Abstract

In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, have gained increasing interest in both academia and industries. The evolution of UAV technologies, such as artificial intelligence, component miniaturization, and computer vision, has decreased their cost and increased availability for diverse applications and services. Remarkably, the integration of computer vision with UAVs provides cutting-edge technology for visual navigation, localization, and obstacle avoidance, making them capable of autonomous operations. However, their limited capacity for autonomous navigation makes them unsuitable for global positioning system (GPS)-blind environments. Recently, vision-based approaches that use cheaper and more flexible visual sensors have shown considerable advantages in UAV navigation owing to the rapid development of computer vision. Visual localization and mapping, obstacle avoidance, and path planning are essential components of visual navigation. The goal of this study was to provide a comprehensive review of vision-based UAV navigation techniques. Existing techniques have been categorized and extensively reviewed with regard to their capabilities and characteristics. Then, they are qualitatively compared in terms of various aspects. We have also discussed open issues and research challenges in the design and implementation of vision-based navigation techniques for UAVs.

1. Introduction

Owing to the rapid deployment of network technologies, such as radio communication interfaces, sensors, device miniaturization, global positioning systems (GPSs), and computer vision techniques, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have become a potential application in the domain of military and civil society [1]. UAVs have been utilized in many civil applications, such as aerial surveillance, parcel delivery, precision agriculture, intelligent transportation, search and rescue operations, post-disaster operations, wildfire management, remote sensing, and traffic monitoring [2]. Recently, the UAV application domain has increased significantly owing to its cost effectiveness, fast mobility, and easy deployment [3].

UAVs are classified based on their characteristics [4], such as size, payload, coverage range, battery lifetime, altitude, and flying principle, as listed in Table 1. Compared to high-altitude UAVs, low-altitude UAVs have smaller battery capacity and fewer computing resources due to their size constraints. Several high-altitude UAVs have energy management capabilities, including wireless charging stations and small solar panels mounted on the aircraft. In general, UAVs are categorized based on their physical structures, such as fixed and rotary wings. Fixed-wing UAVs are widely used in military applications, such as aerial attacks and air cover. They have high-speed motion, high payload capacity, and long-lasting battery backups; however, most fixed-wing UAVs do not have vertical takeoff and landing (VTOL) facilities [5]. Recently, rotary-wing UAVs have been widely used in various civilian applications owing to their physical characteristics, such as supporting stationary positions during flight and VTOL facilities. Without human assistance, UAVs and aircraft exhibit high mobility and flexibility for civilian emergency applications [6]. However, UAVs cannot handle top-level communication and perception in a complex environment using traditional sensors. As a result, they still have to overcome challenges, such as object detection and recognition, to avoid obstacles toward achieving desirable communication [7]. Therefore, researchers have focused on the development of high-performance autonomous navigation systems.

Table 1.

Classification of UAVs.

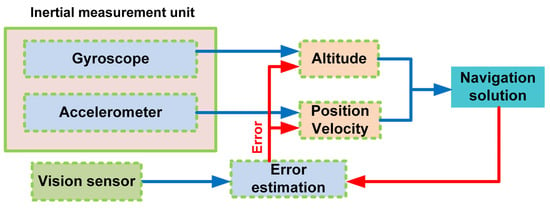

In recent years, several approaches aided by vision-based systems have been developed for UAV navigation. The UAV flies successfully when it avoids obstacles and minimizes path length. Navigation involves three main processes: localization, mapping, and path planning [8]. The localization is initially determined. A map is then visually constructed to refine the search process and avoid obstacles, in addition to allocating suitable landing sites. Eventually, the planning process aims at determining the shortest path using a proper optimization algorithm. There are three main categories of navigation methods: inertial, satellite, and vision-based navigation. Vision-based navigation using visual sensors provides online information in a dynamic environment because of their high applicability of perception owing to their remarkable anti-inference ability [9]. Exteroceptive and proprioceptive sensors are used for navigation. The dataset is then preprocessed internally for localization and mapping, obstacle avoidance, and path planning, and finally, outputs to drive the UAVs to the target location are provided. Several traditional sensors, such as GPS, axis acceleration, gyroscope, and internal navigation system (INS), are used for navigation [10]. These sensors are not as accurate as their performance accuracy. For example, reliability is a significant drawback of GPS, and its location accuracy is positively correlated with the number of available satellites [11]. However, INSs suffer a loss of accuracy owing to the propagation of the bias error caused by the integral drift problem.

Meanwhile, slight acceleration and angular velocity errors cause linear and quadratic velocity and position errors, respectively. Moreover, the use of novel methods to increase the accuracy and robustness of UAV position estimation is challenging. Many attempts have been made to enhance the environmental perception abilities of UAVs, including multiple-sensor data fusion [12] and many similar approaches. Another critical issue is the selection of the correct visual sensor. Generally, visual sensors can acquire rich information about the surroundings, such as color, texture, and other visual information, compared to graphics processing units (GPU), laser lightning, ultrasonic sensors, and other traditional sensors. Generally, navigation-based approaches use visual sensors, including monocular, stereo, red-green-blue-depth (RGB-D), and fisheye cameras. Monocular cameras are the first option for more compact applications because of their low price and flexibility [13]. However, they cannot obtain a depth map [14]. Stereo cameras are an extended version of monocular cameras that can estimate depth maps based on the parallax principle without the aid of infrared sensors. RGD-B can ensure both depth-map estimation and visible images with the guidance of infrared sensors. However, RGB-D cameras are most suitable for indoor environments because they require a limited range of areas [15]. Fisheye cameras can provide a wide viewing angle for long-range areas, which is attractive for obstacle avoidance in complex environments [16].

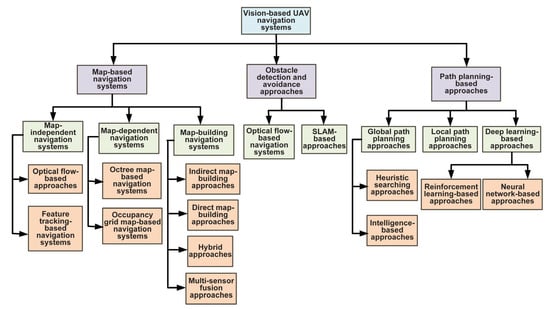

UAVs must be capable of handling several challenges, such as routing to remote locations, handling speed, and controlling the multi-angular direction from the starting point to the ending point while avoiding obstacles along the way. Moreover, they must track the invariant features of the moving elements, involving lines and corners [17]. Generally, vision-based UAVs can be classified into two types: mapping-based methods for visual localization, object detection, and avoidance [18]. Several vision-based methods use maps for visual localization. From this perspective, we divided them into three categories: map-independent, map-dependent, and map-building systems. Following that are two types of object detection methods: optical flow-based [19] and simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM)-based [20] methods. Vision-based approaches use two types of path planning for avoidance: global and local.

