Abstract

This work simulates the collapse of a spherical void in pure Sn during melting using molecular dynamics (MD). Simulations were performed for two temperatures with a modified embedded atom method (MEAM) potential, which was reported to be in good agreement with respect to melting point and elastic constants. Solutions of the Rayleigh–Plesset (RP) equation are used for comparison under the assumption of macroscopic surface tension and liquid viscosity. Despite a qualitative correlation, longer collapse times were observed in MD simulations, which arose from partial solid structures and the incubation time for melting.

1. Introduction

Healing in metals has recently gained attention as an innovative concept to reduce mechanical damage [1]. A micromechanical model was reported to formulate the liquid-assisted healing of a void collective, which is based on the Rayleigh–Plesset (RP) equation [2]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can potentially provide a better understanding of processes on the nano-scale. Therefore, a modified embedded atom method (MEAM) potential for pure Sn was investigated for agreement with the RP solution [3]. In particular the collapse time due to viscosity and surface tension were evaluated with the MD simulations.

2. Materials and Methods

MD Simulations of a void in pure Sn were performed using an isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble with unit cell size of 30 Å. The ensemble was equilibrated at room temperature for 120 ps and then heated up to 500 K and 600 K for each simulation, respectively. After holding the peak temperature for 100 ps, the system was cooled to room temperature. The Rayleigh–Plesset equation describes the dynamics of a bubble in a viscid fluid. The void pressure and liquid pressue on the left balances with the spherical flow-, inertia-, viscous- and surface tension term on the right in Equation (1).

3. Results and Discussion

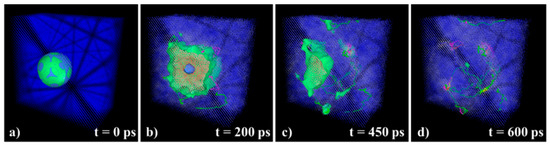

The void evolution during the heating cycle is illustrated in Figure 1. The initially spherical void in Figure 1a is surrounded by a liquid domain in Figure 1b, which is almost fully collapsed. In Figure 1c the recrystallized area is separated from the final liquid domain in green. Figure 1d shows the final structure after 600 ps, the void collapsed and several dislocations were generated.

Figure 1.

Void evolution during molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (a) initial configuration t = 0 ps, (b) void collapse in progress t = 200 ps, (c) completed void collapse t = 450 ps, (d) final stage of solidification t = 600 ps.

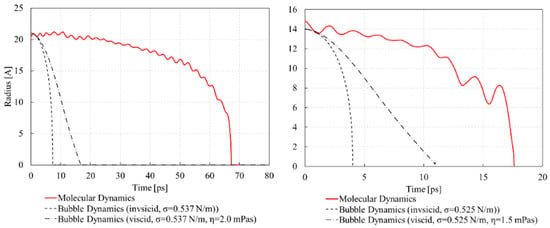

Figure 2 shows the void evolution for both temperatures of the MD simulation (red solid), the inviscid RP solution (dashed) and the viscid RP solution (dot dash). The results reveal a qualitative agreement of the MD simulations with the inviscid solution. Nevertheless, the collapse time for the MD simulations is about four times longer for T = 500 K and 1.5 times longer for T = 600 K, compared to the viscid solution. The simulation at T = 500 K in Figure 1 reveals only partial melting around the void. Therefore, a longer void collapse time was expected due to the stability of the surrounding crystal.

Figure 2.

Void collapse computed with Rayleigh–Plesset (RP) equation and MD simulations (left) T = 500 K (right) T = 600 K.

4. Conclusions

The application of a MEAM potential reported by Ravelo [3] for pure Sn revealed a qualitative agreement with the inviscid solution. A good agreement with the experimental surface tension was reported in the literature for the potential [4]. A four times longer void collapse time was observed in the MD simulations at T = 500 K, which can be associated with partial melting and a higher mechanical stability than that assumed in the RP model. At elevated temperatures the MD simulation showed a 1.5 times longer collapse time, which can be explained by the incubation time required for melting.

Author Contributions

G.S., conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft; E.K. (Elke Kraker) project administration, funding acquisition; D.K., funding acquisition; L.R., review and editing, E.K. (Ernst Kozeschnik), writing—review and editing; W.E., writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support by the Austrian Federal Government (in particular from Federal Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology) represented by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG), within the framework of the “24. Ausschreibung Produktion der Zukunft, nationale Projekte” Programme (project number: 864808 project name: SOLARIS) is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- van Dijk, N.; van der Zwaag, S. Self-healing materials are coming of age. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 1800226, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Siroky, G.; Kraker, E.; Kieslinger, D.; Kozeschnik, E.; Ecker, W. Micromechanics-based damage model for liquid-assisted healing. Int. J. Damage Mech 2020, 29, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelo, R. Equilibrium and Thermodynamic Properties of Grey, White, and Liquid Tin. Phys Rev Lett 1997, 79, 2482–2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourasseau, E.; Filippini, G.; Ghoufi, A.; Malfreyt, P. Calculation of the surface tension of pure tin from atomistic simulations of liquid–vapour systems. Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 2654–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).