Abstract

Recent years have shown that additive manufacturing is able to significantly increase the potential for enhancing lightweight structural design. In particular, strut-based lattices have attracted considerable research interest due to their promising mechanical performance in lightweight engineering applications. While the quasi-static properties of such lattices are relatively well established, their fatigue behavior remains insufficiently understood. This work presents a numerical investigation of the fatigue life of laser powder bed-fused strut-based lattices using the finite element method (FEM). Periodic AlSi10Mg lattice structures with two different unit cells, bcc and , and three different aspect ratios were analyzed under uniaxial compression–compression loading. The stress-life approach was used to model the fatigue failure of the representative unit cells in the high-cycle fatigue region. The numerical predictions were compared with experimental results, showing good agreement between simulations and physical tests. The findings highlighted that the fatigue response was primarily governed by aspect ratio, unit cell topology, bulk material properties, and mean stress imposed by the load ratio. Moreover, stress concentrations arising from notch effects in the nodal regions were identified as critical fatigue crack initiation sites.

1. Introduction

Additive manufacturing (AM) technology has revolutionized structural design by enabling the manufacturing of highly complex geometries, which were previously impractical or impossible using conventional manufacturing technologies. Laser powder bed fusion (PBF-LB) distinguishes itself among AM technologies through the production of complex metallic structures with excellent mechanical performance, as demonstrated in applications such as cooling channels [1,2], custom dental implants [3], and heat exchangers [4,5]. Specifically, the manufacturing of complex and small lattice structures has gained widespread attention in recent years, based on their high-performing mechanical properties and inherent lightweight potential. These regular and periodic structures are attractive for many industries due to the possibility of shaping the mechanical properties such as effective stiffness and strength to the application requirements. Hereby, the strut-based lattice structures have attracted widespread attention due to their simple design and geometric form, as well as their low modulus, especially for bio-material applications [6,7]. Their highly adaptable spatial configuration, which can be easily tailored to diverse patterns, makes them more desirable than sheet and plate lattices and highlights the substantial potential for further design improvements [8]. Therefore, classical configurations according to the crystal structure have been proposed, such as face-center, body-center, diamond-like, and their combinations with each other. Maxwell’s stability criterion is used to describe the deformation behavior based on the degree of strut connectivity and the resulting degrees of freedom within a unit cell [9,10]. According to Maxwell’s stability criterion, cell configurations can be categorized as (1) bending-dominated, exhibiting superior energy absorption capacity, or (2) stretching-dominated, exhibiting high stiffness and initial collapse strength [11]. Hereby, the fundamental work by Gibson and Ashby [12] examined the deformation behavior and mechanical properties of strut-based lattices analytically and was further carried out by Tankasala et al. [13] and Fleck et al. [14]. Three-dimensional (3D) constitutive models have been derived by using the strain energy and deformation method, and the Timoshenko beam assumption [12,14]. These closed-form equations, derived from classical beam theory, show limitations when applied to highly complex topologies, as they neglect manufacturing effects such as strut waviness and surface roughness, and fail to accurately capture the stress–strain state in the nodal regions [11]. In particular, the material distribution in the nodal regions has been shown to strongly influence the stiffness and global mechanical response of lattice structures. As a result, significant deviations between theoretical predictions and experimental observations are often reported [9,11,15]. In contrast, the finite element method based on continuum elements can capture the most complex lattice structures in the finest details without simplifying assumptions to capture the mechanical behavior, with the only limitation being the computational power and analysis time [11,16]. The models provide the highest accuracy and most faithful reproduction of any morphological feature, as stated by Dong et al. [17]. Although quasi-static properties have been well characterized for strut-based lattice structures and numerical models of 3D continuum elements have been successfully compared with experimental data, as shown in [18,19,20], the fatigue behavior of different unit cells in combination with different base materials and load conditions remains insufficiently investigated. The development of next-generation industrial components requires the full integration of lattice structures as primary load-bearing elements [21]. Accurate and computationally efficient methods to quantify their effective mechanical properties are essential, with fatigue life prediction representing the most critical and underdeveloped aspect [11]. Therefore, advancing predictive fatigue models is crucial for the reliable deployment of additively manufactured lattices in safety-critical applications.

The mechanical properties of a lattice structure are mainly influenced by four factors: the relative density, which reflects the geometric dimensions; the unit cell topology; the strut shape; and the properties of the base material [22]. AlSi10Mg is a widely utilized aluminum alloy in PBF-LB processing, primarily due to its favorable strength-to-weight ratio and improved mechanical properties compared to the corresponding casting alloy [23]. The combination of high geometric complexity and low material density makes this alloy particularly attractive for lightweight structural applications, such as lattice structures, in the automotive and aerospace sectors. In the case of fatigue properties, different authors have highlighted the effect of process-induced defects in PBF-LB components and lattice structures [24,25,26,27]. In addition to the printing orientation [28,29], the surface roughness [30,31], porosity [32], as well as residual stresses [33] can directly affect the fatigue performance. In order to describe the fatigue behavior of metallic materials, S-N curves are widely used in experimental studies. For cellular materials this most intuitive and phenomenological approach is also employed to characterize the fatigue performance. Several experimental investigations have demonstrated that the fatigue behavior of additively manufactured lattice structures can be effectively characterized using the Basquin-type relation, analogous to bulk metallic materials [30,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. Recent contributions regarding fatigue life prediction based on numerical finite element models can be categorized into two main modeling methods: defect-free modeling and modeling with defects [20]. Hereby, defect-free models are based on the ideal CAD design [7,41,42,43,44], while -CT scans [16,34,45,46,47] are used to reconstruct the as-manufactured topology of the structure. De Biasi et al. [48] proposed a fatigue life prediction method based on the Finite Cell Method using the average strain energy density criterion, which reconstructs key geometrical features and defects from -CT images of an actual part. The method exhibited solid agreement with the experimental fatigue results and statistically predicted failure locations within the specimen. The main drawback of this methodology was the requirement to fully capture the as-built specimen geometry, which inevitably led to high computational costs and statistical inaccuracies between different samples, as well as the post-processing of the obtained scan images. Li et al. [46] also used X-ray computed tomography of single struts in order to predict the fatigue crack growth with the finite element method. Moreover, classical modeling of defects is addressed by different authors, for example, to showcase the strut waviness [22,49], different radius size distributions of the struts [50], or the equivalent strut diameter measured from the relative density. In general, damage, failure, or local deformation of each strut leads to a reduction in the macroscopic stiffness of the entire structure, which needs to be considered in simulations. Lozanovski et al. [51] employed -CT to assess variations in the principal moment of inertia, the orientation of the principal axes, and the deflection at the strut center in studies modeling the mechanical behavior of lattice structures. Gross et al. [52] investigated the dependence of elastic moduli on the concentration and distribution of missing struts using experiments, finite element simulations, and analytical models. The results demonstrate that highly connected architectures exhibit defect responses comparable to those of isotropic homogeneous materials, a finding that was verified experimentally. Since modeling internal crack propagation and stress redistribution during every loading cycle is highly time-intensive, most researchers have addressed this issue by assuming that the influence of internal crack propagation is negligible compared to strut failure [22]. Based on that assumption, the damage accumulation relationship according to Miner’s rule is used. Hedayati et al. [53] accurately predicted the S-N curve of porous Ti-6Al-4V structures up to 60% of the yield stress by using the material properties of the base material. In their iterative algorithm, each FE simulation step corresponded to a cycle increment, which was adapted based on failure events during loading. Stress concentrations were considered by applying a single stress concentration factor for each lattice type. Zagarian et al. [22,49] investigated the fatigue behavior of three different unit cells with relative densities between 0.1 and 0.3 based on a linear elastic FE-based method with beam elements and showed a good agreement with the experimental results from the literature. Furthermore, the authors stated that by incorporating manufacturing irregularities based on research material data from single-strut experiments, their model was capable of taking residual stresses, grain size, and stress concentration effects into account. In addition, Mozafari et al. [54] presented an experimentally validated framework for predicting the fatigue life of additively manufactured microlattice structures, combining a microplasticity-based constitutive model with a fully implicit finite element implementation and homogenization procedure. Another promising modeling technique is the homogenization method which was introduced by different authors, leading to computationally efficient models [55,56]. In this approach, the complex geometry of lattice structures is replaced by a solid, non-porous material with equivalent effective mechanical properties to the cellular material under investigation. Although this homogenization-based method is computationally efficient and provides accurate predictions of the displacement field, it lacks experimental validation of fatigue behavior [57]. Nevertheless, it does not account for the actual porous geometry of the lattice and is therefore unable to capture the stress concentrations arising from the structural topology. As a result, it is challenging to identify highly stressed regions in homogenized models, which in turn limits the accuracy of fatigue life estimation based on homogenized data. In order to accurately predict the fatigue properties, the determination of the elastic properties is crucial and inaccuracies in the determination of the linear elastic regime must be avoided.

