Abstract

Shielding gas flow in metal Laser Powder Bed Fusion (PBF-LB/M) removes ejecta and byproducts from the build plate and the optical path, preventing laser interference and loss of part quality. Previous research conducted on an EOS M290 used Magnetic Resonance Velocimetry (MRV) to resolve the three-component, three-dimensional flow field and identified a region of recirculation below the lower vent. The present work demonstrates the correction of this recirculation through practical chamber modifications: raising the build platform and optical assembly, and redesigning the recoater and the lower inlet to reflect the new build plate position. MRV was leveraged to generate flow distribution maps and velocity profiles of the modified configuration, showing a marked change in the overall flow field. Plate scans across the build area characterized the impact of gas flow improvements on process response. Specimens from the original configuration showed progressively shallower melt pools toward the vent, whereas those from the modified configuration exhibited a ~10% higher average melt pool depth in the region most affected by prior recirculation. Qualification artifacts built under both conditions provided preliminary evidence of improved part performance via enhanced gas flow distribution. These results highlight potential benefits of uniform gas flow distribution across the build plate through simple EOS M290 chamber modifications.

1. Introduction

The presence of a shielding gas flow in Laser-based Powder Bed Fusion of Metals (PBF-LB/M) systems plays an important role in the overall build process, as it not only promotes an inert environment but also removes byproducts and contaminants from the build plate to prevent interference with the laser path [1,2,3]. Failure to do so can result in defects and poor part quality due to a shift in the focal point, as well as laser attenuation and scattering, as observed by Ladewig et al. [4] in an EOS M280. In a study performed by Shen et al. [5] on an EOS M290, it was demonstrated that gas flow velocities below 1 m/s could be associated with large and irregular lack-of-fusion defects. The correlation between flow characteristics and porosity was also explored by Ferrar et al. [6], who utilized an MTT ReaLizer SLM 250 to evaluate multiple flow configurations. Their findings suggest that constant, uniform gas flow across the build plate leads to denser parts, regardless of their location; similar results were obtained by Yang et al. in their investigation of large scale PBF-LB/M systems [7]. Single-track plate scan experiments, coupled with detailed cross-sectional analysis, have further demonstrated that small changes in local process conditions can produce measurable differences in melt pool depth and width across a build area [8,9,10]. A similar study by Reijonen et al. [11] also aimed to correlate gas flow velocity with melt pool geometry using an SLM 125 HL. They concluded that increased part porosity and shallow melt pools could be attributed to the obstruction of the laser beam caused by byproducts of the vapor plume due to inadequate gas flow; such a phenomenon has been observed before and is well established in the literature [12,13]. A similar conclusion was reached by Deisenroth et al. [14], who solely focused on the variability in melt pool width when exposed to a variable-velocity jet across the build plate of the NIST Additive Manufacturing Metrology Testbed (AMMT). It was observed that lower velocities were associated with higher variability in width, whereas higher velocities resulted in consistent characteristics, such as the shape, width, and depth of the melt pools. Analogous to these findings, Zou et al. [15] determined that, in the case of fiber laser welding, laser power and weld depth could be greatly improved by removing the resulting plume with a supersonic jet. Additional experimental and review studies have reached similar conclusions, emphasizing that sufficiently fast and spatially uniform shielding gas flow is required to limit laser attenuation, spatter accumulation, and defect formation in PBF-LB/M components [16,17,18,19,20,21]. Studies on process variation, large scale systems, and alternative inlet designs also show that maintaining consistent, well directed gas flow across enlarged build plates is essential to achieve uniform density and mechanical response, and that modified inlet and outlet geometries can significantly enhance spatter removal [22,23]. These findings are consistent with investigations of large format and dual-inlet configurations, where improved gas field design was shown to reduce positional sensitivity of part quality and to mitigate powder bed disturbance [24,25].

Moran et al. [26] evaluated defect formation across the entire build plate of an EOS M290 and identified higher defect volume in the region closest to the inlet vent. It was observed, through CFD simulation, that gas flow recirculation occurred in this region, and they concluded that the formation of eddies was the main factor behind the high volume of defects. A previous study, Elkins et al. [27], focused on the experimental analysis of flow distribution within the EOS M290 through Magnetic Resonance Velocimetry (MRV), revealed that this region of recirculation was directly related to the step (in the Z-axis) separating the inlet vent from the build plate. An additional vent was introduced to create a uniform flow field, and single scan tracks were produced using both the original and the modified configurations. It was found that, without the extra vent, melt pools near the inlet vent were shallower than others; on the other hand, using the extra vent resulted in more consistent melt pool depth. These results demonstrated once again the importance of maintaining a unidirectional flow field to prevent the formation of anomalies. Additionally, it was theorized that, in this specific case, the gas flow distribution could be improved significantly by removing the separation (in the Z-axis) between the inlet vent and the build plate surface, since that was the main contributor to the formation of the backward-facing step flow observed near the vent. Similar conclusions regarding the detrimental role of gas recirculation, stagnation zones, and non-uniform gas speed have been reported in chamber-scale measurements and simulations, which document large spatial variations in velocity and associated regions of soot and condensate accumulation over the build plate [28,29,30].

This paper expands on the last hypothesis by describing experiments in an EOS M290 which was modified to eliminate the backward-facing step flow, thereby improving shielding gas flow distribution and promoting the removal of soot and spatter particles. Modifications included raising the bottom of the build chamber, including the build platform, to align with the bottom of the lower inlet vent. In addition, the recoater and laser optics were raised by the same amount. The purpose of these changes, as well as the main goal of this research, was to improve gas flow distribution and evaluate its effects on melt pool depth and part quality. As with Elkins et al. [27], MRV was also leveraged to resolve the three-dimensional flow field of the modified system and ensure an even distribution of the shielding gas flow across the build plate. Despite other techniques having been used before for this type of work [31], and MRV not being the primary focus of this study, this approach was selected because of the experience of the authors with this method, the prior MRV results using the original EOS M290 flow configuration with which the current work could be compared, and MRV’s ability to provide full three-dimensional and three-component velocity measurements throughout the entire chamber. Alternative experimental flow measurement methods such as point-wise pitot–static and hot-wire measurements were considered here but were not used extensively since the MRV measurements provided the necessary data to verify the removal of the recirculation region. In addition, implementation of MRV for the study of flow overcomes several of the limitations generally associated with characterization of the flow field, such as the requirement for optical access or usage of tracer fluids, in the case of optical techniques, or the usage of invasive devices that require precise positioning and dense datapoint arrays, in the case of point-wise instruments. Forthcoming work from our group will provide a framework for making flow qualification measurements within the actual chambers of PBF-LB/M machines using a portable and automated system with pitot–static and hot-wire measurements. It is expected that this deployable system will provide significant insight into the gas flow fields within commercial systems so that the requirements for qualified flow within each system can be examined and eventually provided. Beyond the EOS M290 studies highlighted above, other efforts have underscored the value of combining build log analysis, optical monitoring, and dedicated test builds to link gas flow conditions to melt pool signatures and defect formation, reinforcing the need for quantitative chamber characterization as a prerequisite for robust process qualification [32,33].

In the present study, once the gas flow distribution was verified to have removed the flow recirculation region, plate scans across the build area characterized the impact of gas flow improvements on melt pool depths, similar to Reijonen et al. [11] and Deisenroth et al. [14]. Significant improvements in melt pool depth variation by location in the build chamber, as well as measured melt pool depth variability, were demonstrated, providing evidence, similar to Qin et al. [1] and Hoppe et al. [2], that improved flow has the potential to have a positive influence on part quality. As a first step in demonstrating enhanced part quality due to flow improvements, test artifacts [34] were printed and examined as part of the present body of work using the original and modified EOS M290 configurations for the evaluation of anomaly formation, as exemplified by Shen et al. [5], Ferrar et al. [6], and others. This test artifact, described in previous studies by Taylor et al. [34,35] and Singh et al. [36], allowed for a more holistic evaluation of part performance. Recent work on defect structure process maps and predictive process mapping has likewise used melt pool geometry, porosity, and defect populations as metrics to delineate processing windows and to assess sensitivity to process perturbations, including gas flow variations [37,38]. In the present study, only single artifacts were printed to compare the two flow conditions, and these holistic measurements (microstructure, porosity, and mechanical properties) allowed potential improvements to be highlighted after correcting the flow distribution. It should be emphasized that, since only one artifact for each flow condition was compared, much more work is required and forthcoming to quantify the benefits from improved gas flow within this machine and across many PBF-LB/M systems. To summarize, the present study seeks to correct a problematic gas flow region within the EOS M290 through the implementation of targeted modifications. To demonstrate the effects of improved gas flow distribution on part quality, a comprehensive study and analysis of melt pool depths was first used as a proxy for quality. Finally, a complex three-dimensional test artifact was printed using both flow configurations and holistically compared, providing preliminary evidence of potential part quality improvements due to improved flow. These preliminary results were encouraging, and the authors intend this work to serve as a foundation for more extensive work in the future focused on establishing the causal relationships between flow and part quality, including dimensional accuracy, microstructural architecture, surface roughness, mechanical properties, and more. The following includes further details of this investigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chamber Modifications

