Abstract

Shale gas production dynamics display strong heterogeneity and nonlinearity, posing challenges to conventional analytical methods. This study applies fractal theory to analyze long-term production data from 178 global shale gas fields by calculating Hurst exponent (H) and fractal dimension (D). Results show 60.7% of fields are suitable for fractal analysis, with H values of 0.64–0.92 and D values of 1.0–1.9, indicating significant long-term memory and structural complexity. Cluster analysis reveals two distinct production patterns: stable trend (13.0%) and fluctuating trend (87.0%). Key innovations include: (1) extending fractal theory from static reservoir characterization to dynamic production analysis; (2) establishing a fractal-based production classification system; and (3) defining applicability conditions for fractal analysis in shale gas evaluation. This study demonstrates fractal theory’s effectiveness as a quantitative tool for production dynamics analysis, EUR estimation, and development strategy optimization.

1. Introduction

Shale gas reservoirs are typically characterized by low porosity and ultra-low permeability, exhibiting multi-scale pore structures and complex gas transport mechanisms involving multiple processes. Furthermore, gas desorption phenomena are prevalent within organic nanopores, demonstrating significant heterogeneity and nonlinear behavior. These characteristics pose considerable challenges during development, including complex production decline patterns and difficulties in dynamic performance prediction [1,2]. During production, reservoirs are influenced by stress-sensitive effects and complex gas-water transport behaviors, often leading to rapid initial production growth followed by difficulties in maintaining stable long-term productivity [3]. Conventional analytical methods, which predominantly rely on simplified mathematical assumptions, struggle to effectively characterize such nonlinear dynamics [4,5]. Moreover, they fail to establish quantitative relationships between microscopic reservoir structures and macroscopic production performance, thereby limiting the accuracy of production pattern analysis and output forecasting.

Fractal theory, with its advantages in quantitatively characterizing complex systems, offers a novel perspective for analyzing shale gas production dynamics. This theory employs fractal dimension to quantitatively describe the complexity of reservoir pore-fracture structures, thereby providing an effective tool for establishing intrinsic connections between microscopic structures and macroscopic dynamic responses [6]. In the field of unconventional oil and gas development, fractal theory has achieved remarkable progress in reservoir characterization, seepage mechanism analysis, and productivity prediction. Studies have demonstrated that multifractal theory can systematically quantify the heterogeneity, structural complexity, and spatial distribution patterns of pores and fractures in shale and tight sandstone reservoirs by processing experimental data from scanning electron microscopy, gas adsorption, mercury intrusion capillary pressure, and nuclear magnetic resonance. Integrated with mineral composition and physical properties, it reveals how pores at different scales affect fluid adsorption, desorption, and transport [7,8,9,10]. For coal reservoirs, fractal theory accurately characterizes the fractal features of ultra-micropores and micropores under varying destruction intensities, elucidating the impact of tectonic deformation on pore systems [11,12]. In seepage mechanism research, incorporating fractal dimension into traditional seepage models enables more precise descriptions of gas–water two-phase flow behavior and pressure dynamics in fractured reservoirs, captures the evolution of pore structures in hydrate-bearing sediments, and predicts changes in physical parameters such as permeability and thermal conductivity [13,14,15]. Simultaneously, by establishing correlations between fractal dimension and non-Darcy flow coefficients or seepage factors, the theory provides a quantitative framework for addressing nonlinear seepage problems [16,17]. Additionally, the application of fractal theory to productivity prediction offers new technical support for shale gas development. For multistage fractured horizontal wells in shale gas, quantifying the fractal characteristics of fracture number and length, combined with desorption–diffusion mechanisms and threshold pressure gradients, facilitates the construction of more accurate unsteady seepage productivity models that reflect actual production dynamics [18]. Furthermore, by correlating fractal dimension with mercury injection curves and well-logging response parameters, the theory provides effective classification criteria and productivity prediction models for complex reservoirs such as tight oil and carbonate formations [19]. Certain reservoir evaluation methods based on the fractal characteristics of well logs, by extracting dimensional information reflecting curve complexity and overcoming the limitations of single parameters as well as fluid interference, have significantly enhanced the identification accuracy of pore structures in heterogeneous reservoirs and the resolution of thin layers. These methods provide robust support for the identification of reservoir sweet spots and the optimization of development strategies [9].

Due to limitations in data availability, the selection of characteristic parameters for shale gas fields in this study has certain constraints, which will be addressed in subsequent research. Given the general scarcity of publicly available geological measurement data for global shale gas fields, this study instead systematically analyzes production dynamics based on annual production and reserve data.

Building upon existing research foundations, this paper selects long-term production data (production duration ≥ 8 years) from 178 shale gas fields worldwide. Using R/S analysis and variogram methods, we calculate the Hurst exponent (H) and fractal dimension (D), and combine cluster analysis to identify typical production patterns, systematically establishing quantitative relationships between fractal characteristics and production dynamics. The research framework comprises four main components: data preprocessing, fractal parameter calculation, correlation analysis, and production pattern classification. By introducing fractal theory into the analysis of shale gas production dynamics, this study aims to overcome the limitations of traditional analytical methods and provide new theoretical foundations and methodological support for production forecasting and development strategy optimization.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Fractal Theory

Hurst exponent (H) and fractal dimension (D) together form key dimensions for characterizing system dynamics. The Hurst exponent quantifies long-term memory and trend persistence in time series, while fractal dimension describes complexity and irregularity of fluctuation paths. Temporal dependence and structural complexity perspectives provide a quantitative basis for revealing intrinsic patterns of complex systems.

2.1.1. Hurst Exponent (H)

The Hurst exponent (H) quantifies long-term memory and persistence in fractal time series analysis, revealing statistical dependence between current and historical values—representing the system’s “memory length” [20]. A value of H ≠ 0.5 indicates that the series deviates from an independent random walk, possessing intrinsic dynamic structure where past trends exert persistent or anti-persistent influence on future evolution [21].

Specifically, the values of the Hurst exponent can be categorized into three typical states [22,23]:

- H > 0.5: Signifies positive long-range dependence (persistence), where trends are more likely to continue.

- H < 0.5: Indicates anti-persistence (mean-reversion), with fluctuations tending to revert toward long-term averages.

- H = 0.5: Corresponds to a memoryless random walk with no correlation between observations, consistent with classical random processes.

