Abstract

Background: Glioblastoma (GBM) is among the most aggressive and morphologically heterogeneous brain tumors. Beyond static imaging biomarkers, its structural organization can be viewed as a nonlinear dynamical system. Characterizing morphodynamic attractors within such a system may reveal latent stability patterns of morphological change and potential indicators of morphodynamic organization. Methods: We analyzed 494 subjects from the multi-institutional BraTS 2020 dataset using a fully automated computational pipeline. Each multimodal MRI volume was encoded into a 16-dimensional latent space using a 3D convolutional autoencoder. Synthetic morphological trajectories, generated through bidirectional growth–shrinkage transformations of tumor masks, enabled training of a contraction-regularized Neural Ordinary Differential Equation (Neural ODE) to model continuous-time latent morphodynamics. Morphological complexity was quantified using fractal dimension (DF), and local dynamical stability was measured via a Lyapunov-like exponent (λ). Robustness analyses assessed the stability of DF–λ regimes under multi-scale perturbations, synthetic-order reversal (directionality; sign-aware comparison) and stochastic noise, including cross-generator generalization against a time-shuffled negative control. Results: The DF–λ morphodynamic phase map revealed three characteristic regimes: (1) stable morphodynamics (λ < 0), associated with compact, smoother boundaries; (2) metastable dynamics (λ ≈ 0), reflecting weakly stable or transitional behavior; and (3) unstable or chaotic dynamics (λ > 0), associated with divergent latent trajectories. Latent-space flow fields exhibited contraction-induced attractor-like basins and smoothly diverging directions. Kernel-density estimation of DF–λ distributions revealed a prominent population cluster within the metastable regime, characterized by moderate-to-high geometric irregularity (DF ≈ 1.85–2.00) and near-neutral dynamical stability (λ ≈ −0.02 to +0.01). Exploratory clinical overlays showed that fractal dimension exhibited a modest negative association with survival, whereas λ did not correlate with clinical outcome, suggesting that the two descriptors capture complementary and clinically distinct aspects of tumor morphology. Conclusions: Glioblastoma morphology can be represented as a continuous dynamical process within a learned latent manifold. Combining Neural ODE–based dynamics, fractal morphometry, and Lyapunov stability provides a principled framework for dynamic radiomics, offering interpretable morphodynamic descriptors that bridge fractal geometry, nonlinear dynamics, and deep learning. Because BraTS is cross-sectional and the synthetic step index does not represent biological time, any clinical interpretation is hypothesis-generating; validation in longitudinal and covariate-rich cohorts is required before prognostic or treatment-monitoring use. The resulting DF–λ morphodynamic map provides a hypothesis-generating morphodynamic representation that should be evaluated in covariate-rich and longitudinal cohorts before any prognostic or treatment-monitoring use.

1. Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most malignant primary brain tumor in adults, characterized by rapid proliferation, diffuse infiltration, pronounced morphological heterogeneity, and resistance to standard therapy [1,2,3]. Despite advances in multimodal treatment—including maximal safe resection, chemoradiation, and targeted therapies—the median survival remains approximately 14–16 months after diagnosis [4,5]. This poor prognosis is driven in part by the tumor’s complex morphodynamic behavior: its ability to reorganize, deform, and adapt its structure through nonlinear biological processes.

Conventional neuroimaging-based analyses focus predominantly on static radiomic features, quantifying intensity statistics, texture, shape, or volumetric descriptors extracted from single time points [6,7,8,9]. While such features have provided robust biomarkers for prognosis and treatment monitoring, they do not capture the continuous evolution of tumor morphology. GBM growth, edema, necrosis, and infiltration arise from nonlinear interactions across spatial and temporal scales, suggesting that tumor morphology may be more appropriately viewed as a nonlinear dynamical system [10,11,12].

In dynamical systems theory, attractors represent stable or metastable states toward which trajectories tend to evolve [13]. From a morphodynamic perspective, the evolution of GBM may be conceptualized as a trajectory in a high-dimensional morphological state space, where attractor-like configurations correspond to relatively persistent shapes or organizational patterns. Identifying such latent attractor regions could provide insights into tumor progression, invasiveness, and potential early indicators of treatment resistance.

Recent developments in deep learning have enabled the formulation of biological processes in continuous latent spaces. Neural Ordinary Differential Equations (Neural ODEs), introduced by Chen et al. [14], model hidden representations as solutions to parameterized differential equations, enabling the learning of smooth, time-continuous trajectories from discrete samples. When applied to medical imaging, Neural ODEs provide a principled means to simulate continuous morphological deformations even in the absence of longitudinal scans [15,16,17]. In this work, ‘stability’ refers to the behavior of the learned latent ODE flow (e.g., attractor-like tendencies induced by regularization and the finite-time sensitivity quantified by λ); related stability analyses exist for other neural-network formulations (e.g., Clifford- and quaternion-valued networks), but these address different settings from the real-valued, delay-free Neural ODE considered here [18,19].

Similarly, 3D convolutional autoencoders have emerged as effective tools for learning compact latent embeddings of anatomical structures [20,21,22]. By projecting high-dimensional MRI data onto low-dimensional manifolds, these models preserve geometric and topological information while offering a tractable space in which shape evolution can be studied. Within such latent manifolds, morphological changes can be interpreted as latent trajectories, which Neural ODEs can model to infer underlying morphodynamic laws.

In this study, we propose a novel integrated framework combining 3D convolutional autoencoding, synthetic shape evolution, and Neural ODE–based latent dynamics to investigate glioblastoma morphodynamics. Using 494 preoperative MRI volumes from the BraTS 2020 dataset [23], we trained a 16-dimensional autoencoder to capture intrinsic tumor variability. Synthetic morphological trajectories were generated through controlled bidirectional growth–shrinkage operations on tumor masks [24], enabling the estimation of continuous latent flow fields in the absence of true longitudinal imaging.

Novelty and contribution of the present work. The novelty of this study does not lie in the isolated use of fractal dimension or Lyapunov exponents—both of which are established concepts—but in their joint integration within a continuous latent dynamical framework learned directly from medical imaging data. Unlike prior studies that treat fractal metrics as static radiomic descriptors extracted from a single MRI exam, we model glioblastoma morphology as a trajectory evolving on a learned latent manifold. Within this framework, fractal dimension (DF) characterizes geometric boundary complexity, while a finite-time Lyapunov exponent (λ) quantifies the local dynamical stability of inferred morphodynamic flows. The resulting DF–λ morphodynamic phase space enables identification of stable, metastable, and unstable morphological regimes that cannot be obtained from static shape analysis alone.

To quantify structural and dynamical properties of latent morphodynamics, we computed two complementary measures:

- Lyapunov exponent (λ)—capturing local stability or sensitivity to perturbations;

- Fractal dimension (DF)—quantifying geometric and structural complexity of the tumor boundary [25,26,27].

The joint distribution of these measures defines a morphodynamic phase space in which stable, metastable, and unstable regimes emerge naturally. Visualization of trajectories and kernel-density maps in this DF–λ space reveals population-level patterns, potential attractor-like regions, and morphodynamic signatures associated with aggressive or stable tumor configurations.

Although the primary aim of this work is methodological, we also include exploratory clinical overlays to contextualize the morphodynamic descriptors. These analyses show that fractal dimension exhibits a modest negative association with overall survival, whereas λ does not correlate with clinical outcome, suggesting that boundary complexity and latent dynamical stability capture complementary and clinically distinct aspects of GBM morphology.

Relation to prior fractal analyses of glioblastoma. Previous work has applied fractal dimension and lacunarity to glioblastoma margins, necrotic cores, and infiltrative interfaces as static descriptors derived from a single MRI exam, showing associations with survival, molecular markers, and tumor aggressiveness. These studies treat fractal metrics as fixed radiomic features and do not model the dynamical behavior of morphology. In contrast, the present framework embeds morphology into a continuous latent dynamical system, combining fractal dimension with a finite-time Lyapunov exponent to form a DF–λ morphodynamic map. This joint structural–dynamical representation extends prior static fractal work by characterizing not only how complex a GBM boundary is, but also how stable or unstable its latent morphodynamics are under small perturbations.

Through this framework, we aim to unify nonlinear dynamics, fractal morphometry, and deep latent modeling into a coherent methodology for dynamic radiomics, offering new insight into the continuous evolution of glioblastoma morphology and its potential implications for clinical outcomes.

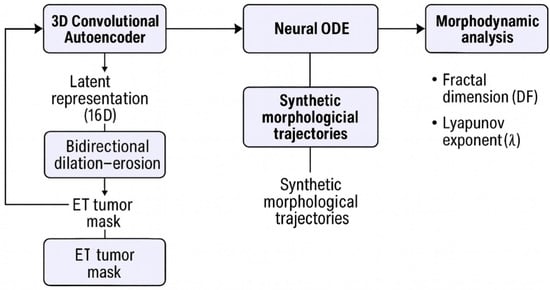

A schematic overview of the full pipeline is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Overview of the morphodynamic modeling pipeline. Multimodal MRI volumes from the BraTS 2020 dataset are encoded into a 16-dimensional latent space using a 3D convolutional autoencoder. Bidirectional dilation–erosion operations applied to the enhancing tumor (ET) mask generate synthetic morphological sequences, which are re-encoded into synthetic latent trajectories. A Neural ODE is trained to learn continuous latent dynamics over these trajectories. Fractal dimension (DF) and a Lyapunov-like exponent (λ) are then computed from the simulated latent flow, forming the DF–λ morphodynamic phase space and KDE-based morphodynamic density map used in subsequent analyses.

