Abstract

Deep learning for semantic segmentation has made significant advances in recent years, achieving state-of-the-art performance. Medical image segmentation, as a key component of healthcare systems, plays a vital role in the diagnosis and treatment planning of diseases. Due to the fractal and scale-invariant nature of biological structures, effective medical image segmentation requires models capable of capturing hierarchical and self-similar representations across multiple spatial scales. In this paper, a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) is explored within the Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and Vision Transformer (ViT)-based hybrid U-shape network, named RCV-UNet. First, the ViT-based layer was developed in the bottleneck to effectively capture the global context of an image and establish long-range dependencies through the self-attention mechanism. Second, recurrent residual convolutional blocks (RRCBs) were introduced in both the encoder and decoder to enhance the ability to capture local features and preserve fine details. Third, by integrating the global feature extraction capability of ViT with the local feature enhancement strength of RRCBs, RCV-UNet achieved promising global consistency and boundary refinement, addressing key challenges in medical image segmentation. From a fractal–fractional perspective, the multi-scale encoder–decoder hierarchy and attention-driven aggregation in RCV-UNet naturally accommodate fractal-like, scale-invariant regularity, while the recurrent and residual connections approximate fractional-order dynamics in feature propagation, enabling continuous and memory-aware representation learning. The proposed RCV-UNet was evaluated on four different modalities of images, including CT, MRI, Dermoscopy, and ultrasound, using the Synapse, ACDC, ISIC 2018, and BUSI datasets. Experimental results demonstrate that RCV-UNet outperforms other popular baseline methods, achieving strong performance across different segmentation tasks. The code of the proposed method will be made publicly available.

1. Introduction

Medical image segmentation is a critical and challenging task that assists clinicians in rapidly identifying pixel-level pathological regions and extracting essential information from medical images, thereby enabling more accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. Medical images obtained from modalities such as MRI, ultrasound, CT, X-ray, and microscopy provide structural and functional information about tumors, lesions, and injuries. These imaging data are essential for clinical decision-making in the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular conditions, and neurological disorders [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Traditionally, medical image analysis relies on manual analysis performed by medical experts, which is time-consuming and prone to subjective bias. Since many biological structures in medical images exhibit fractal-like, self-similar, and hierarchically complex patterns [7,8], traditional feature-based approaches often struggle to model such intricate geometries. As a result, modern medical image analysis increasingly employs automated and data-driven techniques to enhance accuracy and robustness [9,10]. Among these techniques, computer-aided diagnosis, a key component of clinical practice, relies heavily on image segmentation to automatically identify and extract critical regions in medical images, thereby improving diagnostic and therapeutic outcomes.

Early segmentation algorithms, such as Canny [11], relied heavily on handcrafted features designed by experts. To better represent the irregular and self-similar nature of anatomical structures, fractal theory has been introduced into medical image segmentation. Fractional-order-level set methods have been used to model multi-scale structures in medical images, improving boundary accuracy and noise robustness [12]. Methods combining multi-fractal analysis with partial differential equation frameworks improve robustness to noise and texture irregularities [13], while fractal-geometry-guided and Bayesian multi-fractal models further quantify hierarchical complexity and enable probabilistic delineation of pathological regions [14,15]. Extending the fractal perspective to the foundation-model era, VG-SAM exploits self-similarity and hierarchical representations to achieve universal medical image segmentation [16]. With the advent of machine learning, CNNs gained prominence for their superior feature extraction and representation capabilities. Unlike traditional methods, CNN-based methods do not require manual feature engineering or extensive preprocessing, making them widely adopted for medical image segmentation. CNN-based networks have achieved remarkable success in medical image analysis and computer-aided diagnosis. Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) [17] introduced a groundbreaking approach by replacing fully connected layers with convolutional layers and employing up-sampling for pixel-level segmentation. Building on FCNs, Ronneberger et al. [18] developed U-Net, a network specifically designed for medical image segmentation. U-Net introduced a more sophisticated encoder–decoder structure with skip connections, enabling simultaneous capture of local features and global context, thereby improving segmentation accuracy. Due to its exceptional performance, U-Net has become one of the most widely used networks for medical image segmentation [3,19,20,21,22]. Subsequent studies proposed numerous variants to enhance U-Net. For example, Milletari et al. [23] proposed V-Net, which introduced the Dice loss function instead of traditional cross-entropy and utilized 3D convolutional kernels. UNet++ [24] employed a nested structure with dense skip connections to improve boundary details and small-target segmentation. UNet3+ [25] further enhanced performance with full-scale skip connections, deep supervision, and lightweight design. Attention U-Net [26] incorporated attention gates to dynamically filter skip-connected features, amplifying the representation of target regions. Inspired by residual connections, ResUNet [27] replaced standard convolution blocks with residual modules.

However, these CNN-based methods are inherently constrained by their local receptive fields, limiting their capacity to model global features and dynamically adapt to multi-modal data. The emergence of Transformers has helped address these constraints by facilitating long-range dependency modeling. Dosovitskiy et al. [28] first introduced ViTs for image classification, reinterpreting images as token sequences via patch embeddings to achieve global feature modeling for various vision tasks. Later, window-based self-attention techniques were adopted in networks like SwinUNet [29], which reduce computational overhead and capture cross-window relationships through shifted window attention. Moreover, UNETR [30] targets 3D volumetric segmentation by employing a pure ViT encoder to model long-range dependencies in tokenized 3D inputs and connecting them to a U-shaped decoder through multi-resolution skip connections to recover fine spatial details. Nonetheless, classical Transformers lack inherent inductive biases and can be less effective for small-scale medical datasets. Their relatively weak local feature extraction also makes them suboptimal for small-target segmentation and precise boundary refinement.

Driven by these shortcomings, researchers have explored hybrid architectures that integrate CNNs and Transformers to combine local feature modeling with global context modeling. For example, TransUNet [31] utilizes a Transformer backbone within the U-Net encoder, while UTNet [32] introduces hybrid attention modules in both the encoder and decoder. Similarly, MISSFormer [33], UCTransNet [34], and MedT [35] adopt lightweight or axial attention blocks to enhance segmentation performance without dramatically increasing computational complexity. Beyond these architectures, LeViT-UNet [36] incorporates the LeViT Transformer to achieve fast, low-latency inference suitable for medical segmentation; MT-UNet [37] enriches multi-scale feature learning through multi-token Transformer blocks, improving robustness to anatomical variations; and BRAU-Net++ [38] integrates bi-level routing attention into a hierarchical U-shaped architecture to efficiently capture global context with lower computational cost. However, the global attention mechanism of Transformers alone is often insufficient for capturing fine-grained local features, leading to suboptimal performance in small-target detection and boundary refinement. To address this limitation, Alom et al. [39] proposed Recurrent Residual Convolutional Neural Network (RRCNN), which integrates recurrent neural networks, residual connections, and convolutional layers to iteratively refine feature representations while preserving original feature information. This design strengthens local feature extraction, enabling detailed segmentation of small targets and improving boundary delineation.

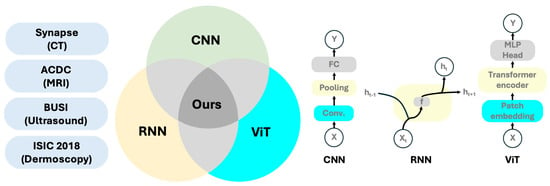

Recent advances in medical image segmentation have led to substantial progress, with CNN- and ViT-based hybrid networks achieving impressive performance. However, a key challenge lies in effectively integrating different architectures to fully exploit their respective advantages. To address this, we propose a novel hybrid segmentation network that seamlessly integrates RNNs, CNNs, and ViTs. The existing studies of different neural network architecture for medical image segmentation and ours are summarized in Table 1. From a fractal–fractional perspective, the proposed architecture embodies both hierarchical self-similarity and memory-dependent dynamics. The multi-scale encoder–decoder hierarchy and attention-driven aggregation naturally accommodate the self-similar and hierarchical patterns observed in anatomical structures, while the recurrent and residual connections approximate fractional-order dynamics in the feature propagation process. The main contributions are highlighted in Figure 1 and listed as follows:

Table 1.