In practice, the Hurst exponent is commonly estimated using rescaled range analysis (R/S analysis), detrended fluctuation analysis (DFA), or wavelet-based methods. This metric effectively distinguishes stochastic from structural characteristics in systems, thereby providing theoretical support for predictive modeling and risk analysis while enhancing understanding of long-term evolutionary patterns in complex systems.

2.1.2. Fractal Dimension (D)

Fractal dimension (D) serves as a core parameter in fractal theory, quantifying system complexity and irregularity. Unlike the topological dimension for regular geometries, fractal dimension can take non-integer values, characterizing structural features across scales and space-filling capacity [24]. This concept originates from scale invariance and self-similarity, where magnified system components maintain statistical or exact resemblance to the whole [25].

In time series analysis, fractal dimension measures the complexity and roughness of fluctuations. By treating a time series as a dynamic trajectory, its fractal dimension captures the geometry of this path in phase space. Smooth fluctuations with clear trends yield relatively straight trajectories and lower dimensions, whereas volatile fluctuations with noise and frequent reversals produce contorted paths and higher dimensions [26]. Thus, fractal dimension helps distinguish dynamic mechanisms: lower values often indicate deterministic dominance, while higher values suggest stronger stochasticity or chaos.

Multiple methods estimate fractal dimension—such as box-counting, variogram, cover, and multifractal partition function approaches—each suited to different data types and analytical needs (Table 1) [27,28]. Despite methodological variations, all fundamentally assess how information changes across scales to determine system scaling behavior [29]. As an intrinsic geometric property, fractal dimension is widely applied across natural sciences, engineering, and social sciences.

Table 1.

Summary of Primary Calculation Methods for Fractal Dimension.

2.1.3. Relationship Between Hurst Exponent (H) and Fractal Dimension (D)

For monofractal time series with statistical self-similarity, fractal dimension (D) and Hurst exponent (H) maintain the fundamental relationship D ≈ 2 − H [30]. This equivalence connects geometric complexity with dynamic memory, demonstrating consistent fractal properties across spatial structure and temporal evolution. Essentially, a series’ path tortuosity and its trend persistence represent dual expressions of the same underlying property.

A high H value indicates strong persistence, where current trends tend to continue. This stable, directional dynamics produces smoother paths with less spatial occupation, corresponding to lower D values. Conversely, low H reflects anti-persistence or mean-reversion, marked by frequent fluctuations and reversals. Such oscillatory behavior creates complex, winding paths with higher space-filling capacity, thus yielding larger D values [31].

In practical applications, this relationship enables cross-validation, where significant discrepancies between D and H values obtained through different methods may indicate deviations from monofractal assumptions or methodological inconsistencies. More importantly, it bridges static geometric characteristics (represented by D) with dynamic evolutionary behavior (captured by H), providing a holistic perspective for understanding complex systems. When analyzing production decline in oil and gas fields, this connection enhances the explanatory power of fractal theory as a unified framework for characterizing both system complexity and memory effects.

2.2. Methods for Calculating Fractal Characteristics

2.2.1. Calculating H Using R/S Analysis

The R/S analysis (Rescaled Range Analysis) is a non-parametric method used to assess long-range dependence and fractal characteristics in time series. The method involves dividing the time series into multiple contiguous sub-intervals of equal length. For each sub-interval, the range (R) of cumulative deviations from the mean is calculated and then rescaled (divided) by the standard deviation (S) within that sub-interval, yielding a series of R/S ratios [32]. As the time scale (sub-interval length) gradually increases, the R/S values typically exhibit a characteristic power-law growth. To quantitatively describe this relationship, the logarithms of different time scales and their corresponding average R/S values are taken, and a linear fit is performed in this log-log coordinate system [33]. The slope of this fitted line is the Hurst exponent (H). The value of H usually ranges between 0 and 1, and its magnitude reflects the intrinsic properties of the time series [34].

In the analysis of shale gas field production and reserves-to-production ratio sequences, R/S analysis can effectively identify the fractal structure hidden behind complex dynamics, providing an important theoretical basis for judging the stability of gas field production and predicting future trends [35]. This method does not rely on assumptions about the data distribution and possesses strong adaptability, making it particularly suitable for non-stationary, nonlinear energy production data. It is a classic and practical tool in fractal time series analysis [36].

2.2.2. Calculating D Using the Variogram Method

The variogram method is an important geostatistical technique for analyzing the spatial or temporal variability structure of a dataset and is widely used for estimating fractal dimension [37]. This method is based on the following core principle: if a sequence or field exhibits fractal characteristics, its variogram and the lag distance satisfy a power-law relationship. The scaling exponent of this relationship has a clear quantitative connection with the fractal dimension.

In the specific calculation process, the sequence is first differenced according to different time intervals (lag distances) h, and the semi-variance γ(h) at each scale is computed:

where N(h) represents the number of valid data pairs at lag h. As h increases, γ(h) typically follows a systematic progression. To quantify fractal characteristics, natural logarithms of both h and γ(h) are taken, and linear regression is applied in the resulting log-log coordinate system [38]. This transformation generally reveals a significant linear relationship between the variogram and lag distance, whose slope enables the calculation of fractal dimension D

The method requires intrinsically stationary data. Reliable estimation of fractal dimension depends on appropriate lag distance selection, adequate sample size, and objective identification of the linear scaling region. In shale gas production dynamics analysis, the variogram method effectively detects scale-invariance in production and reserves-to-production ratio sequences. Its applicability to non-stationary, non-linear series without requiring specific distributional assumptions makes it particularly valuable for energy time series analysis within the fractal theory framework.

3. Data Processing

This study utilizes the global shale gas field production and reserves database published by WOODMAC in 2024 as the primary data source. To meet the requirements of time series analysis for continuity and statistical significance, shale gas fields with a continuous production record of eight years or more between 2000 and 2024 were first selected from the database, resulting in 178 valid samples. Based on their production duration distribution, these fields are categorized into four groups: 52 fields with a production span of 8–10 years, 79 fields with 11–15 years, 37 fields with 16–20 years, and 8 fields with 21–25 years. For each gas field, key annual metrics—including production year, annual production, and remaining recoverable reserves—were systematically extracted to form a comprehensive dataset for subsequent analysis. This dataset provides the foundational data necessary for identifying production dynamics and conducting fractal assessments.

