Abstract

This study investigates the potential of proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) for application in the transport sector through a numerical modelling approach, evaluating their performance and alignment with the European Union’s climate objectives. The model’s performance was assessed by calculating the percentage error across the operating range, that were found to range from a minimum of 0.045% to a maximum of 2.913% across current densities up to 0.80 A/cm2. The objective is to assess the viability of PEMFCs as a clean alternative to internal combustion engines and to identify the key technical and policy challenges hindering their wider adoption.

1. Introduction

The transport sector accounts for approximately one-quarter of greenhouse gas emissions in the European Union and remains the only sector where emissions are still increasing [1]. In response to the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly in the transport sector, the European Green Deal has set ambitious targets: a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030 and climate neutrality by 2050 [2]. One of the proposed measures includes increased investment in electric and hydrogen refuelling infrastructure [3].

Within this context, fuel cells—particularly proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs), systems that generate electricity through electrochemical reactions, with the overall reaction presented in Equation (1)—have attracted growing attention as a promising technology for zero-emission mobility and are already being deployed across multiple sectors [4]. PEMFCs are characterised by high energy efficiency, low operating temperatures (100 °C), rapid start-up, silent operation, and minimal environmental impact [5]. Additionally, they offer longer lifespans and lower costs compared to other fuel cell technologies [6].

The objective of this paper is to analyse the performance of PEMFCs. To this end, a developed numerical model is compared with a reference model from literature.

2. PEMFC Numerical Model

The PEMFC numerical model incorporates an electrochemical framework based on the work of Al-Dabbagh et al. [7]. The cell voltage is expressed in Equation (2). The model also includes a thermal component that captures the dynamic temperature behaviour of the fuel cell, following the approach of Chatrattanawet et al. in Equation (3) [5]. The parameters used in both sub-models are presented in Table 1.

Here is the Nernst potential, the ohmic loss, the concentration and mass transport loss, and the activation loss. Ct is the thermal capacitance, the total energy, the electric power output, the inlet heat flow rate of the reactant, the outlet heat flow rate of the reactant, and the thermal losses.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the model [5,7].

Table 1.

Parameters used in the model [5,7].

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (kΩ.cm2) | 10−4 | (kJ/K) | 17.9 |

| (V) | 10−5 | (K/W) | 0.115 |

| (cm2/mA) | 10−3 | (K) | 298.15 |

| A (cm2) | 232 | P (atm) | 1 |

| (%) | 100 | Tin,reactant (K) | 348 |

3. Results

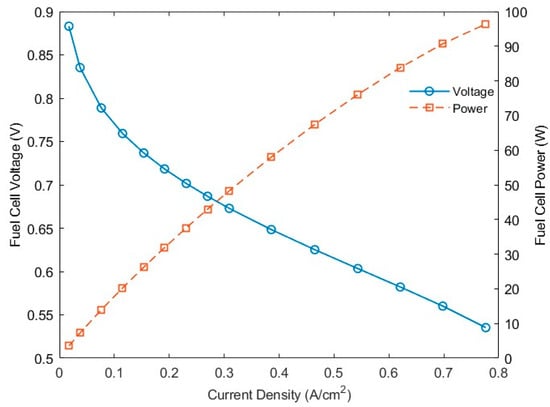

The cell performance at 348 K and 1 atm under steady-state conditions is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Fuel cell performance under steady-state conditions at 348 K and 1 atm.

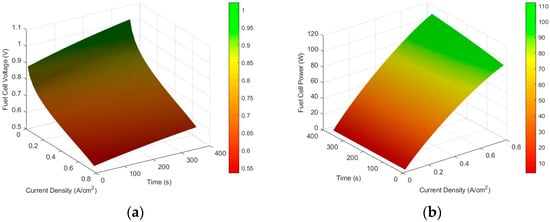

Since Chatrattanawet et al. did not specify the initial cell temperature, it was assumed to be 298.15 K [5]. Based on this assumption and the operating conditions, Figure 2 illustrates the dynamic behaviour of the fuel cell, where (a) shows the cell voltage, and (b) the power output.

Figure 2.

Fuel cell performance in dynamic operation for an initial cell temperature of 298.15 K, with reactant inlet temperatures of 348 K and an operating pressure of 1 atm: (a) voltage; (b) power output.