Key Contributions of This Work

- Introduces a dynamic radiomics framework that models glioblastoma morphology as a continuous nonlinear dynamical system using Neural ODEs.

- Learns latent morphodynamic flows without longitudinal imaging through biologically motivated synthetic shape trajectories.

- Unifies fractal geometry and dynamical systems theory by jointly analyzing fractal dimension (DF) and a Lyapunov-like exponent (λ).

- Reveals stable, metastable, and unstable morphodynamic regimes emerging directly from latent-space dynamics.

- Identifies a characteristic GBM morphodynamic phenotype, with most tumors clustering in a metastable region of the DF–λ phase space.

- Demonstrates robustness of morphodynamic regime classification across multi-scale perturbations, direction reversal, and segmentation noise.

- Provides a reproducible, fully automated pipeline applicable to multi-center MRI datasets.

In the remainder of this manuscript, Section 2 details the full methodological pipeline, including data preprocessing, 3D autoencoder training, synthetic morphological trajectory generation, and the construction of the Neural ODE–based latent dynamics. This section also introduces the three robustness and stability evaluations—multi-scale dilation–erosion analysis, direction-reversal testing, and noise-perturbation analysis—as well as the computation of fractal dimension and Lyapunov-like stability exponents. Section 3 presents the experimental results, covering the structure of the learned latent space, the behavior of latent morphodynamic trajectories, the empirical DF–λ phase map, and the KDE-based morphodynamic density map representation. Results of the robustness tests are also reported, demonstrating the stability of the inferred dynamical regimes across scales, directionality, and perturbations. Section 4 provides an in-depth discussion of the implications of these findings, including a dedicated subsection on the fractal and dynamical interpretation of tumor morphology. This section interprets the observed dynamical regimes in the context of nonlinear systems theory, fractal boundary evolution, tumor microenvironment heterogeneity, and potential biological–clinical relevance. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main contributions of this work and outlines future directions, including the need for longitudinal MRI validation, biological interpretation of latent-space attractors, and the integration of morphodynamic descriptors into predictive or prognostic modeling.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

All experiments were conducted using the BraTS 2020 (Brain Tumor Segmentation Challenge) dataset, comprising 494 subjects with preoperative multimodal MRI. Each subject includes four co-registered 3D MRI sequences with isotropic 1 mm3 resolution:

- T1-weighted (T1)

- Post-contrast T1-weighted (T1ce)

- T2-weighted (T2)

- T2-FLAIR

Expert annotations delineate three tumor subregions:

- (1)

- necrotic/non-enhancing core (NCR),

- (2)

- peritumoral edema (ED),

- (3)

- enhancing tumor (ET).

In this work, the enhancing tumor (ET) mask served as the morphological structure for all geometric and fractal analyses.

BraTS 2020 images are distributed in a harmonized form (e.g., skull-stripped, co-registered, and resampled to a common resolution), so the present validation reflects performance under standardized preprocessing rather than raw clinical MRI variability.

Because the study is unsupervised, all 494 subjects were used collectively for training and evaluation. No longitudinal imaging is available in BraTS; therefore, synthetic morphological trajectories were generated to approximate temporal evolution.

Why ET was selected.

We deliberately use only the enhancing tumor (ET) mask, as it provides the most stable, biologically meaningful, and reproducible boundary for morphological analysis. The whole-tumor (WT) region contains large volumes of FLAIR hyperintensity dominated by vasogenic edema and nonspecific infiltration, which produce irregular contours unrelated to intrinsic tumor geometry. Including these regions would inflate fractal dimension, distort boundary-derived morphodynamics, and introduce artifacts unrelated to tumor biology or dynamical stability. ET avoids these confounds and is therefore standard in fractal-based glioma morphology studies.

2.2. Preprocessing

Preprocessing followed the standard BraTS workflow:

- N4ITK bias field correction to remove low-frequency intensity inhomogeneity.

- Z-score normalization within the intracranial region (per-channel).

- Cropping and resampling to a uniform 128 × 128 × 128 voxel grid.

- Extraction of ET regions, stored alongside MRI volumes.

Each sample was saved in an .npz file containing:

- 4 MRI channels (T1, T1ce, T2, FLAIR),

- the enhancing tumor mask,

- metadata (subject ID, age, resection type, survival),

- original train/validation split.

These files served as input for both autoencoder training and synthetic trajectory generation.

2.3. 3D Autoencoder for Morphological Encoding

Tumor morphology was compressed using a 3D convolutional autoencoder (AE) implemented in PyTorch2.1.0+cu121.

Architecture

Encoder:

- 3 convolutional blocks (3 × 3 × 3 kernels),

- Channels: 32 → 64 → 128,

- Each block followed by ReLU and 2 × 2 × 2 max pooling,

- Final fully connected layer compressing features to a 16-dimensional latent vector.

Decoder:

- Mirror of the encoder using transposed convolutions for volumetric reconstruction.

Training

- Loss: Mean squared error (MSE) reconstruction loss.

- Optimizer: Adam (lr = 10−4, batch size = 2).

- Training epochs: 20 full passes over all 494 volumes.

- Hardware: NVIDIA L4 GPU.

The resulting latent representation preserved global tumor geometry, border irregularity, and internal intensity structure, forming a smooth morphological manifold for downstream dynamical modeling.

We initially trained the autoencoder for 20 epochs, which was sufficient for convergence of the reconstruction loss. A separate 50-epoch run produced very similar reconstruction error and latent-space statistics; therefore, all analyses reported in this work are based on the 20-epoch model.

Training–validation considerations.

Because the autoencoder is used solely as an unsupervised morphometric encoder rather than a predictive model, all 494 subjects were used for training. The goal is to learn a smooth and complete morphological manifold spanning the full variability of the cohort, not to evaluate out-of-sample reconstruction performance. For this reason, no dedicated validation split was required; reconstruction loss was monitored throughout training to ensure stable convergence and to avoid overfitting to noise. This approach is standard in unsupervised representation learning when the downstream task (here, latent morphodynamic analysis) does not depend on reconstruction generalization properties.

Autoencoder Morphometric Fidelity and DF Preservation

To quantify the extent to which autoencoder compression may distort fine-scale boundary geometry and bias fractal morphometry, we performed a reconstruction-based fidelity analysis focused on the enhancing-tumor (ET) mask. Because the autoencoder reconstructs volumes on its native decoder grid (49 × 49 × 49), all fidelity metrics were computed on that grid. For each subject, the ground-truth ET mask was resampled to the decoder resolution using nearest-neighbor interpolation to preserve binary topology.

The trained autoencoder was applied to the ET-masked MRI input and produced a reconstructed ET channel. Since the reconstructed ET channel is not a calibrated probability map, we derived a binary reconstructed mask using a volume-matched thresholding rule: for each subject, we selected the top-K voxels from the reconstructed ET score map, where K equals the number of voxels in the resampled ground-truth ET mask. This produces a non-empty reconstructed mask with matched volume, enabling fair comparison of shape-based morphometrics independent of absolute intensity calibration.

Fractal dimension (DF) was computed via 3D box-counting for both the resampled ground-truth ET mask and the reconstructed (volume-matched) ET mask, yielding DFtrue, DFrecon, and ΔDF = DFrecon − DFtrue. In addition, we computed the mean squared reconstruction error (MSE) on the decoder grid (over all reconstructed channels) and evaluated whether reconstruction error was associated with morphometric distortion by correlating MSE with ∣ΔDF∣. This analysis directly tests whether the latent representation and decoding process preserves the fractal morphometric quantity used in the DF–λ framework.

2.4. Synthetic Morphological Trajectories

Because BraTS provides only static preoperative MRI scans, we construct synthetic temporal trajectories to probe how local tumor morphology might evolve under smooth boundary perturbations. These trajectories provide the continuous variations needed to train a Neural ODE while avoiding assumptions about true chronological growth.

Generation of morphological sequences

For each subject:

- Initialization

The enhancing–tumor (ET) binary mask M0 is used as the starting shape.

- 2.

- Controlled morphological transformation

A sequence of 3D morphological dilations and erosions is applied using a spherical 3 × 3 × 3 structuring element S. Dilation expands the boundary, whereas erosion contracts it, providing small, controlled shape perturbations.

- 3.

- Stochastic jitter

At each step, a random jitter factor (±15%) perturbs whether the next transformation is a dilation or erosion. This produces asymmetric, non-deterministic transitions that prevent the ODE from learning a trivial, fixed operator.

These operations generate a 24-step bidirectional sequence:

Mt, t = 0, …, 23,

This consists of progressive dilations followed by erosions, producing a smooth, reversible shape path.

Embedding synthetic morphologies

Each mask Mt is applied voxel-wise to the normalized 4-channel MRI volume:

This emphasizes the evolving tumor region.

Passing Xt through the autoencoder encoder fθ yields latent states:

Thus, each subject provides a smooth synthetic latent trajectory {zt} suitable for continuous-time Neural-ODE training.