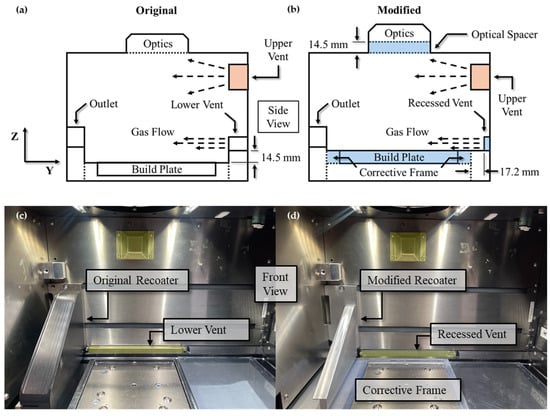

Previous research [27] demonstrated that the primary source of flow-related issues on the EOS M290 was the machine’s backward-facing step near the gas flow inlet. Five modifications were made to the system in an effort to remove the aforementioned characteristic. The first one consisted of raising the build platform by 14.5 mm from its original position to align with the bottom of the inlet vent’s exit, effectively removing any vertical step as flow traverses across the build area. For the second one, the position of the optics was also raised by 14.5 mm to ensure that the same focal plane was maintained and circumvent other optical modifications/calibrations. The third one involved replacing the original recoater with a modified version capable of adjusting the height of the blade to account for the raised platform. The fourth change required replacing the lower inlet vent with a modified version that was recessed 17.2 mm in depth from its default configuration to become flush with the back wall of the chamber and allow for additional development length of gas flow prior to reaching the build area. The fifth and final modification consisted of raising the build chamber floor, referring to the area surrounding the build plate, to effectively create a flat surface that avoids drop-off zones at the extent of the build plate. This was achieved by placing a frame-like fixture, referred to as the corrective frame, around the build platform and pressing down to ensure that the component rested flat against the bottom of the chamber. A modified method to level the starting layer was also conceived, which consisted of the use of a Digi-Pas DWL-1500XY digital level (Digipas Technologies, Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) to ensure the platform and inlet were leveled to each other. The modified recoater then allowed for the recoater blade to be adjusted according to the leveled position. Details of each modification are included as Supplementary Materials. Additionally, STEP files, detailed pictures and engineering drawings can be found on the DRIVE AM website (driveam.org/shielding-gas-flow-optimization-for-eos-m290); for additional details, the authors may be contacted directly through email.

The changes to the system can be seen in Figure 1, which displays key geometric dimensions on the side-view illustrations at the top (Figure 1a,b), and more clearly depicts internal differences between both configurations in Figure 1c,d, specifically showcasing changes in the recoater, inlet vent and the addition of the corrective frame. The scan head was removed from the system to manually measure the diameter, depth, and position of the threaded holes and alignment pins. The measured features were replicated in SolidWorks 2024 (Dassault Systèmes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France), and a spacer ring was created to offset the EOS M290 scan head. A similar approach was utilized to measure existing mounting screws on the recoater, including those of the traversing mechanism. With these measurements, a mounting plate was created to connect the railing mechanism with the new adjustable recoater. The geometry of the new design was based on the slider used for the Aconity MIDI+ (Aconity3D GmbH, Herzogenrath, Germany), which provided a lighter frame and facilitated height adjustment of the blade through thumb screws located on the side. All parts were first printed on a Stratasys NEO 450 from Watershed resin (Stratasys, Ltd., Eden Prairie, MN, USA) as prototypes, and a design was later finalized and machined out of Aluminum 6061. As for the inlet nozzle, additional care was taken to ensure the staggered pattern of the orifices was replicated correctly. A caliper and measuring tape were used initially to determine the height, length, and protrusion distance of the vent. Afterwards, a front-view picture of the pattern was taken and imported into SolidWorks to use as a reference. The picture was scaled to match the actual dimensions of the vent, after which a sketch was overlayed to create the staggered pattern using SolidWorks’ Linear Pattern feature. Given that the protruded nozzle tapered outwards over a depth of 17.2 mm, the new design had to be modified slightly to account for the smaller surface area. This resulted in a total of eight orifices being removed from the side edges to provide enough space for the mounting holes used to hold the nozzle in place. As with the recoater parts, the modified vent was fabricated with Watershed resin on a Stratasys NEO 450. In this case, however, the authors decided to use the resin component as the final part. Lastly, to ensure that the rest of the platform was level with the increased height of the build plate, a corrective frame was designed to go around the build plate to remove gaps in the surrounding areas. This component was also built on a Stratasys Neo 450 out of Watershed resin and, eventually, machined out of Aluminum 6061.

Figure 1.

(a) Side-view illustration of the original chamber configuration; (b) side-view illustration of the modified chamber configuration, highlighting component modifications (excluding recoater); (c) front view of original chamber configuration, with upper and lower vents highlighted in yellow; (d) front view of modified chamber configuration, with upper and lower vents highlighted in yellow.

These modifications were also implemented on a scaled-down model of the machine, which was developed with the sole purpose of performing MRV tests to quantify changes in the flow field. Dimensional analysis of the slow gas flow in most of the build chamber, except very close to the melt pool where metal vaporization is occurring, shows that dimensionless velocities (velocity ratios) depend on the Reynolds number. Since the current experiment is investigating this slow flow which is responsible for sweeping soot and other contaminants away from the melt pools, MRV measurements were performed using a 1/3 scale replica of the EOS M290 build chamber with the necessary flow rate to match the Reynolds number in the full scale M290 chamber. The model was fabricated via vat photopolymerization in a Stratasys Neo 450 3D printer (Stratasys, Eden Prairie, MN, USA) using DSM Somos Watershed 11122 polymer (DSM, Heerlen, The Netherlands). Since the model accurately matches the geometry of the M290 build chamber and the flow is at the same Reynolds number, the velocity ratios between the two flows match. In this case, the local velocities in the build chamber can be normalized by the mean bulk velocity in the supply tube to the chamber, and the MRV measurements are representative of the full-scale velocities when multiplied by the ratio of the full scale to 1/3 scale inlet velocity. An in-depth explanation of the process used to calculate and match the Reynolds number within the EOS M290 is provided by Elkins et al. [27]. To ensure flow rate conditions in the full-scale configuration remained equivalent to those of the MRV models, flow meter measurements—captured at the supply line of the system—were collected and evaluated throughout the testing period. MRV measurements of the scaled-down system were taken on a commercial MRI machine (3 Tesla GE Signa, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) located in Mayo Clinic’s Opus Imaging Research Building at Rochester, MN. Additional details regarding the working principles of MRV, calculation of velocity, estimation of uncertainties and limitations of the technology are discussed extensively by Elkins & Alley [39].

2.2. Beam Measurements

Given the repositioning of the optics atop the EOS M290 chamber, beam measurements were acquired before and after the modifications to ensure that laser characteristics were preserved throughout the entire process. In both instances, Haas’s Laser Beam Waist Analyzer Camera (BWA-CAM) was utilized in tandem with the Beam Waist Analyzer Software (BWA-PRO) (Haas Laser Technologies Inc., Flanders, NJ, USA) to analyze and monitor beam characteristics, such as waist size, spatial profile, and focus shift, among other properties. The procedure itself consisted of adjusting the position of the BWA-CAM until achieving vertical alignment with the machine’s own integrated beam guide, activating the laser at various intensities (25 W, 50 W, 100 W), and visualizing the measurements in the BWA-PRO, which was then used to export data and generate test reports. This methodology was provided by the manufacturer’s manual and adapted to the EOS M290.

2.3. Plate Scans

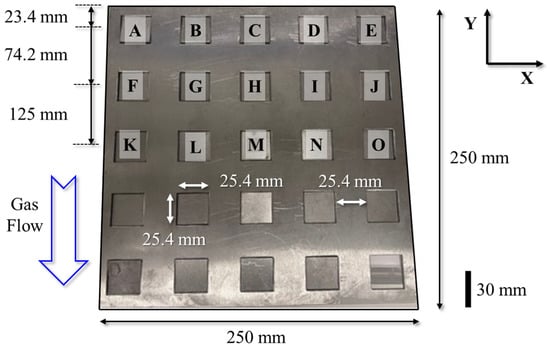

Single-layer scans were performed on fifteen 25.4 × 25.4 × 3 mm SAE 316L plates, which were placed around the build area to form a grid of five columns and three rows, where each plate had a separation of 25.4 mm from the others. The plates were labeled from A to O, starting with the top left corner and continuing from left to right and top to bottom, as seen in Figure 2, and scanned using the system’s process laser. The row from A to E, also denominated as the first row, is the one closest to the inlet nozzle, while the third row (K–O) is the one furthest away from the vent and nearest to the outlet. The rows had a separation of 23.4, 74.2 and 125 mm to the inlet-side edge of the plate, as measured from the center of each row. Track patterns, similar to those described in Elkins et al. [27], were used here. The track pattern analyzed in the current work consisted of 70 vectors with a length of 5 mm, scanned on each plate with the tracks stacked in the direction of the primary gas flow, a hatch spacing of 0.14 mm and alternating scan direction.

