Abstract

Efficient and accurate vision models are essential for real-world applications such as medical imaging and deepfake detection, where both performance and computational efficiency are critical. While recent vision models achieve high accuracy, they often come with the trade-off of increased size and computational demands. In this work, we propose MobileNet-HeX, a new ensemble model based on Heterogeneous MobileNet eXperts, designed to achieve top-tier performance while minimizing computational demands in real-world vision tasks. By utilizing a two-step Expand-and-Squeeze mechanism, MobileNet-HeX first expands a MobileNet population through diverse random training setups. It then squeezes the population through pruning, selecting the top-performing models based on heterogeneity and validation performance metrics. Finally, the selected Heterogeneous eXpert MobileNets are combined via sequential quadratic programming to form an efficient super-learner. MobileNet-HeX is benchmarked against state-of-the-art vision models in challenging case studies, such as skin cancer classification and deepfake detection. The results demonstrate that MobileNet-HeX not only surpasses these models in performance but also excels in speed and memory efficiency. By effectively leveraging a diverse set of MobileNet eXperts, we experimentally show that small, yet highly optimized, models can outperform even the most powerful vision networks in both accuracy and computational efficiency.

1. Introduction

In recent years, vision models have demonstrated remarkable performance across a variety of tasks [1,2], including image classification, medical imaging, and deepfake detection [3,4,5]. However, the primary challenge lies in achieving a balance between accuracy and computational efficiency. Many state-of-the-art (SoA) vision models achieve high performance but often come at the cost of significantly increased model size, memory usage, and inference time [6,7,8,9]. These models may not be ideal for real-world applications where both accuracy and resource constraints are critical factors [10]. Additionally, training and deploying such models often introduces complexity, making it difficult to adapt them for diverse tasks without extensive fine-tuning.

Ensemble learning [11] has emerged as a viable solution to address these issues by combining multiple smaller, specialized models (base learners) to achieve performance comparable to or even surpassing heavy, top-performing models. The idea is that a diverse set of base learners can capture various aspects of the data, improving generalization and robustness [12]. By aggregating the outputs of these models, ensemble methods can maintain high accuracy while being more resource-efficient than deploying a single, large model. However, a significant challenge remains in model selection for ensembling, where the choice of base learners and their combination can greatly affect the overall performance and computational costs of the ensemble [13].

Traditional approaches like Greedy Search [14] and Forward Selection Pruning [15] tend to overfit to validation scores by focusing primarily on performance metrics. On the other hand, correlation [16] and Q-statistic [17] selection methods emphasize diversity but lack formal mechanisms to ensure consistent performance improvements. More recent techniques like Snapshot Ensembles [12] and Stochastic Weight Averaging [13] efficiently generate diverse models by leveraging the training dynamics of a single model, but they do not explicitly target model heterogeneity in their selection process.

To address these challenges, we propose MobileNet-HeX, a new model designed to optimize both performance and efficiency, based on ensembling Heterogeneous MobileNet eXperts. The MobileNet-HeX model is constructed via the proposed Expand-and-Squeeze (ES) approach, which generates a population of diverse MobileNet models using randomized training setups (Expand phase). In the Squeeze phase, models are selectively pruned based on their performance and heterogeneity, which is determined through a clustering-based algorithm. This algorithm groups models based on the similarity of their prediction probabilities on the validation set. Finally, from each cluster, we select the top-performing model to form the final ensemble. This proposed method, referred to as Heterogeneous eXperts (HeX), retains only the most complementary and high-performing models, resulting in a drastically smaller number of selected models to form the final ensemble. By minimizing the redundancy in the final ensemble, this approach reduces the risk of validation overfitting, while lowering computational demands.

Compared to traditional ensembling methods [14,15], which often overfit to validation data or fail to ensure diverse model behavior, the proposed HeX approach mitigates these issues by explicitly focusing on selecting models with heterogeneous behaviors, reducing redundancy in the final ensemble. Moreover, while techniques like Snapshot Ensembles [12] and Stochastic Weight Averaging [13] ensure diversity through training dynamics, the proposed method goes further by using clustering to ensure heterogeneity across the models. This clustering process naturally promotes diversity, as models from different clusters exhibit distinct prediction behaviors. By selecting top performers from these clusters, we create an ensemble, which is both diverse and efficient, capturing unique aspects of the data while minimizing validation overfitting and computational costs.

In order to evaluate the proposed MobileNet-HeX model, we assessed its performance on real-world case study tasks such as skin cancer classification and deepfake detection, using three key metrics: Accuracy, area under the curve (AUC), and geometric mean (GM). Accuracy provides a straightforward measure of overall correctness but may fail to reflect model performance in imbalanced datasets [18] while AUC evaluates a model’s ability to distinguish between classes across all decision thresholds, offering a more comprehensive view of classification effectiveness. GM is particularly crucial for imbalanced datasets since it ensures balanced evaluation by combining sensitivity and specificity. These selected metrics were chosen to provide a comprehensive evaluation of model performance, addressing both overall correctness and class-specific robustness.

The main contributions of this research work are described as follows:

- We propose the Expand-and-Squeeze (ES) approach, a two-step framework for efficiently constructing MobileNet-based ensemble architectures for vision tasks. In the Expand phase, a diverse population of MobileNets is generated through randomized training setups, while in the Squeeze phase, models are pruned based on performance and heterogeneity. This process results in a scalable and efficient ensemble, optimized for real-world vision tasks.

- We propose a new heterogeneity-based selection algorithm, called HeX, which uses clustering to identify diverse base learners within the expanded model pool. This algorithm selects the top-performing models from distinct clusters, ensuring that the final ensemble is composed of heterogeneous experts, which capture unique data aspects and maximize ensemble performance.

- We propose MobileNet-HeX, an ensemble model of Heterogeneous MobileNet eXperts, which achieves high accuracy and computational efficiency. The model utilizes sequential quadratic programming to optimally combine the selected MobileNets from the ES approach, ensuring robust performance in the final ensemble.

