Abstract

This study focuses on the prediction and analysis of temperature distribution during end milling of AISI 4340 steel. The influence of cutting parameters—cutting speed, feed per tooth, and depth of cut—on temperature generation in the cutting zone was investigated using a CCD experimental plan. Temperature was measured with a thermal imaging camera, while the milling process was simulated using Third Wave AdvantEdge 7.1 FEM software. The obtained temperatures ranged from 74 °C to 200 °C, depending on the cutting conditions. A second-order regression model with three factors was developed and showed an average prediction error of 8.62%, while the alternative fitted model had an average error of 10.91%. FEM simulations using AdvantEdge 7.1 demonstrated a somewhat higher deviation, with an average error of 14.75% relative to experiments. The highest deviations for all approaches occurred at extreme cutting parameters (very low or very high depth of cut). The study demonstrates that FEM simulations are an effective tool for predicting thermal behavior in milling and optimizing cutting parameters. Accurate prediction of cutting zone temperatures can improve tool life, enhance process efficiency, and support the selection of optimal machining conditions, which is very important from an industry point of view.

1. Introduction

Milling is among the most important conventional machining operations. It is widely employed in industrial metal processing. Due to its use of multi-toothed tools, milling is by far more complex than turning or drilling. The engagement of multiple cutting edges and the variable chip cross-section during a tooth’s pass introduces significant complexity in the metal process. This leads to phenomena such as tool wear, surface roughness variation, and substantial heat generation in the cutting zone [1,2,3,4]. The cutting temperature serves as a critical indicator of process efficiency, tool life, and surface quality.

Accurate measurement of cutting temperature during milling is challenging due to tool rotation, intermittent tooth engagement, and the dynamic movement of the heat-affected zone. Chips can further interfere with temperature readings, complicating experimental approaches [1,5]. Over the past decades, thermocouples and infrared-based methods have been developed [6]. Infrared thermography is widely used in industry. Non-contact infrared thermography, including pyrometers and infrared cameras, has emerged as the preferred method for capturing high-resolution thermal fields during cutting [2,7].

Due to the high costs and logistical challenges of experimental studies, computational methods have gained prominence. Among these, finite element method (FEM) simulations are widely employed for modeling 2D and 3D cutting processes. FEM simulations enable prediction of cutting forces, chip formation, tool wear, and thermal distribution [8,9,10,11,12]. They allow for detailed investigation of temperature evolution in the cutting zone under varying parameters, including spindle speed, feed rate, and depth of cut. Recent studies show that simulations that incorporate depth-of-cut variations can accurately predict temperature peaks, aiding in the optimization of cutting conditions and prolonging tool life [2,13].

FEM-based simulations are now central to tool design and process optimization. Advanced software packages, such as ANSYS 16.1, Third Wave AdvantEdge 7.1, Abaqus 2017, and Deform3D V11, integrate thermo-mechanical modeling and real material behavior, providing critical insights into heat generation, chip formation, and tool-workpiece interactions. Such simulations allow for reduction in experimental trials, lowering costs and accelerating research and industrial implementation [13,14,15,16,17,18]. Recent research emphasizes predictive modeling of milling operations, particularly regarding thermal phenomena. FEM simulations, validated by experimental infrared thermography, enable optimization of depth of cut, feed rate, and cutting speed [14,16,19].

In the literature, there are several studies that investigate AISI 4340 (turning/milling) [20,21], the influence of coatings (TiAlN) on cutting forces and tool wear, as well as the effects of MQL/cryogenic cooling [22,23]. Also, there are studies that use AdvantEdge for temperature prediction in the machining of AISI 4340 (FEM simulations) [24]. However, these studies are mainly focused on experimental outcomes (forces, wear, roughness) or on the effects of lubrication (MQL/cryogenic), without a broader integration of statistical modeling and detailed simulation-based validation. This study addresses the research gap by an integrated experimental–statistical–numerical approach. It focuses on the prediction and analysis of temperature distribution during the end milling process of AISI 4340 steel.

A systematic comparison of thermographic temperature measurements in end milling with Central Composite Design (CCD) methodology and with validation of AdvantEdge FEM simulations has been conducted. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to quantify the reliability and applicability limits of combining CCD and AdvantEdge for temperature prediction in end milling of AISI 4340 using TiAlN-coated tools.

2. Materials and Methods

In this research, the conditions during the experimental examination of the temperature in the cutting zone during milling processing are first presented. These conditions include workpiece material, machine, tool and processing method. For the input parameters, the following are selected: cutting speed, feed per tooth, and depth of cut. The values of these parameters were varied based on a predefined experimental plan (the CCD methodology was used). The method for measuring cutting temperature with a thermal imaging camera is presented, and then the results of the experimental research are tabulated. After that, a 3D model of the milling process was created using the finite element method in the AdvantEdge software package. Simulations were created according to the experimental plan, and the obtained results were presented. The reliability of the temperature predictions was assessed by comparing thermal imaging camera measurements with the results obtained from the AdvantEdge simulations, following a defined experimental plan.