Thus, the aim of this work is to examine the linear elastic behavior of two representative bending- and stretching-dominated structures under uniaxial compression–compression loading by using full-scale finite element analyses and experimental investigations. Hereby, three different relative densities are examined. Based on the linear elastic finite element results, fatigue life predictions are performed by virtue of the linear damage accumulation relationship according to Miner’s rule. Furthermore, the effect of mean stress is assessed as a function of the applied load ratio. Complementary experimental fatigue tests are performed and the results are systematically compared with the numerical predictions. It is shown that the failure pattern of the considered lattice structures under quasi-static and cyclic loading is similar, and hence, based on the detailed discussion of the stress field of the full-scale finite element analysis, an explanation of the specific failure modes is provided. The efficient modeling approach can serve as a basis for further studies, combined with experimental validation, to determine the dominant parameters affecting the structural behavior.

2. Finite Element Analysis

In the current section, the full-scale, three-dimensional finite element computations carried out using the commercial tools Abaqus 2023 and fe-safe 2023 are presented. Fe-safe is a specialized software tool for fatigue analysis based on FEA results. In order to conduct numerical fatigue analyses, fe-safe needs stress and strain data obtained from the quasi-static finite element simulations in order to perform fatigue damage and life estimations. In this study, damage is defined in the framework of the linear damage accumulation hypothesis according to Miner. Therefore, the term does not refer to a directly measurable physical quantity such as microcracks, voids, or localized plastic deformation, but rather to a phenomenological variable representing the progressive consumption of the fatigue life of the material. The simulations are performed by means of the following material properties:

2.1. Design Setup

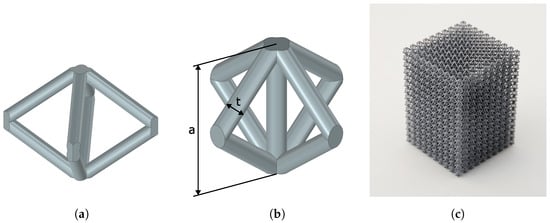

The considered unit cells for the investigations of the strut-based lattice specimens under compression–compression loading are the body-centered cubic bcc for bending-dominated behavior, illustrated in Figure 1a, and the face-centered cubic with z-reinforcement f2ccz as a representative for stretch-dominated behavior, shown in Figure 1b. An important parameter to describe the geometry of a unit cell is the aspect ratio (), which is directly correlated to the relative density of the lattice structure:

Herein, a represents the unit cell length and t the strut diameter. In the context of this study, the unit cell length is defined as mm for the numerical and experimental investigations. The square cross-section of the specimen is determined by the given number of unit cells in the plane. Thus, the number of unit cells of the plane is defined as . The actual lattice structure is obtained from the periodic repetition of the unit cell in the x, y, and z directions. Accordingly, the total number of unit cells within a lattice structure can be determined as follows:

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the considered body-centered cubic (bcc, (a)) unit cell and the face-centered cubic unit cell with z-reinforcement (f2ccz, (b)), as well as an illustration of the lattice structure made of AlSi10Mg fabricated with the M290 PBF-LB machine from EOS (c).

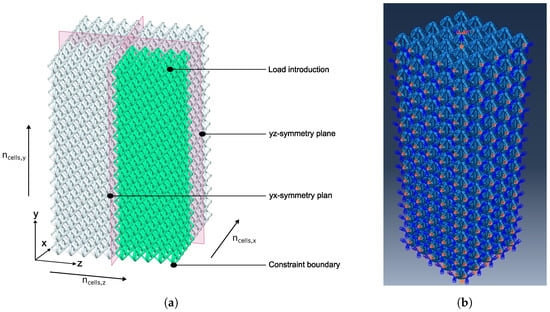

2.2. Finite Element Model

Generally speaking, the computational effort of cellular structures is higher compared to those with similar dimensions. This results from the three-dimensional periodic arrangement of the strut-based unit cells and the detailed discretization required for an accurate depiction of the state variables, especially in the intersection points of the struts. Hence, in order to minimize the computational effort, only one quarter of the finite element model is considered using symmetric boundary conditions. According to the schematic representation in Figure 2a, two planar surfaces positioned perpendicular to each other with respect to the and planes were utilized. The boundary conditions were defined according to the symmetry planes. This means that the for the plane, the displacements in the z direction and the rotation about the x and y axis were restrained, while for the plane, the displacements in the x direction and the rotation about the y and z axis were fixed. The load introduction was specified by a concentrated force which was distributed uniformly by means of kinematic coupling of the reference point to the selected surfaces, ensuring uniform motion while allowing the correct transfer of loads and boundary conditions. The model was discretized using three-dimensional C3D10 tetrahedral elements with quadratic shape functions to accurately determine the state variables and especially stress concentrations. The mesh element size was set to 0.18 times the strut diameter t, based on a convergence study described in the upcoming section. It was shown that the underlying mesh resolution allowed for an accurate depiction of both global and local stress maxima. Built upon the quasi-static finite element simulation, the fatigue analysis was equipped with a load time history in the form of a sinusoidal function which was implemented in fe-safe using a Python 3.8.8 script. The ten-point mean roughness values according to Table 1 were extracted through a detailed analysis of micrographs from several fabricated specimens. For the base material, the S-N curve of AlSi10Mg was used from the study by Strauss et al. [58]. Therein, the S-N curve was described by means of the nominal stress amplitude as

The basic load ratio was set to based on DIN 50100

The stress amplitude was defined as half of the difference between the maximum and minimum stress within one loading cycle. For the fatigue evaluation in fe-safe, nodal results of the state variables from the imported FEA in Abaqus were used. This approach ensured that the stress and strain states were transferred consistently at the nodes of the mesh, which were shared between adjacent elements. By relying on nodal data, the results maintain a smooth distribution across the model, avoiding discontinuities that might arise when using the values extracted from the integration points. This makes nodal results particularly suitable for fatigue analyses, where an accurate representation of local stress gradients is critical. Nonetheless, the nodal results are always compared to the values in the integration points in order to ensure that no significant deviation is observed.

Figure 2.

Subfig. (a) Schematic representation of the finite element model by the example of the f2ccz lattice structure. Subfig. (b) The force is distributed and introduced on the upper unit cells through a kinematic coupling and the nodes of the lattice structure on the bottom are solely constrained in the y direction with respect to their displacements.

Table 1.

Process parameters for the manufacturing of bcc and f2ccz lattice structures and the resulting equivalent strut diameter and surface roughness.

Table 1.

Process parameters for the manufacturing of bcc and f2ccz lattice structures and the resulting equivalent strut diameter and surface roughness.

| Unit Cell | in W | in mm/s | in m | in m |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bcc | 250 | 2500 | 373.67 | 49.54 |

| f2ccz | 250 | 2500 | 374.82 | 31.57 |

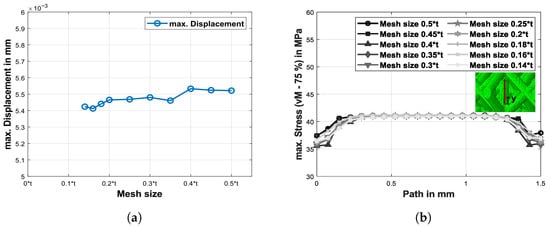

2.3. Convergence Study

In order to be able to assess the numerical results, a brief mesh refinement for the resulting three-dimensional displacement values and the von Mises stresses in an lattice structure undergoing a uniform compression loading should be discussed (see Figure 3). Herein, the element size has been parameterized and gradually decreased by means of the strut diameter t. Given the fact that in the intersection points of the struts, three-dimensional stress concentrations arose which converged towards infinity, the state variables were evaluated at a sufficient distance where these stress raisers had no further influence on the von Mises stress values. Figure 3a depicts the results for the considered displacement field. As is clearly evident, the maximum displacement values show great convergence behavior with slight variations in their results when comparing the highly detailed discretization scheme with the coarse mesh . For the maximum von Mises stresses, on the other hand, significant changes depending on the mesh size near the intersection points of the struts at 0 mm and 1.5 mm can be observed in Figure 3b. Especially at the nodal points of the strut, no convergence can be achieved, which is a result of the already mentioned stress concentration becoming apparent at these representative points of the lattice structure. Given the background that the vertical strut has a vertical length of 1.5 mm, it is important to note that at a distance of from those intersection points, the mesh size does not alter the maximum value of the von Mises stress. Hence, for the further finite element analyses, the mesh size will be fixed to since through further exhaustive studies it could be observed that the corresponding element size leads to the best compromise concerning the quality of the results and the computational efforts.

