interfacial area and the enhanced charge trapping at polymer–filler interfaces [84,85].

As the MWCNT content approaches and exceeds the electrical percolation threshold, the dielectric response increasingly reflects electrical charge transport and conduction-related phenomena [84,85]. It is believed that the formation of interconnected conductive pathways facilitates electron hopping and tunneling between adjacent MWCNTs, which contributes significantly to the ε″ value in the low frequency regime [83]. At low and intermediate frequencies, where charge carriers have sufficient time to respond to the applied AC field, the enhanced conduction contribution is particularly evident [50]. Essentially, the results indicate that near the percolation threshold, the dielectric behavior is governed by a combination of interfacial polarization and charge transport processes within the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite [41,86].

There is a significant reduction in both ε″ and ε′ values for all VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples at higher frequencies. During this frequency range, the AC electric field changes too rapidly for charge carriers to accumulate at interfaces or for dipolar entities within the VNR matrix to fully orient themselves [41]. Thus, interfacial polarization and dipolar relaxation are gradually suppressed. As a consequence, the dielectric response in this regime is dominated by intrinsic polarization mechanisms with limited charge displacement, leading to lower permittivity values and reduced dielectric losses [87]. As a result, this behavior is typical of polymer-based nanocomposites and highlights the frequency-dependent nature of the polarization processes which govern the electrical performance of VNR/MWCNT systems.

In Figure 8c, the dielectric loss tangent, (tan δ), for neat VNR and VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites with different MWCNT loadings is presented as a function of frequency. In order to evaluate dielectric losses, the tan δ is widely used, since it directly reflects the ratio between dissipative and energy-storing (/) processes within the material [40].

With increasing MWCNT concentration, tan δ value increases significantly at low frequencies, particularly in VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites with 5 and 7 phr of MWCNT. This pronounced loss behavior indicates that energy dissipation mechanisms dominate in this frequency range, attributed primarily to charge transport and interfacial polarization [88]. In VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples with higher MWCNT contents, where conductive pathways are more developed, the accumulation of charge carriers at the interface between the insulating VNR matrix and the MWCNT network results in significant dielectric losses. VNR/MWCNT7 sample exhibited extremely high tan δ values, which suggest excessive conduction losses, likely caused by filler agglomeration and uncontrolled conductive domains [89].

The tan δ values for all VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples decreases as the frequency increases. It is believed that this behavior results from the reduced ability of charge carriers and interfacial dipoles to follow the rapidly alternating electric field. In this intermediate frequency range, dielectric losses become increasingly less pronounced, indicating a transition from conduction and interfacial polarization-dominated behavior to intrinsic polarization [90]. The tan δ values of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites with intermediate MWCNT loadings (1–3 phr) are comparatively lower across a broad frequency range, suggesting a more balanced dielectric response with reduced energy dissipation.

Regardless of MWCNT concentration, tan δ values tend to converge toward relatively low and similar levels at high frequencies. During this regime, both interfacial polarization and long-range charge transport are suppressed, and dielectric losses are minimized.

The tan δ analysis provides additional insight into the dielectric performance of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites. In addition to enhancing electrical conductivity, higher MWCNT contents also result in increased dielectric losses at low frequencies. Conversely, nanocomposites with moderate MWCNT concentrations exhibit a better balance between electrical sensitivity and energy dissipation. The tan δ is a useful and intuitive metric for assessing dielectric losses. These results demonstrate the suitability of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites for applications in flexible and piezoresistive sensing, which require controlled dielectric behavior.

3.5. Piezoresistance Analysis

Piezoresistivity refers to a material’s ability to change its electrical resistance when subjected to a mechanical stimulus. This response is directly related to the interaction between the polymer matrix, which stretches, relaxes, and exhibits viscoelastic behavior, and the conductive network formed by the particles, such as MWCNTs. In the case of conductive polymer nanocomposites, when the material undergoes mechanical deformation, the separation between the MWCNTs interrupts the percolative conductive network, resulting in an increase in electrical resistance. As soon as mechanical stress is removed, the matrix tends to regain its original conformation, resulting in the nanoparticles becoming closer together and the percolative paths being reestablished, resulting in reduced resistance [31,]. In spite of the apparent simplicity of this process, it involves delays and internal reorganizations characteristic of elastomeric materials, which can explain the phase-shifted electrical response observed in some cycles.