2.1. Experimental Setup

The experimental machining tests were conducted under dry conditions on a MAHO 600C vertical milling machine at Dynamic Line in Čačak, Serbia. Dry machining was deliberately selected to isolate and accurately evaluate the influence of cutting parameters on the temperature generated in the cutting zone. The presence of coolant significantly changes the thermal load, heat dissipation mechanisms, and tribological behavior at the tool–workpiece interface. By eliminating coolant effects, the study ensures that the measured temperature response originates solely from variations in cutting speed, feed per tooth, and depth of cut, enabling a clearer and more reliable interpretation of their individual contributions.

The main technical specifications of the machine are as follows:

- The power of the electric motor for the main motion: 7.5 kW;

- The speed of the main spindle: from 10 to 3150 o/min;

- The capability of spindle axis rotation: up to 90°.

The workpiece material used in this study was AISI 4340 (30CrNiMo8) alloy steel, selected due to its wide industrial application. The chemical composition and mechanical properties of AISI 4340 steel are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

AISI 4340 steel material properties.

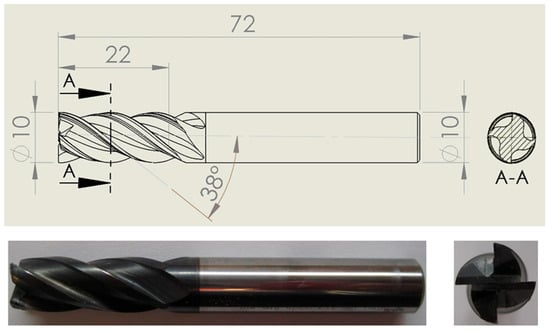

Each specimen was prepared in the form of rectangular samples with dimensions 50 × 30 × 7 mm to ensure uniformity of the testing conditions. The cutting tool employed in the experiments was a solid carbide end mill EC-E4L 10-22/32W10CF72 with a TiAlN coating of 3 µm, supplied by ISCAR, Tefen, Israel [25], diameter 10 mm, with the following characteristics (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

End mill EC-E4L 10-22/32W10CF72 [24].

- Number of teeth z = 4;

- The lead cutting edge angle χ = 30°;

- The flank angle α = 7°;

- The rake angle γ = 12°;

- The helix angle ω = 38°.

The tool geometry and coating were chosen to provide high wear resistance and thermal stability at elevated cutting temperatures. All experiments were conducted under the same conditions without the use of cooling and lubrication methods.

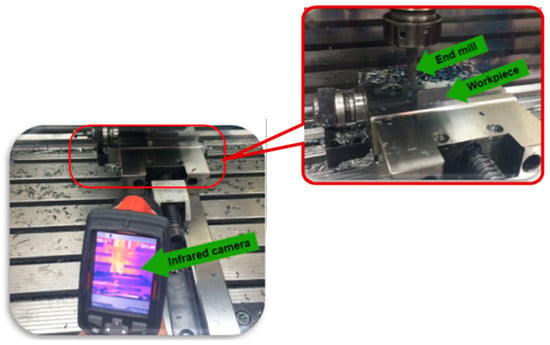

The temperature field in the cutting zone was monitored using a FLIR InfraCAM Western infrared camera, Teledyne FLIR LLC, Wilsonville, OR, USA (Figure 2 which provides high sensitivity to thermal radiation emitted from metallic surfaces [26]. The main technical specifications of the infrared camera are following:

Figure 2.

Experimental setup and setup of the thermal camera.

- The field of view is 25° × 25°, and the measurement system enables detection of point temperatures as well as identification of minimum and maximum values within the defined observation area.

- The device is equipped with a 120 × 120 pixel detector, operating in the spectral range from 7.5 to 13 µm.

- The temperature measurement range of the camera extends from −10 °C to +350 °C, with a measurement accuracy of ±0.1 °C, ensuring reliable monitoring of temperature variations during the milling process.

- The display features are: 3.5″ color LCD, 240 × 240 pixels, video output: MPEG-4 via USB, maximum 50 JPEG images can be stored on the camera and it has a laser router: LocatIR class2, Teledyne FLIR LLC, Wilsonville, OR, USA [26].

