1. Introduction

Fractal geometry has proven valuable for understanding complex natural and mathematical structures [

1], from the branching patterns of trees to the rugged coastlines of continents [

2]. At the heart of this field lies the concept of fractal dimension, a quantitative measure that captures the intrinsic complexity and self-similarity of fractal objects. Among various definitions, the box-counting dimension (also known as the Minkowski dimension) has become widely adopted due to its computational tractability and broad applicability [

3,

4]. Lindenmayer systems (L-systems), originally introduced by Aristid Lindenmayer for modeling plant development [

5], provide a useful computational formalism for generating fractal patterns through simple recursive string rewriting rules. The appeal of L-systems lies in their ability to produce intricate, self-similar structures from remarkably concise rule sets, making them valuable tools in computer graphics, procedural content generation, and biological modeling.

Despite decades of research on both fractal dimensions and L-systems, one challenge remains largely unaddressed: the reverse design problem. Given a target box-counting dimension D, can we systematically construct a fractal with precisely this dimension? This inverse problem stands in contrast to the well-studied forward direction, where researchers compute dimensions from existing fractals.

The reverse design problem has practical implications across several domains. In computational art, designers seek to create fractal patterns with specific complexity levels to achieve desired esthetic effects. In natural simulation, researchers need to model trees, plants, and landscapes with prescribed structural properties that match real-world observations. Game developers require procedural terrain and texture generation with controlled complexity for performance optimization. Data compression algorithms could potentially leverage the self-similarity inherent in fractals if suitable L-system representations could be systematically identified. In architectural design, fractal-based structural elements are increasingly explored for both functional and esthetic purposes, necessitating precise control over dimensional properties.

The existing literature, while extensive, reveals gaps in addressing this reverse design challenge. Barnsley’s pioneering work on iterated function systems (IFSs) [

6] and subsequent extensions by Vrscay [

7] tackled an inverse problem for affine transformations, aiming to find parameters that best approximate target images through fractal image compression. However, these approaches focus on pixel-level image matching rather than dimension-driven design, and they do not provide L-system interpretations suitable for procedural generation or symbolic manipulation. The IFS framework optimizes transformation coefficients to minimize visual error but offers no direct mechanism to prescribe and guarantee a specific fractal dimension.

Turning to L-systems themselves, most research [

5,

8] addresses the forward direction: given an L-system with a defined axiom, production rules, and interpretation parameters, analyze its emergent properties, such as growth rate, branching complexity, and visual appearance. Lindenmayer’s original formulation emphasized biological fidelity through hand-crafted rules that capture observed developmental processes but provided no systematic methodology for constructing L-systems from desired abstract properties. Automated methods for synthesizing L-systems from target specifications, whether dimensional, topological, or esthetic, remain scarce in the literature. This asymmetry between analysis and synthesis represents a bottleneck for practitioners who know what fractal properties they desire but lack principled tools to achieve them.

Parallel developments in fractal dimension estimation have produced algorithms for measuring the complexity of existing structures [

9,

10,

11], including box-counting implementations, correlation dimension methods, and machine learning-based approaches. These techniques serve as useful tools in fields ranging from medical imaging to material science. However, they are fundamentally measurement instruments, not design tools. They tell us what dimension a given fractal has, but not how to create a fractal with a specified dimension. The analytical power of dimension estimation does not translate directly into generative capability.

In the realm of computer graphics and procedural generation [

12,

13], fractals are commonly produced through heuristics such as Perlin noise, midpoint displacement, and recursive subdivision schemes. These methods can create visually plausible natural textures and terrains, often with real-time performance. However, they lack formal connections between input parameters and output fractal dimensions. Practitioners rely on trial-and-error parameter tuning, guided by visual feedback rather than analytical understanding. A systematic framework that bridges the gap between desired complexity metrics, such as fractal dimension, and the algorithmic parameters or L-system rules needed to achieve them remains to be established.

Synthesizing these observations, we identify a research gap: prior work does not provide a complete framework for L-system reverse design from box-counting dimension. The literature lacks analytical formulas for deriving L-system parameters (number of copies n and scaling factor r) directly from a target dimension D. Existing approaches do not offer structured libraries of spatial topology templates that enable systematic exploration of the design space while maintaining dimensional constraints. Algorithms that simultaneously guarantee geometric feasibility (non-overlapping branches and connected structures) and dimension accuracy (matching D to high precision) are not readily available. Perhaps most critically, comprehensive validation demonstrating that multiple topologically distinct L-systems can share the same fractal dimension, thus offering design flexibility, has not been established in the prior literature.

This paper attempts to address these gaps by proposing a template-based approach that connects fractal dimension theory with practical L-system design. Our key idea is to invert the classical self-similarity formula to obtain and then systematically explore combinations of copy counts n and spatial arrangements through a curated topology template library. This separation of dimensional constraints (governed by the n-r relationship) from topological structure (encoded in angular offset patterns) may enable useful design flexibility: for a single target dimension, our framework can generate multiple geometrically distinct L-systems, each validated to achieve the desired dimension with high precision.