- We demonstrate that MobileNet-HeX delivers top-tier performance on real-world vision tasks, such as skin cancer classification and deepfake detection, outperforming large SoA vision models in both accuracy and computational efficiency. This study experimentally shows that a smaller, strategically optimized ensemble can achieve superior results with lower computational demands.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the state-of-the-art vision classification models and ensembling approaches relevant to this work. Section 3 provides a detailed description of the proposed MobileNet-HeX framework, including its methodology and construction. Section 4 presents the experimental results, offering an in-depth analysis and comparison with existing methods. Section 5 discusses the broader implications of the proposed approach, highlighting key insights from the experimental results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper with key findings and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

In this section, we review the state-of-the-art vision models and ensemble selection approaches relevant to the proposed MobileNet-HeX framework.

2.1. Vision Models

Recent advancements in CNNs and Vision Transformers have significantly improved performance on various vision tasks, especially on large-scale datasets like ImageNet. The following state-of-the-art (SoA) models are benchmarked in this work, alongside the proposed MobileNet-HeX one.

MobileNetV3 is the latest iteration of the MobileNet family, specifically optimized for mobile and low-resource environments. The MobileNetV3-Small version uses advanced techniques such as squeeze-and-excitation blocks and hard-swish activations to balance efficiency and accuracy while maintaining a very compact model size [19]. EfficientNet introduces a compound scaling method, which uniformly scales all dimensions of depth, width, and resolution. EfficientNet-B0 is the baseline model in the EfficientNet family, balancing performance and efficiency on ImageNet classification tasks [20]. Vision Transformer (ViT) introduced Transformer-based architectures to vision tasks by partitioning images into patches and applying self-attention mechanisms. ViT has shown outstanding performance on ImageNet when trained with sufficient data [21]. Data-efficient Image Transformer (DeiT3) introduces a more efficient use of training data, leveraging Transformer architectures for vision tasks while achieving top-tier performance on ImageNet with fewer resources [22]. RegNet is a flexible model family designed through a principled network design approach. RegNetY-16GF is one of the most efficient models, focusing on balancing accuracy and computational cost across diverse tasks [6]. Swin Transformer introduces a hierarchical Vision Transformer approach, which computes self-attention within shifted windows. It has achieved state-of-the-art results in various vision tasks, including ImageNet classification [7]. ConvNeXt is a pure convolutional model, which revisits standard CNN architectures in light of recent developments in Vision Transformers. It achieves competitive performance on ImageNet while maintaining the benefits of convolutional approaches [8]. CoAtNet (Convolutional Attention Networks) combines the strengths of convolution and self-attention for vision tasks. It achieves excellent accuracy on ImageNet with lower computational cost compared to standard Transformer models [9].

Compared to these models, the proposed MobileNet-HeX model offers low computational and memory demands while achieving top-tier performance, making it suitable for real-world applications like skin cancer classification and deepfake detection.

2.2. Ensembling Selection Approaches

In ensembling, one of the primary challenges is model selection, which involves determining which base learners should be included in the final ensemble. Instead of using all learners generated during the training phase, which can introduce noise and lead to overfitting on the validation set, effective model selection helps refine the ensemble. By carefully selecting specific learners, the ensemble can avoid unnecessary complexity and reduce computational demands, such as memory usage and inference speed, while maintaining high performance.

Greedy Search is a straightforward method where the goal is to iteratively add models which optimize the ensemble’s validation performance. Models are added one at a time based on their individual contributions to the validation score. However, this method is prone to overfitting, as it focuses solely on maximizing validation performance without considering model diversity [14].

Forward Selection Pruning incrementally adds models to the ensemble. If the addition of a new model does not improve validation performance, it is removed. Although this technique mitigates some overfitting issues, it still heavily relies on validation scores, which may lead to suboptimal diversity [15].

The diversity correlation-based method focuses on selecting models which are less correlated with each other in terms of their predictions, aiming to maximize the diversity between the base learners. The key idea is to include models which complement each other by having different error patterns, thus increasing the robustness of the ensemble [16].

The diversity Q-statistic-based method uses the Q-statistic to measure the pairwise agreement between models. Models with low pairwise agreement, i.e., more diverse error patterns, are prioritized for inclusion in the ensemble. This formal diversity metric enhances the performance of the final ensemble [17].

Snapshot Ensembles generate multiple models during a single training run by leveraging cyclical learning rates. Instead of training multiple independent models, this method captures different “snapshots” of the same model during its optimization process. These snapshots are saved at local minima and combined in an ensemble. The method has been shown to improve model selection by creating diverse models without requiring significant additional training time [12].

Stochastic Weight Averaging ensembles combine different checkpoints of a single model during training by averaging their weights. This method captures multiple modes of the loss landscape and helps to smooth the optimization process. The weight-averaged models represent different but complementary aspects of the optimization, which makes them an effective ensemble without training multiple independent models [13].

In contrast to these ensembling selection approaches, the proposed HeX method prioritizes both model diversity and heterogeneity. While traditional methods like Greedy Search and Forward Selection Pruning tend to overfit by focusing solely on validation metrics and diversity-based approaches such as correlation and Q-statistic rely on simplistic measures of model similarity; HeX goes further by clustering models based on the similarity of their prediction probabilities. This clustering ensures that the selected models capture distinct aspects of the data, resulting in a balanced ensemble composed of top-performing models from each cluster. Compared to more recent techniques like Snapshot Ensembles and Stochastic Weight Averaging, which leverage the training dynamics of a single model to create diverse checkpoints, HeX explicitly targets heterogeneity by selecting models with unique predictive behaviors. This allows the proposed approach to build an ensemble which is not only highly accurate but also computationally efficient, as only the most representative models are retained in the final selection, minimizing redundancy and the risk of overfitting.

3. MobileNet-HeX Model

The MobileNet-HeX model is designed as a heterogeneous ensemble of MobileNet base learners optimized for performance, diversity, and efficiency. The model construction involves a three-step Expand-and-Squeeze (ES) methodology, followed by sequential quadratic programming (SQP) to refine and optimize the ensemble.

