Abstract

Objectives: This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on additively manufactured composite-based orthodontic clear aligners compared with thermoformed aligners and other conventional polymeric materials. The influence of material composition, surface roughness, post-processing parameters, and cleaning protocols on microbial colonization was also assessed. Methods: A comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library was conducted up to September 2025. Only in vitro studies investigating microbial adhesion, biofilm biomass, or microbiome changes on three-dimensional (3D)-printed aligner composites were included. Primary outcomes consisted of colony-forming units (CFU), optical density (OD) from crystal violet assays, viable microbial counts, and surface roughness. Risk of bias was assessed using the RoBDEMAT tool. Data were narratively synthesized, and a random-effects meta-analysis was performed for comparable datasets. Results: Five studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, of which two in vitro studies were eligible for meta-analysis. Microbial adhesion and biofilm accumulation were influenced by the manufacturing technique, composite resin formulation, and surface characteristics. Certain additively manufactured aligners exhibited smoother surfaces and reduced bacterial adhesion compared with thermoformed controls, whereas others with increased surface roughness showed higher biofilm accumulation. Incorporating bioactive additives such as chitosan nanoparticles reduced Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation without compromising material properties. The meta-analysis, based on two in vitro studies, demonstrated higher OD values for bacterial biofilm on 3D-printed aligners compared with thermoformed aligners, indicating increased biofilm biomass (p < 0.05), but not necessarily viable bacterial load. Conclusions: Microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed composite clear aligners are governed by resin composition, additive manufacturing parameters, post-curing processes, and surface finishing. Although certain 3D-printed materials display antibacterial potential, the limited number of studies restricts the generalizability of these findings. Clinical Significance: Optimizing composite formulations for 3D printing, alongside careful post-curing and surface finishing, may help reduce microbial colonization. Further research is required before translating these findings into definitive clinical recommendations for clear aligner therapy.

1. Introduction

Clear (esthetic) orthodontic appliances, including aligners and retainers, have become increasingly popular due to their esthetic appeal, removability in certain social situations, and facilitation of oral hygiene [1,2]. Compared with fixed appliances, they reduce the risk of white spot lesions, improve patient comfort, and allow removal during social or functional situations [3]. These advantages have driven the widespread adoption of clear aligner therapy, particularly among adults and compliance-conscious adolescents.

Despite their benefits, clear appliances can accumulate microbial biofilms, which may disrupt the oral microbial balance and contribute to dental caries, gingival inflammation, and candidiasis [4,5,6,7]. Given that clear aligners remain in prolonged contact with the teeth and oral tissues, colonization by microorganisms such as Streptococcus mutans or Candida albicans poses a significant risk of disturbing the oral microflora balance. Oral biofilms, alternative name for dental plaque, are structured microbial communities embedded in extracellular polymeric substances that adhere to teeth and gingival surfaces via the acquired pellicle [7,8]. The presence of an appliance increases available surfaces for bacterial adhesion, reduces salivary clearance, and hinders mechanical cleaning, promoting biofilm formation. Microbial adhesion and biofilm development are strongly influenced by surface characteristics, including roughness, topography, chemical composition, and surface free energy [9,10,11].

Clear aligners are primarily produced via two methods: thermoforming and direct three-dimensional (3D) printing. Thermoformed aligners, made from polymers such as polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PET-G), polyurethane, or copolyester blends, typically exhibit smoother surfaces [2,12,13]. In contrast, 3D-printed aligners are fabricated layer by layer using photopolymerizable resins, which may result in higher surface roughness and require post-processing, including washing and additional light curing, to optimize mechanical and surface properties [14,15]. Additive manufacturing offers advantages such as precise control over aligner geometry, reduced material waste, shorter production times, and enhanced design flexibility [16,17,18,19].

Despite the growing clinical adoption of 3D-printed aligners, evidence on their microbiological performance remains limited. Only a few studies have assessed microbial adhesion or biofilm formation on these appliances, often focusing on single microbial species or mixed but unidentified oral microbiota [17,18,19,20,21]. As clear aligners are typically worn for 20–22 h per day, understanding their microbiological behavior is clinically important. Continuous intraoral exposure promotes biofilm formation, which may affect caries risk, gingival health, and the long-term safety of the appliance. Evaluating how aligner material, surface characteristics, and post-processing parameters influence biofilm accumulation is therefore essential for optimizing patient outcomes and maintaining oral health during orthodontic treatment.

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed clear aligners compared with conventional thermoformed appliances. Additionally, it examines the effects of surface properties, post-processing, and cleaning protocols on microbial colonization. The null hypothesis is that no significant differences exist between 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners regarding microbial adhesion and biofilm formation. Previous reviews have primarily focused on conventional aligners or have only qualitatively summarized microbial outcomes, without critically evaluating the influence of 3D printing parameters, resin composition, or surface finishing on biofilm formation. Moreover, no prior review has synthesized the available quantitative data to enable a direct comparison between 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners. By integrating both systematic review and meta-analytic approaches, this study provides a comprehensive and evidence-based evaluation of microbial adhesion on 3D-printed aligners, offering insights into material- and process-specific factors that can inform future research and clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines and followed the methodological recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [22].

The review protocol was prospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) under the identifier: DOI: [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/XGTSW].