Summary of related work by architecture family and key highlights.

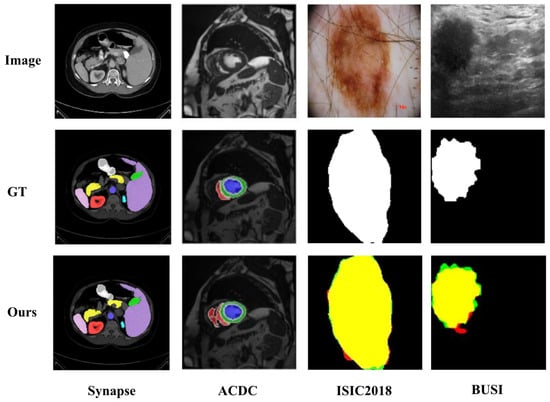

Figure 1.

A brief introduction to our method and the datasets employed.

- We integrate RNNs, CNNs, and residual connections to construct network blocks, named RRCBs, thereby enhancing the network’s ability to extract multi-level and local features;

- We introduce a ViT-based module at the bottleneck, which enhances global context modeling and enables the network to capture long-range dependencies;

- We unify RNNs, CNNs, and ViTs within an encoder–bottleneck–decoder U-Net architecture, exploiting their complementary advantages and systematically analyzing how ViT placement in the encoder, decoder, or bottleneck affects model performance;

- RCV-UNet was evaluated on four medical imaging datasets across multiple modalities, achieving superior segmentation performance on large complex targets, fine-grained small structures, and challenging boundary regions.

2. Approach

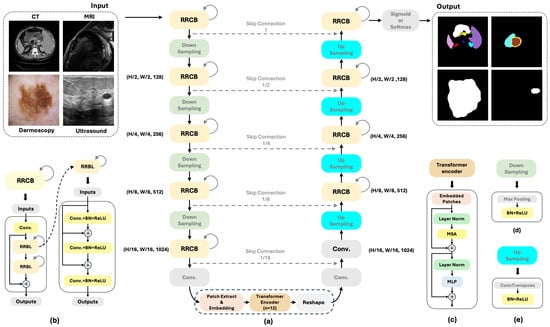

Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of RCV-UNet. For an image , where H, W, and C represent the image height, width, and number of channels (e.g., 1 for grayscale images and 3 for RGB images) respectively, our goal is to predict the corresponding mask , where K denotes the number of classes (e.g., 1 for binary segmentation and more for multi-class segmentation). The segmentation network, parameterized by , processes the input to produce the predicted segmentation mask . The training process starts with a given dataset and aims to minimize a loss function , such as the Dice coefficient loss, which quantifies the discrepancy between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth . During training, the network parameters are iteratively adjusted using optimization techniques to reduce the loss and enhance segmentation performance. Then, the network is evaluated on a test set by comparing with using various evaluation metrics.

Figure 2.

(a) Overview of the proposed RCV-UNet Framework; (b) Schematic of an RRCB with a recurrent iteration number of 2, and a schematic of an RRCL with a layer number of 2; (c) Schematic of the Transformer encoder; (d) Schematic of down-sampling; (e) Schematic of up-sampling.

The fundamental framework of the U-shaped structure is to encode the original image to extract high-level features, decode it to gradually restore the spatial resolution, and combine the features from the encoder through skip connections to achieve precise pixel-level predictions [18]. In our method, standard convolutional operations are replaced with RRCBs in both the encoder and decoder, and a ViT block is introduced at the encoder bottleneck. We will present these two blocks individually, followed by an explanation of how they are integrated into the U-Net framework.

2.1. When RNN Meets CNN: Recurrent Residual Convolution Block as an Encoder and Decoder

RNN [43] is a classic neural network architecture designed for processing sequential data. In 2015, Liang and Hu [44] explored the integration of RNNs and CNNs and proposed Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network (RCNN), which applies RNNs to features extracted by CNNs. By leveraging the memory mechanism of RNNs, RCNN enables recursive modeling of spatial and contextual information in images. Subsequently, IRCNN [45] extended this idea by integrating the Inception module and RNNs for object recognition tasks. Inspired by ResNet [46], ResUNet [27] incorporated the residual learning framework into the encoder–decoder structure of U-Net [18], enhancing feature extraction capabilities and alleviating optimization challenges in deep networks. Building on these developments, Alom et al. [39] proposed R2U-Net, which employs recurrent residual blocks to enhance feature extraction and contextual modeling. This architecture is particularly effective for small-object segmentation and boundary refinement tasks.

In this work, we adopt RRCBs, with the number of layers set to 2, and the number of recurrent iterations set to 2, motivated by prior work, such as R2U-Net [39]. This means that each RRCB contains two Recurrent Residual Convolutional Layers (RRCLs), and for each layer, two iterations of recurrent convolution operations are performed. Let denote the input sample in the layer of the RRCNN block. represents the recurrent residual convolutional block, represents the convolution operation, represents the Recurrent Residual Convolutional Layer, and represents the convolution, Batch Normalization, and ReLU activation operations. As illustrated in Figure 2b, which provides the detailed structure of an RRCB module, the output can be expressed as follows:

At the very beginning of the block, we employ a convolution to enhance the interaction between channels and capture higher-dimensional feature relationships. Additionally, the RRCB enables feature accumulation, which helps extract very low-level features. The introduction of residual connections also alleviates vanishing gradients and network degradation during deep neural network training, thereby facilitating more effective feature learning. As shown in Figure 2a, both the encoder and decoder contain five RRCBs arranged symmetrically. Each RRCB uses a convolution kernel size of 3, with the number of filters increasing from shallow to deep layers as 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024, respectively, while the decoder mirrors the same configuration.

Intuitively, RRCBs can be loosely associated with concepts from fractional-order dynamics, which model nonlocality and memory effects in complex systems [47,48]. Although this analogy is not mathematically strict, the residual path encourages smooth feature transitions, while the recurrent loop introduces a simple form of memory, echoing long-range dependence observed in stochastic fractional processes such as fractional Brownian motion [49]. This offers an intuitive perspective on why RRCBs may capture both local details and broader structural dependencies.

2.2. When ViT Meets CNN: A Transformer Block as Bottleneck

Transformer, introduced in [50], is a deep learning network that replaces traditional recurrent operations with a fully attention-based architecture. Initially achieving significant success in natural language processing (NLP), Transformer’s strong feature modeling capabilities quickly extended its applications to computer vision. Dosovitskiy et al. [28] proposed ViT, which was the first method to apply Transformer to image classification tasks. ViT divides input images into small patches, flattens them into sequences, encodes them, and feeds them into the Transformer network. To address the limitations of Transformer in small-sample learning and local feature extraction, researchers have developed CNN–Transformer hybrid architectures. For example, Swin Transformer [51] utilizes a local window attention mechanism to enhance local feature modeling and employs a shifted window strategy to capture cross-window relationships. TransUNet [31] incorporates ViT into the encoder and feeds CNN-extracted local features into Transformer, leveraging global modeling to improve the segmentation accuracy of large targets. In this paper, we apply Transformers to vision tasks inspired by ViT [28] and TransUNet [31].

To process 2D images with Transformer, which only operates on 1D token sequences, we need to reshape the image into a sequence of flattened 2D patches , where is the resolution of each image patch, and is the number of patches. Then, we perform patch embedding, where a trainable linear projection is used to map the resulting sequence of patches into a D-dimensional space for Transformer processing. Additionally, learnable 1D positional embeddings () are added to the patch embeddings to preserve the spatial positional information of the patches (Equation (4)).

According to Figure 2c, the Transformer encoder consists of the ith in the total number L layers of multi-head self-attention (MSA) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) blocks (Equations (5) and (6)). Here, represents the layer normalization operator, and residual connections are applied after each block. We adopt the commonly used ViT-Base configuration [28]. The encoder contains Transformer layers, each with 12 attention heads, a 3072-dimensional MLP block (expansion ratio = 4), and residual connections with layer normalization. Notably, the preceding encoder has already reduced the spatial resolution to of the original image, so the effective patch size at this stage becomes , and each spatial position is directly mapped to a -dimensional embedding.