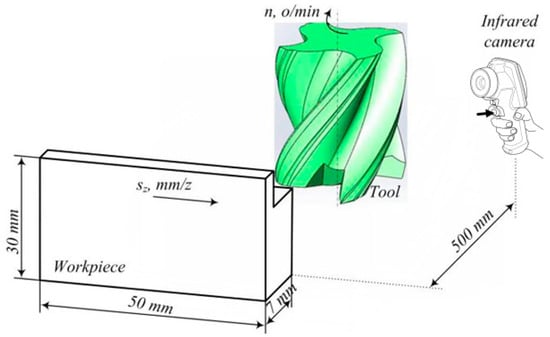

To improve the measurement accuracy, both the workpiece and the tool were coated with a thin layer of matte black paint, ensuring consistent emissivity and minimizing reflection effects during thermal image acquisition. In Figure 3, a schematic representation of the experimental setup is presented. The infrared camera was positioned in close proximity to the cutting zone, with a distance of 500 mm between the camera and the tool.

Figure 3.

The schematic setup of the machining.

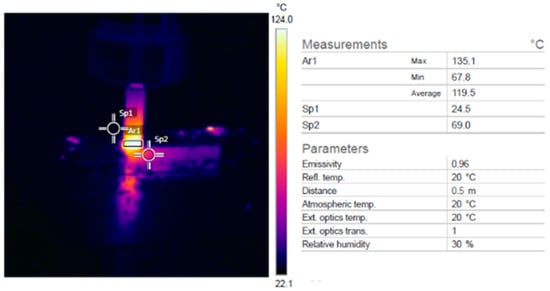

The surfaces of both the workpiece and the tool were assigned an emissivity of 0.96 to ensure accurate thermographic measurements. It should be noted that, for matte black paints commonly used in thermographic measurements, the variation in emissivity with temperature is negligible within the investigated temperature range. The literature and manufacturer data show that the emissivity of such paints ranges between 0.95 and 0.98, with minimal deviations. Since the same paint was applied to both the tool and the workpiece, the surfaces have stable and well-defined optical properties. Therefore, the value of 0.96 can be considered reliable and sufficiently accurate for all measurements within this study. The recorded thermal data were processed using the FLIR Research IR Max 4.2 software package. The temperature measurement using an infrared camera during milling can be affected by the presence of chips and by variations in the viewing angle. In this study, special attention was given to these limitations: the camera was positioned to minimize obstruction caused by chips, and the measurements were taken at a small and stable angle relative to the surface. During the image acquisition, the maximum, average, and minimum temperatures were continuously monitored within a rectangular region of interest measuring 10 × 3 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Temperature distribution for the tool and workpiece.

2.2. Experiment Design Based on a Three-Factor Second-Order Experimental Plan

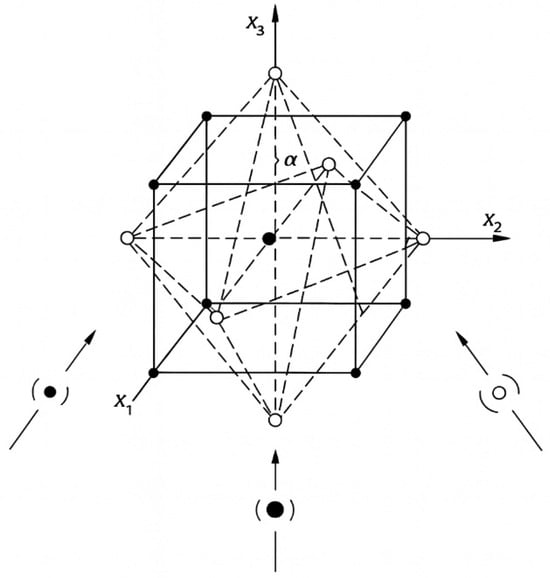

The Central Composite Design (CCD) methodology was applied to the experimental setup, with data analysis carried out according to a three-factor, second-order experimental plan (Figure 5) [27].

Figure 5.

Central Composite Design (CCD) for a three-factor second-order model [27].

This approach integrates regression analysis and dispersion analysis, while also allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the accuracy and reliability of the derived mathematical models.

The total number of experiments for the factorial design, including center points for accuracy verification (k = 3), was augmented by n0 = 4 and nα = 12, yielding the following:

This arrangement ensures sufficient replication for both model accuracy assessment and statistical reliability of the experimental results. The factors were varied across five levels, with the intermediate value between two adjacent levels defined as the geometric mean of those levels.

Values for the cutting speed were determined as follows: 1.31 m/s, 1.23 m/s, 1.15 m/s, 1.1 m/s, and 1.05 m/s; while values for the feed rate were determined as follows: 0.035 mm/z, 0.031 mm/z, 0.028 mm/z, 0.025 mm/z, and 0.021 mm/z. Finally, the values for the cutting depth were determined as follows: 2.00 mm, 1.41 mm, 1 mm, 0.71 mm, and 0.5 mm. All values were selected according to industrial practice. The expert at the company Dynamic Line from Čačak, Serbia, made the recommendation based on 20 years of experience. The design layout is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Design layout.

The calculation was performed within the MS Excel program, and mathematical models were developed without interactive effects (2) and with interactive effects (3) of the parameters, as follows:

For readers interested in further details regarding the three-factor second-order model, additional information can be found in [27].