The research question was structured according to the PICOT framework: Population (P): Clear aligner materials; Intervention (I): 3D-printed clear aligner materials or resins; Comparator (C): Thermoformed aligners or alternative aligner materials; Outcomes (O): Primary outcomes: Microbial adhesion (colony-forming units (CFU) or log CFU), biofilm biomass (optical density (OD), crystal violet assay), viable microbial counts, and surface roughness. Secondary outcomes: Microbiome diversity, clinical plaque indices, and cleaning effectiveness; Type (T): In vitro, ex vivo, or clinical studies involving 3D-printed aligners.

The focused research question was: “Do 3D-printed orthodontic clear aligners exhibit different microbial adhesion and biofilm formation compared with thermoformed aligners, and how do surface properties, post-processing, and cleaning protocols influence these outcomes?”

2.2. Information Sources

A comprehensive electronic literature search was performed in MEDLINE via PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and EMBASE databases to identify relevant studies evaluating microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed orthodontic aligners. The search included publications up to September 2025. The strategy aimed to retrieve in vitro, ex vivo, and clinical studies that investigated microbial adhesion, biofilm accumulation, or surface characteristics of 3D-printed aligner materials. The detailed search strategy employed in PubMed and subsequently adapted to the other databases is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy performed at PubMed and adapted to the other databases.

Additionally, manual screening of the reference lists of all included studies and relevant review articles was performed to ensure comprehensive coverage of potentially eligible publications.

2.3. Study Selection

Two independent reviewers screened all retrieved titles and abstracts for eligibility according to the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria (R.B. and N.N.). Full-text evaluation was subsequently conducted for studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or, if necessary, consultation with a third reviewer to achieve consensus (A.A.H.). Inclusion criteria: In vitro, ex vivo, or clinical studies. Studies assessing microbial adhesion, biofilm formation, or microbiome characteristics on 3D-printed aligner materials with a unit harmonization. Studies comparing 3D-printed aligners with thermoformed aligners, untreated controls, or other 3D-printed materials. Only studies published in the English language were considered eligible. Exclusion criteria: Studies not involving 3D-printed aligners. Animal or primary teeth studies. Narrative reviews, expert opinions, letters, case reports, case series, pilot studies, editorials, or conference abstracts without quantitative data.

2.4. Data Extraction

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized data collection form (R.B. and A.A.H.). The following information was recorded for each study: Author and year, 3D-printed material aligner tested, thermoformed material aligner tested, microorganisms’ strains evaluated, microbiological assay, and main results. All extracted data were cross-checked for accuracy, and discrepancies were resolved by consensus among reviewers (N.N and C.E.C.-S.). The results were narratively synthesized to identify trends, similarities, and differences among studies.

Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, which quantifies the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance. An I2 value below 25% indicates low heterogeneity, values between 25 and 75% reflect moderate heterogeneity, and values above 75% indicate substantial heterogeneity.

2.5. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality and risk of bias of the included studies were evaluated using the Risk of Bias Tool for In Vitro Studies (RoBDEMAT) [23]. This tool assesses four domains: D1—Planning and Allocation: inclusion of control/reference groups, randomization of samples, and justification of sample size; D2—Sample/Specimen Preparation: standardization of experimental procedures and uniformity of conditions; D3—Outcome Assessment: reproducibility of methods and implementation of examiner/operator blinding; D4—Data Analysis and Reporting: appropriateness of statistical analysis and clarity of data presentation.

Each criterion within these domains was rated as “sufficiently reported”, “insufficiently reported”, “not reported”, or “not applicable.” The assessment was independently conducted by two reviewers, and any disagreements were resolved through discussion or involvement of a third reviewer to reach consensus.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager software (version 5.3.5; The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). A random-effects model was applied to account for potential heterogeneity among studies. Pooled-effect estimates were calculated by comparing standardized mean differences (SMD) for microbial adhesion outcomes between 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Heterogeneity among studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q test and quantified with the I2 statistic.

3. Results

3.1. Search Strategy

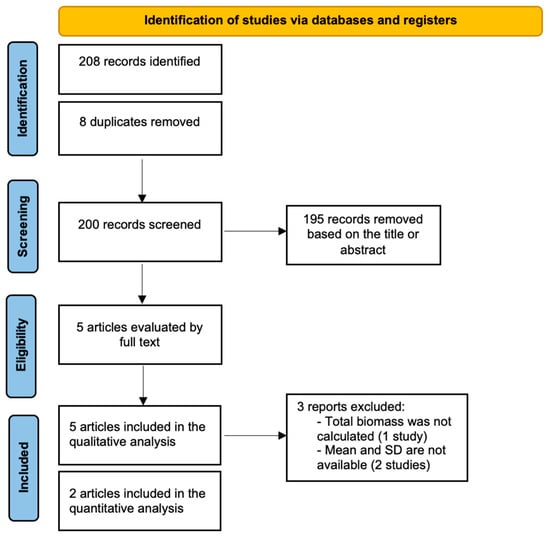

A comprehensive electronic search yielded a total of 208 records across the selected databases. After removing duplicates, 200 unique records remained for screening. Based on title and abstract evaluation, 195 articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, five studies were included in the qualitative synthesis (systematic review) [20,21,24,25,26]. Only two studies [20,26] were involved in the meta-analysis. For the other articles [21,24,25], either the mean and standard deviations were not reported, or the total biomass could not be calculated. The complete study selection process is outlined in the PRISMA flowchart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart summarizing the screening process.