During the data preprocessing phase, the primary objective is not to perform precise reserve calculations, but to construct a complete and reasonable time-series dataset, so as to utilize reserve dynamics as a key reference for subsequent production analysis. Given the significant number of missing values in the “annual reserves” field of the original dataset, a phased processing method based on production dynamics characteristics was adopted. For each gas field, the complete annual production sequence was analyzed to accurately identify the peak production year, dividing the production history into increasing and declining phases. For fields in the decline phase, the industry-standard hyperbolic decline curve model was applied to fit late-stage production data and estimate EUR. The reserves sequence was then reconstructed using the principle: “Reserves (t) = EUR − Cumulative production up to year t”. For fields still in the production growth phase, the most recent year’s known remaining recoverable reserves served as the benchmark, with the complete reserves sequence built through retrospective calculation: “Reserves (t) = Latest known reserves + Cumulative production from year t to present”.

This phased approach fully accounts for the dynamic characteristics of different development stages: the hyperbolic decline model accurately captures the nonlinear production patterns during decline, while the retrospective calculation ensures logical consistency in the reserves sequence during growth phases, offering greater physical rationality compared to simple linear interpolation methods. Furthermore, Monte Carlo simulation was introduced to assess estimation uncertainty, generating 80% confidence intervals for each reserves value through 2000 random samplings of key parameters in the hyperbolic decline model. Analysis results show over 90% of declining fields demonstrate high reliability, ensuring the robustness of subsequent analytical conclusions.

In the data quality control phase, the 3σ criterion was employed to identify and handle outliers in the production sequence, ensuring data rationality. As all production data in this study consist of continuous, complete sequences with uniform units, normalization was deemed unnecessary.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Applicability Analysis of Fractal Theory

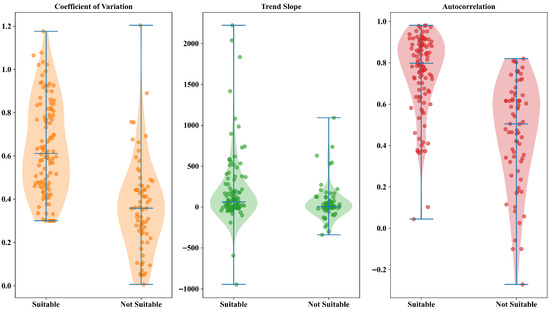

The applicability of fractal theory to shale gas field production dynamics was assessed using three key statistical parameters: the coefficient of variation (CV), trend slope, and autocorrelation. The CV measures the relative volatility of production sequences, with higher values indicating greater fluctuation intensity. The trend slope reflects the overall directional tendency of production over time—positive for growth and negative for decline. Autocorrelation quantifies the persistence of production behavior, where higher values signify stronger long-term memory. These parameters collectively determine whether a production series exhibits the scale-invariance and long-range dependence required for fractal modeling.

The results show 60.7% of the shale gas fields are suitable for fractal analysis. These fields share the common characteristics of having production sequence lengths of no less than 10 years and CV values greater than 0.3, indicating that their production data possess sufficient temporal continuity and volatility to meet the fundamental requirements for fractal modeling. The remaining 39.3% of fields, characterized by either shorter data histories or overly stable production, were analyzed using traditional statistical methods due to the difficulty in effectively extracting fractal features.

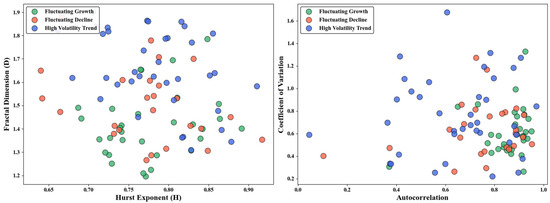

The production dynamics of shale gas fields suitable for fractal analysis exhibit significant long-range dependence and state persistence. In terms of volatility characteristics, the CV values are generally high, with 67.6% of fields exceeding 0.5. This reflects a similar fluctuation structure in the production sequences across different time scales, satisfying the basic requirement of scale invariance for fractal analysis. Regarding trend characteristics, most fields display stable trend slopes, indicating a clear and consistent evolutionary direction. In terms of autocorrelation, the fields demonstrate significant autocorrelation, with 73.1% having autocorrelation values greater than 0.7, suggesting that historical production exerts a persistent influence on and offers strong predictability for future performance (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Comparison of Production Dynamics in Shale Gas Fields with and without Fractal Applicability (Each scatter point denotes a specific characteristic value for a gas field, while the shaded zone delineates the range exhibiting the central tendency of the data distribution).

The gas fields unsuitable for fractal analysis exhibit dynamic features inconsistent with a fractal structure. Regarding volatility, their CV values are widely distributed, encompassing sequences with extremely gentle fluctuations as well as those with drastic production changes, thereby undermining the self-similarity basis under scale transformation. In terms of trend characteristics, the trend slopes mostly approach zero, lacking a sustained and clear evolutionary direction. Autocorrelation is generally weak, with 61.4% of fields having values below 0.6, indicating short-lived memory effects within the sequences. Collectively, these characteristics limit the applicability of fractal analysis for this group of fields (Figure 1).

The analysis results indicate that the time span of the production sequence, production volatility characteristics, and the intrinsic persistence of the sequence jointly constitute key indicators for determining the suitability of fractal analysis for shale gas fields. Specifically, fields suitable for fractal analysis demonstrate good data structure regularity and dynamic consistency. Their production sequences possess sufficient complexity and long-range dependence to meet the fundamental data requirements of fractal theory. In contrast, for fields unsuitable for fractal analysis—due to overly short production sequences, excessively stable production changes, or a lack of sustained correlation within the sequences—the data characteristics fail to satisfy the basic assumptions of fractal theory. Consequently, these fields require investigation using traditional statistical methods or other analytical techniques.

4.2. Distribution Patterns of Fractal Characteristics

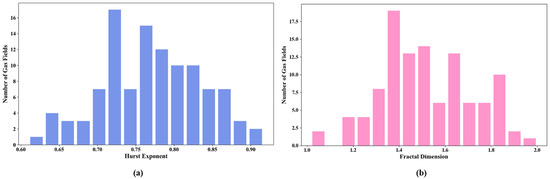

Among the shale gas fields suitable for fractal analysis, the mean Hurst exponent (H) is 0.78 (range: 0.64–0.92), and the mean fractal dimension (D) is 1.5 (range: 1.0–1.9) (Table 2). The calculation of H and D values is directly based on the original production sequence. These values collectively indicate that their production behavior exhibits strong persistence and moderate structural complexity. Regarding statistical characteristics, the standard deviation of H is 0.07, suggesting a relatively concentrated distribution of this parameter. This further reveals the significant long-term memory present in the production sequences of these shale gas fields and verifies the applicability of fractal theory for characterizing the inherent patterns in their production dynamics. The standard deviation of D is 0.25, with values primarily distributed in the 1.3–1.7 range, reflecting a moderate to high degree of structural complexity and dynamic irregularity in the production systems of these shale gas fields (Figure 2).