GPS and vision are both commonly used to navigate UAVs, but both of them have their own advantages and disadvantages. GPS-based navigation systems have the advantages of global coverage, accuracy, and low cost. Due to its ability to receive GPS signals anywhere on earth, GPS is suitable for outdoor navigation. GPS receivers are widely available and relatively inexpensive, and they can provide accuracy of up to sub-meters in the open sky. However, GPS has the disadvantages of being vulnerable to interference and relying on satellite signals. Moreover, a clear view of the sky is required for GPS to function, which may not be possible in certain environments (for example, indoors, in urban areas, and in areas devoid of GPS signals). On the other hand, vision-based navigation systems have several advantages, including their robustness to interference, high resolution, and low cost. When GPS signals are blocked, a vision-based system can estimate the UAV’s position by using visual information from its surroundings. High-resolution images captured by cameras are useful for detailed localization and mapping of the environment. There is a wide range of cameras available at affordable prices. However, vision-based systems typically have a limited range, and the UAV must remain close to the target in order to achieve an accurate location. Moreover, a vision-based system can suffer from lighting conditions such as glare and shadows, which make it difficult to see some features in such an environment. In certain environments (such as featureless terrain, snow, and deserts), vision-based methods cannot be used because there are no distinctive visual features in the environment. Generally, GPS devices are used for outdoor navigation, whereas vision-based sensors are used indoors or in GPS-denied situations, where GPS signals are blocked or unavailable. Furthermore, UAV navigation can be improved through the combination of vision-based methods and GPS.

1.1. Contributions of This Study

This study primarily contributed to providing a comprehensive review of current vision-based UAV navigation techniques in a qualitative and comparative manner. After introducing the basic knowledge of different types of UAVs and their applications, we present computer vision-based applications and working principles of UAV navigation systems. The design issues of vison-based UAV navigation systems are also summarized. Then, we present a taxonomy of all the existing vision-based navigation techniques for UAVs. Based on this categorization, we review the existing vision-based UAV navigation techniques in terms of their main features and operational characteristics. The navigation techniques were qualitatively compared in terms of various features, parameters, advantages, and limitations. We then discuss open issues and challenges for future research and development.

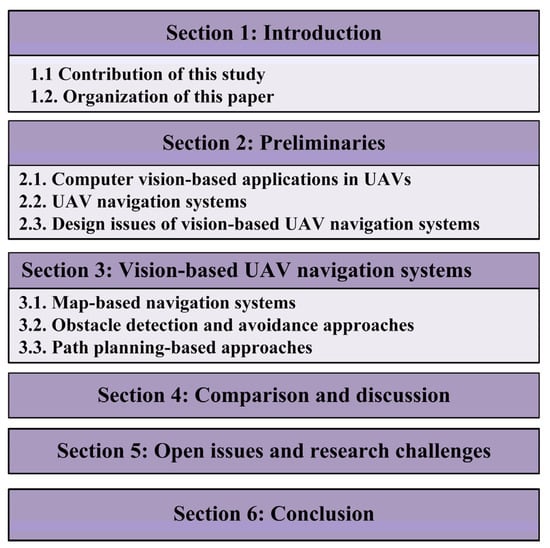

1.2. Organization of This Paper

This survey is organized into six sections, as shown in Figure 1. Below is an outline of the remainder of the paper.

Figure 1.

Outline of the survey.

In Section 2, we present various applications of computer vision in UAVs. We also present a comprehensive overview of UAV navigation systems. The critical design issues are discussed in this section. In Section 3, we discuss and review various vision-based UAV navigation systems. We present a taxonomy of the existing vision-based navigation systems. The working principle of each navigation technique is discussed in detail. In Section 4, we provide a comparative study of the existing vision-based navigation techniques with respect to various criteria. The major features, key characteristics, advantages, and limitations are summarized in a tabular manner and rigorously discussed. In Section 5, we present open issues and research challenges associated with vision-based UAV navigation techniques. Finally, the paper is concluded in Section 6.

2. Preliminaries

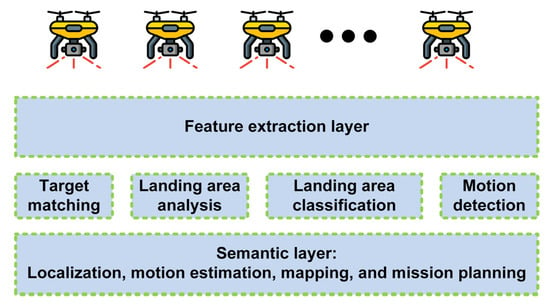

Computer vision plays an integral role in most UAV applications. Applications range from regular aerial photography to more complex operations, such as rescue operations and aerial refueling. To provide reliable decisions and manage tasks, they require high levels of accuracy. Computer vision and image processing have proven their efficiency in a variety of applications for UAVs. The applications of autonomous drones are interesting, but they also pose challenges.

2.1. Computer Vision-Based Applications in UAVs

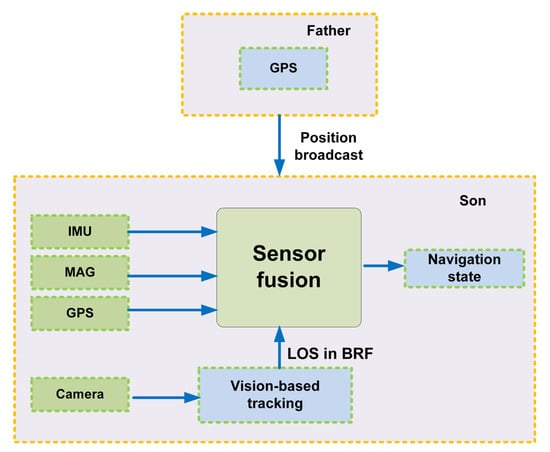

A peer-to-peer connection is established between UAVs and, thus, UAVs can coordinate and collaborate with each other [21]. An advantage of using a single cluster is that it is suitable for homogeneous and small-scale missions. UAVs performing multiple certain missions require a multi-cluster network. Every cluster head is responsible for downlink communication and communication with other cluster heads. In addition to VTOL vehicles, fixed-wing unmanned aerial vehicles also require autonomous takeoff and landing. To address the issue of vision-based takeoff and landing, different solutions have been proposed. Lucena et al. described a method that uses a back-stepping controller to implement autonomous takeoff and landing on a stationary landing pad [22]. The inertial measurement unit (IMU) and GPS data were fused with a Kalman filter to estimate the position, attitude, and speed of the quadcopter. To measure the distance between the landing pad and quadcopter, a light detection and ranging (LIDAR) sensor was used instead of a spatial device [23]. According to the results, the quadcopter was capable of autonomous takeoffs and landings. However, this system has the disadvantage of not being accurate in determining the attitude of the quadcopter, which is caused by errors in IMU and GPS measurements [24].

Both military and civil applications of UAVs rely on aerial imaging. Surveillance by UAVs is possible over battlefields, coasts, borders, forests, highways, and outdoor environments. In order to optimize the solutions in terms of time, the number of UAVs, autonomy, and other factors, different methods and approaches have been proposed. In an evaluation approach presented by Hazim et al. [25], the proposed algorithms and methods were evaluated with respect to their performance in autonomous surveillance tasks.

In recent years, aerial inspection has become one of the most popular applications for UAVs (primarily rotorcraft). Additionally, for safety and reduction in human risk, UAVs reduce operational costs and inspection time. Nevertheless, image stability must be maintained for all types of maneuvers [26]. In a variety of terrains and situations, UAVs are capable of inspecting buildings, bridges, wind turbines, boilers of power plants, power lines, and tunnels [27].