3.2. Main Findings

The qualitative synthesis of the included studies is presented in Table 2. These studies evaluated microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed clear aligner materials compared with conventional thermoformed aligners. Factors investigated included printing technology, material composition, surface roughness, post-processing protocols, and antimicrobial modifications.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the studies included in the review.

Schubert et al. (2021) compared PolyJet, Digital Light Processing (DLP), and Stereolithography Apparatus (SLA) 3D-printed resins with thermoformed and pressed acrylic resins. Candida albicans adhesion was higher on 3D-printed and milled specimens, whereas Streptococcus mutans adhesion was not significantly different between materials [21]. No statistically significant correlation was observed between surface roughness, surface free energy, and microbial adhesion.

Wuersching et al. (2022) evaluated multispecies biofilm formation on various 3D-printed materials and thermoformed controls. 3D-printed aligners generally exhibited smoother surfaces and reduced bacterial adhesion compared with thermoformed and PMMA specimens. KeySplint Soft and PMMA showed the highest surface roughness and bacterial accumulation. A positive correlation between surface roughness and bacterial adhesion was reported (r = 0.69; p = 0.04) [20].

Taher and Rasheed (2023) incorporated chitosan nanoparticles into Dental LT Clear V2 resin at 3% and 5% concentrations. Both concentrations significantly reduced Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation without affecting mechanical or biological properties [24].

Moradinezhad (2024) compared microbial colonization on dx Ortho (Detax Freeprint 3D) and multiple thermoformed aligners using a multispecies biofilm model. No statistically significant differences in microbial adhesion were observed among the tested materials [25].

Bozkurt et al. (2025) conducted a longitudinal assessment of mono- and multispecies biofilm accumulation on a 3D-printed resin (Graphy Tera Harz TC-85) and five thermoformed aligners. Streptococcus mutans adhesion was significantly higher on ClearCorrect and Graphy at 120–168 h. Mixed Streptococcus mutans + Lactobacillus acidophilus biofilms were more pronounced on Graphy than on Invisalign at 120 and 168 h (p < 0.05) [26].

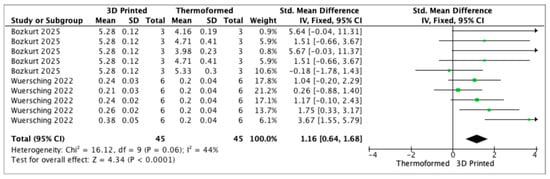

3.3. Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included two studies [20,26]. The OD of bacterial biofilm was significantly higher for 3D-printed aligners compared with thermoformed aligners (p < 0.05, Figure 2). Due to the small number of studies and variability in experimental models, these results should be interpreted with caution. In addition, the OD reflects biofilm biomass and does not necessarily indicate clinical pathogenicity.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the optical density of bacteria for 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners.

3.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The quality assessment and risk of bias for the studies included in this systematic review are summarized in Table 3. In Domain D1 (planning and allocation), all studies adequately included a control group (Item 1.1); however, sample randomization (Item 1.2) was inconsistently reported, with one study [Taher & Rasheed, 2023] being insufficiently reported, and justification of sample size (Item 1.3) was largely absent across the studies. In Domain D2 (sample/specimen preparation), most studies reported sufficient standardization of materials and samples (Item 2.1) and maintained uniform experimental conditions (Item 2.2), suggesting low risk of bias for sample preparation. For Domain D3 (outcome assessment), testing procedures and measured outcomes (Item 3.1) were generally well described and consistent across studies; however, operator blinding (Item 3.2) was not reported in most studies, with only Moradinezhad (2024) [25] clearly reporting blinding, indicating a potential for detection bias in the other studies. In Domain D4 (data treatment and outcome reporting), statistical analyses (Item 4.1) and reporting of results (Item 4.2) were largely adequate, transparent, and appropriately applied in all included studies.

Table 3.

Quality analysis of studies included in the systematic review, separated by their risk of bias in different domains. R—sufficiently reported/adequate, NR—not reported; IR—insufficiently reported; and NA—not applicable.

Overall, Moradinezhad (2024) [25] demonstrated the most comprehensive reporting across all domains and was considered at low risk of bias. Other studies, including Schubert et al. (2021) [21], Wuersching et al. (2022) [20], Taher & Rasheed (2023) [24], and Bozkurt et al. (2025) [26], presented some limitations in randomization, sample size justification, or operator blinding, indicating a moderate risk of bias in specific domains.

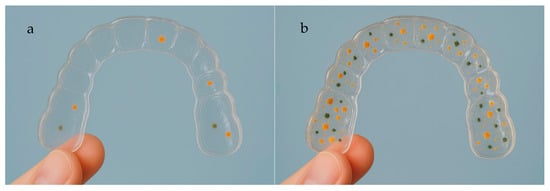

Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate clinical differences in microbial accumulation on clear orthodontic aligners and are provided as illustrative examples, not as data derived from the included studies. Figure 3 presents a clinical image of a clear aligner exhibiting a clean and transparent surface, with no visible accumulation of microorganisms, reflecting optimal oral hygiene and effective maintenance. In contrast, Figure 4 shows a clear aligner with evident microbial deposits and surface cloudiness, indicating biofilm accumulation due to inadequate cleaning or prolonged wear. Figure 5 provides a detailed view of the inner surface of clear aligners, highlighting variations in microbial adherence and biofilm development. In Figure 5a, a lower level of bacterial adhesion is observed, while Figure 5b demonstrates a denser microbial layer and more extensive biofilm formation. These images collectively emphasize the importance of proper 3D-printed aligner hygiene to prevent bacterial colonization and maintain oral health during orthodontic treatment.

