Abstract

Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCMs) are a type of recurrent neural network with built-in meaning in their architecture, originally devoted to modeling and scenario simulation tasks. These knowledge-based neural systems support feedback loops that handle static and temporal data. Over the last decade, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of contributions dedicated to developing FCM-based models and algorithms for structured pattern classification and time series forecasting. These models are attractive since they have proven competitive compared to black boxes while providing highly desirable interpretability features. Equally important are the theoretical studies that have significantly advanced our understanding of the convergence behavior and approximation capabilities of FCM-based models. These studies can challenge individuals who are not experts in Mathematics or Computer Science. As a result, we can occasionally find flawed FCM studies that fail to benefit from the theoretical progress experienced by the field. To address all these challenges, this survey paper aims to cover relevant theoretical and algorithmic advances in the field, while providing clear interpretations and practical pointers for both practitioners and researchers. Additionally, we will survey existing tools and software implementations, highlighting their strengths and limitations towards developing FCM-based solutions.

1. Introduction

Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCMs) [1] originated as an advancement of cognitive maps, transforming a knowledge representation tool with limited capabilities into a versatile reasoning framework. In their canonical form, FCMs provide a tool for modeling complex systems, acknowledging that factors and their interrelationships are not strictly binary or linear in nature. The FCM field is currently actively developing and attracting interest from both researchers and practitioners, as evidenced by the recent publication of several textbooks [2,3].

Many of the initially reported applications of FCMs were devoted to simulation tasks in the realms of social science and psychology to represent and model cognitive processes and decision-making [4]. By the 1990s, FCMs began to be utilized in control systems [5] and complex systems [6] with ambiguous relationships. As the 2000s progressed, their versatility was recognized in the areas of sustainability and environmental modeling [7,8], social sciences [9,10], engineering [11,12,13,14,15], management [16,17,18,19,20], and healthcare [21,22,23,24,25]. FCMs have also been approached from a machine learning perspective, aiding in interpreting and modeling complex data structures and adaptive systems [26,27].

FCMs possess distinct features that make them more desirable than other deep learning models. First, FCMs allow for graded quantification of factors and relationships [28] while providing a graphical representation of the physical system under investigation [29,30]. Second, FCMs can serve as a bridge between technical experts and non-experts. Their graphical nature and ability to capture fuzzy relationships make them accessible for discussions between domain experts, decision-makers, and stakeholders from diverse backgrounds [31,32,33]. Third, FCMs are often considered interpretable due to their transparent structure, where each concept and causal relationship has a well-defined meaning, typically determined by experts. Nonetheless, their dynamic components, such as activation functions and reasoning rules, introduce complexity that can potentially reduce their interpretability. This dynamic nature challenges the assumption that FCMs are always intrinsically interpretable [34,35,36].

Building upon the strengths of FCMs, several extensions of these recurrent neural networks have been proposed in the literature [37]. For example, some works are inspired by extensions of the fuzzy sets theory, such as Hesitant Intuitionistic FCMs [38], fuzzy soft sets FCMs [39], or FCMs with Takagi-Sugeno-Kang fuzzy systems embedded [40]. Further extensions use mathematical frameworks, such as the k-valued FCMs [41] or the gray systems theory, for handling high-uncertainty scenarios [42,43,44]. Another line of studies hybridizes FCMs with other techniques for particular tasks, for example, deep graph convolution enhanced FCMs [45], a large reservoir of randomized high-order FCMs [46,47], community detection and FCMs for time series clustering [48], minimax concave penalty for FCMs in time series forecasting [49], or adding Bayesian methods to identify true causality [50]. Particularly promising is the extension of FCMs to federated learning settings, where the goal is to obtain privacy-preserving and securely distributed models [51,52]. Other studies attempt to correct or improve shortcomings of FCMs without resorting to hybrid models. For example, the revised modeling and simulation FCM methodology [53], which redefines the activation values in terms of quantity changes rather than absolute values.

Numerous papers have highlighted FCMs for their ability to handle ambiguity in designing very complex systems [54], but they are not without criticism. Several bad practices can undermine the effectiveness and reliability of FCMs. Constructing FCMs without involving domain experts can lead to inaccurate representations and the omission of key causal relationships. Arbitrarily assigning weights to the links without a systematic methodology or clear rationale compromises the model’s integrity. Oversimplifying complex systems by ignoring important variables or relationships can render the FCM ineffective, while overcomplicating it with unnecessary details can make it unwieldy and challenging to interpret. Failing to validate and update FCMs periodically, especially when new knowledge or data emerges, makes them outdated or misaligned with reality. Finally, overly relying on FCMs in scenarios where other tools might be more appropriate or ignoring the inherent subjectivity and qualitative nature of FCMs can lead to misguided decisions or conclusions [55]. These open challenges necessitate further research and refinement in the methodology and application of FCMs.

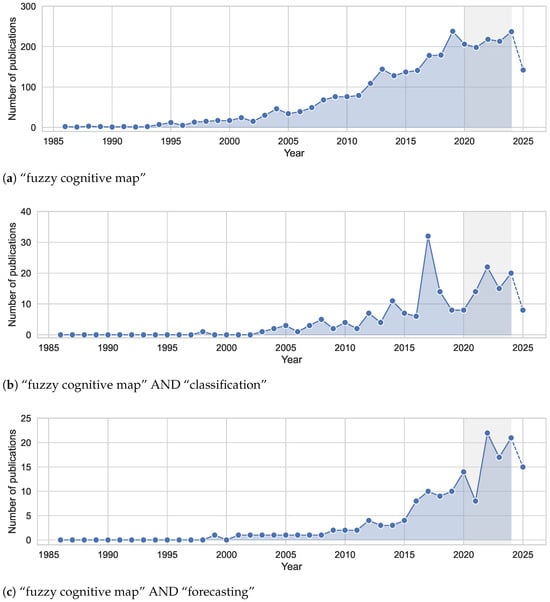

This literature review examines recent advancements in FCMs, with a focus on successful and robust methodologies. Analyzing the evolution of FCMs allows us to outline the field’s progression and the challenges it has faced. In the Appendix A, we summarize the search protocol used in this review, comprising databases, search queries, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the screening process. In Figure 1, we depict the progression of the field based on the count of papers containing keywords related to FCMs in the title and abstracts, dating back to the foundational work of [1]. We can observe an apparent increase in the field’s activity, particularly in conjunction with classification and forecasting tasks, over the last decade.

Figure 1.

For each subfigure, we show the count of articles containing the keywords listed in its caption, either in the title or the abstract of the analyzed papers. Papers published after the foundational work of [1] are considered. The bibliometric data was extracted from https://app.dimensions.ai (accessed on 27 October 2025). For 2025, the statistics are included in dashed lines for the sake of completeness. The period highlighted in gray signals the last five years of publications.

Several review papers played key roles in highlighting recent advancements in the field. In [56], we find an overview of FCM-based time series forecasting models, Jiya et al. [57] presents a summary of learning approaches, Schuerkamp et al. [28] review popular extensions, and in [58] the authors cover aggregation strategies. In contrast, Felix et al. [59] offered an overview of numerous theoretical developments up to 2017. Given the dynamic and interdisciplinary nature of FCMs and the recent advances, this new literature review aims to update the community with consolidations made to the core foundations of FCMs, closing gaps and flaws that have been open for the last few decades. In particular, our review focuses on theoretical and algorithmic studies that have advanced FCMs as classifiers and time series forecasters, primarily over the past five years.

This paper aims to serve as a practitioner-oriented guide to building stronger FCM-based systems. Beyond surveying recent advances, we distill them into actionable design choices and guardrails: a standardized workflow for model construction (from concept elicitation and weight learning to activation and reasoning rules), diagnostic procedures to assess and enforce convergence, criteria for selecting learning families (metaheuristic, regression, and gradient) under data, noise, and compute constraints, and techniques for uncertainty handling, interpretability, and validation. We translate heterogeneous extensions (e.g., time-series forecasting, classification, gray/federated variants, and hybrid graph methods) into conclusions that clarify when each adds value and what trade-offs they impose. The result is a set of prescriptive best practices, a reporting checklist to enhance reproducibility and comparability, and references to available software tools that enable practitioners to transition from ad hoc FCM modeling to robust, auditable pipelines aligned with real-world requirements.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a wrap-up of the different reasoning rules and activation functions utilized when building FCMs. Section 3 is dedicated to analyzing the various scenarios related to convergence (the process by which the system reaches a stable state after a series of iterations). Next, Section 4 analyzes learning methods, subdivided into metaheuristic-based, regression-based, and gradient-based approaches. Section 5 introduces the use of FCMs in time series forecasting problems. Section 6 addresses the adaptation of FCMs for pattern classification. Section 7 groups relevant software tools, libraries, and packages developed to design FCM-based models. Our review then presents our concluding remarks in Section 8.