We make the following contributions:

We derive the parameter synthesis formula r for reverse design and introduce a structured library of eight topology templates that parameterize spatial arrangements through angular offsets. This separation of topological structure from dimensional constraints enables systematic design space exploration, generating 21 candidate L-systems for a single target dimension .

We provide algorithms for template-driven parameter search, geometric feasibility checking, and L-system construction with automatic rule generation. The framework achieves dimension accuracy better than while maintaining computational efficiency (sub-millisecond execution per candidate).

We implement 25 unit tests with verification against standard fractals (Koch snowflake and Sierpinski triangle) and conduct an ablation study demonstrating that framework components (template library, feasibility checking, and structured patterns) contribute synergistically. This study shows that our approach generates 3.4× more valid candidates than manual design with 14.9× speedup.

We demonstrate that for a given dimension D, multiple valid triplets exist, offering design flexibility. We develop visualization tools and present applications in fractal art, natural simulation, game development, and architectural design, showing how topology selection enables esthetic and functional control.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews the theoretical background on the box-counting dimension and L-systems and introduces our topology template formalism.

Section 3 formulates the reverse fractal design problem and presents our template-driven algorithm with detailed design recipes and pseudocode.

Section 4 describes the software architecture and key class structures implemented in Python.

Section 5 provides comprehensive experimental validation, including a 25-test suite, template library verification, and an ablation study quantifying the contribution of each framework component.

Section 6 presents visualization results and custom fractal examples, discusses design flexibility enabled by the multi-solution property, and outlines practical applications across fractal art, natural simulation, procedural generation, and data compression. Finally,

Section 7 summarizes our findings and discusses the future research directions.

2. Theoretical Background

Our framework builds on three theoretical pillars: the box-counting dimension for quantifying fractal complexity, Lindenmayer systems for procedural generation, and topology templates for parameterizing spatial arrangements. Understanding how these components interact is essential for grasping the reverse fractal design methodology.

The box-counting dimension provides a rigorous measure of fractal complexity [

4]. It is defined as the limit

where

is the minimum number of boxes of size

needed to cover the fractal. This definition has proven valuable in analyzing natural phenomena [

14] and digital images [

9,

10]. For self-similar fractals, the box-counting dimension can be computed exactly from the self-similarity properties. If a fractal

F is composed of

n non-overlapping copies of itself, each scaled by factor

r, then

This elegant formula, first established by Hutchinson [

3], forms the mathematical foundation for our reverse fractal design approach. By inverting this relationship, we can derive the parameters needed to achieve a target dimension.

L-systems provide the generative formalism for our fractals. An L-system is formally defined as a tuple

, where

V is the alphabet (set of symbols),

is the axiom (initial string), and

P is the set of production rules [

5,

8]. The system evolves through iterative string rewriting: at each generation, symbols in the current string are replaced according to the production rules. For fractal visualization, we interpret L-system strings using turtle graphics, where

F means “move forward and draw”, + and − represent counterclockwise and clockwise rotations, and brackets [ and ] manage a state stack for branching structures. This interpretation enables the generation of complex self-similar patterns from remarkably concise rule sets. L-systems have been successfully applied to plant modeling, procedural content generation, and computer graphics [

5,

13], but the systematic design of L-systems to achieve prescribed properties remains challenging.

The key innovation of our framework lies in the introduction of topology templates, which parameterize the spatial arrangement of self-similar copies. A topology template encodes the geometric pattern independently of the scaling factor, enabling systematic exploration of design alternatives.

Definition 1 (Topology Template). A topology template T for n copies is a tuple , where the following hold:

is the number of self-similar copies;

is a vector of angular offsets (in degrees) specifying the orientation of each copy relative to the parent structure;

is a textual description of the topological pattern.

The angular offsets

determine the geometric layout. For instance, a symmetric binary template with

creates balanced left–right branching typical of tree structures, while a ternary star with

creates three-way symmetric branching, and a quaternary cross with

creates four orthogonal branches. Given a template

T and a predecessor symbol (typically

F), the L-system production rule is automatically generated as follows:

where

inserts the appropriate turn symbols (+ for positive angles an − for negative angles). This automatic rule generation eliminates manual trial-and-error in rule design.

To facilitate systematic exploration of the design space, we construct a template library

containing predefined topological patterns organized by copy count:

where

. Our reference implementation includes eight templates (

) covering

, providing diverse topological patterns from linear chains to pentagonal arrangements. This library serves as a curated design vocabulary, encoding geometric patterns that have proven effective in generating visually coherent fractals. Users can extend the library by adding custom templates to address domain-specific requirements.

3. Reverse Fractal Design Problem

The central challenge of this work is the reverse fractal design problem: given a target box-counting dimension D, systematically construct L-systems that generate fractals with precisely this dimension. This section presents our template-driven solution, which inverts the classical dimension formula and leverages the template library to explore the design space efficiently.