Air-to-air refueling, also known as autonomous aerial refueling (AAR) or in-flight refueling, consists of two main techniques [28]: (1) boom-and-receptacle refueling (BRR), which involves moving a flying tube (boom) from a tanker aircraft to a receiver aircraft to connect it to its receptacle; and (2) drogue-and-probe refueling (PDR), in which the receiver releases a flexible hose (drogue) and the tanker maintains its position to insert a rigid probe into the drogue. Tanker pilots are responsible for these complex duties and need to be well trained. Therefore, remote control of AAR operations further complicates UAVs. GPS and INS are used with various techniques to determine the position of the tanker relative to the receiver aircraft. Nevertheless, there are two main disadvantages associated with these techniques. First, GPS data may not be available in certain cases, especially if the receiver aircraft is larger than the tanker and interferes with the satellites. Another limitation is the integration drift of the INS measurements. Table 2 illustrates the use of computer vision in various UAV applications.

Table 2.

Computer vision-based UAV applications.

2.2. UAV Navigation Systems

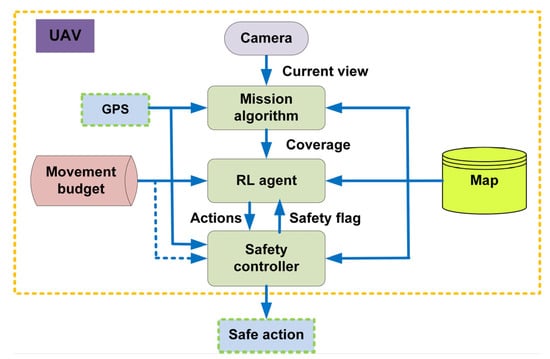

Autonomy and flight stabilization accuracy have gained further importance in today’s UAVs. Navigation systems and their supporting subsystems are critical components of autonomous UAVs. Figure 2 demonstrates the use of the information from various sensors that the navigation system uses to estimate the position, velocity, and orientation of the UAV.

Figure 2.

Typical configuration of a UAV navigation system.

In addition, support systems perform relevant tasks, in particular, the detection and tracking (static or dynamic) or avoidance of obstacles. Increased levels of autonomy and flight stabilization require a robust and efficient navigation system [29]. Monocular cameras can be used to implement computer vision algorithms to enhance navigation. Navigation systems can be split into three main subsystems, as shown in Table 3: pose estimation, which uses two- and three-dimensional (3D) representations to estimate the position and attitude of the UAV; obstacle detection and avoidance, which detects and feeds back the position of the obstacles that it encounters; visual servoing (VS), which manages and sends maneuver commands to keep the UAV stable and following its path throughout its flight; and finally, the position estimation subsystem.

Table 3.

Subsystems of a vision-based UAV navigation system.

2.2.1. Pose Estimation

Pose estimation includes estimating the position and orientation of UAVs during motion based on data obtained from several sensors, including GPS, IMU, vision, laser, and ultrasonic sensors. Information obtained from various sensors can be separated or combined. Navigation and mapping processes require the estimation of position as a fundamental component.

GPS

The GPS, also known as a satellite-based navigation system (SNS), is considered one of the best methods for providing 3D positions to unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs), UAVs, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) [30]. GPS is commonly used to determine a UAV’s location during localization. Hui et al. used GPS to localize UAVs [31]. According to the authors, differential GPSs (DGPSs) demonstrate the effectiveness of this positioning method. DGPS reduces errors (satellite clock, satellite position, and delay errors) that cannot be reduced by the GPS receiver alone. To increase the accuracy of the positioning information, DGPS was integrated with a single-antenna receiver [26]. The precision of these systems is directly affected by the number of connected satellites. Buildings, forests, and mountains can significantly reduce satellite visibility in an urban environment. In addition, GPS is rendered ineffective in the absence of satellite signals, such as when flying indoors. An expensive external localization system, such as the Vicon motion capture system [32], is used to capture the motion of a UAV in an indoor environment.

GPS-Aided Systems

While stand-alone GPS can be useful for estimating vehicle location, it can also cause errors due to poor reception and jamming of satellite signals, resulting in loss of navigational data. For the purpose of preventing catastrophic control actions that may be caused by errors in estimating position, UAVs require a robust positioning system, for which various approaches are used. GPS-aided systems are an example of these approaches. The gathered GPS data are fused with data from other sensors. This multisensory fusion can consist of two or more sensors [33]. One of the most popular configurations is the GPS/INS approach, where the data from the INS and GPS are merged to compensate for the errors generated by both sensors and increase the accuracy of localization. Using a linear Kalman filter, Hao et al. [34] fused the data from a multiple-antenna GPS with the information from the onboard INS. Although the experiments were conducted on a ground vehicle, this algorithm was implemented for the UAVs.

Vision-Based Systems

As a result of the limitations and shortcomings of the previous systems, the vision-based pose estimation approaches have become an important topic in the field of intelligent vehicles [35]. In particular, visual pose estimation methods are based on information provided by the visual sensors of cameras. A variety of approaches and methods have been suggested, regardless of the type of vehicle and the purpose of the task. Different types of visual information are used in these methods, such as horizon detection, landmark tracking, and edge detection [36]. A vision system can also be classified by its structure as monocular, binocular, trinocular, or omnidirectional [37]. To solve the vision-based pose estimation problem, two well-known philosophies have been proposed: visual simultaneous localization and mapping (VSLAM) and visual odometry (VO).

As a general principle, VSLAM algorithms [38] aim at constructing a consistent map of the environment and simultaneously estimating the position of the UAV within the map. Different camera-based algorithms have been proposed to perform VSLAM on UAVs, including parallel tracking and mapping (PTAM) [39] and mono-simultaneous localization and mapping (MonoSLAM) [40], which were discussed by Michael et al. [41]. The UAV orientation and position were estimated using the VO algorithms [42]. The estimation processes are conducted sequentially (frame by frame) to determine the pose of the UAV. Monocular cameras or multiple-camera systems can be used to gather visual information. In contrast to VSLAM, VO algorithms calculate trajectories at each instant in time without preserving the previous positions. The VO method was first proposed by Nistér [43] using the traditional wheel odometry approach. A Harris corner [44] was detected in each frame to incrementally estimate the ground vehicle motion. By implementing a 5-point algorithm and random sample consensus (RANSAC), image features were matched between two frames and linked to the image trajectory [45].

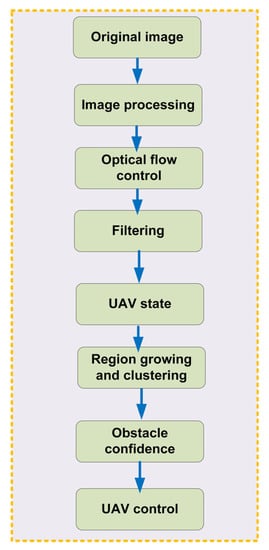

2.2.2. Visual Obstacle Detection and Avoidance

Autonomous navigation systems must detect and avoid obstacles. Furthermore, this process is considered challenging, particularly for vision-based systems. Obstacle detection and avoidance have been solved using different approaches in vision-based navigation systems. A 3D model of the obstacle within the environment was constructed using approaches such as those suggested by Muhovic et al. [46]. The depth (distance) of obstacles has also been calculated in other studies [47]. Stereo cameras have been introduced to estimate the proximity of obstacles using techniques based on stereo cameras. By analyzing the disparity images and viewing angle, the system determines the size and position of the obstacles. In addition, this method calculates the relationship between the size of a detected obstacle and its distance from the UAV.

2.2.3. Visual Servoing

In UAV control systems, visual servoing is the process of using visual sensor information as feedback [48]. To stabilize UAVs, different inner-loop control systems have been employed, such as proportional–integral–derivative (PID), optimal control, sliding mode, fuzzy logic, and cascade control. Chen et al. [49] provided a detailed analysis of principles and theories related to UAV flight control systems. Altug et al. [50] evaluated two controllers (mode-based feedback linearizing and backstepping-like control) based on visual feedback. An external camera and onboard gyroscopes were used to estimate the UAV angles and positions. According to the simulations, feedback stabilization was less effective than the backstopping controller.

