Abstract

This study focuses on the aeroacoustic aspects of ducted rotors that could possibly be used in future electrically driven helicopter tail rotor systems. It provides a comprehensive understanding of the tip flow evolution, and of the interaction with the stator stage. High-fidelity compressible numerical simulations are performed and compared with experimental results. A periodic variation is seen in the aerodynamic performance of the rotor blades, which is associated to a potential-interaction phenomenon. Additionally, the convection of the tip vortices and further impingement in the stator vanes generate torque fluctuations on these elements. Dilatation fields and contours confirm a noise source generated by the tip-vortex–stator interaction. Finally, excellent far-field noise comparisons between the numerical and experimental results are obtained for both tonal and broadband noise.

1. Introduction

Urban Air Mobility (UAM) is currently undergoing incredible growth. However, social acceptance and recent regulations require these aircraft to minimize their noise levels. To do so, new designs rely on replacing combustion engines by fully electric or hybrid-electric propulsion systems. This change releases some design constraints inherent to conventional systems. One consequence is that it enables the use of multiple rotors in the tail that operate at different speeds, and can significantly enhance maneuverability. Therefore, the conventional open-tail rotor could be replaced by a shrouded-tail rotor configuration in a multirotor architecture. These systems offer several advantages in terms of safety and aerodynamic and acoustic performance [1]. The presence of a duct fairing surrounding the rotor blades avoids hazardous collisions and in-ground accidents. Additionally, the rotors can be embedded in a vertical fin with an airfoil-like cross section, which produces most of the needed anti-torque, especially during forward flight conditions. As a consequence, the rotor loading is reduced together with the power requirements, reducing the operational cost. The decrease in loading also leads to a reduction in noise due to the lower aerodynamic loads. Furthermore, the presence of the duct also contributes to the reduction in noise by providing shielding and modifying the noise directivity of the tail rotor system [2].

Such a configuration also helps guide the flow, control the tip gap, and mitigate side wind effects. Nevertheless, the acoustic emission may be influenced by the presence of the stator, which induces potential effects on the rotor. This mechanism, known as potential-interaction noise (PIN), becomes particularly significant when the axial rotor–stator spacing is short, typically less than a quarter of the chord length [3], a configuration commonly found in drone systems. PIN has been studied experimentally [4,5], numerically [6,7,8], and analytically [9,10] using simplified rotor–beam configurations. However, due to the larger dimensions of the present setup, PIN is not dominant and is instead masked by rotor–stator interaction (RSI) noise. RSI noise is generated by the stator vanes through the periodic impingement of flow structures and radiates at harmonics of the blade-passing frequency (BPF) in homogeneous rotor–stator stages. Two principal flow structures drive RSI noise. The first is the wake, producing the well-known wake-interaction noise (WIN). Leaned and swept stator vanes induce non-simultaneous impingement along the span, promoting phase cancellation and reducing WIN [3]. In addition, as shown by Glegg [11], RSI is intrinsically linked to blade–vortex interaction (BVI), a phenomenon governed by the dynamics of the blade tip vortex.

Although these findings initially emerged from helicopter rotor research, recent works have demonstrated similar behaviors in low-speed ducted rotors, where tip vortices (TVs) may interact either with subsequent blades [12] or with downstream stator vanes [13,14]. The former generates sub-harmonic humps at frequencies below the BPF and its harmonics [15], while the latter increases tonal noise at the BPF and harmonic frequencies. Several parameters, including blade loading [16], blade pitch [17], and tip-gap size [18], have been shown to determine which interaction dominates. Comparable mechanisms have also been identified in contra-rotating open rotors (CRORs), where the periodic impingement of coherent tip vortices contributes to tonal interaction noise [19]. This phenomenon has been confirmed experimentally [20], numerically [21,22], and analytically [23,24,25]. We therefore seek to confirm the BVI mechanism active in the present configuration by analyzing the time evolution of the loading on the stator and relating it to noise generation.

To understand the effects of the tip-vortex–stator interaction in the present electrical tail rotor, a combination of experimental and numerical simulations is used. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the duct fan system and its experimental setup. Section 3 describes the numerical method and parameters used to later validate the simulation and show the results obtained in Section 4 and Section 5, respectively. Finally, some conclusions are drawn.