2. Reasoning Rules and Activation Functions

This section will cover concept elicitation methods, the main reasoning rules, and theoretical results concerning the activation functions of these recurrent neural systems reported in the literature. Before discussing these topics, we will introduce the notation to be used in the paper.

Let N be the number of concepts in the FCM and T the maximum number of iterations, such that is the current iteration. The weight matrix defining the concept interaction is denoted as . The activation vector containing the states of concepts in the current iteration is given by . The activation vector in the t-th iteration is and gives the system state in the current iteration.

The initial activation vector is given by . Therefore, the activation value of the i-th concept in the t-th iteration is such that is the initial activation value of that concept. The weight attached to the edge that departs from the i-th concept and arrives at the j-th concept is represented as . Furthermore, represents the activation function that ensures the activation values of concepts are within the desired interval. Finally, represents the raw activation vector, where is the raw activation value of the i-th concept in the current iteration. In other words, the raw activation vector is the argument of the activation function attached to the reasoning rule.

2.1. Concept Elicitation

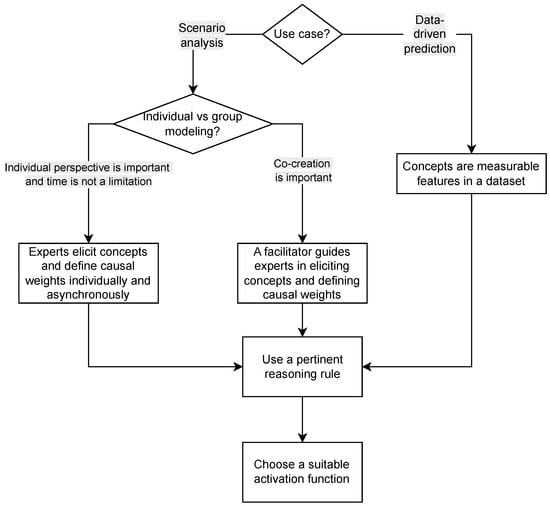

Concept elicitation plays a central role in the construction of FCMs, but the process differs significantly depending on whether the model is developed as a participatory scenario analysis tool or as a data-driven machine learning model. In their original formulation, FCMs were intended as tools for scenario analysis and participatory modeling [53]. Concept elicitation in this context is deeply intertwined with expert knowledge. Domain experts identify the key variables in the system, define the causal relations among them, and agree on the form of the activation function. What-if scenarios are encoded by assigning initial activation values to the relevant concepts, after which the recurrent reasoning procedure is applied to explore the consequences of these hypothetical situations. Knox et al. [32] published a comprehensive guide on eliciting concepts in a participatory setting. According to this paper, the quality of the model depends heavily on methodological choices such as whether concepts are elicited individually or in groups, whether the map is constructed directly by participants or facilitated by a moderator, whether concepts emerge through open-ended discussion, and whether modeling is performed with hand-drawn diagrams or dedicated software. Figure 2 depicts a workflow for building FCM models from historical data or in a participatory modeling setting.

Figure 2.

Workflow for building FCM models.

In contrast, when FCMs are used for tasks such as pattern classification, multi-output regression, or time series forecasting, the concept elicitation process shifts toward data-driven construction [53]. In these settings, concepts may correspond to measurable features in a dataset, and causal weights are learned automatically through dedicated training algorithms (see Section 4). The emphasis is no longer on participatory deliberation but on algorithmic extraction of structure from data. The resulting models often contain many more concepts and connections than expert-generated FCMs, and their interpretability depends on the ability to relate learned concepts and causal relations back to domain-understandable variables.

2.2. Reasoning Rules

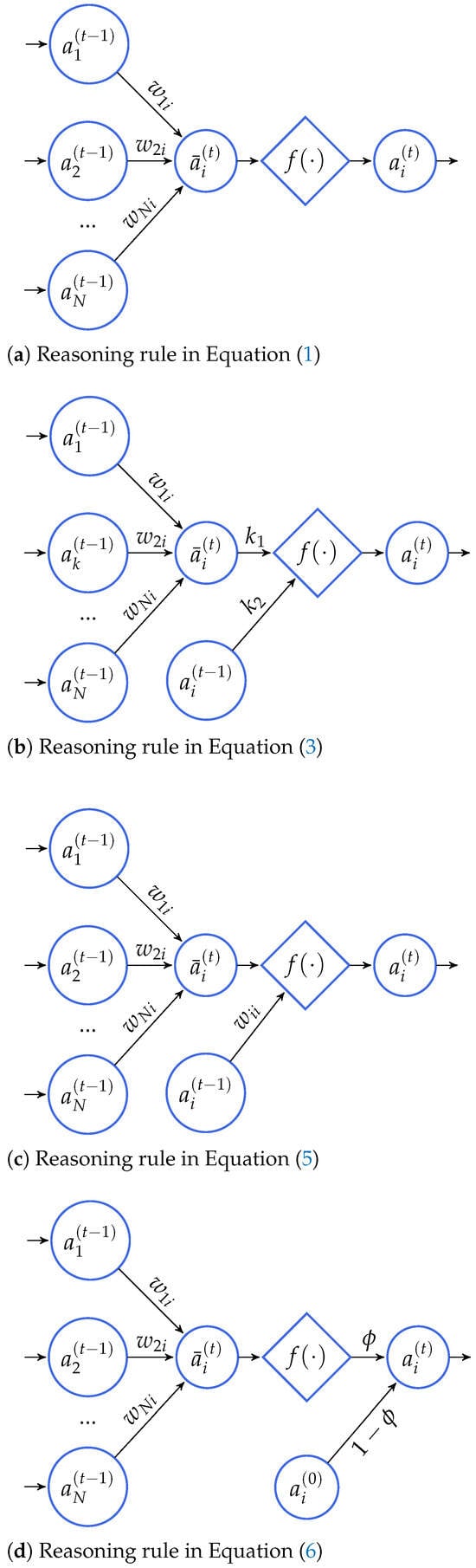

The purpose of reasoning rules of FCM models is to iteratively update the concepts’ activation values given some initial conditions until a stopping criterion is met (see Figure 3). These rules employ three primary components to perform these calculations: the weight matrix, which indicates the connections between concepts, the activation values of concepts from the previous iteration, and the activation function. In this subsection, we will cover three state-of-the-art reasoning rules reported in the literature.

Figure 3.

Reasoning rules for FCM models. In these diagrams, denotes the raw activation value of the i-th concept in the current iteration, just before being transformed with the activation function.

Equation (1) shows the simplest reasoning rule widely employed by researchers and practitioners, which describes a first-order recurrence formula:

being equivalent to

Equation (3) presents an extension of the reasoning rule in Equation (1) such that each concept uses its own past activation value when updating its state [60] in addition to the activation values of connected concepts,

being equivalent to

such that regulates the impact of interconnected concepts on the new value for the i-th concept, while controls the extent to which the previous concept value contributes to the calculation of the new value. The two parameters and must satisfy the equation: .

Hosseini et al. [61] used this extended reasoning rule (with =1) in a hybrid FCM-based solution to estimate air over-pressure due to mine blasting. Similarly, Budak et al. [62] employed this reasoning rule to evaluate the impact of blockchain technology on the supply chain, while the author in [63] utilized this reasoning rule to carry through an FCM-based quality function deployment approach for dishwasher machine selection.

Stylios and Groumpos [60] presented another reasoning rule, especially devoted to FCM-based models, in which self-loops are implicitly allowed:

being equivalent to Equation (2) where has a non-zero diagonal. The reader can note that this reasoning rule is a particular case of Equation (3) where and while dropping the constraint .

This reasoning rule was employed by Qin et al. [64] to develop deep attention FCMs for interpretable multivariate time series prediction, by Yu et al. [65] to develop an FCM classifier based on capsule networks, and by Li et al. [66] to implement an intelligent stock trading decision support system based on rough cognitive reasoning, and by Shen et al. [67] to explore a new research avenue concerning evolutionary multitasking FCM learning.

The crux of these traditional reasoning rules above is that their behavior is fully controlled by the activation function since all modifications happen before the function is applied to the raw activation values. As a result, we obtain models that might suffer from convergence issues while providing limited controllability. Aiming to address both issues, Nápoles et al. [68] proposed the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule depicted below:

being equivalent to

such that is the nonlinearity coefficient. When , the concept’s activation value depends on the activation values of connected concepts in the previous iteration. When , we add a linear component to the reasoning rule devoted to preserving the initial activation values of concepts. When , the model reduces to a linear regression where the initial activation values of concepts act as regressors.