2.3. Design Issues of Vision-Based UAV Navigation Systems

In this section, we introduce a general framework for evaluating navigation systems. An ideal navigation system should be highly accurate, accessible, scalable, and cost-effective. Additionally, the navigation system should be simple to install and maintain and have low computational complexity.

2.3.1. Accuracy

The accuracy of a navigation system is the most important performance indicator. The presence of obstacles, multipath effects, dynamic scenes, and other factors may obstruct precise measurements of an agent in certain application environments. Sensors and applications play a significant role in determining the accuracy of measurements. Camera-only systems are more susceptible to featureless or incorrectly tracked features. Although significant progress has been made in vision-based navigation, many problems remain to be solved in order to realize a fully autonomous navigation system. Some of them are autonomous obstacle avoidance, optimal path discovery in dynamic scenarios, and task assignment in real time. Furthermore, UAV navigation necessitates a global or local 3D representation of the environment, and the added dimension requires more computing and storage. When a UAV navigates a large area for an extended period of time, it faces significant obstacles. Furthermore, the motion blur generated by rapid movement and rotation can easily cause tracking and localization failures during flight.

2.3.2. Availability

To effectively navigate, UAV systems must have access to technologies that do not require proprietary hardware and are readily available. As a result, navigation systems are likely to be adopted on a large scale. A wide range of UAVs are equipped with relatively inexpensive GPS chips. However, GPS chips do not provide high-accuracy navigation results and exhibit errors of up to several meters. With a partial or complete 3D map, we should not only find a collision-free path, but also minimize the length of the path and energy consumed. Although creating a 2D map is a relatively straightforward process, creating a 3D map becomes increasingly difficult as the dynamic and kinematic restrictions of UAVs become more complex. The local minimum problem still plagues modern path-planning algorithms because of this NP-hard problem. Thus, researchers continue to study and develop robust and effective methods for global optimization.

2.3.3. Complexity and Cost

The complexity of a navigation system is an important consideration in the design of drone communication systems and is usually associated with greater power requirements, infrastructure demands, and computational demands. In the case of an autonomous mission, a computationally complex system may not be able to operate on a miniature drone. Ideally, a system does not require any additional infrastructure costs or rare or unusual devices or systems. Accordingly, cost, accuracy, generalization, and scalability are determined by the complexity of the system. Even though UAVs and ground mobile robots have similar navigation systems, UAV navigation needs extensive development. To fly safely and steadily, the UAV must process a sizable amount of sensor data in real time, particularly for image processing, which considerably increases computational complexity. Consequently, navigating within the limits of low battery consumption and limited computational capacity has become a key challenge for UAVs.

2.3.4. Generalization

The degree of generalization is another aspect that should be considered when assessing the applicability of technologies. Practically, we would like to use the same type of hardware and algorithms for all navigation problems. However, each problem requires different features, such as size, weight, cost, accuracy, and operating environment. A single method cannot be applied in all situations. UAVs can be equipped with a variety of sensors because these sensors are becoming smaller and more precise. However, difficulties are likely to arise when combining several types of sensor data exhibiting varied noise characteristics and poor synchronization. Despite this, we anticipate superior pose prediction via multi-sensor data fusion, which will subsequently improve navigation performance. As IMUs are becoming smaller and less expensive, the integration of IMUs and visual measurements is gaining considerable traction.

4. Comparison and Discussion

In this section, we compare the existing vision-based navigation systems. We compared the reviewed vision-based navigation systems among the groups. Table 4 summarizes the analysis of the various map-based UAV navigation systems in terms of types, methods used, the main theme of the article, functions, network environment, advantages, and limitations of the proposed approach. Similarly, Table 5 and Table 6 summarize the comparison of various approaches to object detection and path planning for UAV navigation based on their proposed methods, main ideas, and functions. It can be observed from Table 5 and Table 6 that machine-learning-based approaches exhibit high performance but require considerable computing power. The navigator aims to fly the UAV successfully without an obstacle collision. Additionally, it determines the shortest path to the destination. Furthermore, it is used to define the appropriate landing sites for rescue operations. Navigators typically include three modules: localization, mapping, and path planning.

Table 4.

Comparison of map-based UAV navigation systems.

Table 5.

Comparison of obstacle-detection-based UAV navigation systems.

Table 6.

Comparison of path-planning-based UAV navigation systems.

The map-based navigation approaches, widely used for UAVs, are presented in Table 4. Due to the requirement for a camera-based navigation system over scenes with uniform textures, a camera-based navigation system cannot infer geometrical information from an image. Furthermore, perception algorithms should be resilient to recurrent outlier measurements generated by low-level image processing, such as optical flow and feature matching. We also presented the advantages and drawbacks of each navigation technique. The main advantage of map-based UAV navigation systems is their simplicity. Nevertheless, several disadvantages, such as limited accuracy, slow motion, no visualization, limited applications, and limited memory management, are present owing to discarding depth and relying on sensors for planning. System complexity and computational cost are major limitations of map-based UAV navigation systems. The complexity and computational costs of map-based UAV navigation systems are limited.

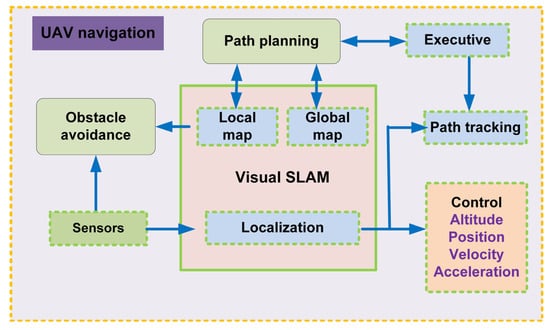

A comprehensive comparison of the obstacle detection and avoidance approaches reviewed is presented in Table 5. Localization provides an exploration of the flight area. Several approaches can be used, including GPS as a reference frame model. The next step is to analyze the data and create a map that contains details of the obstacle positions. In the map, each cell was classified as occupied or unoccupied. In other words, it accurately determined the locations of the obstacles. All path-planning and object-detection-based navigation techniques produced highly accurate results. A few techniques have several shortcomings, such as a lack of visualization, limited applications, and limited memory organization. However, the SLAM-based approach showed excellent accuracy in object detection, but required a high computational cost.

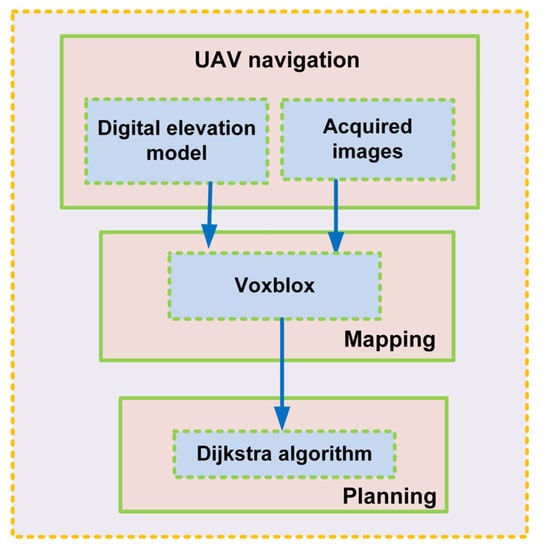

Finally, in Table 6, we provided a comparison of path-planning approaches for navigation systems concerning various performance parameters. The path-planning module uses an appropriate search algorithm to determine the shortest route. This process is known as mapping. Therefore, navigators depend on visual approaches to refine this process. Various algorithms, such as Octomap, Voxblox, and ESDFs, have been developed for navigation. Furthermore, the map provides information about factors used as a cost function in the path-planning module, such as depth, distance, and energy consumption. Eventually, algorithms such as Dijkstra’s algorithm and jump point search are used for path optimization. The machine learning (ML)-based approach showed higher accuracy but required high computational costs.

