Abstract

Silicon carbide (SiC) ceramics are regarded as high-performance structural materials due to their excellent high-temperature strength, wear resistance, and thermal stability. However, their inherent high brittleness, low fracture toughness, and difficulty in densification have limited their wider application. To overcome these challenges, introducing a second phase and/or sintering aids is necessary. In this paper, SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics were fabricated via spark plasma sintering at 1800 °C to 2100 °C. The interface, mechanical, and thermal properties were examined. It was found that the VC particles effectively pin the grain boundaries and suppress the abnormal growth of SiC grains. At temperatures exceeding 1800 °C, the N atoms released from the decomposition of AlN diffuse into the VC lattice, forming a V(C,N) solid solution that enhances both the toughness and strength of the ceramics. With increasing sintering temperature, the mechanical properties of the SiC multiphase ceramics first improve and then deteriorate. Ultimately, a nearly fully dense SiC multiphase ceramic is obtained. The maximum hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness of SAV20 are 28.7 GPa, 508 MPa, and 5.25 MPa·m1/2, respectively. Furthermore, the room-temperature friction coefficient and wear rate are 0.41 and 3.41 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m), respectively, and the thermal conductivity is 58 W/(m·K).

1. Introduction

Silicon carbide (SiC) ceramics show broad application potential in extreme environments, such as aerospace, energy equipment, luminescent materials, radiation-resistant nuclear ceramics, and sensors etc., due to their chemical stability, high hardness, and outstanding high-temperature mechanical properties [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Aluminum nitride (AlN) features high thermal conductivity and excellent insulation, making it the preferred material for electronic packaging [7,8,9,10,11]. SiC-AlN multiphase ceramics combine the high strength and high toughness of SiC with the high thermal conductivity of AlN, and are key materials for electronic packaging, microwave devices, and high-temperature structural components [12,13,14,15]. However, the strong covalent bonding in SiC makes sintering challenging. Typically, densification requires high temperatures (>2100 °C) and high pressures [16] Additionally, pure SiC ceramics exhibit relatively low toughness, which limits their use in scenarios involving complex stresses [17].

To overcome these challenges, researchers have developed composite ceramic systems by introducing secondary phases (such as AlN [18,19] and transition metal carbides [20]) or by adding sintering aids (such as Y2O3 and Al2O3 [21]), with the aim of achieving low-temperature densification and improved overall properties. Transition metal carbides, in particular, offer numerous advantages, including good corrosion resistance, high melting points, high hardness, excellent thermal stability, and superior mechanical performance [22]. Previous studies have shown the beneficial effects of different transition metal carbides in SiC-based composite ceramics. For example, the SiC–TaC composites prepared via spark plasma sintering (SPS) were found to possess optimal hardness (23.3 GPa) and fracture toughness (3.85 MPa·m1/2) [23]. SiC ceramics with TaC have been reported to show bending strength and fracture toughness of 708.8 MPa and8.3 MPa·m1/2, respectively [24]. SiC–39 vol.% WC composites containing 12 wt.% Al2O3/Y2O3 exhibited a hardness of 19 GPa and fracture toughness of 5.53 MPa·m1/2 [25]. Khodaei et al. fabricated SiC – (0–10 wt.%)TiC + 4.3 wt.% Al2O3/5.7 wt.% Y2O3 composite ceramics via pressureless sintering (PS) and found that with 5 wt.% TiC addition, the density, hardness, and fracture toughness of the composites increased to 97.40%, 26.73 GPa, and 5.80 MPa·m1/2, respectively [26].

Among the various investigated carbides, VC has attracted considerable attention due to its high hardness and its role both as a highly efficient sintering aid and a reinforcing phase. Studies have confirmed that the incorporation of VC promotes the densification of ZrB2–SiC composite ceramics under low-temperature temperatures. Guo et al. reported that in ZrB2–SiC composite ceramics via hot pressing (HP), the flexural strength initially decreased and then increased with rising VC content, reaching 620–770 MPa at a VC content of 10 wt.% [27]. Zou et al. demonstrated that ZrB2–SiC–VC powders subjected to high-energy ball milling for 1 h achieved relative densities exceeding 99% when sintered at 1900 °C under an argon pressure of 30 MPa. Furthermore, VC was found to outperform WC in removing oxide impurities from the ZrB2 surface, playing a crucial role in the densification process [28]. Despite these findings, the mechanism through which VC influences the microstructure and properties of SiC-based composite ceramics remains unclear.

In summary, although SiC and AlN possess good strength and excellent thermal conductivity, it is difficult to achieve densification. In this paper, VC was introduced to promote the sintering densification of SiC–AlN, thereby obtaining multiphase ceramics with good mechanical and thermal properties. The results are of guiding significance for the application of SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics in aerospace, energy and power, and other fields.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Sample Preparation

The raw materials used consisted of commercially available powders: α-SiC (average particle size of 0.6 μm, purity of 99.9%), AlN (average particle size of 0.6 μm, purity of 99.9%), VC (average particle size of 0.45 μm, purity of 99.9%), and Y2O3 (average particle size of 0.6 μm, purity of 99.9%). The raw materials were weighed according to a volume ratio of 8:1:1 (SiC:AlN:VC). Additionally, 1 wt.% Y2O3 (relative to the total mass) was added as a sintering aid. The powders were mixed in a planetary ball mill at 400 rpm for 8 h in alcohol with agate balls, with a ball-to-powder ratio of 10:1. The resulting slurry was dried, and the powder mixture was sieved through a 120-mesh screen.