Figure 3.

Convergence study of the finite element model by the example of the f2ccz lattice structure. Subfig. (a) represents the maximum displacement values in mm for a specific element node at a sufficient distance from the intersection point of the struts, while subfig. (b) illustrates the convergence of the von Mises stress values along the path of the vertical strut of the f2ccz lattice structure with a total length of mm and .

3. Experimental Mechanical Testing

3.1. Material and Machine

The specimens were fabricated by using an M290 PBF-LB machine from EOS. The beam of the Yb-fiber laser had a diameter of 80 μm and was held constant for the investigation. Moreover, the commercially available powder material AlSi10Mg was used and the build plate temperature was defined at °C. The corresponding chemical composition and particle size distribution (PSD) according to [59] are summarized in Table 2. A single contour exposure was used based on the work by Grossman et al. [60] to achieve high-quality lattice structures. Therefore, the used laser power and scan speed were defined according to Table 1. Important factors for the fatigue performance like the equivalent strut diameter and surface roughness were evaluated with a gray-based MatLab algorithm through micrographs.

Table 2.

Properties of AlSi10Mg powder material according to [59].

3.2. Specimen Fabrication

The specimen design for the compression–compression fatigue test was defined according to the standardization ISO 13314 [61] for quasi-static compression testing. Therefore, the dimensions of the specimen were set to (Figure 1c) unit cells according to the x, y, and z directions in order to minimize size and edge effects. After the manufacturing process, the specimens were detached from the build plate, cleaned in an ultrasonic bath, and machined to achieve the right geometric dimensions and guarantee plane parallelism for the mechanical testing.

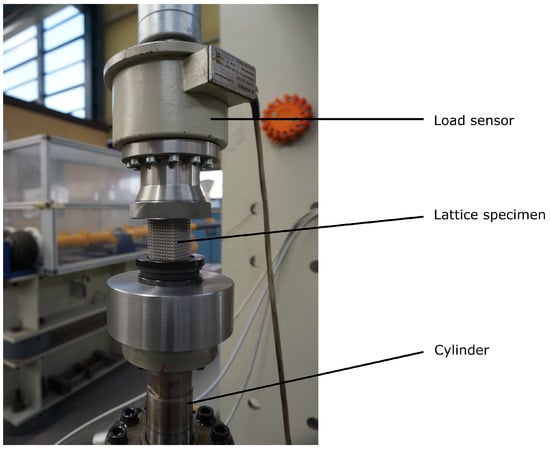

3.3. Compression–Compression Testing

The compression–compression tests were carried out on a servo-hydraulic testing machine from Schenk with a 16 kN cylinder and a swing range of ±20 mm. Furthermore, the load ratio was set to and was applied in a force-controlled manner according to the German guideline DIN 50100 [62]. Since there are no standardized guidelines for fatigue testing of cellular materials according to the test setup, procedure, and failure criteria, assumptions were made based on the German guideline DIN 50100 for fatigue testing of bulk material and data from the literature. The termination criterion for the experiment was defined based on the displacement of the test cylinder, thereby capturing the global failure of the lattice structures. The maximum allowable travel distance of the cylinder was set to the size of two unit cells. In order to guarantee no restriction of the transverse contraction at the nodal points of the load introduction, polished, hardened, and coated steel plates with lubrication were used for the testing. The test frequency was set to Hz and the possible heating of the test specimens was monitored using a thermal camera. Figure 4 illustrates the used experimental test setup.

Figure 4.

Experimental test setup for the compression–compression fatigue tests.

4. Discussion of Results

In this section, the numerical results of the considered lattice structures are investigated. The stress distribution in the representative unit cells is discussed in detail in order to connect the stress field as well as the stress concentrations in the intersecting points of the struts with the corresponding damage values. Furthermore, the influence of the unit cell topology, aspect ratio, mean stress, and mean stress correction models on the fatigue life is evaluated.

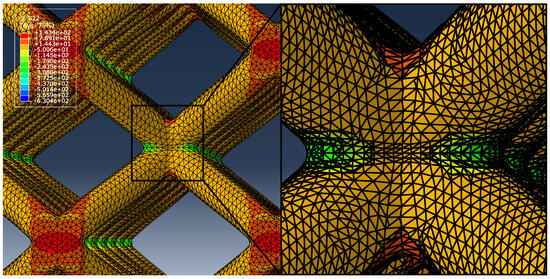

4.1. Stress Distribution of the Finite Element Model

Generally speaking, the failure for both representative unit cells is driven by tensile stresses in the nodal points of the lattice structure. Nonetheless, it should be kept in mind that a different mechanism can be observed for each unit cell that results in the overall failure of the considered lattice structure. The main reason for this stems from the vertical strut of the f2ccz unit cell which takes up the major part of the uniformly introduced compression and hence shows a higher stiffness compared to the bcc unit cell. This becomes evident when studying the normal stress distribution in the lattice structure during the finite element analysis (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Normal stress distribution of the bcc lattice structure with subjected to a quasi-static compressive loading in Abaqus.

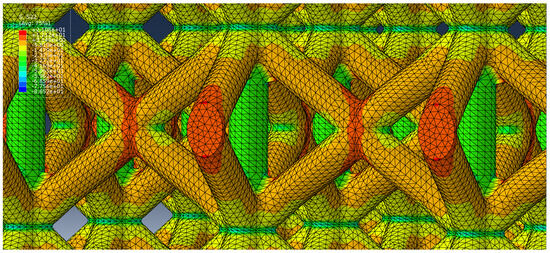

Figure 6.

Normal stress distribution of the f2ccz lattice structure with subjected to a quasi-static compressive loading in Abaqus.

Figure 5 illustrates the distribution of the normal stress component for the bcc lattice structure. Besides an expected uniform distribution in the struts, the nodal points especially show a variation from a compressive to a tensile stress state. This results from the introduced compression loading and the transverse contraction of the lattice structure. The overall uniform downward movement of the nodal points due to the compression introduces a bending moment which increases the angle between the plane and the respective struts. This, further on, leads to the already mentioned critical tensile stress state on the upper or rather lower part of the nodal points. At this point, it is also clear that the compressive stress state in the other two quadrants of the intersection points results from the reduction in the angle between the corresponding struts. Given the background of the normal stress distribution in the representative unit cells, it becomes apparent that the failure in the form of damage and cracks of the bcc lattice will be predominantly observed in the intersection points of the struts due to the underlying tensile stress concentrations. This will result in a breakage of the corresponding struts and thus to a load redistribution and higher stress levels in the adjacent unit cells, which most probably will also fail due to the load increase. This chain reaction that happens instantaneously has often been observed in experimental studies wherein the lattice structure completely fails all of a sudden without any signs due to the compression loading.

As already pointed out, this is quite different from the failure modes observed in the f2ccz lattice structures, which can also be assessed by investigating the respective finite element analysis (see Figure 6). Concerning the diagonal struts as well as the intersection points, similar characteristics as in the bcc unit cells are observed. However, since the loading direction is identical to the orientation of the vertical struts, a compressive stress state is present in those. Hence, it is expected that the failure of the f2ccz lattice structure is a combination of beam buckling at different locations of the vertical struts and breakage of the intersections in the respective nodes. However, it is not possible to capture the exact location of the initial failure in both lattice structures by virtue of the considered finite element model since it very much depends on the fabrication quality during the PBF-LB process which is known to lead to imperfections, pores, and deviations from the actual design geometry. In order to accurately compute the stress field and have a detailed assessment of the failure of the lattice structures, -CT scans of every specimen have to be conducted, which, however, not only increase the preparation time of the model significantly but also the computational effort.