Intuitively, the ViT block can be viewed as conceptually reflecting the fractal-like, hierarchical organization of anatomical structures in medical images. While this analogy is conceptual rather than rigorous, the multi-head self-attention mechanism enables the model to relate spatially distant regions and aggregate information across scales, offering an intuitive explanation for its ability to capture both global context and multi-level structural patterns.

2.3. When RNN Meets CNN and ViT: Toward a Hybrid Architecture

To address the need for multi-scale feature extraction and global contextual understanding in medical image segmentation, researchers have been progressively integrating Transformers and RNN modules into the U-Net framework. This approach maintains the ability to extract local features while further enhancing the capture of global dependencies, as well as sequential or structural context [29,30,31]. In terms of leveraging Transformers, TransUNet combines a CNN encoder with ViT, effectively balancing long-range dependency modeling and high-resolution detail retention [31]. Following this, a series of hybrid networks, such as MISSFormer [33], UCTransNet [34], and MedT [35], incorporate lightweight or axial attention mechanisms into the encoder or skip connections of U-Net, aiming to improve segmentation accuracy while minimizing computational overhead. Meanwhile, for applications requiring temporal or structural context, R2U-Net and ConvLSTM-UNet introduce recurrent convolutional operations into U-Net, thereby reinforcing recursive and contextual feature representation and demonstrating strong performance in segmenting complex anatomical structures [39,52]. Overall, these U-Net variants augmented with Transformers or RNN have achieved competitive performance in high-resolution and multi-modal medical image segmentation tasks. To fully exploit the detailed local feature extraction capability of RRCBs and the global feature extraction capability of Transformer, we integrate these components into a U-Net-based network architecture, as shown in Figure 2.

In the U-shaped network, we replace the standard forward convolution layers with RRCBs, which incorporate an effective feature accumulation mechanism. This design enables the network to capture more detailed information, making it particularly advantageous for segmenting small, hard-to-distinguish objects and fine boundaries. After each RRCB, maxpooling, Batch Normalization, and ReLU activation are applied to accelerate convergence, stabilize training, and mitigate vanishing gradient issues.

Following five RRCBs and four maxpooling operations, a convolution is employed along the channel dimension to apply weighting, preparing the features for subsequent attention mechanisms. Patch extraction is performed to convert the 2D data into a 1D sequence suitable for processing by the Transformer. This sequence is then linearly projected into a high-dimensional feature space (D-dimensional) via patch embedding and fed into the Transformer encoder for global feature extraction and fusion.

The output of the Transformer encoder is reshaped back into a 2D feature map, followed by a convolution to restore the spatial resolution of the feature map. Subsequently, the feature map undergoes one convolution and four RRCBs, followed by four Transposed Convolutions to progressively recover the spatial resolution of the image. Finally, a convolution, followed by an activation function (Sigmoid or Softmax), is applied to generate the output mask of the input image.

From a conceptual viewpoint, the hybrid architecture can be broadly interpreted within a fractal–fractional perspective. While this connection is only heuristic, the attention-based global modeling and the recurrent–residual local refinement suggest a complementary interaction between multi-scale structural patterns and memory-like feature propagation. This offers an intuitive explanation for how the network may integrate local detail with broader contextual information in complex medical images.

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Dataset

Synapse Multi-Organ Segmentation Dataset. The Synapse dataset [53] originates from the MICCAI 2015 Beyond the Cranial Vault (BTCV) multi-organ segmentation challenge. It comprises 30 abdominal CT cases, totaling 3779 axial clinical CT slices. Each 3D CT volume contains between 85 and 198 slices, with a spatial resolution of 512 × 512 pixels. Although the original dataset includes annotations for 13 organs, following the protocol of previous works [29,31], we focus on the segmentation of 8 abdominal organs: aorta, gallbladder, left kidney, right kidney, liver, pancreas, spleen, and stomach. For data partitioning, 18 cases are used for training, and the remaining 12 cases for testing, without a separate validation set. Specifically, we extract 2D axial slices from the 18 training volumes, resulting in 2211 2D CT images. The training/testing split is based on a provided .txt file list, consistent with prior studies [29,31].

Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge (ACDC). The ACDC (Automated Cardiac Diagnosis Challenge) dataset [54] is a benchmark specifically designed for cardiac MRI segmentation and diagnosis tasks. It is derived from real clinical examinations conducted at Dijon University Hospital. The dataset consists of 3D short-axis cardiac MRI sequences, along with expert-annotated segmentation masks for key cardiac structures. The label values and their corresponding cardiac regions are as follows: 0 for the background, 1 for the left ventricle (LV), 2 for the right ventricle (RV), and 3 for the myocardium (MYO). The dataset contains data from 150 patients, which have been officially split into 100 patients (1902 axial slices) for training and 50 patients (1076 axial slices) for testing. For each patient, the dataset officially provides keyframe cardiac images at the end-diastolic and end-systolic phases. In our experiments, we further randomly split the 100 training samples into 80 training data (1521 axial slices) and 20 validation data (381 axial slices). To make the 3D volumetric data compatible with deep learning architectures that operate on 2D images, we extracted individual axial slices from each volume.

International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC) 2018 Dataset. The ISIC 2018 dataset [55] was released by the ISIC organization as part of a skin lesion analysis challenge at MICCAI 2018, focusing on the automated processing of dermoscopic images. It contains high-quality clinical images of skin lesions and provides annotations for three tasks: lesion segmentation (Task 1), lesion attribute detection (Task 2), and disease classification (Task 3). In our work, we only used the data from Task 1, which includes 2594 training images, 100 validation images, and 1000 testing images, each accompanied by a binary lesion segmentation mask. These images cover a variety of skin conditions, including melanoma and melanocytic nevus.

Breast Ultrasound Images (BUSI) Dataset. This dataset [56], collected in 2018, consists of breast ultrasound images from 600 female patients aged 25 to 75. The dataset contains a total of 780 images, with an average resolution of 500 × 500 pixels, stored in PNG format. These images are categorized into three classes: normal, benign, and malignant. Ground truth segmentation masks are provided alongside the original images in the dataset. We used 624 images for training and validation with data augmentation, while the remaining 156 images were used for testing.

3.2. Implementation Details

The implementation of our approach was developed using Python 3.8, TensorFlow 2.19 [57], and Keras 3.10.0. Our experiments were conducted on an Intel Xeon CPU with six cores and 39 MB of cache and significantly accelerated with an NVIDIA A100 GPU, equipped with 40 GB of VRAM, which is well-suited for high-performance deep learning tasks. We adapted several networks from established sources, specifically Keras-UNet-Collections (https://github.com/yingkaisha/keras-unet-collection, accessed on 1 October 2025), applying necessary modifications to optimize them for our specific dataset. These adaptations were crucial in handling our dataset’s unique characteristics.

Due to the increased complexity and multi-organ nature of the Synapse dataset, we resized all input images to 224 × 224 and normalized the pixel values to the range [0, 1] when training both the baseline methods and our proposed network. For the ACDC, ISIC 2018, and BUSI datasets, all images were resized to 128 × 128 and normalized to the same range. To enhance the generalization capability of our network and reduce overfitting, we applied four data augmentation techniques—horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, diagonal flipping, and random rotations within the range of [−20°, 20°]. Each transformation was applied with a random probability, allowing different augmentations to be independently combined to generate a more diverse and robust training dataset. The SGD optimization algorithm was employed with a learning rate of 1 × , a momentum of 0.9, and a weight decay of 1 × . For the Synapse dataset, we used Hybrid Loss (7) that equally weights categorical cross-entropy and Dice loss to balance pixel-level accuracy and region-level overlap. For the other three datasets, a simple Dice loss was adopted.

To ensure efficient utilization of computational resources, we adopted a batch size of 16 for all datasets. The training was conducted for 300 epochs on the ACDC dataset and 150 epochs on the Synapse, ISIC 2018, and BUSI datasets. A model checkpoint was employed to automatically monitor the minimum Validation Loss value during training on the ACDC, ISIC 2018, and BUSI datasets, ensuring the best-performing network would be saved. For the Synapse dataset, previous works, such as TransUNet [31] and SwinUNet [29], do not employ a separate validation set, as the training set contains only 18 volumes, and further splitting would significantly reduce the effective training data. Following this common practice, we trained the model for a fixed number of epochs and periodically saved checkpoints, selecting the one that achieved the lowest training loss without exhibiting signs of overfitting. The final evaluation was then performed on the official testing set.