Table 2.

Statistical Summary of Fractal Parameters.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Fractal Parameters. (a) Hurst Exponent Distribution; (b) Fractal Dimension Distribution.

When the fractal dimension is high, the structural complexity of the sequence increases significantly, and the production system becomes more sensitive to both external development conditions and internal geological factors. This relationship indicates that the fractal dimension can serve as an effective auxiliary indicator for assessing the characteristics of production trend variations in gas fields.

4.3. Production Pattern Classification

Based on the fractal analysis data from 108 shale gas fields and integrated with the K-means clustering method, the production patterns were systematically categorized into two types. This classification scheme incorporates multidimensional information, including the long-term memory, fluctuation characteristics, and trend dynamics of the production sequences, aiming to provide deeper insights into production behavior and establish a theoretical basis for formulating differentiated development strategies.

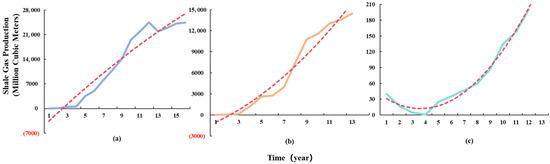

The first production pattern is the Stable Trend Type, characterized by high H values, low CV values, and strong autocorrelation. Based on the gas field’s lifecycle stage, it can be subdivided into:

- Stable Growth Type: Comprising 5 shale gas fields, which account for 4.6% of the total. In terms of temporal structure, the H values for this category range between 0.64 and 0.86, indicating strong persistence in the production sequences. The D values primarily fall within a moderate range of 1.0 to 1.2, indicating a discernible regularity in the production dynamics over time. Regarding production volatility, the CV values are all below 0.5, and the autocorrelation coefficients all exceed 0.95, demonstrating a high correlation between production at adjacent time points and further reinforcing the stability and continuity of their trends. From a growth perspective, the trend slopes for these fields are all positive and relatively high, indicating rapid production increase. Moreover, none of these fields reached their production peak during the observation period, demonstrating strong and sustained growth momentum. This pattern is representative of a typical “high-growth, medium-volatility” development type (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Production Trend Curve of Stable-Growth Shale Gas Fields (The red dashed line denotes the production trend line). (a) Gas Field No.1; (b) Gas Field No.2; (c) Gas Field No.3.

Figure 3. Production Trend Curve of Stable-Growth Shale Gas Fields (The red dashed line denotes the production trend line). (a) Gas Field No.1; (b) Gas Field No.2; (c) Gas Field No.3.

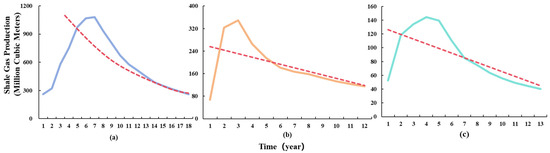

- Stable Decline Type: Comprising 9 shale gas fields, which account for 8.3% of the total. In terms of temporal structure, the H values for this category primarily range from 0.69 to 0.87, while the D values fall between 1.3 and 1.6. This reflects that although the production sequences are structurally complex, they possess strong long-term memory and trend persistence. Regarding production volatility, the CV values for all fields in this category are below 0.6, with most concentrated in the 0.4–0.5 range. Simultaneously, the autocorrelation coefficients all exceed 0.75, indicating that a relatively stable output level is maintained even during the decline phase, and a strong positive correlation exists between production at adjacent time points, which helps ensure the coherence of the declining trend. From the perspective of trend characteristics, the production trend slopes for these fields are consistently negative, indicating an overall moderate decline rate (Figure 4). Furthermore, all fields exhibited only a single production peak during the observation period, further confirming that their production status has entered a systematic and stable decline phase, characteristic of the late development stage.

Figure 4.

Production Decline Curve of Stable-Decline Shale Gas Fields (The red dashed line denotes the production trend line). (a) Gas Field No.4; (b) Gas Field No.5; (c) Gas Field No.6.

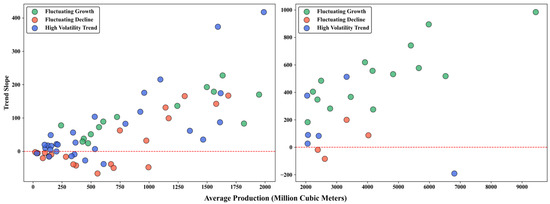

The second production pattern is classified as the Fluctuating Trend Type, comprising 94 shale gas fields and accounting for the predominant majority of 87.0%. In terms of temporal structure, this category exhibits strong persistence coupled with high complexity: 88.4% of the fields have H values between 0.7 and 0.9, indicating significant long-term memory in their production sequences. The D values display a wide distribution range (1.2–1.9), reflecting structurally complex and irregular production fluctuations across time scales (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Distribution Characteristics of Shale Gas Fields by Production Variability.

Regarding production volatility, the CV values are generally high, with 70.5% of fields exceeding 0.5, signifying substantial year-to-year production variations and relatively poor development stability. Concurrently, autocorrelation analysis reveals that 50% of the fields have autocorrelation coefficients greater than 0.8, with some approaching 1.0, further confirming a strong correlation between production at adjacent time points and suggesting a certain potential for trend continuity (Figure 5). Additionally, most fields are characterized by high absolute values of the trend slope alongside high average production rates (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Trend Slope vs. Mean Production Rate Across Variability Types (Extreme Points Excluded; The red dashed line indicates the zero-mark line).

During production, the interplay of engineering practices, operational parameters, geological conditions, and development factors collectively shapes the fractal characteristics of production sequences. Macroscopically, tectonic setting, reservoir heterogeneity, and in situ stress fields influence the complexity and propagation patterns of the initial fracture network, which governs the strength of long-term memory (H value). Microscopically, total organic carbon (TOC), thermal maturity, and mineral brittleness control the spatiotemporal evolution of stimulated reservoir volume and flow capacity, thereby affecting local irregularity and structural complexity in production fluctuations (D value). The coupling of these multi-scale factors results in production dynamics that simultaneously exhibit trend continuity and fluctuation complexity, underscoring the relevance of fractal theory in effectively characterizing the production behavior of high-volatility gas fields.

