Fractional Optical Solitons in Metamaterial-Based Couplers with Strong Dispersion and Parabolic Nonlinearity

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Governing Model

- The linear-temporal evolution is governed by the coefficients and .

- Dispersion effects are represented by the parameters and for , corresponding to chromatic dispersion (CD), third-order (3OD), fourth-order (4OD), fifth-order (5OD), and sixth-order dispersion (6OD), respectively. The dispersion properties of the considered medium play a crucial role in shaping the soliton dynamics. These parameters enable modeling of both normal and anomalous dispersion regimes, which determine whether bright or dark solitons can be sustained. The inclusion of higher-order dispersion makes the model suitable for analyzing highly dispersive and nonlinear photonic structures. Physically, the results are most applicable to single-mode optical fibers operating near the zero-dispersion wavelength, photonic crystal fibers with controllable dispersion through microstructural design, and highly nonlinear fibers that enhance the balance between dispersion and nonlinearity. Such engineered fiber systems and metamaterial-based couplers are capable of supporting the fractional-order soliton families reported in this study.

- The terms with coefficients and (where ) model the parabolic law nonlinearity.

- The constants , , and (for ) are associated with the properties of the optical metamaterial.

- The coupling between the two components is quantified by the parameters ().

- Furthermore, higher-order nonlinear dispersion is accounted for by the coefficients and (), while the self-steepening (SS) effects are characterized by ().

1.2. Main Novelty and Contribution

2. Some Mathematical Preliminaries

2.1. Core Principles of Conformable Fractional Derivatives

- (1)

- Linearity:

- (2)

- Power rule:

- (3)

- Constant rule:

- (4)

- Product rule:

- (5)

- Quotient rule:

- (6)