The results of the evaluation of the significance and adequacy of the models based on the experimental plan are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Evaluation of the significance and adequacy of the mathematical models.

It should be noted that in the FM2 model, the terms p11, p12, p22, and p23 were retained despite their low significance values, because a full second-order quadratic model in a CCD must preserve its hierarchical structure. Removing individual quadratic or interaction terms would disrupt the complete form of the model and introduce a systematic error into the estimation of the remaining coefficients.

2.3. End Milling Simulation

Today, several advanced FEM-based programs are commonly used for the simulation of metal cutting processes, including ANSYS, Third Wave AdvantEdge, Abaqus, and Deform 3D. The appropriate selection of FEM plays a crucial role in determining both the scope and quality of the analysis to be performed [27,28,29].

Third Wave AdvantEdge, a specialized commercial software designed explicitly for the modeling, development, and optimization of machining processes [30] was selected for this study. Its environment is tailored to the simulation of metal cutting, offering a detailed and user-friendly interface that allows the definition and adjustment of parameters for both modeling and simulation. The program is capable of representing complex tool–workpiece interactions and supports a broad range of machining operations.

In AdvantEdge, simulations can be executed in two modes: Demonstration mode, which significantly reduces computation time but with lower accuracy, and Standard mode, which provides higher accuracy at the cost of longer simulation time. It should be emphasized that Demonstration (demo) mode was used due to limitations of the available license, which did not allow the use of the full standard version. The software also integrates with Tecplot 360 [31], which is used for the visualization and detailed analysis of simulation results.

The program contains three primary modules: preprocessing, simulation, and postprocessing. The preprocessing module serves as the starting point where the user defines the tool geometry, material properties, and cutting parameters, as well as controls all simulation settings. The simulation module is where the FEM-based computations are performed; the numerical estimations are internally calculated and not directly visible to the user. Once the computation is complete, the postprocessing module provides tools for interpreting and visualizing results through various graphical outputs and charts. The most commonly analyzed results include chip formation, temperature distribution in the chip and tool, cutting forces.

To create a milling process simulation using FEA software (2016), an established methodological procedure is followed. The main steps include the following: developing a 3D model of the tool and the workpiece in a CAD program, importing the model into an FEM simulation environment, defining the materials of both tool and workpiece, setting simulation parameters, executing the computational analysis, and finally visualizing and interpreting the obtained results.

For the milling simulation in AdvantEdge, the 3D model of the end mill was first created in SolidWorks 2016. A simplified version of the model was then prepared in order to reduce the number of nodes and finite elements, thus optimizing computational efficiency. Only the cutting part of the mill, which directly participates in the machining process, was modeled. This simplification can affect the predicted temperature in the cutting zone, because removing smaller features changes the local heat distribution and tool cooling. However, the primary contact area of the tool and the cutting zone, which participates in heat generation, remained unchanged. Thus, it can be concluded that the simplified geometry may cause local deviations in the thermal fields, but this does not affect the general conclusions drawn from the simulation.

The simplified models were exported as STL files and imported into AdvantEdge. For end mill, the finite element mesh was generated using the advanced meshing module of the software. The following mesh parameters were applied: maximum tool element size of 1 mm, minimum element size of 0.1 mm, mesh grading factor of 0.5, and curvature safety coefficient of 3.

The workpiece model was not generated in SolidWorks. Instead, the built-in Create/Edit Standard Workpiece option available within AdvantEdge was used. Both tool and workpiece materials were selected from the program’s internal material libraries. The AISI 4340 steel was chosen as the workpiece material, while the carbide tool with a TiAlN coating was selected as the cutting tool material. The classical Johnson–Cook constitutive material model [32] was selected to describe the behavior of the workpiece material. The Lagrangian model was used to define the boundary conditions of the simulation. The friction at the chip–tool interface was described by a Coulomb friction model.

For the workpiece, the finite element mesh was generated using advanced meshing options, with the following parameters: a maximum element size of 2 mm and a minimum element size of 0.15 mm. A mesh grading factor of 0.5 and a curvature safety coefficient of 2.5.

After importing the geometry and defining all input parameters, the simulation was executed using the simplified end mill (in Demonstration mode). The cutting temperature was defined as the primary output variable for evaluating the simulation performance. By using the Tecplot post-processing module, the simulation results can be visualized from different perspectives. Also, simulation results can be compared by selecting the Multi-Project Display option.

3. Results and Discussion

During the research, several models were developed to calculate the temperature values in the cutting zone during the milling process. The results were obtained through experimental measurements, a three-factor mathematical model, and simulations performed in AdvantEdge. The obtained values are presented in Table 4. For better clarity, the following abbreviations for the models were introduced:

Table 4.