A similar reasoning rule (that excluded the nonlinearity coefficient) was implemented into an FCM-based solution [69] to assess and manage the readiness for blockchain incorporation in the supply chain. In their paper, Nápoles et al. [68] used the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule to quantify implicit bias in pattern classification datasets, while the authors in [70] resorted to this rule to develop a recurrence-aware FCM-based classifier. Similarly, Papadopoulos et al. [71] use it in the context of participatory modeling and scenario analysis for managing Mediterranean river basins.

The reader might reasonably wonder which reasoning rule is recommended when implementing FCM-based models. In that regard, the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule in Equation (6) stands out as the preferred choice based on the following reasons. Firstly, it generalizes the remaining reasoning rules while controlling the relevance of the initial conditions when updating the activation values of the concepts. Secondly, it has appealing convergence properties (discussed in the next section), making it useful for various applications, including scenario analysis, time series forecasting, and pattern classification problems.

Last but not least, we note that a defining property of FCMs lies in recurrent signal processing, where the output passes back to the input until the termination criteria are satisfied. This behavior admits an interpretation as a refinement of the final system response. In that regard, the initial output of the model undergoes correction through a feedback loop. The moderating influence of this feedback depends on the weight values and can lead to distinct attractor regimes, with outcomes that range from irregular dynamics to convergence toward a fixed point. The literature discusses conditions for convergence in specific FCM-based models, for example [72,73,74].

2.3. Activation Functions

The activation function is an essential component in the reasoning rule of FCM-based models. This monotonically non-decreasing function keeps the activation value of each concept within the desired image set I, which can be discrete (a finite set) or continuous (a numeric-valued interval). It should be mentioned that I must be bounded; otherwise, the reasoning rule could explode due to the successive additions and multiplications when updating concepts’ activation values during reasoning. Table 1 portrays relevant activation functions found in the literature.

Table 1.

Main discrete and continuous activation functions are used when implementing the reasoning rule of FCM-based models. For notation simplicity, x represents the concept’s raw activation value in a given iteration.

Overall, continuous activators, such as the sigmoid, the hyperbolic tangent, and the rescaled activation functions, are often preferred since they provide greater expressiveness. Actually, the study in [76] advocated for using the sigmoid activation function when modeling scenario analysis problems over the hyperbolic tangent and threshold functions. However, the rescaled function requires further study and comparison with other functions in terms of their approximation capabilities and expressiveness.

3. Convergence Analysis and Theoretical Studies

As for the stopping criteria, the reasoning rules stop when either (i) the model converges to a fixed point or (ii) a maximal number of iterations T is reached. Overall, we have three possible states:

- Fixed point : the FCM produces the same activation vector after , implying that a fixed point was found. As a result, .

- Limit cycle : the FCM produces the same activation vector with period P, thus , where .

- Chaos: the FCM produces different activation vectors for successive iterations, which makes decision-making difficult.

It is worth noting that fixed-point attractors can be categorized into two main types: unique fixed points and multiple fixed points. If the fixed point is unique, then the FCM model will produce the same solution regardless of the initial conditions. The FCM model can create multiple solutions if multiple fixed points exist. Two seminal theoretical results concerning the convergence of FCM models to unique fixed points paved the road for recent developments.

The first of these theoretical results was introduced by Boutalis et al. [79] and concerns two theorems (see Theorems 1 and 2) on the stability of sigmoid FCMs. While the first theorem focuses on FCM models without inputs, the second assumes that some concepts influence others but are not influenced by any other concepts. In both cases, the theorems provide conditions related to the existence and uniqueness of the fixed-point attractors.

Theorem 1.

There exists one and only one solution for any activation value of any sigmoid FCM if the following expression holds:

Theorem 2.

For a sigmoid FCM with M input concepts, there exists one and only one solution for any activation value if the following expression holds:

We recognize these theorems as the first successful attempt to determine mathematical conditions related to the existence and uniqueness of fixed points of FCMs using the sigmoid activation function with . Kotas et al. [80] attempted to generalize these theorems for arbitrary sigmoid functions, allowing the inclination parameter to vary. Although their approach was initially accepted by the community and cited several times (for example, in the previous review paper by [59]), it was ultimately refuted by numerical counterexamples in [81]. Harmati et al. [82] correctly generalized these theorems for arbitrary values, as Theorem 3 shows. Moreover, they extended the analysis to FCM models that utilize the hyperbolic tangent function and examined the case of FCMs equipped with non-negative weight matrices, applying Tarski’s fixed-point theorem.

Theorem 3.

Let be the extended weight matrix of an FCM, and let be the parameter of the log-sigmoid activation function. If the inequality

holds, then the FCM has one and only one fixed point. In the formula, refers to the Frobenius norm of the matrix, i.e., .

The second seminal theoretical result concerning the existence and uniqueness of the fixed point was presented in [83], where the authors proved that the slope of the activation function determines the number of attractors in a sigmoid FCM (see Theorem 4). From an analytical viewpoint, this theorem could be considered a variation of Theorems 1 and 2. However, Theorem 4 focuses on the properties that the sigmoid activation function must satisfy for the map to be linearly stable.

Theorem 4.

The number of fixed points of a sigmoid FCM model depends on the slope λ of the activation function.

- (a)

- If is sufficiently small, then the map will have a unique solution, and this solution will be linearly stable.

- (b)

- If is sufficiently large, then the map will have multiple solutions, and many of these solutions can be linearly stable.

Knight et al. [83] mathematically defined bounds to elucidate what is considered “small enough” in Theorem 4, removing all sources of ambiguity.

Theorem 5.

For and h given, the sigmoid FCM has a unique fixed point for all λ such that , this fixed point is stable.

where are the binomial coefficients, and is given by the recursion relation .

Recently, Harmati et al. [81] improved the above analytical results. Concerning the results presented by Boutalis et al. [79] extended in [82], they explained that we could find a matrix norm , such that . The ramification of this remark is that the global convergence to a unique fixed point is proved for a larger set of values. Concerning the results in Knight et al. [83], they provided more realistic bounds to define what is considered “small enough", as formalized in the theorems below.

Theorem 6.

Consider a sigmoid FCM with weight matrix and sigmoid parameter λ. If , then the FCM has a unique and globally asymptotically stable fixed point.

Theorem 7.

Let be defined as in Theorem 5. Then, the inequality holds for every .

Such an upper bound is easier to compute while ensuring the uniqueness of fixed points for a larger set of values. The authors also stated that no better upper bound can be estimated by using a different norm. However, their method is flexible enough to increase the upper bound provided, allowing for more information about the weights to be available. Harmati et al. [81] also discussed the superiority of their approach when compared with the Lyapunov stability analysis conducted by Lee et al. [84].

While these analytical results have enhanced our understanding of the convergence properties of FCM models, the practical usability of the unique fixed point is limited. In other words, FCM models converging to a unique fixed point are unsuitable for performing what-if scenario analysis or solving prediction problems (such as regression, time series forecasting, or pattern classification). The authors in [85] first discussed this issue and experimentally illustrated how an FCM-based classifier will only recognize a single decision class when the model converges to a unique fixed point. Harmati et al. [81] also provided a clear statement about this issue, which reads as follows: “The results presented in this paper can be used in at least two different ways: in some applications, a unique fixed point is a required property of the model. It means that different initial stimuli should lead to the same equilibrium state. On the other hand, there are applications (for example, pattern recognition) where the FCM should have more than one equilibrium point. In other words, global stability is a required property in the first case, while in the second case, we should avoid globally stable models. The simple analytical results help FCM users decide about some model parameters before evaluating the full model, decreasing the number of trial-and-error simulations.”

In [86], the authors proposed a mathematical formalism to study the effectiveness of learning algorithms devoted to improving the convergence properties of FCM models. In that regard, the authors introduced the concepts of E-stability and E-instability along with sufficiency conditions for these properties.

Definition 1.

We say that an FCM, where the i-th concept uses the sigmoid activation function , is E-accurate in the t-th iteration if each concept is -accurate, where and . Moreover, a sigmoid concept is deemed accurate ξ-accurate in the t-th iteration if , where .

Definition 2.

We say that an FCM, where the i-th concept uses the sigmoid activation function , is E-stable if such that , where and . Otherwise, the FCM is said to be E-unstable.

Remark 1.