Based on the overall trend direction and different lifecycle stages, the Fluctuating Trend Type can be further subdivided into three subcategories:

- Fluctuating Growth Type (34.0%): Exhibits an overall upward trajectory during the growth phase, despite the presence of short-term fluctuations.

- Fluctuating Decline Type (26.6%): Displays a general downward trend during the production depletion phase, accompanied by significant volatility.

- High-Volatility Complex Type (39.4%): Lacks a distinct directional trend but is marked by particularly pronounced fluctuation amplitudes, indicating very high uncertainty.

(1) Fluctuating Growth Type Shale Gas Fields

Shale gas fields of the Fluctuating Growth Type exhibit the typical characteristics of “high-growth, strong-volatility.” These fields generally possess high production growth slopes, indicating robust production enhancement capacity. Concurrently, their average production remains at a high level, reaching a maximum of 49,455.7 million cubic meters, reflecting a solid production potential. Regarding fluctuation characteristics, these fields demonstrate significant production instability. The Haynesville Shelby Trough Shale gas field (ALT TX, BP) shows CV values as high as 0.99, while the Marcellus WV Dry Gas Shale gas field (APP WV, EQT Corporation) also reaches 0.86, indicating substantial volatility during production. This volatility is further manifested in the frequent occurrence of production peaks. For instance, the Marcellus Susquehanna Core Shale gas field (APP PA, Coterra Energy) experienced five periodic peaks within the observation period, and the Marcellus WV Rich Gas Shale gas field (APP WV, EQT Corporation) exhibited four, demonstrating a typical “step-like” growth pattern.

In terms of temporal structure, these fields show strong trend persistence. The Marcellus Susquehanna Core Shale gas field (APP PA, Expand Energy) has an H value of 0.89 and an autocorrelation coefficient of 0.92; the Appalachian Basin Other Shale gas field (APP KY) has an H value of 0.84 and an autocorrelation coefficient of 0.91. This suggests that, despite short-term fluctuations, the long-term growth trend is relatively stable. Analysis reveals that some fields exhibit a coexistence of high growth and high volatility. For example, the Marcellus Southwest Rich Gas Shale gas field (APP PA, CNX Resources) has a CV of 0.82 alongside a growth rate of 619.59; the Utica Lean Gas Core Hz Shale gas field (APP OH, Gulfport) maintains a high growth rate of 896.05 while having a CV of 0.64. This “high-growth, high-volatility” characteristic combination fully reveals the complexity arising from the interaction of multiple factors—such as geological conditions, engineering measures, and development strategies—during shale gas development.

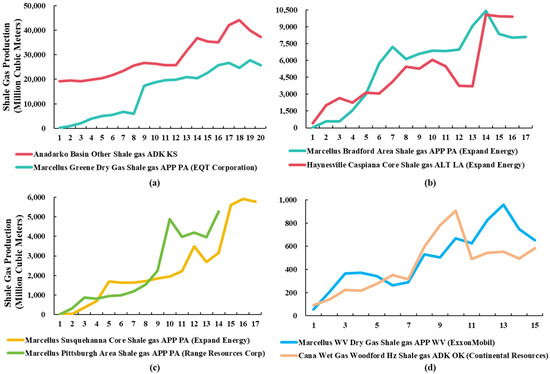

Among shale gas fields with fluctuating growth characteristics, fields of different productivity levels exhibit distinct production dynamics. Ultra-high-productivity fields show an overall upward production trend. Some of these fields experienced steady growth initially, followed by significant acceleration later, while others exhibited slow initial growth, rapid mid-term increase, and then continued steady rise, maintaining high overall production levels (Figure 7a). High-productivity fields generally grew rapidly in the early stages. Some fields showed fluctuations after reaching a certain production level but maintained an overall upward trajectory; others rose rapidly in the later stages before slightly declining, yet remained within the high-production range (Figure 7b). Medium-productivity fields initially grew relatively slowly, then gradually increased their growth rate, showing significant growth particularly in the later stages, with sustained production increases (Figure 7c). Low-productivity fields exhibited a fluctuating rise overall, but the growth rate was relatively slow, and production levels consistently remained low. Data analysis indicates that both ultra-high- and high-productivity shale gas fields possess substantial remaining recoverable reserves, classifying them as large gas fields (Figure 7d). For instance, the Anadarko Basin Other Shale gas field (ADK KS) achieved a production of 37,641.9 million cubic meters in 2024, with remaining recoverable reserves of 617.56 billion cubic meters. The Marcellus Bradford Area Shale gas field (APP PA, Expand Energy) had a production of 8107.5 million cubic meters in the same year, with remaining recoverable reserves of 561.20 billion cubic meters. Medium-productivity shale gas fields are classified as medium-sized fields; for example, the Marcellus Susquehanna Core Shale gas field (APP PA, Expand Energy) had a production of 5786.0 million cubic meters in 2024, with remaining recoverable reserves of 63.81 billion cubic meters. In contrast, low-productivity shale gas fields are small fields, such as the Marcellus WV Dry Gas Shale gas field (APP WV, ExxonMobil), which had a production of 651.9 million cubic meters and remaining recoverable reserves of 6.99 billion cubic meters in 2024.

Figure 7.

Typical Fluctuating-Growth Shale Gas Fields by Production Level (Time: year). (a) Ultra High-yield Shale Gas Field; (b) High-yield Shale Gas Field; (c) Middle Class Shale Gas Field; (d) Low-yield Shale Gas Field.

Furthermore, the classification results reveal that approximately 70% of these shale gas fields are concentrated in the Marcellus play. This non-random distribution can be reasonably explained by the coupling effect of geological endowment and development dynamics. Geologically, the core area of the Appalachian Basin possesses ideal characteristics for forming fluctuating-growth patterns: high TOC values and thermal maturity ensure sufficient gas supply, supporting a sustained growth trend consistent with the long-term memory indicated by the H value; high brittle mineral content facilitates the formation of complex fracture networks, leading to high spatiotemporal heterogeneity in production response, directly manifested as the fluctuation complexity characterized by the fractal dimension. From a development perspective, compared to early-development areas that have entered a decline phase, the Marcellus play is still in a large-scale production enhancement stage. Continuous interventions such as new well commissioning, infill drilling, and re-fracturing repeatedly disrupt natural decline trends, creating a “step-like” production profile that further amplifies sequence volatility and growth trends. However, limited by the scope of publicly available data in the utilized database, corresponding geological data could not be obtained. Consequently, this study has not established a quantitative mapping between geological parameters and fractal characteristics, which will be an important direction for future research.