2. Rotor Geometry and Reference Experimental Setup

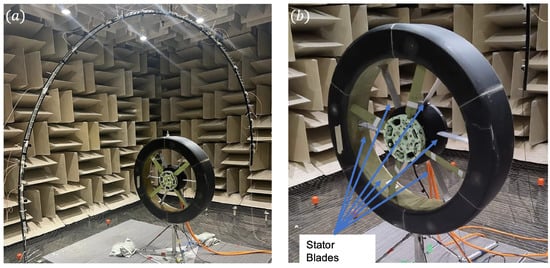

The ducted rotor used in this study is a possible design for future electrically driven helicopter tail rotor systems. The system consists of a four-blade rotor () and a duct held by six stator vanes (). Due to confidentiality, all the following measurements are given based on the diameter of the casing (D). The system has a hub with a diameter of and a tip gap of approximately . The casing extends up to downstream of the center of rotation. The experiment was carried out inside the open-jet anechoic wind tunnel at the Université de Sherbrooke (UdS), which has a cut-off frequency below 100 Hz and wedge-tip to wedge-tip dimensions of 7 m long, 5.5 m wide, and 4 m tall. The ducted rotor is tested in hover in the middle of the anechoic chamber, as shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes the main physical and geometrical parameters.

Figure 1.

UdS experimental set-up: (a) overview with microphone array; (b) zoom on the ducted fan system.

Table 1.

Main geometrical and flow parameters of the ducted fan system (tip Mach and chord-based Reynolds numbers).

Acoustic directivity measurements are performed using an arc of 2.3 D radius with its center aligned with the center of the rotor. The directivity antenna is instrumented with a total of 12 evenly distributed B&K 1/4” microphones type 4957 from 0° to 180°, with 90° corresponding to the rotor disk plane. Windscreens are used in the microphones to reduce flow noise. The arc is rotated clockwise to different positions to account for the noise directivity. The acoustic signals are acquired at a sampling frequency of 65.5 kHz for 30 s. Acoustic narrow band spectra are computed from the time signals using Welch’s periodogram method with a Hanning window, a number of segments defined on the length of the signal, and a 50 % overlap. An accelerometer was placed on top of the casing to minimize the vibrations of the system that contaminated the far-field acoustic measurements. This was done by systematically evaluating the frequency spectra given by the accelerometer to check for any undesired frequency contribution with large amplitudes.

Additional tests are performed on an outdoor stand on which a load cell measures aerodynamic loads, mainly thrust (T) and torque (Q). The following sections will define the time-averaged thrust and torque under their dimensionless form as and , respectively. is the fluid density, f is the rotational frequency of the rotor, D is the diameter of the rotor, and are the time-averaged signals after the transient has decayed. The experimental mass-flow rate is also estimated from the inviscid conservation of mass-momentum. Even though load and acoustic measurements were not performed simultaneously, synchronous analysis is achieved in the simulations, the setup of which is described in the next section.

3. Numerical Method and Setup

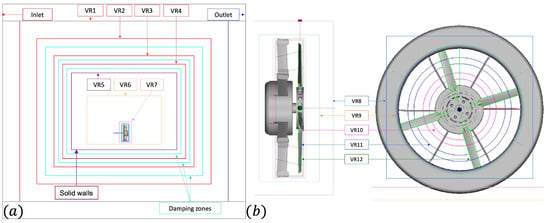

The complete experimental setup, including the anechoic environment, is reproduced in the simulation implemented using the Lattice–Boltzmann method (LBM) solver, PowerFLOW 6-2024-R1. The computational fluid domain, illustrated in Figure 2, is a cubic volume of with all outer boundaries having free-flow conditions and therefore mimicking the hover state used in the experimental campaign. High artificial viscosity values are also imposed on the outer layers of the domain to prevent the reflection of acoustic waves. Subsequently, these boundary conditions were validated by checking the absence of any reflected noise coming from the outer layers of the domain in several instantaneous dilatation fields in the meridional plane of the rotor. Solid walls are used in the inner layer just after the last damping zone to delimit the anechoic environment. The ducted rotor presented in Figure 1 is then used without any simplification and is placed at the same location as in the experimental campaign, using the solid walls mentioned before as a reference.