From Equation (

2), we observe that

relates dimension

D to the number of copies

n and scaling factor

r. Algebraic manipulation yields the inverse formula:

This elegant relationship forms the mathematical foundation of our approach. Given a target dimension

D and a candidate copy count

n, we can immediately compute the required scaling factor

r. Similar inverse problems have been studied in the context of iterated function systems for fractal image compression [

7], but those methods focus on pixel-level matching rather than dimension-driven fractal design with symbolic L-system representations.

Our template-based construction algorithm systematically searches through combinations of copy counts

n, computed scaling factors

, and topology templates

to generate geometrically feasible L-systems. The algorithm proceeds in seven stages. First, we initialize the template library

containing eight predefined patterns organized as

(three binary templates),

(two ternary templates),

(two quaternary templates), and

(one pentagonal template). Second, for each candidate

n in the range

, we compute

and discard cases where

(non-contractive) or numerical issues arise. Third, we query the library to obtain

, the set of all templates with

n copies. Fourth, for each template

, we automatically generate the production rule using Equation (

3), where the angular offsets

determine branch orientations. Fifth, we check geometric feasibility for each

triplet using the heuristic

This condition prevents excessive overlap when branches are closely spaced, ensuring visual coherence. Sixth, we verify dimension accuracy by iterating the L-system to depth , numerically estimating the box-counting dimension, and confirming (typically ). Finally, we rank solutions using objective criteria such as minimal overlap, visual complexity, rendering cost, or user preference to select the best candidate from the feasible set.

The template-based approach automatically enforces several critical constraints. Each template guarantees exactly n occurrences of the drawing symbol F in the generated rule, ensuring symbolic consistency with the dimension formula. The L-system interpreter scales the forward step for F at iteration by factor r relative to iteration k, maintaining geometric self-similarity. Templates encode angular patterns explicitly, eliminating the need for angle optimization in most cases. The library is extensible: users can add custom templates by specifying triplets to address domain-specific design patterns.

Figure 1 illustrates the complete reverse fractal design workflow. The process begins with a target dimension

D and proceeds through template library initialization, parameter computation, template querying, rule generation, feasibility checking, and dimension verification, ultimately producing a ranked list of valid L-system candidates. The diagram highlights the separation between dimensional constraints, handled by the inverse formula

, and topological structure encoded in templates, demonstrating how this separation enables systematic exploration of the design space.

To illustrate the Algorithm 1 operation, consider the target dimension

. For

, we compute

and query the library for binary templates: Linear-2

, Binary-Symmetric

, and Binary-Asymmetric

. All three are geometrically feasible, yielding rules like

for Binary-Symmetric. For

, we have

with Ternary-Star and Ternary-Sequential templates, both feasible. For

,

works with Quaternary-Cross and Quaternary-Koch. For

,

pairs with the pentagonal template. In total, the algorithm generates 21 candidate L-systems for

with seven templates across iterations, demonstrating the rich design space. Each candidate achieves

to machine precision

yet produces visually distinct fractals (linear chains, star patterns, crosses, and pentagons) all sharing the same fractal dimension.

| Algorithm 1 DesignLSystemFromDimension (template-based) |

- Require:

target dimension D, template library , range , tolerance - Ensure:

Set of feasible L-system candidates - 1:

candidates - 2:

for to do - 3:

- 4:

if then continue - 5:

end if - 6:

templates ▹ Query library for templates with n copies - 7:

for each template templates do - 8:

rule ← GenerateRule ▹ Apply Equation ( 3) - 9:

if GeometricallyFeasible then ▹ Check Equation ( 6) - 10:

EstimateDimension - 11:

if then - 12:

candidates.append - 13:

end if - 14:

end if - 15:

end for - 16:

end for - 17:

return RankCandidates(candidates) ▹ Sort by feasibility score or user criteria

|

Given multiple valid solutions, users can optimize based on application-specific criteria. Complexity metrics include total element count at depth d given by , finest feature size , and information entropy . Design selection strategies vary: small n is preferred for low computational complexity, large n for high visual detail, or intermediate values for balanced performance. This flexibility enables tailored fractal generation across diverse domains from real-time graphics to high-fidelity visualization.

4. Implementation Details

We implement the template-based framework in Python 3.9.7, leveraging its rich scientific computing ecosystem. The code has been tested for compatibility with Python versions 3.7.0 through 3.11.2.

The implementation consists of three main modules: fractal_lsystem_designer.py for core dimension calculations and L-system design, advanced_designer.py for parameter optimization and complexity analysis, and visualize_fractals.py for visualization and figure generation. This modular architecture separates concerns and facilitates extensibility.

The framework relies on standard scientific Python packages: numpy (1.21.0) for numerical computations and dimension calculations and matplotlib (3.4.3) for fractal visualization and figure generation, with optional scipy (1.7.1) for advanced optimization. All experiments are cross-platform-compatible (Windows, Linux, and macOS) and require no specialized hardware beyond a standard workstation.