Results obtained from the experiment, factorial model (with and without interaction effects), and AdvantEdge simulations, including the percentage error E for temperature (T).

F.M.1—model obtained based on the three-factor design, without interaction effects between the factors

F.M.2—model obtained based on the three-factor design, with interaction effects between the factors

Adv.Edge—model obtained through simulations in AdvantEdge

The experimental values are denoted by the abbreviation Exp.

Along with the results presented in Table 4, it should be noted that in experimental thermographic measurements, the overall uncertainty can originate from several factors. Small variations in the surface emissivity can introduce errors of up to ±2–3%. The accuracy of the thermal camera can vary by ±1 °C or ±2% of the measurement. Reflections and the viewing angle further increase uncertainty, especially for short cutting lengths.

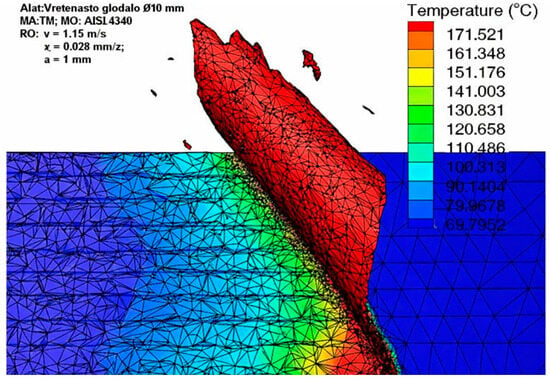

The chip formation at the moment when the cutter tooth engages the workpiece (for improved visibility, the tool display is turned off) for the regime v = 1.15 m/s, sz = 0.028 mm/z, a = 1 mm was illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Display of temperature distribution during chip formation.

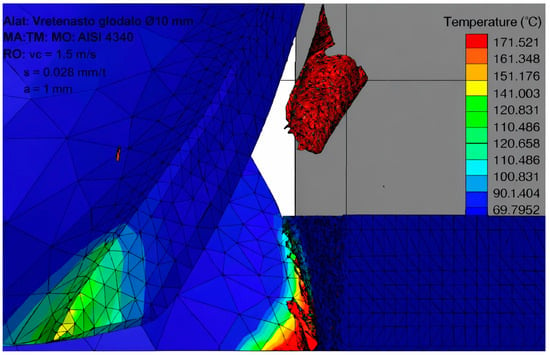

Figure 7 shows the same stage of the process with the tool display enabled.

Figure 7.

Temperature distribution during the engagement of the milling cutter with the workpiece.

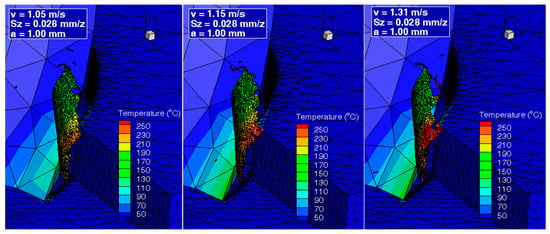

Figure 8 shows the displays of simulations that were recorded at the same time intervals, with the same zone selected for comparison. The chosen zone is the zone in which the tooth exits from the contact with the workpiece. It can be noticed that the tooth top is in simulation with the biggest cutting speed in the red zone, which means that in this case the temperature is the highest (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Comparison simulations with different cutting speeds.

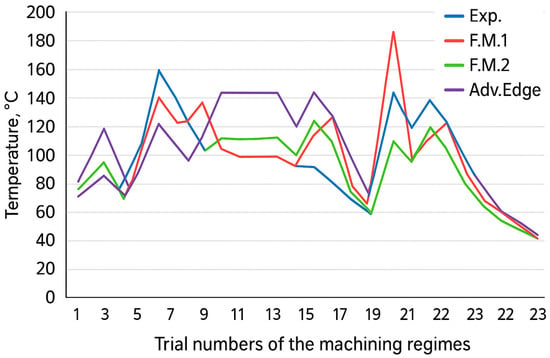

The analysis was performed in the form of a diagram (Figure 9), where the abscissa in the coordinate system represents the corresponding trial numbers of the machining regimes from Table 4, while the ordinate shows the temperature values in the cutting zone.

Figure 9.

Graphical representation of the obtained values of temperature in the cutting zone.

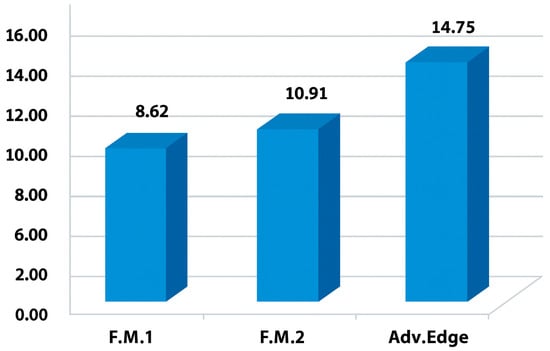

In addition to the diagram in Figure 9, a histogram (Figure 10) is presented, illustrating the average percentage error for each model.