Figure 2.

Computational domain and voxel refinement regions: (a) full domain; (b) zoom on the fan.

A total of 13 Variable Resolution (VR) regions are used to discretize the fluid domain with an octree mesh, where the grid is composed of cubic elements called voxels, with the finest VR placed around the rotor blade. A methodology similar to that implemented by [14] is used for the present work with an additional mesh refinement region placed in the interstage between the rotor and the stator, as shown in Figure 2b, to capture the correct tip flow and wake contraction. The smallest voxel size is , resulting in an average and for the blade and casing surfaces, respectively. The intermediate VR zones have a voxel size based on the grid sizes reported by [15,26] for automotive ring fans with similar tip Reynolds numbers. The resulting number of fine equivalent voxels for the current setup is about 275 million.

Surface probes are created on the casing and stator vanes. For the former, they are located in the azimuthal and axial directions with a 5∘ and 5% spacing, respectively. For the latter, the probes are located in both the spanwise and chordwise directions, both with a 5% spacing. Velocity and pressure are saved at each point to further evaluate the tip vortex trajectory and its interaction with the stator vanes. Probes mimicking the microphones used in the experimental campaign are also created with an averaging volume of characteristic size corresponding to the diameter of the B&K 1/4” microphones. Acoustic waves propagate directly towards these probes to evaluate the correlation with the data obtained from the casing and stator, as well as to assess the convergence of the simulation. Surface pressure, velocity, and forces are recorded on the different components of the system to evaluate , wall pressure fluctuations, torque, and thrust. The first is also used to perform a hybrid approach by applying the solid formulation of the Ffowcs Williams and Hawkings (FW-H) acoustic analogy. This is done to assess the contribution of each component to the far-field noise and to compare these results with those obtained using the direct approach. Finally, two virtual half-spheres at the inlet and outlet of the module are used to determine the mass flow rate through the ducted tail rotor system.

An initialization run, with a simulated time of 3 s, is performed using a coarser mesh to establish the flow in the anechoic environment. The instantaneous flow field is then used to seed the fine mesh simulation, which, so far, has a simulation time of 0.26 s corresponding to 15 rotor rotations. After 8 transient rotations, results are obtained for the subsequent rotations, using a sampling frequency consistent with the experimental campaign.

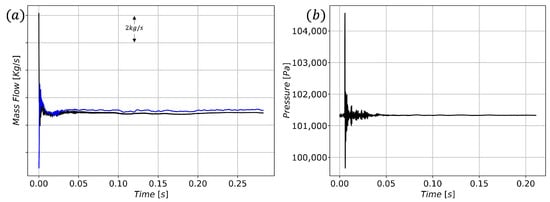

4. Simulation Verification and Validation Process

The convergence of the aero-acoustic simulation is monitored by the stabilization of the mass flow rate in the two mentioned surfaces and the pressure signal on the far-field probes mimicking the experimental microphones. Figure 3 shows that convergence is achieved for both variables after 0.05 s, corresponding to three rotations. This value is lower than the number of revolutions at which data storage begins, indicating that the transient behavior of the system has been properly removed. Furthermore, the difference between the mass flow rates recorded at the inlet and outlet surfaces, black and blue lines in Figure 3a respectively, is less than 2%, suggesting consistency in the simulation.

Figure 3.

Convergence of (a) the mass-flow rate and (b) far-field acoustic pressure.

The aerodynamic performance and mass flow rate obtained from the LBM simulation are validated with respect to the experimental data acquired using the methodology described above and the results obtained previously by Jaiswal et al. [27]. Wall-resolved RANS and LES simulations using the Lax–Wendroff numerical scheme were conducted for the purpose of comparison together with two previous LBM simulations, i.e., LBM Coarse and LBM Fine [13]. The latter has the same finest voxel size as the current simulation, and they only differ on the refinement of the interstage region. Table 2 summarizes the results, where the mass flow rates are normalized by the experimental value obtained, along with the relative error with respect to the experimental values.