- Classical derivative relation: If ψ is differentiable, then

2.2. Mathematical Framework of the MEDAM

- Step 1: Traveling wave reduction

- Step 2: Solution structure assumption

- Step 3: Determining M

- Step 4: Parameter identification

3. Development of Novel Analytical Solutions via Conformable Fractional Derivatives

3.1. Mathematical Reduction via Traveling Wave Transformation

3.2. Extraction of Exact Solutions

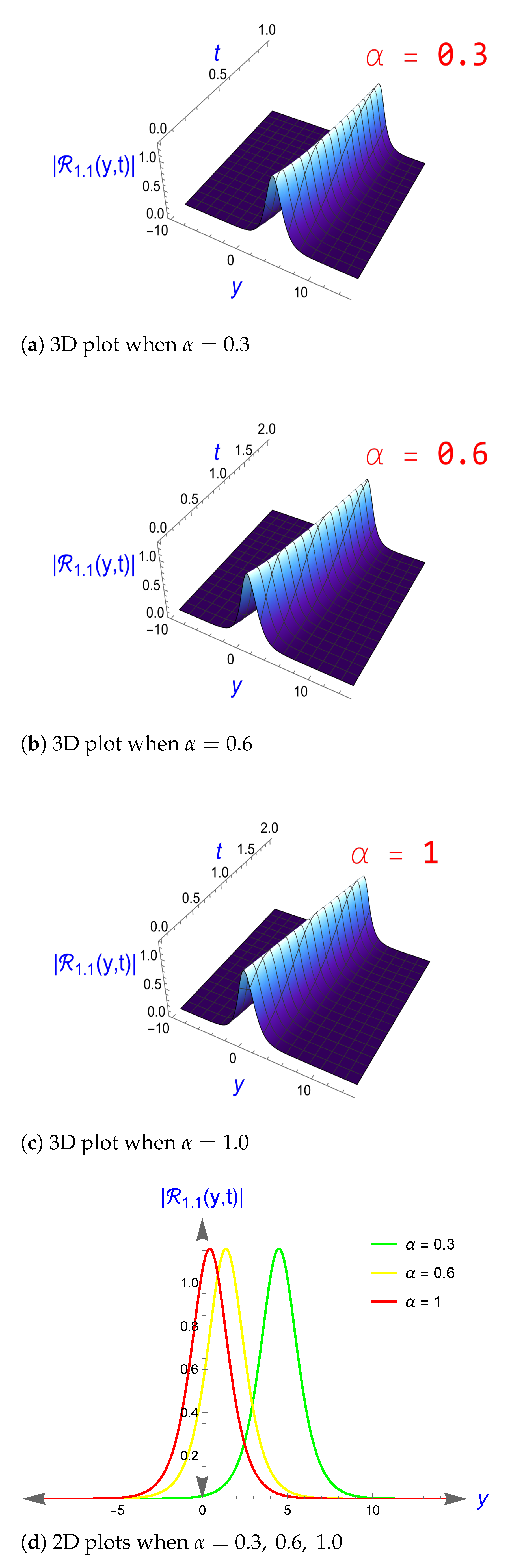

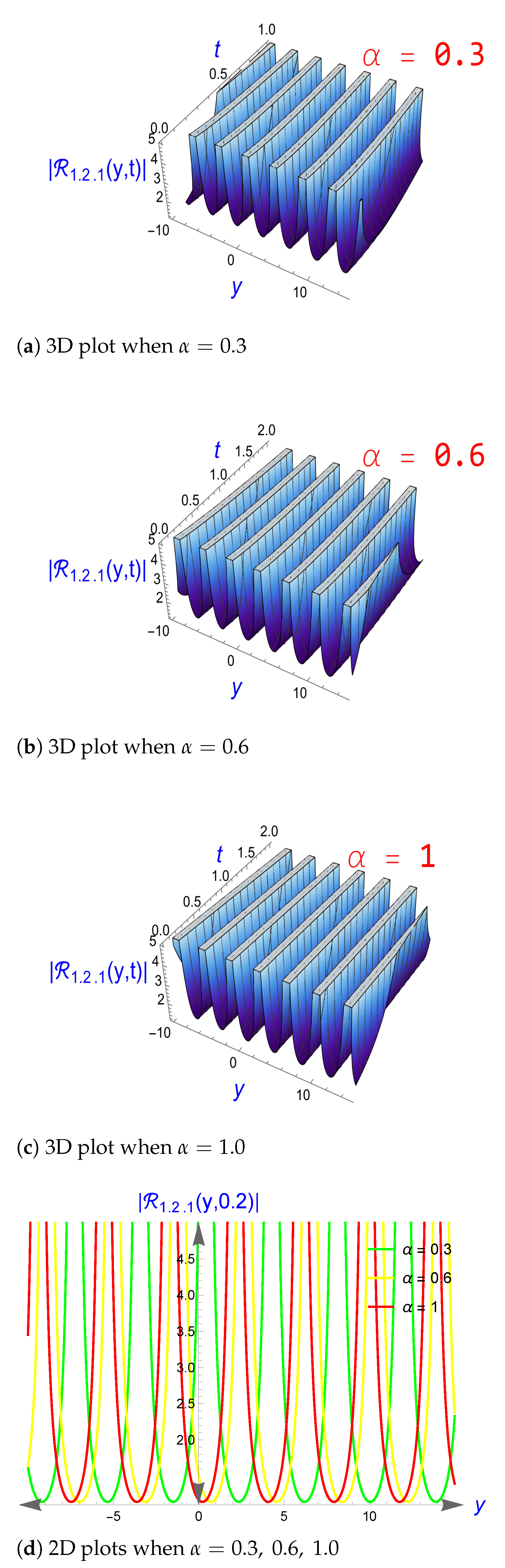

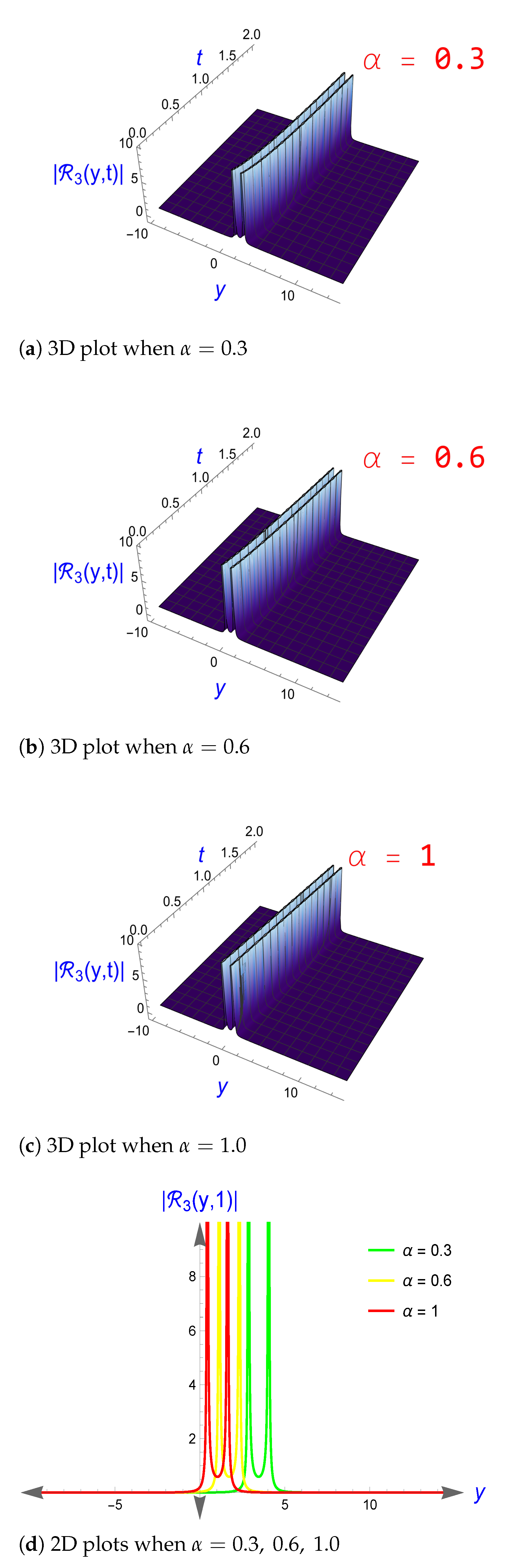

4. Graphical Representation for Some Retrieved Solutions

5. Discussion About Results

5.1. The Influence of the CFD on the Retrieved Solutions

5.2. Comparison with Literature

5.3. Physical Interpretation and Applicability

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grillakis, M.G. On nonlinear Schrödinger equations: Nonlinear Schrödinger equations. Commun. Partial. Differ. Equ. 2000, 25, 1827–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, K.W. Logarithmic nonlinear Schrödinger equation and irrotational, compressible flows: An exact solution. Phys. Rev. E—Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2011, 84, 016308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Seadawy, A.; Arshad, M. Applications of extended simple equation method on unstable nonlinear Schrödinger equations. Optik 2017, 140, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, S.; Onorato, M.; Proment, D. Bose-Einstein condensation and Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless transition in the two-dimensional nonlinear Schrödinger model. Phys. Rev. A 2014, 90, 013624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, M.A.; Owyed, S.; Abdel-Aty, A.; Raffah, B.M.; Abdel-Khalek, S. Optical soliton solutions for a space-time fractional perturbed nonlinear Schrödinger equation arising in quantum physics. Results Phys. 2020, 16, 102895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezazadeh, H.; Ullah, N.; Akinyemi, L.; Shah, A.; Mirhosseini-Alizamin, S.M.; Chu, Y.M.; Ahmad, H. Optical soliton solutions of the generalized non-autonomous nonlinear Schrödinger equations by the new Kudryashov’s method. Results Phys. 2021, 24, 104179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W.W.; Cesarano, C.; Al-Askar, F.M. Solutions to the (4+ 1)-dimensional time-fractional Fokas equation with M-truncated derivative. Mathematics 2022, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, N.; Ullah, M.S.; Manafian, J.; Mahmoud, K.H.; Alsubaie, A.S.A.; Ahmed, H.M.; Ahmed, K.K.; Al Khatib, S. Bifurcation analysis, chaotic behaviors, and explicit solutions for a fractional two-mode Nizhnik-Novikov-Veselov equation in mathematical physics. AIMS Math. 2025, 10, 4558–4578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.Q.; Lu, H.P.; Zhang, D.S.; Wang, L.C.; Ma, Z.Y.; Xiao, J.J. Inverse design of a light nanorouter for a spatially multiplexed optical filter. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 6232–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malomed, B.A. Soliton models: Traditional and novel, one-and multidimensional. Low Temp. Phys. 2022, 48, 856–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.H.; Ahmed, H.M.; Rabie, W.B.; Ahmed, K.K.; Hashemi, M.S.; Bayram, M. Multiple soliton solutions and other travelling wave solutions to new structured (2+1)-dimensional integro-partial differential equation using efficient technique. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 105270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, D. Localized optical structures: An overview of recent theoretical and experimental developments. Proc. Rom. Acad. A 2015, 16, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shihua, C.; Grelu, P.; Mihalache, D.; Baronio, F. Families of rational soliton solutions of the Kadomtsev–Petviashvili I equation. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2015, 68, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, G.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Zheng, L. Solitons in one-dimensional non-Hermitian moiré photonic lattice. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magarotto, M.; De Carlo, P.; Schenato, L.; Santagiustina, M.; Galtarossa, A.; Pavarin, D.; Capobianco, A.D. Feasibility study on a plasma based reflective surface for SatCom systems. Acta Astronaut. 2023, 208, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimistov, A.I. Solitons in nonlinear optics. Quantum Electron. 