(2) Fluctuating Decline Type Shale Gas Fields

Shale gas fields of the Fluctuating Decline Type exhibit the typical characteristics of “systematic decline with relative stability.” These fields generally display distinct negative trend slopes. For instance, the Barnett Tier Two Shale gas field (FTW TX, ExxonMobil) and the Woodford Hz Shale gas field (AKM OK, ExxonMobil) show slopes of −42.43 and −49.76, respectively, indicating a sustained and stable declining trend. Simultaneously, some fields maintain a relatively high average production level even during the decline phase. The Marcellus Bradford Area Shale gas field (APP PA, Equinor), for example, has an average production of 3321.55 million cubic meters, suggesting retained development potential.

Regarding fluctuation characteristics, different fields exhibit variability: the EOG BC field has a CV value of 0.82, while the Barnett Tier Two Shale gas field (FTW TX, ConocoPhillips) has a CV value as high as 1.07, indicating significant volatility persists during the decline process in some fields. In terms of temporal structure, most fields demonstrate high trend persistence. The Barnett Shale gas field (FTW TX, Eni) has an H value of 0.86, and the Cana Dry Gas Woodford Hz Shale gas field (ADK OK, Continental Resources) has an autocorrelation coefficient of 0.93. This indicates that, despite being in a decline phase, their production sequences maintain strong long-term memory and trend continuity.

Further analysis reveals that some fields experience multiple periodic production peaks during their decline. For example, the Marcellus Bradford Area Shale gas field (APP PA, Enerplus) and the Marcellus Bradford Area Shale gas field (APP PA, Equinor) exhibited three and four phase peaks, respectively. This suggests that effective development adjustments can lead to periodic production recoveries even during the overall decline phase. This development mode, characterized as “orderly decline with controllable fluctuations,” provides significant insights for the late-stage development management of shale gas fields. By accurately understanding decline patterns and implementing timely interventions, the economic production life of a field can be effectively extended, enabling the efficient utilization of remaining recoverable reserves.

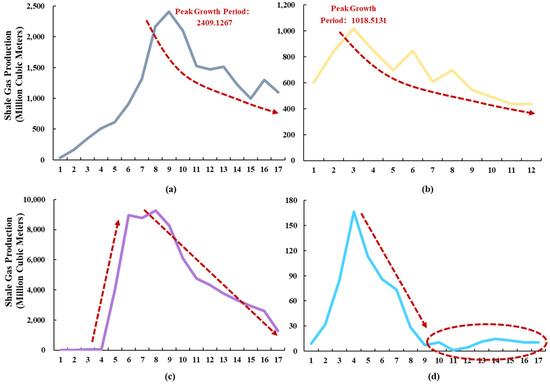

During the development of shale gas fields, those in different decline stages exhibit distinct characteristics. Fields in the mid-decline stage typically experience rapid production growth initially, reach a peak, and then enter a decline phase, showing an overall pattern of rising followed by falling. For instance, the production of the SCOOP Core Woodford Hz Shale gas field (ADK OK, Marathon Oil) declined from 2409.1 million cubic meters to 1125.0 million cubic meters, with its remaining recoverable reserves also decreasing from 17.18 billion cubic meters to 11.83 billion cubic meters (Figure 8a). Fields following a Continuous Fluctuating Decline pattern transition to a state of continuous fluctuation and overall decline after a short period of growth and peak production. The Barnett Shale gas field (FTW TX, ConocoPhillips), for example, saw its production drop from 1018.5 million cubic meters to 436.7 million cubic meters, with remaining recoverable reserves falling from 8.09 billion cubic meters to 5.45 billion cubic meters (Figure 8b). Fields characterized by a Rapid Decline enter a phase of fast decline shortly after production rapidly climbs to a high level, exhibiting a high average decline rate. The Barnett Shale gas field (FTW TX, ExxonMobil), which is in the late decline stage, has an average decline rate of 21.86%, and its remaining recoverable reserves also decreased substantially during the decline period (Figure 8c). For fields that completed their decline stage within a short period, production increased significantly to a peak before declining rapidly, with the declining trend stabilizing later. The CNRL Horn River BC field, for example, has completed its main decline process but still maintained certain production fluctuations at the very end of its development life (Figure 8d).

Figure 8.

Typical Fluctuating-Decline Shale Gas Fields by Decline Phase (Time: Year; The red dashed line denotes the production trend, while the red circles delineate the fluctuations observed in the terminal production phase). (a) Decreasing Mid-term; (b) Continuous fluctuation decreasing; (c) Rapidly decreasing; (d) Late stage of decline.

(3) High-Volatility Complex Type Shale Gas Fields

High-volatility complex type shale gas fields exhibit significant complex dynamic characteristics across multiple statistical indicators, which coexist with notable trend continuity. The H values primarily range from 0.66 to 0.91, with a mean of 0.78, indicating strong long-term memory and persistence in their production sequences at the macroscopic level. The D values are distributed across a relatively wide interval of 1.3 to 1.9, with a mean of 1.7, reflecting a complex dynamic structure and highly irregular fluctuation patterns at the microscopic level, thereby revealing typical multi-scale fractal characteristics in the system’s behavior.

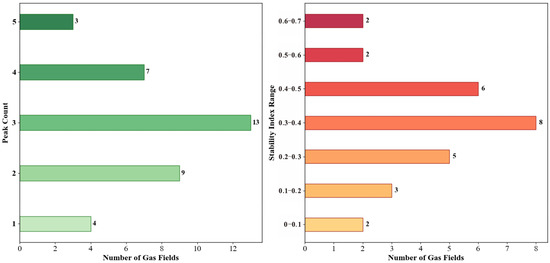

The production sequences exhibit generally high CV values, with most exceeding 0.6. This underscores substantial volatility and high dispersion of production across different time periods, thereby statistically corroborating the classification as a high-volatility trend type. In terms of morphological evolution, the production profiles of most fields display complex dynamic patterns, including multiple production peaks and phases of rapid increase or decrease. Specifically, the most common occurrence is 13 fields exhibiting three periodic production peaks. The stability index is predominantly low, with the highest concentration (8 fields) in the 0.3–0.4 range, and another 5 fields falling within 0–0.2. This overall distribution indicates a system marked by significant disorder and periodic variability (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Distribution of Peak Count versus Stability Coefficient in High-Volatility Trend Shale Gas Fields.