The dried powders were then placed in a 25-mm-diameter cylindrical graphite mold coated with graphite felt and sintered using an SPS machine (SPS-4, Shanghai Chenhua Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) under a vacuum of 10 Pa. The sintering process was performed initially at a heating rate of 80 °C/min up to 1600 °C while applying a pressure of 30 MPa, followed by heating at 100 °C/min to reach the final temperature of 1800 °C, 1900 °C, 2000 °C, and 2100 °C. At each final temperature, the pressure was increased to 40 MPa and maintained for 10 min, producing the SiC–AlN–VC ceramics.

The samples sintered at 1800 °C, 1900 °C, 2000 °C, and 2100 °C are here labeled SAV18, SAV19, SAV20, and SAV21, respectively.

2.2. Characterization

The phase compositions of the SiC multiphase ceramics were analyzed via X-ray diffraction (XRD, XRX-6000, Shimazu, Japan, 40 kV, 30 mA) with Cu-Kα radiation and a step size of 1° over a 2θ range of 10–80°. The density of the sintered samples was measured using Archimedes’ method, while the theoretical density (ρ) and lattice parameters were obtained from the XRD Rietveld refinements. The morphology of the SiC–AlN–VC ceramics was examined via field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Sigma, Zeiss, Germany) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford, UK). The high-resolution images and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns of the specimens were obtained using transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

For mechanical testing, the composite ceramics were cut into 3 × 4 × 20 mm3 specimens, and the flexural strength of the specimens was measured through three-point bending tests using a universal testing machine with a span of 16 mm and a loading rate of 0.2 mm/min. The Vickers hardness (432VD, ChangzhouTaylor, Changzhou, China) was measured on the polished surface of the SiC composite ceramics under a load of 15 N for 10 s. Each reported value represents the average of seven measurements.

The fracture toughness (KIC) was determined using the indentation fracture method proposed by Anstis [29]:

where P is the applied load (N), E is the elastic modulus (GPa), H is the hardness (GPa), and c is the radial crack length.

The friction experiments were conducted at 25 °C using a high-temperature ball-on-disk tribometer (Lanzhou Zhongke Kaihua Technology Co., Ltd., Lanzhou, China). All tests were conducted under a normal load of 15 N, a sliding speed of 0.1 m/s, a friction radius of 3 mm, and a sliding time of 180 min. WC balls (diameter of 5 mm) were used as grinding balls. The sample surfaces were polished, ultrasonically cleaned, and dried prior to testing. The wear rate (W) of the samples was calculated as [30]:

where V (mm3) is the wear volume, F (N) is the applied load, and L (m) is the total sliding distance. Each test was repeated at least three times under the same conditions to ensure good accuracy.

W = V/FL,

The thermal diffusivity (α) was measured at room temperature using a laser-flash apparatus (LFA427 Nanoflash, NETZSCH Instruments Co. Ltd., Selb, Bavaria, Germany). The sample dimensions were 10 × 10 × 2 mm3. The specific heat (Cp) was obtained via differential scanning calorimetry (DSC214, NETZSCH Instruments Co. Ltd., Selb, Bavaria, Germany). The thermal conductivity (κ) was then determined from the bulk density, thermal diffusivity, and specific heat capacity according to the following equation:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phase Composition

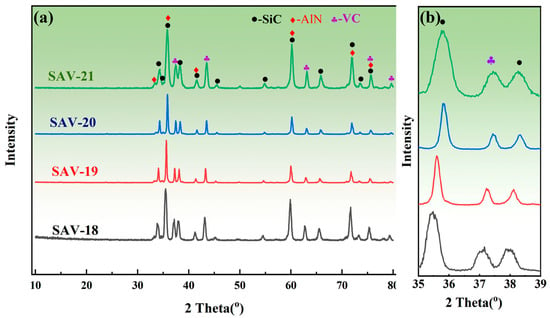

The XRD patterns of the SiC–AlN–VC samples sintered at 1800–2100 °C are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. The lattice constants of SiC and VC in the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics. The main phase of all sintered samples was α-SiC, and diffraction peaks corresponding to the AlN and VC phases were also observed. Compared with other SAVs, the diffraction peaks of SAV20 exhibited the narrowest half-peak width, indicating that the SiC composite ceramics sintered at 2000 °C had the highest degree of crystallinity. Additionally, Figure 1b shows that with increasing temperature, the diffraction peak of SiC and VC shifted slightly to the right. During the preparation process, the solid solubility of AlN in SiC reached its maximum; when the temperature is excessively high, a small amount of AlN instead precipitates from the SiC grains. This precipitation leads to a decrease in the lattice parameter, which is the reason behind the rightward shift of the diffraction peak [31]. Meanwhile, the increase in lattice parameter of VC indicates a contraction of lattice size, which implies the solid solution reaction occurs to VC.

Figure 1.

XRD patterns of the SiC multiphase ceramics (a) and the local magnified view at 35–39° (b).

Table 1.

The lattice constants of SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics.