The previous definitions (and consequently the theorems below) hold for a collection of initial activation vectors used to start the recurrent reasoning process. However, we decided to omit the subscript indexing the initial activation vectors to lighten the notation.

Theorem 8.

(Sufficiency Condition). A sigmoid FCM will be E-stable if the following conditions are simultaneously satisfied:

- (a)

- (b)

- such that the FCM is E-accurate in the -th iteration

where

and represents the i-th row of the weight matrix, is the vector of expected responses for a given initial activation vector, with , and and are defined as follows:

Theorem 9.

(Sufficiency Condition). A sigmoid FCM will be E-unstable if the following condition is satisfied:

where

Remark 2.

Similarly, to Theorem 8, and define the interval in which varies. If , then the FCM with will not be E-accurate in the -th iteration, and therefore, it cannot be E-stable.

The authors in [86] also proposed sufficient conditions for FCM-based models where and . The ramification of these analytical results is that algorithms devoted to improving the convergence properties of FCM models a posteriori [85] have limited effectiveness if no modifications are made to the weight matrix.

The study in [87] proposed another mathematical framework to study the dynamic behavior of FCMs with monotonically increasing functions bounded. They proved that the state space of an FCM shrinks infinitely and converges to a so-called limit state space, which could be a fixed-point attractor. In that regard, we can determine whether the fixed-point attractor will be unique or not. The relevance of this result is that we can determine the feasible activation space of each concept in advance, regardless of the initial activation vectors. Moreover, the fact that the feasible activation space of a neural concept is smaller than the theoretically possible activation space indicates that values outside the feasible activation space will never be reached. Later, Concepción et al. [88] extended these results to quasi-nonlinear FCM models.

These bounds enable practitioners to design realistic decision support systems or predictive models, as most real-world applications must avoid unique fixed-point attractors. In this regard, Nápoles et al. [68] introduced a theorem that gives conditions (related to the nonlinearity coefficient) for which the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule in Equation (7) will never converge to a unique fixed-point attractor. Following a different research direction, the authors in [89] used these analytical lower and upper bounds to design a supervised learning algorithm that does not require any training data.

Theorem 10

(Injective convergence). In an FCM model using Equation (7), when , there are not two different initial activation vectors leading to the same fixed-point attractor.

If the coefficient is set to 1.0, the convergence behavior of the FCM will depend on the activation function. For example, suppose we adopt the rescaled activation function. In that case, the model will undoubtedly converge to a unique fixed-point attractor provided that (i) the transposed weight matrix has an eigenvalue that is strictly greater in magnitude than other eigenvalues, and (ii) the initial activation vector has a nonzero component in the direction of an eigenvector associated with the dominant eigenvalue.

The literature reports other studies concerning the convergence of Fuzzy-Rough Cognitive Networks [90,91], the algebraic dynamics of k-valued FCMs [92], or the behavior of gray or interval-valued FCMs [73,74,93]. However, this section does not describe these studies in detail, since they focus on FCM extensions with specific topologies and knowledge structures. Concerning algorithmic approaches, [72] employed supervised and unsupervised learning to improve the model convergence for operational risk assessment in power distribution networks.

Convergence Analysis Illustration

An inspection of the literature reveals that the sigmoid activation function is the preferred choice among practitioners and researchers alike when designing FCM-based models. After all, previous benchmarking studies [75,76] claimed its superiority over other activation functions such as binary, trivalent, or hyperbolic tangent functions. However, only a few studies [53,85,94] have discussed the risks posed by the sigmoid function when it comes to the system’s convergence to unique fixed-point attractors. We must emphasize that these invariant equilibrium points render the FCM model ineffective for performing any simulation or predictive task and must be avoided at all costs.

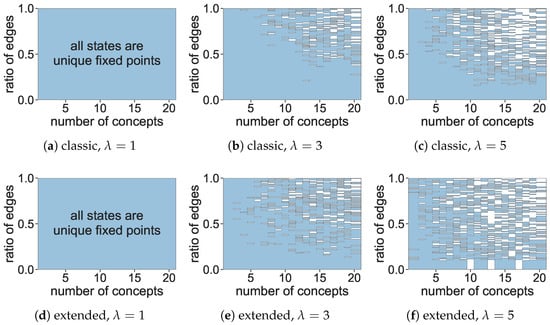

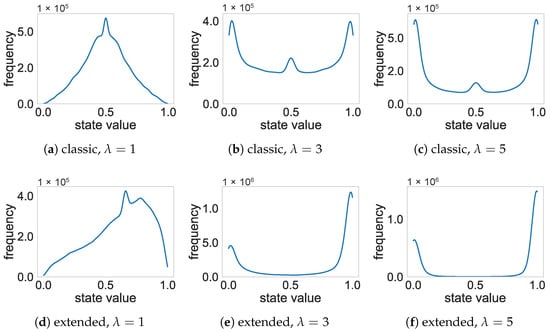

This subsection presents two hypotheses that are empirically investigated. First, we conjecture that any FCM model using the reasoning rules in Equations (1) and (3) and the sigmoid function with will converge to a unique fixed point. Second, we hypothesize that increasing the value will help escape from the unique fixed point for larger, more densely connected FCMs at the expense of biasing the neurons’ activation values toward the extremes of the activation interval.

Aiming to investigate our hypotheses, we first generated 10,000 networks such that the number of concepts is and the number of edges is , which translates into a ratio of edges ranging from 0.1 (simulating sparse models as the one for scenario analysis) to 1.0 (simulating dense models as the ones used for prediction tasks). The main diagonal of these weight matrices was filled with zeros to avoid explicit self-loops and the remaining non-zero elements were given by under the assumption that . In addition, for each FCM model, we generated 100 initial activation vectors, such that . In the simulation step, we applied both reasoning rules to each model using the randomly generated initial conditions while varying the parameter from 1.0 to 5.0, totaling 10 million simulations. In all cases, the maximal number of iterations was set to . Concerning convergence, we say that the fixed point is unique for a given model if such that and denote the final activation vectors obtained for the i-th and j-th initial activation vectors, respectively.

Figure 4 depicts the unique fixed-point attractors produced for both reasoning rules and different values when increasing the number of concepts and the ratio of edges. In this figure, the white spaces correspond to multiple fixed points, limit cycles, and chaotic states.

Figure 4.

Unique fixed points for different settings.

The simulations indicate that all models converged to a unique fixed point when for both reasoning rules. This result is concerning since such a parametric setting is the default setting in FCM research, thus leading to models with no simulation or predictive capability. Increasing the value helps alleviate this issue to some extent. However, regular-sized FCMs (i.e., with less than 10 concepts) having connectivity up to 50% will be at risk of converging to a unique fixed point when using the classic reasoning rule. In contrast, the extended reasoning rule seems to be less likely to produce invariant fixed points for larger values.

Figure 5 shows the distribution of concepts’ activation values in the last iteration when using different reasoning rules and values. These results reveal why using the extended reasoning rule and large values is not generally advised, even when they help the FCMs escape from unique fixed points. Firstly, this reasoning rule is biased toward producing larger activation values compared to the classic rule, since smaller values are less likely to be produced. Secondly, larger inclination values cause the function to behave like a quasi-binary activator, which translates into a significant loss in precision. Moreover, the fact that these final activation values are not uniformly distributed for any of these settings suggests that the FCM models might struggle to approximate any value in the activation interval. In that regard, using unbounded weights could lead to better results.

Figure 5.

Distribution of activation values for different settings.

These experiments made clear that the classic and extended reasoning rules coupled with the sigmoid activation function (using ) should not be used and that larger inclination values might still lead to unique fixed points. Hence, it would be useful to derive a mathematical tool to determine whether an FCM model will converge to a unique fixed point based on the weight matrix only, regardless of the initial activation vector. To do that, we will rely on the theory presented in Concepción et al. [87] to describe the feasible activation space of each neural concept.

Let be the feasible activation space for the i-th neural concept when starting the recurrent reasoning process, where and represent the lower and upper bounds, respectively. To derive the feasible activation space associated with the i-th neural concept in the -th iteration, we will assume that is a continuous, bounded, non-negative, and monotone-increasing activation. The sigmoid activation function addressed in this note fulfills these properties. Afterwards, we need to calculate the minimum and maximum bounds for the dot product , as formalized below:

such that and represent the bounds (infimum and supremum, respectively) of the closed interval attached to the j-th neural concept. Therefore, it holds that Inductively, we can compute and as indicated below:

At the model level, the Cartesian product of all these feasible activation spaces creates a feasible state space at the -th iteration. Therefore, we can confidently conclude that the FCM model will converge to a unique fixed point if regardless of the concepts’ initial activation values.