2.4.1. Rationale for Synthetic Morphological Trajectories

BraTS lacks longitudinal scans, making true tumor dynamics unobservable.

To enable continuous-time modeling, we approximate infinitesimal boundary variations using controlled 3D dilation and erosion.

This choice is motivated by both biological and mathematical considerations:

(1) Local boundary deformation is a core mechanism of GBM invasion.

Glioblastoma expands through localized protrusions and regressions at the tumor–brain interface. Morphological dilation and erosion provide principled approximations of such small-scale boundary movements, without imposing assumptions about global growth patterns.

(2) Dilation–erosion forms a smooth family of shape transformations.

Mathematical morphology defines a semigroup of monotonic boundary mappings. Repeated dilation and erosion generate a continuous path of admissible shapes:

providing a well-behaved trajectory compatible with Neural ODE training.

(3) Bidirectional sequences remove ordering ambiguity.

Without true time labels, morphological transitions could be arbitrarily permuted. A symmetric grow–shrink trajectory enforces a consistent ordering and prevents degeneracies in which the ODE “memorizes” random permutations rather than learning a coherent latent-space flow.

(4) The goal is not to model biological time, but to probe latent-space geometry.

The dilation–erosion operator is not the object being learned.

It is merely a tool to sample local shape perturbations around each tumor.

The Neural ODE learns the vector field that best interpolates between the resulting latent embeddings—i.e., the intrinsic geometry of each subject’s morphology manifold—rather than the synthetic operator itself.

Importantly, the Neural ODE does not learn the dilation–erosion operator; the operator is used solely to sample infinitesimal perturbations, while the ODE learns the latent-space flow that best explains these variations.

2.4.2. Cross-Generator Synthetic Trajectories (SDF Perturbation Family) and Negative Control

Because BraTS provides only static preoperative MRI scans, we further evaluated whether the learned latent dynamics depend on a specific synthetic generator by introducing an independent deformation family and a negative control in addition to the baseline dilation–erosion trajectories described in Section 2.4.

(A) Baseline generator (morphological dilation–erosion).

We used the same 24-step bidirectional dilation → erosion sequence with a 3 × 3 × 3 structuring element and 15% stochastic jitter as described in Section 2.4, producing a mask sequence with T = 24.

(B) Alternative generator (signed-distance-field + smooth random field perturbations).

To obtain shape trajectories that do not arise from repeated dilation/erosion, we generated an alternative sequence using a signed distance field (SDF) representation of the binary ET mask M0. Let denote the signed distance function of M0, defined as the (unsigned) Euclidean distance to the boundary with negative sign inside the tumor and positive sign outside. We generated a smooth spatial perturbation field g(x) by sampling i.i.d. Gaussian noise on Ω and applying 3D Gaussian filtering (standard deviation σ voxels), followed by normalization to unit standard deviation. A time-dependent SDF sequence was then constructed as:

where a is an amplitude parameter (in voxel units) and αt is a bidirectional schedule that increases from 0 to 1 and then decreases from 1 back to 0 (matched to the 24-step design). Each SDF frame was converted back to a binary mask by thresholding:

This procedure produces smooth, non-morphological boundary deformations that are independent of the dilation–erosion operator.

(C) Negative control (time-shuffled trajectories).

To test whether any apparent dynamical structure can be explained by temporal ordering alone, we constructed a negative control by randomly permuting the time indices of the baseline dilation–erosion mask sequence within each subject:

where π is a uniformly random permutation of {0, …, T − 1}. The shuffled sequence preserves the set of masks but destroys coherent ordering.

Latent embedding for all generators.

For each generator (morph, SDF, shuffle), each mask Mt was applied voxel-wise to the normalized 4-channel MRI volume X and encoded using the trained 3D autoencoder encoder fθ (Section 2.3), yielding a latent sequence (Section 2.4).

2.5. Neural Ordinary Differential Equation (Neural ODE) Modeling

To model the continuous evolution of latent morphology, a Neural ODE was trained to reproduce the synthetic trajectories.

ODE formulation

The latent state evolves according to:

where f is a feed-forward network:

- Two hidden layers (64 neurons each),

- tanh activation,

- Parameterized by θ.

Numerical integration

ODE integration was performed using the Dormand–Prince (dopri5) solver implemented in torchdiffeq.

Training objective

The ODE learns to match predicted latent states to the synthetic trajectories:

Contraction regularization

To enforce biologically meaningful stability, a divergence penalty was added:

where Jf(z) is the Jacobian of the latent vector field.

This encourages negative divergence, promoting the formation of latent attractor basins rather than purely divergent flows.

Training settings

- Epochs: 900

- Optimizer: Adam, lr = 10−3

- Loss:

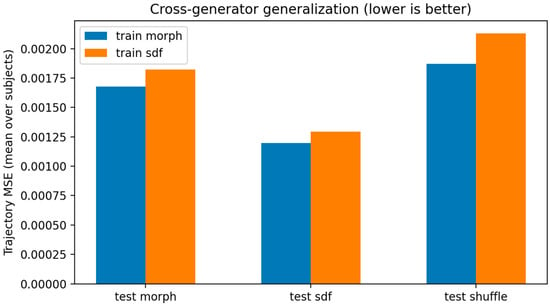

Cross-Generator Generalization Protocol

To determine whether the Neural ODE learns latent geometric structure that transfers across deformation families (rather than merely encoding a specific synthetic operator), we performed cross-generator generalization.

- Training. We trained two Neural ODE models using the same architecture and solver described in Section 2.5:

- fmorph: trained on the baseline dilation–erosion latent trajectories.

- fSDF: trained on the SDF-perturbation latent trajectories.

- Evaluation sets. Each trained model was evaluated on three trajectory sets:

- (i)

- in-generator trajectories (same generator used for training),

- (ii)

- cross-generator trajectories (the other generator family),

- (iii)

- shuffled trajectories (negative control).

- Trajectory reconstruction error (per subject). For each subject i, we integrated the learned ODE from the subject’s initial latent state zi,0 across the discrete time grid to produce . We quantified prediction fidelity using per-subject mean-squared error:

We report the distribution of MSEi across subjects using median and interquartile range (IQR), alongside the mean over subjects for reference.

2.6. Fractal Dimension (DF) and Lyapunov Exponent (λ)

Fractal dimension (DF)

Morphological complexity of the tumor boundary was quantified from the binary enhancing-tumor (ET) mask using the 3D box-counting method.

For voxel size ε, let N(ε) be the smallest number of ε—cubes required to cover the tumor mask.

The fractal dimension is defined as

Practically, DF was estimated by linear regression of versus using voxel sizes ε = 2−k that fit the tumor bounding box.

DF reflects:

- boundary irregularity,

- surface roughness,

- morphological fragmentation.

Physical interpretation of DF. In the context of glioblastoma morphology, the fractal dimension quantifies the degree of geometric irregularity and self-similar organization of the tumor boundary across spatial scales. Higher DF values correspond to more convoluted, fragmented, and infiltrative tumor interfaces, whereas lower DF indicates smoother and more compact morphologies. DF therefore acts as a scale-invariant structural descriptor of boundary complexity arising from heterogeneous invasion and microenvironmental constraints.

Physical basis of fractal dimension in tumor morphology. The fractal dimension used in this work is grounded in the physics of scale-invariant growth and interface roughening, rather than in the specifics of a numerical software implementation. Glioblastoma growth is governed by heterogeneous proliferation, anisotropic migration along white-matter tracts, variable mechanical resistance, and diffusion-limited transport of nutrients and signaling molecules. These processes collectively generate irregular, branched, and statistically self-similar tumor boundaries over a range of spatial scales.

From a physical perspective, such interfaces are well described by fractal geometry, which emerges naturally in classical models of nonequilibrium growth, including diffusion-limited aggregation, reaction–diffusion systems, and stochastic interface growth (e.g., KPZ-type dynamics). In these systems, the fractal dimension characterizes how boundary complexity scales with observation length, independent of absolute size or resolution.

In this context, the box-counting algorithm serves only as a numerical estimator of the scaling law , while the underlying physics resides in the observed power-law relationship between occupied boundary elements and spatial scale. Thus, DF captures an intrinsic, scale-invariant property of tumor boundary organization that reflects the balance between invasive growth, spatial constraints, and local heterogeneity, rather than a software-specific artifact.

Lyapunov exponent (λ)

Dynamical stability in latent space was assessed using a finite-time Lyapunov exponent (FTLE) computed from two initially close trajectories.

Initialization

For each subject, let z0 be the latent state of the original ET mask.

A small perturbation is generated as

So that

A single perturbation per subject is used; repeated trials changed λ by <0.01 and did not affect regime classification.

Trajectory integration

The original and perturbed states are integrated under the learned Neural ODE

For a fixed time window

Let z(t) and z′(t) be the resulting trajectories and d(t) = ‖z′(t) − z(t)‖ the separation.

Finite-time Lyapunov exponent

The FTLE is estimated by

which is equivalent to fitting the slope of vs. t on [0, T].

Regime classification

Subjects were categorized using a neutrality band

Testing ε ∈ [0.005,0.02] altered regime assignments in <8% of subjects, demonstrating robustness to threshold choice.

Interpretation

λ measures local latent-space divergence, not long-term dynamics:

- λ < 0: nearby trajectories converge → locally stable;

- λ ≈ 0: weakly attracting/repelling → metastable;

- λ > 0: trajectories diverge → unstable or chaotic.