Figure 10.

Histogram of the mean percentage error for each model.

Based on the analysis of the obtained results, it can be observed that in the experiment, the temperature increases by 10–20 °C when the cutting speed is raised from 1.05 to 1.31 m/s. The F.M.1 and F.M.2 and the simulation show a higher increase (21–23 °C) compared to the experiment. The observed increase in cutting temperature with cutting speed is consistent with trends reported in milling studies. Bergs and Liu [9] reported a comparable dependence of tool temperature on cutting speed when infrared thermography was applied in milling, with temperature levels of the same order of magnitude under dry cutting conditions. Similar trends have also been reported for milling of carbon steels [23], confirming that cutting speed remains one of the dominant factors governing thermal load in the cutting zone.

In the experiment, increasing the feed per tooth from 0.021 to 0.035 mm/z does not lead to a temperature rise; instead, it results in a reduction of 16–29 °C. F.M.1 predicts a slightly larger decrease (−34 °C), while F.M.2 (−18 °C) and the simulation (−21 °C) follow the experimental trend more closely. These results indicate that, under the investigated cutting conditions, an increase in feed per tooth does not necessarily lead to higher cutting temperatures. Similar observations of a non-monotonic influence of feed per tooth on cutting temperature have been discussed in temperature modeling studies based on fuzzy approaches [3].

In the experiment, increasing the depth of cut from 0.50 to 2.00 mm causes a substantial temperature rise (+86 °C). The models and simulations differ: F.M.1 significantly overestimates this effect (+125 °C), F.M.2 (+48 °C) underestimates it, while the simulation (+65 °C) predicts a moderately smaller increase than the experiment. A strong increase in cutting temperature with increasing depth of cut has been widely reported in milling studies. Similar trends have been observed in experimental and numerical investigations, where depth of cut was identified as a dominant factor governing thermal loads in the cutting zone [13]. At the same time, numerical milling studies have shown that FEM predictions may deviate in magnitude from experimental measurements depending on modeling assumptions and thermal boundary conditions [8,11], which is consistent with the differences observed between the models and simulations in the present study.

From the histograms, it can be seen that the model obtained based on the three-factor design without factor interactions shows the lowest deviation error (~8.6%), while a slightly worse value (~10.9%) is given by the three-factor model with factor interactions. Simulations obtained in AdvantEdge yielded an error of around 15%. As mentioned before, the Demonstration mode was used due to limitations of the available license, which did not allow the use of the full standard version. Although this mode may be less accurate, the simulations still allow the assessment of temperature with an average error of about 15%, which is sufficient for comparison with the experimental results.

Based on Table 4, it can be seen that the largest deviations between the experiment and the simulations (greater than 20%) occur mainly under extreme cutting conditions, particularly when the depth of cut reaches 2.0 mm and when a higher feed per tooth is combined with increased cutting speed. In these regimes, the real milling process produces much higher temperatures because of stronger material plastic deformation, intensified friction, and irregular chip formation. The FEM model, however, does not fully capture the rapid increase in contact length, heat accumulation, and frictional behavior that occurs at large undeformed chip thickness. As a result, the simulated temperatures are noticeably lower than the experimental ones, especially in trials 18 and 24, where the depth of cut is at its maximum.

Another group of cases with >20% error appears when the feed per tooth is high (0.035 mm/z). Here, the simulations tend to underestimate the temperature rise because the material model reduces flow stress too aggressively at large strain rates and temperatures. This suppresses the heat generation that is observed experimentally. Likewise, combinations of high cutting speed and high depth of cut generate the most heat in practice, but the FEM thermal model has a limited ability to reproduce this strong nonlinear growth. Consequently, these specific regimes produce the highest discrepancies, while moderate cutting conditions show good agreement between experiment and simulation.

The comparison between experimental measurements and FEM predictions indicates that the numerical model reproduces the overall temperature trends, while larger deviations occur at higher cutting parameters. Similar behavior has been reported in numerical–experimental studies on milling processes [13,17], where FEM simulations show increased prediction errors at large depths of cut and high cutting parameters due to constitutive and thermal modeling limitations.

In addition to the analysis of cutting zone temperature results, it is important to note the differences in the methods of measuring temperature. Several trial tests with different cutting lengths were conducted using a thermal imaging camera. It was observed that measurements for cutting lengths below 50 mm were unreliable due to the short contact time between the tool and the workpiece, insufficient thermal stabilization, and the greater relative influence of reflections and viewing angle. For this reason, a cutting length of 50 mm was chosen for experimental measurements.