The proposed architecture settings largely follow the widely used configurations of TransUNet and R2U-Net to ensure reproducibility and fair comparison. For the Transformer bottleneck, we adopted a ViT-Base style encoder, as in TransUNet [31]: the embedding dimension is , the number of Transformer layers is , and each layer uses 12 attention heads with an MLP expansion ratio of 4 (hidden dimension 3072). Since the encoder reduces the spatial resolution to of the input, we tokenized the bottleneck feature map into non-overlapping tokens with an effective patch size of (i.e., each spatial location corresponds to one token), and we used learnable positional embeddings. Unless otherwise stated, we followed the default TransUNet-style implementation with LayerNorm and residual connections; dropout was set to 0 in our implementation for stable training on the considered medical datasets.

For the convolutional backbone, we used recurrent residual convolution blocks (RRCBs) following the design philosophy of R2U-Net [39]. Specifically, at each encoder/decoder stage, we set the number of RRCL layers per RRCB to 2 and the recurrent iteration number to 2. Each RRCL consists of a convolution, followed by Batch Normalization and ReLU activation, and a residual connection is applied at the RRCB level. The channel widths follow the standard U-Net pyramid: 64, 128, 256, 512, and 1024, from shallow to deep, and the decoder mirrors the encoder. A convolution is used for channel projection before entering the Transformer and for the final prediction head.

3.3. Baseline Methods

To evaluate the performance of RCV-UNet in medical image segmentation, we conducted an extensive comparison with 10 baseline networks covering diverse architectural designs. To demonstrate the effectiveness of RCV-UNet, we used a ViT block to bridge the encoder and decoder, with comparisons made against classical CNN-based networks and their variants. Furthermore, we evaluated the impact of the encoder–decoder design by contrasting the result with existing hybrid CNN-ViT networks. The compared networks include U-Net [18], V-Net [23], UNet++ [24], UNet3+ [25], ResUNet [27], SwinUNet [29], TransUNet [31], R2U-Net [39], Attention U-Net [26], and -Net [58].

3.4. Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of RCV-UNet, we employed a diverse set of evaluation metrics. These metrics encompass a range of criteria, including the Dice coefficient (Dice), Intersection over Union (IoU), Accuracy (Acc), Precision (Pre), Sensitivity (Sen), and Specificity (Spec). The upward arrows next to each metric in the table indicate that higher values reflect superior performance. Each metric provides a unique perspective on the effectiveness of RCV-UNet in segmenting medical images. The details of our evaluation metrics can be outlined as follows: where represents the number of true positives, denotes the number of true negatives, signifies the number of false positives, and stands for the number of false negatives.