Thus, λ represents a finite-time indicator of morphodynamic stability in the latent flow estimated from each subject.

Physical interpretation of λ. In this framework, the Lyapunov exponent does not describe biological time evolution or tumor growth rate. Instead, it quantifies the sensitivity of inferred latent morphodynamic trajectories to infinitesimal perturbations in shape space. Negative λ indicates contraction toward attractor-like latent configurations, while positive λ reflects divergence and morphological instability under the learned latent dynamics. λ therefore characterizes local stability of morphological configurations within the latent manifold rather than clinical aggressiveness or temporal progression.

Direction convention. In this work, λ is computed with respect to a fixed orientation of the learned latent flow, where “forward time” corresponds to the synthetic trajectory convention (dilation → erosion). Because λ is a finite-time stability index of an oriented vector field, it is generally not expected to be invariant under time reversal. Consequently, comparisons under reversed synthetic ordering should be interpreted as a directionality analysis (flow orientation change) rather than a robustness-to-reversal requirement.

2.7. Visualization and Statistical Mapping

Latent trajectory visualization

A global PCA model was fitted to all standardized latent vectors. Trajectories from individual subjects were projected into:

- 2D PCA (for qualitative regime identification),

- 3D PCA (for attractor basin exploration).

ODE-simulated trajectories were generated for continuous time t ∈ [0, 8].

DF–λ scatter plot

A scatter plot visualized each subject’s structural (DF) and dynamical (λ) descriptors. Points were color-coded according to the inferred morphodynamic regime:

- stable,

- metastable,

- unstable/chaotic.

KDE-based morphodynamic density map

A 2D Gaussian kernel density estimator (KDE) was applied to the empirical DF–λ distribution, producing a continuous density field. This map highlights:

- High-density morphodynamic phenotypes

- Low-density outlier regions

- Stable vs. unstable territories

All analyses were implemented in Python 3.12 using:

- PyTorch2.1.0+cu121

- NumPy 1.26.4

- scikit-learn 1.3.2

- torchdiffeq 0.2.3

- Matplotlib 3.7.1

2.8. Robustness and Stability Analyses

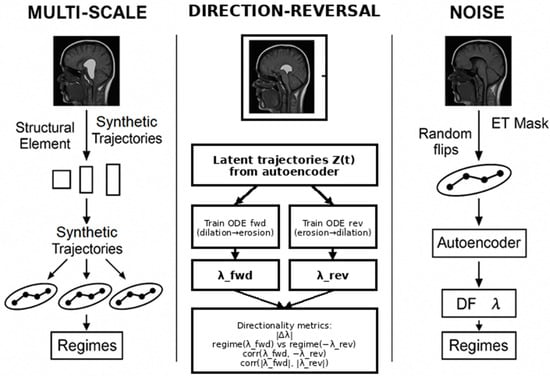

To evaluate the stability of the fractal–dynamical characterization (DF and λ) against perturbations in the synthetic morphodynamic pipeline, we performed three families of systematic robustness tests: (A) multiscale morphological perturbations, (B) temporal direction reversal, and (C) voxel-level segmentation noise perturbation. All analyses were performed on the same subset of subjects for which complete data were available (n = 369). An overview of these three workflows is provided in Figure 2, illustrating the synthetic trajectory generation and dynamical assessment steps used in each test. The three robustness procedures are described below.

Figure 2.

Overview of the three robustness and stability tests performed on the morphodynamic descriptors. (Left) Multi-scale test: morphological dilation/erosion at multiple scales is applied to the ET mask, generating synthetic trajectories whose DF and λ estimates are compared across scales. (Center) Direction-reversal test: two Neural ODEs are trained on forward vs. reversed synthetic ordering, and directionality is quantified using |Δλ|, sign-aware regime agreement via regime (λfwd) vs. regime (−λrev), and correlation diagnostics. (Right) Noise-perturbation test: random voxel flips are applied to the ET mask, and resulting DF–λ descriptors are compared to their unperturbed counterparts to evaluate robustness under stochastic perturbations.

A. Multi-Scale Dilation–Erosion Perturbation

To assess the sensitivity of λ and DF to variations in the morphological scale of the synthetic evolution process, we reconstructed synthetic sequences using three structuring-element radii: 1, 2, and 3 voxels. For each subject and each radius, we generated a 24-step bidirectional (growth–shrinkage) trajectory using iterative binary dilation and erosion, with stochastic jitter (15%) to avoid deterministic trajectories. At every time step, the ET mask was multiplied with the corresponding multi-channel MRI volume, encoded using the trained 3D autoencoder, and converted into a latent trajectory. This produced three sets of latent sequences per subject.

A separate Neural ODE was trained for each radius using the standardized latent trajectories and the same training hyperparameters. For each trained model, λ was computed via the two-trajectory Lyapunov exponent estimator based on dual integration of perturbed latent initial conditions. Regime identity (stable, metastable, unstable) was assigned according to the λ-band threshold ε = 0.01. Results were compared across radii to quantify (i) global λ correlations, (ii) regime consistency, and (iii) DF stability.

Scale normalization of λ. Because dilation–erosion trajectories generated with different structuring-element radii produce different effective boundary displacements per synthetic step, the raw λ estimated “per step” is expected to be scale-conditioned. To enable cross-scale comparison, we additionally report scale-normalized stability indices that quantify instability per unit deformation. Let drd_rdr denote a mask-based deformation proxy defined as the mean normalized symmetric difference between successive masks along the radius-rrr trajectory, , and let denote the latent trajectory arc length. We then compute and , which normalize λ by morphological and latent step size, respectively.

B. Temporal Direction-Reversal Perturbation

To evaluate the directionality of the learned latent dynamical flow under reversal of the synthetic evolution convention, we constructed the reverse latent trajectories by inverting the temporal order of the baseline synthetic sequences. Two ODE models were trained independently: one on the forward dilation → erosion trajectories and one on the reversed erosion → dilation trajectories.

For each subject, λ was computed from the initial latent state of each model using the same perturbation-based Lyapunov estimator. Because λ is a finite-time stability index of an oriented vector field, it is not expected to be invariant under time reversal. Therefore, directionality was quantified using:

(i) the mean absolute difference ∣Δλ∣ between the forward-trained and reverse-trained models;

(ii) a sign-aware regime agreement that accounts for flow orientation by mirroring the reverse-trained estimate across λ = 0, i.e., comparing regime (λfwd) with regime (−λrev); and

(iii) correlation diagnostics between λfwd and −λrev (directional consistency) and between ∣λfwd∣ and ∣λrev∣ (magnitude consistency).

C. Noise Perturbation of the ET Mask

To assess robustness to segmentation inaccuracies, we applied random voxel flips to the ET mask at three noise levels: 1%, 2%, and 3% of voxels uniformly sampled across the tumor volume. For each noise condition, the perturbed mask was used to regenerate a full synthetic 24-step trajectory following the same dilation–erosion process as in the baseline model. Latent trajectories were reconstructed using the trained autoencoder, and a new ODE model was trained for each noise level.

For every subject and noise level, DF was recomputed using 3D box-counting on the noisy ET mask, and λ was recomputed using the trained noise-conditioned ODE. Regime preservation was evaluated by comparing the noisy regimes to the baseline regime. Robustness was quantified using: (i) mean percent DF change, (ii) mean |Δλ| relative to the baseline model, and (iii) the percentage of subjects retaining their original regime.

Ordering negative control. To assess whether λ merely encodes discrete sequence ordering, we additionally evaluated λ under a time-shuffled control in which the same masks are permuted (Section 2.4.2 C) while using the same trained ODE and the same Lyapunov estimator. This isolates potential ordering artifacts from stability properties induced by the learned vector field under a fixed convention.

Lyapunov Exponent Computation

Across all experiments, λ was estimated using a two-trajectory method, where a small perturbation δz0 (‖δz0‖ = 10−3) was added to the initial latent state z0, and both trajectories were integrated using the trained Neural ODE. The Lyapunov exponent λ was obtained as the slope of the linear fit of log‖z(t) − z′(t)‖ over continuous integration time (T = 8.0, 256 steps). A regime was assigned as stable (λ < −ε), unstable (λ > ε), or metastable (|λ| ≤ ε), with ε = 0.01.

Fractal Dimension Estimation

The fractal dimension DF was computed on each ET mask (baseline and perturbed) using a 3D box-counting algorithm over multiple box sizes {1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32}. The slope of log N(s) versus log(1/s) was used as the box-counting fractal dimension.

Statistical Test for Cross-Generator Generalization

To test whether cross-generator generalization is better than the negative control at the subject level, we used a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test on per-subject errors. For a given trained model, we compared versus using paired differences:

We tested the one-sided alternative hypothesis Δi > 0 (i.e., cross-generator error is lower than shuffled error). This analysis was performed on the subset of cases with complete masks available (n = 369), consistent with the robustness analyses described in Section 2.8.

2.9. Clinical and Biological Variables

Patient metadata from the BraTS 2020 dataset—including age, survival time (in days), and extent of resection (GTR vs. STR)—were merged with the DF–λ descriptors using unique subject identifiers. Age and survival time were sufficiently complete for analysis, whereas segmentation-derived tumor volumes and molecular markers (e.g., IDH, MGMT) could not be consistently aligned with the morphodynamic dataset and were therefore excluded.