2010, 40, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Qin, H.; Bai, G.; Chen, C.; Shi, P.; Du, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, W.; et al. Launching by cavitation. Science 2025, 389, 935–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, D.S.; Si, Z.Z.; Qiu, W.X.; Dai, C.Q. Optical soliton formation and dynamic characteristics in photonic moiré lattices. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Optical solitons in optical metamaterials with anti-cubic nonlinearity. Optik 2022, 251, 168329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, K.K.; Ahmed, H.; Badra, N.M.; Mirzazadeh, M.; Rabie, W.B.; Eslami, M. Diverse exact solutions to Davey–Stewartson model using modified extended mapping method. Nonlinear Anal. Model. Control 2024, 29, 983–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ma, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, D. Dynamic behavior of optical soliton interactions in optical communication systems. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2022, 39, 114202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexan, W.; Youssef, M.; Hussein, H.H.; Ahmed, K.K.; Hosny, K.M.; Fathy, A.; Mansour, M.B.M. A new multiple image encryption algorithm using hyperchaotic systems, SVD, and modified RC5. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, N.A. Method for finding highly dispersive optical solitons of nonlinear differential equations. Optik 2020, 206, 163550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Ekici, M.; Sonmezoglu, A.; Belic, M.R. Highly dispersive optical solitons with quadratic-cubic law by F-expansion. Optik 2019, 182, 930–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.J.M.; Abu-AlShaeer, M.J. Highly dispersive optical solitons with cubic law and cubic-quintic-septic law nonlinearities by two methods. Al-Rafidain J. Eng. Sci. 2023, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, M.A. The extended F-expansion method and its application for a class of nonlinear evolution equations. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 31, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.; Chakraverty, S. Riccati–Bernoulli sub-ode method-based exact solution of new coupled Konno–Oono equation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2024, 38, 2440028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, M.; Manafian, J.; Zamanpour, I. Soliton wave solutions in optical metamaterials with anti-cubic law of nonlinearity by ITEM. Optik 2018, 164, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.N. An analytical method for finding exact solutions of a nonlinear partial differential equation arising in electrical engineering. Open J. Math. Sci. 2023, 7, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naher, H. New approach of (G′/G)-expansion method and new approach of generalized (G′/G)-expansion method for ZKBBM equation. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 2015, 23, 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.; Aldosary, S.F.; Batool, S.; Hussain, I.; Hussain, N. Exploring fractional-order new coupled Korteweg-de Vries system via improved Adomian decomposition method. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Alshehry, A.S.; Shafee, A.; Shah, R. Families of propagating soliton solutions for (3+1)-fractional Wazwaz-BenjaminBona-Mahony equation through a novel modification of modified extended direct algebraic method. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 045230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alngar, M.E.; Alamri, A.M.; AlQahtani, S.A.; Shohib, R.M.; Pathak, P. Exploring optical soliton solutions in highly dispersive couplers with parabolic law nonlinear refractive index using the extended auxiliary equation method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2024, 38, 2450350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.S.; Ali, M.Z.; Roshid, H.O. Bifurcation, chaos, and stability analysis to the second fractional WBBM model. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalil, R.; Al Horani, M.; Yousef, A.; Sababheh, M. A new definition of fractional derivative. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2014, 264, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, A.A. The modified extended direct algebraic method for solving nonlinear partial differential equations. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2008, 6, 136–144. [Google Scholar]