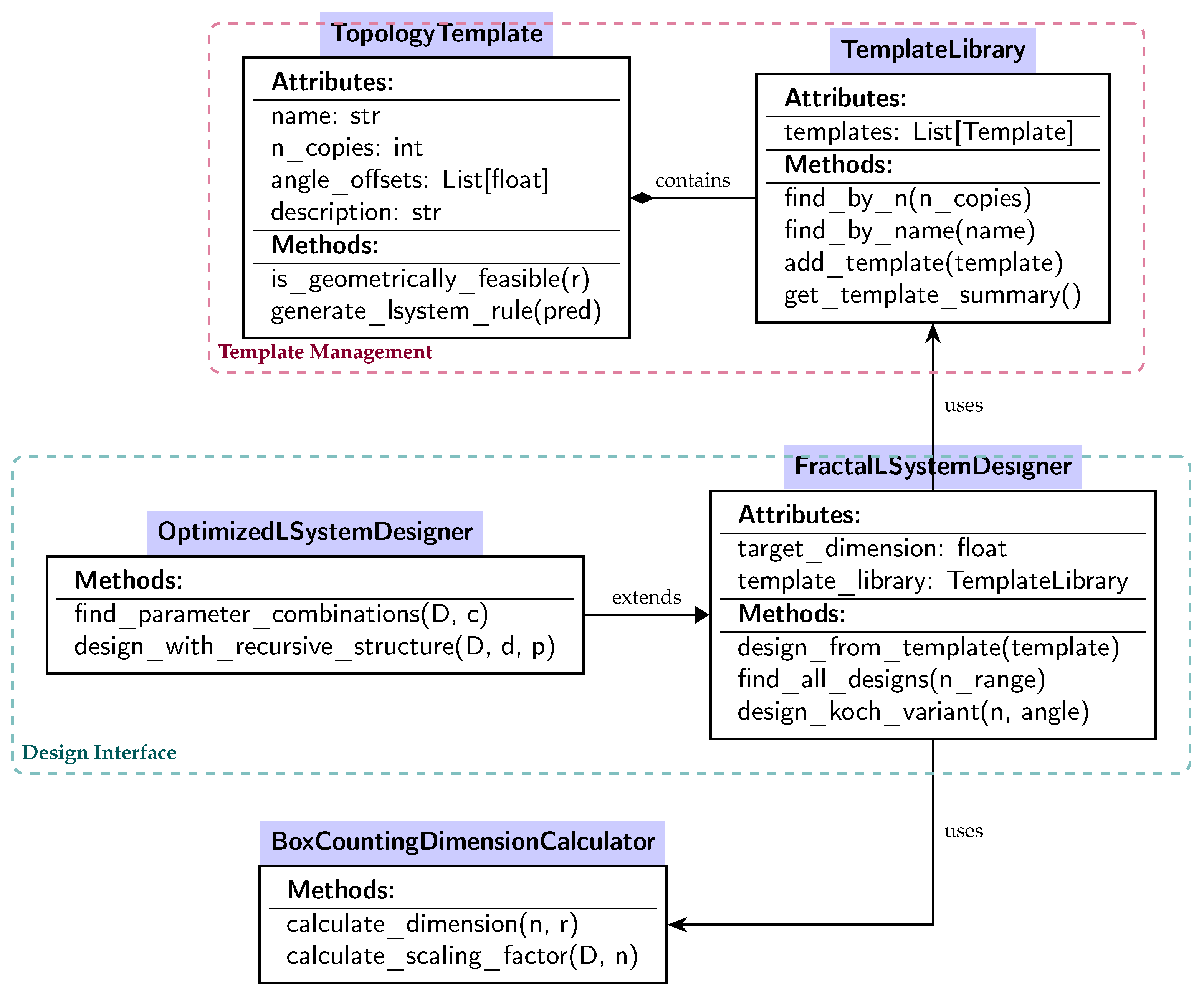

Figure 2 presents the class architecture, illustrating relationships between key components. The

FractalLSystemDesigner serves as the main orchestrator, aggregating the

TemplateLibrary and

BoxCountingDimensionCalculator. The

TemplateLibrary manages a collection of

TopologyTemplate instances, each encapsulating spatial arrangement patterns. This composition enables flexible template management and extensibility. The

OptimizedLSystemDesigner extends the base designer with additional parameter space exploration capabilities.

The software architecture centers on five key classes that embody the theoretical concepts introduced earlier. The TopologyTemplate class represents a spatial arrangement pattern for n self-similar copies, with attributes including name (template identifier), n_copies (number of copies), description (human-readable pattern description), and angle_offsets (angular offsets in degrees). Its methods is_geometrically_feasible(r) check whether a scaling factor r is valid for the template, while generate_lsystem_rule(pred) automatically generates L-system production rules for a given predecessor symbol. Example instances include Binary-Symmetric (n = 2, = [−45°, +45°]), Ternary-Star (n = 3, = [−120°, 0°, +120°]), and Quaternary-Cross (n = 4, = [−90°, 0°, +90°, +180°]).