3.2. Microstructure

3.2.1. SEM

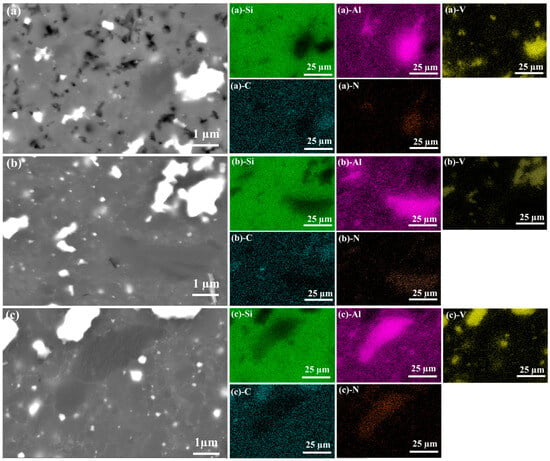

Figure 2 presents the EDS maps of SAVs. Three distinct regions were observed on the polished surface of the samples. The gray region represents the matrix, while the gray–black and white regions are dispersed within it. Based on the EDS maps, the gray, gray–black, and white regions were identified as SiC, AlN, and VC, respectively. AlN and VC exist as secondary phases. In addition, clear white linear features were observed between the SiC grains, which were previously confirmed to be the Y4Al2O9 (YAM) liquid phase [32].

Figure 2.

SEM images and corresponding EDS maps of the polished surface of (a) SAV18, (b) SAV20, and (c) SAV21.

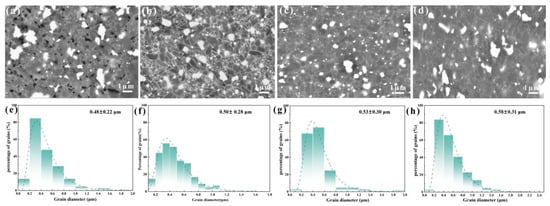

Due to the low content of the liquid phase, the grain boundaries appeared blurred, making grain size measurement difficult. To address this issue, the samples were etched for 150 s with a gas mixture consisting of 80% CF4 and 20% O2. The surface morphology of the etched samples and the corresponding grain size distributions are shown in Figure 3. The median grain diameter (D50) was defined as the midpoint of the grain size distribution: 50% (by area fraction) of the grains were coarser and 50% were finer than this median size. A large number of micropores were observed in Figure 3a (SAV18), indicating insufficient densification of this SiC composite ceramic. In contrast, the polished surfaces of SAV19 to SAV21 showed almost no pores (Figure 3b–d). Within a certain temperature range, a higher sintering temperature accelerates atomic diffusion. During sintering, Y2O3 forms a liquid phase that resides at the grain boundaries.

Figure 3.

SEM images of the SiC samples etched with 80% CF4 and 20% O2 for 150 s and corresponding grain size distributions: (a,e) SAV18, (b,f) SAV19 (c,g) SAV20, and (d,h) SAV21.

The average grain sizes of SAV18, SAV19, SAV20, and SAV21 were 0.48 ± 0.22 μm, 0.50 ± 0.28 μm, 0.53 ± 0.30 μm, and 0.58 ± 0.31 μm, respectively (Figure 3e–h). It could be concluded that the grains are relatively small, with some showing elongated morphologies. As the temperature increased, the grains grew slightly, accompanied by the dissolution of small SiC grains with high convex curvature and their subsequent reprecipitation onto larger grains, a process characteristic of Ostwald ripening [33]. At 2000 °C, the grain size distribution became more uniform.

At 2000 °C, the atoms gained sufficient energy for migration and rearrangement. Additionally, the amount of liquid phase was moderate. This moderate amount of liquid phase not only wets the particle surfaces to reduce the interfacial energy and promote particle rearrangement and pore filling, but also inhibits excessive dissolution or abnormal grain growth [34]. At temperatures lower than 2000 °C (SAV18), the insufficient atomic diffusion and low liquid-phase content hindered effective pore elimination. At temperatures higher than 2000 °C (SAV21), the excessive atomic diffusion and volatilization of the liquid phase caused abnormal grain growth, the formation of large intergranular voids, and reduced relative density [35].

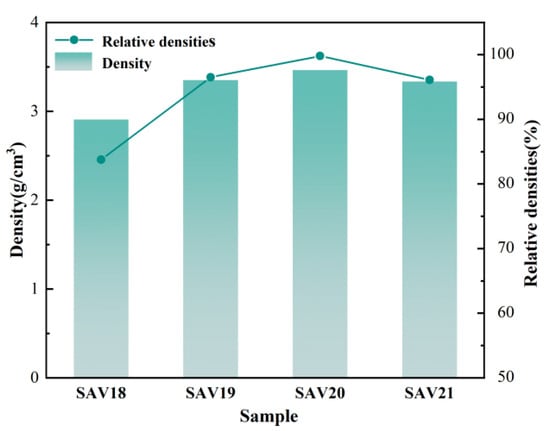

Figure 4 shows the relative density of the SiC multiphase ceramics sintered at different temperatures. According to Figure 4, the sample density increased significantly with rising sintering temperature; however, the relative density of the SiC multiphase ceramics first increased and then decreased. SAV20 exhibited the highest relative density, namely 99.8%. This trend is consistent with the microstructural evolution shown in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Densities and relative densities of the SiC multiphase ceramics.

3.2.2. TEM

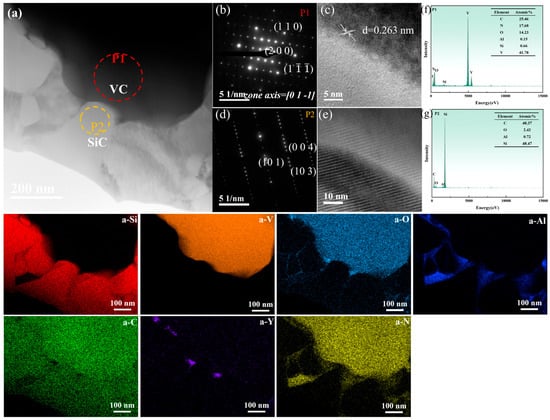

To investigate the interfacial reactions and crystal structures in the SiC multiphase ceramics, TEM was employed to characterize the samples. The bright-field (BF) image in Figure 5a shows a distinct transition layer between the two phases, with its morphology differing significantly from that of the adjacent crystalline phases. From the corresponding EDS mappings, this transition layer was identified as the YAM liquid phase [32].