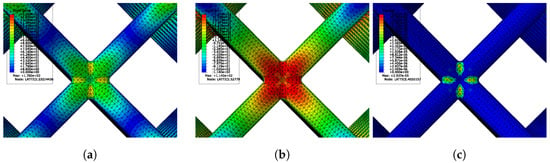

4.2. Fatigue Life Prediction

The fatigue life prediction results are directly affected by the stress distribution of the linear elastic calculations presented in Section 4.1. According to the utilized load ratio R, local mean stress distributions and stress amplitudes arise mainly based on the unit cell topology. Thus, the employed aspect ratio only changes the stress value, while the local distribution remains the same. Therefore, is used as a representative description of the mechanical behavior of the bcc and f2ccz lattice structure under compression–compression loading. The first important factor to look at is the local distribution of the cycle stress amplitude. The highest stress values of 176 MPa for the bcc unit cell are located in the nodal region, while in the struts only low stress amplitude values are detected (Figure 7a). These results are in line with the findings in Section 4.1. Hereby, the highest stresses are located at the top and bottom section of the nodal region, located at the stress concentrations based on the notch effect. These elevated local amplitude values are of particular concern, as they indicate regions subjected to significant cyclic loading, which are more prone to fatigue crack initiation and failure. The second factor is the local mean stress distribution among the lattice structure. While the local stress amplitude distribution showcases the amount of local stress fluctuation, the mean stress distribution defines the direction of the local stress. Hereby, positive values indicate tensile mean stresses, which are generally detrimental to fatigue performance, as they effectively reduce the fatigue life and induce cracks. On the other hand, negative values represent compressive mean stresses which enhance fatigue life by closing cracks and reducing crack propagation. The deformation behavior based on induced bending moments of the bcc lattice structure leads to fatigue-critical tensile mean stresses of 114 MPa in the top and bottom regions of the nodal region, which defines the fatigue-critical region for fatigue crack initiation, as shown in Figure 7b. Looking at the highest resulting damage values (Figure 7c), they also occur at the location of the highest positive mean stress. According to linear damage accumulation, the node that exhibits the highest damage per cycle is predicted to fail first, thereby identifying the fatigue-critical region of the structure. In the case of the f2ccz lattice structure, the results of the local mean stress as well as the local stress distribution are in line with the stress distribution results from Section 4.1. The distribution of the local cyclic stress amplitude demonstrates that the vertical struts and the nodal regions are predominantly subjected to compression loading, whereas the diagonal struts exhibit negligible stress levels. Examination of the mean stress field further reveals compressive mean stresses within the vertical struts, while in the nodal regions, analogous to the bcc lattice structure, both tensile and compressive mean stresses are observed. Hence, a similar failure behavior as observed under quasi-static loading can be expected under fatigue loading.

Figure 7.

Numerical results of bcc for . Subfig. (a) represents the local stress amplitude, subfig. (b) the mean stress distribution and direction, and subfig. (c) the damage value distribution.

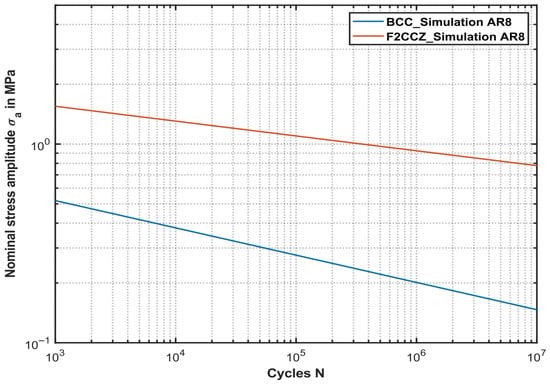

In order to assess the fatigue performance of each structure configuration, S-N curves were derived. Therefore, the fatigue life of the structure was predicted by the expressed numerical simulations by means of at least four different nominal stress amplitudes. The S-N curve is linear in the logarithmic scale and was consequently described in a power-law equation, according to the guideline DIN 50100:

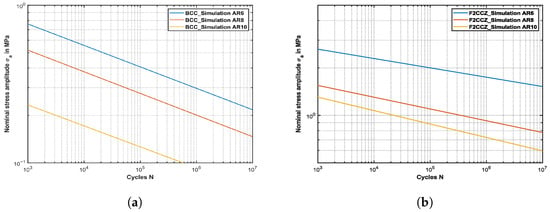

The fatigue life at a given constant stress amplitude corresponds to a cumulative damage value of , which is calculated according to the linear damage accumulation model. The model assumes that the damage accumulated during cyclic loading progresses continuously from the onset of microstructural degradation to the final fracture. Consequently, the numerically obtained N values used in the construction of the S-N curve represent the entire fatigue life until failure, without distinguishing between initiation and propagation phases. Hereby, it is found that the fatigue life of the lattice structures rapidly decreases with increasing stress amplitude, which is generally in agreement with the obtained experimental results and data from the literature [30,63]. Figure 8 shows a comparison of the two examined unit cells for . For the same , the bcc lattice structure indicates a much lower fatigue strength and general performance based on the inclination value k, which is depicted in Table 3. This can be explained by the fact described in Section 4.1 that through compression loading bending moments are introduced in the structure, which lead to local tension and compression stresses. Hereby, the tensile stresses are detrimental for the structures and lead to a reduced fatigue performance compared to the stretch-dominated f2ccz lattice structure, where the axial compression load is mainly transferred by the vertical struts. In the case of compression–compression loading, the f2ccz lattice structure exhibits superior fatigue performance, making it particularly suitable for applications requiring enhanced fatigue strength.

Figure 8.

Comparison of the numerical results in the form of S-N curves of the bcc and f2ccz lattice structures.

4.3. Influence of the Aspect Ratio

The chosen aspect ratio strongly influences the mechanical behavior and performance of lattice structures, as demonstrated by various authors through studies of relative density variations [11,30,44,64]. Using the aspect ratio offers the advantage that all examined lattice structures share the same strut diameter. In contrast, applying the same relative density results in different strut diameters, depending on the unit cell topology and the number of struts within each unit cell. Therefore, the influence of the aspect ratio on the fatigue life prediction of bcc and f2ccz is considered in this section. Figure 9a,b demonstrate the S-N curves for the aspect ratios , and 10. The unit cell length a is kept constant while the diameter of the strut t varies. Both unit cells show the same fatigue response to an increasing or decreasing aspect ratio. Decreasing the aspect ratio leads to an upward shift in the S-N curve while maintaining almost the same inclination. Small deviations in the inclination values can be referred to simulation inaccuracies. This phenomenon reflects an increase in the maximum sustainable stress for a given fatigue life, without altering the underlying fatigue mechanism. These findings are in line with the finding in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, and [63,65,66], where, in general, the unit cell topology defines the resulting stress distribution and mechanical response of the lattice structure. In contrast, the aspect ratio changes the stiffness, the peak values of the local stresses, and the effect of the notch effect through changing the cross-sectional area of load-bearing struts. For example, the maximum local cyclic tensile stress amplitude of the bcc lattice structure is reduced by 27.9% between and , which enhances the fatigue performance. This is the reason why changing the aspect ratio simply leads to higher fatigue performance concerning the stress amplitude and allows tailoring of the mechanical behavior under cyclic loading through adapting the strut diameter or unit cell length. These findings suggest that lattice topology and relative density can be strategically designed to enhance fatigue strength without fundamentally altering the fatigue response, providing a robust tool for optimizing lightweight structural components in engineering applications.

Figure 9.

S-N curves for different aspect ratios of bcc and f2ccz lattice structures. Subfig. (a) represents the S-N curves depending on the aspect ratio for bcc, while subfig. (b) illustrates the S-N curves of the f2ccz lattice structure.