Table 2.

Comparison of the aerodynamic performance of the calculated cases with experiments.

Although the discrepancies are up to 20%, all simulated performances lie within the same range, which stresses that the current experimental mock-up is realistic. The estimated experimental mass flow rate is systematically underpredicted by all methods, except for the LES, where this variable is imposed as a boundary condition of the simulation. Moreover, for this method, the thrust coefficient () is underestimated due to the lack of data in the stator region. A similar situation occurs for the LBM Fine and Coarse configurations, preventing a direct conclusion about the trend of the data as a function of grid size. Between all the methods, the results obtained with RANS present the major discrepancies for all variables compared to the experimental results. These differences, as stated by Santamaria et al. [28], are attributed to the grid and the fully turbulent flow assumption, and to the lack of resolution in the wake region, which prevents calculating the correct trajectory and dissipation of the tip vortices under hover conditions. Therefore, for the present simulation, as stated in the numerical setup, an additional refinement region is added in the inter-stage between the rotor and the stator. This increases the resolution in the wake, which allows capturing the proper wake contraction and tip vortex trajectory, thereby improving the prediction of the aerodynamic performance and mass flow rate of the system compared to previous LBM simulations.

5. Performance and Flow Field Analysis

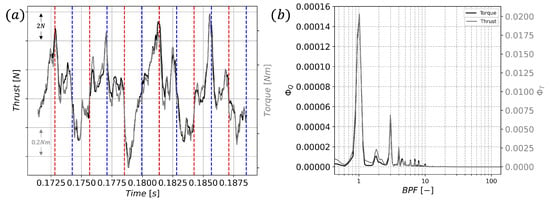

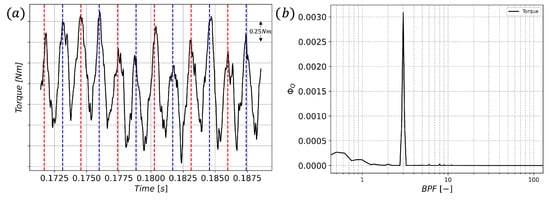

Figure 4 shows the integrated torque and thrust on the rotor blades over one complete revolution and its associated FFT. A total of 12 peaks are visible in the time trace. The first of those happens at approximately 0.173 s, corresponding to the moment when a blade passes over a stator vane. This situation is marked in Figure 4a by the first red dotted line. At this instant, the two blades located at and are interacting with a stator vane, while those located at and are not. The latter, therefore, interacts with a stator vane after an angular displacement of , corresponding to the first blue dotted line in Figure 4a. Furthermore, the following vertical lines are separated by the time it takes for each pair of blades to cover the angular displacement between two stator vanes (). A perfect match is observed between the guide lines and the four main peaks, while a shift is seen for the others. This shift is most likely due to the skewed design of the stator vanes, which either advances or delays the interaction with the rotor blades. Therefore, this situation implies that the thrust and torque variations presented in Figure 4a are mainly due to the potential interaction seen by the rotor blades as a consequence of the presence of the stator vanes. Future studies will be conducted to analyze the amplitude variations between the peaks. Figure 4b shows the Welch periodogram method applied to the time signals of the rotor aerodynamic performance. Two main peaks located at the first and third BPF harmonics are depicted. The former is expected because it is located at the blade passing frequency related to the rotational speed and number of blades. The latter is present because of the potential interaction with the stator that causes a total of 12 peaks that provides the aforementioned frequency when divided by the total number of rotor blades.

Figure 4.

Integrated torque and thrust on the rotor blades. (a) Evolution over one rotation; (b) power spectral density.

A similar methodology is applied to the integrated torque on the stator vanes in Figure 5. The same convention for the vertical lines is followed. As with the rotor, the displacement between lines is related to an angular displacement of . Figure 5b shows again the appearance of the 3rd harmonic of the BPF as the main contributor based on the number of peaks and blades in the system. In contrast to the rotor, the first harmonic of the BPF is not present, as the data are now recorded in a stationary frame. Additionally, when Figure 5a is analyzed, a time shift is observed relative to the time trace in Figure 4. This shift corresponds to an angular displacement of 23°, which is less than the distance between the two interactions with the stator vanes (30°). Therefore, the torque fluctuations are not related to the potential interaction phenomena but rather to some fluid–solid interaction. Rendon et al. [14] already showed in a similar configuration that the main interaction is between the plunging tip vortex and the stator vanes.