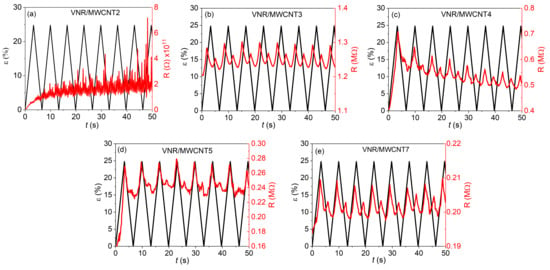

To verify the stability and repeatability of the piezoresistive response, VNR/MWCNT samples containing 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7 phr were evaluated in situ, as illustrated in Figure 9. The sample with 2 phr exhibited essentially insulating behavior without coherently following the mechanical deformation cycles (Figure 9a). According to the results, the amount of MWCNT was not sufficient to form a continuous conductive network, a typical characteristic of composites below the percolation threshold (Figure 4). Therefore, a more detailed discussion focused on formulations considered conductive, that is, those with 3, 4, 5, and 7 phr.

Figure 9.

Piezoresistive response of VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite with (a) 2 phr (VNR/MWCNT2), (b) 3 phr (VNR/MWCNT3), (c) 4 phr (VNR/MWCNT4), (d) 5 phr (VNR/MWCNT5) and (e) 7 phr (VNR/MWCNT7) for 10% of strain and 16 cycles. Black line represents 10% strain (ε) and 16 cycles, and red line represents electrical resistance (R) measured during the stress cycle.

At 3 phr and beyond, there is a clear transition to a conductive regime (Figure 9b). In the course of deformation, the electrical resistance begins to vary synchronously with the deformation, although there are still minor instabilities resulting from the formation of the conductive network [91]. Currently, some regions of the material exhibit well-defined percolation pathways, while others still depend on the mobility of polymer chains to facilitate contact between nanotubes.

In the presence of 4 and 5 phr of MWCNT (Figure 9c,d), this network strengthens, and the piezoresistive behavior is more linear and reproducible. As a result, the electrical response more closely follows the loading and unloading cycles, and the resistance returns to the initial value more predictably after the deformation is removed. It is, however, possible to observe a slight delay between the mechanical relief and the complete electrical recovery, an effect directly related to the viscoelasticity of the matrix [31]. In elastomeric nanocomposites, this type of behavior has already been extensively documented and confirms that the polymer matrix influences both rupture and reconstruction [31].

In Figure 9e, the sample containing 7 phr of MWCNT has the strongest response. MWCNT networks become dense enough to reduce the initial electrical resistance and increase the material’s sensitivity to deformation [47]. In cycle repetition, the electrical signal exhibits lower noise, greater stability, and better fidelity. In addition, the presence of MWCNT network for electrical conduction allows the nanocomposite to withstand successive deformations without significant loss of performance. These characteristics confirm that samples in this concentration range are suitable for applications such as flexible strain sensors, wearable devices, and electromechanical components requiring repeatability and stability [91,92,93].

In general, the results show a clear progression: below percolation, the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite samples remains insulating; near the threshold, an initial piezoresistive response emerges; above percolation, the conductive network stabilizes and the material begins to respond reliably to deformation; and at higher concentrations, such as 7 phr, the nanocomposite exhibits a more sensitive and stable behavior, which makes it suitable for developing resistive-based sensors. As a result of this evolution, the importance of connectivity between MWCNTs and the VNR matrix itself has been confirmed as a critical factor in piezoresistive performance.

As can be seen in the graphs of Figure 9, the results of the cyclic piezoresistivity tests show a trend in the behavior of electrical resistance as a function of the increase in load concentration and the amount of deformation applied to the sample, confirming that MWCNTs reduce the composite’s electrical resistance when added. In addition to these characteristics, this VNR/MWCNT nanocomposite can also be used as a piezoresistive sensor that can be subjected to a regime of mechanical variations, as mentioned by refs [31,,92,94]. Although extended fatigue tests and higher strain amplitudes may further elucidate long-term durability, the cyclic measurements performed in this study demonstrate a stable and repeatable piezoresistive response within the investigated strain range, which is significant for many practical flexible sensing applications.

Based on the cyclic piezoresistive measurements, the resistance response is stable and repeatable with minimal hysteresis within the investigated strain range (up to 10%). According to this behavior, the conductive MWCNT network undergoes reversible structural rearrangements during loading and unloading without being permanently damaged. Generally, the absence of pronounced signal drift over repeated cycles indicates good electromechanical stability, which is essential for reliable strain-sensing applications. In addition, higher strain amplitudes may result in increased hysteresis and fatigue-related effects due to irreversible network disruption and viscoelastic relaxation of the rubber matrix. Although such conditions were not explored in the present study, the observed stability at moderate strains supports the suitability of the VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites for flexible sensing applications operating under controlled deformation regimes, in accordance with literature research [31,,91,95,96].