Notable examples include the Marcellus WV Dry Gas Shale gas field (APP WV, Antero Resources). This field transitioned from a growth phase to a decline stage and is currently in its late decline period. Nearly its entire production history has been accompanied by persistent fluctuations, with its remaining recoverable reserves also showing a continuous pattern of rises and declines. Similarly, the Lindero Atravesado field is characterized by dramatic production surges and drops, with its reserves likewise undergoing substantial increases and decreases. Collectively, these statistical indicators and dynamic morphological features confirm that high-volatility shale gas fields possess the dual attributes of trend continuity and pronounced dynamic complexity throughout their development lifecycle.

The classification results indicate that approximately 35% of this type of shale gas field are concentrated in the Haynesville play. Geologically, the unique deep burial, high-temperature, and high-pressure environment of the Haynesville play shapes its inherent “high initial production–rapid decline” characteristic: abnormally high formation pressure leads to a sharp initial production surge, while strong stress-sensitive effects cause rapid and unstable production decline. This geological endowment directly underlies the high volatility of the production sequences. Simultaneously, the strong correlation between development activities in this play and natural gas prices results in a “start-stop” drilling and completion pattern, introducing periodic anthropogenic fluctuations into the production sequences. Furthermore, ongoing large-scale fracturing technological interventions superimpose new fluctuation cycles onto the natural decline curve, further amplifying dynamic complexity. However, due to limitations in the scope of publicly available data in the database used, systematic collection of key geological and engineering parameters was not possible. Consequently, this study was unable to establish a quantitative relationship model between formation pressure, rock mechanical parameters, and fractal characteristics.

4.4. Constraining Effect of Production Dynamics Classification on EUR Estimation Uncertainty

To further clarify the practical value of production dynamics classification for estimating EUR in shale gas fields, this study introduces a Dynamic Uncertainty Coefficient (DUC) based on key fractal parameters to quantify the uncertainty inherent in production forecasting for different types of gas fields. The development of this coefficient is grounded in the following theoretical and empirical rationale: D reflects the structural complexity and irregularity of production sequences, H characterizes long-term memory and trend persistence, and the autocorrelation coefficient indicates the dependency between production values at adjacent time points. Accordingly, the DUC is defined as follows:

The numerator, D × (1 − Autocorrelation), integrates structural complexity and short-term unpredictability. Higher D and lower autocorrelation result in more tortuous production paths and less predictable short-term fluctuations, thereby increasing system uncertainty. The denominator, divided by H, accounts for the moderating effect of trend persistence. A higher H indicates stronger long-term memory and more stable trends, partially offsetting the uncertainty introduced by structural complexity. Thus, DUC comprehensively captures the intrinsic uncertainty structure of production sequences across three dimensions: dynamic complexity, short-term noise, and long-term memory, providing clear physical and statistical significance.

A strong correlation exists between DUC values and EUR estimation errors, further validating the rationality of the classification proposed earlier:

- Stable Trend Type: Typically exhibit low D, high H, and strong autocorrelation, resulting in DUC < 0.3. Their straightforward dynamics and well-defined trends lead to EUR prediction errors generally below 10%.

- Fluctuating Growth and Decline Type: Increased structural complexity and reduced autocorrelation, with DUC values ranging 0.3–0.6 and 0.4–0.9, respectively, corresponding to elevated prediction uncertainty.

- High-Volatility Complex Type: Characterized by high D, low autocorrelation, and low H, exhibit DUC > 1.0, reaching up to 2.5. These systems demonstrate high uncertainty and chaotic behavior, with EUR prediction errors potentially exceeding 25%, necessitating probabilistic assessment methods for risk quantification.

This coefficient not only provides a unified uncertainty classification standard for gas fields with different fractal characteristics but also reinforces the objectivity and practicality of the proposed classification—the categories are not subjective but correspond to distinct uncertainty structures and predictive behaviors. By leveraging DUC to adjust prediction confidence intervals and parameter perturbation ranges, the reliability and engineering applicability of EUR estimations for shale gas fields are enhanced.

5. Conclusions

Fractal theory reveals the long-term memory and structural complexity inherent in production dynamics, offering a novel perspective for constructing more reliable Estimated Ultimate Recovery (EUR) prediction models and optimizing development strategies. It serves as an effective quantitative indicator for assessing the life-cycle stage and ultimate recovery factor of gas fields.

- (1)

- Shale gas production sequences commonly exhibit significant fractal characteristics. Among the 108 gas fields suitable for fractal analysis, the mean H values is 0.78 and the mean D values is 1.5. This indicates that shale gas production sequences possess distinct long-term memory and moderate to high structural complexity, which are difficult to fully characterize using traditional linear models.

- (2)

- Based on fractal characteristics, shale gas fields can be classified into stable-trend and fluctuating-trend types. For the predominant fluctuating-trend category (87.0%), three distinct subclasses were identified according to their fractal features and dynamic behaviors: fluctuating-growth (34.0%), characterized by high growth rates coupled with strong volatility; fluctuating-decline (26.6%), maintaining pronounced decline trends amid fluctuations; and high-fluctuation complex (39.4%), exhibiting both trend persistence and dynamic complexity. This refined classification reveals substantial heterogeneity within fluctuating gas fields, demonstrating how differences in fractal structure directly correspond to distinct production evolution pathways, thereby providing a theoretical foundation for formulating differentiated development strategies.