3.5. Qualitative Results

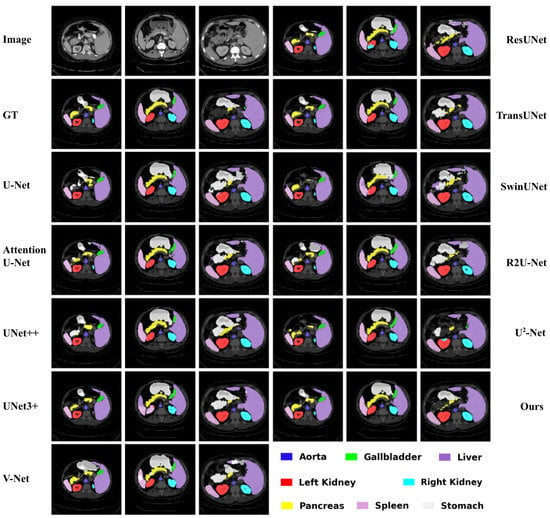

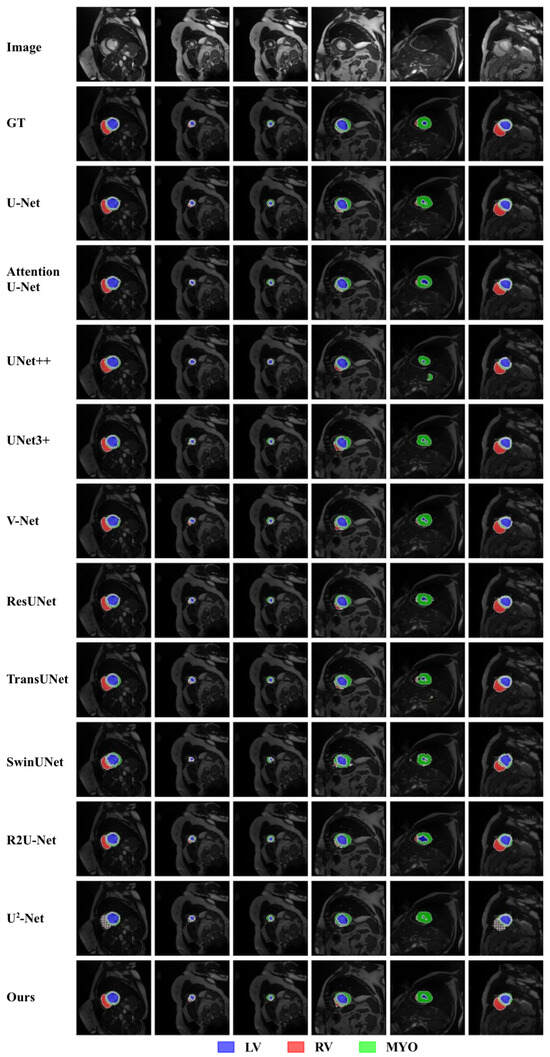

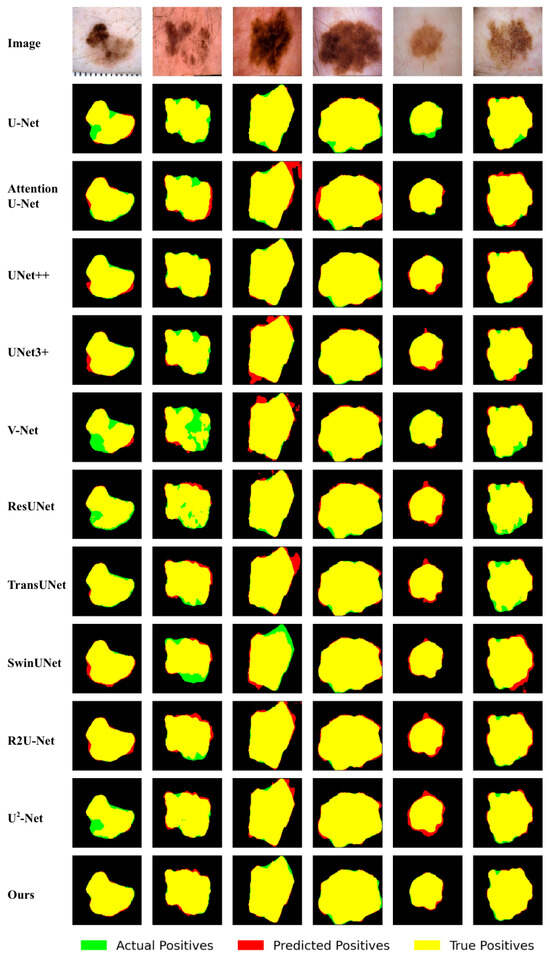

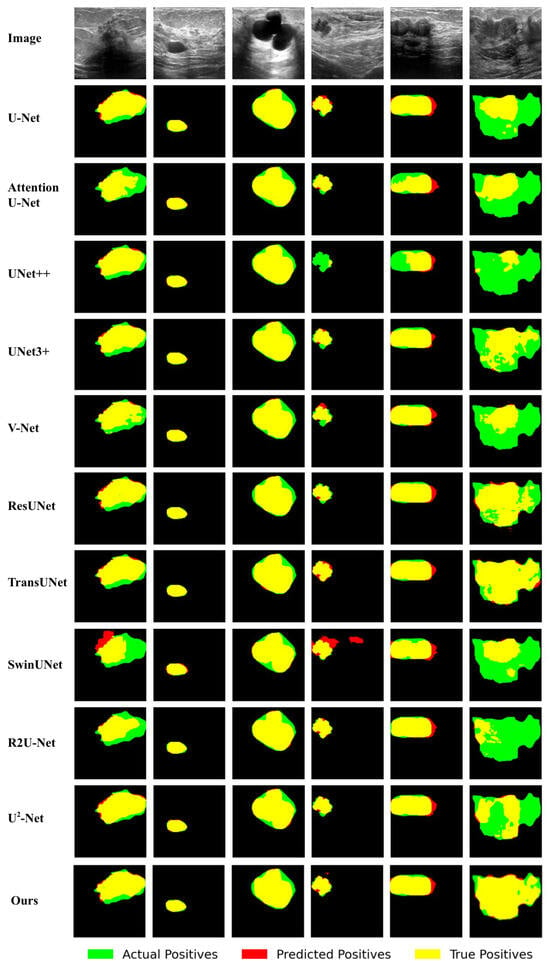

Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6 illustrate the qualitative comparison for the Synapse, ACDC, ISIC 2018, and BUSI datasets, respectively.

Figure 3.

Qualitative comparison of different approaches by visualization on the Synapse dataset.

Figure 4.

Qualitative comparison of different approaches by visualization on the ACDC dataset.

Figure 5.

Qualitative comparison of different approaches by visualization on the ISIC 2018 dataset.

Figure 6.

Qualitative comparison of different approaches by visualization on the BUSI dataset.

In Figure 3, the dark blue region indicates the Aorta, the bright green region represents the Gallbladder, and the red region corresponds to the Left Kidney. The cyan region marks the Right Kidney, while the purple region highlights the Liver. The yellow area represents the Pancreas, the light purple region corresponds to the Spleen, and the nearly white region denotes the Stomach. In Figure 4, the red region on the left indicates the right ventricle, the green circular region on the right corresponds to the myocardium, and the blue region on the right denotes the left ventricle. The following can be observed from Figure 3 and Figure 4:

(1) Our RCV-UNet achieves more complete target segmentation. For instance, in the first image example of Figure 3, the stomach is segmented most accurately and completely by the proposed RCV-UNet. In contrast, other methods, such as U-Net [18], result in segmentations with missing regions or internal holes. SwinUNet [29] and -Net [58] fail to capture the stomach region almost entirely. Furthermore, models including U-Net [18], Attention U-Net [26], U-Net++ [24], V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], TransUNet [31], and R2U-Net [39] tend to produce over-segmented outputs, erroneously dividing the stomach into multiple disconnected parts.

Similarly, in the fifth image of Figure 4, when segmenting the left ventricle, U-Net [18], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], TransUNet [31], SwinUNet [29], and -Net [58] all generate disjointed regions, while UNet++ [24] erroneously splits the myocardium into two parts. Additionally, ResUNet [27] overpredicts the extent of the left ventricle, while Attention U-Net makes incorrect predictions for the right ventricle. In contrast, only our RCV-UNet successfully and accurately segments all three regions: the right ventricle, myocardium, and left ventricle.

(2) Our RCV-UNet achieves more accurate target boundary segmentation. For example, in the second image of Figure 3, our proposed RCV-UNet produces the most accurate segmentation of the Pancreas. Models such as UNet++ [24], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], SwinUNet [29], and -Net [58] fail to fully capture the sharp protrusion at the rightmost end of the pancreas, while U-Net [18], UNet++ [24], and TransUNet [31] are unable to correctly segment the leftmost portion of the organ.

Furthermore, in the first image of Figure 4, the mask generated by RCV-UNet is the closest to the ground truth (second row). Other methods, such as UNet++ [24], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], TransUNet [31], and SwinUNet [29], show poor segmentation of the right ventricle. -Net [58] severely mispredicts the right ventricle region. Moreover, Attention U-Net [26], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], and TransUNet [31] fail to accurately segment the myocardium and left ventricle. Attention U-Net [26], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], and ResUNet [27], in particular, incorrectly predict the right side of the myocardium, producing protrusions where the ground truth shows a smoother, more circular shape. Additionally, U-Net [18] produces incorrect predictions in the myocardium region.

In Figure 5 and Figure 6, the red regions represent predicted positives, the green regions represent actual positives, and the overlapping areas appear in yellow. Accordingly, the red regions indicate false positives, the green regions indicate false negatives, and the yellow regions represent true positives. The following can be observed from Figure 5 and Figure 6:

(1) Our method demonstrates a stronger capability in complete target segmentation. For instance, in the second image of Figure 5, our proposed RCV-UNet achieves the most accurate and complete segmentation. V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], and -Net [58] exhibit incomplete results with internal holes and discontinuities in the lesion region. Other models either miss portions of the actual lesion or produce over-segmented outputs that extend beyond the lesion boundary.

Similarly, in the first image of Figure 6, compared to other methods, our RCV-UNet achieves the highest overlap between the predicted mask and the ground truth (the largest yellow area) while producing the least incorrect mask (the smallest red area). In the sixth image, the mask generated by our method is most consistent with the ground truth. Other methods, such as U-Net [18], UNet++ [24], and SwinUNet [29], result in a much smaller yellow area, indicating that these methods only predict a small portion of the target.

(2) Our method achieves more precise predictions, particularly in boundary delineation. For example, in the last image of Figure 5, U-Net [18], Attention U-Net [26], UNet++ [24], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], SwinUNet [29], and R2U-Net [39] all exhibit noticeable over-segmentation in the upper part of the lesion region (highlighted in red). Additionally, Attention U-Net [26], UNet3+ [25], and SwinUNet [29] also show over-segmentation in the lower part of the lesion. In contrast, V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], and TransUNet [31] suffer from clear under-segmentation in the lower region (highlighted in green). Compared with these methods, our proposed RCV-UNet produces a result that is closest to the ground truth, with only a small number of missed pixels in the upper-left area and slight over-segmentation in the upper-right region of the lesion.

Furthermore, in the fourth image of Figure 6, although most methods can roughly predict the target, SwinUNet [29] predicts a significant amount of incorrect regions, while UNet++ [24] identifies only a small portion of the target. Upon closer inspection of the target boundaries, methods such as U-Net [18], V-Net [23], and TransUNet [31] make incorrect predictions on the top and right boundaries of the target. Attention U-Net [26], UNet3+ [25], V-Net [23], ResUNet [27], and -Net [58] fail to predict the bottom target area. Among the remaining methods, R2U-Net and our RCV-UNet, it can be observed that RCV-UNet produces fewer false positives (smaller red areas), indicating better prediction performance.

These observations demonstrate that RCV-UNet excels in achieving more complete target segmentation and higher segmentation accuracy, particularly in boundary delineation. This is because RCV-UNet not only captures global contextual information but also effectively extracts and learns local features.

3.6. Quantitative Results

The data in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 clearly show the quantitative results of our proposed network compared with the other 10 baseline methods across four datasets. The best performance result is highlighted in bold, and the second-best performance is underlined. The following can be observed:

Table 2.

The performance of all baseline methods and ours on the Synapse dataset.

Table 3.

The average performance of all baseline methods and ours on the ACDC dataset.

Table 4.

The performance of all baseline methods and ours on the ACDC dataset.

Table 5.

The performance of all baseline methods and ours on the ISIC 2018 dataset.

Table 6.

The performance of all baseline methods and ours on the BUSI dataset.