Figure 5.

Integrated torque on the stator vanes. (a) Evolution over one rotation; (b) power spectral density.

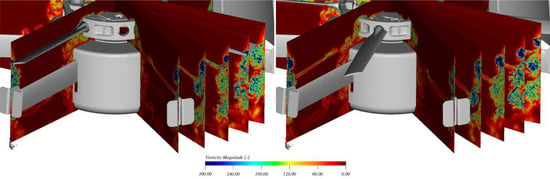

Figure 6 shows the instantaneous vorticity magnitude projected onto several radial cuts at two different time frames. Figure 6a corresponds to the first red dotted line in Figure 4a, where one of the blades passes through the stator vane. On the other hand, Figure 6b is associated with the previously mentioned angular shift of . As shown in Figure 6a, a high-vorticity region, caused by the emission of the tip vortex, is present at the tip of the two blades. Additionally, a broader high-vorticity region lies downstream of this structure, which is associated with the tip vortex produced by the preceding blade. Moreover, Figure 6b shows this structure being convected downstream and interacting with the stator vane, generating a high-vorticity region. Thus, the fluid–solid interaction is linked to the interaction between the tip flow and the stator. Furthermore, in both figures, a high radial vorticity line related to the vortex sheet shed from the blade trailing edge is seen. These two main features, the tip vortex and vortex sheet, therefore interact and generate a vortex–vortex interaction that may radiate to the far-field as an additional noise source.

Figure 6.

Iso-contours of instantaneous vorticity magnitude at two different instants in several meridional planes.

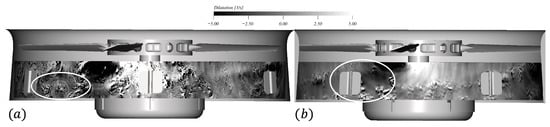

In Figure 7, the instantaneous dilatation field computed as at 95% and 90% span provides a qualitative insight on the acoustic sources involved in the system. The focus is put in the stator region to obtain a better view of the vortex–vortex and fluid–solid interaction. Two different time frames and views are used to show the phenomena of interest. Figure 7a shows the merging point of the tip vortex and vortex sheet surrounded by the white circle. In addition to the hydrodynamic structures, acoustic waves are produced as a consequence of this interaction. Therefore, quadrupolar noise can be present in the far-field noise signature of the present ducted rotor. On the other hand, surrounded by the white circle in Figure 7b, the interaction of the convected tip vortex with one of the stator vanes is seen. Due to this impingement, acoustic waves are emitted from the stator vane. The wave fronts are mostly masked by the presence of the trailing-edge noise source. However, there is a clear difference in the frequency of emission, with the stator source radiating at a lower value. Now that the tip-vortex–stator interaction is confirmed with a possible noise source related to it, the pressure fluctuations on the surface are analyzed.

Figure 7.

Iso-contours of instantaneous dilatation fields at two different instants at (a) 95% and (b) 90% span.

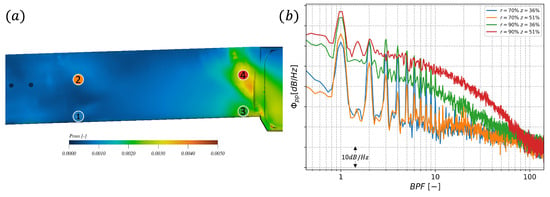

Figure 8 shows the on the surface of one stator vane along with the wall-pressure fluctuations (WPF) at the points depicted on the vane. A low homogeneous value of is seen along most of the radial extent of the vane (probe (1)), stressing a weak rotor–wake interaction. However, a high value, related to higher pressure fluctuations is visible in the tip region at 90 % span (probes (3) and (4)), which is related to the impingement of the tip vortex. This is confirmed by the high zone in the tip region that follows a diagonal path similar to the slope of the convected tip vortices. As mentioned, the WPF are calculated at four locations including the zones with minimum and maximum variations. The spectra present a dominant tonal component aligned with the blade passing frequency of the rotor. For the probes located before mid-chord, the tones dominate up to the 10th BPF harmonic. Contrarily, for the probes located near the tip region, even if the amplitude of the tones is higher by about 5 dB, they tend to disappear after the 5th harmonic. For this region, the broadband component also increases, suggesting the presence of more turbulent structures over a wide range of length scales. Overall, the impingement point appears to be associated with the highest levels for both the first BPF and the broadband component.