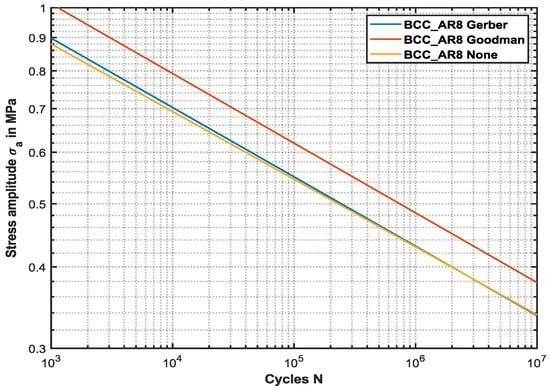

4.4. Mean Stress Influence and Correction

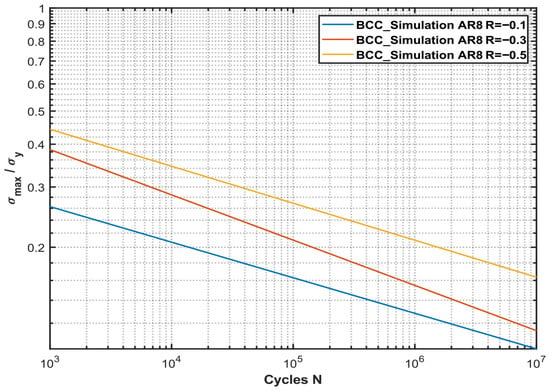

The results in Section 4.2 indicate the detrimental influence of mean stresses on the fatigue performance of the lattice structures. The scientific literature only shows a small number of experimental investigations on the effect of mean stress on the fatigue behavior of lattice structures. The main compression–compression investigations are based on a load ratio . In order to address this issue, numerical simulations with three different load ratios are carried out and the results are compared. In the case of comparability, the bcc lattice structure with and the load ratios , , and are used. Therefore, the maximum predefined load is kept constant and only the implemented time history for the simulations is adjusted according to the desired load ratio. Figure 10 illustrates the influence of the load ratio for the same values of normalized stress (max. applied stress/yield stress).

Figure 10.

Normalized stress vs. number of cycles to failure for different load ratios for a bcc lattice structure with .

Hereby, higher load ratios lead to a greater number of cycles to failure, which is expected since for any given maximum stress, the stress amplitude decreases with increasing R value. The shifting of the S-N curves upwards is the result of lower stress amplitudes experienced for higher stresses. In the observed inclination of the S-N curves with different load ratios, no real trend is identified. Hereby, and showcase similar inclinations while is identified with a steeper incline. Based on the work of Krijger et al. [64] on Ti-6Al-4V diamond lattice structures, a reduction in the S-N curve inclination is expected at higher load ratios, since the bcc lattice structure features similar strut angles as the diamond unit cell. In experimental investigations, the influence of the base material is expected to be more pronounced; however, in the present simulations, ideal isotropic material properties are assumed. Consequently, the absence of a reduction in the inclination with increasing R values is likely attributable to simulation limitations rather than material behavior. Future experimental work is therefore necessary to validate this assumption. Plotting the number of cycles normalized against the stress amplitude results in a single trend regardless of the applied stress amplitude, as shown in Figure 11.

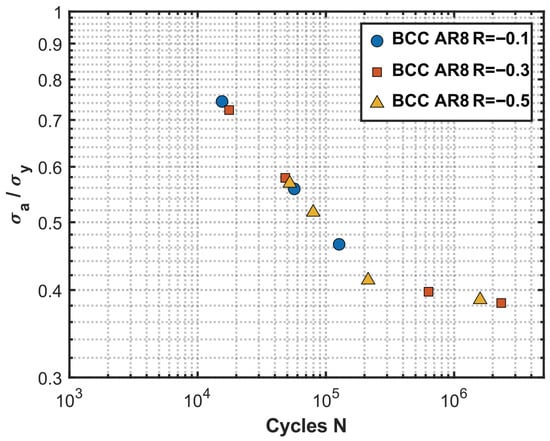

Figure 11.

Normalized stress amplitude vs. number of cycles to failure for different load ratios for a bcc lattice structure with .

This behavior clearly demonstrates that the applied stress amplitude is the dominant factor when determining the S-N curves for strut-based lattice structures. This is supported by (5), which describes a power-law dependence of fatigue life on stress amplitude. The stress amplitude is the primary parameter influencing fatigue life, with mean stress as a secondary parameter.

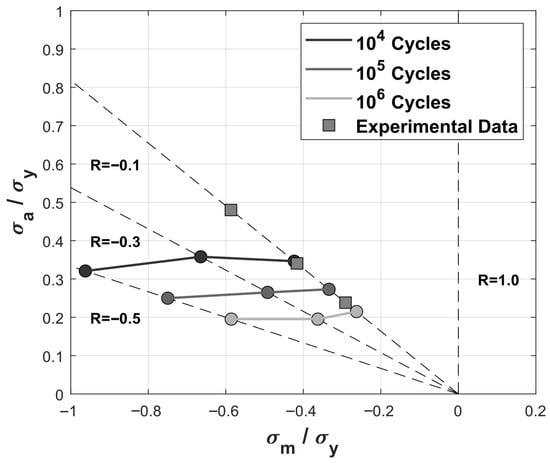

The Haigh diagram is a typical way to visualize constant fatigue life values depending on the deployed mean stress. Hereby, the stress amplitude as well as the mean stress is normalized by the yield stress , as shown in Figure 12. With increasing normalized mean stress, the normalized stress amplitude corresponding to cycles exhibits a slight decrease between and while it is almost constant between and . Moreover, and cycles show only a slight decrease in the normalized stress amplitude with increasing normalized mean stress. The experimental results depict a slight underestimation for all examined cycles. In general, increasing values in mean stress do not result in a strongly noticeable decline in the stress amplitude for constant fatigue life, which indicates a minor sensitivity to mean stresses. In contrast, the fatigue behavior of bulk material indicates a strong sensitivity to mean stresses depending on the material properties, as shown by [64] for Ti-6Al-4V. Furthermore, Strauss et al. [58] showed a clear dependence and decline in fatigue life with increasing mean stress for AlSi10Mg bulk material manufactured by PBF-LB technology. This behavior is commonly captured using classical mean stress correction models, such as Goodman, Gerber, or Soderberg. These models are typically used to predict fatigue life under non-zero mean stresses by adjusting the allowable stress amplitude. However, in the case of compression–compression loading, the influence of the mean stress is relatively small. Consequently, the fatigue response of the lattice structures can differ markedly from that of the bulk material. In particular, the load ratio effect observed in lattice structures does not consistently follow the trends predicted by these classical models, suggesting that geometrical factors such as strut orientation, node connectivity, and local stress concentrations play a more dominant role than the mean stress itself. The results of the mean stress correction models Goodman and Gerber are exemplary compared to the S-N curve without mean stress correction in Figure 13. The Goodman model accounts for mean stress sensitivity through a linear interaction between stress amplitude and mean stress, and is therefore able to display a noticeable mean stress influence, as discussed in Figure 12. In contrast, the Gerber model, based on a parabolic relationship, is not able to display the mean stress influence. In bulk materials, notched specimens exhibit a reduced fatigue strength compared to unnotched specimens, while simultaneously showing a lower sensitivity to mean stress effects [67]. Lattice structures can be regarded as inherently notched specimens due to the geometrically induced stress concentrations in the nodal regions, as discussed in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2. Furthermore, the reduced mean stress sensitivity is mainly because of the fact, that even under global compression loading, local tensile stresses occur within the lattice structure (Figure 5) which are detrimental for the fatigue life. Consequently, the beneficial influence of compressive stresses, namely the crack-closure effect observed in bulk materials, is largely diminished due to the geometric complexity of the lattice. This is why, in lattice structures, the mean stress is primarily determined by the absolute stress values, while local tensile stresses can arise independently of the overall mean stress. In addition, the simulations considered the surface roughness values obtained in the experiments. Surface roughness acts as a local stress concentrator and thereby reduces fatigue performance, since roughness-induced features can serve as crack initiation sites. Therefore, process and parameter optimizations are required to minimize surface roughness and inherent defects, thus improving the fatigue performance of lattice structures.

Figure 12.

Haigh diagram constructed from the numerical results of bcc lattice structures with . Constant fatigue life displayed for , , and cycles.

Figure 13.

Influence of the mean stress correction models Goodman and Gerber on the fatigue life.