4. Conclusions

The aim of the research was to simulate thermal phenomena during milling using the finite element method. Experimental measurements of temperature in the cutting zone were conducted during milling with an end mill. Temperature recording during the experiment was performed using a thermal imaging camera. The experiment was conducted according to a second-order three-factor design. Models without interactive effects and models with interactive effects for temperature in the cutting zone during milling were developed separately.

According to the three-factor experimental design, simulations in AdvantEdge were created for a carbide end mill, followed by analysis of results obtained from the experiment, three-factor design, and simulations. Based on the analysis, several key conclusions can be drawn. The model based on the three-factor design without interactive effects provides the lowest average percentage error, while the model with interactive effects shows slightly worse results. The analysis shows that simulations created in AdvantEdge, although showing higher average percentage errors compared to both three-factor models, can reliably be used for predicting and controlling cutting zone temperature during milling.

The conducted research and results show that by modeling and simulating the milling process using the finite element method, it is possible to predict cutting zone temperature using the AdvantEdge software package. Comparison with experimental results confirmed that cutting temperature can be predicted without experiments, with deviations in AdvantEdge results being less than 15%.

It can be observed that the depth of cut has a strong influence on temperature increase (the strongest among the examined parameters). The next most significant parameter is the cutting speed, followed by the feed per tooth, which can be explained by the relatively narrow range of cutting speeds used in the measurements.

The results of thermographic measurements and simulations provide insights into the thermal loading of cutting tools under various cutting parameters. This information can help in the selection of tool materials, geometries, and coatings aimed at optimizing tool life and overall performance. Simulations enable temperature prediction under real milling conditions, contributing to the optimization of process parameters (cutting speed, feed per tooth, and depth of cut) in order to reduce tool wear and improve both productivity and machining quality. The combination of experimental and simulation results allows for rapid evaluation of new tools and processes without the need for costly and time-consuming experiments, thereby reducing time and overall costs.

Future research in the area of process modeling can be divided into several directions: implementation across various types of cutting operations, investigation of a larger number of output performance indicators and their comparison with experimental tests, as well as overcoming problems arising from the aforementioned limitations.

Future research should also explore the application of FEM-based thermal modeling in the field of agricultural engineering, particularly in the optimization of machining processes of components used in agricultural machinery and equipment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M. and R.D.; methodology, A.M. and M.K.; software, A.M.; validation, M.R., J.J. and R.D.; formal analysis, J.J. and M.R.; investigation, M.K. and R.D.; resources, A.M.; data curation, A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.J. and M.R.; writing—review and editing, R.D. and M.K.; visualization, A.M.; supervision, R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, grant number 451-03-136/2025-03/200132.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development, and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, and these results are part of the Grant No. 451-03-136/2025-03/200132, with the University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Technical Sciences, Čačak.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CCD | Central Composite Design |