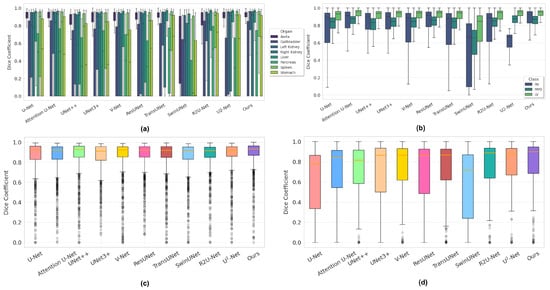

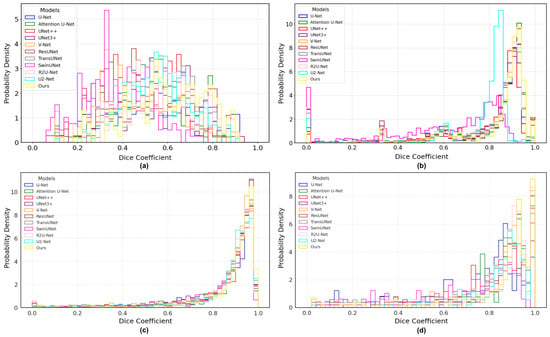

(1) For the Synapse dataset, it is evident that the segmentation of the Gallbladder, Pancreas, and Stomach is relatively challenging. As shown in Table 2, RCV-UNet achieves outstanding performance, with an average Dice score of 0.812, outperforming the second-best method by 3.5%. Specifically, RCV-UNet ranks first among all competitors on five out of the eight organs: Gallbladder, Left Kidney, Right Kidney, Pancreas, and Spleen, while ranking second for the Aorta, Liver, and Stomach, falling behind by 0.5, %0.6%, and 2.0%, respectively. In Figure 7a, it can be observed that our method significantly outperforms others for the Aorta, Left Kidney, and Spleen, with boxplots that are not only narrower but also distributed higher overall. The segmentation performance for the Gallbladder is also better, as indicated by a higher median value. Although the boxplot of the Right Kidney is relatively wide, its median is higher than that of the competing methods. For the Liver and Stomach, our method performs slightly worse than the top-performing TransUNet [31]. Moreover, as shown in Figure 8a, although the Dice distribution of our model does not exhibit a strong right-skewed trend, it still consistently outperforms the other methods.

Figure 7.

Dice coefficient distribution boxplot of different networks on four datasets. (a) Synapse; (b) ACDC; (c) ISIC 2018; (d) BUSI.

Figure 8.

Dice coefficient distribution histogram of different networks on four datasets. (a) Synapse; (b) ACDC; (c) ISIC 2018; (d) BUSI.

(2) For the ACDC dataset, a multi-class segmentation task, it can be observed that segmenting RV and MYO is more challenging than LV, as reflected by the higher Dice scores achieved for LV. From Table 3, RCV-UNet still demonstrates excellent performance, with its average predicted metrics ranking among the top one across all categories. From Table 4, RCV-UNet is particularly outstanding in segmenting RV, where it surpasses the second-best method by 1% in Dice and 1.4% in IoU. As can be seen from Figure 7b, the distributions of Dice coefficients for RV, MYO, and LV obtained by RCV-UNet are relatively concentrated. This is particularly evident in the MYO and LV categories, where the interquartile range of the boxplot is narrower, indicating higher prediction stability. Additionally, the median Dice coefficient of the boxplot corresponding to our method in the RV and LV categories is significantly higher than that of other competitors. In the MYO category, the performance of RCV-UNet has slightly decreased, but its overall performance remains within a reasonable range. As shown in the histogram in Figure 8b, the Dice score distribution predicted by RCV-UNet is noticeably skewed to the right compared to the other 10 methods, with a higher concentration in the range between 0.8 and 1.0. This indicates that RCV-UNet demonstrates superior overall segmentation performance on the test samples.

(3) For the ISIC 2018 dataset, our network achieves the best performance across four evaluation metrics: Dice, IoU, Accuracy, and Sensitivity. Specifically, as shown in Table 5, our method achieves Dice, IoU, and Sensitivity scores of 0.870, 0.771, and 0.857, respectively, surpassing the second-best competitor by 1.2%, 1.9%, and 2.7%. As illustrated in the boxplot in Figure 7c, our method outperforms other approaches in terms of the median, first-quartile, and third-quartile Dice values, and exhibits a more compact interquartile range. Furthermore, Figure 8c shows that the Dice distribution of RCV-UNet is clearly right-skewed, with the highest proportion of cases falling within the 0.8–1.0 range. Notably, the proportion of predictions in the 0.98–1.0 interval is notably higher than that of the other methods. These results demonstrate the superior segmentation performance of RCV-UNet.

(4) For the BUSI dataset, our network achieves the best performance across all six metrics. Specifically, the Dice, IoU, and Pre scores reach 0.773, 0.630, and 0.879, respectively, surpassing the second-best competitor by 3.5%, 4.5%, and 5%, as shown in Table 6. From the Dice coefficient boxplot in Figure 7d, it is evident that RCV-UNet exhibits higher median, first-quartile, and third-quartile values than the competing methods. Moreover, the interquartile range is the smallest, indicating more stable performance. Additionally, the lower number of outliers demonstrates that our network exhibits greater robustness across a wide range of samples. From the histogram in Figure 8d, it is evident that the Dice value distribution of RCV-UNet exhibits a stronger right skew with a higher peak density, highlighting its advantage in segmentation quality.

3.7. Ablation Study

3.7.1. Effect of Different Network Settings

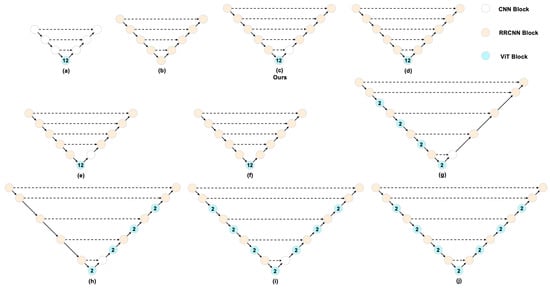

Figure 9 presents two competitor architectures and eight variants of our network, and Table 7 reports the detailed results.

Figure 9.

A brief illustration of the ablation study on the network block settings for hybrid architectures. (a) TransUNet; (b) R2U-Net; (c) our proposed model; (d) is identical to (c) except that the first decoder block replaces its CNN with an RRCNN; (e) removes the deepest skip connection from (c); (f) removes the deepest skip connection from (d); (g) inserts ViT blocks into both the encoder (alternating with RRCNN) and the bottleneck; (h) inserts ViT blocks into the decoder and the bottleneck; (i) inserts ViT blocks into the encoder, decoder, and bottleneck; (j) follows the same configuration as (i) but replaces the first decoder block’s CNN with an RRCNN.

Table 7.

The average performance of ablation study methods on the ACDC dataset.

Effectiveness of combining RRCNN with a bottleneck ViT. Comparing (a) with (c) shows a substantial gain (+0.039) achieved by replacing CNN blocks with RRCNN blocks in the encoder–decoder. Similarly, comparing (b) with (c) shows that replacing an RRCNN bottleneck with a ViT bottleneck yields a notable improvement (+0.034). These results indicate that integrating RRCNN and ViT within a U-Net architecture is effective.

First decoder stage: CNN block outperforms RRCNN. The comparisons between (c) and (d), (e) and (f), and (i) and (j) indicate that using a simple CNN block in the first decoder stage yields better performance than an RRCNN block. This stage primarily reconstructs spatial details from globally encoded features and fuses them with the deepest skip connection; local convolutions provide more stable statistics and preserve high-frequency boundaries, whereas recurrent refinement at this low resolution tends to over-smooth and complicate optimization.

Deepest skip connection: Consistent gains. The comparisons between (c) and (e) and between (d) and (f) show that retaining the deepest skip connection (i.e., one level above the bottleneck) consistently improves performance. The bottleneck skip injects strong global semantics into the first decoder stage, enhances cross-scale consistency during early up-sampling, and shortens the gradient path; this coarse prior complements shallow skips that refine boundaries, stabilizing feature fusion.

ViT placement across scales: bottleneck-only is best and most efficient. Comparing (c), (g), (h), and (i) indicates that placing a single ViT at the bottleneck achieves the best performance; adding ViT to the encoder and bottleneck or to the decoder and bottleneck yields similar but inferior results, and using ViT in the encoder, decoder, and bottleneck narrows the gap yet still lags behind (c). We attribute this to the bottleneck being the most effective location for aggregating global context while CNN/RRCNN blocks recover local spatial details; additional ViT blocks introduce heterogeneous feature statistics across skip connections and extra normalization/attention overhead, complicating fusion and optimization. Correspondingly, inserting ViT blocks into the encoder or decoder significantly increases FLOPs/parameters and notably reduces training throughput.