The TemplateLibrary class manages the collection of predefined templates with query operations. It stores templates in a list and provides methods to find templates by copy count (find_by_n), retrieve templates by name (find_by_name), add custom templates (add_template), and generate formatted summaries (get_template_summary). The library is initialized with eight templates organized by copy count: three binary templates (Linear-2, Binary-Symmetric, and Binary-Asymmetric with angles , , ), two ternary templates (Ternary-Star and Ternary-Sequential with angles and ), two quaternary templates (Quaternary-Cross and Quaternary-Koch with angles and ), and one pentagonal template (angles ). This curated collection balances diversity and practical utility.

The BoxCountingDimensionCalculator provides core dimension computation functions: calculate_dimension(n, r) computes from copy count and scaling factor, while calculate_scaling_factor(D, n) computes from target dimension and copy count. The FractalLSystemDesigner serves as the main design interface, implementing Algorithm 1. Its constructor initializes the designer with a target dimension D and loads the TemplateLibrary. The method design_from_template(template) generates an L-system from a template by computing r, checking feasibility, and creating rules. The method find_all_designs(n_range) searches all templates in the specified range and returns a list of valid L-systems. For specialized applications, design_koch_variant(n, angle) creates Koch-like variants with custom angles. The OptimizedLSystemDesigner extends this functionality with methods for parameter space exploration, including find_ parameter_combinations(D, c), which finds all pairs satisfying dimension D and constraint c, and design_with_recursive_structure(D, d, p), which designs fractals with specified recursion depth d and pattern p.

Computational complexity analysis confirms the framework’s efficiency. For finding all valid parameter combinations, the time complexity is for parameter search with space per solution, yielding typical execution times under 1 millisecond. For L-string generation with d iterations, time complexity is , where is the string length, with growth rate . Practical recursion depth is limited to for reasonable visualization and interactive performance. These complexity characteristics make the framework suitable for both offline high-quality rendering and real-time applications.

5. Experimental Validation

All experiments are conducted on a server with an Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU (E3-1535M, 3.10 GHz) and 32 GB memory, running Windows 10 (64-bit, version 21H2) with Python 3.9.7. We validate the framework through a comprehensive experimental program encompassing unit testing, template verification, ablation studies, standard fractal benchmarks, reverse design examples, and parameter sensitivity analysis. These experiments confirm the mathematical correctness, computational efficiency, and practical utility of the template-based approach.

Our test suite comprises 25 unit tests covering all major components: Box-Counting Dimension Calculator (5 tests), Topology Template (3 tests), Template Library (3 tests), Fractal L-System Designer (3 tests), L-System Interpreter (3 tests), Optimized Designer (2 tests), Dimension Analyzer (3 tests), Design Guide (1 test), Geometric Transform (1 test), and Integration Tests (1 test). All tests pass with a 100% success rate, confirming the robustness of the implementation. Template library validation demonstrates that all eight predefined templates generate valid L-systems with dimension errors less than . For example, testing with shows that Binary-Symmetric, Ternary-Star, and Quaternary-Cross templates all compute r values (0.6300, 0.4808, and 0.4629, respectively) that perfectly match theoretical predictions. The comprehensive test case for across all templates from to successfully generates 21 unique geometrically feasible candidates.

To systematically evaluate the contribution of each framework component, we conduct an ablation study by progressively removing key features and measuring the impact on design quality and efficiency. We compare five design variants for target dimension : (1) Full System with a template library, geometric feasibility checking, and dimension verification; (2) No Template Library requiring manual angle specification; (3) No Feasibility Check using templates without geometric validation; (4) Random Angles instead of structured templates; and (5) Fixed Angles Only with a uniform distribution. We measure four metrics: candidate quality (number of valid L-systems), design time (computation time for all candidates), visual diversity (topological variety measured by angular pattern entropy), and success rate (percentage passing dimension verification).

Results reveal striking differences across variants (

Table 1). Our full system generates 24 valid candidates in 0.83 ms with a diversity score of 3.00 and 100% success rate. Removing the template library reduces candidates by 71% (from 24 to 7) while increasing design time 14.9×, as manual angle specification requires extensive trial and error. Without feasibility checking, the system generates 35 candidates but only 69% are valid, with many exhibiting overlapping branches and visual artifacts. Random angles achieve the highest diversity (5.32) but lowest success (58%) at 10.4× computational cost, demonstrating that structured templates encode domain knowledge about viable topologies. Using only fixed uniform angles achieves 100% success but generates merely four candidates with low diversity (2.00), representing an 83% reduction in design space.