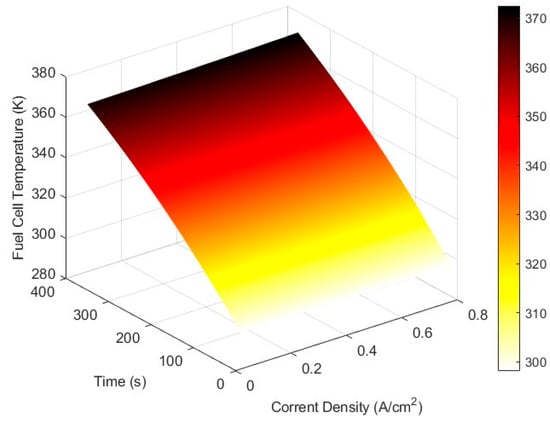

From Figure 3, the cell operates safely for up to 360 s before the temperature exceeds the maximum allowable limit of 373.15 K. This occurs because the thermal model does not include a cooling system.

Figure 3.

Fuel cell operational temperature in dynamic operation for an initial cell temperature of 298.15 K, with reactant inlet temperatures of 348 K and an operating pressure of 1 atm.

To assess the model’s performance over the operating range, the percentual error was calculated using Equation (4) for the performance values at 104 s. The error analysis across current densities up to 0.80 A/cm2 revealed values ranging from 0.045% to 2.913%. The minimum error of 0.045% was observed at a current density of approximately 0.5 A/cm2, while the maximum error of 2.913% occurred at the edges of the current density range examined.

4. Discussion

The numerical model shows strong agreement, with voltage errors ranging from 0.045% to 2.913%.

At 104 s, a single fuel cell operates at a0.566 V and 0.776 A/cm2, yielding a power output of 101.90 W. This output would scale up substantially in a PEMFC stack.

As current density increases, the operating temperature rises, the voltage decreases, and the power output increases. Over time, the continuous increase in temperature leads to a gradual rise in both voltage and power output.

5. Conclusions

Fuel cells provide a promising solution for clean energy production, particularly when hydrogen is from renewable sources, since water and heat are the only by-products. In a fuel cell stack, this technology presents a practical option aligned with the European Union climate and energy objectives.

Temperature management remains a key limitation. To keep the fuel cell bellow the typical maximum operating temperature of 373.15 K, an effective cooling system is required.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D.S.B.; methodology, A.D.S.B.; investigation, M.M., C.A. and A.D.S.B.; resources, A.D.S.B.; data curation, M.M., C.A. and A.D.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and C.A.; writing—review and editing, M.M., C.A. and A.D.S.B.; supervision, A.D.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was developed under the project A-MoVeR—“Mobilizing Agenda for the Development of Products & Systems towards an Intelligent and Green Mobility”, operation No. 02/C05-i01.01/2022.PC646908627-00000069, approved under the terms of call No. 02/C05-i01/2022—Mobilizing Agendas for Business Innovation, financed by European funds provided to Portugal by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (RRP), in the scope of the European Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), framed in the Next Generation UE, for the period from 2021–2026.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- European Parliament CO2 Emissions from Cars: Facts and Figures (Infographics). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20190313STO31218/co2-emissions-from-cars-facts-and-figures-infographics (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- European Parliament. Green Deal: Key to a Climate-Neutral and Sustainable EU. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20200618STO81513/green-deal-key-to-a-climate-neutral-and-sustainable-eu (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- European Parliament. Reducing Car Emissions: New CO2 Targets for Cars and Vans Explained. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20180920STO14027/reducing-car-emissions-new-co2-targets-for-cars-and-vans-explained (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Fuel Cell & Hydrogen Energy Association Fuel Cell Basics. Available online: https://fchea.org/learning-center/fuel-cell-basics/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Chatrattanawet, N.; Hakhen, T.; Kheawhom, S.; Arpornwichanop, A. Control Structure Design and Robust Model Predictive Control for Controlling a Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 934–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.A.; Khalid, M.; Kamal, K.; Abdul Hussain Ratlamwala, T.; Hussain, G.; Alkahtani, M. Modeling and Simulation of a Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell Alongside a Waste Heat Recovery System Based on the Organic Rankine Cycle in MATLAB/SIMULINK Environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dabbagh, A.W.; Lu, L.; Mazza, A. Modelling, Simulation and Control of a Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC) Power System. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 5061–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).