Figure 3.

Clinical illustration showing clear orthodontic aligners with no accumulation of microorganisms on the surface.

Figure 4.

Clinical illustration showing clear orthodontic aligners with visible accumulation of microorganisms on the surface.

Figure 5.

Detailed view of the inner surface of a clear aligner showing different microbial adherence and biofilm formation (a): lower bacterial adhesion; (b): Higher bacterial adhesion.

3.5. Study Heterogeneity

Included studies differed in microbial models, aligner materials, biofilm quantification methods, and post-processing protocols. These variations limit direct comparisons and preclude broad generalizations. Nevertheless, the evidence indicates that surface roughness, resin composition, and the inclusion of bioactive components influence microbial adhesion on 3D-printed aligners. Despite the limited data, an analysis was performed to provide a preliminary quantitative synthesis of the available evidence, and all limitations and heterogeneity considerations are explicitly discussed.

4. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed clear aligners in comparison with conventional thermoformed appliances. The findings consistently indicate that material composition, surface characteristics, and post-processing protocols are major determinants of microbial colonization [24,25,26]. Some 3D-printed resins exhibited smoother surfaces and lower bacterial adhesion than thermoformed aligners, suggesting that precision additive manufacturing and optimized post-curing procedures can reduce surface irregularities that serve as functions for bacterial attachment. In contrast, aligners with higher surface roughness or unmodified resin compositions showed increased biofilm formation, consistent with the role of microtopography in facilitating bacterial retention and biofilm maturation. The meta-analysis revealed that the OD of bacterial biofilm was significantly higher for 3D-printed aligners compared with thermoformed aligners (p < 0.05). Thus, the null hypothesis tested is rejected.

Schubert et al. (2021) reported greater Candida albicans adhesion on 3D-printed and milled resins compared to thermoformed and pressed materials, whereas Streptococcus mutans adhesion was largely unaffected by fabrication method [21]. Evidence regarding Streptococcus mutans adhesion to polymeric dental materials in vitro is inconsistent, likely due to differences in experimental conditions [20,27,28,29]. Candida albicans appeared more sensitive to physico-chemical variations among resins, consistent with Ozel et al., who observed species-specific differences in microbial adherence to resin-based provisional crown materials [29]. Species-specific factors, such as SpaP in Streptococcus mutans and Hyphal wall protein 1 in Candida albicans, as well as differences in ATP metabolism between bacteria and fungi, may further explain these patterns [30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Overall, these findings suggest that printing technology alone may not be the sole determinant of microbial adhesion, highlighting the importance of additional material and environmental factors.

Similarly, Wuersching et al. (2022) observed that smoother 3D-printed resins reduced multispecies biofilm formation relative to thermoformed and PMMA specimens, with a positive correlation between surface roughness and bacterial adhesion (r = 0.69; p = 0.04), highlighting the importance of minimizing roughness to reduce colonization risk [20]. In their study, whole thermoplastic splints were used to better reflect clinically relevant surface variations, revealing preferential biofilm accumulation on inner surfaces and gingival margins, which are prone to caries and gingivitis [20,37,38]. Microbial adhesion was also influenced by polymerization technique, surface energy, hydrophilicity, and degree of conversion, with thermoplastic splints potentially favoring bacterial growth due to residual monomers and polar surfaces. Discrepancies between total biofilm mass and viable bacteria suggest that metabolic activity, environmental conditions, and biofilm architecture further modulate colonization [39,40,41,42,43]. Overall, minimizing surface roughness while considering material composition and finishing protocols is critical to limit biofilm formation on 3D-printed oral appliances [44].

Chemical modifications of 3D-printed resins represent an additional strategy to limit microbial adhesion. Taher and Rasheed (2023) demonstrated that incorporation of 3–5% chitosan nanoparticles into Dental LT Clear V2 resin significantly inhibited Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation without compromising mechanical or biological properties. The antimicrobial effect of chitosan likely stems from its cationic nature, which disrupts bacterial membranes and interferes with biofilm formation [24]. The positively charged amino groups in chitosan interact with the negatively charged bacterial cell membranes, causing membrane destabilization, increased permeability, and eventual leakage of intracellular components. This electrostatic disruption inhibits bacterial growth and prevents the early stages of biofilm formation on the resin surface [45,46]. Additionally, chitosan can interfere with bacterial metabolism and adhesion mechanisms. By binding to surface proteins and extracellular polymeric substances, chitosan limits bacterial attachment and aggregation, reducing the development of dense biofilms. Its nanoscale size ensures a large surface area for interaction with bacterial cells, enhancing its antibiofilm efficacy without compromising the mechanical or biocompatible properties of the 3D-printed resin [24,47,48,49]. So, chitosan dispersed in the resin reinforces the material through enhanced interfacial bonding and its high surface area, forming a network-like structure that improves stress distribution and increases the modulus of elasticity of the material [47,49].