Overall, placing ViT blocks only at the bottleneck, using RRCNN blocks in the main encoder–decoder (with a CNN block in the first decoder stage), and retaining the deepest skip connection yields the best performance and efficiency, whereas extending ViT to the encoder or decoder provides limited gains while markedly increasing computational cost and reducing throughput.

3.7.2. Effect of the Number of Skip Connections

We ablate the number of skip connections from 0 to 5 while holding all other settings fixed (Table 8). The largest single-step improvement arises when introducing the first skip: Dice increases from 0.765 to 0.855 (+0.090), and IoU from 0.625 to 0.748 (+0.123), confirming that the mere presence of skip connections is pivotal for recovering fine structures and stabilizing optimization.

Table 8.

The average performance of ablation study methods for skips on the ACDC dataset.

Beyond the first skip, additional skips yield steady—albeit smaller—gains. In particular, the fifth skip—i.e., the deep skip adjacent to the ViT bottleneck—provides the largest marginal improvement among the added skips (4→5): Dice improves from 0.869 to 0.889 (+0.020) and IoU from 0.771 to 0.802 (+0.031). This indicates that injecting high-level semantics from the stage immediately preceding the bottleneck into the decoder is especially effective, reducing boundary ambiguity and mitigating both false positives and false negatives.

Overall, performance improves with the number of skips, with two effects standing out: (i) the presence versus absence of skip connections drives the largest jump, and (ii) among the configurations that include skips, the bottleneck-adjacent (fifth) skip has the strongest incremental impact. Consequently, we adopted five skip connections in the final model, which achieves the best overall results.

3.7.3. Effect of Different Up-Sampling

As shown in Table 9, transposed convolution achieves the best performance, clearly outperforming bilinear and nearest-neighbor interpolation. We attribute this advantage to its learnable parameters, which enable adaptive restoration of structural details and sharper boundary delineation during up-sampling. In contrast, bilinear interpolation, although smooth and computationally efficient, often oversmooths boundaries and reduces overlap accuracy, while nearest-neighbor interpolation produces blocky artifacts and loses fine details. These results highlight that learnable up-sampling provides a more effective mechanism for accurate medical image segmentation.

Table 9.

The average performance of ablation study methods for up-sampling on the ACDC dataset.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we propose a hybrid architecture, RCV-UNet, which integrates RRCBs with ViT, for medical image segmentation. This network combines the attention mechanism of Transformers with the feature accumulation capability of recurrent residual convolutions. It is capable of capturing global contextual information, making it well-suited for handling complex images with long-range dependencies, while excelling in local feature extraction and edge detail modeling. As a result, it achieves superior segmentation performance overall. To evaluate the effectiveness of our approach, we conducted experiments on four different medical imaging applications: CT, MRI, Dermoscopy, and ultrasound images. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed RCV-UNet outperforms 10 state-of-the-art methods in terms of performance and robustness across all evaluated datasets. Beyond empirical performance, RCV-UNet can be conceptually viewed through a fractal–fractional lens. Although this analogy is intuitive rather than rigorous, its hierarchical structure and recursive dynamics offer a heuristic explanation for how the model may relate to the self-similar and continuous characteristics of anatomical patterns.

4.1. Results Discussion

The experimental results on four distinct medical imaging modalities, namely CT, MRI, Dermoscopy, and ultrasound, demonstrate the strong segmentation capabilities of the proposed RCV-UNet. By integrating RRCBs with ViT’s attention mechanism, the network effectively combines global contextual reasoning with robust local feature extraction. This synergy is particularly beneficial for tasks that require both an understanding of overall structure (such as organ boundaries or large-scale pathologies) and precise edge delineation (e.g., identifying subtle lesion borders).

When benchmarked against 10 state-of-the-art methods, RCV-UNet shows superior performance in terms of quantitative metrics (e.g., Dice coefficient and IoU) and visual segmentation quality across all evaluated datasets. Additionally, the network exhibits a high degree of robustness, maintaining competitive results, even under varied imaging conditions, intensity distributions, and tissue characteristics. These findings suggest that the combination of recurrent residual convolutional feature refinement and Transformer-based global attention contributes to a more comprehensive and accurate interpretation of medical images.

4.2. Limitations Discussion

Figure 10 presents several less-than-ideal segmentation examples produced by our model. On the Synapse dataset, the overall quality is reasonable, yet small or slender organs (e.g., the pancreatic tail and gallbladder) are often under-segmented, and mild spillover appears along weak boundaries, such as the liver–spleen interface; this is likely due to overlapping HU distributions among adjacent abdominal organs, low boundary contrast, and pronounced class imbalance. On the ACDC dataset, predictions for the right ventricle (red) exhibit fragmentation and discontinuities with local gaps, likely attributable to cardiac motion and blood-flow artifacts, while the myocardium (green ring) appears thinned or eroded. For the ISIC2018 dataset, most of the lesions overlap with the ground truth (yellow), but a red halo of over-segmentation persists around the contour, with small green spikes of under-segmentation, largely due to hair, rulers, and illumination gradients that the model mistakes for boundaries. In the BUSI dataset, the tumor core is largely correct, yet spurious red protrusions appear at the periphery, and green misses occur in regions of posterior acoustic shadowing and low contrast, attributable to speckle noise and shadowing that blur the true boundary.

Figure 10.

Representative non-ideal segmentations across datasets.

We hypothesize that these shortcomings share several common roots: strong noise/artifacts; the prevalence of weak boundaries and thin/small structures; and the tendency of encoder–decoder architectures to lose and smooth boundary details through down- and up-sampling. Moreover, Dice-centric losses are relatively insensitive to ring-like/thin structures and are easily biased by class imbalance. Finally, the absence of explicit boundary, shape, or topology constraints and modality-specific preprocessing (e.g., hair removal or despeckling) further degrades performance. As a result, the model is more prone to over-segmentation, under-segmentation, discontinuities, and leakage in these challenging scenarios.

For the Synapse dataset, large organs (e.g., the liver, spleen, or stomach) occupy many voxels with relatively stable contrast, whereas small organs (e.g., the gallbladder or pancreas) are rare (<1–3% per slice), low-contrast, and highly variable. Despite our overall gains, these dataset-intrinsic factors remain the main limitation: in Figure 7a, small-organ Dice medians and dispersion improve over the baselines yet still exhibit larger variance than those of large organs; in Figure 8a, the low-Dice left tail () is shortened and shifts rightward but is not eliminated. Our hybrid design stabilizes cross-scale feature fusion and preserves fine-grained boundaries, leading to higher mean performance and reduced variance, yet residual failures persist, likely driven by partial volume effects and cross-slice inconsistency.

Despite the promising performance, the RCV-UNet architecture has several limitations. First, the incorporation of Transformers introduces considerable computational overhead, especially in terms of memory consumption, as illustrated in Table 10. The self-attention mechanism in ViTs can become resource-intensive for high-resolution medical images, potentially limiting its feasibility on standard hardware or edge devices. Second, while the hybrid design leverages both global and local features, hyperparameter tuning—such as balancing the number of Transformer blocks and recurrent residual layers—can be challenging and time-consuming.

Table 10.

Computational cost comparison in terms of parameters, FLOPs, and inference time on the Synapse dataset with [1 × 224 × 224 × 1] inputs.

Another point to consider is that while recurrent blocks have been shown to be beneficial in enhancing feature accumulation and refining boundary details within the TransUNet framework, the design space for such hybrid networks is still not fully explored. There may exist more sophisticated recurrent or attention-based architectures that further improve the synergy between local and global feature extraction. Future research could investigate the use of more advanced recurrent units (e.g., GRU or LSTM variants) or deeper Transformer configurations to assess whether these more complex approaches yield significantly better performance or robustness.