5. Open Issues and Research Challenges

In this section, we summarize and discuss important open issues and research challenges that motivate further research in this emerging domain. As crucial challenges are introduced by the increasing demand, we discuss the four major issues of scalability, computational power, reliability, and robustness in vision-based UAV navigation systems.

5.1. Scalability

In this article, the major contributions in each category of vision-based navigation, perception, and control for unmanned aerial systems are discussed. Visual sensor integration in UAVs is an area of research that attracts enormous resources but lacks solid experimental evaluation. Compared with conventional robots, UAVs can provide a challenging testbed for computer vision applications for a variety of reasons. Typically, the dimensions of an aircraft are larger than those of a mobile robot. Thus, image-processing algorithms must be capable of robustly providing visual information in real time and have the ability to compensate for rough changes in the image sequence and changes in 3D information. However, SLAM algorithms, for visual applications, have been developed by the computer-vision society. However, most of them cannot be directly utilized in UAVs because of the computational power and energy limitations of UAVs. More specifically, aircraft have a limited ability to generate thrust to maintain their airborne status, which limits their capacity for sensing and computing. To avoid instabilities associated with the fast dynamics of aerial platforms, minimizing delays and compensating for noise in state computations is essential. Unlike ground vehicles, UAVs cannot simply cease operations in the presence of considerable uncertainty in state estimation, resulting in incoherent control commands to the aerial vehicle.

5.2. Computational Power

The UAV may possibly exhibit unpredictable behavior, such as an increase or decrease in speed or oscillation, and may ultimately crash if the computational power is insufficient to update the velocity and attitude in time. UAVs have the ability to operate at a variety of altitudes and orientations, resulting in a sudden appearance and disappearance of obstacles and targets; therefore, computer vision algorithms must be able to respond very quickly to changes in the scene (dynamic scenery). Notably, the majority of the presented contributions assume that UAVs will fly at low speeds to compensate for the rapid changes in the scene. Consequently, dynamic scenes pose a significant challenge. Considering the large area of aerial platforms, resulting in large maps containing more information than ground vehicles, which is another challenge in SLAM frameworks, is important. When pursuing a target, object tracking methods must be robust to occlusions, image noise, vehicle disturbances, and illumination variations. When the target remains within the field of view but is obscured by another object or not clearly visible from the sensor, the tracker must continue to function to estimate the target’s trajectory, recover the process, and work in harmony with the UAV controller. As a result, highly sophisticated and robust control schemes are required for optimally closing the loop using visual data. Computer vision applications have undeniably moved beyond their infancy and have made great strides toward understanding and approaching autonomous aircraft. Because various positions, attitudes, and rate controllers have been proposed for UAVs, this topic has attracted considerable attention from the research community. Therefore, to achieve greater levels of autonomy, a reliable link must be established between vision algorithms and control theory.

5.3. Reliability

To increase the reliability of a vision system, the camera exposure time can be automatically adjusted by software. Batteries are the primary source of power for UAVs, allowing them to perform all their functions; however, their capacity is limited for lengthy missions. Furthermore, marker and ellipse detection techniques may be further enhanced by merging them with the Hough transform and machine learning approaches. For movement analysis of possible impediments, the optical flow approach must be combined with additional methods. Optical flow calculation can be used for real-time scene analysis, when ground truth for evaluating the design is nonexistent. In recent years, more sophisticated image-based techniques have been studied because most of the work does not consider dynamic impediments.

5.4. Robustness

With the rapid advancement of computer vision and the growing popularity of mini-UAVs, their combination has become a hot topic of research. This study focused on three areas of vision-based UAV navigation. The key to autonomous navigation is localization and mapping, which also provides position and environmental information to UAVs. Obstacle avoidance and path planning are critical for safe and swift UAV arrival at a target area. The topic of vision-based UAV navigation, which relies solely on visual sensors to navigate in dynamic, complex, and large-scale settings, is yet to be solved and is a burgeoning field of study. We also discovered that the limited power and perceptual capabilities of a single UAV make it impossible for it to perform certain tasks. With the advancement of autonomous navigation, many UAVs can simultaneously perform similar tasks. Several RL-based approaches have been proposed for both indoor and outdoor environments, based on known targets. This remains undecipherable for unknown destination targets. Moreover, multiple targets were identified. In other words, finding an optimal path-based algorithm for multiple unknown targets is an open issue. Energy consumption is also an open issue in this sector. For optimal path selection, applying the least-squares or K-means algorithm is worthwhile. The sensor nodes used in the architecture may be dead or have hidden node problems.

6. Conclusions

Recently, UAVs have gained increasing attention in this research field. The navigator aims at successfully flying the UAV without colliding with obstacles. Navigation techniques for UAVs are imperative issues that have drawn significant attention from researchers. Over the past few years, several UAV navigation techniques have been proposed. A navigator typically consists of three modules: localization, mapping, and path planning. Localization provides an exploration of the flight area. Several navigation approaches can be used for navigation, including GPS, reference frames, and models. The next step is analyzing the data and creating a map that contains details of the obstacle positions. In this map, each cell is classified as occupied or unoccupied. In other words, it accurately determines the position of the obstacles. Then, it feeds the path-planning module with the details for determining the shortest path by applying a proper search algorithm, a process known as mapping. Recently, the advantages and improvements of computer vision algorithms have been demonstrated through real-world results in challenging conditions, such as pose estimation, aerial obstacle avoidance, and navigation. In this paper, we presented a brief overview of vision-based UAV navigation systems and a taxonomy of existing vision-based navigation techniques. Various vision-based navigation techniques have been thoroughly reviewed and analyzed based on their capabilities and potential utility. Moreover, we provided a list of open issues and future research challenges at the end of the survey.