Figure 8.

on a stator vane: (a) iso-contours with probe locations; (b) PSD of wall pressure at Probes (1) to (4).

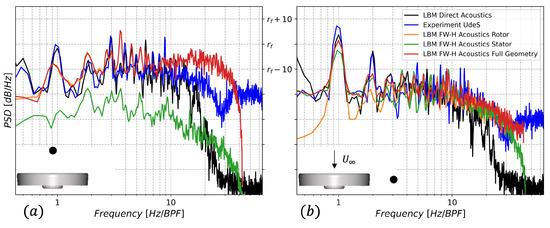

The pressure signals recorded at the far-field probes are used to provide direct noise acoustic levels, which are compared with the experimental and FW-H results. The experimental signal is resampled to achieve the same time length and sampling frequency to have the same parameters when performing Welch’s periodogram. Comparisons are made for the microphone located upstream of the system (Figure 9a) and above the casing (Figure 9b). The spectra present a roll-off after the 20th BPF harmonic which is related to the cut-off frequency associated with the specific voxel size where the probes used for direct propagation are located. The spectra have strong tonal (BPF and harmonics) and broadband noise. The numerical results obtained from the direct propagation and the FW-H analogy show good agreement with experiments for the levels of the BPF and first harmonics at the evaluated locations. The discrepancies coming from the FW-H approach at low-frequencies are related to the shorter time signal acquired for this approach. However, there is an improved prediction of the tonal and broadband noise when comparing with the results obtained by Rendon et al. [14]. The former is attributed to the better resolution of the periodic unsteady interstage flow and improved aerodynamic performance of the rotor system. The latter, on the other hand, is related to a better resolution of the turbulent interaction noise sources, such as the tip vortex, which are known to radiate in the upstream direction (Figure 9a). The acoustic analogy is then used to evaluate the contribution of both the rotor and the stator separately. Figure 9a shows a spectra dominated by rotor noise with a low level coming from the stator. This low level is related to a minimum noise radiation that occurs aligned with the stator vanes as shown by Vella et al. [9] and Rendon et al. [6] for the noise emitted by a beam in a rotor-strut configuration. The increase in the broadband component for the high-frequency region for this approach arrives from the assumption of the free-field radiation. This assumption affects the noise directivity at these frequencies as the wavelength is comparable with the duct, and diffraction starts to play an important role. Similarly, Figure 9b shows a reduction in the tonal component after the third BPF harmonic. This reduction is associated with the masking effect generated by the presence of the casing, as the length of the duct begins to be comparable with the wavelength associated to the frequency of emission. There is an increase in the stator noise level, with a dominant contribution especially at the second harmonic of the BPF. This frequency is related to the major tonal contribution regardless of the location, as seen in Figure 8.

Figure 9.

Far-field noise comparison between experiments and simulations for microphones located (a) upstream and (b) above the casing.

6. Conclusions

High-fidelity compressible simulations have been performed for a ducted rotor used as a concept design for future electrically driven tail rotor systems. The complete experimental setup, including the anechoic chamber, has been simulated with the LBM solver PowerFLOW 6-2024-R1. Special attention has been paid to the meshing in the rotor–stator interstage to properly resolve the wake contraction and tip vortex trajectories and improve previous aerodynamic predictions of mean thrust and torque.