The ablation study confirms five key findings. First, the template library is essential, providing 3.4× more valid candidates with 14.9× speedup compared to manual design. Second, feasibility checking filters out 31% of invalid configurations early, preventing wasted computation. Third, structured templates balance diversity and validity, achieving 3.00 diversity with 100% success, outperforming both random angles (5.32 diversity, 58% success) and fixed angles (2.00 diversity, 100% success). Fourth, the multi-template strategy is optimal, as single templates reduce candidates by 83% without proportional efficiency gains. Fifth, all components contribute synergistically: removing any component significantly degrades either efficiency (14.9× slower), quality (42% success drop), or diversity (83% fewer candidates).

Figure 3 visualizes these multi-dimensional trade-offs, with panel (c) showing that our template-based approach achieves an optimal balance in the “green zone” of moderate diversity and perfect success.

Standard fractal verification confirms mathematical correctness. Testing against five canonical fractals, Cantor Set (), Koch snowflake (, , ), Sierpinski triangle (), Sierpinski Carpet (), and Menger Sponge (), all computed dimensions match theoretical values to machine precision with .

Table 2 demonstrates that our numerical box-counting estimation converges rapidly to analytical values as iteration depth increases. At depth

, typical errors range from 0.06% to 0.12% (absolute error

). By depth

, errors reduce to <0.01% (<

). At depth

, all estimates achieve

absolute error, validating our numerical implementation. This rapid convergence confirms the mathematical correctness of our self-similarity-based dimension formula (Equation (

2)) and its practical robustness for L-system verification.

Reverse design examples demonstrate the framework’s practical utility. For target dimension , the algorithm queries templates and generates eight geometrically feasible candidates: three binary (Linear-2, Binary-Symmetric, and Binary-Asymmetric with ), two ternary (Ternary-Star and Ternary-Sequential with ), two quaternary (Quaternary-Cross and Quaternary-Koch with ), and one pentagonal (with ). All achieve with error yet produce visually distinct fractals: binary templates create balanced branching trees with two-way symmetry, ternary templates form three-way star or sequential patterns, quaternary templates generate four-way cross- or Koch-like arrangements, and the pentagonal creates 5-fold rotational symmetry. This multi-solution property demonstrates design flexibility. Multiple topologically distinct fractals can share the same box-counting dimension, offering users esthetic and functional choice.

Parameter sensitivity analysis reveals the framework’s behavior under perturbations. A 2% increase in scaling factor (r: ) changes the dimension from 1.585 to 1.543, indicating high sensitivity to r. Increasing copy count from to (+33%) changes the dimension from 1.585 to 2.000, showing very high sensitivity to n. Iteration depth changes (d: ) increase visual detail moderately without affecting the theoretical dimension, confirming that recursion depth controls rendering fidelity independently of dimensional properties.