Because survival times in BraTS are partially right-censored and lack comprehensive treatment variables or censoring indicators, all clinical analyses were performed strictly for exploratory purposes. Pearson correlations were computed between fractal dimension (DF), Lyapunov-like exponent (λ), age, and survival to provide descriptive measures of association. Higher DF showed a modest negative association with overall survival, whereas λ demonstrated no measurable relationship with outcome.

To visualize potential survival gradients, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated for the lowest and highest DF quartiles, and the log-rank test was applied as an exploratory comparison. In addition, DF–λ scatter plots were color-coded by survival category (short ≤ 9 months; long ≥ 18 months) to illustrate qualitative clinical trends within the morphodynamic phase space. No Cox regression, multivariate modeling, or adjustment for confounders was performed due to incomplete clinical covariates.

These analyses are hypothesis-generating only and should not be interpreted as evidence that DF or λ are independent prognostic biomarkers.

3. Results

3.1. Dataset and Latent Representation

A total of 494 BraTS 2020 subjects were successfully processed following quality control. Each MRI volume was encoded into a 16-dimensional latent representation using a trained 3D convolutional autoencoder.

The latent space captured key morphological attributes, including boundary irregularity, asymmetry, and the internal distribution of enhancing and necrotic tumor components.

Across the validation subset, the autoencoder achieved a mean reconstruction error of 0.70 ± 0.06 MSE, indicating accurate preservation of structural details after compression.

Autoencoder Morphometric Fidelity (DF Preservation)

Autoencoder morphometric fidelity (DF preservation). To quantify whether the autoencoder compression distorts boundary morphometry, we compared fractal dimension computed on the ET mask resampled to the decoder grid (49 × 49 × 49) versus a volume-matched reconstructed ET mask derived from the decoder ET channel. Across cases with non-empty resampled ET masks (n = 341), DF was strongly preserved (corr(DFtrue, DFrecon) = 0.9568; Supplementary Figure S1a), indicating that the autoencoder retains the global boundary-complexity statistic used in the DF–λ analysis. In addition, reconstruction MSE showed no clear monotonic relationship with ∣ΔDF∣ (Supplementary Figure S1b), suggesting that residual reconstruction error is not the dominant driver of DF variability in this pipeline.

3.2. Latent Morphodynamic Trajectories

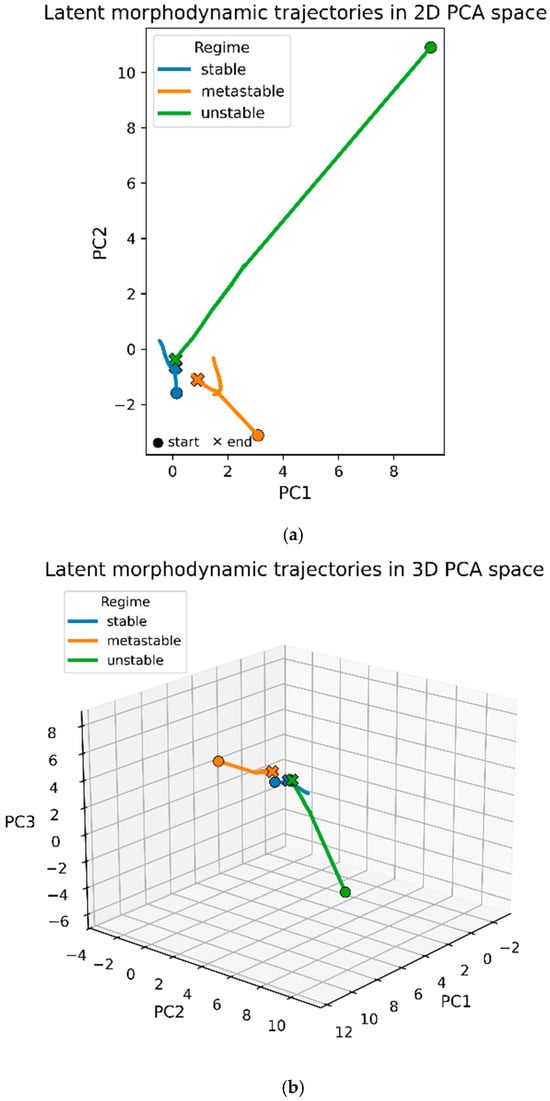

Continuous morphodynamic evolution was modeled using the Neural ODE trained on synthetic dilation–erosion sequences. Figure 3 illustrates three representative latent trajectories projected into a globally fitted PCA space.

Figure 3.

Latent morphodynamic trajectories in PCA space. (a) Two-dimensional PCA projection (PC1–PC2) of three representative synthetic latent trajectories selected from the stable (blue), metastable (orange), and unstable (green) morphodynamic regimes. Each curve corresponds to a single subject; circles mark initial latent states and crosses the final states. Stable trajectories remain short and localized, metastable trajectories show modest drift, while unstable trajectories extend along a broad arc in PCA space. (b) Three-dimensional PCA projection (PC1–PC3) of the same subjects. Stable and metastable trajectories remain confined to a compact region of latent space, whereas unstable trajectories exhibit large, smoothly diverging paths along a dominant latent direction. Axes are shared across trajectories; differences in path length reflect intrinsic differences in dynamical stability.

In the 2D PCA projection (Figure 3a), trajectories exhibit three characteristic patterns:

- Stable trajectories (blue) remain short and tightly localized, reflecting strong contraction toward a small region of the latent space. Their limited spatial extent is consistent with the negative Lyapunov exponents measured for these subjects.

- Metastable trajectories (orange) show slightly larger excursions with mild directional drift. They maintain overall coherence but do not converge as strongly as stable trajectories, consistent with λ close to zero.

- Unstable trajectories (green) display markedly larger displacement and curvature, extending over a broader region of the PCA manifold. These elongated flows correspond to positive Lyapunov exponents and reflect divergent latent dynamics.

The 3D PCA visualization (Figure 3b) reveals additional structure in the unstable trajectories, which exhibit smooth monotonic arcs rather than oscillatory loops. Stable and metastable trajectories remain confined to a compact neighborhood around the PCA origin, whereas unstable trajectories extend outward along a dominant latent direction. This separation in trajectory extent, rather than trajectory shape, is the clearest morphological signature distinguishing the three regimes.

Overall, the PCA-projected trajectories confirm the existence of contraction-dominated regions (stable), weakly drifting manifolds (metastable), and divergent flow directions (unstable) in the learned morphodynamic vector field.

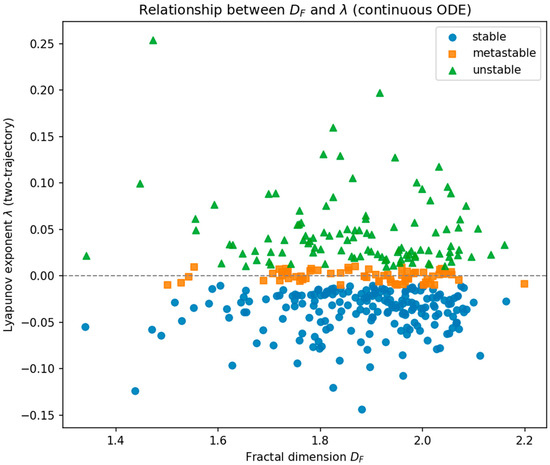

3.3. Morphodynamic Phase Space (DF–λ Relationship)

Lyapunov exponents were computed as finite-time divergence rates over T = 8.0 using an initial perturbation of norm 10−3, as detailed in Section 2.6.

Of the 494 subjects, 369 produced valid paired-trajectory simulations for estimating:

- Fractal dimension (DF) of tumor boundaries

- Lyapunov exponent (λ) quantifying latent trajectory divergence

Observed values were:

- DF: 1.34–2.20 (mean 1.88 ± 0.15)

- λ: −0.14 to +0.15 (mean −0.006 ± 0.047)

The Pearson correlation between DF and λ was weakly negative (r ≈ −0.13, p ≈ 0.01), indicating that geometric complexity and dynamical stability capture partially independent morphodynamic properties.

Higher DF did not systematically imply higher λ, contrary to expectations from synthetic dynamical systems.

Based on λ, tumors were categorized into three regimes:

- Stable (λ < 0): 178/369 (48.2%)

- Metastable (λ ≈ 0): 77/369 (20.9%)

- Unstable/chaotic (λ > 0): 114/369 (30.9%)

Figure 4 shows the DF–λ scatter plot with tumors color-coded by regime. Regime separation occurs primarily along λ, whereas DF varies more continuously across the cohort.

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of fractal dimension (DF) versus Lyapunov exponent (λ) for 369 BraTS 2020 tumors. Each point represents one subject and is color-coded according to its morphodynamic regime derived from the Neural ODE dynamics: stable (blue, λ < 0), metastable (orange, λ ≈ 0), and unstable (green, λ > 0). The dashed horizontal line marks λ = 0, separating convergent from divergent latent trajectories. Across the cohort, DF ranges from approximately 1.34 to 2.20, while λ spans −0.14 to +0.15. Regime separation occurs primarily along the λ axis, whereas DF varies more continuously across subjects, reflecting the partially independent contributions of geometric complexity and dynamical stability.