The time trace of the unsteady torque and thrust integrated over the rotor blades shows 12 main peaks during a rotational period, which can be traced to the potential interaction with the stator vanes. Similar 12 peaks are seen in the unsteady torque integrated over the stator vanes, but shifted by a time delay corresponding to an angular displacement of 23∘. By using instantaneous vorticity magnitude fields, this time shift is related to the interaction of a blade tip vortex with a stator vane, and corresponds to its trajectory from its point of generation to its impact on the stator vane. This strong fluid–solid interaction between the blade tip vortices and the stator vanes also yields a main source of noise evidenced by the dilatation field at different blade-to-blade cuts. This interaction is also seen to occur near the tip region of the stator vane between 80% and 90% of the span, as shown by the local high-pressure fluctuations together with an increase in the spectra levels for both tonal and broadband components. Moreover, a vortex–vortex interaction is evidenced in the tip region, yielding an additional quadrupolar source.

Noise spectra obtained from a direct and hybrid approach are compared with those obtained from the experiments for the upstream and rotor plane locations. A good match between the experimental and numerical results is observed until the cut-off frequency of the direct approach at the 20th BPF harmonic. An improvement in the tonal and broadband levels is accomplished when compared to previous simulations. The first is related to the better prediction of the periodic unsteady loading, which also yields an improved aerodynamic performance, while the latter is associated with the better resolution of the random turbulence interaction noise sources. Finally, the use of the FW-H acoustic analogy allows separating the noise from each element of the system. The rotor is shown to be the major noise contributor except for the second harmonic of the BPF where the stator dominates. This dominance is then related to the wall pressure fluctuations seen in the vanes as a result of the tip-vortex–stator interaction.

Future studies will more deeply analyze the evolution of the tip flow and its contribution to the far-field noise. Filtered dilatation fields will be used to have a qualitative insight in the presence of the new found noise sources in the microphone regions. Finally, analytical models and the feasibility to create simple rules to detect if the rotor stator noise is dominated by either wake or tip vortex interaction will be evaluated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.-A. and S.M.; methodology, J.R.-A. and S.M.; software, J.R.-A.; validation, J.R.-A.; formal analysis, J.R.-A. and S.M.; investigation, J.R.-A. and S.M.; resources, S.M.; data curation, J.R.-A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.-A.; writing—review and editing, J.R.-A. and S.M.; visualization, J.R.-A.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded with the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through the Mitacs-Alliance Grant #ALLRP 570863-21 with Bell Textron Canada Ltd. and Optis Engineering as industrial partners.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request due to confidentiality reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Calcul Quebec and Digital Research Alliance of Canada for providing the necessary computational resources for this research, and Dassault Systems for providing the PowerFLOW licenses and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAM | Urban Air Mobility |

| BPF | Blade Passing Frequency |

| LBM | Lattice–Boltzmann Method |

| VR | Variable Resolution |

| FW-H | Ffowcs Williams and Hawkings |

| LES | Large Eddy Simulation |

| RANS | Reynolds Average Navier–Stokes |

| FFT | Fast Fourier Transform |

| WPF | Wall-Pressure Fluctuations |

References

- Vuillet, A. New aerodynamic design of the Fenestron for improved performance. In Proceedings of the 12th European Rotorcraft Forum, Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, 22–25 September 1986. [Google Scholar]

- You, J.H.; Breitsamter, C.; Heger, R. Numerical investigations of Fenestron™ noise characteristics using a hybrid method. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2016, 7, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Kucukcoskun, K. Near-and-far field modeling of advanced tail-rotor noise using source-mode expansions. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 453, 328–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawodny, N.S.; Boyd, D.D., Jr. Investigation of rotor-airframe interaction noise associated with small-scale rotary-wing unmanned aircraft systems. In Proceedings of the AHS Annual Forum and Technology Display, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 9–11 May 2017. number NF1676L-25342. [Google Scholar]