Figure 5.

TEM images and EDS mapping of SAV20: (a) BF image; (b) SAED pattern; (c) HRTEM image and (f) elemental composition of region P1 in (a); (d) SAED pattern; (e) HRTEM image; and (g) elemental composition of region P2 in (a); the rest are EDS mappings of (a).

The calibration of the SAED pattern for region P1 (Figure 5b) shows that the (1 1 0), (2 0 0), and (1

1) crystal planes corresponded to the [0 1 −1] zone axis. This matches the face-centered cubic (FCC) structure of VC, confirming that region P1 is the VC phase. In Figure 5c, the stripe spacing was 0.263 nm, corresponding to the crystal plane (1 1 1) of VC. However, the spacing was significantly larger than the interplanar spacing of the plane (1 1 1) of VC (PDF#65-8818), which was 0.241 nm. Meanwhile, Figure 5f shows that in this area, apart from the presence of V and C elements, there were also a large number of N atoms. Therefore, the increase in interplanar spacing or lattice parameter of VC might be attributed to the incorporation of N atoms into the VC lattice. The SAED pattern of region P2 (Figure 5d),HRTEM image (Figure 5e), and elemental composition (Figure 5f) revealed crystal planes of (0 0 4), (1 0 1), and (1 0 3) of the SiC in this region.

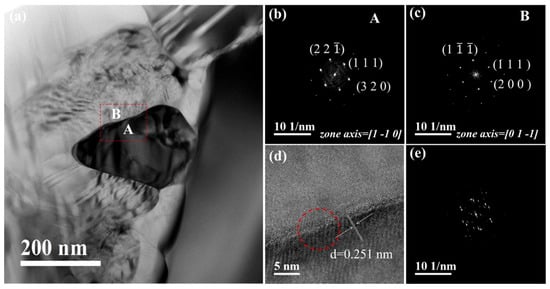

The TEM image of the interface between AlN and VC is shown in Figure 6. According to Figure 6b,c, A in Figure 6a is attributed to “VC” and B to “AlN”. Figure 6d is the transition zone between VC and AlN. The spacing of the stripes of VC was 0.251 nm ((1 1 1) crystal plane). Compared with the VC grains adjacent to SiC (Figure 5c, 0.263 nm), the width of the stripes became narrower. This indicates that the N atoms in the adjacent AlN may have replaced the C atoms, thus causing the stripes to narrow.

Figure 6.

TEM images and SAED patterns of SAV20: (a) In the red box, the dark area labeled A represents VC, and the light area labeled B represents AlN; (b) SAED pattern of A in (a); (c) SAED pattern of B in (a); (d) The red circle marks the transition region between VC and AlN; and (e) FFT images of selected area in (d).

From the above, during SPS at high temperature, AlN likely decomposes as follows [36]:

2AlN → 2Al + N2

The released N atoms diffuse into the lattice vacancies, interstitial sites, or chemically active sites of VC, forming V–N bonds or V(C,N) solid solutions according to:

VC + N2 → V(C,N)

From Figure 6b,d, it shows that the lattice parameter of VC became smaller, suggesting that the N atoms are predominantly incorporated as part of the V(C,N) solid solution. The radius difference between C4− and N3− was only 4.3%, and this excellent size matching facilitates the substitution of C atoms by N atoms in the lattice. From a thermodynamic perspective, the Gibbs free energy of formation for the V(C,N) solid solution is lower than that of the (VC + VN) mechanical mixture, and as the N content increases, the free energy continues to decrease until a homogeneous solid solution is stabilized [37].

Previous literature confirmed that the V–C–N system can form a continuous solid solution at high temperatures. In other words, N atoms can fully replace C atoms to form VN, or partially replace them to form V(C1−xNx) phases, among which only V(C,N) is stable [38]. From a kinetic perspective, the high temperature, high pressure, plasma effect, and vacuum environment of SPS enhance N2 dissociation, adsorption, and diffusion, reduce the energy barrier for solid solution formation, and ensure the efficient incorporation of N atoms into the VC lattice [30].

3.3. Mechanical Properties

The hardness and flexural strength of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics are presented in Table 2. As the sintering temperature rose from 1900 °C to 2100 °C, the hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness of the SiC multiphase ceramics first increased and then decreased. Among all samples, SAV20 sintered at 2000 °C exhibited the best properties, with a hardness of 28.7 GPa, a flexural strength of 508 MPa, and a fracture toughness of 5.3 MPa·m1/2, all of which were significantly higher than those of SAV19 and SAV21.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the SiC–AlN–VC composite ceramics.

Based on the microstructure and relative density analyses, atomic diffusion and liquid-phase formation are optimal at 2000 °C, leading to tightly bonded grains and a high relative density, which reduce crack initiation and propagation. Additionally, the uniform grain size distribution contributes to improvements in hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness. The fine SiC grains also enhance the material strength through the fine-grain strengthening mechanism [39]. AlN and VC exist as secondary phases. The interface formed between AlN and SiC generates thermal residual stresses, which hinder crack propagation [40]. The VC particles pin the grain boundaries, inhibit abnormal SiC grain growth, maintain a uniform microstructure, and collectively enhance the toughness and strength of the material [41]. At this stage, the interfaces between the various phases show good bonding, and the strong grain boundary adhesion effectively transfers the load, prevents premature interfacial failure, and ensures overall mechanical integrity.