4. Conclusions

This work investigated the influence of MWCNT dispersion on the electrical, dielectric, and piezoresistive behavior of vulcanized natural rubber (VNR) nanocomposites targeting sensing applications. SEM analyses confirmed that the adopted processing route enabled an efficient dispersion of MWCNTs within the elastomeric matrix, favoring the formation of conductive networks at relatively low filler contents.

Tensile analysis confirms that MWCNT acts as effective reinforcement agents at low MWCNT loadings, increasing stress at break from 8.84 MPa (neat VNR) to 10.45 MPa at 2 phr MWCNT. Due to aggregation effects, excessive filler content results in a pronounced reduction in tensile strength. However, all nanocomposites are sufficiently mechanically stable for flexible strain-sensing applications.

DC electrical measurements revealed a well-defined electrical percolation threshold at approximately 3 phr of MWCNT, marking a sharp insulator-to-conductor transition. Above this threshold, the electrical resistivity decreased drastically, with σdc values increasing by several orders of magnitude compared to neat VNR, indicating the establishment of stable conductive pathways. Impedance spectroscopy showed typical features of disordered conductive systems, with frequency-independent σ′(f) at low frequencies for percolated samples and a transition to frequency-dependent behavior at higher frequencies. Equivalent circuit analysis consistently described the nanocomposites as a parallel combination of bulk resistance (MWCNT) and a bulk capacitance (VNR matrix), highlighting the coupled roles of charge transport and interfacial polarization.

Dielectric results demonstrated an increase in ε′ value with increasing MWCNT content, particularly at low frequencies, due to enhanced interfacial polarization effects, while the decrease in ε′ value with frequency reflected the growing contribution of conductive mechanisms.

Piezoresistive tests showed that nanocomposites with MWCNT contents at and above the percolation threshold exhibit a stable, reversible, and reproducible resistance response under cyclic mechanical deformation, directly associated with reversible rearrangements of the conductive network during strain.