- Gojon, R.; Parisot-Dupuis, H.; Mellot, B.; Jardin, T. Aeroacoustic radiation of low Reynolds number rotors in interaction with beams. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendón-Arredondo, J.; Vella, E.; Ramo, A.A.; Roger, M.; Gojon, R.; Jardin, T.; Moreau, S. Aeroacoustic investigations of a rotor-beam configuration in small-size drones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 158, 1091–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendon, J.; Arroyo Ramo, A.; Moreau, S.; Roger, M. A Numerical and Analytical Approach of the Sound-Scattering Effects in Rotor-Strut Interaction Noise of Small-Size Drones. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (2024), Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doué, N.; Gojon, R.; Jardin, T. Numerical Investigation of the Acoustics Radiation of a Two-Bladed Rotor in Interaction with a Beam. In Proceedings of the Fluid-Structure-Sound Interactions and Control; Kim, D., Kim, K.C., Zhou, Y., Huang, L., Eds.; Singapore, 18 September 2024; pp. 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, E.; Gojon, R.; Parisot-Dupuis, H.; Doué, N.; Jardin, T.; Roger, M. Mutual Interaction Noise in Rotor-Beam Configuration. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (2024), Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Vella, E.; Rendon, J.; Moreau, S. Aerodynamic and Sound-Scattering Effects in Rotor-Strut Interaction Noise of Small-Size Drones. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glegg, S.A.L. Prediction of blade wake interaction noise based on a turbulent vortex model. AIAA J. 1991, 29, 1545–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Pasco, Y.; Yakhina, G. Aeroacoustic investigation of an Urban-Air-Mobility ducted fan. In Proceedings of the 28th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics 2022 Conference, Southampton, UK, 14–17 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Rendon, J.; Pasco, Y.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S. Aeroacoustic investigation of a ducted tail rotor. In Proceedings of the AIAA AVIATION 2023 Forum, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–16 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendon, J.; Moreau, S.; Sanjosé, M. Influence of the Rotor Blade Pitch Angle on the Far-Field Noise Emissions of a Ducted Tail Rotor. In Proceedings of the 30th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference (2024), Rome, Italy, 4–7 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, S.; Sanjose, M. Sub-harmonic broadband humps and tip noise in low-speed ring fans. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preisser, J.; Brooks, T.; Martin, R. Recent studies of rotorcraft blade-vortex interaction noise. J. Aircr. 1994, 31, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komerath, N.; Ganesh, B.; Wong, O. On the formation and decay of rotor blade tip vortices. In Proceedings of the 34th AIAA Fluid Dynamics Conference and Exhibit, Portland, OR, USA, 28 June 2004–1 July 2004; p. 2431. [Google Scholar]

- Goudswaard, R.J.; Ragni, D.; Baars, W.J. Effects of the rotor tip gap on the aerodynamic and aeroacoustic performance of a ducted rotor in hover. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2024, 155, 109734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, R.S.; Kingan, M.J.; Go, S.T.; Jung, R. Experimental and analytical investigation of contra-rotating multi-rotor UAV propeller noise. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 177, 107850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.; Komerath, N. Drone scale coaxial rotor aerodynamic interactions investigation. J. Fluids Eng. 2019, 141, 071106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakshminarayan, V.K.; Baeder, J.D. Computational investigation of microscale coaxial-rotor aerodynamics in hover. J. Aircr. 2010, 47, 940–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Chen, H. Prediction of aerodynamic tonal noise from open rotors. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 3832–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roger, M.; Schram, C.; Moreau, S. On vortex–airfoil interaction noise including span-end effects, with application to open-rotor aeroacoustics. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, D.B. Noise of counter-rotation propellers. J. Aircr. 1985, 22, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaglia, M.E.; Léonard, T.; Moreau, S.; Roger, M. A 3D analytical model for orthogonal blade-vortex interaction noise. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 399, 104–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piellard, M.; Coutty, B.B.; Goff, V.L.; Vidal, V.; Perot, F. Direct aeroacoustics simulation of automotive engine cooling fan system: Effect of upstream geometry on broadband noise. In Proceedings of the 20th AIAA/CEAS Aeroacoustics Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–20 June 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, P.; Moreau, S.; Sanjose, M. Aeroacoustic investigation of a helicopter tail rotor. In Proceedings of the 75th Annual Meeting of the American Physical Society Division of Fluid Dynamics, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 20–22 November 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaria, J.; Bierrenbach-Lima, A.; Sanjosé, M.; Moreau, S. Shape considerations for the design of propellers with trailing edge serrations. J. Sound Vib. 2025, 595, 118771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the EUROTURBO. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND) license.