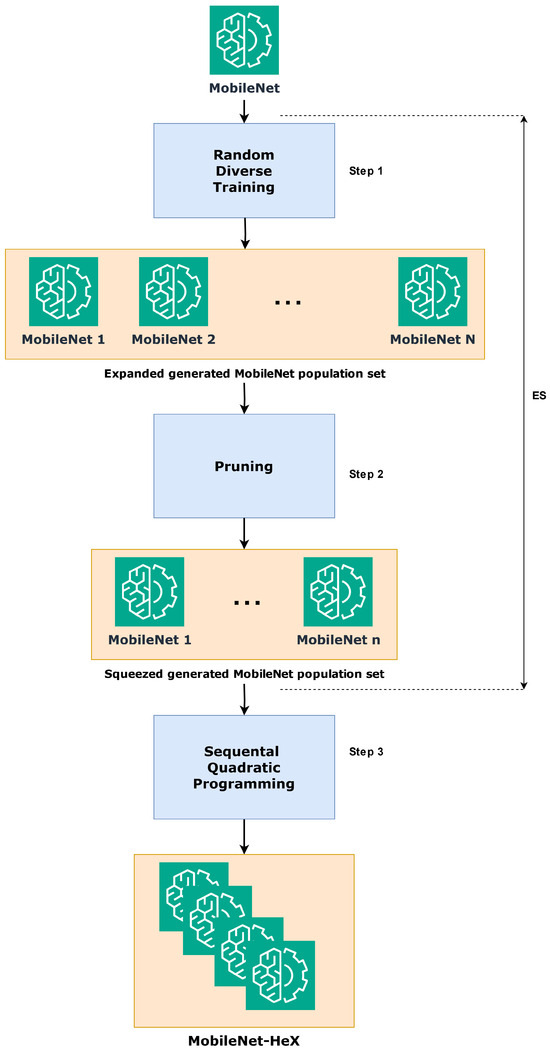

Figure 1 illustrates the entire process of constructing the MobileNet-HeX model. The process begins with the two-step ES phase, which encompasses step 1 and step 2. In step 1, the MobileNet population is expanded by training a diverse set of models under various random conditions and setups. In step 2, a squeezing mechanism is applied, where models are selectively pruned to form a refined set of MobileNets base learners. These learners are chosen based on the proposed heterogeneity-driven approach, ensuring that the resulting set represents a diverse and heterogeneous mix of well-performing models. Following the ES phase, in step 3, sequential quadratic programming (SQP) is employed to combine the squeezed set of MobileNets, generating the final MobileNet-HeX ensemble model.

Figure 1.

Process overview for constructing the proposed MobileNet-HeX model.

Algorithm 1 outlines the high-level process of constructing the MobileNet-HeX model, referencing Algorithms 2–4, which detail the key stages of Random Diverse Training and pruning. Finally, Algorithm 5 details the SQP for extracting the weight contribution of each selected eXpert for building the final inference of MobileNet-HeX model.

3.1. Random Diverse Training

The first phase, Random Diverse Training, focuses on creating a diverse population of MobileNet models. Starting with a pre-trained MobileNet backbone (M), this phase trains multiple MobileNet models under varying conditions to maximize heterogeneity. Initially, the optimal hyperparameters () are identified through validation performance. Deviated ranges are then created from to generate a wide range of random hyperparameter configurations (). Each MobileNet model is initialized with random non-deterministic parameters, trained using a randomly sampled hyperparameter set from and stored after completion. This process iterates N times, resulting in an expanded set of trained MobileNet models, . The generated population forms the input to the subsequent pruning step.

3.2. Pruning

The second phase, pruning, refines the expanded MobileNet population by eliminating under-performing models and identifying a diverse subset for ensemble construction. Each model is evaluated on the validation dataset to compute performance scores (). Models scoring below the threshold, calculated as the average of across all models, are discarded. The remaining models, , undergo an advanced selection process, detailed in Algorithm 4. This step ensures that only the most promising and diverse models progress to the final stages of the MobileNet-HeX pipeline.

| Algorithm 1: MobileNet-HeX Construction | |

| Input M | ▹ pre-trained MobileNet (M) backbone |

| 1: Apply Random Diverse Training to generate | |

| the population set {} | ▹ {}: the Expanded |

| generated MobileNet the population | |

| set {} population set, | |

| comprising N generated trained | |

| models, as extracted by Algorithm 2. | |

| 2: Step 2: Apply Pruning on population set | |

| {} to extract {}. | ▹ {: the Squeezed |

| generated MobileNet set, comprising | |

| the n selected models, | |

| as extracted by Algorithms 3 and 4. | |

| 3: Apply SQP to extract the optimum weights | |

| {} for the n selected models | ▹ Algorithm 5 |

| Output MobileNet-HeX | ▹ The final MobileNet-H model (includes |

| the selected set {} with | |

| the corresponding optimum weights | |

| combination {}). |

| Algorithm 2: Random Diverse Training (Expansion Phase) | |

| Input | ▹ MobileNet (M) backbone, train and validation Dataset (D) |

| 1: Set N value | ▹ The number of total trained MobileNets to be produced. |

| Crucially affects total training time (but not inference time) | |

| and final accuracy performance. | |

| // User-based inner parameters definition | |

| 2: Define , which maximizes performance on | ▹ The initial set of total training |

| training M with | Hyperparameters (H) to be defined |

| 3: Based on define deviated ranges to create | ▹ contains deviated ranges for |

| every hyperparameter of | |

| // Automatic MobileNet generator phase | |

| 4: Randomly Initialize new M | ▹ Every non-deterministic parameter of M is |

| randomly initialized (non-stable random state) | |

| 5: Random sample from and extract | ▹ represents the random set |

| of hyperparameters for training M | |

| 6: Via train M with and store trained M. | |

| 7: Iterate N times the lines {5, 6, 7}, to produce | |

| Output | ▹ The Expanded generated MobileNet population set |

| Algorithm 3: Pruning (Squeezing Phase) | |

| Input | |

| 1: Compute Performance scores of models validating on . | |

| 2: Compute as the average of scores . | |

| 3: Discard models which have performance | ▹ Straightforward initial filtering phase. |