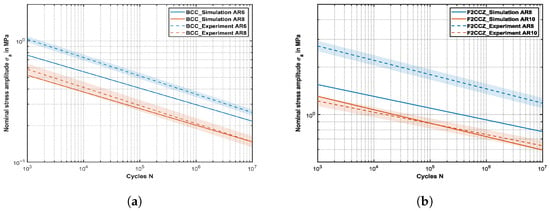

4.5. Experimental Data Evaluation

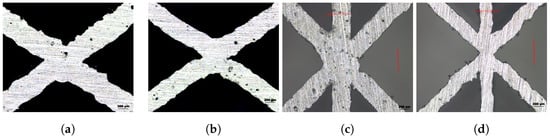

The validation of the numerical results is achieved by comparison with the experimental data. Therefore, the bcc lattice structures are compared with the experimental results for and while and are used for the f2ccz lattice structure. Figure 14 illustrates the corresponding S-N curves. In general, a certain deviation between numerical and experimental results can be observed and is expected, based on the assumptions made for the numerical model. The numerically generated S-N curves show a very good agreement on the inclination value of the S-N curves. Table 3 depicts the inclination values k determined by the FE-based simulations and the values extracted from the experiments, depending on the used value. The k values for the bcc lattice structures vary in a very small range between and , while the experimental results show inclinations between and . Hereby, the absolute error between the simulation and experiment stays almost constant with changing . When comparing the fatigue strength at cycles, the deviation between numerical and experimental results increases with increasing strut diameter from to , while the inclination deviation remains almost the same. The underestimation of with increasing strut diameter can be attributed to deviations between the as-built state and idealized geometry of the numerical model. While process-induced geometrical deviations, like strut waviness, affect the inclination of the S-N curve of the structure [11], the material distribution in the nodal region strongly affects the stiffness and resulting fatigue strength of the structure. Lozanovski et al. [51,68,69] showed in their investigations that the intersection of the struts in the nodal region led to significant changes in stiffness. Hereby, in stretch-dominated lattice structures, the elastic behavior is governed mainly by the axially weakest sections of the struts. Consequently, a local increase in strut diameter at the nodes has only a limited influence on the global stiffness of the structure, in contrast to bending-dominated structures, where such geometric variations have a more pronounced effect. Furthermore, the intentionally designed notch at the strut intersections significantly alters the local stress distribution and, consequently, has a substantial impact on the predicted fatigue life. Figure 15 depicts the nodal region of the as-built state of the manufactured lattice structures. Figure 15 clearly shows the reduction in the designed notch in the intersection point for both investigated unit cells with increasing strut diameter. The observed notches for in the bcc lattice and in the f2ccz lattice are much closer to the as-designed geometry used in the numerical model. This characteristic appears to be the main factor contributing to the underestimation of fatigue performance with increasing strut diameter, as smoother transitions between differently angled struts reduce local stress concentrations.

Figure 14.

Comparison of simulated and experimental S-N curves for different aspect ratios of bcc and f2ccz lattice structures. Subfig. (a) represents the comparison of S-N curves depending on the aspect ratio for bcc, while subfig. (b) illustrates the comparison of the S-N curves of the f2ccz lattice structure.

Figure 15.

Micrographs of the nodal region of a bcc lattice structure. Subfigure (a) is and (b) is , and for a f2ccz unit cell, subfigure (c) is and (d) is .

Table 3.

Comparison between the numerical and experimental results of the inclination k and the fatigue strength at for bcc and f2ccz lattice structures, depending on the aspect ratio.

Table 3.

Comparison between the numerical and experimental results of the inclination k and the fatigue strength at for bcc and f2ccz lattice structures, depending on the aspect ratio.

| bcc | f2ccz | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AR | Sim. | Exp. | Error | Sim. | Exp. | Error | |

| 6 | k | −0.136 | −0.151 | −9.93% | −0.059 | - | - |

| [MPa] | 0.297 | 0.363 | −18.18% | 1.748 | - | - | |

| 8 | k | −0.137 | −0.150 | −8.67% | −0.075 | −0.091 | −17.58% |

| [MPa] | 0.201 | 0.207 | −2.90% | 0.925 | 1.456 | −36.47% | |

| 10 | k | −0.133 | - | - | −0.085 | −0.071 | 19.72% |

| [MPa] | 0.093 | - | - | 0.725 | 0.747 | −2.95% | |

The comparison of the results for the f2ccz lattice structure showcases greater deviations between the numerical and experimental results. Moreover, no clear deviation trend is detectable on the basis of the absolute error values. The inclination values obtained from the numerical analysis range between and , whereas the experimental results exhibit a variation between and . For , the predicted fatigue strength shows very good agreement between the finite element model and the experiments. However, with increasing strut diameter, the deviations systematically increase, resulting in an underestimation of up to 36.47%. The larger deviations in the f2ccz compared to the bcc lattice structure are expected based on the unit cell topology. As shown in Section 4.1 and Section 4.2, the mechanical performance of f2ccz is highly dependent on the vertical strut in the case of compression loading. Small deviations in strut angle and diameter introduced by the PBF-LB manufacturing process result in measurable variations in the mechanical response of the structure, which is also depicted by the higher deviation in k in the experimental results. Moreover, considering the failure mechanism involving a combination of beam buckling and fracture at the intersection nodes, the structure exhibits enhanced damage tolerance. This can be attributed to the ability of the remaining vertical struts to partially compensate for the failure of an individual vertical strut. In the case of the bcc lattice structures, failure of the first strut in the nodal region due to crack propagation leads to a chain reaction inside the structure that leads to a sudden failure of the structure. Furthermore, variations in strut diameter arise from the inclination angle relative to the building direction, which induces the stair-step effect. In addition, the use of a single contour exposure results in an elliptical melt track in the diagonal struts, further increasing their thickness compared to the vertical struts of f2ccz. This fact explains the higher values of the experimental dimensions of the nodal regions since the diagonal and vertical strut meet at this intersection point. Although inclined struts deform only marginally under compressive load, they suppress vertical strut buckling and thus increase structural stability and fatigue performance, which is also shown in [70]. Furthermore, the nodal point between two unit cells, where no vertical strut is present, results in thicker intersections based on the thicker diagonal struts from the manufacturing process. The additional material increases the stiffness and fatigue tolerance in this region, where detrimental tensile stresses are presented as shown in Figure 6, which enhances the underestimation of the numerical model. Moreover, different microstructure patterns have been observed inside lattice structures on the basis of changing thermal gradients during the printing process. The microstructure as well as the grain orientation have an influence on the mechanical properties. Lui et al. [71] showed that a gradient microstructure was present at the node and strut portions of the lattice specimen. These local variations cannot be displayed by the presented numerical model and further experimental investigations need to be carried out to detect the actual influence on the fatigue performance of lattice structures. Additionally, residual stresses are introduced in metal additive manufacturing through rapid localized melting and solidification caused by the fast-moving laser. These stresses can be either tensile or compressive and tend to develop unevenly throughout the component. Predicting their magnitude and distribution becomes especially challenging in parts with complex geometries, since traditional measurements are mostly not possible [11]. Dallago et al. [72] used the FIB-SEM-DIC micro-hole drilling method and showed compressive and tensile residual stresses in the strut and nodal regions of a lattice structure. Hereby, the unit cell topology primarily affects the heat dissipation during the manufacturing process as well as the strut diameter. That is the reason why different residual stresses can be expected in the as-built state of the bcc and f2ccz. The bcc lattice is expected to be more affected than the f2ccz structure, as it contains one fewer strut and lacks a direct connection to the build plate, which influences the heat dissipation. The influence of strut diameter on residual stresses can be inferred from the fact that thicker struts conduct excess heat more efficiently toward the build plate, while thinner struts, due to their smaller volume, tend to accumulate less heat. Further investigations need to be carried out and reliable measurements of residual stresses for thin-walled lattice structures need to be developed in order to quantify their impact on the fatigue performance.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The numerical FE model was developed in order to predict the fatigue life of AlSi10Mg strut-based lattice structures under compression–compression loading. Therefore, the quasi-static stress distribution as a function of unit cell topology was analyzed, along with the local distributions of mean stress and stress amplitude. Tensile stresses in the nodal region for bcc lattice structures were identified as failure regions, while for the f2ccz lattice structure, initial buckling of vertical struts was expected. The simulation results indicated that the relationship between the number of cycles to failure and the fatigue strength (S-N curve) followed a power-law behavior which was in line with the experimental results. The numerical model was found to predict the fatigue strength at cycles with only small deviations for higher aspect ratios, while yielding conservative estimates for smaller aspect ratios that are favorable for industrial implementation. These deviations stem from the modeling assumptions, which do not capture the actual reduction in the notch effect with increasing strut diameter, nor the influence of manufacturing-induced factors such as residual stresses, porosity, microstructure, and geometric imperfections. Nevertheless, the influence of relative density, represented in this study by the aspect ratio, was accurately reflected by the simulations, as the experimental results revealed only an upward shift in the S-N curve at lower aspect ratios while maintaining a constant inclination. The mean stress influence was studied through numerical simulations by varying the R ratio. The derived constant life diagram indicated a minor influence of the mean stress in the compression region. This response stands in sharp contrast to the behavior typically observed in bulk alloys. Consequently, additively manufactured porous structures exhibit a fatigue performance that differs not only in magnitude but also in nature from that of solid materials, particularly regarding their R ratio dependence. As a result, classical mean stress correction models, which are widely used in the design of conventional materials, cannot be directly applied to lattice structures. Instead, novel fatigue design methodologies tailored to these novel structures are required.