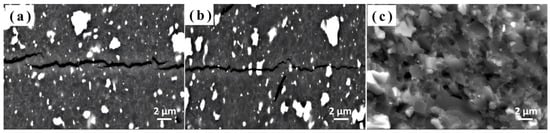

At 2000 °C, the various phases were uniformly distributed, and the grain boundaries were well-bonded, allowing this crack deflection and bridging mechanism to operate more effectively (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

SEM image of the crack path in (a) SAV20, (b) SAV21, and fracture surface of SAV21, (c) The cross-sectional image of SAV21.

In contrast, at 2100 °C, due to the liquid phase evaporation caused by high temperature, the pores in the sample increased (Figure 7b,c), resulting in a decrease in its strength. Correspondingly, the main microscopic fracture mechanisms were intergranular fracture and transgranular fracture (Figure 7c).

Table 3 compares the mechanical properties of the SiC ceramics fabricated in this study with those reported in Refs. [18,21,23,28]. The Vickers hardness (28.7 GPa) of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics developed in this study was lower than that of the SiC–AlN ceramics reported by Li et al. (31.9 GPa) [28]. This could be attributed to the lower content of the AlN phase (which has a relatively low hardness) in the ceramics prepared by Li, resulting in a higher hardness. However, the hardness of the ceramics prepared in this study was higher than that of the SiC–TiC–Al2O3/Y2O3 system (26.7 GPa, 24.5 GPa) [21], SiC–TaC system (25.7 GPa) [23], and high-AlN-content system (55 wt.% SiC–45 wt.% AlN, 20.4 GPa) [18]. This advantage can be attributed to the high relative density (99.8%) achieved by SPS in this study, combined with the strengthening effect of the VC phase. As a hard phase, VC enhances the overall hardness of the ceramics. Furthermore, the rapid sintering nature of SPS inhibits excessive grain growth, thereby maintaining the fine-grain strengthening effect.

In addition, the fracture toughness (5.25 MPa·m1/2) of the SiC multiphase ceramics prepared in this study was lower than that of the SiC–5 wt.% TiC system reported in Ref. [21] (5.8 MPa·m1/2). In that system, the TiC particles located at the SiC grain boundaries reduced grain boundary migration, suppressed excessive grain growth, increased relative density, and yielded a fine-grained SiC composite. Moreover, crack deflection and crack bridging enhanced the fracture toughness. However, when the TiC content exceeded the optimal level, the relative density decreased, and the performance deteriorated. Nevertheless, the fracture toughness of the ceramics fabricated in this study was higher than that of the ceramics reported in Ref. [23] (3.5 MPa·m1/2) and [28] (3.6 MPa·m1/2), demonstrating an advantageous balance between hardness and toughness.

Table 3.

Hardness and fracture toughness of the SiC–AlN–VC ceramics developed in this study compared with those of similar materials reported in the literature.

Table 3.

Hardness and fracture toughness of the SiC–AlN–VC ceramics developed in this study compared with those of similar materials reported in the literature.

| Material | Sintering Method | Density (%) | Vickers’ Hardness (GPa) | Fracture Toughness (MPa·m1/2) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiC-10 vol.%AlN-10 vol.%VC | SPS | 99.8 | 28.7 | 5.25 | This work |

| SiC-5 wt.%TiC- 10 wt.%Al2O3/Y2O3 | PS | 97.4 | 26.7 | 5.8 | [21] |

| SiC-10 wt.%TiC- 10 wt.%Al2O3/Y2O3 | PS | 92.4 | 24.5 | 4.7 | [21] |

| SiC-10 wt.%TaC | SPS | 99.7 | 25.7 | 3.5 | [23] |

| SiC | PS + Hot Isostatic Pressing(HIP) | ~95% | 29.8 | 3.6 | [12] |

| SiC-5 mol%AlN | PS + HIP | ~100% | 31.9 | 4.1 | [28] |

| 55 wt.%SiC-45 wt.%AlN | SPS | 96.6 | 20.4 | 4.8 | [18] |

3.4. Tribological Properties

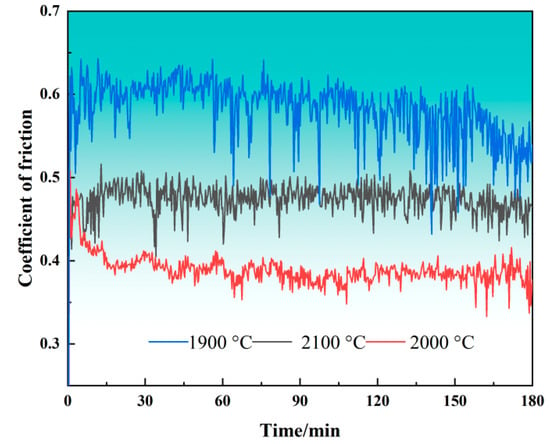

Figure 8 shows the coefficient of friction (CoF)–time curves of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics. Table 4 lists the average CoF and average specific wear rate (WR) of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics. As can be seen from Figure 8, under identical test conditions, the CoF–time curve of SAV20 displayed small fluctuations and remained relatively stable, while those of SAV19 and SAV21 showed larger fluctuations. According to Table 3, with increasing temperature, the CoF of the SiC multiphase ceramics first decreased from 0.51 to 0.41 and then increased to 0.45. Thus, SAV20 had the smallest CoF, with a specific WR of 3.41 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m). The specific WRs of SAV19 and SAV21 were 2.78 × 10−5 and 3.90 × 10−5 mm3/(N·m), respectively.