| lower than and extract | Very low performing models have |

| survived models. | inherently low probability to |

| contribute to the final ensemble. | |

| 4: Perform Heterogeneous eXperts algorithm | ▹ The proposed heterogeneity-based |

| approach | |

| for survived models | (Algorithm 4) aims to prevent validation |

| and extract . | overfitting, which can occur in traditional |

| greedy search methods that select models | |

| for ensemble construction based on solely | |

| optimizing the validation score. | |

| Output | ▹ The Squeezed MobileNet eXperts set. |

The proposed Heterogeneous eXperts (HeX) extraction (Algorithm 4) focuses on extracting a diverse set of high-performing MobileNet experts from the pruned set, . First, each model’s prediction probabilities (logits) on the validation dataset are computed, with each logit vector having a size equal to the number of samples in the validation set. These logits serve as feature vectors representing each model’s prediction behavior.

To simplify clustering and reduce noise, the logits are scaled and transformed into a lower-dimensional space (e.g., from validation set size to 50 dimensions) using UMAP [23]. This dimensionality reduction step preserves the essential structure of the logits while enabling computationally efficient clustering. Following this transformation, we employ a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) for clustering. A GMM is a probabilistic model that represents data as a mixture of multiple Gaussian distributions, making it particularly effective for identifying heterogeneous groups with potentially overlapping feature distributions. Its flexibility allows for accurate modeling of complex data patterns, which is crucial for our selection process [24,25].

Next, the optimal number of clusters, , is determined using silhouette scores, which evaluate clustering quality. The models are then grouped into the clusters based on their reduced logits. From each cluster, the model with the highest performance score () is selected, ensuring that only the most effective and diverse models are retained. Finally, a filtering step computes pairwise correlations between the selected models, discarding those with high correlations to maintain diversity. The resulting set of n MobileNet eXperts, , is prepared for ensemble optimization.

| Algorithm 4: Heterogeneous eXperts (HeX) | |

| Input | |

| 1: Set value, | ▹ The maximum number of selected MobileNets |

| to be considered on final ensemble. Crucially | |

| affects inference time and final accuracy | |

| performance. | |

| // Stage 1: Compute model performance and logits | |

| 2: Compute performance scores for | ▹ Performance scores are computed |

| each on | using GM metric. |

| 3: Extract logits (prediction probabilities) | ▹ Each is a vector of size |

| equal | |

| for each model on | to size, where each entry |

| represents the probability predicted | |

| by model for a specific sample | |

| in the validation set. | |

| // Stage 2: Normalize and cluster logits for diversity assessment | |

| 4: Scale logits using a standard scaler | ▹ Ensures logits are on the same |

| scale | |

| for clustering. | |

| 5: Apply dimensionality reduction (e.g., UMAP) to | ▹ This step simplifies clustering |

| transform logits into a lower-dimensional space | by reducing noise and redundant |

| (e.g., from size to 50 dimension size) | dimensions. |

| 6: Search for the optimal number of clusters | ▹ Use the silhouette score to evaluate |

| within a range | clustering quality. Select |

| that maximizes the silhouette score. | |

| 7: Perform clustering using clusters | ▹ Assign each model to one of the |

| on transformed logits | clusters. |

| // Stage 3: Extract top-performing models per cluster | |

| 8: For each cluster select the model with the highest | ▹ Ensures only the most effective |

| and | |

| within the cluster | diverse models are selected. |

| 9: Aggregate selected models into | |

| // Stage 4: Final filtering for uncorrelated models | |

| 10: Compute pairwise correlations between models | ▹ Correlations are calculated to |

| in based on their logits | assess redundancy among |

| on | selected models. |

| 11: Discard models with high correlation | ▹ Remove models that are highly |

| () | correlated to retain only |

| uncorrelated experts. | |

| 12: Extract constituted by the | ▹ This step ensures the selected experts |

| uncorrelated subset | are diverse and uncorrelated, |

| enabling SQP to work effectively. | |

| Output | ▹ The Squeezed MobileNet eXperts set: |

| composed of n diverse, high-performing and | |

| uncorrelated models. |

3.3. SQP and MobileNet-HeX Inference

The final phase applies sequential quadratic programming (SQP) to compute the optimal weight contributions for the selected MobileNet experts. Using the validation dataset, the optimization process starts by assigning equal initial weights to the n models, ensuring that the weights sum to 1 and remain within the range . The objective function minimizes the negative weighted ensemble loss, computed using the selected experts’ predictions.

To handle the constraints and the gradient-free nature of the ensemble loss, a method like Powell [26] is used for optimization. This approach iteratively refines the weights to maximize ensemble performance based on the geometric mean (GM), as evaluated on the validation dataset. The optimization process outputs the final weights, , which, combined with the selected MobileNet experts, define the MobileNet-HeX inference model.

| Algorithm 5: Sequential Quadratic Programming (SQP) and MobileNet-HeX Inference | |

| Input | ▹: Selected MobileNet experts, |

| : validation dataset. | |

| // Stage 1: Define Optimization Problem. | |

| 1: Initialize , where | ▹ Equal initial weights. |

| 2: Define constraints: , | ▹ Weights must be valid probabilities. |

| 3: Set the objective function to minimize | |

| ▹ GM is computed using | |

| the validation set predictions. | |

| // Stage 2: Apply SQP Optimization. | |

| 4: Use a gradient-free method (e.g., Powell) to optimize W | ▹ Calculate that maximize |

| GM | |

| with constraints | |

| Output | ▹ The optimal weights for the ensemble. |

| With the selected eXperts, these weights | |

| define the final MobileNet-HeX inference model. |

4. Experiments

In this section, we present the experimental results and evaluate the performance of the utilized models on the selected datasets.

4.1. Case Study Datasets

To ensure diversity and robustness in our experimental simulations, we employed two distinct datasets representing different areas of real-world applications: the ISIC 2024 dataset for skin cancer detection and the DeepFake Detection Challenge (DFDC) dataset for deepfake detection. Both datasets allow evaluation of model performance across diverse domains in image-based classification tasks.