3.4. Empirical Morphodynamic Density Map (KDE Density)

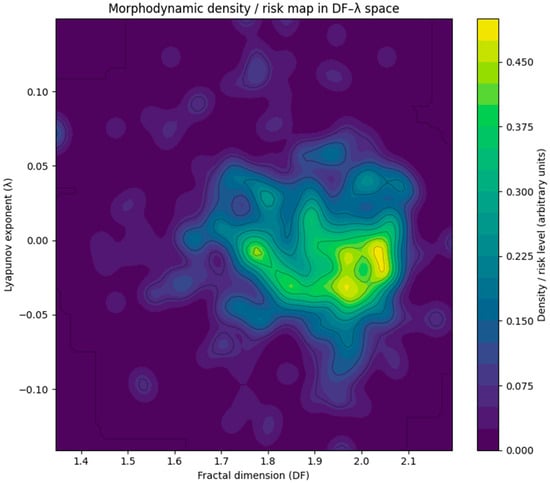

To characterize the population-level distribution of tumors in the DF–λ space, a two-dimensional Gaussian kernel-density estimator (KDE) was computed using all 369 valid subjects. Figure 5 displays the resulting density map. Warmer colors correspond to regions with higher subject density, representing frequently observed morphodynamic profiles.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional kernel-density estimate (KDE) of the distribution of tumors in the DF–λ morphodynamic space, computed from all 369 subjects with valid measurements. Warmer colors indicate regions of higher subject density. A single dominant cluster is observed around DF ≈ 1.85–2.00 and λ ≈ −0.02 to +0.01, corresponding to morphologies that combine moderate-to-high geometric irregularity with near-neutral dynamical stability (metastable regime). Regions with high DF and clearly positive λ show comparatively low density, suggesting that strongly unstable morphodynamic behavior is rare. In contrast, tumors with smoother boundaries (low DF) and strongly negative λ also populate low-density regions. Together with Figure 4, this KDE map reinforces that most glioblastomas occupy a narrow band around λ ≈ 0 with DF in the upper mid-range, indicating a characteristic metastable morphodynamic phenotype.

A single dominant high-density cluster appears near:

- DF ≈ 1.85–2.00

- λ ≈ −0.02 to +0.01

This region lies at the center of the metastable regime, indicating that most glioblastomas exhibit moderate-to-high geometric irregularity combined with near-neutral dynamical behavior. Such configurations may reflect morphologies that are heterogeneous yet dynamically balanced, consistent with slowly drifting or quasi-stationary growth patterns.

In contrast, tumors with low DF and strongly negative λ populate a low-density region, corresponding to smoother, strongly stable morphologies. Likewise, tumors with clearly positive λ (unstable dynamics) are relatively rare, forming only sparse density ridges toward the higher-DF range.

Together with the scatter plot (Figure 4), the KDE map provides a unified structural–dynamical characterization of glioblastoma morphodynamics, revealing that the majority of tumors occupy a narrow band around λ ≈ 0, with DF clustered just below 2.0—suggesting a characteristic metastable morphodynamic phenotype within the population.

3.5. Robustness and Stability Tests (A–C)

We conducted three robustness experiments to evaluate the stability of the DF–λ morphodynamic characterization under controlled perturbations to the synthetic evolution process and the ET segmentation mask. All results below reflect the common subset of subjects for whom complete data were available (n = 369).

A. Multi-Scale Dilation–Erosion Test

Synthetic trajectories generated with structuring-element radii of 1, 2, and 3 voxels exhibited low pairwise correlations between the corresponding raw Lyapunov exponents (r12 = 0.176, r13 = 0.176, r23 = 0.209), confirming that λ estimated per synthetic step is scale-conditioned under changes in morphological perturbation radius. This behavior is expected because larger radii induce larger effective boundary displacements per step, so λ “per step” is not directly comparable across scales.

To enable cross-scale comparison, we computed a deformation-normalized stability index , where dr is the mean normalized symmetric difference between successive masks along the radius-r trajectory. After normalization, cross-radius agreement became very high (r12 = 0.974, r13 = 0.975, r23 = 0.988), demonstrating that the instability signal is consistent across radii once deformation step size is controlled (Supplementary Figure S2). Accordingly, we interpret λ as a scale-conditioned stability index and recommend reporting normalized λ* for cross-scale comparisons.

Despite the scale dependence of raw λ, 38.5% of subjects preserved the same dynamical regime (stable, metastable, or unstable) across all three scales, indicating that categorical regime structure is more stable than absolute λ magnitude.

B. Direction-Reversal Test (directionality; sign-aware comparison)

Reversing the synthetic trajectory order (erosion → dilation) produced a mean absolute Lyapunov difference of ∣Δλ∣ = 0.0436| relative to the forward-trained model. Because λ is direction-conditioned, reversal is not expected to preserve λ or regime labels without accounting for flow orientation. We therefore evaluated sign-aware regime agreement by mirroring the reverse-trained estimate across λ = 0 and comparing regime (λfwd) to regime (−λrev). Under this sign-aware comparison, 44.2% of subjects retained the same regime. Correlation diagnostics further indicated substantial directional dependence, with corr(λfwd, −λrev) = −0.5462 and corr(∣λfwd∣, ∣λrev∣) = −0.1158. Together, these results show that reversal alters the inferred local vector field orientation and thus λ, while a non-trivial fraction of categorical regime structure is preserved after sign handling, supporting interpretation of λ as a direction-conditioned latent stability index rather than a time-reversal-invariant biomarker.

C. Noise Perturbation Test

Random ET-mask voxel flips of 1%, 2%, and 3% were used to simulate segmentation noise. For each noise level, new synthetic trajectories and ODE models were reconstructed. The results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dataset summary and autoencoder performance.

1% noise

- Mean DF change: 5.40%

- Mean |Δλ|: 0.0459

- Regime preserved in 70.5% of subjects

2% noise

- Mean DF change: 12.90%

- Mean |Δλ|: 0.1207

- Regime preserved in 72.6% of subjects

3% noise

- Mean DF change: 17.91%

- Mean |Δλ|: 0.1732

- Regime preserved in 72.6% of subjects

Although DF and λ both increase in sensitivity with noise magnitude, the dynamical regime remains stable in approximately 70–73% of cases, even under 3% voxel perturbations. This indicates that regime classification is substantially more robust than the raw metric values and tolerant to plausible segmentation inaccuracies.

Summary. Across all perturbation experiments, raw DF and λ values displayed expected sensitivity to morphological scale and voxel-level noise; direction reversal primarily probes directionality rather than invariance (sign-aware regime agreement reported above). However, the regime classification demonstrated markedly greater resilience—ranging from 38.5% consistency under large-scale perturbations to ~72% under noise perturbations. These results support the view that the DF–λ morphodynamic landscape is structurally coherent and that the extracted dynamical regimes constitute a stable and meaningful descriptor of glioblastoma morphology.

Regime Stability Summary.

Across all perturbation experiments, categorical regime assignments were substantially more stable than the raw λ values. Even when λ varied due to scale, sequence direction, or voxel noise, the stable–metastable–unstable partition preserved clear structure across the cohort. This robustness indicates that the dynamical regimes reflect intrinsic latent-space organization rather than artifacts of a specific synthetic generator.

Cross-Generator Generalization and Negative-Control Validation

Because BraTS provides cross-sectional scans rather than longitudinal follow-up imaging, we performed an additional validation to test whether the learned latent dynamics primarily reflect artifacts of the dilation–erosion generator or whether they capture latent geometric regularities that transfer across deformation families.

For each subject with complete ET masks (n = 369), we constructed three trajectory sets: (i) the baseline bidirectional dilation–erosion (“morph”) trajectories, (ii) an independent signed-distance-field (SDF) perturbation family generated by smooth random fields, and (iii) a time-shuffled morph trajectory as a negative control that preserves the same set of masks but destroys coherent ordering.

We trained two Neural ODE models using identical architecture and solver settings: one model trained on morph trajectories and one model trained on SDF trajectories. We evaluated each trained model on all three trajectory sets using per-subject latent-space trajectory reconstruction MSE (median and IQR across subjects).

Morph-trained model. The morph-trained ODE achieved lowest error on in-generator morph trajectories (median MSE 0.001510 [IQR 0.001070–0.002086], mean 0.001677). Importantly, it predicted SDF trajectories substantially better than the shuffled control (median 0.001076 [0.000681–0.001534], mean 0.001198 vs. shuffled median 0.001566 [0.001071–0.002363], mean 0.001870). This cross-generator improvement was significant (paired Wilcoxon p = 1.455 × 10−46), with a median per-subject improvement (shuffle − SDF) of 0.000437.

SDF-trained model. The SDF-trained ODE achieved lowest error on in-generator SDF trajectories (median 0.001179 [0.000821–0.001609], mean 0.001295). It also predicted morph trajectories better than shuffled trajectories (median 0.001693 [0.001223–0.002180], mean 0.001821 vs. shuffled median 0.001797 [0.001259–0.002567], mean 0.002131). This improvement was significant (paired Wilcoxon p = 8.601 × 10−7), with median improvement (shuffle − morph) of 0.000117.