The proposed numerical framework demonstrates the potential of a simplified modeling approach, which could be further validated by incorporating alternative unit cell topologies and extended to plate- and sheet-based lattice structures. While the current model only accounts for process-induced surface roughness, future work must incorporate residual stresses and material anisotropy to improve fatigue life predictions, as these have a detrimental effect on the fatigue behavior. -CT scans enable capturing of the actual geometry of the lattice structure, and a corresponding finite element model can provide insights into the magnitude of the effects arising from differences between the idealized and the real geometry. This facilitates the identification of key features for the idealized model, reducing the need for extensive -CT scanning and thereby significantly improving computational efficiency. Therefore, different post-heat treatments should be conducted to reduce residual stresses. Simultaneous experimental testing is needed to further validate numerical results across different base materials, load ratios, relative densities, and unit cell topologies, as current datasets are sparse and often lack sufficient detail for meaningful comparison.

Author Contributions

M.G.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, and Visualization. A.K.: Writing—Original Draft, Methodology, Validation, and Formal Analysis. M.R.: Investigation. C.M.: Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, and Project Administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported within the project AddLight (03LB2009C) by the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) and the project supervised by the Projektträger Jülich (PtJ).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Jiang, C.P.; Masrurotin; Wibisono, A.T.; Macek, W.; Ramezani, M. Enhancing Internal Cooling Channel Design in Inconel 718 Turbine Blades via Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A Comprehensive Review of Surface Topography Enhancements. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2025, 26, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehly, C.; Neuberger, H.; Bühler, L. Fabrication of thin-walled fusion blanket components like flow channel inserts by selective laser melting. Fusion Eng. Des. 2019, 143, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onder, M.E.; Culhaoglu, A.; Ozgul, O.; Tekin, U.; Atıl, F.; Taze, C.; Yasa, E. Biomimetic dental implant production using selective laser powder bed fusion melting: In-vitro results. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2024, 151, 106360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spickler, B.; Gray, J.; Nicolaisen, D.; Schiefelbein, B.; Depcik, C. Surface roughness and dimensional evaluation of laser powder bed fusion additively manufactured shell and tube heat exchangers. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 65, 103858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, M.; Bodemer, J.; Kabelac, S. Experimental investigation of additively manufactured high-temperature heat exchangers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 218, 124774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.; Yadroitsava, I.; Yadroitsev, I.; Le Roux, S.G.; Blaine, D.C. Numerical comparison of lattice unit cell designs for medical implants by additive manufacturing. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2018, 13, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Y.; Liu, J. Study on fatigue crack initiation behavior of two types of lattice structures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 3009, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lei, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, H.; Wang, P.; Fang, D. Architecture design of periodic truss-lattice cells for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 34, 101172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.; Großmann, A.; Mittelstedt, C. Micromechanical analysis of the effective properties of lattice structures in additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 23, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M.; Mazur, M.; Elambasseril, J.; McMillan, M.; Chirent, T.; Sun, Y.; Qian, M.; Easton, M.; Brandt, M. Selective laser melting (SLM) of AlSi12Mg lattice structures. Mater. Des. 2016, 98, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Du Plessis, A.; Ritchie, R.O.; Dallago, M.; Razavi, N.; Berto, F. Architected cellular materials: A review on their mechanical properties towards fatigue-tolerant design and fabrication. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2021, 144, 100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F. Cellular Solids: Structure and Properties, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tankasala, H.C.; Deshpande, V.S.; Fleck, N.A. Tensile response of elastoplastic lattices at finite strain. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2017, 109, 307–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, N.A.; Deshpande, V.S.; Ashby, M.F. Micro-architectured materials: Past, present and future. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2010, 466, 2495–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarian, A.; Esfahanian, M.; Kadkhodapour, J.; Ziaei-Rad, S. Effect of solid distribution on elastic properties of open-cell cellular solids using numerical and experimental methods. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014, 37, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomar, Z.; Concli, F. A Review of the Selective Laser Melting Lattice Structures and Their Numerical Models. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, Y.F. A Survey of Modeling of Lattice Structures Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing. J. Mech. Des. 2017, 139, 100906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuadrado, A.; Yánez, A.; Martel, O.; Deviaene, S.; Monopoli, D. Influence of load orientation and of types of loads on the mechanical properties of porous Ti6Al4V biomaterials. Mater. Des. 2017, 135, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadkhodapour, J.; Montazerian, H.; Darabi, A.C.; Anaraki, A.P.; Ahmadi, S.M.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Schmauder, S. Failure mechanisms of additively manufactured porous biomaterials: Effects of porosity and type of unit cell. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 50, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Fang, J.; Wu, C.; Li, C.; Sun, G.; Li, Q. Additively manufactured materials and structures: A state-of-the-art review on their mechanical characteristics and energy absorption. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 246, 108102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Martínez, C.; Piedra, S.; Perez-Barrera, J.; González-Carmona, J.M.; Franco Urquiza, E.A.; Gómez-Ortega, A. Lightweighting and performance analysis of a spur gear by implementing cellular structures and additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 2291–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarian, A.; Esfahanian, M.; Kadkhodapour, J.; Ziaei-Rad, S. Numerical simulation of the fatigue behavior of additive manufactured titanium porous lattice structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 60, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, E.; Cerri, E. Work Hardening of Heat-Treated AlSi10Mg Alloy Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting: Effects of Layer Thickness and Hatch Spacing. Materials 2021, 14, 4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Riccio, A. A systematic review of design for additive manufacturing of aerospace lattice structures: Current trends and future directions. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2024, 149, 101021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DebRoy, T.; Wei, H.L.; Zuback, J.S.; Mukherjee, T.; Elmer, J.W.; Milewski, J.O.; Beese, A.M.; Wilson-Heid, A.; De, A.; Zhang, W. Additive manufacturing of metallic components—Process, structure and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 92, 112–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.L.; Li, X. An overview of residual stresses in metal powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, P.; Silva, M.B.; Moita de Deus, A.; Cláudio, R.; Carmezim, M.; Santos, C.; Magrinho, J.; Reis, L.; Lino, J.; Oliveira, L.; et al. Evaluation of the roughness of lattice structures of AISI 316 stainless steel produced by laser powder bed fusion. Eng. Manuf. Lett. 2024, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarik Hasib, M.; Ostergaard, H.E.; Li, X.; Kruzic, J.J. Fatigue crack growth behavior of laser powder bed fusion additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V: Roles of post heat treatment and build orientation. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 142, 105955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murchio, S.; Dallago, M.; Rigatti, A.; Luchin, V.; Berto, F.; Maniglio, D.; Benedetti, M. On the effect of the node and building orientation on the fatigue behavior of L–PBF Ti6Al4V lattice structure sub–unital elements. Mater. Des. Process. Commun. 2021, 3, e258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Tvenning, T.; Wu, T.; Razavi, N. Evaluating quasi-static and fatigue performance of IN718 gyroid lattice structures fabricated via LPBF: Exploring relative densities. Int. J. Fatigue 2024, 178, 108028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soro, N.; Saintier, N.; Merzeau, J.; Veidt, M.; Dargusch, M.S. Quasi-static and fatigue properties of graded Ti–6Al–4V lattices produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion (LPBF). Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, A.; Razavi, N.; Berto, F. The effects of microporosity in struts of gyroid lattice structures produced by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.M.; Vaghefi, E.; Mirkoohi, E. The role of defect structure and residual stress on fatigue failure mechanisms of Ti-6Al-4V manufactured via laser powder bed fusion: Effect of process parameters and geometrical factors. J. Manuf. Processes 2023, 102, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, G.; Carraturo, M.; Korshunova, N.; Kollmannsberger, S. Numerical evaluation of high cycle fatigue life for additively manufactured stainless steel 316L lattice structures: Preliminary considerations. Mater. Des. Process. Commun. 