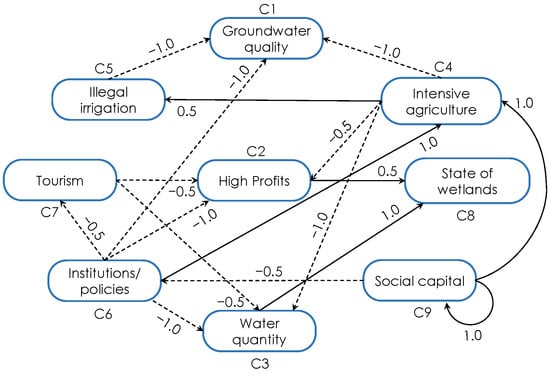

Aiming to illustrate the usability of this formalism, let us compute the lower and upper bounds for each neural concept in the FCM model introduced in [95]. Figure 6 shows this model, which involves 17 relationships, from which 6 are positive (solid lines), and 11 are negative (dashed lines). In this case, the network density is 21%, which indicates that the weight matrix has 17 out of 81 non-zero causal relationships.

Figure 6.

FCM model for European freshwater resource development.

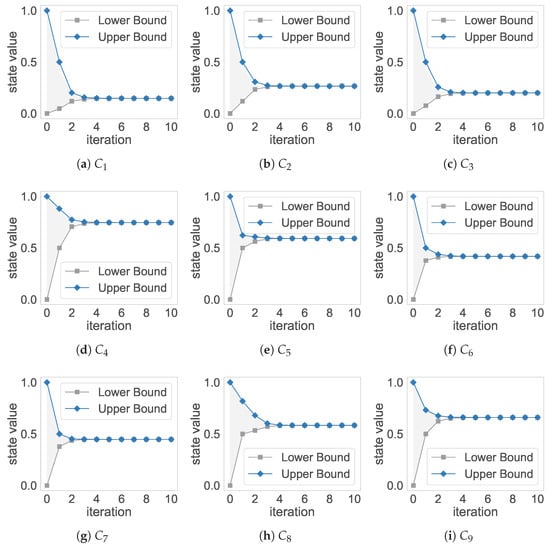

Figure 7 depicts the concepts’ lower and upper bounds in each iteration. These bounds indicate that the FCM will always converge to a unique fixed point regardless of the initial activation vectors.

Figure 7.

Lower and upper bounds for the neural concepts in the European freshwater FCM model. After five iterations, the model converged to a unique fixed point since for all i and all .

This subsection highlights significant issues with using the sigmoid activation function in FCM-based models, particularly concerning the convergence to unique fixed-point attractors. Our findings strongly suggest that neither the classic nor the extended reasoning rules must be used together with the sigmoid activation function with . In case this combination would be nonetheless used for larger values, we described a mathematical formalism to determine whether a particular FCM model will converge to a unique fixed point, irrespective of the initial activation vector. Alternatively, we strongly recommend utilizing the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule, which is compatible with any activation function, including the sigmoid, and does not produce unique fixed-point attractors.

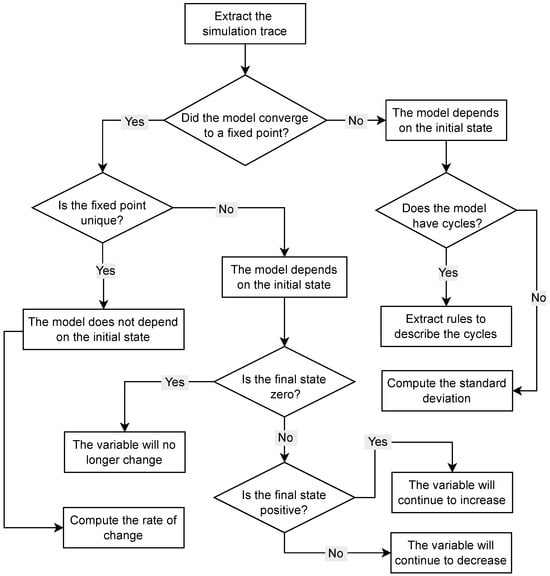

Another alternative is to resort to the neural cognitive methodology presented in [53], where activation values denote quantity changes rather than absolute values. Figure 8 shows a flow diagram depicting how to interpret the simulation results in the presence of different convergence behaviors.

Figure 8.

Workflow for interpreting FCMs simulation results in terms of increase and decrease of variables, in relation to different convergence scenarios [53].

The reader can note that such a methodology covers all dynamic cases, including meaningful interpretations of unique fixed-point attractors.

4. Learning Algorithms and Taxonomy

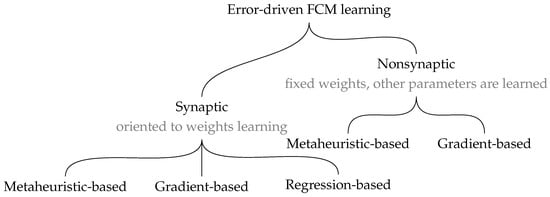

The literature on learning algorithms for FCM-based models is rich and sometimes disorganized. Our study of the current approaches has led us to propose a taxonomy of the existing error-driven FCM learning strategies (see Figure 9). According to the target learnable parameters, existing algorithms can be gathered into two broad categories: synaptic and nonsynaptic. Synaptic learning is oriented toward fitting the weight values that characterize the relationships between neural entities. Nonsynaptic learning utilizes previously defined weights and adjusts other model parameters, including the activation functions and network topology. Later subsections address prominent learning algorithms used for both synaptic and nonsynaptic learning.

Figure 9.

Error-driven learning of FCM models. The plot illustrates the division of current FCM learning techniques.

More explicitly, we will cover metaheuristic-based algorithms (both standard methodologies and recent methods) and some relevant objective functions that drive the search process. Moreover, we will cover regression-based and gradient-based algorithms, which are deemed a new generation of learning algorithms for FCM-based models.

4.1. Metaheuristic-Based Learning Algorithms

A significant body of research on FCM construction employs metaheuristic approaches to compute the weight matrix and, when applicable, optimize additional parameters [96]. Firstly, let us briefly emphasize that metaheuristic optimization aims to identify a solution to a problem that meets a “sufficiently good” criterion. This criterion is typically measured using an objective function. Importantly, there is no guarantee of discovering an optimal solution. Nevertheless, in many engineering applications, such an assumption proves satisfactory in yielding effective solutions. The research community has rapidly embraced the simplicity of this practical goal, resulting in the development of numerous algorithms that align with this rationale.

While heuristic methods have been in use for over 20 years, as indicated by the early approaches [97], studies continue to employ these methodologies without significant modification. The three key categories of well-studied heuristic methods in FCM development include (i) Genetic Algorithms (GAs), (ii) other evolutionary algorithms, and (iii) swarm-based methods such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and others.

In the following subsection, we will discuss relevant approaches to metaheuristic-based learning of FCM models used in studies from 2016 to 2023. Whenever opportune, we will include papers that extend beyond this time period to ensure completeness in our review.

4.1.1. Standard Methodologies Used up to This Day

One renowned “old” methodology in contemporary literature is rooted in the GA paradigm, as discussed by Hoyos et al. [98]. Typically, the model’s structure aligns with a basic FCM model, akin to the method by Altundoğan and Karaköse [99]. Nevertheless, other FCM extensions have also been referenced. For example, Hajek and Prochazka [100] employed interval-valued FCMs combined with genetic learning to predict corporate financial distress. Other approaches move beyond prediction tasks, such as the study delivered by Rotshtein et al. [101], who focused on conducting “what if" scenario analysis in an FCM-based model of the Ukraine-Russia war. Earlier studies include applications such as computer-aided medical diagnosis [102].

The second category of heuristic searches, introduced at the beginning of studies on FCM data-driven development and still in use in an unchanged form, comprises other evolutionary approaches. For example, a study by Hosseini et al. [103] utilized a Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm. Additionally, new variants of this approach are available for exploration. Specifically, Bernard et al. [104] employed an evolutionary algorithm called the Covariance Matrix Adaptation-Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES). Chi and Liu [105] used a Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithm (MOEA) to learn FCM models, while Shen et al. [67] utilized a memetic algorithm.