Figure 2.

Picture depicting plate layout, denomination and dimensions.

The scans were performed with the EOS M290’s integrated scanner—intelliSCAN III 20 (SCANLAB, Puchheim, Germany)—at a constant power of 280 W and laser speed of 1200 mm/s. The tracks were scanned one plate at a time, starting on the third row and finishing on the first row. An in-depth description of this setup is provided by Elkins et al. [27]. An attempt was made in said study to demonstrate the effect of improved gas flow in an area of poor flow distribution through the utilization of an extra vent meant to increase flow and thereby influence proper ejection of melting byproducts (condensate and soot). As expected, the results showed improvements in melt pool depths in the region of interest; however, the analysis only focused on one area of the build plate, while this work aims to improve flow across the entire plate. Therefore, this study expands the evaluation to the entire first row for a more comprehensive analysis, as this region of the plate is fully located within the recirculating gas flow. Standard deviation per plate was calculated based on the measured individual melt pool depths of the scan tracks and used to determine melt pool stability across gas flow configurations and plate locations.

Once the scanning of the plates was complete, the samples were sectioned perpendicular to the direction of the vectors with a Brilliant 220 8” high-speed water-cooled saw (ATM Qness GmbH, Mammelzen, Germany). The cuts were made at the midpoint of the vectors in an attempt to avoid irregularities in melt pool shape and size that could potentially form near the start and end of each track. The specimens were then ground using a 3-step process involving SiC paper of 320, 600 and 1200 grit, followed by polishing performed with a Saphir 530 automated polisher (ATM Qness GmbH, Mammelzen, Germany) equipped with a cloth polishing pad. Having achieved a polished finish, an etching reagent was then applied to the sectioned plates to reveal the melt pools. A Keyence VHX-7000 (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was used to image the melt pools at a resolution of 100X, allowing for individual measurements of each melt pool through the implementation of measurement features included in Keyence software (VHX-7000 Software, version 1.3). These measurements are estimated to have an error of ±3 μm based on operator uncertainty.

2.4. Fabrication of Qualification Test Artifact

In addition to plate scans (performed without powder and on 316L steel plates) and for the purposes described previously (i.e., to provide preliminary evidence of part quality improvements via gas flow improvements) qualification test artifacts (QTAs), described by Taylor et al. [34,35], and Singh et al. [36], were built using Scalmalloy (APWorks, Munich, Germany) to test porosity and the proper removal of ejecta for a build where powder is used. Scalmalloy is a high-strength aluminum alloy developed specifically for additive manufacturing and is being considered for use across various industries for its high tensile and yield strength, as well as its corrosion resistance properties. It was used here mainly because it was scheduled for use in the machine during the flow configuration modifications and would allow for the holistic part evaluations required for this study. Further, by fabricating a complicated test part using a relatively light metal alloy, the artifact provides a comprehensive analysis on the effects of gas flow over a complex geometry, which includes numerous features aimed at qualifying process conditions. For this same reason, the artifact has been used, and continues being used, in other studies [35,40] for rapid research evaluation. Thus, the QTA with its multiple features—such as thin walls, overhangs, thru-holes, etc.—provides additional insight that simpler geometries, such as cubes or cylinders, would fail to convey.

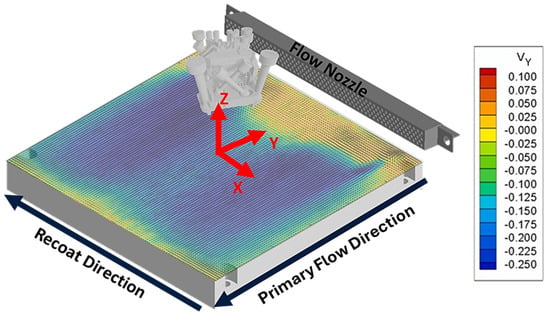

One test artifact was manufactured on the build plate in the position shown in Figure 3, which also displays contours of the dimensionless Y-component of velocity, VY, at the height closest to the build plane in the Elkins et al. [27] MRV. Recall from the earlier discussion that dimensionless velocities should be the same in the full-scale and 1/3 scale flows. The positive direction of the Y-axis goes towards the inlet nozzle, thus indicating that forward-facing flow is denoted by negative values. As such, the yellow/orange contours indicate areas where the gas flows backwards toward the inlet vent, also known as regions of ‘bad flow’ or recirculation. The artifacts were placed in this region to compare changes in porosity using the original and modified configurations. A unique ID was given to each artifact: “OEM” refers to the artifact fabricated with the original configuration, while “MOD” refers to the one manufactured with the modified configuration. To ensure consistency between builds, powder from the same batch was used in both instances. Process parameters were configured per the manufacturer’s recommended settings and are listed in Table 1. A batch analysis report was provided by the manufacturer upon delivery to certify powder characteristics. Based on this datasheet, powder properties were as follows: oxygen concentration of 0.04%, apparent density of 1.49 g/cm3, flowability of 10.6 s/50 g and a particle size distribution defined by d10 = 29 µm, d50 = 43.8 µm and d90 = 65.4 µm.

Figure 3.

Setup of the test artifact build depicting its position relative to previously identified gas flow anisotropies. The color contours represent the normalized Y component of velocity in a plane 1.5 mm above the build plate. Blue and green contours indicate gas flow in the primary direction, and yellow contours show reverse flow back toward the inlet.

Table 1.

Scan parameters for Scalmalloy.

2.5. Analysis of Qualification Test Artifact

Once printed, both artifacts were scanned using a Pinnacle PXS-225/70 (Pinnacle X-Ray Solutions, Duluth, GA, USA) X-ray Computed Tomography (XCT) system and reconstructed in VGSTUDIO 2024.1 (Volume Graphics GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) to identify porosity size distribution and total amount of pores. Uncertainty values vary depending on the material and dimensions of the sample; in this case, the measurements are estimated to have an uncertainty of 5%. It should also be noted that the porosity analysis neglected anomalies with an equivalent diameter below 7 μm and above 1 mm, to avoid inclusion of non-pore features, and any potential contour porosity by filtering out near-edge porosity (porosity within 500 μm of an edge). Furthermore, numerous mechanical analyses were performed on the artifacts as a preliminary holistic evaluation on the effects of improved gas flow over the fabrication of complex geometries. Similar to the process described by Singh et al. [36], tensile bars printed as part of the QTA were manually removed from the main structure after heat treatment and submitted to tensile testing on an MTS Bionix (MTS, Eden Prairie, MN, USA), using a 25 kN load cell with a strain rate of 0.05 mm/s and 0.03 mm/s for Type 5 and Type 4 tensile specimens, respectively. The former refers to samples with a cross-sectional diameter of 2.5 mm, and the latter to a diameter of 4 mm. Strain was monitored throughout the testing process using a Zwick-Roell laserXtens 2-120 HP non-contact extensometer (ZwickRoell, Ulm, Germany).

In addition, micrographs of the artifacts were generated with the purpose of analyzing melt pool history. The artifacts were sectioned in half using a precision cutter Brilliant 220 with a C139 cutting disk (ATM Qness GmbH, Mammelzen, Germany), mounted with Aka-Resin Liquid Epoxy (Akasel A/S, Svogerslev, Denmark) and left to cure for 24 h. Afterwards, the samples were ground and polished with a single-wheel grinder Saphir 550 (ATM Qness GmbH, Mammelzen, Germany), with paper grits of 320P, 600P, and 1200P for the grinding, and polishing media of 3 µm and 0.1 µm. To improve the visibility of the melt pools, the samples were etched with Kroll’s reagent composed of 2 mL HF, 4 mL HNO3, and 96 mL DI water. Micrographs of the cross-sections of the samples were captured using a Keyence VHX7000 (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan) at a magnification of 100X. The resulting images were then analyzed visually to determine if the presence of soot and other byproducts had an effect on melt pool formation. Lastly, Vickers hardness measurements were taken at different regions across the sectioned plane using a Qness 60A (ATM Qness GmbH, Golling, Austria) micro hardness tester; a total of 132 datapoints were obtained using HV 0.1, 0.5, 1 and 5, depending on the size of the geometry being sampled.