The ISIC 2024 and DFDC datasets were selected due to their relevance to critical real-world applications that demand both accuracy and computational efficiency. The ISIC 2024 dataset focuses on skin cancer detection, a domain where timely and accurate diagnosis is crucial for improving patient outcomes. The DFDC dataset addresses the growing threat of deepfakes, which pose significant challenges to digital security due to their mass proliferation and the need for rapid, computationally efficient detection in real-time scenarios. These datasets represent diverse challenges in image-based classification, with the ISIC dataset highlighting the difficulty of imbalanced datasets in medical imaging [27] and the DFDC dataset emphasizing the combined need for accuracy and speed in detecting synthetic manipulations [28].

ISIC 2024—Skin Cancer Detection with 3D-TBP: This dataset is part of an ongoing initiative by the International Skin Imaging Collaboration to advance skin cancer detection through digital skin imaging [29]. This dataset, presented in a 2024 Kaggle competition, challenges participants to develop image-based algorithms for identifying histologically confirmed cases of skin cancer from single-lesion crops taken from 3D total-body photos (TBPs). Capturing images with quality comparable to close-up smartphone photos, this dataset aims to enhance early detection and support timely treatment of skin cancer, especially in settings lacking specialized dermatological care. It contains around 400 malignant cases and 400,000 benign instances, representing a broad array of skin phenotypes and lesion types, resembling quality comparable to smartphone-captured images. Images are processed from 3D total-body photographs (TBPs), providing comprehensive data from international dermatology centers aimed at improving early diagnosis in primary care settings.

DeepFake Detection Challenge (DFDC): This dataset is one of the largest publicly available datasets for facial forgery detection [30]. Created through a collaboration between AWS, Facebook, Microsoft, and the Partnership on AI, this dataset addresses the growing issue of deepfake proliferation. The DFDC dataset consists of GAN-generated deepfakes, originally curated to capture diverse individuals in various settings. For our experiments, we created a customized version by extracting one image frame per video and automatically detecting and cropping the faces from each frame. Extracting frames simplifies the dataset and reduces computational overhead, making it more practical for experimentation. Cropping the facial regions further ensures that the model focuses exclusively on the most informative area, enhancing its ability to detect manipulations effectively. This curated dataset contains approximately 100,000 facial image samples. This version of this dataset can be found at the following link: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1eqxVwN2LvUsix4AgGX1E8RO9x9hbQslB?usp=sharing (accessed on 1 December 2024).

4.2. Experimental Setup

For both the DFDC and ISIC 2024 datasets, we split the data into training, validation, and test sets with ratios of 60%, 20%, and 20%, respectively.

All models were trained using the Adam optimizer [31] with an initial learning rate of . Additionally, the Reduce-on-Plateau scheduler [32] was applied, which adjusts the learning rate based on the validation score by decreasing it by a factor of 0.7 after five epochs with no improvement. To prevent overfitting, early stopping [33] and weight decay [34] were also employed. Specifically, training was terminated if validation performance did not improve for 10 consecutive epochs and a weight decay coefficient of was used to penalize large weights, stabilizing the model and enhancing generalization.

As regards the Random Diverse Training phase of the proposed model, we employed a wide range of hyperparameters to ensure diversity among the generated MobileNet models. The training process involved random sampling from pre-defined ranges of key hyperparameters. Learning rates ranged from to , while weight decay values spanned from 0 to . We used the Reduce-on-Plateau scheduler with patience values between 1 and 7 epochs and reduction factors ranging from 0.1 to 0.7. Training batch sizes were sampled between 8 and 128, while all models were trained for a maximum of 50 epochs, with early stopping triggered if validation performance did not improve for 2 to 8 consecutive epochs.

The evaluation metrics used in this study include accuracy (Acc), area under the curve (AUC) and geometric mean (GM) [35,36]. Accuracy provides a direct measure of correct predictions, but it may be misleading for imbalanced datasets. AUC considers the model’s probabilistic outputs, evaluating its ability to distinguish between classes across various thresholds, thus offering a more comprehensive assessment beyond binary outcomes. The GM score measures the balance between sensitivity and specificity, ensuring balanced performance across both classes and making it particularly valuable for datasets where class distribution may vary [37].

4.3. Vision Model Comparison Study

This section presents a comprehensive comparison of various state-of-the-art vision models, including the proposed MobileNet-HeX. Table 1 summarizes the size and design philosophy of all the considered models, while Table 2 reports their performance across two benchmark datasets: ISIC 2024 (a skin lesion classification dataset) and DFDC (Deepfake Detection Challenge).

Table 1.

Size summary and description of all utilized ImageNet vision models in our experimental setup.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of vision models on ISIC 2024 and DFDC datasets.

Table 1 highlights the diversity in model architectures, ranging from lightweight convolutional models like MobileNetV3-Small to large-scale Transformer-based models such as Swin Transformer and CoAtNet. These models differ significantly in their parameter sizes and computational demands. For instance, MobileNetV3-Small, optimized for mobile and embedded devices, is only 6 MB, whereas Swin Transformer and CoAtNet, which leverage self-attention mechanisms, exceed 200 MB. In contrast, the proposed MobileNet-HeX achieves a balance between size and performance by leveraging an ensemble of heterogeneous MobileNetV3-Small experts. The ensemble’s average size of 36 MB, with a range between 12 MB and 60 MB (depending on the number n of selected eXperts; refer to Algorithm 4), demonstrates the scalability and adaptability of the model.

As regards the computational complexity of MobileNet-HeX, this method includes three distinct stages: training diverse MobileNet models, pruning using clustering, and ensemble optimization with SQP. Although training requires generating multiple models, the use of lightweight architectures such as MobileNetV3-Small ensures efficiency. Clustering and optimization are computationally manageable and designed to balance performance and speed. For example, for a hardware configuration such as an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU and 64 GB RAM, the entire training pipeline for can be completed in less than 2 h for typical dataset sizes (such as ISIC 2024 and DFDC).