The third group of approaches that has withstood the test of time concerns swarm-based methods. A prominent example in this category is PSO, which served as the foundation for a method presented by Hajek and Prochazka [106] for Interval-valued FCM (IFCM) learning. Mendonça et al. [107] employed the well-known Ant Colony Optimization (ACO), while Baykasoğlu and Gölcük [108] utilized the Jaya algorithm, a population-based method recently developed by Rao [109]. Wang et al. [12] leveraged the Adaptive Glowworm Swarm Optimization (AGSO) method to determine concept weights. Their approach assumed an online mode for updating weight values. Dutta et al. [110] applied Cat Swarm Optimization for soil classification using an FCM model. Unfortunately, as Ahmed et al. [111] have concluded, this search method tends to converge to local optima, resulting in sub-optimal solutions. More recently, [112] proposed the use of a niching-based artificial bee colony optimization algorithm for learning high-order FCMs.

4.1.2. New Heuristic Methods for FCM Learning

The domain of FCMs has also inspired the development of new heuristic searches devoted just to this model. The usual methodology assumed in such studies is that an author takes a well-known algorithm and adapts it to some extent to produce well-working FCM models.

For example, Yang and Liu [113] proposed a multi-agent GA that uses the convergence error to guide the search. The same research team later fused the multi-agent GA with niching methods [114]. This method was further modified, resulting in the dynamical multi-agent GA variant, which is touted as particularly effective for large-scale FCMs with up to 500 concepts [115]. Wang et al. [116] have also addressed the issues of learning large-scale FCM-based models and developed an evolutionary many-task algorithm specifically for this purpose. Yang et al. [117] combined the FCM formalism with boosting and developed a real-coded GA with an improved mutation operator. Yet another method derived from GA was introduced by Poczęta et al. [118]. This method is based on system performance indicators and uses a fusion of an elite GA and Individually Directional Evolutionary Algorithm (IDEA). Poczęta et al. [119] also proposed a Structure Optimization GA (SOGA) for FCM learning in the context of multivariate time series.

The next group of new methods, built based on evolutionary algorithms, includes not only the approach by Yastrebov et al. [120]. These authors employed an enhanced multi-objective IDEA method. Later improvements of this approach incorporated the clustering step and were described in [121]. The same team proposed another new evolutionary algorithm for FCM learning, which allows the selection of key concepts based on graph theory metrics and determines their connections [122].

Swarm-based approaches were also being extended to new variants dedicated to FCMs. Liang et al. [123] proposed an improved multifactorial PSO learning algorithm termed IMFPSO. This method was developed to handle non-stationary and noisy time series. PSO was also modified by Mital et al. [124] in a risk management case study. Mythili and Shanavas [125] proposed a new learning method termed MEHECOM based on clustering. This method, however, is a pipeline of well-known approaches.

To summarize the algorithms mentioned in this section, they can be relatively easily adapted to various data processing tasks with FCMs. Unfortunately, the domain of generic approaches to heuristic FCM optimization failed to evolve towards standardized testing scenarios for the developed algorithms. The domain is rich in new approaches and is on par with the development of generic heuristic optimization algorithms. As Alorf underlined [126], 57 novel metaheuristics were published between 2020 and 2021. It amounts to a vast pool of available methods that continues to grow. All these algorithms have the potential to be adapted for use in FCMs. However, the issue remains how to evaluate the usefulness and value added by new methods. We observe a strong trend toward standardization of testing scenarios across various machine learning domains. This is evident first and foremost in the use of the same benchmark datasets, which serve as a basis for method comparisons. The second trend is the development of uniformly adapted testing scenarios, which is relevant when deploying the developed models in real-world settings.

4.1.3. New Heuristic Methods with Advanced Roles

In this section, we discuss newly developed heuristic FCM development methods designed to handle specific data analysis tasks. Their level of specificity is high, and transferring these approaches to other domains would require more substantial interventions.

Rotshtein et al. [127] developed an FCM model with a dedicated learning algorithm using a GA-based optimizer. The novelty of the method lies in the fact that it starts with expert-given values of the weights. The intervals of acceptable weight values govern the entire model. The fitness criterion is the sum of squares of deviations of the custom measure of reliability. Duneja et al. [128] proposed a new learning scheme in which GA updated FCM weights based on activation values that were preprocessed by a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) neural network. However, this study failed to clearly explain the benefits of such an advanced processing pipeline.

The literature on FCM-based methods presents a range of studies specifically focused on reconstructing Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs). The primary challenge of the GRN reconstruction problem is its size and complexity. Thus, the FCM model and its training routines had to be adapted to handle unusually large and sparse weight matrices. The research team of Liu et al. [129,130,131] has devoted substantial efforts to tackling this practical problem. This has led to the development of several heuristic training techniques. For instance, in [129], a method utilizing a dynamic multi-agent GA was adopted. In [130], a multi-agent GA was fused with a random forest. In [131], a multi-agent GA was employed in conjunction with a multi-objective evolutionary algorithm. Shen et al. [132] developed an approach to GRN reconstruction with a dual objective function that minimizes the error and the number of nonzero entries [132]. Later, the same team adopted a decomposition strategy to learn large-scale FCMs for GRNs. The memetic algorithm was used to train the model [67]. Nevertheless, it is essential to acknowledge that the five revised papers on GRNs present very similar concepts at the conceptual level, leading to some redundancy in the addressed techniques.

Among studies focusing on recent advances in heuristic-based learning, we highlight the method by Altundoğan and Karaköse [133]. Their method utilizes a PSO-based optimizer to fine-tune the parameters of a dynamic FCM model. Another noteworthy study by Mls et al. [134] addressed incompleteness and uncertainty in expert evaluations of weight matrices. The authors employed expert-driven optimization and heuristic adaptation based on the Interactive Evolutionary Computing (IEC) technique for solving the learning task in their study.

Lastly, the literature includes comparative studies examining the practical effectiveness of metaheuristic approaches. For example, Cisłak et al. [135] conducted an empirical study comparing Artificial Bee Colony (ABC), Harmony Search (HS), Improved Harmony Search (IHS), DE, GAs, and PSO. In a more theoretical exploration, Jiya et al. [57] examined the properties of selected heuristic methods in the context of FCM learning.

4.1.4. Objective Functions Used in FCM Construction with Metaheuristics

An essential element in FCM learning is selecting an error measure that controls the training process. For example, it can be generally assumed that each concept generates a prediction for a given problem instance, which is then compared with the expected prediction value. This comparison yields an error, and the optimization procedure adjusts the learnable parameters to minimize this error. The algorithm calculates the error over the entire training dataset to optimize a given model. Such a formulation of the training procedure can be adapted for both forecasting and classification problems. The distinction lies in the interpretation of the prediction error.

The literature provides a collection of well-known error measures for operating with numerical values, as also used in recent studies, such as Mean Squared Error (MSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), among others.

A straightforward extension of basic error functions involves incorporating additional parameters to either diminish or accentuate outputs from specific concepts, thus leading to a weighted error function. This formalism was adopted by Poczęta et al. [136] as shown below,

where is a parameter specifying concept importance. A similar formula was given by Yastrebov et al. [120].

Wang et al. [116] employed a concept-specific error measurement that minimized the error of each concept separately (in a parallel manner). Equation (13) expresses a decomposed error term denoted as , , which is associated with the error of the i-th concept,

A dual objective function was utilized by Chi et al. [105] and Hosseini et al. [103]. While the first objective focused on the MSE value, the second focused on the network density (i.e., the number of nonzero weights). These objectives are encoded in a vector as follows:

We can incorporate a metric related to matrix sparsity as an additional quality criterion into the objective function. A connection with a zero value between two concepts is interpreted as the absence of a relationship. A concept that exerts no influence on any other concepts is considered redundant. Consequently, this approach enables us to regulate the model, reducing both its size and complexity. Regularization is particularly beneficial when addressing problems characterized by a large number of features.

Two approaches to FCM construction consider both the prediction error and model architecture. The first approach involves applying an inherently multiobjective learning algorithm. For example, Shen et al. [67,132] used this solution in their studies on reconstructing a gene regulatory network. The objectives are formalized below:

where is the L0-norm of the weight vector representing the incoming connections to the i-th concept.

The second approach is constructing an objective function containing two components: prediction error and model shape evaluation. Poczęta et al. [118] and Yastrebov et al. [120] delivered a couple of solutions following this rationale. The model’s shape is typically evaluated based on the number of zero weights (the more, the better) and the absolute value of the weights (the higher, the better). A general formula that summarizes a multi-objective error () function of this sort is given as follows:

where gives the prediction error computed as a difference between expected outcomes and predictions produced by the model (). Moreover, stands for the density of the weight matrix (the higher, the worse), while symbolizes weight quality. Particular implementations often omit the function and focus just on zero-valued weights. In this formula, ⊕ is an operator that joins the specific components of the formula (e.g., the sum operator). Finally, , and are parameters that can be used to obtain a formula with specific theoretical properties.