Overall, cross-generator prediction was consistently better than the negative-control shuffle baseline (Figure 6), indicating that the inferred latent flow is not explained by synthetic ordering alone. However, the magnitude of transfer was asymmetric, suggesting partial generator dependence. We therefore interpret the synthetic trajectories as a morphodynamic probe of latent shape geometry, rather than biological time-resolved tumor progression.

Figure 6.

Cross-generator generalization with negative control (n = 369). Mean per-subject latent-trajectory MSE (lower is better) for Neural ODEs trained on morph (dilation–erosion) or SDF perturbation trajectories and evaluated on morph, SDF, and time-shuffled trajectories. Cross-generator prediction is significantly better than shuffled control for both training directions (morph → SDF: p = 1.455 × 10−46; SDF → morph: p = 8.601 × 10−7; paired Wilcoxon).

3.6. Exploratory Clinical and Biological Associations

Given the cross-sectional nature of the cohort, these associations are hypothesis-generating and should not be interpreted as evidence of longitudinal progression.

Note on Survival Statistics. Survival times in the BraTS dataset are highly non-Gaussian and partially right-censored. Therefore, Pearson correlations and Kaplan–Meier analyses are used here only as exploratory, descriptive tools. In addition to these descriptive tools, we performed an exploratory Cox proportional-hazards sensitivity analysis using available covariates (age and extent of resection), but clinical interpretation remains limited by incomplete treatment and molecular annotation. All associations reported in this section should thus be interpreted as preliminary descriptive patterns rather than prognostic claims.

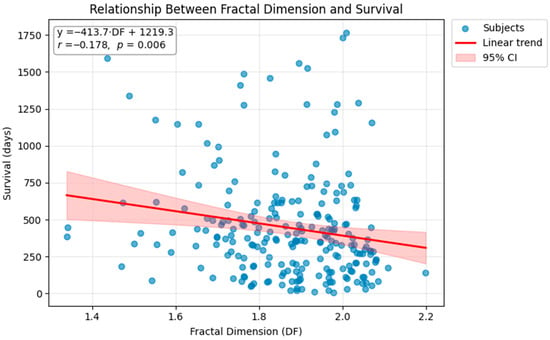

To provide preliminary clinical anchoring for the morphodynamic descriptors, we examined relationships between fractal dimension (DF), Lyapunov-like stability (λ), subject age, and overall survival. Across the cohort, λ showed no meaningful association with age (r = 0.03, p = 0.65) or with survival (r = 0.056, p = 0.387), consistent with its intended interpretation as a latent measure of local dynamical stability rather than a surrogate for demographic or clinical variables. DF exhibited a weak, non-significant positive trend with age (r = 0.11, p = 0.10). In contrast, DF demonstrated a modest negative association with overall survival (r = −0.178, p = 0.006). This unadjusted association should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating only; because key covariates (e.g., treatment, molecular markers, and consistent censoring indicators) are unavailable, we cannot assess whether DF provides independent prognostic information.

Adjusted survival sensitivity analysis. To assess whether the observed DF–survival association persists after adjustment for available confounders, we fit an exploratory Cox proportional-hazards model including age and extent of resection (EOR), together with DF and λ. In univariable Cox analysis, DF was associated with increased hazard (HR per SD = 1.168, 95% CI 1.025–1.331, p = 0.020), whereas λ was not (HR = 0.964, p = 0.580). In the multivariable model (DF + λ + age + EOR), the DF effect attenuated and was no longer significant (HR = 1.116, 95% CI 0.984–1.265, p = 0.087), while age remained strongly associated with hazard (HR = 1.468, p = 6.1 × 10−8). These results remain exploratory and do not establish independent prognostic utility.

A scatter plot illustrating the DF–survival relationship is shown in Figure 7, highlighting the modest negative trend and the visually higher density of short-survival cases at higher DF values.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between fractal dimension (DF) and overall survival (days). Each point corresponds to one subject in the cohort. A linear regression fit (red line) with 95% confidence intervals (shaded region) demonstrates a modest but statistically significant negative association between DF and survival (r = −0.178, p = 0.006). Patients with more irregular and complex tumor boundaries tended to exhibit shorter survival times. This exploratory association is descriptive and requires confirmation in external cohorts with multivariable survival modeling.

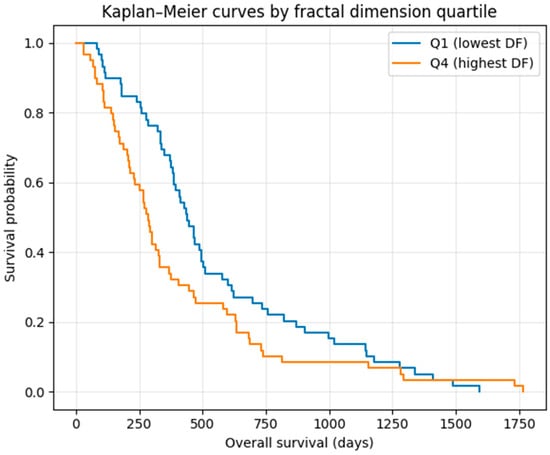

To further contextualize this pattern, we computed Kaplan–Meier curves stratified by DF quartile, focusing on the lowest-DF (Q1) and highest-DF (Q4) groups (Figure 8). Patients in the lowest-DF quartile (Q1) exhibited the longest median survival (438 days), whereas those in the highest-DF quartile (Q4) showed the shortest median survival (286 days), consistent with the unadjusted DF–survival association observed in this cohort.

Figure 8.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves comparing the lowest (Q1) and highest (Q4) quartiles of fractal dimension (DF). Patients in the lowest-DF quartile showed the longest median survival (438 days), whereas those in the highest-DF quartile exhibited the shortest median survival (286 days). The log-rank test demonstrated a trend-level separation between groups (p ≈ 0.056), consistent with the modest but statistically significant negative correlation between DF and survival observed in continuous analyses. These curves are presented for exploratory visualization only and should not be interpreted as evidence of independent prognostic stratification.

The log-rank test showed a trend-level separation between these groups (p ≈ 0.056), consistent with the modest but significant negative correlation between DF and survival in the continuous analysis. These findings suggest a weak, unadjusted association between boundary complexity and survival in this cohort; this observation is descriptive and hypothesis-generating rather than prognostic.

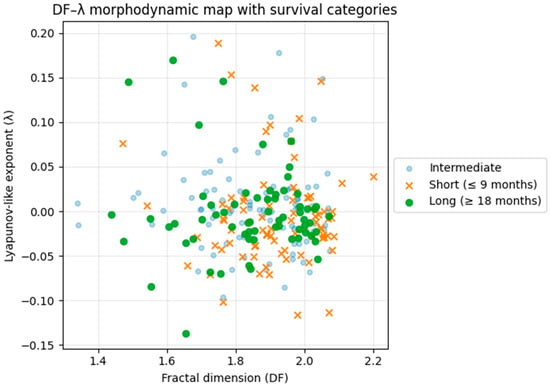

Finally, we projected survival categories onto the DF–λ morphodynamic map (Figure 9). Short-survival patients (≤9 months) were enriched toward the higher-DF region of the map, whereas long-survival patients (≥18 months) were concentrated in the moderate-DF band near λ ≈ 0. No survival gradient was observed along the λ axis, reinforcing the interpretation that λ encodes latent dynamical stability rather than biological invasiveness. Together, these exploratory overlays suggest that DF is weakly associated with survival in this dataset, while λ shows no survival association. These results do not establish clinical utility or independence from confounders and require validation in covariate-rich cohorts with formal time-to-event modeling.

Figure 9.

DF–λ morphodynamic phase map colored by survival category. Short-survival patients (≤9 months) are enriched toward higher DF values, whereas long-survival patients (≥18 months) cluster around moderate DF and near-neutral λ. No apparent gradient is observed along the λ axis, indicating that λ reflects latent dynamical stability rather than biological aggressiveness. The plot illustrates that fractal boundary complexity (DF) varies across survival categories in this dataset, while λ captures an orthogonal morphodynamic dimension; this visualization is hypothesis-generating and does not establish prognostic utility.

3.7. Summary of Findings

- The 3D autoencoder successfully captured the morphological variability of glioblastoma, generating low-dimensional latent representations that preserved global tumor geometry while smoothing fine-scale irregularities. This was supported by a reconstruction-based fidelity analysis showing strong preservation of DF (corr(DFtrue, DFrecon) ≈ 0.96 on the decoder grid; Supplementary Figure S1).

- Neural ODE training with contraction produced continuous latent trajectories that exhibited direction-dependent divergence and attractor-like structure, enabling dynamical characterization of tumor morphology.

- The DF–λ morphodynamic phase space separated tumors into stable, metastable, and unstable regimes, indicating that fractal complexity (DF) and latent dynamical stability (λ) form complementary axes of morphological variation.

- DF and λ were only weakly negatively correlated, demonstrating that boundary complexity and latent stability reflect largely independent morphodynamic properties.

- Kernel density estimation (Figure 5) revealed that most tumors cluster in a moderate-to-high DF band (≈1.85–2.00) with near-neutral λ (≈−0.02 to +0.01), indicating that the majority of cases reside in a metastable latent regime rather than strongly unstable dynamics.