Furthermore, the network’s performance may depend on the availability of sufficient training data to learn meaningful global attention patterns. In scenarios where annotated medical images are scarce, the overfitting or underutilization of the Transformer components could diminish the network’s effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Z.W. (Ziru Wang) contributed to coding, experimental setup, and writing the original draft. Z.W. (Ziyang Wang) contributed to the conception of the study, supervision, and proofreading. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The original data were provided by a third party and may require additional permission for access.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Masood, S.; Sharif, M.; Masood, A.; Yasmin, M.; Raza, M. A survey on medical image segmentation. Curr. Med Imaging 2015, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wu, G.; Suk, H.I. Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litjens, G.; Kooi, T.; Bejnordi, B.E.; Setio, A.A.A.; Ciompi, F.; Ghafoorian, M.; van der Laak, J.A.; van Ginneken, B.; Sánchez, C.I. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. 2017, 42, 60–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Lei, T.; Cui, R.; Zhang, B.; Meng, H.; Nandi, A.K. Medical image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IET Image Process. 2022, 16, 1243–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Voiculescu, I. Triple-view feature learning for medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the MICCAI Workshop on Resource-Efficient Medical Image Analysis, Singapore, 22 September 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Voiculescu, I. RAR-U-Net: A residual encoder to attention decoder by residual connections framework for spine segmentation under noisy labels. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Anchorage, AK, USA, 19–22 September 2021; pp. 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Losa, G.A. The fractal geometry of life. Riv. Biol. 2009, 102, 29–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Yang, F.; Yang, Q. A Study of Adaptive Fractional-Order Total Variational Medical Image Denoising. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y. A novel and efficient tumor detection framework for pancreatic cancer via CT images. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 July 2020; pp. 1160–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Voiculescu, I. Dealing with unreliable annotations: A noise-robust network for semantic segmentation through a transformer-improved encoder and convolution decoder. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A Computational Approach to Edge Detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1986, PAMI-8, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, G.; Wang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, R.; Peng, W. A Variational Level Set Image Segmentation Method via Fractional Differentiation. Fractal Fract. 2022, 6, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Xu, R.; Peng, R.; Wang, J.; Kim, J. Multifractal Detrended Fluctuation Analysis Combined with Allen–Cahn Equation for Image Segmentation. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber Jabdaragh, A.; Firouznia, M.; Faez, K.; Alikhani, F.; Alikhani Koupaei, J.; Gunduz-Demir, C. MTFD-Net: Left atrium segmentation in CT images through fractal dimension estimation. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2023, 173, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-López, K.M.; Halimi, A.; Tourneret, J.Y.; Wendt, H. Bayesian Multifractal Image Segmentation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.08694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, G.; Wang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Wei, G.; Huang, S. VG-SAM: Visual In-Context Guided SAM for Universal Medical Image Segmentation. Fractal Fract. 2025, 9, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Shelhamer, E.; Darrell, T. Fully Convolutional Networks for Semantic Segmentation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1411.4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1505.04597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesamian, M.H.; Jia, W.; He, X.; Kennedy, P. Deep Learning Techniques for Medical Image Segmentation: Achievements and Challenges. J. Digit. Imaging 2019, 32, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicek, O.; Abdulkadir, A.; Lienkamp, S.S.; Brox, T.; Ronneberger, O. 3D U-Net: Learning Dense Volumetric Segmentation from Sparse Annotation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.06650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: A self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat. Methods 2020, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Voiculescu, I. Quadruple augmented pyramid network for multi-class COVID-19 segmentation via CT. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Guadalajara, Mexico, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 2956–2959. [Google Scholar]

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.A. V-Net: Fully Convolutional Neural Networks for Volumetric Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.04797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, L.; Tong, R.; Hu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y.W.; Wu, J. UNet 3+: A Full-Scale Connected UNet for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.08790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktay, O.; Schlemper, J.; Folgoc, L.L.; Lee, M.; Heinrich, M.; Misawa, K.; Mori, K.; McDonagh, S.; Hammerla, N.Y.; Kainz, B.; et al. Attention U-Net: Learning Where to Look for the Pancreas. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.03999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diakogiannis, F.I.; Waldner, F.; Caccetta, P.; Wu, C. ResUNet-a: A deep learning framework for semantic segmentation of remotely sensed data. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote. Sens. 2020, 162, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, X.; Tian, Q.; Wang, M. Swin-Unet: Unet-like Pure Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.05537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamizadeh, A.; Tang, Y.; Nath, V.; Yang, D.; Myronenko, A.; Landman, B.; Roth, H.; Xu, D. UNETR: Transformers for 3D Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Luo, X.; Adeli, E.; Wang, Y.; Lu, L.; Yuille, A.L.; Zhou, Y. TransUNet: Transformers Make Strong Encoders for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.04306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, M.; Metaxas, D. UTNet: A Hybrid Transformer Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.00781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Deng, Z.; Li, D.; Yuan, X. MISSFormer: An Effective Medical Image Segmentation Transformer. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.07162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Cao, P.; Wang, J.; Zaiane, O.R. UCTransNet: Rethinking the Skip Connections in U-Net from a Channel-wise Perspective with Transformer. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2109.04335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valanarasu, J.M.J.; Oza, P.; Hacihaliloglu, I.; Patel, V.M. Medical Transformer: Gated Axial-Attention for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.10662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; He, X. LeViT-UNet: Make Faster Encoders with Transformer for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.08623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xie, S.; Lin, L.; Iwamoto, Y.; Han, X.H.; Chen, Y.W.; Tong, R. Mixed Transformer U-Net For Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, L.; Cai, P.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. BRAU-Net++: U-Shaped Hybrid CNN-Transformer Network for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.00722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Hasan, M.; Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M.; Asari, V.K. Recurrent Residual Convolutional Neural Network based on U-Net (R2U-Net) for Medical Image Segmentation. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.06955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Gu, Y.; Wang, Z. TriConvUNeXt: A pure CNN-Based lightweight symmetrical network for biomedical image segmentation. J. Imaging Inform. Med. 2024, 37, 2311–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Wang, Z. Triple-residual enhanced convolution-and transformer-based hybrid encoder-decoder network for medical image segmentation. Neurocomputing 2025, 652, 131125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, Z. MCV-UNet: A modified convolution & transformer hybrid encoder-decoder network with multi-scale information fusion for ultrasound image semantic segmentation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2146. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Hu, X. Recurrent convolutional neural network for object recognition. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3367–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alom, M.Z.; Hasan, M.; Yakopcic, C.; Taha, T.M. Inception Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network for Object Recognition. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Liang, Y. New methodologies in fractional and fractal derivatives modeling. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2017, 102, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Baleanu, D.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. A new collection of real world applications of fractional calculus in science and engineering. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2018, 64, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, W.; Metzler, R.; Cherstvy, A.G. Anomalous diffusion, nonergodicity, non-Gaussianity, and aging of fractional Brownian motion with nonlinear clocks. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 108, 034113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, R.; Asadi-Aghbolaghi, M.; Fathy, M.; Escalera, S. Bi-Directional ConvLSTM U-Net with Densley Connected Convolutions. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synapse Platform. Synapse Multi-Organ Segmentation Dataset Wiki Page. Available online: https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn3193805/wiki/217789 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Bernard, O.; Lalande, A.; Zotti, C.; Cervenansky, F.; Yang, X.; Heng, P.A.; Cetin, I.; Lekadir, K.; Camara, O.; Gonzalez Ballester, M.A.; et al. Deep Learning Techniques for Automatic MRI Cardiac Multi-Structures Segmentation and Diagnosis: Is the Problem Solved? IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2018, 37, 2514–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Codella, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Tschandl, P.; Celebi, M.E.; Dusza, S.; Gutman, D.; Helba, B.; Kalloo, A.; Liopyris, K.; Marchetti, M.; et al. Skin Lesion Analysis Toward Melanoma Detection 2018: A Challenge Hosted by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.03368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabyani, W.; Gomaa, M.; Khaled, H.; Fahmy, A. Dataset of breast ultrasound images. Data Brief 2020, 28, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abadi, M.; Agarwal, A.; Barham, P.; Brevdo, E.; Chen, Z.; Citro, C.; Corrado, G.S.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; et al. TensorFlow: Large-Scale Machine Learning on Heterogeneous Systems. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1603.04467. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, C.; Dehghan, M.; Zaiane, O.R.; Jagersand, M. U2-Net: Going deeper with nested U-structure for salient object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 106, 107404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.