- Rabie, W.B.; Ahmed, K.K.; Badra, N.M.; Ahmed, H.M.; Mirzazadeh, M.; Eslami, M. New solitons and other exact wave solutions for coupled system of perturbed highly dispersive CGLE in birefringent fibers with polynomial nonlinearity law. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; El-Owaidy, H.M.; Ahmed, H.M.; El-Deeb, A.A.; Samir, I. Optical solitons and complexitons for generalized Schrödinger–Hirota model by the modified extended direct algebraic method. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2023, 55, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, K.K.; Ahmed, H.M.; Radwan, T.; Ramadan, M.E.; Alkhatib, S.; Ali, M.H. Fractional Optical Solitons in Metamaterial-Based Couplers with Strong Dispersion and Parabolic Nonlinearity. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110720

Ahmed KK, Ahmed HM, Radwan T, Ramadan ME, Alkhatib S, Ali MH. Fractional Optical Solitons in Metamaterial-Based Couplers with Strong Dispersion and Parabolic Nonlinearity. Fractal and Fractional. 2025; 9(11):720. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110720

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Karim K., Hamdy M. Ahmed, Taha Radwan, M. Elsaid Ramadan, Soliman Alkhatib, and Mohammed H. Ali. 2025. "Fractional Optical Solitons in Metamaterial-Based Couplers with Strong Dispersion and Parabolic Nonlinearity" Fractal and Fractional 9, no. 11: 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110720

APA StyleAhmed, K. K., Ahmed, H. M., Radwan, T., Ramadan, M. E., Alkhatib, S., & Ali, M. H. (2025). Fractional Optical Solitons in Metamaterial-Based Couplers with Strong Dispersion and Parabolic Nonlinearity. Fractal and Fractional, 9(11), 720. https://doi.org/10.3390/fractalfract9110720