Table 2 evaluates these models in terms of accuracy (Acc), area under the curve (AUC), and geometric mean (GM). For the ISIC 2024 dataset, the proposed MobileNet-HeX achieves the highest AUC (0.905) and GM (0.809), indicating its superior ability to balance sensitivity and specificity compared to other models. While EfficientNet-B0 achieves a slightly higher accuracy (0.937), its lower GM (0.764) reflects potential imbalances in class-specific performance. Similarly, Transformer-based models such as ViT and DeiT3 perform well in terms of AUC but are outperformed by MobileNet-HeX in GM, emphasizing the proposed method’s robustness in handling imbalanced datasets.

For the DFDC dataset, MobileNet-HeX consistently outperforms all baseline models across all metrics. It achieves the highest accuracy (0.879), AUC (0.954), and GM (0.879), showcasing its effectiveness in the challenging task of deepfake detection. In contrast, models like Swin Transformer and CoAtNet exhibit lower GM values, suggesting that the ensemble-based approach of MobileNet-HeX offers significant advantages in diverse prediction scenarios.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that MobileNet-HeX provides a competitive edge in both efficiency and performance. By leveraging heterogeneous ensembles of lightweight models, it effectively balances computational costs with state-of-the-art performance, making it particularly well suited for real-world applications requiring robust and efficient solutions.

4.4. Ensembling Selection Approach Comparison Study

In this subsection, we compare the proposed Heterogeneous eXperts approach against a variety of ensembling selection strategies often found in the literature. Table 3 provides a summary of these methods, while Table 4 evaluates their performance across two benchmark datasets: ISIC 2024 and DFDC.

Table 3.

Summary of all utilized ensembling selection approaches in our experimental setup.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of ensembling selection approaches on ISIC 2024 and DFDC datasets.

To ensure a fair and stable reference across all methods, we used the MobileNetV3-Small backbone for all approaches in this study. This choice is motivated by the model’s excellent trade-off between accuracy and speed, making it a highly efficient base learner for ensembling [19]. The philosophy behind this decision also aligns with leveraging small, lightweight learners to construct an ensemble that collectively achieves strong overall performance. This setup ensures that the differences in results stem from the ensembling selection strategy rather than the base model’s characteristics.

Table 3 describes the ensembling selection strategies considered in this study. These include baseline methods like including all base learners and more sophisticated approaches such as Snapshot Ensembles and Stochastic Weight Averaging (SWA), both of which leverage training checkpoints to build ensembles. The proposed Heterogeneous eXperts approach, which utilizes clustering-based selection to maximize diversity and performance, is highlighted as a new addition to an ensemble selection pipeline.

Table 4 presents the performance of these approaches. On the ISIC 2024 dataset, the proposed Heterogeneous eXperts approach achieves the highest AUC (0.905) and GM (0.809), demonstrating its ability to select diverse yet complementary models for the ensemble. Although Snapshot Ensembles achieves the highest accuracy (0.916), its GM score (0.800) is slightly lower, indicating potential imbalances in class performance. Similarly, while stochastic methods like SWA deliver competitive performance, their reliance on training checkpoints may limit model diversity.

On the DFDC dataset, the proposed approach again outperforms all others, achieving the best accuracy (0.879), AUC (0.954), and GM (0.879). Overall, the results demonstrate that the proposed Heterogeneous eXperts method effectively combines diversity and performance optimization, outperforming existing ensemble selection approaches on both datasets. By leveraging a clustering-based strategy to extract heterogeneous base learners, it offers a robust and computationally efficient solution for ensembling in real-world scenarios.

4.5. Ablation Study

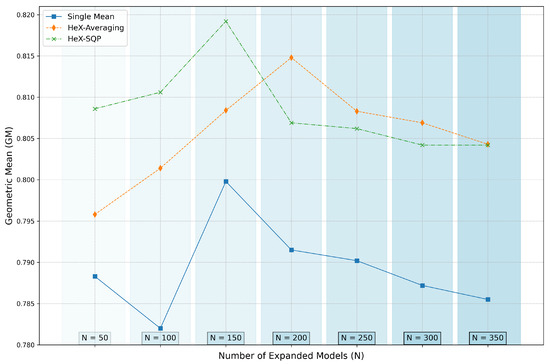

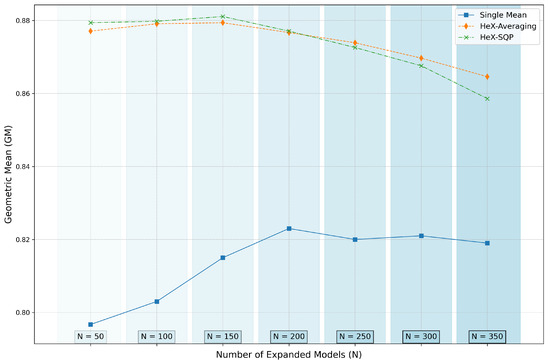

In this subsection, we conduct a detailed ablation study to evaluate the performance of individual models, ensemble methods, and the proposed MobileNet-HeX configurations. The focus is on understanding the impact of ensembling strategies and model selection on the overall performance. The results are presented in Table 5, with visual trends illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3 for the ISIC 2024 and DFDC datasets, respectively.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of individual models and ensemble configurations (N = 50) based on the GM metric.

Figure 2.

GM performance trends on ISIC 2024 dataset for various ensemble configurations and increasing N (expanded models).

Figure 3.

GM performance trends on DFDC dataset for various ensemble configurations and increasing N (expanded models).

Table 5 summarizes the results (based on the GM metric) for all individual selected HeX models: Single mean (the average performance of individual selected models), HeX-Averaging (the selected HeX models combined via averaging), and HeX-SQP (the selected HeX models combined via weighted averaging through SQP optimization) on both the validation (VAL) and test (TEST) splits. Both validation and test performance are reported to highlight the potential for validation overfitting, which occurs when models exhibit strong validation performance but fail to generalize effectively to unseen test data. This study focuses on N = 50, where N refers to the number of MobileNets generated in the expanded population during the Random Diverse Training phase (Algorithm 2). The final ensemble size, however, is determined through the HeX algorithm (Algorithm 4), which led to the selection of and eXperts for ISIC 2024 and DFDC, respectively.