However, Moradinezhad (2024), found no significant differences in microbial adhesion among 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners, suggesting that environmental factors, microbial interactions, and oral conditions may modulate biofilm formation beyond material properties [25].

Clear orthodontic retainers are typically made from polymers such as polypropylene, thermoplastic polyurethane, polycarbonate, polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyethylene terephthalate glycol (PETG), ethylene-vinyl acetate, or polyvinyl chloride [7,50,51,52]. In orthodontic 3D printing, materials include epoxy resins (for stereolithography), polylactic acid, nylon, acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene, photopolymers, polycarbonate, and metals like steel or titanium [25]. In the present study, no significant differences in biofilm formation were observed among the retainers [25], consistent with Tektas et al. [7]. Biofilm formation is influenced by chemical composition, surface roughness, surface area, wettability, and other surface properties [52,53,54]. Although PETG is the most used material for aligners due to its transparency and amorphous nature [7], variations in surface roughness can affect wetting and the total work of adhesion, which in turn may influence pellicle formation and biofilm retention [7,55]. Other studies have also shown that intraoral exposure alters mechanical properties and surface roughness of aligners, primarily through hydrolytic degradation and water-induced changes in polyurethanes [7,56].

Microbial adhesion to abiotic surfaces is the first step in biofilm formation, particularly on orthodontic appliances [52,57]. Surface roughness, free energy, surface tension, and chemical composition affect this initial adhesion, as well as the binding of salivary proteins [52,58,59]. Electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions further facilitate early bacterial attachment [52,58,59]. In the oral cavity, microorganisms can colonize a variety of surfaces, including teeth, restorative materials, prosthodontic appliances, implants, and clear or removable orthodontic devices, depending on the unique surface properties of each material [7,60,61].

Bozkurt et al. (2025) reported time-dependent biofilm accumulation across all aligners, with certain 3D-printed resins showing higher susceptibility at specific time points. These observations indicate that while material selection and surface optimization are critical, biofilm formation remains a dynamic process influenced by multiple intraoral factors, including saliva composition, diet, and oral hygiene. Also, this can be explained by the inherent differences in surface roughness, free surface energy, and chemical composition among materials, which modulate initial bacterial attachment. Moreover, production techniques, such as direct 3D printing of Graphy aligners in 100 µm layers, may create surface topographies and microenvironments that favor microbial adhesion compared with traditionally thermoformed or other printed aligners [26]. Biofilm formation is a complex, dynamic process involving multiple microbial species, and the oral environment exerts additional influence through saliva composition, diet, and oral hygiene [7,62]. In vitro studies using Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus acidophilus have shown that dual-species interactions can enhance biofilm formation on certain aligner surfaces, reflecting the collaborative nature of oral microbial communities [7,63,64]. Temporal increases in biofilm formation across all materials highlight that prolonged aligner wear, even with intermittent removal, can exacerbate microbial colonization by creating microgrooves or surface imperfections that facilitate bacterial retention [65,66,67,68,69]. These findings underscore the clinical need for careful material selection, maintenance of aligner integrity, and stringent oral hygiene to mitigate biofilm-associated risks during long-term orthodontic treatment.

The elevated optical density of bacteria observed on 3D-printed aligners compared to thermoformed aligners may be attributed to several factors. It was indicated that 3D-printed aligners often exhibit increased surface roughness and porosity, which can provide more places for bacterial attachment, favoring biofilm development [70]. Additionally, differences in polymer composition, hydrophobicity, and surface energy between 3D-printed and thermoformed materials can influence microbial adherence. For instance, certain 3D printing resins may have surface chemistries more conducive to bacterial colonization [71]. Moreover, incomplete post-curing or polishing of 3D-printed aligners may leave residual monomers or irregularities, further promoting bacterial accumulation. Higher bacterial accumulation could increase the risk of enamel demineralization, gingival inflammation, or malodor during aligner therapy. Clinicians should emphasize proper cleaning protocols and consider surface finishing methods to reduce bacterial retention [20,26].

The present review demonstrates heterogeneity in microbial models, aligner compositions, and testing protocols. Nevertheless, the collective evidence underscores that resin type, surface smoothness, and antimicrobial modifications can reduce microbial adhesion, thereby potentially improving the oral health safety of 3D-printed aligners. Clinically, these considerations are essential to minimize risks such as enamel demineralization, gingivitis, and halitosis during prolonged aligner use.

Limitations of the current evidence include the predominance of in vitro studies, limited clinical data, and variability in microbial models and biofilm quantification methods. Most studies examined short-term microbial adhesion, with limited assessment of long-term colonization under real intraoral conditions. In addition, few studies investigated multispecies biofilms that better replicate the complexity of oral microbiota.

Future directions should focus on longitudinal clinical studies comparing 3D-printed and thermoformed aligners in terms of biofilm formation, patient-related oral hygiene, and clinical outcomes. Research on novel resin formulations with inherent antimicrobial properties, optimized post-processing protocols, and standardization of testing methods is also warranted to improve the reliability and applicability of results.