- Exploratory (unadjusted) overlays suggested a small association between DF and survival in BraTS, while λ showed no association; this analysis is descriptive and not evidence of independent prognostic value. DF exhibited a modest negative correlation with overall survival (r = −0.178, p = 0.006), and Kaplan–Meier analysis (Figure 9) demonstrated that patients in the highest-DF quartile had shorter median survival than those in the lowest-DF quartile (286 vs. 438 days; trend-level log-rank p ≈ 0.056).

- Cross-generator validation. Neural ODEs trained on dilation–erosion trajectories generalized to independent SDF perturbation trajectories significantly better than a shuffled negative control (paired Wilcoxon p = 1.455 × 10−46), supporting the interpretation of the learned flow as a latent morphodynamic probe rather than an ordering artifact.

- The DF–λ survival map (Figure 9) further illustrated that short-survival patients (≤9 months) are enriched in the high-DF region, whereas long-survival patients (≥18 months) cluster around moderate DF values with near-neutral λ. No visible gradient was observed along the λ axis, reinforcing that λ captures latent dynamical stability rather than prognostic biology.

4. Discussion

This Discussion provides an integrated narrative interpretation of the proposed morphodynamic framework, linking fractal geometry, nonlinear dynamical stability, latent-space learning, and glioblastoma biology. While structured bullet points are used throughout for clarity and readability, each subsection elaborates the physical, mathematical, and biological implications of the results in detail. The Discussion is organized to progress from latent dynamical behavior to fractal boundary interpretation, robustness analysis, clinical context, limitations, and finally broader theoretical and clinical perspectives.

4.1. Morphodynamic Interpretation of Glioblastoma Evolution

The results demonstrate that glioblastoma morphology can be modeled as a nonlinear dynamical system embedded in a continuous latent space. Rather than treating tumor shape as a static radiomic snapshot, the proposed framework interprets morphology as a state evolving along a latent trajectory governed by a learned differential equation.

Within this formulation, the DF–λ phase space (Figure 3 and Figure 4) reveals three qualitatively distinct morphodynamic regimes that reflect different degrees of latent stability. Tumors classified as stable (λ < 0) exhibit short, highly contracted trajectories that rapidly converge toward compact regions of the latent manifold, consistent with strong local stability. In contrast, metastable tumors (λ ≈ 0) display modest drift with limited expansion, indicating weakly stable behavior in which trajectories neither converge rapidly nor diverge strongly. Unstable tumors (λ > 0) follow extended, smoothly diverging trajectories that span larger portions of the latent space, a pattern consistent with locally unstable or chaotic morphodynamic evolution.

Contrary to initial expectations, metastable trajectories do not exhibit oscillatory or cyclic behavior. Instead, they differ from stable trajectories primarily in their spatial extent rather than in overall geometric form. This observation is consistent with a latent vector field dominated by contraction around certain regions, coupled with directional divergence in others, rather than by closed or periodic flows.

Although the learned vector field does not contain strict fixed points in the classical dynamical-systems sense, the application of contraction regularization induces attractor-like basins in the latent space. Within these basins, trajectories slow down and cluster, forming regions of recurrent morphological configurations. This behavior suggests that glioblastoma morphology self-organizes into characteristic dynamical states, reflecting underlying constraints on boundary evolution, rather than exploring shape space arbitrarily.

4.2. Fractal and Dynamical Interpretation of Tumor Morphology

Glioblastoma margins exhibit pronounced geometric irregularity driven by infiltrative growth, microenvironmental heterogeneity, and anisotropic migration along white-matter tracts. These processes give rise to statistically self-similar and scale-dependent boundary patterns, which justify the use of fractal geometry as a structural descriptor of tumor morphology. Numerous studies have shown that glioma boundaries display fractal-like organization and that fractal metrics correlate with clinically relevant phenotypes [28,29,30,31,32,33].

4.2.1. Fractal Structure of Glioblastoma Boundaries

MRI and histopathology investigations consistently report that glioblastoma invasion fronts possess fractal scaling properties, including:

- fractal border complexity correlating with glioma grade and prognosis [28,29],

- multifractal heterogeneity reflecting invasive potential [30],

- fractal analysis of MRI-defined regions (enhancing tumor, edema, necrosis) predicting outcome [31,32],

- fractal morphological markers capturing recurrence risk and infiltrative behavior [33].

These findings support fractal measures as biologically meaningful indicators of underlying tumor growth mechanisms.

4.2.2. DF as a Fractal Invariant Under Latent Nonlinear Dynamics

Despite the nonlinear nature of the latent-space dynamics learned by the Neural ODE, the fractal dimension (DF) behaves as a quasi-invariant under such transformations due to several properties.

(a) Stability of fractal dimension under Lipschitz mappings

DF is stable under Lipschitz-continuous transformations [34,35]. Because the encoder is approximately Lipschitz, boundary complexity is preserved up to small bounded distortion:

(b) Latent flows preserve geometric adjacency

The Neural ODE ensures neighboring shapes in the latent space evolve along similar trajectories. Tumors with similar boundary roughness remain close in latent geometry, preserving relative DF ordering.

(c) Complementary roles of DF and λ

DF encodes the static fractal configuration of the tumor boundary, while λ quantifies the local divergence or contraction of morphological configurations under inferred dynamics. This decomposition parallels fractal evolution models where geometric state and dynamical tendency are distinct.

(d) Empirical evidence through perturbation tests

Noise-perturbation analysis shows DF changes by 5–18% under voxel corruption, but ≈70–73% of subjects maintain their dynamical regime classification, demonstrating DF’s anchoring role in the latent morphodynamic space.

4.2.3. Multifractal Analysis Asan Extension

Tumors often exhibit multifractal behavior where local scaling exponents vary across the boundary. Prior studies demonstrate multifractal spectra in glioma texture and margin heterogeneity [30,36], suggesting that generalized dimensions Dq and singularity spectra f(α) could capture subtler variations in infiltration. Incorporating multifractal descriptors into the DF–λ framework may reveal high-order instability patterns not apparent from global DF alone.

4.2.4. Fractal Boundary Evolution and Nonlinear Dynamics

Fractal tumor morphology can be interpreted through the lens of several classical models of nonequilibrium interface growth. Diffusion-Limited Aggregation (DLA) generates highly branched, irregular growth fronts that closely resemble invasive glioma protrusions observed at tumor margins [37]. Similarly, the Kardar–Parisi–Zhang (KPZ) model of stochastic interface growth captures surface-roughening dynamics analogous to the fluctuating tumor boundary driven by heterogeneous proliferation and microenvironmental noise [38].

Beyond these models, anomalous and fractional diffusion frameworks have been proposed to explain the superdiffusive migratory behavior of glioma cells, where effective transport exceeds that predicted by classical Brownian motion [39]. Reaction–diffusion equations incorporating spatially heterogeneous diffusivity further generate complex, fractal-like morphological patterns in brain-tumor simulations, reflecting the coupling between proliferation, invasion, and tissue anisotropy [10]. In addition, mechanical wrinkling models of tumor–stroma interaction account for corrugated boundaries and multiscale roughness arising from mechanical stress, differential growth, and elastic mismatch between tumor and surrounding tissue [40].

Taken together, these physical and mathematical frameworks support interpreting fractal dimension (DF) as a quantitative measure of the current geometric complexity of the tumor boundary, while the Lyapunov exponent (λ) captures the local dynamical tendency of morphological configurations to stabilize or diverge under perturbation. Their joint consideration therefore yields a geometric–dynamical signature analogous to the pairing of state and local stability in nonlinear dynamical systems, providing a unified perspective on tumor shape organization and evolution.

4.2.5. Relation to PDE-Based Fractal and Bioheat Tumor Models

Recent studies have investigated tumor complexity using fractal or fractional formulations embedded within partial differential equation (PDE) frameworks, particularly bioheat and reaction–diffusion models. In these approaches, fractal geometry is typically introduced through non-integer spatial dimensions, fractional derivatives, or effective medium parameters to account for heterogeneous heat transport, perfusion, and thermal memory during tumor growth or hyperthermia treatment. The primary outputs of such models are temperature fields, thermal dose distributions, or stability regimes of heat propagation in tumor–tissue systems.

The present work differs fundamentally in scope and modeling philosophy. We do not solve a bioheat or reaction–diffusion PDE, nor do we treat fractal dimension as a parameter within a governing equation. Instead, fractal dimension (DF) is measured directly from MRI-derived tumor morphology as a scale-invariant descriptor of boundary complexity, and is combined with a Lyapunov-like exponent (λ) that characterizes local dynamical stability of inferred latent morphodynamic flows learned from data via a Neural ODE.

Thus, while PDE-based bioheat models focus on physical transport processes (e.g., heat diffusion, perfusion, thermal relaxation) under prescribed boundary and material parameters, our framework focuses on geometric organization and stability of tumor shape evolution in a learned latent space. The two approaches are therefore complementary rather than competing: PDE/bioheat models address how tumors respond thermally to treatment, whereas the present method characterizes how tumor morphology is organized and perturbed under latent morphodynamic dynamics.

Importantly, the imaging-derived fractal dimension used here could, in principle, inform or constrain PDE-based models by providing patient-specific, scale-invariant measures of morphological heterogeneity. Conversely, bioheat or reaction–diffusion simulations could offer mechanistic interpretations for the observed fractal boundary organization. Exploring such couplings represents a promising direction for future multiscale tumor modeling.

4.2.6. Relation to Real-World Glioblastoma Aggressiveness and Morphological Stability