3. Results and Discussion

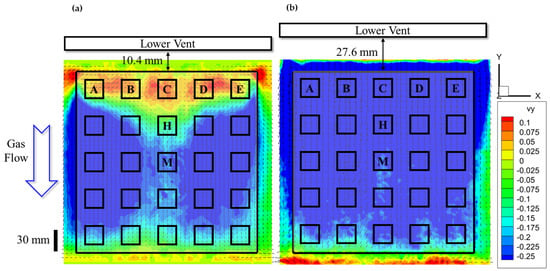

3.1. Flow Field Characteristics

With the data obtained from the MRV measurements, it was possible to reconstruct the full three-dimensional flow field in the scaled-down model of the modified EOS M290. In Figure 4, a comparison is made between the original gas flow configuration and the modified version. Both images depict gas flow distribution in the plane 0.5 mm above the build plate in the scaled-down model, or 1.5 mm in the actual machine. Color contours show the normalized Y-component of velocity (normalized by the bulk mean velocity in the supply pipe) and arrows indicate the in-plane velocity vectors. Figure 4a presents a large recirculation zone near the gas flow inlet, which has been explained previously as a classic backwards-facing flow created by the step in the Z-axis between the inlet vent and the build plate. On the other hand, Figure 4b displays a cohesive stream of gas flow across the entire length of the build platform, thus confirming that raising the platform has a significant effect on the overall flow field as it eliminates measurable recirculation seen at the problematic region.

Figure 4.

Color map of normalized velocity in the Y direction and in-plane velocity vectors illustrating the gas flow distribution across the XY plane of the build platform obtained through MRV experimentation, overlayed with the plate layout displaying plate labels at regions of interest. (a) Original chamber configuration with step in the Z-axis (referred to as OEM configuration); (b) modified chamber configuration with no step in the Z-axis (referred to as MOD configuration).

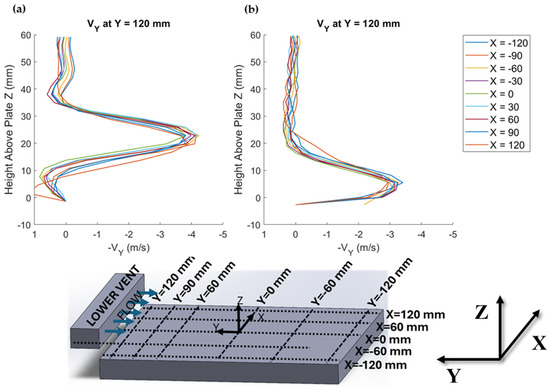

A quantitative analysis of gas flow velocity in the affected region further confirms the effect of the modified configuration, as shown in Figure 5. The MRV experimental conditions matched the Reynolds number of the argon flow in the real EOS chamber. Doing so resulted in equivalent flow patterns within the fluids of the full-scale system and the replica, allowing the experimental results to be dynamically scaled to match the full-scale flow. Scaled MRV values have been shown in Elkins et al. [27] to agree with previously published hot-wire measurements in an EOS system, namely Weaver et al. [41]. Scaled Y-component velocities (VY) are shown in Figure 5; these values have an approximate uncertainty of 4% and 10% in the regions with fastest and slowest flow, respectively, as reported by Elkins [27].

Figure 5.

Vertical profiles of scaled gas flow velocity in the Y direction (VY) near the lower inlet vent, taken across the width of the build plate in the X direction. Note negative Y is in the primary flow direction. (a) Original chamber configuration (OEM); (b) modified chamber configuration (MOD).

Vertical profiles of VY in the baseline chamber, taken across the X-axis of the build plate, highlight the consistent presence of a recirculation bubble located between 0 and 10 mm in the Z-axis, displayed in the form of positive (opposite to the primary flow in the negative Y direction) velocity values (Figure 5a). This zone of recirculation can be attributed to the step seen in the original configuration and is eliminated in the modified model, as seen in Figure 5b, which instead indicates that the gas flow is attached to the surface of the build platform. Therefore, it can be concluded that, by implementing these modifications, it is possible to shift the velocity profile in such a way that eliminates the formation of a backwards-facing flow current near the lower inlet vent.

Additionally, gas flow velocity at specific regions of interest (shown in Figure 4) was acquired and used to estimate differences between both configurations. These values can be seen in Table 2, which demonstrates an average velocity increase of ~3.5 m/s across the first row of plates, an increase of 1.86 m/s at position H and a reduction of 0.15 m/s at plate M. These values are likely not an exact match of those of the full-scale system but still provide a reasonable representation of the improvements to the flow field achieved through the implementation of chamber modifications.

Table 2.

Gas flow velocities at different regions of interest for OEM and MOD configurations.

3.2. Laser Beam Characteristics

Beam profiling tests revealed that the laser properties met the criteria of a healthy Gaussian beam before and after the implementation of the spacer ring, which was used to offset the height of the optics. Table 3 displays beam characteristics before and after the modifications to the scan head. Per the machine’s manufacturer, an adequate beam waist diameter for an EOS M290 can range between 80 and 100 µm. As seen in the contents of the table, both configurations presented a diameter in the middle of the recommended range, with an increase of only 2.8% when adding the spacer ring. Similarly, comparison of beam waist position shows little difference between configurations, with a deviation of 2.2%. These results, measured as per ISO 11146 [42], suggest that laser beam characteristics were not affected by the modifications to the chamber. To prevent potential misinterpretation of the data, the variations observed between measurements were presented and discussed with the manufacturer of the beam analyzer. It was determined that the deviations were within the expected uncertainty when characterizing laser beam properties. Therefore, the displacement of the optics should not be considered as a significant contributing factor of variation when discussing the results presented below.

Table 3.

Comparison of laser beam characteristics.

3.3. Plate Scan Results

3.3.1. OEM vs. MOD—Plates B, H & M

Melt pool depth was measured at three specific regions (B, H, and M) starting from the upstream end (B—closest to the gas flow inlet) to the downstream end (M—farthest from the gas flow inlet). In terms of their distance to the front edge of the build platform, as measured from the center of each individual plate, plate B had a separation of 23.4 mm in the Y-axis, plate H of 74.2 mm and plate M of 125 mm (as shown in Figure 2), with plate B having an additional offset of 50.8 mm to the left in the X-axis. For the OEM configuration, the inlet vent was 10.4 mm from the edge of the build plate, while the recessed vent in the modified (MOD) configuration was 27.6 mm (see Figure 4). Using the OEM configuration, Elkins et al. [27] reported an increase in melt pool depth as the plates moved further away from the inlet vent; specifically, in their study, plate B stood out as the sample with the most shallow melt pools and, as such, became the region of interest when implementing an additional vent to improve gas flow distribution. Following that example, the first analysis of the present work focused on comparing plate B with plates H and M, which previously had been found to be located in a region with good gas flow distribution.

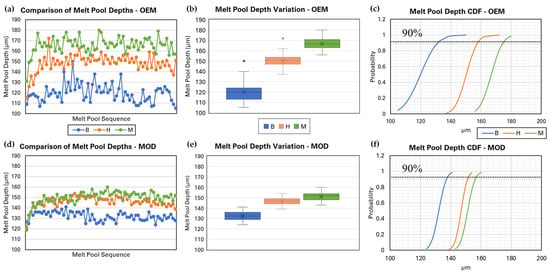

Figure 6 shows the measured melt pool depths from each of the 70 vector stack patterns. Figure 6a,d present the results from all 70 melt pools, while subsequent analyses and discussion exclude the first five samples in an effort to prevent interference caused by the transient heating state of the plate induced by the laser at the start of the plate scans. A box and whisker plot and a cumulative distribution function (CDF) for each of these profiles are also shown. The melt pool depth variations observed in the OEM configuration are presented in Figure 6a. These display significant differences between plates, with shallow melt pools near the gas flow inlet (plate B) and deeper ones downstream (plates H then M). In Figure 6b, the lower “whisker” represents the first quartile (Q1) of the full dataset, the shaded area represents Q2 and Q3, and the upper “whisker” contains the last quartile (Q4). In addition, outliers found within the dataset are depicted as dots located below or above the whiskers, the average is presented as an “X” within the box, and the median is the division within the shaded area, which separates the second and third quartiles. It may be observed that plate B shows the highest variation, with an approximate range of 12 μm between Q1 and Q3, followed by plate M (~8 μm) and, lastly, plate H (~7 μm). These results coincide with the findings of the previous investigation [27] and serve to highlight the effects of inadequate gas flow distribution in the OEM design. Figure 6c shows the CDF for these data and illustrates this point more clearly. This type of analysis organizes values within a dataset from smallest to largest and calculates its distribution by assigning a probability to each value, which continuously accumulates until reaching a probability of 1. This probability value represents the percentage of datapoints, in relation to the full dataset (i.e., using the 65 melt pools), that have a value equal to or lower than the value being analyzed. In this case, for example, the curve of plate B (Figure 6c) communicates that melt pools in that region have a minimum depth of ~105 μm, which represent less than 10% of total samples, and a maximum depth of ~150 μm, which is equal or greater than 100% of the samples within the dataset. The position of each curve shifts to the right as the plates move further away from the inlet, indicating that the depth is increasing. It should also be noted that 90% of melt pools on plate B had a depth of ~130 μm or less, while plates H and M had 90% of their datasets within ~158 μm and ~175 μm, respectively.