Considering the findings of this review, it can be assumed that microbial adhesion on 3D-printed clear aligners is determined by resin type, surface properties, and chemical modifications. Certain 3D-printed materials demonstrate comparable or lower microbial accumulation than thermoformed aligners, whereas others, particularly those with rougher surfaces or unmodified resins, may present a higher risk of biofilm formation. Optimizing material selection, post-processing, and potential antimicrobial modifications can enhance the microbiological performance of clear aligners and support safer clinical outcomes in future studies.

Understanding the influence of material composition and surface characteristics on microbial adhesion is essential for the safe and effective use of clear aligners. The findings of this review highlight that optimized 3D-printed resins and improved post-processing protocols can reduce biofilm formation, potentially lowering the risk of oral inflammation and caries during orthodontic treatment. Clinicians should consider both material selection and patient hygiene protocols when integrating 3D-printed aligners into clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on 3D-printed clear aligners remain a complex interplay of material composition, surface characteristics, post-processing protocols, and potential antimicrobial modifications. Optimizing post-processing and finishing procedures to achieve smoother surfaces, combined with the incorporation of bioactive agents such as chitosan nanoparticles, appears to offer the most promising strategy to minimize bacterial colonization and enhance the microbiological performance of these appliances. Tailoring aligner materials and surface treatments to the clinical context may therefore provide the most reliable pathway to reduce biofilm-related oral health risks during orthodontic therapy.