Multiple potential research directions can be provided for further research into vision-based UAV navigation systems. Currently, UAVs possess several powerful characteristics that could lead to their use as pioneering elements in a wide variety of applications in the near future. Special features, such as lightweight chassis and versatile movement, are combined with certain characteristics, such as versatile movement. Therefore, there is a potential that could be tapped using onboard sensors; therefore, UAVs have received considerable research attention. Today, the scientific community focuses on developing more effective schemes for using visual servoing technologies and SLAM algorithms. Furthermore, many resources are now devoted to visual–inertial state estimation to combine the advantages of both areas. Developing a reliable visual–inertial state estimation system will be a standard procedure and fundamental element of every aerial agent. UAV position and orientation are estimated using visual cues from cameras and inertial measurements from an IMU. Furthermore, elaborate schemes for online mapping will be investigated and refined for dynamic environments. The development of robotic arms and tools for UAVs, which can be used for aerial manipulation and maintenance, is currently underway. Multi-sensor fusion improves localization performance by combining information from multiple sensors, such as cameras, LIDAR, and GPS. Future research will examine floating-base manipulators for either single or cooperative task completion. Because of the varying center of gravity and external disturbances caused by the interaction, operating an aerial vehicle with a manipulator is not a straightforward process, and many challenges must be overcome. This capability entails challenging vision-based tasks and is expected to revolutionize the use of UAVs. Further research in this area is necessary to overcome these challenges and reduce the limitations of the current approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Y.A., M.M.A. and S.M.; methodology, M.M.A.; validation, M.Y.A. and S.M.; investigation, M.Y.A. and M.M.A.; resources, M.Y.A. and M.M.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Y.A. and M.M.A.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a research fund from Chosun University (2022).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on improving the quality of this paper. We would like to express our sincere thanks to Masud An Nur Islam Fahim, Nazmus Saqib, and Shafkat Khan Siam for explaining vision-based navigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wei, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, N.; Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wu, H.; Feng, Z. UAV-assisted data collection for internet of things: A survey. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15460–15483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. Routing protocols for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks: A survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 99694–99720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S.; Shen, J. Topology control algorithms in multi-unmanned aerial vehicle networks: An extensive survey. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 207, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Moh, S. Task assignment algorithms for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks: A comprehensive survey. Veh. Commun. 2022, 35, 100469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.; Kumar, P.; George, R.C.; Yuvaraj, T.P.; Philip, D.; Ghosh, A.K. Real-time object detection and recognition using fixed-wing Lale VTOL UAV. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 20738–20747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. Localization and clustering based on swarm intelligence in UAV Networks for Emergency Communications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 8958–8976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Joint Topology Control and routing in a UAV swarm for crowd surveillance. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2022, 204, 103427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanellakis, C.; Nikolakopoulos, G. Survey on computer vision for uavs: Current developments and trends. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2017, 87, 141–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaff, A.; Martín, D.; García, F.; de Escalera, A.; María Armingol, J. Survey of computer vision algorithms and applications for unmanned aerial vehicles. Expert Syst. Appl. 2018, 92, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. Bio-inspired approaches for energy-efficient localization and clustering in UAV networks for monitoring wildfires in remote areas. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 18649–18669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Lu, Z. A visual navigation framework for the aerial recovery of uavs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 5019713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. Location-aided delay tolerant routing protocol in UAV networks for Post-Disaster Operation. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 59891–59906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclea, V.-C.; Nedevschi, S. Monocular depth estimation with improved long-range accuracy for UAV environment perception. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5602215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Pu, F.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z. Detection, tracking, and geolocation of moving vehicle from UAV using monocular camera. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 101160–101170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.N.; Kumar, A.; Jha, A.; Cenkeramaddi, L.R. Embedded Sensors, Communication Technologies, computing platforms and Machine Learning for uavs: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 1807–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Xie, B.; Li, J.; Liu, L. Panoramic UAV surveillance and recycling system based on structure-free camera array. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 25763–25778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. A q-learning-based topology-aware routing protocol for flying ad hoc networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 1985–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Cui, J.; Liao, F.; Lao, M.; Lin, F.; Teo, R.S. Vision-aided multi-uav autonomous flocking in GPS-denied environment. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Pei, L.; Zou, D.; Liu, P. Optical flow-based gait modeling algorithm for pedestrian navigation using smartphone sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 6797–6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Chen, K.; Chen, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S. Robust visual-lidar simultaneous localization and mapping system for UAV. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 6502105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. A survey on cluster-based routing protocols for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 498–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lucena, A.N.; Da Silva, B.M.; Goncalves, L.M. Double hybrid tailsitter unmanned aerial vehicle with vertical takeoff and landing. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 32938–32953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diels, L.; Vlaminck, M.; De Wit, B.; Philips, W.; Luong, H. On the optimal mounting angle for a spinning lidar on a UAV. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 21240–21247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Moh, S. JRCS: Joint Routing and charging strategy for logistics drones. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 21751–21764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (uavs): A survey on civil applications and key research challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, O.-H.; Ban, K.-J.; Kim, E.-K. Stabilized UAV flight system design for Structure Safety Inspection. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology, PyeongChang, Republic of Korea, 16–19 February 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Poudel, S.; Moh, S. Medium access control protocols for flying Ad Hoc Networks: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 4097–4121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Mu, C.; Wu, B. A survey of vision based autonomous aerial refueling for unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2012 Third International Conference on Intelligent Control and Information Processing, Dalian, China, 15–17 July 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ren, X.; Han, S.; Luo, S. UAV Vision aided INS/odometer integration for Land Vehicle Autonomous Navigation. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 4825–4840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Survey on Q-learning-based position-aware routing protocols in flying ad hoc networks. Electronics 2022, 11, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, Y.; Xhiping, C.; Shanjia, X.; Shisong, W. An unmanned air vehicle (UAV) GPS location and Navigation System. ICMMT’98. In Proceedings of the 1998 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology, (Cat. No.98EX106), Beijing, China, 18–20 August 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, L.L.; Leal, L.; Oliveira, T.R.; Cunha, J.P.V.S.; Revoredo, T.C. Unmanned Quadcopter control using a motion capture system. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2016, 14, 3606–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, F.; García, M.; Maza, I.; Viguria, A.; Ollero, A. A Precise and GNSS-Free Landing System on Moving Platforms for Rotary-Wing UAVs. Sensors 2019, 19, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xu, A.; Sui, X.; Wang, Y. A Modified Extended Kalman Filter for a Two-Antenna GPS/INS Vehicular Navigation System. Sensors 2018, 18, 3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavel, M.I.; Tan, S.Y.; Abdullah, A. Vision-Based Autonomous Vehicle Systems Based on Deep Learning: A Systematic Literature Review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, Y.; Miao, Z.; Zhong, H.; Fierro, R. Low-complexity control for vision-based landing of quadrotor UAV on unknown moving platform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5348–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sieira, A.; Cores, D.; Mucientes, M.; Bugarín, A. Autonomous Navigation for uavs managing motion and sensing uncertainty. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 126, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresson, G.; Alsayed, Z.; Yu, L.; Glaser, S. Simultaneous localization and mapping: A survey of current trends in autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2017, 2, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Ye, D. Coarse semantic-based motion removal for robust mapping in dynamic environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 74048–74064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison, A.J.; Reid, I.D.; Molton, N.D.; Stasse, O. MonoSLAM: Real-time single camera slam. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blösch, M.; Weiss, S.; Scaramuzza, D.; Siegwart, R. Vision based MAV navigation in unknown and unstructured environments. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation 2010, Anchorage, AK, USA, 3–7 May 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Yang, T.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y. A Monocular Visual Odometry Method Based on Virtual-Real Hybrid Map in Low-Texture Outdoor Environment. Sensors 2021, 21, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistér, D.; Naroditsky, O.; Bergen, J. Visual odometry for ground vehicle applications. J. Field Robot. 2006, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.G.; Stephens, M.J. A Combined Corner and Edge Detector. In Proceedings of the Alvey Vision Conference, Citeseer, Manchester, UK, 31 August–2 September 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, X.; Fu, B.; Huang, S.; Xiong, R. 2-entity random sample consensus for robust visual localization: Framework, methods, and verifications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 4519–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhovic, J.; Mandeljc, R.; Bovcon, B.; Kristan, M.; Pers, J. Obstacle tracking for unmanned surface vessels using 3-D Point Cloud. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2020, 45, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrizio, F.; De Luca, A. Real-time computation of distance to dynamic obstacles with multiple depth sensors. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2017, 2, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keipour, A.; Pereira, G.A.S.; Bonatti, R.; Garg, R.; Rastogi, P.; Dubey, G.; Scherer, S. Visual Servoing Approach to Autonomous UAV Landing on a Moving Vehicle. Sensors 2022, 22, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-W.; Hung, H.-A.; Yang, P.-H.; Cheng, T.-H. Visual Servoing of a Moving Target by an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Sensors 2021, 21, 5708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altug, E.; Ostrowski, J.P.; Mahony, R. Control of a quadrotor helicopter using visual feedback. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (Cat. No.02CH37292), Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 May 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, B.K.P.; Schunck, B.G. Determining optical flow. Artif. Intell. 1981, 17, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, B.D.; Kanade, T. An Iterative Image Registration Technique with an Application to Stereo Vision. In Proceedings of the 7th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence—Volume 2, Vancouver, Canada, 24–28 August 1981; pp. 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Victor, J.; Sandini, G.; Curotto, F.; Garibaldi, S. Divergent stereo for robot navigation: Learning from bees. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New York, NY, USA, 15–17 June 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herissé, B.; Hamel, T.; Mahony, R.; Russotto, F.-X. Landing a VTOL unmanned aerial vehicle on a moving platform using optical flow. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2012, 28, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, J.; Humenberger, M. Movement detection based on dense optical flow for unmanned aerial vehicles. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Chen, X. Novel approach to position and orientation estimation in vision-based UAV navigation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2010, 46, 687–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, Y. Novel technique for vision-based UAV navigation. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2011, 47, 2731–2741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESRI Inc. ArcView 8.1 and ArcInfo 8.1. 2004. Available online: http://www.esri.com/ (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- USGS National Map Seamless Server. 2010. Available online: http://seamless.usgs.gov (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Khansari-Zadeh, S.M.; Saghafi, F. Vision-based navigation in autonomous close proximity operations using Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2011, 47, 864–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.-M.; Tsiotras, P.; Zhang, G.; Holzinger, M. Robust feature detection, acquisition and tracking for relative navigation in space with a known target. In Proceedings of the AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control (GNC) Conference, Boston, MA, USA, 8–11 August 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Allinson, N.M. A comprehensive review of current local features for Computer Vision. Neurocomputing 2008, 71, 1771–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szenher, M.D. Visual Homing in Dynamic Indoor Environments. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1842/3193 (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Cesetti, A.; Frontoni, E.; Mancini, A.; Zingaretti, P.; Longhi, S. A Vision-based guidance system for UAV navigation and safe landing using natural landmarks. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2009, 57, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wertz, J.R. Spacecraft Attitude Determination and Control; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Vetrella, A.R.; Fasano, G. Cooperative UAV navigation under nominal GPS coverage and in GPS-challenging environments. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 2nd International Forum on Research and Technologies for Society and Industry Leveraging a better tomorrow (RTSI) 2016, Bologna, Italy, 7–9 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, J.; Ricard, B.; Laurendeau, D. Mapping and exploration of complex environments using persistent 3D model. In Proceedings of the Fourth Canadian Conference on Computer and Robot Vision (CRV ‘07) 2007, Montreal, QC, Canada, 28–30 May 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutmann, J.-S.; Fukuchi, M.; Fujita, M. 3D perception and Environment Map Generation for humanoid robot navigation. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2008, 27, 1117–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryanovski, I.; Morris, W.; Xiao, J. Multi-volume occupancy grids: An efficient probabilistic 3D Mapping Model for Micro Aerial Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 2010, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, K.C.; Naidu, V.P.; Singhal, V.; Tanuja, B.M. Application of vision based techniques for UAV position estimation. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Research Advances in Integrated Navigation Systems (RAINS) 2016, Bangalore, India, 6–7 May 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Fernando, X. Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) and Data Fusion in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Recent Advances and Challenges. Drones 2022, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, H.P. The stanford CART and the CMU Rover. Proc. IEEE 1983, 71, 872–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davison Real-time simultaneous localisation and mapping with a single camera. In Proceedings of the Ninth IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2003, Nice, France, 13–16 October 2003. [CrossRef]