For the ISIC 2024 dataset, the individual models exhibit varied performance, with achieving the highest GM score on the test set (0.841). However, relying on a single model introduces uncertainty, as evidenced by the significantly lower performance of (0.762) and (0.763). The single mean score provides a stable reference but lags behind ensemble methods. HeX-Averaging improves upon the single mean by leveraging the predictions of selected diverse models, achieving a GM of 0.796. The proposed HeX-SQP further enhances performance by optimizing weights for the selected experts, reaching a GM of 0.809.

For the DFDC dataset, a similar trend is observed. While performs well as a single model (0.853 GM on the test set), the single mean score (0.797) underscores the variability in single-model performance. HeX-Averaging improves the ensemble’s performance to 0.877 and HeX-SQP delivers the best result, achieving 0.879 on the test set.

Although certain individual models (e.g., for ISIC 2024 and for DFDC) outperform ensembles in specific cases, selecting these models is uncertain due to variability in validation performance. This variability underscores the robustness of the proposed HeX-SQP approach, which mitigates the risks associated with overfitting by combining diverse and complementary models. HeX-SQP not only achieves consistently high performance across both datasets but also demonstrates its ability to generalize effectively beyond the validation set, avoiding the pitfalls of validation overfitting observed in single-model approaches. This robust generalization highlights the effectiveness of the proposed method for constructing reliable and high-performing ensembles.

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate the GM performance trends for the ISIC 2024 and DFDC datasets, respectively, as N increases. The plots clearly show that HeX-SQP, in general, achieves the highest performance, outperforming both the single-mean baseline and HeX-Averaging for ensemble sizes below . This highlights its ability to effectively combine diverse and complementary models through optimized weighting. Beyond , however, the performance of HeX-SQP begins to degrade, likely due to validation overfitting, while HeX-Averaging demonstrates greater robustness at larger ensemble sizes.

5. Discussion

In real-world applications, where computational efficiency and predictive performance are paramount, such as medical imaging and deepfake detection, large-scale models often face challenges. These include high computational demands, long inference times, and a lack of adaptability to varying tasks. This work proposes MobileNet-HeX, a new ensemble model based on Heterogeneous MobileNet eXperts, addressing these limitations by balancing accuracy with computational efficiency. Experimental results across diverse domains demonstrate that MobileNet-HeX consistently outperforms state-of-the-art vision models in accuracy and computational efficiency, particularly on datasets like ISIC 2024 for skin cancer classification and DFDC for deepfake detection.

The ablation study further validates the robustness of the Heterogeneous eXperts method. By examining different ensemble configurations, including HeX-Averaging and HeX-SQP, the results reveal several important findings. For ensembles constructed with a moderate number of expanded models, such as to , the HeX-SQP method consistently delivers superior performance. This range strikes a balance between diversity and overfitting, allowing the selected models to effectively complement one another. However, as the number of expanded models exceeds , the risk of validation overfitting becomes evident. This phenomenon arises when the expanded pool includes models that achieve high validation scores by chance, introducing noise into the ensemble.

The SQP optimization process plays a crucial role in the performance of HeX-SQP. By assigning optimized weights to the selected models, it amplifies their strengths, leading to improved ensemble performance. Nevertheless, this same optimization mechanism can inadvertently magnify the influence of poorly generalized models, particularly when they are selected based on spurious validation success. In contrast, HeX-Averaging, which uses uniform weights, avoids this risk. By not relying on optimization, HeX-Averaging demonstrates greater stability in larger ensembles, as it minimizes the amplification of validation noise.

Clustering, a core aspect of the Heterogeneous eXperts method, proves highly effective in reducing noise by prioritizing heterogeneity over simple validation performance. However, even this approach is not immune to challenges in larger pools. When noisy models with artificially high validation scores are selected as cluster representatives, their overfitting tendencies can propagate into the final ensemble. This issue becomes worse in HeX-SQP, where weight optimization can amplify the influence of these noisy models, resulting in a validation-overfitted final model.

6. Conclusions

This work proposed MobileNet-HeX, a new ensemble framework leveraging lightweight MobileNet architectures to achieve state-of-the-art performance in real-world vision tasks. By combining the efficiency of MobileNet models with a clustering-based heterogeneity-driven selection process, MobileNet-HeX achieves a balance between accuracy, computational efficiency, and robustness. The proposed Expand-and-Squeeze (ES) mechanism ensures diversity in model selection, while sequential quadratic programming (SQP) optimizes ensemble weights for maximum performance. The experimental results across real-world application tasks, including skin cancer classification and deepfake detection, demonstrate that MobileNet-HeX consistently outperforms both SoA vision models and established ensemble methods.

While the proposed model achieves the highest GM on the ISIC 2024 dataset, it does not achieve the highest accuracy. This is expected due to the imbalanced nature of the ISIC dataset, where GM is a more reliable metric for assessing balanced performance across classes. Increasing the number of expanded models (N) has the potential to further enhance performance, as demonstrated by the trends in Figure 2. The DFDC dataset, with its more balanced class distribution and focus on facial analysis, highlights the full potential of the model’s capabilities more effectively, leading to higher overall performance compared to ISIC 2024.

The ablation study highlighted the critical factors influencing ensemble performance. It was observed that the method excels when the expanded model pool remains within a reasonable range ( to ). Beyond this, the risk of validation overfitting increases, as noisy models achieving high validation scores by chance may be selected. Despite this limitation, the clustering-based approach mitigates such risks by focusing on heterogeneity, ensuring that the selected models complement each other in their predictive behaviors.