However, the limited number of included studies and small overall sample size restrict the generalizability of the findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B. and A.A.H.; methodology, L.H., S.H., R.B., N.N., R.K., C.E.C.-S. and N.K.; software, R.B., S.H., C.E.C.-S. and L.H.; validation, N.N., A.A.H., R.K. and R.B.; formal analysis, L.H., R.B., S.H., A.F.-L., R.K., A.O., A.A.H. and N.K.; investigation, R.B., L.H., A.A.H. and R.K.; resources, R.B., L.H., N.N., A.F.-L., A.A.H., A.O. and R.K.; data curation, R.B., L.H. and N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B., S.H., L.H., N.N., A.A.H. and R.K.; writing—review and editing, R.B., C.E.C.-S., L.H., N.N., A.A.H., A.O., R.K. and N.K.; visualization, R.B. and C.E.C.-S.; supervision, R.B.; project administration, N.K.; funding acquisition, S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rouzi, M.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Long, H.; Lai, W.; Li, X. Impact of clear aligners on oral health and oral microbiome during orthodontic treatment. Int. Dent. J. 2023, 73, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torkomian, T.; de la Iglesia, F.; Puigdollers, A. 3D-printed clear aligners: An emerging alternative to the conventional thermoformed aligners?—A systematic review. J. Dent. 2025, 155, 105616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimunović, L.; Čimić, S.; Meštrović, S. Three-Dimensionally Printed Splints in Dentistry: A Comprehensive Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, J.B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Y.L.; Bai, H. Alterations of the oral microbiome in patients treated with the Invisalign system or with fixed appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2019, 156, 633–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchese, A.; Bondemark, L.; Marcolina, M.; Manuelli, M. Changes in oral microbiota due to orthodontic appliances: A systematic review. J. Oral Microbiol. 2018, 10, 1476645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, S.N.; Xavier, G.M.; Cobourne, M.T.; Eliades, T. Effect of orthodontic treatment on the subgingival microbiota: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2018, 21, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tektas, S.; Thurnheer, T.; Eliades, T.; Attin, T.; Karygianni, L. Initial bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation on aligner materials. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 908–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; You, Y.; Yi, L.; Wu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, H.; Shen, Y.; Guo, J.; Huang, C. Dental plaque-inspired versatile nanosystem for caries prevention and tooth restoration. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 20, 418–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.; Wutscher, E.; Brambilla, E.; Schneider-Feyrer, S.; Giessibl, F.J.; Hahnel, S. Influence of surface properties of resin-based composites on in vitro Streptococcus mutans biofilm development. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 120, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Song, C.W.; Jung, J.H.; Ahn, S.; Ferracane, J. The effects of surface roughness of composite resin on biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans in the presence of saliva. Oper. Dent. 2012, 37, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirynen, M.; Bollen, C.M. The influence of surface roughness and surface-free energy on supra- and subgingival plaque formation in man: A review of the literature. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1995, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrì, M.; Murmura, G.; Varvara, G.; Traini, T.; Festa, F. Clinical performances and biological features of clear aligner materials in orthodontics. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 819121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, B.P.; Siva, S.; Duraisamy, S.; Idaayath, A.; Kannan, R. Properties of orthodontic clear aligner materials—A review. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2021, 10, 3288–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasef, A.A.; El-Beialy, A.R.; Mostafa, Y.A. Virtual techniques for designing and fabricating a retainer. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindal, P.; Worcester, F.; Siena, F.L.; Forbes, C.; Juneja, M.; Breedon, P. Mechanical behaviour of 3D printed vs thermoformed clear dental aligner materials under non-linear compressive loading using FEM. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2020, 112, 104045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, C.-Y.; Guvendiren, M. Current and emerging applications of 3D printing in medicine. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 024102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, A.; Marti, B.M.; Sauret-Jackson, V.; Darwood, A. 3D printing in dentistry. Br. Dent. J. 2015, 219, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billiet, T.; Vandenhaute, M.; Schelfhout, J.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P. A review of trends and limitations in hydrogel-rapid prototyping for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 6020–6041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Lowery, L.; Gibreel, M.; Vallittu, P.K.; Lassila, L. Evaluation of the mechanical properties and degree of conversion of 3D printed splint material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 115, 104254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuersching, S.N.; Westphal, D.; Stawarczyk, B.; Edelhoff, D.; Kollmuss, M. Surface properties and initial bacterial biofilm growth on 3D-printed oral appliances: A comparative in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2667–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A.; Bürgers, R.; Baum, F.; Kurbad, O.; Wassmann, T. Influence of the manufacturing method on the adhesion of Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans to oral splint resins. Polymers 2021, 13, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, A.H.; Sauro, S.; Lima, A.F.; Loguercio, A.D.; Della Bona, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Collares, F.M.; Staxrud, F.; Ferracane, J.; Tsoi, J.; et al. RoBDEMAT: A risk of bias tool and guideline to support reporting of pre-clinical dental materials research and assessment of systematic reviews. J. Dent. 2022, 127, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taher, B.B.; Rasheed, T.A. The impact of adding chitosan nanoparticles on biofilm formation, cytotoxicity, and certain physical and mechanical aspects of directly printed orthodontic clear aligners. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradinezhad, M.; Abbasi Montazeri, E.; Hashemi Ashtiani, A.; Pourlotfi, R.; Rakhshan, V. Biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Staphylococcus aureus, Lactobacillus casei, and Candida albicans on 5 thermoform and 3D printed orthodontic clear aligner and retainer materials at 3 time points: An in vitro study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.P.; Demirci, M.; Erdogan, P.; Kayalar, E. Comparison of microbial adhesion and biofilm formation on different orthodontic aligners. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2025, 167, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faltermeier, A.; Bürgers, R.; Rosentritt, M. Bacterial Adhesion of Streptococcus mutans to Esthetic Bracket Materials. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2008, 133, S99–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, A.C.; Hahnel, S.; König, A.; Brambilla, E. Resin Composite Blocks for Dental CAD/CAM Applications Reduce Biofilm Formation in Vitro. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozel, G.S.; Guneser, M.B.; Inan, O.; Eldeniz, A.U. Evaluation of C. albicans and S. mutans Adherence on Different Provisional Crown Materials. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2017, 9, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esberg, A.; Sheng, N.; Mårell, L.; Claesson, R.; Persson, K.; Borén, T.; Strömberg, N. Streptococcus mutans Adhesin Biotypes That Match and Predict Individual Caries Development. eBioMedicine 2017, 24, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, L.J.; Maddocks, S.E.; Larson, M.R.; Forsgren, N.; Persson, K.; Deivanayagam, C.C.; Jenkinson, H.F. The Changing Faces of Streptococcus Antigen I/II Polypeptide Family Adhesins. Mol. Microbiol. 2010, 77, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.L.; Wilson, D.; Hube, B. Candida albicans Pathogenicity Mechanisms. Virulence 2013, 4, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, P. Adhesins in Candida albicans. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1999, 2, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-X.; Wu, H.-T.; Liu, Y.-T.; Jiang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-S.; Liu, W.-D.; Zhu, K.-J.; Li, D.