Figure 6.

Melt pool depth analysis for plates B, H and M. (a) Comparison of melt pool depths produced with OEM configuration; a standard deviation of 8.9, 5.8 and 6 μm was observed for scan tracks produced at plates B, H, and M, respectively; (b) melt pool depth variation for OEM configuration; (c) cumulative distribution function for OEM configuration; (d) comparison of melt pool depths produced with MOD configuration; a standard deviation of 4, 3.3 and 3.8 μm was observed for scan tracks produced at plates B, H, and M, respectively; (e) melt pool depth variation for MOD configuration; (f) cumulative distribution function for MOD configuration.

Conversely, the data produced with the MOD configuration exhibit reduced variability, shown as a tighter range of values in the curves in Figure 6d. The data demonstrate less overall melt pool variation within samples of the same plate and across different plates. A similar description may be applied to Figure 6e, which displays narrow boxes—with an average range of ~7 μm—accompanied by equally short whiskers. This representation illustrates more effectively the similarity in melt pool depths between plates H and M, and the general similarity in variation for all plates. These characteristics translate to steeper slopes for every CDF curve in Figure 6f, suggesting tighter process control capable of producing more consistent results. In this case, 90% of the samples on plate B have a melt pool depth of ~138 μm or less, with the average being closer to 132 μm. Considering the previous average of ~120 μm, this signifies an increase of 10% in melt pool depth within the affected region. As for plates H and M, 90% of total samples can be found within ~151 μm and ~156 μm, respectively, with their corresponding averages at ~147 μm and ~151 μm, in that same order. This signifies an overall decrease in melt pool depth for those specific sections; however, it must be noted that the spatial location-induced variations—such as the ones observed in the OEM configuration—appear to be significantly attenuated, as the samples across these two plates present similar melt pool depth and distribution. In addition, it is worth mentioning that outliers on the upper end of the dataset, seen as long “tails” at the top of the CDF curves in Figure 6c, are no longer present in any of the plates, thus reinforcing the argument of increased process control.

The modifications to the chamber geometry appear to create a pronounced effect on the removal of contaminants and stabilization of the melt pool; even then, small variations and lack of uniformity across plates suggest that improvements to the flow field cannot fully counteract the inherent variations in local conditions. Specifically, the difference observed in melt pool depth between plate B and plates H and M could be partially explained by considering the increase in the incidence angle of the laser beam. Plate M is located closer to the center of the build plate, followed by plate H, and then plate B. Recalling Figure 6a, it may be noted that plate M displays deeper melt pools, followed by plate H and, lastly, plate B. The results obtained with the MOD configuration suggest that the removal of the backward-facing step flow led, as a direct result, to the creation of similar melt pool depths for plates H and M. Plate B, on the other hand, is not only one row above H, but is also located one column to the left of the other two plates, thus introducing additional changes to the incidence angle. This, in turn, could be the root cause of the measured melt pool depth differences between plate B and plates H and M observed in Figure 6d.

If flow variability between locations is reduced, differences in melt pools could, in part, be due to laser beam effects, such as incidence angle and power density (relating to projected area differences on the build plane). In an effort to quantify this difference, an incidence angle of zero could be assigned to plate M (θM = 0°) by assuming that the sample is aligned with the laser. Using this as a foundation, an estimated value of θH = 6° can be calculated as the incidence angle at plate H, considering the vertical distance between the plate and the optical lens as ~482 mm, and the horizontal distance between plates M and H, measured from their respective centers, as 50.8 mm. Using this same approach for plate B, it could be estimated that scans performed at this location would exhibit an approximate incidence angle of θB = 13.3°, considering a horizontal distance of ~113.6 mm between plates M and B. This calculation demonstrates that the angle of incidence at plate B is the highest out of the three samples. However, incidence angle alone cannot explain the melt pool depth discrepancies, since even at 13.3°, geometric differences could explain only about a 3% difference in melt pool depths at these locations (i.e., cos(13.3°) = 0.97).

In addition to the laser angle of incidence, the projected laser spot onto the build plate becomes elliptical as the laser scans the surface at an angle. By considering the laser beam to be a cylinder of a given diameter that is rotated by 13.3°, it is possible to calculate the change in the projected area of the laser beam on the build plate through simple trigonometric operations. Calculation of the laser spot using the estimated incidence angle yields an area 1.027 times greater than the area at θM = 0°. Seeing as the power of the laser is now distributed across a larger area, it can be expected for laser power density to be lower at this region. These results demonstrate good agreement with those of Fathi-Hafshejani et al. [43], who observed an increase in laser spot area of 1.03 times at θ = 14°. As discussed in the study, an increase in laser incidence can lead to elongation of the laser spot, which exhibited a strong correlation to shallower melt pool depth. Based on the values reported in said publication, a reduction in melt pool depth of 3.5–9.5% could be observed at θ = 14°, depending on the scanning direction in relation to the elongation of the laser spot. In the MOD configuration, assuming spatial flow-induced variations in melt pool depth have been decreased, the average reduction in melt pool depth at plate B (θB = 13.3°)—in relation to plate M (θM = 0°)—is ~12.5%. While not an exact match, it is a significant improvement over the 28% difference observed in the OEM configuration. This, in turn, could be considered as an indicator that the gas flow configuration can be further refined to enhance melt pool depth consistency irrespective of the position on the build plate. These results are encouraging, as they support the hypothesis that variations in melt pools depths due to flow can be minimized; thus, leading to a conclusion that modifications to laser parameters (once gas flow variability has been minimized) can be used to provide equivalent melt pool depths throughout the build chamber. Future work should focus on assessing potential enhancements to the flow field to minimize its influence over melt pool depth variation, as well as implementing localized parameter modifications to address these remaining inconsistencies. Parameters such as laser power, scan speed, and hatch distance could be spatially adjusted based on predicted melt pool depth behaviors. Such localized parameter modifications would aim to equalize the energy input and cooling rates across the build plate, thereby further homogenizing melt pool depths and refining the microstructural uniformity and mechanical properties of the fabricated parts.

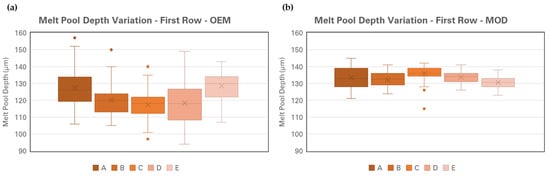

3.3.2. OEM vs. MOD—First Row

As previously mentioned, the present work aims to improve the distribution of gas flow across the build plate, rather than in a single localized region. To this end, the entire first row of plates (A–E) from both configurations was analyzed and compared. The data are presented in Figure 7 as box and whisker plots to facilitate visualization of melt pool depth distribution. As seen in Figure 7a, every plate presents a range of more than 30 μm between the smallest and largest values within their respective datasets, not including outliers. The average melt pool depth does not exceed 130 µm in any of the plates and appears to follow the same pattern as the one observed by Elkins et al. [27], with the only difference being that, in this case, plate C is positioned slightly lower than plate B, with averages of ~117 µm and ~119 µm, respectively. However, plate C also displays the least amount of variation in relation to other plates from the first row, arguably as a result of a decreased incidence angle of the laser beam due to the position of the plate at the center of the row.

Figure 7.

Melt pool depth variation for plates located on the first row; (a) OEM configuration; (b) MOD configuration.

Alternatively, melt pools produced with the MOD configuration display increased depth in all plates, along with reduced variability within each dataset (Figure 7b). A more detailed inspection reveals plate C as the sample that benefited the most from the improved gas flow distribution, with an increase of ~15% to the average melt pool depth, followed by the plates adjacent to it—B and D—and, lastly, the plates at each end of the row—A and E. Additionally, it may be worth noting that sample variation follows a similar pattern, with the plate located in the middle of the row displaying the least variation, which then increases as the position of the plates moves further away from the center. These observations support the claim that the strongest area of recirculation can be found near plate C, serving as a compelling example of the effect that poor gas flow can have on part quality and process control. Plates B, C, and D are inherently located in more advantageous positions than A and E, in terms of laser beam incidence angle; yet, they exhibit lower average melt pool depth and comparable variation when using the OEM configuration. This phenomenon potentially suggests that the recirculating flow generated near the inlet vent when using the original chamber setup attenuates the laser power directed to the plates, either through particle redeposition or laser path obstruction with recirculated contaminants or byproducts. Following this logic, the results obtained with the MOD configuration can be interpreted as the expected outcome when using improved gas flow, with plate C, located at the center, presenting the deepest melt pool average, followed closely in decreasing order by adjacent plates.