Figure 8.

Variation in the CoF of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics with time.

Table 4.

Average CoF and WR of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics.

Llorente fabricated SiC composites containing 0–55 vol.% short carbon fibers via HP. Under an 8 N load, these composites exhibited CoF values ranging from 0.2 to 0.4 and specific WR values of (1.5–15) × 10−4 mm3/(N·m) [42]. Pant prepared SiC–(10 wt.%) TiB2 and SiC–(10 wt.%) TiB2–(5 wt.%) TaC composites at 2000 °C using SPS. Under a 10 N load, their CoF values ranged between 0.4 and 0.6, with specific WR values of (2.3–6) × 10−4 mm3/(N·m) [43]. Chodisetti produced SiC composites containing 0–30 wt.% TiB2, with CoF values ranging from 0.3 to 0.55 and specific WR values of (2.5–16) × 10−6 mm3/(N·m) [44].

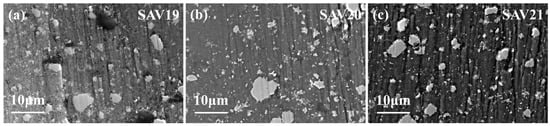

The morphology of the worn surfaces of the SiC multiphase ceramics is shown in Figure 9. The worn surface of SAV19 (Figure 9a) contained large holes and pits formed after particle detachment. This occurs because the internal defects act as stress concentration sites during the friction process, promoting material removal and surface damage. The worn surface of SAV20 (Figure 9b) was relatively smooth. An appropriate sintering temperature thus promotes a denser structure and, during the friction process, the interaction between the friction pairs is dominated by stable mild adhesion and abrasive wear. The worn surface of SAV21 (Figure 9c) showed defect levels and damage severity between those of SAV19 and SAV20.

Figure 9.

SEM images of the abrasion marks on the surface of the multiphase ceramic samples: (a) SAV19, (b) SAV20, and (c) SAV21.

3.5. Thermal Properties

Table 5 presents the thermal properties of the SiC multiphase ceramics. The thermal conductivities of SAV19, SAV20, and SAV21 were 51.2, 58, and 54 W/(m·K), respectively. As the sintering temperature increased, the thermal conductivity of the SiC ceramics peaks at 2000 °C and then decreased. When the sintering temperature is either higher or lower than 2000 °C, the reduction in thermal conductivity is mainly associated with changes in the relative density of the samples.

Kim et al. reported that increasing the AlN reduced the thermal conductivity of SiC–AlN composite ceramics. They attributed this effect to point defect scattering caused by the dissolution of the Al and N solid solutions into the SiC grains [45]. Lu et al. observed that increasing the particle size (0.04, 0.5, 2, and 5 μm) decreased the relative density of SiC–AlN composites. They noted that when the SiC particle size was 2 μm, the sintered AlN–SiC product achieved the highest thermal conductivity due to its dense and homogeneous microstructure [46]. Kultayeva investigated the influence of the sintering atmosphere on the thermal conductivity of SiC composites, finding that the samples sintered in N2 displayed higher thermal conductivity due to reduced residual porosity and less extensive solid solution formation [47]. For SiC–AlN ceramics containing 10 wt.% AlN, the thermal conductivity has been reported to range from 27 to 50 W/(m·K) [14,48]. In contrast, the addition of VC particles may improve the material’s thermal conductivity, largely because of the high densification of the multiphase ceramics.

Table 5.

Thermal conductivity of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics compared with that of similar materials reported in the literature.

Table 5.

Thermal conductivity of the SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics compared with that of similar materials reported in the literature.

| Material | Sintering Conditions | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiC + 10 vol.%AlN + 10 vol.%VC | SPS: 1900 °C/2000 °C/2100 °C/40 MPa | 51.2/58/54 | This work |

| SiC + 10 wt.%AlN + B4C/C | PS: 2170 °C/30 min Anneal: 1950 °C/1 h | 35 | [48] |

| SiC + 47.5 mol%AlN + 5mol%Y2O3 | PS: 2000 °C/8 h/Ar PS: 2000 °C/8 h/N2 | 24.5 28.6 | [47] |

| SiC + 2 wt.%AlN SiC + 10 wt.%AlN SiC + 35 wt.%AlN | HP: 1950 °C/2 h/ 40 MPa/Ar | 104.1 49.8 35.1 | [45] |

| SiC + 10 wt.%AlN + 2.5 wt% Y2O3/Al2O3 | PS: 2353 K/2 h | 27.5 | [14] |

| 0.5/2/5 μmSiC + AlN + Y2O3 | PS:2000 °C/N2 | 37.6/45.5/30 | [46] |

4. Conclusions

1. In this study, dense SiC–AlN–VC multiphase ceramics were fabricated via SPS using α-SiC, AlN, and VC powders in a volume ratio of 8:1:1 as raw materials and 1 wt.% Y2O3 as a sintering aid. AlN and VC particles were uniformly dispersed, and the YAM liquid phase at the grain boundaries promoted densification. The optimal sintering temperature was 2000 °C, at which the ceramic achieved a relative density of 99.8%. At this temperature, the hardness, flexural strength, and fracture toughness were 28.7 GPa, 508 MPa, and 5.25 MPa·m1/2, respectively; the CoF and WR were 0.41 and 3.41 × 10−5 mm/(N·m), respectively; and the thermal conductivity was 58 W/(m·K).