2021, 3, e249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.M.; Hedayati, R.; Li, Y.; Lietaert, K.; Tümer, N.; Fatemi, A.; Rans, C.D.; Pouran, B.; Weinans, H.; Zadpoor, A.A. Fatigue performance of additively manufactured meta-biomaterials: The effects of topology and material type. Acta Biomater. 2018, 65, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, A.; van Hooreweder, B. Fatigue behaviour of diamond based Ti-6Al-4V lattice structures produced by laser powder bed fusion: On the effect of load direction. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Tang, D.; Dang, L.; Gao, L.; Yang, Z.; Wu, B.; He, X.; Zhan, Z. Fatigue failure mechanisms and life prediction of additive manufactured metallic lattices: A comprehensive review. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2451124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, B.; Tang, X.; Zhang, D.; Dai, Y.; Lin, J.; Tong, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, J.; Wen, C. Compression fatigue behavior of gyroid porous titanium scaffolds manufactured by laser powder bed fusion for bone-implant applications. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 201, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parameswaran, P.; Kesavan, D.; Jayaganthan, R. High-cycle fatigue analysis in dumbbell-shaped lattice structure of Ti6Al4V through additive manufacturing: Experimental and numerical simulation. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 40, 1838–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, D.; Voshage, M.; Burkamp, K.; Kunz, J.; Bezold, A.; Schleifenbaum, J.H.; Broeckmann, C. Mechanical behaviour of additive manufactured 316L f2ccz lattice structure under static and cyclic loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, C.; Mohr, D. Large deformation response of additively-manufactured FCC metamaterials: From octet truss lattices towards continuous shell mesostructures. Int. J. Plast. 2017, 92, 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerappan, S. Finite Element-Based Modeling of Stress Distribution in 3D-Printed Lattice Structures. J. Appl. Math. Model. Eng. 2025, 1, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kamranfard, M.R.; Darijani, H.; Rokhgireh, H.; Khademzadeh, S. Analysis and optimization of strut-based lattice structures by simplified finite element method. Acta Mech. 2023, 234, 1381–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Tran, P.; Nguyen-Xuan, H.; Ferreira, A. Mechanical performance and fatigue life prediction of lattice structures: Parametric computational approach. Compos. Struct. 2020, 235, 111821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boniotti, L.; Dancette, S.; Gavazzoni, M.; Lachambre, J.; Buffiere, J.Y.; Foletti, S. Experimental and numerical investigation on fatigue damage in micro-lattice materials by Digital Volume Correlation and μCT-based finite element models. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 266, 108370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Attallah, M.M.; Coules, H.; Martinez, R.; Pavier, M. Fatigue of octet-truss lattices manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 170, 107524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Biasi, R.; Yasin, M.S.; Perini, M.; Benedetti, M.; Berto, F. Compensated beam model for efficient and accurate FE elastic simulation of strut-based lattice structures. Mater. Des. 2025, 255, 114213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Biasi, R.; Oztoprak, O.; Zanini, F.; Carmignato, S.; Kollmannsberger, S.; Benedetti, M. Predicting fatigue life of additively manufactured lattice structures using the image-based Finite Cell Method and average strain energy density. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargarian, A.; Esfahanian, M.; Kadkhodapour, J.; Ziaei-Rad, S.; Zamani, D. On the fatigue behavior of additive manufactured lattice structures. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2019, 100, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, A.; Persenot, T.; Doutre, P.T.; Buffiere, J.Y.; Lhuissier, P.; Martin, G.; Dendievel, R. A numerical framework to predict the fatigue life of lattice structures built by additive manufacturing. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 139, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovski, B.; Leary, M.; Tran, P.; Shidid, D.; Qian, M.; Choong, P.; Brandt, M. Computational modelling of strut defects in SLM manufactured lattice structures. Mater. Des. 2019, 171, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.; Pantidis, P.; Bertoldi, K.; Gerasimidis, S. Correlation between topology and elastic properties of imperfect truss-lattice materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2019, 124, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, R.; Hosseini-Toudeshky, H.; Sadighi, M.; Mohammadi-Aghdam, M.; Zadpoor, A.A. Computational prediction of the fatigue behavior of additively manufactured porous metallic biomaterials. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 84, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, F.; Temizer, I. Computational homogenization of fatigue in additively manufactured microlattice structures. Comput. Mech. 2023, 71, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molavitabrizi, D.; Ekberg, A.; Mousavi, S.M. Computational model for low cycle fatigue analysis of lattice materials: Incorporating theory of critical distance with elastoplastic homogenization. Eur. J. Mech.-A/Solids 2022, 92, 104480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coluccia, A.; de Pasquale, G. Strain-based method for fatigue failure prediction of additively manufactured lattice structures. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, G.; Curtarello, A.; Rosso, S.; Meneghello, R.; Concheri, G. Homogenization driven design of lightweight structures for additive manufacturing. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM 2019, 13, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauß, L.; Löwisch, G. Prediction of fatigue lifetime and fatigue limit of aluminum parts produced by PBF-LB/M using a statistical defect distribution. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EOS Aluminium AlSi10Mg—Material Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.eos.info/var/assets/03_system-related-assets/material-related-contents/metal-materials-and-examples/metal-material-datasheet/aluminium/material_datasheet_eos_aluminium-alsi10mg_en_web.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Großmann, A.; Gosmann, J.; Mittelstedt, C. Lightweight lattice structures in selective laser melting: Design, fabrication and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 766, 138356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13314:2011; Mechanical Testing of Metals—Ductility Testing—Compression Test for Porous and Cellular Metals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- DIN 50100; Schwingfestigkeitsversuch—Durchführung und Auswertung von Zyklischen Versuchen mit Konstanter Lastamplitude für Metallische Werkstoffproben und Bauteile. DIN-Normenausschuss Materialprüfung: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- Alaña, M.; Cutolo, A.; Ruiz de Galarreta, S.; van Hooreweder, B. Influence of relative density on quasi-static and fatigue failure of lattice structures in Ti6Al4V produced by laser powder bed fusion. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Krijger, J.; Rans, C.; van Hooreweder, B.; Lietaert, K.; Pouran, B.; Zadpoor, A.A. Effects of applied stress ratio on the fatigue behavior of additively manufactured porous biomaterials under compressive loading. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2017, 70, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmuller, P.; Favre, J.; Piotrowski, B.; Kenzari, S.; Laheurte, P. Stress Concentration and Mechanical Strength of Cubic Lattice Architectures. Materials 2018, 11, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, C.G.; Varetti, S.; Maggiore, P. Experimental Evaluation of Fatigue Strength of AlSi10Mg Lattice Structures Fabricated by AM. Aerospace 2023, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanning, D.; Nicholas, T.; Haritos, G. On the use of critical distance theories for the prediction of the high cycle fatigue limit stress in notched Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Fatigue 2005, 27, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovski, B.; Downing, D.; Tran, P.; Shidid, D.; Qian, M.; Choong, P.; Brandt, M.; Leary, M. A Monte Carlo simulation-based approach to realistic modelling of additively manufactured lattice structures. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 101092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozanovski, B.; Downing, D.; Tino, R.; Du Plessis, A.; Tran, P.; Jakeman, J.; Shidid, D.; Emmelmann, C.; Qian, M.; Choong, P.; et al. Non-destructive simulation of node defects in additively manufactured lattice structures. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenne, F.; Niendorf, T. Load distribution and damage evolution in bending and stretch dominated Ti-6Al-4V cellular structures processed by selective laser melting. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 121, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Takata, N.; Suzuki, A.; Kobashi, M. Effect of Heat Treatment on Gradient Microstructure of AlSi10Mg Lattice Structure Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2020, 13, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallago, M.; Winiarski, B.; Zanini, F.; Carmignato, S.; Benedetti, M. On the effect of geometrical imperfections and defects on the fatigue strength of cellular lattice structures additively manufactured via Selective Laser Melting. Int. J. Fatigue 2019, 124, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.