To further enhance the robustness and scalability of MobileNet-HeX, future work will explore the integration of more comprehensive and rigorous criteria for model selection within each cluster. Instead of solely selecting the top-performing validation model from each cluster, additional filtering mechanisms will be introduced to identify and exclude potentially noisy models. These mechanisms may include robust testing, where candidate models undergo stress tests designed to detect overfitting tendencies. By ensuring that models selected from each cluster generalize well under a variety of conditions, the ensemble can better avoid validation overfitting.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.P. and I.E.L.; methodology, E.P. and I.E.L.; software, E.P.; validation, E.P. and I.E.L.; formal analysis, E.P.; investigation, E.P. and I.E.L.; resources, E.P.; data curation, E.P.; writing—original draft preparation, E.P.; writing—review and editing, E.P. and I.E.L.; visualization, E.P.; supervision, I.E.L., V.T. and P.P.; project administration, I.E.L.; funding acquisition, P.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

ISIC 2024—Skin Cancer Detection with 3D-TBP, https://kaggle.com/competitions/isic-2024-challenge (accessed on 1 October 2024); DeepFake Detection Challenge (DFDC), https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1eqxVwN2LvUsix4AgGX1E8RO9x9hbQslB?usp=sharing (accessed on 1 December 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Patel, A.; Singh, P.; Kumar, R. Deep Learning Using Computer Vision in Self-driving Cars for Traffic Sign Detection. J. Artif. Intell. Inf. 2024, 1, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Pintelas, E.; Livieris, I.E.; Pintelas, P. Adaptive augmentation framework for domain independent few shot learning. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 299, 112047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.K.; Tiwari, S.; Aggarwal, G.; Goenka, N.; Kumar, A.; Chakrabarti, P.; Chakrabarti, T.; Gono, R.; Leonowicz, Z.; Jasiński, M. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer using cascaded ensembling of convolutional neural network and handcrafted features based deep neural network. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 17920–17932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, Q.V.H.; Nguyen, D.T.; Nguyen, D.T.; Huynh-The, T.; Nahavandi, S.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, Q.V.; Nguyen, C.M. Deep learning for deepfakes creation and detection: A survey. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2022, 223, 103525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintelas, E.; Livieris, I.E.; Kotsiantis, S.; Pintelas, P. A multi-view-CNN framework for deep representation learning in image classification. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2023, 232, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radosavovic, I.; Kosaraju, R.P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Designing Network Design Spaces. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 10428–10436. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A ConvNet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 11976–11986. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Z.; Liu, H.; Le, Q.V.; Tan, M. CoAtNet: Marrying Convolution and Attention for All Data Sizes. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2021, 34, 3965–3977. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, C.; Song, S.; Tian, Q.; Huang, G. Computation-efficient deep learning for computer vision: A survey. Cybern. Intell. 2024, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sarmah, U.; Borah, P.; Bhattacharyya, D.K. Ensemble Learning Methods: An Empirical Study. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Li, Y.; Pleiss, G.; Liu, Z.; Hopcroft, J.; Weinberger, K.Q. Snapshot ensembles: Train 1, get M for free. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.00109. [Google Scholar]

- Izmailov, P.; Podoprikhin, D.; Garipov, T.; Vetrov, D.; Wilson, A.G. Averaging Weights Leads to Wider Optima and Better Generalization. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.05407. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R.; Niculescu-Mizil, A.; Crew, G.; Ksikes, A. Ensemble selection from libraries of models. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Machine Learning, Banff, AB, Canada, 4–8 July 2004; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, J.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kuncheva, L.I.; Whitaker, C.J. Measures of diversity in classifier ensembles and their relationship with the ensemble accuracy. Mach. Learn. 2003, 51, 181–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Wyatt, J.L.; Harris, R.; Yao, X. Managing diversity in regression ensembles. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2005, 6, 1621–1650. [Google Scholar]

- Gaudreault, J.G.; Branco, P. Empirical analysis of performance assessment for imbalanced classification. Mach. Learn. 2024, 113, 5533–5575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An Image is Worth 16 × 16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 3–7 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Bojanowski, P.; Caron, M.; Cord, M.; El-Nouby, A.; Joulin, A.; Douze, M.; Synnaeve, G.; Laptev, I.; Schmid, C.; et al. DeiT III: Revenge of the ViT. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, J.; McInnes, L. Uniform manifold approximation and projection. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2024, 4, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Dai, S.; Luo, L.; Zhu, E.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X.; Yao, C.; Zhou, H. Gaussian mixture model clustering with incomplete data. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. (TOMM) 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, E.; Kushwaha, D.S. Clustering cloud workloads: K-means vs gaussian mixture model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragonneau, T.M.; Zhang, Z. PDFO: A cross-platform package for Powell’s derivative-free optimization solvers. Math. Program. Comput. 2024, 16, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M.; Atif, D.; Oliva, D.; Abraham, A.; Ventura, S. Handling imbalanced medical datasets: Review of a decade of research. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Noori Hoshyar, A.; Saikrishna, V.; Firmin, S.; Xia, F. Deepfake video detection: Challenges and opportunities. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtansky, N.; Rotemberg, V.; Gillis, M.; Kose, K.; Reade, W.; Chow, A. ISIC 2024—Skin Cancer Detection with 3D-TBP. Kaggle Competition. 2024. Available online: https://kaggle.com/competitions/isic-2024-challenge (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Dolhansky, B.; Bitton, J.; Pflaum, B.; Lu, J.; Howes, R.; Wang, M.; Ferrer, C.C. The deepfake detection challenge (dfdc) dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.07397. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L.N. Cyclical learning rates for training neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 27–29 March 2017; pp. 464–472. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I. Deep learning. Healthc. Inf. Res. 2016, 22, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Loshchilov, I. Decoupled weight decay regularization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.05101. [Google Scholar]

- Livieris, I.E. A novel forecasting strategy for improving the performance of deep learning models. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 230, 120632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, G.; Zuva, T.; Sibanda, E.M. A review of evaluation metrics in machine learning algorithms. In Proceedings of the Computer Science On-Line Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Pintelas, E.; Pintelas, P. A 3D-CAE-CNN model for Deep Representation Learning of 3D images. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2022, 113, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).