An observation made in a previous study [27] proposes that, in the original EOS M290 chamber setup, the presence of longitudinal vortices at the sides of the vent causes the separation region to close at the edges first, thus suggesting that plates A and E would possibly not be affected as drastically as the plates in between. These results further support that analysis, as plates A and E are the least affected when changing between OEM and MOD configurations, while still showing an overall improvement in melt pool depth and, in the case of plate E, a significant decrease in variation. Plate A, on the other hand, retains a larger sample distribution between Q1 and Q3 relative to the other locations, as seen in Figure 7b. This behavior could potentially be attributed to the presence of the recoater at the leftmost side of the chamber—when looking from the front of the machine—which acts as a large obstruction in the flow field and disrupts local currents. Assuming this to be true, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of additional regions across the build plate being influenced—to a lesser extent—by these disturbances. While feasible, additional testing centered around the impact of the recoater on adjacent regions of the build plate would be required before any conclusive statements can be made regarding the complicated flow characteristics and interactions (such as with melt pools) within the build chamber. However, it can be concluded that improving gas flow within the chamber provides measurable improvements to melt pool depths (both in location-specific variability and differences between locations). Once spatial flow characteristics can be optimized, further improvements to ensuring common melt pool depths can be pursued, to include, for example, spatial laser power modifications to account for laser incidence angle and spatial beam profile.

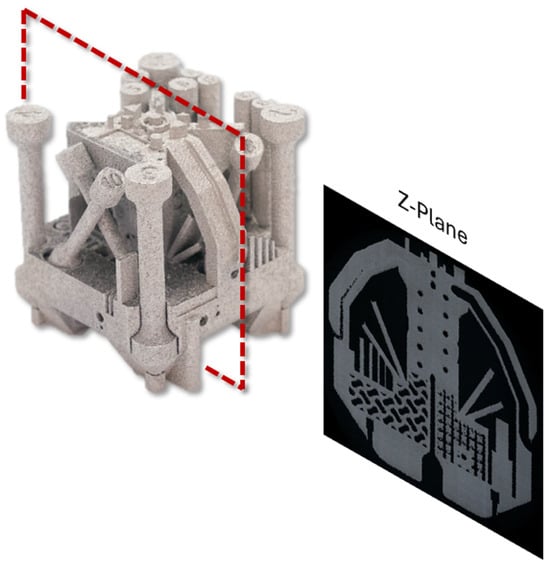

3.4. Artifact Results

As stated before, qualification test artifacts were built to provide a holistic insight into how the different flow conditions affect part quality and potential defect formation in complex geometries built with metal powder; Figure 8 depicts one of the artifacts manufactured as part of the experiment, as well as the approximate location of the Z-plane analyzed for the study. Only one artifact was built for each flow configuration (see Figure 3 for the location of the artifact on the build plate), and therefore, the artifact results reported in this study are preliminary and are to be used for more holistic and qualitative comparisons of part quality between flow configurations. However, they do provide clues as to the influences flow can have on part quality and performance.

Figure 8.

Qualification test artifact (MOD) accompanied by Z-plane used as part of the analysis (the approximate location of the plane is denoted by the dashed square).

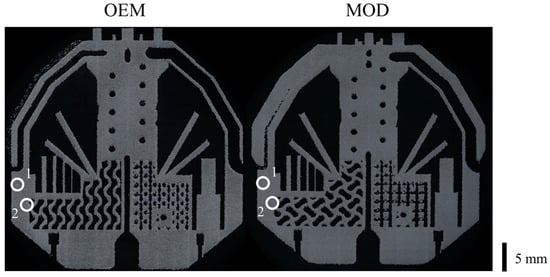

3.4.1. Microstructure Analysis

Analysis of the micrographs shown in Figure 9 revealed similar microstructures for both Scalmalloy artifacts, with only a few differences. The most notable is the presence of two large spatter ejecta outside of the lattice structure on the artifact fabricated with the OEM configuration (Figure 10). These anomalies are identified as spatter as per Kumar’s [44] definition, which describes them as large impurities (unstable molten particles) that remain on the surface and prevent proper bonding with surrounding layers, thus leading to potential internal defects. On the other hand, the MOD artifact did not display any notable characteristics with regard to spatter or defect/anomaly formation, which supports the initial hypothesis that an improved shielding gas flow configuration can promote the removal of soot and spatter particles during the building process. Evaluating a single Z-plane in each artifact provides holistic and illustrative insight into the complex microstructural architecture resulting from features such as bulk regions, overhangs, thin walls, lattice structures, and more. It is noteworthy that suspected spatter was only identified in the micrograph of the OEM artifact and not in the MOD artifact. However, many more artifacts and analyses, including additional evaluation planes for each artifact and across multiple artifacts, would be required to provide statistical evidence supporting the potential quality improvements identified here as a result of improved flow. This is the subject of ongoing work and updates will be provided in subsequent publications.

Figure 9.

Micrographs of OEM and MOD artifacts. Regions of interest are marked and labeled to denote the same location for each artifact.

Figure 10.

Zoomed-in view of regions 1 and 2. Large spatter ejecta can be seen in the OEM artifact, while no equivalent anomalies were identified on the MOD artifact.

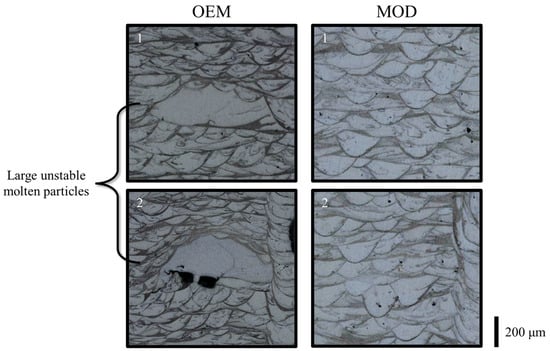

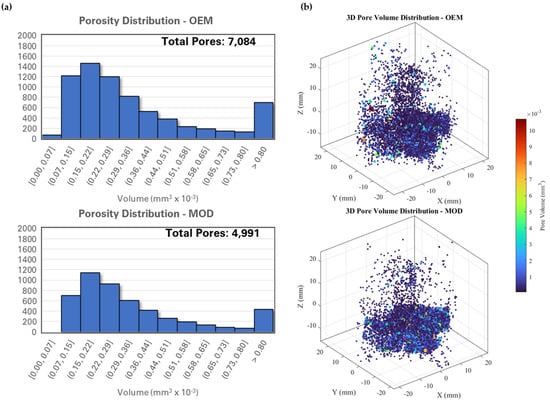

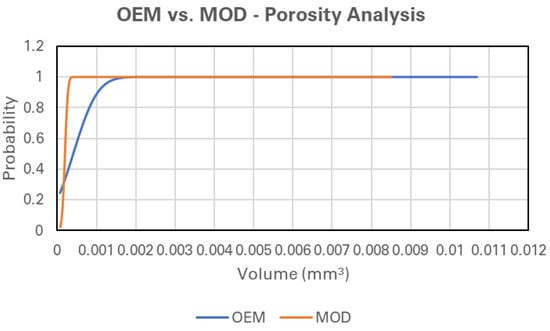

3.4.2. Porosity Analysis

As illustrated in Figure 11, the artifact produced with the improved gas flow configuration (MOD) exhibited a reduction in the number of pores compared to the one manufactured with the OEM setup. Close observation of the histograms (Figure 11a) reveals that the number of porosities found in the MOD artifact was consistently lower in every bin than that of its counterpart, thus leading to an overall reduction of ~30% in total pore count.

Figure 11.

(a) Porosity size distribution histograms per artifact, with each bin representing a volume range in mm3 × 10−3, for improved visualization; (b) isometric view of 3D porosity map of both artifacts color coded in terms of pore volume (mm3 × 10−3).

A porosity point-cloud was generated with VGSTUDIO and post-processed on MATLAB R2023b with the purpose of visualizing porosity distribution between flow configurations, as seen in Figure 11b. Although difficult to identify at a glance, it can be discerned that the OEM artifact has a denser point-cloud in relation to its counterpart, particularly near the center and upper section of the sample. It is hypothesized that the reduction in porosity is due to the modified flow configuration contributing to a more consistent removal of byproducts and contaminants, thereby reducing the interference with the laser beam path and enhancing the energy delivery to the material.

Further analysis through cumulative distribution functions (Figure 12) reinforces this interpretation, as it demonstrates a noticeable difference between both datasets, with the modified configuration displaying significant improvement over the original. The curve for the OEM arrangement rises gradually, indicating that the samples within the dataset have a larger spread, which directly translates to greater variation in porosity size. The curve representing the MOD dataset, on the other hand, rises sharply and approaches a probability of 1 at a volume of 0.493 × 10−3 mm3; in the case of the OEM curve, a similar volume is achieved with a probability of 0.57. This indicates that the vast majority (99%) of all samples in the MOD dataset fall below 0.493 × 10−3 mm3, whereas over 40% of OEM samples exceed this threshold, highlighting a higher pore volume when utilizing the OEM configuration. These results, while preliminary, support the initial argument that improved gas flow characteristics, achieved through the modification of the chamber, contribute to a more stable and controlled melt pool, as described in Section 3.3.