Overall, the results demonstrate that VNR/MWCNT nanocomposites offer a tunable electrical resistivity and reliable piezoresistive response while preserving the inherent flexibility of natural rubber. These features make the material a promising candidate for flexible strain sensors, particularly in structural health monitoring and wearable electronics, where mechanical compliance, durability, and stable electromechanical performance are essential.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.M., N.C.G., J.S.M., C.T.H., J.A.M., R.J.d.S., A.O.S., V.D.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; methodology, D.S.M., N.C.G., C.T.H. and M.J.S.; validation, D.S.M., C.T.H., J.A.M., R.J.d.S. and M.J.S.; formal analysis, D.S.M., N.C.G., A.O.S. and M.J.S.; investigation, D.S.M., N.C.G., J.S.M., C.T.H., V.D.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; resources, M.J.S.; data curation, D.S.M., C.T.H., J.A.M., A.O.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.M., N.C.G., J.S.M., C.T.H., J.A.M., R.J.d.S., A.O.S., V.D.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; writing—review and editing, C.T.H., J.A.M., R.J.d.S., A.O.S., V.D.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; visualization, D.S.M., N.C.G., J.S.M., C.T.H., J.A.M., R.J.d.S., A.O.S., V.D.S., L.F.P. and M.J.S.; supervision, M.J.S.; project administration, M.J.S.; funding acquisition, M.J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Sao Paulo State Funding Agency (FAPESP), grant number grant 2024/09307-6.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa (PROPE-UNESP), for the financial support provided. The authors are grateful to FAPESP (processes 2024/09307-6).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Khan, M.; Refati, M.F.A.D.; Arup, M.M.R.; Islam, M.A.; Mobarak, M.H. Conductive Polymer-Based Electronics in Additive Manufacturing: Materials, Processing, and Applications. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2025, 2025, 4234491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabali, A.A.A.; Alkaraki, A.; Gammoh, O.; Qnais, E.; Alqudah, A.; Mishra, V.; Mishra, Y.; El-Tanani, M. Design, Structure, and Application of Conductive Polymer Hybrid Materials: A Comprehensive Review of Classification, Fabrication, and Multifunctionality. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 27493–27523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamjid, E.; Najafi, P.; Khalili, M.A.; Shokouhnejad, N.; Karimi, M.; Sepahdoost, N. Review of Sustainable, Eco-Friendly, and Conductive Polymer Nanocomposites for Electronic and Thermal Applications: Current Status and Future Prospects. Discov. Nano 2024, 19, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, M.T.; Hossain, I.; Sheikh, M.S.; Rahman, M.S.; Uddin, N.; Donne, S.W.; Hoque, M.I.U. Advances in Conductive Polymer-Based Flexible Electronics for Multifunctional Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S.; Jacob, M.; Thomas, S. Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites; Mohanty, A.K., Misra, M., Drzal, L.T., Eds.; Imprensa CRC: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 9780429211607. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, C.F.; Galembeck, F.; Zarbin, A.J.G. Multifunctional Nanocomposites of Natural Rubber Latex and Carbon Nanostructures. Rev. Virtual De Quim. 2017, 9, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.J.; Dias, Y.J.; Yarin, A.L. Electrically-Assisted Supersonic Solution Blowing and Solution Blow Spinning of Fibrous Materials from Natural Rubber Extracted from Havea Brasilienses. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 192, 116101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.R.; Siddique, N.; Thompson, G.; Wang, X.; Coates, P.; Whiteside, B.; Benkreira, H.; Caton-Rose, F.; Lu, C.; Wang, Q.; et al. The Influence of Devulcanization and Revulcanization on Sulfur Cross-Link Type/Rank: Recycling of Ground Tire Rubber. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 41797–41806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, S. High-Performance Advanced Composites in Multifunctional Material Design: State of the Art, Challenges, and Future Directions. Materials 2024, 17, 5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojnourd, F.M.; Pakizeh, M. Preparation and Characterization of a Nanoclay/PVA/PSf Nanocomposite Membrane for Removal of Pharmaceuticals from Water. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 162, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshkar, F.; Omid, M.S. A Reliable Hydrophobic/Superoleophilic Fabric Filter for Oil—Water Separation: Hierarchical Bismuth/Purified Terephthalic Acid Nanocomposite. Cellulose 2020, 27, 9559–9575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Marwat, M.A.; Xie, B.; Ashtar, M.; Liu, K.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Fan, P.; Samart, C.; Ye, Z. Polymer Matrix Nanocomposites with 1D Ceramic Nano Fi Llers for Energy Storage Capacitor Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajik, S.; Beitollahi, H.; Nejad, F.G.; Dourandish, Z.; Khalilzadeh, M.A.; Jang, H.W.; Venditti, R.A.; Varma, R.S.; Shokouhimehr, M. Recent Developments in Polymer Nanocomposite-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Detecting Environmental Pollutants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 1112–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, R.; Li, R.; Liu, H.; Fan, Z.; Yang, Y.; Lin, Z. Effect of the Processing on the Resistance–Strain Response of Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube/Natural Rubber Composites for Use in Large Deformation Sensors. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadi, S.; Nazari, B. Recent Developments and Applications of Nanocomposites in Solar Cells: A Review. J. Compos. Compd. 2019, 1, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jian, R.; Chen, H.; Tian, X.; Sun, C.; Zhu, J.; Yang, Z.; Sun, J.; Wang, C. Application of Biodegradable and Biocompatible Nanocomposites in Electronics: Current Status and Future Directions. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinodhini, S.P.; Xavier, J.R. Recent Progress in Graphene-Based Nanocomposites for Enhanced Energy Storage and Corrosion Protection. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 14837–14879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, S.; Behera, S.; Moharana, S. Compositional Effect of Nanographite on the Dielectric and Electrical Properties of Three-Phase Polymer-Ceramic Composites. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2025, 64, 2827–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, F.; Jamshidi, M.; Ghamarpoor, R. Preparation of a Rubber Nanocomposite for Oil/Water Separation Using Surface Functionalized/Silanized Carbon Black Nanoparticles. Water Resour. Ind. 2024, 32, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nica, S.L.; Rata, D.M. Carbon Nanotube-Based Nanocomposites: Promising Materials for Advanced Biomedical Applications. In Carbon Nanotubes for a Green Environment; Kulkarni, S., Stoica, L., Haghi, A.K., Eds.; Apple Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 273–290. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Liu, P.; Du, J.; Zhao, L.; Ajayan, P.M.; Cheng, H.M. Increasing the Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Composites by Using Weak Nanotube-Polymer Interactions. Carbon 2010, 48, 3551–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghgoo, M.; Ansari, R.; Hassanzadeh-Aghdam, M.K. Prediction of Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Fiber-Carbon Nanotube-Reinforced Polymer Hybrid Composites. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 167, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xu, H.; Dai, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chi, Q. Carbon Nanotubes and Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets Co-filled Ethylene Propylene Diene Monomer Composites: Improved Electrical Property for Cable Accessory Applications. High Volt. 2023, 9, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]