- Klein, G.; Murray, D. Parallel Tracking and mapping for small AR workspaces. In Proceedings of the 2007 6th IEEE and ACM International Symposium on Mixed and Augmented Reality 2007, Nara, Japan, 13–16 November 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahon, I.; Williams, S.B.; Pizarro, O.; Johnson-Roberson, M. Efficient view-based slam using visual loop closures. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 1002–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, K.; Chung, S.-J.; Clausman, M.; Somani, A.K. Monocular Vision Slam for indoor aerial vehicles. 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems 2009, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–15 October 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Chen, Y.Q. Multiple UAV formations for cooperative source seeking and contour mapping of a radiative signal field. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2013, 74, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgaerts, L.; Bruhn, A.; Mainberger, M.; Weickert, J. Dense versus sparse approaches for estimating the Fundamental Matrix. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2011, 96, 212–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranftl, R.; Vineet, V.; Chen, Q.; Koltun, V. Dense monocular depth estimation in complex dynamic scenes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavle, H.; De La Puente, P.; How, J.P.; Campoy, P. VPS-SLAM: Visual planar semantic slam for aerial robotic systems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 60704–60718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleynikova, H.; Taylor, Z.; Fehr, M.; Siegwart, R.; Nieto, J. Voxblox: Incremental 3D Euclidean signed distance fields for on-board MAV Planning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) 2017, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 24–28 September 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Chang, C.-W.; Wen, C.-Y. Multilayer mapping kit for autonomous UAV navigation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 31493–31503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhu, D. A new method on motion planning for mobile robots using Jump Point Search and bezier curves. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 172988142110192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, G.; Malis, E.; Rives, P. An efficient direct approach to visual slam. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2008, 24, 969–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newcombe, R.A.; Lovegrove, S.J.; Davison, A.J. DTAM: Dense tracking and mapping in real-time. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Vision 2011, Barcelona, Spain, 6–13 November 2011; pp. 2320–2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.; Schöps, T.; Cremers, D. LSD-slam: Large-scale direct monocular slam. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummerle, R.; Grisetti, G.; Strasdat, H.; Konolige, K.; Burgard, W. G2O: A general framework for graph optimization. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Jianmei, S. Research of autonomous vision-based absolute navigation for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. In Proceedings of the 2016 14th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision (ICARCV) 2016, Phuket, Thailand, 13–15 November 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Pizzoli, M.; Scaramuzza, D. SVO: Fast semi-direct monocular visual odometry. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Hong Kong, China, 31 May–7 June 2014; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouza, G.N.; Kak, A.C. Vision for Mobile Robot Navigation: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 237–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynen, S.; Achtelik, M.W.; Weiss, S.; Chli, M.; Siegwart, R. A robust and modular multi-sensor fusion approach applied to MAV Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magree, D.; Johnson, E.N. Combined laser and vision-aided inertial navigation for an indoor unmanned aerial vehicle. In Proceedings of the American Control Conference 2014, Portland, OR, USA, 4–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosiewski, Z.; Ciesluk, J.; Ambroziak, L. Vision-based obstacle avoidance for unmanned aerial vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2011 4th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing 2011, Shanghai, China, 15–17 October 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, Z.; Aremanda, Y.; Friess, W.A.; Landis, E.N. Impact of UAV Hardware Options on Bridge Inspection Mission Capabilities. Drones 2022, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strübbe, S.; Stürzl, W.; Egelhaaf, M. Insect-inspired self-motion estimation with dense flow fields—An adaptive matched filter approach. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haag, J.; Denk, W.; Borst, A. Fly Motion Vision is based on Reichardt detectors regardless of the signal-to-noise ratio. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 16333–16338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffier, F.; Viollet, S.; Amic, S.; Franceschini, N. Bio-inspired optical flow circuits for the visual guidance of Micro Air Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, ISCAS ‘03, Bangkok, Thailand, 25–28 May 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, O.J.; Lindemann, J.P.; Egelhaaf, M. A bio-inspired collision avoidance model based on spatial information derived from motion detectors leads to common routes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015, 11, e1004339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Armendariz, M.A.; Calvo, H. Visual slam and obstacle avoidance in real time for Mobile Robots Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Mechatronics, Electronics and Automotive Engineering 2014, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 18–21 November 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhihai, H.; Iyer, R.V.; Chandler, P.R. Vision-based UAV flight control and obstacle avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2006 American Control Conference 2006, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 14–16 June 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.-Y.; Peng, X.-Z. Autonomous quadrotor navigation with vision based obstacle avoidance and path planning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 102450–102459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.-Z.; Lin, H.-Y.; Dai, J.-M. Path planning and obstacle avoidance for vision guided quadrotor UAV navigation. In Proceedings of the 2016 12th IEEE International Conference on Control and Automation (ICCA) 2016, Kathmandu, Nepal, 1–3 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnebäck, G. Two-frame motion estimation based on polynomial expansion. In Image Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2003; pp. 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, G.; Xiang, X.; Zhu, H.; Yin, D.; Zhu, L. Research on obstacles avoidance technology for UAV based on improved PTAM algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Progress in Informatics and Computing (PIC) 2015, Nanjing, China, 18–20 December 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrafilian, O.; Taghirad, H.D. Autonomous Flight and obstacle avoidance of a quadrotor by Monocular Slam. In Proceedings of the 2016 4th International Conference on Robotics and Mechatronics (ICROM) 2016, Tehran, Iran, 26–28 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potena, C.; Nardi, D.; Pretto, A. Joint Vision-based navigation, control and obstacle avoidance for uavs in Dynamic Environments. In Proceedings of the 2019 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR) 2019, Prague, Czech Republic, 4–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xiao, B.; Zhou, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, J. A robust real-time vision based GPS-denied navigation system of UAV. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER) 2016, Chengdu, China, 19–22 June 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachtsevanos, G.; Kim, W.; Al-Hasan, S.; Rufus, F.; Simon, M.; Shrage, D.; Prasad, J.V.R. Autonomous vehicles: From flight control to mission planning using Fuzzy Logic Techniques. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Digital Signal Processing, Santorini, Greece, 2–4 July 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, D.M. Route planning using pattern classification and search techniques. In Proceedings of the IEEE National Aerospace and Electronics Conference, Dayton, OH, USA, 22–26 May 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczerba, R.J.; Galkowski, P.; Glicktein, I.S.; Ternullo, N. Robust algorithm for real-time route planning. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2000, 36, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stentz, A. Optimal and efficient path planning for partially-known environments. In Proceedings of the 1994 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–13 May 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belge, E.; Altan, A.; Hacıoğlu, R. Metaheuristic Optimization-Based Path Planning and Tracking of Quadcopter for Payload Hold-Release Mission. Electronics 2022, 11, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q. Path planning based Quadtree representation for mobile robot using hybrid-simulated annealing and ant colony optimization algorithm. In Proceedings of the 10th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation 2012, Beijing, China, 6–8 July 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andert, F.; Adolf, F. Online world modeling and path planning for an unmanned helicopter. Auton. Robot. 2009, 27, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tan, G.-z.; Lu, F.-L.; Zhao, J.; Dai, Y.-s. A Molecular Force Field-Based Optimal Deployment Algorithm for UAV Swarm Coverage Maximization in Mobile Wireless Sensor Network. Processes 2020, 8, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.M.J.A.; Lima, G.V.; Morais, A.S.; Oliveira-Lopes, L.C.; Ramos, D.C.; Tofoli, F.L. Modified Artificial Potential Field for the Path Planning of Aircraft Swarms in Three-Dimensional Environments. Sensors 2022, 22, 1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Kang, H.; Sun, X.; Chen, Q.; Wang, D. UAV Path Planning Based on Multi-Stage Constraint Optimization. Drones 2021, 5, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, W. Application of improved Hopfield Neural Network in path planning. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1544, 012154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Chen, H. Unmanned vehicle path planning using a novel Ant Colony algorithm. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fan, S.; Yu, B.; Jia, Y. A Coverage Sampling Path Planning Method Suitable for UAV 3D Space Atmospheric Environment Detection. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Bai, H.; Sun, R.; Sun, R.; Li, C. Three-dimensional path planning based on Dem. 2017 36th Chinese Control Conference (CCC) 2017, Dalian, China, 26–28 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, M.; Mohan, R.; Burgard, W.; Valada, A. Vision-based autonomous UAV navigation and landing for urban search and rescue. Springer Proc. Adv. Robot. 2022, 20, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autoland. Available online: http://autoland.cs.uni-freiburg.de./ (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- Li, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, X.; Wei, S.; Li, P.; Shuang, F. RTSDM: A Real-Time Semantic Dense Mapping System for UAVs. Machines 2022, 10, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, W.; Yang, A.-S.; Chen, H.; Li, B.; Wen, C.-Y. An End-to-End UAV Simulation Platform for Visual SLAM and Navigation. Aerospace 2022, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Ding, B.; Li, Y. Minimum-jerk trajectory planning pertaining to a translational 3-degree-of-freedom parallel manipulator through piecewise quintic polynomials interpolation. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2020, 12, 168781402091366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel-Pearson, B.G.; Marchegiani, L.; Akcay, S.; Abarghouei, A.; Garforth, J.; Breckon, T.P. Online deep reinforcement learning for autonomous UAV navigation and exploration of outdoor environments. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.05684. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Aouf, N.; Whidborne, J.; Song, B. Deep reinforcement learning based local planner for UAV obstacle avoidance using demonstration data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.02521. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.; Sun, H.; Sun, J. Improved Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Algorithm Based Real-Time Trajectory Planning for Parafoil under Complicated Constraints. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theile, M.; Bayerlein, H.; Nai, R.; Gesbert, D.; Caccamo, M. UAV coverage path planning under varying power constraints using deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), IEEE, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24 October–24 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Theile, M.; Bayerlein, H.; Nai, R.; Gesbert, D.; Caccamo, M. UAV path planning using global and local map information with deep reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the UAV Path Planning Using Global and Local Map Information with Deep Reinforcement Learning, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 6–10 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chhikara, P.; Tekchandani, R.; Kumar, N.; Chamola, V.; Guizani, M. DCNN-ga: A deep neural net architecture for navigation of UAV in indoor environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 4448–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menfoukh, K.; Touba, M.M.; Khenfri, F.; Guettal, L. Optimized Convolutional Neural Network Architecture for UAV navigation within Unstructured Trail. In Proceedings of the 2020 1st International Conference on Communications, Control Systems and Signal Processing (CCSSP) 2020, El Oued, Algeria, 16–17 May 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestrini, S.; Lavagna, M. Deep Learning and Artificial Neural Networks for Spacecraft Dynamics, Navigation and Control. Drones 2022, 6, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullu, A.; Endale, B.; Wondosen, A.; Hwang, H.-Y. Machine Learning Approach to Real-Time 3D Path Planning for Autonomous Navigation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).