2. At high temperatures, the N atoms released from the AlN decomposition diffused into the VC lattice to form V(C,N) solid solutions, which strengthened interfacial bonding. The combined effects of the thermal residual stresses at the AlN–SiC interface, grain boundary pinning by the VC particles, and V(C,N) solid solution formation improved the mechanical properties of the SiC multiphase ceramics through the mechanisms of crack deflection and crack bridging.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.H.; methodology, W.H. and H.Z.; validation, L.L. and M.G.; investigation, L.L. and M.G.; data curation, L.L. and M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L. and M.G.; writing—review and editing, W.H. and H.Z.; funding acquisition, W.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Science and Technology Support Project of Yinchuan (Grant no. 2025GX07), the Central Government’s Special Project for Guiding Local Science and Technology Development in Ningxia Province, China (Grant no. 2025FRE05004), and the High-level Talent Project (Natural Sciences) of North Minzu University in 2025 (2025BG188).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, J.; Zhou, X.; Zou, S.; Chen, L.; Tatarko, P.; Dai, J.; Huang, Z.; Huang, Q. Low-Temperature Pr3Si2C2-Assisted Liquid-Phase Sintering of SiC with Improved Thermal Conductivity. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 105, 5576–5584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, R.; Kim, Y. Effect of AlN Addition on the Electrical Resistivity of Pressureless Sintered SiC Ceramics with B4C and C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 6086–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Fang, D. Progress and Challenges towards Additive Manufacturing of SiC Ceramic. J. Adv. Ceram. 2021, 10, 637–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huczko, A.; Dąbrowska, A.; Savchyn, V.; Popov, A.I.; Karbovnyk, I. Silicon Carbide Nanowires: Synthesis and Cathodoluminescence. Phys. Status Solidi B 2009, 246, 2806–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tynyshbayeva, K.M.; Kozlovskiy, A.L. The Effect of Temperature Factor During Heavy Ion Irradiation on Structural Disordering of SiC Ceramics. Opt. Mater. X 2025, 25, 100383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.S.; Suzdal’tsev, A.V.; Anfilogov, V.N.; Farlenkov, A.S.; Porotnikova, N.M.; Vovkotrub, E.G.; Akashev, L.A. Carbothermal Synthesis, Properties, and Structure of Ultrafine SiC Fibers. J. Inorg. Mater. 2020, 56, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Koh, Y.R.; Mamun, A.; Shi, J.; Bai, T.; Huynh, K.; Yates, L.; Liu, Z.; Li, R.; Lee, E.; et al. Experimental Observation of High intrinsic Thermal Conductivity of AlN. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 044602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liu, Z.; Harris, J.; Diao, X.; Liu, G. High thermal conductive AlN substrate for heat dissipation in high-power LEDs. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 1412–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Alderman, B.; Huggard, P.; Zhang, B.; Fan, Y. 190 GHz High Power Input Frequency Doubler Based on Schottky Diodes and AlN Substrate. IEICE Electron. Expr. 2016, 13, 20160981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Jin, X.; Kan, Y.; Hu, J.; Dong, S. Fabrication and Properties of AlN-SiC Multiphase Ceramics via Low Temperature Reactive Melt Infiltration. J. Inorg. Mater. 2023, 38, 1223–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Gao, Y. Synthesis Mechanism of AlN–SiCSolid Solution Reinforced Al2O3 Composite by Two-step Nitriding of Al–Si3N4–Al2O3 Compact at 1500 °C. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 22022–22029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Watanabe, R. Preparation and Mechanical Properties of SiC-AlN Ceramic Alloy. J. Mater. Sci. 1991, 26, 4813–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Guo, W.; Sun, S.; Zou, J.; Wu, S.; Lin, H. Texture, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties of AlN-based Ceramics with Si3N4–Y2O3 Additives. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 3380–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besisa, D.; Ewais, E.; Shalaby, E.; Usenko, A.; Kuznetsov, D.V. Thermoelectric Properties and Thermal Stress Simulation of Pressureless Sintered SiC/AlN Ceramic Composites at High Temperatures. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2018, 182, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, B.; Ren, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, J. High-ThermalConductivity AlN Ceramics Prepared from Octyltrichlorosilane-Modified AlN Powder. Processes 2023, 11, 1186. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Yuan, J.; Guo, W.; Duan, X.; Jia, D.; Lin, H. Thickness Effects on the Sinterability, Microstructure, and Nanohardness of SiC-based Ceramics Consolidated by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 107, 777–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Mitomo, M.; Nishimura, T. High-Temperature Strength of Liquid-Phase-Sintered SiC with AlN and Re2O3 (RE = Y, Yb). J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2002, 85, 1007–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Patel, P.; Reddy, J.; Prasad, V.V. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of a SiC Containing Advanced Structural Ceramics. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2019, 84, 105030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Deng, C.; Ding, J.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Dong, B.; Xing, G.; Zhu, Q.; Zheng, Y. Enhanced mechanical properties of R–SiC honeycomb ceramics with in situ AlN–SiC solid solution. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 32153–32163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Shi, P.; Zhang, C.H.; Wu, M. First-Principles Study on Interfacial Structure and Strength of SiC/VC Nano-Layered Hard Coatings. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2023, 230, 112532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; You, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.; Kan, Y.; Xue, Y.; Dong, S. Synergistic Effects of Al2O3 and Y2O3 on Enhancing the Wet-Oxidation Resistance of SiC Ceramics. Corros. Sci. 2025, 249, 112848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhang, G.; Sun, S.; Liu, H.; Kan, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, C. ZrO2 Removing Reactions of Groups IV–VI Transition Metal Carbides in ZrB2 Based Composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Chaudhary, K.; Gupta, Y.; Kalin, M.; Kumar, B. Erosive Wear Behavior of Spark Plasma-Sintered SiC-TaC Composites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2022, 19, 1691–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Zhang, B.; Liu, X.; Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Yin, J. β→α Phase Transformation and Properties of Solid-State-Sintered SiC Ceramics with TaC Addition. Materials 2023, 16, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Oh, S.; Ju, J. Effect of Transition Metal on Properties of SiC Electroconductive Ceramic Composites. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2004, 53, 352–357. [Google Scholar]