Figure 12.

CDF of porosity volume within qualification test artifacts manufactured with OEM and MOD configurations.

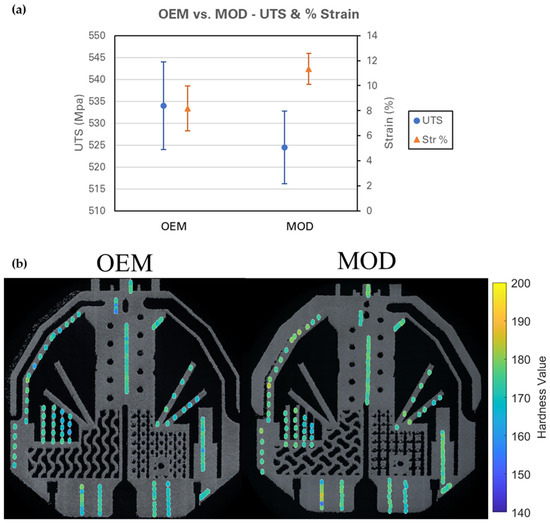

3.4.3. Mechanical Testing Results

Results of the mechanical analyses performed on the artifacts from the two flow configurations can be seen below, in Figure 13. These include UTS, percent strain at break and Vickers hardness at different positions of the Z-plane—seen in Figure 8 and Figure 9—for the OEM and MOD configurations. The tensile analysis was focused on the Type 5 coupons since Type 4 bars presented negligible sensitivity to changes in position and gas flow configuration. It is apparent that a higher UTS was achieved by the OEM samples; however, it should be noted that UTS results, especially from subsize specimens, should be evaluated with caution as previous researchers have found them to be difficult to measure and overall insensitive to porosity levels typically found in LPBF, as reported by Kan et al. [45], Kantzos et al. [46], Voisin et al. [47] and Gamboa et al. [48]. Conversely, percent strain at break displayed by the coupons increased when manufactured with the MOD configuration; Figure 13a illustrates these mechanical properties for both artifacts. As for local geometry hardness variability, 132 hardness indents were performed across different sections of the Z-plane. Both parts exhibited comparable properties, with the MOD artifact demonstrating a minor overall increase in HV (~1.5%), in relation to the OEM. Figure 13b depicts local hardness variations for both artifacts. The findings are encouraging but are presented solely for qualitative comparison as part of the holistic evaluation and, as such, require a more rigorous framework in order to develop a deeper understanding on the influence of improved gas flow over mechanical properties. Overall, this initial indication, requiring further study to statistically verify, contributes to the main argument of the present work, which states that shielding gas flow distribution could be improved by removing the backwards-facing step flow which, in turn, would result in enhanced properties when building parts in the affected region. In combination, the results—from the melt pools to the three-dimensional holistic artifacts—are compelling in support of improved unidirectional gas flow leading to enhanced manufacturing outcomes.

Figure 13.

Comparison of mechanical properties between OEM and MOD artifacts. (a) UTS and % strain at break. (b) Vickers hardness at different positions of the Z-plane.

3.5. Limitations

The authors believe the melt pool findings presented in this study are profound and could potentially indicate a feasible approach to reducing spatial melt pool variations during the build process that result from variations in flow and laser beam delivery—due to laser incidence and beam profile at the surface. Additional observations made through the analysis of the QTA are encouraging and support the statement that a more uniform and coherent gas flow across the build plate promotes part quality and reduces the formation of potential defects. For clarity, the main limitation affecting the robustness of these data (in the context of QTA observations) is sampling size. For this reason, interpretation of these results is used solely for qualitative analysis and comparisons that aim to demonstrate potential trends correlating improved gas flow with enhanced part quality. As such, future work will pursue analysis of the microstructure, porosity and mechanical properties of parts built within different flow configurations, using a sufficiently large sample size to ensure statistical significance. It should be stated, however, that the melt pool results support the investment in more detailed part studies, although the authors suggest the melt pool approach be used first to further optimize and understand the impacts of flow and laser beam angle of incidence and profile on melt pool depths.

4. Conclusions

The present study focused on improving shielding gas flow distribution within a commercial PBF-LB/M system, specifically an EOS M290, with the objective of enhancing the overall quality of manufactured parts. Through a series of targeted modifications, including raising the build platform, optics, and recoater, as well as adjusting the inlet vent, the authors aimed to eliminate the backward-facing step flow forming near the lower vent and stabilize the flow layer. Beam profiling tests confirmed that the laser characteristics were preserved, ensuring that the integrity of the laser optics sub-system remained unaffected by the hardware changes. Plate scan results aligned with observations made in previous research and demonstrated measurable enhancements in melt pool depth consistency across different regions of the build plate. The improved gas flow configuration led to more uniform melt pool depths, indicating stabilization of the melt pool. Building qualification test artifacts further validated these findings, where porosity analysis via XCT indicated a reduction in the number and size of porosities detected in the qualification test artifact fabricated with the improved gas flow. This reduction was attributed to the improved removal of byproducts and contaminants, which otherwise likely interfere with the laser beam path and hinder energy delivery to the material. The correlation between enhanced gas flow characteristics and reduced porosity aligns with prior findings, reinforcing the importance of precise gas flow control in PBF-LB/M processes.

These findings demonstrate that improvements to shielding gas flow distribution within a PBF-LB/M system are possible and beneficial for enhancing part quality and consistency. The modifications implemented in this study effectively reduced flow-related issues—as validated by MRV experimentation—leading to more uniform melt pool depths, and early signs of reduced porosity, which should be explored further. In addition, it is worth noting that these modifications are only made possible by having an adequate understanding of gas flow characteristics within the system, thus highlighting the importance of qualification and characterization of this sub-system within laser powder bed fusion machines. Implementation of the modifications did not produce adverse effects on the normal operation of the machine, with parameters such as system pressure and flow rate staying the same. Increasing the height of the build platform directly translated to an increase of 14.5 mm in the total build height supported by the system. Because of the height-adjusting design of the new recoater, powder spreading within the new configuration remained largely unchanged and did not present any abnormal behaviors or difficulties. Future work will focus on further refining the gas flow configuration in an attempt to minimize its effects over melt pool depth variation, developing a robust experiment design for the analysis of gas flow effects on complex geometries—such as the ones observed on the QTAs—and exploring localized parameter modifications to address the remaining inconsistencies and achieve even greater uniformity and part quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jmmp10010003/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.W. and C.J.E.; methodology, R.B.W. and C.J.E.; software, C.J.E.; validation, C.J.E. and H.H.E.M.; formal analysis, H.H.E.M.; investigation, J.M., A.E. and H.H.E.M.; resources, R.B.W.; data curation, C.J.E.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M., A.E. and H.H.E.M.; writing—review and editing, R.B.W., C.J.E., J.M. and H.H.E.M.; visualization, C.J.E., J.M. and H.H.E.M.; supervision, R.B.W., C.J.E. and J.M.; project administration, R.B.W. and J.M.; funding acquisition, R.B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based on research sponsored by Air Force Research Laboratory under Agreement Number FA8650-20-2-5700. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation thereon. Additional support was provided by strategic investments via discretionary UTEP Keck Center funds and the Mr. and Mrs. MacIntosh Murchison Chair I in Engineering Endowment at UTEP.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article or Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The research described here was performed at The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP) within the W.M. Keck Center for 3D Innovation (Keck Center). The authors are grateful to UTEP students Luis Tarango and Julissa Arteaga for metallography, Brenda Valadez Mesta, Paola Almaraz and Rebecca Herrera for laser beam measurements testing, analysis and first draft, and Priscila Narvaez for XCT analysis. The authors are also grateful to Daniel Borup for making the necessary arrangements to allow the research team to utilize the MRI system at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, and for his assistance in setting up the MRV experiment and data processing. Lastly, the authors would like to thank Hunter Taylor for the initial conceptualization of the modifications performed to the EOS M290.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PBF-LB/M | Metal Laser Powder Bed Fusion |