- (3)

- The fractal-based production pattern classification establishes a quantitative framework for development strategy formulation and EUR uncertainty assessment. The proposed DUC directly correlates classification with EUR prediction accuracy: stable-type fields (DUC < 0.3) show errors below 10%, while high-fluctuation complex fields (DUC > 1.0) may exceed 25% error. This achievement creates a direct link between fractal classification and development risk evaluation, offering valuable references for and probabilistic EUR assessment methods across different field types.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and B.L.; methodology, X.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, X.Z.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and B.L.; visualization, X.Z. and L.Z. (Lingfeng Zhao); supervision, B.L. and L.Z. (Liang Zhao); funding acquisition, B.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52174019), the National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2025ZD1406407), (2025ZD1405902), and (2025ZD1407501).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Liang Zhao was employed by the company PetroChina Research Institute of Petroleum Exploration & Development. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Clarkson, C.R.; Nobakht, M.; Kaviani, D.; Ertekin, T. Production analysis of tight-gas and shale-gas reservoirs using the dynamic-slippage concept. SPE J. 2012, 17, 230–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.M.; Hughes, R.G. Production data analysis of shale gas reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 21 September 2008. SPE-116688-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Yang, Z.; Xie, N.; Ye, C.; Xiong, J.; Zhu, K.; Cheng, J. Dynamic analysis method research and application of shale gas horizontal well. Chem. Technol. Fuels Oils 2021, 57, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Liu, X.; Hu, Z.; Duan, X.; Chang, J. A Semianalytical Production Prediction Model and Dynamics Performance Analysis for Shale Gas Wells. Geofluids 2021, 2021, 9920122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sima, Q. Dynamic analysis and optimization strategies for shale oil production. Geogr. Res. Bull. 2024, 3, 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dhar, D. Fractals. Bull. Mater. Sci. 1984, 6, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.D. Application of the Multi-fractal Theory in Describing Unconventional Reservoir Characteristics. Liaoning Chem. Ind. 2016, 45, 777–778+781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Guan, P.; Zhang, J.; Liang, X.; Ding, X.; You, Y. A Review of the Progress on Fractal Theory to Characterize the Pore Structure of Unconventional Oil and Gas Reservoirs. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin. 2023, 59, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.Q. Research on Evaluation Methods for Complex Reservoir Pore Structure Based on Fractal Theory. In Proceedings of the Second China Petroleum Geophysics Academic Conference (Volume II), Wuhan, China, 24 April 2024; PetroChina Huabei Oilfield Company Exploration and Development Research Institute: Renqiu, China, 2024; pp. 140–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Lü, M.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Jiang, F.; Yang, Z.; Chen, W.; Huo, L.; Wang, R.; et al. Fractal-based Permeability Prediction Model for Tight Sandstone. Acta Sedimentol. Sin. 2023, 41, 1847–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuo, Z.S.; Zhang, S.S.; Luo, J.H.; Wang, X.W. Application of fractal theory in gas-water seepage modeling of fractured reservoir. China Sci. 2023, 18, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, B.; Liao, C.; Luo, Y.; Ji, K. Fractal theory-based permeability model of fracture networks in coals. Coal Geol. Explor. 2023, 51, 107–115. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Du, Z.; Ren, Q. A mathematical model for productivity calculation of shale-gas multilateral horizontal wells based on fractal theory. Oil Drill. Prod. Technol. 2017, 39, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, Y. Application of Fractal Theory to Natural Gas Hydrate Researches. Mar. Geol. Front. 2020, 36, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Zhang, F.; Cui, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.G.; Shen, Z.Y. Pressure dynamic analysis of shale gas reservoirs considering stress sensitivity and complex migration. Lithol. Reserv. 2019, 31, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K. Study on Productivity of Carbonate Matrix Acidizing Based on Fractal Theory. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Petroleum University, Chengdu, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Zhang, Y.; You, H.; Li, W.; Ma, Y. Study on non-Darcy seepage parameters based on fractal theory. J. Shandong Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2021, 35, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Research on Productivity Prediction Method of Network Fractured Horizontal Well Based on Fractal Theory. Master’s Thesis, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.H. Application of Fractal Theory in the Classification of Tight Oil Reservoirs: A Case Study of Lacustrine Carbonate Rocks in Leijia, Liaohe. Neijiang Sci. Technol. 2023, 44, 22–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, H.E. Long-term storage capacity of reservoirs. Trans. Am. Soc. Civ. Eng. 1951, 116, 770–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gospodinova, E. Fractal time series analysis by using entropy and hurst exponent. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies, Ruse, Bulgarien, 17–18 June 2022; pp. 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mandelbrot, B.B.; Wallis, J.R. Robustness of the rescaled range R/S in the measurement of noncyclic long run statistical dependence. Water Resour. Res. 1969, 5, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liao, J.X. The Analysis and Application of Hurst Exponent. China Soft Sci. 2005, 3, 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, C. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1984, 147, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. Development Research Overview of Fractal Theory. Guide Sci. Educ. 2013, 17, 184–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q. Simulation of Fractal Geometric Dimension and Coefficient for Images. China Sci. Technol. Inf. 2016, 20, 70–71. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Sun, L.; Li, H.; Yuan, J. Research on multi-fractal dimension and its improved algorithm. J. Xi’an Univ. Technol. 2014, 30, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.F.; Wu, Y.Q. Research on Two Fractal Box Dimension. J. Jilin Jianzhu Univ. 2013, 30, 84–85+111. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Q.K.; Liang, G.Q. The Concept and Measurement Methods of Fractal Dimension. Econ. Trade Pract. 2015, 16, 240. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, M.; Shen, B.; Meng, H.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X. Fractal Characteristics and R/S Analysis of Precipitation and Runoff of Baoji City. J. Eng. Heilongjiang Univ. 2009, 36, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gneiting, T.; Schlather, M. Stochastic models that separate fractal dimension and the Hurst effect. SIAM Rev. 2004, 46, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleymanov, A.A.; Abbasov, A.A.; Ismaylov, A.J. Fractal analysis of time series in oil and gas production. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2009, 41, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K.; Zheng, W. R/S Method, Modified R/S Method and Their Comparative Study. Commer. Times 2012, 8, 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kale, M.D.; Butar, F.B. Fractal Analysis of Time Series and Distribution Properties of Hurst Exponent. Ph.D. Thesis, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, AL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Taqqu, M.S.; Teverovsky, V.; Willinger, W. Estimators for long-range dependence: An empirical study. Fractals 1995, 3, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.Z.; Qin, Y.H.; Liu, L.; Huang, Y.J. Analysis of Water Resources Variation of Yellow River and Main River in the Loess Plateau with R/S Method. J. Desert Res. 2010, 30, 467–470. [Google Scholar]

- Suleymanov, A.A.; Abbasov, A.A.; Ismaylov, A.J. Application of fractal analysis of time series in oil and gas production. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2009, 27, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, P.A. Fractal dimensions of landscapes and other environmental data. Nature 1981, 294, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).