Further extensions of this idea were delivered by Poczeta et al. [118]. In this work, they presented the following objective function:

where represents the prediction error given by Equation (12), , , and . In this equation, are parameters such that . The authors introduced the consonance notation as the influence between the j-th concept and the i-th concept, which is defined as . Values v are computed using an intermediate matrix V that measures pairwise relations between concepts based on maximal values of weights. The consonance measure takes values in the interval. Moreover, is the number of consonances of influence between concepts with values greater than 0.5, is the number of weights with absolute values greater than 0.5, and is the number of nonzero weights. This combination of factors was designed to strike a balance between modeling accuracy, density, and the significance of the weights.

The predecessor of the objective function specified in Equation (17) was presented in [137], which is depicted below:

such that , and add up to 1.

Lastly, let us mention the objective functions used in studies on regression mechanism-based FCM model construction procedures. The first formalism we want to recall was proposed by Xia et al. [138]. Their objective function can be formalized as follows:

where and are parameters that are estimated with supplemented formulas. Subsequently, we shall mention the formula given by Shen et al. [139]:

where is a parameter to be specified by the user. The optimization algorithm used with this formalism is Elastic Net. When , the method employs LASSO regularization, and when , it reduces to ridge regression. plays the role of penalty parameter. Hence, the solution to this problem is a penalized least squares method.

The observed trend indicates an expansion of plain data error-based objective functions to optimize FCM architecture concurrently. Moreover, we observe their adaptation to align with contemporary data analysis methods, including parallel and multiobjective approaches.

4.1.5. Nonsynaptic Learning with Metaheuristics

It should be noted that the methods based on metaheuristic optimization reviewed to this point are primarily devoted to synaptic learning. Regarding recent nonsynaptic approaches, it is no surprise that the literature in this domain is sparse compared to that related to synaptic learning. Nonetheless, we shall note a few relevant studies. In particular, Nápoles et al. [85] addressed convergence issues of FCMs with sigmoid activation functions in a nonsynaptic learning setup. The rationale behind this learning algorithm was to enhance the FCM’s convergence by fine-tuning the sigmoid function parameters while maintaining the weights unchanged. Papageorgiou et al. [140] introduced a new approach to FCM construction that includes a concept reduction step. Their study, however, was focused on relatively small models. Hatwagner et al. [141] also addressed map architecture optimization problems in a non-synaptic learning setup. They introduced a two-stage model reduction technique based on clustering. In these studies, nonsynaptic learning was used to compensate for the network modification resulting from the reduction operation.

4.2. Regression-Based Learning Algorithms

Regression-based methods were widely used in an earlier era of neural network research (to the extent that a significant class of Kohonen-type linear associative memories were known as pseudoinverse ANNs [142]). The rationale relies on the solution to the network weights being the same as that which would be calculated by singular value decomposition. For example, in [143] the authors developed a dynamic time series model where each iteration was associated with a weight matrix computed using the Moore–Penrose (MP) inverse, also known as the pseudoinverse.

In [144], the authors presented a hybrid FCM model that mines the weights from the historical data by applying the MP inverse. The procedure is fast and deterministic since the weights are produced via matrix multiplication. The architecture of this model involves a weight matrix , which contains the interactions between input concepts as defined by the expert, and another weight matrix that connects the input concepts to the output ones. The learning process focuses on computing from the data.

Let be an matrix containing the final activation values of input concepts after performing T iterations of the FCM inference process on the input matrix , as seen below, where M is the number of input concepts and K is the number of training instances,

The learning procedure shown in Equation (21) computes the weight matrix without the need to perform multiple reasoning passes or iterations,

such that stands for the MP inverse of a given matrix, while the output to be approximated is given by:

The target output is represented by a matrix containing the inverse of the sigmoid activation functions attached to output concepts, such that and are the lower and upper activation values of the i-th concept, while and are their sigmoid function parameters:

One observation is that weights might lie outside the typical interval, which is sometimes a desired property of FCM models. To overcome this issue, the authors in [144] proposed a post-optimization procedure to normalize weights to the interval.

In [70], the authors introduced a powerful recurrence-aware neural classifier involving two building blocks. The first neural block consists of a Long-term Cognitive Network (LTCN) model, where each concept denotes a problem feature. The model uses the reasoning rule in Equation (7), which involves a parameter to control nonlinearity. The second neural block connects the input concepts with the decision concepts. Equation (23) displays the unsupervised learning rule used in the first neural block to compute the i-th column of the weight matrix and the bias connected to the i-th input concept in the network,

where is the i-th column of the training set and is a matrix that results after replacing the i-th column of with zeros and concatenating a column vector full of ones. Those weights correspond to the coefficients of M regression models, such that is deemed the target variable of the i-th model.

The model uses a recurrence-aware sub-network that connects each temporal state with the decision concepts. This sub-network uses all states resulting from the recurrent reasoning rule for a given instance. Equation (24) computes the activation values of output concepts used to produce the decision class for the given instance,

where denotes the prediction for the k-th training instance, is the outer weight matrix connecting the temporal states (including the initial state) with the M decision concepts, while is the bias weight vector attached to decision concepts. The learnable matrices and will be computed from historical data during the supervised learning step. In this formulation, represents a matrix resulting from the recursive horizontal concatenation of the temporal states:

Therefore, for the supervised learning approach to adjust the tunable parameters, the model estimates the outer weights (denoted by the matrix ) and the outer bias weights associated with decision concepts (denoted by the matrix ). Equation (26) reveals how both weight matrices are computed using a pseudoinverse learning rule:

where denotes a column vector full of ones, represents the MP inverse, while is a matrix containing the inverse-friendly one-hot encoding of the decision classes. The MP inverse is one of the best strategies to solve the least squares problem when is not invertible.

This approach combines unsupervised and supervised learning to compute the weights of the recurrence-aware neural classifier. Later in [145], the authors proposed a modified backpropagation through time algorithm for models used in multi-output regression settings.

In [146], Long Short-term Cognitive Networks (LSTCNs) are introduced to deal with long univariate and multivariate time series. In this model, the time series is split into chunks or time patches, each consisting of a tuple . Each chunk is processed with a Short-term Cognitive Network (STCN) block [147] described by four matrices and , and . While and are initialized using the knowledge learned by the previous STCN model, and are learned from the data contained in the current time patch. Overall, the forecasting is done as follows:

such that

where and are matrices encoding the input and the predicted values for the current time patch. The ⊕ operator performs a matrix-vector addition between each row of a given matrix and a vector, assuming they have the same number of columns.

Equation (29) displays the deterministic learning rule that computes the learnable matrices,

where such that is a column vector filled with ones, is the diagonal matrix of while is the ridge regularization penalty. The reader can notice that an STCN block trained using the learning rule in Equation (29) can be seen as a fusion between an Extreme Learning Machine (ELM) [148] and an FCM model that performs two iterations.

Morales-Hernández et al. [149] used the LSTCN model to tackle a windmill case study. In their paper, a workflow of the iterative learning process for an LSTCN model is depicted, particularly when an incoming chunk of data triggers a new training process on the last STCN block, utilizing the knowledge the network has learned in previous iterations. After that, the prior knowledge matrices are recomputed using an aggregation operator and stored for use as prior knowledge when performing reasoning. The simulations showed that LSTCNs are significantly faster than other recurrent neural architectures in terms of training and test times, while also achieving greater accuracy when using default parameters. The former feature is especially relevant when designing forecasting models operating in online learning modes.

Also, Liu et al. [150] presented a hybrid non-stationary time-series forecasting method based on Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), Autoencoder Networks (AEs), and FCMs. This hybrid architecture was named GAE-FCM. It consists of a decomposition module and a prediction module. The decomposition module is achieved using a GRU-AE scheme, where the GRU network extracts the potential features and long-term trends of the time series. Meanwhile, the AE is applied to continuously optimize the extracted feature data (hidden state sequence) by minimizing the error between the input and output sequences, thereby avoiding under-fitting of the model. Subsequently, the decomposition time series is applied to construct an FCM-based predictor learned by a regression algorithm. This scheme can depict the potential representations and capture the long-term trend of non-stationary time series. Furthermore, this regression-based module provides an effective optimization algorithm for reconstructing an FCM in time-series forecasting.