- Khodaei, M.; Yaghobizadeh, O.; Safavi, S.; Ehsani, N.; Baharvandi, H.R.; Esmaeeli, S. The Effect of TiC Additive with Al2O3-Y2O3 on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of SiC Matrix Composites. Adv. Ceram. Prog. 2020, 6, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S. Effects of VC Additives on Densification and Elastic and Mechanical Properties of Hot-Pressed ZrB2-SiC Composites. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 4010–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Zhang, G.; Kan, Y.; Wang, P. Hot-Pressed ZrB2-SiC Ceramics with VC Additives, Chemical Reaction, Microstructures, and Mechanical Properties. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2009, 92, 2838–2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anstis, G.; Chantikul, P.; Lawn, B.; Marshall, D. A Critical Evaluation of Indentation Techniques for Measuring Fracture Toughness, I, Direct Crack Measurements. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1981, 64, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, A.; Han, J.; Meng, J. Microstructure, Mechanical and Tribological Properties of CoCrFeNiMn High Entropy Alloy Matrix Composites with Addition of Cr3C2. Tribol. Int. 2020, 151, 106436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B. Research on Preparation Process and Properties of Gelcasting SiC-AlN Multiphase Ceramics; Harbin Inst. Technol: Harbin, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M.; Zhang, H.; Hai, W. High Strength of SiC–AlN–TiB2–VC Multiphase Ceramics Induced by Interface Reactions. Ceram. Int. 2024, 8, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noviyanto, A.; Min, B.; Yu, H.; Yoon, D. Highly Dense and Fine-Grained SiC with a Sc-Nitrate Sintering Additive. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2014, 34, 825–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, A.; Borrero-López, O.; Quadir, M.; Guiberteau, F. A Route for the Pressureless Liquid Phase Sintering of SiC with Low Additive Content for Improved Sliding-Wear Resistance. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 32, 965–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Yao, X.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, Y. In Situ Analysis of the Liquid Phase Sintering Process of α-SiCCeramics. J. Inorg. Mater. 2016, 31, 443–448. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y.; Shi, L. A Comparison of the Thermal Decomposition Mechanism of Wurtzite AlN and Zinc Blende AlN. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 11216–11227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Moon, A.; Kim, W.; Kim, J. Investigation of the Conditions Required for theFormation of V(C,N) During Carburization of Vanadium or Carbothermal Reduction of V2O5 under Nitrogen. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 2847–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompe, R. Some Thermochemical Properties of the System Vanadium-Nitrogen and Vanadium-Carbon-Nitrogen in the Temperature Range 1000–1550 °C. Thermochim. Acta. 1982, 57, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, M.; Yaghobizadeh, O.; Baharvandi, H.; Dashti, A. Effects of Different Sintering Methods on the Properties of SiC, TiC, SiC–TiB2 Composites. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2018, 70, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, H.; Khodaei, M.; Yaghobizadeh, O.; Ehsani, N.; Baharvandi, H.R.; Alhosseini, S.H.N.; Javi, H. The effect of AlN-Y2O3 compound on properties of pressureless sintered SiC ceramics-A review. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. 2021, 95, 105420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, S.; Asl, M.; Kakroudi, M.; Salahimehr, B.; Mahmoodipour, K. On the Oxidation Behavior of ZrB2–SiC–VC Composites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Tec. 2021, 18, 2306–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorente, J.; Román-Manso, B.; Miranzo, P.; Belmonte, M. Tribological Performance Under Dry Sliding Conditions of Graphene/Silicon Carbide Composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2016, 36, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, H.; Debnath, D.; Chakraborty, S.; Wani, M.; Das, P. Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Spark Plasma Sintered SiC-TiB2 and SiC–TiB2–TaC Composites, Effects of Sintering Temperatures (2000 degrees C and 2100 degrees C). J. Tribol. 2018, 140, 0742–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodisetti, S.; Kumar, B. Tailoring Friction and Wear Properties of Titanium Boride Reinforced Silicon Carbide Composites. Wear 2023, 526–527, 204886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, Y.; Lim, K.; Nishimura, T.; Narimatsu, E. Electrical and Thermal Properties of SiC–AlN Ceramics without Sintering Additives. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2015, 35, 2715–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.P.; Zang, X.R.; Du, B. Investigation of the Effect of the SiC Particle Size on the Properties of the AlN–SiC Composite Ceramic. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2021, 261, 124222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kultayeva, S.; Kim, Y. Mechanical, Thermal, and Electrical Properties of Pressureless Sintered SiC–AlN Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 19264–19273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yao, X.; Li, Y.; Lian, H.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Li, X.; Qiu, T.; Chen, Z.; et al. Effect of AlN Addition on the Thermal Conductivity of Pressureless Sintered SiC Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 13547–13552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.