-M.; Zhang, H. The F1Fo-ATP Synthase β Subunit Is Required for Candida albicans Pathogenicity Due to Its Role in Carbon Flexibility. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lyu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, H. The Fungal-Specific Subunit i/j of F1FO-ATP Synthase Stimulates the Pathogenicity of Candida albicans Independent of Oxidative Phosphorylation. Med. Mycol. 2020, 59, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, L.S.; Brown, D.G. Variation in Bacterial ATP Concentration during Rapid Changes in Extracellular PH and Implications for the Activity of Attached Bacteria. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 132, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Listgarten, M.A. The role of dental plaque in gingivitis and periodontitis. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1988, 15, 485–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waerhaug, J. Effect of rough surfaces upon gingival tissue. J. Dent. Res. 1956, 35, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjan, A.H.; Chan, C.A. The polishability of posterior composites. J. Prosthet. Dent. 1989, 61, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J.; Reymus, M.; Wiedenmann, F.; Edelhoff, D.; Hickel, R.; Stawarczyk, B. Temporary 3D printed fixed dental prosthesis materials: Impact of post printing cleaning methods on degree of conversion as well as surface and mechanical properties. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 34, 784–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reymus, M.; Stawarczyk, B. In vitro study on the influence of postpolymerization and aging on the Martens parameters of 3D-printed occlusal devices. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2021, 125, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teughels, W.; Van Assche, N.; Sliepen, I.; Quirynen, M. Effect of material characteristics and/or surface topography on biofilm development. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2006, 17, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokes, J.M.; Lopatkin, A.J.; Lobritz, M.A.; Collins, J.J. Bacterial metabolism and antibiotic efficacy. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabe, M.; Verdes, D.; Seeger, S. Understanding protein adsorption phenomena at solid surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 162, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantravadi, P.K.; Kalesh, K.A.; Dobson, R.C.J.; Hudson, A.O.; Parthasarathy, A. The Quest for Novel Antimicrobial Compounds: Emerging Trends in Research, Development, and Technologies. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, H.; Bishnoi, P.; Yadav, A.; Patni, B.; Mishra, A.P.; Nautiyal, A.R. Antimicrobial Resistance and the Alternative Resources with Special Emphasis on Plant-Based Antimicrobials—A Review. Plants 2017, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya, K.; Jisha, M.S. Chitosan Nanoparticles Preparation and Applications. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseinsyah, S.; Amri, F.; Husin, K.; Ismail, H. Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Chitosan-Filled Polypropylene Composites: The Effect of Acrylic Acid. J. Vinyl. Addit. Technol. 2011, 17, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woźniak, A.; Biernat, M. Methods for Crosslinking and Stabilization of Chitosan Structures for Potential Medical Applications. J. Bioact. Compat. Polym. 2022, 37, 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichu, Y.M.; Alwafi, A.; Liu, X.; Andrews, J.; Ludwig, B.; Bichu, A.Y.; Zou, B. Advances in orthodontic clear aligner materials. Bioact. Mater. 2023, 22, 384–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Daryanavard, H.; Ashtiani, A.H.; Moradinejad, M.; Rakhshan, V. A systematic review of biocompatibility and safety of orthodontic clear aligners and transparent vacuum-formed thermoplastic retainers: Bisphenol—A release, adverse effects, cytotoxicity, and estrogenic effects. Dent. Res. J. 2023, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdoon, S.M.; AlSamak, S.; Ahmed, M.K.; Gasgoos, S. Evaluation of biofilm formation on different clear orthodontic retainer materials. J. Orthod. Sci. 2022, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreve, S.; Dos Reis, A.C. Bacterial adhesion to biomaterials: What regulates this attachment? A review. Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2021, 57, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreve, S.; Dos Reis, A.C. Effect of surface properties of ceramic materials on bacterial adhesion: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suter, F.; Zinelis, S.; Patcas, R.; Schätzle, M.; Eliades, G.; Eliades, T. Roughness and wettability of aligner materials. J. Orthod. 2020, 47, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, A.K.; Cantele, A.; Polychronis, G.; Zinelis, S.; Eliades, T. Changes in roughness and mechanical properties of Invisalign® appliances after one- and two-weeks use. Materials 2019, 12, 2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldarriaga Fernández, I.C.; Busscher, H.J.; Metzger, S.W.; Grainger, D.W.; van der Mei, H.C. Competitive time- and density-dependent adhesion of staphylococci and osteoblasts on crosslinked poly(ethylene glycol)-based polymer coatings in co-culture flow chambers. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dittmer, M.P.; Hellemann, C.F.; Grade, S.; Heuer, W.; Stiesch, M.; Schwestka-Polly, R.; Demling, A.P. Comparative three-dimensional analysis of initial biofilm formation on three orthodontic bracket materials. Head Face Med. 2015, 11, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velliyagounder, K.; Ardeshna, A.; Koo, J.; Rhee, M.; Fine, D.H. The microflora diversity and profiles in dental plaque biofilms on brackets and tooth surfaces of orthodontic patients. J. Indian Orthod. Soc. 2019, 53, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawazir, M.; Dhall, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, B.; Hwang, G. Effect of surface stiffness in initial adhesion of oral microorganisms under various environmental conditions. Colloids Surf. B 2023, 221, 112952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.E.; Sahin, Z.; Yikici, C.; Duyan, S.; Kilicarslan, M.A. Bacterial adhesion to composite resins produced by additive and subtractive manufacturing. Odontology 2024, 112, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baybekov, O.; Stanishevskiy, Y.; Sachivkina, N.; Bobunova, A.; Zhabo, N.; Avdonina, M. Isolation of clinical microbial isolates during orthodontic aligner therapy and their ability to form biofilm. Dent. J. 2023, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurnheer, T.; Bostanci, N.; Belibasakis, G.N. Microbial dynamics during conversion from supragingival to subgingival biofilms in an in vitro model. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2016, 31, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eliades, T.; Eliades, G.; Brantley, W.A. Microbial attachment on orthodontic appliances: I. Wettability and early pellicle formation on bracket materials. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1995, 108, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, R.; Lu, X.; He, X.; Shi, W.; Guo, L. Interspecies interactions between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus agalactiae in vitro. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.P.; Lee, S.J.; Lim, B.S.; Ahn, S.J. Surface characteristics of orthodontic materials and their effects on adhesion of mutans streptococci. Angle Orthod. 2009, 79, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.J.; Lim, B.S.; Lee, S.J. Surface characteristics of orthodontic adhesives and effects on streptococcal adhesion. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2010, 137, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Enriquez, U.; Scougall-Vilchis, R.J.; Contreras-Bulnes, R.; Flores-Estrada, J.; Uematsu, S.; Yamaguchi, R. Quantitative analysis of S. mutans and S. sobrinus cultivated independently and adhered to polished orthodontic composite resins. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012, 20, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihssen, B.A.; Willmann, J.H.; Nimer, A.; Drescher, D. Effect of in vitro aging by water immersion and thermocycling on the mechanical properties of PETG aligner material. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2019, 80, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, S.; Kopp, S.; Goteni, M.; Dahmer, I.; Sayahpour, B. Alterations in the surface roughness and porosity parameters of 3D-printed aligners after intraoral service. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2024, 165, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimunović, L.; Pečanić, P.; Marić, A.J.; Haramina, T.; Rakić, I.Š.; Meštrović, S. Impact of various cleaning protocols on the physical and aesthetic properties of 3D-printed orthodontic aligners. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.