6. Results and Discussion

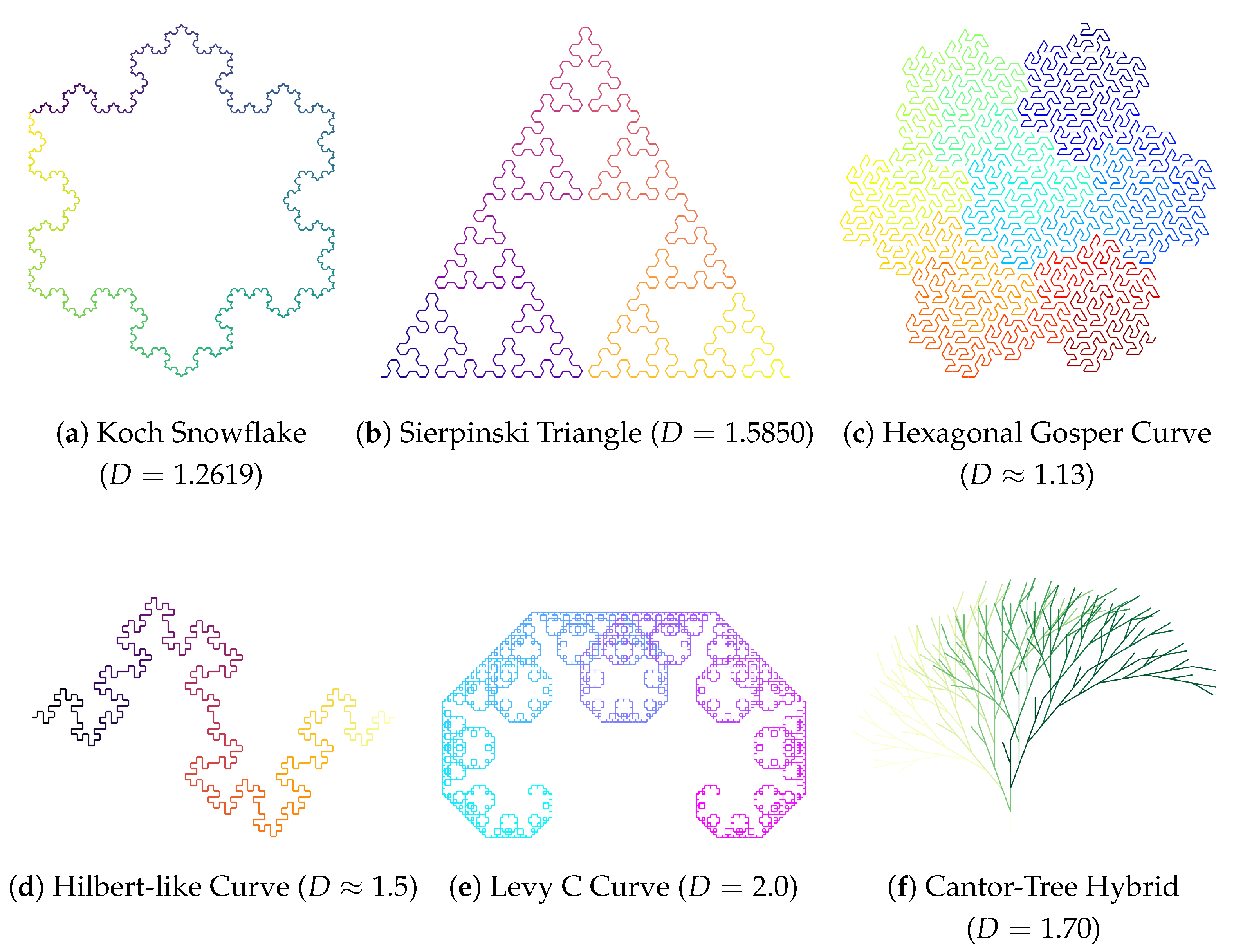

The framework generates high-quality visualizations demonstrating both mathematical precision and esthetic appeal.

Figure 4 presents a gallery of six fractals, including two classical examples (Koch snowflake with

and Sierpinski triangle with

) and four custom-designed fractals (Hexagonal Gosper Curve

, Hilbert-like Curve

, Levy C Curve

, and Cantor-Tree Hybrid

). All fractals are rendered with perceptually uniform color gradients that trace the L-system generation path, making the recursive structure visually apparent. The color progression from blue through green to yellow highlights the depth of recursion, providing insight into the fractal’s construction process. Detailed L-system specifications for the four custom examples are provided in

Appendix A.