| AMMT | Additive Manufacturing Metrology Testbed |

| MRV | Magnetic Resonance Velocimetry |

| XCT | X-Ray Computed Tomography |

References

- Qin, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Wen, P.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, Y.; Voshage, M.; Schleifenbaum, J.H. Influence of Laser Energy Input and Shielding Gas Flow on Evaporation Fume during Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Zn Metal. Materials 2021, 14, 2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, B.; Enk, S.; Schleifenbaum, J.H. Analysis of the Shielding Gas Dependent L-PBF Process Stability by Means of Schlieren and Shadowgraph Techniques; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitharas, I.; Burton, A.; Ross, A.J.; Moore, A.J. Visualisation and numerical analysis of laser powder bed fusion under cross-flow. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladewig, A.; Schlick, G.; Fisser, M.; Schulze, V.; Glatzel, U. Influence of the shielding gas flow on the removal of process by-products in the selective laser melting process. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Rometsch, P.; Wu, X.; Huang, A. Influence of Gas Flow Speed on Laser Plume Attenuation and Powder Bed Particle Pickup in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. JOM 2020, 72, 1039–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrar, B.; Mullen, L.; Jones, E.; Stamp, R.; Sutcliffe, C.J. Gas flow effects on selective laser melting (SLM) manufacturing performance. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2012, 212, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D. Influence of shielding gas flow consistency on parts quality consistency during large-scale laser powder bed fusion. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.; Schlenoff, A.; Deisenroth, D.; Moylan, S. Assessing the influence of non-uniform gas speed on the melt pool depth in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototy. J. 2023, 29, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehr, S.; Klecker, T.; Pielmeier, S.; Ammann, T.; Zaeh, M.F. Experimental and analytical investigations of the removal of spatters by various process gases during the powder bed fusion of metals using a laser beam. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 905–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhong, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, L. Enhancing the spatter-removal rate in laser powder-bed fusion using a gas-intake system with dual inlets. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2025, 26, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijonen, J.; Revuelta, A.; Riipinen, T.; Ruusuvuori, K.; Puukko, P. On the effect of shielding gas flow on porosity and melt pool geometry in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 101030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitharas, I.; Parab, N.; Zhao, C.; Sun, T.; Rollett, A.D.; Moore, A.J. The interplay between vapour, liquid, and solid phases in laser powder bed fusion. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baehr, S.; Melzig, L.; Bauer, D.; Ammann, T.; Zaeh, M.F. Investigations of process by-products by means of Schlieren imaging during the powder bed fusion of metals using a laser beam. J. Laser Appl. 2022, 34, 042045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deisenroth, D.C.; Neira, J.; Weaver, J.; Yeung, H. Effects of Shield Gas Flow on Meltpool Variability and Signature in Scanned Laser Melting. In Volume 1: Additive Manufacturing; Advanced Materials Manufacturing; Biomanufacturing; Life Cycle Engineering; Manufacturing Equipment and Automation, Virtual, 3 September 2020; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. V001T01A017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Yang, W.; Wu, S.; He, Y.; Xiao, R. Effect of plume on weld penetration during high-power fiber laser welding. J. Laser Appl. 2016, 28, 022003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Yao, J.; Du, B.; Li, K.; Li, T.; Zhao, L.; Guo, Y. Effect of Shielding Gas Volume Flow on the Consistency of Microstructure and Tensile Properties of 316L Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Metals 2021, 11, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Lough, C.; Wilson, D.; Newkirk, J.; Liou, F. Atmosphere Effects in Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 5549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PCobbinah, V.; Nzeukou, R.A.; Onawale, O.T.; Matizamhuka, W.R. Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Potential Superalloys: A Review. Metals 2020, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Yin, J.; Li, Y.; Nie, Z.; Li, X.; You, D.; Guan, K.; Duan, W.; Cao, L.; et al. A Review of Spatter in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: In Situ Detection, Generation, Effects, and Countermeasures. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, N.; Uddin, S.Z.; Weaver, J.; Jones, J.; Singh, S.; Beuth, J. Computational analysis and experiments of spatter transport in a laser powder bed fusion machine. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 84, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, B.; Tuffile, C. Simulation study of the spatter removal process and optimization design of gas flow system in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 32, 101049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzon, C.; Hryha, E.; Forêt, P.; Nyborg, L. Effect of argon and nitrogen atmospheres on the properties of stainless steel 316 L parts produced by laser-powder bed fusion. Mater. Des. 2019, 179, 107873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauzon, C.; Forêt, P.; Hryha, E.; Arunprasad, T.; Nyborg, L. Argon-helium mixtures as Laser-Powder Bed Fusion atmospheres: Towards increased build rate of Ti-6Al-4V. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 279, 116555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidare, P.; Bitharas, I.; Ward, R.M.; Attallah, M.M.; Moore, A.J. Fluid and particle dynamics in laser powder bed fusion. Acta Mater. 2018, 142, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunenthiram, V.; Peyre, P.; Schneider, M.; Dal, M.; Coste, F.; Koutiri, I.; Fabbro, R. Experimental analysis of spatter generation and melt-pool behavior during the powder bed laser beam melting process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 251, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, T.P.; Warner, D.H.; Soltani-Tehrani, A.; Shamsaei, N.; Phan, N. Spatial inhomogeneity of build defects across the build plate in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, C.J.; Mireles, J.; Estrada, H.H.; Morgan, D.W.; Taylor, H.C.; Wicker, R.B. Resolving the three-dimensional flow field within commercial metal additive manufacturing machines: Application of experimental Magnetic Resonance Velocimetry. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijonen, J. Sources of Variability in Metal Additive Manufacturing: Effects of Machine Architecture-Defined Process Parameters in PBF-LB AM; University of Turku: Turku, Finland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyta, A.; Nouwens, C.; Jones, A.M.; Haworth, T.A.; Montelione, A.; Ramulu, M.; Arola, D. Characterizing gas flow in the build chamber of laser powder bed fusion systems utilizing particle image velocimetry: A path to improvements. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 106, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjer, M.B.; Pan, Z.; Nadimpalli, V.K.; Pedersen, D.B. Experimental Analysis and Spatial Component Impact of the Inert Cross Flow in Open-Architecture Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Li, X. Numerical and experimental observations of the flow field inside a selective laser melting (SLM) chamber. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 151, 119330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.V.; Narra, S.P.; Cunningham, R.W.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.; Suter, R.M.; Beuth, J.L.; Rollett, A.D. Defect structure process maps for laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Rankouhi, B.; Thoma, D.J. Predictive process mapping for laser powder bed fusion: A review of existing analytical solutions. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022, 26, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.C.; Garibay, E.A.; Wicker, R.B. Toward a common laser powder bed fusion qualification test artifact. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 39, 101803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.C.; Wicker, R.B. Impacts of microsecond control in laser powder bed fusion processing. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Oliveira, J.P.; Taylor, H.; Mireles, J.; Wicker, R. A holistic approach for evaluation of Gaussian versus ring beam processing on structure and properties in laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 325, 118293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antikainen, A.; Reijonen, J.; Lagerbom, J.; Lindroos, M.; Pinomaa, T.; Lindroos, T. Single-Track Laser Scanning as a Method for Evaluating Printability: The Effect of Substrate Heat Treatment on Melt Pool Geometry and Cracking in Medium Carbon Tool Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 8418–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, E.; Scheel, P.; Müller, O.; Molinaro, R.; Mishra, S. Single-track thermal analysis of laser powder bed fusion process: Parametric solution through physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2023, 410, 116019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkins, C.J.; Alley, M.T. Magnetic resonance velocimetry: Applications of magnetic resonance imaging in the measurement of fluid motion. ExFluids 2007, 43, 823–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.; Rivas, J.; Taylor, H.; Orquiz, C.; Wicker, R. Measurement systems analysis for beam compensation, scaling factors and geometric dimensioning for a metallic additively manufactured test artifact. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 10, 2817–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, J.S.; Schlenoff, A.; Deisenroth, D.C.; Moylan, S.P. Inert Gas Flow Speed Measurements in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing; NIST AMS 100-43; National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.): Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ISO 11146-1:2021; Lasers and Laser-Related Equipment—Test Methods for Laser Beam Widths, Divergence Angles and Beam Propagation Ratios. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77769.html (accessed on 19 December 2025).

- Fathi-Hafshejani, P.; Soltani-Tehrani, A.; Shamsaei, N.; Mahjouri-Samani, M. Laser incidence angle influence on energy density variations, surface roughness, and porosity of additively manufactured parts. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 50, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saride, R.K.; Vajjala, S.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, R.; Pappula, L.; Ginuga, J.R. Processing and Characterization of Maraging Steel Using LPBF Additive Manufacturing Technology. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Appl. 2023, 11, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, W.H.; Chiu, L.N.; Lim, C.V.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, D. A HuangA critical review on the effects of process-induced porosity on the mechanical properties of alloys fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 9818–9865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantzos, C.; Pauza, J.; Cunningham, R.; Narra, S.P.; Beuth, J.; Rollett, A. An Investigation of Process Parameter Modifications on Additively Manufactured Inconel 718 Parts. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2019, 28, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voisin, T.; Calta, N.P.; Khairallah, S.A.; Forien, J.-B.; Balogh, L.; Cunningham, R.W.; Rollett, A.D.; Wang, Y.M. Defects-dictated tensile properties of selective laser melted Ti-6Al-4V. Mater. Des. 2018, 158, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]