In [151], the authors introduced hybrid deep learning structures, interweaving Fuzzy Cognitive Networks with Functional Weights (FCNs-FW) with well-established Deep Neural Networks (DNN). They presented three hybrid models, which combine the FCN-FW with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Echo State Networks (ESNs), and AEs, respectively. The CNN-FCN model exhibited a more compact behavior, with most engine predictions being uniformly close to zero error. Additionally, the AE-FCN model reported good performance in terms of prediction error and was slightly superior to the standard CNN formalism. The ESN-FCN approach performed poorly, with the score being dominated mainly by one heavily late prediction. However, both AE-FCN and ESN-FCN models utilize a dramatically lower number of trainable parameters. Of particular interest would be the evaluation of more complex models of the already established hybrid implementations towards narrowing down late predictions. AE and CNN extensions could be utilized for the first part of AE-FCN and CNN-FCN, respectively. At the same time, for the ESN-FCN model, hierarchically connected reservoirs could be used to discover higher-level features of the under-examination signal.

In [152], the authors proposed a time-series prediction model that combines high-order FCMs (HFCMs) with a redundant wavelet transform to address large-scale nonstationary time series. The redundant Haar wavelet transform decomposes the original nonstationary time series into a multivariate time series. To handle large-scale multivariate time series efficiently, a fast HFCM learning method is introduced, using ridge regression to estimate the learnable parameters and reduce learning time.

In [153], the authors employed the least squares method to learn the weight matrix of an FCM model derived from time series data, where the fuzzy c-means clustering algorithm is used to construct the concepts. The study reports a significant reduction in the learning time compared to traditional methods. In [154], the authors developed a time series prediction method based on Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) and HFCMs, referred to as EMD-HFCM. Their solution utilizes EMD to extract features from the original sequence and obtain multiple sequences that represent the concepts. To learn the HFCM model efficiently and accurately, a robust learning method based on Bayesian ridge regression is employed, which can estimate the regular parameters from data instead of being set manually. Subsequently, predictions can be based on the HFCM model’s iterative characteristics. After extracting the features and obtaining multiple time series, the remaining task is to learn the weight matrix. The authors employed EAs to learn the local connections and finally merged them into an entire weight matrix. More recently, Zhou et al. [155,156] presented a new regression-based learning algorithm for their granular FCMs using an adaptive loss function. This learning algorithm leverages the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers and the Quadratic Programming method for time series prediction tasks.

4.3. Gradient-Based Learning Algorithms

The literature reports several successful gradient-based algorithms devoted to synaptic and nonsynaptic learning of FCM-based models. Next, we will discuss representative algorithms in each family type, with a special emphasis on those published within the last five years.

4.3.1. Nonsynaptic Learning

Nonsynaptic learning refers to alternative learning mechanisms that do not involve adjusting synaptic weights, which is the predominant method in deep learning. Traditional learning algorithms, such as backpropagation, focus on changing the weights of connections between concepts to minimize error and optimize performance. However, nonsynaptic learning mechanisms might involve adjusting other network parameters or employing different strategies altogether. Examples include modifying the parameters that control the behavior/properties of the concept’s activation functions, altering the network topology, or utilizing external memory resources. These approaches can enhance the network’s generalization from limited data, adapt quickly to new information, or provide more interpretable models [157].

In [147], the authors used nonsynaptic learning for training STCN blocks, which are FCM-inspired neural systems. This learning type is suitable for reducing the simulation error without altering the knowledge stored in the synaptic connections. The proposal first transforms the data into a sigmoid space before applying the nonsynaptic learning method, since the model lacks a formal output layer with linear units. This learning method is applied sequentially to each STCN block, using the parameters estimated in the current iteration to compute the subsequent short-term evidence. Each learning process will stop either when a maximum number of epochs is reached or when the variations on the parameters from one iteration to another are small enough. The study showed that if the latter situation arises, the STCN model will enter a stationary state, where the network will continue to produce similar approximation errors.

In [158], a nonsynaptic learning algorithm was designed to support long-term dependencies, relying on the error backpropagation principle. The recurrent nature of LTCNs allows for the unfolding of their topology into a feed-forward, multilayered neural network, where each layer represents an iteration. This neural cognitive mapping technique preserves the expert knowledge encoded in the weight matrix while optimizing the nonlinear mappings provided by the activation function of each concept. In brief, a nonsynaptic, backpropagation-based learning algorithm, powered by stochastic gradient descent, is proposed to iteratively optimize four parameters of the generalized sigmoid activation function associated with each concept. The model also allows for the injection of expert knowledge in the form of constraints placed on the activation values of each concept, ensuring that the learning method preserves the meaning of these activation values as defined by the expert.

More recently, Nápoles et al. [159] introduced a learning algorithm designed to address the inverse simulation problems in FCMs using the quasi-nonlinear reasoning rule. The algorithm determines the initial conditions of the model that produce the desired outputs specified by the modeler. The contribution is based on three main components that aim to generate feasible and accurate solutions. They used numerical optimizers that approximate the gradient information (i.e., the Jacobian and Hessian matrices).

4.3.2. Synaptic Learning

Synaptic learning is a learning paradigm primarily based on the adjustment of synaptic weights, which are the parameters that determine the strength of connections between neural units. This concept is inspired by biological neural networks, where learning and memory are believed to be encoded through changes in the strength of synapses. In synaptic learning, one approach is implemented through algorithms like backpropagation, where the network learns to perform a specific task by minimizing the error between its output and the ground truth. The adjusted weights encode the learned information, allowing the network to make accurate predictions or classifications based on input data. Synaptic learning has driven the success of deep learning paradigms, enabling ANN-based models to achieve remarkable performance across a wide array of applications [160].

For example, in [161], the authors proposed an approach based on applying the delta rule initially designed for ANN models. While in [162], the weights are updated by gradient descent on a squared Bellman residual. More recently, in [163], the authors transform the weight learning problem of FCM into a constrained convex optimization problem, which can be solved by applying gradient methods. In [164], a multi-start gradient-based approach and two evolutionary-based algorithms were hybridized with a gradient-based local search procedure to build FCM models.

In [165], the author proposed a classification method based on FCMs by employing a fully connected map structure, which allows connections between all types of concepts. They also applied a gradient-based algorithm for model learning, realized through symbolic differentiation. The performance of this FCM-based classifier proved to be competitive with state-of-the-art approaches. The hypothesis that the FCM classifier can transform the feature space, making observations belonging to a given class more condensed and easier to separate, was confirmed through two tests. These tests involved calculating internal clustering scores and constructing pipelines consisting of an FCM transformer and a classification algorithm.

In [166], the authors presented an iterative smoothing learning method for large-scale FCM models. In terms of sparse signal reconstruction, the method’s objective function is formulated using regularization and total variation penalties. These penalties are beneficial for capturing the sparse structural information of FCM and enhancing the robustness of network reconstruction. To address the non-smooth nature of the penalty, Nesterov’s smoothing technique is employed to transform the problem into a convex optimization problem. Subsequently, the algorithm, based on proximal gradient descent, is applied to solve the convex optimization efficiently.

The study detailed in [167] introduced a Deep Neural network-based FCM model (DFCM) to achieve interpretable multivariate prediction. The DFCM model incorporated deep neural network models into the FCM’s knowledge representation framework. The study validated the performance of DFCM in terms of both interpretability and predictive capability across two real-world open systems. In the study reported in [167], the authors highlighted how DFCM provided relevant insights when constructing interpretable predictors in real-life applications. Special attention was given to time-related factors, and an LSTM-based u-function was introduced to capture exogenous factors with time dependence. In the DFCM model, the neural network components facilitated the modeling of nonlinear relationships, the u-function employed an LSTM network to capture long-term dependencies, and the model could also exploit dependencies among different series.

Following a different direction, the authors in [168] illustrated the benefits of using numerical optimizers over backpropagation-like variants for learning small and mid-sized FCM models. Other approaches that utilize numerically approximated gradients include the learning-based aggregation of FCMs [169] and the supervised learning method for FCMs employed in control problems [89], which do not require any training data.

4.4. Privacy-Preserving Learning

As FCMs increasingly model sensitive domains such as healthcare diagnostics, financial risk assessment, and critical infrastructure management, privacy preservation emerges as a fundamental concern. The learning process for FCMs often requires access to sensitive data from individuals or organizations, yet regulatory frameworks (e.g., the General Data Protection Regulation and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) and ethical considerations demand that such data remain protected. Privacy-preserving FCM learning addresses this tension by enabling model construction from distributed or sensitive data sources while providing formal guarantees against information leakage. This challenge is particularly acute in participatory modeling scenarios in which domain experts contribute proprietary knowledge, or in multi-institutional collaborations, where data sharing faces legal and competitive barriers [51].