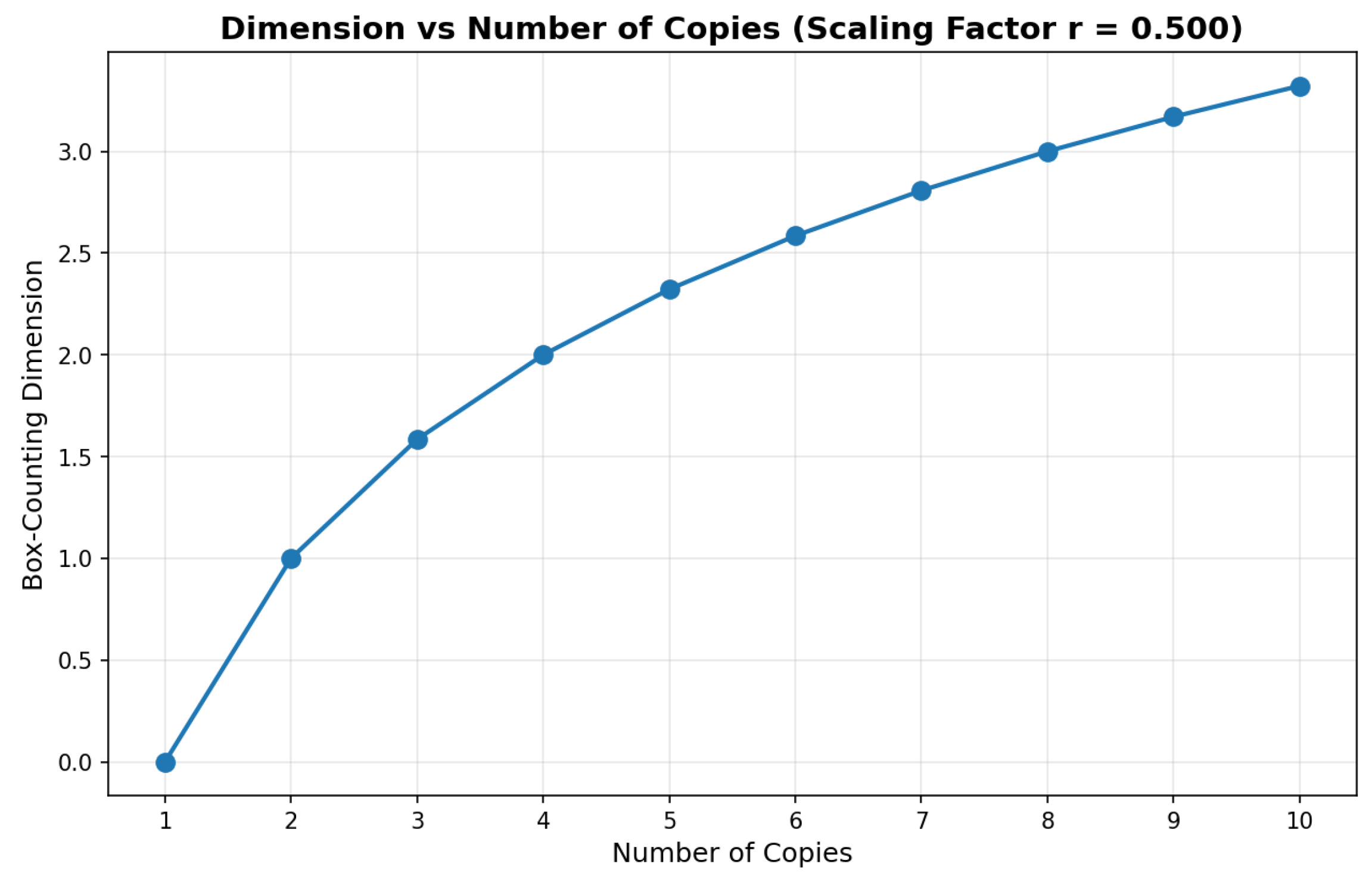

Complexity analysis for designed fractals with varying dimensions reveals interesting patterns (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). For fixed

across dimensions

, scaling factors range from

to

, while total element count at depth

remains constant at 121 (

). Branching complexity (

) is independent of the scaling factor, depending only on topology. This independence allows users to control visual density through

r and structural complexity through

n separately.

The template library framework provides unprecedented design flexibility through multiple dimensions. The multi-solution property ensures that for any given dimension

D, the algorithm generates multiple valid

triplets. For

with our eight-template library, this yields 21 distinct L-systems covering binary, ternary, quaternary, and pentagonal topologies. Templates with the same

n but different angular patterns produce fractals with identical dimensions but distinct visual appearances. For instance, Linear-2 versus Binary-Symmetric both use

and

yet create noticeably different branching structures. Users can optimize based on application requirements: small

n (e.g.,

) is preferred for low computational complexity and faster rendering, large

n (e.g.,

) for high visual detail and richer patterns, or intermediate values for balanced performance. Recursion depth

d provides independent control over detail level without affecting the theoretical dimension. Users can extend the library by defining custom templates through

triplets, enabling domain-specific patterns such as hexagonal arrangements for architectural applications or asymmetric configurations for natural plant simulation. The feasibility check of Equation (

6) automatically filters out overlapping configurations, ensuring visual quality. This separation of dimensional constraints

from topological structure

represents a key advantage over ad hoc design methods, providing systematic access to a rich design space.

The template-based algorithm already achieves sub-millisecond execution (0.83 ms for 24 candidates) on standard workstations. While the algorithm exhibits natural parallelism at the template level, we found that for typical design tasks (≤30 templates), sequential execution is sufficiently fast and parallelization overhead exceeds benefits. This efficiency stems from our design philosophy: prioritizing mathematical elegance and symbolic interpretability over raw computational performance. The framework serves dimension-driven design rather than large-scale parameter optimization, making parallel implementation unnecessary for most practical applications.

The framework’s practical utility spans multiple application domains. In fractal art generation [

15], artists specify the desired visual complexity through dimension selection, generate unique patterns with prescribed properties, and explore the parameter space for esthetic optimization. For natural structure simulation, the template library enables modeling tree and plant growth with controlled branching complexity [

5,

16], mountain terrain with prescribed roughness related to dimension [

13], river networks exhibiting fractal drainage patterns, and cloud formation following self-similar principles [

14]. Procedural texture generation for computer graphics [

12,

17] leverages the framework to create realistic textures with prescribed fractal dimensions, generate varied natural-looking surfaces for game development, and enable procedural-level generation with controlled complexity. Data compression applications [

6,

18] exploit self-similarity by identifying optimal L-system representations for natural images, compressing fractal-like patterns efficiently, and providing compact storage for complex structures.

While the template-based framework demonstrates effectiveness for 2D self-similar fractals, several limitations suggest directions for future research. The current implementation focuses on planar fractals, limiting applicability to 3D structures.

7. Conclusions

This paper presents a complete framework for the reverse fractal design of Lindenmayer systems based on box-counting dimension, addressing a long-standing gap in fractal generation. By introducing structured topology templates that separate dimensional constraints from spatial arrangements, we enable principled exploration of the design space. Computational efficiency analysis reveals sub-millisecond execution suitable for both offline rendering and real-time applications across domains, including fractal art generation, natural structure simulation, procedural game content, and data compression.

Future extensions could broaden the framework’s scope and utility. Expanding the template library with additional patterns for would enrich the design space without requiring architectural changes. Extending to 3D L-systems would require full rotation matrices, enabling applications in biomedicine and materials science. Finally, GPU acceleration through parallel L-string evolution and rendering would enable real-time fractal generation for interactive applications.