| FEA | Finite Element Analysis |

| FEM | Finite Element Modeling |

References

- Guimarães, B.; Rosas, J.; Fernandes, C.M.; Figueiredo, D.; Lopes, H.; Paiva, O.C.; Silva, F.S.; Miranda, G. Real-Time Cutting Temperature Measurement in Turning of AISI 1045 Steel Through an Embedded Thermocouple—A Comparative Study with Infrared Thermography. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin, O.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Larour, P.; Parareda, S.; Frómeta, D.; Hammarberg, S.; Kajberg, J.; Casellas, D. A Particle Finite Element Method Approach to Model Shear Cutting of High-Strength Steel Sheets. Comput. Part. Mech. 2024, 11, 1863–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelkrim, F.; Abdelkrim, M.; Belloufi, A.; Tampu, C.; Bogdan, C.; Gheorghe, B. Multi-Input Fuzzy Inference System Based Model to Predict the Cutting Temperature When Milling AISI 1060 Steel. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2023, 21, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeni, A.; Cappellini, C.; Attanasio, A. Finite Element Simulation of Tool Wear in Machining of Nickel–Chromium-Based Superalloy. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Material Forming (ESAFORM 2021), Liège, Belgium, 14–16 April 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamuła, B. Temperature Measurement Analysis in the Cutting Zone During Surface Grinding. J. Meas. Eng. 2021, 9, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidas, E.; Ayvar-Soberanis, S.; Laalej, H.; Fitzpatrick, S.; Willmott, J.R. A Comparative Review of Thermocouple and Infrared Radiation Temperature Measurement Methods During the Machining of Metals. Sensors 2022, 22, 4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cichosz, P.; Karolczak, P.; Waszczuk, K. Review of Cutting Temperature Measurement Methods. Materials 2023, 16, 6365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, M.; Zhao, S. Reduced Computational Time in 3D Finite Element Simulation of High-Speed Milling of 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2021, 25, 558–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergs, T.; Liu, H. A Novel Approach to Milling Cutter Temperature Analysis with Cutting Fluid Consideration. CIRP Ann. 2025, 74, 119–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M. Finite Element Simulation of Metal Cutting of Aluminum Using Johnson-Cook Damage Model and Shear Failure Model. Mansoura Eng. J. 2020, 42, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, M.; Ren, F. Finite Element Modeling of High-Speed Milling 7050-T7451 Alloys. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 43, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.E.F.; Gregório, A.V.L.; de Jesus, A.M.P.; Rosa, P.A.R. An Efficient Methodology Towards Mechanical Characterization and Modelling of 18Ni300 AMed Steel in Extreme Loading and Temperature Conditions for Metal Cutting Applications. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepanraj, B.; Senthilkumar, N.; Hariharan, G.; Tamizharasan, T.; Bezabih, T.T. Numerical Modelling, Simulation, and Analysis of the End-Milling Process Using DEFORM-3D with Experimental Validation. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5692298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, P.; Gupta, K. A Review on the Machinability Enhancement of Metal Matrix Composites by Modern Machining Processes. Micromachines 2024, 15, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davoudinejad, A.; Tosello, G.; Parenti, P.; Annoni, M. 3D Finite Element Simulation of Micro End-Milling by Considering the Effect of Tool Run-Out. Micromachines 2017, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Gupta, M.K.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Kiran, M.; Khanna, N.; Krolczyk, G.M. Application of Measurement Systems in Tool Condition Monitoring of Milling: A Review of Measurement Science Approach. Measurement 2022, 199, 111503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, X.; Gao, C.; Lin, Z.; He, B. 3D Finite Element Simulation for Tool Temperature Distribution and Chip Formation During Drilling of Ti6Al4V Alloy. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 5155–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-T.; Pham, H.T.; Doan, H.K.; Asteris, P.G. Experimental and Computational Investigation of the Effect of Machining Parameters on the Turning Process of C45 Steel. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2025, 17, 16878132251318170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, D.Y.; Der, O.; Manjunath Patel, G.C.; Giasin, K.; Ercetin, A. State-of-the-Art Review of Energy Consumption in Machining Operations: Challenges and Trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 224, 116073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagri, N.K.; Jain, N.K.; Petare, A.; Das, S.R.; Tharwan, M.Y.; Alansari, A.; Alqahtani, B.; Fattouh, M.; Elsheikh, A. Investigation on the Performance of Coated Carbide Tool During Dry Turning of AISI 4340 Alloy Steel. Materials 2023, 16, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, G.; Cheng, X.; Yang, X.; Xu, R.; Zhang, H. Cutting Performance Evaluation of the Coated Tools in High-Speed Milling of AISI 4340 Steel. Materials 2019, 12, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, H.; Jouini, N.; Ghani, J.A.; Rasani, M.R.M. A Review of High-Speed Turning of AISI 4340 Steel with Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL). Coatings 2024, 14, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldin, V.; da Silva, L.R.R.; Davis, R.; Jackson, M.J.; Amorim, F.L.; Houck, C.F.; Machado, Á.R. Dry and MQL Milling of AISI 1045 Steel with Vegetable and Mineral-Based Fluids. Lubricants 2023, 11, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhamad, S.S.; Ghani, J.A.; Juri, A.; Che Haron, C.H. Dry and Cryogenic Milling of AISI 4340 Alloy Steel. J. Tribol. 2019, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- ISCAR Cutting Tools. Tool Family Information. ISCAR eCatalog. 2025. Available online: https://www.iscar.com/eCatalog/Family.aspx?fnum=2517&mapp=ML&app=59&GFSTYP=M (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- FLIR Systems. FLIR Infracam SD Manual; FLIR Systems: Wilsonville, OR, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/354975559/Flir-Infracam-Sd-Manual (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mitrović, A. Modeling of Cutting Process. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2016. Available online: https://www.cris.uns.ac.rs/DownloadFileServlet/Disertacija147220887274529.pdf (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Mejia, D.; Moreno, A.; Ruiz-Salguero, O.; Barandiaran, I. Appraisal of Open Software for Finite Element Simulation of 2D Metal Sheet Laser Cut. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2017, 11, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magomedov, I.A.; Sebaeva, Z.S. Comparative Study of Finite Element Analysis Software Packages. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1515, 032073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Third Wave Systems. AdvantEdge User’s Manual; Third Wave Systems: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2016; Available online: https://thirdwavesys.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/AdvantEdge-7.2-Released.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Tecplot, Inc. Tecplot 360: User’s Manual, 2024 Release 1; Tecplot, Inc.: Bellevue, WA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://platform.softwareone.com/files/product-media-files/PCP-8137-4897/092baf2e90b40d3d32f4491258100c220016c68a2457f90efdbba791879a600a.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A Constitutive Model and Data for Metals Subjected to Large Strains, High Strain Rates, and High Temperatures. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983; pp. 541–547. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.